Aunt Tillie and Aunt Millie never could hide their ambivalence from the guests.

Aunt Tillie and Aunt Millie never could hide their ambivalence from the guests.

Elenathis woman is phenomenal

Jocelyne is everything I hope to be as a woman. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone so sure of themselves. Her presence is as bold as it is soft and gentle. She lights up a room without taking center stage and isn’t trying to be anything but herself, which is what I consider to be truly cool. It’s not about the fact that she is incredibly well dressed (because she is) or has those natural luscious curls we all dream about (because she does), Jocelyn just does, is, and becomes whoever and whatever she wants to be. And as a young woman, I admire that. So with a smile of admiration on my face I’d like to introduce you all to Jocelyne Beaudoin!

ElenaI am close to liking this..

I started my Whiskey Bar with some old warehouse flooring. I lightly sanded and treated it with some gold leaf and finished with yacht varnish. Next, I incorporated upcycled trumpet pieces and a vintage steam gauge. I put it all together with a 1950’s spirit optic.

Read Upcycled Steampunk Portable Whiskey Bar by Gerry Mckenna on Recyclart!

ElenaSpeechless!

At the first instance, you might think that they are simple paintings on walls or fences. However, if you take a close look, you will soon be able to discover the cross-stitched patterns, which are entirely free from smelly spray paint. Folded paper origami, crochet, and lace-making have already been successfully displayed on the streets. Now it’s the time to adorn the streets with cross-stitch, and some artists have already started moving ahead on this path.

Raquel Rodrigo is a Spanish artist who is adding charm to the streets of Spain by turning them colorful with her unusual floral cross-stitch patterns. This talented artist, born in Valencia, creates her masterpieces by wrapping wire mesh with thick rolls of string. These are designed in advance which are then unrolled at the designated location for bringing in a unique combination of creativity and color in the surrounding space.

Usually, cross-stitch patterns are present on stuff within the house; hence this public installation of cross-stitch quickly catches the eye, being a great contrast against the urban backgrounds where they are installed.

Raquel is one of those women, who, in the last few years, have increasingly made their appearance in the street art scene. She is weaving colors across the city, taking inspiration from one of the oldest embroidery forms.

These are in fact giant embroidery work over fences. Urban X Stitch, a French street art duo based in Lyon, adorns ordinary chain-link fences by designing colorful and bright characters in cross-stitch patterns. They begin with cross-stitched patterns drawn to scale and then the same is transferred to fences with the help of fabric pieces. These artworks, including different patterns from logos to cute animals, look quite captivating and beautiful.

Read The Best of Cross-stitched Street Art by Neokentin on Recyclart!

ElenaAn American in Paris...

ElenaMore wine drama!

ElenaI really enjoyed the Square. Much more than his Force Majeure (Snow Therapy), which I think film snobs preferred

A satire on the contemporary art world sits edgily alongside a skewering of male privilege and middle-class altruism in Ruben Östlund’s surreal Palme d’Or winner

The publicity for Swedish writer-director Ruben Östlund’s Palme d’Or winner The Square features Terry Notary as performance artist Oleg, stripped to the waist, mounting a table at an upmarket dinner and glowering with animalistic rage. It’s an arresting tableau – baffling and intriguing, promising anarchic action and titilatory spectacle. The fact that this in-your-face image only partly represents the film itself seems entirely appropriate, since one of the key themes of Östlund’s surreally cerebral and increasingly weird art-world satire is “the difference between art and marketing”.

“The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring,” reads the rubric for the art installation of the title: a floor-level, illuminated outline of a space in which altruistic behaviour is compulsory. “Within its bounds we all share equal rights and obligations.” Such aspirations are noble but hardly headline-grabbing – until two youthful PR creatives conjure up a shockingly offensive promo video (think Wag the Dog meets Michael Bay) that promptly goes viral. Meanwhile, suave museum director Christian (Claes Bang) is too distracted by the whereabouts of his stolen wallet and mobile phone (ringtones constantly interrupt the drama) to pay proper attention to his job, or the people with whom he works.

Continue reading...Elena:(((((((((((((

ElenaSHAPE OF WATER FOR THE WIN

The man who adds a dash of dark whimsy to his every project returns with a Cold War-era fantasy saga about the romantic pairing of a mute cleaning lady and a humanoid fish creature. The Shape of Water is Guillermo del Toro’s remarkable tenth feature, and it has been a long and winding road since his extraordinary debut, Cronos, in 1993. We speak to the iconic director about his fondness for monsters, old movies and underdog outsiders.

LWLies: How do you define a monster?

Del Toro: Rather than defining a monster, let me define the monster movie. A monster movie is a movie where the monster is not hidden or hinted at, but displayed. It’s right there in front of you. Not only as a creature that is a part of a story, but as the story itself. And also, this monster symbolises the creative act of making the movie. There’s part of the final product that is like, ‘Look, we made this gill man, or this Frankenstein, or this killer alien’. And in turn, this affects the design of the movie as a whole. The design work in The Shape of Water is a bullseye. You have the outer core – cinematography, production design, wardrobe, colour palette and all of that. And right at the centre, is the monster. Everything else serves the monster. That’s a monster movie.

What other types of monsters are there?

The real monsters are people who are perverse about their function in life. Like a politician who is supposed to serve the people, and serves anyone but the people. A priest who is supposed to preach peace and solace and wisdom, and is an agent of corruption, brutal morality and destructive guilt. These are monsters for me. An army that doesn’t protect a nation but defends the interests of the rich. A monster is also an extraordinary creature who exists above nature, or below nature. Those are the monsters for whom I have empathy. Unlike a politician, these characters suggest the possibility that there are more things in heaven and earth than your imagination can conjure. Yet the moment they step in, what you see is what they are. Giant gorilla. Giant lizard. That’s what they are.

Do you find there’s a difference when you’re writing male and female characters?

I write it like a human. It’s a human character who is known to me through 53 years of existence. I try to put myself in a place that is not my own. It’s empathy. Always. I write for the bad guy, Strickland, with great empathy. I think he is less smart than he thinks he is. I wish he was smarter. He is in above his head. All he understands is brutality. But I write from my own experience. There’s a sequence where he has a conversation with an army general. I’ve had that conversation with studio executives. With Sally, I see everything she has done. I look and listen, and I try to calibrate the text for her. It’s like writing a song for a singer. If you think of ‘Over the Rainbow’, it’s as if it was written for Judy Garland. But if it’s written for Tom Waits, it’s different.

The recreation of 1962 – what were your primary research sources?

I looked everywhere. Mainly from the late ’50s to the ’60s up to the death of Kennedy. It was crucial that the story happened prior to that date, even if it was months or days. It’s the moment where America crystallises the notion of a dream that never came to be. It’s post-war, monetary abundance, a jet-finned car in every garage, TV dinners, TV in the living room, self-cleaning kitchen, wives with hairspray and petticoats, the Space Race. There is faith in the future of America, and that’s what everyone in the movie talks about. Then Kennedy is murdered, and Vietnam continues, and the dream dies. In fact, the dream lives on, but as a ghost. It haunts the nation. It fans hubris. It’s that ghost which is telling people we should make America great again.

Was the main location – Elisa’s apartment she shares with Giles – always above a cinema?

Yes because I always wanted the light and the dialogue to come through the floor. I thought that was really neat. She always has these movies playing. She’s silent, so I’ve got to give you an idea of what’s showing in her head. And I’ve got to show that she makes eggs, masturbates, shines her shoes and dreams of water. She loves musicals. She has very few possessions. Those things end up defining the characters.

Was there a particular film of Sally’s that made you think to cast her? I, personally, am a fan of Happy-Go-Lucky.

Yes, that was key. The three key movies for me were… Actually, the first one is not a movie. I saw the series Fingersmith, the BBC series, which is remarkable. She falls in love with a woman and they have beautiful loving sex, and I thought, I love the way she did it. There was no titillation. There was no sparkle in the eye. It’s just that she likes to have sex with a woman, and that’s the way it is. It’s a piece of character, it’s not the point. I love that. And I love the way she handled it. I didn’t want to do a bestiality movie that was perversion and schoolyard gossipy salivation. They just love each other. It doesn’t matter that he’s an amphibian man or any iteration of the other. The important thing is that they fall in love and they make love. Period.

Then I saw her in Happy-Go-Lucky and I thought she can achieve this state of grace. She is blissful, but alive. Then I saw her in Richard Ayoade’s Submarine, where she’s a secondary character. The way I cast actors is not through the way he or she delivers lines, it’s the way he or she listens to the lines being spoken by others. Or by the way they look at the the other actor. I just thought, this is it. If I create a great creature and she looks at it like a man in a rubber suit, the film dies. If she looks at it like a creature, it lives. She had such a massive crush on the creature. For real. Sally, not the character.

It’s strange for you to say “bestiality” as, on a cold technical level, there is that element to the story.

It’s not a term that’s present. There’s no sexual act in the world that is perverse unless you make it perverse. I think there’s much more perversity in a Victorian kiss on the cheek than in a catalogue of positions involving people who care passionately for one another. Perversity is always in the eye of the beholder. It goes beyond questions of good or bad taste. They’re obviously not graphic. They’re done with such love and such belief that it’s the right thing to do. There is no oblique emotional titillation. And it’s the same way that I treat monsters or apparitions – ‘Look, there’s a ghost! Look, there’s a faun!’ They make love. It’s up to you to be scandalised or not. It says more about the person scandalised than the act itself when somebody says, ‘That sexuality should not exist.’ Why not? It’s there. It does exist. Why is it not human? It’s a position I simply do not understand. Unless it’s a non-consensual, violent act or forced. If it’s not that, I think everything is. Sex is like pizza. Bad pizza is still good. And good pizza is great.

In the past your films have had this erotic element to them, but it’s rare that you’ve actually used a sex scene.

I would agree. There is a sex scene in The Devil’s Backbone, but it’s very twisted and painful. There’s a beautiful sex scene in Crimson Peak between Edith and Thomas which I like a lot. It’s different here, because to show a female character masturbating… some men have a lot of trouble with that.

Your film offers quite a damning indictment of heterosexual relationships.

Yes. The idea for me is that there is more power play and more submission in the relationship between Strickland and his wife. He’s screwing her and covering her face. Zelda and her husband are in stasis. She hasn’t talked to him in years. She just cooks. The question for me is: can we find beauty in the alternative possibilities that life offers us?

Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon feels like an analogue to this film. Though it feels unique in the annals of monster movies for the human character to instigate a romance with the monster. She’s never scared.

There’s a difference between saying the monster got the girl and the girl got the monster. That’s what happens in this one. She rescues him. The first time she sees him he has a wound on his left hand side, and is bleeding. Later, she has a wound in the exact same place. They rescue one another. To me, the image that is key in Creature from the Black Lagoon is the monster carrying the girl when she’s unconscious. But that is an image of horror. In The Shape of Water, that same image reflects a sense of great love.

Creature from the Black Lagoon is a very scary film.

Yes, when it attacks the guys in the tent, it’s brutal. But also, what I love about that movie, is the moment when the creature is swimming right underneath Julie Adams. That is beauty. Pure cinematic perfection. I fell in love with Julie Adams and the creature when I was six. I watched that film as a kid – and I couldn’t put it in to words at the time – but it’s a home invasion movie. The creature is happily living in his lagoon, and this bunch of hoodlums come in, invade his house and then kill him. For me it’s almost a metaphor for the transnational invasion of South America. That why I have the origin element in this movie.

Shannon is almost identical to one of the guys in Creature from the Black Lagoon.

That was the idea! The idea of the film was to depict a super-secret government agency, but not show it through the eyes of the scientist or the people in charge, but those who clean the toilets. It is important that the people joining together to save the creature are all invisible. Sally Hawkins is a woman, a mute and a cleaner. Octavia Spencer is invisible because she’s African-American. Giles because he’s a closeted gay designer whose time of peak artistic worth has passed. And the Russian guy can’t even use his own name. His job is to be invisible. Then you see Ken and Barbie and Ken is a dominating, brutal asshole.

At the beginning of the film there’s a cinema owner and he’s complaining that no one goes to the cinema any more. Is there a commentary here?

That’s more or less what was happening in 1962. Families weren’t going to the cinema because the TV was on. I’m trying to say that we’re in exactly the same world. The movie is about today. Racism, sexism, gender issues, discrimination, everything. They had it in ’62 and we’ve got it now. It’s still pretty good if you’re a WASP, but the minorities – no matter who they are – they’re the “other”. You also had the Cold War, which is back now in a big way. And also you had cinema, which was considered dying. And it really isn’t. It’s transforming.

I saw it as the monster experiencing something new. Which might now be considered a rare thing in Hollywood.

Yes, he doesn’t understand what he’s looking at. The scene was a little longer. I wanted to have him point at the screen and ask, ‘What is this?’ in sign language. But for some reason, when he signed, I felt the guy in the suit. I couldn’t risk it. If you do it wrong once, the whole illusion is destroyed. The one person who actually enjoys the movie is the creature. Everyone else is sleeping.

The Shape of Water is released 14 February. Read our review.

The post Guillermo del Toro: ‘Perversity is always in the eye of the beholder’ appeared first on Little White Lies.

Elenagorgeous climate change

ElenaI love Mia...

With the arrival of every new American Frontier flick, the same question resurfaces: “Has the Western had its day?” It’s a setting that’s fascinated filmmakers and audiences for decades, and in 2018, the setting dutifully endures. In Robert and Nathan Zellner’s first feature-length directorial team-up, the brothers attempt to bring some much-needed new energy to the yawning American plains. There might be gold in them there hills, but it takes a great deal of patience to mine from the fairly rocky surface of Damsel.

Comeback kid Robert Pattinson cuts a handsome figure as the gentile lone ranger Samuel Alabaster, on a mission to relocate his sweetheart Penelope (Mia Wasikowska) so that they might be wed. He enlists the help of a down-on-his-luck preacher (played by Robert Zellner), and brings along a very sweet miniature pony named Butterscotch as a wedding gift for his blushing bride-to-be. Pattinson’s made a name for himself as a gritty indie darling following his mesmerising turn in Good Time, but Damsel affords him a chance to prove his comedy chops – he’s got ‘em alright.

He’s reunited with his Maps to the Stars co-star Wasikowska, who delivers a feisty performance as the titular damsel Penelope, though to say much more about their characters would be to spoil the delightful twists which come thick and fast in the early part of the film. Less of a spoiler is the problem this creates – Damsel seems to quickly run out of steam, a little like a rambling twanging guitar ballad which descends from soulful melody into crooning chaos.

It’s a noble attempt to subvert genre expectations, creating a slapstick spaghetti western anchored by charming lead performances from Pattinson and Wasikowska, but there’s a sense that the story stops fairly quickly, and is padded out by some predictable filler material. This isn’t to say that Damsel is without its merits, as there are many small moments which raise a chuckle (see one withering response given by a Native American character when Zellner’s preacher offers him a proposition) but it feels like a series of ideas rather than a fully-realised feature.

The Old West looks beautiful too, with lush green pines contrasting against the clear babbling brooks, and The Octopus Project providing a brilliant score which will bear repeat listening. Worth a mention too is the costume design, particularly the attention paid to Samuel’s get-up. It’s a shame then that the film does run long, dragging its feet in the second half. It sets a jaunty pace it can’t quite keep up with, and it’s a crying shame there isn’t more given to Pattinson and Wasikowska in terms of story. The ambition and creativity of the Zellners is admirable, but beneath some initial fancy footwork, there’s not much more to see.

The post Damsel – first look review appeared first on Little White Lies.

A common trait among Werner Herzog’s male protagonists – from Timothy Treadwell to Fitzcarraldo to Aguirre – is a flagrant disregard for their own personal safety in pursuit of something greater. It’s tempting to think of Herzog only in these heavily romantic terms. Yet with 1974’s The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, a short documentary about ski jumper Walter “Woodcarver” Steiner, the idiosyncratic German director reveals something more.

It makes sense that Herzog would choose to make a sports movie centred around a pursuit as bizarre as ski-jumping. Watching it is like being dropped into a strange, apocalyptic future, where wiry men wearing space-age helmets careen down long, purpose-built ramps before cannoning off at the end, until they are inevitably brought down to earth, either with expert grace or immediate destruction.

Few other sports have the ability to inspire awe to fear in spectators simultaneously, and indeed most of Steiner’s agitation in the film concerns his personal safety, judges extending the height of ramps so that competitors will reach ever greater distances at even greater risk, and not paying attention to weather conditions that would make landing on snow from a great height, well, risky.

To Herzog’s mind, Steiner was the greatest ski flyer of the 1970s – ski flying having derived from ski jumping with a view to achieving greater distances. When we meet Steiner, he appears to be at a crossroads, where his love of the sport has become complicated by his own mortality. “We’re approaching the limit,” he says at the start of the film, suggesting that were it not for the thrill of flying, he might go back to jumping from shorter ramps.

It’s here where the kinship between Steiner, Treadwell and Fitzcarraldo begins to emerge, and it’s here that Steiner’s calmness calls to mind another of Herzog’s great leading man, Bruno S. In one sense, Steiner is a lens through which all of Herzog’s protagonists can be viewed, something also reflected in the shots of the ski jumps themselves. The extreme slow-motion, coupled with the sheer length of time Steiner spends in the air, serves to emphasise the oddness of his body shape, and the oddness of the action in general. “Inhuman” is how Herzog describes it at one point, which should be understood as a very literal description – this animal is not behaving as we would expect this animal to behave.

A preoccupation with animals is a recurring motif in the cinema of Werner Herzog : psychedelic iguanas in Bad Lieutenant; using a turtle to explain the origins of the world in Fata Morgana; dancing chickens at a roadside attraction in Stroszek; the focus on the cave paintings of the horses in Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Herzog’s classic “the common denominator of the Universe is chaos, hostility and murder,” quote from Grizzly Man is not about war and violence so much as it is about the unpredictability of human behaviour. He shows this whenever an animal pops up in one of his films – it’s just that in the case of The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, the animal happens to be human.

One thing to say about Herzog that sometimes gets overlooked is that he’s a populist. He’ll pop up in Jack Reacher, or extol the virtues of Wrestlemania, because in his mind, that’s where his films culturally sit. This absorbing documentary deliberately plays up to the tropes of a sports movie, shooting the training regimes of Steiner’s Soviet Union opponents and utilising a rousing, anthemic soundtrack for the great landings and moments of adulation (think Any Given Sunday but for ski jumping). And it does so because ambition, rivalry, athleticism and human drama are common across all sport – even the weird ones you only remember when the Winter Olympics are on.

The post Werner Herzog’s ski jumping film is essential viewing this Winter Olympics appeared first on Little White Lies.

Elena"Poppe’s decision to remove politics from a story entirely motivated by the political leanings of a far-right extremist don’t sit right – the end result is a harrowing horror film more than anything else. You gain only a sense for the senselessness of it all, and for many, it’s not necessary to watch a film to understand that"....

Making a film based on a real-life tragedy is an incredibly difficult thing to do well. While it’s embedded in human nature to attempt to find order in chaos, there’s always the potential for art about the senseless wasting of life to feel parasitic and voyeuristic. Erik Poppe, in fictionalising the mass shooting of Norwegian teenagers at a summer camp, attempts to tread the delicate line between exploitive and necessary filmmaking. He doesn’t always manage to do so well.

It is a film that will undoubtedly spark a debate about whether or not it is necessary to replay tragedy on the screen quite so vividly – coming only a few days after another mass shooting in the US, one questions whether we need a fictionalised reminder when the reality is visible on every news screen. It’s difficult to tell who Poppe’s audience is, as many will remember the vivid news reports from the summer of 2011, and the images of shooter Anders Breivik on trial that followed in the aftermath.

To his credit, Poppe does a decent job of not making the film about the perpetrator. The story centres completely on Kaja, a teenager with political aspirations attending the Utoya summer camp with her younger sister. Opening with the Oslo bomb attack that preceded the Utoya shootings, there’s an impending sense of dread right from the start, but even knowing what’s yet to come, the sound of the first shots ringing out is still enough to make your blood run cold.

But we’ve seen it all before – in Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, made in the aftermath of the 1999 Columbine High School Massacre. The same over-the-shoulder tracking shots reappear in Utoya, and the same inconsequential details of adolescence reveal our frailty as human beings. The one-shot take and runtime the same length as the actual shooting make it feel interesting, but unfortunately there are also a couple of overwrought clichés which devalue any impact the film might have.

It’s clear that wounds the events of Utoya have created in Norwegian culture run deep, and the film is aided by a strong performance lead from Andrea Berntzen. But Poppe’s decision to remove politics from a story entirely motivated by the political leanings of a far-right extremist don’t sit right – the end result is a harrowing horror film more than anything else. You gain only a sense for the senselessness of it all, and for many, it’s not necessary to watch a film to understand that.

The post U-July 22 – first look review appeared first on Little White Lies.

ElenaI dont care if the film is all about a mute Amish person.... I AM WATCHING HIM.

Back in 1970, Robert Altman unleashed M*A*S*H on an American public facing a daily bombardment of news images from Vietnam. Ostensibly set in Korea, the film followed field surgeons, Hawkeye (Donald Sutherland) and Trapper John (Elliott Gould) as they raised a middle finger to military discipline and pursued the insistent humiliation of female commissioned officer, Hot Lips (Sally Kellerman).

Altman would later argue that the film was a study in unrestrained male toxicity, but its complexities – or failings, depending on your perspective – lay in the audience’s relationship with these two antiheroes; the encouragement to side with wisecracking bullies, laugh along with their bantz or simply view their behaviour as a symptom of circumstance.

For his fourth feature, 16 years in the planning, Duncan Jones resurrects Hawkeye and Trapper John, transposing the characters to some time in the late 2030s. The exact period isn’t specified, but news reports of a hearing to determine the rights of a certain Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) place us several years after the events of Jones’ 2009 debut, Moon.

With his Hawaiian shirt, handlebar moustache and penchant for a martini, there’s little mistaking Paul Rudd’s Cactus Bill as anything but a simulacrum of Gould’s Trapper. And here Hawkeye is played by Justin Theroux, fresh out of That ’70s Wig Emporium. Both served in the US army, and now perform underground surgeries in Berlin, where Cactus awaits some moody documents to escape back to the States with his young daughter, having gone AWOL from duty.

Jones’ invocation of M*A*S*H for his pair of ne’er-do-wells presumably serves as a bid to blindside audience sympathies; bringing us on board with devil-may-care attitudinal pose before undermining our allegiance with unsavoury behaviour. Altman’s film largely succeeded in this regard not just by virtue of its stars’ irrepressible charisma, but by how embedded the characters were in cultural and political specificity. Whatever the moral discomfort of M*A*S*H’s subjectivity, it existed in a hermetic and wholly inhabited world that posed contemporary questions of its characters, however glib the answers may have proved.

In Mute, any such provocations serve as mere window dressing, a shortcut to character and drama that runs skin-deep. Allusions to Kabul and ‘New Kandahar’ suggest the US army is still in Afghanistan, but it’s an elided plot point only there to explain the duo’s presence in Berlin. Cactus’ status on the brink of escape from capture affords his character a sense of direction, while Altman’s complexity with regards the repressed nihilism of Hawkeye is simplified to the point of idiocy by making Theroux’s Duck… well, let’s just say he’s not a dude you’d want hanging around your children.

The lack of political engagement – of saying much about anything – extends to Mute’s primary narrative, a quest for a missing girl. Jones’ shortcuts to character are exemplified in Alexander Skarsgård’s silent lead, Leo. In a science fiction film populated by outsiders, how might one best suggest that Leo is not made for this age of vice and technology? Yep, he’s Amish. As a community barely represented onscreen outside of Harrison Ford’s tumble in the hay, one might at least expect some kind of cursory examination of the inherent spiritual conflict between a tech-dependent future and its backwards-looking inhabitant. But no, Leo just doesn’t have a phone and his mother wouldn’t let doctors fix his larynx following a childhood accident.

The missing girl in question is Leo’s girlfriend, Naadirah (Seyneb Saleh). Jones has cited Paul Schrader’s 1979 film, Hardcore, as a key influence on Mute. It’s a film that dealt with the tensions between ultra-conservatism and perceived moral degeneration, between the post-war and post-Swinging ’60s generations, between small town mindsets and big city urbanity. None of these questions are transposed to Mute in any shape or form, beyond the binary distinction of Naadirah being ‘complicated’ and Leo being ‘kind.’ This sad, simple clown travels to one place, picking up a clue to another, all because he loves her and wants to give her the bed he’s been whittling in his lock-up.

If there’s one character that comes out with its dignity largely intact, it’s the city of Berlin. The wealth of accents on display suggests a thriving immigrant community of misfits, the city’s each-to-his-own liberal credentials appearing to have survived the intervening years. Yet the neon-drenched production design suggests further shorthand. The future’s certainly bright, with Netflix seemingly invested in city planning, all the better to shill their Dolby Vision enhancements. It’s a generic sci-fi vision, leagues away from the inhabited textures of Blade Runner, a film whose visual style served its melancholia through its very form.

Things might have been better had the dramatic beats landed, but Mute possesses so little sense of style, of directorial muscularity, that it fizzles out long before its 125 minutes are up. It’s a film seemingly lacking in movement, its few recourses to kineticism (in the form of two driving sequences) prove shockingly edited and misplaced respectively, while Clint Mansell’s score works overtime to plaster the directorial cracks. A dust-up with a German lump who’s been hanging in the background of scenes like Chekhov’s Fist, disappears before it even begins, as though a scene is missing.

The promise of Jones’ first three features – yep, even Warcraft – all but vanishes with Mute. He’s always been an easy guy to root for, so here’s hoping that with this passion project out of his system, his next film sees that promise fulfilled.

The post Mute appeared first on Little White Lies.

ElenaHAPPY VALENTINES DAY TOR!!! Sending you all love from Paris xoxoxo

Elenayum!

ElenaWow - what a terrible way of dealing with harassment. Instead of the perpetrator being thrown off the bus, the victim can choose to get off anywhere in the middle of the night on their way home.

Elenayellow collar on grey dog... hundo p

“I like wearing simple and comfortable clothing. I love jeans—-these are by Nili Lotan. My cape is Saint Laurent. And cozy boots are from MM6.

I usually wear my vintage 501 Levi’s. I rarely wear dresses and for me, I like slim silhouettes. I’m very casual too. I’m never really dressed up.

Vintage Levi’s and all forms of denim are a wardrobe staple. Coats. Capes. Shirts. Sneakers. And low heeled boots.”

– Linda Rodin as told to Atelier Doré

Everyone at our Atelier loves Linda and her adorable dog, Winks. For more style inspiration and photos of Winks (there are never enough photos of Winks!), peek Linda’s Instagram.

ElenaIs this showing in the US? Are people talking about it?

the review is pretty damning "the film’s message – whatever it was – is lost. It leaves us empty handed and with an uneasy feeling. In the same way that we feel numb after so much bad news, sitting through 80 minutes of is often overwhelming. Our New President would perhaps work better as a museum exhibition, a collection of artifacts to be gawked at and learned from"

The 2016 US presidential election feels a long time ago. How many lifetimes have flashed before our eyes with every new travel ban, deportation story or nuclear threat? Stepping back just six months practically feels like time travelling. Maxim Pozdorovkin’s documentary, Our New President, allows us to revisit these recent memories – but from a perspective that’s equally fascinating and horrifying.

Stringing together dozens of YouTube clips, wooly conspiracy theories and state-run newscasts in Russia, the film dumps viewers into the deep end of the fake news pool during the election and a few months into Trump’s presidency. The found footage is then cobbled together for a sometimes comedic and often bewildering effect. At times the documentary looks both like a horror movie and an ambitious art film.

However impressive the collection, there’s little beyond shock value in watching Russians on vlogs and TV shows praising Trump. In tearing apart Hillary Clinton’s reputation, the admiration heaped upon Trump fuelled a cult of personality that’s refashioned the real estate tycoon as a folk hero. It’s not likely an accident that most of the self-filmed tributes to the new Commander-in-Chief are from men young and old, with women typically used objects in these videos if they’re there at all.

Somewhere between a bizarre video attributing Clinton’s “poor health” to a mummy’s curse and music videos where a rapper imposes Trump’s face over his own, the film’s message – whatever it was – is lost. It leaves us empty handed and with an uneasy feeling. In the same way that we feel numb after so much bad news, sitting through 80 minutes of is often overwhelming. Our New President would perhaps work better as a museum exhibition, a collection of artifacts to be gawked at and learned from.

The haphazard assortment of footage is a peek into the manufactured reality running unchecked on the internet. The film’s sources looks to be laid out in chronological order, but some of the clips seem to have come from the lunatic fringe, and not the state-run outlets. This unfortunately dulls the chilling thought of an organised attack on the media with silly fantasies.

There’s no buffer between the viewer and the absurdities spewed up online. Reality and illusion are blurred so much here that if the filmmaker inserted a fake example of fake news, one would have trouble spotting the lie. A well-made collage may be art, but it doesn’t always connect with its audience, and if this documentary’s purpose is to inform then that may be an issue. There’s a 12-minute version of Our New President that I found to be much more effective. There’s no need to get lost in a museum of nonsense for so long.

The post Our New President – first look review appeared first on Little White Lies.

ElenaI am excited about this...

From Chinatown to The French Connection, Saturday Night Fever to The Last Picture Show, many of the era-defining American films of the 1970s spawned unusual, low-key sequels, each concerned with the notions of legacy and transience. Where the great New Hollywood masterpieces were nihilistic, their sequels, like Jack Nicholson’s The Two Jakes or Sylvester Stallone’s Staying Alive are fatalistic. They are gentler, more melancholic films, preoccupied with a sense of longing for the past.

Richard Linklater’s Last Flag Flying, a “spiritual sequel” to Hal Ashby’s 1971 classic The Last Detail (the names and a few facts have changed), recalls the greatest of these sequels: Peter Bogdanovich’s Texasville. Both are works of generous, compassionate Americana which revisit the characters of the originals at middle age, and each is concerned with the passage of time, with missed connections and paths not taken.

Last Flag Flying is set in 2003 and sees former Navy man “Doc” Shepherd (Steve Carell) reunite with ex-Marines Sal Nealon (Bryan Cranston) and Richard Mueller (Laurence Fishburne), 30 years after they served together in Vietnam – to help transport the body of Shepherd’s son, recently killed in Iraq, to be buried at home in New Hampshire. In the classic Linklater tradition, it’s a profound reflection on American values played as a hilarious and profane hangout film.

It’s an American road movie where the sense of America is not in the places they visit, but in the tenor of the conversations between the central trio; the way they bicker, joke and reminisce about everything from their time in the forces to the merits of Eminem – think Slacker among the Marines.

The sharp edges and bleak loquaciousness of The Last Detail have been modulated by age – these men were once fighting the future, now they’re negotiating with their past. It’s a call and response to The Last Detail, treating the events of Ashby’s film like a half-formed memory, a piece of history plucked from the recesses of the national consciousness. It’s a film about a changing country, about what’s been gained and lost in the gulf between Vietnam and Iraq, between New Hollywood and the contemporary American cinema.

Time is the unifying theme of Linklater’s work, and his sequels and remakes feature some of his most perceptive takes on the topic, from ageing in the face of love’s ever-fixed mark in the Before films to the precarious boundary of adulthood in Everybody Wants Some!!.

It feels disorientating, even uncanny, to see the recent past treated as a bygone era, but it provides a different angle from which to consider a war that dominated the public discourse in the first decade of the 21st century. In this sense, it is closer in essence to the great home front movies of the 1940s than to contemporary Iraq movies like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker – a step removed from the fighting, but right at the heart of a more spiritual conflict. Last Flag Flying may feel like a film out of time in the present moment, but it’s a terrifically funny, deeply moving picture whose time will surely come.

The post Last Flag Flying appeared first on Little White Lies.

ElenaSteve, from now on I am going to share recycling tips and up cycling posts... JUST FOR YOU

Before you throw it out, think of different ways you can use that item. Look at the T0p 5 Recycled Art Projects that you created and selected as the best!

Thank you for the many years of support and the astounding projects you all create! We can’t wait to see what you make in 2018!

#1: Turn magazines into a stunning vase!

#2: Turn your old DVD cases into a unique Vertical Planter!

#3: Turn Pallet Wood into a Stylish Coat Rack!

#4: Turn a pallet into a DIY Coffee Bar!

#5: Upcycle an old treadle base into a sewing machine chair!

Read 2017 Top 5 Recycled Art Projects You Created by HeatherStiletto on Recyclart!

ElenaWOOOOMAN

– Jane FondaYou think you’re broken, but you’re really broken open.

ElenaI saw Three Billboards last weekend and had a panic attack half way through it. I didn't want to scare my date - we were sitting in the middle of the row in the middle of the theatre - so I calmed down and then cried through the rest of the film. This has never happened to me before. I can usually watch anything. But I feel like for anyone with any history of the following, this movie should come with many trigger warnings. Suicide, rape, cop violence, domestic abuse, torture and revenge themes. While the genre is clearly comedy noir and the violence is grotesque, I was angry that none of these themes were treated with any real empathy. I recommend a valium or a very specific "dont give a shit" state of mind if you do watch it. The acting is great, as is the script. The Cohen Brothers would have turned this into a masterpiece.

Frances McDormand and Sam Rockwell win for roles in the small-town drama while an all-female list of presenters celebrate an important year for women in Hollywood

Related: Women take centre stage at Screen Actors Guild awards – in pictures

The cast of Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri won big at the 24th annual Screen Actors Guild awards during a female-powered ceremony.

Continue reading...ElenaRachel! Its in ya hood ....

Art Los Angeles Contemporary, the International Art Fair of the West Coast, returns from January 25 to 28 at the Barker Hangar in Santa Monica, CA. As part of the ninth edition of the fair, ALAC welcomes over 60 new and returning exhibitors from Europe, Latin America and Asia, as well as the return of its young Freeways section. Throughout the fair weekend, ALAC will host on-site talks and lectures about contemporary art and its role in both Los Angeles and throughout the world, presented by key members of Los Angeles’ art community. Find out more information and purchase tickets at artlosangelesfair.com.

(Sponsored)

Contemporary Art Daily is produced by Contemporary Art Group, a not-for-profit organization. We rely on our audience to help fund the publication of exhibitions that show up in this RSS feed. Please consider supporting us by making a donation today.

Elenanow following this guy on instagram! beautiful

An art form bringing new life to black and white images from the past, is offering different insights into moments from history – through colour. Irish artist Matt Loughrey began ‘colourising’ vintage photographs after NASA, during 2015, released a selection of nostalgic images of the 20th Century American-Societ space race. Among them were profiles of astronauts and engineers as well as celebratory and tense scenes from the command centre. For Loughrey, seeing the photographs stirred up memories of hearing his father tell stories about watching the space race. “We had encyclopaedias and everything was monochromatic – it felt distant,” he told the National Geographic.

At this time Loughrey had recently colourised an image of his own Grandmother and subsequently experienced a feeling having pulled her out of the past. When his seven year old son asked him, “was the world always in black and white?” he began to consider how colourising the NASA photos might effect a younger audience – and set about finding out. The process involves painting using a digital pen and a single photograph can take in excess of four hours to complete, sometimes as many as 12.

Astronaut John Glenn in 1962 during Project Mercury. Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth in 1962. Image colourised by Matt Loughrey

Since the NASA project the artist, who is based in Westport Ireland, has colourised many different images and stories. These include 20th Century polar explorers who risked their lives in the Antarctic – among them, Yorkshireman Frank Wild who was on board the Quest in 1922 when Ernest Shackleton died, Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson and South Pole explorer Lawrence Oats, who, when he was fearful that he was slowing his group down, deliberately walked into a blizzard uttering his famous final words “I am just going outside and may be some time”.

His Instagram account My Colourful Past shows the breadth of his work – famous Richard Avedon shots of Marilyn Monroe, Titanic survivors, Amelia Earhart and Lee Harvey Oswald – and with 12.2k followers, that there is a real appetite for it. “The project as a whole is about recognising the past in a new light in order to educate, colourisation bridges a gap between history and art like no other format,” Loughrey says.

The post The art of the colourised photo appeared first on The Chromologist.

ElenaI love anything written about Antarctica

Many know of the epic race in 1910 between Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott to be the first to reach the South Pole, and the tragic end met by the latter explorer.

Most people have also heard of the heroic leadership of Ernest Shackleton, who managed to save the lives of all of his men when their attempt to traverse Antarctica in 1914 went horribly awry.

Fewer, however, are familiar with another tale of Antarctic adventure, that of the almost five months Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd spent alone at the bottom of the world in 1934.

While Byrd was one of the most celebrated figures of his time (receiving an unprecedented three ticker tape parades), his fame has slipped beneath that of other polar explorers, perhaps because his adventure was of a strikingly different kind. Rather than involving teams of men, and sweeping treks across land and sea, Byrd didn’t travel with anyone else, or cover any geographic distance at all. Rather, he stayed, by himself, in exactly one place: a tiny shack buried under snow and ice. Yet while Byrd’s journey was not outward but inward, his expedition to the farthest reaches of solitude covered a significant amount of ground, circumscribing the spirit of man and his place in the universe.

“it is something, I believe, that people beset by the complexities of modern life will understand instinctively. We are caught up in the winds that blow every which way. And in the hullabaloo the thinking man is driven to ponder where he is being blown and to long desperately for some quiet place where he can reason undisturbed and take inventory.” –Richard E. Byrd, Alone

By 1934, the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration” had drawn to a close. Much of the continent had been explored and mapped, and the pole had been attained through “manual” means (dog sled and skis) and ample struggle. As technology progressed, and the Heroic Age became the “Mechanical Age,” more territory was covered with increasing ease, and few polar “firsts” remained.

Byrd was a highly decorated naval officer and aviator; as a military pilot, the third man to fly non-stop over the Atlantic, and a polar explorer, he earned twenty-two citations and special commendations including the Medal of Honor, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Navy Cross, and the Lifesaving Medal (2X).

Of those that did, Byrd had already bagged the most prominent, acting as navigator on the first flights to reach the North and South Poles.

But as Byrd admits in his riveting, must-read memoir, Alone, despite these accomplishments, and the voluminous ticker tape which followed them, their aftermath still left him feeling a “certain aimlessness.” He not only longed to traverse another fresh frontier and tackle another daring, publicly-recognized challenge, but to address a certain restlessness he felt in his private, personal life — a niggling feeling that “centered on small but increasingly lamentable omissions”:

“For example, books. There was no end to the books that I was forever promising myself to read; but, when it came to reading them, I seemed never to have the time or the patience. With music, too, it was the same way; the love for it — and I suppose the indefinable need — was also there, but not the will or opportunity to interrupt the routine which most of us come to cherish as existence.

This was true of other matters: new ideas, new concepts, and new developments about which I knew little or nothing. It seemed a restricted way to live.”

To address these yearnings, Byrd came up with a plan that aimed to kill two birds with one stone: during the long, dark Antarctic winter, he would man, alone, “the first inland station ever occupied in the world’s southernmost continent.” While the rest of his expedition team remained at the Little America base along the coast of the Ross Ice Shelf, Byrd would set up camp at Bolling Advance Weather Base on Antarctica’s colder, even more barren interior.

The daring (some would say foolhardy) endeavor had an ostensible scientific purpose — that of making weather and celestial observations and gathering data. But Byrd admitted he “really wanted to go for the experience’s sake” — “to try a more rigorous existence than any I had known.”

The experience would certainly be physically rigorous.

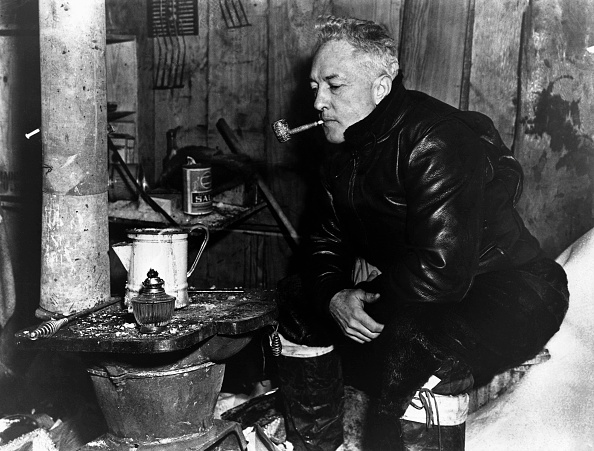

Though Byrd would stay put in a shack buried under the snow, he would emerge through its trap door multiple times a day to take metrological readings, and would still have to survive in “the coldest cold on the face of the earth.” Temperatures would routinely hover around -60 outside and be subzero even inside: it would sometimes be -30 when Byrd arose from his bunk in the morning and the walls and ceiling of the hut would slowly become encased in a layer of ice. Should something go wrong, help was over 100 miles away, across a terrain that would be impossible to traverse in the trough of the Antarctic winter.

The psychological rigor of the experience, however, would be just as intense.

The lonely landscape would not only be cold, but lacking in light; once the sun sets during the Antarctic winter, it doesn’t rise again until the spring, ushering in a “long night as black as that on the dark side of the moon.”

As “perhaps the most isolated human on earth,” no other person, seen or unseen, would exist within a 123-mile radius, and Byrd’s only contact with the outside world would be intermittent radio exchanges he made with the men back at Little America; even in these communications, while Byrd would be able to hear the men at the other end, he would only be able to respond through Morse code. Weeks would go by without him uttering a single word.

Existing in a “world [he] could span in four strides going one way and in three strides going the other,” Byrd would enjoy no external stimuli beyond his books, his phonograph, and what he could observe in the icy landscape. There would be almost no deviation in his daily routine for months on end; “Change in the sense that we know it, without which life is scarcely tolerable, would be nonexistent.”

Finally, the silence accompanying this solitary sojourn would be “taut and immense” — filled with the kind of “fatal emptiness that comes when an airplane engine cuts out abruptly in flight.”

Yet all these considerations made the plan more compelling to Byrd, not less:

“Out there on the South Polar barrier, in cold and darkness as complete as that of the Pleistocene, I should have time to catch up, to study and think and listen to the phonograph; and, for maybe seven months, remote from all but the simplest distractions, I should be able to live exactly as I chose, obedient to no necessities but those imposed by wind and cold, and to no man’s laws but my own.”

Byrd desired to “know that kind of experience to the full, to be by himself for a while and to taste peace and quiet and solitude long enough to find out how good they really are.”

During his stay at Latitude 80° 08′ South, Byrd got his wish, as well as much more than he bargained for.

“Yes, solitude is greater than I anticipated.” –Richard E. Byrd, Alone

While Byrd did not travel far on this expedition, the insights he garnered are in many ways more useful than those brought back from the far-flung treks of traditional explorers. They deal with the issues the everyday man faces — loneliness, isolation, unvarying routine, lack of change — writ large. Byrd’s challenge would be that of finding meaning in the mundane — the same challenge we all face, simply to a lesser degree.

During months of uninterrupted introspection and an intensity of voluntary solitude few humans have ever experienced, Byrd gleaned many insights on these issues. Here are some of the realizations he reached during his solitary sojourn at the bottom of the world:

In 1947, Byrd revisited his hut at “Advanced Weather Base,” and picked up and smoked a pipe he had left behind 12 years earlier.

The overarching theme that runs through Byrd’s experience with solitude, is the way it helped him pare away the superfluous in order to focus on the truly important and meaningful:

“My sense of values is changing, and many things which before were in solution in my mind now seem to be crystallizing. I am better able to tell what in the world is wheat for me and what is chaff.”

As we’ll see, this sifting process would concern Byrd’s more abstract ideas and philosophy. But it would alter his views on material possessions as well.

Adjoining Byrd’s small shack were two snow tunnels that held an ample supply of all the provisions a man might need to survive by himself for half a year: candles, matches, flashlights, batteries, pencils and writing paper, laundry soap, food, etc. Yet beyond these essentials, along with a shelf of books and a box of phonograph records, Byrd had few of the creature comforts, conveniences, and entertainments that fill the abodes of most modern men. He had essentially one set of clothes, one chair, one little stove to cook food.

In taking stock of the distillation his existence had undergone, Byrd reflected:

“Yet, wasn’t this really enough? It occurred to me then that half the confusion in the world comes from not knowing how little we need.”

Being forced to live the simple life, Byrd decided, “was very good for me; I was learning what the philosophers have long been harping on — that a man can live profoundly without masses of things.”

Despite frigid, potentially inertia-creating temperatures, Byrd got in bouts of exercise nearly every single day. (The next time you think it’s just “too cold” to go outside and move your body, remember this journal entry of Byrd’s: “It was clear and not too cold [today] — only 41 degrees below zero at noon.”) He felt his daily exercise helped preserve not only his physical health, but his mental health as well.

In the mornings, while the water for his tea heated up, Byrd would lie upon his bunk and do fifteen different stretching exercises. “The silence during these first few minutes of the day is always depressing,” he wrote in his journal, and “My exercises help to snap me out of this.”

Byrd also took 1-2 hour walks outside each day (which included doing a dozen different exercises along the way, like knee bends). These jaunts provided him with exercise, fresh air, and a change of scenery, as well as a great deal of mental repose and elevation:

“The last half of the walk is the best part of the day, the time when I am most nearly at peace with myself and circumstances. Thoughts of life and the nature of things flow smoothly, so smoothly and so naturally as to create an illusion that one is swimming harmoniously in the broad current of the cosmos. During this hour I undergo a sort of intellectual levitation, although my thinking is usually on earthy, practical matters.”

“A man had no need of the world here — certainly not the world of commonplace manners and accustomed security.”

The longer Byrd spent isolated from the everyday world, the more he noticed the trappings of civilization falling away, and how “A life alone makes the need for external demonstration almost disappear”:

“Solitude is an excellent laboratory in which to observe the extent to which manners and habits are conditioned by others. My tables manners are atrocious — in this respect I’ve slipped back hundreds of years; in fact, I have no manners whatsoever.”

Byrd even observed that something like swearing, often assumed to be indulged in for one’s own benefit, was in fact largely performative:

“Now I seldom cuss, although at first I was quick to open fire at everything that trued my patience. Attending to the electrical circuit on the anemometer pole is no less cold than it was in the beginning; but I work in soundless torment, knowing that the night is vast and profanity can shock no one but myself.”

Byrd’s hair grew long and shaggy (he preferred to keep it that way, as it kept his neck warm). His nose became red and bulbous and his cheeks blistered from being nipped by hundreds of frostbites. Yet his increasingly barbarous and disheveled look did not bother him in the least, as he “decided that a man without women around him is a man without vanity.”

He shaved his beard “only because I have found that a beard is an infernal nuisance outside on the account of its tendency to ice up from the breath and freeze the face.” He did take a bath each evening, keeping himself quite clean, but he performed this ritual, he notes, not out of a sense of etiquette, but simply because it felt good and kept him comfortable. “How I look is no longer of the least importance,” he wrote in his journal, “all that matters is how I feel.”

Byrd found the process of reverting back to a more basic, “primitive” state interesting and instructive, musing, “I seem to remember reading in Epicurus that a man living alone lives the life of a wolf.”

It’s not that Byrd discovered that manners and other externally conditioned behaviors have no point and kept living like an uncultured barbarian after leaving Latitude 80° 08’ South; on the contrary, once back in the States, he returned to comporting himself as an officer and a gentleman. But he never forgot that civilization is an externally conditioned patina on a rawer way of life, and that much of how we act is a form of theater — a very useful form, but theater nonetheless.

“From the beginning I had recognized that an orderly, harmonious routine was the only lasting defense against my special circumstances.”

While Byrd discovered that a life lived in solitude offered many consolations, he was also very cognizant of its challenges. Mainly, that of being stalked by the incessant specter of desperate loneliness — a loneliness Byrd found “too big” to take “casually.” “I must not dwell on it,” he realized. “Otherwise I am undone.”

To keep the melancholy of isolation at bay, Byrd set about creating a busy, but orderly daily routine for himself. This was not an easy task, he admits, for he describes himself as “a somewhat casual person, governed by moods as often as by necessities.” Nonetheless, during his stay at Advance Base this “most unsystematic of mortals endeavored to be systematic,” as he saw the creation of set habits as vital to preserving his psychic equilibrium.

The keys of Byrd’s daily routine were two-fold.

First, he filled each day with maintenance jobs, always giving himself about an hour to work on each task. Regardless of whether he finished the job or not, once the sixty minutes were up, he turned to the next task, resolving to take up any unfinished work the next day. “In that way,” he explains, “I was able to show a little progress each day on all the important jobs, and at the same time keep from becoming bored with any one. This was a way of bringing variety into an existence.” As he further reflected, by keeping a schedule in this way:

“It brought me an extraordinary sense of command over myself and simultaneously freighted my simplest doings with significance. Without that or an equivalent, the days would have been without purpose; and without purpose they would have ended, as such days always end, in disintegration.”

The second key to the efficacy of Byrd’s daily routine, was keeping his mind off the past and focused on the present. He determined to “extract every ounce of diversion and creativeness inherent in my immediate surroundings” by experimenting “with new schemes for increasing the content of the hours.”

In practical terms, this meant challenging himself to do his tasks a little better each day, thereby keeping his focus on positive improvement:

“I tried to cook more rapidly, take weather and auroral observations more expertly, and do routine things systematically. Full mastery of the impinging moment was my goal. I lengthened my walks and did more reading, and kept my thoughts upon an impersonal plane. In other words, I tried resolutely to attend to my business.”

Extracting more content from his hours also meant trying to make the most of the few diversions he had at his disposal. For example, even though he took his daily walks in different directions from his hut, no matter which way he headed the landscape was pretty much exactly the same — a stretch of white, icy homogeneity to the horizon. “Yet,” Byrd notes, “I could, with a little imagination, make every walk seem different.” As he ambled, he would imagine strolling around his hometown of Boston, or retracing the epic journey that Marco Polo took (which he was then reading about in a book), or even exploring what life was like during the Ice Age. “There was no need for the paths ever becoming a rut.”

When it comes to passing through a challenging, largely unvarying season of life, Byrd observed, one must be able to find worlds within worlds; “The ones who survive with a measure of happiness are those who can live profoundly off their intellectual resources, as hibernating animals live off their fat.”

“why, I asked myself, weary the mind with small reproaches? Sufficient unto the day was the evil.”

Byrd’s only connection to the outside world was a radio he used to communicate with the men back at Little America. But he found that listening to these dispatches often made him feel more anxious, rather than less.

This was especially true when the men back at base shared an item of national or global news. For example, after “Curiosity tempted [Byrd] to ask Little America how the stock market was going,” he realized the query “was a ghastly mistake.” The glum news (this was during the Great Depression), put him in a state of dejection; before leaving the States, Byrd had invested some funds in the hopes of making some money and defraying the expedition’s costs. Now much of that money had evaporated, and he could only sit idly at the bottom of the world, consumed by the impotent feeling of not being able to do a damn thing about it.

“I can in no earthly way alter the situation,” Byrd eventually concluded. “Worry, therefore, is needless.”

He would thereafter take the same Stoic approach to the dispatches he received from Little America, “clos[ing] off [his] mind to the bothersome details of the world” and concentrating only on that which he could control:

“The few world news items which [were] read to me seemed almost as meaningless as they might to a Martian. My world was insulated against the shocks running through distant economies. Advance Base was geared to different laws. On getting up in the morning, it was enough for me to say to myself: Today is the day to change the barograph sheet, or Today is the day to fill the stove tank.”

One might observe, while Byrd couldn’t do anything about global events from his shack in Antarctica, he couldn’t have done anything had he been back home either. Begging an important question for all: Is there any reason to keep up with the news?

There were times during Byrd’s experience that were positively thrilling. Read just a few of the ways he exults in the sublimity of solitude and “the sheer excitement of silence”:

“I realize at this moment more than ever before how much I have been wanting something like this. I must confess feeling a tremendous exhilaration.”

“I came to understand what Thoreau meant when he said, ‘My body is all sentient.’ There were moments when I felt more alive than at any other time in my life. Freed from materialistic distractions, my senses sharpened in new directions, and the random or commonplace affairs of the sky and the earth and the spirit, which ordinarily I would have ignored if I had noticed them at all, became exciting and portentous.”

“This was a grand period; I was conscious only of a mind utterly at peace, a mind adrift upon the smooth, romantic tides of imagination, like a ship responding to the strength and purpose in the enveloping medium. A man’s moments of serenity are few, but a few will sustain him a lifetime. I found my measure of inward peace then; the stately echoes lasted a long time. For the world then was like poetry — that poetry which is ‘emotion remembered in tranquility.’”

“all this was mine: the stars, the constellations, even the earth as it turned on its axis. If great inward peace and exhilaration can exist together, then this, I decided . . . was what should possess the senses.”

“my thoughts seem to come together more smoothly than ever before.”

Yet these moments of elevation did not come without effort, without sacrifice. They were not made possible despite of the difficult, inhospitable conditions of Byrd’s sojourn, but because of them. His reflections upon seeing a stunning display of colors splash across the Antarctic sky, apply just as readily to everything else he experienced on his solo expedition:

“This has been a beautiful day. Although the sky was almost cloudless, an impalpable haze hung in the air, doubtless from falling crystals. In midafternoon it disappeared, and the Barrier to the north flooded with a rare pink light, pastel in its delicacy. The horizon line was a long slash of crimson, brighter than blood; and over this welled a straw-yellow ocean whose shores were the boundless blue of the night. I watched the sky a long time, concluding that such beauty was reserved for distant, dangerous places, and that nature has good reason for exacting her own special sacrifices from those determined to witness them. An intimation of my isolation seeped into my mood; this cold but lively afterglow was my compensation for the loss of the sun whose warmth and light were enriching the world beyond the horizon.”

Byrd could not have seen such sights without traveling to the bottom of the world. He could not have gleaned any soul-expanding insights, without also battling soul-crushing loneliness. There cannot be any sweet without the bitter.

Byrd went looking for, and found, a sense of peace, but, he hastened to explain, the “peace I describe is not passive. It must be won”:

“Real peace comes from struggle that involves such things as effort, discipline, enthusiasm. This is also the way to strength. An inactive peace may lead to sensuality and flabbiness, which are discordant. It is often necessary to fight to lessen discord. This is the paradox.”

While Byrd enjoyed two healthy, insight-filled months of solitude, thereafter conditions at Advance Weather Base unfortunately took a near-fatal turn, and cut short Byrd’s sojourn there.

Something went afoul with the stove he used to heat his hut, so that it began to leak carbon monoxide into his tiny living space. If he turned off the stove at night, however, he would freeze. So he was forced to alternate between shutting it off and cracking open the door for fresh air during the day, and letting it run while he slept. Unsurprisingly Byrd became deathly ill and could barely function, a fact he hid from the men at Little America for two months, not wanting them to risk their lives by launching a rescue mission after him.

Though it may be a cliché, as Byrd approached death’s door, he really did see his “whole life pass in review. I realized how wrong my sense of values had been and how I had failed to see that the simple, homely, unpretentious things of life are the most important.”

When Byrd thought of the work he had come to the base to do, the data he had gathered, it all seemed like dross in the grand scheme of things. He realized that the real heart of life was back at home with his wife and kids:

“At the end only two things really matter to a man, regardless of who he is; and they are the affection and understanding of his family. Anything and everything else he creates are insubstantial; they are ships given over to the mercy of the winds and tides of prejudice. But the family is an everlasting anchorage, a quiet harbor where a man’s ships can be left to swing to the moorings of pride and loyalty.”

Before Byrd got sick, he gained one of his most profound insights, concerning nothing less than the nature of the universe and man’s place within it.

In gazing upon the stunning expanse of dark sky, and the awe-inspiring dance of Antarctic auroras across it, Byrd found not only beauty, but a pattern to that beauty. In listening into the silence of solitude, he heard the flow of a well-orchestrated cadence:

“Here were the imponderable processes and forces of the cosmos, harmonious and soundless. Harmony, that was it! That was what came out of the silence — a gentle rhythm, the strain of a perfect chord, the music of the spheres, perhaps.

It was enough to catch that rhythm, momentarily to be myself a part of it. In that instant I could feel no doubt of man’s oneness with the universe. The conviction came that that rhythm was too orderly, too harmonious, too perfect to be a product of blind chance — that, therefore, there must be purpose in the whole and that man was part of that whole and not an accidental offshoot. It was a feeling that transcended reason; that went to the heart of man’s despair and found it groundless.”

From this realization came no detailed proclamation on the nature of God, on theology, on the true faith or the right denomination. Byrd simply reached a deep conviction that the universe was not a random chaos, but a planned cosmos; that “For those who seek it, there is inexhaustible evidence of an all-pervading intelligence.”

“Part of me remained forever at Latitude 80 08’ South: what survived of my youth, my vanity, perhaps, and certainly my skepticism. On the other hand, I did take away something that I had not fully possessed before: appreciation of the sheer beauty and miracle of being alive, and a humble set of values. . . . Civilization has not altered my ideas. I live more simply now, and with more peace.”

If you plunged into a prolonged period of solitude and silence, away from every besetting distraction, what would happen to your mind? What insights would you discover? Would they be the same as Byrd’s? Different?

While most of us will never experience a state of silent solitude of the prolonged, all-encompassing kind inhabited by Richard E. Byrd, we can all find more pockets of it in our daily lives. We can all shut off the noise for a few moments, and glimpse more clearly those ideas and revelations that ever edge towards consciousness, only to be pushed away by another distraction.

We can all take our own solitary sojourn; we can all explore the deeper dimensions of silence; we can all discover fresh realizations by journeying to a different latitude of soul.

The post Alone: Lessons on Solitude From an Antarctic Explorer appeared first on The Art of Manliness.