Shared posts

LIGO to publish new paper in wake of New Scientist investigation

Scientists Unveil a New Inventory of the Universe’s Dark Contents

In a much-anticipated analysis of its first year of data, the Dark Energy Survey (DES) telescope experiment has gauged the amount of dark energy and dark matter in the universe by measuring the clumpiness of galaxies — a rich and, so far, barely tapped source of information that many see as the future of cosmology.

The analysis, posted on DES’s website today and based on observations of 26 million galaxies in a large swath of the southern sky, tweaks estimates only a little. It draws the pie chart of the universe as 74 percent dark energy and 21 percent dark matter, with galaxies and all other visible matter — everything currently known to physicists — filling the remaining 5 percent sliver.

The results are based on data from the telescope’s first observing season, which began in August 2013 and lasted six months. Since then, three more rounds of data collection have passed; the experiment begins its fifth and final planned observing season this month. As the 400-person team analyzes more of this data in the coming years, they’ll begin to test theories about the nature of the two invisible substances that dominate the cosmos — particularly dark energy, “which is what we’re ultimately going after,” said Joshua Frieman, co-founder and director of DES and an astrophysicist at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) and the University of Chicago. Already, with their first-year data, the experimenters have incrementally improved the measurement of a key quantity that will reveal what dark energy is.

Both terms — dark energy and dark matter — are mental place holders for unknown physics. “Dark energy” refers to whatever is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate, as astronomers first discovered it to be doing in 1998. And great clouds of missing “dark matter” have been inferred from 80 years of observations of their apparent gravitational effect on visible matter (though whether dark matter consists of actual particles or something else, nobody knows).

The balance of the two unknown substances sculpts the distribution of galaxies. “As the universe evolves, the gravity of dark matter is making it more clumpy, but dark energy makes it less clumpy because it’s pushing galaxies away from each other,” Frieman said. “So the present clumpiness of the universe is telling us about that cosmic tug-of-war between dark matter and dark energy.”

A Dark Map

Until now, the best way to inventory the cosmos has been to look at the “cosmic microwave background”: pristine light from the infant universe that has long served as a wellspring of information for cosmologists, but which — after the Planck space telescope mapped it in breathtakingly high resolution in 2013 — has less and less to offer.

Cosmic microwaves come from the farthest point that can be seen in every direction, providing a 2-D snapshot of the universe at a single moment in time, 380,000 years after the Big Bang (the cosmos was dark before that). Planck’s map of this light shows an extremely homogeneous young universe, with subtle density variations that grew into the galaxies and voids that fill the universe today.

Galaxies, after undergoing billions of years of evolution, are more complex and harder to glean information from than the cosmic microwave background, but according to experts, they will ultimately offer a richer picture of the universe’s governing laws since they span the full three-dimensional volume of space. “There’s just a lot more information in a 3-D volume than on a 2-D surface,” said Scott Dodelson, co-chair of the DES science committee and an astrophysicist at Fermilab and the University of Chicago.

To obtain that information, the DES team scrutinized a section of the universe spanning an area 1,300 square degrees wide in the sky — the total area of 6,500 full moons — and stretching back 8 billion years (the data were collected by the half-billion-pixel Dark Energy Camera mounted on the Victor M. Blanco Telescope in Chile). They statistically analyzed the separations between galaxies in this cosmic volume. They also examined the distortion in the galaxies’ apparent shapes — an effect known as “weak gravitational lensing” that indicates how much space-warping dark matter lies between the galaxies and Earth. These two probes — galaxy clustering and weak lensing — are two of the four approaches that DES will eventually use to inventory the cosmos. Already, the survey’s measurements are more precise than those of any previous galaxy survey, and for the first time, they rival Planck’s.

“This is entering a new era of cosmology from galaxy surveys,” Frieman said. With DES’s first-year data, “galaxy surveys have now caught up to the cosmic microwave background in terms of probing cosmology. That’s really exciting because we’ve got four more years where we’re going to go deeper and cover a larger area of the sky, so we know our error bars are going to shrink.”

For cosmologists, the key question was whether DES’s new cosmic pie chart based on galaxy surveys would differ from estimates of dark energy and dark matter inferred from Planck’s map of the cosmic microwave background. Comparing the two would reveal whether cosmologists correctly understand how the universe evolved from its early state to its present one. “Planck measures how much dark energy there should be” at present by extrapolating from its state at 380,000 years old, Dodelson said. “We measure how much there is.”

The DES scientists spent six months processing their data without looking at the results along the way — a safeguard against bias — then “unblinded” the results during a July 7 video conference. After team leaders went through a final checklist, a member of the team ran a computer script to generate the long-awaited plot: DES’s measurement of the fraction of the universe that’s matter (dark and visible combined), displayed together with the older estimate from Planck. “We were all watching his computer screen at the same time; we all saw the answer at the same time. That’s about as dramatic as it gets,” said Gary Bernstein, an astrophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania and co-chair of the DES science committee.

Planck pegged matter at 33 percent of the cosmos today, plus or minus two or three percentage points. When DES’s plots appeared, applause broke out as the bull’s-eye of the new matter measurement centered on 26 percent, with error bars that were similar to, but barely overlapped with, Planck’s range.

“We saw they didn’t quite overlap,” Bernstein said. “But everybody was just excited to see that we got an answer, first, that wasn’t insane, and which was an accurate answer compared to before.”

Statistically speaking, there’s only a slight tension between the two results: Considering their uncertainties, the 26 and 33 percent appraisals are between 1 and 1.5 standard deviations or “sigma” apart, whereas in modern physics you need a five-sigma discrepancy to claim a discovery. The mismatch stands out to the eye, but for now, Frieman and his team consider their galaxy results to be consistent with expectations based on the cosmic microwave background. Whether the hint of a discrepancy strengthens or vanishes as more data accumulate will be worth watching as the DES team embarks on its next analysis, expected to cover its first three years of data.

If the possible discrepancy between the cosmic-microwave and galaxy measurements turns out to be real, it could create enough of a tension to lead to the downfall of the “Lambda-CDM model” of cosmology, the standard theory of the universe’s evolution. Lambda-CDM is in many ways a simple model that starts with Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, then bolts on dark energy and dark matter. A replacement for Lambda-CDM might help researchers uncover the quantum theory of gravity that presumably underlies everything else.

What Is Dark Energy?

According to Lambda-CDM, dark energy is the “cosmological constant,” represented by the Greek symbol lambda in Einstein’s theory; it’s the energy that infuses space itself, when you get rid of everything else. This energy has negative pressure, which pushes space away and causes it to expand. New dark energy arises in the newly formed spatial fabric, so that the density of dark energy always remains constant, even as the total amount of it relative to dark matter increases over time, causing the expansion of the universe to speed up.

The universe’s expansion is indeed accelerating, as two teams of astronomers discovered in 1998 by observing light from distant supernovas. The discovery, which earned the leaders of the two teams the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics, suggested that the cosmological constant has a positive but “mystifyingly tiny” value, Bernstein said. “There’s no good theory that explains why it would be so tiny.” (This is the “cosmological constant problem” that has inspired anthropic reasoning and the dreaded multiverse hypothesis.)

On the other hand, dark energy could be something else entirely. Frieman, whom colleagues jokingly refer to as a “fallen theorist,” studied alternative models of dark energy before co-founding DES in 2003 in hopes of testing his and other researchers’ ideas. The leading alternative theory envisions dark energy as a field that pervades space, similar to the “inflaton field” that most cosmologists think drove the explosive inflation of the universe during the Big Bang. The slowly diluting energy of the inflaton field would have exerted a negative pressure that expanded space, and Frieman and others have argued that dark energy might be a similar field that is dynamically evolving today.

DES’s new analysis incrementally improves the measurement of a parameter that distinguishes between these two theories — the cosmological constant on the one hand, and a slowly changing energy field on the other. If dark energy is the cosmological constant, then the ratio of its negative pressure and density has to be fixed at −1. Cosmologists call this ratio w. If dark energy is an evolving field, then its density would change over time relative to its pressure, and w would be different from −1.

Remarkably, DES’s first-year data, when combined with previous measurements, pegs w’s value at −1, plus or minus roughly 0.04. However, the present level of accuracy still isn’t enough to tell if we’re dealing with a cosmological constant rather than a dynamic field, which could have w within a hair of −1. “That means we need to keep going,” Frieman said.

The DES scientists will tighten the error bars around w in their next analysis, slated for release next year; they’ll also measure the change in w over time, by probing its value at different cosmic distances. (Light takes time to reach us, so distant galaxies reveal the universe’s past). If dark energy is the cosmological constant, the change in w will be zero. A nonzero measurement would suggest otherwise.

Larger galaxy surveys might be needed to definitively measure w and the other cosmological parameters. In the early 2020s, the ambitious Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) will start collecting light from 20 billion galaxies and other cosmological objects, creating a high-resolution map of the universe’s clumpiness that will yield a big jump in accuracy. The data might confirm that we occupy a Lambda-CDM universe, infused with an inexplicably tiny cosmological constant and full of dark matter whose nature remains elusive. But Frieman doesn’t discount the possibility of discovering that dark energy is an evolving quantum field, which would invite a deeper understanding by going beyond Einstein’s theory and tying cosmology to quantum physics.

“With these surveys — DES and LSST that comes after it — the prospects are quite bright,” Dodelson said. “It is more complicated to analyze these things because the cosmic microwave background is simpler, and that is good for young people in the field because there’s a lot of work to do.”

Why Are There Two Sexes?

Kirill SkorobogatovA few mathematical insights on the nature of sexual reproduction

Sex is one of the greatest mysteries in biology. Why on earth do most large complex animals have two sexes? Asexual reproduction can efficiently produce twice as many offspring as sexual reproduction without the complications of finding and courting a mate. There must be major benefits to having two sexes, but if so, why shouldn’t three sexes be even better? Isaac Asimov explored this complicated scenario in his 1972 Nebula Award-winning novel “The Gods Themselves,” and he wasn’t the only science fiction writer to do so. Is there some reason why three is definitely a crowd?

Many biological hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mystery. In this column, we’ll approach the system from a different point of view: Are there any interesting mathematical principles that we can bring to bear on these questions, irrespective of the biological details? Of course there are!

Our first problem concerns an interesting mathematical conundrum that could arise in the case of three sexes. A new species of chameleon was discovered in the Southwestern United States on July 4, the first species found to have three sexes. This species has been aptly named Chamaeleo americanus patrioticus for reasons we specify below.

Problem 1

The adults of this Chamaeleo americanus patrioticus are colored fully red, white or blue, and this defines their sex at a given time. Being chameleons, however, they can and do change color, and therefore their sex. Specifically, when two differently colored individuals meet face to face, as happens quite frequently, they both change to the third color, as you can see in the illustration above. The chameleons retain this new color till the next such encounter with an individual of a different color. In effect, the color change is like blushing — a signal that says “not now.” There could be hundreds of such blushing encounters before the chameleons of two different colors are familiar enough to mate. What concerns us is that, for an animal breeder, this behavior can result in the dreaded problem of unicolorization before breeding can even start. If these color-changing encounters cause all your chameleons to change to the same color, you are out of luck — same-colored individuals cannot reproduce with each other. Whether unicolorization can happen or not in a given group of chameleons is crucially dependent on the number of individuals of each color that you start out with. Some sets of numbers almost invariably result in unicolorization of the group sooner or later, while others never do. Can you predict whether unicolorization can happen if you start with the numbers of these chameleons specified in A, B and C below, and if so, how?

A) 8 red, 5 white and 14 blue;

B) 9 red, 10 white and 16 blue

And finally, of course:

C) 7 red, 6 white and 50 blueBased on the above, can you figure out a general rule on how many individuals of each of the three colors you should start out with, so that the group is resistant to unicolorization?

As you’ve no doubt guessed, Chamaeleo americanus patrioticus is fictitious, a contrivance to present a mathematical principle — how something like parity can function when there are three different kinds of individuals. However, I do have a different, deep mathematical insight that sheds light on why animals that have two sexes are more successful than those that are asexual. To understand it, we need to make a little digression into some arithmetic. Consider the following simple problem, which has an “aha!”-inducing solution that I’d like you to discover for yourself. If you don’t get the insight right away, I’ve provided hints to help you get there. Below the hints, I will give you the correct answer, because it illuminates my mathematical argument that two sexes should exist. So only if you don’t find it for yourself, please do look at the answer.

Problem 2

Imagine all the human beings in the world (more than seven billion of them) standing in a line. Now multiply all the fingers on each of their hands. For the first person in line, you will multiply the five fingers on her left hand by the five on her right to get 25. You will then multiply this number by the five fingers on the left hand of your next person and then by five on his right hand and so on. Which of the following will approximate the final product after all the multiplications are done?

A) 5 to the 7 billion

B) 10 to the 7 billion

C) 5 to the 14 billion

D) Something else entirelyHint: This problem is not to test your arithmetic: it’s a trick question!

Hint: Some people may be missing fingers.

Hint: Some people may be missing a lot of their fingers!

Answer: The correct choice is D, and the answer to the problem is zero. As long as there is even one individual who has lost all his or her fingers on one hand, as there definitely is somewhere in the world, the product will come out to be zero.

This problem illustrates what I call “the fatal problem of serial multiplication” — the fact that a serial product can vanish because of a single multiplication by nothing. It’s a malady that mere addition doesn’t suffer from. And how does this relate to the problem of two sexes? Well, as we saw in the May insights column, Can Darwinian Evolution Explain Lamarckism?, evolutionary-fitness calculations over many generations are essentially serial multiplications. And there’s a key difference between asexual and sexual populations. As I mentioned in a comment on the May column, consider the fascinating statistic that 30 to 60 percent of the population of Europe was decimated by the bubonic plague (the Black Death) in the 14th century. What would the number have been if we were asexual creatures who were genetically very similar or identical to one another? 90 percent? 99 percent? Extinction? The different genetic makeup that each human being possesses, thanks to sexual reproduction, makes each of us react somewhat differently to parasites: some of us succumb, others may get a serious infection but survive, still others may escape with a mild infection. For asexual creatures, every individual reacts in the same way. For a parasite, this is equivalent to all the houses in the town using the same kind of lock. Find the key, and you hit the jackpot: you can literally make a killing!

We can simplistically define an animal’s fitness f as the number of adult offspring that it produces. Essentially, the population of a species in the next generation then is simply the starting population multiplied by f. The long-term population after n generations is simply a set of serial multiplications from one generation to another, with the average f varying from one generation to another based on the conditions. While it is true that asexual creatures will tend to have a higher f most of the time compared with sexual creatures, there will be some rare catastrophes when the number f falls for both species, but really plunges for asexual creatures for whom it may approach or reach zero. And when that happens, boom — extinction, in a single stroke!

Lizards are particularly good examples of this, as they are the most complex land animals that possess rare asexual species, such as the whiptail lizard in the Southwest United States, Mexico and South America. In lizard evolution, asexual species have arisen several times, but they are like short-lived twigs in the evolutionary tree. They go extinct far more quickly than sexual species. The few asexual species of lizards that still survive are those that have retained large amounts of genetic variation by tricks, such as doubling their normal number of chromosomes thanks to their sexual ancestors. In general, asexual species are subject to the fatal flaw of serial multiplication; sexual species are not. Our final problem explores this idea.

Problem 3

Imagine two species of lizards, one reproducing sexually and the other asexually. Imagine that they have reached somewhat stable populations to the limits of their available resources, so that their growth rates from generation to generation are only slightly above 1. The asexual species will still have a higher mean population growth rate, but this growth rate will also be more variable. Let’s say the mean population growth rate from one generation to the next for the sexual species is 1.1 with a standard deviation of 0.15, and the rate for the asexual species is 1.2 with a standard deviation of 0.3 (replace negative growth rates by zero). If you just considered the mean growth rates, the asexual species will have a population 20,000 times larger than that of the sexual species after a thousand generations. (As reader Joerg Fricke points out, this statement is true for growth rates of 1.01 and 1.02, which I intended to use, and not for 1.1 and 1.2. As Joerg rightly observes, 1.01 and 1.02 are more realistic. However, the problem as stated illustrates the intended principle.) But what happens when you factor in the larger growth-rate variability? Which species is more likely to become extinct sooner, and after how long, on average? If you’d like to be more realistic, you can add a random population growth or decrease of up to 10 percent every generation.

In keeping with the themes of this column, I hope you had a great July 4. And let’s all be thankful that we are not an asexual species.

Happy puzzling!

Editor’s note: The reader who submits the most interesting, creative or insightful solution (as judged by the columnist) in the comments section will receive a Quanta Magazine T-shirt. And if you’d like to suggest a favorite puzzle for a future Insights column, submit it as a comment below, clearly marked “NEW PUZZLE SUGGESTION.” (It will not appear online, so solutions to the puzzle above should be submitted separately.)

Note that we may hold comments for the first day or two to allow for independent contributions by readers.

Q&A with Nobel laureate Barry Barish

Barish explains how LIGO became the high-achieving experiment it is today.

These days the LIGO experiment seems almost unstoppable. In September 2015, LIGO detected gravitational waves directly for the first time in history. Afterward, they spotted them three times more, definitively blowing open the doors on the new field of gravitational-wave astronomy.

On October 3, the Nobel Committee awarded their 2017 prize in physics to some of the main engines behind the experiment. Just two weeks after that, LIGO scientists revealed that they'd seen, for the first time, gravitational waves from the collision of neutron stars, an event confirmed by optical telescopes—yet another first.

These recent achievements weren’t inevitable. It took LIGO scientists decades to get to this point.

LIGO leader Barry Barish, one of the three recipients of the 2017 Nobel, recently sat down with Symmetry writer Leah Hesla to give a behind-the-scenes look at his 22 years on the experiment.

What has been your role at LIGO?

I started in 1994 and came on board at a time when we didn’t have the money. I had to get the money and have a strategy that [the National Science Foundation] would buy into, and I had to have a plan that they would keep supporting for 22 years. My main mission was to build this instrument—which we didn’t know how to make—well enough to do what it did.

So we had to build enough trust and success without discovering gravitational waves so that NSF would keep supporting us. And we had to have the flexibility to evolve LIGO’s design, without costing an arm and a leg, to make the improvements that would eventually make it sensitive enough to succeed.

We started running in about 2000 and took data and improved the experiment over 10 years. But we just weren’t sensitive enough. We managed to get a major improvement program to what’s called Advanced LIGO from the National Science Foundation. After a year and a half or so of making it work, we turned on the device in September of 2015 and, within days, we’d made the detection.

What steps did LIGO take to be as sensitive as possible?

We were limited very much by the shaking of the Earth—at the low frequencies, the Earth just shakes too much. We also couldn’t get rid of the background noise at high frequencies—we can’t sample fast enough.

In the initial LIGO, we reduced the shaking by something like 100 million. We had the fanciest set of shock absorbers possible. The shock absorbers in your car take a bump that you go over, which is high-frequency, and transfer it softly to low-frequency. You get just a little up and down; you don’t feel very much when you go over a bump. You can’t get rid of the bump—that’s energy—but you can transfer it out of the frequencies where it bothers you.

So we do the same thing. We have a set of springs that are fancier but are basically like shock absorbers in your car. That gave us a factor of 100 million reduction in the shaking of the Earth.

But that wasn’t good enough [for initial LIGO].

What did you do to increase sensitivity for Advanced LIGO?

After 15 years of not being able to detect gravitational waves, we implemented what we call active seismic isolation, in addition to passive springs. It’s very much equivalent to what happens when you get on an airplane and you put those [noise cancellation] earphones on. All of a sudden the airplane is less noisy. That works by detecting the ambient noise—not the noise by the attendant dropping a glass or something. That’s a sharp noise, and you’d still hear that, or somebody talking to you, which is a loud independent noise. But the ambient noise of the motors and the shaking of the airplane itself are more or less the same now as they were a second ago, so if you measure the frequency of the ambient noise, you can cancel it.

In Advanced LIGO, we do the same thing. We measure the shaking of the Earth, and then we cancel it with active sensors. The only difference is that our problem is much harder. We have to do this directionally. The Earth shakes in a particular direction—it might be up and down, it might be sideways or at an angle. It took us years to develop this active seismic isolation.

The idea was there 15 years ago, but we had to do a lot of work to develop very, very sensitive active seismic isolation. The technology didn’t exist—we developed all that technology. It reduced the shaking of the Earth by another factor of 100 [over LIGO’s initial 100 million], so we reduced it by a factor of 10 billion.

So we could see a factor of 100 further out in the universe than we could have otherwise. And each factor of 10 gets cubed because we’re looking at stars and galaxies [in three dimensions]. So when we improved [initial LIGO’s sensitivity] by a factor of 100 beyond this already phenomenal number of 100 million, it improved our sensitivity immediately, and our rate of seeing these kinds of events, by a factor of a hundred cubed—by a million.

That’s why, after a few days of running, we saw something. We couldn’t have seen this in all the years that we ran at lower sensitivity.

What key steps did you take when you came on board in 1994?

First we had to build a kind of technical group that had the experience and abilities to take on a $100 million project. So I hired a lot of people. It was a good time to do that because it was soon after the closure of the Superconducting Super Collider in Texas. I knew some of the most talented people who were involved in that, so I brought them into LIGO, including the person who would be the project manager.

Second, I made sure the infrastructure was scaled to a stage where we were doing it not the cheapest we could, but rather the most flexible.

The third thing was to convince NSF that doing this construction project wasn’t the end of what we had to do in terms of development. So we put together a vigorous R&D program, which NSF supported, to develop the technology that would follow similar ones that we used.

And then there were some technical changes—to become as forward-looking as possible in terms of what we might need later.

What were the technical changes?

The first was to change from what was the most popularly used laser in the 1990s, which was a gas laser, to a solid-state laser, which was new at that time. The solid-state laser had the difficulty that the light was no longer in the visible range. It was in the infrared, and people weren’t used to interferometers like that. They like to have light bouncing around that they can see, but you can’t see the solid-state laser light with your naked eye. That’s like particle physics. You can’t see the particles in the accelerator either. We use sensors to do that. So we made that kind of change, going from analog controls to digital controls, which are computer-based.

We also inherited the kind of control programs that had been developed for accelerators and used at the Superconducting Super Collider, and we brought the SSC controls people into LIGO. These changes didn’t pay off immediately, but paved the road toward making a device that could be modern and not outdated as we moved through the 20 years. It wasn’t so much fixing things as making LIGO much more forward-looking—to make it more and more sensitive, which is the key thing for us.

Did you draw on past experience?

I think my history in particle physics was crucial in many ways, for example, in technical ways—things like digital controls, how we monitored beam. We don’t use the same technology, but the idea that you don’t have to see it physically to monitor it—those kinds of things carried over.

The organization, how we have scientific collaborations, was again something that I created here at LIGO, which was modeled after high-energy physics collaborations. Some of it has to be modified for this different kind of project—this is not an accelerator—but it has a lot of similarities because of the way you approach a large scientific project.

Were you concerned the experiment wouldn’t happen? If not, what did concern you?

As long as we kept making technical progress, I didn’t have that concern. My only real concern was nature. Would we be fortunate enough to see gravitational waves at the sensitivities we could get to? It wasn’t predicted totally. There were optimistic predictions—that we could have detected things earlier — but there are also predictions we haven't gotten to. So my main concern was nature.

When did you hear about the first detection of gravitational waves?

If you see gravitational waves from some spectacular thing, you’d also like to be able to see something in telescopes and electromagnetic astronomy that’s correlated. So because of that, LIGO has an early alarm system that alerts you that there might be a gravitational wave event. We more or less have the ability to see spectacular things early. But if you want people to turn their telescopes or other devices to point at something in the sky, you have to tell them something in time scales of minutes or hours, not weeks or months.

The day we saw this, which we saw early in its running, it happened at 4:50 in the morning in Louisiana, 2:50 in the morning in California, so I found out about it at breakfast time for me, which was about four hours later. When we alert the astronomers, we alert key people from LIGO as well. We get things like that all the time, but this looked a little more serious than others. After a few more hours that day, it became clear that this was nothing like anything we’d seen before, and in fact looked a lot like what we were looking for, and so I would say some people became convinced within hours.

I wasn’t, but that’s my own conservatism: What’s either fooling us or how are we fooling ourselves? There were two main issues. One is the possibility that maybe somebody was inserting a rogue event in our data, some malicious way to try to fool us. We had to make sure we could trace the history of the events from the apparatus itself and make sure there was no possibility that somebody could do this. That took about a month of work. The second was that LIGO was a brand new, upgraded version, so I wasn’t sure that there weren’t new ways to generate things that would fool us. Although we had a lot of experience over a lot of years, it wasn’t really with this version of LIGO. This version was only a few days old. So it took us another month or so to convince us that it was real. It was obvious that there was going to be a classic discovery if it held up.

What does it feel like to win the Nobel Prize?

It happened at 3 in the morning here [in California]. [The night before], I had a nice dinner with my wife, and we went to bed early. I set the alarm for 2:40. They were supposed to announce the result at 2:45. I don’t know why I set it for 2:40, but I did. I moved the house phone into our bedroom.

The alarm did go off at 2:40. There was no call, obviously—I hadn’t been awakened, so I assumed, kind of in my groggy state, that we must have been passed over. I started going to my laptop to see who was going to get it. Then my cell phone started ringing. My wife heard it. My cell phone number is not given out, generally. There are tens of people who have it, but how [the Nobel Foundation] got it, I’m not sure. Some colleague, I suppose. It was a surprise to me that it came on the cell phone.

The president of the Nobel Foundation told me who he was, said he had good news and told me I won. And then we chatted for a few minutes, and he asked me how I felt. And I spontaneously said that I felt “thrilled and humbled at the same time.” There’s no word for that, exactly, but that mixture of feeling is what I had and still have.

Do you have advice for others organizing big science projects?

We have an opportunity. As I grew into this and as science grew big, we always had to push and push and push on technology, and we’ve certainly done that on LIGO. We do that in particle physics, we do that in accelerators.

I think the table has turned somewhat and that the technology has grown so fast in the recent decades that there’s incredible opportunities to do new science. The development of new technologies gives us so much ability to ask difficult scientific questions. We’re in an era that I think is going to propagate fantastically into the future.

Just in the new millennium, maybe the three most important discoveries in physics have all been done with, I would say, high-tech, modern, large-scale devices: the neutrino experiments at SNO and Kamiokande doing the neutrino oscillations, which won a Nobel Prize in 2013; the Higgs boson—no device is more complicated or bigger or more technically advanced than the CERN LHC experiments; and then ours, which is not quite the scale of the LHC, but it’s the same scale as these experiments—the billion dollar scale—and it’s very high-tech.

Einstein thought that gravitational waves could never be detected, but he didn’t know about lasers, digital controls and active seismic isolation and all things that we developed, all the high-tech things that are coming from industry and our pushing them a little bit harder.

The fact is, technology is changing so fast. Most of us can’t live without GPS, and 10 or 15 years ago, we didn’t have GPS. GPS exists because of general relativity, which is what I do. The inner silicon microstrip detectors in the CERN experiment were developed originally for particle physics. They developed rapidly. But now, they’re way behind what’s being done in industry in the same area. Our challenge is to learn how to grab what is being developed, because technology is becoming great.

I think we need to become really aware and understand the developments of technology and how to apply those to the most basic physics questions that we have and do it in a forward-looking way.

What are your hopes for the future of LIGO?

It’s fantastic. For LIGO itself, we’re not limited by anything in nature. We’re limited by ourselves in terms of improving it over the next 15 years, just like we improved in going from initial LIGO to Advanced LIGO. We’re not at the limit.

So we can look forward to certainly a factor of 2 to 3 improvement, which we’ve already been funded for and are ready for, and that will happen over the next few years. And that factor of 2 or 3 gets cubed in our case.

This represents a completely new way to look at the universe. Everything we look at was with electromagnetic radiation, and a little bit with neutrinos, until we came along. We know that only a few percent of what’s out there is luminous, and so we are opening a new age of astronomy, really. At the same time, we’re able to test Einstein’s theories of general relativity in its most important way, which is by looking where the fields are the strongest, around black holes.

That’s the opportunity that exists over a long time scale with gravitational waves. The fact that they’re a totally different way of looking at the sky means that in the long term it will develop into an important part of how we understand our universe and where we came from. Gravitational waves are the best way possible, in theory—we can’t do it now—of going back to the very beginning, the Big Bang, because they weren’t absorbed. What we know now comes from photons, but they can go back to only 300,000 years from the Big Bang because they’re absorbed.

We can go back to the beginning. We don’t know how to do it yet, but that is the potential.

The Fermi Paradox

Everyone feels something when they’re in a really good starry place on a really good starry night and they look up and see this:

Some people stick with the traditional, feeling struck by the epic beauty or blown away by the insane scale of the universe. Personally, I go for the old “existential meltdown followed by acting weird for the next half hour.” But everyone feels something.

Physicist Enrico Fermi felt something too—”Where is everybody?”

________________

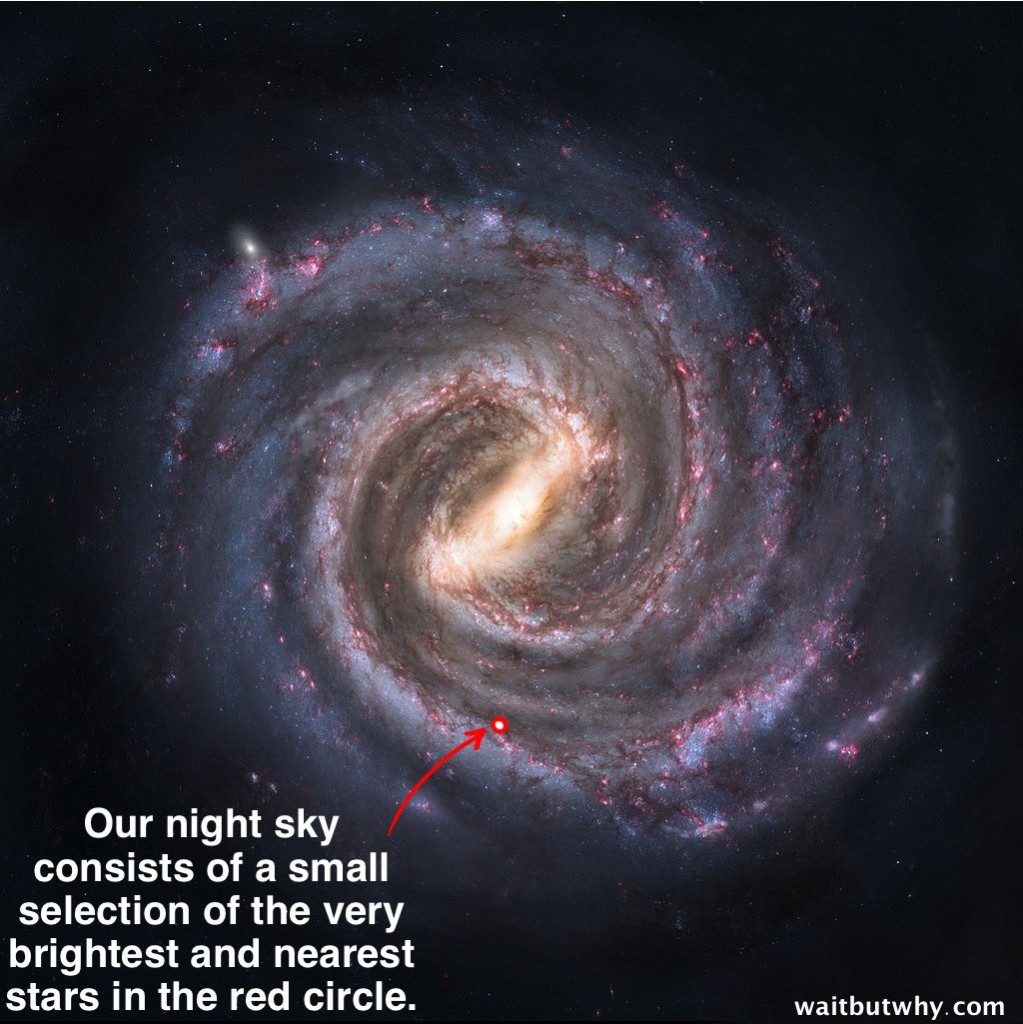

A really starry sky seems vast—but all we’re looking at is our very local neighborhood. On the very best nights, we can see up to about 2,500 stars (roughly one hundred-millionth of the stars in our galaxy), and almost all of them are less than 1,000 light years away from us (or 1% of the diameter of the Milky Way). So what we’re really looking at is this:

When confronted with the topic of stars and galaxies, a question that tantalizes most humans is, “Is there other intelligent life out there?” Let’s put some numbers to it (if you don’t like numbers, just read the bold)—

As many stars as there are in our galaxy (100 – 400 billion), there are roughly an equal number of galaxies in the observable universe—so for every star in the colossal Milky Way, there’s a whole galaxy out there. All together, that comes out to the typically quoted range of between 1022 and 1024 total stars, which means that for every grain of sand on Earth, there are 10,000 stars out there.

The science world isn’t in total agreement about what percentage of those stars are “sun-like” (similar in size, temperature, and luminosity)—opinions typically range from 5% to 20%. Going with the most conservative side of that (5%), and the lower end for the number of total stars (1022), gives us 500 quintillion, or 500 billion billion sun-like stars.

There’s also a debate over what percentage of those sun-like stars might be orbited by an Earth-like planet (one with similar temperature conditions that could have liquid water and potentially support life similar to that on Earth). Some say it’s as high as 50%, but let’s go with the more conservative 22% that came out of a recent PNAS study. That suggests that there’s a potentially-habitable Earth-like planet orbiting at least 1% of the total stars in the universe—a total of 100 billion billion Earth-like planets.

So there are 100 Earth-like planets for every grain of sand in the world. Think about that next time you’re on the beach.

Moving forward, we have no choice but to get completely speculative. Let’s imagine that after billions of years in existence, 1% of Earth-like planets develop life (if that’s true, every grain of sand would represent one planet with life on it). And imagine that on 1% of those planets, the life advances to an intelligent level like it did here on Earth. That would mean there were 10 quadrillion, or 10 million billion intelligent civilizations in the observable universe.

Moving back to just our galaxy, and doing the same math on the lowest estimate for stars in the Milky Way (100 billion), we’d estimate that there are 1 billion Earth-like planets and 100,000 intelligent civilizations in our galaxy.[1]The Drake Equation provides a formal method for this narrowing-down process we’re doing.

SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) is an organization dedicated to listening for signals from other intelligent life. If we’re right that there are 100,000 or more intelligent civilizations in our galaxy, and even a fraction of them are sending out radio waves or laser beams or other modes of attempting to contact others, shouldn’t SETI’s satellite array pick up all kinds of signals?

But it hasn’t. Not one. Ever.

Where is everybody?

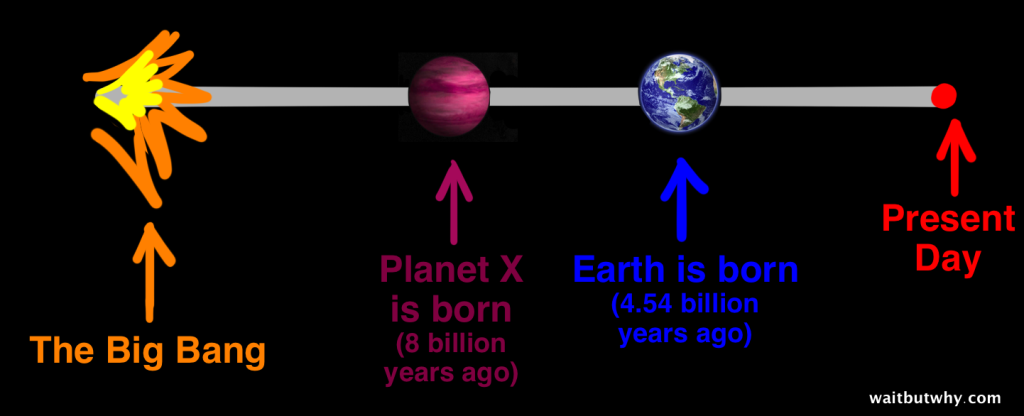

It gets stranger. Our sun is relatively young in the lifespan of the universe. There are far older stars with far older Earth-like planets, which should in theory mean civilizations far more advanced than our own. As an example, let’s compare our 4.54 billion-year-old Earth to a hypothetical 8 billion-year-old Planet X.

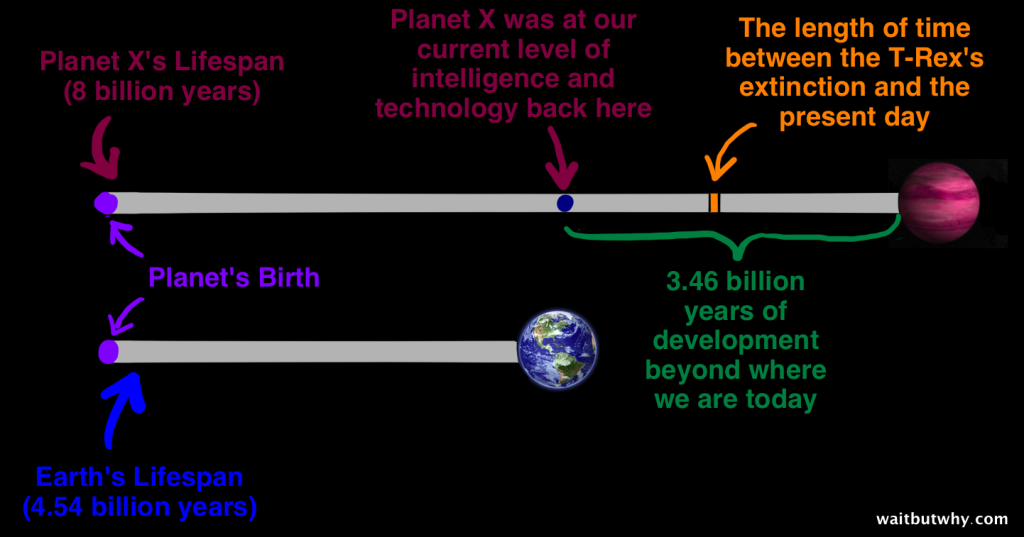

If Planet X has a similar story to Earth, let’s look at where their civilization would be today (using the orange timespan as a reference to show how huge the green timespan is):

The technology and knowledge of a civilization only 1,000 years ahead of us could be as shocking to us as our world would be to a medieval person. A civilization 1 million years ahead of us might be as incomprehensible to us as human culture is to chimpanzees. And Planet X is 3.4 billion years ahead of us…

There’s something called The Kardashev Scale, which helps us group intelligent civilizations into three broad categories by the amount of energy they use:

A Type I Civilization has the ability to use all of the energy on their planet. We’re not quite a Type I Civilization, but we’re close (Carl Sagan created a formula for this scale which puts us at a Type 0.7 Civilization).

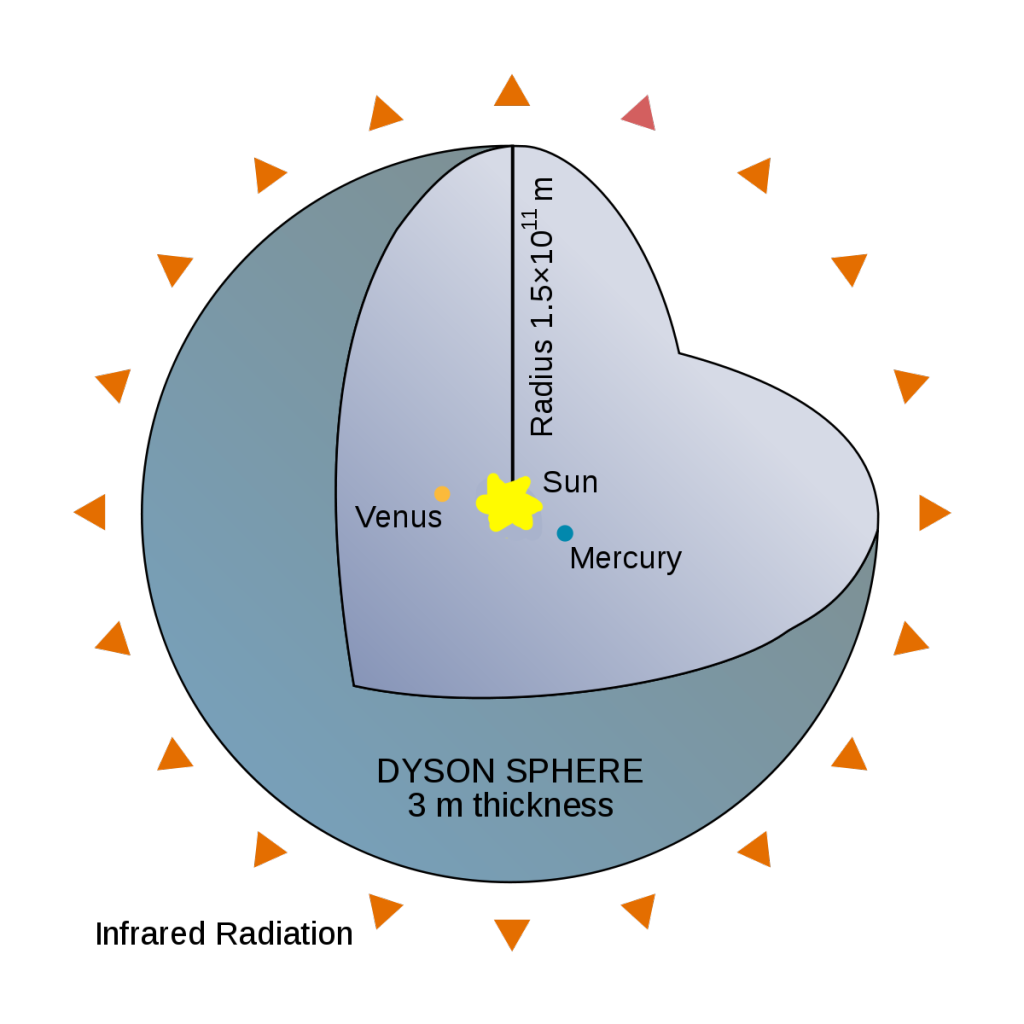

A Type II Civilization can harness all of the energy of their host star. Our feeble Type I brains can hardly imagine how someone would do this, but we’ve tried our best, imagining things like a Dyson Sphere.

A Type III Civilization blows the other two away, accessing power comparable to that of the entire Milky Way galaxy.

If this level of advancement sounds hard to believe, remember Planet X above and their 3.4 billion years of further development. If a civilization on Planet X were similar to ours and were able to survive all the way to Type III level, the natural thought is that they’d probably have mastered inter-stellar travel by now, possibly even colonizing the entire galaxy.

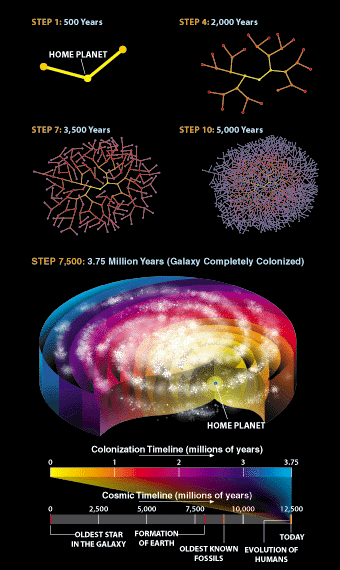

One hypothesis as to how galactic colonization could happen is by creating machinery that can travel to other planets, spend 500 years or so self-replicating using the raw materials on their new planet, and then send two replicas off to do the same thing. Even without traveling anywhere near the speed of light, this process would colonize the whole galaxy in 3.75 million years, a relative blink of an eye when talking in the scale of billions of years:

Source: Scientific American: “Where Are They”

Continuing to speculate, if 1% of intelligent life survives long enough to become a potentially galaxy-colonizing Type III Civilization, our calculations above suggest that there should be at least 1,000 Type III Civilizations in our galaxy alone—and given the power of such a civilization, their presence would likely be pretty noticeable. And yet, we see nothing, hear nothing, and we’re visited by no one.

So where is everybody?

_____________________

Welcome to the Fermi Paradox.

We have no answer to the Fermi Paradox—the best we can do is “possible explanations.” And if you ask ten different scientists what their hunch is about the correct one, you’ll get ten different answers. You know when you hear about humans of the past debating whether the Earth was round or if the sun revolved around the Earth or thinking that lightning happened because of Zeus, and they seem so primitive and in the dark? That’s about where we are with this topic.

In taking a look at some of the most-discussed possible explanations for the Fermi Paradox, let’s divide them into two broad categories—those explanations which assume that there’s no sign of Type II and Type III Civilizations because there are none of them out there, and those which assume they’re out there and we’re not seeing or hearing anything for other reasons:

Explanation Group 1: There are no signs of higher (Type II and III) civilizations because there are no higher civilizations in existence.

Those who subscribe to Group 1 explanations point to something called the non-exclusivity problem, which rebuffs any theory that says, “There are higher civilizations, but none of them have made any kind of contact with us because they all _____.” Group 1 people look at the math, which says there should be so many thousands (or millions) of higher civilizations, that at least one of them would be an exception to the rule. Even if a theory held for 99.99% of higher civilizations, the other .01% would behave differently and we’d become aware of their existence.

Therefore, say Group 1 explanations, it must be that there are no super-advanced civilizations. And since the math suggests that there are thousands of them just in our own galaxy, something else must be going on.

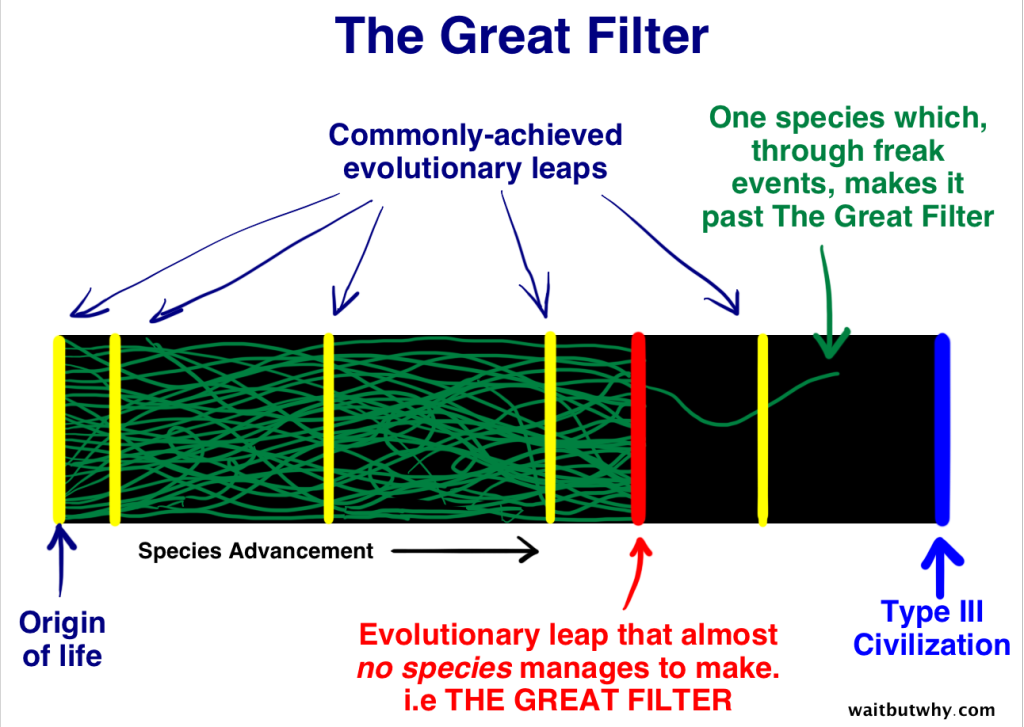

This something else is called The Great Filter.

The Great Filter theory says that at some point from pre-life to Type III intelligence, there’s a wall that all or nearly all attempts at life hit. There’s some stage in that long evolutionary process that is extremely unlikely or impossible for life to get beyond. That stage is The Great Filter.

If this theory is true, the big question is, Where in the timeline does the Great Filter occur?

It turns out that when it comes to the fate of humankind, this question is very important. Depending on where The Great Filter occurs, we’re left with three possible realities: We’re rare, we’re first, or we’re fucked.

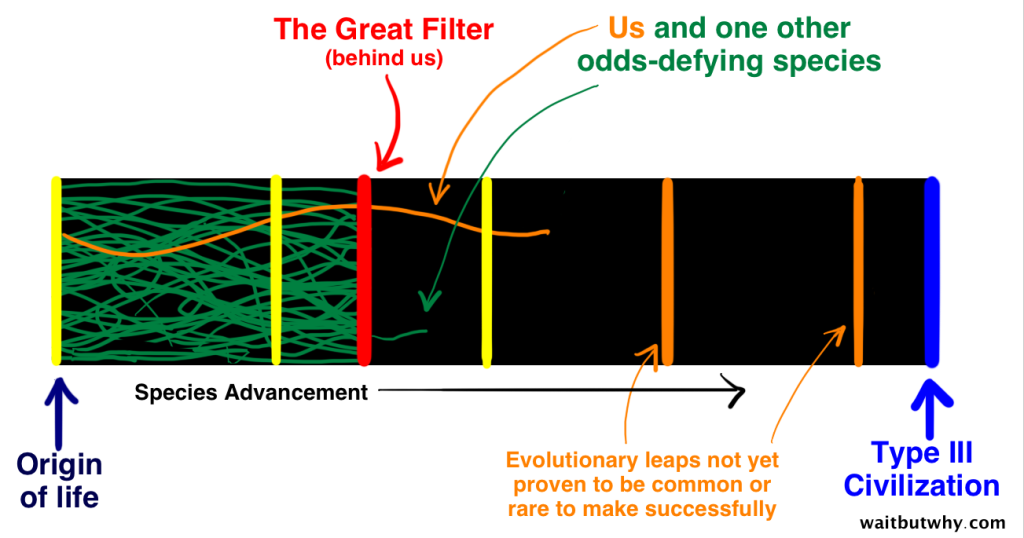

1. We’re Rare (The Great Filter is Behind Us)

One hope we have is that The Great Filter is behind us—we managed to surpass it, which would mean it’s extremely rare for life to make it to our level of intelligence. The diagram below shows only two species making it past, and we’re one of them.

This scenario would explain why there are no Type III Civilizations…but it would also mean that we could be one of the few exceptions now that we’ve made it this far. It would mean we have hope. On the surface, this sounds a bit like people 500 years ago suggesting that the Earth is the center of the universe—it implies that we’re special. However, something scientists call “observation selection effect” suggests that anyone who is pondering their own rarity is inherently part of an intelligent life “success story”—and whether they’re actually rare or quite common, the thoughts they ponder and conclusions they draw will be identical. This forces us to admit that being special is at least a possibility.

And if we are special, when exactly did we become special—i.e. which step did we surpass that almost everyone else gets stuck on?

One possibility: The Great Filter could be at the very beginning—it might be incredibly unusual for life to begin at all. This is a candidate because it took about a billion years of Earth’s existence to finally happen, and because we have tried extensively to replicate that event in labs and have never been able to do it. If this is indeed The Great Filter, it would mean that not only is there no intelligent life out there, there may be no other life at all.

Another possibility: The Great Filter could be the jump from the simple prokaryote cell to the complex eukaryote cell. After prokaryotes came into being, they remained that way for almost two billion years before making the evolutionary jump to being complex and having a nucleus. If this is The Great Filter, it would mean the universe is teeming with simple prokaryote cells and almost nothing beyond that.

There are a number of other possibilities—some even think the most recent leap we’ve made to our current intelligence is a Great Filter candidate. While the leap from semi-intelligent life (chimps) to intelligent life (humans) doesn’t at first seem like a miraculous step, Steven Pinker rejects the idea of an inevitable “climb upward” of evolution: “Since evolution does not strive for a goal but just happens, it uses the adaptation most useful for a given ecological niche, and the fact that, on Earth, this led to technological intelligence only once so far may suggest that this outcome of natural selection is rare and hence by no means a certain development of the evolution of a tree of life.”

Most leaps do not qualify as Great Filter candidates. Any possible Great Filter must be one-in-a-billion type thing where one or more total freak occurrences need to happen to provide a crazy exception—for that reason, something like the jump from single-cell to multi-cellular life is ruled out, because it has occurred as many as 46 times, in isolated incidents, just on this planet alone. For the same reason, if we were to find a fossilized eukaryote cell on Mars, it would rule the above “simple-to-complex cell” leap out as a possible Great Filter (as well as anything before that point on the evolutionary chain)—because if it happened on both Earth and Mars, it’s almost definitely not a one-in-a-billion freak occurrence.

If we are indeed rare, it could be because of a fluky biological event, but it also could be attributed to what is called the Rare Earth Hypothesis, which suggests that though there may be many Earth-like planets, the particular conditions on Earth—whether related to the specifics of this solar system, its relationship with the moon (a moon that large is unusual for such a small planet and contributes to our particular weather and ocean conditions), or something about the planet itself—are exceptionally friendly to life.

2. We’re the First

For Group 1 Thinkers, if the Great Filter is not behind us, the one hope we have is that conditions in the universe are just recently, for the first time since the Big Bang, reaching a place that would allow intelligent life to develop. In that case, we and many other species may be on our way to super-intelligence, and it simply hasn’t happened yet. We happen to be here at the right time to become one of the first super-intelligent civilizations.

One example of a phenomenon that could make this realistic is the prevalence of gamma-ray bursts, insanely huge explosions that we’ve observed in distant galaxies. In the same way that it took the early Earth a few hundred million years before the asteroids and volcanoes died down and life became possible, it could be that the first chunk of the universe’s existence was full of cataclysmic events like gamma-ray bursts that would incinerate everything nearby from time to time and prevent any life from developing past a certain stage. Now, perhaps, we’re in the midst of an astrobiological phase transition and this is the first time any life has been able to evolve for this long, uninterrupted.

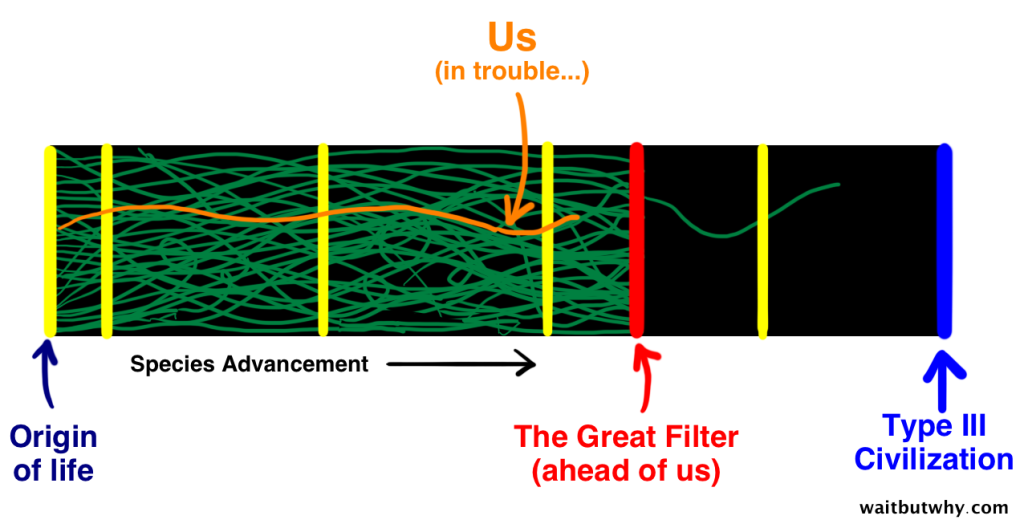

3. We’re Fucked (The Great Filter is Ahead of Us)

If we’re neither rare nor early, Group 1 thinkers conclude that The Great Filter must be in our future. This would suggest that life regularly evolves to where we are, but that something prevents life from going much further and reaching high intelligence in almost all cases—and we’re unlikely to be an exception.

One possible future Great Filter is a regularly-occurring cataclysmic natural event, like the above-mentioned gamma-ray bursts, except they’re unfortunately not done yet and it’s just a matter of time before all life on Earth is suddenly wiped out by one. Another candidate is the possible inevitability that nearly all intelligent civilizations end up destroying themselves once a certain level of technology is reached.

This is why Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom says that “no news is good news.” The discovery of even simple life on Mars would be devastating, because it would cut out a number of potential Great Filters behind us. And if we were to find fossilized complex life on Mars, Bostrom says “it would be by far the worst news ever printed on a newspaper cover,” because it would mean The Great Filter is almost definitely ahead of us—ultimately dooming the species. Bostrom believes that when it comes to The Fermi Paradox, “the silence of the night sky is golden.”

Explanation Group 2: Type II and III intelligent civilizations are out there—and there are logical reasons why we might not have heard from them.

Group 2 explanations get rid of any notion that we’re rare or special or the first at anything—on the contrary, they believe in the Mediocrity Principle, whose starting point is that there is nothing unusual or rare about our galaxy, solar system, planet, or level of intelligence, until evidence proves otherwise. They’re also much less quick to assume that the lack of evidence of higher intelligence beings is evidence of their nonexistence—emphasizing the fact that our search for signals stretches only about 100 light years away from us (0.1% across the galaxy) and suggesting a number of possible explanations. Here are 10:

Possibility 1) Super-intelligent life could very well have already visited Earth, but before we were here. In the scheme of things, sentient humans have only been around for about 50,000 years, a little blip of time. If contact happened before then, it might have made some ducks flip out and run into the water and that’s it. Further, recorded history only goes back 5,500 years—a group of ancient hunter-gatherer tribes may have experienced some crazy alien shit, but they had no good way to tell anyone in the future about it.

Possibility 2) The galaxy has been colonized, but we just live in some desolate rural area of the galaxy. The Americas may have been colonized by Europeans long before anyone in a small Inuit tribe in far northern Canada realized it had happened. There could be an urbanization component to the interstellar dwellings of higher species, in which all the neighboring solar systems in a certain area are colonized and in communication, and it would be impractical and purposeless for anyone to deal with coming all the way out to the random part of the spiral where we live.

Possibility 3) The entire concept of physical colonization is a hilariously backward concept to a more advanced species. Remember the picture of the Type II Civilization above with the sphere around their star? With all that energy, they might have created a perfect environment for themselves that satisfies their every need. They might have crazy-advanced ways of reducing their need for resources and zero interest in leaving their happy utopia to explore the cold, empty, undeveloped universe.

An even more advanced civilization might view the entire physical world as a horribly primitive place, having long ago conquered their own biology and uploaded their brains to a virtual reality, eternal-life paradise. Living in the physical world of biology, mortality, wants, and needs might seem to them the way we view primitive ocean species living in the frigid, dark sea. FYI, thinking about another life form having bested mortality makes me incredibly jealous and upset.

Possibility 4) There are scary predator civilizations out there, and most intelligent life knows better than to broadcast any outgoing signals and advertise their location. This is an unpleasant concept and would help explain the lack of any signals being received by the SETI satellites. It also means that we might be the super naive newbies who are being unbelievably stupid and risky by ever broadcasting outward signals. There’s a debate going on currently about whether we should engage in METI (Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence—the reverse of SETI) or not, and most people say we should not. Stephen Hawking warns, “If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans.” Even Carl Sagan (a general believer that any civilization advanced enough for interstellar travel would be altruistic, not hostile) called the practice of METI “deeply unwise and immature,” and recommended that “the newest children in a strange and uncertain cosmos should listen quietly for a long time, patiently learning about the universe and comparing notes, before shouting into an unknown jungle that we do not understand.” Scary.[2]Thinking about this logically, I think we should disregard all the warnings get the outgoing signals rolling. If we catch the attention of super-advanced beings, yes, they might decide to wipe out our whole existence, but that’s not that different than our current fate (to each die within a century). And maybe, instead, they’d invite us to upload our brains into their eternal virtual utopia, which would solve the death problem and also probably allow me to achieve my childhood dream of bouncing around on the clouds. Sounds like a good gamble to me.

Possibility 5) There’s only one instance of higher-intelligent life—a “superpredator” civilization (like humans are here on Earth)—who is far more advanced than everyone else and keeps it that way by exterminating any intelligent civilization once they get past a certain level. This would suck. The way it might work is that it’s an inefficient use of resources to exterminate all emerging intelligences, maybe because most die out on their own. But past a certain point, the super beings make their move—because to them, an emerging intelligent species becomes like a virus as it starts to grow and spread. This theory suggests that whoever was the first in the galaxy to reach intelligence won, and now no one else has a chance. This would explain the lack of activity out there because it would keep the number of super-intelligent civilizations to just one.

Possibility 6) There’s plenty of activity and noise out there, but our technology is too primitive and we’re listening for the wrong things. Like walking into a modern-day office building, turning on a walkie-talkie, and when you hear no activity (which of course you wouldn’t hear because everyone’s texting, not using walkie-talkies), determining that the building must be empty. Or maybe, as Carl Sagan has pointed out, it could be that our minds work exponentially faster or slower than another form of intelligence out there—e.g. it takes them 12 years to say “Hello,” and when we hear that communication, it just sounds like white noise to us.

Possibility 7) We are receiving contact from other intelligent life, but the government is hiding it. This is an idiotic theory, but I had to mention it because it’s talked about so much.

Possibility 8) Higher civilizations are aware of us and observing us (AKA the “Zoo Hypothesis”). As far as we know, super-intelligent civilizations exist in a tightly-regulated galaxy, and our Earth is treated like part of a vast and protected national park, with a strict “Look but don’t touch” rule for planets like ours. We wouldn’t notice them, because if a far smarter species wanted to observe us, it would know how to easily do so without us realizing it. Maybe there’s a rule similar to the Star Trek’s “Prime Directive” which prohibits super-intelligent beings from making any open contact with lesser species like us or revealing themselves in any way, until the lesser species has reached a certain level of intelligence.

Possibility 9) Higher civilizations are here, all around us. But we’re too primitive to perceive them. Michio Kaku sums it up like this:

Lets say we have an ant hill in the middle of the forest. And right next to the ant hill, they’re building a ten-lane super-highway. And the question is “Would the ants be able to understand what a ten-lane super-highway is? Would the ants be able to understand the technology and the intentions of the beings building the highway next to them?

So it’s not that we can’t pick up the signals from Planet X using our technology, it’s that we can’t even comprehend what the beings from Planet X are or what they’re trying to do. It’s so beyond us that even if they really wanted to enlighten us, it would be like trying to teach ants about the internet.

Along those lines, this may also be an answer to “Well if there are so many fancy Type III Civilizations, why haven’t they contacted us yet?” To answer that, let’s ask ourselves—when Pizarro made his way into Peru, did he stop for a while at an anthill to try to communicate? Was he magnanimous, trying to help the ants in the anthill? Did he become hostile and slow his original mission down in order to smash the anthill apart? Or was the anthill of complete and utter and eternal irrelevance to Pizarro? That might be our situation here.

Possibility 10) We’re completely wrong about our reality. There are a lot of ways we could just be totally off with everything we think. The universe might appear one way and be something else entirely, like a hologram. Or maybe we’re the aliens and we were planted here as an experiment or as a form of fertilizer. There’s even a chance that we’re all part of a computer simulation by some researcher from another world, and other forms of life simply weren’t programmed into the simulation.

________________

As we continue along with our possibly-futile search for extraterrestrial intelligence, I’m not really sure what I’m rooting for. Frankly, learning either that we’re officially alone in the universe or that we’re officially joined by others would be creepy, which is a theme with all of the surreal storylines listed above—whatever the truth actually is, it’s mindblowing.

Beyond its shocking science fiction component, The Fermi Paradox also leaves me with a deep humbling. Not just the normal “Oh yeah, I’m microscopic and my existence lasts for three seconds” humbling that the universe always triggers. The Fermi Paradox brings out a sharper, more personal humbling, one that can only happen after spending hours of research hearing your species’ most renowned scientists present insane theories, change their minds again and again, and wildly contradict each other—reminding us that future generations will look at us the same way we see the ancient people who were sure that the stars were the underside of the dome of heaven, and they’ll think “Wow they really had no idea what was going on.”

Compounding all of this is the blow to our species’ self-esteem that comes with all of this talk about Type II and III Civilizations. Here on Earth, we’re the king of our little castle, proud ruler of the huge group of imbeciles who share the planet with us. And in this bubble with no competition and no one to judge us, it’s rare that we’re ever confronted with the concept of being a dramatically inferior species to anyone. But after spending a lot of time with Type II and III Civilizations over the past week, our power and pride are seeming a bit David Brent-esque.

That said, given that my normal outlook is that humanity is a lonely orphan on a tiny rock in the middle of a desolate universe, the humbling fact that we’re probably not as smart as we think we are, and the possibility that a lot of what we’re sure about might be wrong, sounds wonderful. It opens the door just a crack that maybe, just maybe, there might be more to the story than we realize.

To humble you further:

More from Wait But Why:

Why Generation Y Yuppies Are Unhappy

7 Ways to be Insufferable on Facebook

Why Procrastinators Procrastinate

How to Name a Baby

How to Pick Your Life Partner

Your Life in Weeks

10 Types of 30-Year-Old Single Guys

The Great Perils of Social Interaction

Sources:

PNAS: Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars

SETI: The Drake Equation

NASA: Workshop Report on the Future of Intelligence In The Cosmos

Keith Wiley: The Fermi Paradox, Self-Replicating Probes, and the Interstellar Transportation Bandwidth

NCBI: Astrobiological phase transition: towards resolution of Fermi’s paradox

André Kukla: Extraterrestrials: A Philosophical Perspective

Nick Bostrom: Where Are They?

Science Direct: Galactic gradients, postbiological evolution and the apparent failure of SETI

Nature: Simulations back up theory that Universe is a hologram

Robin Hanson: The Great Filter – Are We Almost Past It?

John Dyson: Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation

The post The Fermi Paradox appeared first on Wait But Why.

Astrophoto: Hubble in the Bubble

The Bubble Nebula, also known as NGC 7635, seen in the Hubble Palette. Credit and copyright: Terry Hancock.

Here’s a beautiful look at the Bubble Nebula, taken by astrophotographer Terry Hancock using what’s known as the “Hubble Palette,” — imaging in very narrow wavelengths of light using various filters. This allows very subtle details to be revealed, things that the human eye cannot see. Terry has been working on this one for a while — since mid-August — but the results are spectacular!

Terry took images from his “DownUnder Observatory” in Fremont, Michigan. He explains the image and techniques he used:

(...)

Read the rest of Astrophoto: Hubble in the Bubble (179 words)

© nancy for Universe Today, 2013. |

Permalink |

No comment |

Post tags: Astrophotos, Bubble Nebula

Feed enhanced by Better Feed from Ozh

Titan’s North Pole is Loaded With Lakes

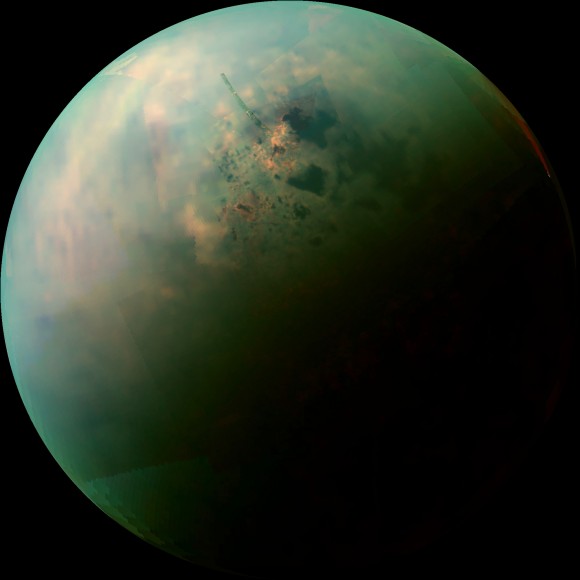

Mosaic of near-infrared images from Cassini showing lakes on Titan’s north pole (NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI)

A combination of exceptionally clear weather, the steady approach of northern summer, and a poleward orbital path has given Cassini — and Cassini scientists — unprecedented views of countless lakes scattered across Titan’s north polar region. In the near-infrared mosaic above they can be seen as dark splotches and speckles scattered around the moon’s north pole. Previously observed mainly via radar, these are the best visual and infrared wavelength images ever obtained of Titan’s northern “land o’ lakes!”

(...)

Read the rest of Titan’s North Pole is Loaded With Lakes (717 words)

© Jason Major for Universe Today, 2013. |

Permalink |

No comment |

Post tags: Carolyn Porco, Cassini, CICLOPS, Kraken Mare, lakes, Moon, NASA, Saturn, Solar System, Titan

Feed enhanced by Better Feed from Ozh

Weekend Comet Bonanza!

Astrophotographers were out in full force this weekend to try and capture the bonanza of comets now visible in the early morning skies! You’ll need a good-sized telescope to see these comets for yourself, however, but with the Moon now waning means darker skies and better observing conditions. Above is an absolutely gorgeous image of Comet ISON taken by Damian Peach. See below for more images of not only Comet ISON, but also Comet Encke, Comet Lovejoy and Comet LINEAR — now in outburst.

In fact, one of our “regular” contributors, John Chumack, captured all four comets in one morning, on Saturday October 26!

(...)

Read the rest of Weekend Comet Bonanza! (645 words)

© nancy for Universe Today, 2013. |

Permalink |

11 comments |

Post tags: Astrophotos, Comet Encke, Comet ISON, Comet LINEAR, Comet Lovejoy, Comets

Feed enhanced by Better Feed from Ozh

Google Street View goes underground at LHC

A virtual tour of the Large Hadron Collider and the ATLAS, CMS, LHCb and ALICE experiments is now available on Google Street View.

Visitors all over the world can now explore CERN’s massive detectors and 1200 meters of the Large Hadron Collider tunnel with Google Street View—a Google product that links a series of panoramic photos into a virtual tour.