0. Introduction

I grew up in the 90s, which meant watching movies about plucky children fighting Pollution Demons. Sometimes teachers would show them to us in class. None of us found that strange. We knew that when we grew up, this would be our fight: to take on the loggers and whalers and seal-clubbers who were destroying our planet and save the Earth for the next generation.

What happened to that? I don’t mean the Pollution Demons: they’re still around, I think one of them runs Trump’s EPA now. What happened to everything else? To those teachers, those movies, that whole worldview?

Save The Whales. Save The Rainforest. Save Endangered Species. Save The Earth. Stop Slash-And-Burn. Stop Acid Rain. Earth Day Every Day. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. Twenty-five years ago, each of those would invoke a whole acrimonious debate; to some, a battle-cry; to others, a sign of a dangerous fanaticism that would destroy the economy. Today they sound about as relevant as “Fifty-four forty or fight” and “Remember the Maine”. Old slogans, emptied of their punch and fit only for bloodless historical study.

If you went back in time, turned off our Pollution Demon movie, and asked us to predict what would come of the environment twenty-five years, later, in 2018, I think we would imagine one of two scenarios. In the first, the world had become a renewable ecotopia where every child was taught to live in harmony with nature. In the second, we had failed in our struggle, the skies were grey, the rivers were brown, wild animals were a distant memory – but at least a few plucky children would still be telling us it wasn’t too late, that we could start the tough job of cleaning up after ourselves and changing paths to that other option.

The idea that things wouldn’t really change – that the environment would neither move noticeably forward or noticeably backwards – but that everyone would stop talking about environmentalism – that you could go years without hearing the words “endangered species” – that nobody would even know whether the rainforests were expanding or contracting – wouldn’t even be on the radar. It would sound like some kind of weird bizarro-world.

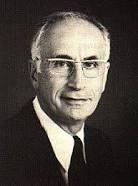

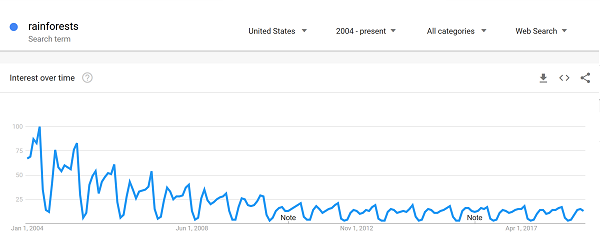

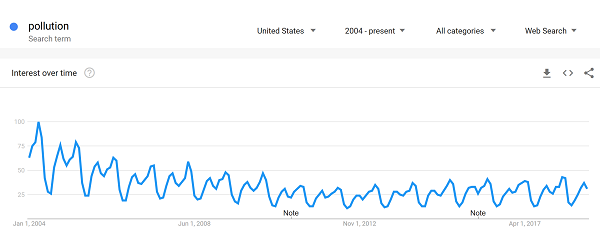

Just to prove I’m not imagining all this:

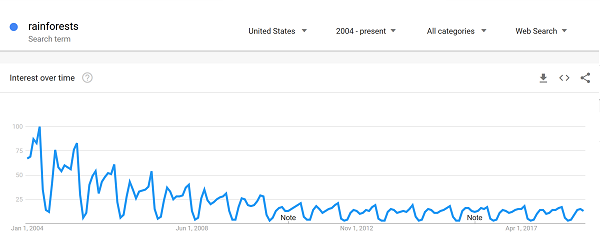

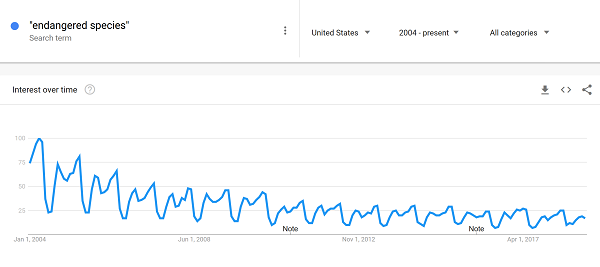

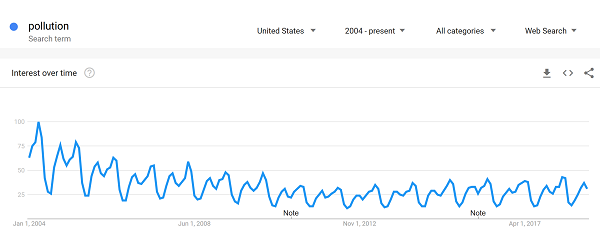

This is the volume of Google searches for “rainforests” over time. It goes up each year when school starts, and crashes again for summer vacation. But on average, there are only about 18% as many rainforest-related searches today as in 2004.

“Endangered species”, 25%

“Pollution”, 43%

And these are just since Google started tracking searches in 2004. The decline of 90s environmentalism must be even bigger.

So what happened?

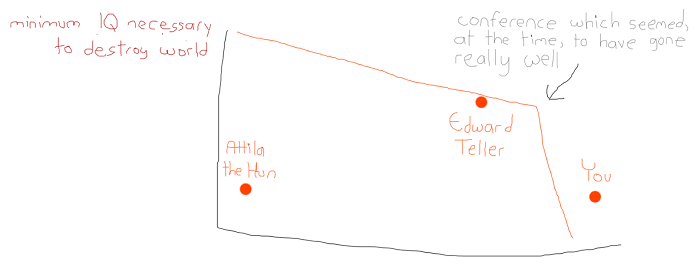

Every so often you’ll hear someone mutter darkly “You never hear about the ozone hole these days, guess that was a big nothingburger.” This summons a horde of environmentalists competing to point out that you never hear about the ozone hole these days because environmentalists successfully fixed it. There was a big conference in 1989 where all the nations of the world met together and agreed to stop using ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons, and the ozone hole is recovering according to schedule. When people use the ozone hole as an argument against alarmism, environmentalism is a victim of its own success.

So what about these other issues that have since fizzled out? Did environmentalists solve them? Did they never exist in the first place? Or are they still as bad as ever, and we’ve just stopped caring?

1. Air And Water Pollution

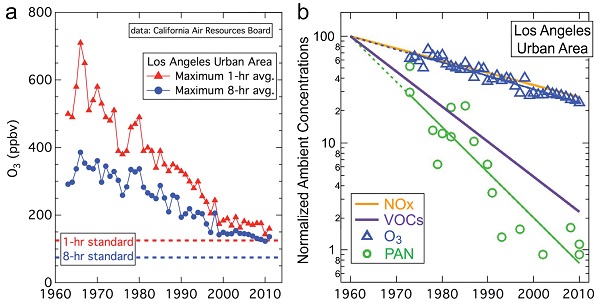

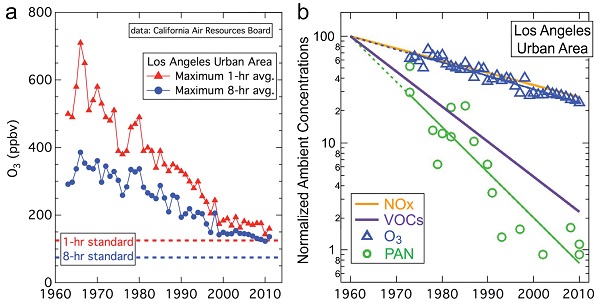

Have you seen what Chinese cities look like on a smoggy day? Trick question: neither have the Chinese. The US used to be like that. I grew up near Los Angeles during the 1990s. My mother tells the story of a time when I was very young and my grandparents came to visit from the Midwest. “It reminds us of home,” they said, “it’s so flat.” “We’re surrounded by mountains”, my mother told them. We were. You couldn’t see any of them.

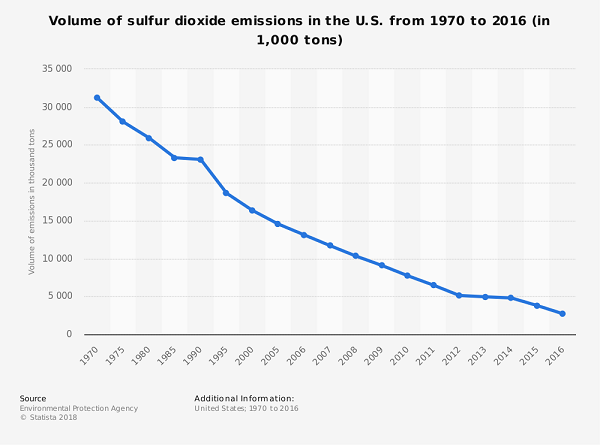

Environmentalists crusaded against this. Here are the results:

A lot of the credit goes to the Clean Air Act, passed in 1963 and tightened in 1990. Along with its more visible (pun intended) effects, scientists suspect it has prevented about 200,000 deaths from lung disease and a host of other cases of asthma, bronchitis, and even heart attacks.

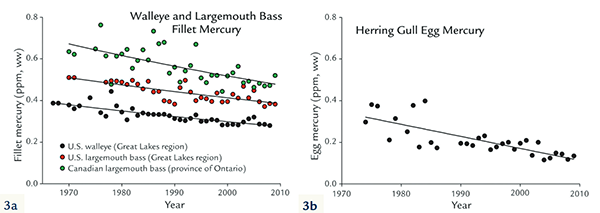

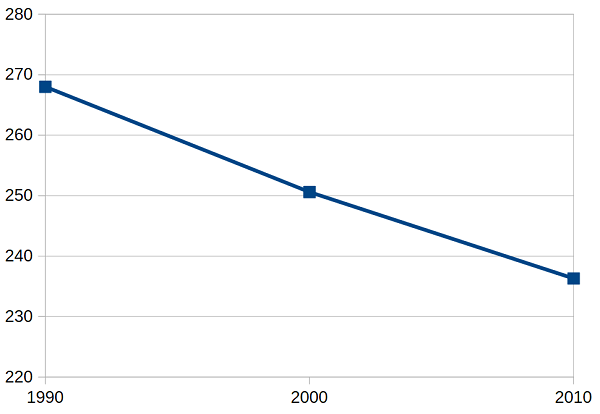

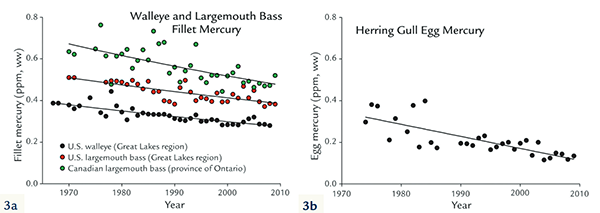

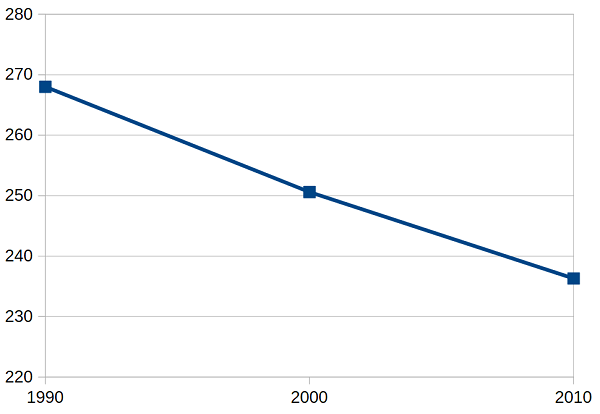

It’s hard to find great data on water because there are so many different kinds of water and so many different ways it can be polluted. But just to choose a random very bad thing, here’s mercury levels in Great Lakes fish:

I don’t know of anyone claiming this is anything other than a response to stricter environmental laws.

As a result of these victories, people are no longer as concerned about air and water pollution. From Gallup:

This seems like a clear case of good work.

Verdict: Environmental movement successfully solved this problem.

2. Acid Rain

Acid rain is a combination of rain and pollution which gets very acidic and destroys plants and structures. It was a staple of very early 90s environmentalism, and understandably so: the prospect of acid falling from the sky and dissolving everything is very attention-grabbing. I remember the discourse focusing on statues; George Washington’s marble face slowly melting under sizzling raindrops makes a heck of an image.

I am not the first person to notice that Washington’s face remains mercifully unmelted. In 2009, Slate asked Whatever Happened To Acid Rain?. EPA Blog, 2010: Whatever Happened To Acid Rain?. 2012, Mental Floss: What Ever Happened To Acid Rain? By 2018 the Internet had advanced, so here’s the Whatever Happened To Acid Rain Podcast. Even the Encyclopedia Britannica, itself a good candidate for a “Whatever Happened To…” piece, has a What Happened To Acid Rain article.

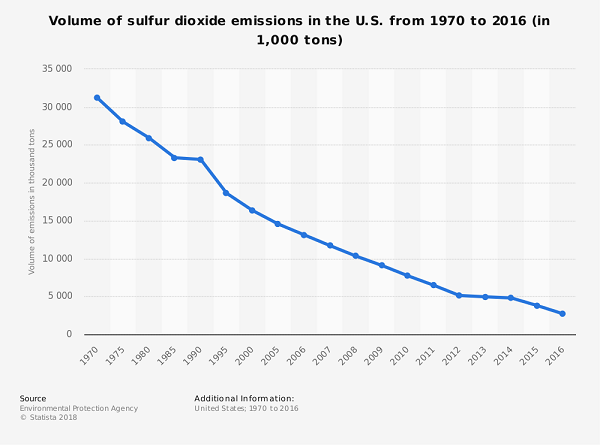

Most of these sources say environmentalists solved acid rain by cutting down on emission of sulfur dioxide, the main offending chemical. A Bush I era cap-and-trade policy gets a lot of the credit in the US, but it looks like it was a broader effort than that:

There’s less clear data on rain acidity, but all my sources agree it has modestly declined in the US, thought it is still “between 2.5 and eight times more acidic than it should be”. Lakes and rivers are slowly recovering. On the other hand, in newly-industrializing countries like China and India, rain is becoming more acidic and they’re going through some of the same issues we were in the 80s.

This picture is slightly complicated by some people who claim acid rain was always exaggerated and “we solved it” is a convenient retreat from acknowledging this (for what it’s worth, these people tend to be global warming skeptics too). Most of them point to the 1990 National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program, a giant government investigation into the acid rain problem. I found a 1990 New York Times article on the report here:

A comprehensive Federal report that was supposed to resolve the issue of how much damage is caused to forests by acid rain has come under criticism from some distinguished scientists who are reviewing it.

The critics said that the report gave an incorrect impression that air pollution was not causing any large-scale problems for forest ecosystems. They also said that the report, still in draft form, ignored a number of studies suggesting serious air pollution problems.

But other experts contend that the general conclusion of the report is essentially right. The report concluded that with the exception of damage to red spruce at high elevations in the East, forests in the United States are not suffering serious damage from acid rain […]

The report now being reviewed is the final draft, completed at a cost of nearly $500 million. It examines the effects of other pollutants, like ozone, as well as acid deposits, and it concludes that air pollution causes far less environmental damage than has been feared.

An interim report issued by the study group in 1987, before Dr. Mahoney became director, was sharply criticized by many scientists. They contended that it tailored research findings into conclusions that matched the political goals of the Reagan Administration, which opposed new controls on air pollution. No such criticism has been leveled at the 28-volume final draft, which has been generally praised as a sound scientific document.

There is, however, some unhappiness among scientists with the volume dealing with forest health and productivity in the United States and Canada.

Dr. Ellis B. Cowling, associate for research at North Carolina State University’s College of Forest Resources, said in a telephone interview: ”The tone is that we don’t have a problem except in southern California, and with red spruce at high altitudes. That is not a fair statement of the state of scientific knowledge.” He added, ”Perhaps the authors were a bit too hasty in reaching conclusions.”

Dr. Cowling, who is highly regarded by colleagues as a conservative, solid scientist, wrote a memorandum to the authors of the forest health volume. He offered a series of suggestions for changing the wording of conclusions in ways that he said would reflect the state of science more accurately.

The first of those would change a finding that stated, ”The vast majority of forests in the United States and Canada are not affected by decline.” To be more consistent with the data, Dr. Cowling said, the conclusion should read: ”Most forests in the United States do not show unusual visible symptoms of stress, marked decreases in the rate of growth or significant increases in mortality.”

Just because symptoms of forest decline are not currently visible, Dr. Cowling argued, does not rule out the possibility that they are under way.

This article also provides a summary of contemporaneous responses to NAPAP, which quotes study director James Mahoney’s summary of his own report: “The sky is not falling, but there is a problem that needs addressing.”

I cannot find anyone really challenging the NAPAP report nowadays, so I provisionally accept that the damage from acid rain, while real, was exaggerated at the time.

There’s a related debate about how much the lakes and streams affected have recovered. Some lakes and streams are naturally acidic; there is some debate over what percent of lake/stream acidity is natural vs. acid-rain-related. In recent years this debate has focused on whether lakes/streams have recovered after the SO2 decline; if they haven’t, this might suggest their problems were never human-activity-related in the first place.

Global warming skeptic blog Watt’s Up With That claims they haven’t:

Possibly the greatest evidence against harmful effects of acid rain is the fact that acidic lakes have not “recovered” after most sulfur and nitrogen pollution was removed from the atmosphere. The 2011 NAPAP report to Congress stated that SO2 and NO2 emissions were down, that airborne concentrations were down, and that acid deposition from rainfall was down, but could not report that lake acidity was significantly reduced. The report states, “Scientists have observed delays in ecosystem recovery in the eastern United States despite decreases in emissions and deposition over the last 30 years.” In other words, the pollution was mostly eliminated, but the lakes are still acidic.

You can find the report here. Like all long government reports, the details are ten zillion different trends in different directions that don’t form a cohesive narrative, and the executive summary is “things are good in all the ways that suggest we deserve more money, but bad in all the ways that suggest we need more money”, It is complicated enough that you shouldn’t trust my excerpting, but at least to me the relevant excerpts seem to be:

Levels of acid neutralizing capacity (ANC), an indicator of the ability of a waterbody to neutralize acid deposition, have shown improvement from 1990 to 2008 at many lake and stream long-term monitoring sites in the eastern United States, including New England and the Adirondack Mountains. Many lakes and streams still have acidic conditions harmful to their biota even though the increases in ANC indicate that some recovery from acidification is occurring in sensitive aquatic ecosystems

And:

Despite the environmental improvements reported here, research over the past few years indicates that recovery from the effects of acidification is not likely for many sensitive areas without additional decreases in acid deposition. Many published articles, as well as the modeling presented in this report, show that the SO2 and NOx emission reductions achieved under Title IV from power plants are not recognized as insufficient to achieve full recovery or to prevent further acidification in some regions.

So Watts seems to be mostly wrong when they say lakes are not recovering, but mostly right when they say ecosystems are not recovering. But NAPAP has some explanations for why ecosystems are not recovering: first, if you poison a lake and kill everything, then even if you remove the poison later everything is still dead. Second, there are complicated natural cycles that gradually wash old deposited land-based pollution into lakes, and it will be a long time before all the pollution deposited on land gets fully washed away. Third, maybe we haven’t fought acid rain hard enough.

I think a lot of the epistemic work here is going to get done by people’s respective stereotypes about the trustworthiness of global warming denialists vs. big government agencies whose budget depends on there being a problem. But my impression is that Watts’ claim that poor recovery suggests acid rain was never a problem don’t hold up very well.

In any case, it’s undeniable that rain has become a lot less acid lately, and likely that this has at least modest positive effects on some ecosystems as well as on the built environment. Anti-Confederate protesters have replaced acid rain as the number one threat to our statues. Our precious, precious statues. Someday they will be safe.

Verdict: A little of everything: partly solved, partly alarmism, partly still going on.

3. The Rainforests

Maybe the most typical image of 90s environmentalism is men in bulldozers clear-cutting a rainforest, while tapirs and tree sloths gently weep.

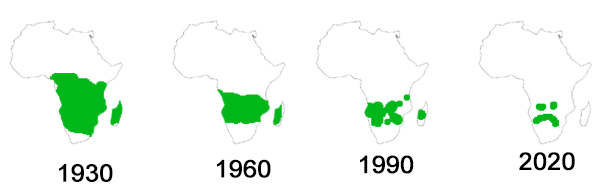

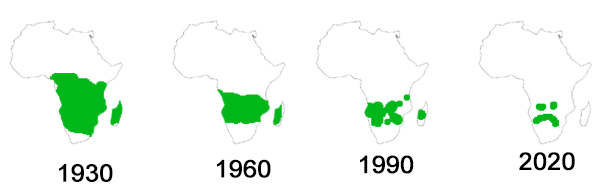

Or maybe it was the declining-rainforest-coverage-over-time-maps. I feel like about one in every three posters I saw as a child looked something like this:

This is a fake example. Please stop asking me where I am getting the data from.

I thought surely nothing could be easier than digging up a few of them and seeing whether their 2020 predictions were right. But I can’t find them anywhere. According to the Internet, there is no such thing as 90s-era maps showing declining rainforest coverage over time. Can anyone else locate these?

Anyway:

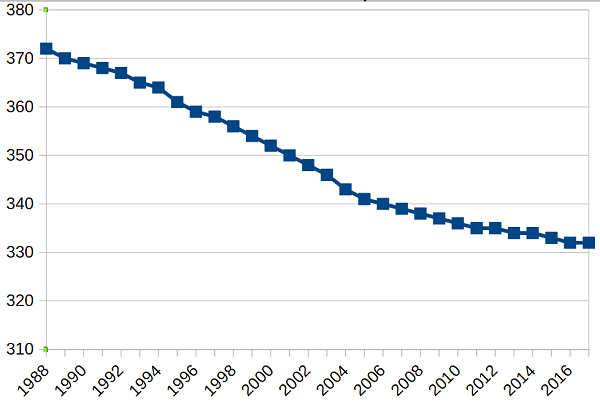

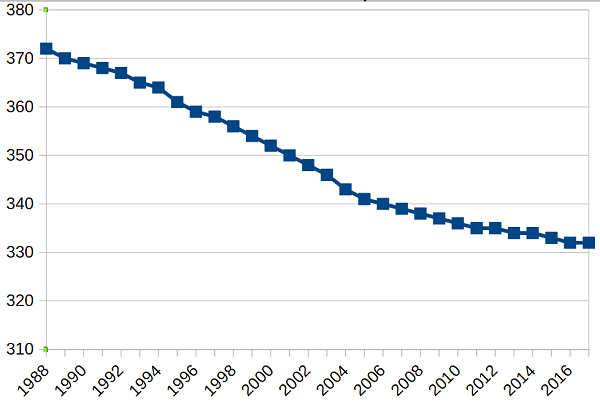

Here’s a graph of the size of the Amazon over time (source, note that the y-axis is not at zero). At 90s levels of deforestation, the Amazon would have disappeared in about 200 years. At current levels, it will disappear in about 400 years.

Here’s the Congo (somewhat dubious source, same caveat). At the rates shown here it will be gone in 250 years – but it seems to have slowed after the period on the graph.

And here’s Southeast Asia (source, same caveat). At this rate, the southeast Asian forest will be gone in 150 years, though some new papers are suggesting we may be underestimating the deforestation rate.

Overall it looks like deforestation may have decreased modestly in the Amazon (and possibly the Congo) since the 1990s. It has not decreased significantly in Southeast Asia, and whatever decreases have happened are not relevant to the scale of the problem.

The only good news is that all those “rainforests will be gone by 2050” posters were just wrong; there is more rainforest than that. But not that much more.

Verdict: The problem still exists, and we are just ignoring it now.

4. Endangered Species

So just find how many species go extinct each year, and whether it’s a lot or a little, and then we’ll know what’s going on with this, right? Ha ha, as if.

On the one hand, the UN Environment Programme says that “150-200 species of plant, insect, bird and mammal become extinct every 24 hours.”

On the other, nobody can name more than a single-digit number of species that go extinct in any given year. The 2017 list includes five: a bat, a cat, a flatworm, a lizard, and a snail. This matches longer-term surveys: Ceballos et al (2018) find that about 477 vertebrate species have gone extinct since 1900 – again, about five per year. And a recent survey found only four to eight bird species had disappeared since the turn of the century.

I have no idea where the 150-200 number per day comes from, and neither does anyone else. The closest I can find to a justification is this WWF page, which reminds us that if there are 100 million animals species, and “the extinction rate is just 0.01% per year”, then at least 10,000 species go extinct every year (=200-300/day) – but all of these numbers are completely made up.

One could try to justify these estimates with something like “assume only one in a thousand species has been discovered and is monitored well enough to detect its extinction, so if we detect five extinctions per year then five thousand must be happening” – but I’ve never heard anyone actually say this. Also, with apologies to all the undiscovered species, if they’re so tiny and uncommon as to never get discovered, it doesn’t seem like their extinction is going to change very much.

Five known species going extinct per year may sound like a lot if you’re thinking it’s something like “rhinos, pandas, whales, spotted owls, and leopards”. But realistically there are 385 species of shrews. We could spend our entire yearly extinction budget on shrews for the next sixty years and still have more than enough kinds of shrews left to satisfy basically anybody.

I’m trying to think what the best counterargument to this would be – the best case that we really do need to consider species extinction a dire concern.

Maybe this is too vertebrate-centric, and there are lots of insects and plants and such going extinct all the time? But this List Of Recently Extinct Insects suggests that of about 6000 known insect species, only 50-100 have gone extinct in the past century. And one of those was this giant earwig which I really think the world is better without.

Or maybe we can’t directly predict the future from the past. Imagine 1000 square miles of rainforest with a homogenous distribution of species. Clear-cut 50% of the rainforest, and no extinctions. Clear-cut 90% of the rainforest, still no extinctions. Clear-cut 99%, maybe a few extinctions if you’re unlucky. Then clear-cut the last remaining 1% and everything dies. It seems like something like that might be happening – see for example this report that global animal populations have declined 58% over the past forty years.

But any concept of endangered species that focuses on “many well-known species will be gone soon” doesn’t seem consistent with the evidence.

Verdict: Partly alarmism, partly still going on.

5. More And More Trash Piling Up Until The Whole World Is Just A Giant Mountain Of Trash

Wait, what? Was this really a concern? Did I really spend my primary school years being told that if I didn’t vigilantly recycle everything, one day I would be submerged beneath a sea of trash, breathing by means of a trash snorkel? Am I hallucinating all of this?

As usual, it turns out to be the Mafia’s fault. In the 1980s, mob boss Salvatore Avellino took over New York City’s landfill industry, and in a shocking development which nobody could have predicted, was corrupt. New York City soon ran out of landfill space. Somehow all of its excess trash ended up on a barge called the MOBRO-4000, because the Eighties, and this barge apparently sailed up and down the east coast of North America searching for a place to deposit its trash. In its many exciting adventures it reached the coast of Belize, got involved in a confrontation with the Mexican Navy, and finally went back to New York, where at some point landfill space was found and the crisis was over.

But a giant boat full of trash made a really memorable image, and it got nationwide news coverage, and environmentalists took advantage of this to tell everyone there was no more landfill space anywhere in the world and we all had to recycle right now. According to Wikipedia:

At the time, the Mobro 4000 incident was widely cited by environmentalists and the media as emblematic of the solid-waste disposal crisis in the United States due to a shortage of landfill space: almost 3,000 municipal landfills had closed between 1982 and 1987. It triggered much national public discussion about waste disposal, and may have been a factor in increased recycling rates in the late 1980s and after. It was this that caused it to be included in an episode of Penn & Teller: Bullshit! (season 2, episode 5) in which they debunk many recycling myths.

I’m even absolutely right in remembering primary school lessons centered around garbage covering the Earth and killing everybody. Here’s a New York Times article from 1996 – ie after the crisis had a little bit of time to fade – lightly mocking the new curricula that followed in its wake:

After the litter hunt in Ms. Aponte’s science classroom, it was time for a guest lecturer on garbage. A fifth-grade class was brought in to hear Joanne Dittersdorf, the director of environmental education for the Environmental Action Coalition, a nonprofit group based in New York. Her slide show began with a 19th-century photograph of a street in New York strewn with garbage.

“Why can’t we keep throwing out garbage that way?” Dittersdorf asked.

“It’ll keep piling up and we won’t have any place to put it.”

“The earth would be called the Trash Can.”

“The garbage will soon, like, take over the whole world and, like, kill everybody.”

Dittersdorf asked the children to examine their lives. “Does anyone here ever have takeout food?” A few students confessed, and Dittersdorf gently scolded them. “A lot of garbage there.”

She showed a slide illustrating New Yorkers’ total annual production of garbage: a pile big enough to fill 15 city blocks to a height of 20 stories. ‘There are a lot of landfills in New York City,” Dittersdorf said, “but we’ve run out of space.”

From the same beginning-of-the-backlash period we also get this 1995 Foundation for Economic Education piece, Are We Burying Ourselves In Garbage?:

A popular idea in public discourse today is that the United States produces an overwhelming amount of trash–so much that our landfills will not be able to handle the quantity. The most eloquent symbol of this viewpoint was the “garbage barge,” which in the late 1980s left Long Island and could not find a port or country willing to accept its 3.168 tons of refuse. [But] the actual data (such as they are) on the amount of municipal solid waste produced present us with more questions than answers.

This article also deserves note for hitting on a brilliant solution:

The crisis mentality has distorted judgment of waste disposal. The notion that modern America is especially wasteful is demonstrably wrong, both in terms of the last decades as well as the last 100 years. The idea that our landfills are literally “running out” is even less credible. If in the next century major portions of the United States really need to export their refuse to other states, a “gold mine” for refuse burial does exist: South Dakota. This state is geologically, economically, and politically almost ideal for massive municipal solid waste management.

None of this is a joke. This is how your parents did Discourse, people.

But it turns out capitalism works: if there’s a shortage of landfills, that incentivizes people to create new landfills. Also, the world is very large and it is hard to cover a significant portion of it in trash. There was a brief blip as cities figured out how to pay for more waste disposal, and then nobody ever worried about the problem again. Recycling remained inefficient and of dubious benefit, and never really caught on.

There is still an international problem as Third World countries struggle with infrastructure issues around trash disposal. You still see occasional articles like Huffington Post’s People Are Living In Landfills As The World Drowns In Its Own Trash, from earlier this year. But I think in general nobody in the First World still considers this a major problem.

Well, almost nobody:

Verdict: Alarmist. So, so, alarmist.

6. Peak Resource

Is the earth’s ballooning human population using up resources at an unsustainable rate?

Technically the answer must be “yes”, since by definition nonrenewable resources have to run out at some point. But when? Long after we have escaped to space and gotten access to shiny new resources? Or soon enough that we have to worry about it?

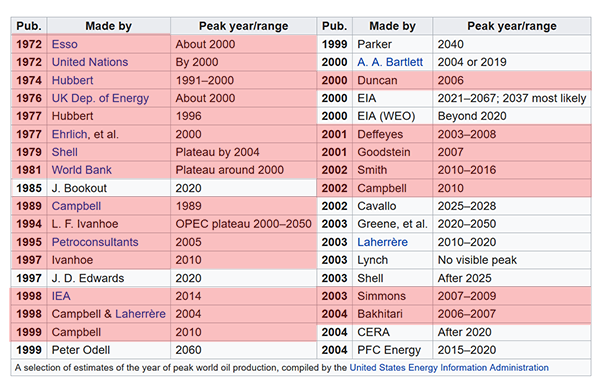

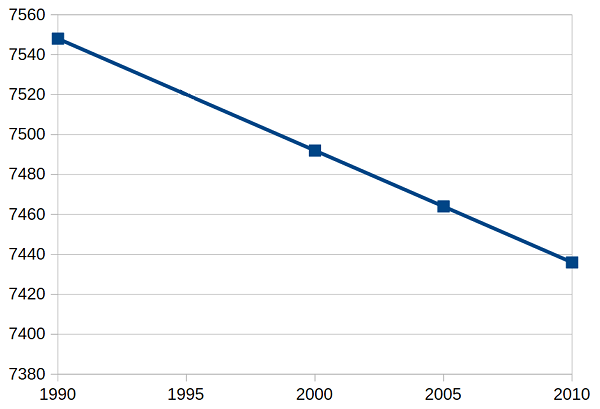

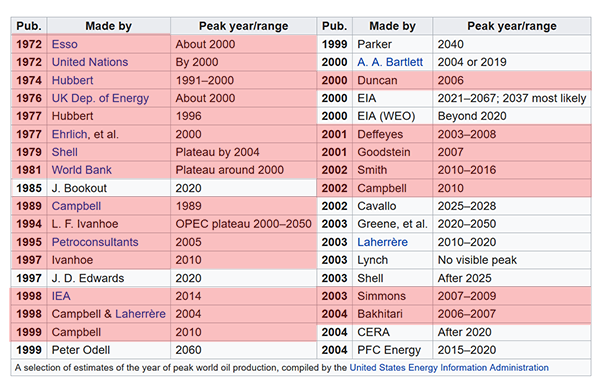

A big part of 90s environmentalism involved worrying that it was the latter. A particular concern was “peak oil”, the point at which we had exhausted so much of the world’s oil that production rates declined every year thereafter and oil started becoming gradually rarer and more expensive. Wikipedia has a helpful table of people’s peak oil predictions. I’ve highlighted the ones that have already passed in red.

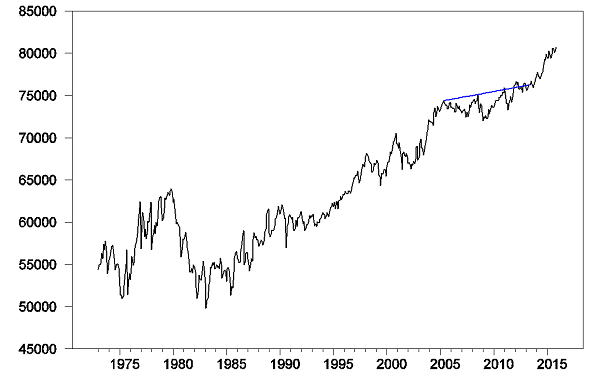

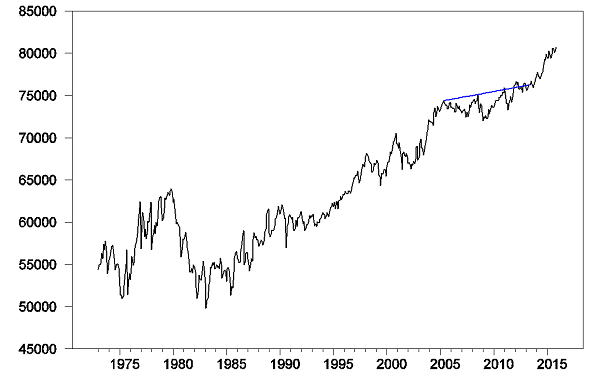

Almost everyone working before 2000 thought we would have reached peak oil by now. But here’s world oil production over time:

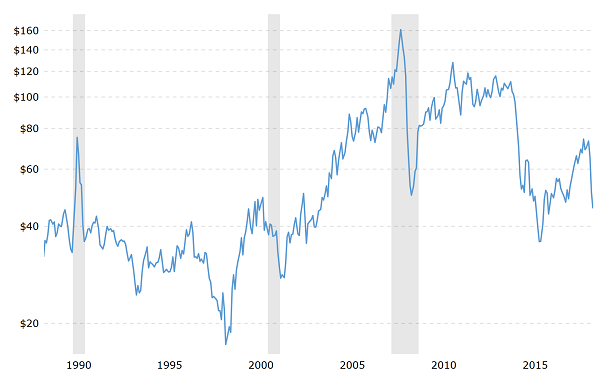

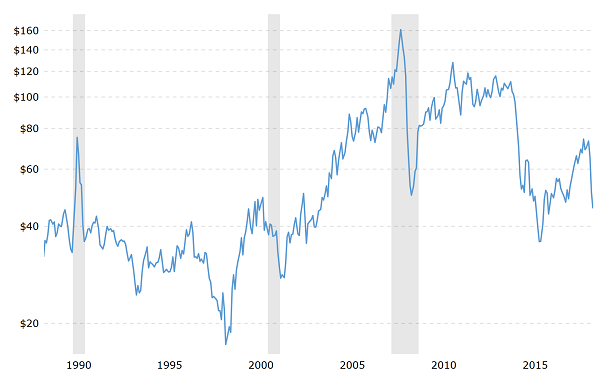

And the price of oil:

What happened? People discovered fracking and other paradigm-shifting techniques to extract oil from shale, which opened up vast new previously-inaccessible oil fields. The peak oil predictors might call this unfair – they calculated correctly given the technology they knew about – but the whole argument of the people who say we don’t have to worry about peak resource (sometimes called “cornucopians”) is that technology will advance fast enough to satisfy our resource needs. In this case they were right.

What about non-oil resources?

In 1980, leading environmental scientist and peak-resource proponent Paul Ehrlich made a bet with cornucopian economist Julian Simon about how resource prices would change over the next decade. The Simon-Ehrlich Wager has become a famous example of futurology done right – two people with different theories implying different predictions coming together, agreeing on exactly what each of their theories implied, and then publicly committing to put them to the test. According to Reb Wiki:

Simon challenged Ehrlich to choose any raw material he wanted and a date more than a year away, and he would wager on the inflation-adjusted prices decreasing as opposed to increasing. Ehrlich chose copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten. The bet was formalized on September 29, 1980, with September 29, 1990 as the payoff date. Ehrlich lost the bet, as all five commodities that were bet on declined in price from 1980 through 1990, the wager period.

Looks pretty good for Simon and the cornucopians. But the article continues:

Ehrlich could have won if the bet had been for a different ten-year period. Ehrlich wrote that the five metals in question had increased in price between the years 1950 to 1975. Asset manager Jeremy Grantham wrote that if the Simon–Ehrlich wager had been for a longer period (from 1980 to 2011), then Simon would have lost on four of the five metals. He also noted that if the wager had been expanded to “all of the most important commodities,” instead of just five metals, over that longer period of 1980 to 2011, then Simon would have lost “by a lot.” Economist Mark J. Perry noted that for an even longer period of time, from 1934 to 2013, the inflation-adjusted price of the Dow Jones-AIG Commodity Index showed “an overall significant downward trend” and concluded that Simon was “more right than lucky”. Economist Tim Worstall wrote that “The end result of all of this is that yes, it is true that Ehrlich could have, would have, won the bet depending upon the starting date. … But the long term trend for metals at least is downwards.”

How about today? An econblogger is still keeping track of the Ehrlich-Simon wager, and finds that as of August 2017, Simon (who is now dead) is still winning; a basket of the five metals involved still costs less than it did in 1980.

Can we zoom out even further? There are a bunch of commodity indices that do for commodities what the Dow Jones does for stocks. I chose the Standard & Poor Goldman-Sachs Commodity Index kind of randomly because they were a familiar name and it was easy to find which goods they included. I’m not quite sure I’m doing this right, but this seems to be the most relevant graph:

The price of commodities in general is still lower than in 1980 (also, with this graph it becomes clear Ehrlich was really unlucky in which year he started his wager).

I have never heard anyone claim that this represents an environmentalist victory: I don’t think there was any large-scale attempt to conserve or recycle chromium/tungsten/whatever that led to its current abundance. I think this was just a victory for resource extraction technology.

There are still theoretical reasons to think we have to run out of stuff eventually. But in terms of how the past 25 years have treated 90s-era concerns about resource depletion, it’s hard to answer anything other than “savagely”.

Verdict: Alarmist

7. Saving The Whales

I remember frequently being told we had to do this. Apparently it paid off, since a global moratorium on whaling was signed in 1982.

The ban is not perfect. Indigenous peoples are allowed to hunt whales in traditional ways. Japan pretends their whaling is for “scientific purposes” and has so far gotten away with it. Norway and Iceland never signed the moratorium and continue to whale.

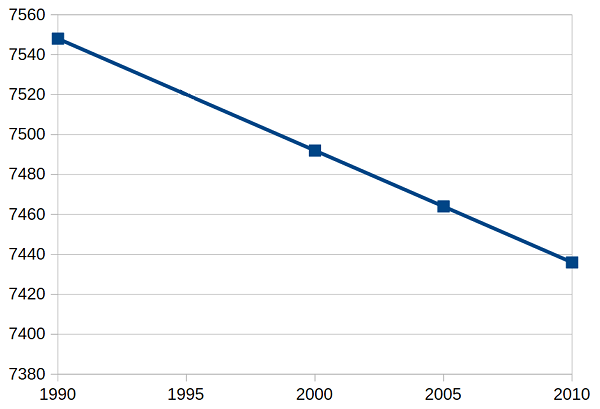

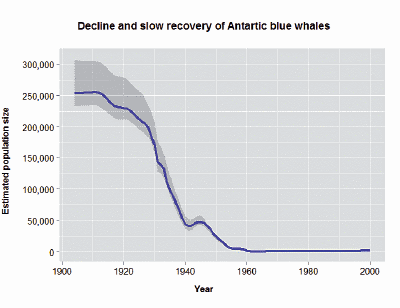

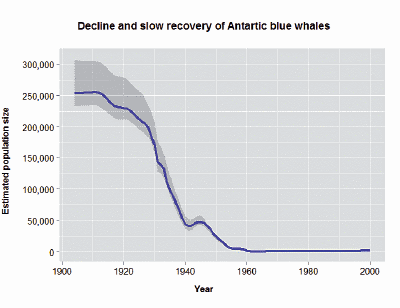

But overall, things are going pretty well. There aren’t a lot of graphs, but the International Whaling Commission (which despite its name is against whaling) says blue whale populations are increasing at about 8%/year, humpback whales around 10%, and fin whales around 5%. Those sound pretty good, but they have to be taken in context:

Okay, fine. There’s one graph. But it’s really depressing. See that tiny micro-bump at the end? That represents progress.

Verdict: Environmental movement successfully solved this problem.

8. Concluding Thoughts

This was not a very conclusive exercise. When I add these up – as if that were at all an acceptable thing to do! – I get 2⅓ that were solved, 2⅚ that were alarmism, and 1⅚ that continue. So there is not much to be said about them as a group. Some were solved through heroic effort. Some turned out to be completely made up. Some of them are still out there but have stopped capturing the public’s attention.

Victories I can understand. It’s the latter two categories that confuse me.

How did the non-problems fade away? There was no moment when some brave iconoclast posted ninety-five theses to the door of the local recycling center and said “No! There is not a landfill crisis!” I mean, John Tierney wrote things along those lines, and did a great job of it. But he’s not a household name and there was never a time when everyone said “Oh, John Tierney is right, let’s stop worrying about this.” The people who stopped worrying about this never heard of John Tierney. At some point people just went from being very worried about the landfill crisis to shaking their heads and saying “The world getting full of trash? Sounds pretty stupid.”

And the story with peak resources seems entirely different. You will still occasionally see people saying “The Earth can’t support our greed, soon we will run out of everything”, and reasonable people will nod along with this and admit it is very wise. But you hear it like once a year now, as opposed to it being a constant refrain. This idea was never intellectually defeated at all, at least not on the popular level. It just faded away.

Was there some rarified level of intellectual debate where these ideas lost out? And then, denied their support from the commanding heights of the ivory tower, did journalists stop writing about them, schoolteachers stop teaching them, and then eventually the public – who have no will of their own and have to be told what matters – wander off and do something else?

Or was the change bottom-up? Did the public, after the millionth editorial on the trash crisis, say “Okay, whatever”, such that journalists realized this was no longer a good way to sell newspaper subscriptions? Is there a natural news mega-cycle of a decade or so, after which the public gets tired of hearing about a certain story, the intellectuals get tired of talking about it, every possible angle has been explored, and people move on, whether or not it was solved? Does this explain why the rainforests, a real problem that is still going on, similarly lost public attention?

Or maybe climate change took over everything, became so important that everything else faded into the background. This is certainly how it feels to me. Whenever I hear about the rainforests nowadays, it’s as a footnote to some global warming story where they add that we should save the rainforest as a carbon sink. Whenever I hear about landfills or recycling today, it’s in the context of trash giving off greenhouse gases. It feels almost like some primitive barter system has been converted to a modern economy, with tons of CO2 emission as the universal interchangeable currency that can be used to put a number value on all environmental issues. Can’t figure out a way to convert whales into a carbon sink? Guess they’ll have to go.

(I wrote that, then remembered I lived in 21st century America, did a Google search, and sure enough there are dozens of articles arguing that saving whales is an efficient way to neutralize greenhouse gases)

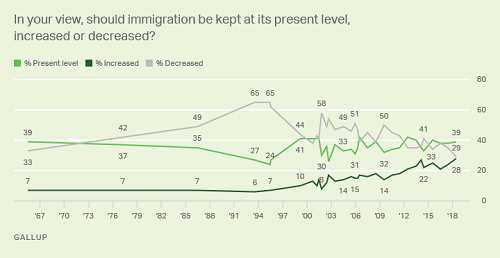

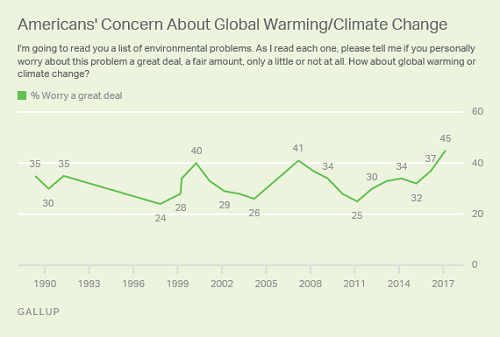

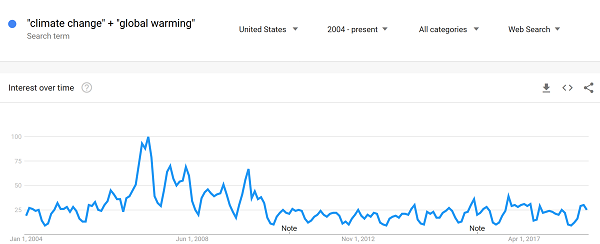

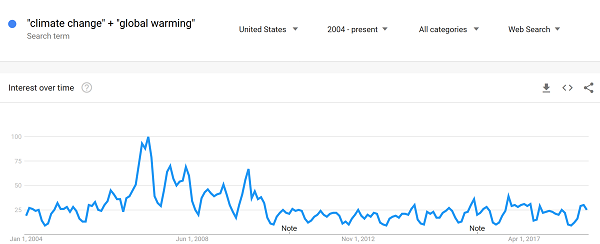

But as attractive as this picture is, it’s hard to find the supporting data. There’s just not hard evidence that we care more about global warming than we did fifteen or twenty years ago:

Here’s the Google Trends. There was a lot of interest in 2006, which I think gets attributed to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth in that year, but not a lot of signs of increase today.

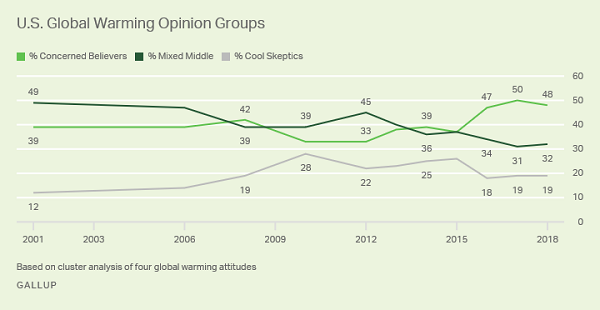

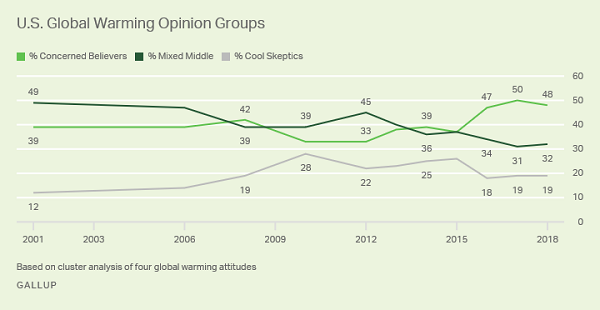

Here’s Gallup. It at least shows a spike starting in 2016 – but given its timing and the lack of obvious 2016 global-warming related events, I think it’s probably just another Trump backlash effect.

If global warming is eating all the other environmental issues, it doesn’t seem to be extracting that much nutrition from their corpses. And the ozone hole – probably the most global-warming-like issue of the last generation – managed to gather popular support at the same time that people were worried about a host of other things. I don’t know. Maybe given the public’s tendency to get bored of an issue after a decade or so, global warming has to cannibalize the rest of environmentalism just to survive at all. Depressing if true.

Or maybe it’s a zeitgeist thing. For some reason, it’s hard to imagine 2018 being the Year Of Rainforest Concern. There’s something very 90s Optimism about worrying about the rainforests, something where even the warnings of doom have a cheerful ring to them. I remember a Rainforest Charity Box at my local mall as a kid, promising that if you donated $10, you would save a brightly colored parrot, and if you donated $50, you might save a jaguar. Who thinks that way these days? Now if you donate some amount to stopping global warming, you will have won yourself a lecture from a bunch of people telling you that still doesn’t mean you have the right to feel good about yourself, and the world is going to fry regardless. Have we just passed the point where anybody can care about crisp mountain streams or frolicking snow leopards any more?

The most important thing I take away from the exercise is a sort of postmodern insight into the way environmental issues are constructed. This is definitely not me saying they are all made up; many of them are very real. But the mapping from real crisis to social panic is tenuous, contingent, and historical. Sometimes random things that shouldn’t matter get magnified into the issue du jour; other times giant world-threatening crises manage to slip everyone’s attention.

Imagine that twenty years from now, nobody cares or talks about global warming. It hasn’t been debunked. It’s still happening. People just stopped considering it interesting. Every so often some webzine or VR-holozine or whatever will publish a “Whatever Happened To Global Warming” story, and you’ll hear that global temperatures are up X degrees centigrade since 2000 and that explains Y percent of recent devastating hurricanes. Then everyone will go back to worrying about Robo-Trump or Mecha-Putin or whatever.

If this sounds absurd, I think it’s no weirder than what’s happened to 90s environmentalism and the issues it cared about.

Flickr/Tomas Del Coro

Flickr/Tomas Del Coro AP

AP

AP

AP

Reuters/Jonathan Bachman

Reuters/Jonathan Bachman

Thomson Reuters

Thomson Reuters Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/Associated Press

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/Associated Press

Thomson Reuters

Thomson Reuters

Hulu

Hulu

Three years ago, the Kardashian-Jenner sisters launched subscription-based personal apps to keep fans abreast of what was going on in their lives, connect with them directly outside of their various social media platforms and maybe earn a buck or two...

Three years ago, the Kardashian-Jenner sisters launched subscription-based personal apps to keep fans abreast of what was going on in their lives, connect with them directly outside of their various social media platforms and maybe earn a buck or two...

Tobacco giant Altria (which owns Marlboro and Virginia Slims) has bought a 35 percent stake in Juul for $12.8 billion. The major deal pegs the e-cigarette company's valuation at $38 billion, which more than doubles its value since a previous investme...

Tobacco giant Altria (which owns Marlboro and Virginia Slims) has bought a 35 percent stake in Juul for $12.8 billion. The major deal pegs the e-cigarette company's valuation at $38 billion, which more than doubles its value since a previous investme...

If you've always wanted to play basketball in a pair of self-lacing shoes like Marty McFly's Nike Mags, you will get your chance next year. On the company's quarterly earnings call executives revealed plans for an "Adaptive" performance basketball sh...

If you've always wanted to play basketball in a pair of self-lacing shoes like Marty McFly's Nike Mags, you will get your chance next year. On the company's quarterly earnings call executives revealed plans for an "Adaptive" performance basketball sh...

The FDA has given the ProAir Digihaler, a digital and mobile-connected inhaler that comes with built-in sensors, its sweet approval. Those sensors can detect whenever the device is used and even measure the strength of the user's inhalation. More imp...

The FDA has given the ProAir Digihaler, a digital and mobile-connected inhaler that comes with built-in sensors, its sweet approval. Those sensors can detect whenever the device is used and even measure the strength of the user's inhalation. More imp...

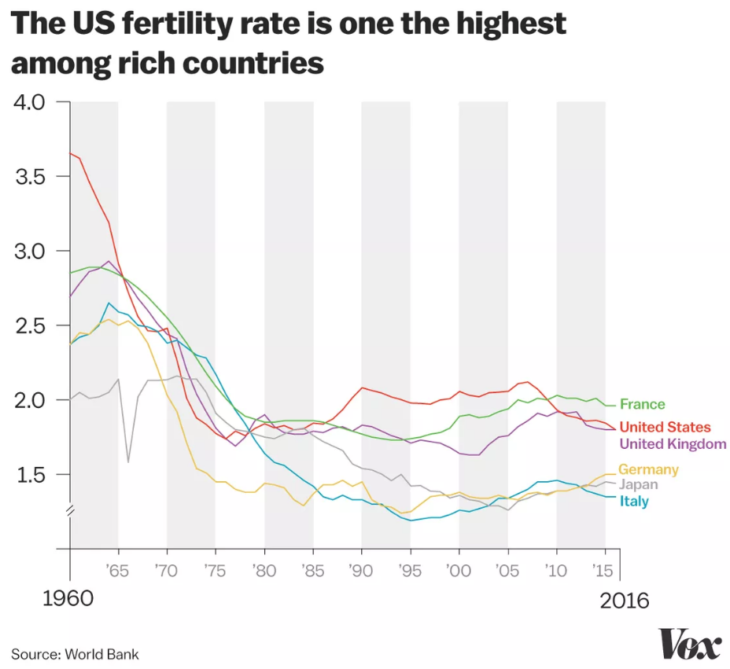

The US population has gone from growing about one percentage point faster than the EU in the 1990s, to perhaps a third of a point faster today.

The US population has gone from growing about one percentage point faster than the EU in the 1990s, to perhaps a third of a point faster today.