by Abrahm Lustgarten

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This article, the first in a series on global climate migration, is a partnership between ProPublica and The New York Times Magazine, with support from the Pulitzer Center. Read more about the data project that underlies the reporting.

Early in 2019, a year before the world shut its borders completely, Jorge A. knew he had to get out of Guatemala. The land was turning against him. For five years, it almost never rained. Then it did rain, and Jorge rushed his last seeds into the ground. The corn sprouted into healthy green stalks, and there was hope — until, without warning, the river flooded. Jorge waded chest-deep into his fields searching in vain for cobs he could still eat. Soon he made a last desperate bet, signing away the tin-roof hut where he lived with his wife and three children against a $1,500 advance in okra seed. But after the flood, the rain stopped again, and everything died. Jorge knew then that if he didn’t get out of Guatemala, his family might die, too.

Even as hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans fled north toward the United States in recent years, in Jorge’s region — a state called Alta Verapaz, where precipitous mountains covered in coffee plantations and dense, dry forest give way to broader gentle valleys — the residents have largely stayed. Now, though, under a relentless confluence of drought, flood, bankruptcy and starvation, they, too, have begun to leave. Almost everyone here experiences some degree of uncertainty about where their next meal will come from. Half the children are chronically hungry, and many are short for their age, with weak bones and bloated bellies. Their families are all facing the same excruciating decision that confronted Jorge.

The odd weather phenomenon that many blame for the suffering here — the drought and sudden storm pattern known as El Niño — is expected to become more frequent as the planet warms. Many semiarid parts of Guatemala will soon be more like a desert. Rainfall is expected to decrease by 60% in some parts of the country, and the amount of water replenishing streams and keeping soil moist will drop by as much as 83%. Researchers project that by 2070, yields of some staple crops in the state where Jorge lives will decline by nearly a third.

Scientists have learned to project such changes around the world with surprising precision, but — until recently — little has been known about the human consequences of those changes. As their land fails them, hundreds of millions of people from Central America to Sudan to the Mekong Delta will be forced to choose between flight or death. The result will almost certainly be the greatest wave of global migration the world has seen.

In March, Jorge and his 7-year-old son each packed a pair of pants, three T-shirts, underwear and a toothbrush into a single thin black nylon sack with a drawstring. Jorge’s father had pawned his last four goats for $2,000 to help pay for their transit, another loan the family would have to repay at 100% interest. The coyote called at 10 p.m. — they would go that night. They had no idea then where they would wind up, or what they would do when they got there.

From decision to departure, it was three days. And then they were gone.

For most of human history, people have lived within a surprisingly narrow range of temperatures, in the places where the climate supported abundant food production. But as the planet warms, that band is suddenly shifting north. According to a pathbreaking recent study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the planet could see a greater temperature increase in the next 50 years than it did in the last 6,000 years combined. By 2070, the kind of extremely hot zones, like in the Sahara, that now cover less than 1% of the earth’s land surface could cover nearly a fifth of the land, potentially placing 1 of every 3 people alive outside the climate niche where humans have thrived for thousands of years. Many will dig in, suffering through heat, hunger and political chaos, but others will be forced to move on. A 2017 study in Science Advances found that by 2100, temperatures could rise to the point that just going outside for a few hours in some places, including parts of India and Eastern China, “will result in death even for the fittest of humans.”

People are already beginning to flee. In Southeast Asia, where increasingly unpredictable monsoon rainfall and drought have made farming more difficult, the World Bank points to more than 8 million people who have moved toward the Middle East, Europe and North America. In the African Sahel, millions of rural people have been streaming toward the coasts and the cities amid drought and widespread crop failures. Should the flight away from hot climates reach the scale that current research suggests is likely, it will amount to a vast remapping of the world’s populations.

Migration can bring great opportunity not just to migrants but also to the places they go. As the United States and other parts of the global North face a demographic decline, for instance, an injection of new people into an aging workforce could be to everyone’s benefit. But securing these benefits starts with a choice: Northern nations can relieve pressures on the fastest-warming countries by allowing more migrants to move north across their borders, or they can seal themselves off, trapping hundreds of millions of people in places that are increasingly unlivable. The best outcome requires not only goodwill and the careful management of turbulent political forces; without preparation and planning, the sweeping scale of change could prove wildly destabilizing. The United Nations and others warn that in the worst case, the governments of the nations most affected by climate change could topple as whole regions devolve into war.

The stark policy choices are already becoming apparent. As refugees stream out of the Middle East and North Africa into Europe and from Central America into the United States, an anti-immigrant backlash has propelled nationalist governments into power around the world. The alternative, driven by a better understanding of how and when people will move, is governments that are actively preparing, both materially and politically, for the greater changes to come.

Last summer, I went to Central America to learn how people like Jorge will respond to changes in their climates. I followed the decisions of people in rural Guatemala and their routes to the region’s biggest cities, then north through Mexico to Texas. I found an astonishing need for food and witnessed the ways competition and poverty among the displaced broke down cultural and moral boundaries. But the picture on the ground is scattered. To better understand the forces and scale of climate migration over a broader area, The New York Times Magazine and ProPublica joined with the Pulitzer Center in an effort to model, for the first time, how people will move across borders.

We focused on changes in Central America and used climate and economic-development data to examine a range of scenarios. Our model projects that migration will rise every year regardless of climate, but that the amount of migration increases substantially as the climate changes. In the most extreme climate scenarios, more than 30 million migrants would head toward the U.S. border over the course of the next 30 years.

Migrants move for many reasons, of course. The model helps us see which migrants are driven primarily by climate, finding that they would make up as much as 5% of the total. If governments take modest action to reduce climate emissions, about 680,000 climate migrants might move from Central America and Mexico to the United States between now and 2050. If emissions continue unabated, leading to more extreme warming, that number jumps to more than a million people. (None of these figures include undocumented immigrants, whose numbers could be twice as high.)

The model shows that the political responses to both climate change and migration can lead to drastically different futures.

As with much modeling work, the point here is not to provide concrete numerical predictions so much as it is to provide glimpses into possible futures. Human movement is notoriously hard to model, and as many climate researchers have noted, it is important not to add a false precision to the political battles that inevitably surround any discussion of migration. But our model offers something far more potentially valuable to policymakers: a detailed look at the staggering human suffering that will be inflicted if countries shut their doors.

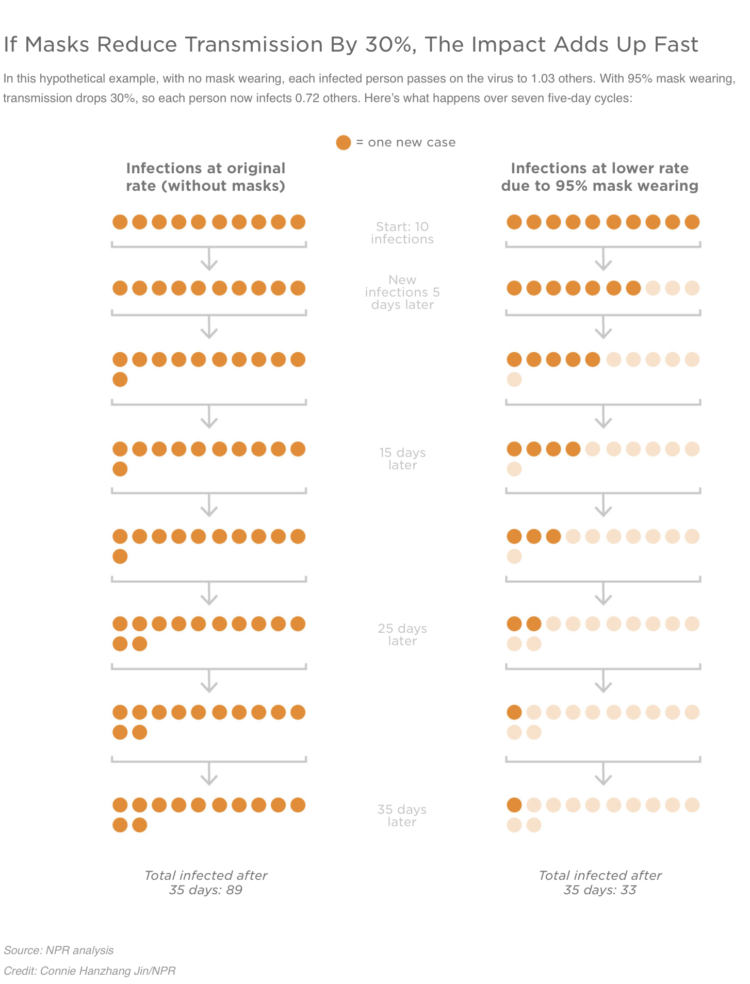

In recent months, the coronavirus pandemic has offered a test run on whether humanity has the capacity to avert a predictable — and predicted — catastrophe. Some countries have fared better. But the United States has failed. The climate crisis will test the developed world again, on a larger scale, with higher stakes. The only way to mitigate the most destabilizing aspects of mass migration is to prepare for it, and preparation demands a sharper imagining of where people are likely to go, and when.

I. A Different Kind of Climate Model

In November 2007, Alan B. Krueger, a labor economist known for his statistical work on inequality, walked into the Princeton University offices of Michael Oppenheimer, a leading climate geoscientist, and asked him whether anyone had ever tried to quantify how and where climate change would cause people to move.

Earlier that year, Oppenheimer helped write the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report that, for the first time, explored in depth how climate disruption might uproot large segments of the global population. But as groundbreaking as the report was — the U.N. was recognized for its work with a Nobel Peace Prize — the academic disciplines whose work it synthesized were largely siloed from one another. Demographers, agronomists and economists were all doing their work on climate change in isolation, but understanding the question of migration would have to include all of them.

Together, Oppenheimer and Krueger, who died in 2019, began to chip away at the question, asking whether tools typically used by economists might yield insight into the environment’s effects on people’s decision to migrate. They began to examine the statistical relationships — say, between census data and crop yields and historical weather patterns — in Mexico to try to understand how farmers there respond to drought. The data helped them create a mathematical measure of farmers’ sensitivity to environmental change — a factor that Krueger could use the same way he might evaluate fiscal policies, but to model future migration.

Their study, published in 2010 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that Mexican migration to the United States pulsed upward during periods of drought and projected that by 2080, climate change there could drive 6.7 million more people toward the southern U.S. border. “It was,” Oppenheimer said, “one of the first applications of econometric modeling to the climate-migration problem.”

The modeling was a start. But it was hyperlocal instead of global, and it left open huge questions: how cultural differences might change outcomes, for example, or how population shifts might occur across larger regions. It was also controversial, igniting a backlash among climate-change skeptics, who attacked the modeling effort as “guesswork” built on “tenuous assumptions” and argued that a model couldn’t untangle the effect of climate change from all the other complex influences that determine human decision-making and migration. That argument eventually found some traction with migration researchers, many of whom remain reluctant to model precise migration figures.

But to Oppenheimer and Krueger, the risks of putting a specific shape to this well established but amorphous threat seemed worth taking. In the early 1970s, after all, many researchers had made a similar argument against using computer models to forecast climate change, arguing that scientists shouldn’t traffic in predictions. Others ignored that advice, producing some of the earliest projections about the dire impact of climate change, and with them some of the earliest opportunities to try to steer away from that fate. Trying to project the consequences of climate-driven migration, to Oppenheimer, called for similarly provocative efforts. “If others have better ideas for estimating how climate change affects migration,” he wrote in 2010, “they should publish them.”

Since then, Oppenheimer’s approach has become common. Dozens more studies have applied econometric modeling to climate-related problems, seizing on troves of data to better understand how environmental change and conflict each lead to migration and clarify how the cycle works. Climate is rarely the main cause of migration, the studies have generally found, but it is almost always an exacerbating one.

As they have looked more closely, migration researchers have found climate’s subtle fingerprints almost everywhere. Drought helped push many Syrians into cities before the war, worsening tensions and leading to rising discontent; crop losses led to unemployment that stoked Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt and Libya; Brexit, even, was arguably a ripple effect of the influx of migrants brought to Europe by the wars that followed. And all those effects were bound up with the movement of just 2 million people. As the mechanisms of climate migration have come into sharper focus — food scarcity, water scarcity and heat — the latent potential for large-scale movement comes to seem astronomically larger.

North Africa’s Sahel provides an example. In the nine countries stretching across the continent from Mauritania to Sudan, extraordinary population growth and steep environmental decline are on a collision course. Past droughts, most likely caused by climate change, have already killed more than 100,000 people there. And the region — with more than 150 million people and growing — is threatened by rapid desertification, even more severe water shortages and deforestation. Today researchers at the United Nations estimate that some 65% of farmable lands have already been degraded. “My deep fear,” said Solomon Hsiang, a climate researcher and economist at the University of California, Berkeley, is that Africa’s transition into a post-climate-change civilization “leads to a constant outpouring of people.”

The story is similar in South Asia, where nearly one-fourth of the global population lives. The World Bank projects that the region will soon have the highest prevalence of food insecurity in the world. While some 8.5 million people have fled already — resettling mostly in the Persian Gulf — 17 million to 36 million more people may soon be uprooted, the World Bank found. If past patterns are a measure, many will settle in India’s Ganges Valley; by the end of the century, heat waves and humidity will become so extreme there that people without air conditioning will simply die.

If it is not drought and crop failures that force large numbers of people to flee, it will be the rising seas. We are now learning that climate scientists have been underestimating the future displacement from rising tides by a factor of three, with the likely toll being some 150 million globally. New projections show high tides subsuming much of Vietnam by 2050 — including most of the Mekong Delta, now home to 18 million people — as well as parts of China and Thailand, most of southern Iraq and nearly all of the Nile Delta, Egypt’s breadbasket. Many coastal regions of the United States are also at risk.

Through all the research, rough predictions have emerged about the scale of total global climate migration — they range from 50 million to 300 million people displaced — but the global data is limited, and uncertainty remained about how to apply patterns of behavior to specific people in specific places. Now, though, new research on both fronts has created an opportunity to improve the models tremendously. A few years ago, climate geographers from Columbia University and the City University of New York began working with the World Bank to build a next-generation tool to establish plausible migration scenarios for the future. The idea was to build on the Oppenheimer-style measure of response to the environment with other methods of analysis, including a “gravity” model, which assesses the relative attractiveness of destinations with the hope of mathematically anticipating where migrants might end up. The resulting report, published in early 2018, involved six European and American institutions and took nearly two years to complete.

The bank’s work targeted climate hot spots in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America, focusing not on the emergency displacement of people from natural disasters but on their premeditated responses to what researchers call “slow-onset” shifts in the environment. They determined that as climate change progressed in just these three regions alone, as many as 143 million people would be displaced within their own borders, moving mostly from rural areas to nearby towns and cities. The study, though, wasn’t fine-tuned to specific climatic changes like declining groundwater. And it didn’t even try to address the elephant in the room: How would the climate push people to migrate across international borders?

In early 2019, The Times Magazine and ProPublica, with support from the Pulitzer Center, hired an author of the World Bank report — Bryan Jones, a geographer at Baruch College — to add layers of environmental data to its model, making it even more sensitive to climatic change and expanding its reach. Our goal was to pick up where the World Bank researchers left off, in order to model, for the first time, how people would move between countries, especially from Central America and Mexico toward the United States.

First we gathered existing datasets — on political stability, agricultural productivity, food stress, water availability, social connections, weather and much more — in order to approximate the kaleidoscopic complexity of human decision-making.

Then we started asking questions: If crop yields continue to decline because of drought, for instance, and people are forced to respond by moving, as they have in the past, can we see where they will go and see what new conditions that might introduce? It’s very difficult to model how individual people think or to answer these questions using individual data points — often the data simply doesn’t exist. Instead of guessing what Jorge A. will do and then multiplying that decision by the number of people in similar circumstances, the model looks across entire populations, averaging out trends in community decision-making based on established patterns, then seeing how those trends play out in different scenarios.

In all, we fed more than 10 billion data points into our model. Then we tested the relationships in the model retroactively, checking where historical cause and effect could be empirically supported, to see if the model’s projections about the past matches what really happened. Once the model was built and layered with both approaches — econometric and gravity — we looked at how people moved as global carbon concentrations increased in five different scenarios, which imagine various combinations of growth, trade and border control, among other factors. (These scenarios have become standard among climate scientists and economists in modeling different pathways of global socioeconomic development.)

Only a supercomputer could efficiently process the work in its entirety; estimating migration from Central America and Mexico in one case required uploading our query to a federal mainframe housed in a building the size of a small college campus outside Cheyenne, Wyoming, run by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, where even there it took four days for the machine to calculate its answers. (A more detailed description of the data project can be found at propublica.org/migration-methodology.)

The results are built around a number of assumptions about the relationships between real-world developments that haven’t all been scientifically validated. The model also assumes that complex relationships — say, how drought and political stability relate to each other — remain consistent and linear over time (when in reality we know the relationships will change, but not how). Many people will also be trapped by their circumstances, too poor or vulnerable to move, and the models have a difficult time accounting for them.

All this means that our model is far from definitive. But every one of the scenarios it produces points to a future in which climate change, currently a subtle disrupting influence, becomes a source of major disruption, increasingly driving the displacement of vast populations.

II. How Climate Moves People

Delmira de Jesús Cortez Barrera moved to the outskirts of San Salvador six years ago, after her life in the rural western edge of El Salvador — just 90 miles from Jorge A.’s village in Guatemala — collapsed. Now she sells pupusas on a block not far from where teenagers stand guard for the Mara Salvatrucha gang. When we met last summer, she was working six days a week, earning $7 a day, or less than $200 a month. She relied on the kindness of her boss, who gave her some free meals at work. But everything else for her and her infant son she had to provide herself. Cortez commuted before dawn from San Marcos, where she lived with her sister in a cheap room off a pedestrian alleyway. But her apartment still cost $65 each month. And she sent $75 home to her parents each month — enough for beans and cheese to feed the two daughters she left with them. “We’re going backward,” she said.

Her story — that of an uneducated, unskilled woman from farm roots who can’t find high-paying work in the city and falls deeper into poverty — is a familiar one, the classic pattern of in-country migration all around the world. San Salvador, meanwhile, has become notorious as one of the most dangerous cities in the world, a capital in which gangs have long controlled everything from the majestic colonial streets of its downtown squares to the offices of the politicians who reside in them. It is against this backdrop of war, violence, hurricanes and poverty that 1 in 6 of El Salvador’s citizens have fled for the United States over the course of the last few decades, with some 90,000 Salvadorans apprehended at the U.S. border in 2019 alone.

Cortez was born about a mile from the Guatemalan border, in El Paste, a small town nestled on the side of a volcano. Her family were jornaleros — day laborers who farmed on the big maize and bean plantations in the area — and they rented a two-room mud-walled hut with a dirt floor, raising nine children there. Around 2012, a coffee blight worsened by climate change virtually wiped out El Salvador’s crop, slashing harvests by 70%. Then drought and unpredictable storms led to what a U.N.-affiliated food-security organization describes as “a progressive deterioration” of Salvadorans’ livelihoods.

That’s when Cortez decided to leave. She married and found work as a brick maker at a factory in the nearby city of Ahuachapán. But the gangs found easy prey in vulnerable farmers and spread into the Salvadoran countryside and the outlying cities, where they made a living by extorting local shopkeepers. Here we can see how climate change can act as what Defense Department officials sometimes refer to as a “threat multiplier.” For Cortez, the threat could not have been more dire. After two years in Ahuachapán, a gang-connected hit man knocked on Cortez’s door and took her husband, whose ex-girlfriend was a gang member, executing him in broad daylight a block away.

In other times, Cortez might have gone back home. But there was no work in El Paste, and no water. So she sent her children there and went to San Salvador instead.

For all the ways in which human migration is hard to predict, one trend is clear: Around the world, as people run short of food and abandon farms, they gravitate toward cities, which quickly grow overcrowded. It’s in these cities, where waves of new people stretch infrastructure, resources and services to their limits, that migration researchers warn that the most severe strains on society will unfold. Food has to be imported — stretching reliance on already-struggling farms and increasing its cost. People will congregate in slums, with little water or electricity, where they are more vulnerable to flooding or other disasters. The slums fuel extremism and chaos.

It is a shift that is already well underway, which is why the World Bank has raised concerns about the mind-boggling influx of people into East African cities like Addis Ababa, in Ethiopia, where the population has doubled since 2000 and is expected to nearly double again by 2035. In Mexico, the World Bank estimates, as many as 1.7 million people may migrate away from the hottest and driest regions, many of them winding up in Mexico City.

But like so much of the rest of the climate story, the urbanization trend is also just the beginning. Right now a little more than half of the planet’s population lives in urban areas, but by the middle of the century, the World Bank estimates, 67% will. In just a decade, 4 out of every 10 urban residents — 2 billion people around the world — will live in slums. The International Committee of the Red Cross warns that 96% of future urban growth will happen in some of the world’s most fragile cities, which already face a heightened risk of conflict and have governments that are least capable of dealing with it. Some cities will be unable to sustain the influx. In the case of Addis Ababa, the World Bank suggests that in the second half of the century, many of the people who fled there will be forced to move again, leaving that city as local agriculture around it dries up.

Our modeling effort is premised on the notion that in these cities as they exist now, we can see the seeds of their future growth. Relationships between quality-of-life factors like household income in specific neighborhoods, education levels, employment rates and so forth — and how each of those changed in response to climate — would reveal patterns that could be projected into the future. As moisture raises the grain in a slab of wood, the information just needed to be elicited.

Under every scientific forecast for global climate change, El Salvador gets hotter and drier, and our model was in accord with what other researchers said was likely: San Salvador will continue to grow as a result, putting still more people in its dense outer rings. What happens in its farm country, though, is more dependent on which climate and development policies governments to the north choose to deploy in dealing with the warming planet. High emissions, with few global policy changes and relatively open borders, will drive rural El Salvador — just like rural Guatemala — to empty out, even as its cities grow.

Should the United States and other wealthy countries change the trajectory of global policy, though — by, say, investing in climate mitigation efforts at home but also hardening their borders — they would trigger a complex cascade of repercussions farther south, according to the model. Central American and Mexican cities continue to grow, albeit less quickly, but their overall wealth and development slows drastically, most likely concentrating poverty further. Far more people also remain in the countryside for lack of opportunity, becoming trapped and more desperate than ever.

People move to cities because they can seem like a refuge, offering the facade of order — tall buildings and government presence — and the mirage of wealth. I met several men who left their farm fields seeking extremely dangerous work as security guards in San Salvador and Guatemala City. I met a 10-year-old boy washing car windows at a stoplight, convinced that the coins in his jar would help buy back his parents’ farmland. Cities offer choices and a sense that you can control your destiny.

These same cities, though, can just as easily become traps, as the challenges that go along with rapid urbanization quickly pile up. Since 2000, San Salvador’s population has ballooned by more than a third as it has absorbed migrants from the rural areas, even as tens of thousands of people continue to leave the country and migrate north. By midcentury, the U.N. estimates that El Salvador — which has 6.4 million people and is the most densely populated country in Central America — will be 86% urban.

Our models show that much of the growth will be concentrated in the city’s slumlike suburbs, places like San Marcos, where people live in thousands of ramshackle structures, many without electricity or fresh water. In these places, even before the pandemic and its fallout, good jobs were difficult to find, poverty was deepening and crime was increasing. Domestic abuse has also been rising, and declining sanitary conditions threaten more disease. As society weakens, the gangs — whose members outnumber the police in parts of El Salvador by an estimated three to one — extort and recruit. They have made San Salvador’s murder rate one of the highest in the world.

Cortez hoped to escape the violence, but she couldn’t. The gangs run through her apartment block, stealing televisions and collecting protection payments. She had recently witnessed a murder inside a medical clinic where she was delivering food. The lack of security, the lack of affordable housing, the lack of child care, the lack of sustenance — all influence the evolution of complex urban systems under migratory pressure, and our model considers such stresses by incorporating data on crime, governance and health care. They are signposts for what is to come.

A week before our meeting last year, Cortez had resolved to make the trip to the United States at almost any cost. For months she had “felt like going far away,” but moving home was out of the question. “The climate has changed, and it has provoked us,” she said, adding that it had scarcely rained in three years. “My dad, last year, he just gave up.”

Cortez recounted what she did next. As her boss dropped potato pupusas into the smoking fryer, Cortez turned to her and made an unimaginable request: Would she take Cortez’s baby? It was the only way to save the child, Cortez said. She promised to send money from the United States, but the older woman said no — she couldn’t imagine being able to care for the infant.

Today San Salvador is shut down by the coronavirus pandemic, and Cortez is cooped up inside her apartment in San Marcos. She hasn’t worked in three months and is unable to see her daughters in El Paste. She was allowed a forbearance on rent during the country’s official lockdown, but that has come to an end. She remains convinced that the United States is her only salvation — border walls be damned. She’ll leave, she said, “the first chance I get.”

Most would-be migrants don’t want to move away from home. Instead, they’ll make incremental adjustments to minimize change, first moving to a larger town or a city. It’s only when those places fail them that they tend to cross borders, taking on ever riskier journeys, in what researchers call “stepwise migration.” Leaving a village for the city is hard enough, but crossing into a foreign land — vulnerable to both its politics and its own social turmoil — is an entirely different trial.

Seven miles from the Suchiate River, which marks Guatemala’s border with Mexico, sits Siglo XXI, one of Mexico’s largest immigration detention centers, a squat concrete compound with 30-foot walls, barred windows and a punishment cell. In early 2019, the 960-bed facility was largely empty, as Mexico welcomed passing migrants instead of detaining them. But by March, as the United States increased pressure to stop Central Americans from reaching its borders, Mexico had begun to detain migrants who crossed into its territory, packing almost 2,000 people inside this center near the city of Tapachula. Detainees slept on mattresses thrown down in the white-tiled hallways, waited in lines to use toilets overflowing with feces and crammed shoulder to shoulder for hours to get a meal of canned meat spooned onto a metal tray.

On April 25, imprisoned migrants stormed the stairway leading to a fortified security platform in the center’s main hall, overpowering the guards and then unlocking the main gates. More than 1,000 Guatemalans, Cubans, Salvadorans, Haitians and others streamed into the Tapachula night.

I arrived in Tapachula five weeks after the breakout to find a city cracking in the crucible of migration. Just months earlier, passing migrants on Mexico’s southern border were offered rides and tortas and medicine from a sympathetic Mexican public. Now migrant families were being hunted down in the countryside by armed national-guard units, as if they were enemy soldiers.

Mexico has not always welcomed migrants, but President Andrés Manuel López Obrador was trying to make his country a model for increasingly open borders. This idealistic effort was also pragmatic: It was meant to show the world an alternative to the belligerent wall-building xenophobia he saw gathering momentum in the United States. More open borders, combined with strategic foreign aid and help with human rights to keep Central American migrants from leaving their homes in the first place, would lead to a better outcome for all nations. “I want to tell them they can count on us,” López Obrador had declared, promising the migrants work permits and temporary jobs.

The architects of Mexico’s policies assumed that its citizens had the patience and the capacity to absorb — economically, environmentally and socially — such an influx of people. But they failed to anticipate how President Donald Trump would hold their economy hostage to press his own anti-immigrant crackdown, and they were caught off-guard by how the burdens brought by the immigration traffic weighed on Mexico’s own people.

In the six months after López Obrador took office in December 2018, some 420,000 people entered Mexico without documentation, according to Mexico’s National Migration Institute. Many floated across the Suchiate on boards tied atop large inner tubes, paying guides a couple of dollars for passage. In Ciudad Hidalgo, a border town outside Tapachula, migrants camped in the square and fought in the streets. In a late-night interview in his cinder-block office, under the glare of fluorescent lights, the town’s director of public security, Luis Martínez López, rattled off statistics about their impact: Armed robberies jumped 45%; murders increased 15%.

Whether the crimes were truly attributable to the migrants was a matter of significant debate, but the perception that they were fueled a rising impatience. That March, Martínez told me, a confrontation between a crowd of about 400 migrants and the local police turned rowdy, and the migrants tied up five officers in the center of town. No one was hurt, but the incident stoked locals’ concern that things were getting out of control. “We used to open doors for them like brothers and feed them,” said Martínez, who has since left his government job. “I was disappointed and angry.”

In Tapachula, a much larger city, tourism and commerce began to suffer. Whole families of migrants huddled in downtown doorways overnight, crowding sidewalks and sleeping on thin, oil-stained sheets of cardboard. Hotels — normally almost sold out in December — were less than 65% full as visitors stayed away, fearful of crime. Clinics ran short of medication. The impact came at a vulnerable moment: While many northern Mexican states enjoyed economic growth of 3% to 11% in 2018, Chiapas — its southernmost state — had a 3% drop in its gross domestic product. “They are overwhelmed,” said the Rev. César Cañaveral Pérez, who earned a Ph.D. in the theology of human mobility in Rome and now runs Tapachula’s largest Catholic migrant shelter.

Models can’t say much about the cultural strain that might result from a climate influx; there is no data on anger or prejudice. What they do say is that over the next two decades, if climate emissions continue as they are, the population in southern Mexico will grow sharply.

At the same time, Mexico has its own serious climate concerns and will most likely see its own climate exodus. One in 6 Mexicans now rely on farming for their livelihood, and close to half the population lives in poverty. Studies estimate that with climate change, water availability per capita could decrease by as much as 88% in places, and crop yields in coastal regions may drop by a third. If that change does indeed push out a wave of Mexican migrants, many of them will most likely come from Chiapas.

Yet a net increase in population at the same time — which is what our models assume — suggests that even as 1 million or so climate migrants make it to the U.S. border, many more Central Americans will become trapped in protracted transit, unable to move forward or backward in their journey, remaining in southern Mexico and making its current stresses far worse.

Already, by late last year, the Mexican government’s ill-planned policies had begun to unravel into something more insidious: rising resentment and hate. Now that the coronavirus pandemic has effectively sealed borders, those sentiments risk bubbling over. Migrants, with nowhere to go and no shelters able to take them in, roam the streets, unable to socially distance and lacking even basic sanitation.

It has angered many Mexican citizens, who have begun to describe the migrants as economic parasites and question foreign aid aimed at helping people cope with the drought in places where Jorge A. and Cortez come from.

“How dare AMLO give $30 million to El Salvador when we have no services here?” asked Javier Ovilla Estrada, a community-group leader in the southern border town Ciudad Hidalgo, referring to López Obrador’s participation in a multibillion-dollar development plan with Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Ovilla has become a strident defender of a new Mexico-first movement, organizing thousands to march against immigrants. Months before the coronavirus spread, we met in the sterile dining room of a Chinese restaurant that he frequents in Ciudad Hidalgo, and he echoed the same anti-immigrant sentiments rising in the U.S. and Europe.

The migrants “don’t love this country,” he said. He points to anti-immigrant Facebook groups spreading rumors that migrants stole ballots and rigged the Mexican presidential election, that they murder with impunity and run brothels. He’s not the first to tell me that the migrants traffic in disease — that Suchiate will soon be overwhelmed by Ebola. “They should close the borders once and for all,” he said. If they don’t, he warns, the country will sink further into lawlessness and conflict. “We’re going to go out into the streets to defend our homes and our families.”

One afternoon last summer, I sat on a black pleather couch in a borrowed airport-security office at the Tapachula airfield to talk with Francisco Garduño Yáñez, Mexico’s new commissioner for immigration. Garduño had abruptly succeeded a man named Tonatiuh Guillén López, a strong proponent of more open borders, whom I’d been trying to reach for weeks to ask how Mexico had strayed so far from the mission he laid out for it.

But in between, Trump had, as another senior government official told me, “held a gun to Mexico’s head,” demanding a crackdown at the Guatemalan border under threat of a 25% tariff on trade. Such a tax could break the back of Mexico’s economy overnight, and so López Obrador’s government immediately agreed to dispatch a new militarized force to the border. Guillén resigned as a result, four days before I hoped to meet him.

Garduño, a cheerful man with short graying hair, a broad smile and a ceaseless handshake, had been on the job for less than 36 hours. He had flown to Tapachula because another riot had broken out in one of the city’s smaller fortified detention centers, and a starving Haitian refugee was filmed by news crews there, begging for help for her and her young son. I wanted to know how it had come to this — from signing an international humanitarian migrant bill of rights to a mother lying with her face pressed to the ground in a detention center begging for food, in the space of a few months. He demurred, laying blame at the feet of neoliberal economics, which he said had produced a “poverty factory” with no regional development policies to address it. It was the system — capitalism itself — that had abandoned human beings, not Mexico’s leaders. “We didn’t anticipate that the globalization of the economy, the globalization of the law … would have such a devastating effect,” Garduño told me.

It seemed telling that Garduño’s previous role had been as Mexico’s commissioner of federal prisons. Was this the start of a new, punitive Mexico? I asked him. Absolutely not, he replied. But Mexico was now pursuing a policy of “containment,” he said, rejecting the notion that his country was obligated to “receive a global migration.”

No policy, though, would be able to stop the forces — climate, increasingly, among them — that are pushing migrants from the south to breach Mexico’s borders, legally or illegally. So what happens when still more people — many millions more — float across the Suchiate River and land in Chiapas? Our model suggests that this is what is coming — that between now and 2050, nearly 9 million migrants will head for Mexico’s southern border, more than 300,000 of them because of climate change alone.

Before leaving Mexico last summer, I went to Huixtla, a small town 25 miles west of Tapachula that, because it sat on the Bestia freight rail line used by migrants, had long been a waypoint on Mexico’s superhighway for Central Americans on their way north. Joining several local police officers as they headed out on patrol, I watched as our pickup truck’s red and blue lights reflected in the barred windows of squat cinder-block homes. Two officers stood in back, holding tight to the truck’s roll bars, black combat boots firmly planted in the cargo bed, as the driver, dodging mangy dogs, navigated the town’s slender alleyways.

The operations commander, a soft-spoken bureaucratic type named José Gozalo Rodríguez Méndez, sat in the front seat. I asked him if he thought Mexico could sustain the number of migrants who might soon come. He said Mexico would buckle. There is no money from the federal government, no staffing to address services, no housing, let alone shelter, no more goodwill. “We couldn’t do it.”

Rodríguez had already been tested. When the first caravan of thousands of migrants reached Huixtla in late 2018, throngs of tired, destitute people — many of them carrying children in their emaciated arms — packed the central square and spilled down the city’s side streets. Rodríguez and his wife went through their cupboards, gathering corn, fried beans and tortillas, and collected clothing outgrown by their children and hauled all of it to the town center, where church and civic groups had set up tents and bathrooms.

But as the caravans continued, he said, his goodwill began to disintegrate. “It’s like inviting somebody to your place for dinner,” he said. “You’ll invite them once, even twice. But will you invite them six times?” When the fourth caravan of migrants approached the city last March, Rodríguez told me, he stayed home.

In the center of town, the truck lurched to a stop amid a busy market, where stalls sell vegetables and toys under blue light filtered through plastic tarps overhead. A short way away, five men sheltered from the searing heat under the shade of a metal awning on the platform of a crumbling railway station, never repaired after Hurricane Stan 14 years earlier. Rodríguez peppered the group — two from Honduras, three from Guatemala — with questions. Together they said they had suffered the totality of misfortune that Central America offers: muggings, gang extortion and environmental disaster. Either they couldn’t grow food or the drought made it too expensive to buy.

“We can’t stand the hunger,” said one Honduran farmer, Jorge Reyes, his gaunt face dripping with sweat. At his feet was a gift from a shopkeeper: a plastic bag filled with a cut of raw meat, pooled in its own blood, flies circling around it in the heat. Reyes had nowhere to cook it. “If we are going to die anyway,” he said, “we might as well die trying to get to the United States.”

III. The Choice

Reyes had made his decision. Like Jorge A., Cortez and millions of others, he was going to the U.S. The next choice — how to respond and prepare for the migrants — ultimately falls to America’s elected leaders.

Over the course of 2019, El Paso, Texas, had endured a crush of people at its border crossings, peaking at more than 4,000 migrants in a single day, as the same caravans of Central Americans that had worn out their welcome in Tapachula made their way here. It put El Paso in a delicate spot, caught between the forces of politically charged anti-immigrant federal policy and its own deep roots as a diverse, largely Hispanic city whose identity was virtually inextricable from its close ties to Mexico. This surge, though, stretched the city’s capacity. When the migrants arrived, city officials argued over who should pay the tab for the emergency services, aid and housing, and in the end crossed their fingers and hoped the city’s active private charities would figure it out. Church groups rented thousands of hotel rooms across the city, delivered food, offered counseling and so on.

Conjoined to the Mexican city of Juárez, the El Paso area is the second-largest binational metroplex in the Western Hemisphere. It sits smack in the middle of the Chihuahuan Desert, a built-up oasis amid a barren and bleached-bright rocky landscape. Much of its daily workforce commutes across the border, and Spanish is as common as English.

Downtown, new buildings are rising in a weary business district where boot shops and pawnshops compete amid boarded-up and barred storefronts. The only barriers between the American streets — home to more than 800,000 people — and their Juárez counterparts are the concrete viaduct of a mostly dry Rio Grande and a rusted steel border fence.

To some migrants, this place is Eden. But El Paso is also a place with oppressive heat and very little water, another front line in the climate crisis. Temperatures already top 90 degrees here for three months of the year, and by the end of the century it will be that hot one of every two days. The heat, according to researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, will drive deaths that soon outpace those from car crashes or opioid overdoses. Cooling costs — already a third of some residents’ budgets — will get pricier, and warming will drive down economic output by 8%, perhaps making El Paso just as unlivable as the places farther south.

In 2014, El Paso created a new city government position — chief resilience officer — aimed, in part, at folding climate concerns into its urban planning. Soon enough, the climate crisis in Guatemala — not just the one in El Paso — became one of the city’s top concerns. “I apologize if I’m off topic,” the resilience chief, Nicole Ferrini, told municipal leaders and other attendees at a water conference in Phoenix in 2019 as she raised the question of “massive amounts of climate refugees, and are we prepared as a community, as a society, to deal with that?”

Ferrini, an El Paso native, did her academic training as an architect. She worries that El Paso will struggle to adapt if its leadership, and the nation’s, continue to react to daily or yearly spikes rather than view the problem as a systematic one, destined to become steadily worse as the planet warms. She sees her own city as an object lesson in what U.N. officials and climate-migration scientists have been warning of: Without a decent plan for housing, feeding and employing a growing number of climate refugees, cities on the receiving end of migration can never confidently pilot their own economic future.

For the moment, the coronavirus pandemic has largely choked off legal crossings into El Paso, but that crisis will eventually fade. And when it does, El Paso will face the same enduring choice that all wealthier societies everywhere will eventually face: determining whether it is a society of walls or — in the vernacular of aid organizations working to fortify infrastructure and resilience to stem migration — one that builds wells.

Around the world, nations are choosing walls. Even before the pandemic, Hungary fenced off its boundary with Serbia, part of more than 1,000 kilometers of border walls erected around the European Union states since 1990. India has built a fence along most of its 2,500-mile border with Bangladesh, whose people are among the most vulnerable in the world to sea-level rise.

The United States, of course, has its own wall-building agenda — literal ones, and the figurative ones that can have a greater effect. On a walk last August from one of El Paso’s migrant shelters, an inconspicuous brick home called Casa Vides, the Rev. Peter Hinde told me that El Paso’s security-oriented economy had created a cultural barrier that didn’t exist when he moved here 25 years earlier. Hinde, who is 97, helps run the Carmelite order in Juárez but was traveling to volunteer at Casa Vides on a near-daily basis. A former Army Air Forces captain and fighter pilot who grew up in Chicago, Hinde said the United States is turning its own fears into reality when it comes to immigration, something he witnesses in a growing distrust of everyone who crosses the border.

That fear creates other walls. The United States refused to join 164 other countries in signing a global migration treaty in 2018, the first such agreement to recognize climate as a cause of future displacement. At the same time, the U.S. is cutting off foreign aid — money for everything from water infrastructure to greenhouse agriculture — that has been proved to help starving families like Jorge A.’s in Guatemala produce food, and ultimately stay in their homes. Even those migrants who legally make their way into El Paso have been turned back, relegated to cramped and dangerous shelters in Juárez to wait for the hearings they are owed under law.

There is no more natural and fundamental adaptation to a changing climate than to migrate. It is the obvious progression the earliest Homo sapiens pursued out of Africa, and the same one the Mayans tried 1,200 years ago. As Lorenzo Guadagno at the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration told me recently, “Mobility is resilience.” Every policy choice that allows people the flexibility to decide for themselves where they live helps make them safer.

But it isn’t always so simple, and relocating across borders doesn’t have to be inevitable. I thought about Jorge A. from Guatemala. He made it to the United States last spring, climbing the steel border barrier and dropping his 7-year-old son 20 feet down the other side into the California desert. (We are abbreviating his last name in this article because of his undocumented status.) Now they live in Houston, where until the pandemic, Jorge found steady work in construction, earning enough to pay his debts and send some money home. But the separation from his wife and family has proved intolerable; home or away, he can’t win, and as of early July, he was wondering if he should go back to Guatemala.

And therein lies the basis for what may be the worst-case scenario: one in which America and the rest of the developed world refuse to welcome migrants but also fail to help them at home. As our model demonstrated, closing borders while stinting on development creates a somewhat counterintuitive population surge even as temperatures rise, trapping more and more people in places that are increasingly unsuited to human life.

In that scenario, the global trend toward building walls could have a profound and lethal effect. Researchers suggest that the annual death toll, globally, from heat alone will eventually rise by 1.5 million. But in this scenario, untold more will also die from starvation, or in the conflicts that arise over tensions that food and water insecurity will bring.

If this happens, the United States and Europe risk walling themselves in, as much as walling others out. And so the question then is: What are policymakers and planners prepared to do about that? America’s demographic decline suggests that more immigrants would play a productive role here, but the nation would have to be willing to invest in preparing for that influx of people so that the population growth alone doesn’t overwhelm the places they move to, deepening divisions and exacerbating inequalities. At the same time, the United States and other wealthy countries can help vulnerable people where they live, by funding development that modernizes agriculture and water infrastructure. A U.N. World Food Program effort to help farmers build irrigated greenhouses in El Salvador, for instance, has drastically reduced crop losses and improved farmers’ incomes. It can’t reverse climate change, but it can buy time.

Thus far, the United States has done very little at all. Even as the scientific consensus around climate change and climate migration builds, in some circles the topic has become taboo. This spring, after Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published the explosive study estimating that, barring migration, one-third of the planet’s population may eventually live outside the traditional ecological niche for civilization, Marten Scheffer, one of the study’s authors, told me that he was asked to tone down some of his conclusions through the peer-review process and that he felt pushed to “understate” the implications in order to get the research published. The result: Migration is only superficially explored in the paper. (A spokeswoman for the journal declined to comment because the review process is confidential.)

“There’s flat-out resistance,” Scheffer told me, acknowledging what he now sees as inevitable, that migration is going to be a part of the global climate crisis. “We have to face it.”

Our modeling and the consensus of academics point to the same bottom line: If societies respond aggressively to climate change and migration and increase their resilience to it, food production will be shored up, poverty reduced and international migration slowed — factors that could help the world remain more stable and more peaceful. If leaders take fewer actions against climate change, or more punitive ones against migrants, food insecurity will deepen, as will poverty. Populations will surge, and cross-border movement will be restricted, leading to greater suffering. Whatever actions governments take next — and when they do it — makes a difference.

The window for action is closing. The world can now expect that with every degree of temperature increase, roughly a billion people will be pushed outside the zone in which humans have lived for thousands of years. For a long time, the climate alarm has been sounded in terms of its economic toll, but now it can increasingly be counted in people harmed. The worst danger, Hinde warned on our walk, is believing that something so frail and ephemeral as a wall can ever be an effective shield against the tide of history. “If we don’t develop a different attitude,” he said, “we’re going to be like people in the lifeboat, beating on those that are trying to climb in.”

Pichu

Pichu Cleffa

Cleffa Igglybuff

Igglybuff Togepi

Togepi Azurill

Azurill Buneary

Buneary Munchlax

Munchlax Woobat

Woobat Happiny

Happiny Eevee

Eevee Budew

Budew Riolu

Riolu Chingling

Chingling Zigzagoon (Galarian)

Zigzagoon (Galarian) Meowth (Galarian)

Meowth (Galarian) Darumaka (Galarian)

Darumaka (Galarian) Farfetch’d (Galarian)

Farfetch’d (Galarian) Stunfisk (Galarian)

Stunfisk (Galarian)

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks during a campaign event on July 21, 2020, in New Castle, Delaware. | Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks during a campaign event on July 21, 2020, in New Castle, Delaware. | Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Catrina Rugar, 34, a traveling nurse from Florida, treats Covid-19 patients at Doctors Hospital at Renaissance in Edinburg, Texas. The coronavirus is spreading rapidly through the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. | Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Catrina Rugar, 34, a traveling nurse from Florida, treats Covid-19 patients at Doctors Hospital at Renaissance in Edinburg, Texas. The coronavirus is spreading rapidly through the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. | Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20304367/second_wave_hospital_chart_7_23_update.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox

The Chinese flag flies at the Chinese consulate in Houston on July 22, 2020. | Mark Felix/AFP via Getty Images

The Chinese flag flies at the Chinese consulate in Houston on July 22, 2020. | Mark Felix/AFP via Getty Images

President Donald Trump talks to reporters while hosting Republican congressional leaders and members of his cabinet in the Oval Office on July 20 in Washington, DC. | Doug Mills-Pool/Getty Images

President Donald Trump talks to reporters while hosting Republican congressional leaders and members of his cabinet in the Oval Office on July 20 in Washington, DC. | Doug Mills-Pool/Getty Images

President George W. Bush signs the Help America Vote Act on Oct. 29, 2002, creating the Election Assistance Commission.

William Philpott/Reuters

President George W. Bush signs the Help America Vote Act on Oct. 29, 2002, creating the Election Assistance Commission.

William Philpott/Reuters

Top: Jean Carnahan announces she will accept appointment to the Senate if her late husband wins. Bottom: John Ashcroft concedes after losing to Carnahan.

Bill Greenblatt/Liaison

Top: Jean Carnahan announces she will accept appointment to the Senate if her late husband wins. Bottom: John Ashcroft concedes after losing to Carnahan.

Bill Greenblatt/Liaison

Christy McCormick, then chair of the EAC, testifies at a hearing about election security on Capitol Hill on May 22, 2019.

Carolyn Kaster/AP Photo

Christy McCormick, then chair of the EAC, testifies at a hearing about election security on Capitol Hill on May 22, 2019.

Carolyn Kaster/AP Photo

Ben Hovland, then vice chair of the EAC, speaks before the House Judiciary Committee about the agency’s role in election oversight on Oct. 22, 2019.

Susan Walsh/AP Photo

Ben Hovland, then vice chair of the EAC, speaks before the House Judiciary Committee about the agency’s role in election oversight on Oct. 22, 2019.

Susan Walsh/AP Photo

In 2018, Georgia’s decades-old voting machines failed to record thousands of votes. The EAC has long delayed issuing new standards that could update machines.

Jessica McGowan/Getty Images

In 2018, Georgia’s decades-old voting machines failed to record thousands of votes. The EAC has long delayed issuing new standards that could update machines.

Jessica McGowan/Getty Images