Adjust your hot election takes accordingly.

Doug Jones’s victory over Roy Moore Tuesday night in Alabama’s special election for US Senate was enough of a shock that most political pundits didn’t have ready-made explanations for why it happened. So in the aftermath, they’re poring over what little data they have to determine which groups of voters helped push Jones over the top by showing up to vote for him, and who hurt Moore worst by staying home.

The easiest way to draw these conclusions is to look at the exit polls conducted while Alabamians were voting. The exit polls are, in some ways, more detailed than the official voting tallies. And because they break down votes by demographic groups, they can often present ready-made narratives — like the idea in Alabama that black voters, and especially black women (who made up 18 percent of the electorate but voted 97 percent to 3 percent for Jones) “saved” the election for the Democratic Party.

One huge problem with interpretations based on exit polls in the Alabama special election is that pollsters simply didn’t conduct exit polls in the state in 2016, so it’s difficult to say how much of what happened in the state is due to, say, energized black turnout versus depressed white turnout.

Exit polls can be useful. But there’s also good reason to be a little skeptical of using them to interpret a vote after the fact — because that’s not what they’re designed to do. Here’s what you need to know.

How the exit poll works

Every November election — and during particularly important special elections, like Tuesday’s Senate election in Alabama — exit polls are conducted by a group of media outlets called the National Election Pool: NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, CNN, and the Associated Press. They hire a pollster to conduct the exit poll, but they're the ones that own the information — and that get to be the first to report the results.

That is the key to the exit poll. It is designed to allow the media to know as quickly as possible who has won the election. That means that when designing the poll, pollsters don’t focus on collecting as much data as possible — they focus on collecting the smallest amount of data that’s still going to reliably predict who has gotten more votes.

In a national election, that means that safe red or blue states (like Alabama) don’t get the full attention of exit pollsters. Exit pollsters still send people to do interviews there, for the purpose of the national poll, but they don’t collect enough interviews to publish reliable poll results.

So in addition to all the other factors that made the Senate special election so hard for pollsters to predict, the exit poll had the added factor of working in a state that it hadn’t held operations in for several years. That’s one good reason to be skeptical that it perfectly captured the state of the electorate.

The actual polling happens in two parts.

The most visible part of the poll happens in person on Election Day. An army of thousands of interviewers are sent to hundreds of polling places around the country. Interviewers approach a certain number of voters who are leaving the polling place — the exact fraction surveyed is secret — and ask them to fill out the written exit poll survey. In 2016, pollsters estimated they’d interview about 85,000 people on Election Day around the country — obviously, the number in Alabama in 2017 would be much smaller.

But part of the exit poll has already happened before Election Day. As early voting has become more popular, it's gotten harder to predict vote totals just by talking to people who vote on Election Day. So for the past several elections, exit pollsters have started calling people and asking if they voted early or absentee, and then conducting exit poll interviews by phone. (In 2016, pollsters estimated they’d contact about 16,000 voters this way.)

What the exit poll can — and can’t — tell us

The exit poll isn’t just about whom people voted for — that’s why there are interviewers even in safe states. Voters are asked to provide basic demographic information like gender, age, and ethnicity. Furthermore, they're asked some questions about their personal viewpoints and behaviors — like their religion and churchgoing habits — and questions about major issues facing the country.

That means the exit poll data is actually more detailed, in some ways, than the official US Census vote tallies that come out several weeks after the election. It can offer the first hints — and often the most important ones — to what voters thought this election was about. That's very important to pundits as they try to interpret what it means.

In 2004, for example, post-election chatter focused on "values voters." Voters who attended religious services regularly had overwhelmingly voted for George W. Bush. That narrative came out of the exit poll data.

Of course, what voters say is important to them is partly what campaigns have told voters is important. There's political science research suggesting that when a campaign hammers particular issues, those are the issues that the candidate's supporters say are most important to them. But the exit poll is still the best opportunity the national media has, in some ways, to figure out who voted, why, and how.

That said, there are some big questions about using the exit poll to draw sweeping conclusions. The first problem is that the exit poll only covers people who actually voted — meaning that it can obscure turnout problems on one side or the other.

In Alabama, for example, the exit poll showed that white voters overwhelmingly supported Roy Moore — but without more information about how many white voters stayed home because they were unwilling to support Moore, it’s hard to draw a conclusion about the role white voters played in the election.

For the most part, though, the exit poll is a lot more reliable when it comes to white voters than when it comes to nonwhite voters. And this is where it becomes really important to understand the exit poll’s limitations when talking about Doug Jones’s election.

The exit polls’ blind spots make it hard for them to analyze voters of color

There are some particular challenges that exit polls have faced for the past several elections that they still haven't found a way to work out. And as it happens, those challenges tend to involve voters of color.

Early voters. The phone poll for early voters is a relatively new addition to the exit poll— and it’s still a relatively minor one, compared with in-person polling. Early voting itself, meanwhile, has gotten very popular very quickly. In key states like Nevada and Florida, it’s estimated that fewer people will show up to vote on Election Day than showed up during early voting.

The exit poll understands the huge role early voters will play — pollsters estimated to Pew that 35 to 40 percent of all voting would happen early in 2016 — but it’s not clear that their polling can accurately capture who those people are. It runs into the problems any phone poll has — namely, that it's difficult to poll people who only have mobile phones.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2377730/457549036.0.jpg)

Networks can work around the early-voting blind spot when they’re using the exit poll for its intended purpose — which is, again, calling the race accurately as soon as possible. In areas where they know early voting has been heavy, they can delay calling close races even if the exit poll suggests one candidate will win. But the demographic and other data the exit poll provides might be skewed in favor of people who voted in person — who might not be the voters who decided this election.

Small groups. Like any poll, the smaller a sample size is, the less likely it is to be representative. So the exit poll is pretty reliable when it comes to large demographics (men, women, Democrats, Republicans) but less reliable when it gets to small demographics (young voters, Jewish voters).

Voters of color. In addition to the general problems with smaller voting demographics, analysts believe the exit poll has a tendency to oversample a particular kind of voter of color — the kind who lives in majority-white areas.

Here's the logic. Even though the public doesn't know exactly how the exit poll chooses where to go, it's possible to make some educated guesses. The exit poll is trying to predict the margin of victory for one candidate over another across the state. So when it decides which polling places to put interviewers outside of, it's reasonable to assume that it's choosing lots of swing precincts — precincts that are harder to predict and likely to affect the outcome. Those are going to be largely white precincts.

Alternatively, says Matt Barreto of Latino Decisions, exit pollsters might choose a precinct as a benchmark based on the previous cycle. For example, if a precinct voted for the Democratic senator 70 percent to 30 percent in 2008, the pollster might choose to put an exit poll interviewer at that precinct to see if the Democrat is getting less than 70 percent of the vote this time around. But pollsters are not necessarily paying attention to the racial makeup of those precincts.

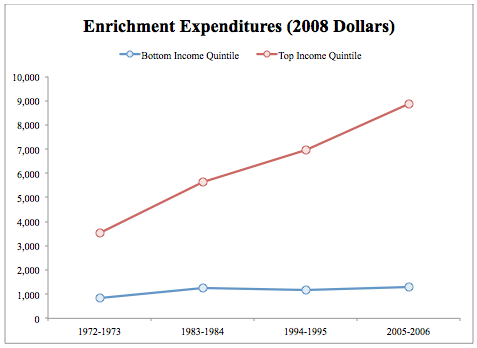

Here's why this is a problem: The voters of color that pollsters run into in majority-white precincts might not be representative of the voters of color across the state. In particular, according to Latino Decisions, voters of color living among whites are "more assimilated, better educated, higher income, and more conservative than other minority voters."

Check out the difference in the percentage of nonwhite voters who had a college degree in 2010, according to the US Census versus the exit poll:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2424660/Screen_Shot_2014-11-03_at_4.32.31_PM.0.png) Latino Decisions

Latino Decisions

(The problem is even worse for Latino voters, because exit polls are almost never offered in Spanish — even though more than a quarter of Latino voters prefer Spanish to English. So the exit polls oversample English-speaking Latinos.)

When it comes to the Alabama election, it certainly doesn’t look like the exit pollsters overstated the conservatism of black voters. But they might have made incorrect assumptions about what share of the electorate black men and black women made up, based on where they saw black voters at the polls. Conversely, it’s possible that they overstated the conservatism of certain white groups — like white voters without college degrees — because they were polling in more affluent “swing” areas, where such voters would be more conservative.

Any errors the exit poll made were probably on the margins. It is almost certainly still the case that white voters strongly supported Moore and black voters overwhelmingly supported Jones. But the bigger conclusions one tries to draw from a single race, the more important it is to recognize the limitations of what we know about what actually happened there.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6846935/GettyImages-505548480.jpg) Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Chip Somodevilla/Getty

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5924593/huffpoll-2016-iowa-jan.png) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926465/dem-debate.jpg) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926473/chess-defense.jpg) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926499/obama-tunnel-vision.jpg) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926479/obama-mcconnell.jpg) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926571/yes-we-can.jpg) (

(/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926621/clinton-sanders-debate-2.jpg) (

(

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4139120/StateSenateControl-Post-Election-GIF.0.gif)

(

(

is involved in nine different social responsibility things—it’s ingrained in most public—

is involved in nine different social responsibility things—it’s ingrained in most public—

environmental message than when it was unlabeled." But Tim Carney points out that

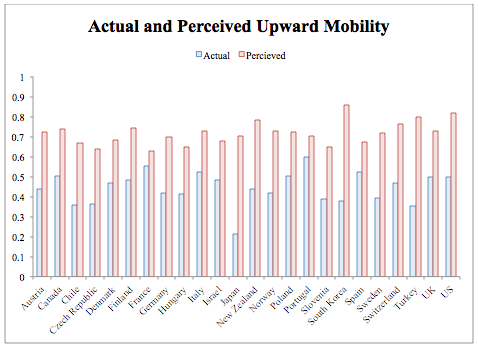

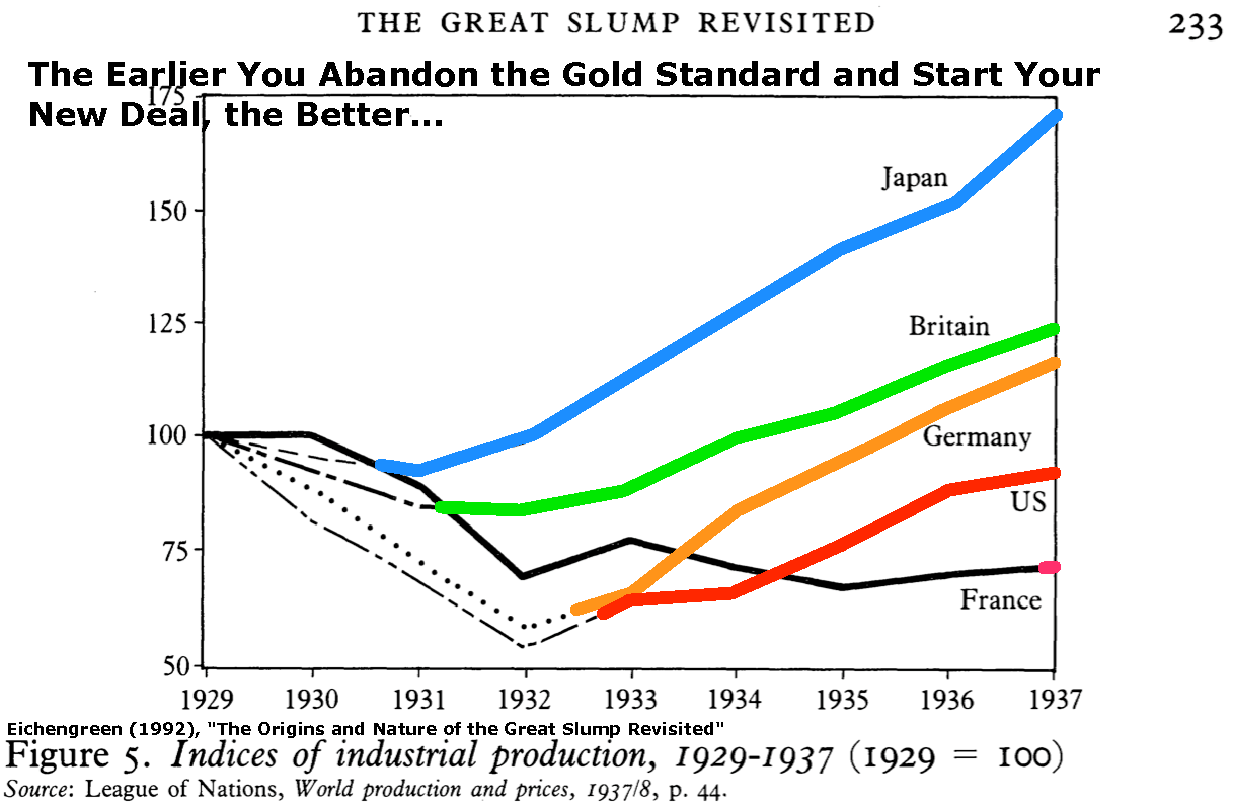

environmental message than when it was unlabeled." But Tim Carney points out that  same period. Guess what? It turns out that in countries where the rich got the richest,

same period. Guess what? It turns out that in countries where the rich got the richest,