Nathanstodola

Shared posts

Utterly Unqualified 4-Year-Old Crashes Wedding To Pose As Flower Girl

A 4-year-old child weaseled her way into a stranger's wedding after manipulating an unsuspecting couple at City Hall, using her sweet, earnest face and a charming handmade sign to obscure the fact that she sorely lacked even the basic qualifications required to launch a career as flower girl. [ more › ]

A 4-year-old child weaseled her way into a stranger's wedding after manipulating an unsuspecting couple at City Hall, using her sweet, earnest face and a charming handmade sign to obscure the fact that she sorely lacked even the basic qualifications required to launch a career as flower girl. [ more › ]Predictions for Privacy in the Age of Facebook (from 1985!)

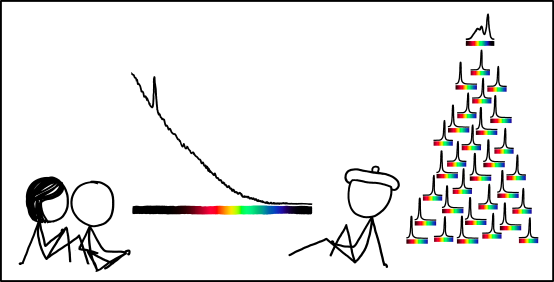

![]()

Cover of the January 1985 issue of Whole Earth Review (Source: Novak Archive)

“The ubiquity and power of the computer blur the distinction between public and private information. Our revolution will not be in gathering data — don’t look for TV cameras in your bedroom — but in analyzing information that is already willingly shared.”

Are these the words of a 21st century media critic warning us about the tremendous quantity of information that the average person shares online?

Nope. It’s from a 1985 article for the Whole Earth Review by Larry Hunter, who was writing about the future of privacy. And it’s unlikely Mr. Hunter could have any more accurately predicted the Age of Facebook — or its most pervasive fears.

Hunter begins his article by explaining that he has a privileged peek into the computerized world that’s just over the horizon:

I live in the future. As a graduate student in Artificial Intelligence at Yale University, I am now using computer equipment that will be commonplace five years from now. I have a powerful workstation on my desk, connected in a high-speed network to more than one hundred other such machines, and, through other networks, to thousands of other computers and their users. I use these machines not only for research, but to keep my schedule, to write letters and articles, to read nationwide electronic “bulletin boards,” to send electronic mail, and sometimes just to play games. I make constant use of fancy graphics, text formatters, laser printers — you name it. My gadgets are both my desk and my window on the world. I’m quite lucky to have access to all these machines.

He warns, however, that this connectedness will very likely come with a price.

Without any conspiratorial snooping or Big Brother antics, we may find our actions, our lifestyles, and even our beliefs under increasing public scrutiny as we move into the information age.

Hunter outlines the myriad ways that corporations and governments will be able to monitor public behavior in the future. He explains how bloc modelling helps institutions create profiles that can be used for either benign or nefarious purposes. We can guess that credit service companies beginning to sell much more specific demographic information to credit card companies in the early 1980s generally falls into the nefarious column:

How does Citicorp know what your lifestyle is? How can they sell such information without your permission? The answer is simple: You’ve been giving out clues about yourself for years. Buying, working, socializing, and traveling are acts you do in public. Your lifestyle, income, education, home, and family are all deductible from existing records. The information that can be extracted from mundane records like your Visa or Mastercard receipts, phone bill, and credit record is all that’s needed to put together a remarkably complete picture of who you are, what you do, and even what you think.

And all this buying, working and socializing didn’t even include through mediums like Facebook or Twitter in 1985. Hunter explains that this information, of course, can be used in a number of different ways to build complex pictures of the world:

While the relationship between two people in an organization is rarely very informative by itself, when pairs of relationships are connected, patterns can be detected. The people being modeled are broken up into groups, or blocs. The assumption made by modelers is that people in similar positions behave similarly. Blocs aren’t tightly knit groups. You may never have heard of someone in your bloc, but because you both share a similar relationship with some third party you are lumped together. Your membership in a bloc might become the basis of a wide variety of judgements, from who gets job perks to who gets investigated by the FBI.

In the article Hunter asks when private information is considered public; a question that is increasingly difficult to answer with the proliferation of high-quality cameras in our pockets, and on some on our heads.

We live in a world of private and public acts. We consider what we do in our own bedrooms to be our own business; what we do on the street or in the supermarket is open for everyone to see. In the information age, our public acts disclose our private dispositions, even more than a camera in the bedroom would. This doesn’t necessarily mean we should bring a veil of secrecy over public acts. The vast amount of public information both serves and endangers us.

Hunter explains the difficulty in policing how all of this information being collected might be used. He makes reference to a metaphor by Jerry Samet, a Professor of Philosophy at Bentley College who explained that while we consider it an invasion of privacy to look inside someone’s window from the outside, we have no objection to people inside their own homes looking at those outside on the public sidewalk.

This is perhaps what makes people so creeped out by Google Glass. The camera is attached to the user’s face. We can’t outlaw someone gazing out into the world. But the added dimension that someone might be recording that for posterity — or collecting and sharing information in such a way — is naturally upsetting to many people.

Why not make gathering this information against the law? Think of Samet’s metaphor: do we really want to ban looking out the window? The information about groups and individuals that is public is public for a reason. Being able to write down what I see is fundamental to freedom of expression and belief, the freedoms we are trying to protect. Furthermore, public records serve us in very specific, important ways. We can have and use credit because credit records are kept. Supermarkets must keep track of their inventories, and since their customers prefer that they accept checks, they keep information on the financial status of people who shop in their store. In short, keeping and using the kind of data that can be turned into personal profiles is fundamental to our way of life — we cannot stop gathering this information.

And this seems to be the same question we ask of our age. If we volunteer an incredibly large amount of information to Twitter in exchange for a free communications service, or to Visa in exchange for the convenience of making payments by credit card, what can we reasonably protect?

Hunter’s prescription sounds reasonable, yet somehow quaint almost three decade later. He proposes treating information more as a form of intangible property, not unlike copyright.

People under scrutiny ought to be able to exert some control over what other people do with that personal information. Our society grants individuals control over the activities of others primarily through the idea of property. A reasonable way to give individuals control over information about them is to vest them with a property interest in that information. Information about me is, in part, my property. Other people may, of course, also have an interest in that information. Citibank has some legitimate interests in the information about me that it has gathered. When my neighbor writes down that I was wearing a red sweater, both of us should share in the ownership of that information.

Obviously, many of Hunter’s predictions about the way in which information would be used came true. But it would seem that there are still no easy answers to how private citizens might reasonably protect information about themselves that’s collected — whether that’s by corporations, governments or other private citizens.

Chillingly, Hunter predicted some of our most dire concerns when Mark Zuckerberg wasn’t yet even a year old: “Soon celebrities and politicians will not be the only ones who have public images but no private lives — it will be all of us. We must take control of the information about ourselves. We should own our personal profiles, not be bought and sold by them.”

What do you think? Does our age of ubiquitous sharing concern you? Do you think our evolving standard of what is considered private information generally helps or hurts society?

Somebody Is Scalping A Planet Money T-Shirt For $350

Somebody Is Scalping A Planet Money T-Shirt For $350

by Jacob Goldstein

That was fast!

9())

Why (Almost) No One In Myanmar Wanted My Money

Why (Almost) No One In Myanmar Wanted My Money

by Robert Smith

When you arrive in Myanmar, you can see how eager the people are to do business. At the airport in Yangon, new signs in English welcome tourists. A guy in a booth offers to rent me a local cellphone — and he's glad to take U.S. dollars. But when I pull out my money, he shakes his head.

"I'm sorry," he says.

He points to the crease mark in the middle of the $20 bill. No creases allowed.

So I pull out another, which he rejects because it's a little bit faded, and a third, which he doesn't want because of a tiny tear, and a fourth, which he calls "not very acceptable" because of a little ink spot.

Myanmar, also known as Burma, was largely closed to the world for decades. It's just getting used to the business of international currency exchange. And, like other countries that have gone through economic turmoil (Russia, Iraq, Argentina), Myanmar wants U.S. dollars to look like they just rolled off the presses.

When I start to ask people in Myanmar, they laugh and say they know it's crazy. But they've learned in their history that the last thing you can trust is an old piece of money.

You've probably heard about the human rights abuses under the former dictatorship in Burma. But the old government also used to screw with the money all the time. Officials would suddenly announce that certain denominations of the local currency were worthless. It would be like waking up to find that the $100 bill was worthless.

The old socialist government was worried that some people were getting rich, Zeya Thu, an editor with The Voice, told me. So without warning, they would take the largest denominations out of circulation.

When it happened in 1987, Zeya's parents were getting ready for retirement. They had just cashed out their life savings to buy a plot of land. They were in the room with the seller, about to buy the land, and the government came on the radio and said the bills were worthless.

The country's leader created new bills overnight in denominations that were multiples of nine — his lucky number. Zeya says the math of adding and subtracting 45s would give people headaches.

So people started to sock away their extra money in U.S. currency. And when your life savings is a few U.S. $100 bills, you want to keep them pristine. Like other people in Myanmar, my translator kept his U.S. bills pressed flat in the pages of a book. Like baseball card collectors, people in Myanmar want their bills in mint condition.

The banks in Myanmar could have solved this problem by accepting old U.S. currency. But for a long time they were cut off from U.S. banks by sanctions, so they didn't want the old bills, either.

As a result, visitors to Myanmar have to bring bills so crisp you can cut tomatoes with them. And bills that are less than perfect end up on the black market. I took my $20 bill with a tiny ink spot on it to a black-market money changer. He gave me $17.75 for it.

9())

Scientists: 7 line extension safe from electric eels

In what is possibly the weirdest MTA-related story in years, DNA Info reports today that the 7 line extension is safe from electric eels. Now, an astute reader may be wondering how this came about a year before the project is due to wrap and why anyone would be focusing on electric eels in the first place. Well, the story is quite strange.

As Jill Colvin reports, MTA Board Member Charlie Moerdler raised the issue at a recent board member when he claimed to remember eels coming ashore and wreaking havoc on metal pipes during construction of the Javits Center. Moerdler helped the Javits Center secure an exemption to New York’s plumbing rules, and the convention center received permission to use plastic piping. “That’s the issue. Does it apply to the 7 line and does it apply to the area where the Hudson Yards is?” he asked.

Colvin dug up the March 1980 Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Javits Center and could find no mention of electric eels raising any alarms. She also spoke with the eel project coordinator at the Hudson River Eel Project who said that electric eels do not live in New York Harbor or the Hudson River. “I don’t think you have to worry about electric eel damage,” Chris Bowser said. The MTA, meanwhile, has no plans to to eel-proof the West Side subway extension, and I for one am glad that’s settled.

New York Lawmakers Are Looking To Ban Shark Fin

NathanstodolaNo sharkfin, but court rules large soda sales must remain.

Shark fin, the controversial Chinese "delicacy", is still legal in New York, much to the disgust of many environmentalists, animal lovers and humane society groups. But a re-introduced bill aims to finally take shark fins off menus and specialty store shelves, proposing to ban its sale statewide. [ more › ]

Shark fin, the controversial Chinese "delicacy", is still legal in New York, much to the disgust of many environmentalists, animal lovers and humane society groups. But a re-introduced bill aims to finally take shark fins off menus and specialty store shelves, proposing to ban its sale statewide. [ more › ]

Video: Massive Brawl At Albany St. Patrick's Day Parade Makes Us Relieved We Don't Live In Albany

We've spent some time today documenting all the ways yesterday's St. Patrick's Day Parade was a bit of a shitshow, what with the street fights, the fratty revelers, and that damn Swedish Chef (okay, that last one is obviously awesome). But nothing we came across in our area is as bad as what went on in Albany this weekend, as you can see in the massive brawl video below that will surely make you reconsider whether to have children. [ more › ]

We've spent some time today documenting all the ways yesterday's St. Patrick's Day Parade was a bit of a shitshow, what with the street fights, the fratty revelers, and that damn Swedish Chef (okay, that last one is obviously awesome). But nothing we came across in our area is as bad as what went on in Albany this weekend, as you can see in the massive brawl video below that will surely make you reconsider whether to have children. [ more › ]