Shared posts

How to Practice Epictetus’ Disciplines for a Good Life by Massimo Pigliucci & Gregory Lopez

Imbecilli.

Ragazzi irragiungibili

“Il vostro bambino è al momento irraggiungibile, potrebbe aver spento il cellulare o si trova scuola”, magari sentiranno questo nell’anno prossimo i genitori in Francia.

Ma il contadino non ha trovato l’altro elemento nelle notizie italiane: il ministro Blanquer vuole anche istituire i cori in tutte le scuole.

Mosse controcorrenti che hanno effetti molti salutari nel futuro.

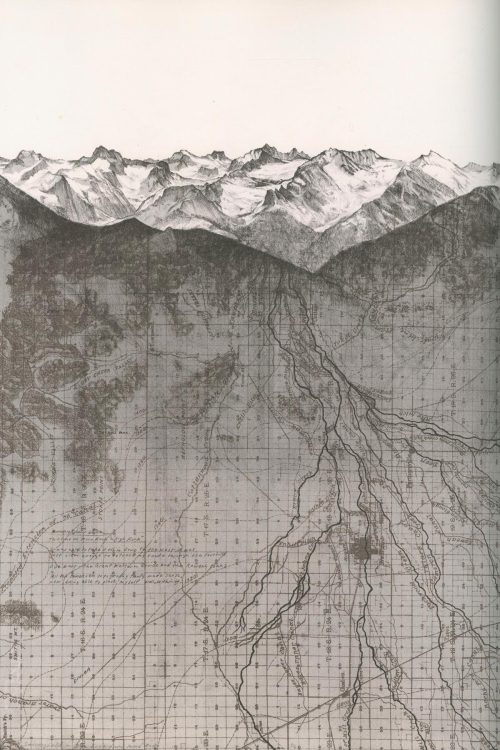

Spagna profonda: in cammino verso il vuoto

Want More Time? Get Rid of The Easiest Way to Spend It

For the month of May I time-traveled back to 2007, when social media platforms were still just websites you visited. I removed Facebook, Twitter and Reddit from my phone. Throughout the month, if I wanted to use those platforms I had to log in manually at my desk.

This decision came after experiencing a through-the-looking-glass moment while listening to an interview with Tristan Harris, former “design ethicist” at Google. I had always known it was easy to waste time on social media, but I hadn’t quite understood how engineered our social media habits are.

The big services are designed to exploit our psychological vulnerabilities, particularly our need for frequent signals of approval from others: thumbs-up, gold stars and hearts. These small hits of pleasure are enough to keep us checking in early and often, so that our attention can be sold to advertisers. That is the business model. (More here: How Billionaires Stole My Mind)

I didn’t want to quit outright, as many people have. I just wanted to get away from the ubiquity of Facebook, Twitter and Reddit. I didn’t want them in my pocket. I didn’t want to find myself swiping through them without having decided to. I wanted them to return to what they used to be: fun websites you may or may not visit on a given day.

What I learned

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was nothing difficult about not using these services once they were off my phone. I didn’t miss them, but I did find myself, many times a day, taking my phone out and absently swiping through it. This impulse usually came at moments when there was some waiting to do: when food was heating in the microwave, when a friend had departed to the bathroom, or even when a website was loading slowly on my laptop.

By Day 6 my phone had become a much less interesting object. I took it out much less often, and spent little time on it whenever I did. The absent-minded swiping impulse, whenever it still happened, became a reminder to either get to whatever responsibility I was avoiding, to wait mindfully, or to read a book or an article. (I made good use of an app called Pocket, which stores online articles for later reading offline.)

Whenever I did log on to Twitter, Facebook, or Reddit, I found them quite boring, and even kind of repulsive. This is how I put it in my log:

…after taking even a little time away from these platforms, whenever I check in I can’t help but see them as repositories for stray feelings, and energy that we don’t want to spend on anything consequential. They seem like places to go when you’re bored, or when you’re actively avoiding the thing you know you should be doing. I know a lot of this feeling is pure projection—I have certainly used these platforms that way.

Since the experiment began, I’ve felt an abundance of time. Part of this is the 45 or 90 minutes I’m no longer spending frivolously online every day, but it’s mostly that I’m no longer constantly recovering from interruptions. I stay with offline activities for longer stretches, and become immersed in them more easily. An hour seems like a longer unit of time now. (Because I know someone say something if I don’t, I’m aware this phrase “spending time” seems to contradict this recent post, but it doesn’t—its point is that “having/spending time” is a language convention.)

Social media was serving, at least for me, as a sponge that wicks up any stray attention—and with it, time—and then keeps drawing more of both until you consciously break away from it. And of course it does—unlike reading, working, physical activity, or real-life socializing, social media is an activity that takes no effort. It doesn’t require any confidence, resolve, or intention, and doesn’t entail any risk.

Essentially, I had removed the easiest way to spend time from a long list of possibilities, so that all that’s left are activities that require at least a little commitment and resolve. I’m reading more, walking more, socializing more, and working without so much self-prodding. I feel freer than ever to do these things, because there’s no ultra-easy competitor undercutting them. And there’s all this new time.

Facebook knows you have better things to do

It was around Day 9 that the most telling thing happened: Facebook noticed my absence. When you stop posting things, eventually the stream of notifications dries up, because there’s nothing for people to Like or reply to. Typically I would log in and see no notifications, quickly scan my news feed, and close it up.

One day, I was surprised to find a few notifications. My first thought was that somebody commented on, or liked, some old photo or post of mine.

But nobody did. I was being shown a new kind of notification: “Check out Jim’s comment on his photo” or “Jane commented on her status” as though someone else using Facebook is something I ought to be notified about.

These contrived notifications were the “Emperor wears no clothes” moment for me. It became obvious then that Facebook knows its users have better things to do, and quietly hopes they don’t notice how little they get out of it. It knows that most of the value it delivers is on the level of lab-rat food pellets: small, scheduled hits of gratification we’ve learned to expect many times a day. Facebook hasn’t been about its original purpose—keeping in touch with friends we might otherwise drift away from—since the mid-2000s, when:

- we had many fewer ways to keep in touch

- Facebook made no money

- we hadn’t yet discovered that maintaining hundreds of superficial online relationships doesn’t really enrich our lives

“Notification gratification” isn’t all people get out of Facebook, of course—we do want to see our friends’ photos (sometimes), and cute animal videos aren’t unwelcome once they’re playing in front of us. But those things aren’t persistent enough incentives to keep users checking Facebook multiple times a day—it shouldn’t need to be said, but Facebook’s customers aren’t its 1.3 billion daily users, but its five million advertisers. The little number in the red circle is the first place our eyes go when the page loads. It’s the reason we come back so frequently, and the reason advertisers are willing to pay what they do.

Do I really take my phone out of my pocket while I’m waiting in line somewhere because I’m suddenly struck by an urge to see my friend’s vacation photos? No, it’s because I’ve learned that in my pocket there is an ever-renewing promise of a small reward: someone may have mentioned me, or liked something I said. If, after that, I go on to peruse photos and articles and short diatribes, that’s merely incidental.

Even my beloved Instagram is jumping the shark. There are increasingly more ads, and now they’ve begun to jumble up the feed chronologically, so that you see your friends’ posts from throughout the week—a picture from ten minutes ago, then one from six days ago, then one from eight hours ago, and so on. Ostensibly this is for “bringing users the experience they want” even though Instagram’s users unequivocally do not want this and still have no option to turn it off.

What this unwanted change really does is ensure a steadier stream of waiting notifications, as users’ posts are dripped out to followers over the course of a week, instead of spiking immediately and dropping off quickly. Facebook bought Instagram in 2012 for a billion dollars.

What now?

So social media has kind of lost me, or at least its 2017 version has. I’m not quitting these services, but I remain committed to using them 2007-style: deliberately rather than reactively. I’ll use them to share things I think people will want to see, to get in touch with people when there are no better methods, to send and receive invitations to real-life events, and to see what people are up to when I consciously decide to see what people are up to.

But I’m done using them as an unwitting Pavlovian dog. They’re off my phone for good, I’ve deleted the quick-launch icons in my desktop browser, and I’m prepared to memorize passwords again. In spite of all of Facebook and Twitter’s attempts to make it difficult, I’m going to use them like websites.

***

[If you’re interested in another person’s experience, my friend Cait did a complete social media detox last month too, and had some interesting revelations.]

Photo by vodaphone medien

How To Be a DIT – Interview with Charlie Anderson

How To Be a DIT – Interview with Charlie Anderson

- Learn what it takes to be a professional DIT

- Understand what is in a professional DIT cart

- Pick up insider DIT tips and tricks

Charlie Anderson is a DIT and Director of Photography (IATSE Local 600), who has worked on feature films and TV shows such as HBO’s Vinyl, 22 Jump Street, The Drop and Amazon Studio’s Z:The Beginning of Everything.

Thanks to this post’s sponsors Pomfort, the makers of industry standard DIT media management tool Silverstack and on-set colour grading software Live Grade, I got to interview Charlie on what it’s like to be a working DIT, what’s in his (ever-evolving) DIT cart and why he relies up on Pomfort’s tools to get the job done, quicker and more reliably, than with any other software.

I recently got to take a look at a beta of Pomfort’s brand new application Silverstack Lab, which incorporates new dailies creation features into the Silverstack eco-system, which you can read all about in this post.

Charlie and I cover a lot of ground in this interview, but one of the things that stayed with me the most was his wisdom on how to make your way into the industry and rise through it’s ranks.

It’s the kind of wisdom that applies to almost any role within production and post, yet you’d be astounded how many people you meet, who fail to heed it.

That wisdom boils down to ‘don’t be a jerk‘, but as you’ll see, there’s a lot more to it. Especially when you’re in the privileged position of being a Digital Imaging Technician who crosses paths with Producers, Directors, DPs and powerful Show Runners.

Making all the right moves could propel your career into the stratosphere or one miss-step could quickly crater it.

But first a bit of context…

Charlie’s background is in Computer Science, which has served him well in the role of DIT. He enjoys the combination of creative and technical problem solving he faces on a daily basis, as well as being thrust into sometimes challenging on-set scenarios that consume his attention.

His ultimate goal is to shoot more and make a career for himself as a DP, but being a DIT is giving him access to a smorgasbord of professional Directors of Photography who have turbo charged his own learning and opportunities.

His break into the industry was ‘pure happenstance’, in that he was picked off the 600 availability list by DP Reed Morano four years ago. Reed took a liking to Charlie and the two have worked together frequently ever since.

Reed has subsequently moved into directing more and more, and has brought Charlie on, time and again, as part of her required crew.

We did The Inevitable Defeat of Mister & Pete and then Skelton Twins and then job after job after job and then Vinyl a couple of years ago.”

Working with Reed helped him build connections in the rest of the industry, or as Charlie puts it

Oh you work with Reed, you must know what you’re doing, so let me hire you for some more stuff.

Charlie been freelancing as a DP and DIT for over 10 years now.

What do you think that people in the industry most don’t understand about what a DIT really does?

If you think about it in terms of pure numbers. If you’re working on a show like Vinyl that might have like, say a $200 million dollar budget for 9 episodes. That’s $25 million per episode and it’s 15 [filming] days.

So that works out to roughly 2 or 3 million dollars a day and you’re the keeper of the footage. So if you screw up you might have cost production 2 to 3 million dollars in footage.

When you break it down that way, that could possible weigh on you, just a little bit! But seeing it that way, also really helps producers too.

I’ve been doing this for 10 years so I don’t really think about it like that anymore. But when I first started out, I was so stressed out, checking all the cards all the time, constantly checking all the files.

I didn’t have Silverstack back then, I had Shotput Pro, and there was an instance where Shotput wasn’t throwing out an error when it should have been, and at the end of the day I was checking the integrity of all the cards by hand and I realised, none of these cards copied! I’m glad I didn’t format anything!

What people may not know, is that a DIT is more than someone who just sits at a monitor all day.

We’re paid about the same as a camera operator because we’re there making sure that there’s not stuff in the frame, we’re there for your first AC, for your focus pullers – for making sure that they’re doing their job, seeing where they might have issues or problems. We’re second set of eyes for them.

We’re with the DP to make sure that he or she is able to catch everything. She may not see a bounce that’s caught in the reflection of this window over here. But you can see it and you can point it out.

The other thing is, as a DIT, you’re not really supposed to make like lighting decisions because it’s not your job to make lighting decisions.

It’s not your job as a DIT to tell your DP how to light. That’s his or her job. You’re there to assist them. You’re there as a second set of eyes to everybody in the camera department and you should help out in the camera department.

So you know, it’s like it’s very much like editing, in that when editing is good, you don’t notice it. When a DIT is good. You don’t really notice it, but things run more smoothly.

You’re there to help and be an integral part of the camera department. You’re not there to boost ego. You can’t say I’m the DIT. I don’t touch my cart. I don’t run cable. No man. You’ve got to help out. a) that’s how you get the day done faster and b) it’s just like ‘don’t be a jerk’.

With DITs personality is key because you’re in a pretty good position.

You get to talk with producers, you talk with directors, you talk with the DP. You talk with a lot of powerful people who have been around in this industry for many years and who have lots of connections. So it’s easy to make friends and and it’s very easy for you to shoot yourself in the foot.

You’ve got to humble yourself and remember that in reality a production can get a way without a DIT on set. But, it really helps to have a DIT on set because we bring so many valuable things to set, and to helping everybody out.

But still, ultimately we’re a line item.

We’re one of the first things that goes when they need to cut money. So you need to give them every reason to want to keep you. Even if that’s just being a nice person to have around on set as a valuable member of the camera department.

I think it can be hard for us to justify our position sometimes, but ultimately we do save productions quite a bit, even if it’s in re-shoot value or just peace of mind.

What’s the bit that’s the most fun for you?

90 percent of the jobs that I do, I’m doing iris pulls. I used to be a Focus Puller so I like having… you know in one hand you’re doing an iris pull and the other you’re trying to adjust colour at the same time.

Or you have two cameras and you’re controlling multiple cameras at the same time… so anything that puts you in the moment, where you’re totally focused on this thing for 10 seconds or whatever.

And it’s also an amazing learning environment, as I get to see how different DPs handle different things and I can lock that away in the back of my mind, for when, you know later on down the line in my career, as a DP, if I get into the same situation I can borrow from them.

Has being a DIT, meant you’ve learnt things from DPs that you couldn’t have learned any other way?

Oh yeah. You’re the middle man between production and post. You are the liaison. So anything that the DP might want to change [about the image] he goes through you to communicate to post-production.

I’ve definitely learned so much just by asking DPs “Why did you do this?” Like, ‘why did you put this diffusion here as opposed to there? And, hopefully, they’ll try to explain it to you, if they’re nice enough.

I’ve worked with a couple of DPs who don’t like to be asked questions, but most DP and especially in episodic form will be happy to explain their thinking. It’s all about timing too.

If they’re really stressed out it’s not a great time to talk to them about this kind of thing. You have to feel it out a little bit, but there is one DP that I work with, David Franco, he’s a super nice guy and he’ll tell you anything you want to know.

Same with David Mullen, who did the pilot for The Marvellous Mrs. Maisel. Actually, when we had a third camera in, I asked him if I could operate, because I shoot as well, and he was like “Yeah sure, why not.” So I got to operate for him and I had my protégé come in and take over DIT duties for that. That was pretty cool.

As a DIT you do have a window into seeing things firsthand, because you can go on set to see how the lighting is set up physically, and then go to your tent and see how it looks onscreen. You know, the filtration is adding this, the depth of field is doing that… and you get instant feedback being able to see the image from on-set through to almost postproduction.

What is the process that an image goes through on a modern film set, as seen through the eyes of a DIT?

[Editor’s Note: deLOG is just the image transposed out of LOG to say, Rec. 709, a film emulation LUT or a low contrast curve. It gives the crew an image with at least some contrast to work with rather than being a flat grey image. Further note: Paralinx and Teradek are systems for wireless video monitoring.]Essentially the workflow on set is:

I’ll take a LOG signal out of camera, to my station via a Paralinx or Teradek Colr, or something like that. Then I have my deLOG and my CDLs (Colour Decision Lists) on top of that.

The DP and I sit in the tent and talk about what he or she wants to achieve creatively. That images gets passed down the chain to Video Village and to the Assistant Camera (AC) crew who have their own smaller HD monitors which I’ll just put the deLOG on so that way they have a contrasty image.

If they have something like a 17 inch monitor they pull focus from, and they don’t have the ability to put a LUT into it then I use a Terradak color and I’ll throw the deLOG on that, and then just slap that on their monitors so they have essentially a LUT’d image to work with. But I can still get LOG.

The idea is that I want LOG all the time. I want to see the image the sensor is capturing. That way when a DP asks to see the LOG it’s a button press, as opposed to asking them to wait for 30 seconds or more. They want to see it that second they don’t want to sit there and wait because they have a million other things to do.

After that I also take screenshots of our on-set colour choices. That way I can send that on to postproduction, along with the CDLs, deLOG and stills, so they can clearly see: here’s what we did on set. Here’s how the CDLs should match up.

That way if there’s of some sort of change, or whatever, Post can see this is the change that should be reflected in the CDL. I’ve had jobs where, actually it was Reed, who lit a tungsten scene and had me colour it for night. She wanted it to look like moonlight but she didn’t have HMI she only had Tungsten, so I did that and then when we got the dailies back it was like “Oh. Everything’s Tungsten.” They didn’t look at my CDL whatsoever.

At that time it was early in my career, but I was doing screenshots so it was a foolproof way of me saying “No, this is what we did on set. Here’s what I sent you. You didn’t apply it.”

It’s essentially protecting yourself. That way a) You have reference for later on and b) you can say to the DP “Look here’s what we did. I sent this to them. Somewhere down the line it got screwed up.”

But nowadays it’s very rare that happens because everyone is on board now. Nobody is fighting for a job anymore, like it was in the beginning, where post-houses were trying to get rid of DITs because they thought that DITs were a threat to them. that kind. Now it’s all very symbiotic in my opinion.

So anyway, Post will get all of the CDLs, stills and deLOG with all the LOG files and then they’ll do all the transcoding. I’ll see dailies too, so I can QC them and make sure everything’s good. That’s pretty much the workflow at this point.

How early on in pre-production are you involved? Are you setting LUTS/Looks on camera test footage?

Well I try to be involved as early as possible.

Typically I’ll sit with the DP and create the show LUT or the deLOG as early as the camera tests, whether that’s a hair and makeup test or wardrobe test or whatever. Because that way he or she is able to look at the fabrics and the colour choices and see how the camera responds to certain things. They are also testing lenses and filters and all sort of other things too.

So we’ll take those tests and we’ll sit there for a full day just going through and looking at stuff. Tweaking it and looking at things and then we’ll take that into the colour suite, into the DI with the colorist and sit there and futher tweak it.

That will be me, the DP, the colorist and maybe their dailies colorist is also there. We’ll sit there and tweak and tweak a deLOG to get a it to where everybody is happy and then the colorist will just export the deLOG and send it to me.

But it’s a very collaborative process. It pretty much starts with me and the DP. We’ll get 90 percent of the way there and then and the colorist will essentially do the final deLOG.

There is a show coming up that I did the pilot for, The Marvellous Mrs. Maisel, which starts shooting in May. But we did kind of like a REC. 709-ish look, though not quite as contrasty. But this show is also finishing in HDR, so the colorist, Steven Bodner created an SDR version of the HDR curve to send to me to view on set. That way, when they do the HDR final colour, they can work off of the SDR and everything matches up perfectly.

Has the growth of delivery formats made your life more complicated?

Not really. It’s pretty much the same thing. I just have to stay on top of the terminology, the workflow. Knowing how everything works.

That way when somebody asks me something, at any point in time on-set, I can give them the correct answer. Even if I don’t know all the details of how that works, I know what needs to get done.

What do you actually do to prep?

I keep a full check list that I keep updating but I run through it before every show.

Some producers think “You’re a DIT. It’s a TV show. You’ve only got to set up hard drives right?” I’m like, no.

You’re on preparing and prepping with the DP for colour choices. You’re trying to pick out different aesthetics, as to what he or she wants. You’re doing research or trying to figure out answers to questions like “what’s the difference between the Alexa SXT versus the XT”… you need to know answers to all these sorts of things.

For instance, my prep lists consists of 6 different categories. The project category contains:

- Confirm camera settings with production team and DP

- Figure out colour preferences and references

- Camera settings and resolution

- Miscellaneous shoot information, camera codec setups, frame rates [They may want to shoot 23:98, but sometimes 24 or 60 or maybe 29:97 for certain things.]

- Set all my frame lines for the directors and DP

- Colour space settings

- Setting up the AC’s monitors with a LUT box etc.

- Prepping cards, labelling cards, making sure everything rolls properly, that you can get all your maximum frame rates.

- Talking to sound, VTR, editorial etc.

- Calibrating monitors

- Testing cables and batteries

- Understanding your camera orders, because different lenses have different looks to them.

On my cart I have Preston single channel iris controllers. So I have to test all the lenses for iris control and see if they all line up. If they don’t I have to make an iris ring for every single lens.

So it’s a pretty involved list of things to do.

Wow. How long do you get to prep?

For Vinyl I think I had 5 days. But I prepped myself for two weeks.

I took an extra week to myself, to go into Panavision, do all the research. Watch everything, take notes, talk with the pilot DIT, figure out what he was doing.

This is all so that when you have Show Runners, who worked on shows like House of Cards, all these big shows, asking you tough questions I had all information ready.

One of the reasons why I got hired, given that they didn’t even want a DIT on Vinyl, was that Reed said, ‘you need to bring Charlie onboard’. They had an interview with me and asked “Why should we have you on set?”

I said “Do you need me on set? I’m fine with not being there, if you don’t need a DIT? But when you’re shooting F55 and you have multiple cameras, up to three cameras at a time and you’re shooting 4K RAW… And I typically handle medium management, because with two cameras on all the time, you’re going to need a loader running around [swapping cards]…”

So there’s a bunch of different things to it, but it also comes down to personality. If you put off a good vibe people will want to be around you. That’s half the battle. Winning people over. ‘Oh, he’s a nice guy. He knows what he’s talking about and he’s not a jerk.’

What does a typical day look like for you on set, if such a thing exists?

It depends on whether it’s a stage day or do I have three location moves? Is it the same scene? Is it multiple scenes? Am I referencing things already shot or are we shooting the first part of a scene that’s going to change later?

And it all depends on the job too. For instance there’s a job I have coming up where it’s a 100 percent handheld, two camera shooting, with just a standard 709 look and the DP just wants me to make it ‘look good’. That’s it.

There’s no real colour choices or anything like that he just wants me to “Make it look 709, like how I would see it broadcasted” – Alright. Easy.

But in something like Vinyl we’re playing with colour a lot and the deLOG itself was very cyan looking. Pushing the highlights a little one colour, the shadows a different colour, that kind of thing.

So what’s in your cart? What’s your secret sauce for making sure it can handle anything?

I need to update the Cart list on the website because it’s completely different now. What’s up there is what I had for Vinyl.

- Inovativ Echo 36 DIT Cart

- Blackmagic Design UltraStudio 4K (latest Thunderbolt 3 Version)

- Blackmagic Design 20 x 20 Router

- Leader 5330 External Scopes

- Wacom Cintiq 13″ Display

- Retina Macbook Pro

- 2013 Mac Pro (Top Spec!)

- Mac Mini

- Tangent Element TK Colour Grading Panel

- (2) IS-Mini LUT boxes

- Magma 1T w/ H680 board

- Akitio PCIe Expansion Chasis

Software

- Pomfort Silverstack

- Pomfort Live Grade

- Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve

- Blackmagic Media Express

- Divergent Media Scopebox

Now I’m in a vertical cart scenario where everything’s compact, everything folds up.

With the Inovativ cart, the reason why I don’t like it as much is because on Vinyl we shot in a lot of places where we didn’t have elevators and I had to break my cart down a lot and take it upstairs and reassemble it.

And when you’re rushing for time and you barely get to the point where you’re plugging everything in and your DP wants to see a picture and you’re not ready, you can’t have that. You just need to be up and ready to go, as fast possible.

So I’ve changed my set up to the Vertical Cart so that everything’s compact, everything’s rack mounted everything’s built-in.

It’s on wheels and the centre of gravity is very reasonable. Now I don’t have to break anything down to go upstairs, and it only takes myself and one other person to go up or downstairs. I don’t have to get four people to help take my cart upstairs and I can leave my monitors on while I’m doing it. It’s all about ease of use.

I have a Blackmagic Design Ultrastudio 4K and the Blackmagic Design 20 by 20 router. Everything is run off of a Mac mini. I have a 16 terabyte RAID 0 that I use for my on set storage. Everything is either Thunderbolt 2 or USB 3 for connectivity when offloading.

I have everything set up so the card reader and the first shuttle drive are connected directly to the Mac Mini, so it’s the first in the bus, so there aren’t any bandwidth issues.

The thing that you have to realise when doing large transfers is that whatever is the slowest part of your chain will dictate how fast things go. So if all your hard drives are plugged directly into your computer but then your card reader is like the third in a chain on the USB hub, then your transfer speed is going to be dictated by your card reader.

So essentially I have everything plugged in directly as much as possible to my Mac Mini. It’s not the maxed out Mac Mini but it’s pretty it’s pretty darn close. I’ve had it for two years so I’m waiting for the new Mac Minis (if they’ll ever happen).

But when it comes down to it, [offload] checksums are dictated by CPU speed.

In your Vinyl set up you had the Retina Macbook Pro and a Mac Pro, but in your new set up it’s all running off the Mac Mini?

Yeah, so I’m only doing transfers and CDL workflow off my Mac Mini.

If I want to render or transcode, I have a switch where I’m hooked into my Mac Pro as a headless system via Gigabit Ethernet, and I can connect via a remote desktop directly from the network app on my on my Mac Mini and be able to remotely log into it and run transcodes on it. It’s pretty fast. It’s not as fast as if I was directly plugged in, but if I’m transcoding throughout the day I can keep up with it all day long.

I think people most people would expect you to need the beefiest system you can get?

For the cart I wanted a low profile. What can I build that’s as nimble as possible. I use my MacPro all the time for VR work, or colouring at home. [Side note Charlie is also building a colour suite at home!]

I like that you have DO NOT TOUCH THE SCREEN, on both the top and bottom of both screens! I have a friend who likes to say “If you touch the screen, I get to poke you in the eye.”

You’d be surprised how many people still touch the screen…. see what it says? It says, don’t touch it.

In terms of software why do you run Pomfort Silverstack and Live Grade?

The main thing that I absolutely love about Silverstack, and it’s the only software I will use, is the fact that I can go back at any point in time.

I’ve actually had to do this on the last season of Odd Mom Out. The DP asked me if I could remember in season one what our colour temperature was on some day where we shot off-speed stuff?

All I had to do was cue up my project from the shoot and go back to that season and find the specific day because everything is organised by episode day and shooting date.

So just being able to quickly go back and look through and see “Oh we were 4700 Kelvin not 5600. And we were shooting at 48. You were right were were off-speed.” – Just to have that ability is invaluable to me.

You don’t get that with Shotput Pro, it’s an offload software. If you accidentally close it, you don’t know what you’ve already off-loaded.

I’ve always been a proponent of organisation hierarchy and making sure that I have all the information at every point. So at any point in time I can reference the data.

Mainly because I’ve been, not almost almost fired because of it, but I’ve definitely had instances in which post-production has tried to blame things on me, saying that I didn’t do something when in fact that wasn’t the case. I was able to prove that the footage got sent through correctly because of my transfer logs.

That aspect alone, just being able to prove things with a time stamp, will make me never use any other software. I will only use Silverstack just for that.

How do you think Silverstack compares to other options like Shotput Pro?

You pay a premium for Silverstack [$600 annual subscription for Silverstack XT, $400 for Silverstack vs $100 purchase for Shotput Pro] but in my opinion it’s worth every penny just to have the hierarchy.

As long as you’re organised, it’s a no brainer for me. If I accidentally quit Shotput or my computer restarts or crashes or whatever, and I have to reboot the app, I still know what I already have [offloaded].

I’ll use Shotput on my other machines when I’m doing comedy when I might have eight cameras to offload at the same time. Then I have three machines set up, but I only have one Silverstack license and so I’ll put that on my main machine, but I’ll use Shotput on the others.

I like seeing everything up at the same time, just to know ‘OK’ it’s offloaded. Yes it’s there, yes I have the footage. I look on the hard-drive and see it’s there, but it also has a checkmark next to it, to say it’s offloaded.

But if you quit Shotput it disappears, so you don’t know what you’ve already done.

[Editors note – Shotput Pro version 6 has come along way in some of things Charlie mentions, such as the ability to pause and resume offloads. Check it out in detail here]

What’s been your most challenging moment as a DIT?

If there’s an issue on set you have to figure out how to handle it, without alerting everybody and making a huge issue out of it. What you say on set as the DIT can have a huge impact on a lot of people.

For example, when we had a pixel burn-in on one of our cameras on The Marvellous Mrs Maisel, I was talking with the second AC about it and I was like “We’ll just send the camera back get a new one.” You know, that’s one option.

The next thing I know I’m getting phone calls from Panavision asking

– “What’s all this about getting a new camera?”

– “What are you talking about?”

– “The producers just called me and said they heard you say that we need new cameras, because the sensor is bad.”

I was like “whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa.” I was just talking to the second AC about all that stuff. I was saying that was a suggestion!

In the end they called me to walk me through how to fix it on set, but it’s things like that, where you have to be careful about what you say because you can cause emergencies pretty quickly.

I read that you had to reassemble an Alexa in Puerto Rico?

That was on 22 Jump Street. Taking the Alexa apart was definitely one of the most stressful things I’ve done.

I was doing second unit for 22 Jump Street and we were in Puerto Rico. This is back when we’re shooting with the XT, when they just first came out three years ago. And nobody had XTs anywhere.

We had six cameras that we were shooting with. Three cameras for VFX, three cameras on second unit, and we used every single camera all the time. We didn’t have any backup bodies. And one of our cameras went down.

The camera wouldn’t start up because the cooling fan wasn’t working. So I essentially had to take the entire back of the ALEXA off and re-solder the fan start up. I think I called Cam Tech in L.A. and I said here’s the situation what do I do?

– “Well how proficient are you with soldering?”

-Pretty good.

-“All right, here’s what you have to do.”

So I had to fulfil the technician part of being a Digital Imaging Technician.

That’s probably the hardest thing I’ve done because if I screwed up, we were fucked because we didn’t have another camera. There were literally no cameras in the United States or Puerto Rico, or anywhere. But I got it to work.

Probably the thing I do more often than anything else, is pair Teradek receivers.

“Do you know how to pair this receiver?”

– Sure, why not.

Do you think the role of the DIT is going to become more and more crucial to modern film production?

I don’t think the DIT position is going anywhere. But it will evolve, especially with VR becoming a thing that more and more people are shooting. And so I think DITs are going to have to learn how to stitch on set.

I already own a couple of VR cameras, so I already know the whole process. Knowing how VR works and how to troubleshoot and prep VR cameras, doing all that kind of stuff, is going to be very valuable going forward.

Any final tips for all the budding DITs out there?

My tips for being a ‘well-liked DIT’ would be:

Always keep gum on the cart at all times.

And, if you have the space and the means to do so, make a mini-expresso maker for the cart too. You will make friends with a lot of people.

That and make friends with the Gaffer and Key Grip and you’ll be set.

Lettera agli amici

Decalogo del viandante (non del camminatore)

I VERI motivi per scegliere una fidanzata dell’Est

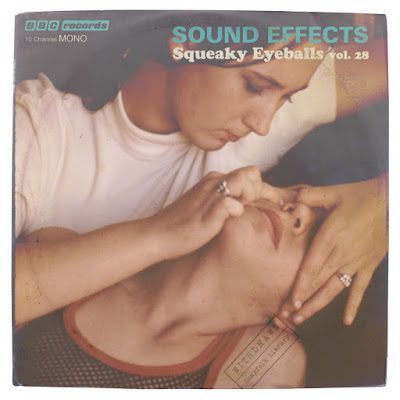

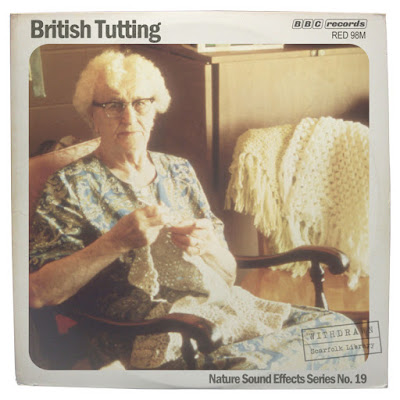

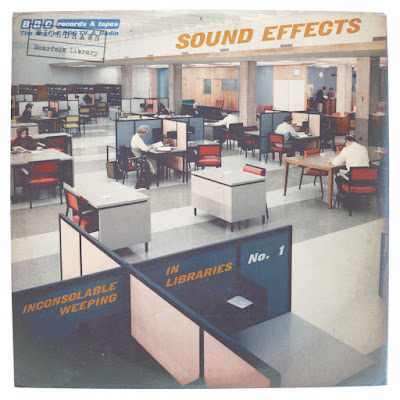

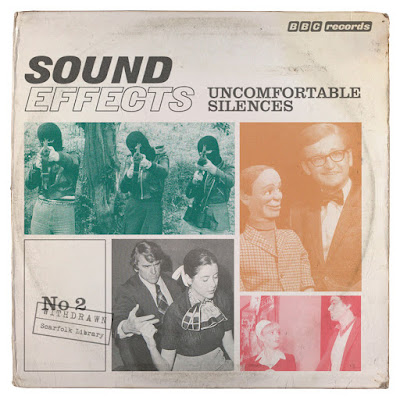

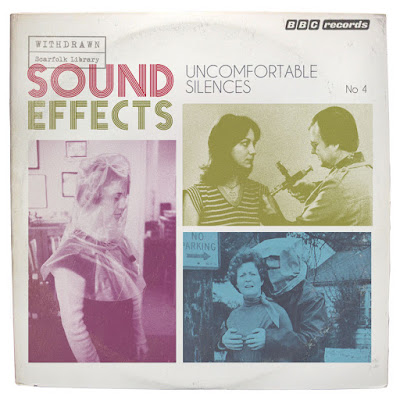

BBC Sound Effects Records (early 1970s)

Not all deceptions were successful. If a family was arrested they would be taken to their local police station where, while waiting to be interrogated by specialised officers, they might be played an album such as 'Uncomfortable Silences'.

An Eleven-Story-Tall Tree Hugger Sprouts on the Side of a Building in Chile

Image provided by Hecho en Casa

Italian artist Francesco Camillo Giogino, or Millo (previously here and here), has painted his latest sky-high mural in the heart of Chile. Never Give Up, created in his signature cartoonish style, features a female figure in the forefront clutching the trunk of a tree. The city behind the girl is black and white, causing the eyes to focus most clearly on a single green vine growing from the heart-shaped stump. The work, which aims to express the hope that Millo believes all hold in their hearts, was produced for Hecho En Casa festival this past month. You can see more of his nature-based and murals on his website, and on Facebook.

Image provided by Fotosaereas

Image provided by Fotosaereas

Image provided by Hecho en Casa

Image provided by Fernanda Landin

Image provided by Fernanda Landin

Image provided by Hecho en Casa

Image provided by Hecho en Casa

Fun Murals by Reskate Contain Hidden Glow-In-The-Dark Surprises

Here’s a fun series of murals from Spanish art and design studio Reskate Arts & Crafts, each containing a hidden second artwork that appears only at night. The glow-in-the-dark pieces utilize a photoluminescent paint that glows for up to 12 hours. You can see more of their work over on Behance. (via My Modern Met, Booooooom)

Adorable Pictures of Kids with Big Dogs

Russian photographer Andy Seliverstoff immortalizes adorables portraits staging children and their big dog friends. Beautiful tender and humorous breaks with a great complicity between animals and their little owners. Sceneries that seen to be from animated movies of our childhood.

Sounds from a Deserted Town: Dalmorton

The old Dalmorton Butchers

More than a 1-hour drive along a narrow dirt-road winding its way through river-valleys lined with eucalyptus trees sits the deserted township of Dalmorton. Once a gold-mining town boasting 13 pubs Dalmorton is now a small collection of abandoned buildings whose facades are barely surviving the elements and mindless actions of some visitors.

There under the unrelenting midday sun an old butchers shop and residence begged to be recorded …

Inside the butchers

The heat was oppressive inside the old butchers shop. I definitely didn’t want to spend much time there. Quickly scanning the room I saw some rusting metal rings from which meat once hung. They looked an ideal place to connect a contact microphone. The metal transported a definite thumping sound. A loose sheet of corrugated-iron roof was flapping in the barely existent breeze.

Next door an old residence baked in the sun. Although it had survived decades of abandonment visitors had at some stage kicked in the walls and windows. In a room to the left a tree branch scraped against a sheet of iron. My recording was cut short by the intense heat. The space or sparseness of the sounds caught in the recordings somehow reflected the slow pace of the empty township.

Boyd River

Walking around the remnants of the old township it is easy to forget that a a river runs through the valley. The sounds of life by the riverbanks were in direct contrast with the town. We entered its fresh water contemplating the place Dalmorton had once been. Questions were asked:

How had the land shaped those who once lived there? How could a town big enough to host 13 pubs all but disappear? What emotional attachments did residents have to Dalmorton in order to call it home? Did the local soundscape help form a connection to the land? What sounds had since been lost?

We floated in the water, no answers came …

Le illustrazioni noir di Alejandro García Restrepo

![]()

In questi giorni di convalescenza ho fatto dei sogni molto strani, quasi tutti erano in bianco e nero, come se consapevolmente sapevo che appartenevano ad un passato ormai lontano e sbiadito o forse semplicemente erano spezzoni di film di parecchi decenni fa. Poi mi sono imbattuta nelle opere dell’artista di cui vi parlo oggi e tutto mi è parso molto più chiaro. Erano sogni premonitori di un incontro che sarebbe avvenuto molto presto e oggi vi porto a scoprire il mondo di Alejandro García Restrepo

L’ospite di questo mercoledì vive a Medellín, in Colombia, dove ha frequentato l’Università di Antioquia e oggi è un bravissimo illustratore freelance che realizza i suoi disegni servendosi quasi esclusivamente della matita e di tanta creatività, tutto ciò che gli serve per regalarci storie inquietanti che scavano dentro l’anima e tengono svegli di notte. Non si trovano molte notizie sul suo conto ma i suoi lavori raccontano benissimo di lui e di cio’ che gli piace fare. Difatti, osservando da vicino le opere di Alejandro García Restrepo ci si rende conto di trovarsi ad avere a che fare con un abile artigiano dell’illustrazione che mi piacerebbe definire noir e la sua bravura si esprime nel suo modo di rappresentare un universo di piccoli ed infiniti dettagli che guardandoli nell’insieme vanno a comporre quelle strane figure che sono poi i suoi soggetti, uomini, donne e animali che capita di incontrare soltanto se si è portatori sani di amore per il grottesco e l’indefinibile, due elementi essenziali per chi come me è abituato a vedere il mondo circostante a testa in giù perché in questo modo tutto ci appare strano e la stranezza ci appaga e ci riempie la pancia di mostriciattoli.

Nelle sue composizioni quel gioco magico tra luce ed ombra, quel bianco e nero regale che ci porta in altre dimensioni spaziali e temporali, rivela la vera intenzione del suo artefice, ovvero costringerci a cercare la perfezione laddove l’imperfezione è l’essenza pura del suo dialogare con le sue creature mentre intanto la danza macabra della morte compie un circolo vizioso in quello spazio che ci separa dalla superficie.

I suoi personaggi così come le situazioni in cui vengono inseriti appaiono quasi privi di vita o forse immersi in un lungo sonno dal quale non chiedono di essere risvegliati, per tempo immemore viziati e appagati da una potente luce crepuscolare che li rende protagonisti di una mutazione corporea messa in atto dalla loro stessa decomposizione morale e la natura che regna vigile su ogni creatura compone e decompone a suo piacimento come un mescolatore di carte che guarda dritto negli occhi del suo avversario ed è consapevole di tenerlo in pugno: fanciulle con la testa di un uccello o forse un uccello travestito da fanciulla, non è importante per noi che assistiamo capire cosa si nasconde ma essere testimoni di una metamorfosi che mai si ripete.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

L'articolo Le illustrazioni noir di Alejandro García Restrepo sembra essere il primo su Organiconcrete.

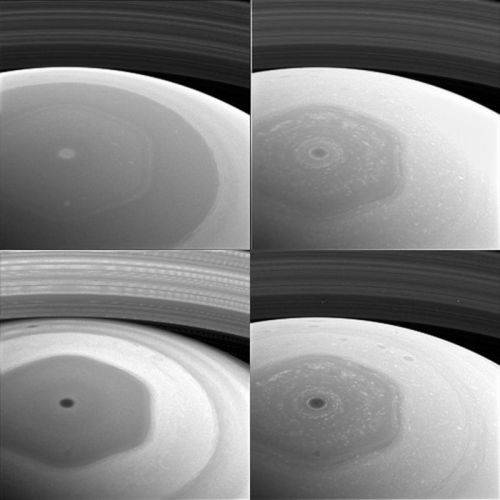

Astronomy Photos of the Year

Tommy Richardsen

Michael Jäeger

Melanie Thorne

Lee Cook

Rune Johan Engebø

Ivan Eder

Brad Goldpaint

Ivan Slade

10+ Genius People Who Fixed Broken Stuff Instead Of Throwing It Away

When A Truck Bumped This Russian Man’s Car, He Decided To “Fix” It In The Most Creative Way

Wall Got Busted From Water Damage, I Think It Looks Way Better Now

Fix Broken Flower Pots By Turning Them Into Diy Fairy Gardens

My Boyfriend Fell Down Our Stairs On Thanksgiving Day. Instead Of Fixing The Hole, We Got Creative

Repair Torn Couch With Lace

Creative Kid Draws On Wall, More Creative Mom Fixes It

Repair Broken Birdbath Using Recycled DVDs

Lego Pieces Are Used To Repair And Fill Holes In Broken Walls

Artist “Fixes” Broken Wood Furniture With Translucent Materials

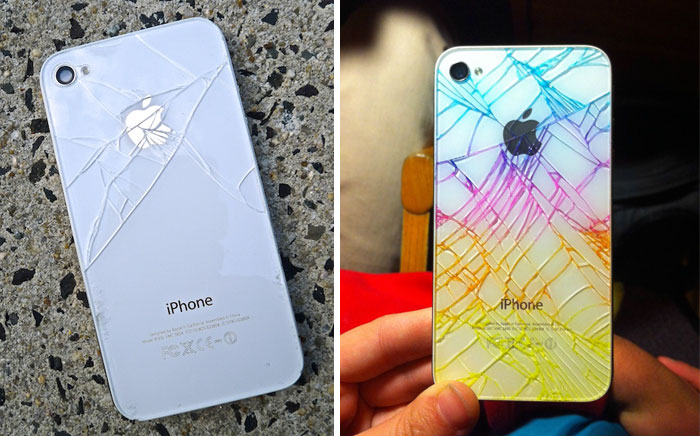

Cracked iPhone Back? Use Highlighters To “Pimp Yo’ Phone”

Anonymouse Are Opening Tiny Shops For Mice In Sweden

Anonymouse was fed up with the lack of shops for rodents, so they decided to open a couple of them at once. The 70×30 cm (about 25×12 inch) stores are located in Malmö, Sweden and they have wide menus that mice can choose their meals from.

Show Full Text

One of them is selling nuts and the other offers cheese. Besides the well-crafted interiors, there are posters about upcoming mice concerts and other events. The amount of detail that went into creating this street art installation is huge! The identities of Anonymouse are still unknown, but you can check their Instagram account for more information.

More info: Instagram

Feature Film Workflows

Feature Film Workflows

There is a certain feeling of trepidation that is experienced in the heart of every editor when they take on a project that is bigger and more complex than anything they’ve edited before. I can only assume that editing your first feature film feels that way.

So much to do, so much to get right from the get-go and so many people counting on you not messing it up. But as with anything, you just have to make a plan and jump in. In this post I’ve gathered together some fantastically detailed, some might say laboriously so, resources to aide any editor cutting their first feature film.

Before we get into the NLE specific workflows listed below, it’s worth pointing everyone in the direction of Assistant/Editor Evan Schiff’s blog, which has a huge list of very detailed posts on the jobs he tackles working on films like Mission Impossible and Star Trek Into Darkness. In this case I want to specifically point out his excellent guide to handling ‘Turnovers’, which is a must read for anyone wanting to be an assistant editor or editor.

Once you do this a few times it’ll become an easy and predictable task. The first time you do it, it may be a little intimidating, and you may have lots of questions that even the people you need to turn over to can’t answer. To help, always think of what your turnover recipients are going to do with your materials once you hand them off. What’s most useful for them? What would get in the way if it was done wrong? Putting yourself in their shoes can help you answer a lot of questions on your own.

It’s also worth read this post on editing features, partly from a craft perspective, and partly to hear a few more ‘stories’ from those who have gone before us.

Avid Feature Film Workflow

Being the ‘industry standard’ NLE for editing long form, multi-editor broadcast and feature film work, Avid Media Composer is the software you need to know if you want to edit at the highest levels of broadcast and film work today.

Editor Steve Hullfish has been conducting some excellent and exceptionally detailed interviews with feature film editors working in Avid, the best of which you can check out here and here. In an epic three-part series Steve broke down in ultra-fine detail his own feature film editing process when working in Avid Media Composer for the film War Room.

In the first part of the series Steve dissects the production process, his collaboration with DIT Ben Bailey and their RED Epic workflow. He also describes the exact steps given to the assistant editor to prep all the rushes in an Avid project. Steve also covers how he and director and co-editor Alex Kendrick worked together to hone the film from first assembly to final cut. If you were cutting a feature in Avid for the first time you could basically use this series as a guide to replicating the workflow, bit-for-bit, for yourself, it’s that detailed.

Originally, Ben and I discussed transcoding to DNxHD36, and I chose this as the resolution we’d work in. This seemed like a good choice, because it creates a file that looks quite good even though it is very “light-weight” and small, making it easy to store and easy to process by the computer. Ben transcoded the first several days at DNxHD36 before I decided that I wanted to have a higher quality video file for audience screenings without having to up-rez all of the RED files again just to do a higher quality screening before the final DI was created. After switching the subsequent footage to DNxHD115, Ben went back and re-transcoded all of the first few days to DNxHD115 as well. In the end we were able to just barely fit all of the transcoded DNxHD115 files on a single 4TB drive. When we started having additional media and renders, we moved to storing media on a RAID after we finished active production.

In Part 2, Steve details the process he undertook to deliver the film to Roush Media for it’s grade, VFX work and creation of theatrical deliverables. The grade was performed on the Nucoda grading system and it’s interesting to note that the final credits were created in Endcrawl. Again, Steve doesn’t hold back on the details and that’s what makes for such great reading!

While Roush has access to Resolve as well, he’s quite the advocate for the abilities of the Nucoda system. “Every tool is a great tool, explained Roush, “This film could have easily been graded in Resolve just as well. To me, personally, Nucoda is focused much more for the colorist than anything else out there. I grade on both here. There’s a lot of great workflow things in the Resolve system that can’t be beat and it’s a very powerful tool. The horsepower behind it can do a lot of powerful things, but the Nucoda to me has many, many brushes and many tools in my toolbox that have yet to appear in something like Resolve, so it allows me to grade faster with more control. It’s really the talent that matters, not ultimately the tools.

In Part 3 you can read all about the sound side of things and Steve covers his audio editing process and turning over to the sound department for the sound design and final mix. Articles like these are such a valuable resources and it’s fantastic that Steve has put so much time into sharing his experiences.

With my deliverables to the sound team ready, Nick Palladino took over once he received the hard drive with the audio files. Nick worked on a Pro Tools HD system with a Blackmagic card to feed video to the projector.

“We start with the AAF of the locked picture.” Nick explains, “I’ve done the last four films with the Kendrick Brothers and over the last ten years the digital technology has really changed. We start out by going though all of the dialogue tracks and we pick between the wireless lavs, the booms and any ADR and we make a smooth dialogue track, where it’s all been de-noised. Then we come back and put all of the sound effects in and all the backgrounds, all the footsteps. The music was then delivered to us by composer Paul Mills. We start with the temp music, which is what (the editors) used during editing, and we replace those tracks with the final score.”

It’s interesting to note that Steve considered Premiere for War Room, and is actually cutting on his next project in it.

War Room Feature Film Workflow Part 1 | War Room Feature Film Workflow Part 2 | War Room Feature Film Workflow Part 3

Premiere Pro Feature Film Workflow

David Fincher’s Gone Girl was the first film to really push Premiere Pro into the spotlight as a Hollywood feature ready NLE. Not that it wasn’t ready, you can cut a feature on iMovie if you want, but Fincher is Fincher and that gets people talking. It’s interesting to note that Walter Murch has been editing in Premiere and the Coen Brother’s next film Hail Caesar! was also cut on it.

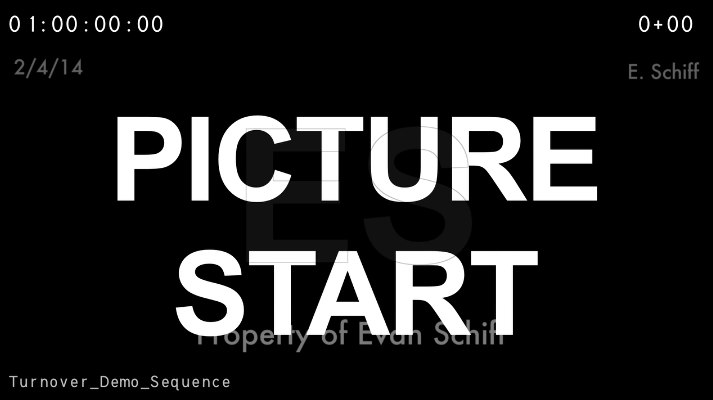

In terms of learning more about a Premiere Pro feature film workflow, first of all I would highly recommend checking out Vashi Nedomansky’s Adobe Max 2015 presentation on The Life of a Hollywood Editor, in which he talks through his experience as an editor in Hollywood, as well as his Premiere Pro workflow for cutting films like Sharknado 2.

Next I would recommend pouring over this exhaustively comprehensive blog post from Vashi, on his five year post-production labour of love on his own feature film The Grind. The post is packed with excellent tips and tricks that Vashi has perfected over the hundreds of hours he’s spent in the editing chair. A must read for any wisdom hungry editor!

All my footage and audio started inside Premiere Pro and using Dynamic Link would connect me to After Effects. Tight integration with Audition and Photoshop sweeten the deal and now I have Direct Link to Speedgrade. Like the center of a wheel, Premiere Pro is the hub and the spokes reach out to all the other software. There would be no more transcoding or exporting stand alone quicktime files. There would be no more temp folders holding files that would be rewritten daily and forgotten…only to take up space and confuse my already overflowing coconut. No more time wasted rendering out AE comps, importing and swapping out previous versions. No more brain-sapping, tedious and repetitive clicking and waiting to update my current cut.

I chose to cut on Premiere Pro CC for several reasons. Speed, Stability and No Rendering. The average Asylum film project has 6 layers of video and up to 20 layers of audio during editorial. This includes layers for footage, VFX slugs, ADR slugs, Temp VFX shots and more. Each on its own layer, each formatted a certain to keep consistency throughout the shared project.

For a detailed look at editing the cult hit in just six weeks, we turn once again to the fabulous folks at Pro Video Coalition (where Steve Hullfish blogs) but this time it’s editor Scott Simmons who interviews Vashi on his Premiere Pro workflow, which is coming from an FCP7 ecosystem.

I chose to have the entire timeline of the 85 minute film in one timeline. The Premiere Pro CC project had imported and was accessing all 40 hours of raw footage. I had no sluggishness in my one giant timeline and anyone who says Premiere Pro CC can’t handle feature length projects is sadly mistaken. I’ve cut my last 4 features in Premiere Pro CC and all of them were single timelines with footage counts of 30–150 hours. No show stopping issues on my end. Most notably, for the first time in many projects…I had no crashes or “Premiere Pro experienced a serious problem” in the 6 week post run. Boom.

“Never hang on a reaction too long…” Zucker taught him. “If you milk it, it loses its funny,” Nedomansky explains. “You have to cut away at the right moment, see the reaction to the dialog or action and then come back for more of the original reaction. If you linger, it’s death.”

You can read even more about Sharknado 2 and pick up some fantastic comedy editing ‘rules’ in this PostPerspective interview with Vashi, which is also well worth a read for a few more workflow details. As a quick aside you can also read about the colour grading process for Sharknado 3, in this Post Perspective article too.

Nedomansky emphasizes that as an editor it’s imperative to watch all of the footage. “You can’t grab the first thing you see and say, ‘That’s good enough.’ There is no good enough. It has to be amazing. So I would build an act a day and Dropbox it to him — a 10-minute H264 is only about 115MB. He’d look at it overnight and in the morning give notes and I’d move forward to the next act. We’d ping pong back and forth like that for the next couple of weeks. It was a simple and effective workflow.

UPDATE

Here are a couple more goodies from Vashi on his editing process and philosophy in this video, and even more details, direct from Vashi, on cutting Sharknado 2 in this post.

FCPX Feature Film Workflow

If you’re still in any doubt that FCPX is a viable option for feature film work, then check out my previous post on the Focus making of, which extensively breaks down the process the post-team went through to edit and finish the film in FCPX.

In these recent FCP eXchange videos editor Marc Bach demonstrates some of his workflow techniques to save time, money and stress whilst working on an indie feature film, which is pretty engrossing viewing.

Assistant Editor Mike Matzdorff, who (literally) wrote the book on FCPX feature film workflows, talks through the process of handing over your work to the sound department. There’s a great amount of step by step detail in this seminar session. You can hear a lot more from Mike in the Focus making of post.