Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

The M&Ms Store and the M&Mification of the World: Understanding the New Reification | Infinitely Full Of Hope

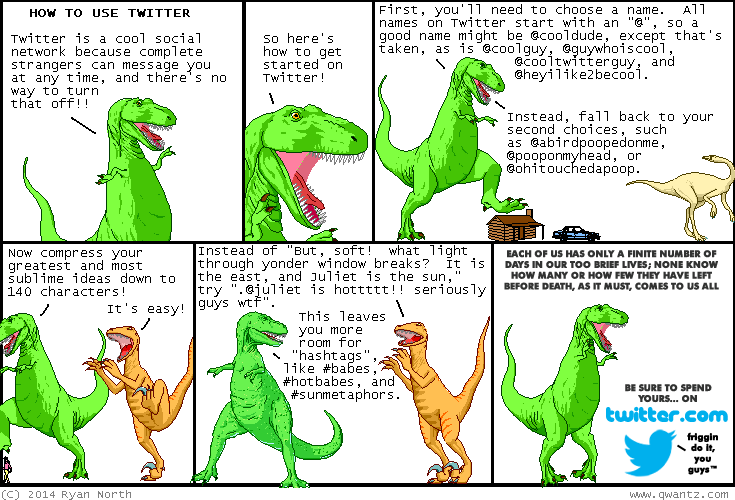

ps please distribute this content to your professional audience of influencers across various verticals on linkedin

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - cute - search - about | |||

| whoah, you can get to be or not to be in the latest humble bundle!

|

|||

| ← previous | March 31st, 2014 | next | |

|

March 31st, 2014: ECCC was amazing and also the best. Thank you everyone who came out! It was... the most fun?? I will write more about it later when I am less exhausted! EXCITING THINGS HAPPENING:

One year ago today: beach-based fun times, FINALLY – Ryan

| |||

Conditioned eye contact.

I can remember the last few times I made true eye contact, as clear as a snapshot.

-I was too distressed to make words happen and no one around knew sign. Eyes wildly snapped from person to person, looking for someone who could read my mind.

-I was in the ER getting stitches on my finger, which I had accidentally locked in a car door. I told them to not tell me when they were sticking me with the needles. They told me. Eyes flew to those of the person with me.

-One of those folks who thinks boundaries don't apply to him was getting too close and too cozy on the bus. Again, probing for someone who could recognize my distress.

-Someone was threatening violence in my direction at a thing I used to do, and I was meeting with one of the folks who had authority. His words on the experience are "please stop trying to set me on fire with your mind."

The elements of these scenarios are the same. Something is happening. I do not like it. I do not like it at all, and want it to stop immediately. Yelling and swearing has not worked. I can't hit it or kick it or pretend it doesn't exist. Those strategies have failed or have a 99.9999% chance of failing based on pattern data from years of experiences.

But eye contact makes them stop doing the unpleasant thing.

This doesn't make sense, does it? You've heard that eye contact is about sharing and social referencing and subtle messages and cues being sent among communicative partners. That's not what this is at all! This is the sledgehammer. This is the safeword, if you will, the "this stops now it has to it has to it has to make it stop nownownownownow no matter what".

Where did I get this idea? Therapy. That's where.

When I was a very small little child, the first thing they tried to get me to do was "look at me". Now, if I was a small child now they'd be still coercing looking at them. The new and improved way of forcing eye contact is to hold a desirable item between the adult's eyes and then give it to the small child when they look at it. This is still gross.

Back in my day, however, it was all out war. They would grab your face, they'd hold your hands down, they'd pretty much sit on you. It was a full out wrestling match until you submitted and looked them in the eye. Then, they immediately stopped. They immediately let go of your face or your hands or stopped sitting on your or stopped holding your shoulders so hard that the bones ground or what have you.

I was small. Hitting didn't work (I tried). Kicking was a no. Headbutting only worked once, biting was iffy. Covering my face got my hands dragged into my lap and held there. Dumping the chair and running was only a few seconds reprieve and led to the least comfortable hold ever. They had no compunctions about prying my eyes open when I squeezed them shut as tight as I could. No boundary violations were out of bounds. The only way to make the awful stop was to look in their eyes.

Reality land does not, in fact work that way. Eye contact is not the way to make things stop. People who know me understand that it means "something that is happening needs to not be happening right. now." Most people don't know that. People who only sort of know me can grasp that it's bad (see: "stop trying to set me on fire with your mind") but they don't know what it means. Strangers take eye contact to mean the opposite of what it does.

My brain knows that for most people a straight in the eyes stare is not the signal for "something needs to stop right. now." but it isn't that easy. One of the deepest conditioned things I have is "eye contact is giving in. If you do that, the bad will stop." This is irrational and untrue and the world doesn't work that way. It's deep, though, as the first and most consistent of the wrestling matches I had with adults as a small child.

This isn't what they thought they were teaching me. They claimed to be teaching me all sorts of things about eye contact. They didn't though. They wrestled me to the ground over and over to grind a lie into my head.

Night-blooming Flowers: Sudden skill acquisition and extreme context-dependence

Not To Rain On Anyone's Same-Sex Marriage Parade But...

They'd taken civil partnerships to their heart and any criticism of the legal issues was seen as a criticism of their own personal choices. So, as I am about to embark on yet another adventure in being the only miserable one at the gay pride party, I want to make it clear from the start here: I do not begrudge anyone who is going to enter into a marriage under the newly introduced law. I plan to take advantage of the opportunity, partner willing of course, to enter a blessed state of matrimony (blessed by the arms of Thor in case you were wondering ;) ). I wish those getting married every happiness and success. Enjoy yourselves!

However... same-sex marriage is not what I was arguing for back in 2009. As I said here, what we are getting solves only a small percentage of the issues that created the need for something better than civil partnerships in the first place.

Our Government has done marriage equality on the cheap. Stonewall, after they got over the opposition of 10% of their members drowning out the other 90%, have been next to useless in doing anything useful other than cheering from the sidelines. I don't think even today they've realised how rubbish the legislation really is, and it'll probably be another 10 years before they even get around to declaring their opposition to any correction of the failings.

We must continue to fight for a correction to the errors made over the last couple of years and make the same-sex marriage act into something even better. I'm not sure I have the heart for that fight. But I'm principled enough to point out that we are not yet there...

Lorenzo Semple Jr., R.I.P.

Writer Lorenzo Semple Jr. has died at the age of 91. A lot of folks reading this will recognize him as the main writer behind the Batman TV show of the sixties…and he did many other things, as this obit will tell you. I was not a fan of that show (or what it did to the public image of comic books) but Mr. Semple had a splendid body of work and he deserves to be celebrated for it…and for things other than Batman.

Anthony Tollin sent me a link to the obit. And Anthony Fiske sent me a question to ask why Semple is being billed as the "creator of Batman" in some reports. Well actually, I think they say he was the creator of the TV series, which is also not the proper phraseology. The Writers Guild has changed the rules from time to time but generally now, the person who writes the bible and pilot for a new series based on pre-existing material — which is what Semple did for Batman — gets the credit, "Developed for television by…" It was a little less formalized back when the show went on.

Wheat: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

After hearing conflicting advice from diet books and the medical community, I decided to look into wheat.

There are two sets of arguments against including wheat in the diet. First, wheat is a carbohydrate, and some people support low carbohydrate diets. Second, something might be especially dangerous about wheat itself.

It was much easier to figure out the state of the evidence on low-carbohydrate diets. They seem to be at least as good and maybe a little better for weight loss than traditional diets, but this might just be because there are lots of carbohydrates that taste very good and when forced to avoid them, people eat less stuff. They may or may not positively affect metabolic parameters and quality of life. (1, 2, 3, 4). They don’t seem to cause either major health benefits or major health risks in the medium term, which is the longest term for which there is good data available – for example, they have no effect on cancer rates. Overall they seem solid but unspectacular. But there’s a long way between “low carbohydrate diet” and “stop eating wheat”.

So I was more interested in figuring out what was going on with wheat in particular.

Wheat contains chemicals [citation needed]. The ones that keep cropping up (no pun intended) in these kinds of discussions are phytates, lectins, gluten, gliadin, and agglutinin, the last three of which for your convenience have been given names that all sound alike.

Various claims have been made about these chemicals’ effects on health. These have some prima facie plausibility. Plants don’t want to be eaten [citation needed] and they sometimes fill their grains with toxins to discourage animals from eating them. Ricin, a lectin in the seeds of the castor oil plant so toxic it gets used in chemical warfare, is a pretty good example. Most toxins are less dramatic, and most animals have enzymes that break down the toxins in their preferred food sources effectively. But if humans are insufficiently good at this, maybe because they didn’t evolve to eat wheat, some of these chemicals could be toxic to humans.

On the other hand, this same argument covers every pretty much every grain and vegetable and a lot of legumes – pretty much every plant-based food source except edible fruits. So we need a lot more evidence to start worrying about wheat.

I found the following claims about negative effects of wheat:

1. Some people without celiac disease are nevertheless sensitive to gluten.

2. Wheat increases intestinal permeability, causing a leaky gut and autoimmune disease.

3. Digestion of wheat produces opiates, which get you addicted to wheat.

4. Wheat something something something autism and schizophrenia.

5. Wheat has been genetically modified recently in ways that make it much worse for you.

6. The lectins in wheat interfere with leptin receptors, making people leptin resistant and therefore obese.

I’ll try to look at each of those and then turn to the positive claims made about wheat to see if they’re strong enough to counteract them.

Some People Without Celiac Disease Are Sensitive To Gluten – Mostly true but of limited significance

Celiac disease is one source of concern. Everybody on all sides of the wheat debate agree about the basic facts of this condition, which affects a little less than 1% of the population. They have severe reactions to the gluten in wheat. Celiac disease is mostly marked by gastroentereological complaints – diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain – but it is also associated with vitamin deficiencies, anaemia, skin reactions, infertility, and “malaise”. It can be pretty straightforwardly detected by blood tests and gut biopsies and is not subtle.

People start to disagree about the existence of “gluten sensitivity”, which if it existed would be a bad reaction to gluten even in people who don’t test positive for celiac disease. Many people believe they have gastrointestinal (or other) symptoms that go away when they eat gluten-free diets, but science can’t find anything wrong with their intestines that could be causing the problems.

A recent study somewhat vindicated these people. Biesiekierski 2011 describes a double-blind randomized controlled trial: people who said they had “gluten-sensitive” irritable bowel syndrome were put on otherwise gluten-free diets and then randomly given either gluten or a placebo. They found that the patients given gluten reported symptoms (mostly bowel-related and tiredness) much more than those given placebo (p = 0.0001) but did not demonstrate any of the chemical, immunological, or histological markers usually associated with celiac disease. A similar Italian study found the same thing, except that they did find a higher rate of anti-gluten antibodies in their patients. Another study found that non-celiacs with antibodies to gluten had higher rates of mortality. And another study did find a histological change in bowel barrier function on this group of patients with the introduction of gluten. And another study from the same group found that maybe FODMAPs, another component of wheat, are equally or more responsible.

The journal Gastroenterology, which you may not be surprised to learn is the leading journal in the field of gastroenterology, proclaims:

The current working definition of nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is the occurrence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like symptoms after the ingestion of gluten and improvement after gluten withdrawal from the diet after exclusion of celiac disease based on negative celiac serologies and/or normal intestinal architecture and negative immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated allergy tests to wheat. Symptoms reported to be consistent with NCGS are both intestinal (diarrhea, abdominal discomfort or pain, bloating, and flatulence) and extra-intestinal (headache, lethargy, poor concentration, ataxia, or recurrent oral ulceration). These criteria strongly and conveniently suggest that NCGS is best understood as a subset of IBS or perhaps a closely related but distinct functional disorder. Although the existence of NCGS has been slowly gaining ground with physicians and scientists, NCGS has enjoyed rapid and widespread adoption by the general public.

But even this isn’t really that interesting. Maybe some people with irritable bowel syndrome or certain positive antibodies should try avoiding gluten to see if it helps their specific and very real symptoms. At most ten percent of people are positive antibody testing, and not all of those even have symptoms. That’s still a far cry from saying no one should eat wheat.

But the anti-wheat crowd says an alternative more sensitive antibody test could raise sensitivity as high as a third of the population. The test seems to have been developed by a well-respected and legitimate doctor, but it hasn’t as far as I can tell been submitted for peer review or been confirmed by any other source. Meh.

That’s boring anyway. The real excitement comes from sweeping declarations that the entire population is sensitive to wheat.

Wheat Increases Intestinal Permeability Causing A Leaky Gut – Probably true, of uncertain significance

There are gluten-induced mucosal changes in subjects without small bowel disease. And gliadin increases intestinal permeability in the test tube, which should be extremely concerning to any test tubes reading this.

But probably the bigger worry here are lectins, which include wheat germ agglutinin. WGA affects the intestinal permeability of rats, which should be extremely concerning to any rats reading this. The same substance has been found to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and interfere with the growth of various organs including the gut.

So there’s pretty good evidence that chemicals in wheat can increase intestinal permeability. Who cares?

For years, “leaky gut syndrome” was an alternative medicine diagnosis that was soundly mocked by the mainstream medical establishment. Then the mainstream medical establishment confirmed it existed and did that thing where they totally excused their own mocking of it but were ABSOLUTELY OUTRAGED that the alternative medicine community might have in some cases been overenthusiastic about it.

Maybe I’m being too harsh. The alternative medicine community often does take “leaky gut syndrome” way too far.

On the other hand, it’s probably real and Nature Clinical Practice is now publishing papers saying it is “a key ingredient in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases” and “offers innovative, unexplored approaches for the treatment of these devastating diseases” and gut health has been deemed “a new objective in medicine”. Preliminary changes to intestinal permeability have been found in asthma, in diabetes, and even in depression.

But it’s not yet clear if this is cause and effect. Maybe the stress of having asthma increases intestinal permeability somehow. Or maybe high intestinal permeability causes asthma somehow. It sure seems like the latter might work – all sorts of weird antigens and stuff from food can make it into the bloodstream and alarm the immune system – but right now this is all speculative.

So what we have is some preliminary evidence that wheat increases intestinal permeability, and some preliminary evidence that increased intestinal permeability is bad for you in a variety of ways.

And I don’t doubt that those two facts are true, but my knowledge of this whole area is so weak that I wonder how much to worry.

What other foods increase intestinal permeability? Do they do it more or less than wheat? Has anyone been investigating this? Are there common things that affect intestinal permeability a thousand times more than wheat does, such that everything done by wheat is totally irrelevant in comparison?

Do people without autoimmune diseases suffer any danger from increased intestinal permeability? How much? Is it enough to offset the many known benefits of eating wheat (to be discussed later?) Fiber seems to decrease intestinal permeability and most people get their fiber from bread; would decreasing bread consumption make leaky gut even worse?

I find this topic really interesting, but in a “I hope they do more research” sort of way, not an “I shall never eat bread ever again” sort of way.

Digestion Of Wheat Produces Opiates, Which Get You Addicted To Wheat – Probably false, but just true enough to be weird

Dr. William Davis, a cardiologist, most famously makes this claim in his book Wheat Belly. He says that gliadin (a component of gluten) gets digested into opiates, chemicals similar to morphine and heroin with a variety of bioactive effects. This makes you addicted to food in general and wheat in particular, the same way you would get addicted to morphine or heroin. This is why people are getting fat nowadays – they’re eating not because they’re hungry, but because they’re addicted. He notes that drugs that block opiates make people want wheat less.

Does Wheat Make Us Fat And Sick, a review published in the Journal of Cereal Science (they have journals for everything nowadays) is a good rebuttal to some of Davis’ claims and a good pro-wheat resource in general.

They say that although gliadin does digest into opiates, those opiates are seven unit peptides and so too big to be absorbed from the gut to the bloodstream.

(note that having opiates in your gut isn’t a great idea either since there are lots of nerves there controlling digestion that can be affected by these drugs)

But I’m not sure this statement about absorption is even true. First, large proteins can sometimes make it into the gut. Second, if all that leaky gut syndrome stuff above is right, maybe the gut is unusually permeable after wheat consumption. Third, there have been sporadically reported cases of gliadin-derived opiates found in the urine, which implied they got absorbed somehow.

There’s a better counterargument on the blog The Curious Coconut. She notes that there’s no evidence these peptides can cross the blood-brain barrier, a precondition for having any psychological effects. And although the opiate-blocker naloxone does decrease appetite, this effect is not preferential for wheat, and probably more related to the fact that opiates are the way the brain reminds itself it’s enjoying itself (so that opiate-blocked people can’t enjoy eating as much).

And then there’s the usual absence of qualifiers. Lots of things are “chemically related” to other chemicals without having the same effect; are gliadin-derived opiates addictive? Are they produced in quantities high enough to be relevant in real life? Corn, spinach, and maybe meat can all get digested into opiates – is there any evidence wheat-derived opiates are worse? This is really sketchy.

The most convincing counterargument is that as far as anyone can tell, wheat makes people eat less, not more:

Prospective studies suggest that weight gain and increases in abdominal adiposity over time are lower in people who consume more whole grains. Analyses of the Physicians’ Health Study (27) and the Nurses’ Health Study (26) showed that those who consumed more whole grain foods consistently weighed less than those who consumed fewer whole grain foods at each follow-up period of the study. Koh-Banerjee et al. (27) estimated that for every 40-g increase in daily whole grain intake, the 8-y weight gain was lower by 1.1 kg.

I’ll discuss this in more detail later, but it does seem like a nail in the coffin for the “people eat too much because they’re addicted to wheat” theory.

Still, who would have thought that wheat being digested into opiates was even a little true?

Wheat Something Something Something Autism And Schizophrenia – Definitely weird

Since gluten-free diets get tried for everything, and everything gets tried for autism, it was overdetermined that people would try gluten-free diets for autism.

All three of the issues mentioned above – immune reactivity to gluten, leaky guts, and gliadin-derived opiates – have been suggested as mechanisms for why gluten free diets might be useful in autism.

Of studies that have investigated, a review found that seven reported positive results, four negative results, and two mixed results – but that all of the studies involved were terrible and the ones that were slightly less terrible seemed to be more negative. The authors described this as evidence against gluten-free diets for autism, although someone with the opposite bias could have equally well looked at the same review and described it as supportive.

However, a very large epidemiological study found (popular article, study abstract) that people with antibodies to gluten had three times the incidence of autism spectrum disease than people without, and that the antibodies preceded the development of the condition.

Also, those wheat-derived opioids from the last section – as well as milk-derived opioids called casomorphins – seem to be detected at much higher rates in autistic people.

Both of these factors may have less to do with wheat in particular and more to do with some general dysregulation of peptide metabolism in autism. If for some reason the gut kept throwing peptides into the body inappropriately, this would disrupt neurodevelopment, lead to more peptides in the urine, and give the immune system more chance to react to gluten.

The most important thing to remember here is that it would be really wrong to say wheat might be “the cause” of autism. Most likely people do not improve on gluten-free diets. While there’s room to argue that people might have picked up a small signal of them improving a little, the idea that this totally removes the condition is right out. If we were doing this same study with celiac disease, we wouldn’t be wasting our time with marginally significant results. Besides, we know autism is multifactorial, and we know it probably begins in utero.

Schizophrenia right now is in a similar place. Schizophrenics are five to seven times more likely to have anti-gliadin antibodies as the general population. We can come up with all sorts of weird confounders – maybe antipsychotic medications increase gut permeability? – but that’s a really strong result. And schizophrenics have frank celiac disease at five to ten times the rate of the general population. Furthermore, a certain subset of schizophrenics sees a dramatic reduction in symptoms when put on a strict gluten-free diet (this is psychiatrically useless, both because we don’t know which subset, and because given how much trouble we have getting schizophrenics to swallow one lousy pill every morning, the chance we can get them to stick to a gluten-free diet is basically nil). And like those with autism, schizophrenics show increased levels of weird peptides in their urine.

But a lot of patients with schizophrenia don’t have reactions to gluten, a lot don’t improve on a gluten free diet, and other studies question the research showing that any of them at all do.

The situation here looks a lot like autism – a complex multifactorial process that probably isn’t caused by gluten but where we see interesting things going on in the vague territory of gluten/celiac/immune response/gut permeability/peptides, with goodness only knows which ones come first and which are causal.

Wheat Has Been Genetically Modified Recently In Ways That Make It Much Worse For You – Probably true, especially if genetically modified means “not genetically modified” and “recently” means “nine thousand years ago”

If you want to blame the “obesity epidemic” or “autism epidemic” or any other epidemic on wheat, at some point you have to deal with people eating wheat for nine thousand years and not getting epidemics of these things. Dr. Davis and other wheat opponents have turned to claims that wheat has been “genetically modified” in ways that improve crop yield but also make it more dangerous. Is this true?

Wheat has not been genetically modified in the classic sense, the one where mad scientists with a god complex inject genes from jellyfish into wheat and all of a sudden your bread has tentacles and every time you try to eat it it stings you. But it has been modified in the same way as all of our livestock, crops, and domestic pets – by selective breeding. Modern agricultural wheat doesn’t look much like its ancient wild ancestors.

The Journal Of Cereal Science folk don’t seem to think this is terribly relevant. They say:

Gliadins are present in all wheat lines and in related wild species. In addition, seeds of certain ancient types of tetraploid wheat have even greater amounts of total gliadin than modern accessions…There is no evidence that selective breeding has resulted in detrimental effects on the nutritional properties or health benefits of the wheat grain, with the exception that the dilution of other components with starch occurs in modern high yielding lines (starch comprising about 80% of the grain dry weight). Selection for high protein content has been carried out for bread making, with modern bread making varieties generally containing about 1–2% more protein (on a grain dry weight basis) than varieties bred for livestock feed when grown under the same conditions. However, this genetically determined difference in protein content is less than can be achieved by application of nitrogen fertilizer. We consider that statements made in the book of Davis, as well as in related interviews, cannot be substantiated based on published scientific studies.

In support of this proposition, in the test tube ancient grains were just as bad for celiac patients’ immune systems as modern ones.

And yet in one double-blind randomized-controlled trial, people with irritable bowel syndrome felt better on a diet of ancient grains than modern ones (p lower inflammatory markers and generally better nutritional parameters than people on a modern grain one. Isn’t that interesting?

Even though it’s a little bit weird and I don’t think anyone understands the exact nutrients at work, sure, let’s give this one to the ancient grain people.

The Lectins In Wheat Interfere With Leptin Receptors, Making People Leptin Resistant And Therefore Obese – Currently at “mere assertion” level until I hear some evidence

So here’s the argument. Your brain has receptors for the hormone leptin, which tells you when to stop eating. But “lectin” sounds a lot like “leptin”, and this confuses the receptors, so they give up and tell you to just eat as much as you want.

Okay, this probably isn’t the real argument. But even though a lot of wheat opponents cite the heck out of this theory, the only presentation of evidence I can find is Jonsson et al (2005), which points out that there are a lot of diseases of civilization, they seem to revolve around leptin, something common to civilization must be causing them, and maybe that thing could be lectin.

But civilization actually contains more things than a certain class of proteins found in grains! There’s poor evidence of lectin actually interfering with the leptin receptor in humans. The only piece of evidence they provide is a nonsignificant trend toward more cardiovascular disease in people who eat more whole grains in one study, and as we will see, that is wildly contradicted by all other studies.

This one does not impress me much.

Wheat Is Actually Super Good For You And You Should Have It All The Time – Probably more evidence than the other claims on this list

Before I mention any evidence, let me tell you what we’re going to find.

We’re going to find very, very many large studies finding conclusively that whole grains are great in a lot of different ways.

And we’re not going to know whether it’s at all applicable to the current question.

Pretty much all these studies show that people with some high level of “whole grain consumption” are much healthier than people with some lower level of same. That sounds impressive.

But what none of these studies are going to do a good job ruling out is that whole grain is just funging against refined grain which is even worse. Like maybe the people who report low whole grain consumption are eating lots of refined grain, and so more total grain, and the high-whole-grain-consumption people are actually eating less grain total.

They’re also not going to rule out the universal problem that if something is widely known to be healthy (like eating whole grains) then the same health-conscious people who exercise and eat lots of vegetables will start doing it, so when we find that the people doing it are healthier, for all we know it’s just that the people doing it are exercising and eating vegetables.

That having been said, eating lots of whole grain decreases BMI, metabolic risk factors, fasting insulin, and body weight (1, 2, 3, 4,5.)

The American Society For Nutrition Symposium says:

Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain why whole grain intake may play a role in body weight management. Fiber content of whole grain foods may influence food volume and energy density, gastric emptying, and glycemic response. Whole grains has also been proposed to play an important role in promoting satiety; individuals who eat more whole grain foods may eat less because they feel satisfied with less food. Some studies comparing feelings of fullness or actual food intake after ingestion of certain whole grains, such as barley, oats, buckwheat, or quinoa, compared with refined grain controls indicated a trend toward increased satiety with whole grains. These data are in accordance with analyses determining the satiety index of a large number of foods, which showed that the satiety index of traditional white bread was lower than that of whole grain breads. However, in general, these satiety studies have not observed a reduction in energy intake; hence, further research is needed to better understand the satiety effects of whole grains and their impact on weight management.Whole grains, in some studies, have also been observed to lower the glycemic and insulin responses, affect hunger hormones, and reduce subsequent food intake in adults. Ingestion of specific whole grains has been shown to influence hormones that affect appetite and fullness, such as ghrelin, peptide YY, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide 1, and cholecystokinin. Whole grain foods with fiber, such as wheat bran or functional doses of high molecular weight β-glucans, compared with lower fiber or refined counterparts have been observed to alter gastric emptying rates. Although it is likely that whole grains and dietary fiber may have similar effects on satiety, fullness, and energy intake, further research is needed to elucidate how, and to what degree, short-term satiety influences body weight in all age groups.

Differences in particle size of whole grain foods may have an effect on satiety, glycemic response, and other metabolic and biochemical (leptin, insulin, etc.) responses. Additionally, whole grains have been suggested to have prebiotic effects. For example, the presence of oligosaccharides, RS, and other fermentable carbohydrates may increase the number of fecal bifidobacteria and lactobacilli (49), thus potentially increasing the SCFA production and thereby potentially altering the metabolic and physiological responses that affect body weight regulation.

In summary, the current evidence among a predominantly Caucasian population suggests that consuming 3 or more servings of whole grains per day is associated with lower BMI, lower abdominal adiposity, and trends toward lower weight gain over time. However, intervention studies have been inconsistent regarding weight loss

The studies that combined whole and refined grains are notably fewer. But Dietary Intake Of Whole And Refined Grain Breakfast Cereals And Weight Gain In Men finds that among 18,000 male doctors, those who ate breakfast cereal (regardless of whether it was whole and refined) were less likely to become overweight several years later than those who did not (p = 0.01). A book with many international studies report several that find a health benefit of whole grains, several that find a health benefit of all grains (Swedes who ate more grains had lower abdominal obesity; Greeks who ate a grain-rich diet were less likely to become obese; Koreans who ate a “Westernized” bread-and-dairy diet were less likely to have abdominal obesity) and no studies that showed any positive association between grains and obesity, whether whole or refined.

I cannot find good interventional trials on what happens when a population replaces non-grain with grain.

On the other hand, Dr. Davis and his book Wheat Belly claim:

Typically, people who say goodbye to wheat lose a pound a day for the first 10 days. Weight loss then slows to yield 25-30 pounds over the subsequent 3-6 months (differing depending on body size, quality of diet at the start, male vs. female, etc.)Recall that people who are wheat-free consume, on average, 400 calories less per day and are not driven by the 90-120 minute cycle of hunger that is common to wheat. It means you eat when you are hungry and you eat less. It means a breakfast of 3 eggs with green peppers and sundried tomatoes, olive oil, and mozzarella cheese for breakfast at 7 am and you’re not hungry until 1 pm. That’s an entirely different experience than the shredded wheat cereal in skim milk at 7 am, hungry for a snack at 9 am, hungry again at 11 am, counting the minutes until lunch. Eat lunch at noon, sleepy by 2 pm, etc. All of this goes away by banning wheat from the diet, provided the lost calories are replaced with real healthy foods.”

Needless to say, he has no studies supporting this assertion. But the weird thing is, his message board is full of people who report having exactly this experience, my friends who have gone paleo have reported exactly this experience, and when I experimented with it, I had pretty much exactly this experience. Even the blogger from whom I took some of the strongest evidence criticizing Davis says she had exactly this experience.

The first and most likely explanation is that anecdotal evidence sucks and we should shut the hell up. Are there other, less satisfying explanations?

Maybe completely removing wheat from the diet has a nonlinear effect relative to cutting down on it? For example, in celiac disease there is no such thing as “partially gluten free” – if you have any gluten at all, your disease comes back in full force. This probably wouldn’t explain Dr. Davis’ observation – neither I nor my other wheatless-experimentation friends were as scrupulous as a celiac would have to be. But maybe there’s a nonlinear discrepancy between people who have 75% the wheat of a normal person and 10% the wheat of a normal person?

Maybe there’s an effect where people who like wheat but remove it from the diet are eating things they don’t like, and so eat less of them? But people who don’t like wheat like other stuff, and so eat lots of that?

Maybe wheat in those studies is totally 100% a confounder for whether people are generally healthy and follow their doctor’s advice, and the rest of the doctor’s advice is really good but the wheat itself is terrible?

Maybe cutting out wheat has really positive short-term effects, but neutral to negative long-term effects?

Maybe as usual in these sorts of situations, the simplest explanation is best.

Final Thoughts

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity is clearly a real thing. It seems to produce irritable bowel type symptoms. If you have irritable bowel type symptoms, it might be worth trying a gluten-free diet for a while. But the excellent evidence for its existence doesn’t seem to carry over to the normal population who don’t experience bowel symptoms.

What these people have are vague strands of evidence. Something seems to be going on with autism and schizophrenia – but most people don’t have autism or schizophrenia. The intestinal barrier seems to become more permeable with possible implications for autoimmune diseases – but most people don’t have autoimmune disease. Some bad things seem to happen in rats and test tubes – but most people aren’t rats or test tubes.

You’d have to want to take a position of maximum caution – wheat seems to do all these things, and even though none of them in particular obviously hurt me directly, all of them together make it look like the body just doesn’t do very well with this substance, and probably other ways the body doesn’t do very well with this substance will turn up, and some of them probably affect me.

There’s honor in a position of maximum caution, especially in a field as confusing as nutrition. It would not surprise me if the leaky gut connection turned into something very big that had general implications for, for example, mental health. And then people who ate grain might regret it.

But stack that up against the pro-wheat studies. None of them are great, but they mostly do something the anti-wheat studies don’t: show direct effect on things that are important to you. Most people don’t have autism or schizophrenia, but most people do have to worry about cardiovascular disease. We do have medium-term data that wheat doesn’t cause cancer, or increase obesity, or contribute to diabetes, or any of that stuff, and at this point solely based on the empirical data it seems much more likely to help with those things than hurt.

I hope the role of intestinal permeability in autoimmune disease gets the attention it deserves – and when it does, I might have to change my mind. I hope people stop being jerks about gluten sensitivity, admit it exists, and find better ways to deal with it. And if people find that eliminating bread from their diet makes them feel better or lose weight faster, cool.

But as far as I can tell the best evidence is on the pro-wheat side of things for most people at most times.

[EDIT: An especially good summary of the anti-wheat position is 6 Ways Wheat Can Destroy Your Health. An especially good pro-wheat summary is Does Wheat Make Us Fat And Sick?]

Labour party proposes to start charging separately for healthcare.

the shock of the library: oasis versus all of art and culture

“Unless we can somehow recycle the concept of the great artist so that it supports Chuck Berry as well as it does Marcel Proust, we might as well trash it altogether” — Robert Christgau

“Unless we can somehow recycle the concept of the great artist so that it supports Chuck Berry as well as it does Marcel Proust, we might as well trash it altogether” — Robert Christgau

“But rock criticism does something even more interesting, changing not just our idea of who gets to be an artist but of who gets to be a thinker. And not just who gets to be a thinker, but which part of our life gets to be considered ‘thought’. Say that – using rockers like Chuck and Elvis as intellectual models – young Christgau, Meltzer, Bangs, Marcus et al. grow up to understand that rock ’n’ roll isn’t just what you write about, it’s what you do. It’s your mode of thought. And if you do words on the page, then your behavior on the page doesn’t follow standard academic or journalistic practice, and is baffling for those who expect it to.” –Frank Kogan (responding to Xgau; update: see Frank’s comments below for link to complete piece, or go here)

“People who write and read and review books are fucking putting themselves a tiny little bit above the rest of us who fucking make records and write pathetic little songs for a living.”—Noel Gallagher

Some time in the late 80s or early 90s, I heard a story that may not be true, or anyway may not be fair. I remember it because it’s quite funny, and seemed at the time telling (though I think not in the way I then felt it was). It was told of one-time Kirkaldy-born art-punker turned model turned TV presenter turned film-maker Richard Jobson, and it came to me via two writers very much self-taught as readers and intellectuals, both from more or less working-class backgrounds, both bookish even by my standards (and both unnamed, as I don’t entirely trust my memory for gossip over 25 years, and I don’t want to get them into bother). As Writer2 told it, Writer1 was interviewing Jobson in his home. Making some point about working class cultural heritage and self-education — and his own hungry autodidact fascination with, for example, the War Poets — Jobson had pointed to a large bookcase, full of books: Write1 asked how many he’d actually read. “Well,” said Jobson, “I’ve definitely made sure to read the first page of every one.”

I say 25 years — but I’m not quite sure when this interview took place: The Skids dissolved in 1983; Jobson’s second band, The Armoury Show, lasted until about 1988; not long after it folded, Jobson was riding high as a cultural gatekeeper on TV, a presenter and tastemaker. Certainly it was during this last phase that I *heard* the story — when I took it to be a tale against the kind of television Jobson was involved in; fast-food magazine shows in which everything (fiction, film, art, politics) was self-regardingly skimmed, and converted into this week’s glamourbot accessory. Nothing was ever mastered.

But there was always also a kind of carnival naughtiness about them. What had punk’s original promise been, after all? Let’s start over! Say that everyone’s equal and begin from there! Set all the cultural value-meters back to zero and re-run the entire race, starting now! Here was a return to its energy and levelling allure: here was all culture, and here we all were, barrelling through it all, to enthuse and explore and play and pretend; to learn as well as to gurn; to take what we found and use it as we pleased. And this pleasure of course included playing pranks on the swots of this world, and how they imagine they grasp the world better. There’s a punkily disarming cheek about Jobson’s admission — or boast, or performance, or whatever it is. And an urchin challenge too: I’m a Gemini, not George Steiner, I haven’t read all my books either, maybe more than one page each, but even if we ignore the ones I haven’t quite er begun yet, how much more than one is acceptable, when it isn’t all (and a stiff exam passed). On what page does the authentic cultural capital kick in? I very much trust my boredom.

This idea of the year-zero reset was as adolescent and as silly as it was intoxicating, of course: and as intoxicating as it was old-school. The 1913 Armory Show had been a reset: the New York exhibition that announcing the arrival of the new “modern” art in the USA, a flamboyantly new creative language and attitude. And here was a more or less hitless 80s new wave group — minor league by most accounting — snaffling this legendary name: at once a blatant appeal to high-art authority via fancy reference, and a insolent snook-cocking upturning of same: we name ourselves thus because we are EXACTLY AS IMPORTANT. And even as they rolled their eyes at such an absurd — not to say pretentious — spectacle, all kinds of commentators caught up in punk’s aftermath (“flamboyantly new creative language and attitude”) had placed themselves at the exact same oedipal fork: of course they too want to be urchins running through museums, but there’s also the urge to seek employment as enthusiastic ushers, showing one and all how exactly this (old-school) radical art ought to be understood and used.

And so there was always already a schoolyard-type squabble who gets to be a consider a “thinker”. Rock was always a dramatisation of growing up in public; less a refusal of the demands and changes and skills that school might produce than a theatre of the confused hope of an alternative: combination NO and YES. And we all have to start somewhere: and sometimes you need the goofy and even the deluded elements to help you open up cultural space for what maybe might matter (if only to you): the schoolyard play-acting and grandstanding.

And sometimes it’s a help to have missed the fights on the day, to grasp better where they’re really coming from. I’d left The Wire in early 1994, and really didn’t pay attention to pop for several years — Britpop’s distant alarums were very distant indeed for me; I didn’t engage; I also didn’t get bored; I was teaching myself ancient music history, pretty much. So there’s this cartoon of Be Here Now as mere lout-culture frenzy, driving down all possibility from wider pop of the art of the weird, the queer, the clever, the political, the experimental, the art-school (as Weej more or less puts it on a Popular thread): but coming back at it with a skewed ear, and probably more burnt out on the institutionalised complacency of experiment and avant-garde rebel pose, that’s not really what I hear.

These exhausting seven-minute drone epics all set about with clouds of FX, the the oddly delicate seagulls of reverse-tape guitar: someone should do a compare-and-contrast with Band of Susans! Is Liam’s singing really any less placemarker than Sonic Youth’s? What happens when you recognise the vocals as a basically instrumental elements? Pedal-point noise-roar against quiet integument-backdrops of musique concrete; the deliberately evasive Burroughsian cut-ups in the words: Oasis couldn’t pass an exam on the lineage of any of this — but the mark-grubbing parading of approved non-pop forebears are the problem they intuitively set themselves against. A Gallagher would never hint that he admired any school-approved non-pop mode of aesthetic sensibility — because in that moment he’d see himself become a kind of Manc Momus, the usher of culture stamping on a self-taught council-estate urchin face forever. But of course there are garden-variety avant-gardists also, of a lineage pre-redeemed by chart-topping sales — and plastered with Lennon’s (rather than Yoko’s) face. The clutching at the (dad)rock canon isn’t simply truculent and disastrous, it’s actively misleading. In clinch with the swotty twerp Albarn — well, let’s just say the clash often pushed both sides out towards the worst of themselves. The oddities at the edges of Oasis arrangements seem designed to be drowned out by the dominant lout-stomp; to be treated as ornament. You really have to listen against the main lairy bellow of the sound for the (very) masked musicianly detail. Even a decade later, with their 2008 return-and-farewell Dig Out Your Soul, when you could finally recognise a miniaturist’s mannerist sensibility, a still small connoisseur’s mutter, it’s still mostly framed in maximalist grind, Liam’s chant upfront. Who you never need to listen to twice, to catch anything you didn’t get the first time: a triumphant coarsened framing context from which the arty stuff peeks, in hopeful wait for the aesthetic respect it never quite gets…

Look back at the quote up top, Noel G’s pronouncements about books. It’s natural to see them as anti-book and anti-reading. But look past the anxiety and the aggression, and he isn’t even (quite) saying he’s anti-fiction; he’s saying he’s pro-music-making. To speak in very unGallagherly mode, he’s arguing that the dominant critical hierarchy exalts fiction-making (and those who enjoy the results) over music-making (and those who ditto ditto); but that he (relevantly a music-maker) does not. [Update: as Frank pointed out in comments, my reasoning seemed a bit opaque here -- I had in mind a section on the GQ interview I'd forgotten I hadn't quoted, Noel G contrasting his taste in books with his wife's: “I only read factual books. I can’t think of… I mean, novels are just a waste of f***ing time. I can’t suspend belief in reality… I just end up thinking, ‘This isn’t f***ing true.’ I like reading about things that have actually happened. I’m reading this book at the minute – The Kennedy Tapes. It’s all about the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis – I can get into that.”]

Oasis came up entirely in post-punk time, in age and as industry backdrop: they never had to tussle with prog or whiteblues R&B, or even punk, really. But yes, they too confronted the oedipal fork: for all that it resolves itself in the Oasis-Blur wars — each combatant assigned a clear role — you look a bit harder and it’s right there in the interviews, that patented Gallagher performance, structured as much as anything round a self-loathing sibling rivalry: which brother is the least deluded; which best retains the pap-art [update: POP-art] faith…

A pitch to reassert music-making as a value is everywhere taken — masked as it is in a dogmatic rockcanon doggedness — as an assault on everything other kind of cultural value; the Gallaghers themselves make exactly this mistake. So the Gallaghers may loudly and proudly scorn actually existing higher art; and may insist that rock is properly anti-school, and that are they are properly and heroically anti-intellectual. But this is only true if the “mode of thought” of musicians is cast out from the ordinary understanding of intellect. Somehow, in the 70s, in the 80s, music-as-an-art-in-itself had became cut off from the ordinary trust the rest of the arts still somewhat received. I think it’s right to resist this, and — however inchoately — I think resentment at it is what drives Oasis. Their Oasis — their hubristic triumph, its as-swift collapse into a stupid shadow of itself — was a symptom of this curious situation.

There was never a golden age of countercultural comity of course — at most what there was, within rock, was a brief imagined utopia of progressive quilted fusion (discussed here): punk broke into useless pieces prog’s programme of radical inclusivity (all modes of sound-practice gathered into one stream) and furiously dispersed the fragments; post-punk was the various fragments unblurring and emerging seeminfgly whole in themselves, against a miasmatic background of ambition and doubt (explored somewhat cryptically here). It was at once almost hysterically out-facing (can we not attitudinally master and absorb anything now? from football to fashion to radical politics to avant-garde performance art?) and pervasively jittery with anxiety at the problem of cohesion. Before punk, a kind of anyone-can-do-it hard rock blues sound (guitar and vocal styling) had functioned as the thing “we all” agreed on — the notionally shared tongue, the element that made it all “rock” — into which could be poured anything from country to raga, the music-college swagger and self-belief of prog with the New Deal/Civil Rights/anti-war movement vagueness of hippie politics… After punk, a futile subcultural precession trooped the audition catwalk for the role of countercultural centre: two-tone, goth, rockabilly, afropop and electropop, besuited jazz, revenant psychedelia, post-no wave artnoise… And week after week in the NME, popstars of all kinds sketched out their own individual pan-cultural gallimaufry: Portrait of the Artist as a Consumer.

There was never a golden age of countercultural comity of course — at most what there was, within rock, was a brief imagined utopia of progressive quilted fusion (discussed here): punk broke into useless pieces prog’s programme of radical inclusivity (all modes of sound-practice gathered into one stream) and furiously dispersed the fragments; post-punk was the various fragments unblurring and emerging seeminfgly whole in themselves, against a miasmatic background of ambition and doubt (explored somewhat cryptically here). It was at once almost hysterically out-facing (can we not attitudinally master and absorb anything now? from football to fashion to radical politics to avant-garde performance art?) and pervasively jittery with anxiety at the problem of cohesion. Before punk, a kind of anyone-can-do-it hard rock blues sound (guitar and vocal styling) had functioned as the thing “we all” agreed on — the notionally shared tongue, the element that made it all “rock” — into which could be poured anything from country to raga, the music-college swagger and self-belief of prog with the New Deal/Civil Rights/anti-war movement vagueness of hippie politics… After punk, a futile subcultural precession trooped the audition catwalk for the role of countercultural centre: two-tone, goth, rockabilly, afropop and electropop, besuited jazz, revenant psychedelia, post-no wave artnoise… And week after week in the NME, popstars of all kinds sketched out their own individual pan-cultural gallimaufry: Portrait of the Artist as a Consumer.

The post-punk break-up had seemed an amazing liberation — and it surely helped that so many from the unexpected sides of the tracks were emboldened to let themselves loose among all this high cultural stuff. But (as is often the way of amazing liberations, perhaps) it had quickly clotted into a landscape of jealously embattled fiefdoms and fandoms…

Plight (extrait) from Véronique Mouysset on Vimeo.

Which isn’t the only way. Here’s another story, from 1986, about who gets to be a thinker. The BBC’s Arena was shooting a documentary about a Joseph Beuys installation at the Anthony D’Offay Gallery, Plight: in effect a cave fashioned of rolls of one of Beuys’ signature materials, felt, containing a grand piano, some sheet music with nothing written on it, and some thermometers. (You can see it here and in the top four images here).) It was only just months after the 1984-85 strike ended, and Beuys had expressed an interest in meeting Arthur Scargill, president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Unfortunately, Beuys died shortly after filming began, so the meeting never took place — but, their interest piqued, the documentary-makers decided to follow through (“We liked the idea of bringing together two charismatic figures from completely different worlds and had no idea what the outcome would be,” director Christopher Swayne told me), and invited Scargill to the gallery to comment on the work. He “was terrific,” Swayne continues: ” (…) more sensitive and suggestive than I would have imagined, and the seemingly incongruous conjunction between Bond Street art and a trade union leader gave us a rather surreal scene.” Like Yoko Ono, Beuys was a member of the fluxus group, part-prankster, part-primitivist — and of course (in the UK especially), trawling for responses from voices outside the usual relevant circle of art-savvy suspects can be a risky tactic. There’s suspicion, a stand-off of knowing or philistine scorn — when you’re not sure you know enough to comment, sometimes you lash out; and sometimes when what you know is merely dismissed, you lash back. Overcompensation on either side, and the conversation devolves into mutually spiteful misrepresentations and contempt (“jealously embattled fiefdoms”).

Which isn’t the only way. Here’s another story, from 1986, about who gets to be a thinker. The BBC’s Arena was shooting a documentary about a Joseph Beuys installation at the Anthony D’Offay Gallery, Plight: in effect a cave fashioned of rolls of one of Beuys’ signature materials, felt, containing a grand piano, some sheet music with nothing written on it, and some thermometers. (You can see it here and in the top four images here).) It was only just months after the 1984-85 strike ended, and Beuys had expressed an interest in meeting Arthur Scargill, president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Unfortunately, Beuys died shortly after filming began, so the meeting never took place — but, their interest piqued, the documentary-makers decided to follow through (“We liked the idea of bringing together two charismatic figures from completely different worlds and had no idea what the outcome would be,” director Christopher Swayne told me), and invited Scargill to the gallery to comment on the work. He “was terrific,” Swayne continues: ” (…) more sensitive and suggestive than I would have imagined, and the seemingly incongruous conjunction between Bond Street art and a trade union leader gave us a rather surreal scene.” Like Yoko Ono, Beuys was a member of the fluxus group, part-prankster, part-primitivist — and of course (in the UK especially), trawling for responses from voices outside the usual relevant circle of art-savvy suspects can be a risky tactic. There’s suspicion, a stand-off of knowing or philistine scorn — when you’re not sure you know enough to comment, sometimes you lash out; and sometimes when what you know is merely dismissed, you lash back. Overcompensation on either side, and the conversation devolves into mutually spiteful misrepresentations and contempt (“jealously embattled fiefdoms”).

Beuys talks about the installation here, but famous as he was for explaining pictures to a dead hare, it’s not a very good discussion. This interviewer doesn’t get the right conversation from him; can’t seem to focus on the interesting Beuys does begin to say; perhaps fails even to spot them as such. I can’t find the Arena documentary on the internet, unfortunately: to get a sense of Scargill’s responses I’ve used these three pages, scanned from a book that discusses it (from Theatre and Everyday Life: An Ethics of Performance by Alan Read, pp172-3, publisher Routledge):

Muffled a little by somewhat unfortunate writing, the author nevertheless gives a sense of what also excited the documentary-makers: the fact that this comes across as a cross-exploration of different realms of expertise, Scargill taking the project perfectly seriously, going out of his way to put engaged thought into his response, digging deep into his own adult experience as a miner. In conversation with the art if not the artist, Scargill brings his own knowledge and belief and passion to an an encounter of equals, and a blend of confidence and curiosity. There’s no sense that he feels he isn’t equipped or entitled to be talking about it. We’ve stepped fully out of urchin-time.

“I only listen to music derived or from the 60s. I’m not interested in jazz or hip-hop or whatever’s going round at the minute; indie shit. I don’t loathe it but I don’t listen to it. My education as a songwriter was from listening to the Kinks and the Who and the Beatles. I don’t listen to avant-garde landscapes and think, ‘I could do that.’ I’m not a fan of Brian Eno. It’s Ray Davies, John Lennon and Pete Townshend for me. –Noel Gallagher

“Because our time tends to work with a kind of ideology, they call those things sculpture and paintings visual art. But I think that vision plays only one role and there are twelve other senses at least implied in looking at an artwork (…) If people are training and are really interested in art they could develop more senses. So this is now related to the senses of touching and surely also to seeing. This remains. I am not against vision because it’s one of the most important senses. You have a kind of acoustic effect, because everything is muffled down. Then there is the effect of warmness. As soon as there are more than twenty people in the room the temperature will rise immediately. Then there is the sound as an element muffling away the noise and the sound (…) So I try principally to do this thing further on over the threshold where modern art ends into an area where anthropological art has to start — in all fields of discussion, not only in the art world, be it in medicine, be it in miners’ problems, be it in the information of state and constitution, be it in the money system.” –Joseph Beuys, 1985 (quote reordered to amplify a point)

It would take all the magic out of it to break down ‘I Am the Walrus’ to its basic components. I listen to it and go, ‘It’s fucking amazing; why is it amazing? I don’t know, it just is.’ That’s why I find journalists such joyless fucking idiots. They have to break music down and pull it apart until there’s nothing left, until they know it all; they analyse it down until it’s bland nonsense. They don’t listen to music like the rest of us.” –Noel Gallagher

“I think it’s a bit unfair to erase the contribution of morons to British pop music – Sabbath, Troggs, Animals, Damned etc… Sometimes you need a Lemmy or Lonnie Donegan or John Fogerty figure to stop the intellectuals getting out of hand” — @dsquareddigest (Daniel Davies) on twitter

Step back again. What I’m trying to describe is a choppy and changeable sea of shifting layers, of the sense of authority within the assumed cultural hierarchy — complex in the sense that a lot of moving parts were moving a lot, in very different ways at very different levels, for quite a long time. And to push a little back against the melodramatic attempts of everyone involved (not least the Gallaghers) to simplify it.

A: Begin with Noel’s very hostile response to the way a writer might want to think about music — more as a spur for writing, for telling good (meaning sellable?) stories, than to reflect the needs of the musician. Noel can’t possibly mean that he never pulled apart his own songs, to get at what made them work — to see if they can’t be better. He might mean that such public analysis this is bad practice for a musician — who may well trust instinct and intuition, without ever having the words to explain what he hears or he wants to any non-musician outsider. Straight away it’s difficult to determine what’s punching up and what’s punching down. decision might be acutely hard to make. As much as anything, an official education is the elaboration of a shareable jargon of discussion and exploration between experts; someone talented but untrained may well be acutely aware that the extant jargons aren’t pinpointing or naming or describing precisely what they’re hearing and valuing. Hence: you clam up and trust only yourself and your pals.

B: The root of all “up” and “down”, punching-wise, is class, of course. And however much training and expertise can be a route upo and out, a smart working class kid will always be conscious of the middle class kids round them, with more time and space and money for extra tuition, with connected parents in the same field, with better means to game the system. And not unrelatedly, the line in the UK between the fine and the applied arts has always boiled with resentment (up) and snobbery (down). Routinely, historically, despite movements and revolts to counter it, in most eras it’s never quite enough to be an artisan, a professional craftsperson, a technician — the higher layers of creative respect will remain shut for you. (The genderline in pop is policed by exactly this prejudice.)

C: Age. Post-war, youth had seemed to have a much amplified power to reverse matters. Suddenly only the young had sex, grasped politics, understood the direction the future was arriving from… a position of seeming weakness had become one of saleable (exploitable) pseudo-strength. By the 90s, this had gone stringy and tangled. The potent founding tokens of youth culture were all old or dead; to insist on their continued value was to impose merely parental mores (or worse, the icons and ideations of bad cultural studies). Always there are be new names and pretty teenage faces, sure, but the counter to dadrock can quite soon just be a kind of dizzy, headachey flicker.

D: Back to Beuys for a moment: he’s saying that there are two further hierarchies. The first (which folds back into B and C) is a heirarchy of genre, which is why his work only reaches the top galleries, to make it as respectable art, once it’s been de-fanged and renamed: “sculpture”. The second is a hierarchy of the senses (saying there are 12 of these, rather than the canonic five). The categories of art history and critical theory tend to be highly conservative in effect; even theory that explores and celebrates the revolutionary moment is just stiff with cousins of the “original intent” movement in US constitutional theory. And this second harks back to A: the serried layers of sensual response, in which the visual has pre-eminence, with sound — and powers over it — always assigned a subaltern role.

(Because in the original bookshelf anecdote, right up top, what isn’t anywhere discussed is the large collection of records that was very surely standing quite near Jobson’s bookshelves. Because one of the things that successful musicians have likely done, at quite an early point in life, is to prioritise which archive exactly they’re going to devoting their time to, and learning from. We are all time-poor: this above all was something that punk dramatised — the leisure to mastery as a mark of privilege. But for a period — a period we may or may not yet have moved out of — the self-constructed private archive from out of a vast pool of LPs and 45s (CDs? mp3s?) was at once enormously more accessible and unregimented than gallery art or cinema or even book-learning. The freedom to do it all WRONG — which musical self-education via 45 and 33 very much allowed — was a central element in the sense of liberation that rock had once seemed to offer, and the curious topsy-turvy authority it at first gathered to itself.

E: and finally, very quickly, there’s all the ins and outs and shifting fashions and facts of what functions at any moment as the cultural “outside”. But this is rough notes towards a map and not at all the map itself — even a brief attempt to sketch how jazz or rock, born in black-created sound in a Jim Crow world, operated and evolved once borrowed or replicated elsewhere is going to end up a very long attempt. Because it’s quite complicated.

At any point, the verticality is unlikely to be clear or fixed; anything but. Move just a little and dimensions can reverse, distances can balloon or shrink, perspective can turn itself inside out. And let’s not beat about the bush: Oasis had no clear analytical grasp of all this or any of it, their responses very often purely reactive. It’s what we turn to art or music for — descriptions of ambivalence and complexity — but of course they only trusted themselves, and scorned the tools or even the desire to analyse same. And in this refusal, could never avail themselves of a refreshed context of self-awareness or experiment or outside input — as Lennon did with Yoko Ono.

Arthur Scargill’s argument about art — that there’s an artist in everyone, that something like the strike can bring a fruitful curiosity out in anyone — invokes the confidence that derives from a challenge faced and a fight sustained against odds: if you didn’t see yourself as an equal at some point, you’d always dodge away from fights. And sustained conversations are only possible between equals. The strike failed because the miners were defeated — and surely a loss of the relevant kind of confidence followed this, with all kinds of consequences in education; who it’s for and how. The social upheavals that allowed the rock generation to feel equals and more — even the late odd echoes that set the young siblings of punk against their older brothers and sisters — were not so much the kinds of upheaval that can be defeated or reversed. But of course they were vulnerable to time’s passing and the conflicted precession of generations. Even as late as the 80s, working class kids like Jobson (or less ambiguously, Mark E. Smith) could wage autodidact play-battle with echoes of the counterculture, and foray far beyond the the expectations of their own upbringing, on their own terms. But with the stutterstep of doubt introduced into musicianship as a shared value, and the surrender implied by the sourcing of authority extrinsically to music (in any written school of criticism or theory, for example), the options for similarly confident play couldn’t last beyond the early thrash of joyful contrarian noisemaking for Oasis. Semi-occluded semi-avant-garde musicianly grace notes hidden behind a defensively coarsened pretorian guard of bellow and bar-chord: this is — at worst and best — the hypocrisy-as-tribute that vice pays virtue.

ELTON JOHN – “Candle In The Wind ’97″ / “Something About The Way You Look Tonight”

#774, 20th September 1997

Every Popular entry starts with the same question: why this record? This time it’s especially loud. “Candle In The Wind ‘97” is the highest-selling single of all time in the UK, almost 2 million clear of its nearest competitor. This is as big as pop gets. But “why?” might strike you as a silly question here, because its answer is so obvious: Diana, duh. So reframe it: why Diana?

Every Popular entry starts with the same question: why this record? This time it’s especially loud. “Candle In The Wind ‘97” is the highest-selling single of all time in the UK, almost 2 million clear of its nearest competitor. This is as big as pop gets. But “why?” might strike you as a silly question here, because its answer is so obvious: Diana, duh. So reframe it: why Diana?

The death of Princess Diana is recognisably a global news event, in the way we experience them now: the sudden in-rush of information into a new-made vacuum of speculation; the real-time grapple for meaning; and most of all the flood of public sentiment, deforming the story and becoming the story. It was also inescapable in a way nothing in my lifetime had been. But there are elements which feel very distant, and this single is one of them. It pushed the machineries of pop – literal ones, like CD presses and distribution fans, and metaphorical ones, like the charts – to their limits. HMV stores carried signs warning of a limit of 5 copies per person, and still sold out. There were reports of people buying 50 copies – for a shrine, perhaps, or just because CD singles had briefly become, like flowers and bears, part of a currency of devotion.

And still, because Diana so inconveniently died in the small hours of a Sunday, it felt to me like it arrived at No.1 late, a week after the funeral and two after the death. If its copies sold had been evenly distributed it could have managed months at No.1 – instead it racked up 5 weeks, fewer than Puffy. “Candle In The Wind ‘97” sets itself up to be a tribute that will last, but really it only made sense at the funeral, still in the heat of the story’s first phase: part of a fight about what Diana did or meant, and what her legacy might be.

Narratives overlapped, jostled for attention. Everyone had an agenda, everyone claimed her for it. Tony Blair, mesmerised by unifying figures and great causes, saw her as one – the “people’s princess”. TV news announcers, wrestling the story at its source, spat the word “paparazzi” with sudden, fearful distance. What they dreaded seemed to come true with Earl Spencer’s funeral speech, the ancien regime emerging to set the bloodline and duty of old England against its hateful, media-ridden, fallen reality. Murdoch’s Sun, meanwhile, had seen its opportunity. It raged at the family Diana had detested, damning their reticence. When others were a step behind, wringing their hands at the media for killing Diana, the Sun brazenly took that outrage and turned it into a lever to crack open the rest of Royal Family. The remainder of the Establishment retreated to their diaries, writing in despair of a Britain drowned in sentiment, left stained and sodden by this freak tide of petals, plushies and tears.

Legacy is part of what “Candle In The Wind” was always about – Bernie Taupin’s self-satisfied, sentimental recovery of the real girl beneath a superstar. “Candle In The Wind” is a song that’s angry about how men in Hollywood used and reshaped Norma Jean Baker, but then casually asserts the right of other men – Elton and Bernie – to revise the story and define an “authentic” version of the woman. Even the private life of Marilyn becomes a commodity, to be piously invoked by people who never met her. They all sexualised you, Nice Guy Bernie makes Elton simper – of course that’s not what I’m doing, way back in the obsessive dark of the cinema. Sometime in her teens, Diana Spencer sold her cassette of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road to her friend and flatmate, for 50 pence. She signed it before she handed it over.

A song about a dead woman whose place in our memory gets fought over by a vast establishment on one hand and people who never met her on the other: Taupin’s job here isn’t so much to bring the lyrics of “Candle In The Wind” up to date as to urgently make them less pointedly about Diana. The original “Candle” inevitably haunts this one – not just because it’s too resonant to be smothered, but because it makes it obvious how rushed, overdone, and fatuous the new version is. Forgivably so, perhaps. Elton didn’t know Marilyn but he did know Diana – he might have been at the funeral by right of friendship even if it wasn’t a gig. And compared to the knowing, late-night regrets and ruminations of the original, on “Candle In The Wind ‘97” he sings like he’s in a black suit and tie and nervously fingering the collar. (Flip to the ‘double A-side’ – yeah right – for a useful comparison: that’s what a relaxed Elton sounds like). He sings key words – “GROW in our hearts…the GRACE that PLACED yourself…” – with an unctuous precision. Peak smarm is hit on “now you belong to Heaven”, where Elton sounds like a Sunday School teacher explaining to a 5-year old where Bunny has gone.

For the biggest televised funeral of all time, though, some hyperbole is expected. Taupin certainly doesn’t risk caution – “from a country lost without a soul” sobs the lyric. Behind all this rending of garments, more intriguing touches lurk.

There’s the William Blake reference, for instance – “Your footsteps will always fall here, round England’s greenest hills”, an obvious nod to the verse which has ended up known as “Jerusalem”: “And did those feet in ancient time, walk upon England’s mountains green?”. Blake was referring to the legend that the young Jesus visited Britain, making the reference the closest “Candle In The Wind ‘97” comes to tying up all its vague messianic imagery into an implication that really would be startling. But there’s something more here. “Jerusalem” in its most famous sung arrangement also has currency as an alternative national anthem: it’s what England might have if we finally got rid of the Royal Family. Referencing it in a song for a woman who had stepped outside that family is a very interesting choice.

This reading of “Candle In The Wind ‘97” seems tenuous – but it’s backed up by the version of Diana the song chooses to emphasise. What we’re hearing about is Saint Diana, Our Lady Of The Landmines – placing herself in the grace where lives were torn apart. This was also the version of herself she most enjoyed. I don’t think she was cynical about her good works – while obviously living a life of astonishing privilege, she seems to have been a genuinely kind person, and on the right side of social history on some important issues – but she also knew the extent to which they threatened the monarchy.

One of the ways in which the monarchy managed to survive, retaining its power in an age where things might have gone badly for it, was turning Elizabeth II’s personal talent for rapid intimacy into a defining asset. The Queen, like Bill Clinton, has a famously good memory for faces, names, and small personal details – and this is turned by monarchists into an argument in favour of the whole institution. The Royals are valuable because they work so hard, and have such a bond with their subjects.

Since Divine Right won’t cut it, and the economic case is too grubby and unglamorous, this feels like the most solid defence of the Royals that monarchists have. But fixing a job description to monarchy is a secret attack on its legitimacy. If the job of monarchy simply amounts to empathising with people and remembering their names, then the monarch should be whoever does that job best. Diana’s challenge to the monarchy was that she took its nickname – The Firm – literally. She had been fired by the firm, and like a true entrepreneur she set up her own business as its competitor, disrupting it by doing exactly the same things – touring the world, visiting the poor or sick or industrious – with less protocol and more agility. The ultimate 80s icon was taking 80s politics to its unthinkable conclusion: privatise the monarchy. To do it, she used things the Royal Family could hardly touch – the media; youth; even pop.

This was why Diana’s modest assertion to Martin Bashir that perhaps she might be a princess “in people’s hearts” was such dynamite. What if, she was sweetly suggesting, simple popularity is a higher legitimacy than custom and tradition? This is a destabilising question. It’s the question implied by the NME when it modestly begins, in a paper full of critics, to list the records that sell the most every week. Which brings us back round to the original question: why is this record the biggest-selling single of all time?

Because they’re only based on sales, the British charts are a very crude cultural seismograph, able in their barefaced capitalist simplicity to pick up tremors other methods might smooth over. A colossal global news event should always show up on them, even overload them. But the unprecedented scale of this (really bad and hard to listen to) single’s success goes beyond that. Diana’s entire project – acting as a competitor to the Royal Family based on popularity and affection rather than iron tradition – means that a colossal show of genuine, bottom-up public mourning wasn’t just an inevitable reaction from her fans, it was the right one. And even if “Candle In The Wind ‘97” was a little late by our advanced standards, it was released in time to catch that wave.