On April 11, 2002, Cynthia Powell entered the criminal justice system for the first time in her life, for what could be the rest of her life.

Two detectives for the Sunrise Police Department in Florida had arrested Powell in the parking lot of a Starbucks for agreeing to sell 35 of her Lorcet pills—basically Tylenol with a small amount of hydrocodone—and some of her Soma pills (a muscle relaxant) to an undercover police officer.

Powell, a 40-year-old African-American woman, had no prior convictions and no arrest record. Her occupation was listed on the arrest report as "unemployed." On her criminal history sheet, it's listed as "disabled."

"Anyone who knows my mother knows she's a sweet lady," Powell's daughter, Jacqueline Sharp, says in an interview with Reason. "Even before she went, people would drop their kids off for her to watch them."

In many other states, Powell would have been a candidate for a diversion program or maybe probation. Under Florida's ruthless anti-opioid laws, she received a mandatory minimum of 25 years in prison on charges of drug trafficking and possession with intent to sell.

As fentanyl and heroin use have spiked across the U.S. in recent years, lawmakers and prosecutors have responded by pushing tough new sentences to crack down on dealers and users.

The Pennsylvania Legislature is advancing a bill, pushed by state prosecutors, to restore mandatory-minimum sentences for drug crimes. An Ohio town has started filing misdemeanor charges of "caus[ing] serious public inconvenience or alarm" against overdose victims, simply for receiving treatment from emergency first-responders.

U.S. Sen. Kelly Ayotte (N.H.) introduced a bill last year to dramatically lower the weight threshold to trigger a five-year mandatory federal prison sentence for fentanyl possession. And in Florida, where lawmakers seem to have exceptionally short memories, a state senator has introduced a bill, with the backing of the Florida Sheriff's Association and the Attorney General's office, that would create harsh new penalties for fentanyl trafficking.

But before legislators pass new laws, they should look at Florida's recent history. Two decades ago, the state enacted strict mandatory-minimum sentences to combat prescription pill abuse. In an effort to shed light on the effect of those laws, Reason pored over the cases of every current inmate in the state admitted for trafficking hydrocodone or oxycodone pills. Those cases, rarely examined at the macro level and never at the individual level, show Florida's war on prescription pain medicine has been an abject failure for 20 years and counting.

A Reason analysis revealed that there are more than 2,000 inmates serving sentences in the state for trafficking oxycodone/hydrocodone. Although Florida legislators passed the laws with the intention of going after large-scale traffickers, 63 percent of those currently serving time for pill trafficking offenses are first-time inmates like Powell. Many, like Powell, were set up by confidential informants who started working for the police after their own arrests.

The mandatory-minimum sentences stripped judges of their discretion, saddled the state with an aging, expensive inmate population with no possibility of early release, and have been woefully inadequate at getting pills off the streets or treating addicts, many of whom are now turning to more powerful opioids like heroin and fentanyl.

Mandatory Minimums Were Supposed to Crack Down on High-Level Dealers

To understand why Cynthia Powell is in prison today, and how Florida settled on its approach to opioid use, you have to return to the mid-1990s, when Florida gained a reputation as ground zero of the opioid epidemic. After OxyContin entered the market in 1996, clinics that dispensed the powerful painkiller began to proliferate throughout south Florida. The state's Interstate 75 corridor became known as the "Oxy Express."

In 1993, the state had abolished mandatory-minimum sentences for all but the highest-level drug trafficking offenses. But in 1999, state lawmakers reinstated its mandatory minimums in an attempt to crack down on what supporters described as high-level dealers.

Former state representative Victor Crist, a sponsor of the bill that reinstated the minimums, said during a committee hearing, "We're talking about the person who's growing three barns full of marijuana, or bringing in a boatload of cocaine. We're talking the major players who are dealing and selling these drugs."

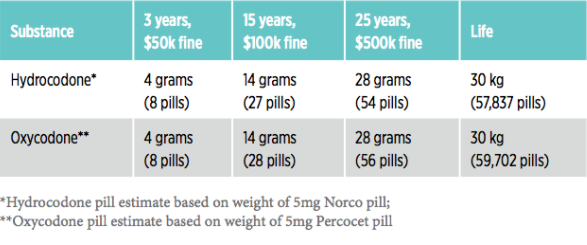

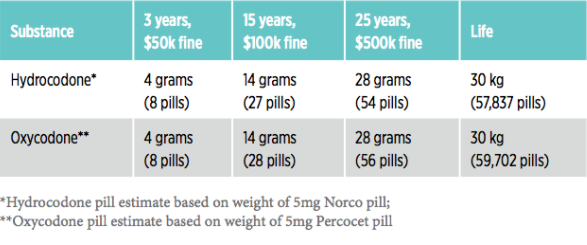

Not when it comes to prescription pain medication. Under the 1999 laws, it took only 4 grams of oxycodone or hydrocodone—roughly eight pills—to trigger a drug trafficking offense that carried a mandatory-minimum term of three years in prison and a $50,000 fine. For a minimum 25 years and $500,000 fine, a person needed to illegally possess or sell 28 grams, or roughly 54 pills, which is less than half of a month's prescription for long-term pain patients like Cynthia Powell, who was prescribed this medication for her diabetic nerve pain.

Not when it comes to prescription pain medication. Under the 1999 laws, it took only 4 grams of oxycodone or hydrocodone—roughly eight pills—to trigger a drug trafficking offense that carried a mandatory-minimum term of three years in prison and a $50,000 fine. For a minimum 25 years and $500,000 fine, a person needed to illegally possess or sell 28 grams, or roughly 54 pills, which is less than half of a month's prescription for long-term pain patients like Cynthia Powell, who was prescribed this medication for her diabetic nerve pain.

The result was not a crackdown on high-level dealers, but a surge in lengthy sentences for low-level offenders like Powell.

There were 2,310 inmates serving sentences in Florida for "trafficking" opioids, the vast majority of which were convicted for hydrocodone and oxycodone, as of December 2016, a Reason analysis found. Prior to 2014, the Florida Department of Corrections (DOC) classified all opioid trafficking convictions with the same offense codes, lumping heroin and morphine with oxycodone and hydrocodone. However, a minority of inmates in 2010—6 percent—were incarcerated for trafficking substances other than oxycodone or hydrocodone, such as heroin, according to a 2012 report by the Florida Legislature's Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability (OPPAGA), and Reason's estimate assumes the inmate population has a similar makeup today.

Of the more than 2,300 Florida inmates serving time for opioid trafficking, the overwhelming majority—63 percent—have never been to prison before. Another 20 percent were previously incarcerated, but for a drug or property crime only. Just 17 percent had been previously incarcerated for a violent offense. Some 435 are over the age of 50, which is the age prisoners are defined as elderly in Florida. Of those, 53 percent have never been to prison before, and 26 percent have been imprisoned previously for a drug or property crime only.

What these numbers show is that, more often than not, Florida prosecutors used opioid trafficking laws to imprison the bottom rung of the drug trade—addicts or people with prescriptions who sold on the side for extra cash—rather than high-level dealers.

More often than not, Florida prosecutors used opioid trafficking laws to imprison the bottom rung of the drug trade.

The 2012 OPPAGA report confirms this. It found that most oxycodone and hydrocodone trafficking convictions were based on illegal possession, sale, or distribution of pills "equivalent to one or two prescriptions." For those convicted and sentenced for trafficking hydrocodone, the report stated, "50 percent were arrested for possessing or selling fewer than 30 pills and 25 percent were arrested for fewer than 15 pills." The median number of pills involved with oxycodone trafficking convictions was 91. That's less than a month's supply for many long-term pain patients, which typically ranges from 90 to 120 pills.

"You're not talking about bringing kilos of heroin in through the Miami shores or something," says Greg Newburn, the state policy director of Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), an advocacy group working to reform Florida's sentencing laws. "You're talking about people who either illegally possess or sell one or two bottles of painkillers and are getting busted for trafficking. It's a tremendous number of very low-level users and low-level dealers, often the same people."

How Cops Use Confidential Informants to Trap Pain Patients

It usually starts like this: Someone gets a call, maybe from a friend or acquaintance, or a guy who knows a guy, who's looking for pills. They'll pay good money, and they need them bad. They might have a sob story.

The confidential informant who set up Cynthia Powell called her repeatedly begging for pills and saying she was sick, according to a statement Powell gave to police after her arrest. "She kept on calling me, kept on calling me.…She told me she had throat problems, had a bad flu, because she sounded real bad," Powell told the police.

"I don't even know nothing about this lady," she continued. "The only way I know about her was because of a friend of mine. I'm on a lot of medication. So I told her no. She said, 'Cynthia, please, please just give me a little pill.'"

Confidential informants have played a major role in the state's opioid busts. Some 62 percent of those arrested for opioid trafficking in the state were set up by an undercover police officer or confidential informant, according to the 2012 OPPAGA report, which looked at a sample of 194 offenders put in prison between 2010 and 2011. In 16 percent of the cases, offenders were arrested after they were searched "during law enforcement contact," 11 percent were arrested after being reported by a pharmacist for possible fraud, and 8 percent were arrested during a traffic stop.

"They'll just badger them and badger them to sell the pills," Newburn says. "And if somebody happens to be down on their luck, or maybe between jobs or whatever, and they've got this bottle of pills…"

Once the transaction happens, and sometimes even before money and pills change hands, as in Powell's case, the police move in. Usually the whole exchange is caught on tape. Since it takes less than a single bottle of pills to successfully prosecute someone as a drug trafficker in Florida, police are just as happy to go after those cases as someone with a trunk full of weed.

The 35 hydrocodone pills Powell offered to sell the undercover officer exceeded the 28-gram threshold, meaning she faced a 25-year mandatory-minimum sentence under Florida law at that time.

"Doing Work"

After her arrest, Powell had three choices. She could plead not guilty, but the state's attorney had her dead to rights, and if she lost she would go down for the full 25-year sentence.

She could take a plea deal offered by the state's attorney for 12 years in prison.

Or she could take a third, tantalizing option offered by the prosecutor. She could become a confidential informant for the police, same as the woman who set her up.

The potential reward was high—but so was the risk. If she succeeded, she might only do a few years in prison, might even get off on probation. But if she failed to provide information leading to an arrest, she would be sentenced to the full 25.

In most trafficking cases, Florida prosecutors ask defendants if they're willing to "do work." The official nomenclature is "providing substantial assistance" to law enforcement.

The "substantial assistance" provision was part of the 1993 bill that repealed mandatory minimums for most trafficking offenses through 1999, but it stuck around after the minimums were reinstated. With both mandatory minimums and substantial assistance agreements on the table, prosecutors have enormous sway over the potential sentence defendants may receive. According to a court filing in one case reviewed by Reason, a defendant said the details of her substantial assistance agreement were as follows: If she helped police with one arrest, she would get two years in prison and 10 on probation. If she gave assistance resulting in three arrests, it would be 10 years of probation and no prison time at all.

But these agreements aren't effective at taking traffickers off the street. Regular dealers have little trouble finding new targets for narcotics police, while small-time users and sellers have to hustle or risk catching the full mandatory-minimum sentence. So a well-connected large-scale dealer stands a significantly better chance of avoiding prison entirely.

Prison population data confirms this phenomenon. Lower-level offenders convicted of a drug trafficking offense serve sentences above the mandatory on average, while inmates convicted of higher-level trafficking offenses tend to serve sentences below the mandatory, according to a 2009 report published by the Florida Senate Committee on Criminal Justice. The reason, the report notes, is that these lower-level offenders have little to no information about other dealers or operatives in a drug trafficking organization, making them unlikely to benefit from a "substantial assistance" reduction.

That dynamic is one of the reasons why Cynthia Powell was sentenced to so much prison time. Against the advice of her attorney, she plead guilty and entered into an agreement to provide substantial assistance to the Sunrise Police Department, working with the same detectives who arrested her.

Powell's daughter, Jackie Sharp, doesn't think her mother even understood what she was signing when she entered into the agreement. Powell dropped out of school in the 11th grade to care for Sharp, and her reading and writing skills are limited. "She was receiving disability, and once they evaluated her she was not even able to sign for her own checks," Sharp says. "Her social security and disability checks came in my name, care of her. Someone else should have been back there with her with the judge and prosecutors. She was incompetent."

One former public defender who asked not to be named says it's "standard operating procedure" for police to target individuals with addiction or dependence issues. "There's not enough large-scale drug dealers to substantiate the funding. I'm not saying they are creating the people, but they're targeting people who are obviously sick."

One former public defender says it's "standard operating procedure" for police to target individuals with addiction or dependence issues.

Complicating matters further, the Sunrise Police Department didn't even have painkillers for Powell to sell. Most individuals who enter into substantial assistance agreements just have to try to sell whatever police departments have on hand.

"She always wanted to sell Lorcets because that's what she was arrested for to begin with…and I told her we didn't have that many Lorcets in our locker," Sunrise Police Detective Ben Hodgers would testify at Powell's sentencing hearing. "However, we did have 10,000 ecstasy pills, 30 kilos of cocaine, 35 pounds of marijuana, whatever she wanted to sell."

Powell's daughter and her public defender say she couldn't set up a deal because she wasn't a drug dealer to begin with.

Powell, in other words, was a 40-year-old woman with no criminal history, who got by on disability and social security checks, who agreed to sell a bottle of pills she had a prescription for, and who probably only had a muddled understanding of the plea agreement she signed, who was now being asked by police to move cocaine and ecstasy. Unsurprisingly, Powell had nothing to show for her work. The state's attorney took her back to court, this time for sentencing.

Mandatory Minimums Give Prosecutors Enormous Power

At Powell's sentencing hearing, prosecutors played dumb.

"I don't know why Ms. Powell has chosen this course. I do not know," Assistant State Attorney John Gallagher stated. "I think I offered her 12 years just flat-out if she pled up straight to the charges. She said she didn't want to do that, she said she really thought she had people that were dealing drugs that she could introduce to the police. And, Judge, I do it every time, OK. I literally try to talk these people out of getting into these harsh sentences. The legislature has deemed this to be such a serious crime that her mandatory-minimum prison sentence is 25 years [at] Florida State Prison and there is a $500,000 fine that accompanies trafficking."

One thing Gallagher neglected to mention was that, as a state's attorney, he had full freedom to decide what charges to bring against Powell. He could have dropped the trafficking charge and prosecuted her solely for possession with intent to distribute. He could have declined to bring the charges in the first place. (Gallagher did not respond to a request for comment.)

Because these offenses carry mandatory-minimum prison terms upon conviction, prosecutors wield enormous power in these cases. The only way an individual can receive a sentence below the mandatory minimum is if the prosecutor negotiates a plea bargain in which lesser charges are agreed to, which means a defendant gives up her right to a jury trial. If a person declines to plead guilty to lesser charges and is subsequently convicted of a trafficking charge, she must be sentenced to the mandatory minimum term, unless she provides substantial assistance. There are no other options for receiving a shorter sentence than what's required by statute.

At her sentencing hearing in 2003, Powell begged for more time to provide assistance to the police, but unlike the prosecutor, the judge had no choice in the matter. "They don't want to work with you any longer," Judge Ana Gardiner explained. "I cannot force them to work any longer, and I don't know of any other legal reason, any legal grounds for me to be able to depart from the minimum mandatory. So whether I feel for you, what I feel about your priors, whether I have a great heart about your daughter, yourself, your situation, you pled open to this court, you pled guilty to these charges, you have not done substantial assistance, now you need to be sentenced."

Apparently still not grasping the severity of the situation, Powell asked the judge if she could be put on house arrest. "I'm sorry, Ms. Powell, there's nothing else I can do," Gardiner responded. "It's not an easy thing, but I can't do anything else."

And with that, Cynthia Powell, a first-time nonviolent offender, was sent to prison for a mandatory minimum of 25 years. She is still there today, housed in a minimum-security facility. Her daughter says the other inmates call her mom.

Sentencing Reform That Failed to Help Those Already In Prison

Powell was unlucky in many ways—among them, the year she was sentenced.

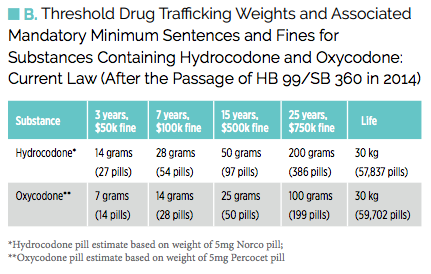

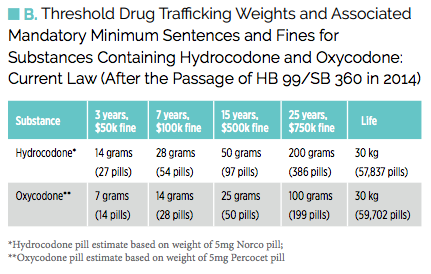

In 2014, the Florida legislature agreed to a modest increase in the weight threshold necessary to trigger these harsh sentences for trafficking oxycodone and hydrocodone. The new rules were put in place in response to concerns, raised by the 2012 OPPAGA report, that the state's harsh sentences were mostly ensnaring low-level offenders.

"We were able to come to a compromise with the prosecutors. Those are always the ones who staunchly oppose any type of significant or meaningful reform when it comes to sentencing," says the bill's sponsor, Florida state Rep. Katie Edwards. "We were looking at it and saying: Does a person who is an addict that has, you know, seven pills in their possession without a prescription—do I want that individual sentenced to three years in state prison where the judge has no discretion? And I think everybody realized: Oh my goodness, this was stupid."

But the thresholds remain quite low. For example, a person can be sentenced to a mandatory minimum of 15 years for illegally possessing or selling roughly 50 oxycodone pills. This is much lower than the median number of pills, 91, convicted offenders possessed or sold at the time of their arrests, according to OPPAGA. And individuals sentenced under the old thresholds—including all of the individuals profiled here—are not eligible for resentencing. That creates a disparity in the system.

"Although the threshold weights for certain painkillers were increased, it provides no accommodation for people who were already serving their sentence," says Deborrah Brodsky, Director of the Florida State University Project on Accountable Justice. "As it stands, under the current legal and constitutional framework, this results in unequal application rendered through the luck of a line on the calendar, rather than an evolved standard that the state of Florida now embraces."

Powell and others like her are stuck serving outdated sentences that the state has subsequently judged too harsh in part because of something known as the "savings clause" of the Florida Constitution, which bars the legislature from making such sentencing changes retroactive. So unless inmates are miraculously granted clemency from the governor—and the current one has done so for just five inmates since taking office in 2011, only three of whom have been released from prison so far—those sentenced under Florida's old opioid trafficking thresholds have no hope of an early release.

The only way to allow inmates to be resentenced after criminal statutes are changed is by repealing or amending the savings clause.

Every 20 years, the Florida Constitutional Revision Commission meets and votes on changes to the constitution—this year being one of them. The commission has been appointed, and the members will meet over the next few months. But there's little hope that this particular reform will even be discussed. "Right now I would guess it's not at the top of their list," says Democratic Florida state Sen. Jeff Clemens.

For inmates sentenced before the 2014 mandatory-minimum revisions, their punishment now seems all the more capricious and arbitrary.

That includes people like James Caruso, who in 2002 was sentenced to a mandatory 25 years in prison for trafficking hydrocodone, plus a $500,000 fine. "Under the new law I would be subject to a seven-year prison term and $100,000 fine," he writes in a letter to Reason. "I have served more than twice that and owe five-times the fine. A person in Florida could literally do the exact same thing today that I did in 2002 and still get out of prison before me…And if you believe the police reports, I was just a lookout."

And it includes Cynthia Powell. If she were convicted under the new thresholds, she would've received a 15-year mandatory minimum prison sentence, and would have already been released. Instead, she has over 6 more years to go before she's projected to be released, by which time she'll be 61 years old.

"When you look at the fact that we've changed the law, and now there are people serving 15- and 25-year sentences who would have only served three- or seven-year sentences—it's a crime to keep those people locked up just because some anachronistic constitutional provision ties the hands of the legislature," says FAMM's Newburn. "That provision was passed in 1885."

The Victims of Florida's Mandatory Minimums

Cases like Powell's are common in Florida's prison system, where state drug laws have ended up ensnaring the sick, the elderly, and the desperate. The particulars vary, but the essence of the stories—which invariably involve some combination of small amounts of drugs, mandatory minimums, mental health issues, and confidential informants—are fundamentally the same.

Mary Nowling, who just celebrated her 65th birthday from prison, was homeless, on disability, and staying at a male friend's house when, according to trial transcripts, he pressured her into selling her Oxycodone pills to a confidential informant so Nowling could pay the friend rent he suddenly said she owed. She said the pills were prescribed to her after back surgery for a degenerative back bone loss, according to court records. She was convicted of drug trafficking by a jury and received a mandatory-minimum 15 years in prison. Her projected release date is in 2022; she'll be 70 years old. Under the 2014 thresholds, she would've received a mandatory minimum of seven years and would be a free woman this year.

"It's a crime to keep those people locked up just because some anachronistic constitutional provision ties the hands of the legislature."

Inmate William Forrester was sentenced in 2009 to a mandatory-minimum 15 years in prison for trafficking oxycodone and obtaining a substance by fraud. In his case, a pharmacist filled a prescription for 120 oxycodone pills. When he came back to fill a second prescription, the pharmacist called the doctor to verify. When the doctor said he did not authorize either prescription, Forrester was arrested for trafficking the meds he had obtained the month before, as well as for forging the current prescription. Despite the trafficking charge, there was no evidence he intended to sell the pills.

At Forrester's sentencing hearing, the judge had no choice but to sentence him to the mandatory-minimum term. He told Forrester that if drug rehabilitation "was an option, then certainly we would talk about it. But my hands are tied by the law, and I have to sentence you to 15 years, and there's no ifs, ands, or buts about it. The legislature has said for this particular crime, we prescribe a fixed sentence. It doesn't give me A, B or C. I've only got A."

"I had no idea such long sentencing laws for not selling pills were even in existence," Forrester writes in a letter. "I thought 'drug trafficking' laws were for people found guilty of huge quantities of drugs such as moving it in boats, planes, trunks of cars, etc." Forrester, now 60, suffers from multiple health issues and had a lung removed due to cancer before his arrest. If he survives until his projected release date in 2021, he will be just shy of 65 years old. Had he been sentenced under the 2014 thresholds, he would've gotten out last year.

Or take the case of Todd Hannigan, now 49, a troubled man who in 2009 decided to take his mother's bottle of prescription Vicodin and a six-pack of beer, to find a park bench to sit on, and to commit suicide by overdose. Police arrested him before he could complete the act, but instead of mental health treatment or drug rehab, Hannigan was sentenced to 15 years in prison--the legal minimum--for trafficking hydrocodone, despite having no intention to sell the pills.

As in Forrester's case, Hannigan's judge voiced frustration as he handed down the mandatory sentence. "I do think this is an inappropriate sentence under these circumstances," the judge said. "The legislature has, in its infinite wisdom, decided to transfer a significant amount of what was once judicial discretion to the prosecutorial arm of this state. There's nothing I can do about that. There's nothing I can do about that at all....Under this set of circumstances, this court does nothing more than perform an administerial function. I sign the papers. I'm on autopilot."

A judge expressed similar sentiments in 2010 to Nancy Ortiz, a then-49-year-old woman with a documented history of mental health issues. She was arrested after she sold some of her prescription pain medication to an undercover officer.

"Ms. Ortiz, I'm very sorry that you got caught up in what you got caught up in," the judge said as he sentenced her to a mandatory 25 years. "And I take no pleasure in imposing that sentence. Now as I said, I think you should be punished for your crimes. I think that the sentence that the legislature requires for this offense is in some cases not proportionate to the criminal activity, and I think this is one of those cases, but I don't have any discretion in the matter." Ortiz is now 57 years old. The earliest she can be released is in 2032, when she will be 72.

Florida lawmakers "think they're getting Pablo Escobar off the streets of Tampa or Miami, and they wind up getting Suzie Schoolteacher going up the road for a year and a day in Florida state prison," says David Knox, a former prosecutor and now a Tampa defense attorney. "I don't know if people care to change it, but I can tell you a lot of the state attorneys are bothered by it."

"It's one thing where you have a drug dealer—you know who they are, they've got the cocaine press in their house, and people are coming and going at all hours of the day," Knox continues. "They knew what they were getting into when they started dealing drugs. It's another when you've got a person who's pulled over and their car is searched. You got some pills here? You have a prescription? No? Oh, well, tough. You're arrested for felony trafficking of oxycodone, you've got a $10,000 bond, and you're looking at a mandatory three years in prison."

A Failed Policy

Florida's mandatory minimums were intended to stop high-level traffickers and reduce opioid abuse in the state, but according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, prescription drug overdose deaths in Florida increased more than 80 percent between 2003 and 2009. At the same time, prison admissions for trafficking prescription pills quadrupled between 2005 and 2011. Yet in 2010, after years of prosecuting offenders like those described in this story, Florida still had 93 of the top 100 oxycodone-dispensing doctors in the U.S.

Overdose rates and prison admissions for oxycodone and hydrocodone began falling in Florida in 2011, following a crackdown on so-called "pill mill" doctors and clinics. But patients suffering from chronic pain now have a harder time getting legal relief—and overdose deaths for cheaper and more readily available drugs like heroin and fentanyl have skyrocketed. Heroin-caused deaths in the state rose 1,400 percent, from 48 in 2010 to 733 in 2015, according to reports by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Over the same period, fentanyl-caused deaths rose by 433 percent. The crackdown on prescriptions has meant that users simply turn to other, more dangerous drugs.

Meanwhile, those unlucky enough to be caught before 2014 continue to lose years of their lives in prison. In the end, the state has been saddled with an aging, expensive prison population, while families are left without loved ones and inmates like Cynthia Powell, who turns 55 next month, are left with no hope of getting out before the best years of their lives are gone. It's hard to conclude the policy has been anything but a total failure.

Powell has missed a lot on the outside since 2003. "Even when I had my kidney transplant, my mom couldn't even be there for me because she was incarcerated," Sharp, her daughter, says. "I had to beg the warden to talk to her before I went in for surgery."

When Powell's father died, Sharp says the prison wouldn't give her furlough to attend the funeral unless the family would pay for four or five guards to watch her. She would have been shackled in any case, but the family couldn't afford it. Powell missed the funeral.

"She's been in prison for 16 years now," Sharp says of her mother. "That's just crazy." Sharp says her mother isn't doing well in prison. "When I go to see her, I tell her to keep praying, and I'll keep praying, and that's all we can do."

Not when it comes to prescription pain medication. Under the 1999 laws, it took only 4 grams of oxycodone or hydrocodone—roughly eight pills—to trigger a drug trafficking offense that carried a mandatory-minimum term of three years in prison and a $50,000 fine. For a minimum 25 years and $500,000 fine, a person needed to illegally possess or sell 28 grams, or roughly 54 pills, which is less than half of a month's prescription for long-term pain patients like Cynthia Powell, who was prescribed this medication for her diabetic nerve pain.

Not when it comes to prescription pain medication. Under the 1999 laws, it took only 4 grams of oxycodone or hydrocodone—roughly eight pills—to trigger a drug trafficking offense that carried a mandatory-minimum term of three years in prison and a $50,000 fine. For a minimum 25 years and $500,000 fine, a person needed to illegally possess or sell 28 grams, or roughly 54 pills, which is less than half of a month's prescription for long-term pain patients like Cynthia Powell, who was prescribed this medication for her diabetic nerve pain.

Samsung expects to post stellar earnings for the first quarter of 2017 despite its head honcho's scandal in Korea and the lack of a new flagship phone for the period. The company believes its consolidated operating profit will reach approximately 9.9...

Samsung expects to post stellar earnings for the first quarter of 2017 despite its head honcho's scandal in Korea and the lack of a new flagship phone for the period. The company believes its consolidated operating profit will reach approximately 9.9...

The Divergent Blade, which was on display at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, weighs half as much as a Mini Cooper but accelerates to 60 mph faster than a Porsche 911 Turbo S. It can be assembled in under half an hour from 3D-printed metal parts—and building one generates just a third of the emissions that come from producing an electric vehicle, according to the manufacturers.

The Divergent Blade, which was on display at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, weighs half as much as a Mini Cooper but accelerates to 60 mph faster than a Porsche 911 Turbo S. It can be assembled in under half an hour from 3D-printed metal parts—and building one generates just a third of the emissions that come from producing an electric vehicle, according to the manufacturers.