Source - Comics RSS - Patreon

Wine is a program to run Windows applications on a Unix PC.

Running Wine on Windows has been a fever dream of those responding to the siren call of "we do what we must, because we shouldn't" since at least 2004, when someone tried compiling Wine in Cygwin and trashed the registry of the host system.

The excuse is "what about ancient applications that don't run properly in recent Windows." But you know the real reason is "I suffered for my art, now it's your turn."

In late 2008, I got a bug in my brain and (I think it was me) started the WineOnWindows page on the Wine wiki. Summary: it was bloody impossible as things stood — going via Cygwin, MinGW or Windows Services for Unix. The current page isn't much more successful.

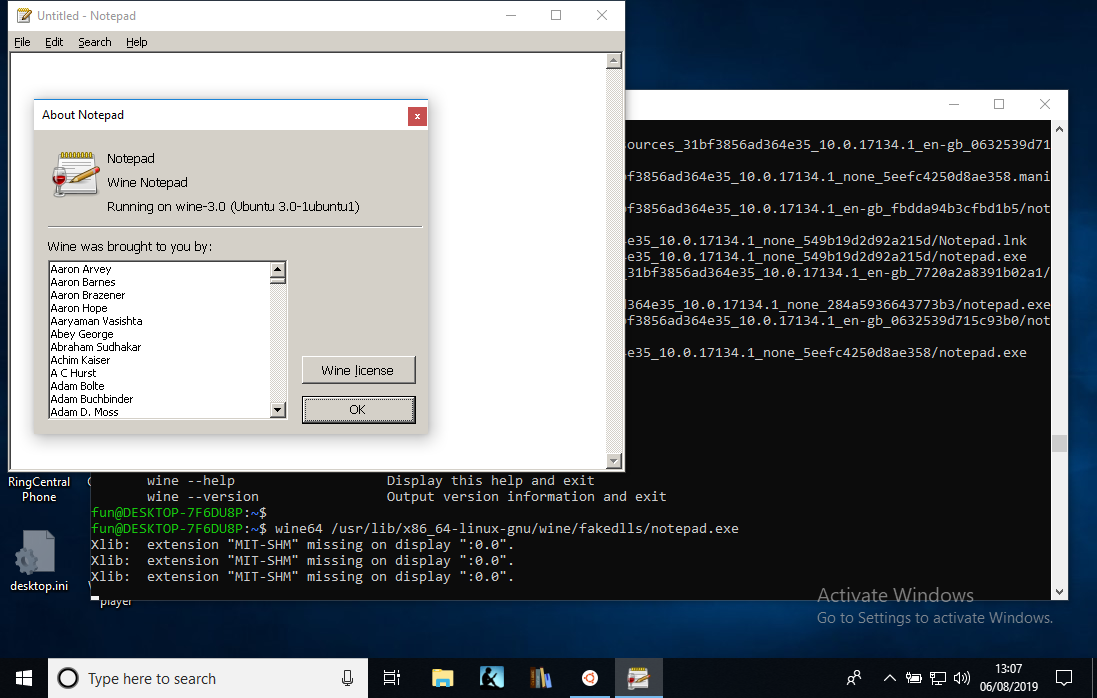

Windows 10 introduced Windows Subsystem for Linux — and the convenience of Ubuntu downloadable from the Microsoft Store. This makes this dumb idea pretty much Just Work out of the box, apart from having to set your DISPLAY environment variable by hand.

So far, it's mindbogglingly useless. It can only run 64-bit Windows apps, which doesn't even include all the apps that come with Windows 10 itself.

(The original inspiration was someone who couldn't run Encarta 97 on Windows 10. So, like any good geek solution, it doesn't actually solve the user's original problem at all.)

But I want to stress again: this now works trivially. I'm not some sort of mad genius to have done this thing — I only appear to be the first person to admit to it in public.

1. Your Windows 10 is 64-bit, right? That's the only version that has WSL.

2. Install WSL. Control Panel -> Programs -> Programs and Features -> Turn Windows features on or off — tick "Windows Subsystem for Linux". Restart Windows.

3. Open the Microsoft Store, install Ubuntu. (This is basically what WSL was created to run.) I installed "Ubuntu 18.04 LTS". Open Ubuntu, and you'll see a bash terminal.

4. Install the following from the bash command line:

sudo dpkg --add-architecture i386

sudo apt update; sudo apt upgrade

sudo apt install wine-stable

You can install a more current Wine if you want to faff around considerably. (Don't forget the two new libs that wine-devel >=4.5 needs that aren't in Ubuntu yet!) Let me know if it works.

5. Add to your .bashrc this line:

export DISPLAY=:0.0

You'll probably want to run that in the present bash window as well.

6. Install VcXsrv, which is a nicely packaged version of XOrg compiled for Windows — just grab the latest .exe and run it to install it. Start the X server from the Start button with "XLaunch". It'll take you through defaults — leave most of them as-is. I ticked "Disable access control" just in case. Save your configuration.

6a. If you want to test you have your X server set up properly, install sudo apt install x11-apps and start xeyes for a quick trip back to the '80s-'90s.

7. wine itself doesn't work, because 32-bit binaries don't work in WSL as yet — it gives /usr/bin/wine: 40: exec: /usr/lib/wine/wine: Exec format error on this 64-bit Windows 10. This is apparently fixed in WSL 2.

But in the meantime, let's run Wine notepad!

wine64 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/wine/fakedlls/notepad.exe

TO DO: 32-bit support. This will have to wait for Microsoft to release WSL 2. I wonder if ancient Win16 programs will work then — they should do in Wine, even if they don't in Windows any more.

Thanks to my anonymous commenter below, we have a route to 32-bit:

sudo apt install qemu-user-static

sudo update-binfmts --install i386 /usr/bin/qemu-i386-static --magic '\x7fELF\x01\x01\x01\x03\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x03\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00' --mask '\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xfc\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xf8\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff'

sudo service binfmt-support start

And now we can do:

fun@DESKTOP-7F6DU8P:~$ wine --version

wine-3.0 (Ubuntu 3.0-1ubuntu1)

Encarta 97 doesn't work, though:

fun@DESKTOP-7F6DU8P:/mnt/e$ wine SETUP.EXE

wine: Unhandled page fault on read access to 0xffffffff at address 0x11df:0x00002c11 (thread 0011), starting debugger...

0011:err:seh:start_debugger Couldn't start debugger ("winedbg --auto 15 108") (2)

Read the Wine Developers Guide on how to set up winedbg or another debugger

I'll leave that bit to someone who knows what they're doing. file says SETUP.EXE: MS-DOS executable, NE for MS Windows 3.x — so we need to get down to casually-clicked 16-bit programs working.

Encarta 97 installs and runs flawlessly in Wine 4.13 on Linux ... 4.13 on Windows 10 still fails:

fun@DESKTOP-7F6DU8P:~$ wine /mnt/e/SETUP.EXE

Xlib: extension "MIT-SHM" missing on display ":0.0".

Xlib: extension "MIT-SHM" missing on display ":0.0".

0009:err:process:__wine_kernel_init boot event wait timed out

001d:err:process:__wine_kernel_init boot event wait timed out

wine: Unhandled page fault on read access to 0xffffffff at address 0x11cf:0x00002c11 (thread 001e), starting debugger...001e:err:seh:start_debugger Couldn't start debugger ("winedbg --auto 28 152") (2)

Read the Wine Developers Guide on how to set up winedbg or another debugger

001d:err:ntdll:RtlpWaitForCriticalSection section 0x7e6273e0 "syslevel.c: Win16Mutex" wait timed out in thread 001d, blocked by 001e, retrying (60 sec)

Xlib: extension "MIT-SHM" missing on display ":0.0".

Could not load wine-gecko. HTML rendering will be disabled.

001e:err:seh:raise_exception Unhandled exception code c0000005 flags 0 addr 0x7b4a6abc

wine client error:1e: write: Bad file descriptor

Of course, it gave different error messages across multiple runs ...

oh, this post is popular. While you're here, check out my cryptocurrency/blockchain blog and my book about why Bitcoin and related nonsense sucks. The New York Review of Books and the BBC loved it!

Who owns the working classes?

The question would not seem to be a complicated one. Starting from a philosophical position, the working classes are comprised of individuals who own themselves; they must achieve their liberation through collective action, and only then can they truly become themselves and realize the potential they waste through toiling for others. A material analysis yields an equally simple response: the working classes, by dint of having to sell the only thing they own — their labor — are owned by the bosses, and they must forever struggle to regain control of the products of that labor to own themselves. It is only when the question becomes cultural — that is, when we begin to characterize the working class through an arbitrary system of shared likes and dislikes, tendencies and temperaments, and reflections of the society in which they live — that we muddy the waters beyond clarity.

Unfortunately, it is this analysis, the cultural one, that has held sway in our country at least since the postwar era. Normally, it is an approach peddled by the ownership classes and their toadies: reactionaries, conservatives, certain strains of libertarians, and others who perceive that the capitalist system is either working on their behalf or can be gamed to do so. (See this for a recent and particularly hilarious example.) These people’s interest in the cultural framing has everything to do with division: it has always been used as a tool to sow discord amongst the various groups that comprise the working classes in order to prevent them from coming together and making demands of the owners. It doesn’t really matter what form this division takes — black vs. white, male vs. female, immigrant vs. native, gay vs. straight, rural vs. urban, educated vs. uneducated, service vs. trade, latte sipper vs. coffee drinker, craft beer swiller vs. macro-brew guzzler — as long as it serves as a distraction and keeps everyone’s eyes off the prize.

Recently, however, a strain of this culture-war battle for the imagined soul of the working class has come from the left. I use the identification with much more generosity than it probably deserves, because among these self-proclaimed leftists, there are few people you will meet who are politically active outside of social media. You will generally not find them in activist spaces; they seem to do no organizing; they are not joiners or builders, and they neither lead nor follow. Leftist politics seems to be more or less a hobby to them, or an object of critique alone: they wait for someone else to do something, and then tell them why they’re doing it wrong. They enjoy speculating about whether or not someone actually has any working-class bona fides, an activity I find generally counterproductive, but it can’t be missed that…well, let’s just say they spend a lot more time on the internet than someone who has to work full time is normally able.

They insist that the work of most people who do actual organizing is actually harmful or counter-productive, especially if it ever evinces a shade of social justice; any discussion of racism, sexism, or homophobia, or any attempt to introduce elements of decency towards the disabled, the neuro-atypical, or the traumatized, they say, is nothing more than rank liberalism, and will doom the socialist project by alienating the true working class, who they seem to perceive as a monolithic unit made up of rough beasts who will retreat angrily into their caves if they are ever asked to behave as if they live in a society. Given that their entire critique is based on this extremely inaccurate conception of the working class, it is remarkable how out of touch it really is: sometimes, reading their attacks and listening to their arguments, they seem to have attained their knowledge of the proletariat the same way I attained mine of the Sea Peoples — something out of history books that has a contextual importance, but that is so distant from everyday lived experience that it can never be truly known.

According to this vision of the toiling millions, we cannot discuss racial justice, for they are a mass of unrepentant racists who bristle at the very notion of equality and diversity — as if the working classes in America are not largely nonwhite now, and have not been for decades. We cannot speak of women’s issues or sexual harassment, because the working class consists mainly of grunting Neanderthal males whose relationships with the opposite sex are expressed through clubbings and draggings — as if women have not been a primary component of the low-wage workforce since after the Second World War, and don’t have as much stake in its improvement as men. We cannot ask them to observe social norms that request respect or demand sensitivity, because they are rank morons who can no more be taught to observe social decency than a wasp can be taught not to sting — as if working-class people have not learned to moderate their behavior to the situation their entire lives, in both situations they are forced into (work, school) and ones they choose voluntarily (churches, unions, social clubs). We cannot ask them to understand intersectionality, because they are uniform racially, sexually, and ethnically and their binary brains shut down entirely when asked to process new information — as if working-class people have not been on the front lines of diversity throughout American history and have seen and been forced to deal with social and cultural changes long before they reach upward to the bourgeoisie. We cannot ask them to be flexible or to understand different approaches to workplace organizing, because they are all hard-hat-wearing outer-borough lunkheads — as if working-class people have not been at the vanguard of the shifting economy, and have not seen the trades abandon them and the service industry subsume them for this entire century.

Of course, none of this is to say that the correct Marxist approach to these matters is settled, or that we may not overcorrect or undercorrect, or that this is not a matter of some dispute. But it is a curious vision indeed of the working class for people who profess to be class-forward: veterans aplenty, but with no tolerance or familiarity with post-traumatic stress disorder or other neurological sensitivities depressingly common to those who have served; family men everywhere, but with no experience of autism, gender dysphoria, severe allergies, or learning disorders that are so common that federal laws mandate public institutions have the tools to deal with them; masculinist behavior of the old school, but unable to understand discipline, self-control, or self-sacrifice; rough and tumble lifestyles of debauchery and hedonism, but with nary a soul lost to recovery; unions without racial diversity, families of only the traditional configuration, no one interested in education or elevation, and so committed to individualist indulgence that they’d rather see the whole socialist project fail than give up clapping during meetings or drinking on the job. I’m not sure where they’re finding these proles; I find them in situation comedies and newspaper cartoons of the 1970s, but I certainly do not find them in my organizing among working people. Indeed, one wonders why these revolutionary leftists care to fight for the working class at all, since they seem to perceive it as irredeemably racist, unchangeably sexist, stupid, vulgar, unteachable, violent, and incapable of development. The working class I grew up in, and the working class I know, is accepting, understanding, flexible, kind, bright, resourceful, and with infinite untapped potential; the working class they claim to represent is nothing but a reactionary cartoon.

People of this sort are fond of simplifying their arguments by pointing out that the movement’s foundational document explains in its very first sentence that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”, and that an deviation from their provincial understanding of the cultural character of working people — from which position they give away their game, for it forever takes the place of a material or theoretical understanding of them — are betraying the class struggle that belongs at the forefront of the left. They forget that the second sentence describes the many permutations of that very class struggle and how they have changed over time, and that it goes on, on the first page, to describe the “manifold gradiation of social rank” and the “new classes, new conditions of oppression, and new forms of struggle” that have altered, but not eliminated, prior class antagonisms. We must remember always that, yes, our struggle is a class struggle and always will be. But we must beware always those who misunderstand or misrepresent the nature of class struggle, and who insist on an understanding of class character that is not only dated and incorrect, but which draws its very nature from the imagination of our enemies.

A number of years ago, and during one of those occasional mud-flinging spats that happen in science fiction, a person who I will mercifully not name now tried to dismiss and minimize Mary Robinette Kowal as “no one you should have heard of, and no one of consequence.” This was when Mary Robinette had already become not just a writer of note, but someone widely admired and respected by her peers and colleagues for the work she had done for the community of writers and creators.

The intent behind this person’s words was cruel, and I believe intended to insult and to wound. After no small outcry, this person apologized, and Mary Robinette, who is one of the most gracious people I know, accepted it. But I for one never forgot either the insult to her, or the dismissive intent behind it.

Last night, Mary Robinette Kowal won the Hugo Award for her novel The Calculating Stars. This follows her and her novel also winning the Nebula and Locus Awards. Mary Robinette wrote a tremendous book, and right now she stands at the pinnacle of her field, with all the esteem that it could offer to her, all of which she has absolutely and definitively earned. I could not be prouder of my friend if I tried, not only because she is my friend, but because of her talent, her grace, her strength and her perseverance. I admire her more than I can say.

She has given the best answer to anyone who ever dared to say she was no one you should have heard of: She kept speaking. She kept speaking, and the world listened. And then, having listened, it celebrated what she had to say.

Congratulations, Mary Robinette. Keep speaking.

(A Nowa Fantastyka remix)

Lers of Spoi.

You Have Been Warned.

“The Wandering Earth” is the most successful movie I almost never heard of. It’s China’s second-highest grossing movie ever. Globally it’s the 3rd-highest grossing film so far this year, and the 2nd-highest grossing non-English movie of all time. Yet I blinked and missed its theatrical run here in Toronto; a couple of weeks, a couple of theaters, and it was gone. Pretty shoddy treatment for a movie based on a Cixin Liu story.

Netflix recently slipped it into their lineup with nary a whisper. That’s where I saw it— and after two viewings I can report that “The Wandering Earth” is one of the most derivative movies I’ve ever seen. It’s also unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

I’m still working out how it manages to be both those things at once.

The derivative parts hit you in the face from the opening frame: In terms of sheer epic scale, this movie out-Hollywoods Hollywood. Humanity discovers the sun is about to turn into a red giant and retrofits the entire planet into a vast interstellar spaceship. Ten thousand Everest-sized fusion rockets kick Earth out of orbit and onto course for Alpha Centauri. And all this happens during the opening credits. It’s as if Emmerich and Bruckheimer and Cameron all got into a pissing match to see who could up the stakes fastest.

The characters are also pure Hollywood, stock cut-outs recruited from Central Casting. Plucky young protagonists, check. Obnoxious comic-relief sidekick, check. Wise self-sacrificing father figure, check. No-nonsense soldiers with their eyes on the mission but hearts in the right place, check. All that’s missing is a cute pet dog to run off and force the adults into danger when they try to rescue it.

There’s surprisingly little interpersonal drama. Even other movies which star Nature as Antagonist[1] usually spend some time on the social unrest provoked by imminent catastrophe: the rioting and martial law, the choice of who lives and who dies, the looters and cheaters and altruists who give up their spot so others might live. None of that seems to happen here; those chosen to survive go underground and everyone else apparently just waits outside to die. Nobody rebels, nobody panics (or if they do, it’s not mentioned). Everyone accepts their fate. The conflict we do see is trivial stuff, teenage rebellion or parental scolding designed to get our heroes topside before all the shit goes down.

It’s a heartening, noble view of Human Nature. It’s also exactly the kind of perspective that a totalitarian regime would want to show its citizens. Respect authority. Never question. Do as you’re told, no matter the price. (Time travel stories are illegal in China, did you know that? Can’t have people thinking about alternative realities…) Watching TWE sometimes feels like watching the purest Chinese propaganda— which is strange for a movie in which countries don’t exist any more, in which all of Humanity has coalesced around a World Government to face its existential crisis.

The film does have a refreshingly positive attitude towards science— no trust-your-feelings-trust-the-force, no Scientists Play God and Doom Us All. Science is portrayed here as a good thing, a tool vital to our survival. It’s a nice change from the usual anti-intellectualism permeating the culture these days— but it’s also a damned shame because the science in this movie is absolutely terrible.

If you like to nitpick you’ll love “The Wandering Earth”: why doesn’t Jupiter’s magnetosphere fill Earth’s sky with spectacular auroras, why don’t its radiation belts cook everyone in their suits after an hour on the surface? There’s no need to waste your time on trivia, though; the whole premise of the sun turning into a red giant is five billion years out of sync with reality. If you can swallow that, the subsequent plot hinges on a “gravity spike” knocking Earth off course to send it hurtling toward Jupiter. Nobody explains what this spike actually is, or why it wasn’t foreseen by scientists who were, after all, smart enough to turn a planet into a spaceship. Nobody wonders where Jupiter suddenly got all that extra mass from (and where it disappeared to after the spike had passed). This is especially strange because they talk about pretty much everything else; in one scene an astronaut even has to explain to another why they’re slingshotting around Jupiter in the first place. I haven’t seen such epic levels of astronaut ignorance since David Gyasi had to explain wormholes to Matthew McConaughey in Interstellar.

But a “gravity spike” that defies the laws of physics? Nobody wonders about that except the audience.

By the climax— when our heroes ignite the hydrogen-oxygen mix created by atmospheric intermingling, creating a shockwave which kicks the Earth to safety— I’d lost interest in whether those physics would hold up even in theory. I was too busy wondering how such sloppy handwaving could possibly have come from the same mind who created the Dark Forest trilogy. (To give Liu his due: it didn’t. Turns out none of the movie’s Jovian hijinks happened in his novella.)

What do we have then, when all is said and done? We have a pro-science movie with really bad science. We have jingoistic nationalism without nations. We have a Hollywood blockbuster with no villains. Hell, there are barely any heroes— a couple of people give their lives for the greater good but no plucky team of Avengers is going to be able to fix things when five thousand Earth Engines go offline at once. We are all the heroes in this movie, we have to be: The Human Race, pulling together to save itself, taking the necessary steps and making the necessary sacrifices without complaint.

Which is admittedly a lesson we’d do well to learn here in the west. For all its human rights issues, China can at least plan for the future without pandering to some lowest common denominator every few years. Perhaps such a long-term perspective makes it easier to envision the Earth on a 2,500-year voyage to Alpha Centauri; makes it easier, perhaps, to deal with more imminent (if less spectacular) crises.

Meanwhile, here in North America, we can’t even pass a fucking carbon tax.

Sometimes I almost wish China would just hurry up and finish taking over the world. At the very least that might distract them from making more SF movies.

[1] “Deep Impact” and “Armageddon” come to mind—the latter of which might be closest to TWE in terms of sheer loud dumb spectacle.

Russi Taylor, the voice of Minnie Mouse, passed away last Friday. Over the weekend, my friend Bob Bergen vented on Facebook about some calls he'd already received. Bob is an expert voice actor and one of the best coaches of that art/craft (whichever you think it is). What he was venting about were some calls he'd already received from actresses who asked if they could hire him to coach them to perhaps snag the plum job of replacing Russi as Ms. Mouse.

No auditions have been announced. Russi's funeral has not even occurred as far as I know. But some people are not about to waste any time trying to grab her job. And I just got a call from a voice actress asking if I knew anyone over in the Disney Character Voices Division and could put in a good word for her there. No, I don't and if I did, I wouldn't.

In pieces I've posted here about how to get jobs as a writer, a point I've made repeatedly is that one of the worst things you can do is to appear desperate. Another bad thing — one I don't think I mentioned because I figured everyone kinda knew this instinctively — is to not come across as an asshole. If you're absolutely oozing with talent and no one else comes close, they might (note that I italicized "might") put up with some of that because you're worth it. But the odds are you're not oozing and even if you are, they still might think you'd be too much trouble.

Someone will replace Russi as Minnie because these characters live on and Russi was, after all, one of many over the years who spoke for the lovely M.M. There may even be a "back-up" person already selected — someone who recorded Minnie's lines if/when Russi was unavailable or did something for live appearances that Russi couldn't do. Perhaps one such person will inherit the role. Perhaps they'll do a search, I don't know…but it will be after a suitable interval, not later this week.

I do know that it's really tacky to be hustling for the job of the recently-deceased. It's like looking into the open coffin and saying, "Hey, they won't need that diamond ring where they're going." Some of you may be familiar with the story of how at the memorial service for Lorenzo Music, I was approached by two separate voice actors who felt there was no better time to let me know they felt qualified to step into the role of Garfield.

That story is, sadly, true. Neither of them got the job, by the way. Neither was considered. The guy who got it didn't even inquire.

There's an old saying that I just made up: If you want to be a professional, act like one.

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | June 14th, 2019 | next |

|

June 14th, 2019: As someone who doesn't generally follow sports unless it's a big game let me be the first to say YAY RAPPIES ("Rappies" is what "Raptors" are called) (do NOT correct me on this PLEASE). – Ryan | ||

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | June 19th, 2019 | next |

|

June 19th, 2019: I'm back from Lethbridge! It was a great time AND I GOT TO JUDGE A COSPLAY CONTEST, an activity for which I was not especially qualified but for which I *was* especially enthusiastic. – Ryan | ||

Catherynne M. Valente’s Space Opera gets compared to Douglas Adams a lot. That’s not because it’s an Adams pastiche. Space Opera and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy have different agendas and preoccupations, and are written in different styles to fit. Hitchhiker’s has the polite, straight faced, reassuring voice of a travel guide. Space Opera is extravagantly glittery, with sentences you can get lost in carrying you through unexpected scenic routes. The one similarity is that both have plenty of phrases that make you imagine something vividly or see it in a new way, Space Opera having at least one per page as good as Adams’s “hung in the sky like bricks don’t.” “Watching a kebab slowly revolve in front of a space heater like a sweaty meat planet,” say, or “mumble-crooning artificial grit,” which is as good a description of a currently popular style of folk-rock as I’ve ever seen.

The reason for the Adams comparison is that Space Opera is absurdist space opera. Adams is the best known example of that subgenre, though there’s also Robert Sheckley, and Stanislaw Lem’s The Star Diaries and The Cyberiad.[1] The comedy isn’t the point of the exercise. It’s an excuse to go full Jonathan Swift. These books can have aliens who embody human failings and foibles, and wild ideas that wouldn’t fit logically world-built, internally consistent universes whose realities refuse to be rubbery or loopy. Space Opera has, for instance, a viral strain of space-zombie gentrifiers and a planet of screw-ups that becomes an important trading hub because wormholes are alive and feed off regret.

There’s real political and philosophical scaffolding under the humor. These books use their license to be weird to play with serious ideas and some on the less jokey end approach Borges or Calvino territory.[2] The best ones–Space Opera included–are grounded enough to deal with real emotion.[3] Unlike Duck Dodgers’ 24th-and-a-half century, you can imagine living in these worlds.

Science fiction on the Adams-to-Borges spectrum is an under-appreciated and underserved subgenre. Space Opera is the best addition in years.

The disastrous Sentience Wars are over. Now the galactic community settles its differences with the Metagalactic Grand Prix, a Eurovision-style song contest. It’s time for Earth to enter, or else. See, the Great Octave judges new species’ sentience on whether they can cooperate well enough to pull off a decent musical number. If humans place last on their first attempt the Octave will declare us non-sentient and render us extinct so Earth can evolve someone cooler. Due to the vagaries of alien taste, Earth’s least implausible representatives are the two surviving members of glam one-hit-wonder Decibel Jones and the Absolute Zeroes: Decibel himself, a has-been with the aesthetic of early David Bowie but not the talent; and Oort St. Ultraviolet, an undramatic session musician with two kids, a cat, and a divorce. Unfortunately Mira Wonderful Star, the deceased member of the trio, was the one who kept them working together.

Space Opera is a celebration of music and theatre and glamor. A couple of passages have been repeatedly approvingly quoted online and it’s easy to get the impression they sum up the book’s Message. First, the end of the chapter explaining the galactic community’s justification for the Grand Prix:

Are you kind enough, on your little planet, not to shut that rhythm down? Not to crush underfoot the singers of songs and tellers of tales and wearers of silk? Because it’s monsters who do that…. Do you have enough goodness in your world to let the music play?

Do you have soul?

And Decibel’s philosophy as stated in an argument with Oort:

“Because the opposite of fascism isn’t anarchy, it’s theater. When the world is fucked, you go to the theater, you go to the shine, and when the bad men come, all there is left to do is sing them down.”

And if this were really all this book were saying, it would merely be self-congratulations for smug hipsters. But Space Opera is more complicated and ambiguous than that. Yes, Valente is sincere in celebrating music and theatre and glamor, and why not? They’re genuinely wonderful. But it celebrates music and theatre for the wonderful things they really are, without ascribing to them superpowers they don’t posess. Glamor isn’t everything. And music isn’t the only thing the book celebrates.

The first thing you notice about the Esca, the big blue bird who makes first contact with Earth, is that it looks like the Roadrunner. Y’know, the one the Coyote is after. One of the first things we learn about Decibel is that, as a serious young person, he was frustrated by his grandmother’s insistence that Dess’ “serious and meaningful” science fiction films were not as good as Looney Tunes: “mine is bright and happy and makes a colorful noise, so I put it on top of yours that is droopy and leaky and makes a noise like the dishwasher.”

Which is interesting. Both pop music and Looney Tunes are “bright and happy and [make] a colorful noise” but they’re otherwise opposites. Pop music is cool and glamorous. Looney Tunes are goofy and corny, descended from vaudeville and slapstick. Their mascot is Porky Pig, who is the exact opposite of cool; you feel for him because he tries so hard but he’ll never not be awkward.

Space Opera loves goofy cartoons as fiercely as Eurovision. Decibel wants to be David Bowie, but he’s really the Coyote, chasing things he never catches and not noticing the cliff until he’s already over it. Not that this is a problem; SF is glutted with super-competent heroes and we need more books about awkward, mediocre people (who are, after all, us). Anyway, it might not be a problem if he’d just embrace it:

“That is what Mira and Oort forgot, having been, if not popular, always cool. No matter how mad, bad, and dangerous to know a civilization gets, unto every generation are born the lonely and the uncool, destined to forever stare into the candy-store window of their culture, and loneliness is the mother of ascension. Only the uncool have the requisite alone time to advance their species.”

This kind of bright happiness requires a willingness to risk looking stupid, a vulnerability that’s incompatible with cool but sometimes necessary if you want to be open to new experiences or new people. One of Space Opera’s refrains is “Life is beautiful and life is stupid.” If you can’t be beautiful being the Coyote kind of stupid is nothing to be ashamed of.

Douglas Adams wrote a lot of jokes, but one of his sharpest was the Golgafrincham B Ark.

One day the leaders of the Golgafrincham announced their world was doomed. So they built three big arks. The A Ark would take the leaders and scientists and artists. The C Ark would take the workers, the people who do and make things. And the B ark would take the people in the middle: account executives, security guards, management consultants, telephone sanitizers. And the B Ark would go first, because it was important for morale that the new world be well managed. As the B Ark warped away, the A and C Golgafrincham shared a laugh and congratulated themselves on getting rid of their useless middlemen. Although not for long, as the whole species was shortly wiped out by a disease spread by unsanitized telephones.

It’s an ingenious bit of sleight-of-hand. When you read comedy you assume it and you are on the same side, sharing the jokes. So you laugh at the clever trick the Golgafrincham pulled on their consultants and middle managers and ambiguously useful tradespeople. Aren’t those people annoying? Don’t you wish you could just launch them into space? And Adams is making fun of them; most of the B Ark people are in what David Graeber calls “Bullshit Jobs” and the ones we meet are “useless bloody loonies.” But once you’re lulled into your smug sense of superiority, Adams drops the real punch line. The Golgafrincham are all dead, because bullshit jobs are a real phenomenon but you’re probably not as good as you think you are at identifying them, and there sure as hell aren’t any useless people. Incidentally, the B Ark people are the ancestors of the whole human race, you included.

This is an unexpectedly angry joke, and all along the target was you. What Adams is really doing here is asking you to consider whether you might be an asshole.

Pay attention when Hitchhiker’s fans bring up the B Ark, and it’s amazing how often they miss the point of the joke.

Some background on Eurovision is in order. Every year, every European country submits a new pop song. They’re all performed on live television, and the audience votes for their favorite. It started in the 1950s, around the time international live television broadcasts first became practical. At the time Europe was still recovering from World War Two and Eurovision was meant to bring Europe together and promote international understanding.

There’s one important difference between Eurovision and the Metagalactic Grand Prix. The Metagalactic Grand Prix is how the galaxy distributes “communally held Galactic Resources.” Even if you’ve passed the entrance exam coming in last does a number on your economy, and it’s a very low number. And according to the rules, “If a performer fails to show up on the night, they shall be automatically disqualified, ranked last, and their share of communal Galactic Resources forfeited for the year.”

Which explains why the minute Decibel and Oort step out onto this year’s host planet someone shoots at them.

The fundamental question every war is asking, according to Space Opera, is “Which of us are people and which of us are meat?” Eurovision was created to encourage Europeans to see each other as people. The Metagalactic Grand Prix is a different way to sort out who’s the meat. The participants maneuver and strategize. They try to knock out the competition, usually not fatally. They downvote planets they don’t like to mess with their economies. The dodgy backstage deals certain people offer Decibel and Oort are deliberate tests, to see if the humans will betray each other. But meanwhile the established species are scheming for real.

Music, here, is war by other means. And Earth might be a casualty, because just before he has to go on a Smaragdin gives Decibel a potentially terminal case of laryngitis.

“I never did say we were good; just sentient,” apologizes the Smaragdin.

Which raises the question of what sentience is, exactly.[4] The Great Octave has exterminated a few species. The one we learn about in detail is Flus. You can understand why they offed this one, actually; it’s legitimately self-defense.[5] Flus is a totalitarian hive mind that assimilates other life forms like the Borg.

The same chapter introduces us to the Voorpreet, sentient Galactic Family members in good standing, who are… um, a zombie virus that assimilates other life forms like the Borg. Who everyone bends over backwards to accommodate as best they can while still staying safe, or safe-ish. Space Opera introduces Flus and the Voorpreet together and explicitly asks “how different was a Flus infection from a Voorpret infection?”

The Voorpreet are cool. They’re the creative class, wealthy Silicon Valley gentrifiers: “Yes, yes, they obliterated the natural biodiversity of any region they touched, but wherever their infection took hold, they opened a lot of delightful bistros and shops and start-up tech companies with whimsically casual workplace environments and fusion food trucks and artisanal blacksmithing co-ops and performance-art spaces.”

The lyrics to the one song Flus knows go like this: “It is awesome to be Flus / If you are not Flus, you are not awesome / and will promptly be consumed / also your children and pets.”

The difference between Flus and the Voorpreet is that Flus says the quiet parts loud.

Flus is a group mind–not a species so much as a single threatening individual–so this chapter doesn’t deal with the fundamental problem with the idea of destroying an entire species–humans, say–for their cruelty. You are by definition destroying the victims with their oppressors. The inherent cruelty of some humans is proven by what they do, and the inherent cruelty of the rest is proven by the things the first group did to them. It’s in the tradition of destroying the village in order to save it, or, more recently, freeing Iraqis by bombing the hell out of them.

You get the impression the Octave is looking out for opportunities to just flat out take somebody’s stuff, like the fine old human tradition of liberating nations that coincidentally happen to have something you want. On first contact, the Esca assures Earth that if humans must be exterminated, “all memory of your collective existence will be lovingly collated and archived, your planetary resources tenderly extracted.”

When the Esca entered their first Grand Prix they called their song “Please Don’t Incinerate Us, We’ll Be Good from Now On, We Promise.”

Being declared non-sentient is a lot like being declared a rogue state, or part of an Axis of Evil. It’s not that these places are not at least sometimes genuinely dangerous. But our condemnations are arbitrary: Pinochet was cool, Saddam Hussein was not. We talk about protecting freedom and democracy, but in practice a lot of American foreign policy is just about keeping the oil flowing.

The galactic community is the Nixon/Reagan/Bush/Trump U.S.A., splashed across the heavens and wearing a shallow dusting of glam. Space Opera’s aliens embody our own human failings; they’re us. If any readers actually thought the Metagalactic Grand Prix was a great idea, or that theater was incompatible with fascism, they may have missed the point.

“But galactic society is still… well, society. And society is rubbish,” says the Smaragdin. “Good lord, the Grand Prix is the best thing we’ve ever done, the utter best, and it’s just a bit of song and dance, isn’t it?”

If you read the premise way back in section 2, you might think you have some idea how this story is going to go. The unlikely misfit who overcomes all odds to become a celebrity is one of Hollywood’s standard narratives. Decibel and Oort will settle their differences at the last minute, give a kick-ass performance that also symbolically resolves their emotional arcs, and prove humans can rock, right?

Oh, hell, no. Decibel can’t even pull himself together enough to manage the minimal obligation of writing a song. Also, the laryngitis. The Absolute Zeroes manage not to lose, but the reason is more interesting than just having talent.

What saves Earth is that Decibel has a mutually agreeable one-night-stand with an Esca. (Yes, this is a novel where the Coyote sleeps with the Roadrunner.) And that Oort meets an alien who resembles a hyperactive red panda and forms a real friendship. And on the night of the Grand Prix their actions bring about a pair of miracles that elevate their performance from a disaster to… well, not a disaster, anyway.

What proves Decibel and Oort’s sentience–and in this they’re considerably more sentient than most humans and most of the Extended Galactic Family–is that they don’t divide people into people and meat. They don’t divide people into those like us, the special shiny people and the other ones, who we can do what we want with. Strangers and foreigners are not threats, not prey, not lesser beings they can steal from or forcibly remake into versions of themselves. Decibel and Oort can look at people nothing like themselves and see them as people. They open up to people who are utterly strange to them and risk admitting they’re not starmen at all, just stupid useless bloody loony tunes like everyone else. Acknowledging your own non-specialness and uncoolness–your inner Coyote or your Porky nature–is the first step towards accepting strangers as equals, or even friends. The friends Dess and Oort are able to make help them create a performance they couldn’t manage on their own.

At this point it’s relevant that Decibel was born Danesh Jalo and Oort was once Omar Calișkan and the Absolute Zeroes are the children of immigrants in a long-past-Brexit England. Xenophobia and fascism are constant threats running through the background of Space Opera. After yet another wrong government comes to power, Mira’s Uncle Takumi dies in a racist riot and Dess’s grandmother, the one who tried to show him the beauty in a cartoon rabbit, is deported. This is a near future in which we have not learned much of anything.

On the whole, it’s just as well the best representatives Earth could come up with were two thirds of a one-hit-wonder glam pop trio.

The real test of a civilization isn’t how it treats its musicians. It’s how it treats its Others–more precisely, whether it even has Others. Foreigners, immigrants, asylum seekers. The real test of sentience isn’t whether you’re shutting someone’s rhythm down, it’s whether you’re keeping children in cages.

It’s tough to say what the long-term critical perspective will be on a book that’s only been out a year, but my guess is that Space Opera will become a classic. It has something in common with most great comedy: underneath the jokes, it’s angry.

On the fantasy end, Terry Pratchett and Ursula Vernon/T. Kingfisher are close cousins. ↩

i.e. some of Lem’s work, or Ursula K. Le Guin’s Changing Planes. ↩

Not something Adams is especially associated with, but I find much of his work–Marvin’s death in So Long and Thanks for All the Fish is one example–genuinely affecting. ↩

What happens if the Octave finds a species that doesn’t even have a sense of hearing? Will they be allowed to be sentient? ↩

This is a smart move; a straightforward mass murder would have made a mess of the novel’s tone. ↩

A reporter who called asked me, "If you had to summarize in one sentence why MAD is going all-reprint, what would it be?" I said, "It's been losing money lately and the folks in charge of it didn't have a good idea how to stop that." That's kind of why most things in business end.

But of course, MAD is not going to disappear. It's too valuable a name to allow to disappear. It's a corporate asset. In a world where "branding" matters like just about nothing else, it's a brand that's very well-known and which has mostly-positive feelings surrounding it. If tomorrow, you and I were starting a new humor magazine, we'd kill to have a name for it with the notoriety and good reputation that MAD still has.

The problem is that the Powers That Are don't know how to get people who love MAD to actually purchase MAD. That's a very different problem from if you, let's say, were saddled with a failing business that nobody ever liked and would never miss. There's very little point in trying to save that business.

I'm going to guess that whoever made the decision about MAD didn't anticipate how big a news story it would be…and that a decision that to them was "Let's slash the budget for a while until we figure out what to do with it" has been viewed as "Let's kill a beloved national institution forever." That only serves to devalue that precious brand name. As I said in this piece, "It ain't good for them to tell the world that the name of MAD is of such low value that it can't even sell MAD."

I will further guess that within the vast Time-Warner empire, there are people at this very minute trying to formulate a plan whereby they can be the hero that rescues that beloved national (and merchandisable) institution.

And I'll bet there's some outside company — probably many outside companies — inquiring as to whether Time-Warner would sell or license MAD and Alfred to an outside publisher. The corporation probably won't make any such deal but in the past, outside interest has often caused someone to say to someone else, "Hey, if they think they can make money off this, we should be able to figure out a way to make money off this."

I'm not saying they'll find it and I'm certainly not saying I know what it is. I'm certainly-certainly not saying it — whatever "it" turns out to be — won't be worse for the collective experience known as MAD. It may slip into the hands of someone who doesn't "get" what was magic about MAD for 67 years and, in search of a similar business model where there isn't one, will say, "Gee, Game of Thrones is real successful now. Is there a way to make MAD more like Game of Thrones?"

But they're already talking about an annual issue of new material — a plan unmentioned in the letter they sent out last week to longtime contributors telling them the mag was going all-reprint. That's a start and I don't think we've seen the finish. Far from it.

That's a photo of Joe Raiola, a writer of very funny things who was a member of the editorial staff of MAD for 33 years. This morning, he posted the following to Facebook. I'll be back after it to add on my thoughts but I only disagree with two things Joe says…

During its long run, MAD Magazine inspired many second-rate imitators. There was Cracked and Sick and Crazy and so on. Oddly enough, the latest MAD imitator is MAD itself. The MAD published out of Burbank since the spring of 2018, which is being shut down, is an imitation of the real thing.

I say this not as a shot at the new MAD staff, which was thrust into an impossible situation. Not a single member of the editorial staff had any previous MAD experience, except as readers.

From 1952 to 2017, MAD had a remarkable continuity of talent. DC, which took over after Bill Gaines died in 1992, is a comic book company specializing in flying caped aliens. The former MAD staff offered sufficient resistance to remain editorially independent. And, to its credit, DC came to respect the MAD staff, even if the suits didn't fully understand the mechanics of creating a humor magazine.

When DC moved to California in 2014 and the MAD staff refused to go, DC wisely decided to leave MAD in New York. In November of 2017, Rolling Stone wrote: "Operating under the cover of barf jokes, MAD has become America's best political satire magazine."

Bottom line: For MAD to have had a chance to survive, it needed to remain in New York and the editorial reins been passed on to the "junior" staff, which had been in place for nearly two decades. That did not happen and this is the predictable result.

On a more positive note, I just found out that in 15 minutes I can save 15% on my car insurance.

Some might dismiss Joe's words as grapes of the sour kind but I don't think he's wrong except that I liked the new MAD, at least in its first issue or two, more than I think he did. Secondly, I think it's conceivable MAD could have benefited from the right "new blood" inserted into (but not displacing) the old structure and that didn't have to happen wholly in New York. I think what went awry here is much the same thing I see as a problem with just about everything that comes out of DC Comics these days…

If you talk to anyone who works there these days — anyone! — they will tell you this: That you come to work each day wondering who's going to get fired. Eventually, inevitably, it will be you…but until that time, you won't be sure who'll be above you next week. I would imagine the decision to suddenly and unexpectedly amputate most of the MAD division has only contributed to that environment. The answer to the question "Who's in charge?" is "I dunno. What time is it?"

Now, to be fair, MAD Magazine has long faced a problem that even the former staff could not make go completely away: It's a magazine. Magazines don't do that well these days and every danged one of them that's been around for a while is selling a fraction of what it once sold. On a percentage basis, Playboy hasn't fared much better than MAD and it's not because Americans are getting sick of looking at beautiful nude women. People just don't read magazines of any kind the way they used to.

The easy assumption is that this is the result of that new-fangled "internet" thing but it's actually a trend that began before any of us had handles or e-mail addresses. The eruption of online communication and entertainment merely turned a trickle into a waterfall.

I'm going to pause my add-on to Joe's essay here and insert one by my pal Paul Levitz, who ran DC Comics (and therefore presided in a business sense over MAD) for many years. Paul also posted what follows this morning on Facebook. Take special note of the one passage I have highlighted…

Culturally speaking, MAD Magazine is probably the most powerful print entity to emerge from the comics industry. At its peak (ironically, the Poseidon Adventure parody issue…only MAD could crest with a story about sinking)…MAD had a circulation over 2 million copies an issue, a pass-along readership that was a multiple of that, and was the magazine sold at the largest number of outlets in the U.S. and Canada. Its impact on the broader popular culture, spreading a snarky, borscht-belt, NY Jewish sense of humor and cynical attitude towards advertising, government, big business and human behavior, is immeasurable.

Founders Harvey Kurtzman and Bill Gaines, and editors Al Feldstein, Nick Meglin and John Ficarra who built on the foundation and made it a towering institution shaped the Baby Boom generation, inspiring movements from underground comix to Vietnam War protests. And the Usual Gang of Idiots — the incredible, long serving writers and cartoonists who filled the magazine — brought styles that even the most art-blind kid could recognize, they were each so distinctive and personal.

I've been proud to be a friend to some of the gang since my adolescence, and to have served as MAD's publisher for 17 years. I can't say I contributed much to its glory: I never found the business model to help it adapt to the changes in our culture, to kids' reading patterns, and technology that has accelerated the cycle of snark. But we tried, again and again.

MAD the magazine may be gone, but its legacy lives on in our conversations and our attitudes. I wrote about how the different editors' world views shaped the magazine (and our mindsets) in Studies in American Humor, Vol. 3, No. 30, a few years ago — using the vehicle of an interview with Al Jaffee, the then only "Idiot" to have worked with all of the MAD editors. There's an academic press book version of that issue coming out eventually, and much will be written about the fading of this American institution.

But today, I'm just sad.

Paul, one of the humblest guys I know, is shouldering way too much of the blame in the highlighted passage. Everyone at or around MAD for decades struggled to find that business model that would allow a magazine to thrive in a declining market for magazines.

A lot of what they did helped for a time. Purists shrieked when MAD began accepting advertising again — yes, again. Those who moaned that it was a betrayal for MAD to contain ads for "the first time" were unaware that it once had. But that move in 2001 kept the publication in the black as did upgrades in the area of interior color and print quality and various reprint projects.

What really kept MAD alive in perilous times though were (a) its tradition and (b) its content. As I've written here several times, I thought its content was really, really strong the last decade or two. There was some brilliant comedy writing in its pages.

If MAD had been the product of a small publisher working out of a low-rent office somewhere, that might have been enough. The hefty overhead of being a Time-Warner project — and their overall business model of seeking to monetize every property in every medium — caused MAD to fall short. I do not think it's gone forever. I'd bet my complete collection of that publication that the brand is too valuable to not be relaunched before long.

I just think they don't know what to do with it now…and that I blame a lot on that "Who's running the store?" problem I mentioned earlier. Since MAD was wrested from its New York crew, the answer to that question has been "Everybody" and when everyone's running the store, no one's running the store. My pal Bill Morrison was editor for a time and if you absolutely had to have someone with no MAD experience running MAD, you couldn't ask for a better pick. The problems there were that to the extent Bill was able to run it, it was in an unstable environment…and that it was still, when you got right down to it, a magazine.

I do not have a solution to that not-tiny problem. My gut tells me there is one but what the hell does my gut know about marketing? I just don't think giving up and abandoning MAD's long-established spot on newsstands and killing the "tradition" is a solution. Once those outlets stop making room for MAD on their racks, it'll be ten times as difficult to get them to clear a spot for it ever again.

Creatively, what MAD needs is a stability that I don't know is possible in the current corporate structure there. I know that the new MAD may have claimed to be the output of "The Usual Gang of Idiots" but it wasn't. The "idiots," such as they are, were not in any sense "usual."

When I fell in love with that publication in 1962, every issue was the work of more-or-less the same people: Mort Drucker, Don Martin, Antonio Prohias, Dave Berg, Frank Jacobs, Larry Siegel, Stan Hart, Al Jaffee, etc. They didn't even have Sergio Aragonés when I started buying the thing but he came along shortly after and quickly became a star there, a highlight among many in every issue. The last true star I think MAD added to its roster was Tom Richmond and that was around the turn of the century.

In the new MAD, you have a few holdovers from the previous regime like Sergio, Jaffee, Richmond, Dick DeBartolo and one or two others. But most of the magazine has been filled with transients…folks who look like they're auditioning even though no ongoing positions seemed to be available. The folks running MAD lately haven't found the new Don Martin, the new Jack Davis, another caricaturist besides Richmond worthy of occupying the space Drucker once did, etc. I don't believe it's because such people don't exist. I just think that's the way Time-Warner operates these days.

No one person among the mob of those who work on them can say what's right for Superman or Bugs Bunny or Batman or Tweety or any of the wonderful properties they've accumulated over the years. None of those folks created the properties. None of them has the overriding say as to what's right or wrong for them. And not one of them can reasonably expect to be associated with that property for long. All those legendary characters are being raised by baby-sitters, not by actual parents. Not even foster parents.

The demise of MAD is a failure of marketing and distribution and promotion; of no one finding that elusive business model that Paul mentioned. But even a sound business model needs a sound product to sell and I'm not sure it's possible to create that in a workplace where even the highest-ranked exec is really a well-paid (for now) office temp. Joe Raiola was right. The less MAD was controlled by corporate overlords, the better it was.

Sometimes, the Tories offer us a glimpse into their psychology. So it was yesterday when Sarah Vine tweeted:

Watching the #RestaurantMakesMistakes and astonished to learn that people with dementia struggle to get benefits. Is this true? And if so, how is this not a national scandal?

What she’s expressing here is the cognitive dissonance that her own party’s policies actually have nasty effects upon real people. Her consternation arises from the fact that, for many Tories, this is not supposed to happen. Many of them, I suspect, are not actually evil but rather guilty of a recklessness that comes from a particular conception of politics – a conception which sees it as a game of positioning, and of pandering to the imagined world of the Daily Mail. Politics is a post-modern activity in which words and appearances are everything and consequences and reality are nothing.

So for example:

- Benefit sanctions are supposed to crack down on cheats and malingerers, not real, deserving people. It is only when these appear on TV that the illusion – and it has been just that for years – is broken.

- The “hostile environment” policy was meant to remove illegal immigrants rather than members of the Windrush generation who are, remember, 100% British.

- Austerity was intended to establish prudent control of the nation’s finances. The fact that it has killed thousands is at best, a mere statistic, and at worst just another controversial claim.

- Brexit is about prioritizing a conception of national sovereignty over GDP. And GDP is a mere statistic, not the jobs and livelihoods of real people. What was so transgressive about Jeremy Hunt’s promise this week to shut down Titan Steel Wheels was that he broke this illusion, and linked what is supposed to be a mere abstraction to the lives of real people.

All of this is possible because for Tories – at least professional ones in the media-political Bubble - politics is a reified activity separate from ground truth. Robert Protherough and John Pick have described how modern management “deals largely in symbols and abstractions...[with] little direct contact with the organization's workers, with the production of its goods or services, or with its customers.” For Tories, politics is like that. It’s a cosy game in which nobody is supposed to get seriously hurt: the losers only leave to get well-paid sinecures from fund management companies.

Of course, if we had a functioning media, reality would intrude. But we don’t, so it often doesn’t. The truth is difficult and complicated and in John Humphrys’ revealing words “a wee bit technical and I’m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don’t clearly understand.” Bubble journalists are much happier covering the Tory leadership race than they are at analysing the real-world effects of actual Tory policies - a preference which generates sympathy for charlatans rather than experts. As Tom Mills says, the BBC “will aim to fairly and accurately reflect the balance of opinion amongst elites.” That can efface ground truth.

The upshot is that our media-political establishment conforms to what Kenneth Boulding said (pdf) back in 1966:

All organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization, the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

The problem which Ms Vine discovered this week, though, is that reality has a nasty tendency to intrude occasionally into the imaginary world.

If you follow the news it’s hard not to spend time thinking about the end of civilization as we know it. An Australian think tank recently speculated that climate change might end it by 2050. I recently felt like reading Shirley Jackson and immediately thought of The Sundial.

The Hallorans are the wealthy patrons of a nearby village. They’ve just buried the heir. His mother, Mrs. Halloran, may or may not have pushed him downstairs. Mrs. Halloran is getting ready to rid the Halloran mansion of the family and their increasing collection of houseguests and hangers-on–everyone but Fancy, her only grandchild, who she’ll raise to be another Mr. Burns-esque tyrant like herself–when her sister-in-law Aunt Fanny receives a vision from Fanny’s dead father, the Halloran patriarch: in a few weeks the world will end. Only the people in the big house will be saved.

People who’ve never read Shirley Jackson remember her as the author of that haunted house book and that story about the woman who’s stoned to death. They forget she’s funny. Shirley Jackson is one of the greatest comic writers of the twentieth century and The Sundial might be her funniest novel.

There’s a concept called “passage of disbelief.” I thought it was a common genre-criticism term, but I Googled it and the only reference I could find was on the website of a writer I’m not familiar with, so now I don’t know where I heard it. Anyway, the passage of disbelief is the part of a weird story where the characters go from disbelieving the weirdness (Aunt Fanny has lost her mind) to accepting it and dealing with the consequences (Okay, so the world is ending, what now?). As Aunt Fanny is prophesying, the uncanny appearance of a snake in the library gives the family a physical manifestation of weirdness to hang their faith on. And Mrs. Halloran is too proud not to go along: if the end is coming, she’s going to manage it. So The Sundial’s passage of disbelief is mercifully short.

This lets the book get on with things–it’s paced like a screwball comedy. And it lets Jackson milk plenty of humor from incongruity. The Hallorans receive a grand prophecy of doom and react as though the apocalypse is an momentous and inconvenient but basically normal event to plan around. The tone of their dialogue clashes with its subject. Like Arthur Dent, seeing Earth destroyed and asking if there’s any tea on this spaceship.

“Evil, and jealousy, and fear, are all going to be removed from us. I told you clearly this morning. Humanity, as an experiment, has failed.”

“Well, I’m sure I did the best I could,” Maryjane said.

The Sundial’s other comic strength is voice. Sometimes writers trying to be funny give every character interchangeable Whedonesque banter. That’s the wrong way to do it: great comedy is about individual voices and incompatible world views running into each other. Mrs. Halloran talks to everyone like she’s talking to a disappointing servant. Essex, the sycophantic young man hired to catalog the library, never misses a chance to show off his education. Miss Ogilvie, Fancy’s governess, is uncertain and timid, panicking at odd moments. Aunt Fanny switches between surface-polite cattiness to Mrs. Halloran and oracular profundities.

Any two characters are most likely talking past each other. Get everyone into the same room and you’ll be reading three overlapping conversations at the same time, not so much playing off each other as bouncing.

But The Sundial also has an air of menace. Shirley Jackson works in the liminal space between real and unreal and it keeps you constantly off-balance. It’s often unclear what’s possible in her stories, what’s metaphor and what’s literal. Even when they’re funny, they feel eerie. Didn’t we see some of these moments in earlier flashes of prophecy? As the climax approaches, isn’t the weather growing ominous? In Jackson’s world, prophecies of doom might come true.

What is this world? what asketh men to have?

Now with his love, now in his colde grave

Allone, with-outen any companye.

The Hallorans’ sundial is inscribed “What is this world?” It’s a line from Chaucer’s “The Knight’s Tale,” and a good question. We use the word “world” in a couple of ways. There’s the literal world (the one that’s ending, everyone’s pretty sure) and then there’s my world, or your world, or Wayne’s or Christina’s world.

Mr. Halloran created a world of his own, self contained–when Julia, one of the guests, decides to leave she wanders through a fog only to end up back at the front gate, as though the outside world has already gone. Inside the Halloran house is a dollhouse Fancy rules with a grasp as tight as her grandmother’s. More ambitiously, Fanny has recreated the four-room apartment where her parents lived when she was a child, before her father struck it rich and built the walled estate near the village. Worlds nest in each other, each shutting out another layer of unwanted reality.

A Babbity businessman who had to be talked out of plastering his mansion with slogans like “You can’t take it with you,” Mr. Halloran wanted to be lord of the manor, philanthropic patron to the villeins. Fanny just wants her parents back. Recreating their apartment is as close as she can get. The Hallorans create worlds where they can imagine living the ideal versions of their lives, and shut out whatever reminds them of the suboptimal versions. Carving out your own smaller, more manageable world can be an act of self-definition. When you’re in charge of your world you’re in charge of your life.

There are a lot of apocalypses in science fiction. Like, a lot. Everybody wants to blow up the world. Standing in the bookstore skimming the blurb of this year’s dozenth zombie nightmare, you may ask: what are all these apocalypses doing here? Good things, often. Some post-apocalyptic stories explore character in extremis. Some speculate on plausible if-this-goes-on disaster scenarios and ways to survive them. Some stories are about rebuilding society and finding new (hopefully more humane) ways to order it.

But some stories just sweep the world away to give their heroes a cleaner stage to act out their fantasies. A complex, uncontrollable, frustrating world is pared down and in the new, smaller, more manageable world the survivors’ true selves are free to blossom. Which may not be that different from their old selves: the stereotypical “cozy catastrophe” follows nice middle class people muddling through the collapse of civilization with middle class niceness. But sometimes the end of the world allows some previously ignored or undervalued person to express their true heroism. Unfortunately this is often a survivalist asshole who was previously ignored because he was an asshole.

Basically, these stories are fantastical echoes of J. M. Barrie’s The Admirable Crichton. So are many of their close cousins, portal fantasies and unexpectedly-tossed-into-space SF. The fantasy is that we’re not really the ordinary mediocre people we appear to be. Given the right environment–a desert island, a fantasy kingdom, a post-atomic wasteland–the flaws and virtues conventional society keeps repressed would manifest in everyone, and our own true, presumably better, selves would break free. That’s not necessarily an unhealthy fantasy! People’s environments do affect them. It can be fun to imagine finding one that fits you perfectly.

As long as you’re not a survivalist asshole. The failure mode for new-world stories is the hero who confuses being their best self with being better than everyone else, or being in charge. If your true excellence is only visible after some sizable chunk of the competition has vanished, how excellent can you truly be? Maybe there are limits to how radically a sudden change in environment can transform your character. Sometimes a confused man in a bathrobe, plopped down on a spaceship, is still a confused man in a bathrobe.

One of the Hallorans’ guests does some scrying with a mirror. Her first session isn’t reassuring, but the second time she sees people dancing in a garden, carefree. She’s seeing what everyone expects her to. Fancy isn’t impressed; she thinks the apocalypse won’t change anything, and after the Hallorans have their new world they’ll just start pining for the old one. After all, the Hallorans already have an oversized garden, and if they wanted they could dance in it: the villagers do when Mrs. Halloran throws them a goodbye barbecue. If the Hallorans aren’t dancing in this world, why would they in the next?

The Hallorans don’t mix with the villagers. They’ll throw a festival, sure. They’ll fund the villagers’ schools and libraries and send the brighter ones to college; the lord has obligations to the villeins. But they don’t mix with them. That’s the root of Fanny’s split with Mrs. Halloran, who “came in through the servants’ entrance” to marry the heir.

In Mrs. Halloran’s dreams she lives alone in a cottage. That would be enough as long as no one intrudes to threaten her, like the obnoxious Hansel and Gretel who invade her nightmares. To stay in control of her own life Mrs. Halloran made herself into one of those people who control everyone else. She has it down perfectly; she condescends even to her oldest friends. By the end of the book she’s typing up rules for the new world. (“Mates will be assigned by Mrs. Halloran. Indiscriminate coupling will be subject to severe punishment.”) You’d think the Hallorans were the products of a feudal system going back as far as the land itself, that Mrs. Halloran hadn’t come in through the wrong door, and that Aunt Fanny hadn’t grown up in a four-room apartment. Mr. Halloran’s world insulates the Hallorans from any hint they might not be a superior class of people.

Although for superior people, the destined masters of the new world, the Hallorans seem singularly unprepared to survive. The supplies stockpiled in the library include such necessities as a gross of corncob pipes and a carton of tennis balls. They burned the books to make room; Fanny thinks they’ll be able to get by with a boy scout manual. She also picks up a random guy to help repopulate the earth:

“Captain Scarabombardon,” said Aunt Fanny unexpectedly.

“At your service,” said the stranger, who was clearly extremely bewildered.

See, Fanny has to name him because he needs a proper identity. The Hallorans can’t save just anybody. They’re also still keeping Essex (they probably don’t need him to catalogue the boy scout manual, but we never saw him working in any case) and Miss Ogilvie, but they’re sending the ordinary servants home the night before the event. Nobody thinks they’ll be needed.

Douglas Rushkoff was once invited to talk to a half-dozen hedge fund executives about the future of technology. He was caught off guard by what kind of technology they were interested in:

Finally, the CEO of a brokerage house explained that he had nearly completed building his own underground bunker system and asked, “How do I maintain authority over my security force after the event?”… The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival. Or maybe building robots to serve as guards and workers — if that technology could be developed in time.

For certain wealthy and powerful people, especially the libertarian, tech-savvy types, preparing for the future doesn’t mean making the future better or working to keep the worst possible futures from coming to pass. It means letting the disaster happen, surviving, and making sure they’re still the ones in charge.

Mr. Halloran was the beneficent lord only as long as his villagers played their roles, performing gratitude and staying in their places. If they dropped dead while building his house, he’d be angry about having to move the body. If he needed some farmer’s land for his grounds, he’d wall it off, and good luck finding a lawyer who didn’t work for him. He’d send the farmer’s son to college afterward. It wasn’t generosity. He needed to be the one who did the rescuing, the excellent one, the one who made the rules.

If you’re ever feeling bored you might decide to sort apocalyptic stories into two groups. Or maybe you wouldn’t, I don’t know. Either way, one possible division is challenging and comforting stories. Comforting apocalypses are not all bad. Vonda N. McIntyre’s post-apocalypse Dreamsnake is comforting because it shows people trying to build a saner, kinder world. But other kinds of comforting apocalypse–cozy catastrophes, triumphalist survivalist stories–are about domesticating existential threats. They reassure the audience that the world can end without their personal worlds having to fundamentally change. Which is still not terrible if your personal world is modest. The problem comes when you need to be superior.

Mrs. Halloran can’t afford to ignore Fanny’s prophecy because she can’t imagine a world without Mrs. Halloran at the top.

“It is my house now, and it will be my house then. I will not relinquish one stone of it in this world or any other. Everyone must be made to remember that, and to remember that I will not relinquish, either, one fraction of my authority.”

If it were merely the end of the world, Mrs. Halloran could call Fanny crazy and put it out of her mind. But she can’t risk the possibility that the world might stop being about Mrs. Halloran.

Which it will, inevitably. She’s the center of her own world, because that’s everyone’s world looks from inside. But everybody dies, and eventually Mrs. Halloran’s world will just… stop existing. It’s the inevitable existential threat and it’s impossible to imagine. What is it like not to exist? It’s not like anything. But Mrs. Halloran also can’t imagine a world where she exists, and isn’t in charge.

Douglas Rushkoff ended his visit with the hedge fund executives by giving them some advice:

I suggested that their best bet would be to treat those people really well, right now. They should be engaging with their security staffs as if they were members of their own family. And the more they can expand this ethos of inclusivity to the rest of their business practices, supply chain management, sustainability efforts, and wealth distribution, the less chance there will be of an “event” in the first place.

They weren’t buying it. Which is odd, because in reality most people respond to disasters by coming together to help each other–pooling resources, rescuing neighbors, working together to clean up. That is, in fact, the surest way to survive. By contrast, an underground Bond-villain bunker patrolled by shock-collared security guards is absolutely the most harebrained fantasy in the world. But for Rushkoff’s hedge fund managers, it’s at least imaginable. The end of the world is one thing, but Rushkoff’s inclusive and less unequal world would be the end of their world.

Hallorans and hedge fund managers have something in common with the people who like survivalist aspirational apocalypses: they have more fun imagining the apocalypse than imagining how to prevent it, or recover from it. It’s easier to give up the world we all have to live in than to give up their own superiority.

The wealthiest people in the 21st century–the Jeff Bezoses and Mark Zuckerbergs–have a lot of money. Like, a lot. So much money it’s hard to conceptualize exactly how much money they have. They have social capital, too; everybody listens to them, even when they’re Elon Musk. A few billionaires, if they were willing[1], could fully fund a moon-landing level plan to mitigate the effects of climate change. Unfortunately there’s a small but non-zero chance this would result in a world where, instead of basically owning everything, they were merely very rich. So instead of doing necessary maintenance on the world our billionaires spend their resources on stuff that won’t rock the boat. Or, at most, come up with goofball comic book survival schemes like seasteading, private mars colonies, and underground bunkers in New Zealand.

Good books have many possible interpretations. As time passes they take on new, unintended interpretations in new cultural contexts, sort of like the way those Admirable Crichton-story characters show new sides to their personalities in different worlds. From a 21st century perspective, The Sundial looks like a takedown of billionaire disaster-prep fantasies. If we do come to the end of our civilization–from climate change, pandemics, rising fascism, whatever–it will be at least in part because our real-life Hallorans were more frightened by the end of their world than the end of ours.

Even if they were unwilling, if we just made them, y’know, pay enough taxes to pull their weight. ↩

“A government holds office by virtue of its ability to command the confidence of the House of Commons, chosen by the electorate in a general election.”

2.20 Where a range of different administrations could be formed, discussions may take place between political parties on who should form the next government. In these circumstances the processes and considerations described in paragraphs 2.12–2.17 would apply.

2.09 “In modern times the convention has been that the Sovereign should not be drawn into party politics, and if there is doubt it is the responsibility of those involved in the political process, and in particular the parties represented in Parliament, to seek to determine and communicate clearly to the Sovereign who is best placed to be able to command the confidence of the House of Commons.”

And that’s the big big problem because you and I both know that this government is going to say “there isn’t any doubt”.