Mr. Rogers Introduces Kids to Experimental Electronic Music by Bruce Haack & Esther Nelson (1968). Made me smile.

Shared posts

Women’s March Protest Signs

Wow, this archive of Women’s March protest signs is impressive. So many good ones to chose from. (You can download them and tile-print them on your home printer or download a high-res pdf to have printed at your local print shop.)

BLOW Photo Series from Illona Haus of Scruffy Dog Photography

What happens when you place a dog and a fan together in the same room? Apparently some pretty hilarious expressions and a few magical moments! Ontario-based animal photographer Illona Haus of Scruffy Dog Photography has been exploring the surprising and often humorous way dogs interact with these portable wind machines in her newest series BLOW. Responses range from confusion to playfulness to utter relaxation! Take a peek at a few of our favorite images from this series below and be sure to check out more of Illona’s work on scruffydogphotography.com.

Share This: Twitter | Facebook | Don't forget that you can follow Dog Milk on Twitter and Facebook.

© 2017 Dog Milk | Posted by capree in Other | Permalink | No comments

Garlic Blast Off

This Garlic Blast Off Miniature Diorama made me chuckle.

Womens March Posters by Tia

These downloadable Women’s March Posters are fantastic. You can also design your own!

I’ll be attending the Women’s March here in NYC on Saturday, handing out custom Womens March Tattly. Follow me on Instagram the day of the March, if you want to get your hands on some.

(via Carly)

Tragedy Would Unfold If Trump Cancels Bush’s AIDS Program

In 2003, in a move that has been described as his greatest legacy, George W. Bush created a program called PEPFAR—the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. At the time, more than 20 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living with AIDS, but only 50,000 had access to antiretroviral drugs that manage the disease and prevent its spread. Now, thanks to PEPFAR, 11.5 million people are on those drugs. For good reason, it has been variously described as a “globally transformative lifeline,” “one of the best government programs in American history,” and something “for all Americans to be proud of.”

It seems that some members of President-Elect Trump’s transition team beg to differ.

Last Friday, Helene Cooper at The New York Times reported that the transition team sent a four-page questionnaire to the State Department about America’s relationship with Africa, on topics ranging from terrorism to humanitarianism. Several questions indicated “an overall skepticism about the value of foreign aid.” Two mentioned PEPFAR in particular: “Is PEPFAR worth the massive investment when there are so many security concerns in Africa? Is PEPFAR becoming a massive, international entitlement program?”

Without knowing the specific author, “it’s hard to assess the intent of those questions, but at face value, they represent a point of view that is skeptical in the least and barely veiled hostility at the most,” says Jack Chow, who worked at the State Department under Colin Powell and acted as an ambassador focusing on HIV. “They could be aimed at provoking a justification—an aim that is not too uncommon for these kinds of inquiries.”

For those who work in public health, the justification is clear. “It’s very clear that PEPFAR has saved an incredible number of lives in the past decade,” says Rebecca Katz, Co-Director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University.

Bush initially committed $15 billion to PEPFAR over five years, but the program was renewed in 2008 and 2013 and has since received over $72 billion in funding. As well as disseminating treatments, that money has: funded HIV testing and counseling for 74 million people; provided critical care and support to 6 million orphans and vulnerable children; prevented 2 million babies from being born with HIV by offering drugs to mothers; trained 220,000 health workers; supported 11 million voluntary male circumcisions to prevent the spread of HIV; improved health care in the various focus countries; and supported services for controlling other diseases like malaria and tuberculosis.

While PEPFAR program has been criticized for also funding ineffective attempts to prevent HIV infections by teaching abstinence and faithfulness, such efforts only used up a small and decreasing proportion of the program’s money. The vast majority of the funds went towards evidence-based practices—with demonstrable results.

One study showed that within five years, PEPFAR had roughly halved the adult death rates in nine targeted countries, at a time when mortality in other sub-Saharan African nations barely declined. During that period, African adults were 16 percent less likely to die if they lived in one of the PEPFAR-targeted nations. Another project found that in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, HIV incidence has fallen by 51 to 76 percent since 2003, and 65 percent of infected adults are successfully suppressing the virus to a point where they’re much less likely to transmit it. “That’s almost touching the 73 percent level that’s predicted to really give us epidemic control,” says Elizabeth Radin from Columbia University, who was involved in the research. “It’s a remarkable achievement compared to where we were 15 years ago.”

PEPFAR “helped changed the equation on what was once—not too long ago—seen as an insurmountable plague,” wrote Amanda Glassman and Jenny Ottenhoff from the Center for Global Development in 2013. And it “managed to maintain bipartisan support that bridged two U.S. Administrations, six U.S. congressional sessions, and one global economic crisis.” It’s a tribute to what can be accomplished with sustained funding and political unity.

Indeed, Obama has taken flak from congressional Democrats and Republicans for halting the year-on-year rise in PEPFAR funding, and slightly reducing it on several occasions. “The current administration’s comparative neglect of it demonstrates that its existence and survival are anything but guaranteed,” wrote Dylan Matthews in 2015.

Defunding the program would be catastrophic. Antiretroviral drugs aren’t a cure for AIDS; they must be taken continuously, lest the disease flare up again. “To sustain that therapy, there are substantial pipelines involving supply chains, financing mechanisms, and myriads of organizations,” says Chow. “Disruptions risk rekindling HIV.”

Trump has actually commented about PEPFAR once—sort of. At a conference in October, a group of college students asked him if he would commit to doubling the number of people receiving treatment through the program to 30 million by the year 2020. “Those are good things,” he replied. “Alzheimer’s, AIDS. We are close on some of them. On some of them, honestly, with all of the work done which has not been enough, we’re not close enough. The answer is yes. I believe strongly in that and we are going to lead the way.” If you squint a bit, that looks like a yes. But as I noted last month, it’s unclear if Trump actually understood the question, given that PEPFAR doesn’t cover Alzheimer’s.

More encouragingly, Rex Tillerson, former ExxonMobil CEO and Trump’s nominee for Secretary of State, unequivocally praised PEPFAR during his Senate confirmation hearing last week. It “has been one of the most extraordinarily successful programs in Africa,” he said. “I saw it up close and personal because ExxonMobil had taken on the challenge of eradicating malaria because of business activities in Central Africa.” (ExxoMobil is one of several companies that contribute to the Global Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis & Malaria.)

Tillerson’s answer hints at something crucial: PEPFAR’s impact goes well beyond AIDS. It also helps to curtail future epidemics that begin in sub-Saharan Africa and threaten to spread to other continents. “What do we do to keep Ebola out of the U.S.? We build capacity in the countries that need it most,” says Katz. “And PEPFAR has unquestionably contributed to building foundations for systems that can be used to fight the next pandemic.”

And since AIDS hits people of working and reproductive ages the hardest, the social benefits of controlling it are huge. Compared to other countries, those targeted by PEPFAR have a better opinion of the U.S. Their male employment rates are 13 percent higher, creating economic benefits that are equal to half the amount spent. They have developed three times faster. Their levels of political instability and violent activity have fallen by 40 percent since 2004, compared to just 3 percent in non-PEPFAR countries. All of this benefits the U.S., creating markets for exports and reducing the instability that leads to extremism.

This is why the transition team’s questionnaire, which juxtaposes PEPFAR investments against the “many security concerns in Africa,” makes no sense, says Radin. “Controlling the AIDS epidemic is in the interest of national security,” she says. “It’s not a zero-sum game.” And speaking of sums, the $6.8 billion committed to PEPFAR in 2015 was just 1 percent of what the U.S. devoted to military spending.

She also frowns on the question that portrays PEPFAR as a “massive, international entitlement program.” “There’s an important argument that says that just by dint of being a human being, you’re entitled not to die from a treatable disease, especially for just a few hundred U.S. dollars a year,” she says. “That entitlement isn’t predicated on your ability to pay global market prices for treatments.”

Primer and Twin Primer Machine

Weirdly intrigued by this simple looking hand made machine. Press the button and it spins up to the next prime number. That’s it. Nothing else. So nerdy and refreshing. See it in action here.

Don’t say that word!

This made me cry-laugh just now.

Online Knitting Reference Library

This Online Knitting Reference Library post over on Open culture made me laugh. Go and Download 300 Knitting Books Published From 1849 to 2012!

Giraffes Edge Closer to Extinction

The tallest animal in the world is surprisingly inconspicuous. I remember stumbling across one for the first time, as our safari jeep skirted around a random Kenyan bush. There it was. A giraffe. Instantly recognizable, and utterly incongruous in the flesh.

There’s the face—like a camel’s, but more pensive and streamlined. There are the comical tufty horns, the long eyelashes, and the dextrous, purple tongue. There’s that extreme neck, which multi-tasks as a ladder for reaching lofty shoots, a sledgehammer for brutalizing rivals, and a source of dispute for both evolutionary biologists and Fashion Twitter. And there’s the absurd, baffling verticality of the entire creature. J. M. Ledgard put it best in his novel Giraffe: “I am a giraffe, I am about that space a little above the blade, and my bodily intent is to be elevated above all other living things, in defiance of gravity.”

Then there’s the unmistakeable hide. The exact pattern varies between the different subspecies, but all of them feature brown islands separated by criss-crossing white lines. That, coincidentally, is exactly what giraffe habitats are like.

Their homes have become increasingly fragmented by human activity, with once-continuous stretches of forest and savannah broken up by roads and fences. They might be emblems of verticality, but they also roam over great horizontal distances, in search of better and more nutritious food. Constrained by humans, they’re now forced to feed on poorer foliage, leaving them in poorer health. And as different populations become disconnected, each isolated pocket becomes dangerously vulnerable to deforestation, drought, poachers, and troops from war-torn states who see giraffes as military rations. As Jules Howard puts it: “Nine small puddles will evaporate far more quickly than one big puddle, and so it is with life.”

This is a recurring theme in the natural world: Fragmentation brings disaster. It’s as if the cause of the giraffe’s downfall has been painted onto its hide.

In just 30 years, the giraffe population has fallen up to 40 percent, from between 152,000 and 163,000 animals in 1985 to just 98,000 in 2015. This dramatic decline is reflected in the latest edition of the Red List of Threatened Species—the ever-depressing inventory in which the International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies the world’s wildlife into various shades of screwed. Giraffes used to be in the safest bracket: “Least Concern.” As of this week, they’ve been shunted into “Vulnerable”—a two-step demotion, and four steps away from total extinction.

The situation may even be worse than we think, because the Red List treats all giraffes as part of a single species, divided into nine subspecies. But one group of scientists recently found that some of these are genetically distinct enough to count as species in their own right. By their reckoning, there are four species of giraffe, each living in a different part of Africa. Now, those 98,000 individuals have been split into four populations, two of which—the northern and reticulated giraffes—have fewer than 10,000 individuals each.

“Unfortunately, this decline has occurred with little fanfare or public attention,” wrote conservation reporter John Platt in 2014. Conservationists have panicked (quite reasonably) over the fate of the African elephant, but there are five of these mammals for every one giraffe. As I said: The tallest animal in the world is surprisingly inconspicuous. It’s easy to look up at a giraffe, but apparently even easier to look away.

To save the giraffe, people will need to take notice. Niger did so in the 1990s, when there were just 49 giraffes in all of West Africa. In response, the government developed a National Giraffe Conservation Strategy—the first and only one to date. Critically, the strategy involved education: conservationists reached out to local communities and taught them about the giraffe’s perilous state. As a result, the population has since rebounded to 450 and counting, and these giraffes live in peaceful proximity to human villagers.

Kenya is now finalizing a similar strategy, and other countries may follow suit. Specialist organizations like the Giraffe Conservation Foundation are trying to coordinate and boost these efforts. Such coordination is essential, and perhaps even cause for optimism. As Howard writes, “Today’s world contains perhaps the biggest, most spectacular thing that natural selection is capable of producing: coordinated minds that seek to save things other than themselves—the minds of humans, when we’re at our best.”

Perhaps the news of the giraffe’s decline is a fitting end for 2016—a year in which our own species has repeatedly confronted the specters of isolationism and fragmentation. Perhaps it will take the world’s tallest animal to make us look down at ourselves.

Man Tears

The product description made me chuckle: Man tears are too heavy for kleenex.

It’s Okay To Live

A.NThis sentiment is making the rounds a lot in my child-loss groups

As you’ve likely heard, writer/actress/mental health advocate Carrie Fisher died two days ago. Like many people, I was terribly saddened to hear about her passing. I loved Fisher’s brilliant writing and thought she was a hilarious actress. She was only 60 years old.

Yesterday, her mother, actress Debbie Reynolds, passed away. At 84 years old, her death couldn’t be described as completely unexpected, but it is still very sad. As a child I watched Singing in the Rain countless times with my family, and I’ll never forget her sweet voice in Charlotte’s Web.

When the news of Reynold’s death began to spread, many media outlets reported that some of Reynolds’ last words were, “I miss her so much, I want to be with Carrie.” When I heard that, I braced myself because I just knew that social media was about to be inundated with variations of an expression bereaved parents absolutely despise: “If my child died, I would die, too.”

Sure enough, my Facebook feed soon filled with comments like,

“If one of my children died before me, my body wouldn’t be able to take it, either.”

“I would literally die of a broken heart, just like Debbie.”

“How can you not die when your daughter dies before you?”

People. Don’t say this stuff. First, it weirdly romanticizes losing a child into a twisted Romeo and Juliet situation. Second, it’s just so incredibly insulting to parents who have lost children. It immediately puts us on the defensive, as if the reason we ourselves haven’t died is because we didn’t love our children as much, or grieve for them enough.

Third, never presume you know how you would act in one of life’s most horrible circumstances — especially in front of a person who is actually living it. Over the last 7.5 years, I have had countless people say, “I wouldn’t know what to do if my child died. I would die. I don’t know how you survive.” I know this is meant to be a compliment on our strength, but it can feel like another attack on how we’re grieving. Believe me, for most bereaved parents, we aren’t strong, we’re just existing. But we live on, because our children do not. We live on FOR our children.

Bereaved parents often have to work through strong emotions of survivor’s guilt, so when we hear things from armchair grief quarterbacks about how they would grieve “harder” or “better,” it’s difficult to not feel wounded. But it’s okay to live when our children do not. It’s okay for us to find purpose and happiness again. So to those who think they wouldn’t be able to live without their children: you can, and you would. It would be unfathomably painful, but you would survive, just like we are. And that is not something to ever feel guilty about.

© copyright Heather Spohr 2017 | All rights reserved.

This content may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means, without the prior written permission of the author.

A Rickety Bridge

I arrived for my very first psych hospital stay without any books. Without anything, actually, because I was operating on a profound, dangerous sleep deficit and there was nothing going on in my brain that wasn’t destructive.

The doctor at that little hospital started giving me a Prozac capsule every day, this brand-new drug that no one had heard of yet and that would spawn a million newsmagazine pieces in which various experts would wring their hands about what it all meant.

Meantime, one green-and-white capsule at a time, Prozac saved my life.

When I transferred from that first, tiny psych hospital to a much bigger one in Phoenix, I carried my chart with me, and of course I read it. In my first 10 or so days there, the staff had used the phrase “catatonic signs and symptoms” to describe my behavior, which I thought was pretty funny since inside my skull, everything was chaos and mayhem and frantic activity. I would sit curled in a big chair in the day room and never move until someone told me to. I’m not sure I spoke at all. I remember someone washing my hair while I sat in the shower and that seemed OK. My arms were too tired for head scrubbing.

So, to the books: I couldn’t read at first. The brain chaos precluded anything except sitting. When I started to calm down a little, I discovered a bin full of tattered paperbacks. The first thing I read was Silence of the Lambs, which seems to indicate that someone on the staff had a terrible lapse in judgment. The inside of my head was a profoundly violent place and I’d definitely have chosen the hose over the lotion.

Next from that bin, I pulled out a copy of Postcards from the Edge. I didn’t realize who’d written it (I was well enough to read books, but very far from WELL.) and I had no idea it was a semi-autobiographical novel. I believed it to be a memoir and I thought, “Sheesh. She’s almost as fucked up as me,” and that was, somehow, a little comforting. I was very alone with my self-destructive thoughts at that time. Lots of people loved me, but I couldn’t feel that love. Mostly, I thought people who loved me were fools. But Carrie Fisher maybe understood a little, and between that and the Prozac, I had a rickety little bridge that I walked along for awhile until I could make some connections that were a little less tenuous.

For as much as I loved Carrie Fisher as Leia, and as deeply as I have enjoyed some of her subsequent books, there was this one time in a crappy regional psych unit when a book by Carrie Fisher helped save my life.

Go forth and tell your truth because you don’t know who you might save. There’s no shame. Carrie showed us that.

Carrie Fisher died today, December 27, 2016. She drowned in moonlight, strangled by her own bra.

The post A Rickety Bridge appeared first on No Points For Style.

Stay afraid. But do it anyway.

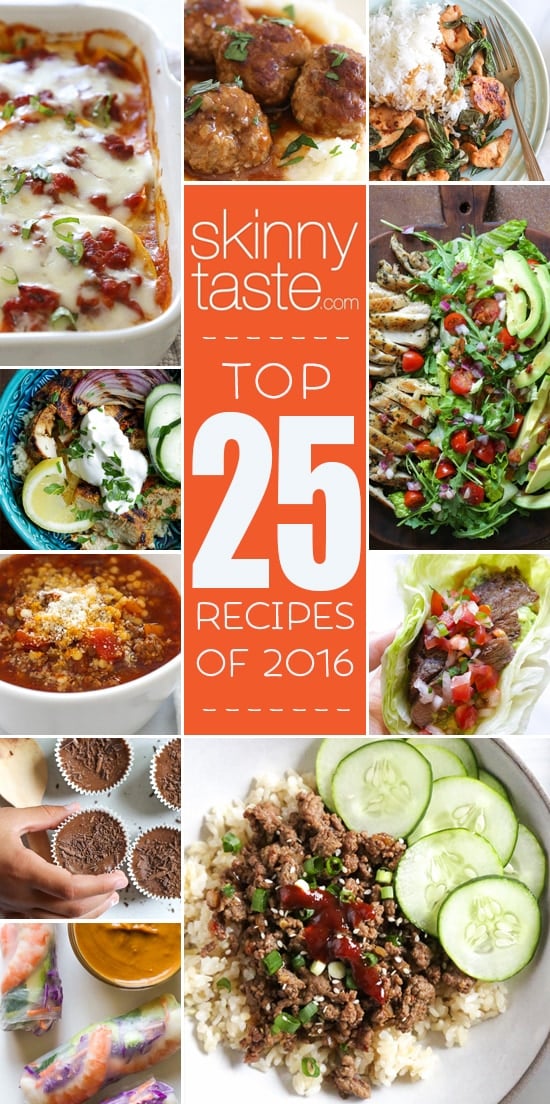

Top 25 Most Popular Skinnytaste Recipes 2016

I’m extremely grateful for all of you who allow me to do what I love every single day! When I started this little food blog back in 2008, I never dreamed it would become a full time career, and that I would have not one, but two New York Times Best Selling Cookbooks! I still look back some days and I’m amazed at where this little hobby has taken me. None of it would be possible without all the Skinnytaste fans trying and sharing my recipes – A HUGE THANK YOU!!!

And now as the year comes to an end, I love looking back through the recipes I posted this past year to see which ones made it to the top 25. Here are the TOP 25 Most Popular Recipes from 2016 as well as links to my most popular posts from previous years. If you are new here, this is always a great place to start!

Top 25 Most Popular Recipes 2015

Top 25 Most Popular Recipes 2014

Top 25 Most Popular Recipes 2013

Top 25 Skinny Recipes 2012

Top 20 Skinnytaste Recipes 2011

Top 20 Skinnytaste Recipes 2010

Top Recipes Posted in 2016

2. Salisbury Steak Meatballs (Instant Pot, Stove Top, Slow Cooker)

3. Beef, Tomato and Acini Di Pepe Soup (Instant Pot, Slow Cooker, Stove)

4. Asian Lettuce Wrap Chicken Chopped Salad

6. Rosemary Chicken Salad with Avocado and Bacon

7. One Skillet Chicken with Bacon and Green Beans

8. Pickle Brined Baked Chicken Tenders

10. Shawarma Spiced Grilled Chicken with Garlic Yogurt

11. Five Ingredient Chocolate Cheesecake Cups

12. Chicken Curry with Coconut Milk

13. Skillet Chicken Cordon Bleu

14. Grilled Shrimp and Vegetable Bowls

17. Grilled Steak Lettuce Tacos

18. Honey Teriyaki Drumsticks (Instant Pot and Skillet)

19. Skillet Chicken in Tomato Chipotle Sauce

20. Noodle-less Butternut Sausage Lasagna

21. Sheetpan Italian Chicken and Veggie Dinner

22. Turkey Meatball Stroganoff (Instant Pot, Slow Cooker, Stove Top)

23. Giant Turkey Meatball Parmesan

24. Shrimp Summer Rolls with Peanut Hoisin Sauce

25. Navy Bean, Bacon and Spinach Soup (Pressure Cooker, Slow Cooker, Stove Top)

Did your favorite recipe make the top 25? Leave a comment here and tell me your favorite!!

The Best Books We Read in 2016

A.NSaving for myself

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

Roadside Picnic is a book about aliens in which no aliens appear. Rather, one character hypothesizes, aliens seemed to have zipped carelessly around Earth and strewed it with trash—like roadside picnickers leaving behind wrappers and empty bottles. The scientists, smugglers, and other profiteers so drawn to these alien objects are but ants crawling through the picnic crumbs. Is this a book that makes you contemplate the smallness of humans? Absolutely. Don’t be fooled by the seemingly breezy title. Roadside Picnic was first written in Russian in 1972, and it is the very loose inspiration for the movie Stalker. An afterward to the 2012 English translation describes Soviet efforts to censor the book, which seems somehow newly relevant in America.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Long Ships by Frans G. Bengtsson

— Sarah Zhang, staff writer

Under the Harrow by Flynn Berry

Flynn Berry’s debut novel Under the Harrow plunges the reader into the mind of a woman who heads to small-town England to hang out with her sister—only to find she’s been murdered. Stunned and sickened, she encamps at a local inn to find the killer. The result is a brisk and chilling psychological study about grief, paranoia, and memory; a smart portrait of a complex sibling relationship; and, more than anything, an effective murder mystery.

The book is also a very good, very quiet work of political art. By now, crime fiction is so littered with the bodies of women that The Kroll Show’s sketch “Dead Girl Town” doesn’t have to explain its joke; in so many stories, a particular gendered tragedy has become a cheap trope. But Under the Harrow vests liveliness, agency, and believable flaws into its murder victim as her sister combs through her memories. More than that, Berry takes some of the big social struggles that have animated the feminist movement and makes them specific and personal, exploring the rippling effects of power imbalances across individual lives. There’s nothing pedantic about the taut, tricky narrative, though. Like solving the whodunit, finding the bigger meaning is simply a matter of paying attention.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Children of the New World by Alexander Weinstein

— Spencer Kornhaber, staff writer

Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America by Jill Leovy

Late in this book, a homicide detective voices the idea that there is no higher or better purpose to policing than responding to crime. Responding, not preventing—this is key. And controversial, right? Isn’t the point of the police, after all, to maintain law and order?

Jill Leovy’s masterful volume, filled with hard-won insights from her years as a crime reporter for the Los Angeles Times, is billed as a book about homicide, but the implications of Leovy’s argument reach much further. That argument is laid out very clearly from the get-go, and its airtight logic is given weight and texture by the tragic stories to which Leovy and her protagonists bear witness. If there are few crimes more serious than murder, and black and brown people can be murdered with few consequences for their killers, they will be killed more often, and their unavenged deaths will rot any chance of faith in their would-be protectors.

Anyone who read David Simon’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (or, yes, watched the TV shows it inspired) will recognize Leovy’s book as a sort of sequel. Like Leovy, Simon wrote his opus after years reporting on his city’s homicide detectives for the local paper. Both books tell rich and lively stories with vivid protagonists fighting enormous pain. But Ghettoside builds more forcefully to its conclusions, while Homicide tends to leave readers to draw their own. In some ways, Leovy has completed the book that Simon began. No other book has animated my thoughts more this year.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor

— Matt Thompson, deputy editor

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union by Michael Chabon

This has been a year of what if? in American politics. What if Trump wins? What if, when he wins, he puts into place the policies he has advocated, such as religion-based restrictions on Muslim immigration? What if online trolls feel more empowered to spew their anti-black, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic, anti-everything rhetoric—or actually gain real power?

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union is a book for a what if time. It’s set in a world in which the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel turned out differently: Instead of settling in the Middle East, Jewish refugees moved en masse to Alaska. Inevitably, the Jews are asked to leave—and their worst fears are realized. But these bad times are also morally ambiguous: The good guys are never fully good guys, the bad guys never fully bad. Ultimately, the Jews of Sitka, Alaska, learn that they are helpless in the face of what if coming true, that there will always be more bad times. The goal isn’t to remake the world, Chabon seems to argue, but, rather, to survive it. And his greatest insight is that it’s possible to find humor in catastrophe—speaking Yiddish, along with a sip of slivovitz, makes the end of the world much easier to take.

Book I'm hoping to read before 2017 arrives: How to Be Both by Ali Smith

— Emma Green, staff writer

Loren Eiseley: Collected Essays on Evolution, Nature, and the Cosmos

A mentor of mine gave me this two-volume set as a gift. It was a handsome Library of America edition, black and glossy, with an early hominid skull on one side and an exploding star on the other. “No one has ever managed to make the pursuit of knowledge feel more soulful or more immediate than Loren Eiseley,” went the blurb. Intrigued, I dipped into the first essay. It was a small thing about a visit to a local canyon, but the prose was astonishing. In addition to his work as an essayist, Eiseley was an accomplished poet. He had a remarkable ability to slip back and forth between the immediacy of a single moment and the span of geological time. Sometimes he did this all in one graceful sentence. A trained paleontologist, he seemed to have the whole of the fossil record at his ready command. And he had an eye to the cosmic. “Somewhere out in that waste of crushed ice and reflected stars the whole of space might be locked in a silvery winter of dispersed radiation,” goes one line. Eiseley’s style was clearly an influence on other writers I have come to admire, John McPhee in particular. And yet somehow his work has become obscure in recent years—or, at least, obscure to me. I have done my best not to rush through his essays. Instead, I’ve been savoring them, reading one every morning, or just before bed, the way you might read a devotional. More than the best book I read, the collection was the best gift I received all year.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell

— Ross Andersen, senior editor

The Sound of Things Falling by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

In his novel The Sound of Things Falling, Juan Gabriel Vásquez leaves the reader in the hands of a convalescent narrator named Antonio, who has been traumatized by the violence spurred by the Colombian drug war. Having survived a shooting that claimed the life of his friend, Antonio is now compulsively preoccupied with the day the incident happened.

Unlike his countryman Gabriel García Márquez, Vásquez does not employ magic to tell a story; he uses phantom pain. And yet, there remains something of an occult tone to Vásquez’s Colombia—the abandoned spoils of Pablo Escobar’s empire, the oppressive humidity of the deep jungle, the dim, cobbled streets on the fringes of Bogotá—that is reminiscent of a Thomas Cole painting. It’s amid this dense landscape that Antonio engages in the “damaging exercise of remembering.”

I sought out Vasquéz because I wanted respite from real-life stories of moral failings, the killings of unarmed men, and power-hungry demagogues. Though I found all three in The Sound of Things Falling, I also took solace from his treatment of the memory of these things—not as a salve to tragedy, but as a necessary way of framing one’s place in history.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes on Race and Resegregation by Jeff Chang

— Jordan T. Jones, associate editor

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

In a year when it sometimes felt like the world was coming apart, the gifted surgeon and scholar Paul Kalanithi's memoir of living and dying, When Breath Becomes Air, helped me to hold the pieces all together. Though it has terrible loss at its core—Kalanithi wrote it as he faced terminal lung cancer in his mid-30s—its fundamental message is that we must live while we can. To write a book and to have a child when death hangs over you—these are acts of love, acts that outlast our own time on this earth.

At the memoir’s end, Kalanithi’s wife Lucy offers up an epilogue that is, to me, perfect. Full of love and sadness, she describes their final hours together as a family, of the days following his death, and of her life since. “For much of his life,” she writes, “Paul wondered about death—and whether he could face it with integrity. In the end, the answer was yes.” What I learned, in reading the book, is what doing so looks like: It looks a lot like living.

Book I’m hoping to (re-)read before 2017 arrives: Stones From the River by Ursula Hegi

— Rebecca J. Rosen, senior editor

The Wonder by Emma Donoghue

The Wonder is told from the perspective of Lib, a brisk, no-nonsense, and thoroughly rational nurse in Victorian England who travels to Ireland to consider a baffling case: an 11-year-old girl who refuses to eat but apparently has been surviving on nothing but sunlight and faith. A faction of people in the town believe the girl, Anna, is proof of a genuine miracle unfolding before their eyes. Lib is naturally skeptical. “Had the doctor’s gullibility spread like a fever among these important men?" she wonders.

Slowly, and with remarkable skill, Donoghue builds her story before revealing its innumerable layers. The simple question of whether Anna represents a miracle or a fraud is complicated by the larger conflicts manifesting around her: battles between science and religion, duty and instinct, doubt and faith, men and women. Unexpectedly, The Wonder leads toward an ending that’s both suspenseful and moving, where all the pieces of the novel fall sharply into place. It’s perhaps a stranger work than Donoghue’s 2010 hit Room, and Lib is a pricklier and less endearing narrator than four-year-old Jack. But The Wonder is clear-eyed in its treatment of centuries-old societal conventions and subtle in its analysis, all while making its point that none of this matters when the life of a child is at stake.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Lesser Bohemians by Eimear McBride

— Sophie Gilbert, staff writer

Death’s End by Liu Cixin

The secret fact about science fiction is that most of its substance comes not from the future, but from the present. The genre has served as one of the greatest vehicles for social and political allegory over the past century, and through our culture’s corpus of sci-fi can be seen our sense of what’s possible and who matters.

It follows, then, that reading science fiction from beyond our borders might grant insights. Nowhere is this more evident than in America’s fumbling, frosty relationship with China. English translations of Chinese science fiction are hard to come by, but luckily the last book in perhaps its greatest genre trilogy is now available in English.

Liu Cixin’s Death’s End is masterful, picking up complex narratives from the two previous books in his Three-Body Problem trilogy. It’s got all of the complex realistic engineering of “hard sci-fi” writing and the elegance, weirdness, and metaphysics of space operas, while remaining at its heart a character-driven story about duty and time. Most notably, it’s amazing to fathom a future in which China and its cultural values take the center stage as opposed to American ones. The final book in Liu’s trilogy is a must-read, and Hugo-award-winning author Ken Liu steps in to provide an excellent translation.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Swing Time by Zadie Smith

— Vann Newkirk, staff writer

Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972 by Alejandra Pizarnik

In 2015, I heard the novelist Valeria Luiselli read from Alejandra Pizarnik’s diaries at a Music & Literature event and was blown away by the thoughtful interiority—by turns delicate and brutal—of this Argentine poet, who died of an intentional drug overdose at the age of 36. The poems in this new collection, translated by Yvette Siegert and published earlier this year, show a preoccupation with the space—not so large, but also interminably vast—between the workings of the mind and those of the natural world. “Even if I say sun or moon or star, this is still about things that happen to me,” she writes.

Pizarnik employs vivid, fragmented language, often in almost wearying repetition, to explore the shape of solitude and its frequent bedmate, sanity. Hues gain agency (“the colors scratch against the silence and make decaying animals”), while from page to page, little figures pop up—sometimes as paper dolls (cut “out of green and red and sky-blue paper”), sometimes as flesh-and-blood girls. Pizarnik would seem to be posing the question: Is true expression to be found in the made-up or in the real, in the messy fog of introspection or in the clear outlines of the observable world? By threading an erratic but lively heartbeat through her recursive lines, she achieves, beautifully, what she once called the “precise expression of a profuse state of confusion.”

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: A Floating Chinaman: Fantasy and Failure Across the Pacific by Hua Hsu

— Jane Yong Kim, senior editor

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

Zadie Smith is sometimes referred to as a “comic novelist.” That’s because her writing can be funny, but it’s also, I think, because she has the kind of deftness with time so often associated with comedians. She constructs sentences that weave and wind and then end not just with periods, but with punchlines. She exploits the anticipatory power of the awkward pause. Her fiction, often, works as a whirligig: She’ll plant a name or an insight or a joke, and only hundreds of pages later—whir, whir, whirl—will it fully make its sense.

Swing Time (the title refers variously to jazz and Fred Astaire and the arcing movements of history) is a novel about dancing, and it's hard to imagine a more fitting union of author and subject; this is a book that has been choreographed as much as written. In it, a series of couples move, together, through time: the unnamed narrator and her childhood best friend, joined, in the 1980s, by their shared love of the stage; the narrator and her politically ambitious mother; the narrator and her eventual boss, a Madonna-esque pop star who is building a school in an unspecified country in West Africa; the narrator and London; London and New York; wealth and poverty. The two, all the twos, pair and part and whir and whirl to Smith’s distinctive music.

Swing Time is, I should warn you, a melancholy novel; rhythm, it acknowledges, comes not just from exuberance, but also from constraint. I loved it despite, and really because of, that: Swing Time is Smith, the novelist and the lyricist, the comic and the critic—the creator of worlds and the keen observer of the one we all share—dancing, finally, with herself.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

— Megan Garber, staff writer

You’ll Grow Out of It by Jessi Klein

Okay, so this book is not exactly belles lettres. I picked it up while I was working on a difficult, serious story earlier this year, and I needed something to do in the evenings that wasn’t biting my nails into a glass of wine, then drinking said wine. I was also going through Amy Schumer withdrawal, and Jessi Klein is the head writer on her Comedy Central show. You’ll Grow Out of It happens to fall into my favorite genre (memoir) by my favorite type of person (funny women). It also contains my favorite description, to date, of a “type” of romantic partner: “Anything that suggests someone who has just barely evolved past having paws gets my blood flowing.” Sure, it may be a beach read for women who don’t get to the beach much. But Klein did have me laughing to myself on the Metro, my personal bar for memoir greatness. Books are supposed to challenge you and expand your worldview, but this one is more like a reassuring hug after a hard day—for me perhaps especially, since it’s about a risk-averse writer who goes through a lot and makes it in the end.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Strangers Drowning by Larissa MacFarquhar

— Olga Khazan, staff writer

The Sun Is Also a Star by Nicola Yoon

This is a story of a mayfly love, which is born and lives a full live in only a day. In that way it’s like a YA version of Before Sunrise, except that Yoon’s tale has higher stakes (and characters who are more earnest, less pretentious). When the 17-year-old Natasha meets Daniel on the streets of New York City, she’s on a mission to single-handedly stop her family from being deported back to Jamaica that night.

Daniel doesn’t know that, and he constructs a narrative of fate around their meeting. He’s a poet, and he believes that he and Natasha are meant to be. She, a scientist at heart, is more skeptical, preferring to describe things in terms of observable facts, and what can be proven. So Daniel consults some research and decides he will get her to fall in love with him scientifically. It starts to work—“Observable fact: He is pretty hot with his hair down,” she notes at one point.

As they move through the city, Natasha in pursuit of her mission, Daniel in pursuit of his, an omniscient narrator occasionally pulls back from the story. These brief interludes show what encountering Natasha and Daniel means for the secondary characters that populate their day, sometimes taking detours into cultural history, or science—why many black hair care stores are owned by Koreans, or how animals evolved eyes. The effect is to crack open the small story of a daylong love until it’s large enough to contain the whole universe.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee

— Julie Beck, senior associate editor

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

If the quantity of time spent weeping while reading a book is a good indicator of its quality, then Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is top notch. The novel follows four men, all friends, from college to the end of their lives, alternating the present day with textured flashbacks. This is no light coming-of-age story. One of the men has a grisly history of abuse, another battles drug addiction, another is haunted by memories of his estranged family. Garth Greenwell, writing for The Atlantic in 2015, called A Little Life “the great gay novel,” and there is certainly an argument to be made that the book is an in-depth examination of the emotions and ambitions of a group of gay men (written by a woman, no less). But A Little Life is also a book about friendships and how they morph and grow over time, by turns dragging their participants down and holding them up. As I watched these characters dealing with missteps and tragedies, and striving to succeed in life, I was desperate for them to end up safe and happy. This being a novel, nothing is that easy. Read it and weep.

Book I'm hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

— Alana Semuels, staff writer

Known and Strange Things by Teju Cole

In “Blind Spot,” the epilogue to his remarkable new collection of essays, Teju Cole writes of Virginia Woolf’s diary: “... the pages held a radiance … because of Woolf’s prose, the intensity of her attention to life, and the epiphanic moments that intermittently illuminated the gloom. I went to sleep in the glare of her words.” For me, reading Known and Strange Things—compiled from pieces Cole has penned for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and elsewhere—produced a similar kind of afterglow. On days when I was frantically tab-switching or scrolling through the abyss of Twitter, Cole’s singular curiosity and eagerness to open himself up to experience was a powerful reminder for me to hit pause.

In this collection, as in his novels Open City and Every Day Is for the Thief, Cole becomes a modern-day topical flâneur, drifting seamlessly from art and photography to music and geopolitics. Three sections, broadly classified as “Reading Things,” “Seeing Things,” and “Being There,” allow Cole to map out an array of reflections, criticism, and unfinished ideas. “In Place of Thought” imagines, with a smirk, an alternate dictionary (“AFRICA. A country. REGGAE. Sadly just one album exists in the genre.”). “Home Strange Home” expresses his uneasy re-acclimation to his native Nigeria. “Death in the Browser Tab” speaks to the realities of police brutality against black men in an age of instant circulation. You’ll want to take your time reading this—it’s a heady mix of wit, nostalgia, pathos, and a genuine desire to untangle the world, or at the least, to bask in its unending riddles.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti

— Arnav Adhikari, editorial fellow

So Sad Today by Melissa Broder

For the past year, I’ve seen one particular kind of story a lot on my Instagram and Facebook feeds. It goes something like this: “Last [month/year/decade/etc.] I was struggling with [X problem], and it was so bad/the worst/I was sad. But through [Y solution] I’ve since gotten over it and now I’m in a much better place.” Cue the likes.

In a culture that prizes self-promotion and oversharing, these kinds of stories aren’t surprising. But my impulse to celebrate these personal victories is always halted by another thought: Why doesn’t anyone talk about their problems anymore while they’re ongoing? Our virtual friend climate tends to celebrate wins, dismissing any show of vulnerability as undesirable and embarrassing. The implication horrifies me a little: Only tell me about stuff once it’s been resolved. And worse, this kind of self-presentation and celebratory reflex threatens to breed a lazy form of friendship—ones that are never messy or brutal.

This is why Melissa Broder’s collection of personal essays is such a breath of fresh air: It’s both really sad and, in its own way, a zeitgeist of our time. The book grew out of a Twitter account, @SoSadToday, that Broder started in 2012; her tweets were full of despair, but also very funny. My favorite essay in the book is a series of one-line love stories (Border’s own), all so full of promise and all unresolved. To my surprise, my second favorite piece details a lurid sext affair. Shame is such a hard emotion for me, and Broder’s ability to dissect hers with humor is a feat. She doesn’t talk her way out of her sadness, or present it as some kind of redeeming, soulful experience. The fact that she manages to do this without being nihilistic is, in itself, a kind of writing-my-wrongs redemption.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Vegetarian by Han Kang

— Bourree Lam, associate editor

Underground Airlines by Ben H. Winters

The resonance in titles between this book and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad blurs the difference in styles: Railroad is more ambitiously literary, while Ben Winters’s Airlines is more of a genre work, with the tone of a hard-boiled detective novel overlaid on a dystopian, re-imagined future. In Philip K. Dick’s famous The Man in the High Castle, the re-imagined future involves a German-Japanese victory in World War II. In Airlines, it is the non-occurrence of the U.S. Civil War, due to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln just before he takes office. This leaves parts of the old south—the “Hard Four” states of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and a combined state of Carolina—still basing their economies on legalized black slavery, which has made those states a center of low-cost manufacturing but has turned the United States into an apartheid-style pariah for the rest of the world. (When the U.S. is forced out of the United Nations in 1973, the British ambassador says, “Good riddance.”)

But the title similarity, presumably unintended, is appropriate in indicating that the books offer complementary ways of re-examining America’s original sin. Airlines is full of countless ingenious small touches that combine the recognizable America of 2016 with Winters’s imagined future: C-SPAN is around, but it’s showing hearings about slave-based industries. I end up judging books on how long their imagery or worldview stays with me. I expect I’ll be thinking about Airlines, along with Railroad, for a while.

Book I’m hoping to (re-)read before 2017 arrives: The Revolt of the Masses by José Ortega y Gasset

— James Fallows, national correspondent

The Mothers by Brit Bennett

Mothers are omnipresent in the small Southern California town where Brit Bennett’s 2016 novel takes place: gossipy church mothers who don’t “notice the sourness of an unripe secret”; women who've had children only to abandon them in one way or another; others who ache to wear the badge of motherhood.

This is the backdrop against which the novel unfolds, at a breakneck pace: a suicide, an unplanned pregnancy, a romance in free-fall. The story follows three teenagers into adulthood: Nadia is a grieving 17-year-old who has an abortion the summer after her mother commits suicide; she is at once haunted by her unborn child and the question of her own worth as a daughter. Aubrey, Nadia’s best friend, watches as her mother chooses an abusive man over her. Then there’s Luke, a former football star, who’s the recipient of near-constant mothering from every other character in the book.

The novel’s true gems, though, are The Mothers, a group of older churchwomen that act as a collective narrator, and whose wisdom will resonate with women of any era: “We were girls once, which is to say, we have all loved an ain’t-shit man… No shame in loving an ain’t-shit man as long as you get it out of your system good and early.”

I enjoyed this book because all of the main characters were hard to like, and Bennett’s beautiful passages almost made me forget that. Everyone ends up almost exactly as they were when the story began—bruised but not having really made amends. Mothering, in this novel, is for some a laceration, for others a salve, and for Nadia and Aubrey especially, a little of both.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: I’m Judging You by Luvvie Ajayi

— Adrienne Green, associate editor

Negroland by Margo Jefferson

Last year, I listed Margo Jefferson’s Negroland as the book I wanted to read before 2016 rolled around; this year I finally got to it. Jefferson’s memoir, structured around her coming-of-age as a member of Chicago’s mid-century black bourgeoisie, is a brilliant work of cultural history and criticism delivered in stirring, lucid prose. Defining “Negroland,” on the first page, as “a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty,” Jefferson sets out to probe its mores and plumb its historical depths. “I’m a chronicler of Negroland,” she writes, “a participant-observer, an elegist, dissenter and admirer; sometime expatriate, ongoing interlocutor.” She looks within and without, blending introspection with her well-honed gifts of observation and assessment (Jefferson won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for criticism) as she surveys the landscape.

It almost goes without saying that questions of race, gender, and class abound in this book, which uses present-tense narrative to create a poignant immediacy. Jefferson’s wise conclusion is that “the question isn’t ‘Which matters most?,’ it’s ‘How does each matter?’” There’s a reason the New York Times’s Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris call her “The Oracle.”

Book I'm hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Frantumaglia by Elena Ferrante

— Amy Weiss-Meyer, assistant editor

An Untamed State by Roxane Gay

A woman is kidnapped, held against her will for days, and repeatedly raped. It's a terrible story made familiar by the likes of Law & Order: SVU. But Roxane Gay doesn't let her readers fall into step with the rhythms of an oversimplified narrative. Gay's debut novel is a lightning bolt to jolt even those who are the most desensitized to sexual violence.

Mireille Duval Jameson is visiting her parents in Haiti, accompanied by her husband and their son Cristophe, when they are ambushed. Mireille is grabbed from their car and held for ransom by a group of men. During her 13-day-long captivity, she suffers rape after rape, in addition to verbal and physical abuse, and extremely poor living conditions. But Gay won’t let you look away: Like Mireille, you must stay entrapped.

Instead of ending the novel when Mireille is freed, Gay pushes forward into the less explored territory of life after horrific trauma. Like Room, by Emma Donoghue, the story of trying to pick up the pieces is at least as important as how they shattered. For Mireille, that means making enough peace with the pain and shame she feels in her body to once again hold and care for her young son.

An Untamed State is a story of an extraordinary ordeal and everyday survival, as Mireille, like all of us, tries to make it through another day.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: My Notorious Life: A Novel by Kate Manning

— Caitlin Frazier, senior editor

Dispatches From Dystopia: Histories of Places Not Yet Forgotten by Kate Brown

“In this volume, I describe what happens when a researcher snaps shut her laptop, picks up a bag, and ... boards a plane for a destination of which few have heard.” So begins Kate Brown’s Dispatches From Dystopia, a collection of seven essays that takes readers to out-of-the-way destinations to explore questions of identity and transnationalism. In one, Brown visits the basement of an old Seattle

hotel to archive the possessions left by Japanese Americans forced into internment camps during World War II; in another, she considers a landscape in the Chernobyl Zone, desolated by nuclear explosion. In my favorite essay, “Gridded Lives: Why Kazakhstan and Montana Are Nearly the Same Place,” she compares city planning in a former Soviet deportation zone and in the American Midwest.

Like Brown’s other books, Dispatches From Dystopia is written in the first-person and interspersed with anecdotal asides and photographs. Her sources come alive: Take Yuri and Sasha, the men in Uman, Ukraine, who disguise her as a policeman so that she can enter the city's synagogue during a Hasidic pilgrimage at Rosh Hashanah, when women are prohibited. (Brown reflects on this act later in the chapter and admits it was an insensitive intrusion). If this historiographical method is unusual, even controversial, it’s also precisely why the book is appealing: It’s self-conscious and empathic, while still being meticulously researched and documented—which, in the current moment, I would argue, is exactly how a discussion of homelands and adopted lands and identities should be.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

— Jake Pelini, editorial fellow

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing is a story told through a family tree that branches out across centuries and countries. The two matriarchs, Esi and Effia, are half-sisters separated at birth in the 18th-century Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). As adults, they nearly cross paths at the Cape Coast Castle, an outpost that was integral to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. One sister is forced to marry a British official, while the other is sold into slavery and shipped to America.

Over the next 250 years, Gyasi follows the women’s descendants on their intersecting journeys across the United States and Ghana. Some are players in chapters of American history we know well, or thought we did. Others introduce us to less familiar stories in West Africa, including the terrible reality of African complicity in the slave trade.

Homegoing tells these diasporic stories inventively and beautifully: Each chapter is dedicated to a new character and a new period, but it’s always clear how the family bloodline runs through each. With this, her first novel, Gyasi traces the trauma, memories, and love passed between generations by those forced to separate and migrate.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

— Anna Diamond, editorial fellow

The Hike by Drew Magary

Drew Magary’s latest novel is a modern fairy tale, but it’s also a horror story that you read with the lights on. The Hike follows Ben, a suburban family man, as his short walk in the woods is interrupted by a killer in a Rottweiler mask. He escapes down but finds himself lost in a surreal world populated by talking crabs and demons manifested from his childhood imagination. From here, there’s no escape for Ben (or, for that matter, for the reader). He faces a slew of obstacles, which strike relentlessly, chapter after chapter, slowly forcing him to adapt to his brutal new circumstances. I kept stopping to ask “Where was this going?” The ultimate answer to that question still rattles me. Every plot twist in this story is there for a reason, and in the end, that’s where the real horror lies.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Nix by Nathan Hill

— Jason Goldstein, senior developer

On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Before attending a recent reading of Zadie Smith’s newest novel, Swing Time, I hustled to finish her 2005 book On Beauty. When the earlier novel came up during the Q&A portion of the event, Smith explained that writing is a way for her to sate her curiosity by testing out different experiences—in the case of On Beauty, that of having an academic for a parent.

Set just outside of Boston, the novel follows two feuding families headed by fathers who are professors at the same elite university and who, in many ways, act as foils for each other. Howard Belsey is a humorless white Englishman and anti-aesthete, struggling to write an epic renunciation of Rembrandt. Monty Kipps is a fiery visiting scholar of Caribbean descent and the author of a successful book praising the same artist.

As the novel progresses, the families’ lives become ever more intertwined, with burgeoning friendships, spats, deaths, and affairs. Smith navigates these complicated twists and turns with grace, sliding into the minds of her characters with such ease you’d never know these were lives she hadn’t lived. (Take the strong-willed Kiki Simmonds Belsey who, learning of her husband Howard’s infidelity, “found she could muster contempt for even his most neutral physical characteristics.”)

As always with Smith, the book is peppered with humor both light and dark. “Writing On Beauty, it dawned on me,” she joked at the reading, “there’s lots of ways to have an unhappy childhood.”

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

— Stephanie Hayes, assistant editor

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

Albert Camus, when asked to summarize The Stranger, said, “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother's funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” Echoes of this earlier work are apparent in Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk, an unsettling, poetic novel that was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize this year. Both works explore the relationship between mothers and children; existential crises; and societal expectations of remorse and empathy. Both reimagine the beach—usually a place of escapism—as a stagnant purgatory.

Hot Milk’s protagonist, Sofia, is a twentysomething graduate-school dropout who accompanies her mother, Rose, to the southern coast of Spain in search of a cure for Rose’s nebulous (and, in Sofia’s view, psychosomatic) paralysis. Their relationship is toxic and codependent: Sofia’s disrespectful attitude and doubts about her mother’s illness both inspires and feeds off Rose’s narcissism and demanding nature.

The doctor Rose has come to see, Gómez, takes Rose off her many pills, and sends Sofia—who has acted as her mother’s “waitress” for years—away to the beach. Removed from her mother, she is forced to consider that Rose is not a burden, but rather a crutch for her own immobility. Gómez later takes a medical interest in Sofia, explaining that her case is more compelling than her mother’s. “What is wrong with you?” he asks. Sitting on the blinding beach, Sofia makes abortive attempts to articulate this question, to differentiate between the symptoms and the disease. Yet her curiosity is detached, academic—and the question of whether her ennui is the result of a disorder, or merely an element of the human condition, remains unanswered. “Is it easier to surrender to death than to life?” she asks. It’s implied that mother and daughter—joined like an ouroboros—must each choose one.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, edited by Karen V. Kukil

— Isabel Henderson, editorial fellow

The Waves by Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is the kind of book that demands to be written about, even as it resists simple encapsulation. It follows six school friends, Neville, Bernard, Louis, Jinny, Susan, and Rhoda, from childhood through old age, as they shape and define and revise their identities. Over time and in turn they are lonely, ambitious, uncertain, regretful, and impatient; they deal with love and poetry and parenthood and dreams they never quite achieved. Each in their own way, they come to love another classmate, Percival; later, each in their own way, they grieve his death.

What stands out the most about The Waves, though—and what might make it hardest to love, and hardest to write about—is its style, a radical experiment in character and narration. The novel is written in a series of interior monologues, in which the characters aren’t differentiated by voice so much as by their various ways of relating to the world—through nature, in Susan’s case, or through a mercurial stream of human observations, in Bernard’s. Rhoda and Neville, meanwhile, suffer from constant self-doubt. You get the sense, reading, that this is a record of thoughts the characters themselves are barely aware that they have. Maybe you even recognize, as I did, things that you too have felt, and would express, if only you had the words.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: The Story of a New Name by Elena Ferrante

— Rosa Inocencio Smith, assistant editor

Time Travel by James Gleick

The idea of time travel has had a weirdly salient presence in American culture this year. A surreal presidential race, which prompted many observers to leap through time in search of context, led some people to fictional alternate realities (see: Biff Tannen, Back to the Future) and transported others to moments from the actual past (see: Michiko Kakutani’s review of Volker Ullrich’s work). Many of those dispirited by Donald Trump’s victory have expressed a desire to catapult forward in time—Rip Van Winkle style—by, say, four or eight years. All the while, 2016 has seemed to stretch on for eons, longer than any single year in recent memory. Was election day really only six weeks ago?

Given all this, it seems fated that 2016 was also the year that produced James Gleick’s extraordinary book, Time Travel, which explores the scientific, technological, and literary intersection of a surprisingly modern concept. “Somehow,” Gleick marvels, “humanity got by for thousands of years without asking, What if I could travel into the future? What would the world be like? What if I could travel into the past—could I change history?” Gleick examines why the concept emerged when it did—officially, in 1895, with the publication of H.G. Wells's The Time Machine—and how the idea of time travel has reverberated through culture ever since.

Much of Time Travel focuses on technology. It’s no coincidence, Gleick argues, that time-travel narratives flourished in the early 20th century, at the dawn of a new age in transportation and communication, when layers of time became visible in sometimes jarring ways. He also investigates the nature of time itself, examining through both scientific and literary texts the idea that the past and the future can be physical places—a notion essential for the concept of time travel.

Ultimately, Time Travel centers around a single question: Why do we need time travel? To find the answer, Gleick brilliantly stitches together moments at seemingly disparate points in history: He goes from explaining the plot of an episode of Doctor Who in one sentence to revisiting the invention of the Cinématographe in 1890s France the next. But what could be a dizzying narrative is deftly handled. And that’s because Gleick’s adventure in time travel is, in the end, not about distinctions between past and future, but a love letter to “the unending now.”

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: Seveneves by Neal Stephenson

— Adrienne LaFrance, staff writer

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit

This collection of essays begins with perhaps Solnit’s most famous one, first published in 2008, of the same name. In it, Solnit recounts the night a man described to her in length a new book he'd heard about—"with that smug look I know so well in a man holding worth, eyes fixed on the fuzzy far horizon of his own authority"—only to be informed, when he was finally done, that Solnit had written it. The essay gave rise to the term "mansplaining," and the encounter therein would serve as a dictionary-worthy example of the act, which has been around since, I assume, the dawn of time. Solnit puts mansplaining on a long spectrum of male behavior that women have endured for centuries, an "archipelago of arrogance" dominated by a deep-rooted disregard for women's "right to speak, to have ideas, to be acknowledged to be in possession of facts and truths, to have value, to be a human being." She explores this spectrum in the remaining, thoroughly reported essays, from the street harassment of strangers, to the violent rapes of young girls, to the deaths of wives at the hands of their husbands. So, warning: This could be demoralizing read. But it's an important and necessary reminder of the ways in which women on this planet share a singular experience that, at its core, can transcend geography, ethnicity, and ideology. Men explain things to women all the time, everywhere. That knowledge creates a sense of fellowship that makes hearing these stories—which should be told, and often—a little bit more bearable.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation by Rebecca Traister

— Marina Koren, senior associate editor

Private Citizens by Tony Tulathimutte

Tony Tulathimutte distances himself from the thrown-about claim that what he’s written is the “voice of a generation” millennial novel. As any reasonable person would. That sounds like the worst possible thing. Private Citizens is more like a classically good novel that’s unique for being set in the immediate now and for so skillfully showing the best and worst of young adulthood. A dryly self-conscious walk through the heads of a cast of mostly miserable young Bay-Area friends being mostly miserable, often hilariously, and somehow hopefully.

Book I’m hoping to read before 2017 arrives: How to Be a Person in the World by Heather Havrilesky

— James Hamblin, senior editor

#926: How to deal with a well-meaning but controlling mother-in-law?

Hi,

Me and my husband have been together for a bit less than seven years now. I have never really liked my mother-in-law and my husband doesn’t really like her company either. Also, everyone who has met her and I’ve talked about this agrees with me. She is exhausting to be around: she talks literally all the time about things only she is interested in. It’s also impossible to concentrate on anything if she is around: she will come and interrupt us with something else. I can spend about a day in her presence, after which I will be totally exhausted and sleep for a day.

What bothers me even more is that she wants to control and micromanage everything in our life. For example, me and my husband are attending the pre-Christmas party of the company that I work for, and my mother-in-law obsesses about it. She has bought my husband a suit (he could afford it himself) and she calls me often to say that I need to put my hair up for the occasion. I don’t really care and don’t know how to do it but she keeps pushing. She also gives us a lot of cleaning tips and buys a lot of cleaning utensils (that are not the ones I prefer, for ethical reasons) for us. She also always starts to clean our apartment when she visits. These are just examples, she has an opinion on every little thing in our lives.

The problem is that she never listens to anything we say. Especially for me, it is hard to confront her because she does get hurt easily. And I know she means well by everything she does. But even when we talk about these things quite straight (and my husband even harshly) to her, it doesn’t change her behavior. It will maybe work for a few weeks but then she will continue the controlling behavior.

Another problem is that because it’s not pleasant to be around her, we spend a lot more time with my mother. Even though both mothers live equally far away, we visit my mother a lot more often. It just isn’t as big an investment of energy from us to visit my mother. My husband agrees with me on this but I still feel guilty about it. My mother-in-law isn’t evil, I just personally don’t enjoy being in contact with her.

How can I reach a more peaceful existence with my mother-in-law? Should I feel guilty about visiting my mum more often? Is it ever possible to get through to her that we want to make our own decisions?

Thanks in advance,

An introvert who isn’t a native English speaker

Hello Introvert!

Should I feel guilty about visiting my mum more often?

Nope! It’s okay to like your mom better and to like spending time with her more than you do with your mother-in-law. The extra piece of good news is your husband isn’t dragging you or pressuring you to spend more time with your mother-in-law. This is a good problem to have, so do what you can to stop feeling guilty!

Is it ever possible to get through to her that we want to make our own decisions?

Maybe someday, but probably not in a “we talk about it and work things out like rational adults” way that you hope, and probably not anytime soon.

How can I reach a more peaceful existence with my mother-in-law?

You can change how you interact with her and hope that she will adapt over time. Here are some processes that might work.

Schedule a weekly check-in with her. Your husband should set up a short weekly phone call (or Skype session or what have you) with his mom at the same time every week. He should be the one to initiate the call – “I’ll call you on Sunday at our usual time.” If he has to miss it for some reason, or will run late, he should let her know in advance with a text. “Won’t be around at the usual time, can we do it at X time instead?” You can hop on the calls (or not) for a few minutes at the end if you want.

Why this works:

- It re-focuses communication between mother and son, makes it less your problem.

- Routines are reassuring. Knowing they’ll talk at a set time each week might relieve some of his mom’s anxiety about how often they are in contact and will relieve his and your anxiety about how often you have to deal with her.

- It gives an opportunity to create positive regular communication patterns that might replace old patterns.

How to make it work:

- Your husband announce the plan as a positive way to keep in touch, not as a negative or strategic response to her behavior. “Mom, how would it be if we talked every Sunday afternoon around 4 pm? I’d love to be able to catch up with you more consistently.“

- If she balks, do it anyway. “I understand, we don’t always know our plans in advance, but I’ll try to call you then anyway. If you can’t talk, we’ll just try again next week or find a time that does work!“

- If she tends to call or text a lot every day or during the week, over time you can both redirect everything to that weekly call. Don’t leave communications from her hanging completely, but be perfunctory in your answers and save discussions for the weekly call. “Sorry I couldn’t pick up, I was driving. Let’s talk about it Sunday!” “This isn’t a good time, but I’ll catch up with you Sunday.” “Can’t talk now, but when (Husband) talks to you on Sunday have him give me the details!“

- Husband should schedule some kind of relaxing ritual or a treat for himself after the weekly call with mom, like, now it’s time to take the dog for a run or play a favorite video game or read. Something to look forward to and defuse tension.

- She will not like this in the short-term, but if you both redirect her (i.e. enforce the boundaries) consistently, she’ll very likely adjust to the routine over the long-term.

“Thanks for the advice!” Unwanted advice (like the constant stressing about your hair) is intrusive and annoying. One of the fastest ways to get past something like that is to say “Thanks! I’ll think about it!” and then change the subject to something else. You will think about it before styling your hair however you want and possibly cursing her under your breath, so it’s not a lie to say you will!

You’re a reasonable person, so your instinct is to say “Hey, I appreciate that the hair advice is kindly-meant, but it’s not really your business how I wear it and your constant references to it are stressing me out.” A reasonable person would hear that and think, wow, I probably did overstep the line. I’ll apologize and I’ll make more of an effort to stop doing that.

With your mother-in-law, asking her (reasonably) to step off probably won’t work, so the best strategy for you is the one of least resistance. If she’s expecting an argument (and therefore a chance to remind you of how she perceives her role in your life and a reason to feel aggrieved and righteous), saying “Thanks, I’ll think about it! How is your holiday baking coming?” stops her in her tracks.

This works for all kinds of opinions. See also:

- “Okay.”

- “Maybe!”

- “You might be right about that.”

- “Interesting. We’ll think about it.”

- “You’ve given us a lot of food for thought.”

You want to make it very boring for her to heap advice or opinions on you, in other words.

Return or donate unwanted gifts. Your husband should ask her once not to buy you stuff you don’t want (like cleaning supplies), and then let it drop. If she keeps doing it, donate the stuff or return it to the store without guilt or comment. If she notices and/or asks you where it is, be honest. “We didn’t have space to store it/We can’t use that kind/We already have our favorite version of ____, so we gave it to someone who could put it to use. Thanks again!” If she tries a guilt trip, remind her that you asked her not to buy you things without checking first and you hate to see things go to waste. If having it given away bugs her enough, she’ll stop doing it eventually.

Engage her positively with three “safe” topics. I suggest:

- One TV show or author or other pop culture thing you both like.

- One hobby or interest (doesn’t have to be a shared one) that she likes talking about- “How’s the garden planning going? Got your seed catalogs yet?“

- A topic where she is the acknowledged expert. Family history can be a great one for this.”What was (Husband’s) favorite food as a kid? What was it like when you first started working? How did you meet Husband’s dad? Are there any pictures of you going to parties when you were young? What were the hairstyles like? Did you have a favorite dress? Did you wear ridiculous platform shoes back in the 1970s? What was it like the first time you voted?“

(P.S. If you’ve never understood why people follow sports and talk about them all the time, try thinking of them as a fairly low-stakes, localized conversation topic that’s always changing a little tiny bit depending on the scores this week.)

She’s probably gonna clean your house when she visits for the rest of time. It is the way of parents. So, channel her energies with projects that you’d like done but don’t really want to do yourself, like, going through the spice rack looking for expired spices or installing shelves in the hall closet or sorting your sock drawers by occasion and color. Last time my folks visited I ended up with curtains hung in every room and lots of advice about bookshelf placement. My dad grumbled the entire time he hung the curtain rods but if we hadn’t found something for him to do he’d have found something for himself to do. Thank her profusely for working on channeled/requested projects – “We really appreciate your help with x project, Ma!” Try ignoring it or being pretty noncommittal when she goes off-schedule. “We didn’t need the sheets ironed, but suit yourself I guess.”

Ditto for gifts like suits, probably. If it makes her feel good to give your husband stuff like a new suit, sometimes accepting the other person’s gift IS the gift. I’m not saying it’s fair, or right, just, choose your battles.

Keep your visits short. You’ve got about a day of tolerance before you collapse? Then I guess your visits last about a day, with a scheduled recovery day! Make sure some of that day is budgeted for engaging with her attentively and think about arranging some of that time to go to the movies or seeing a concert or theater – special, fun, togetherness outings that give you both a reprieve from talking and a safe topic of conversation afterward! Also, take turns hanging out with her so you both get some time to yourselves. Naps are great, as are baths, as are solo drives to pick up milk even if you don’t need more milk.

Press the re-set button often. You’re not going to change the dynamic in a single conversation or even in a single year. If you do this right, you will basically train her that:

- She’ll get your husband’s & your focused attention at set, predictable intervals.

- If she tries calling every day or multiple times a day or turning everything into a conflict, she’ll get less attention from y’all.

- There’s really no point in giving you unwanted stuff – you won’t fight with her about it anymore, you’ll just give it away, every single time.

- She can state opinions and give unwanted advice if she wants to, but your answers to all that will be very boring. “Thanks!”

- If she engages positively with you, you’ll do your best to give her your full attention and talk to her about things she’s interested in and make her feel welcome.