We believe plans are the best way to achieve success and we compulsively gravitate toward them because they make us feel safe. Read more

Shared posts

8 Reasons Why I Stopped Making Plans

JessSkeptical. I mean, she basically says "I just figure out what I want to do, think about it, and then do it" which is kind of planning. I did read an article a while ago on 99u.com, which is all productivity and creativity tips & BS, about how I think it's Jeff Bezos refuses to schedule anything. ANYTHING. He doesn't have a calendar. If you want to meet with him, show up when you want to meet with him and if he has time, lucky you! If not, try again later! It only works because he's Jeff Bezos and no one has the money to tell him he's being an entitled jerk who doesn't consider other people's needs ahead of his own need for "freedom." I mean, of course no one wants to schedule meetings or accommodate other people or make plans. Of course not! And also I am the Queen of not making life plans and it backfires on you a lot in the form of regrets (I've had a few...but I did it myyyyy waaaayyyyyy). Okay, sorry.

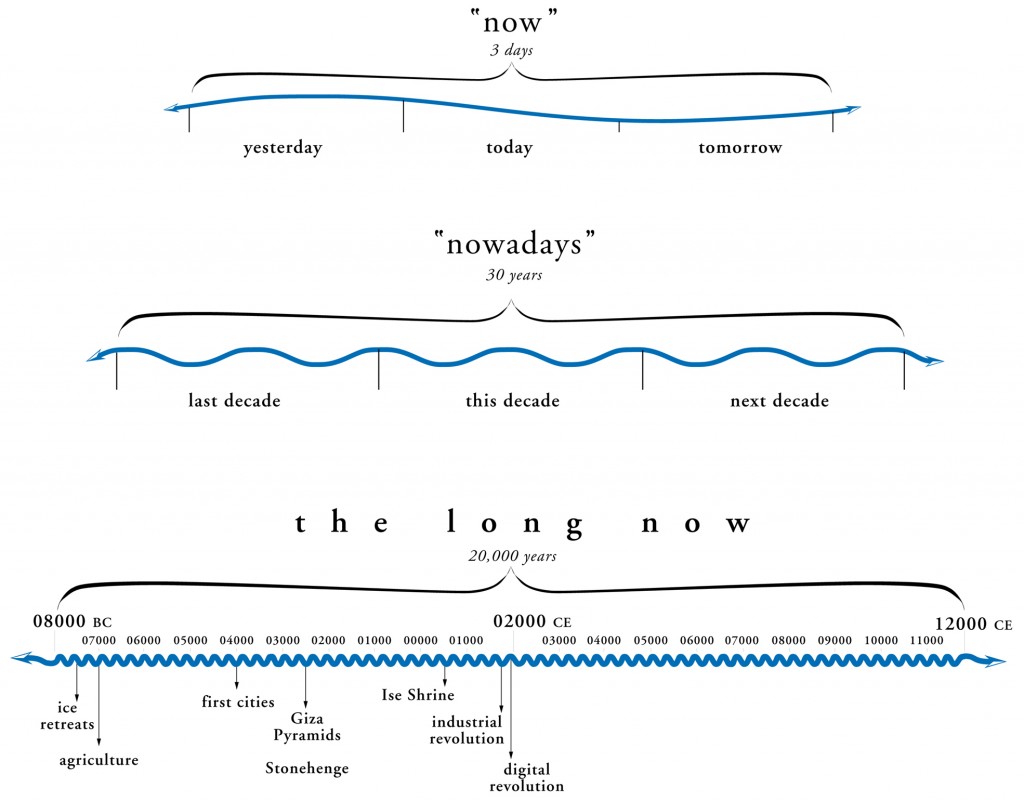

The Long Now Foundation

JessI always notice that when people talk about "long term" goals, they're only really thinking 5 years into the future. Not to get real dark here, but maybe, like animals who bolt before an earthquake, we have an innate sense that our time is running out? Or maybe we just conceptualized "the 2000s" as "the future" for so long that we can't imagine a different one, culturally? Anyway, I like this clock idea.

The Long Now Foundation hopes to provide a counterpoint to today’s accelerating culture and help make long-term thinking more common. They hope to creatively foster responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years:

“Civilization is revving itself into a pathologically short attention span. The trend might be coming from the acceleration of technology, the short-horizon perspective of market-driven economics, the next-election perspective of democracies, or the distractions of personal multi-tasking. All are on the increase. Some sort of balancing corrective to the short-sightedness is needed-some mechanism or myth which encourages the long view and the taking of long-term responsibility, where ‘long-term’ is measured at least in centuries. Long Now proposes both a mechanism and a myth. It began with an observation and idea by computer scientist Daniel Hillis :

“When I was a child, people used to talk about what would happen by the year 02000. For the next thirty years they kept talking about what would happen by the year 02000, and now no one mentions a future date at all. The future has been shrinking by one year per year for my entire life. I think it is time for us to start a long-term project that gets people thinking past the mental barrier of an ever-shortening future. I would like to propose a large (think Stonehenge) mechanical clock, powered by seasonal temperature changes. It ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium.”

Such a clock, if sufficiently impressive and well-engineered, would embody deep time for people. It should be charismatic to visit, interesting to think about, and famous enough to become iconic in the public discourse. Ideally, it would do for thinking about time what the photographs of Earth from space have done for thinking about the environment. Such icons reframe the way people think.”

More at The Long Now Foundation, which was established in 1996 (like, just now)

Related: The Full Moon Theatre, Temporocentrism, The Age of Speed.

The Overview Effect

Jessfor perspective

The Daily Overview offers up an interesting satellite photo every day. The site's name is inspired by the Overview Effect:

The Overview Effect, first described by author Frank White in 1987, is an experience that transforms astronauts' perspective of Earth and mankind's place upon it. Common features of the experience are a feeling of awe for the planet, a profound understanding of the interconnection of all life, and a renewed sense of responsibility for taking care of the environment. 'Overview' is a short film that explores this phenomenon through interviews with five astronauts who have experienced the Overview Effect. The film also features important commentary on the wider implications of this new understanding for both our society, and our relationship to the environment.

The Planetary Collective made a short documentary about the Overview Effect:

(thx, pavel)

Tags: Google Maps photography videoHark, a Vagrant: Ida B Wells

JessIda!

buy this print!

Ida! If she's not your hero, she should be. She's mine.

I gave an interview for the Appendix Journal, and cited her as a figure I'd like to make a comic about, but found it a hard thing, so that it never happened. The reason is easy - if you read about the things Ida Wells fought against, you won't laugh. You'll cry, I guarantee. And I thought, well I can't touch that woman with my dumb internet jokes, she's serious business. And she is.

But then, people use my comics as a launching device to learn history, and I would hope that part of what I do is to celebrate history, not just poke fun at the easy targets.

Anyway, I first saw a picture of Ida B. Wells at the Chicago History Museum. She was protesting the lack of African American representation at the Chicago World's Fair. And I am not sure what it was, but the image stuck with me. You could feel a power in the presence of the lady with the pamphlets. I found out later that she was also handing out information on the terrible truths of lynching in America, a crusade that she is best known for, and rightly so. Her writing on the topic is readily available on the internet, and if you read it, well you'll spend a good deal of time wondering at the terribleness of humanity, but you'll also note that she knew how to handle a volatile topic like that with an audience who didn't want to hear it. But, Ida fought against injustice wherever she saw it. You'll be happy to know, that at the 1913 Suffragist Parade in Washington, she was told to go to the back, but joined in the middle anyway.

I'll leave you with this, a review of Paula J. Giddings' Ida: A Sword Among Lions, from the Washington Post. Go forth, marvel at this woman, who was the best. Did I mention she was one of the first women in the country to keep her name when she married? A founding member of the NAACP? Ida! Just pioneer everything.

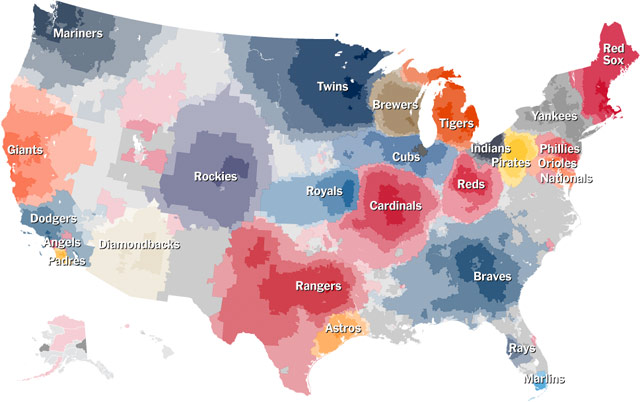

Baseball fandom map of the United States

JessWHY THE CUBS?

From the NY Times' new site, The Upshot, a bunch of maps showing the borders of baseball team fandom, with close-ups of various dividing lines: the Munson-Nixon Line, The Molitor Line, The Reagan-Nixon Line, and the Morgan-Ripken Line.

The NYC and Bay Area maps are so sad...the Mets and A's get no love. (via @atotalmonet)

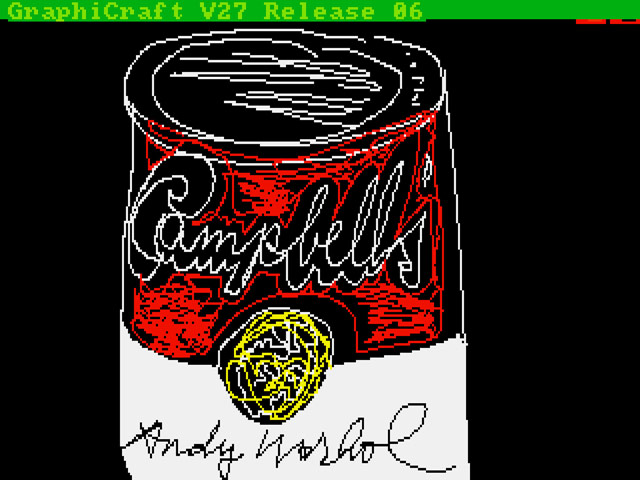

Tags: baseball maps sports USAWarhol's Amiga art

Jess"retrocomputing"!

In the 1980s, when personal computers with graphics capabilities were first introduced, Andy Warhol was an enthusiastic early adopter. In 1985, Commodore commissioned the artist to produce some art on their Amiga computer, but the work was never widely shown and was assumed lost. Then artist and retro computer nerd Cory Arcangel learned of Warhol's Amiga experiments from this video (and perhaps this article from a 1986 issue of Amigaworld) and set in motion the process of finding out if any of the computers or storage devices in The Andy Warhol Museum contained his Amiga art.

CMU Computer Club members determined that even reading the data from the diskettes entailed significant risk to the contents, and would require unusual tools and methodologies. By February 2013, in collaboration with collections manager Amber Morgan and other AWM personnel, the Club had completed a plan for handling the delicate disk media, and gathered at The Andy Warhol Museum to see if any data could be extracted. The Computer Club set up a cart of exotic gear, while a video crew from the Hillman Photography Initiative, under the direction of Kukielski, followed their progress.

It was not known in advance whether any of Warhol's imagery existed on the floppy disks-nearly all of which were system and application diskettes onto which, the team later discovered, Warhol had saved his own data. Reviewing the disks' directory listings, the team's initial excitement on seeing promising filenames like "campbells.pic" and "marilyn1.pic" quickly turned to dismay, when it emerged that the files were stored in a completely unknown file format, unrecognized by any utility. Soon afterwards, however, the Club's forensics experts had reverse-engineered the unfamiliar format, unveiling 28 never-before-seen digital images that were judged to be in Warhol's style by the AWM's experts. At least eleven of these images featured Warhol's signature.

Incredible.

Tags: Andy Warhol art Cory ArcangelThe origins of the moonwalk

JessShared entirely due to gratuitous Tenenbaums reference.

We all know Michael Jackson invented the moonwalk on-stage during a performance of Billie Jean at the Motown 25th Anniversary show. What this video presupposes is, maybe he didn't?

What the video shows is that as early as the 1930s, performers such as Fred Astaire, Bill Bailey, Cab Calloway, and Sammy Davis Jr. were doing something like the moonwalk. Now, Jackson didn't get the move from any of these sources, not directly anyway. As Jackson's choreographer Jeffrey Daniel explains, he got the moves from The Electric Boogaloos street dance crew and, according to LaToya Jackson, instructed Michael Jackson.

Which is to say, the moonwalk is yet another example of multiple discovery, along with calculus, the discovery of oxygen, and the invention of the telephone. (via open culture)

Tags: dance Jeffrey Daniel Michael Jackson Old Custer videoSmall Atoms

JessAh, mortality!

“Don’t look at me,” she said. “I’m just an idea woman.”

Three purple balloons floated in the winter air. They sometimes bumped into each other and said excuse me like they didn’t mean it. One of them named Pete was looking forward to the hour in which enough helium would leak out that he would drift down to the pavement. He felt stranded in the air like a water skier pulled behind a cruise liner. He loved the ground even though he had never been there.

Where he was made, from the moment he could remember, just flashes of stretching or color, he knew there was a ground and it was mysterious. He went from machine to bag to hand to spigot to air. Never a moment where someone slipped or the wind gusted and took his flaccid body to the ground. But the ground was inevitable, he knew, and it was exciting in a kind of secret devilish way. Like he shouldn’t find it so mysterious or ever wish to go there. He wasn’t anything like Dot or William, who were from the same factory and acted like it.

Watch out, Dot often said to William.

You watch out, William said.

I am watching out, Dot said.

~*~

Pete leaned away from them, into the breeze. His string was taunt but ultimately tied together with Dot and William’s to a wrought-iron bench in front of a candy store. He wondered if he had a death wish but thought if he had a death wish he would feel sad or tired or like everything should just go away. Really he felt curious and sometimes tickled by things he saw. Deflation wasn’t death anyway, he figured. It was probably more like the end of one thing and the start of another. He wasn’t like William who was petrified of deflating. William didn’t even like to talk about it. Dot was tougher to figure out. She seemed to think several things that didn’t all agree, but that also seemed to shed light on some other truth for her that she never talked about.

~*~

William raged and flung himself into the wind. He missed Dot and slammed against Pete. The three of them bobbed against each other for a while. Pete wasn’t above bickering. He just didn’t like to.

It might rain, Dot said a little later.

They all hoped it would before they deflated. Something else to have experienced or done. Try to catch as many drops as possible. Try to dodge them. Feel the droplets roll down and drip off to the sidewalk. Try to drink them without a mouth.

~*~

The wind was from the lake on the edge of the city. Pete was manufactured in one of the factories along the lake but on the other side, in Michigan. Sometimes he fantasized about somehow ending up back in the same factory. He liked to wonder and wondered if William wondered. Or Dot. She probably did, he thought.

You know what you need? An adventure, Dot said while William bull-rushed the sky.

If you could get someone to cut your string, that would do it, she said.

How do I do that? Pete said.

Don’t look at me, she said. I’m just an idea woman.

It would be great to see a river or mountains or just the city from high up, Pete thought. The sun was setting behind a building down the street.

Why does everything go down, William said out of breath.

Then he said, I don’t feel so hot.

~*~

They were star-shaped balloons but didn’t have any concept of real stars. One time a man walked by with a spherical balloon and the three of them gawked until it was out of sight.

Air or helium, Dot said.

Air. Look at how sluggish he is, William said. He’ll probably deflate within the hour.

What’s an hour, Pete said.

Shut up, William said. Balloons didn’t all have the same understanding of things, which made them fight a lot but was ultimately good because it gave them things to talk about.

I’d like to stretch out, Dot said meaning on a bed or couch.

There was a tree not far from the iron bench, planted in the sidewalk to beautify the city. The balloons were afraid of the tree mostly because it was big and looked like a set of scary hands reaching in all directions. The hands looked sharp and of course the balloons were afraid of anything sharp. When the wind blew and they were not fixated on each other but instead on a fluttering piece of paper or plastic bag that would ultimately get caught in the branches, the balloons glanced up and froze seeing the tree before them as if it had sneaked up when they weren’t looking.

~*~

The sky faded from pink to night blue and somewhere in between was the purple of their bodies. Seeing their color in nature put them at ease as if it justified them. As if they looked at themselves, having floated up so high that they became permanent in the universe.

~*~

A car drove by with music playing on the inside. The passengers remarked that the balloons looked to be dancing. And though the balloons did know how to dance or do what they thought was dancing—sometimes one of them would sing while the other two bobbed around—they were not, however at this moment the car drove by, dancing.

The bricks that outlined the face of the building behind the balloons served no structural purpose. Pete would follow them around the edge of the outer walls and down to the ground like they were a path in some maze that had only one way to follow. The bricks ran across the top fascia, far above them. When he was bored or in a trance he liked to look at them.

They’re decorative, Dot said one time.

What’s decorative, Pete said.

It means they are just there, she said.

Beneath the row of second floor windows was a ledge. The ledge looked higher than it normally did. Pete tried to stretch up to see it from where he used to but he couldn’t stretch far enough. He thought something was wrong but really there wasn’t. He floated quietly a minute with that knowledge.

Is this it? Dot said when she noticed.

You’re still alive if that’s what you mean, William said.

When is the moment we won’t know anything anymore, Pete said.

You don’t get dumber, William said.

No he means when we’re all deflated or just mostly deflated, Dot said.

William looked at the ground, his rubber body bowing down.

William, Dot said. William couldn’t seem to lift himself back up. He was lower than the other two. Pete let the wind take him forward. He turned sharply so that he wrapped around William, his string able to prop them up. Dot pushed against them both.

The temperature was the lowest it would get before dawn. As they huddled they talked about anything, like the smell in the air, how it was bread or maybe cereal from the grain elevators and factories in the First Ward. They talked about children they had seen look up at them and laugh, pointing with crooked fingers. They talked about the lake and how it was probably beautiful.

They didn’t share all of their thoughts. Pete started to get a little afraid and wished that the knot at the bottom of every balloon was too tight to let the helium back out. He wished he was smart enough to know how to wiggle his body right to tighten it. The truth is that not all balloons are rubber and some are better at keeping their helium. Some are made of mylar. Another truth is that helium atoms are small and rubber is not built to keep in small atoms so the helium escapes not only from the hole in the knot but from the rubber itself.

Even though he had been excited to know what deflation brought, Pete was now dreading it a little. Dot was trying not to think about it. Those kids were so funny, she kept saying. William was tired and had never laid down but thought it might be nice. He couldn’t think straight for too long.

Balloons never sleep but all three fell into a state of stillness, aware of each other but lulled by the rhythms of worry and hope. The sun was not yet up but the sky to the east was lighter. Pete kept thinking to himself so that he would keep thinking at all. He could see the ground now. It was gray and there were tiny grooves in it that looked to go on forever in each direction. He wanted to follow them up the street but he couldn’t lift himself so he looked back down. He breathed quickly and Dot did too. William fell what seemed like asleep and the other two wanted to call for him but they were scared. Dot closed her eyes and tried to hold her breath as if to wait it out.

Pete kept looking at the grooves in the cement, where William now rested. Pete’s thoughts had been in words but he didn’t realize that after a while his thoughts were not language anymore. More like dull impulses. A feeling to move. A feeling to look up. To imagine the day. The sun rising above the buildings and the people that would pass by. He was not conscious of words at all now, nor of wonder or fear. He was of no mind, knowing only what his eyes could focus on, as if hypnotized by the very existence of things.

Featured image: 2 Islands by Jacquelyn Ross. This feature appears in issue 5, the Islands Issue. Download here.

The post Small Atoms appeared first on The Cluster Mag.

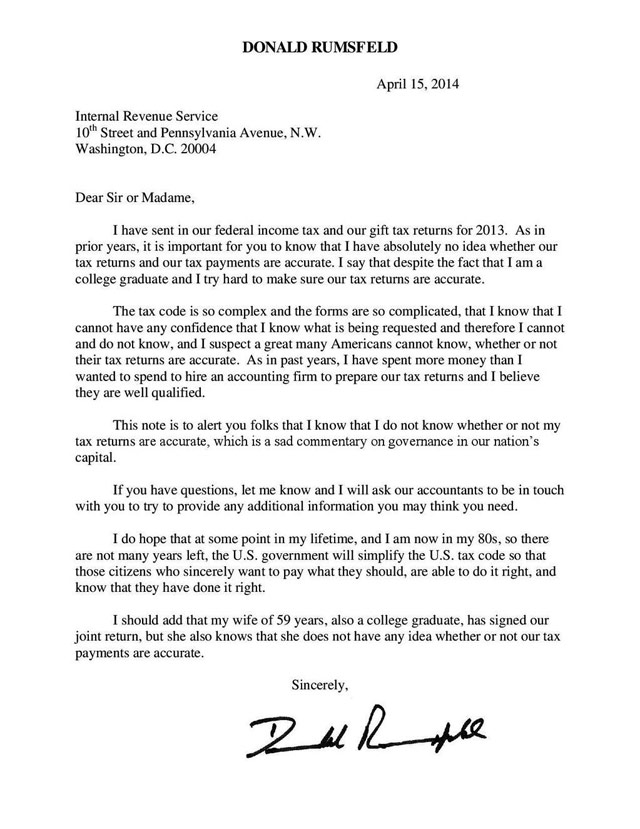

Rumsfeld to IRS: taxes are too damn complicated

JessKnown unknowns! Rumsfeld's only worthwhile contribution to humanity, probably.

Uh oh, Donald Rumsfeld and I agree on something. Each year, with his tax return, Rumsfeld sends a letter to the IRS explaining that neither he or his wife are sure of how accurate their taxes are because the forms and tax code are too complex. Here is this year's letter:

If only he had been less certain of his accuracy in an even more complex situation, like, say the whole WMD/Iraq War thing.

Tags: Donald Rumsfeld IRS taxesThe Dobsonian Telescope

"The design of this telescope is called a Dobsonian, after its inventor John Dobson, who passed away earlier this year. Dobson’s life took an unusual trajectory. He went from being a self described “belligerent atheist” to a monk in the Vendanta society to co-founding the San Francisco Sidewalk Astronomers. Most of his life was spent bringing the night sky to people around the world and teaching people how to make their own low-cost telescopes.

As a monk, Dobson could not afford expensive materials. He kept the design inexpensive by using a simple mount and cheap materials: wood and cardboard. My Dobsonian was made by the now defunct Coulter Optical Company out of particle board and a cardboard concrete form. Its large 13.1 inch mirror makes it perfect for looking at nebulas, galaxies and star clusters even in light polluted urban areas."

A look back at the Sony Walkman

JessI so totally wish that my iPod had a "Hot Line" feature! It would also be great if you could switch seamlessly from listening to your podcasts to recording whatever's going on around you.

Andrew Kim of Minimally Minimal got his hands on an original Sony Walkman and provides an interesting look back at a seminal piece of personal technology. Initially, the Walkman was billed as the "Walking Stereo with Hotline":

Next to the dual headphones is a button labeled "Hot Line". This was another key feature of the TPS-L2. When the user pressed the Hot Line button, the device would would override the music with audio from the built in microphone. It allowed you to listen to Subway announcements or talk to a friend without taking off your headphones. I find it to be a particularly clever idea as it uses existing parts from tape recorders. Hot Line wasn't really a sought after feature though, and was axed in later models.

(via @sippey)

Tags: Andrew Kim design Sony WalkmanIs the Oculus Rift sexist? (plus response to criticism)

Jessdanah boyd is so cool.

Last week, I wrote a provocative opinion piece for Quartz called “Is the Oculus Rift sexist?” I’m reposting it on my blog for posterity, but also because I want to address some of the critiques that I received. First, the piece itself:

Is the Oculus Rift sexist?

In the fall of 1997, my university built a CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) to help scientists, artists, and archeologists embrace 3D immersion to advance the state of those fields. Ecstatic at seeing a real-life instantiation of the Metaverse, the virtual world imagined in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, I donned a set of goggles and jumped inside. And then I promptly vomited.

I never managed to overcome my nausea. I couldn’t last more than a minute in that CAVE and I still can’t watch an IMAX movie. Looking around me, I started to notice something. By and large, my male friends and colleagues had no problem with these systems. My female peers, on the other hand, turned green.

What made this peculiar was that we were all computer graphics programmers. We could all render a 3D scene with ease. But when asked to do basic tasks like jump from Point A to Point B in a Nintendo 64 game, I watched my female friends fall short. What could explain this?

At the time any notion that there might be biological differences underpinning computing systems was deemed heretical. Discussions of gender and computing centered around services like Purple Moon, a software company trying to entice girls into gaming and computing. And yet, what I was seeing gnawed at me.

That’s when a friend of mine stumbled over a footnote in an esoteric army report about simulator sickness in virtual environments. Sure enough, military researchers had noticed that women seemed to get sick at higher rates in simulators than men. While they seemed to be able to eventually adjust to the simulator, they would then get sick again when switching back into reality.

Being an activist and a troublemaker, I walked straight into the office of the head CAVE researcher and declared the CAVE sexist. He turned to me and said: “Prove it.”

The gender mystery

Over the next few years, I embarked on one of the strangest cross-disciplinary projects I’ve ever worked on. I ended up in a gender clinic in Utrecht, in the Netherlands, interviewing both male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals as they began hormone therapy. Many reported experiencing strange visual side effects. Like adolescents going through puberty, they’d reach for doors—only to miss the door knob. But unlike adolescents, the length of their arms wasn’t changing—only their hormonal composition.

Scholars in the gender clinic were doing fascinating research on tasks like spatial rotation skills. They found that people taking androgens (a steroid hormone similar to testosterone) improved at tasks that required them to rotate Tetris-like shapes in their mind to determine if one shape was simply a rotation of another shape. Meanwhile, male-to-female transsexuals saw a decline in performance during their hormone replacement therapy.

Along the way, I also learned that there are more sex hormones on the retina than in anywhere else in the body except for the gonads. Studies on macular degeneration showed that hormone levels mattered for the retina. But why? And why would people undergoing hormonal transitions struggle with basic depth-based tasks?

Two kinds of depth perception

Back in the US, I started running visual psychology experiments. I created artificial situations where different basic depth cues—the kinds of information we pick up that tell us how far away an object is—could be put into conflict. As the work proceeded, I narrowed in on two key depth cues – “motion parallax” and “shape-from-shading.”

Motion parallax has to do with the apparent size of an object. If you put a soda can in front of you and then move it closer, it will get bigger in your visual field. Your brain assumes that the can didn’t suddenly grow and concludes that it’s just got closer to you.

Shape-from-shading is a bit trickier. If you stare at a point on an object in front of you and then move your head around, you’ll notice that the shading of that point changes ever so slightly depending on the lighting around you. The funny thing is that your eyes actually flicker constantly, recalculating the tiny differences in shading, and your brain uses that information to judge how far away the object is.

In the real world, both these cues work together to give you a sense of depth. But in virtual reality systems, they’re not treated equally.

The virtual-reality shortcut

When you enter a 3D immersive environment, the computer tries to calculate where your eyes are at in order to show you how the scene should look from that position. Binocular systems calculate slightly different images for your right and left eyes. And really good systems, like good glasses, will assess not just where your eye is, but where your retina is, and make the computation more precise.

It’s super easy—if you determine the focal point and do your linear matrix transformations accurately, which for a computer is a piece of cake—to render motion parallax properly. Shape-from-shading is a different beast. Although techniques for shading 3D models have greatly improved over the last two decades—a computer can now render an object as if it were lit by a complex collection of light sources of all shapes and colors—what they they can’t do is simulate how that tiny, constant flickering of your eyes affects the shading you perceive. As a result, 3D graphics does a terrible job of truly emulating shape-from-shading.

Tricks of the light

In my experiment, I tried to trick people’s brains. I created scenarios in which motion parallax suggested an object was at one distance, and shape-from-shading suggested it was further away or closer. The idea was to see which of these conflicting depth cues the brain would prioritize. (The brain prioritizes between conflicting cues all the time; for example, if you hold out your finger and stare at it through one eye and then the other, it will appear to be in different positions, but if you look at it through both eyes, it will be on the side of your “dominant” eye.)

What I found was startling (pdf). Although there was variability across the board, biological men were significantly more likely to prioritize motion parallax. Biological women relied more heavily on shape-from-shading. In other words, men are more likely to use the cues that 3D virtual reality systems relied on.

This, if broadly true, would explain why I, being a woman, vomited in the CAVE: My brain simply wasn’t picking up on signals the system was trying to send me about where objects were, and this made me disoriented.

My guess is that this has to do with the level of hormones in my system. If that’s true, someone undergoing hormone replacement therapy, like the people in the Utrecht gender clinic, would start to prioritize a different cue as their therapy progressed. 1

We need more research

However, I never did go back to the clinic to find out. The problem with this type of research is that you’re never really sure of your findings until they can be reproduced. A lot more work is needed to understand what I saw in those experiments. It’s quite possible that I wasn’t accounting for other variables that could explain the differences I was seeing. And there are certainly limitations to doing vision experiments with college-aged students in a field whose foundational studies are based almost exclusively on doing studies solely with college-age males. But what I saw among my friends, what I heard from transsexual individuals, and what I observed in my simple experiment led me to believe that we need to know more about this.

I’m excited to see Facebook invest in Oculus, the maker of the Rift headset. No one is better poised to implement Stephenson’s vision. But if we’re going to see serious investments in building the Metaverse, there are questions to be asked. I’d posit that the problems of nausea and simulator sickness that many people report when using VR headsets go deeper than pixel persistence and latency rates.

What I want to know, and what I hope someone will help me discover, is whether or not biology plays a fundamental role in shaping people’s experience with immersive virtual reality. In other words, are systems like Oculus fundamentally (if inadvertently) sexist in their design?

…

Response to Criticism

1. “Things aren’t sexist!”

Not surprisingly, most people who responded negatively to my piece were up in arms about the title. Some people directed that at Quartz which was somewhat unfair. Although they originally altered the title, they reverted to my title within a few hours. My title was intentionally, “Is the Oculus Rift sexist?” This is both a genuine question and a provocation. I’m not naive enough to not think that people would react strongly to the question, just as my advisor did when I declared VR sexist almost two decades ago. But I want people to take that question seriously precisely because more research needs to be done.

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination on the basis of sex (typically against women). For sexism to exist, there does not need to be an actor intending to discriminate. People, systems, and organizations can operate in sexist manners without realizing it. This is the basis of implicit or hidden biases. Addressing sexism starts by recognizing bias within systems and discrimination as a product of systems in society.

What was interesting about what I found and what I want people to investigate further is that the discrimination that I identified is not intentional by scientists or engineers or simply the product of cultural values. It is a byproduct of a research and innovation cycle that has significant consequences as society deploys the resultant products. The discriminatory potential of deployment will be magnified if people don’t actively seek to address it, which is precisely why I drudged up this ancient work in this moment in time.

I don’t think that the creators of Oculus Rift have any intentions to discriminate against women (let alone the wide range of people who currently get nauseous in their system which is actually quite broad), but I think that if they don’t pay attention to the depth cue prioritization issues that I’m highlighting or if they fail to actively seek technological redress, they’re going to have a problem. More importantly, many of us are going to have a problem. All too often, systems get shipped with discriminatory byproducts and people throw their hands in the air and say, “oops, we didn’t intend that.”

I think that we have a responsibility to identify and call attention to discrimination in all of its forms. Perhaps I should’ve titled the piece “Is Oculus Rift unintentionally discriminating on the basis of sex?” but, frankly, that’s nothing more than an attempt to ask the question I asked in a more politically correct manner. And the irony of this is that the people who most frequently complained to me about my titling are those who loathe political correctness in other situations.

I think it’s important to grapple with the ways in which sexism is not always intentional but at the vary basis of our organizations and infrastructure, as well as our cultural practices.

2. The language of gender

I ruffled a few queer feathers by using the terms “transsexual” and “biological male.” I completely understand why contemporary transgender activists (especially in the American context) would react strongly to that language, but I also think it’s important to remember that I’m referring to a study from 1997 in a Dutch gender clinic. The term “cisgender” didn’t even exist. And at that time, in that setting, the women and men that I met adamantly deplored the “transgender” label. They wanted to make it crystal clear that they were transsexual, not transgender. To them, the latter signaled a choice.

I made a choice in this essay to use the language of my informants. When referring to men and women who had not undergone any hormonal treatment (whether they be cisgender or not), I added the label of “biological.” This was the language of my transsexually-identified informants (who, admittedly, often shortened it to “bio boys” and “bio girls”). I chose this route because the informants for my experiment identified as female and male without any awareness of the contested dynamics of these identifiers.

Finally, for those who are not enmeshed in the linguistic contestations over gender and sex, I want to clarify that I am purposefully using the language of “sex” and not “gender” because what’s at stake has to do with the biological dynamics surrounding sex, not the social construction of gender.

Get angry, but reflect and engage

Critique me, challenge me, tell me that I’m a bad human for even asking these questions. That’s fine. I want people to be provoked, to question their assumptions, and to reflect on the unintentional instantiation of discrimination. More than anything, I want those with the capacity to take what I started forward. There’s no doubt that my pilot studies are the beginning, not the end of this research. If folks really want to build the Metaverse, make sure that it’s not going to unintentionally discriminate on the basis of sex because no one thought to ask if the damn thing was sexist.

Furoshiki: Zero-Waste Shopping in Japan

JessDUH! This is so great and smart.

In a time when cloth-making was one of the most advanced technologies, a piece of square cloth was all that a man needed to carry goods around. Japanese call it ‘Furoshiki’, a square cloth that with different wrapping techniques can basically transport anything. With its name meaning ‘bath spread’, Furoshiki is a traditional kind of wrapping cloth made of natural materials like silk and cotton. It is believed to date back to the 8th century. What was at first used to wrap up noblemen’s clothes in bathhouses gradually transported goods and gifts.

Click to enlarge. More pictures here.

Modern bags might have outshone Furoshiki, but recent years have seen its comeback as a green alternative to shopping bags, thanks to the ‘Mottainai Furoshiki’ initiative by Yuriko Koike, Japan’s Minister of the Environment, in 2006. “It’s a shame for something to go to waste without having made use of its potential in full,” said Koike. Like what beauty label LUSH has followed to produce, the modern Furoshiki Koike upheld was made of recycled PET bottles that, as the Minister put it, “can wrap almost anything in it regardless of size or shape with a little ingenuity by simply folding it in a right way.”

The above graph demonstrating different wrapping techniques went viral on the internet. A wave of shops emerged to sell fancy furoshiki. The Minister’s statement holds some truism because a furoshiki does wrap up almost anything of all shapes and fragility – from vegetables to bottles, from wine glasses to eggs, from a baby to a dog. Besides its diversity, Furoshiki is a great alternative to adopt also because of its portability, leaving almost no room for excuses like ‘I forgot to bring my own bag’. Most of the time very decorative because Japanese treat it as an artistic craft, a furoshiki makes a great scarf, headband or pocket square.

Light and small, it comfortably fits in your pocket or day bag, whilst some furoshiki clothes are big enough to a bag whose form you can change every other day. A personal experiment proves that it helps encourage shoppers to opt for less- or un-packaged options. To avoid unnecessary packaging I visit local grocery stores for unpackaged tomatoes and to the plastic bag addicts’ surprise, it is very easy and light to transport. Just think about how one piece of cloth has the potential to replace all shopping bags. Does it not make it one of the smartest solution to shopping bags and excessive packaging?

This is a guest post by Ren Wan, a writer and sustainability advocate who is based in Hong Kong. She runs JupYeah, an online swapping platform, is a managing editor for WestEast Magazine, and blogs at Loccomama.

Don’t Look Now

JessInteresting what perspective some time can lend to a story and its meaning.

Fifty years ago today the New York Times made Kitty Genovese the archetypical victim of urban apathy and violence. Now we know just how wrong they were

The original story of Kitty Genovese’s death, first promulgated by the New York Times in a front-page article 50 years ago today—young single woman brutally murdered while 38 strangers watched and did nothing—was incorrect in almost every particular.

The murder itself was horrifying, of course. The Times got that right. But the story that made Genovese a household name and a symbol of modern social dysfunction got nearly everything else wrong. From the number of witnesses to the details of the crime to the timing of the police response, there are by my count no fewer than 29 significant errors in the original Times story, five of them in its very first sentence.

Many of these mistakes have been public knowledge for years, and as the errors in the narrative have been tabulated the incident’s supposed meaning has been subject to ongoing revision. (In recent years the “bystander effect” has replaced “apathy” as the hook of choice.) But with the publication this month of Kevin Cook’s masterful Kitty Genovese: The Murder, the Bystanders, the Crime that Changed America, our understanding of the case, and of Genovese as an individual, is immeasurably enriched. Now, for the first time, we can move beyond mere debunking to construct a full and complex narrative of her life and death, and that new narrative reveals the old one as not merely deficient but fundamentally fraudulent. Some of the biggest flaws in the story, it is now clear, come less from what it got wrong than from what it left out.

Over the last 50 years, as the question of how much blame to assign to Genovese’s neighbors has been endlessly reargued, the broader framing of the case as a parable about urban anonymity and social malaise has stood largely unchallenged. The question at the heart of the original Times piece—how could this young woman’s neighbors have let her die when the police stood ready to help—has been answered in different ways, but the question has remained the same. The Times reporting, however, notoriously overstated the culpability of the witnesses—what they saw, what they knew, what they did.

Though the paper portrayed the neighborhood as gawking from their windows while Genovese was attacked again and again, in reality the vast majority of the witnesses saw little or nothing and heard only isolated screams. (On a working-class block that hosted a sometimes rowdy bar, late-night screams were hardly unusual.) Among the neighbors who saw or heard something that night (38 in the Times’ account, but 33 according to police records), only two witnessed enough of the incident to develop a clear and coherent understanding of what was happening.

One of those two, Joseph Fink, fit the Times’s witness profile perfectly. An assistant super and doorman at an apartment building across the street from where the first attack occurred, Fink sat at his post for several minutes watching serial rapist Winston Moseley attack Genovese. He saw Moseley’s knife. He saw Genovese stabbed. And then he got up and went to bed.

When Fink left the scene Genovese was still alive, and Moseley would soon be temporarily scared away by another neighbor’s intervention. But Moseley would return a few minutes later, and it was his second attack that killed Genovese. That attack had only one witness — a witness whose relationship to the victim turns the Times’s thesis of urban anonymity on its head.

Karl Ross heard the first attack — at least he heard screaming. Then the screams died down and for a few minutes he heard nothing. But soon he heard other sounds, sounds coming from the lobby of his own building. Genovese had staggered there after Moseley had been scared off, but he had tracked her down. In the foyer, away from the eyes of the community, he was attacking her again. Now Ross was the only one who could hear. He hesitated, then opened the door to his apartment. He saw Genovese being attacked, just a flight of stairs away. He looked into her eyes, and those of her attacker. And then he closed the door.

Unlike Fink, Ross didn’t go to bed after witnessing the attack. He called a friend, asking for advice. When that friend told him to stay out of it, he called another. That friend told him to come over to her house, and he did — climbing out his window to avoid the scene in the lobby. When he got there that friend called a third, who called the police. The cops arrived a few minutes later.

When the Times reported on the murder, it was Ross’s feeble explanation to the police — “I didn’t want to get involved” — that summed up the story. His reaction was portrayed as nonchalant, brazen. But what the Times didn’t say was that Ross was involved. He knew Kitty Genovese. They were friends. He had recognized her when he saw her being stabbed in his lobby. By one account, she had called him by name.

So why didn’t he act more quickly?

We don’t know for sure. Ross never gave a detailed public account of his actions, and was never called to testify at the trial. He moved away not long after the murder, and soon disappeared entirely. But we do know a few things about Ross. We know that he was a drunk, and that he was drunk that night. We also know that he was gay, that he was closeted, and that he was afraid of the police. For Ross, cops weren’t just a potential source of assistance. They were also a potential threat.

In New York City in 1964 homosexuality was illegal, as it was in 49 of America’s 50 states. Gays and lesbians were subject to pervasive, intense persecution, abetted by the same New York Times that now professed mystification that any of the presumptively “respectable, law-abiding” witnesses to the Genovese murder would decline to call the authorities. In a major article published just three months before Genovese’s death, the Times had sounded alarms about the “growth of overt homosexuality” in the city, calling the “increasing openness” of the city’s gays and lesbians a major moral, psychiatric, and law-enforcement crisis.

It’s unclear whether the police or the Times ever learned that Ross was gay, or that his fear of exposure and persecution may have played a part in his hesitancy that night. What they did know, however, and chose to keep secret, was that Genovese was gay as well.

Today, the tale of Genovese and Mary Ann Zielonko’s courtship would be a central, heart-rending component of the case’s media coverage. They had met briefly at a bar, and Kitty had been smitten enough to track Mary Ann down weeks later and pin a note to her apartment door, telling her to wait at a payphone downstairs at a specified hour for her call. The two went home together at the end of their first real date, found a shared apartment within weeks, and shared their first Christmas together three months before the murder, staying with Genovese’s family in Connecticut over the holidays and exchanging wallets — one black and one brown, otherwise identical — as gifts. Zielonko was waiting at home for Genovese on the night of the murder, and the cops knocked on the couple’s door to tell her Kitty was dead at four in the morning of the day that would have been their first anniversary.

This story is heartbreakingly sweet, but in 1964 it was buried. The Times described Zielonko as Genovese’s “roommate” throughout its coverage of the case, and the cops and prosecutors made sure that the Moseley jury would never hear about the relationship, even as they called Zielonko as a witness at trial. Genovese’s lesbianism was deemed a distraction—homosexuality was relevant for defendants, not victims, back then. (An indication of the authorities attitudes toward sexual nonconformity can be seen in the fact that Moseley’s prosecutor cited the defendant’s willingness to perform cunnilingus on a menstruating woman as perversion on par with his confessed necrophilia.)

Just as the possibility that her neighbors might have had reason to fear the cops had to be erased to render their hesitancy to pick up the phone incomprehensible, Genovese’s biography had to be erased for fear of complicating the narrative. This erasure was literal as well as figurative, and it extended beyond Genovese’s romantic life. The most famous photo of Genovese, one which the Times has run innumerable times over the last fifty years, is actually a crudely-cropped mugshot, a memento of a 1961 incident in which an undercover cop had induced her to place a $9 horse-racing bet on his behalf at her bartending job.

Kitty Genovese’s lesbianism was not directly relevant to the case, and neither was her own complicated relationship to the police. She never had the chance to decide whether to call on them that night and they never had the chance to interact with her before she died. It’s worth noting, however, that while the Times asserted that she changed her route from her car to her apartment in order to put herself in the path of a police callbox, it’s at least as likely that she was seeking the safety of the pub on the corner.

***

Genovese, her friends, her neighbors—all had real reasons to distrust the cops. We’ll never know for sure whether those fears contributed to the loss of Kitty’s life, but neither do we know whether the police would have successfully intervened to save it had they been called earlier. One witness to the crime, in fact—then a teenager, now a retired police officer—says his own father did call the police early on in the attack, but that the call was never followed up on. That claim is unverifiable, but it’s lent credence by a horrifying incident that took place a few years later.

Winston Moseley was convicted of Genovese’s murder in the summer of 1964 and imprisoned upstate. In early 1968 he was transferred temporarily to a local hospital for treatment of a self-inflicted injury, and while there he was able to take advantage of lax security and escape.

Upon his escape Moseley broke into an unoccupied house and called a cleaning service to send a maid over. When the woman arrived, he raped her several times before letting her go. Scared of, and threatened by, Moseley, the woman did not call the police, but she did manage to get contact information for the homeowners and warn them that someone was there.

Those homeowners, a married couple, called the police, but when they did they were rebuffed. There was a shift change coming up in an hour and a half, they were told, and no officers were available. They should call again later. Nervous about their property, and a gun they knew was on the site, they decided not to wait. When they arrived they were confronted by Moseley, who had found the gun. They were tied up and robbed. She was raped. Moseley left in their car. It was not until after Moseley broke into another house and took more hostages that he was finally apprehended.

From the moment the New York Times took it up as a cause, the Kitty Genovese story has counterposed police rectitude against community violence, cowardice, and confusion. Genovese’s murder is a parable in which the absent cops are the heroes and her neighbors eclipse even her killer in their culpability for the crime. Subsequent debates over the story’s meaning have centered almost exclusively on that claim of culpability, and on the question of to what extent those neighbors can or should be exonerated.

But Genovese herself lived in fear of police persecution, both at work and in her personal life. At least one witness to the crime, a friend of Kitty’s, also had good reason to be wary of law enforcement. And once the cops did engage with the case, they failed spectacularly to provide the kind of assistance the legend assumes they stood poised to offer that night. The Genovese story isn’t just a story of individual moral culpability, it’s also a story about malign and corrupt institutions and the corrosive effects those institutions have on our lives, and one of the real services Cook’s new book provides is the restoration of those effects to the broader narrative of the case.

***

Abraham Rosenthal had been the Metro Editor of the Times for less than a year when Genovese was killed. It was Rosenthal who was told the parable of the Genovese killing by a source in the police department, and Rosenthal who assigned the story that made Genovese famous. It was Rosenthal, too, who had been the engine behind the paper’s campaign against the city’s gay menace—a campaign that continued well into the age of AIDS.

Rosenthal wrote an early, slender book on the murder. In it, he posed the dilemmas posed by the Genovese case as fundamentally personal, internal ones—questions about how each of us responds to moral challenges, about the human impulse to turn away from suffering. This was a story, he wrote, about “the disease of apathy”—a disease which, almost by definition, has no cure.

In a new edition to his book, published three and a half decades later, Rosenthal returned to this theme, presenting the witnesses’ motivation as simultaneously self-evident and unknowable. If we knew more about them, he asked, “Would it tell us what we wanted to know?” No. He was pretty sure it wouldn’t. What they had done, he concluded, was as inevitable as it was incomprehensible, as predictable as it was monstrous.

And with that he turned away.

Bob Neill’s Book of Typewriter Art (with special computer program) (1982)

JessSo great.

“Bob Neill, artist of the typewriter, was born in the Kent village of Aylesford and practises as a professional Hypnotherapist in the County Town of Maidstone. He first started typing pictures on his typewriter in 1960, having read about a woman in Spain who was producing this form of typewriter art. His first effort was a portrait of a magazine cover-girl which was published in the Star evening newspaper.

He then continued with his newly-discovered hobby, producing pictures and portraits which have been exhibited widely and published in various magazine and journals. A selection of his work appears in this book together with the secrets of Typewriter Art and a computer programme to enable some of the pictures to be produced on a home computer (such as the Commodore PET) using the BASIC computer language.

So many people have asked him how to start this new-found hobby that he come [sic] up with the idea of writing patterns for his pictures so that more people could enjoy the hobby of Typewriter Art. He has perfected the method over the years making it so easy that even children of eight have produced excellent pictures unaided.

Bob Neill’s Book of Typewriter Art gives you the chance whatever your age or artistic ability, to create for yourself fascinating pictures on the typewriter by following the simple instructions and patterns within these pages. What Bob Neill has worked out with painstaking care over the years can be yours to enjoy as you begin the absorbing and fascinating hobby of Typewriter Art.” (from the back cover, via Juliette Kristensen)

Images include that of Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip, Prince Charles, Princess Diana, a Horse, a Prarie Wolf, a Siamese Kitten, a Red Setter, a White Persian Cat (Full Body and Head Only), Telly Savalas (Kojak), Elvis Presley, a Tiger, a Bush Baby, a Mountain Scene, The Rose, The Nude, The Arab, The Pope and a Mystery Picture.

Publisher Weavers Press, Cornwall, 1982

ISBN 0946017018

176 pages

via Lori Emerson

Download (55 MB)

The Dailies (No Comments)

JessThe Dark Empty is my new favorite band name.

The Dailies (No Comments)

JessYeah, I can't wait til everyone's complaining about how hot it is.

More than 700 new planets discovered today

JessThat's a lot of planets!

NASA announced the discovery of 719 new planets today. That brings the tally of known planets in our universe to almost 1800. 20 years ago, that number was not more than 15 (including the nine planets orbiting the Sun). Here's a rough timeline of the dramatically increasing pace of planetary discovery:

4.54 billion BCE-1700: 6

1700-1799: 1

1800-1899: 1

1900-1950: 1

1951-1990: 1

1991-2000: 49

2001-2005: 131

2006-2010: 355

2006: -1 [for Pluto :( ]

2011-2014: 1243

Last year, Jonathan Corum made an infographic of the sizes and orbits of the 190 confirmed planets discovered at that point by the Kepler mission. I hope the Times updates it with this recent batch.

Tags: astronomy infoviz Jonathan Corum NASA scienceThe frequencies of humanity

JessPeople should be adopting dogs from shelters more than that.

Related to my post on the frequency of humanity is this post on XKCD on the various frequencies of events, from human births to dog bites to stolen bicycles.

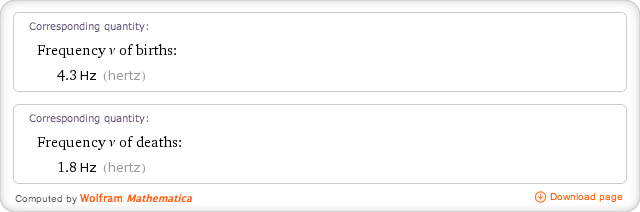

Tags: Randall Munroe scienceThe frequency of humanity

Every day on Earth, an estimated 371,124 people are born and 154,995 people die. When you ask Wolfram Alpha about these rates, the scientifically inclined site returns a curious corresponding quantity: the frequency in hertz (aka the number of cycles/second in a periodic occurrence).

Measurement in hertz is an unusual way to think about living and dying; hertz are typically reserved for things like human-audible sound frequencies (20 to 16,000 Hz), how fast your laptop's CPU runs (1 to 4 Ghz), or the frequency of the power running into your house (50 to 60 Hz). But if you subtract the death rate from the birth rate, you get a net rate of 216,129 new people a day, or about 2.5 Hz. That's the frequency of humanity. While that's a lot slower than your computer, it's in the same frequency ballpark as a human's resting heart rate (1.3 Hz), steps taken while walking briskly (1.8 Hz), or moderately energetic dance music (2.25 Hz).

Note: Illustration by Chris Piascik...check out his shop, where you'll find prints, tshirts, iPhone cases, etc.

Tags: scienceStuds Terkel interviews Bob Dylan

JessMore for Studs than Dylan.

In 1963, Studs Terkel interviewed a 21-year-old Bob Dylan, before he was famous.

In the spring of 1963 Studs Terkel introduced Chicago radio listeners to an up-and-coming musician, not yet 22 years old, "a young folk poet who you might say looks like Huckleberry Finn, if he lived in the 20th century. His name is Bob Dylan."

Dylan had just finished recording the songs for his second album, "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan", when he traveled from New York to Chicago to play a gig at a little place partly owned by his manager, Albert Grossman, called "The Bear Club". The next day he went to the WFMT studios for the hour-long appearance on "The Studs Terkel Program".

Dangerous Minds has more detail about the interview.

Bob Dylan is a notoriously tough person to interview and that's definitely the case here, even this early in his life as a public persona. On the other hand, Terkel is a veteran interviewer, one of the best ever, and he seems genuinely impressed with the young man who was just 21 at the time and had but one record of mainly covers under his belt. Terkel does a good job of keeping things on track as he expertly gets out of the way and listens while gleaning what he can from his subject. It's an interesting match-up.

Dylan seems at least fairly straightforward about his musical influences. He talks about seeing Woody Guthrie with his uncle when he was ten years old (Is this just mythology? Who knows?), and he mentions Big Joe Williams and Pete Seeger a few times.

Much of the rest is a little trickier. Terkel has to almost beg Dylan to play what turns out to be an earnest, driving version of "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall." Dylan tells Terkel that he'd rather the interviewer "take it off the disc," but relents and does the tune anyways.

(via @mkonnikova)

Tags: Bob Dylan interviews music Studs Terkel video