“It’s passionately interesting for me that the things that I learned in a small town, in very modest home, are just the things that I believe have won the Election.” – Margaret Thatcher, 4 May 1979

“It’s passionately interesting for me that the things that I learned in a small town, in very modest home, are just the things that I believe have won the Election.” – Margaret Thatcher, 4 May 1979

“The biggest horror is that the whole world’s becoming suburban. I find it very worrying.” – Norman Mansbridge

COVER

The last thing on anyone at IPC’s mind, when they launched a comic, is that somebody might actually want to keep the thing. Comics were born on the production line, and landfill was their grave, and in that brief span between their urge was not to survive but to reproduce, to impel the reader to buy next week’s issue. So in May 1979 the second issue of Jackpot – “IT’S A WINNER” invited mutilation at front and end. On the cover, a free SQUIRT RING to lure buyers in, mounted with sellotape, which still sticks to my Ebayed copy, covering a gash in the paper like a badly sutured wound. On the back, a coupon to fill in, cut out and hand solemnly over to the newsagent: “PLEASE RESERVE A COPY OF JACKPOT FOR ME EVERY WEEK”.

It’s a loyalty game. There are only so many kids who want to buy comics, and most of those already do. A new title offers a raft of new stories, which may or may not wear better than the ones in the comic you already buy, whose formulae have begun to thin and fray. But with a squirt ring, too – who wouldn’t risk ten pence? Then once you’re snagged, the magazine urges you to the newsagent for next week. You don’t want to miss out.

So it is that the first comic you see in Jackpot No.2 is a three panel, silent strip, admirably clear, instructing you on the use and delight of your squirt ring. Panel 1: a girl shows off her ring to a passing boy. Panel 2: the boy leans in close to admire this fine piece of jewellery. Panel 3: SPLOOSH! A deluge – in the poor sap’s face. HAW HAW!

Reality disappoints. The squirt ring is an ugly lump, it brings no boys to the yard, and the feeble spit of water its bulb holds wouldn’t trouble an ant. Like most cheap pranks, the squirt ring only works if all participants have silently agreed it will – an indulgent Dad, perhaps, leaning in to play the patsy.

This conspiratorial element, this lack of real surprise, is not unique to the squirt ring. To grow up in any culture is to become gradually aware of its web of social relationships, customs, and norms, and of your place in it. Only so much of this awareness can come from direct experience. The rest of the job is done by stories. Fairy tales, comics and cartoons – the first fictions you meet – carry in miniature an implicit social order, or, more rarely, a glimpse of alternatives. We romanticise comics for kids as an escape from reality – an opening of a door into wonder. But to do this they often play a double game, and reinforce reality at the same time. If you want to understand a society, look at its comics.

IPC/Fleetway, publishers in the 70s and 80s of Buster, Jackpot, Cor!, Whizzer And Chips, Knockout, Monster Fun, and dozens of other weekly comics, were not especially interested in alternative social orders. When such things disturbed them in real life – in the form of union action, for instance – the typical reaction was harsh. The existing social order, on the other hand, interested them a great deal. It was their bread and butter. The twenty or so strips making up a typical Fleetway title were social comedies for the under-10s, in which all the hierarchies and absurdities of society might be turned into a gag strip. The status quo might be mocked, but not seriously challenged. The jokes in these social comedy strips, like the squirt ring, work because everyone agrees that they will.

If the cover dates are right, Jackpot’s first issue came out on the day of the 1979 General Election – a genuine challenge to the status quo. I don’t remember the election. I do remember buying Jackpot. It became my comic – ten pence a week, every week, bought with especial loyalty because I’d been in it from the start.

A comic is a machine for understanding society. How does this one work?

RICHIE WRAGGS

The first strip is by Mike Lacey, son of another comics artist, Bill Lacey. British humour strips are identified by artist: scripts were provided by other, nameless freelancers, or often simply worked up in-house. In the case of a new comic with new stories, like Jackpot, the artists might have a hand in the look and feel of the strip – vital, since the plots are so rudimentary.

Most strips are one-pagers, turning on a simple premise. In this case, Richie Wraggs is a poor country bumpkin turned tramp, looking to make his fortune alongside his cat, Lucky. Each week he seems to have fallen on bad luck, but the situation reverses to produce a happy ending and – always temporary – riches.

This episode rests on a laboured pun about “crock” – the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow – and “crock” meaning worn out vintage car. This won’t be the last pun we see. You imagine scripters, close to deadlines or the end of their tethers, reaching grimly for a pun in lieu of a plot. That this is the best they can manage two episodes in doesn’t say much for Richie Wraggs’ potential.

Given an idiotic story to work on, Lacey has a decent go. The meandering plot at least means Richie Wraggs shows off many iconic subjects of British comic art. We see cats (a fleabag, naturally), heaps of sausage and mash (the national cartoon food), and accidents involving a pot of paint.

And, of course, yokels. Richie Wraggs talks in West Country shorthand, and is inevitably a dimwit – the rather faithless Lucky provides commentary on his foolishness. His benefactor, an old man in a large fur coat, is upper class and genial. As we’ll see, it’s rare for posh characters in Jackpot to be shown in a good light: presumably the law that country folk are fools is stronger than the law that the upper classes are venal graspers. There is no letters page in Jackpot: if anyone from Richie Wraggs’ part of the country read it, they had no outlet for complaint.

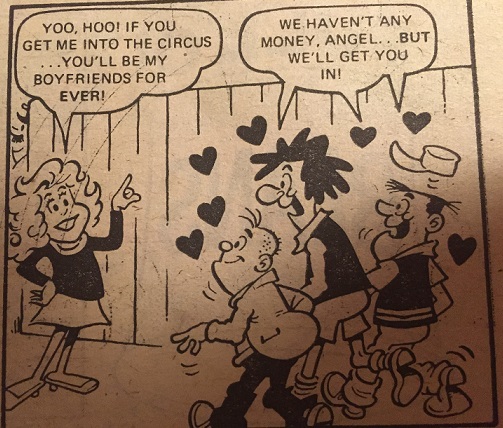

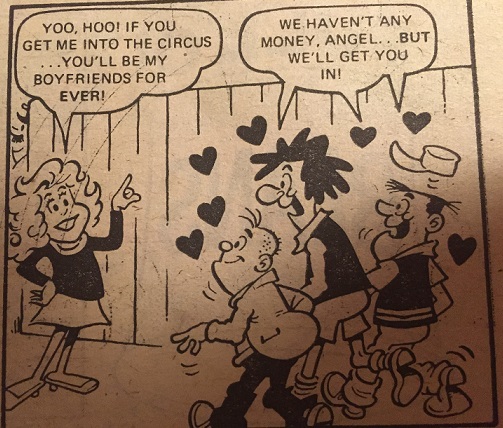

ANGEL’S PROPER CHARLIES

The second strip is by Trevor Metcalfe, an art school graduate who got into comics after his National Service. In title only, it’s a TV spoof – one of the genres British comics ran on. Angel, a young girl, has three boy admirers, her Charlies – each week she beguiles them into helping her with some mischief. This week she wants to get into the Circus without paying.

Jackpot might have been bought by any children, but it’s obviously pitched as a boys’ comic – the majority of protagonists are boys, their friends are generally boys, and so Angels Proper Charlies is unusual. Not just because its lead is a girl, but the central theme of the strip is boys making fools of themselves over a girl. Angel is imaginative and resourceful, but not entirely independent: her job is to manipulate boys with her beauty. With the rather icky job of signifying pre-teen irresistibility, Metcalfe wisely goes for big 70s hair and a big smile: sophistication, not sex. The main audience, I’d guess, was kids with older brothers and sisters, viewing their emergent passions with a pitiless and scornful eye. Still, the message – girls will try to make a chump of you – comes through miserably clear.

For the second strip in a row, the plot involves slipping through a board in a rickety fence.

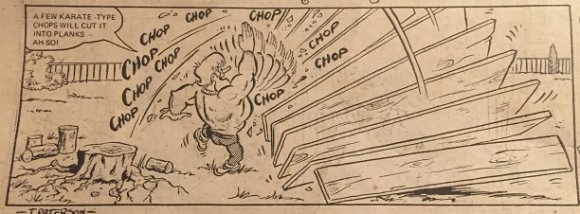

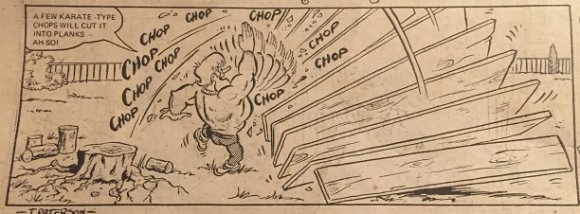

FULL O’BEANS

The third strip is by Tom Paterson, hired by IPC straight after leaving school. Paterson’s art is immediately more enticing, wilder and more exaggerated, than anything in the comic so far. He’s a follower of Leo Baxendale, creator of the Bash Street Kids for IPC’s great Scottish rival DC Thomson, and probably the single major figure in British humour comics. And you can tell. The physicality, the love of action, and the occasional grotesquerie in Paterson’s style are straight from the Baxendale playbook.

Full O’Beans is a strongman story – a stock “kids with amazing powers” idea. In this case Freddie hulks out when he drains a can of cold beans from his special stash. The plot is beyond basic – a drawer in Fred’s Mum’s dresser is stuck, he uses bean power to open it, wrecks the dresser, then rebuilds it. The focus is all on ludicrous feats and uses of the super strength – like chopping a tree into planks.

Any fences? Yes. Fred and his Mum are poor – their room is damp and peeling – but they live in a detached house with a fenced garden. It will turn out that almost every room in every strip, from office to home to hovel – is drawn this way, full of mildew and old wallpaper. (See story #20, Laser Eraser, for an illustration). A few years before we’d moved house, from a bungalow to a three-bedroom suburban home. Exploring the new home is an early memory. The vacated rooms were as Jackpot describes.

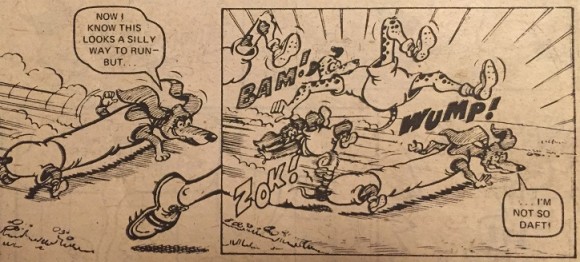

MARATHON MUTT

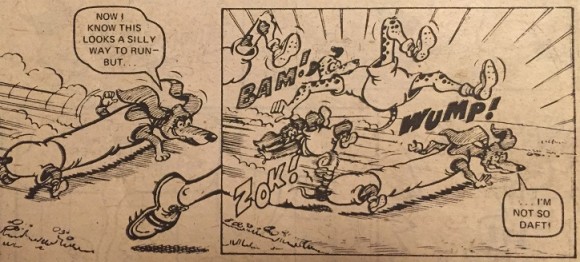

The fourth strip is by an unknown artist – the only one which I couldn’t find even claimed credit for. Some strips in Jackpot are signed, some aren’t. There’s no consistency, and it’s not as if the big name illustrators get signatures. It’s a shame I can’t find details for Marathon Mutt, as it was a particular favourite.

Partly that was down to the unusual format. Marathon Mutt is a gag strip done as a continuing serial – the adventures of Henry Bono, an anthropomorphised greyhound, who competes in a marathon against other breeds of dogs. Each breed has a gimmick – a sausage dog rolls, a springer spaniel bounces, and so on. The inspiration is obviously Hanna-Barbera’s Wacky Races cartoon, a showcase for this mix of slapstick comedy and minor dramatic tension. Back then it was the tension I liked. Now I like the textures of the landscape, which create a rudimentary but welcome sense of place. But Marathon Mutt is out of step with the social comedy of the rest of the comic, even with the cliffhanger it’s a little gentler.

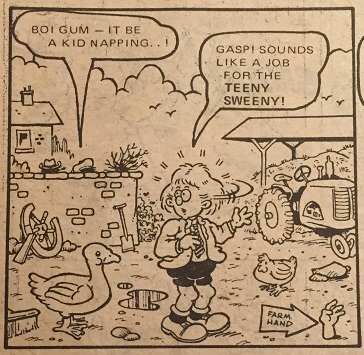

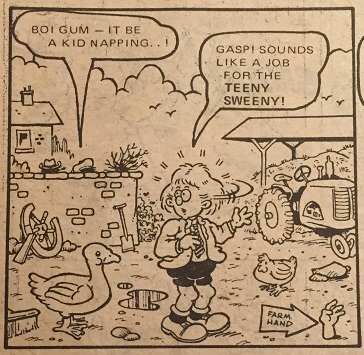

THE TEENY SWEENEY

The fifth strip is by Jack Oliver, one of the younger IPC artists at this stage and another obvious Baxendale disciple – wilder than Paterson, indeed. The story is a TV spoof, more direct this time – its leads are roughly meant to be child versions of Regan and Carter, the heroes of British cop show The Sweeney, which had just finished its TV run, full of hardcase action and car chases. For The Teeny Sweeney, this means an appearance for a staple of British comics, the cartie, a rickety, gravity-defying soapbox cart.

Broadly speaking, the imagined suburbia of Jackpot strips – fences and all – is recognisable from my childhood. The strips are not quite placeless – in this one, our heroes cart their way to a farm, which suggests a more rural backdrop – but generally you can map Jackpot’s landscape onto most towns outside the very inner city. The home-made contraptions of kids’ comics, though – the soapbox carts and catapults – were alien to me. I was too middle-class to have friends who built them? Certainly a possibility – but it also seems likely that in their heyday these gadgets had proved themselves too useful to cartoonists to ever be discarded, visual shorthands for all kinds of outdoor fun.

The gag in this strip involves overhearing a farmer talking about a “kid napping” – the writer usefully including a space, to drain as much humour as possible from the payoff (perhaps you too can guess). Maybe it’s the quality of the material that nudges Oliver into indulging one of British comics’ greatest traditions – filling panels with puns, sight gags, and extras: a disembodied hand marked “FARM HAND”, or the words “CARTING IS SUCH SWEET SORROW” on the side of the speeding soapbox.

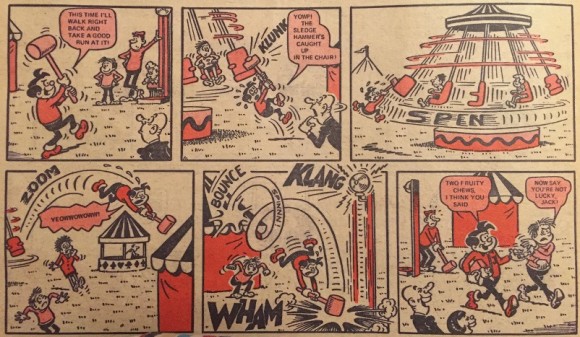

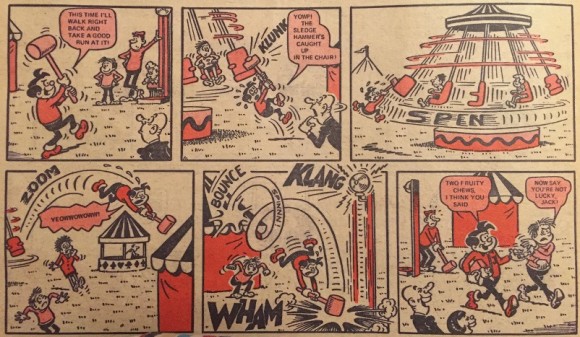

JACK POTT

The sixth strip is by Joe McCaffrey, who learned to draw while at sea with the Merchant Navy. He was in the middle of a long IPC career, creating Jack Pott for an earlier Fleetway title, Cor!! This makes Jack Pott the only strip carried over from any previous comic – IPC in their 60s and 70s prime much preferred to commission new titles and fresh (or re-sprayed) ideas than run reprints.

Jack Pott is a good example of a theme strip. Jack is a kid who wins things. That’s pretty much all there is to it. He’s lucky, or skilful, or a good gambler, depending on the story. It’s not a promising set-up, and prone to disapproval, which is probably why the character had been rested for a few years and wasn’t given top billing despite the comic’s name.

McCaffrey does a fine job here, though. He’s not a chaotic cartoonist in the post-Baxendale mode, instead he cleaves to the jovial, unflashy, direct comic storytelling I think of as the IPC house style. So the strip doesn’t have a lot of visual fizz, but the storytelling is impeccably clear. This is the first story where you don’t need the captions – Jack’s friend challenges him to win a ring-the-bell game at a fairground (another stock setting), and by a bit of luck and slapstick, he does. Two panels have zero dialogue – a sign of trust in a pro, you’d think.

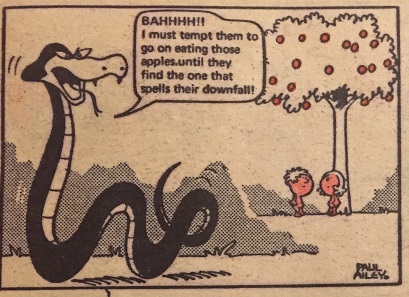

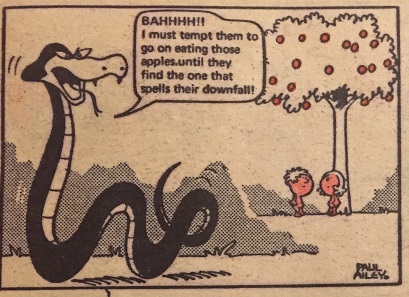

LITTLE ADAM AND EVA

The seventh strip is by Paul Ailey, an artist who mostly ghosted and filled in on other strips, but gets a signature here, on Jackpot’s most bizarre story. Adam and Eva are kids, in a garden, which possesses a tree of knowledge, and a serpent – Serpy! – who is trying to tempt them to eat its fruit, because one particular apple will “spell their downfall”. Luckily, the other apples don’t do this, they just give useful tidbits of info.

Theologically this is an interesting take. Though of course the garden isn’t named – that wouldn’t get past the IPC editors. It’s testament, if nothing else, to IPC’s unshakeable belief that there is no situation you can’t get a strip out of if you make the characters kids.

Serpy is one of the most obscure Satan figures in British comics, and one of the more entertaining, but even more so than Marathon Mutt, Little Adam And Eva is way out of step with the rest of the comic. (I remember rather liking it.) Ailey has an attractive style, light on detail with a nice strong line and bold shading. Unfortunately, the strip gets an extra colour – red – which only emphasises the fact we’re reading a story whose leads spend the entire time naked.

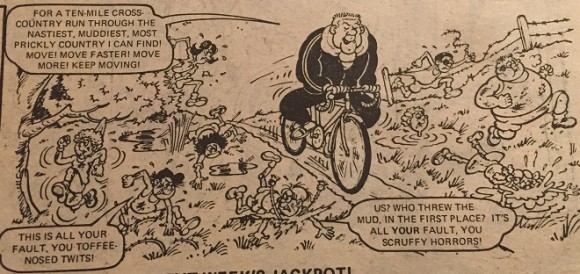

CLASS WARS

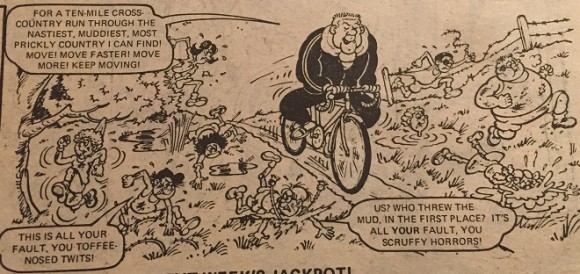

The eighth strip is by Vic Neill, who’d mostly worked for Beano and Dandy publishers DC Thomson. He’d modelled his style initially on Dudley Watkins – another great UK comics figure, creator of the Broons and Oor Wullie. Watkins’ art was rooted in strong storytelling, an unusual degree of detail and a great repertoire of comic faces. On Class Wars, Neill offers a more streamlined version with touches of Baxendale grotesque. It works well – the story’s two pages hardly need their dialogue.

The strip title is pun intended. This is the first story where Jackpot’s social comedy turns into conflict. it’s a school strip (every mag had at least one) with the tension coming from a mixed class of working-class scruffs and stuck-up posh kids, thrown together when a private school is forced to merge with a comprehensive. A burly teacher acts as referee. In this story, the scruffs are doing their best to pelt their posh classmates with mud.

The resolution here is wildly unfair – eventually the teacher, treated with contempt by the scruffs and obsequious but patronising regard by the posh kids, gets hit by mud himself and gives everyone a cross-country run as punishment. But the strip knows better than to go against the social coding of decades of kids’ comics: tearaways have more fun, snobs don’t, so the snobs have to get their come-uppance in the end.

Except Class Wars is a much more conservative story than it might look. The outcome may be unfair, but the codes of behaviour are absolutely clear. Working class kids in this story are lazy, thuggish, and hate learning. Their moneyed counterparts are prigs, but hard-working and resourceful. Within the standard knockabout of the class-tension storyline, resolved as usual when authority intervenes, lurk some very nasty stereotypes.

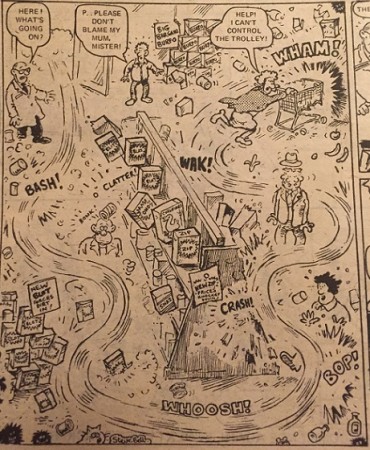

GREMLINS

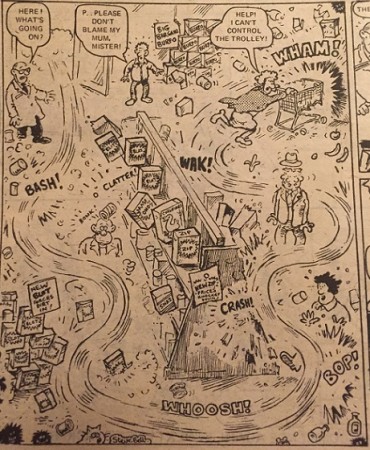

The ninth strip is by Steve Bell, a former art teacher, briefly stopping over at IPC en route to spending 30+ years drawing the If… newspaper strip for the Guardian. Bell’s style is still in development but it’s recognisably him – the fleshy roundness of his characters with their bulging noses; the toothy black blots that are the titular Gremlins, agents of mischief and malfunction in an ordered world.

Bell, a young cartoonist, is firmly in with the post-Baxendale wing of Jackpot, and while he’s not as extreme as some he’s inherited Baxendale’s love of disorder. The Gremlins exist to make things go wrong, Bell exists to depict the consequences as entertainingly as possible. The strip builds toward a single large, chaotic panel as a gremlin-infected shopping trolley goes wild in a supermarket. Nothing is resolved – the human leads can only flee as the shopkeeper shouts “GRRRRRRR!!”. There’s a gleeful chaos here quite unlike anything we’ve so far seen – order is not restored, and the gremlins represent the unpredictable and unaccounted for in Jackpot’s comic suburbia.

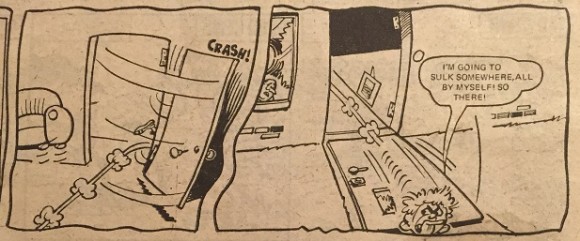

THE INCREDIBLE SULK

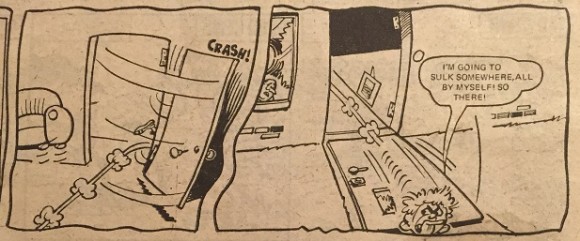

The tenth strip is by Jim Petrie, a DC Thomson lifer, who drew 2000 episodes of Minnie The Minx. The Incredible Sulk was rare IPC work for him, and he’s obviously enjoying drawing in a rather looser style: the strip plays with panel borders as a component of the story, a common trick now but unusual in this era. As Sulk’s rage builds, the edges of panels distort and their composition gets stranger – at the height of his anger, Sulk is barely on-panel, racing out the back and the front of panels, so angry he wants to break out of the strip.

These elemental tantrums made Sulk one of the comic’s biggest hits – never mind the very repetitive nature of the strip, this is pure wish fulfilment, a kid not only losing his cool (as they all do) but getting utterly away with it. As in Gremlins, the strip cuts out with chaos firmly in the ascendant. But here it’s a more relatable human chaos. I don’t know if Petrie was doing the stories as well as the art – there’s definitely a sense he’s being given a much longer leash than most of the artists, and he’s using it to the fullest.

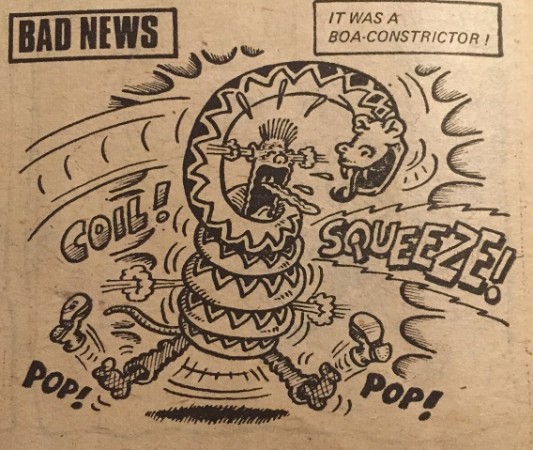

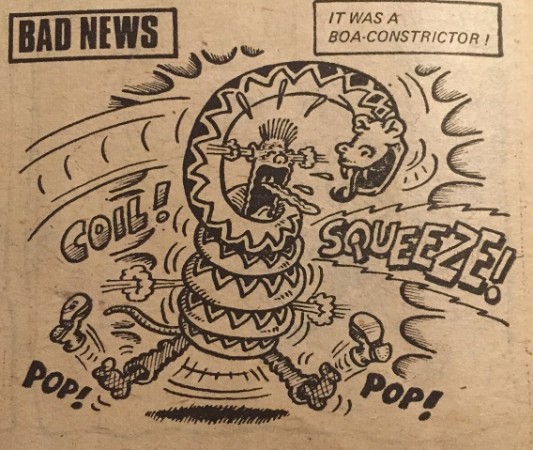

GOOD NEWS/BAD NEWS

The eleventh strip is by Nigel Edwards, more prolific in the 80s for IPC – this may be his first gig, in fact. He’s yet another in the looser, Baxendale mode – his hero is a cheerful grotesque, and the liberal use of sound effects (“PONG! REEK! WAFT! GASP!”) shows the desire to cram as much comic detail into the strip as possible. Edwards would become a major contributor to OINK!, the last doomed triumph of the Baxendale style, a scatological “Junior Viz” of the mid-80s which goaded the censorious elements in British society and quite swiftly fell to them.

Back in 1979, this is one of the more unusual Jackpot strips, a formalist conceit, with a twist in every panel. Good news and bad news alternate – each situation is either complicated or resolved one panel on. The result, inevitably, is a strip that’s much denser than the average, with no panels wasted. A perfect fit for Edwards’ style, and it was a favourite of mine at the time. But it’s also slightly exhausting, a rigid fever pitch of action, laying bare the principles of rapid comic development that every one-page humour strip is discreetly obeying anyway.

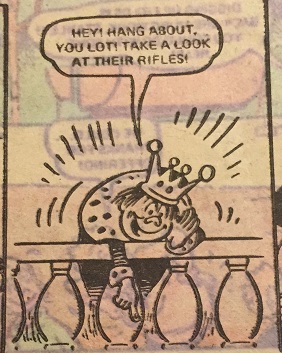

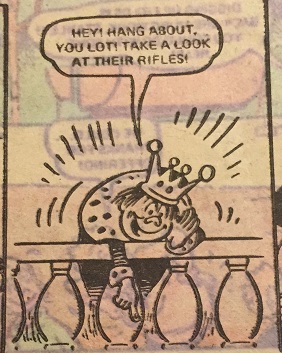

KID KING

The twelfth strip is by Reg Parlett, son of an illustrator and postcard artist, and an IPC stalwart – he’d been at the company since 1923 and had over a decade’s work still in him at this point. As the excellent site Toonhound points out, it’s astonishing nobody had come up with this strip’s concept before – the ultimate fulfilment of the “kids do grown-up jobs” genre, a British comic staple. What job is more important than a King?

Kid King is a fantasia of absolute childishness rubbing shoulders with the absolute pomp of adulthood. All through this episode, kids invited to play in Kid King’s palace constantly think the guards are going to kick them out (or mow them down!). In fact they’re handing out toffee apples and lollipops – a carnival inversion straight out of the hippie imagination. But Play Power, or any kind of power, isn’t on display here: the strip is never about mocking the monarchy or its trappings, just about how fun it might be to have them as your toybox.

Parlett’s bold, fluid line is a great fit for the story – he’s a master of body language, revelling in the contrast between the loose-limbed Kid King and his stiff-backed retinue. Body motion in a lot of Jackpot strips feels rather overdone – a lot of windmilling arms, leaping, kicking to swiftly diminishing effect. Parlett, wisely, keeps it simple.

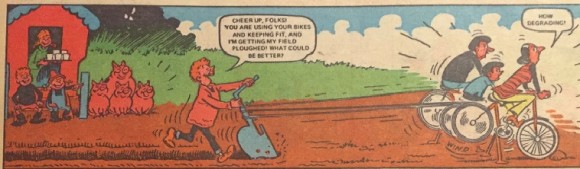

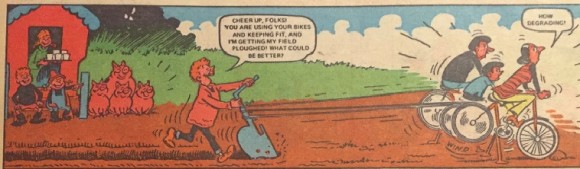

IT’S A NICE LIFE

The thirteenth strip is also by Reg Parlett, and it’s Jackpot’s colour centrefold. Jackpot’s palette is basic but very lurid – ultra bold yellows, reds, and greens with little mixing. This isn’t the best fit for Parlett’s art. His style is smooth, leading the eye easily from panel to panel – the colouring slows it down, even wrecks some gags. A three panel sequence of Stanley Nice trying to yoke pigs to a plough loses all detail: just not enough contrast between pigs, mud, and Stan’s jumper.

It’s A Nice Life is the most clanking of all Jackpot’s TV spoofs. It’s a comic remake of massively successful BBC sitcom, The Good Life, with the main tweak being that both the eco-friendly “self-sufficient” Nice family and their stuck up neighbours have kids. Not the only tweak, though. The Good Life was a gentle satire on both suburban aspiration and alternative lifestyles, with both families roughly on the same rung of the social ladder.

It’s A Nice Life is less ambitious. Satire isn’t the aim – the set-up is just an excuse for more on that favourite IPC theme, the class struggle. Stanley Nice and his family live in a caravan. Next door is a large private home with not just a car in the drive but a private motorboat. Whatever the origins of this pair’s rivalry, by its second episode the irresistible rhythms of the IPC class conflict strip have asserted themselves.

The stereotypes are more one-sided than Class Wars. Stan himself is just a twinkle-eyed cheeky chap. His rich neighbours – like the earlier strip’s posh kids – have a love of consumption and a horror of dirt. Naturally the strip ends with them ploughing their neighbour’s muddy fields with their precious new bicycles. (“HOW DEGRADING!”) Below the gag is a very 20th century bourgeois nightmare – to be stripped of your assets and put to work farming: a suburban Cultural Revolution, played for laughs.

Not that Mao was on the minds of the IPC scriptwriters – though with the pressure to crank out pages to fill a half dozen titles, you took your ideas as they came. But it’s emblematic of social relations as they play out across Jackpot’s strips. The world of Jackpot accepts that class struggle is axiomatic. But it also accepts that this is eternal – its class war is also a cold war, resetting, week upon week, to comic stalemate. No outcome to the class struggle is ever in prospect. The toffs would always despise the toughs, and vice versa – such were the facts of life. In which case best to have fun with them. This, if anywhere, is where the comic reflects the consensus politics of mid-century Britain, which ended the week Jackpot began.

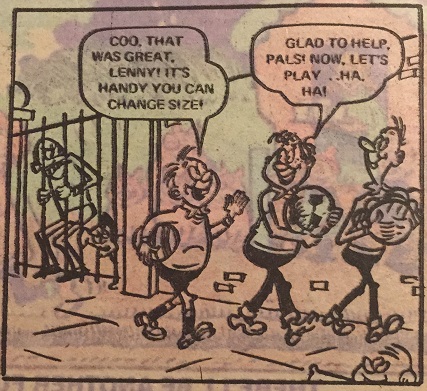

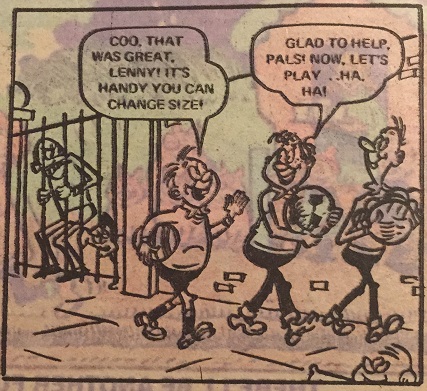

LITTLE AND LARGE LENNY

The fourteenth strip is by Norman Mansbridge, a former political cartoonist, of no strong party opinion, who had turned to kids’ strips in his retirement. His speciality as illustrator and comic artist was suburbia, and he spoke of his growing realisation that the orderly jollity of suburban existence often masked cramped, neurotic lives. His great contribution to British humour comics was Whizzer & Chips’ Fuss Pot, one inspiration for The Incredible Sulk: a girl whose unstoppable tantrums drove her respectable suburban parents to despair. The repression and selfishness of suburban life made manifest.

Since almost all of Jackpot’s strips are set in an undefined semi-suburbia of fences, busy streets and neat lawns, Mansbridge is an obvious fit. Unfortunately, he’s saddled with an uninspired kids-with-powers strip. Lenny can grow big and small, and uses the power to discomfit a grouchy suburban hoarder of lost footballs – yet another stock strip character and crime. Size-changing is one of the great gifts to comic illustrators, a ready-made excuse to have fun with perspective, which Mansbridge does. But I’m not surprised this is one of the Jackpot strips I didn’t remember.

CRY BABY

The fifteenth strip is the second by Mike Lacey, artist on Richie Wraggs. In rare interviews with IPC script veterans, former writers explained the firm’s methods. Artists would stick with a strip for a long time, while the uncredited writers would often be rotated to keep them fresh. Run out of ideas for Jack Pott? Have a go on Kid King! Inspiration proved easier with some strips than others. Writers particularly cursed “Sid’s ****ing Snake”, a flagship Whizzer & Chips strip about a boy and a giant serpent. Notoriously stony ground for ideas, let alone laughs, yet too popular with the readers to ever ditch.

Cry Baby does not strike me as a strip with legs. It’s a cross between the Incredible Sulk subgenre of tantrum wish fulfilment and the amazing powers strip. Tina has the mutant power of producing literal floods of tears. In this strip her nervous suburban parents put her into a wetsuit and bathtub before obtaining – how? – a sea rescue raft, which she fills with tears and uses as a swimming pool. It’s a strange story. You can imagine kids fantasising about getting their own way, but incessant crying? Part of the point, though, is the pantomime of parental anxiety: “OH NO! YOU’LL SOAK OUR NEW CARPET!” And there’s something primal and powerful about how terrified the parents are of their daughter’s emotion and its potential to wreck their home and possessions.

This feels like a good place to point out that everyone credited or claimed as working on Jackpot is a man.

THE TERROR TOYS

The sixteenth strip is the first whose scripter we can identify. It’s Tom Tully, an old school IPC action writer who did a lot of sports story work. By 1979 Tully’s long career was winding down, but The Terror Toys is a re-edit of a 1960s strip, The Toys Of Doom. At four pages long it’s double the length of anything else in the comic, and is also dead serious – a sudden insertion of action into the humour format, varying the tone. It worked on me: I was hooked by the story of tiny, deadly toy soldiers and murderous bears – one scene, where a child was attacked by toy battleships in his bath, gave me nightmares.

If Tully’s identifiable, the artist is trickier. The drawing is pitched older than the other strips – more realism, more shadow, more detail in the background, and less of the kind of art an older, sillier me would learn to disdain as “cartoonish”. It’s a solid, old-fashioned action comic: two kids stumble upon the plans of a grotesque toymaker, but neither adults nor their peers will believe them. (Their tactics involve smashing up kids’ brand new toys, not a great dialogue starter.)

The internet suggests either Argentine great Solano Lopez – best known, at least by Google, for his porno comic Young Witches – or an artist from his studio. To complicate matters bits of the strip have been redrawn as well as edited. Still, the thick, Raggedy Ann style hair on the kids reminds me of the cheap, stylish South American artists IPC habitually used on their older boys’ comics, even if it looks nothing like Lopez.

The Terror Toys has little to do with the rest of Jackpot: even though I loved it, it was a few years before I read adventure stories for preference. I’m a little sad to learn it was a reprint – its thrills age six felt purely mine – but not surprised. Whoever drew it, their reference might have been stills from any 30s or 40s British film, even one set fifty years before that. This is an incursion from a foggier, creepier old England than the merry suburbs of Jackpot standard.

TERRY AND GAVIN’S FUNTASTIC JOURNEY

The seventeenth strip is by Ian Knox, who’d trained as an architect, but at this point was doubling a job drawing kids’ comics with a role as “Blotski”, the political cartoonist for Red Weekly and Socialist Challenge. Perhaps fearing his revolutionary potential, IPC have given him the comics’ least earthbound strip, a surrealist fantasy in which a pair of children and a crazy professor take to the skies in a “Welly-copter” and visit one absurdist land a week.

Of all the Jackpot strips, this feels one of the most old-fashioned – maybe it’s the Welly-copter itself, as the comic potential of the welly boot was an article of misplaced faith when I was small. Or maybe I’ve just never clicked with this brand of zany fantasy, whose unlikely events seem arbitrary in the way the handy life rafts and passing vintage cars of other strips never quite do. It doesn’t help that the kids rely on their adult friend to get things done – mostly because it turns the second half of the strip into exposition, but also because Knox can’t seem to nail perspective and get the height ratio of kids and grown-ups consistent. (In fairness, he’s dealing with a magic land where everything floats, which is a bugger to establish distance and direction in).

There’s an irony, too, that of all the strips to suffer from Jackpot’s elephant-gun approach to colouring, it’s Blotski’s that arrives absolutely doused in red.

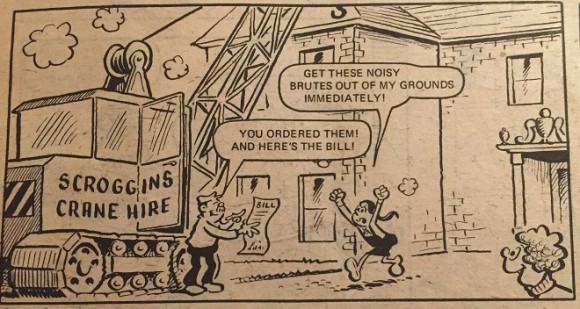

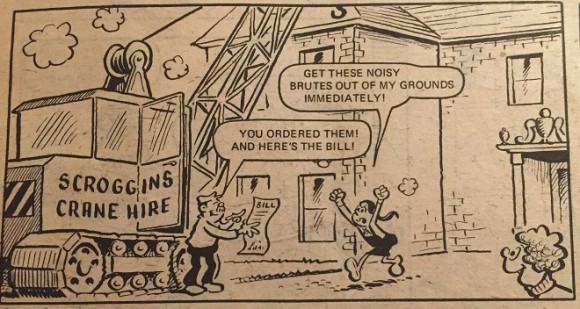

MILLY O’NAIRE AND PENNY LESS

The eighteenth strip is by Sid Burgon, a former mechanic whose co-workers encouraged him into a career drawing. He drew for some of 70s IPC’s most popular strips – like Ivor Lott And Tony Broke in Buster, of which this is a sister strip. If it wasn’t obvious from the title, this is, yet again, a class conflict story. Unlike in It’s A Nice Life, there’s no TV spoof to provide a pretext. The set-up is very simple, though. Milly O’Naire – who lives in Moneybags Mansion – is rich but vain and mean. Penny Less is poor but ingenious. Penny wants something from Milly, and each week works out a way to get it.

This is a strip you could imagine Blotski getting his teeth into. It opens with Penny Less and her family, reduced to eating stale bread. She goes to Milly’s mansion only to find her serving banquets to her pet ostriches, who peck Penny off the grounds. There’s no camaraderie here, and none of the hidden stereotypes of Class Wars: Milly is nakedly hostile to her poor counterpart, and is unequivocally the villain. And the resolution finds workers occupying Milly O Naire’s grounds until she pays them to go away.

This is the most accomplished and satisfying of Jackpot’s class struggle strips, and Burgon is one of the definitive IPC house style artists, with his chunky backgrounds, fluid line and rock-solid storytelling. When I think of reading IPC titles as a kid, it’s Burgon’s art I see. But Milly O’Naire And Penny Less is thoroughly of its time. It gives zero ground in assuming the rich are venal and callous, and the poor are quick-witted and deserve a slice of the wealth. To use a modern term, the strip “punches up”, however cheerily. And even though it’s a kind of pantomime punch-up, one centuries old, with no suggestion that the social positions it depicts could ever change, it’s impossible to imagine a humour strip like this getting made now, partly because the country sneers at families living on stale bread, who are nobody’s heroines. Meanwhile a rich girl feeding cake to her pet ostriches might land a reality show or a record deal.

But this was one of Jackpot’s most popular stories, just like Ivor Lott And Tony Broke (identical save gender) was in Buster. The kids culture of the IPC comics rippled with social and class anxiety, and readers loved it.

SCOOPER

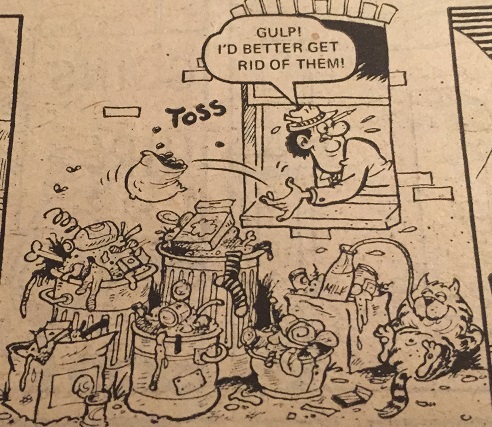

The nineteenth strip is our second by Tom Paterson, seen already on Full O’Beans. This is a much richer, more lovingly presented piece by him, crammed with details and full of a joyous grubbiness. Everything is dusty, run-down, grotty, but gloriously material. Paterson’s focus here is on expressive characters, particularly Scooper’s jowly, well-intentioned but incompetent Dad, whose nervous eagerness never lets up.

Scooper is a kids-doing-adult-jobs strip on journalistic lines, with Scooper the son of a local paper reporter. He goes out with his Dad to take pictures – which end up turning out to be of Dad screwing up. It’s a strong, flexible premise that means a huge range of things for Paterson to draw (this week it’s dogs). Notwithstanding a slightly flat script, Scooper is excellent.

And there’s something pleasing about one of the best stories in the comic being so low-concept: built on faith that a local paper beat is a place where funny things might happen. The one-line biographies of artists I’ve been giving suggest the range of backgrounds Jackpot drew its creative staff from – but one thing most of them, and surely their writers, shared was some immersion in journalism. Perhaps that accounts for the extra care Scooper seems to enjoy.

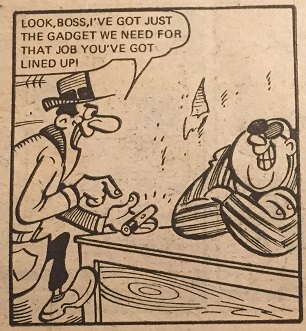

LASER ERASER

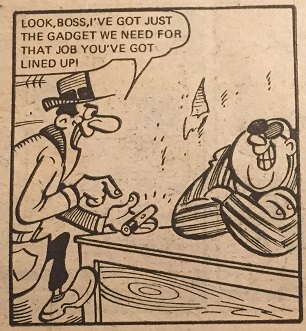

The twentieth strip is by Robert Nixon, an art school associate of Mike Lacey and similar in his clean and simple style – certainly on the ‘IPC house’ side of things. The strip knows the virtue of getting off to a brisk start: “EEK! HELP! ESCAPED GORILLA!” are the first words you see. “COR!” says our hero Ernie, and in panel two he’s zapped it into nothingness with the strip’s eponymous device.

The Laser Eraser can make things vanish from one place and return in another (the gorilla reappears and squashes a couple of crooks who steal the gadget). Nixon is a compact storyteller with a particularly good line in facial expressions, which works with the breakneck plot to make Laser Eraser feel a dense, good-value strip. The Eraser itself is a scripter’s gift – as long as you can think of a reason to have anything you like appear, you can use the Eraser to drop it into any other scene, creating the surreal combinations IPC strips thrive on with no plot strain.

ROBOT SMITH

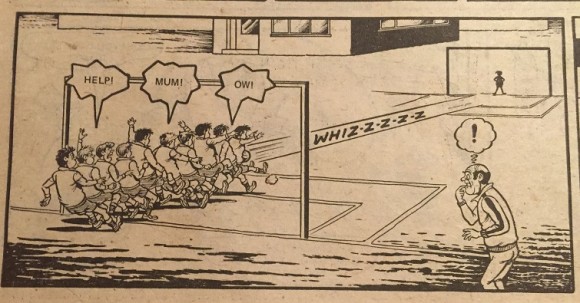

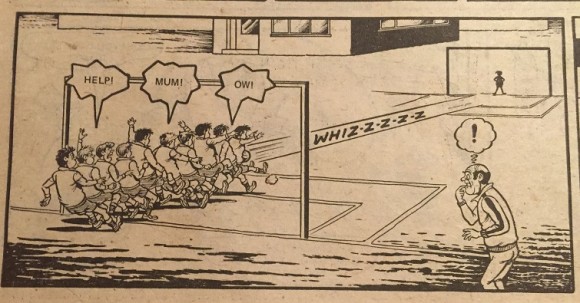

The twenty-first and final strip is by Ken Reid, one of the great names of British comics, who created Roger The Dodger and died at his board still drawing an episode of signature strip Faceache. Reid’s faces made his reputation – clean-lined, detailed, but always entertainingly contorted – and his strip has a different feel from anything else in the comic. More old-fashioned, somehow – for all the 70s realism of the PE teacher’s trackie and combover.

Part of that old-school feel comes from the storytelling. Reid was famous enough to write his own strips, and Robot Smith is the work of a man steeped in their form and formulae. A situation is established in the first panel, resolved in the last, and in between is a series of simple sight gags. This episode – Robot tries out for the football team – could have been a Ken Reid strip from any time since the 40s. Even the premise – a robot goes to school – is like something out of a Charles Hamilton school story, and Robot Smith’s rivet-studded jumper and spring-driven legs are just as archaic. Next to the wild, Baxendale-style strips which represent the young generation of Jackpot, Reid uses startling amounts of white space, and lays out his panels with geometric fussiness. Robot Smith sticks out, but it’s a living reminder of the traditions the rest of Jackpot has built on.

TO THE NEWSAGENT

That’s the end of the stories. The inside back cover has the coupon for the newsagent (with a Marathon Mutt illustration) and the Jackpot Top 20 League Ladder, which you can fill in to create a top of the Jackpot pops.

Which means it’s time to think about what isn’t in Jackpot. Two things stick out as absent.

The first is pop culture references, scrupulously avoided by the IPC writers, in this mag at least. All through these write-ups I’ve commented on the texture of the strips – how familiar some of it feels, how distant in other ways. Jackpot is pitched at ‘everyone’, and as is often the way, everyone turns out to mean an imaginary middle: middle-class, suburban, aware of the poor and the rich and the rural, but at a distance, as exotic and comical elements. You can recognise 1979 in the comics, but only those broad outlines. With the large but specific exceptions of the TV spoof strips, the pop cultural texture of the time is missing: no punks, wookies, time lords, footie fans, disco dancers. A section of life, kept at arms’ length.

The second absence is more glaring now. Every face – every excited schoolboy, enraged official, idiot posho, hapless parent, everyone – is white. This was what parts of Britain looked like in 1979, of course. But only parts. Britain had welcomed – a mixed welcome, often – thirty years of Commonwealth immigrants; two hundred years of Empire before that had left the country more diverse than its xenophobes would have you think. My home was in a leafy, middle-class suburb, not too far off It’s A Nice Life territory, and I was at school with kids from families from India, Pakistan, Uganda, Ethiopia. The Britain that Jackpot presented was a plain lie. In May 1979 parts of the world it drew, and drew laughter from, were ending. But in important ways they had never really been.

BACK COVER

“Published every Thursday by I.P.C. Magazines Limited, King’s Reach Tower, Stamford Street, London SE1 9LS”. This was the start of a long, one-way association between my pocket money and Kings’ Reach Tower. First Jackpot, then Buster, then Eagle, then 2000AD, and finally the NME. IPC had me from cradle to rave. I can appreciate now what I didn’t then – that it was a somewhat sclerotic operation, prone to censorious fits, conservative in subtle ways despite all the outward fizz of its magazines. But their editors had a good nose for talent, however poorly they treated it.

It seems clear, looking back at this comic, that the IPC kids’ line was firmly artist-driven, and that the company was happy to pull in freelancers of any age and a range of styles. That’s the most admirable thing about Jackpot – the sense of a pack of different artists, of no one dominant style. The gonzo fleshiness of Steve Bell and Nigel Edwards; the loose line and tight storytelling of Reg Parlett or Robert Nixon; the grimy detail of Tom Paterson; the open spaces and weird faces of Ken Reid. It wasn’t something I noticed at the time – aged six, you bought for characters, not for art – but unconsciously maybe it filtered through, gave me a feel for variety. The flipside is that the scripts were often pitiful, insultingly lazy, a half-baked pun often built out into a whole page. The better artists kicked against that, by quality of storytelling or just a riot of detail. The others just drew it, and no doubt hoped for something better next week.

Next week, though! “DOUBLE TREAT”, the back cover says. A “magic numbers” card game and the covers of a cut out partwork – “WHY BE BORED?”. The last of the free gift cycle Fleetway would permit a new launch. Three weeks in and it would have to walk by itself. It did, until 1982 at least. Then the cull came.

IPC’s policy with its comics was notorious: hatch, match, dispatch. Launch a new title, if it failed, find an existing one to pair it with, and put the weaker to death. The readers would be given a weeks’ warning – “Great news for our readers inside!”. In Jackpot’s case, the host – and the eventual last survivor of the IPC line – was Buster, which inherited a range of strips.

Laser Eraser, the most leggy of the gimmick strips, made it over. So did Jackpot’s first black lead, when he eventually arrived: he was called Sporty, and was “good at sport”. A score-draw for progress. Terror Toys got yet another reprint. And all three of the class conflict strips – Class Wars; Milly O’Naire And Penny Less; and It’s A Nice Life – survived. Nice Life could pivot easily from a strip about hippies to a strip about yuppies. Ingenious Penny Less got a scholarship to a private school in 1986 – Milly O’Naire’s Dad went broke paying the fees. As for Class Wars, it hung on until May 1987, from Thatcher’s first election win to her last. But by then things had changed. The strip left Jackpot behind it with a more 80s title: “Top Of The Class”.

All illustrations copyright IPC Publications

NEXT: Under the shadow of the slipper – a closer look at DC Thomson and the Beano.