If you’re looking for TurboTax’s free file option, you probably won’t find it by visiting TurboTax.Intuit.com.

If you’re looking for TurboTax’s free file option, you probably won’t find it by visiting TurboTax.Intuit.com.

Richard Thaler, the University of Chicago professor who just won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, has inspired scholars across different disciplines and fundamentally changed the way we think about human behavior. He is considered the father of behavioral economics — a relatively new field that combines insights from psychology, judgment, and decision making, and economics to generate a more accurate understanding of human behavior.

Economics has long differed from other disciplines in its belief that most if not all human behavior can be easily explained by relying on the assumption that our preferences are well-defined and stable across time and are rational. Back in the 1990s, Thaler began challenging that view by writing about anomalies in people’s behavior that could not be explained by standard economic theory. For instance, in 1991, he started a column in the The Journal of Economic Perspectives with two other colleagues that was all about such anomalies.

Among his many achievements, Thaler inspired the creation of behavioral science teams, often call “nudge units,” in public and private organizations around the globe. Together with Cass Sunstein, he wrote a book in 2008 called Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, which suggests that there are many opportunities to “nudge” people’s behavior by making subtle changes to the context in which they make decisions — a topic I’ve also explored.

Nudges can solve all sorts of problems governments and businesses alike consider important. Here are some examples.

A few years ago, for instance, General Electric’s leaders wanted to address the issue of smoking, believing that it impacted its employees negatively. So, in collaboration with Kevin Volpp and his co-authors, they conducted a randomized controlled trial (think: field experiment). Employees in the treatment group each received $250 if they stopped for six months and $400 if they stopped for 12 months. Those in the control group did not receive any incentive. The researchers found that the treatment group had three times the success rate of the control, and that the effect persisted even after the incentives were discontinued after 12 months. Based on this work, GE changed its policy and started using this approach for its then-152,000 employees.

Policies that may affect how much we eat is another behavior that policy makers and companies that want to encourage healthy lifestyles (e.g., Google and Facebook) consider important. McDonald’s has an old policy of asking whether customers want to super-size their order. As it turns out, they often do. But research by Janet Schwartz and colleagues finds that when customers in a Chinese restaurant are asked if they want to down-size their portions of side dishes, they often do. The percentage of customers who did so in their field experiments, 14% to 33% of them, ate 200 less calories on average.

In research that Thaler himself conducted, defaults were used to increase employees’ savings rates by automatically increasing the percentage of their wage devoted to saving. This is a program called “Save More Tomorrow” (SMarT). SMarT program participants increased their saving rates from 3.5% to 13.6% over the course of 40 months, on average, while savings rates remained stagnant for those who did not participate in the program.

Nudges are also helpful to reduce dishonesty. My colleagues and I conducted a field experiment in collaboration with an insurance company. We asked customers to sign at the top of a form or at the end as they usually do when reporting how many miles they had driven their car the previous year for insurance purposes. By moving the signature to the top, we primed them to act honestly. People more honestly declared their mileage instead of deflating the number in order to lower their premiums like they did when they signed at the bottom of the form.

All of this is not to say behavioral economics is simple for companies to apply. There are plenty of ways to use it in the wrong ways and we’ve seen recent examples of this from organizations like Uber.

Smoking, savings, honesty, and healthy eating may not be items on your list of problems to address or areas where you’d like to see improvements in your own behavior or the actions of people you manage or lead. But no matter what concerns you, adopting a nudge, as Thaler and the many scholars who followed his approach to research tell us, may lead to a powerful change for the better. It just requires an acknowledgment that human behavior is full of anomalies.

Dropbox has a Document Scanner! I had no idea, and had to send 10+ b/w text pages with just my phone, and it did a great job making a clean little pdf off existing photos.

Dropbox has a Document Scanner! I had no idea, and had to send 10+ b/w text pages with just my phone, and it did a great job making a clean little pdf off existing photos.

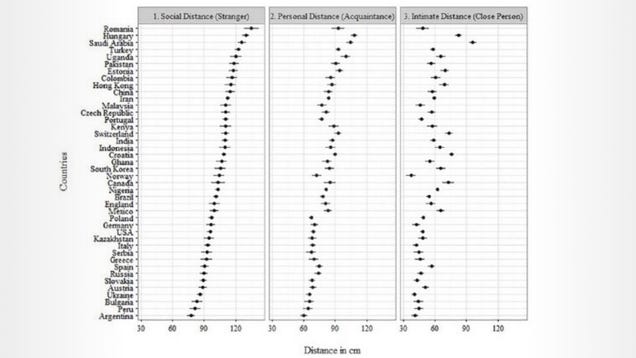

We all have an invisible bubble around us we like to call our “personal space.” If someone hovers inside too long, you feel uncomfortable. But everyone’s bubble size is different from culture to culture. Here’s what those bubbles look like around the world.

The CEO of a large Australian company called me to relay a particular strategy development problem his firm was facing, and ask for my advice. The company was an eager user of my “cascading choices” framework for strategy that I have used for decades and written about extensively, most prominently in the 2013 book I wrote, with friend and colleague A.G. Lafley, called Playing to Win.

My Australian friend explained that each of his five business unit presidents was using the Strategy Choice Cascade, and that all of them had gotten stuck in the same place. They had chosen a Winning Aspiration and had settled on a Where to Play choice. But all of them were stuck at the How to Win box.

It is no surprise, I told my friend, that they have gotten stuck. It is because they considered Where to Play without reference to How to Win.

I’ve heard variants of this over and over. Although I have always emphasized that these five choices have to link together and reinforce each other, hence the arrows flowing back and forth between the boxes, it has become clear to me that I haven’t done a good enough job of making this point, especially as it relates to the choices of Where to Play and How to Win.

The challenge here is that both are linked, and together they are the heart of strategy; without a great Where to Play and How to Win combination, you can’t possibly have a worthwhile strategy. Of course, Where to Play and How to Win has to link with and reinforce an inspiring Winning Aspiration. And Capabilities and Management Systems act as a reality check on the Where to Play and How to Win choice. If you can’t identify a set of Capabilities and Management Systems that you currently have, or can reasonably build, to make the Where to Play and How to Win choice come to fruition, it is a fantasy, not a strategy.

Many people ask me why Capabilities and Management Systems are part of strategy when they are really elements of execution. That is yet another manifestation of the widespread, artificial, and unhelpful attempt to distinguish between choices that are “strategic” and ones that are “executional” or “tactical.” Remember that, regardless of what name you give them, these choices are a critical part of the integrated set of five choices that are necessary to successfully guide the actions of an organization.

I had to tell my Australian friend that locking and loading on Where to Play choices, rather than setting the table for a great discussion of How to Win, actually makes it virtually impossible to have a productive consideration of How to Win. That is because no meaningful Where to Play choice exists outside the context of a particular How to Win plan. An infinite number of Where to Play choices are possible, and equally meritorious — before considering each’s How to Win. In other words, there aren’t inherently strong and weak Where to Play choices. They are only strong or weak in the context of a particular How to Win choice. Therefore, making lists of Where to Play choices before considering How to Win choices has zero value in strategy.

For example, Uber made a Where to Play choice that included China because it’s a huge and important market. But being huge and important didn’t make that choice inherently meritorious. It would have been meritorious only if there had been a clear How to Win as well — which it appears there never was. Microsoft made a Where to Play choice to get into smartphone hardware (with its acquisition of Nokia’s handset business) because it was a huge and growing market, seemingly adjacent to Microsoft’s own, but it had no useful conception of how that would be twinned with a How to Win — and it lost spectacularly. P&G made a Where to Play choice to get into the huge, profitable, and growing pharmaceutical business with the acquisition of Norwich Eaton, in 1982. While it performed decently in the business, it divested the business in 2009 because, in those nearly two decades, it came to realize that it could play but never win in that still-exciting Where to Play.

Moreover, no meaningful How to Win choice exists outside the context of a particular Where to Play. Despite what many think, there are not generically great ways to win — e.g., being a first mover or a fast follower or a branded player or a cost leader. All How to Win choices are useful, or not, depending on the Where to Play with which they are paired. A How to Win choice based on superior scale is not going to be useful if the Where to Play choice is to concentrate on a narrow niche — because that would undermine an attempted scale advantage.

Undoubtedly, Uber thought its How to Win — having a easy-to-use ride-hailing app for users twinned with a vehicle for making extra money for drivers — would work well in any Where to Play. But it didn’t work in the Where to Play of China. It turned out that Uber’s How to Win had a lot to do with building a first-mover advantage in markets like the U.S.; when Uber was a late entrant, the Where to Play wasn’t a simple extension, and it exited after losing convincingly to first mover Didi. Perhaps Microsoft felt that its How to Win of having strong corporate relationships and a huge installed base of software users would extend nicely into smartphones, but it most assuredly didn’t. As a Canadian, I can’t help but recall the many Canadian retailers with powerful How to Wins in Canada (Tim Hortons, Canadian Tire, Jean Coutu) that simply didn’t translate to a Where to Play in the U.S. Perhaps there is some solace, however, in retailer Target’s disastrous attempt to extend its U.S. How to Win into the Canadian Where to Play — turnabout is, I guess, fair play.

The only productive, intelligent way to generate possibilities for strategy choice is to consider matched pairs of Where to Play and How to Win choices. Generate a variety of pairs and then ask about each:

Those Where to Play and How to Win possibilities for which these questions can plausibly be answered in the affirmative should be taken forward for more consideration and exploration. For the great success stories of our time, the tight match of Where to Play and How to Win is immediately obvious. USAA sells insurance only to military personnel, veterans, and their families — and tailors its offerings brilliantly and tightly to the needs of those in that sphere, so much so that its customer satisfaction scores are off the charts. Vanguard sells index mutual funds/ETFs to customers who don’t believe that active management is helpful to the performance of their investments. With that tight Where to Play, it can win by working to achieve the lowest cost position in the business. Google wins by organizing the world’s information, but to do that it has to play across the broadest swath of search.

It doesn’t matter whether the strategic question is to aim broadly or narrowly, or to pursue low costs or differentiation. What does matter is that the answers are a perfectly matched pair.

A few months ago, I was waxing poetic about plutonium, how to establish essential job functions, and quality-testing diet scrapple. What got into me?

Now, I’ve got a cautionary tale, in the form of a recent federal court opinion, to help you good folks navigate away from some of the Americans with Disabilities Act traps. Lest you like litigation and lawyer bills.

The case is called Slayton v. Sneaker Villa and you can find the court’s opinion here.

Here are the important facts:

So glad you asked, let’s turn to Judge Mitchell Goldberg from the Eastern District of PA for some answers. How about a little sum-sumpin on an employer mandating physical presence at work as an essential job function:

Consideration must be given to Defendant’s judgment that physical presence in the office was an essential function…A written job description “shall be considered evidence” of a job’s essential functions. Here, the written description for the Corporate Recruiter position does not speak directly to physical presence in the office…

…

Plaintiff maintains that she could have performed the true essential functions of her job at home, so long as she had access to a telephone and the Internet.

…

Because I must view the evidence in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, I conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether physical presence in the office was an essential job function.

And what about the plaintiff’s ability to travel? I mean, the defendant needed her to go to lots of job fairs and be the face of the company’s recruiting efforts. That may be a job requirement. But, essential? What do you say, Judge?

Defendant highlights that Plaintiff admitted during her deposition that she was advised during her interview process that the company was expanding, and that the position required travel both inside and outside the Philadelphia area for job fairs and recruitment initiatives.

…

Although the written job description of the Corporate Recruiter position does not list the ability to travel as one of the “Principle [sic] Duties and Responsibilities,” the “[a]bility to travel in all markets serviced by [Defendant]” is listed under the “Qualification/Skills & Knowledge Requirements” section of the position summary.

Importantly, courts have recognized that a “requirement” of a given position may be distinguished from the “essential function(s)” of that position for purposes of assessing the second element of a plaintiff’s prima facie case.

…

Plaintiff persuasively argues that despite her requests to do so, she never actually traveled to any job fairs during her time working for Defendant.

O for 2 so far for the employer. How about engaging in a good faith interactive dialogue to discuss reasonable accommodations with the plaintiff? Did the company get that right?

While providing Plaintiff with a two-month leave of absence “no questions asked” could certainly be viewed as an accommodation, when viewed in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, a reasonable fact finder could also conclude that Denise Lee did not necessarily engage in the interactive process with Plaintiff during the pair’s March 28 and April 1, 2013 email exchange (which arguably constituted separate and distinct requests for accommodation).

On this point, Lee’s testimony revealed the following:

Q: Had you decided on Saturday, March 30th, that most likely you were going to fire [Plaintiff]?

A: I don’t know.

Q: Is that possible?

A: Yes.

Oof!

Something is rotten in the U.S. economy. Poor men without a college degree are disappearing from the labor force. The share of prime-age men (ages 25-54) who are neither working nor looking for work has doubled since the 1970s.

The U.S.’s labor participation rate for this group of men is lower than every country in the OECD except for Israel (an outlier, because of the high number of non-working Orthodox Jewish men) and Italy (an economic omnishambles). Today, one in six prime-age men in America are either unemployed or out of the workforce altogether—about 10 million men.

So, this is the 10-million-man question: Where did all these guys go?

According to a report from White House economists released last week, non-working prime-age men skew young, are less likely to be parents, are disproportionately black and less educated, and are concentrated in the South.

In the last few years, several writers and economists have suggested that many of them are in school, on disability, or in prison. More optimistically, some said that men are more likely to help their spouses with raising children and cleaning the house. But upon investigation, none of these answers fully explains the disappearance of prime-age men.

1) Are they in school?

This would be one of the most benign—or even hopeful—reasons for the drop in male participation. Alas, it doesn’t seem to explain much.

Since 1990, the number of men over the age of 25 enrolled in a post-secondary institution has increased slightly, from 2.5 million to about 3 million, most of which was an increase among people enrolled part-time. Overall, a jump of 500,000 accounts for just a fraction of the growth of non-working men. (If the male participation rate hadn’t changed since 1990, there would be about 3 million more men in the labor force.)

The men most likely to drop out of the labor force today are those who never started college. This is a remarkable shift. Fifty years ago, college graduates and high-school dropouts were similarly likely to work, as one can see in the graph below. Today a high-school graduate who has never gone to college is four times more likely to drop out of the labor force than he was in 1964.

Men between 25 and 54 are much better educated than they were in 1964. That fact alone should have predicted a rising participation rate, since college graduates are more likely to work. Instead, the least educated men are abandoning the work force more than ever. That is the real mystery.

2) Are they on disability?

This is another common explanation for the drop in male participation. But again it doesn’t explain more than a fraction of the phenomenon.

There’s not much doubt that Social Security Disability Insurance takes people out of the workforce, often by inelegant design. In order to qualify for disability payments, people typically have to prove that they cannot work full-time. SSDI critics say this policy sidelines many people who might otherwise be able to contribute to the economy.

But how many people does SSDI really remove? From 1967 to 2014, the share of prime-age men getting disability insurance rose from 1 percent to 3 percent. There is little chance that this increase is entirely the result of several million fraudulent attempts to get money without working. But even if it were, SSDI would still only explain about one-quarter of the decline in the male participation rate over that time. There are many good reasons to reform disability insurance. But it’s not the singular driving force behind the decline of working men.

3) Do stay-at-home dads account for the change?

This is an easy one: no.

First, married men are more likely to work than non-married men. Second, fathers have stayed in the workforce more than non-fathers. Third, more than 75 percent of prime-age men not in the workforce do not have a working spouse. Fourth, time-use surveys of non-working men have found that they are less likely to be caring for household members than working men. They do, however, watch more than twice as much television.

4) Are they in prison?

This question requires the most complicated answer. Technically, the 1.1 million prime-age men in prison aren’t hurting the participation rate among men, because they aren’t being counted as participants or non-participants. The government omits prisoners before it makes labor-force calculations.

But that’s not even close to the full story. The more meaningful and troubling statistic is that about 9 million prime-age men have been incarcerated. “These men are substantially more likely to experience joblessness after they are released from prison,” the White House economists reported, “and in many states [they] are legally barred from a significant number of jobs.”

There have been several attempts to measure the cost of prison on subsequent employment. A 2010 analysis by Pew Charitable Trusts found that incarceration reduced the average work time of a typical 45-year-old man by 19 percent. Another study estimated that people who go to prison are 30 percent less likely to subsequently find a job than a non-incarcerated person of their age.

There is no question that it’s harder to find a job after somebody gets out of prison. But even if one makes the most aggressive assumptions about the cost of incarceration to unemployment, America’s prison and ex-prison population only explains a fraction of the disappearing male workforce.

It is conceivable that, by degrees, each of these variables is eating away at prime-age male participation rates. Men who leave prison during a time of historic incarceration have had a hard time finding steady work; some men have turned to disability payments to disengage from a workforce that offered poor pay; some adults have returned to school; and a few (perhaps very few) fathers are staying home while their spouses work.

But behind all of these trends, there is a larger story: the decline of sectors dominated by male workers. In 1954, the highwater mark for male participation, the manufacturing and construction sectors accounted for nearly 40 percent of all jobs. Now, after the long decline of manufacturing and the end of the housing bubble, they account for just 13 percent. These are jobs that men without a college degree can count on, and they're much rarer than they used to be. The White House report notes that "when the share of state employment attributable to construction, mining and to a lesser extent manufacturing are higher, more prime-age men participate in the labor force.” In other words, men are more likely to work in areas where the state directly subsidizes employment in male-heavy occupations.

But the private sector is shifting toward work that has historically been done by women. There are four occupations expected to add more than 100,000 jobs in the next decade: personal care aides, home health aides, medical secretaries, and marketing specialists. All of them currently have more female workers than male. "Some of the decline in work among young men is a mismatch between aspirations and identity," Lawrence Katz, a professor of economics at Harvard University, told me last year. "Taking a job as a health technician has the connotation as a feminized job. The growth has been in jobs that have been considered women’s jobs—education, health, government."

Perhaps the United States needs some sort of massive national building project to put these men back to work in jobs that they would be proud and willing to do. The promises of Donald Trump to the contrary, the United States is not poised to bring back manufacturing jobs.

But what about construction jobs?

Several weeks ago, Conor Sen, a portfolio manager and a columnist at Bloomberg View, wrote a widely shared essay predicting that housing would become the dominant economic story of the next five years. Sen worried that it would be hard to find enough workers (mostly men, since construction employment is about 90 percent male) to build the requisite number of houses. After all, construction skews young and less educated, and the U.S. is getting older and more educated. "If we had to find 500,000 construction workers tomorrow, from a math standpoint it would be impossible," he wrote. "The slack isn’t there.”

But the slack is there. Millions of able-bodied men have dropped out of the labor force, mostly because they have stopped looking for work. Many of them badly need to leave their neighborhoods in Appalachia, the Rust Belt, and the Deep South, where the rate of non-working men often hovers around 40 percent. Meanwhile, the U.S. needs more affordable housing construction, particularly in its richest and most populous metro areas.

The White House report lists several ways to raise the employment level of male workers, like criminal justice reform and removing occupational licenses. But here is a bolder plan: A state-and-federally funded voucher program that moves men from economically stricken areas toward metros in need of construction workers.

This plan would require heroic (and heretofore unprecedented) participation from all levels of government. Metropolitan areas might have to rezone neighborhoods to provide for more low-income housing, and the GOP Congress would have to agree to what is essentially a multi-billion dollar stimulus package, which it has repeatedly said it will never do.

Although abrupt moves can be especially socially disruptive for families with young children, the non-working male population skews young, single, and childless. They are already unmoored, untethered from the economy. In this case, encouraging men to dislocate might move them closer to a job and social network that would bring them meaning and community, above and beyond the obvious benefits of a steady paycheck. This could be a way to bring millions of men back from the brink.

A rotor for the i-DCD drive motor, using rare earth metal-free magnets. (credit: Honda)

Honda said on Tuesday that it had created the first commercial hybrid-electric vehicle motor without using any heavy rare earth metals. (Rare earth metals are often divided into “heavy” and “light” categories.) Working with the expertise of Daido Steel Co., Honda’s new motor will appear in this year’s Honda Freed, a hybrid minivan sold in Japan.

Rare earth metals are essential to making a plethora of items, including smartphones, laptops, missiles, and electric cars. Unfortunately, that group of elements are at risk of shortage, and many of them are mined predominantly in China, adding a special political flavor to ensuring a global supply for industry. In 2009, Reuters reported that Toyota, maker of the popular hybrid-electric Prius, risked suffering at the hands of a rare earth metal shortage. And in 2010, China temporarily banned exports of rare earth metals to Japan during a standoff over territory.

The Japanese automaker bristled at that turn of events. Although Honda told Reuters that it started looking into ways to reduce rare earth metal use a decade ago, the recent risk of shortage and the growing popularity of hybrid vehicles spurred the company to look more seriously into ways to "avoid resource-related risks and diversify channels of procurement,” according to a Honda press release.

Most large organizations today are looking for leaders who can easily and effectively move between countries and cultures, taking on expat assignments, understanding disparate markets, and managing diverse teams. Where can they find such talent?

My advice is to look to a group of people I call “global cosmopolitans”— highly educated, multilingual professionals who have already lived, worked, and studied for extensive periods outside their home regions. Whether their international exposure started in their childhood or later, as a result of relocation for education or work, my experience and research confirms that these people often possess five key characteristics that leave them better equipped to tackle complex challenges than their less-global peers:

Global cosmopolitans don’t need training in cultural competence. They have already developed an awareness of their own cultural worldview, a positive attitude toward cultural differences, knowledge of different cultural practices and the ability to understand and communicate with people whose backgrounds differ from their own.

How can organizations find these individuals and keep them engaged?

Identify. Conventional CVs may not reveal the depth of experience accrued in early mobility. Find out who in your organization or applicant pool has lived abroad and take the time to ask about and listen to the story of their journey. Prompt them to assess and discuss the knowledge and skills they acquired through those experiences. You might even help them identify some strengths they didn’t even know they had. Even when international activity is listed on a resume, you’ll want to explore the exact nature of the personal and professional experience.

For example, having worked in China tells only a part of the story. You need to understand what the person did there. Did he launch a business or turn a struggling initiative around? What was the nature and depth of the contact she had with the culture and the people? Did the person travel there, live and work alone there, or manage a team and family there?

Retain. Global cosmopolitans can feel misunderstood and poorly managed. They will be loyal to an organization that provides them with opportunities to use and be recognized for their multicultural skills, but they have a low tolerance for boredom. So give them work that keeps them intellectually stimulated and feeling appreciated – for example, frequent rotation into new and different expat assignments or leadership roles on cross-cultural teams. As they become more senior and choose to settle down in one place, you might also consider asking them to serve as a bridge and translator between headquarters and subsidiaries, relaying demands from above while validating local competence and managing potential conflict.

Remember to think creatively: for global cosmopolitans assigned to HQ, managing a virtual cross-cultural team, taking frequent business trips or presenting at international conferences can help to keep them engaged. As you see what they can do, also look at roles not obviously related to culture in which they might thrive. Their skills can be extremely valuable during any period of change or crisis.

When we see two people meet, we can often predict what happens next: a handshake, a hug, or maybe even a kiss. Our ability to anticipate actions is thanks to intuitions born out of a lifetime of experiences.

Machines, on the other hand, have trouble making use of complex knowledge like that. Computer systems that predict actions would open up new possibilities ranging from robots that can better navigate human environments, to emergency response systems that predict falls, to Google Glass-style headsets that feed you suggestions for what to do in different situations.

This week researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have made an important new breakthrough in predictive vision, developing an algorithm that can anticipate interactions more accurately than ever before.

Trained on YouTube videos and TV shows such as “The Office” and “Desperate Housewives,” the system can predict whether two individuals will hug, kiss, shake hands or slap five. In a second scenario, it could also anticipate what object is likely to appear in a video five seconds later.

While human greetings may seem like arbitrary actions to predict, the task served as a more easily controllable test case for the researchers to study.

“Humans automatically learn to anticipate actions through experience, which is what made us interested in trying to imbue computers with the same sort of common sense,” says CSAIL PhD student Carl Vondrick, who is first author on a related paper that he will present this week at the International Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). “We wanted to show that just by watching large amounts of video, computers can gain enough knowledge to consistently make predictions about their surroundings.”

Vondrick’s co-authors include MIT Professor Antonio Torralba and former postdoc Hamed Pirsiavash, now a professor at the University of Maryland.

How it works

Past attempts at predictive computer-vision have generally taken one of two approaches.

The first method is to look at an image’s individual pixels and use that knowledge to create a photorealistic “future” image, pixel by pixel — a task that Vondrick describes as “difficult for a professional painter, much less an algorithm.” The second is to have humans label the scene for the computer in advance, which is impractical for being able to predict actions on a large scale.

The CSAIL team instead created an algorithm that can predict “visual representations,” which are basically freeze-frames showing different versions of what the scene might look like.

“Rather than saying that one pixel value is blue, the next one is red, and so on, visual representations reveal information about the larger image, such as a certain collection of pixels that represents a human face,” Vondrick says.

The team’s algorithm employs techniques from deep-learning, a field of artificial intelligence that uses systems called “neural networks” to teach computers to pore over massive amounts of data to find patterns on their own.

Each of the algorithm’s networks predicts a representation is automatically classified as one of the four actions — in this case, a hug, handshake, high-five, or kiss. The system then merges those actions into one that it uses as its prediction. For example, three networks might predict a kiss, while another might use the fact that another person has entered the frame as a rationale for predicting a hug instead.

“A video isn’t like a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ book where you can see all of the potential paths,” says Vondrick. “The future is inherently ambiguous, so it’s exciting to challenge ourselves to develop a system that uses these representations to anticipate all of the possibilities.”

How it did

After training the algorithm on 600 hours of unlabeled video, the team tested it on new videos showing both actions and objects.

When shown a video of people who are one second away from performing one of the four actions, the algorithm correctly predicted the action more than 43 percent of the time, which compares to existing algorithms that could only do 36 percent of the time.

In a second study, the algorithm was shown a frame from a video and asked to predict what object will appear five seconds later. For example, seeing someone open a microwave might suggest the future presence of a coffee mug. The algorithm predicted the object in the frame 30 percent more accurately than baseline measures, though the researchers caution that it still only has an average precision of 11 percent.

It’s worth noting that even humans make mistakes on these tasks: for example, human subjects were only able to correctly predict the action 71 percent of the time.

“There’s a lot of subtlety to understanding and forecasting human interactions,” says Vondrick. “We hope to be able to work off of this example to be able to soon predict even more complex tasks.”

Looking forward

While the algorithms aren’t yet accurate enough for practical applications, Vondrick says that future versions could be used for everything from robots that develop better action plans to security cameras that can alert emergency responders when someone who has fallen or gotten injured.

“I’m excited to see how much better the algorithms get if we can feed them a lifetime’s worth of videos,” says Vondrick. “We might see some significant improvements that would get us closer to using predictive-vision in real-world situations.”

The work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation, along with a Google faculty research award for Torralba and a Google PhD fellowship for Vondrick.

Imposing order on the morass of people analytics: HR execs are being bombarded with sales pitches for people analytics that promise to improve every aspect of workforce management from recruiting to what HubSpot’s execs so charmingly called “graduation.” But how do you weave this rather bewildering assortment of digital tools together in a way that is aligned with and supports your talent and corporate strategies?

Jean Paul Isson and Jesse S. Harriot, respectively VP of business intelligence and predictive analytics and former chief knowledge officer at Monster Worldwide, take a good shot at answering that big-picture question in their new book, People Analytics in the Era of Big Data. The authors encapsulate their approach in a framework that organizes people analytics into 7 “pillars” that are broadly based on the responsibilities of the HR function: workforce planning; sourcing; acquisition/hiring; onboarding, culture fit, and engagement; performance assessment and development; churn and retention; and wellness, health, and safety. “The ultimate goal of this framework,” they write, “is to focus your organization’s attention on those areas that are keys to talent analytics success and will lead to greatest return on investment.”

As you might expect, a comprehensive overview of people analytics leads to a pretty thick and sometimes dense book. But the authors ground the pillars in practice using case studies and interviews. One of them describes how Société de Transport de Montréal, the city’s public transport agency, which serves 2.5 million riders per day, is implementing and using people analytics. It is featured in the excerpt below.

Excerpted with permission of the publisher, Wiley, from People Analytics in the Era of Big Data: Changing the Way You Attract, Acquire, Develop, and Retain Talent by Jean Paul Isson and Jesse S. Harriott. Copyright © 2016 by Jean Paul Isson and Jesse S. Harriott. All rights reserved. This book is available at all booksellers.

Société de Transport de Montréal (STM), or the Montreal Transit Corporation, is a public transport agency that operates transit bus and rapid transit services in Montreal, Canada. STM has more than 9,500 employees with an average daily ridership of 2.5 million passengers.

JP Isson had the opportunity to interview Christophe Paris and his team members Josée Gauvreau and Cedric Lepine to discuss how they have been leveraging data analytics in human resources management, such as workforce planning at STM.

Paris and team: It all started a few years ago when our CEO came to us with a specific set of business questions, including:

We then realized that we didn’t have enough insights to answer his questions. And this was really the overarching point from which our People Analytics journey started. We knew that we absolutely had to look into our databases to find out what talent data or information we had available, and we started analyzing and interpreting our employee data. That was the starting point of our People Analytics.

Paris and team: We started to build HR dashboards, HR key performance indicators (KPIs), and HR scorecards. We also started doing some deep-dive analyses of our employees by occupational category, by experience, by profile, and by skill set. The analysis by critical roles was important because there are some critical roles that pertain to really hard-to-fill positions and some that do not. So having that segmentation approach helped us to prioritize based on our company’s business goals and the market conditions.

We were able to provide a diagnosis of our employee population and start addressing questions such as:

To answer the aforementioned questions, we were lucky enough to have a lot of employee data and information from the get-go. It was information that we collected and used to report on and communicate for legal purposes and transparency.

We started by looking at some correlations analyses. We were wondering if there was a significant correlation relationship between some of our employee data and our key business challenges. We then explored hundreds of variables and found out that the number of kilometers traveled was highly correlated with the number of resources. And the correlation was pretty high, about 96 percent.

We explored the relationship between the variation in the amount of employee overtime and the number of kilometers traveled by a bus or subway driver, and found that there was a strong correlation. Based on the correlation, we then built a predictive model. This helped us to determine how many people we needed to deliver service and keep our level of productivity and customer satisfaction high. The model helped us to determine how many resources we would need by occupational category, skill set, and experience.

The findings also provided our senior management team with actionable insights for their strategic planning, and were of tremendous value for our overall workforce planning. They also helped us with our recruitment strategies, as we were able to identify how many new employees we needed in the future for each functional group, as well as:

The overall correlations and predictive model were driven by the exploration of 10 major factors, such as overall spend, the number of drivers, the number of resources, the number of customers who commute, the overall traffic patterns, and so forth.

We then created a second predictive model called the “retirement predictive model,” which we built to help us to anticipate when our employees will leave for retirement. This model helped us to identify which of our employees were candidates for retirement and who exactly will leave on their retirement date. It also helped us identify employees who are more likely to continue working for an additional three to six years.

In the upcoming year, we will have nearly 2,000 people qualifying for retirement, so as an operational business, it is paramount for us to anticipate which employees will leave and when. With this in mind, we built a model for each category of occupation, from managers and support and maintenance staffs to bus and subway drivers and auto mechanics. The key learning from these models was that there is no single, one-size-fits-all People Analytics model. We needed to go local — by category of occupation, critical roles, and experience.

Additionally, there is about a 20 to 30 percent group of employees who, even if they qualify for retirement, can and will still continue to work three to five years later. To understand this employee segment, we were able to build retirement curves and models to anticipate what is coming and get ready by putting proactive strategies in place to mitigate the risk.

Paris and team: The beauty of this project was that everything we leveraged was from our internal HRIS [human resources information system] and Microsoft Excel spreadsheet data. So, for a company like STM that is very operational and business driven, having a fast turnaround and leveraging low-cost software was very well received. It also helped us to quickly showcase the value; for instance, our employee retirement predictive model immediately helped us to anticipate and plan for the future.

The power of the models we developed was based on the fact that we could analyze data at a category level, as well as an employee level. This enabled us to develop macro and micro strategies when approaching our employees, and talent acquisition and retention strategies. It also enables us to understand our workforce planning from employee segments to the individual level.

Paris and team: We are now able to provide future employee retirement figures by occupation, by location, and by skill set. We can predict and indicate which employees might leave in the next three, four, or five years. This helps the business to figure out how to best bridge the resource gap and continue delivering high-quality service without impacting operations.

We were able to deliver solid, easy-to-understand data, and we challenged the old adage about HR not being data driven. We are gradually changing that every day with the work we do. We were able to wow our customers, which is great, and we did this by building up our data intelligence and sharing it with senior management, as well as with all our hiring managers to ensure they have all the insights they need to proactively take action. This helped us to anticipate what trends are coming, how many resources we will need to hire, train, and onboard, and, more importantly, to become true strategic business partners within the company.

Paris and team: It’s paramount to understand the top business questions the company aims to address. For our company, it was retirement planning and workforce planning. It is imperative to keep your business question in mind when you build HR scorecards or dashboards so the business value can be easily connected to the data.

From the data perspective, you have to look at what you already have available; for instance, what data is easily accessible, available, and good? Data integrity, data visualization, and storytelling using this information should be front and center, as it will be the way you communicate the findings and success criteria for your analysis. You have to wow your customers, both internal and external. And it’s important to remember that you don’t have to share all pieces of data you’ve found. You have to keep it simple, make it easy to understand, and just keep to the most relevant data that helps you to convey the message and key findings. And, most of all, keep in mind that workforce planning analytics is a journey; it takes baby steps and is a matter of testing, learning, and sharing. Your input and insights will provide the business with valuable foresight, helping the organization anticipate talent behavior and help your HR team to become real strategic business partners.

A cost-benefit analysis of virtual shareholders’ meetings: As much fun as Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholders’ weekend seems, you have to wonder why the 5,300 or so annual shareholders’ meetings held in the United States haven’t gone virtual. Actually, 90 companies did in 2015, according to NYT's Deal Professor Steven Davidoff Solomon, including Intel, GoPro, SeaWorld Entertainment, PayPal, Fitbit and Yelp.

“Not one shareholder showed up to Intel’s shareholders’ meeting last week. In person, at least,” writes Solomon in an NYT “DealBook” column. “Instead, Intel’s annual meeting was entirely virtual. There was no in-person gathering site, the questions were submitted in advance, and management and the board made all of their presentations online.”

Solomon, who also teaches law at UC Berkeley, goes on to list the many advantages of virtual shareholders’ meetings. Lower costs, higher attendance, more accurate tracking — to say nothing of the opportunity to better “manage troublesome shareholders and their often uncomfortable questions,” and eliminate protests and PR debacles.

Sounds good, right? Not so fast, says Solomon. He thinks the in-person interaction of the traditional shareholders’ meeting is the only chance shareholders have to engage management — and put execs on the spot. “And in difficult situations, the repeated resistance of shareholders can make a difference,” he writes. He also suggests that such meetings are a chance to win over investors and build brands — a finding that Warren Buffett would surely second.

So Solomon gives virtual shareholders’ meetings a thumbs down, even though there seems to be no reason why virtual shareholders’ meetings couldn’t be designed in ways that enhance both attendance and participation. The problem, of course, is that management must want both.

The robotic workforce is here and now: There’s been a lot written about workers being displaced by robots, but a lot of what’s written is written in the future tense. Suddenly, however, the future — which is typically portrayed as dystopian — seems more like the present.

For instance, Apple supplier Foxconn reportedly already replaced 60,000 workers with robots, according a story by Mandy Zuo in the South China Morning Post. “The Foxconn factory has reduced its employee strength from 110,000 to 50,000, thanks to the introduction of robots. It has tasted success in reduction of labour costs,” said a government spokesperson in the province of Jiangsu.

(Update: Reports about Foxconn replacing 60,000 workers appear to be mistaken, per more recent stories.)

Meanwhile, in Crain’s Chicago Business, Micah Maidenberg reports, “This year, Wendy's might roll out customer-facing ordering kiosks in as many as 6,000 stores around the U.S., while McDonald's and Panera Bread are experimenting with them.”

Finally, in Fast Company, Sean Captain writes about Siemens spider bots, which work autonomously in teams to learn and complete tasks in and out of factories. “The spiders know their capabilities and limitations,” explains Captain. “Each is fitted with three gyroscopes and accelerometers, plus actuators in the legs that measure force — all in order to determine the spider's position and how it is moving from one spot to the next. The team can even figure out how to cover for a robot if it breaks down or its battery dies.”

It’s interesting that companies seem to be looking for excuses for replacing people with robots. Foxconn’s move is linked to the safety of Chinese workers, and in the U.S. quick-service restaurant sector, it’s all about those draconian minimum wages. In any case, if the job apocalypse is closer than we thought, it may be that more execs need to be considering a near-term plan for employing the fast-growing robotic workforce.

At many companies, sales generation activities have become disconnected from the operational activities required to fulfill that demand — resulting in conflicting objectives and foregone business opportunities. Bringing the supply-and-demand sides of an enterprise together can represent a significant opportunity for efficiency and value creation.

On May 12, 2016, Professor Theodore Stank, co-author of “Integrating Supply and Demand” from MIT SMR’s Summer 2015 issue, joined contributing editor Steven Paul to present his research on how some companies have bridged the perennial divide between demand generation and the supply chain in a way that maximizes the value to their customers and to themselves.

The webinar covered, through real-life examples, the five stages for successful supply and demand integration:

How can I use takt time in computing labor cost?

Sometimes the searches that lead here give us interesting questions.

While simple on the surface, this question takes us in all kinds of interesting directions.

Actually the simplest answer is this: You can’t. Not from takt time alone.

Takt time is an expression of your customer’s requirement, leveled over the time you are producing the product or service. It says nothing about your ability to meet that requirement, nor does it say anything about the people, space or equipment required to do it.

Cycle time comes in many flavors, but ultimately it tells you how much time – people time, equipment time, transportation time – is required for one unit of production.

Takt time and cycle time together can help you determine the required capacity to meet the customer’s demand, however they don’t give you the entire story.

In the simplest scenario, we have a leveled production line with nothing but manual operations (or the machine operations are trivially short compared to the takt time).

If I were to measure the time required for each person on the line to perform their work on one unit of the product or service and add them up, then I have the total work required. This should be close to the time it would take one person to do the job from beginning to end.

Let’s say it takes 360 minutes of work to assemble the product.

If the takt time says I need a unit of output every 36 minutes, then I can do some simple math.

How long do I have to complete the next unit? 36 minutes. (the takt time)

How long does it take to complete one full unit? 360 minutes (the total manual cycle time)

(How long does it take) / (How long do I have) = how many people you need

360 minutes of total cycle time / 36 minutes takt time = 10 people.

But this isn’t your labor cost because that assumes the work can be perfectly balanced, and everything goes perfectly smoothly. Show me a factory like that… anywhere. They don’t exist.

So you need a bit more.

How much more? That requires really understanding the sources of variation in your process. The more variation there is, the more extra people (and other stuff) you will need to absorb it.

If we don’t know, we can start (for experimental purposes) by planning to run the line about 15% faster than the takt time. Now we get a new calculation.

85% of the takt time = 0.85 x 36 minutes = ~31 minutes. (I am rounding)

Now we re-calculate the people required with the new number:

360 minutes required / 31 minutes available = 11.6 people which rounds to 12 people.

Those two extra people are the cost of uncontrolled variation. You need them to ensure you actually complete the required number of units every day.

“But that cost is too high.”

12 people is the result of math, simple division that any 3rd grader can do. If you don’t like the answer, there are two possible solutions.

Some people suggest slowing down the process, but this doesn’t change your labor cost per unit. It only alters your output. It still requires 360 minutes of work to do one unit of assembly (plus the variation). Actually, unless you slow down by an increment of the cycle time, it will increase your labor cost per unit because you have to round up to get the people you actually need, and/or work overtime to make up the production shortfall that the variation is causing.

So, realistically, we have to look at option #2 above.

This becomes a challenge – a reason to work on improving the process.

Challenge: We need to get this output with 10 people.

Now we have something we can work with. We can do some more simple math and determine a couple of levers we can pull.

We can reverse the equation and solve for the target cycle time:

10 people x 30 minute planned cycle time-per-unit = 300 minutes total cycle time.

Thus, if we can get the total cycle time down to 300 minutes from 360, then the math suggests we can do this with 10 people:

300 minutes required / 30 minutes planned cycle time = 10 people.

But maybe we can work on the variation as well. Remember, we added a 15% pad by reducing the customer takt time of 36 minutes to a planned cycle time (or operational takt time, same thing, different words) of 30 minutes. Question: What sources of instability can we reduce so we can use a planned cycle time of 33 minutes rather than 30?

Then (after we reduce the variation) we can slow down the process a bit, and we could get by with a smaller reduction in the total cycle time:

330 minutes required / 33 minutes planned cycle time = 10 people.

(See how this is different than just slowing it down? If you don’t do anything about the variation first, all you are doing is kicking in overtime or shorting production.)

So which way to go?

We don’t know.

First we need to really study the current process and understand why it takes 360 minutes, and where the variation is coming from. Likely some other alternatives will show themselves when we do that.

Then we can take that information, and establish an initial target condition, and get to work.

And finally, if you just use this to reduce your total headcount in your operation, you will, at best, only see a fraction of the “savings” show up on your bottom line. You need to take a holistic approach and use these tools to grow your business rather than cut your costs. That is, in reality, the only way they actually reach anywhere near their potential.

Fed from The Lean Thinker.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Rosenthal

Using Takt Time to Compute Labor Cost

Artificial intelligence (AI) is on quite a run, from Google’s AlphaGo, which earlier this year defeated Go world champion Lee Sedol four games to one, to Amazon’s Echo, the voice-activated digital assistant.

The trend is heating up the sales field as well, enabling entirely new ways of selling. Purchasing, for example, is moving to automated bots, with 15%–20% of total spend already sourced through e-platforms. By 2020 customers will manage 85% of their relationship with an enterprise without interacting with a human. Leading companies are experimenting with what these technologies can do for them, typically around transactional processes at early stages of the customer journey.

For example, AI applications can take over the time-consuming tasks of initiating contact with a sales lead and then qualifying, following up, and sustaining the lead. Amelia, the “cognitive agent” developed by IPsoft, can parse natural language to understand customers’ questions, handling up to 27,000 conversations simultaneously and in multiple languages. And because “she” is connected to all the relevant systems, Amelia delivers results faster than a human operator. Of course, there will be occasions when even AI is stumped, but Amelia is smart enough to recognize when to involve a human agent.

As we learned from researching our book, Sales Growth, companies that have pioneered the use of AI in sales rave about the impact, which includes an increase in leads and appointments of more than 50%, cost reductions of 40%–60%, and call time reductions of 60%–70%. Add to that the value created by having human reps spend more of their time closing deals, and the appeal of AI grows even more.

Clearly, AI is bringing big changes. But what do they mean for sales — and the people who do it? We see two big implications.

The “death of a salesman” is an overplayed trope, but the road ahead does mean significant changes for how sales work is done. The changes are primarily focused on automating activities rather than individual jobs, but the scale of those changes is likely to profoundly disrupt what sales people do.

We analyzed McKinsey Global Institute data on the “automatability” of 2,000 different workplace activities, comparing job requirements to the current capabilities of leading-edge technology. We found that 40% of time spent on sales work activities can be automated by adapting current technologies. If the technologies that process and understand natural language reach the median level of human performance, this number will rise to 47%.

Pity the parts salesperson, an occupation where 85% of all activities have the potential to be automated with today’s technology. Gathering customer or product information to determine customer needs, processing sales or other transactions, taking product orders from customers, and preparing sales or other contracts collectively account for approximately three-quarters of a parts salesperson’s time — and all can be automated. On the other hand, most of a sales manager’s activities, which involve strategic decision making and employee supervision and coaching, cannot be automated.

Much of the focus on AI and automation has been on which jobs or tasks will be replaced. That’s understandable, of course. But it’s clear, if less explored, that sales leaders and reps will continue to be crucial to the sales process even as they adapt to working with machines.

The “human touch” will need to focus more on managing exceptions, tolerating ambiguity, using judgment, shaping the strategies and questions that machines will help enable and answer, and managing an increasingly complex web of relationships with employees, vendors, partners, and customers.

Machine learning and automation tools, for example, will be able to source, qualify, and execute far more sales opportunities than reps can keep up with. Sales leaders therefore need to develop clear escalation and exception protocols to manage the trickiest or most valuable situations, making sure a sales rep keeps a robot from losing a big sale.

While machine learning will continue to evolve, for the foreseeable future senior executives must point the technology in the right direction. They’ll have to think about a number of questions: What sorts of decisions should be automated? Which kinds of automation will help deliver on strategic growth goals? What are the legal and risk implications? How will vendor and technology relationships need to be managed and integrated to create the greatest competitive advantage?

There are implications too for the hiring and managing of sales reps. An empathetic personality will still be important, but beyond their relationship skills, reps will succeed based on their ability to understand and interpret data, work effectively with AI, and move quickly on opportunities. That’s a very different sales profile from the one many companies recruit for today.

Machines are already doing many sales jobs more effectively and efficiently than their human counterparts, and boosting customer satisfaction in the process. How sales leaders respond will determine what the future of sales looks like — and how well it works.

Your most valuable employee is someone who holds significant worth at your company. It’s easy to see which salesperson sells the most, but is that person truly the most valuable? It may be the receptionist who holds the foundation of the company together or the custodian who found a way to cut utility costs last year.

How do you identify the most valuable employees and hire others just like them? Ken Sundheim at Forbes identified 15 traits of the ideal employee. We’ll focus on four: intelligence, ambition, culture fit and hard work.

Intelligence

Intelligence can be difficult to identify, but you can look at how your employees handle challenges. Do they offer solutions to problems? Do things run better when they are around? You might think, “He’s just an admin,” but if he came up with a new way to organize paperwork and increased your efficiency by 20 percent, he might be more valuable than you thought.

To keep reading, click here: Identify Your Most Valuable Employee

Even decades after the Family and Medical Leave Act was enacted, employers are still making basic mistakes, such as presuming that an employee who wants FMLA leave has to use the word “FMLA,” failing to properly calculate FMLA allotment or use, and disparaging those who take leave. Perhaps managers find some provisions unclear or simply need a refresher. Along those lines, here are 10 “takeaways” from recent court decisions over alleged FMLA mistakes.

1. When calculating FMLA entitlement, include overtime and “working lunches.” An employee’s actual workweek is the basis for determining FMLA leave entitlement. This means overtime and breaks that were spent working must be included when calculating an employee’s FMLA entitlement. In one recent case, the Eighth Circuit held that, although a tire manufacturing employee had the choice of whether to put his name down for certain overtime shifts, the overtime became mandatory once he did that and was selected for a shift, so the overtime should have been included in calculating his allotment of FMLA leave for the year. Given that his overtime hours varied from week to week, the employer should have calculated his leave in accordance with 29 C.F.R. §825.205(b)(3). Instead, the overtime hours were not considered at all. His FMLA interference claim would therefore go to trial.

In another case, a corrections department counselor claimed understaffing kept him from eating in the employee lunchroom and he had to eat where inmates congregated. This, ruled a federal court in Illinois, raised a question on whether his lunches were spent predominantly benefitting his employer and should have been included in calculating whether he met the 1,250-hour requirement. Also at issue was whether the employer knew of his working lunches: 29 C.F.R. §785.11 states that unrequested work is work time if the employer “suffer[s] or permit[s]” the work and “knows or has reason to believe” the employee is working.

2. In calculating amount of leave used—don’t include days an employee is not scheduled. Be careful in calculating how much FMLA leave has been used—FMLA leave may be taken in periods of weeks, days, hours, and sometimes less than an hour. The employer must allow employees to use FMLA leave in the smallest increment it allows for other forms of leave, as long as it is no more than one hour. When calculating the amount of leave used, exclude days an employee would not be working (e.g., weekends, temporary plant closures, holidays).

One employer faces trial for including weekends in calculating an employee’s FMLA usage (she worked Monday through Friday) and firing her when it thought her leave was used up. The company thought it was “simple math” that her periods of leave in 2013 totaled 12 weeks (84 days) as of December 15, but a federal court in Tennessee disagreed. Weekends were not to be counted, so the total was 60 days and she had not exhausted her FMLA leave by December 15. Also rejected was the employer’s argument that the plant closes for the holidays so she would have soon exhausted her leave anyway. “If the employee is not scheduled to report for work, the time period involved may not be counted as FMLA leave,” the court noted, quoting the DOL’s response in the Federal Register to a comment.

3. Neither a medical emergency nor a request using the word “FMLA” is required. One employee won summary judgment as to her employer’s liability for FMLA interference after a federal court in Pennsylvania rejected the employer’s argument that FMLA leave is limited to medical emergencies. The court found it undisputed her parents had a serious health condition and she was entitled to family care type leave to make arrangements for their transition in care. It also found that her need for leave was unforeseeable and she was only required to give notice as soon as practicable—it was enough that she said her “dad was ill, and she had to get the house ready for him to come home” from the “hospital.” If the employer wanted more information on her parents’ health, it could have asked.

As to notice of the employee’s own health condition and need for leave, if there is a known history and the employee shows symptoms at work, that could be enough under the FMLA. It is up to the employer to learn more. For example, an employee with a history of migraines avoided summary judgment after a federal court in Missouri found that a sick log stating she was absent for “headache” may have triggered the employer’s duty to investigate; instead, it fired her under its attendance policy. In another case, a truck driver receiving treatment for high blood pressure had chest pains and, believing he might be having a heart attack, asked a coworker to tell the manager he was leaving. He was considered a “voluntary quit” since he failed to notify the manager himself, but a federal court in Maryland found triable issues on whether he provided sufficient notice of the need for FMLA leave.

4. Give employees a chance to provide certification. Employers may require employees to provide a medical certification of the need for FMLA leave, but lawsuits often arise if the certification is found deficient. The Second Circuit recently revived an employee’s FMLA claims against an employer and an HR director responsible for a communication breakdown that led to the employee’s discharge. The employee provided certification that she needed to care for her son who was hospitalized with diabetes. After he broke his leg, she sent a new FMLA request for leave through July 9 and repeatedly asked if more information was needed. She heard nothing until she received a July 17 letter stating her paperwork did not justify her absences. She sent emails asking what “paperwork” was needed, but the HR director simply sent a DOL brochure and refused to let her return absent proper documentation. She was fired for job abandonment. To the appeals court, a jury could find the employee made good faith efforts and was thus relieved of her duty to provide certification.

In a case out of Illinois, a staffing agency was denied summary judgment on an FMLA interference claim because it fired the employee one day after requesting her medical certification. An employer may deny leave absent timely certification, explained the federal court, but 29 C.F.R. §825.305(b) defines timeliness to be 15 calendar days from the request for certification. It also requires the employer to warn the employee in writing of the consequences of failing to timely return a certification, and that was not done here.

5. Communicate with employees. As indicated by the HR director’s inadequate responses to an employee’s questions in the Second Circuit case above, it is important to keep a dialogue with employees who request information about their FMLA obligations. It is also important to communicate regarding their job status or what they can expect to change due to their absence. For example, a federal court in Arizona held an employer liable for liquidated damages under the FMLA because it failed to answer a pregnant sales rep’s questions about how her accounts and commissions would be handled during her maternity leave. By not responding to repeated inquiries over seven months, the company essentially forced her to guess as to the professional consequences she would suffer in terms of lost commissions and transferred accounts, reflecting a lack of good faith and willful indifference to the FMLA.

6. You can require the use of customary notice procedures for absences, but with caveats. Cases regularly crop up where employees have been denied leave or disciplined for not following call-in procedures for potentially FMLA-qualifying absences. Employers need to consider if the need for leave was unforeseeable. If it was unforeseeable, employees need only provide notice of the need for FMLA leave “as soon as practicable,” though employers may generally require them to follow normal call-in procedures. In one case, an employee’s bipolar medication interfered with sleep and she overslept, failing to call in an absence before her morning shift. In the opinion of a federal court in Kansas, a jury could find that calling in late was “as soon as practicable” and that the employer interfered with FMLA rights by firing her for tardiness and absences.

In other cases, where employees have no excuse for failing to follow call-in procedures, their FMLA claims usually fail. For example, a Michigan welder had his FMLA claim tossed because he had no good reason for not calling in his late arrival. The federal court found that his deposition testimony providing only “conjectural justifications” such as he was probably suffering an anxiety attack at the time, were not enough to avoid summary judgment. The result was the same for a Delta flight attendant based in Utah who was fired for violating airline policy by accepting an assignment and then canceling without sufficient notice.

7. Avoid derogatory remarks about those who take leave. If there’s one thing that’s going to make a plaintiff’s case easier in proving unlawful intent, it is a manager’s or decisionmaker’s derogatory remarks about a statutorily protected activity. In one case from a federal court in Indiana, an employee was previously disciplined for excessive absences and was subject to a last chance agreement, but he still survived summary judgment on his FMLA claims, which were supported by his supervisor’s disapproving remarks about his need for leave, including that he was on “thin ice” and was “burying himself.” In a federal case out of Illinois, a car salesman who was fired 13 days after returning from FMLA leave for heart surgery won an extra $308,240 in liquidated damages on his FMLA retaliation claim after the employer failed to show it acted in good faith. Significantly, his visible heart pack was treated with open disdain by his supervisor, and he was told “don’t die at the desk or I am going to drag you outside and throw you in the ditch.” He was also threatened with demotion.

8. Be consistent in your treatment of employees before and after leave. A change in the way an employee is treated after FMLA leave may be considered evidence that the leave was a negative factor in any disciplinary action. In one case, an employee claimed that as she took more FMLA leave, her new supervisor began to “watch her like a hawk,” then gave her warnings for allegedly violating attendance and personal phone usage policies, eventually placing her on two performance improvement plans and firing her. This was enough, ruled a federal court in Illinois, to state a plausible FMLA retaliation claim. In another case, a federal court in Michigan denied summary judgment based largely on evidence that an employee received a positive performance review before her FMLA leave, but afterwards was disciplined and terminated for poor performance, along with evidence that the employer skipped a step in its progressive discipline policy and created an after-the-fact paper trail documenting misconduct that purportedly occurred months earlier.

9. Adjust goals downward for employees who take FMLA leave. While it is important to be consistent in how you treat an employee before and after FMLA leave–and as compared to others, it is also important to adjust time-sensitive goals for those who take FMLA leave. For example, evidence offered by an account executive that her company didn’t adjust her sales targets to account for her intermittent FMLA absences and then fired her for failing to meet her goals raised an issue for trial on whether she was actually fired for taking FMLA leave, ruled a federal district court in New Hampshire. Similarly, a court in Tennessee denied summary judgment on FMLA claims by an employee who took intermittent leave to care for her daughter, based in part on evidence that the employer refused to let coworkers help her meet her goals, nitpicked her work, faulted her for missing goals when she took leave, and treated similarly situated employees who missed goals better than it treated the employee.

10. Not every deviation from what you expect of a seriously ill person suggests FMLA abuse. It’s one thing if an employee posts Facebook pictures of his vacation in St. Martin during FMLA leave—a federal court in Florida held that an employee who did just that failed to show he was fired for taking FMLA leave rather than for his conduct while on leave. Usually, though, suspected FMLA abuse isn’t so clear, so employers must tread carefully. In one case, a kitchen manager told his employer he was ill with blood in his stool and planned to go to the hospital or health department. Instead, he walked to a diner, had coffee, then drove home, contacting the health department the next day (he was diagnosed with colitis and diverticula and was treated for two years). Though he was fired for walking off the job, a federal court in Tennessee found triable questions on whether he gave notice of an FMLA-qualifying condition and triggered a retaliatory action. In a case out of Maine, a long-time employee approved for intermittent leave due to chronic anxiety told his employer he was taking the rest of the day off. He ran into a coworker and they had lunch. Coworkers notified HR, which had him watched. He was suspended for “possible FMLA fraud” and then fired. The federal court held that he stated a plausible FMLA retaliation claim.

Other recent developments of note. In terms of case law, a recent ADA case bears mentioning because it highlights the confusion experienced by some employers concerning the potential overlap in their obligations under the ADA and the FMLA when an employee requests medical leave as an accommodation. In particular, it is important to note that an employee who has exhausted his or her FMLA leave may still be entitled to medical leave under the ADA. As explained by a federal court in Florida, granting the full 12 weeks of FMLA leave may not satisfy an employer’s independent duty to accommodate an employee’s disability under the ADA, such as through additional (though not indefinite) medical leave. Thus, the FMLA does not supplant the ADA when it comes to granting medical leave as an accommodation.

Agency developments should also be noted, including the Department of Labor’s announcement of a new FMLA notice poster that employers will be required to post in their workplaces and a new employer guide designed to provide essential information on FMLA obligations. The DOL also recently issued a fact sheet on the joint employment relationship and the corresponding FMLA responsibilities of primary and secondary employers, including both an example and a chart to illustrate specific responsibilities. More information is available on the Department of Labor’s website, including posters; e-Tools; and fact sheets on employee notice requirements and how to calculate FMLA leave, rules for military family leave, and other topics.

Today we dispatched the second edition of our Leadership That Works Newsletter, a curated monthly digest of the very best leadership links from around the web (compiled by the enthusiastic leadership wonks at ConantLeadership). In the event that you are not subscribed to our mailing list but still have an unquenchable thirst for leadership knowledge – we’ve also compiled the 10 articles from our newsletter letter right here for your reading enjoyment. This month’s links touch on productivity, decision-making, credibility, and much more. Enjoy, and stay curious! (And if you like what you see, you can sign up to receive leadership insights from ConantLeadership here).

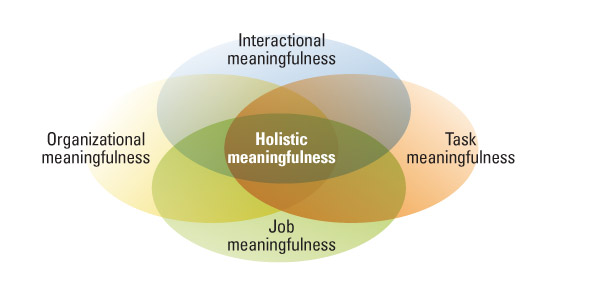

This Harvard Business Review article shows why your purpose, like you, is always evolving. Therefore, you need practices for ensuring your work stays meaningful in the long-term, not just in the present.

In this excellent Strategy+Business article, author Augusto Giacoman tells you exactly why you must put credibility first if you want to get anything substantial accomplished as a leader. And he tells you precisely how to do it.

“A common misconception is that simply because someone excels in the current role, that success will automatically translate to the next level” writes Marty Fukuda in this Entrepreneur article that spells out four compelling reasons to make investing in leadership development a top priority.