| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - cute - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | August 13th, 2013 | next | |

|

August 13th, 2013: Yesterday's comic about reincarnation got me a few emails saying "Hey if you like that idea you should check out Riverworld!" so if you liked that idea you should check out Riverworld! One year ago today: my other interests include how come this site is so bad at getting me dates – Ryan

| |||

Shared posts

history's greatest monster

WojitThis last thing is pretty much what I straight up believed when I was 11. I'm genuinely not sure how seriously I believed it.

Automated For Your Convenience

Wojit<3

My day

Guest post by Heather McNamara

10:00 a.m.: fiancee Lauren McNamara texts me at work that she will be doing some interviews on CNN today about Chelsea Manning, who came out this morning.

10:00:01 a.m.: I tell everyone within earshot that my famous awesome beautiful amazing brilliant genius girlfriend is going to be on television.

12:30 p.m.: Lunch time. I tell some other people. My friends hide faces/walk away embarrassed that I’m admitting out loud to people outside of our circle of trust that my girlfriend is trans.

1:00p.m.-3:00p.m.: television at office plays Chelsea Manning story on loop; news anchors asking “hard-hitting” questions like whether those poor taxpayers might have to pay for Chelsea’s medical care.

4:10 p.m.: at doctor’s office with sons. CNN plays on TV. Lauren, my children’s stepmom, comes on TV. Two people in the waiting room snort and laugh. I ask if they think transgender people are funny. They laugh and stare at their laps. One of them says “Yeah.” I reply “assholes.”

4:11 p.m.: CNN news anchor continually calls Chelsea “he” and “him” and postulates that Lauren, too, was “once a gay man.”

5:00 p.m.: Arrive home. Cousin’s wife on Facebook has posted a status about how horrifying it is that her daughter has to share a bathroom with “a confused boy” at school. No really. I am not making this up.

6:00 p.m.: I call my counselor for a session.

Heather McNamara writes about indie literature, politics, and civil rights at HeatherMcNamara.net.

(from Be an Interplanetary Spy 9: Ultraheroes, 1984)

(from Be an Interplanetary Spy 9: Ultraheroes, 1984)

Knightmare TV Show Remake | YouTube Geek Week

WojitOH DANG I loved this show.

|

British TV classic Knightmare has been resurrected to celebrate Geek Week! Filmed in the original Norwich studios with original cast and crew, and produced b...

|

From:

ashens

Views:

624190

21660

ratings

|

|

| Time: 26:34 | More in Entertainment |

"Babakiueria" A political mockumentary reversing the situation...

WojitAaaah I remember watching this in High School

"Babakiueria"

A political mockumentary reversing the situation in Australia, where blacks landed in a white culture and took over.

I did not know this existed until about 30 minutes ago.

On the Inhuman Drama of Pacific Rim

SPOILERS FOR PACIFIC RIM AND OTHER DEL TORO FILMS WHOOPS

A reading of Pacific Rim:

Right off I want to say that I enjoyed the movie while cringing and being hugely disappointed every single time a character said the word “bitch” or repeated the name of the main jaeger, “Gipsy Danger,” which is a huge ethnic slur toward Romani people. Everyone involved in the production should be ashamed of these things, and we should all speak up about them, especially because it didn’t matter at all. None of the language was integral to the plot or characterization; the people working in design, directorial, production, and screenwriting capacities should be ashamed about it. I’ve actually been looking for a post that goes deeper into this issue, but I’ve not found one yet; if you do, please let me know so I can put it into this post as further reading.

Beyond those issues of representation, which are both glaring and important, I want to talk about what Pacific Rim is doing as a film. Guillermo Del Toro almost exclusively makes films that carry explicit political messages within science fiction or fantasy contexts–Mimic is about the fundamental horrors of urban life, Hellboy II is a manifesto on social destiny and difference, and Pan’s Labyrinth personalizes the sacrifices and casualties of the Spanish Civil War. So when I say that I believe that Pacific Rim is political, I don’t just mean it in the way that I teach my film students: “Every film has a politics,” I tell them, “and part of our job in these classes is to parse what a film does, how it does it, and why it is doing anything at all.” Part of this is breaking my students of classical auteurist models of understanding art or communication in general; the idea that communication is transparent and that every media work carries the explicit intentions of an author (the favorite right now being Christopher Nolan) is very, very strong in the freshman mind.

This is death of the author 101 kind of stuff, but I think it is important to lay out this idea that films (or art in general) have lives outside of their creator so I can immediately turn around and say that this film is a profoundly personal Del Toro film. Where I said above that every film that Del Toro makes is political, what I really mean to say is that Del Toro’s politics are written in giant red block letters all over the screenwriting and directorial choices he makes.

While Mimic is certainly about urban life, it is also about what makes us human when the conditions around the very concept of “humanity” are altered. “What is a human?” haunts all of his films, even when the question is reduced to abstract questions of sameness and difference. For example, Blade II presents the vampire community and its unthinkable, mindless other that is nonetheless the perfect form of vampire. A quick flip of vampire and human brings us back to a familiar Del Toro question: are we, as a species, simply the aggregate of our worst qualities? Hellboy II certainly suggests it, with Hellboy finally taking Prince Nuada’s claim that humans will never accept a demon among them seriously. He quits the human world. The lights come up, we walk out of the theater. The enemy is beaten, but the outcome is bleak.

I’m not going to go into the trauma of political “winning” as it is presented in Pan’s Labyrinth.

In essence, Del Toro’s films are all ritournelles, finite loops that come back over and over again to the same point. They are all concerning the same anxieties about what it means to be included in the category of human. He is also concerned about the limit of that category, by which I mean that he is interested in these inclusions and exclusions as well as the pure accidental nature of the human. There is a reason that he keeps attempting to adapt Lovecraft–for Del Toro, humans are weak, finite beings at the hands of an indifferent universe. When the Angel of Death tells Hellboy that his existence comes at the cost of all of humanity, the lives of humans don’t really factor into the struggle. In Blade II, humans are weak, corruptible, and barely present except in their capacity to be consumed by more powerful beings. Pan’s Labyrinth features a fantastical world in which humans are merely bit players in a fantastical drama played out by opaque and ancient beings.

It is in this capacity that I want to talk about Pacific Rim. It is a continuation of Del Toro’s general philosophy of the human condition, but it is also an evolution of the movements he was clearly making in Pan’s Labyrinth. The difference is that Pacific Rim isn’t a fantastical drama; it is an inhuman one.

The immediate objection that comes to mind, I’m sure, is that Pacific Rim IS ALL ABOUT HUMANS. It trades on simplistic tropes borrowed from anime filtered through a Hollywood summer blockbuster machine, which means that we get lots of people saying literal nonsense about digital vs analog giant robots while intoning each other’s super ridiculous names and having very serious emotional looks all the time. It hammers content atom-thin and papers over the film’s central concept.

The central concept is giant robots punching giant monsters.

It makes a lot of sense that the movie can be literally nonsensical at points because the point of the film, or at least the point of access that it is presenting the audience with, isn’t based on your enjoyment of the plot. I thought that what little there was was enjoyable–the narratives of loss and fear of loss that powered every non-comedy character worked well enough that I didn’t immediately recoil. It kept me in the movie, I was minimally invested, and it chained together robot and monster fights.

Despite the fact that the camera lingers and the plot meanders around the human characters, it isn’t really about them. They’re all sketches of people at best. We often talk about movies or games with barebones plots that merely exist to chain together action pieces, and that is exactly how Pacific Rim works. More importantly, that is the strength and purpose of the film.

I think the standard reading is something like this: there are alien horrors in a parallel dimension who fight a proxy war with humanity via giant monsters. We also fight in this proxy war, but we have giant robots. The aliens control their monsters through a hivemind connection that makes them operate as giant puppets; the humans do the same. Therefore, the movie is about the struggle of the plucky human spirit against alien invaders, and that’s the end of it. Additionally, there’s a subplot where Charlie Day has to go the the middle of Hong Kong to ask Ron Perlman, a monster war profiteer, for a monster brain with which to fight back with. Ron Perlman is shown to be an evil capitalist who lives in billionaire luxury (he has an anti-kaiju bunker, after all) in the middle of the slums. He shows some hubris and is mean to Charlie Day, he gets violently eaten, and we’re satisfied. Big puppets fight big puppets, the credits roll, and a postcredits scene shows Ron Perlman is alive after he cuts his way out of the monster. He quips. We laugh. The lights come up.

Watch this short interview with Guillermo Del Toro. Listen to him talk about Godzilla.

What’s immediately apparent to me in this interview is that short of that one moment where he remarks on an actor, there’s no mention of people here. He presents Godzilla as a profound, existential film focused on war and destruction, but never as a film about the human relationships in the wake of Godzilla (of which there are plenty). Pacific Rim is for me like Godzilla is for Del Toro–it is about the inhuman drama playing out between huge nonsensical machines and (sometimes larger) mutating, organic monsters. It is about having a sense of wonder at these giant creatures that cannot make any sense to us. It is about being caught up in a flow of spectacle that is not merely spectacular but also profoundly political in that these monsters and robots have no regard for humans as a species.

Sure, the human controllers do–the trauma of the opening sequence is derived from two people in a giant machine caring for a few individual humans. But much like the Spanish Civil War in Pan’s Labyrinth, it is something that merely exists on the surface of things. It is a plot to keep us watching, to keep us from realizing the paralytic horror and nihilism behind the structure of the filmic world that we are seeing. The world of the faun in one that doesn’t need human beings, and actively takes glee in their temptation and murder (I’m thinking specifically of the monster who eats children.) The parallel universe geneticists of Pacific Rim drive the same point home: if you peek behind the curtain in this film and think about the structure of the universe we’ve been presented with, there’s something infinitely creepy about it.

We are not alone. More than that, we are not special.

I think it is easy to imagine Del Toro being allowed to run free and break with blockbuster sentiment and take the premise of the film to its horrible conclusion. The world goes dark. The exterminators come through. The jaegers fail one by one. The slow creep of nonexistence overrides everything, and as Charlie Day explained in the film, we deserve it. We made the world perfect for them. Why wouldn’t they come?

So it is an inhuman drama in that it isn’t about humans, not really. It is about the posthuman world, the world of climate change and oversaturated carbon, the world where the only politics possible is the politics of the impossibly complex and unexplainable robot that, despite not being explainable at all, nevertheless has political agency. It is a swarm of nations and capital and metal and nuclear energy. It is an assemblage made as explicit as possible. It smashes up against another assemblage, slightly more organic, but assembled and machinic nonetheless. What matters is how they smash. What matters is what pieces fall off.

What can a giant monster body do?

Despite the fact that my suspicions of Del Toro’s real Lovecraftian nihilism are not verified, I still find the end of Pacific Rim to be bleak. After all, the existential threat to the human species is eliminated. The world can finally repair and rebuild. The transnational efforts of the wall programs and the jaegers can be discontinued, and business can continue as usual. The fact that the closing scene of the film, the last bit of screen time, is devoted to the evil, selfish, violent businessman being birthed from the body of the prime antagonist of the film is profoundly bleak. This international cooperation is over. The desire to break across any number of identity lines in order to achieve something that had to be achieved is abandoned. We get a white man asking for his shoe.

There’s a part of me that wonders which outcome was worse: total extinction or business as usual?

Filed under: General Features Tagged: guillermo del toro, nonhumans, pacific rim, theory, violence

Love It Up: Hate Plus To Release Aug 19th

WojitThis post may help illustrate half the reason that I have opted to see Cara Ellison and Rhianna Pratchett have a chat rather than have dinner at Dinner.

“Christine Love!” I would say, breathlessly, as I caught up with the prolific visual novel writer on her morning jog (possibly?), “You’re releasing Hate Plus your sequel to the phenomenal visual novel Analogue: A Hate Story soon, and I’m so excited!” “Oh Cara,” she’d say, brushing pink fronds of hair from her face as she effortlessly kept pace, “I know you’re so very excited. Thank you for the nice coverage of my games on RPS, by the way, you are the best website, and also Cara, you are the best writer. Alec understood my games, but honestly, I feel like you understand me.” “Oh Christine!” I would say. “I do understand you! Your games are so intelligent and well-written and…” HEY. YOU. GET OUT OF MY DREAMS. This ain’t no eroge. (more…)

Dickadoodle

WojitNice

Dickadoodle is a drawing game that I made with my friend Colin Capurso for Molyjam Deux, inspired by the following Peter Molyneux quote:

“Some people leave artwork, some people do rude things, other people then turn those rude things into nice things.”

So, what is the game? Well, a webpage opens up and a crude, lewd, and rude image is presented. The player’s task is to turn the rude thing into something nice with the available drawing tools. The image is then submitted to a public gallery where everyone can vote on its niceness!

Well, in theory. With a social experiment like this, of course it didn’t quite go that way. A fair few rude images snuck into the gallery, but we expected this to happen (whenever we told someone about the self-curation, they would raise an eyebrow), and it wasn’t nearly as bad as we thought it would be. Most folk created delightful art out of the crude pics of dicks (and various other naughty parts of the human body). Here is only a tiny fraction:

That last one has to be my favourite. They turned something crude into something sweet and beautiful.

It was far more popular than we expected. It was the first game created for the jam to be tweeted by Peter Molydeux himself, and has since been featured in a few round-ups. Over seven hundred images were submitted the first day. Blimey!

Oh, I should also note that this DIY Pinup Girl was an inspiration. The iconic Australian children’s show, Mr. Squiggle, was also a major inspiration.

Also, shout out to Emilia for coming up with the name.

Why not draw something yourself? It’s amazing what you can do with a penis!

The Humanity of Private Manning, by Lauren McNamara

WojitInteresting anecdotal article if you care.

It’s been weeks since I testified at the court-martial of Private Bradley Manning, and I still don’t know how to explain to anyone what that experience was like. I don’t even know how to feel about what I saw there.

Everything seemed simple before, and now it’s really not. It used to be easy to take a bird’s-eye view of the entire situation. I saw it as some abstract network of people, events, morals, responsibilities, laws, consequences, past, future, the connections between them, and some process of justice or historical consensus that would resolve all this in favor of one definitive outcome or another. It was easy to talk about what Manning did, debate the ethical and legal character of his actions, and calmly contemplate what should happen next.

That was my attitude going into this – there were facts, they would eventually add up to an answer, and I didn’t need to give much thought to anything beyond that. For me, the facts were simple: I had spoken with Manning online for several months in 2009, after he took an interest in my fledgling YouTube channel, and long before his leaks of classified material. His defense team believed our conversations could show that Manning cared about his country and wanted to protect people, contrary to the government’s assertions that he had recklessly placed America and its troops at risk. And so I was called by the defense to testify about what Manning said to me: that he felt he had a great duty to people, and wanted to make sure everyone made it home to their families.

Flying out to Baltimore was disorienting; I hadn’t been apart from my fiancee and our kids for over a year, and now I was on my own in a city I’d never visited before. Still, I took it in stride and tried to think of it as something that was going to happen, something I’d get through no matter how it went, and then it would be over – the same things I would always tell myself before a dental appointment. As if this were no more than some temporary discomfort or inconvenience to my life. I drew on the same strategy I used when nervous about flying, or transitioning, or coming out to my family: pretending that all of this was completely normal to me. Of course, having to pretend meant that it very much was not, but I tried not to think about that.

“Miss McNamara?” Sgt. Valesko, clean-shaven and wearing a sports jersey, recognized me at the baggage claim and introduced himself. He carried my bags outside, where Sgt. Daley was waiting to drive me to my hotel. I joked about the fact that I was quite literally getting a ride in a black government van. As they showed me some landmarks around the area – Costco, Olive Garden, and a high-security prison – we all got to know each other. Daley told me about growing up in Shreveport, attending a superhero-themed wedding in Seattle, and shattering his wrist in a motorcycle accident; I showed him the thick five-inch surgical scar on my abdomen. They thought it was great. It was surprisingly easy to talk to them – they were very friendly, and it really put me at ease, even when I was still struggling to get a handle on everything that was happening.

I was scheduled to have a meeting with Manning’s defense the next day, before they began making their case on Monday. Sgt. Val – everyone called him that – picked me up from the hotel, as well as Capt. Barclay Keay, another witness for the defense. This was my first time at Fort Meade, and it was a subtly disturbing place to be. While there were some features that made it clear this was a very different world, such as entire lots full of giant beige fuel tanks and warnings of barriers that might erupt from beneath the roads, it took me a moment to realize why it felt so wrong. It wasn’t about what was there, but what was missing: variety. Nothing here was out of place.

Unlike the surrounding town outside the barbed-wire fence, there were no irregular trees or overgrown weeds or strangely curved roads. Vast expanses of empty, perfectly maintained grassy fields separated the base’s buildings, nearly all of which were faced in brownstone and looked like they were built in the 1950s or earlier. There were homes here like those in most suburbs, but even the higher-end “mansions,” which Sgt. Val pointed out were for generals and admirals, were absolutely identical and took up no more space than any other house. What looked like a Walmart was simply titled “COMMISSARY” in plain white letters across the side. A lone Burger King sat atop a hill; I almost expected the logo to read “FOOD.”

We soon arrived at the courthouse where the trial had been taking place, a small bland building that gave no indication it had become a site of any historic events. A series of makeshift hallways fashioned from white tents wrapped around the building, blocking any view of its entrances. Sgt. Val guided me and Keay through the maze both outside and inside the building, and we eventually reached the courtroom itself. No one else was there today, but we didn’t have to wait long before we were approached by Capt. Angel Overgaard of the prosecution, a small woman in a sweatshirt with her hair in a tight bun. I was surprised, as I had been rather specifically informed that this would be a meeting with the defense, and I still have to wonder if this was intended to catch us off-guard.

Overgaard chose to talk to me first, and led me to a small private room to discuss my testimony. Just as the defense had previously spoken with me to work out what I would be talking about at the trial, the prosecution now wanted to figure out what they should ask me during cross-examination. The content wasn’t much of a mystery: the only relevant evidence at hand was my online conversations with Manning, which had already been published in their entirety. But unlike the defense, who worked together with me to establish exactly which questions they would ask and how I would reply, the prosecution couldn’t be quite so open about this. As their goal would be to diminish the significance of my testimony, they needed to retain some element of surprise.

Her questions spanned a wide range of topics, and didn’t seem to suggest any larger picture of what approach the prosecution might take when cross-examining me. Starting with the basics – how Manning first contacted me, how he felt about his job as an intelligence analyst, and what his goals and ambitions were – she then moved on to various details of what we talked about. She asked me to explain what the Python programming language was, as well as information theory, the AES algorithm, “Slashda” (by which she meant Slashdot), and Reddit, which she pronounced “read-it.”

These seemed to me like things the prosecution could learn about from a brief session of Googling, and I suspected this much ignorance was a put-on so they could see how I would personally explain such things. I had a nervous sense that they specifically wanted to know what I would say about it, and I wondered how they intended to use all this. It became even more suspicious when she began asking me what WikiLeaks is, when I had first learned about it, what sort of content is on the site, which of their material I had read, and how I believed the organization functions.

As someone who had only visited the site a few times out of curiosity, and didn’t read very many of the cables simply because they were in all caps, I found it almost amusing that she thought I could explain the nature of WikiLeaks in any useful detail. Still, her tone was friendly throughout, even as she was not-so-subtly digging for any answers that could be turned to the prosecution’s advantage. She didn’t feel there was much more to talk about after that, and she led me back to the courtroom to explain how my testimony would proceed tomorrow. I would enter through a side door and walk down the center aisle, where another prosecutor would hand me a water bottle, and I would then approach the witness stand to be sworn in. The prosecution would be in front of me on the left, and the defense on the right.

Standing there in the nearly-empty courtroom where all of this was about to take place, I felt… nothing. None of it seemed to reflect any of the significance the entire situation had acquired. Yes, it was important, but everything around me made it clear that it was also just another trial. It was just a courtroom that would be used for many more cases in the future, a building where you could just as easily walk down another hallway and have no idea what was taking place in the next room, and a gathering of ordinary people with ordinary lives who were doing this as just another part of their jobs.

We get excited when we watch film teasers, but after we see the movie, we realize it was nothing like what we expected – it was just another movie. Having only heard about the trial from a distance, my expectations had grown so much that I failed to realize this was all still taking place in the same boring world the rest of us inhabit. Nothing about the reality of this seemed to do justice to the idea of it. Before leaving, I was directed to the government’s trial operations trailer, where two soldiers issued me a witness badge. My name was written on a whiteboard below several others. On the wall above their televisions, a black-and-white image of the Dos Equis guy read: “I don’t usually watch trials… but when I do, it’s not the ones I’m supposed to watch.”

Back at the hotel, I Skyped with my family, recounting the day’s events and making sure everything was okay at home. It was difficult to sign off for the night, and as soon as they were gone, the feeling of isolation grew to almost a physical presence. I left the TV on a random channel and tried to imagine I wasn’t alone. When the alarm went off at 5:30, I was nearly in a state of panic – it was still pitch black out, and it took me a moment to remember that I was in a hotel far away from home.

This time, Chief Joshua Ehresman joined us on the ride to Fort Meade. Tall, stocky and charismatic, his Southern accent and broad grin made his tales of hard-partying hijinks seem like so much innocent fun. He asked if I was military or civilian, and insisted he had seen me somewhere before – perhaps because of my Army surplus purse. I suggested he might know me from the internet; he laughed and remarked that he needed to stay off the internet so as not to get himself into trouble.

At the entrance to the courthouse, we were ordered out of the van so it could be inspected by bomb-sniffing dogs. A crowd of a few dozen people had gathered behind a barricade at the very far end of the parking lot, holding signs and cheering loudly as we walked into the tents. Not knowing what else to do, I waved. “Who are they?” asked one of the soldiers. “They’re gonna free Bradley Manning,” smirked Ehresman. “Good luck,” I muttered bleakly. He thought this was hilarious.

The witness trailer where we waited was roomy and colder than a movie theater – a welcome relief from the unexpected Maryland heat. Two private rooms were at either end, with a common area between them, lined with small drab waiting-room chairs and a few syrupy orange leather lounge chairs. A coffee machine was perched on a table, and an unused television sat in the corner, with DVDs like Independence Day stacked on top of it.

Today, there were six of us lined up for the defense: Chief Ehresman, Capt. Keay, Sgt. David Sadtler, Capt. Steven Lim, Col. Morris Davis, and myself. With the exception of myself and Col. Davis – the former Chief Prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantanamo – they had all personally worked with Manning in some capacity while he was stationed in Iraq. Every one of them felt somewhat mystified as to why they had been called here. They admitted to knowing almost nothing about Manning himself, and believed they had little to offer in the way of evidence other than simple facts such as “I saw a window open on his computer.” Once I told them of my conversations with him, they concluded that out of everyone present, I had spoken with him the most extensively.

Throughout the morning, we all refreshed our phones for updates on Twitter from Alexa O’Brien, Kevin Gosztola, Ed Pilkington and Nathan Fuller. Their tweets provided more valuable inside information on the minute-to-minute happenings than anything the Army told us that day. It was through them that we learned why the trial, scheduled to begin at 8:30 AM, had not even begun two hours later: the video and audio feed to the press room was nonfunctional, and they couldn’t proceed until it was fixed.

Eventually, Ehresman was escorted to the courtroom. We refreshed our phones obsessively as we waited for the next update from Alexa on what questions were being asked and who would be called next. At one point, my old name was tweeted by a reporter, and all of them saw it. “Oh great, now the whole world knows,” I joked. “Why do they even think that matters?” lamented Sadtler, a detached and ironic young man who was much less uptight and formal than everyone else present.

For such a significant occasion, the atmosphere in the trailer was starkly mundane. Even when waiting to testify at a historic trial, waiting in a small room all day gets old fast. Most of them talked to each other in acronyms I couldn’t understand, stopping only to inquire about the My Little Pony sticker on my phone. Keay had brought bananas, almonds and berries for us to snack on, and we all remarked on what a brilliant invention the Keurig machine was. Sadtler discussed the US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan with Lim, who soberly contended that our actions were regrettable but necessary. Sadtler, who seemed to be of a more liberal bent, was skeptical.

At one point, Manning’s lead attorney, David Coombs, stopped in to say hello to us. Taking Lim into a private room, we overheard them discussing several very obvious points about .EXE files – executable software. To Sadtler and I, who had both been raised online, it was highly amusing to hear people try to work out exactly what an .EXE is. We joked that it “hacks the Gibson.” By lunch, only Ehresman and Sadtler had testified. Col. Davis and I ate at the catering tent, where prosecutor Maj. Ashden Fein was angrily berating another soldier for the problems with the media feed that morning. He seemed very high-strung and truly upset about this. I wondered if he would be similarly on edge in court.

With the press room issues cleared up, everyone’s testimony proceeded much more rapidly during the afternoon session. Eventually, Col. Davis and I were the only ones left waiting in the trailer. While my phone’s battery had died hours before, he helpfully kept me updated on what was happening just a few hallways away from us, and we passed the time talking about what we had each been working on recently.

I learned that he had received a Hugh Hefner First Amendment Award along with Jessica Ahlquist, a young woman who successfully fought to remove an unconstitutional Christian prayer display from her public school, and whom I had spoken alongside at a secular rally last year. He shared his thoughts about Guantanamo and the injustice of extraordinary renditions, as well as his stance on the Manning trial: that Manning’s actions were wrong, but so was the government’s pursuit of an “aiding the enemy” charge that could carry a life sentence. I found this to be a refreshingly elegant perspective – an all-too-rare acknowledgment that perhaps both sides could be right, and wrong.

At around 4:30 PM, a soldier finally came to escort me to the courtroom. We waited outside the doorway as dozens of spectators were led out of the building. Many of them looked me up and down as they passed – I couldn’t tell whether they were scrutinizing my face, or my pink hair, or if they just wanted to get some sense of what was going to happen next at the trial. An older woman asked if I enjoyed the clapping that morning. “Yes,” I answered unsteadily, not sure if I was allowed to say anything to them.

I was led through the hallways until I was standing outside the closed doors of the courtroom. Two soldiers, both women, stood ready to open them as soon as I was called in. I chatted with them about insignificant things like the weather, and once again, I shared my well-worn explanation for why I was there: that Manning and I had talked several times, and the defense now felt that the record of his statements could be useful in countering the charges against him. We stood there in silence for some time, until the doors were opened.

I walked in, and saw that the benches were packed with spectators. Every single person in the room was looking at me. It was completely silent; my ears began ringing, and my heart raced. I got the sense that everything was somehow frozen in time – walking past the benches and up to the stand was like a dream where everything is too slow, and you know you have to try and get away from something terrible, but you can’t. Fein handed me a water bottle. I didn’t know why I was panicking. I had told myself this was just something I’d have to do, like any other routine thing, and then it would be over.

As I turned to face the room, my heartbeat pounded in my ears even worse than before, and I could barely speak when Overgaard swore me in. My mouth went dry and my throat tightened. In front of me, at the defense table, I saw Bradley Manning for the first time. However underwhelming and unimportant everything seemed in the empty courtroom before, however much I’d thought the reality of the situation fell short of the idea, the reality had surely caught up and exceeded whatever I expected to feel. I could sense the energies of some pivotal moment of history turning to focus themselves on me, and the weight of it was almost unbearable.

Coombs asked me what my name had been before I changed it, the name I still had in 2009 when Manning spoke with me. In front of this room of strangers and the entire world listening outside, I spoke a man’s name in little more than a wavering croak. He then asked why I changed my name. I thought it was obvious – did I really need to explain it? What came out was something like this: “I’m a woman, and I wanted my name to reflect that.” A young woman in an aisle seat seemed to be vaguely impressed.

I kept looking over toward Manning. I wanted, more than anything, to see some indication that he was okay – that he was still alive in there, that he hadn’t been destroyed by all this. He only stared straight ahead at the ceiling-mounted monitor, with no visible emotion on his face. I tried desperately to make my pulse stop pounding, but seeing him that way just added to what I began to realize was a growing despair.

Coombs continued, asking me basic factual questions about my history with Manning: how he found me (he was a fan of my videos), how long we talked for (six months), and why he chose to speak to me (he felt I had a similar outlook on political and religious matters). I answered as best I could, but I couldn’t get my thoughts in order, and the words were slow and jumbled. My mind seemed mostly occupied with processing something much larger.

Most of the questions seemed redundant, given that the chat logs were the entirety of our interactions. I didn’t understand how my opinions could have any value here – even if all they had to go on was the text of our conversations, that was all I had to go on, too. I had no unique insight beyond anyone else. I didn’t know why I was there.

Coombs finally moved to introduce the 39 pages of logs as evidence, and Overgaard immediately objected, claiming that they were hearsay. There was a brief back-and-forth over the precise legal details, and Judge Denise Lind called a 20-minute recess so that copies could be made of our conversations and she could review them. The spectators once again shuffled out, along with the prosecution team. The only ones who remained in the courtroom were myself, Manning, his attorneys, and his guards – two large plainclothes men with earpieces who stayed within a few feet of him at all times.

During the recess, Coombs took me aside to the unoccupied jury panel, where we went over the specific portions of the logs that he would ask me about. I had looked over these excerpts with him many times before, but now I couldn’t concentrate. Instead, my eyes were drawn to Manning, well aware that I might not see him again for a very long time, if ever. It was a relief to see that he was happily talking and joking with the attorneys and even the guards. Some part of him had survived through all this.

After Coombs left, I sat alone at the jury panel. Seeing Manning look in my direction, I waved weakly at him. He nodded at me.

Once the court reconvened, Coombs simply had me read selections from the logs. For the first time since I walked into the courtroom, I began to relax, certain that the confident Manning I once knew was still there with me. My voice seemed to return, and I read his words aloud.

“With my current position… I can apply what I learn to provide more information to my officers and commanders and hopefully save lives. …I’m more concerned about making sure that everyone, soldiers, Marines, contractors, even the local nationals, get home to their families. …I place value on people first.”

During the cross-examination, Overgaard’s questions had little to do with anything we discussed at our meeting, and she likewise asked me to read certain portions of our conversations. I could tell that she had assembled these excerpts to paint a more damaging picture of Manning.

She cited conversations where he expressed a nuanced outlook on the methods and goals of terrorists, criticized malfunctioning military computer systems that made his job difficult, and sent me a link to his newly-developed unit “incident tracker” that was hosted on his personal site – a link which contained no actual content, though Overgaard did not allow me to clarify this. By now, any trace of nervousness had dissipated. Instead, I was merely incredibly offended. Even though these were his words and not my own, I felt a deep indignity at being forced to speak what they were intent on using against him.

I was excused from the trial and strode out of the courtroom, with a nod to Bradley Manning and to the spectators. Some nodded in reply.

Bradley Manning is a human being, and that simple fact made itself so apparent that day, everything else ceased to matter. Looking at him, there was no way I could continue to see the situation as being about anything other than this one person and what they had gone through. Yes, there are issues of morals and laws and risks and harms that must be weighed up. I know this. I’ve said those words before. But none of it was important now.

It’s not that I believe Bradley’s actions were right. It’s that I don’t even care anymore, and people’s shallow words of support or denouncement mean nothing to me. They have no idea what he’s going through – none of us do. To me, this isn’t about making him a figurehead for some movement, or a subject of our little arguments over abstractions, or a symbol of everything right or wrong with the world. It’s not about my opinion or the reporters who ask me for it. It’s not about the meaningless words I’ve written on needing to deter soldiers from leaking mass amounts of classified documents, something I foolishly believed to be the most relevant response to this situation. It’s not about finding an elegant answer to a moral puzzle or coming up with yet more rational arguments to support whatever I happen to be feeling at the moment.

It’s not about what we think of Manning’s opinion of Guantanamo or the Army or their broken computers, it’s not about soldiers joking around and admiring a coffee machine in a trailer, it’s not about whether the trial lived up to our expectations. It’s not about us.

For the past three weeks, my life hasn’t been about anything other than the fact that Bradley Manning is sitting in a cage right now while the rest of the world gets to walk away and move on. And I don’t think I can move on.

It’s easy to forget that at the center of all this furor is one person – a person like us, who thinks like us and feels like us and hurts like us. Having seen Manning in that room, I can never forget this. Before, he was just a name to me, one of thousands that have crossed my screen. But Bradley Manning is not, and never will be, just a name.

In that room, I saw a person who was in more trouble than I had ever seen another person be in, someone who had suffered and was still suffering the full wrath of an enraged, unforgiving American government. And that scared me, and I wanted to help him, to do anything I could to get him out of there, and I couldn’t. And that hurts beyond any words.

Nothing I can possibly say about this will be able to give him what he needs and deserves. What he needs isn’t as sterile as some right answer that accords with ideals of freedom or justice or any other lofty concept that we speak about in preachy tones. He is a human being and what he needs from the rest of us is humanity. The only meaningful question is how we can live with ourselves while this is happening to a person.

What I felt then and still feel now is a kind of guilt, unreasonable as it may be. No, I had no way of knowing what Manning was going to do – but if I had kept talking to him, everything could have happened so differently. I don’t know how I, still an immature child even at 21, would have reacted if he had spoken to me about his intentions rather than Adrian Lamo.

I could never tell how serious he was being when he talked about his work, and there’s a good chance I would have unwisely leapt at the opportunity to see or touch or transfer any classified material he had been gathering behind the scenes. For such an excited, youthful lapse in judgment, I could have been dragged into this unexpected and unimaginable hell right alongside him. Or, if I were more attentive to the consequences of what he was planning, I might have tried to discourage him from doing something so reckless. I might have been able to prevent this.

And if there was something else going on in his life that was distressing to him, maybe I could have helped him with that, too. What I didn’t reveal at the trial was that Manning opened up to me in part because we were both gay men. That’s not who I am anymore, and by the time Manning contacted Lamo, there were clear signs that he too was considering transitioning – signs that any other trans person would see as indicative of someone who was so far into this, they weren’t likely to turn back.

I’ve talked about Manning as male, because there’s been nothing but silence and denial on this front from his family and his attorneys, and I simply don’t know how else to refer to him. But I do know what happens when you take one of us and lock us away for most of our early twenties, unable to access treatments like those he was seeking. It horrifies me, and it should horrify anyone else who truly understands what it means to be held hostage by our own bodies.

Somewhere, in some other universe, I might have been able to stop all of this – or I might have ended up in a cell, too. But now there’s the unbearable discrepancy, the miserable and unyielding knowledge that I would get to walk out of that courtroom as a free person and he wouldn’t, that he’s locked in a cage and I’m not, that I got to transition and he didn’t.

The next day, Sgt. Daley drove me back to the airport. I stared blankly as he asked if I had seen any movies during my stay – he recommended The Lone Ranger. “That horse stole the show!” he effused. I tried to laugh, and I couldn’t.

–

I’d like to thank Heather, Lydia, Amy, Patience, and all my supportive friends who’ve offered their kindness and a listening ear. Thank you for helping me through this.

"Untrust Us" Crystal Castles covered by Capital Children's Choir

Wojit(Xiu Xiu just tweeted this)

It's nice.

|

We wanted to cover Crystal Castles because we liked the idea of replacing their synths and percussion using only our voices and hands. Recorded at Abbey Road...

|

From:

capitalchoir

Views:

981980

16155

ratings

|

|

| Time: 03:35 | More in Music |

WRRRMZ! (Ian Snyder)

WojitCuuuute

or hey, if you want to play the game with glitched colors and text, SECRET EASTER EGG LINK – [Author's Tweet]

Business Time: Ultrabusiness Tycoon III

WojitOld Reader, back just in time for me to share the heck out of this!

(Actually the game came out days ago but I only played it today and now I have sixteen thousand feelings and it is so damn beautiful.)

I wonder how many of you have played our Live Free Play Hard correspondent Porpentine‘s games. I’ve just finished playing her latest: Ultrabusiness Tycoon III, and as usual, I grinned at the jokes, smiled at the references, and was very moved by the end. Come with me now, on a journey through time and space… (more…)

David Bowie - Valentine's Day

WojitThere is significantly less going on in this video than the other recent ones but arrrgh Bowie so amazing goddaaaaaamn this album is great okay I'm okay now.

|

Album available now: http://smarturl.it/TheNextDayDLX Directors: Indrani and Markus Klinko Executive Producers: Indrani, Markus Klinko, GK Reid Production De...

|

From:

DavidBowieVEVO

Views:

2094701

21314

ratings

|

|

| Time: 03:09 | More in Music |

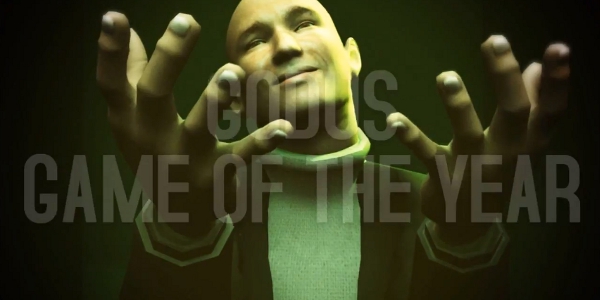

Now With Real Molyneux Quotes: Molyjam 2 This Weekend

Wojit"You know what this industry's like, as soon as there is the scent of death, everyone jumps on the hearse."

Weeeeee

Game jams are majestic creatures of unbridled creativity that come in all shapes and sizes, but the original Molyjam might just have been one of the best. That, however, left Molyjam’s organizers in a bit of a pickle: How do you top ideas born of an absurdly clever Peter Molyneux parody Twitter account? But then – presumably while sitting under an acorn tree that had taught countless passersby how to love – they were struck with inspiration: why not just go back to the original source? So instead of asking “What would Molydeux,” this year’s jam actually focuses on good old Molyneux himself. His quotes, his promises, your games.

Season 3, Episode 1: The Blessing Way

This episode is busy! I had to leave out so many things, like Scully finding a microchip implanted under her skin, or Scully and Frohike bonding over beers, which I found extremely charming.

Want the original art for this strip?

Creating without power Narratives of madness face a particular challenge not present in many...

WojitSupes interesting.

Creating without power

Narratives of madness face a particular challenge not present in many others — the anti-narrational character of the experience. The experience of madness is, as stated by Brendan Stone (2004), “characterized variously by fragmentation, amorphousness, entropy, chaos, silence, senselessness” (p. 18). Traditional narrative form seeks to make sense of the senseless, creating order of the fragmentation and giving voice to what was or still is silent. When shaped into the narrative form, madness loses its very character and by “assuming an appearance of reason” becomes “contrary to itself” (Foucault, 1988, p. 107). How then does the narrator of madness put language to the “unsayability” of madness without subsuming the experience into reason?

In his work on narratives of madness, Stone takes up the question of this challenge, applying philosopher Sarah Kofman’s (1998) concept of “writing without power” to the narration of mental distress. Stone interprets writing/speaking without power as speech which “does not attempt to master the traumatic event; does not attempt to make that which is aporetic — intrinsically full of doubt — into something can be fully known or understood” (2004, p. 23). Writing without power is writing which respects the alterity of both the writer and the experience while “narrative mastery” seeks to destroy it through codification, delimitation, and explanation. These actions may give the author (and the reader) a sense of momentary security and power over the experience through making it known, but through the narrative reshaping the experience is changed and may no longer be recognizable.

Systems and alterity

One of the challenges in creating a game about depression is the structure inherent to games. Games are rule bound. Choices in play lead to consequences — points, opening new passages, gaining access to new abilities, etc. Games often bound chaos in a world of reason making it no longer chaotic. Learn the rhythm, learn the rules, find the method in the created madness.

The game Depression Quest attempts to subvert the element of choice by showing how this choice is limited by the experience of depression. Would-be options are crossed out, no longer available to us as reader-players. We are constrained by the experience the game is attempting to depict.

Yet, the game is still familiar as a game in the interactive fiction genre. This was an intentional choice made by the developers. At the bottom of each passage are three status bars (depression level, engagement with therapy, and medication use) with a flickering static grey background.

According to one of the game’s developers, Zoë Quinn, they “wanted to show players exactly how we were constricting them based on their current depression levels, which reacted to the decisions they made in relation to their illness (usually if they retreated from the world and from seeking help vs if they reached out).” The effects of choices change both the status bars and the options available in the future.

Quinn argues that this reflects the “systemic” nature of depression — take medication, see improvement; withdraw from people, decline. Yet this largely reflects an outside view of depression rather than the turmoil, disorder, and/or emptiness of the experience itself. Throughout the game the reader-player is faced with choices to seek therapy, go on or off medication, or withdraw, drink, close down. It is as though the game is attempting to teach the reader-player to learn to recognize symptoms and seek “appropriate” treatment. For many player-readers this may have been needed, helpful, but it is accomplished through the use of narrative mastery, the creation of a clear system, making the aporetic clearly defined.

In one passage the reader-player must make the decision of whether to stay on medication or go off because they have experienced “improvements” in their mood: “’Maybe it’s time to stop taking these,” you think, “I seem to not really need them anymore’" (emphasis original). Yet the choice is a false one. Choose to stay on the medication and the reader-player learns “that this is a common train of thought that people who have begun using medication to help them manage their depression experience, and that you’ve managed to dodge a bullet because it generally ends poorly.” Make the choice to stop taking medication and,

the familiar pit of despair in the back of your mind reopens and reaches out to pull you back in… All of this feels much worse than the side effects of the medication, so you resume taking it… You’ll not make this mistake again.

This particular passage along with repeated use of the language of “negative feedback loops,” a phrase common in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), gives the feeling that the authors are at times writing from the medicalized perspective, using language of diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment.

Stone (2008) argues that this type of language is “a discursive mode sanctioned by authority” (p. 71). It is a translation of the experience into a language which seeks to know and through knowledge control the experience. The painful, distressed, confusing, panicked thoughts are simply “negative feedback loops.” Learn to recognize them as such and you can learn how to control them. Stone is concerned with the potential harm to the individual employing such medicalized discourse, stating:

If I introject this discourse what emerges is a kind of death-in-life. For now that I have a label to attach to my distress I am no longer an individual whose distress is refined and defined by my history, my imagination, my oppression, my singularity; rather I have become an instance in a broad category. Moreover the category is there to define something useless, something without value, something to be moved through as quickly as possible so that I can return to ‘living.’

By claiming depression has a clear system, and designing a system around it in which players are encouraged to make the “correct” choices — ones which lower depression levels in the status bar— Depression Quest treats the experience of depression as “something to be moved through as quickly as possible” and successfully defines the experience as something without value to the person experiencing it. While, I would hazard a guess that this is far from the intention of the creators, this is what the language of illness does, and this is the language they employ.

The choice to use this type of language is not without reasons. When in a state of vulnerability the language of authority can be tempting as it is both encouraged by those within the mental health system and can provide the individual employing it with emotional and intellectual distance from the experience. Creating narratives of experiences of madness can feel risky as it involves a “renegotiating of the spaces of the self in which suffering is, or was, experienced” (Stone, 2004, p. 20). Creating order and reason out of disorder and pain can feel empowering at the same time that it disavows aspects of self. It is not uncommon for autopathographers to slip in and out of this medicalized discourse. It can be a safe haven and a defense against a judging self and imagined others. Mental anguish is still largely misunderstood and stigmatized. Falling back on language which carries the weight of professional authority can have a mitigating effect — don’t judge me, it was just a chemical imbalance.

But does the use of this discourse aid in ending lessening stigma? The belief that promoting the concept of “brain disease” as a way of viewing mental distress and difference would reduce stigma is common. It has been promoted by mental health providers, drug companies, and groups like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) (Watters, 2010). And it is promoted by Depression Quest and the organization iFred to whom a portion of the game’s profits is donated. None of this is meant to suggest that Depression Quest should not have been made or is without value, but rather that it is one example in a much larger trend of promoting biomedical explanations as a way of reducing stigma. iFred takes this one step further calling for a “rebranding” of depression, combining both medical and business discourse in a goal of ending stigma. But with this discourse human suffering is masked over in the brand’s bright yellows and sunflowers.

According to Ethan Watters (2010) this framing of distress may lead to the opposite of the intended effect. During the same period that there has been an increase in the biomedical understanding of mental distress, there has been an increase in perception of the dangerousness of people suffering from schizophrenia, and that those who have adopted biomedical explanations for mental distress are also more likely to want less contact with the mentally ill and view them as more dangerous (Watters, 2010). Looking at research on social stigma and biomedical versus psychosocial explanations, Watter states, “Even as we have congratulated ourselves for becoming more ‘benevolent and supportive’ of the mentally ill, we have steadily backed away from the sufferers themselves.”

While one of the goals of Depression Quest is to “fight against the social stigma and misunderstandings that depression sufferers face,” it is possible that the framework utilized may inadvertently contribute to these very problems. By taking the biomedical stance and creating a system in which “correct” choices are implied, Depression Quest may have the effect of teaching its reader-players to take an oversimplified view of depression and other forms of mental dis-ease. Not all people with mental distress wish to take psychopharmaceutical drugs and not all people have access to them or to psychotherapy. While the developers briefly acknowledge barriers to access, they do not discuss the desire of many psychiatric survivors to find alternative forms of healing and care. While it is impossible to create any work which covers every possible relationship to mental dis-ease, Depression Quest through its own writing and system as well as its alliance with iFred promotes a singular, biomedical framework through which to understand the experience of depression. And, as Stone stated, framing mental distress as “illness” suggests that it is an experience “without value.” When one is ill, they seek remedy or cure to rid themself of the illness. Rarely is illness embraced as an aspect of self in this culture.

Gaming without power

What would it look like to create a game about experiences of madness that does not use medicalized discourse? How would one create a game without power?

Games and other interactive digital media may open up possibilities for expression of experiences of madness. The visual and audio elements allow for the expression of things that may not have words yet, or ever. The medium may allow for speaking differently about these experiences of madness in ways that are evocative, uncomfortable, confusing, poetic, disturbing, messy, and human. It may allow for the creation of art that is of the experience, not just about. Games that are phenomenological rather than explanatory.

It is possible, and my hope, that Depression Quest will open the way for more people to use this medium as a tool for expression of experiences of mental distress, for the expression of humanity’s extreme states of being is needed. Coming face to face with suffering and confusion and brilliance may be necessary in a fight to end stigma lest a fight to end stigma ends alterity instead.

References

Foucault, M. (1988). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. New York: Vintage Books.

Stone, B. (2004). Towards a writing without power: Notes on the narration of madness. Auto/Biography, 12, 16-33.

Stone B. (2008). Why fiction matters to madness. In Narrative and fiction: An interdisciplinary approach, (71-77). Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

Watters, E. (Jan 8, 2010). The Americanization of mental illness. New York Times.

New chapter!

WojitNew Meaty Yogurt story! 25 pages! I like this artist's work a lot! The name "Meaty Yogurt" is really gross!

Space, Space, Space! (shinestrength)

Wojit!!!

Have a fight, and calm down afterwards. – [Author's description]

(via Liz Ryerson)

My Mother’s Dog

Wojit:'|

Illustration by Hallie Bateman for The Bygone Bureau

Most days, if I’m working, I ignore my mother’s dog. If she’s really feeling neglected, she will stretch to her full height, which isn’t much, and push against me, her forepaws in the small of my back.

At night, when I sleep on the couch — it’s always on a couch — she will sleep too, a warm gray curl fitted in the crook behind my knees. At night, if I’m working — I’m always working — she will pretend to be asleep but never close her eyes.

Sometimes I will turn to my mother’s dog and whisper, “Hey, do you wanna…” just to see her sit up and tremble. She is waiting to hear how the sentence ends.

“Don’t tease Tootsie!” my mother will chastise, loud in my mind’s ear.

“All right, all right,” I will grumble at no one. “Toots, do you wanna go for a walk.”

My mother’s dog is a miniature schnauzer, a stocky little thing made of perfect right angles and, I think, nerves. When her fur is overgrown she looks less like a dog, more like a stuffed bear. She is so cute when she trots or gallops, when she howls or sighs. She is always sighing. Mostly I avoid looking at her directly. Looking at her feels like a heart attack, my chest gets so tight.

“I know this is going to sound crazy,” I told the veterinarian, “but she’s on the couch too much. Usually she shadows me around the house, but now she just sits there. And — how do I make this not sound crazy — her butt isn’t as perky as it used to be.”

The veterinarian smiled.

“I’m very impressed!” he said to me. “The problem is her spine.”

He put his fingers against my mother’s dog’s back, near her haunches.

“It’s actually this vertebra right here.”

Then he said, “You will be an excellent dog owner. I know the type.”

He winked.

In the waiting room, the receptionist put her hand on my arm.

“Do you want your name on the paperwork,” she asked. She was pointing her clipboard toward me. I looked down at it, at my parents’ names.

“Um, not yet, that’s all right,” I said. Then I clapped my hands over my mouth at the very memory of both of them, and gagged. I tried to not vomit in front of her.

Once, as a child, I made the mistake of asking why I wasn’t allowed to have a dog.

“Poisoned!” my adoptive father shouted in lieu of an answer. “They were poisoned! Rat poison! The neighbor! The neighbor did it!” He scowled and beat his right fist against his chest, as if to ward off some epic dole.

I got a parakeet instead.

I didn’t want a dog. Now I can’t picture not having a dog. Now, when the dog gallivants across the lawn in pursuit of a butterfly or squirrel, my chest becomes so small and tight with love-panic. Of course I am trying to imagine losing her, trying to prepare myself for what that day will feel like — or worse, what all the days after that would feel like.

In quiet moments I turn and look at my mother’s dog and hold my breath, watching for the almost-imperceptible rise and fall.

“Toots,” I might whisper to her, “do you wanna…?” because I am making sure she still comes alive.

There isn’t a longer, more terrible grief than a dog owner’s anticipatory grief. “A dog,” writes John Homans, “can’t figure out that it’s being measured for its grave.”

The two scariest things my mother ever said to me were “I thought you would have a family by now” and “that little dog will be yours someday.”

“Please don’t talk like that,” I snapped.

I used to drive alone between Chicago and my parents’ house, which is twenty-something hours away. During college break I’d sneak into their house in the middle of the night and sit down at the kitchen table with a book or a sandwich.

My mother would invariably wake up first, would appear in the kitchen in her Snoopy t-shirt and boxer shorts, thrilled. It wouldn’t be long, would it, before my adoptive father lumbered in. “Well!” he would bellow from the doorway. And then he wouldn’t hug me; instead he would cup my head in his great, heavy hands, would handle my face roughly before patting me, hard, on the shoulder.

Then it would be all three of us, sitting around the kitchen table with our cups of coffee, interrupting one another.

Once, when my mother was in the hospital, I sneaked into the house, dropped my luggage in the den. My mother’s dog quickly found me out. She threw herself at my feet, a yelping whimpering whorl.

“Well,” my father said from the doorway, “who is it?”

“Hi!” I said. “Sorry to wake you.”

He frowned at me. “Who is it?” he repeated to the dog.

“Oh,” I said, my chest balling into two rolled fists, becoming smaller than any other feeling I’ve ever had. “No, it’s me, Jenny. Your daughter Jenny.”

“Jenny!” he said. “Well! I wondered why the dog was going nuts.” He staggered toward me, took my face in his great, cracked hands, and pressed my head, hard, to his sternum.

This was probably the last time my father ever called me by name.

I hated her as a puppy. She barked at literally everything. Her shrieks would turn to growls when my father or I went to hug my mother.

“You aren’t even listening!” I shouted.

“Hmm?” my mother asked, her head jerking toward me. “Oh. I hear you. You were talking about your English professor.”

“God!” I shouted, rising from the couch and crossing the living room in one easy motion. “Enjoy your replacement daughter!”

“Jenny,” my mother said, but I was already flouncing down the hallway toward my childhood bedroom, which never had a locking door. I slammed the door anyway, flung myself onto the bed.

I waited for my bedroom door to open, but no one came.

“God,” I whispered into a pillow. I shook, furious.

My mother had pleaded with her husband to let her have a dog, and after years of refusing, he finally told her yes. He had driven my mother to the farm, had chosen the whimpering thing himself, had held that squirming little potato in his great, gnarled hands.

I rolled onto my back, resolved to stew to in my childhood bedroom all night. I put a pillow over my face.

“Jenny, love Tootsie,” my mother would order, pointing at that wriggling clutch of teeth and toenails and fur.

I’d eye the dog, unconvinced.

“She’ll be yours someday,” my mother would say then. Her voice would become low and serious, a warning.

It wouldn’t be long, would it. I wondered how long a dog lives. I gritted my teeth, then sobbed into the pillow. My father had made it clear: my parents both expected to die within the dog’s lifetime.

That animal was an egg-timer.

I will be 31 soon. I write about videogames for a living, same as I did when I was 24.

Everything else, though, is different. For one thing, there’s this dog.

She’s nine.

Sometimes we are walking together — me, shuffling and grumpy, hating the outdoors, her, nuzzling each individual strand of grass, it would seem — when someone will stop me to say, “Hey! Cute dog!”

I immediately reply, “Thanks! She was my mom’s.”

“Is she friendly?” the person may ask, stooping to get sniffed.

“Of course she is friendly,” I answer impatiently.

My mother’s dog is waiting by my feet right now, pestering me with her plaintive looks.

Sometimes I stop typing and look down at her, like this. And she hears the pause and she looks up at me with those wide, wet horse-eyes, just like this.

And I have to smirk at her, I have to, because here we are, just the two of us, only ever just the two of us, what a pair. Probably we are the only pair in the world that has ever really made any sense.

Block Faker (droqen)

WojitThis game is super cute and great play it and I feel a bit mean now.

new game “parasite”

WojitDid I not share this? This! I'm sharing it!

made a game for the new inquiry. my interview was also released.

game [parasite]

interview [beautiful weapons]

Sourballs vs. Tour Plans And Each Other

Wojit"I'm not much into Festivals anyway. Or Summer. Really more of a Dark Weird Room person."

Our main characters and their bands seem to exist in these relatively small scenes and circles, and I’ve always thought it all seemed relatively detached from whatever this universe’s actual mainstream is (Candy Hearts too, even though they were accused of being too radio friendly) — so, hey, what gets massive national airplay on their crummy commercial rock radio? What contemporary bands make Turpentine visibly frown when their hit singles come on in the laundromat? Answer: the headliners of SUMMERAMA FEST.

I’m pretty happy with that flyer. I think I captured what I was going for.

Save Points

WojitThis is a beautiful article.

by Riley MacLeod

Riley MacLeod is a trans writer and activist based in Brooklyn, NY. He is an editor at Topside Press and co-editor of “The Collection: Short Fiction from the Transgender Vanguard,” which won the 2012 Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Fiction.

Trigger warning for discussions of suicide.

Everything bad seems to happen to me when playing Spec Ops: The Line.

The last essay I wrote for this site was about playing Spec Ops during Hurricane Sandy and the surreal feeling of playing a disaster game during a corporeal disaster. Over the winter I read Brendan Keogh’s Killing is Harmless and re-downloaded Spec Ops, intending to dig up some of the intricacies he points out, but I never got around to it. Last week, tired of the vapid sexism of Splinter Cell: Conviction, picked up during a Steam sale, I went back to Captain Walker’s ruined Dubai. It was nice, in a weird way. I’d forgotten how beautiful and harsh the environments were, and new headphones wrapped me in the rich sound design, the gritty footsteps and rattling gear of my doomed Delta squad, the solid crunch of bodies hitting glass. I found some new things–the tree that dies when you turn around, the ghost of a dead woman in the windows of a skyscraper, the ending you get when you fight your way through to the very last man. Done with a playthrough, I found myself achievement hunting, which I was dubious about in my essay, and I investigated what I was doing as I played late into the night. I realized that I didn’t want to leave Walker, Adams, and Lugo alone in that fucked-up place, stuck with their demons and their failures. I felt bad for them and what I was urging them to do with a gentle digital hand on their backs. I couldn’t change what happened to them, but I could at least try to guide them, keep them for too long in the corridors and ledges between combat arenas, staring shiftily at each other before they had to learn what atrocity I knew was coming next.

The next morning, I learned that I’d probably been playing Spec Ops when Donna left the house to kill herself.

*Donna was trans, and my neighbor, and my friend, and an author in the book I edited. We won a Lambda Literary Award for trans fiction (the first transpeople to do so) the week before she died. We had a free ticket to the award ceremony and tried to encourage her to come, but she didn’t want to. When she didn’t want to do things, I always assumed she was gaming. I saw her in my Steam friends list constantly, ever since we got together to play Left 4 Dead 2 one night. She was better at it than I was, and she laughed at me as I sat cross-legged on her bed, screaming and swearing and engaging in the general constant chatter I keep up when I game. She teased me for calling the AI “robots” and for lording my humanity over them when I succeeded where they failed. I got a couple other friends into it, and we tried to get her to play with us, but she was usually playing something else. She tried to get me into Borderlands 2, but by the time it went on sale she was done with it. She was really into XCOM, and I took a peek at it after seeing how much she played it, but it seemed a little too slow for my tastes. We talked about the Mass Effects, and she played Dishonored in April, but according to her Steam stats it doesn’t look like she finished it. She gave me a copy of DotA 2 I haven’t installed. She played a lot of Civ 5 with my L4D2 friend, which they tried to convince me to play, but I could never justify the price. While I don’t like blockbuster shooters per se, at the end of a long day of work, I usually want to disappear into a game that won’t offend me too much but won’t require too much of me either. I usually say I need a game I can drink to. Indie games or puzzle games or non-shooters, though I love them, require brainpower, awareness, and energy, which are often in short supply when I can make the time to game.

When I got the call that Donna died, I laughed and said, “No, she’s probably just playing games.” I logged on to Steam, and she wasn’t on. She hadn’t been on in 9 days, according to her profile. Strangely, for the first time, I thought, “That’s a long time. I wonder if something’s wrong.”

*I know a lot of transpeople, myself included, who probably play games too much. I worry about it, sometimes. I wonder what it means, and if we’re escaping, and how you know if escapism is becoming a problem for you. These days, I usually find myself longing to inhabit the bodies of digital men more than my own, and sometimes I’m hard-pressed to understand if I actually have a body at all. Your body never fails you in games, besides short absences of stamina, and when you screw up, no one tends to mention it. No one harps on it and berates you, and they’re just as awed when you succeed as if you’d done it on the first effortless go. Everyone wants to be with you to celebrate your achievements, trusts you and is trustworthy, wants to help you–and, if they don’t, you alone are still enough. You can almost always win, and you’re almost always the hero. The right way to go is laid out on your map or with an arrow or a way marker, and one success leads to the next like a reliable, glittering chain. In many games, you’re the strong one, the tough one, the one scaring other people and making them run. The one who can go anywhere with ease, who isn’t afraid to leave the house at night or use a public bathroom or go to a party or an awards show or a friend’s house. The one who doesn’t need to see a doctor or a therapist or a surgeon or a beautician to force yourself to fit into the world. The one who can sweep love interests into their arms and a cut scene without a second thought, who can pick and choose, who desires and is desired. When I think about it that way, I can’t really be surprised that myself and some of my other trans friends game maybe more than we should.

I’ve been a long-time advocate of games as self-care, which I’m often very vocal about when self-care strategies come up in my radical political circles. Amidst talk of creating a support network, acupuncture, eating well, or herbs, I champion games. I usually say: think about it like this. In a game, you have a clear enemy and a clear goal. Nothing is complicated or tricky. You know you can win, and you can usually do so through the unilateral application of force, which you get to have instead of the cops, politicians, and capitalists of real life. You can always save the world, or meet whatever successful end state the game’s designers have laid out for you, and, besides in games like Spec Ops, everyone is pretty proud of you when you do. It’s the perfect antidote to the long haul of radical politics, I say. The game world is made for you, exists solely for your pleasure and success and violent, self-centered wants. I come away from games not feeling afraid or confused or powerless. For whatever hours I slip behind my keyboard and tug my headphones over my ears, I’m not on the losing team.

And then one of us turns the game off, and maybe those hours of winning aren’t enough.

*The day after Donna died we all hung out in Harlem and cried a lot. Sometimes I forgot why we were there, excited to meet some of her friends I’d never known. A number of folks were gamers. At one point, maybe a little too flush with grief whisky, I was eagerly explaining a presentation about queering game mechanics that I’d given at a conference when someone new entered in the corner of my eye. I glanced briefly toward the door, thinking, “Oh, I hope it’s Donna; I don’t think I ever told her about this.” It wasn’t, of course, and I fell silent suddenly. It didn’t seem real. It felt like a joke, like she’d “Huck Finn-ed us,” as one of my friends said. I’ve lost people before, but there was some absurd part of me that kept thinking things would just reset the next day. I mostly saw Donna in my Steam friends list, inhabiting the same imaginary world as I did, one where death tends not to be a permanent condition. It seemed sad, but surely she’d played enough hours to earn an extra, real life.

The next day things were basically the same, except I was alone at my apartment with no idea what to do with myself. I played games. I stared at Donna’s name in my friends list, texted sadly with another of our friends who was clearly burying himself in Civ 5, now down a playmate. I played Doorkickers, an indie squad-based tactical game whose perceived mechanics intrigued me even though playing a SWAT team made me nervous. The game was still in its alpha stage, and the controls weren’t as responsive as I thought they’d be. Added to that was my own unfamiliarity with strategy games. I rushed headlong, stumbled through doors, planned poorly or not at all. My little pixel troopers became injured and then died. They had little names and little voices that cried out when they were shot or lost a friend.

Even though they were just 1s and 0s, I was sure they hated me.

I found myself replaying missions over and over, at first restarting when one of them died, and later aborting the mission the moment one of them was hit. Like Walker and his squad in Dubai, I wanted to protect them, I wanted to steer them through. I can’t remember at what point I started crying, started snarling in frustration every time they barked “I’m hit!” before I took them back to a time before they had begun the foolish adventure of trying to be part of a world designed to slaughter them. They were poor, ridiculous fucks for thinking they’d make it, for expecting me to help them. They were woefully unprepared. They couldn’t respond fast enough; they didn’t know what was coming; sometimes the tools they were equipped with didn’t function correctly to keep them from doing something stupid and deadly and making everyone miserable. My own inadequacy stared me in the face, and every reset brought a new dark level jammed with corners hiding monsters that my squad, at my hands, had no hope of overcoming.