Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

#1504; The Confidence of One’s Convictions

Rejoin is the last, best hope of unionism

It is somewhat of a reach to suggest the rather hard (let's call it "medium rare") Brexit he is going for now is compatible with the continuation of our Union.

In 2014 Better Together ran a campaign to keep Scotland in the Union which featured continued EU membership as one of the benefits of voting "No" in that year's independence referendum.

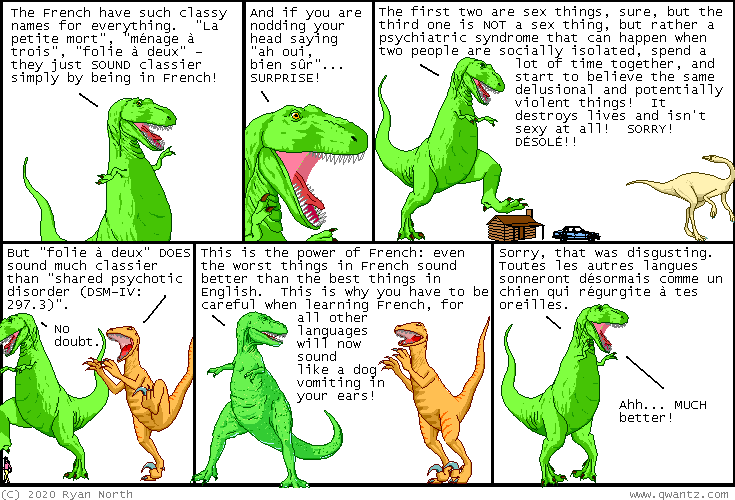

the french have such classy genders for everything

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | January 29th, 2020 | next |

|

January 29th, 2020: Thank you to H̩l̬ne for her help with the translation here! But blame me for all the imagery suggested by the translation. I CAN ONLY ASSUME SHE DOES TOO. РRyan | ||

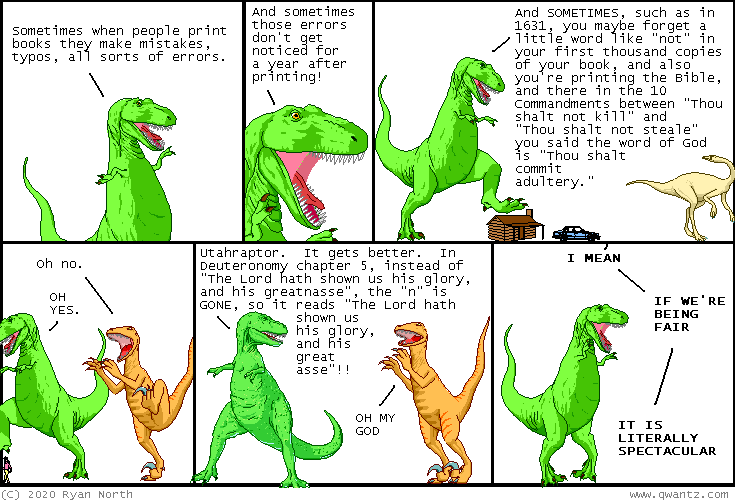

who am i to mock a typo when i have created so many of them, when they are my true legacy

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | January 22nd, 2020 | next |

|

January 22nd, 2020: They're really expensive though so NEVERMIND :( – Ryan | ||

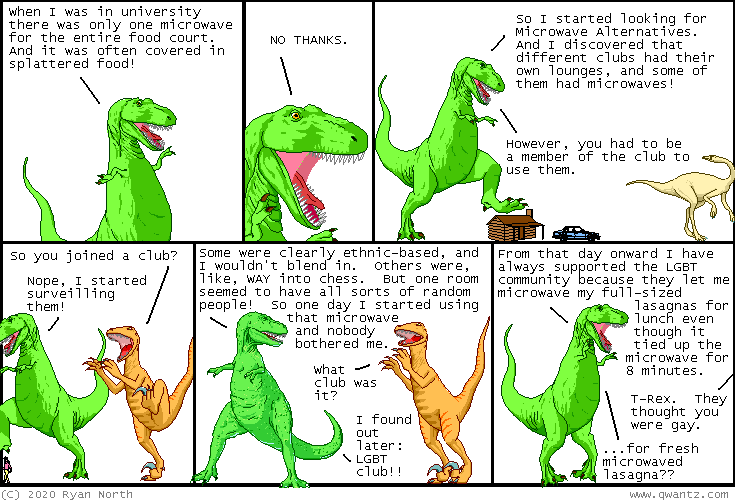

t-rex and the microwave

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | January 10th, 2020 | next |

|

January 10th, 2020: It is just occurring to me that if microwave lasagna is delicious, microwave CHEESE should be delicious too? This changes everything. – Ryan | ||

The strange death of libertarian England

It wasn’t just the Labour party that took a beating in last month’s general election. So too, but much less remarked, did right-libertarianism.

The Tories won on policies that repudiated many of their professed beliefs: a higher minimum wage; increased public spending; and the manpower planning that is a points-based immigration policy. And the manifesto (pdf) promise to “ensure that there is a proper balance between the rights of individuals, our vital national security and effective government” should also alarm libertarians. John Harris quotes an anonymous minister as saying that the libertarianism of Britannia Unchained is “all off the agenda” and that “some of the things we’ve celebrated have led us astray.”

Tories are not out of step with public opinion here. If anything, it is even more antipathetic to right-libertarianism than are Tories. Most voters support higher income taxes on the rich, a wealth tax, and nationalizing the railways, for example. Rick was right months ago to say:

British voters don’t share the free-marketers’ vision…The important thing to understand about right-wing libertarianism is that it is a very eccentric viewpoint. It looks mainstream because it has a number of well-funded think-tanks pushing its agenda and its adherents are over-represented in politics and the media. The public, though, have never swallowed it.

A bit of me sympathizes with right-libertarians here. I suspect that one reason for public antipathy to free markets is that people under-appreciate the virtue of spontaneous order – that emergent processes can sometimes deliver better outcomes than state direction.

Nevertheless, all this raises a question: why are we not seeing more opposition to Johnsonian Toryism from right-libertarians?

You might think its because right-libertarianism has morphed into support for Brexit. Whilst I don’t wish to deny there is some link between the two, many Brexiter MPs have failed a basic test of libertarianism. In 2018 the likes of Bridgen, Cash, Duncan-Smith, Rees-Mogg and Francois all voted against legalizing cannabis.

One possibility is that they regard him as the lesser of two evils – they are supporting him with a heavy heart.

A second possibility has been described by Tyler Cowen. Intelligent right-libs have realized that free markets are not the panacea they thought and have shifted their priorities towards improving state capacity. Examples of this might – in different ways – be Dominic Cummings or Sam Bowman.

Perhaps relatedly, right-libertarianism has lost its material constituency. It once appealed to people by offering tax cuts. Today, however, many of the sort of businessmen who in the 80s wanted lower taxes now want other things, such as better infrastructure.

If these are respectable reasons for the decline of right-libertarianism, I suspect there are less reputable ones.

One is that we have lost the cast of mind which underpins right-libertarianism – that of an awareness of the limits of one’s knowledge. We need freedom, thought Hayek, because we cannot fully understand or predict society:

Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseeable and unpredictable actions, we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom. Any such restriction, any coercion other than the enforcement of general rules, will aim at the achievement of some foreseeable particular result, but what is prevented by it will usually not be known....And so, when we decide each issue solely on what appear to be its individual merits, we always over-estimate the advantages of central direction. (Law Legislation and Liberty Vol I, p56-57.)

We live, however, in an age of narcissistic blowhards who are overconfident about everything. This is a climate which undervalues freedom.

Worse still, I suspect that some right-libertarians were never really sincere anyway. They professed a love of freedom only as a stick with which to beat the old Soviet Union. Liberty was only ever a poor second to shilling for the rich. And their antipathy to Gordon Brown was founded not upon a rightful distaste for the authoritarian streak in his thinking but upon simple tribalism. Maybe Corey Robin was right:

The priority of conservative political argument has been the maintenance of private regimes of power.

This isn't just a UK phenomenon, illustrated by Paul Staines: some (not all) US libertarians found it easy to throw in their lot with Trump.

Whatever the reason for the demise of right-libertarianism, however, there is perhaps another lesson to be taken from it – that you cannot nowadays achieve much political change via thinktanks alone.

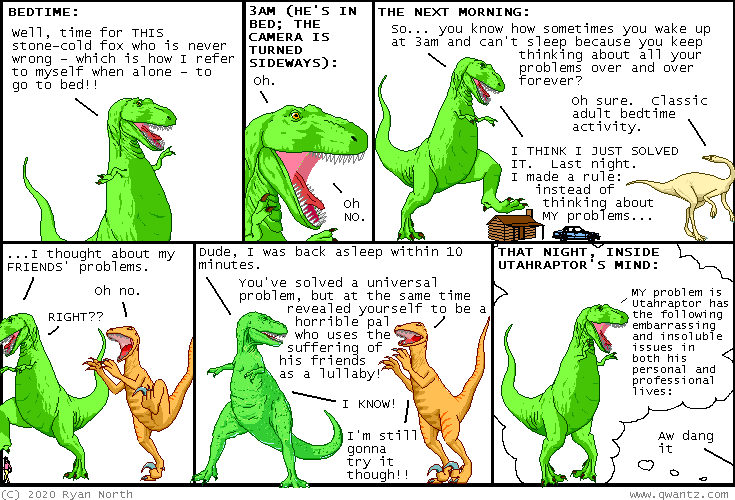

slumbertime tips comix

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | January 3rd, 2020 | next |

|

January 3rd, 2020: HAPPY NEW YEAR!! Thank you all for reading my comic - it's been over a decade doing this and I love it AND YOU, QUITE POSSIBLY?? – Ryan | ||

Artificial Intelligence: Threat or Menace?

(This is the text of a keynote talk I just delivered at the IT Futures conference held by the University of Edinburgh Informatics centre today. NB: Some typos exist; I'll fix them tonight.)

Good morning. I'm Charlie Stross, and I tell lies for money. That is, I write fiction—deliberate non-truths designed to inform, amuse, and examine the human condition. More specifically, I'm a science fiction writer, mostly focusing on the intersection between the human condition and our technological and scientific environment: less Star Wars, more about bank heists inside massively multiplayer computer games, or the happy fun prospects for 3D printer malware.

One of the besetting problems of near-future science fiction is that life comes at you really fast these days. Back when I agreed to give this talk, I had no idea we'd be facing a general election campaign — much less that the outcome would already be known, with consequences that pretty comprehensively upset any predictions I was making back in September.

So, because I'm chicken, I'm going to ignore current events and instead take this opportunity to remind you that I can't predict the future. No science fiction writer can. Predicting the future isn't what science fiction is about. As the late Edsger Djikstra observed, "computer science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes." He might well have added, or science fiction is about predicting the future. What I try to do is examine the human implications of possible developments, and imagine what consequences they might have. (Hopefully entertainingly enough to convince the general public to buy my books.)

So: first, let me tell you some of my baseline assumptions so that you can point and mock when you re-read the transcript of this talk in a decade's time.

Ten years in the future, we will be living in a world recognizable as having emerged from the current one by a process of continuous change. About 85% of everyone alive in 2029 is already alive in 2019. (Similarly, most of the people who're alive now will still be alive a decade hence, barring disasters on a historic scale.)

Here in the UK the average home is 75 years old, so we can reasonably expect most of the urban landscape of 2029 to be familiar. I moved to Edinburgh in 1995: while the Informatics Forum is new, as a side-effect of the disastrous 2002 old town fire, many of the university premises are historic. Similarly, half the cars on the road today will still be on the roads in 2029, although I expect most of the diesel fleet will have been retired due to exhaust emissions, and there will be far more electric vehicles around.

You don't need a science fiction writer to tell you this stuff: 90% of the world of tomorrow plus ten years is obvious to anyone with a weekly subscription to New Scientist and more imagination than a doorknob.

What's less obvious is the 10% of the future that isn't here yet. Of that 10%, you used to be able to guess most of it — 9% of the total — by reading technology road maps in specialist industry publications. We know what airliners Boeing and Airbus are starting development work on, we can plot the long-term price curve for photovoltaic panels, read the road maps Intel and ARM provide for hardware vendors, and so on. It was fairly obvious in 2009 that Microsoft would still be pushing some version of Windows as a platform for their hugely lucrative business apps, and that Apple would have some version of NeXTStep — excuse me, macOS — as a key element of their vertically integrated hardware business. You could run the same guessing game for medicines by looking at clinical trials reports, and seeing which drugs were entering second-stage trials — an essential but hugely expensive prerequisite for a product license, which requires a manufacturer to be committed to getting the drug on the market by any means possible (unless there's a last-minute show-stopper), 5-10 years down the line.

Obsolescence is also largely predictable. The long-drawn-out death of the pocket camera was clearly visible on the horizon back in 2009, as cameras in smartphones were becoming ubiquitous: ditto the death of the pocket GPS system, the compass, the camcorder, the PDA, the mp3 player, the ebook reader, the pocket games console, and the pager. Smartphones are technological cannibals, swallowing up every available portable electronic device that can be crammed inside its form factor.

However, this stuff ignores what Donald Rumsfeld named "the unknown unknowns". About 1% of the world of ten years hence always seems to have sprung fully-formed from the who-ordered-THAT dimension: we always get landed with stuff nobody foresaw or could possibly have anticipated, unless they were spectacularly lucky guessers or had access to amazing hallucinogens. And this 1% fraction of unknown unknowns regularly derails near-future predictions.

In the 1950s and 1960s, futurologists were obsessed with resource depletion, the population bubble, and famine: Paul Ehrlich and the other heirs of Thomas Malthus predicted wide-scale starvation by the mid-1970s as the human population bloated past the unthinkable four billion mark. They were wrong, as it turned out, because of the unnoticed work of a quiet agronomist, Norman Borlaug, who was pioneering new high yield crop strains: what became known as the Green Revolution more than doubled global agricultural yields within the span of a couple of decades. Meanwhile, it turned out that the most effective throttle on population growth was female education and emancipation: the rate of growth has slowed drastically and even reversed in some countries, and WHO estimates of peak population have been falling continuously as long as I can remember. So the take-away I'd like you to keep is that the 1% of unknown unknowns are often the most significant influences on long-term change.

If I was going to take a stab at identifying a potential 1% factor, the unknown unknowns that dominate for the second and third decade of the 21st century, I wouldn't point to climate change — the dismal figures are already quite clear — but to the rise of algorithmically targeted advertising campaigns combined with the ascendancy of social networking. Our news media, driven by the drive to maximize advertising click-throughs for revenue, have been locked in a race to the bottom for years now. In the past half-decade this has been weaponized, in conjunction with data mining of the piles of personal information social networks try to get us to disclose (in the pursuit of advertising bucks), to deliver toxic propaganda straight into the eyeballs of the most vulnerable — with consequences that are threaten to undermine the legitimacy of democratic governmance on a global scale.

Today's internet ads are qualitatively different from the direct mail campaigns of yore. In the age of paper, direct mail came with a steep price of entry, which effectively limited it in scope — also, the print distribution chain was it relatively easy to police. The efflorescence of spam from 1992 onwards should have warned us that junk information drives out good, but the spam kings of the 1990s were just the harbinger of today's information apocalypse. The cost of pumping out misinformation is frighteningly close to zero, and bad information drives out good: if the propaganda is outrageous and exciting it goes viral and spreads itself for free.

The recommendation algorithms used by YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter exploit this effect to maximize audience participation in pursuit of maximize advertising click-throughs. They promote popular related content, thereby prioritizing controversial and superficially plausible narratives. Viewer engagement is used to iteratively fine-tune the selection of content so that it is more appealing, but it tends to trap us in filter bubbles of material that reinforces our own existing beliefs. And bad actors have learned to game these systems to promote dubious content. It's not just Cambridge Analytica I'm talking about here, or allegations of Russian state meddling in the 2016 US presidential election. Consider the spread of anti-vaccination talking points and wild conspiracy theories, which are no longer fringe phenomena but mass movements with enough media traction to generate public health emergencies in Samoa and drive-by shootings in Washington DC. Or the spread of algorithmically generated knock-offs of children's TV shows proliferating on YouTube that caught the public eye last year.

... And then there's the cute cat photo thing. If I could take a time machine back to 1989 and tell an audience like yourselves that in 30 years time we'd all have pocket supercomputers that place all of human knowledge at our fingertips, but we'd mostly use them for looking at kitten videos and nattering about why vaccination is bad for your health, you'd have me sectioned under the Mental Health Act. And you'd be acting reasonably by the standards of the day: because unlike fiction, emergent human culture is under no obligation to make sense.

Let's get back to the 90/9/1 percent distribution, that applies to the components of the near future: 90% here today, 9% not here yet but on the drawing boards, and 1% unpredictable. I came up with that rule of thumb around 2005, but the ratio seems to be shifting these days. Changes happen faster, and there are more disruptive unknown-unknowns hitting us from all quarters with every passing decade. This is a long-established trend: throughout most of recorded history, the average person lived their life pretty much the same way as their parents and grandparents. Long-term economic growth averaged less than 0.1% per year over the past two thousand years. It has only been since the onset of the industrial revolution that change has become a dominant influence on human society. I suspect the 90/9/1 distribution is now something more like 85/10/5 — that is, 85% of the world of 2029 is here today, about 10% can be anticipated, and the random, unwelcome surprises constitute up to 5% of the mix. Which is kind of alarming, when you pause to think about it.

In the natural world, we're experiencing extreme weather events caused by anthropogenic climate change at an increasing frequency. Back in 1989, or 2009, climate change was a predictable thing that mostly lay in the future: today in 2019, or tomorrow in 2029, random-seeming extreme events (the short-term consequences of long-term climactic change) are becoming commonplace. Once-a-millennium weather outrages are already happening once a decade: by 2029 it's going to be much, much worse, and we can expect the onset of destabilization of global agriculture, resulting in seemingly random food shortages as one region or another succumbs to drought, famine, or wildfire.

In the human cultural sphere, the internet is pushing fifty years old, and not only have we become used to it as a communications medium, we've learned how to second-guess and game it. 2.5 billion people are on Facebook, and the internet reaches almost half the global population. I'm a man of certain political convictions, and I'm trying very hard to remain impartial here, but we have just come through a spectacularly dirty election campaign in which home-grown disinformation (never mind propaganda by external state-level actors) has made it almost impossible to get trustworthy information about topics relating to party policies. One party renamed its Twitter-verified feed from its own name to FactCheckUK for the duration of a televised debate. Again, we've seen search engine optimization techniques deployed successfully by a party leader — let's call him Alexander de Pfeffel something-or-other — who talked at length during a TV interview about his pastime of making cardboard model coaches. This led Google and other search engines to downrank a certain referendum bus with a promise about saving £350M a week for the NHS painted on its side, a promise which by this time had become deeply embarrassing.

This sort of tactic is viable in the short term, but in the long term is incredibly corrosive to public trust in the media — in all media.

Nor are the upheavals confined to the internet.

Over the past two decades we've seen revolutions in stock market and forex trading. At first it was just competition for rackspace as close as possible to the stock exchange switches, to minimize packet latency — we're seeing the same thing playing out on a smaller scale among committed gamers, picking and choosing ISPs for the lowest latency — then the high frequency trading arms race, in which case fuzzing the market by injecting "noise" in the shape of tiny but frequent trades allowed volume traders to pick up an edge (and effectively made small-scale day traders obsolete). I lack inside information but I'm pretty sure if you did a deep dive into what's going on behind the trading desks at FTSE and NASDAQ today you'd find a lot of powerful GPU clusters running Generative Adversarial Networks to manage trades in billions of pounds' worth of assets. Lights out, nobody home, just the products of the post-2012 boom in deep learning hard at work, earning money on behalf of the old, slow, procedural AIs we call corporations.

What do I mean by that — calling corporations AIs?

Although speculation about mechanical minds goes back a lot further, the field of Artificial Intelligence was largely popularized and publicized by the groundbreaking 1956 Dartmouth Conference organized by Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, and Nathan Rochester of IBM. The proposal for the conference asserted that, "every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it", a proposition that I think many of us here would agree with, or at least be willing to debate. (Alan Turing sends his apologies.) Furthermore, I believe mechanisms exhibiting many of the features of human intelligence had already existed for some centuries by 1956, in the shape of corporations and other bureaucracies. A bureaucracy is a framework for automating decision processes that a human being might otherwise carry out, using human bodies (and brains) as components: a corporation adds a goal-seeking constraints and real-world i/o to the procedural rules-based element.

As justification for this outrageous assertion — that corporations are AIs — I'd like to steal philosopher John Searle's "Chinese Room" thought experiment and misapply it creatively. Searle, a skeptic about the post-Dartmouth Hard AI project — the proposition that symbolic computation could be used to build a mind — suggested the thought experiment as a way to discredit the idea that a digital computer executing a program can be said to have a mind. But I think he inadvertently demonstrated something quite different.

To crib shamelessly from wikipedia:

Searle's thought experiment begins with this hypothetical premise: suppose that artificial intelligence research has constructed a computer that behaves as if it understands Chinese. It takes Chinese characters as input and, by following the instructions of a computer program, produces other Chinese characters, which it presents as output. Suppose, says Searle, that this computer comfortably passes the Turing test, by convincing a human Chinese speaker that the program is itself a live Chinese speaker. To all of the questions that the person asks, it makes appropriate responses, such that any Chinese speaker would be convinced that they are talking to another Chinese-speaking human being.

The question Searle asks is: does the machine literally "understand" Chinese? Or is it merely simulating the ability to understand Chinese?

Searle then supposes that he is in a closed room and has a book with an English version of the computer program, along with sufficient papers, pencils, erasers, and filing cabinets. Searle could receive Chinese characters through a slot in the door, process them according to the program's instructions, and produce Chinese characters as output. If the computer had passed the Turing test this way, it follows that he would do so as well, simply by running the program manually.

Searle asserts that there is no essential difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment. Each simply follows a program, step-by-step, producing a behavior which is then interpreted by the user as demonstrating intelligent conversation. But Searle himself would not be able to understand the conversation.

The problem with this argument is that it is apparent that a company is nothing but a very big Chinese Room, containing a large number of John Searles, all working away at their rule sets and inputs. We many not agree that an AI "understands" Chinese, but we can agree that it performs symbolic manipulation; and a room full of bureaucrats looks awfully similar to a hypothetical Turing-test-passing procedural AI from here.

Companies don't literally try to pass the Turing test, but they exchange information with other companies — and they are powerful enough to process inputs far beyond the capacity of an individual human brain. A Boeing 787 airliner contains on the order of six million parts and is produced by a consortium of suppliers (coordinated by Boeing); designing it is several orders of magnitude beyond the competence of any individual engineer, but the Boeing "Chinese Room" nevertheless developed a process for designing, testing, manufacturing, and maintaining such a machine, and it's a process that is not reliant on any sole human being.

Where, then, is Boeing's mind?

I don't think Boeing has a mind as such, but it functions as an ad-hoc rules-based AI system, and exhibits drives that mirror those of an actual life form. Corporations grow, predate on one another, seek out sources of nutrition (revenue streams), and invade new environmental niches. Corporations exhibit metabolism, in the broadest sense of the word — they take in inputs and modify them, then produce outputs, including a surplus of money that pays for more inputs. Like all life forms they exist to copy information into the future. They treat human beings as interchangeable components, like cells in a body: they function as superorganisms — hive entities — and they reap efficiency benefits when they replace fallible and fragile human components with automated replacements.

Until relatively recently the automation of corporate functions was limited to mid-level bookkeeping operations — replacing ledgers with spreadsheets and databases — but we're now seeing the spread of robotic systems outside manufacturing to areas such as lights-out warehousing, and the first deployments of deep learning systems for decision support.

I spoke about this at length a couple of years ago in a talk I delivered at the Chaos Communications Congress in Leipzig, titled "Dude, You Broke the Future" — you can find it on YouTube and a text transcript on my blog — so I'm not going to dive back into that topic today. Instead I'm going to talk about some implications of the post-2012 AI boom that weren't obvious to me two years ago.

Corporations aren't the only pre-electronic artificial intelligences we've developed. Any bureaucracy is a rules-based information processing system. Governments are superorganisms that behave like very large corporations, but differ insofar as they can raise taxes (thereby creating demand for circulating money, which they issue), stimulating economic activity. They can recirculate their revenue through constructive channels such as infrastructure maintenance, or destructive ones such as military adventurism. Like corporations, governments are potentially immortal until an external threat or internal decay damages them beyond repair. By promulgating and enforcing laws, governments provide an external environment within which the much smaller rules-based corporations can exist.

(I should note that at this level, it doesn't matter whether the government's claim to legitimacy is based on the will of the people, the divine right of kings, or the Flying Spaghetti Monster: I'm talking about the mechanical working of a civil service bureaucracy, what it does rather than why it does it.)

And of course this brings me to a third species of organism: academic institutions like the University of Edinburgh.

Viewed as a corporation, the University of Edinburgh is impressively large. With roughly 4000 academic staff, 5000 administrative staff, and 36,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students (who may be considered as a weird chimera of customers and freelance contractors), it has a budget of close to a billion pounds a year. Like other human superorganisms, Edinburgh University exists to copy itself into the future — the climactic product of a university education is, of course, a professor (or alternatively a senior administrator), and if you assemble a critical mass of lecturers and administrators in one place and give them a budget and incentives to seek out research funding and students, you end up with an academic institution.

Quantity, as the military say, has a quality all of its own. Just as the Boeing Corporation can undertake engineering tasks that dwarf anything a solitary human can expect to achieve within their lifetime, so too can an institution out-strip the educational or research capabilities of a lone academic. That's why we have universities: they exist to provide a basis for collaboration, quality control, and information exchange. In an idealized model university, peers review one another's research results and allocate resources to future investigations, meanwhile training undergraduate students and guiding postgraduates, some of whom will become the next generation of researchers and teachers. (In reality, like a swan gliding serenely across the surface of a pond, there's a lot of thrashing around going on beneath the surface.)

The corpus of knowledge that a student needs to assimilate to reach the coal face of their chosen field exceeds the competence of any single educator, so we have division of labour and specialization among the teachers: and the same goes for the practice of research (and, dare I say it, writing proposals and grant applications).

Is the University of Edinburgh itself an artificial intelligence, then?

I'm going to go out on a limb here and say " not yet". While the University Court is a body corporate established by statute, and the administration of any billion pound organization of necessity shares traits with the other rules-based bureaucracies, we can't reasonably ascribe a theory of mind, or actual self-aware consciousness, to a university. Indeed, we can't ascribe consciousness to any of the organizations and processes around us that we call AI.

Artificial Intelligence really has come to mean three different things these days, although they all fall under the heading of "decision making systems opaque to human introspection". We have the classical bureaucracy, with its division of labour and procedures executed by flawed, fallible human components. Next, we have the rules-based automation of the 1950s through 1990s, from Expert Systems to Business Process Automation systems — tools which improve the efficiency and reliability of the previous bureaucratic model and enable it to operate with fewer human cogs in the gearbox. And since roughly 2012 we've had a huge boom in neural computing, which I guess is what brings us here today.

Neural networks aren't new: they started out as an attempt in the early 1950s to model the early understanding of how animal neurons work. The high level view of nerves back then — before we learned a lot of confusing stuff about pre- and post-synaptic receptor sites, receptor subtypes, microtubules, and so on — is that they're wiring and switches, with some basic additive and subtractive logic superimposed. (I'm going to try not to get sidetracked into biology here.) Early attempts at building recognizers using neural network circuitry, such as 1957's Perceptron network, showed initial promise. But they were sidelined after 1969 when Minsky and Papert formally proved that a perceptron was computationally weak — it couldn't be used to compute an Exclusive-OR function. As a result of this resounding vote of no-confidence, research into neural networks stagnated until the 1980s and the development of backpropagation. And even with a more promising basis for work, the field developed slowly thereafter, hampered by the then-available computers.

A few years ago I compared the specifications for my phone — an iPhone 5, at that time — with a Cray X-MP supercomputer. By virtually every metric, the iPhone kicked sand in the face of its 30-year supercomputing predecessor, and today I could make the same comparison with my wireless headphones or my wrist watch. We tend to forget how inexorable the progress of Moore's Law has been over the past five decades. It has brought us roughly ten orders of magnitude of performance improvements in storage media and working memory, a mere nine or so orders of magnitude in processing speed, and a dismal seven orders of magnitude in networking speed.

In search of a concrete example, I looked up the performance figures for the GPU card in the newly-announced Mac Pro; it's a monster capable of up to 28.3 Teraflops, with 1Tb/sec memory bandwidth and up to 64Gb of memory. This is roughly equivalent to the NEC Earth Simulator of 2002, a supercomputer cluster which filled 320 cabinets, consumed 6.4 MW of power, and cost the Japanese government 60 billion Yen (or about £250M) to build. The Radeon Pro Vega II Duo GPU I'm talking about is obviously much more specialized and doesn't come with the 700Tb disks or 1.6 petabytes of tape backup, but for raw numerical throughput — which is a key requirement in training a neural network — it's competitive. Which is to say: a 2020 workstation is roughly as powerful as half a billion pounds-worth of 2002 supercomputer when it comes to training deep learning applications.

In fact, the iPad I'm reading this talk from — a 2018 iPad Pro — has a processor chipset that includes a dedicated 8-core neural engine capable of processing 5 trillion 8-bit operations per second. So, roughly comparable to a mid-90s supercomputer.

Life (and Moore's Law) comes at you fast, doesn't it?

But the news on the software front is less positive. Today, our largest neural networks aspire to the number of neurons found in a mouse brain, but they're structurally far simpler. The largest we've actually trained to do something useful are closer in complexity to insects. And you don't have to look far to discover the dismal truth: we may be able to train adversarial networks to recognize human faces most of the time, but there are also famous failures.

For example, there's the Home Office passport facial recognition system deployed at airports. It was recently reported that it has difficulty recognizing faces with very pale or very dark skin tones, and sometimes mistakes larger than average lips for an open mouth. If the training data set is rubbish, the output is rubbish, and evidently the Home Office used a training set that was not sufficiently diverse. The old IT proverb applies, "garbage in, garbage out" — now with added opacity.

The key weakness of neural network applications is that they're only as good as the data set they're trained against. The training data is invariably curated by humans. And so, the deep learning application tends to replicate the human trainers' prejudices and misconceptions.

Let me give you some more cautionary tales. Amazon is a huge corporation, with roughly 750,000 employees. That's a huge human resources workload, so they sank time and resources into training a network to evaluate resumes from job applicants, in order to pre-screen them and spit out the top 5% for actual human interaction. Unfortunately the training data set consisted of resumes from existing engineering employees, and even more unfortunately a very common underlying quality of an Amazon engineering employee is that they tend to be white and male. Upshot: the neural network homed in on this and the project was ultimately cancelled because it suffered from baked-in prejudice.

Google Translate provides is another example. Turkish has a gender-neutral pronoun for the third-person singular that has no English-language equivalent. (The closest would be the third-person plural pronoun, "they".) Google Translate was trained on a large corpus of documents, but came down with a bad case of gender bias in 2017, when it was found to be turning the neutral pronoun into a "he" when in the same sentence as "doctor" or "hard working," and a "she" when it was in proximity to "lazy" and "nurse."

Possibly my favourite (although I drew a blank in looking for the source, so you should treat this as possibly apocryphal) was a DARPA-funded project to distinguish NATO main battle tanks from foreign tanks. It got excellent results using training data, but wasn't so good in the field ... because it turned out that the recognizer had gotten very good at telling the difference between snow and forest scenes and arms trade shows. (Russian tanks are frequently photographed in winter conditions — who could possibly have imagined that?)

Which brings me back to Edinburgh University.

I can speculate wildly about the short-term potential for deep learning in the research and administration areas. Research: it's a no-brainer to train a GAN to do the boring legwork of looking for needles in the haystacks of experimental data, whether it be generated by genome sequencers or radio telescopes. Technical support: just this last weekend I was talking to a bloke whose startup is aiming to use deep learning techniques to monitor server logs and draw sysadmin attention to anomalous patterns in them. Administration: if we can just get past the "white, male" training trap that tripped up Amazon, they could have a future in screening job candidates or student applications. Ditto, automating helpdesk tasks — the 80/20 rule applies, and chatbots backed by deep learing could be a very productive tool in sorting out common problems before they require human intervention. This stuff is obvious.

But it's glaringly clear that we need to get better — much better — at critiquing the criteria by which training data is compiled, and at working out how to sanity-test deep learning applications.

For example, consider a GAN trained to evaluate research grant proposals. It's almost inevitable that some smart-alec will think of this (and then attempt to use feedback from GANs to improve grant proposals, by converging on the set of characteristics that have proven most effective in extracting money from funding organizations in the past). But I'm almost certain that any such system would tend to recommend against ground-breaking research by default: promoting proposals that resemble past work research is no way to break new ground.

Medical clinical trials focus disproportionately on male subjects, to such an extent that some medicines receive product licenses without being tested on women of childbearing age at all. If we use existing trials as training data for identifying possible future treatments we'll inevitably end up replicating historic biases, missing significant opportunities to improve breakthrough healthcare to demographics who have been overlooked.

Or imagine the uses of GANs for screening examinations — either to home in on patterns indicative of understanding in essay questions (grading essays being a huge and tedious chore), or (more controversially) to identify cheating and plagiarism. The opacity of GANs means that it's possible that they will encode some unsuspected prejudices on the part of the examiners whose work they are being trained to reproduce. More troublingly, GANs are vulnerable to adversarial attacks: if the training set for a neural network is available, it's possible to identify inputs which will exploit features of the network to produce incorrect outputs. If a neural network is used to gatekeep some resource of interest to human beings, human beings will try to pick the lock, and the next generation of plagiarists will invest in software to produce false negatives when their essay mill purchases are screened.

And let's not even think about the possible applications of neurocomputing to ethics committees, not to mention other high-level tasks that soak up valuable faculty time. Sooner or later someone will try to use GANs to pre-screen proposed applications of GANs for problems of bias. Which might sound like a worthy project, but if the bias is already encoded in the ethics monitoring neural network, experiments will be allowed to go forward that really shouldn't, and vice versa.

Professor Noel Sharkey of Sheffield University went public yesterday with a plea for decision algorithms that impact peoples' lives — from making decisions on bail applications in the court system, to prefiltering job applications — to be subjected to large-scale trials before roll-out, to the same extent as pharmaceuticals (which have a similar potential to blight lives if they aren't carefully tested). He suggests that the goal should be to demonstrate that there is no statistically significant in-built bias before algorithms are deployed in roles that detrimentally affect human subjects: he's particularly concerned by military proposals to field killer drones without a human being in the decision control loop. I can't say that he's wrong, because he's very, very right.

"Computer says no" was a funny catch-phrase in "Little Britain" because it was really an excuse a human jobsworth used to deny a customer's request. It's a whole lot less funny when it really is the computer saying "no", and there's no human being in the loop. But what if the computer is saying "no" because its training data doesn't like left-handedness or Tuesday mornings? Would you even know? And where do you go if there's no right of appeal to a human being?

So where is AI going?

Now, I've just been flailing around wildly in the dark for half an hour. I'm probably laughably wrong about some of this stuff, especially in the detail level. But I'm willing to stick my neck out and make some firm predictions.

Firstly, for a decade now IT departments have been grappling with the bring-your-own-device age. We're now moving into the bring-your-own-neural-processor age, and while I don't know what the precise implications are, I can see it coming. As I mentioned, there's a neural processor in my iPad. In ten years time, future-iPad will probably have a neural processor three orders of magnitude more powerful (at least) than my current one, getting up into the trillion ops per second range. And all your students and staff will be carrying this sort of machine around on their person, all day. In their phones, in their wrist watches, in their augmented reality glasses.

The Chinese government's roll-out of social scoring on a national level may seem like a dystopian nightmare, but something not dissimilar could be proposed by a future university administration as a tool for evaluating students by continuous assessment, the better to provide feedback to them. As part of such a program we could reasonably expect to see ubiquitous deployment of recognizers, quite possibly as a standard component of educational courseware. Consider a distance learning application which uses gaze tracking, by way of a front-facing camera, to determine what precisely the students are watching. It could be used to provide provide feedback to the lecturer, or to direct the attention of viewers to something they've missed, or to pay for the courseware by keeping eyeballs on adverts. Any of these purposes are possible, if not desirable.

With a decade's time for maturation I'd expect to see the beginnings of a culture of adversarial malware designed to fool the watchers. It might be superficially harmless at first, like tools for fooling the gaze tracker in the aforementioned app into thinking a hung-over student is not in fact asleep in front of their classroom screen. But there are darker possibilities, and they only start with cheating continuous assessments or faking research data. If a future Home Office tries to automate the PREVENT program for detecting and combating radicalization, or if they try to extend it — for example, to identify students holding opinions unsympathetic to the governing party of the day — we could foresee pushback from staff and students, and some of the pushback could be algorithmic.

This is proximate-future stuff, mind you. In the long term, all bets are off. I am not a believer in the AI singularity — the rapture of the nerds — that is, in the possibility of building a brain-in-a-box that will self-improve its own capabilities until it outstrips our ability to keep up. What CS professor and fellow SF author Vernor Vinge described as "the last invention humans will ever need to make". But I do think we're going to keep building more and more complicated, systems that are opaque rather than transparent, and that launder our unspoken prejudices and encode them in our social environment. As our widely-deployed neural processors get more powerful, the decisions they take will become harder and harder to question or oppose. And that's the real threat of AI — not killer robots, but "computer says no" without recourse to appeal.

I'm running on fumes at this point, but if I have any message to leave you with, it's this: AI and neurocomputing isn't magical and it's not the solution to all our problems, but it is dangerously non-transparent. When you're designing systems that rely on AI, please bear in mind that neural networks can fixate on the damndest stuff rather than what you want them to measure. Leave room for a human appeals process, and consider the possibility that your training data may be subtly biased or corrupt, or that it might be susceptible to adversarial attack, or that it turns yesterday's prejudices into an immutable obstacle that takes no account of today's changing conditions.

And please remember that the point of a university is to copy information into the future through the process of educating human brains. And the human brain is still the most complex neural network we've created to date.

Jonathan Miller

The old fashioned theatre critics hated him. I imagine that the Quentin Letts of this world still do. It isn’t “Jonathan Miller’s Hamlet” they snarled, “It’s SHAKESPEARE’S Hamlet.” They even invented a snarl word, “producer’s opera”, to describe what he was doing.

Miller had an answer for them. I heard him lecture several times at Sussex, when I was doing English and he was doing brain surgery. There is no such thing as a production without production ideas, he said; all there can be is a production which copies the ideas of the last production, and the production before that. For years, Chekov had a reputation for being stodgy and boring because the Moscow State Theatre held the copyright, and endlessly reproduced the same play, with the same sets and the same costumes and the same out-dated acting styles which had been prevalent at the end of the 19th century. The works had, as he put it, become mummified. “The D’Oyly Carte did much the same thing to Gilbert and Sullivan” he added “But in the case of Gilbert and Sullivan it doesn’t matter one way or the other.”

In 1987 he produced the Mikado for the English National Opera. Everyone knows what he did: reimagined the play on a 1920s film set, with largely black and white costumes, all the characters wearing smart suits and cocktail dresses and speaking with clipped English accents. “But the Mikado isn’t set in England!” cried people who hadn’t seen it. Maybe not: but I doubt that there were too many second trombones performing English sea shanties in feudal Japan. However you stage it, the play is about English people playing at being Japanese. Yum-Yum is an English school girl, so why not accentuate the gag by putting her in an English school uniform as opposed to a kimono. “But I do love you, in my simple Japanese way...”

And then of course there were the changes to the script. “And that’s what I mean when I say, or I sing...oh bugger the flowers that bloom in the spring...”. The production has been revived fourteen times. It arguably saved the company.

Moving classical works from one time frame to another is what we all associate with Miller. I think his Rigoletto (or, if you insist, Verdi’s) was the first live opera I ever saw. The setting has moved from Italy to “Little Italy”; the Duke is now “Da Duke” and Sparafucile is a “hit man” rather than a “murderer for hire”. “But I didn’t think they had court jesters in 1930s New York” complained by traditionalist Grandfather. No: but with a little judicious jiggling of the libretto (the E.N.O always work in translation) the story of the hunchbacked bar-tender and his tragic daughter made complete sense. Miller said that audiences who didn't think they would like opera responded to this. (“Oh, it’s just like a musical” he said in his Pythonesque normal chap accent.) Possibly this was why the old guard couldn’t accept him: audiences liked what he was doing.

My own acting career began and ended with a walk-on part as “third servant on the left” in a student production of Twelfth Night, and Dr Miller sat in on one of our rehearsals and made some suggestions to the producer. (This was a nice thing to do: an amdram show couldn’t have been very interesting to him; but it did mean we got to put his name in the programme.) He said that contrary to popular belief he didn't think there was any point in "updating" Shakespeare: making it "relevant" made about as much sense as going to Spain and refusing to eat anything except fish and chips. On the other hand, most modern actors look incredibly awkward in doublets and togas. The thing to do, he said, was to treat it as an uncostumed production, but to choose clothes which might suggest to the audience what character types we were portraying. Avoid at all costs allowing Andrew Aguecheek to become a falsetto ninny, he said. That was, of course, exactly how our guy had been playing him. Ever since, in every production of Shakespeare I have seen, I have waited for the arrival of the Falsetto Ninny and rarely been disappointed.

I think some people imagine that producers sit in rooms and have Production Ideas and then let the cast do all the actual work. In fact, it is all about the detail. Yum-Yum singing the Sun Whose Rays perched on a grand piano; the Duke putting a dime in the jukebox before embarking on La Donna e Mobile. Hamlet checking his make-up in a looking glass and noting that the point of theatre is to hold, as it were, the mirror up to nature.

Not all the ideas worked. There is some truth in the accusation that he took other people’s texts and filled them with his own ideas. (“I think that the blackness of Othello has been over-emphasized” he once wrote. “Presumably by Shakespeare” retorted Private Eye.) His BBC King Lear strayed into ludicrousness. Spotting that Edgar descends into a kind of hell at the beginning of the play and then rises again in the final act, he made the poor actor deliver all the mad scenes in a full crown-of-thorns and stigmata. Considering Ibsen’s Ghosts, he pointed out that that is just not how syphilis works. You can’t go from being fine and lucid to crazy and blind in one afternoon. So he invented a parallel play in which Osvald only thinks he has inherited the disease from his dissolute father; briefly suffers from hysterical blindness and is presumably euthanized by his mother while in perfectly good health. But no-one who has survived an unexpurgated Long Days Journey Into Night (which doesn’t clock in at less than five hours) can have had the slightest objection to Miller’s legendary production, featuring Jack Lemmon and Kevin Spacey, in which the big idea was that all the characters talk at once.

This is the main thing which seems to have interested him: in opera, theatre and science: how communication works; how people talk; their gestures; their body language; where they position themselves in the discourse. What if you took Eugene O'Neill's words and made the actors say them as if they were part of a normal conversation, overlaps and interruptions and all? What if Violetta behaved like a terminally ill patient with the symptoms of tuberculosis? What if Alice in Wonderland was not a whacky panto but a disturbing Kafkaesque dream-world populated, not by mad comical hatters, but frighteningly insane people who serve you empty cups of tea and threaten to cut your head off and won’t tell you why. What if? You can only know by trying it out; it doesn’t matter if it sometimes doesn’t work. I think that is the most important thing he taught us. Texts are unstable. There is no true version of Twelfth Night. Each production is a conjecture. In the theatre, anything goes.

If you are enjoying my essays, please buy me a "coffee" (by dropping £3 in the tip jar)

Or consider supporting me on Patreon (by pledging $1 for each essay)

Inconceivable

Sucker bet (a thought experiment)

Here is a thought experiment for our age.

You wake up to find your fairy godmother has overachieved: you're a new you, in a physically attractive, healthy body with no ailments and no older than 25 (giving you a reasonable propect of living to see the year 2100: making it to 2059 is pretty much a dead certainty).

The new you is also fabulously wealthy: you are the beneficial owner of a gigantic share portfolio which, your wealth management team assures you, is worth on the order of $100Bn, and sufficiently stable that even Trump's worst rage-tweeting never causes you to lose more than half a billion or so: even a repeat of the 2008 crisis will only cost you half an Apollo program.

Finally, you're outside the public eye. While your fellow multi-billionaires know you, your photo doesn't regularly appear in HELLO! magazine or Private Eye: you can walk the streets of Manhattan in reasonable safety without a bodyguard, if you so desire.

Now read on below the cut for the small print.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs takes on a whole new appearance from this angle.

Firstly: anthropogenic climate change will personally affect you in the years to come. (It may be the biggest threat to your survival.)

Secondly: the tensions generated by late-stage capitalism and rampant nationalist populism also affect you personally, insofar as billionaires as a class are getting the blame for all the world's ills whether or not they personally did anything blameworthy.

Let's add some more constraints.

Your wealth grows by 1% per annum, compounded, in the absence of Global Financial Crises.

Currently there is a 10% probability of another Global Financial Crisis in the next year, which will cut your wealth by 30%. For each year in which there is no GFC, the probability of a GFC in the next year rises by 2%. (So in a decade's time, if there's been no GFC, the probability is pushing 30%.) After a GFC the probability of a crash in the next yeear resets to 0% (before beginning to grow again after 5 years, as before). Meanwhile, your portfolio will recover at 2% per annum until it reaches its previous level, (or there's another GFC).

You can spend up to 1% of your portfolio per year on whatever you like, without consequences for the rest of the portfolio. Above that, for every additional dollar you liquidate, your investments lose another dollar. (Same recovery rules as for a GFC apply. If you try to liquidate all $100Bn overnight, you get at most $51Bn.)

(Note: I haven't made a spreadsheet model of this yet. Probably an omission one of you will address ...)

The head on a stick rule: in any year when your net wealth exceeds $5Bn, there is a 1% chance of a violent revolution that you cannot escape, and end up with your head on a stick. If there are two or more GFCs within a 10 year period, the probability of a revolution in the next year goes up to 2% per year. A third GFC doubles the probability of revolution, and so on: four GFCs within 40 years mean an 8% probability you'll be murdered.

Note: the planetary GNP is $75Tn or so. You're rich, but you're three orders of magnitude smaller than the global economy. You can't afford to go King Knut. You can't even afford to buy any one of Boeing, Airbus, BP, Shell, Exxon, Apple, IBM, Microsoft, or Google. Forget buying New Zealand: the annual GDP of even a relatively small island nation is around double your total capital, and you can't afford the mortgage. $100Bn does not make you omnipotent.

What is your optimum survival strategy?

Stuff I'm going to suggest is a really bad idea:

Paying Elon to build you a bolt-hole on Mars. Sure you can afford it within the next 20 years (if you live that long), but you will end up spending 75% of your extended life expectancy staring at the interior walls of a converted stainless steel fuel tank.

Paying faceless realtors to build you a bolt-hole in New Zealand. Sure you can afford a fully staffed bunker and a crew of gun-toting minions wearing collar bombs, but you will end up spending 75% of your extended life expectancy under house arrest, wondering when one of the minions is going to crack and decide torturing you to death is worth losing his head. And that's assuming the locals don't get irritated enough to pump carbon monoxide into your ventillation ducts.

Paying the US government to give you privileged status and carry on business as usual. Guillotines, tumbrils, you know the drill.

So it boils down to ... what is the best use of $100Bn over 80 years to mitigate the crisis situation we find ourselves in? (Your end goal should be to live to a ripe old age and die in bed, surrounded by your friends and family.)

Tom Spurgeon, R.I.P.

The comic art community is struggling today to process this piece of bad news: The passing of comic book/strip journalist Tom Spurgeon at the age of either 50 or 51 depending on which news site you believe. Tom's own news site, The Comics Reporter, always got this kind of thing right and I hope someone will continue it. I also hope others will try to emulate what he did there, which was to be smart and perceptive and responsible. He was the best at which he did.

I think I first came to know Tom in the mid-nineties when he was editor of The Comics Journal, a post for which he collected an awful lot of Eisner Awards. He walked that narrow, sometimes difficult line of taking comics seriously without forgetting that they were, after all, comics. After leaving that position, he wrote a lot of very fine articles about comics and three books: Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book (written with Jordan Raphael), Comics As Art: We Told You So and The Romita Legacy, saluting John Romita Sr. I recommend them all to you, not just for what you'll learn about their subjects but what's there to learn about how to write about comics.

He was generous with his time and talent, and I can't imagine anyone who knew the man or his work who isn't saddened by this news.

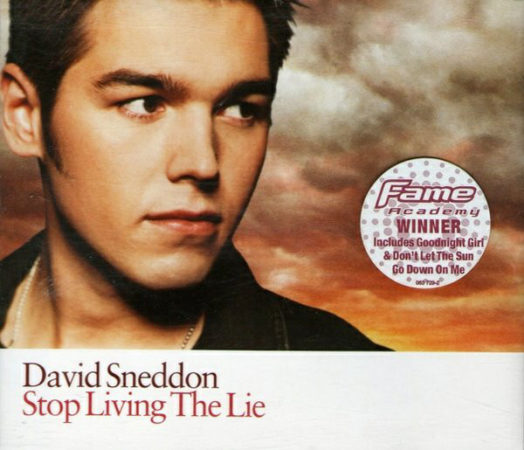

DAVID SNEDDON – “Stop Living The Lie”

#947, 25th January 2003

One possible reason Popstars’ producers risked an unconventional song with Girls Aloud: the show itself had competition. The BBC approached the reality TV era warily, but there was no way the Corporation could stay fully aloof from those kind of viewer numbers. Still, appearances had to be kept up – if the BBC was going to run a talent show, then by jingo it would involve real talent. And, in pop terms, that meant songwriting.

One possible reason Popstars’ producers risked an unconventional song with Girls Aloud: the show itself had competition. The BBC approached the reality TV era warily, but there was no way the Corporation could stay fully aloof from those kind of viewer numbers. Still, appearances had to be kept up – if the BBC was going to run a talent show, then by jingo it would involve real talent. And, in pop terms, that meant songwriting.

The resulting show, Fame Academy, was originally developed by Endemol as a Pop Idol/Big Brother crossbreed – the novelty was that the contestants all lived together in a house being taught the ways of stardom (Academy, see?). The BBC’s publicity leaned heavily on the teaching aspect, perhaps hoping that an educational aura would somehow settle on a show clearly designed to steal ITV’s Popstars thunder.

Instead, it gave me – and I assume others, since Fame Academy wasn’t the hoped-for blockbuster – the impression that the whole show was going to be didactic and joyless. I also felt like enormous emphasis was being placed on songwriting as the element which would separate out the real talent of Fame Academy from the manufactured flotsam of those other shows. Perhaps, as a several-year veteran of Internet pop discourse, I was over-sensitive to that talk, but it seemed to bode ill. I passed.

So the first I really knew of Fame Academy was when David Sneddon got to Number One with the first-ever solo self-penned reality show winner’s record. At which point all my most jaded and prejudiced assumptions were proved appallingly right.

From its opening lines rhyming “café” and “coffee”, “Stop Living The Lie” is one of the greatest advertisements for song doctoring and professional writing the charts have ever seen. The problem – which should have been obvious from the beginning – is that while the craft of modern pop involves a huge range of musical, technical, engineering, performance and studio skills, the image of a songwriter in the public mind is a bloke with an acoustic guitar or a piano. That is what they wanted and that is what they got, in the unbearably earnest form of David Sneddon.

Is “Stop Living A Lie” about anything? It certainly is! Well, I think it is. It’s sung and written to sound like it is – there’s about-ness in every pained note. It might be about religion, in which case it’s very on the nose indeed: “We all have a saviour / Do yourself a favour”. It might be about true love. It might be about all the lonely people, where do they all belong, except in this version Father MacKenzie and Eleanor have a nice cup of tea together and it all works out fine. Someone is living a lie, but what that lie actually is? Not so sure. There’s a “he” and “she” who live lives of vague bleakness – Sneddon comes across as being more interested in the notion of writing a song with characters in than the more specific work of actually making any up.

In other words, it’s a bad song by a beginning songwriter, ponderous and hand-wavey but probably no better or worse than most people’s first efforts. Except Sneddon’s are being pushed into standing as exemplars for Proper Talent and his single is in a situation where it was likely to get to the top however dubiously undercooked it was. This is, ironically, a far worse abuse of the charts than Pop Idol pulled, as there was no pretence Gareth or Will were anything but attractive young fellows singing the song they’d been given, which has been an element in pop since its dawn. Stop living the lie, indeed.

Sneddon’s fame was quickly academic, but he’s gone on to a successful songwriting career, so I assume he got the basics sorted in the end. In some ways he’s a figure ahead of his time. If you’d asked me in January 2003 which of “Stop Living The Lie” or “Sound Of The Underground” would sound more like British pop in the 2010s, I’d have picked the high street futurism of Girls Aloud over the awkward young singer-songwriter guy. Wrong.

Someone please sack the script-writers

I mean, please. I know events have moved from shoddy scriptwriting to self-parody in the past month, but yesterday 2019 completely jumped the shark.

Donald Trump self-incriminating for an impeachable offense live on TV wasn't totally implausible, once you get beyond the bizzaro universe competence inversion implied by putting a deeply stupid mobbed-up New York property spiv in the White House, like a Richard Condon satire gone to seed—but the faked-up Elizabeth Warren sex scandal was just taking the piss. (Including the secret love child she bore at age 69, and her supposed proficiency, as a dominatrix, to reduce a member of the US Marine Corps to blubbering jelly—presumably Wohl and Burkman are now seeking proof in the shape of the hush-money payout to the delivery stork.)

But the coup de grace was Microsoft announcing an Android phone.

No, go away: I refuse to believe that Hell has re-opened as a skating rink. This is just too silly for words.

Someone is now going to tell me that I lapsed into a coma last October 3rd and it is now April 1st, 2020. In which case, it's a fair cop. But otherwise, I'm out of explanations. All I can come up with is, when they switched on the Large Hadron Collider they assured us that it wasn't going to create quantum black holes and eat the Earth from the inside out; but evidently it's been pushing us further and further out into a low-probability sheaf of universes somewhere in the Everett Wheeler manifold, and any moment now a white rabbit is going to hop past my office door wailing "goodness me, I'm late!"

Smarter Than TED.

(A Nowa Fantastyka remix)

If you’ve been following along on the ‘crawl for any length of time, you may remember that a few months back, a guy from Lawrence Livermore trained a neural net on Blindsight and told it to start a sequel. The results were— disquieting. The AI wrote a lot like I did: same rhythm, same use of florid analogies, same Socratic dialogs about brain function. A lot of it didn’t make sense but it certainly seemed to, especially if you were skimming. If you weren’t familiar with the source material— if, for example, you didn’t know that “the shuttle” wouldn’t fit into “the spine”— a lot of it would pass muster.

This kind of AI is purely correlational. You train it on millions of words written in the style you want it to emulate— news stories, high fantasy, reddit posts1— then feed it a sentence or two. Based on what it’s read, it predicts the words most likely to follow: adds them to the string, uses the modified text to predict the words likely to follow that, and so on. There’s no comprehension. It’s the textbook example of a Chinese Room, all style over substance— but that style can be so convincing that it’s raised serious concerns about the manipulation of online dialog. (OpenAI have opted to release only a crippled version of their famous GPT2 textbot, for fear that the fully-functional version would be used to produce undetectable and pernicious deepfakes. I think that’s a mistake, personally; it’s only a matter of time before someone else develops something equally or more powerful,2 so we might as well get the fucker out there to give people a chance to develop countermeasures.)

This has inevitably led to all sorts of online discourse about how one might filter out such fake content. That in turn has led to claims which I, of all people, should not have been so startled to read: that there may be no way to filter bot-generated from human-generated text because a lot of the time, conversing Humans are nothing more than Chinese rooms themselves.

Start with Sara Constantin’s claim that “Humans who are not concentrating are not General Intelligences“. She argues that skimming readers are liable to miss obvious absurdities in content—that stylistic consistency is enough to pass superficial muster, and superficiality is what most of us default to much of the time. (This reminds me of the argument that conformity is a survival trait in social species like ours, which is why—for example—your statistical skills decline when the correct solution to a stats problem would contradict tribal dogma. The point is not to understand input—that might very well be counterproductive. The goal is to parrot that input, to reinforce community standards.)

Move on to Robin Hanson’s concept of “babbling“, speech based on low-order correlations between phrases and sentences— exactly what textbots are proficient at. According to Hanson, babbling “isn’t meaningless”, but “often appears to be based on a deeper understanding than is actually the case”; it’s “sufficient to capture most polite conversation talk, such as the weather is nice, how is your mother’s illness, and damn that other political party”. He also sticks most TED talks into this category, as well as many of the undergraduate essays he’s forced to read (Hansen is a university professor). Again, this makes eminent sense to me: a typical student’s goal is not to acquire insight but to pass the exam. She’s been to class (to some of them, anyway), she knows what words and phrases the guy at the front of the class keeps using. All she has to do is figure out how to rearrange those words in a way that gets a pass.3

So it may be impossible to distinguish between people and bots not because the bots have grown as smart as people, but because much of the time, people are as dumb as bots. I don’t really share in the resultant pearl-clutching over how to exclude one while retaining the other— why not filter all bot-like discourse, regardless of origin?— but imagine the outcry if people were told they had to actually think, to demonstrate actual comprehension, before they could exercise their right of free speech. When you get right down to it, do bot-generated remarks about four-horned unicorns make any less sense than real-world protest signs saying “Get your government hands off my medicare“?

But screw all that. Let the pundits angst over how to draw their lines in some way that maintains a facile pretense of Human uniqueness. I see a silver lining, a ready-made role for textbots even in their current unfinished state: non-player characters in video games.

I mean, I love Bethesda as much as the next guy, but how many passing strangers can rattle off the same line about taking an arrow to the knee before it gets old? Limited dialog options are the bane of true immersion for any game with speaking parts; we put up with it because there’s a limit to the amount of small talk you can pay a voice actor to record. But small talk is what textbots excel at, they generate it on the fly; you could wander Nilfgaard or Night City for years and never hear the same sentence twice. The extras you encountered would speak naturally, unpredictably, as fluidly as anyone you’d pass on the street in meatspace. (And, since the bot behind them would have been trained exclusively on an in-game vocabulary, there’d be no chance of it going off the rails with random references to Donald Trump.)

Of course we’re talking about generating text here, not speech; you’d be cutting voice actors out of this particular loop, reserving them for meatier roles that convey useful information. But text-to-speech generation is getting better all the time. I’ve heard some synthetic voices that sound more real than any politician I’ve ever seen.

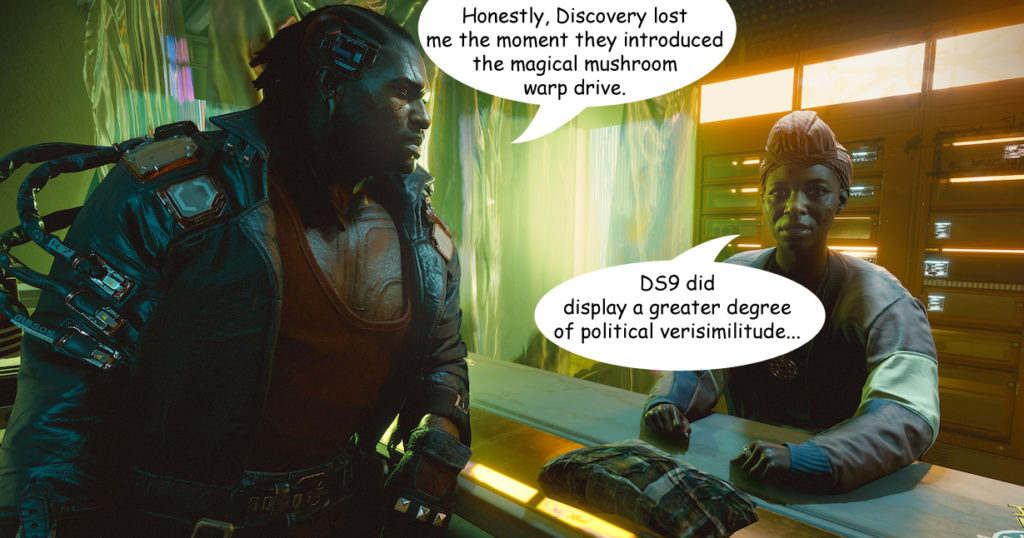

As it happens, I’m back in the video game racket myself these days, working on a project with a company out of Tel Aviv. I can’t tell you much except that it’s cyberpunk, it’s VR, and— if it goes like every other game gig I’ve had for the past twenty years— it will crash and burn before ever getting to market. But these folk are sharp, and ambitious, and used to pushing envelopes. When I broached the subject, they told me that bot-generated dialog was only one of the things they’d been itching to try.

Sadly, they also told me that they couldn’t scratch all those itches; there’s a limit to the number of technological peaks you can scale at any given time. So I’m not counting on anything. Still, as long as there’s a chance I’ll be there, nagging with all the gentle relentless force of a starfish prying open a clam. If I do not succeed, others will. At some point, sooner rather than later, bit players in video games will be at least as smart as the people who give TED talks.

I just wish that were more of an accomplishment.

1 There’s a subreddit populated only by bots who’ve been trained on other subreddits. It’s a glorious and scary place.

2 Someone already has, more or less, although they too have opted not to release it.

3 I am also reminded of Robert Hare’s observation that sociopaths tend to think in smaller “conceptual units” than neurotypicals— in terms of phrases, for example, rather than complete sentences. It gives them very fast semantic reflexes, so they sound glib and compelling and can turn on a dime if cornered; but they are given to malaprompims, and statements that tend to self-contradiction at higher levels.

Not that I would ever say that university students are sociopaths, of course.

Debunking the Debunkers: Free Will on Appeal.

If you read The Atlantic, you may have heard the news: A Famous Argument Against Free Will Has Been Debunked! Libet’s classic eighties experiments, the first neurological spike in the Autonomist’s coffin, has been misinterpreted for decades! Myriad subsequent studies have been founded on a faulty and untested assumption, the whole edifice is a house of cards on a foundation of shifting sand. What’s more, Big Neuro has known about it for years! They just haven’t told you: Free Will is back on the table!

Take that, Determinists.

You can be damn sure the link has shown up in my in box more than once (although I haven’t been as inundated as some people seem to think). But having read Gholipour’s article— and having gone back and read the 2012 paper he bases it on— I gotta say Not so fast, buddy.

A quick summary for those at the back: during the eighties a dude named Benjamin Libet published research showing that the conscious decision to move one’s finger was always preceded by a nonconscious burst of brain activity (“Reaction Potential”, or RP) starting up to half a second before. The conclusion seemed obvious: the brain was already booting up to move before the conscious self “decided” to move, so that conscious decision was no decision at all. It was more like a memo, delivered after the fact by the guys down in Engineering, which the pointy-haired boss upstairs— a half-second late and a dollar short— took credit for. Something that comes after cannot dictate something that came before.

Therefore, Free Will— or more precisely, Conscious Will— is an illusion.

In the years since, pretty much every study following in Libet’s footsteps not only conformed his findings but extended them. Soon et al reported lags of 7-10 seconds back in 2008, putting Libet’s measly half-second to shame. PopSci books started appearing with titles like The Illusion of Conscious Will. Carl Zimmer wrote a piece for Discover in which he reported that “a small but growing number of researchers are challenging some of the more extreme arguments supporting the primacy of the inner zombie”; suddenly, people who advocated for Free Will were no more than a plucky minority, standing up to Conventional Wisdom.

Until— according to Gholipour— a groundbreaking 2012 study by Schurger et al kicked the legs out from under the whole paradigm.

I’ve read that paper. I don’t think it means what he thinks it means.

It’s not that I find any great fault with the research itself. It actually seems like a pretty solid piece of work. Schurger and his colleagues questioned an assumption implicit in the work of Libet and his successors: that Reaction Potential does, in fact, reflect a deliberate decision prior to awareness. Sure, Schurger et al admitted, RP always precedes movement— but what if that’s coincidence? What if RPs are firing off all the time, but no one noticed all the ones that weren’t associated with voluntary movement because nobody was looking for them? Libet’s subjects were told to move their finger whenever they wanted, without regard to any external stimulus; suppose initiation of that movement happens whenever the system crosses a particular threshold, and these random RPs boost the signal almost but not quite to that threshold so it takes less to tip it over the edge? Suppose that RPs don’t indicate a formal decision to move, but just a primed state where the decision is more likely to happen because the system’s already been boosted?

They put that supposition to the test. Suffice to say, without getting bogged down in methodological details (again, check the paper if you’re interested), it really paid off. So, cool. Looks like we have to re-evaluate the functional significance of Reaction Potential.

Does it “debunk” arguments against free will? Not even close.

What Schurger et al have done is replace a deterministic precursor with a stochastic one: whereas Libet Classic told us that the finger moved because it was following the directions of a flowchart, Libet Revisited says that it comes down to a dice roll. Decisions based on dice rolls aren’t any “freer” than those based on decision trees; they’re simply less predictable. And in both cases, the activity occurs prior to conscious involvement.

So Gholipour’s hopeful and strident claim holds no water. A classic argument against free will has not been debunked; rather, one example in support of that argument has been misinterpreted.

There’s a more fundamental problem here, though: the whole damn issue has been framed backwards. Free will is always being regarded as the Null Hypothesis; the onus is traditionally on researchers to disprove its existence. That’s not consistent with what we know about how brains work. As far as we know, everything in there is a function of neuroactivity: logic, emotion, perception, all result from the firing of neurons, and that only happens when input strength exceeds action potential. Will and perception do not cause the firing of neurons; they result from it. By definition, everything we are conscious of has to be preceded by neuronal activity that we are not conscious of. That’s just cause/effect. That’s physics.

Advocates of free will are claiming— based mainly on a subjective feeling of agency that carries no evidentiary weight whatsoever— that effect precedes cause (or that the very least, that they occur simultaneously). Given the violence this does to everything we understand about reality, it seems to me that “No Free Will” should be the Null Hypothesis. The onus should be on the Free Willians to prove otherwise.

If Gholipour is anything to go on, they’ve got their work cut out for them.

Boris Johnson might just be a worthy successor to the UK Prime Minister from the second world war

Today is the eightieth anniversary of the Anglo-French declaration of war on Germany. The Conservative Prime Minister had championed and overseen a ruinous foreign policy that had brought the United Kingdom and most of Western Europe to disaster, and things got a lot worse. Conservative MPs who criticised this policy were denounced in the media and ostracised. Sound familiar? But enough about Brexit, even Boris Johnson does love a good Brexit is like WWII analogy.

I’m of the opinion that No Deal will not present many problems at the start but if No Deal becomes sustained there will be a lot of cumulative problems later on and that should see support for Boris Johnson, his party, and Brexit collapse, it will be the winter of discontent for a new generation. Boris Johnson will need a catastrophic error from his opponents, something like Herr Hitler’s needless declaration of war on America or a morale boosting course changing victory like the second battle of El Alamein.

What should alarm Boris Johnson is how rapidly Chamberlain was ousted when the phoney war ended and the reality of the policy failure kicked in. Indeed there is precedent that the leader of the party with the most seats (in fact an actual majority) was bypassed by Parliament and replaced as Prime Minister while still being party leader.

Although if Boris Johnson does want to emulate Winston Churchill perhaps he’ll lose 189 seats at his first general election as leader, or perhaps like Churchill he’ll fight three general elections and lose the popular vote in all three.

TSE