Is progress inevitable? Is it natural? Is it fragile? Is it possible? Is it a problematic concept in the first place? Many people are reexamining these kinds of questions as 2016 draws to a close, so I thought this would be a good moment to share the sort-of “zoomed out” discussions the subject that historians like myself are always having.

Is progress inevitable? Is it natural? Is it fragile? Is it possible? Is it a problematic concept in the first place? Many people are reexamining these kinds of questions as 2016 draws to a close, so I thought this would be a good moment to share the sort-of “zoomed out” discussions the subject that historians like myself are always having.

There is a strange doubleness to experiencing an historic moment while being a historian one’s self. I feel the same shock, fear, overload, emotional exhaustion that so many are, but at the same time another me is analyzing, dredging up historical examples, bigger crises, smaller crises, elections that set the fuse to powder-kegs, elections that changed nothing. I keep thinking about what it felt like during the Wars of the Roses, or the French Wars of Religion, during those little blips of peace, a decade long or so, that we, centuries later, call mere pauses, but which were long enough for a person to be born and grow to political maturity in seeming-peace, which only hindsight would label ‘dormant war.’ But then eventually the last flare ended and then the peace was real. But on the ground it must have felt exactly the same, the real peace and those blips. That’s why I don’t presume to predict — history is a lesson in complexity not predictability — but what I do feel I’ve learned to understand, thanks to my studies, are the mechanisms of historical change, the how of history’s dynamism rather than the what next. So, in the middle of so many discussions of the causes of this year’s events (economics, backlash, media, the not-so-sleeping dragon bigotry), and of how to respond to them (petitions, debate, fundraising, art, despair) I hope people will find it useful to zoom out with me, to talk about the causes of historical events and change in general.

Two threads, which I will later bring together. Thread one: progress. Thread two: historical agency.

Part 1: The Question of Progress As Historians Ask It

“How do you discuss progress without getting snared in teleology?” a colleague asked during a teaching discussion. This is a historian’s succinct if somewhat technical way of asking a question which lies at the back of a lot of the questions people are wrestling with now. Progress — change for the better over historical time. The word has many uses (social progress, technological progress), but the reason it raises red flags for historians is the legacy of Whig history, a school of historical thought whose influence still percolates through many of our models of history. Wikipedia has an excellent opening definition of Whig history:

Whig history… presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasize the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. The term is often applied generally (and pejoratively) to histories that present the past as the inexorable march of progress towards enlightenment… Whig history has many similarities with the Marxist-Leninist theory of history, which presupposes that humanity is moving through historical stages to the classless, egalitarian society to which communism aspires… Whig history is a form of liberalism, putting its faith in the power of human reason to reshape society for the better, regardless of past history and tradition. It proposes the inevitable progress of mankind.

Whig history… presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasize the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. The term is often applied generally (and pejoratively) to histories that present the past as the inexorable march of progress towards enlightenment… Whig history has many similarities with the Marxist-Leninist theory of history, which presupposes that humanity is moving through historical stages to the classless, egalitarian society to which communism aspires… Whig history is a form of liberalism, putting its faith in the power of human reason to reshape society for the better, regardless of past history and tradition. It proposes the inevitable progress of mankind.

In other words, this approach presumes a teleology to history, that human societies have always been developing toward some pre-set end state: apple seeds into apple trees, humans into enlightened humans, human societies into liberal democratic paradises.

Some of the problems with this approach are transparent, others familiar to those of my readers who have been engaging with current discourse about the problems/failures/weaknesses of liberalism. But let me unpack some of the other problems, the ones historians in particular worry about.

Developed in the earlier the 20th century, Whig history presents a particular set of values and political and social outcomes as the (A) inevitable and (B) superior end-points of all historical change — political and social outcomes that arise from the Western European tradition. The Eurocentric distortions this introduces are obvious, devaluing all other cultures. But even for a Europeanist like myself, who’s already studying Europe, this approach has a distorting effect by focusing our attentions onto historical moments or changes or people that were “right” or “correct,” that took a step “forward.” When one attempts to write a history using this kind of reasoning, the heroes of this process (the statesman who founded a more liberal-democratic-ish state, the scientist whose invention we still use today, the poet whose pamphlet forwards the cause) loom overlarge in history, receiving too much attention. On the one hand, yes, we need to understand those past figures who are keystones of our present — I teach Plato, and Descartes, and Machiavelli with good reason — but if we study only the keystones, and not the other less conspicuous bricks, we wind up with a very distorted idea of the whole edifice.

Whig history also makes it dangerously easy to stray into placing moral value on those things which advanced the teleologicaly-predetermined future. Such things seem to be “correct” thus “good” thus “better” while those whose elements which did not contribute to this teleological development were “dead ends” or “mistakes” or “wrong” which quickly becomes “bad.” In such a history whole eras can be dismissed as unworthy of study for failing to forward progress (The Middle Ages did great stuff, guys!) while other eras can be disproportionately celebrated for advancing it (The Renaissance did a lot of dumb stuff too!). And, of course, whole regions can be dismissed for “failing” to progress (Africa, Asia) as can sub-regions (Poland, Spain).

To give an example within the realm of intellectual history, teleological intellectual histories very often create the false impression that the only figures involved in a period’s intellectual world were heroes and villains, i.e. thinkers we venerate today, or their nasty bad backwards-looking enemies. This makes it seem as if the time period in question was already just previewing the big debates we have today. Such histories don’t know what to do with thinkers whose ideas were orthogonal to such debates, and if one characterizes the Renaissance as “Faith!” vs. “Reason!” and Marsilio Ficino comes along and says “Let’s use Platonic Reason to heal the soul!” a Whig history doesn’t know what to do with that, and reads it as a “dead end” or “detour.” Only heroes or villains fit the narrative, so Ficino must either become one or the other, or be left out. Teleological intellectual histories also tend to give the false impression that the figures we think are important now were always considered important, and if you bring up the fact that Aristotle was hardly read at all in antiquity and only revived in the Middle Ages, or that the most widely owned author in the Enlightenment was the now-obscure fideist encyclopedist Pierre Bayle, the narrative has to scramble to adopt.

To give an example within the realm of intellectual history, teleological intellectual histories very often create the false impression that the only figures involved in a period’s intellectual world were heroes and villains, i.e. thinkers we venerate today, or their nasty bad backwards-looking enemies. This makes it seem as if the time period in question was already just previewing the big debates we have today. Such histories don’t know what to do with thinkers whose ideas were orthogonal to such debates, and if one characterizes the Renaissance as “Faith!” vs. “Reason!” and Marsilio Ficino comes along and says “Let’s use Platonic Reason to heal the soul!” a Whig history doesn’t know what to do with that, and reads it as a “dead end” or “detour.” Only heroes or villains fit the narrative, so Ficino must either become one or the other, or be left out. Teleological intellectual histories also tend to give the false impression that the figures we think are important now were always considered important, and if you bring up the fact that Aristotle was hardly read at all in antiquity and only revived in the Middle Ages, or that the most widely owned author in the Enlightenment was the now-obscure fideist encyclopedist Pierre Bayle, the narrative has to scramble to adopt.

Teleological history is also prone to “presentism” <= a bad thing, but a very useful term! Presentism is when one’s reading of history is distorted by one’s modern perspective, often through projecting modern values onto past events, and especially past people. An essay about the Magna Carta which projects Enlightenment values onto its Medieval authors would be presentist. So are histories of the Renaissance which want to portray it as a battle between Reason and religion, or say that only Florence and/or Venice had the real Renaissance because they were republics, and only the democratic spirit of republics could foster fruitful, modern, forward-thinking people. Presentism is also rearing its head when, in the opening episodes of the new Medici: Masters of Florence TV series, Cosimo de Medici talks about bankers as the masterminds of society, and describes himself as a job-creator, not the conceptual space banking was in in 1420. Presentism is sometimes conscious, but often unconscious, so mindful historians will pause whenever we see something that feels revolutionary, or progressive, or proto-modern, or too comfortable, to check for other readings, and make triple sure we have real evidence. Sometimes things in the past really were more modern than what surrounded them. I spent many dissertation years assembling vast grids of data which eventually painstakingly proved that Machaivelli’s interest in radical Epicurean materialism was exceptional for his day, and more similar to the interests of peers seventy years in his future than his own generation — that Machiavelli was exceptional and forward-thinking may be the least surprising conclusion a Renaissance historian can come to, but we have to prove such things very, very meticulously, to avoid spawning yet another distorted biography which says that Galileo was fundamentally an oppressed Bill Nye. Hint: Galileo was not Bill Nye; he was Galileo.

These problems, in brief, are why discussions of progress, and of teleology, are red flags now for any historian.

Unfortunately, the bathwater here is very difficult to separate from an important baby. Teleological thinking distorts our understanding of the past, but the Whig approach was developed for a reason. (A) It is important to have ways to discuss historical change over time, to talk about the question of progress as a component of that change. (B) It is important to retain some way to compare societies, or at least to assess when people try to compare societies, so we can talk about how different institutions, laws, or social mores might be better or worse than others on various metrics, and how some historical changes might be positive or negative. While avoiding dangerous narratives of triumphant [insert Western phenomenon here] sweeping through and bringing light to a superstitious and backwards [era/people/place], we also want to be able to talk about things like the eradication of smallpox, and our efforts against malaria and HIV, which are undeniably interconnected steps in a process of change over time — a process which is difficult to call by any name but progress.

So how do historians discuss progress without getting snared in teleology?

And how do I, as a science fiction writer, as a science fiction reader, as someone who tears up every time NASA or ESA posts a new picture of our baby space probes preparing to take the next step in our journey to the stars, how do I discuss progress without getting snared in teleology?

I, at least, begin by being a historian, and talking about the history of progress itself.

Part 2: A Brief History of Progress

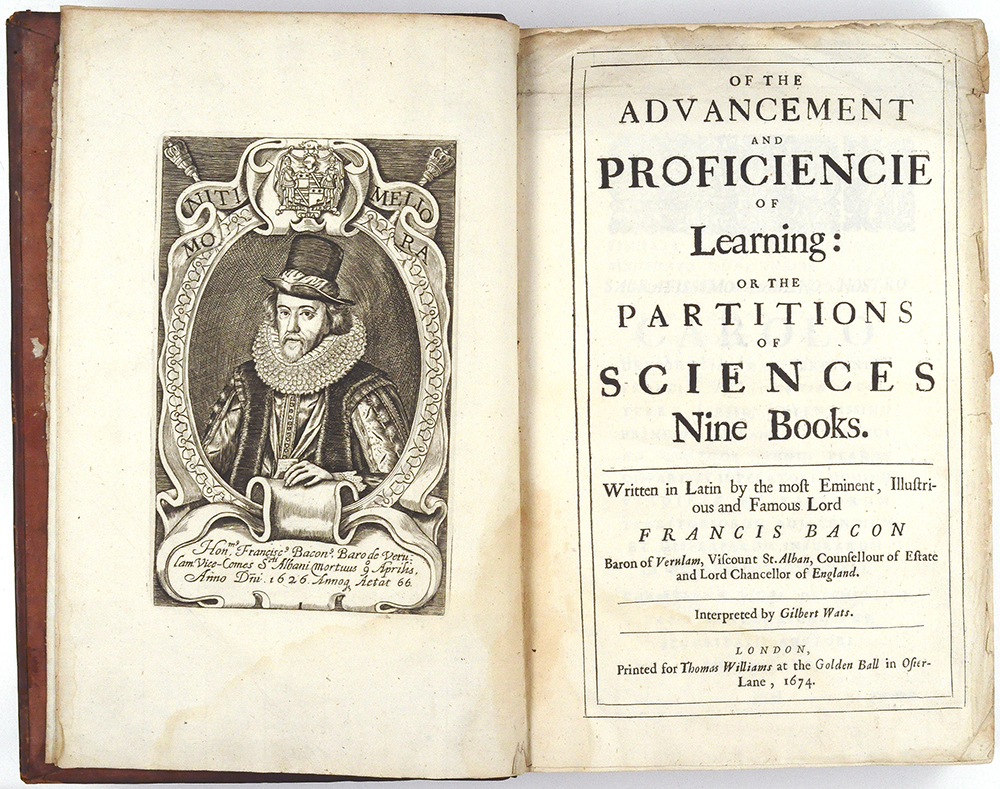

In the early seventeenth century, Francis Bacon invented progress.

Let me unpack that.

Ideas of social change over time had existed in European thought since antiquity. Early Greek sources talk about a Golden Age of peaceful, pastoral abundance, followed by a Silver Age, when jewels and luxuries made life more opulent but also more complicated. There followed a Bronze Age, when weapons and guards appeared, and also the hierarchy of have and have-nots, and finally an Iron Age of blood and war and Troy. Some ancients added more detail to this narrative, notably Lucretius in his Epicurean epic On the Nature of Things. In his version the transition from simple, rural living to luxury-hungry urbanized hierarchy was explicitly developmental, caused, not by divine planning or celestial influences, but by human invention: as people invented more luxuries they then needed more equipment–technological and social — to produce, defend, control, and war over said luxuries, and so, step-by-step, tranquil simplicity degenerated into sophistication and its discontents.

Lucretius’s developmental model of society has several important components of the concept of progress, but not all of them. It has the state of things vary over the course of human history. It also has humanity as the agent of that change, primarily through technological innovation and social changes which arise in reaction to said innovation. It does not have (A) intentionality behind this change, (B) a positive arc to this change, (C) an infinite or unlimited arc to this change, or–perhaps most critically–(D) the expectation that any more change will occur in the future. Lucretius accounts for how society reached its present, and the mythological eras of Gold, Silver, Bronze and Iron do the same. None of these ancient thinkers speculate — as we do every day — about how the experiences of future generations might continue to change and be fundamentally different from their own. Quantitatively things might be different — Rome’s empire might grow or shrink, or fall entirely to be replaced by another — but fundamentally cities will be cities, plows will be plows, empires will be empires, and in a thousand years bread will still be bread. Even if Lucan or Lucretius speculate, they do not live in our world where bread is already poptarts, and will be something even more outlandish in the next generation.

Dante learning about the causes and effects of history… by leaving the Earth entirely and talking to theologians in Heaven about God’s plan. (Spot-the-Saint fans should recognize members of a certain monastic order.)

Medieval Europe came to the realization — and if you grant their starting premises they’re absolutely right — that if the entire world is a temporary construct designed by an omnipotent, omniscient Creator God for the purpose of leading humans through their many trials toward eternal salvation or damnation, then it’s madness to look to Earth history for any cause-to-effect chains, there is one Cause of all effects. Medieval thought is no more monolithic than modern, but many excellent examples discuss the material world as a sort of pageant play being performed for us by God to communicate his moral lessons, and if one stage of history flows into another — an empire rises, prospers, falls — that is because God had a moral message to relate through its progression. Take Dante’s obsession with the Emperor Tiberius, for example. According to Dante, God planned the Crucifixion and wanted His Son to be lawfully executed by all humanity, so the sin and guilt and salvation would be universal, so He created the Roman Empire in order to have there be one government large enough to rule and represent the whole world (remember Dante’s maps have nothing south of Egypt except the Mountain of Purgatory). The empire didn’t develop, it was crafted for God’s purposes, Act II scene iii the Roman Empire Rises, scene v it fulfills its purpose, scene vi it falls. Applause.

Did the Renaissance have progress? No. Not conceptually, though, as in all eras of history, constant change was happening. But the Renaissance did suddenly get closer to the concept too. The Renaissance invented the Dark Ages. Specifically the Florentine Leonardo Bruni invented the Dark Ages in the 1420s-1430s. Following on Petrarch’s idea that Italy was in a dark and fallen age and could rise from it again by reviving the lost arts that had made Rome glorious, Bruni divided history into three sections, good Antiquity, bad Dark Ages, and good Renaissance, when the good things lost in antiquity returned. Humans and God were both agents in this, God who planned it and humans who actually translated the Greek, and measured the aqueducts, and memorized the speeches, and built the new golden age. Renaissance thinkers, fusing ideas from Greece and Rome with those of the Middle Ages, added to old ideas of development the first suggestion of a positive trajectory, but not an infinite one, and not a fundamental one. The change the Renaissance believed in lay in reacquiring excellent things the past had already had and lost, climbing out of a pit back to ground level. That change would be fundamental, but finite, and when Renaissance people talk about “surpassing the ancients” (which they do) they talk about painting more realistic paintings, sculpting more elaborate sculptures, perhaps building more stunning temples/cathedrals, or inventing new clever devices like Leonardo’s heated underground pipes to let you keep your potted lemon tree roots warm in winter (just like ancient Roman underfloor heating!) But cities would be cities, plows would be maybe slightly better plows, and empires would be empires. Surpassing the ancients lay in skill, art, artistry, not fundamentals.

Then in the early seventeenth century, Francis Bacon invented progress.

Bacon visualized the scientific project as the launching of a ship.

If we work together — said he — if we observe the world around us, study, share our findings, collaborate, uncover as a human team the secret causes of things hidden in nature, we can base new inventions on our new knowledge which will, in small ways, little by little, make human life just a little easier, just a little better, warm us in winter, shield us in storm, make our crops fail a little less, give us some way to heal the child on his bed. We can make every generation’s experience on this Earth a little better than our own. There are — he said — three kinds of scholar. There is the ant, who ranges the Earth and gathers crumbs of knowledge and piles them, raising his ant-mound, higher and higher, competing to have the greatest pile to sit and gloat upon–he is the encyclopedist, who gathers but adds nothing. There is the spider, who spins elaborate webs of theory from the stuff of his own mind, spinning beautiful, intricate patterns in which it is so easy to become entwined — he is the theorist, the system-weaver. And then there is the honeybee, who gathers from the fruits of nature and, processing them through the organ of his own being, produces something good and useful for the world. Let us be honeybees, give to the world, learning and learning’s fruits. Let us found a new method — the Scientific Method — and with it dedicate ourselves to the advancement of knowledge of the secret causes of things, and the expansion of the bounds of human empire to the achievement of all things possible.

Bacon is a gifted wordsmith, and he knows how to make you ache to be the noble thing he paints you as.

“How, Chancellor Bacon, do we know that we can change the world with this new scientific method thing, since no one has ever tried it before so you have no evidence that knowledge will yield anything good and useful, or that each generation’s experience might be better than the previous?”

It is not an easy thing to prove science works when you have no examples of science working yet.

Bacon’s answer — the answer which made kingdom and crown stream passionate support and birthed the Academy of Sciences–may surprise the 21st-century reader, accustomed as we are to hearing science and religion framed as enemies. We know science will work–Bacon replied–because of God. There are a hundred thousand things in this world which cause us pain and suffering, but God is Good. He gave the cheetah speed, the lion claws. He would not have sent humanity out into this wilderness without some way to meet our needs. He would not have given us the desire for a better world without the means to make it so. He gave us Reason. So, from His Goodness, we know that Reason must be able to achieve all He has us desire. God gave us science, and it is an act of Christian charity, an infinite charity toward all posterity, to use it.

They believed him.

And that is the first thing which, in my view, fits every modern definition of progress. Francis Bacon died from pneumonia contracted while experimenting with using snow to preserve chickens, attempting to give us refrigeration, by which food could be stored and spread across a hungry world. Bacon envisioned technological progress, medical progress, but also the small social progresses those would create, not just Renaissance glories for the prince and the cathedral, but food for the shepherd, rest for the farmer, little by little, progress. As Bacon’s followers reexamined medicine from the ground up, throwing out old theories and developing…

An immensely sophisticated (and expensive) early 19th-century electrostatic generator. It sure does… demonstrate electrostatics.

I’m going to tangent for a moment. It really took two hundred years for Bacon’s academy to develop anything useful. There was a lot of dissecting animals, and exploding metal spheres, and refracting light, and describing gravity, and it was very, very exciting, and a lot of it was correct, but–as the eloquent James Hankins put it–it was actually the nineteenth century that finally paid Francis Bacon’s I.O.U., his promise that, if you channel an unfathomable research budget, and feed the smartest youths of your society into science, someday we’ll be able to do things we can’t do now, like refrigerate chickens, or cure rabies, or anesthetize. There were a few useful advances (better navigational instruments, Franklin’s lightning rod) but for two hundred years most of science’s fruits were devices with no function beyond demonstrating scientific principles. Two hundred years is a long time for a vastly-complex society-wide project to keep getting support and enthusiasm, fed by nothing but pure confidence that these discoveries streaming out of the Royal Society papers will eventually someday actually do something. I just think… I just think that keeping it up for two hundred years before it paid off, that’s… that’s really cool.

…okay, I was in the middle of a sentence: As Bacon’s followers reexamined science from the ground up, throwing out old theories and developing new correct ones which would eventually enable effective advances, it didn’t take long for his followers to apply his principle (that we should attack everything with Reason’s razor and keep only what stands) to social questions: legal systems, laws, judicial practices, customs, social mores, social classes, religion, government… treason, heresy… hello, Thomas Hobbes. In fact the scientific method that Bacon pitched, the idea of progress, proved effective in causing social change a lot faster than genuinely useful technology. Effectively the call was: “Hey, science will improve our technology! It’s… it’s not doing anything yet, so… let’s try it out on society? Yeah, that’s doing… something… and — Oh! — now the technology’s doing stuff too!” Except that sentence took three hundred years.

But!

We know now, as Bacon’s successors learned, with harsher and harsher vividness in successive generations, that attempts at progress can also cause negative effects, atrocious ones. Like Thomas Hobbes. And the Terror phase of the French Revolution. And the life-expectancy in cities plummeting as industrialization spread soot, and pollutants, and cholera, and mercury-impregnated wallpaper, and lead-whitened bread, Mmmmm lead-whitened bread… And just as technological discoveries had their monstrous offspring, like lead-whitened bread, the horrors of colonization were some of the monstrous offspring of the social applications of Reason. Monstrous offspring we are still wrestling with today.

Part 3: Progresses

We now use the word “progress” in many senses, many more than Bacon and his peers did. There is “technological progress.” There is “social progress.” There is “economic progress.” We sometimes lump these together, and sometimes separate them.

We now use the word “progress” in many senses, many more than Bacon and his peers did. There is “technological progress.” There is “social progress.” There is “economic progress.” We sometimes lump these together, and sometimes separate them.

Thus the general question “Has progress failed?” can mean several things. It can mean, “Have our collective efforts toward the improvement of the human condition failed to achieve their desired results?” This is being asked frequently these days in the context of social progress, as efforts toward equality and tolerance are facing backlash.

But “Has progress failed?” can also mean “Has the development of science and technology, our application of Reason to things, failed to make the lived experience of people better/ happier/ less painful? Have the changes been bad or neutral instead of good?” In other words, was Bacon right that human’s using Reason and science can change our world, but wrong that we can make it better?

I want to stress that it is no small intellectual transformation that “progress” can now be used in a negative sense as well as a positive one. The concept as Bacon crystallized it, and as the Enlightenment spread it, was inherently positive, and to use it in a negative sense would be nonsensical, like using “healing” in a negative sense. But look at how we actually use “progress” in speech today. Sometimes it is positive (“Great progress this year!”) and sometimes negative (“Swallowed up by progress…”). This is a revolutionary change from Bacon’s day, enabled by two differences between ourselves and Bacon.

First we have watched the last several centuries. For us, progress is sometimes the first heart transplant and the footprints on the Moon, and sometimes it’s the Belgian Congo with its Heart of Darkness. Sometimes it’s the annihilation of smallpox and sometimes it’s polio becoming worse as a result of sanitation instead of better. Sometimes it’s Geraldine Roman, the Phillipines’ first transgender congresswoman, and sometimes it’s Cristina Calderón, the last living speaker of the Yaghan language. Progress has yielded fruits much more complex than honey, which makes sentences like “The prison of progress” sensical to us.

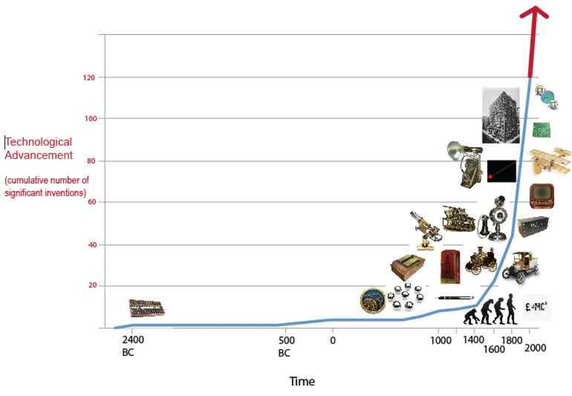

We have also broadened progress. For Bacon, progress was the honey and the honeybees, hard, systematic, intentional human action creating something sweet and useful for mankind. It was good. It was new. And it was intentional. In its nascent form, Bacon’s progress did not differentiate between progress the phenomenon and progress the concept. If you asked Bacon “Was there progress in the Middle Ages?” he would have answered, “No. We’re starting to have progress right now.” And he’s correct about the concept being new, about intentional or self-aware progress, progress as a conscious effort, being new. But if we turn to Wikipedia it defines “Progress (historical)” as “the idea that the world can become increasingly better in terms of science, technology, modernization, liberty, democracy, quality of life, etc.” Notice how agency and intentionality are absent from this. Because there was technological and social change before 1600, there were even technological and social changes that undeniably made things better, even if they came less frequently than they do in the modern world. So the phenomenon we study through the whole of history, far before the maturation of the concept.

We have also broadened progress. For Bacon, progress was the honey and the honeybees, hard, systematic, intentional human action creating something sweet and useful for mankind. It was good. It was new. And it was intentional. In its nascent form, Bacon’s progress did not differentiate between progress the phenomenon and progress the concept. If you asked Bacon “Was there progress in the Middle Ages?” he would have answered, “No. We’re starting to have progress right now.” And he’s correct about the concept being new, about intentional or self-aware progress, progress as a conscious effort, being new. But if we turn to Wikipedia it defines “Progress (historical)” as “the idea that the world can become increasingly better in terms of science, technology, modernization, liberty, democracy, quality of life, etc.” Notice how agency and intentionality are absent from this. Because there was technological and social change before 1600, there were even technological and social changes that undeniably made things better, even if they came less frequently than they do in the modern world. So the phenomenon we study through the whole of history, far before the maturation of the concept.

As “progress” broadened to include unsystematic progress as well as the modern project of progress, that was the moment we acquired the questions “Is progress natural?” and “Is progress inevitable?” Because those questions require progress to be something that happens whether people intend it or not. In a sense, Bacon’s notion of progress wasn’t as teleological as Whig history. Bacon believed that human action could begin the process of progress, and that God gave Reason to humanity with this end in mind, but Bacon thought humans had to use a system, act intentionally, gather the pollen to make the honey, he didn’t think they honey just flowed. Not until progress is broadened to include pre-modern progress, and non-systematic, non-intentional modern progress, can the fully teleological idea of an inescapable momentum, an inevitability, join the manifold implications of the word “progress.”

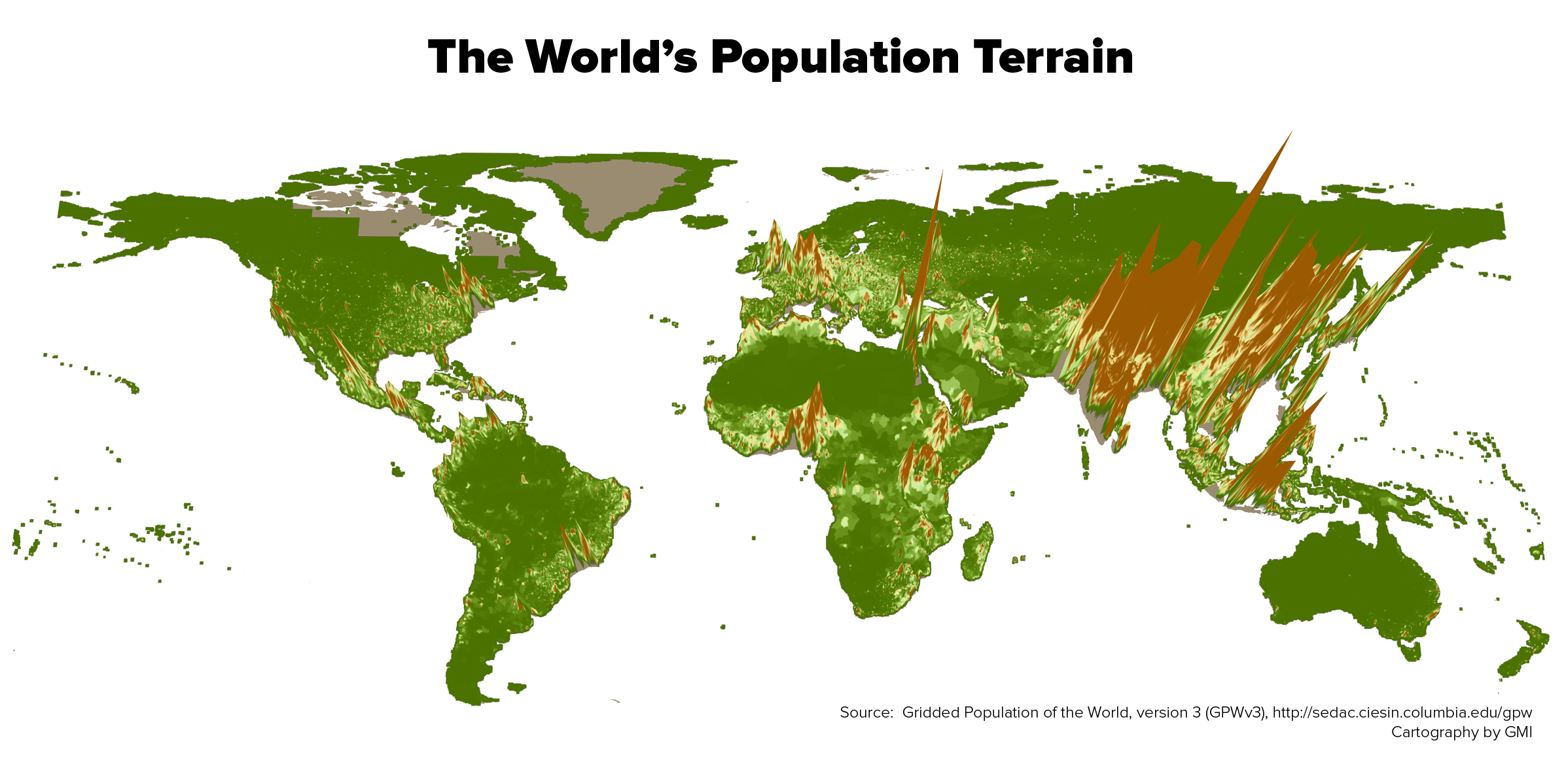

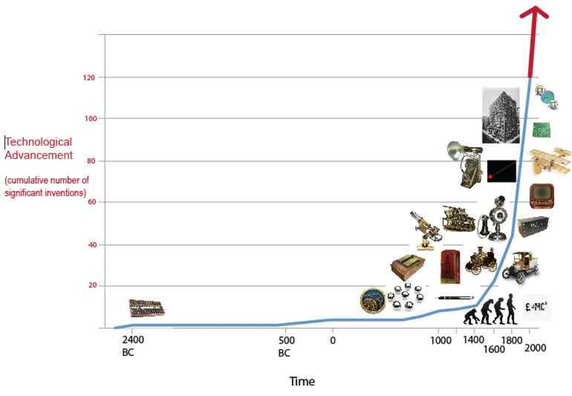

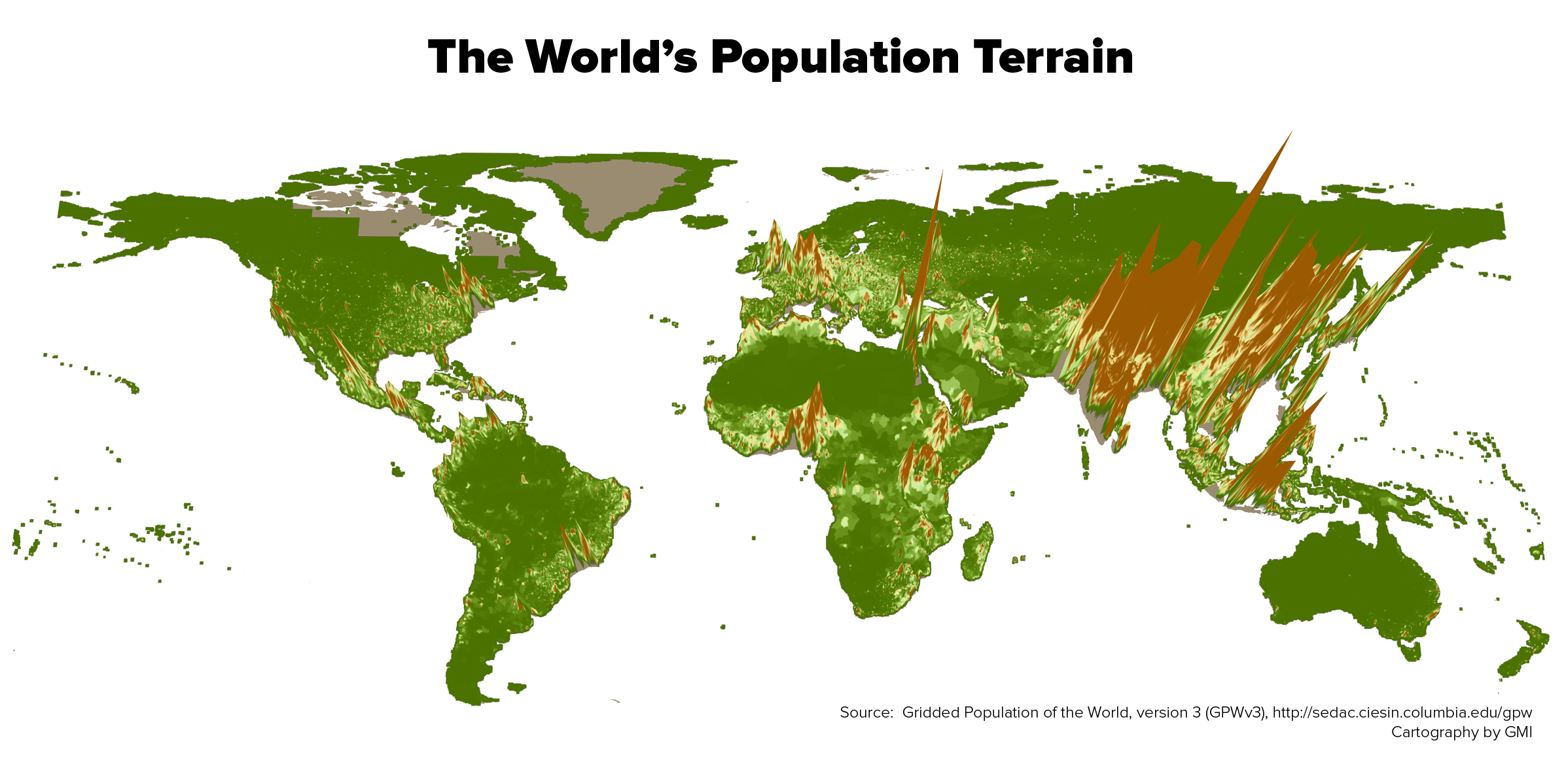

Now I’m going to show you two maps.

This is map of global population, rendered to look like a terrain. It shows the jagged mountain ranges of south and east Asia, the vast, sweeping valleys of forest and wilderness. The most jagged spikes may be a little jarring, the intensity of India and China, but even those are rich brown mountains, while the whole thing has the mood of a semi-untouched world, much more pastoral wilderness than city, and almost everywhere a healthy green. This makes progress, or at least the spread of population, feel like a natural phenomenon, a neutral phenomenon.

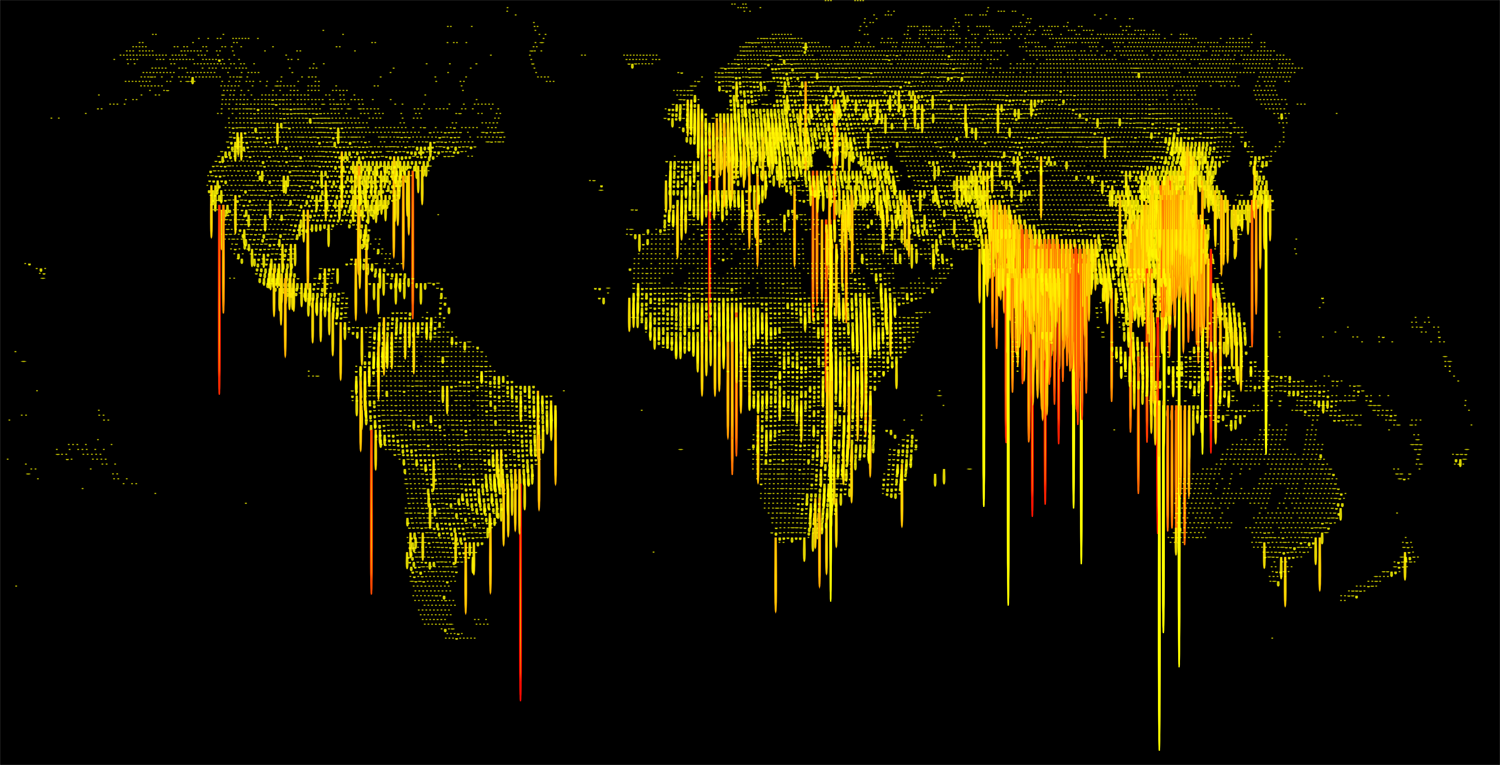

Now:

This is the Human Ooze Map. This map shows exactly the same data, reoriented to drip down instead of spiking up, and to be a pus-like yellow against an ominous black background. Instantly the human metropolises are not natural spikes within a healthy terrain, but an infection clinging to every oozing coastline, with the densest mega-cities seeming to bleed out amidst the goop, like open pustules.

Both these maps show one aspect of ‘progress’. Whether the teeming cities of our modern day are an apocalyptic infection, or a force as natural as the meandering of shores and tree-lines, depends on how we present the narrative, and the moral assumptions that underlie that presentation. Presentism and the progress narrative in general have very similar distorting effects. When we examine past phenomena, institutions, events, people, ideas, some feel viscerally good or viscerally bad, right or wrong, forward-moving or backward-moving, values they acquire from narratives which we ourselves have created, and which orient how we analyze history, just as these mapmakers have oriented population up, or down, resulting in radically different feelings. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s model of the Noble Savage, happier the rural simplicity of Lucretius’s Golden Age rather than in the stressful ever-changing urban world of progress, is itself an image progress presented like the Human Ooze Map, reversing the moral presentation of the same facts.

Realizing that the ways we present data about progress are themselves morally charged can help us clarify questions that are being asked right now about liberalism, and nationalism, and social change, and opposition to social change. Because when we ask whether the world is experiencing a “failure” or a “revolution” or a “regression” or a “backlash” or a “last gasp” or a “pendulum swing” or a “prelude to triumph” etc., all these characterizations reorient data around different facets of the concept of progress, positive or negative, natural or intentional, just as these two maps reorient population around different morally-charged visualizations.

In sum: post colonialism, post industrialization, post Hobbes, we can no longer talk about progress as a unilateral, uncomplicated, good, not without distorting history, and ignoring the terrible facets of the last several centuries. Bacon thought there would be only honey, he was wrong. But we can’t not discuss progress because, during these same centuries, each generation’s experience has been increasingly different from the last generation, and science and human action are propelling this change. And there has been some honey. We need ways to talk about that.

But not without bearing in mind how we invest progress with different kinds of moral weight (the terrain or the ooze…)

And not without a question Bacon never thought to ask, because he did not realize (as we do) that technological and social change had been going on for many centuries before he made the action conscious. So Bacon never thought to ask: Do we have any power over progress?

Part 4: Do Individuals Have the Power to Change History?

Feelings of helplessness and despair have also been big parts of the shock of 2016. Helplessness and despair are questions, as well as feelings. They ask: Am I powerless? Can I personally do anything to change this? Do individuals have any power to shape history? Are we just swept along by the vast tides of social forces? Are we just cogs in the machine? What changes history?

Within a history department this divide often manifests methodologically.

Economic historians, and social historians, write masterful examinations of how vast social and economic forces, and their changes, whether incremental or rapid, have shaped history. Let’s call that Great Forces history. Whenever you hear people comparing our current wealth gap to the eve of the French Revolution, that is Great Forces history. When a Marxist talks about the inevitable interactions of proletariat and bourgeoisie, or when a Whig historian talks about the inevitable march of progress, those are also kinds of Great Forces history.

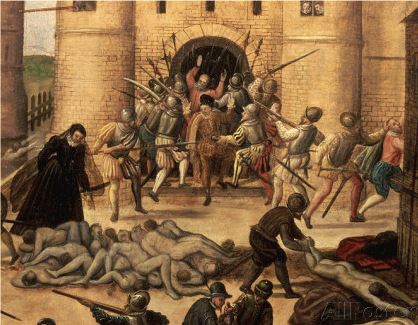

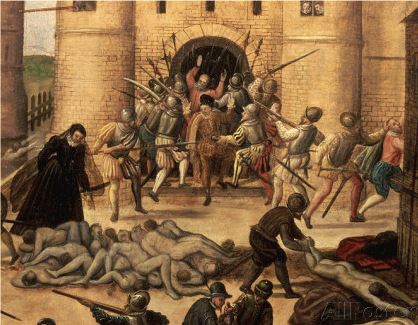

The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, the most infamous of the many bouts of urban violence which characterized the French Wars of Religion

Great Forces history is wonderful, invaluable. It lets us draw illuminating comparisons, and helps us predict, not what will happen but what could happen, by looking at what has happened in similar circumstances. I mentioned earlier the French Wars of Religion, with their intermittent blips of peace. My excellent colleague Brian Sandberg of NIU (a brilliant historian of violence) recently pointed out to me that France during the Catholic-Protestant religious wars was about 10% Protestant, somewhat comparable to the African American population of the USA today which is around 13%. A striking comparison, though with stark differences. In particular, France’s Protestant/Calvinist population fell disproportionately in the wealthy, politically-empowered aristocratic class (comprising 30% of the ruling class), in contrast with African Americans today who fall disproportionately in the poorer, politically-disempowered classes. These similarities and differences make it very fruitful to look at the mechanisms of civil violence in 16th and 17th century France (how outbreaks of violence started, how they ended, who against whom) to help us understand the similar-yet-different ways civil violence might operate around us now. That kind of comparison is, in my view, Great Forces history at its most fruitful. (You can read more by Brian Sandberg on this issue in his book, on his blog, and on the Center for the Study of Religious Violence blog; more citations at the end of this article.)

But are we all, then, helpless water droplets, with no power beyond our infinitesimal contribution to the tidal forces of our history? Is there room for human agency?

History departments also have biographers, and intellectual historians, and micro-historians, who churn out brilliant histories of how one town, one woman, one invention, one idea reshaped our world. Readers have seen me do this here on Ex Urbe, describing how Beccaria persuaded Europe to discontinue torture, how Petrarch sparked the Renaissance, how Machiavelli gave us so much. Histories of agents, of people who changed the world. Such histories are absolutely true — just as the Great Forces histories are — but if Great Forces histories tell us we are helpless droplets in a great wave, these histories give us hope that human agency, our power to act meaningfully upon our world, is real. I am quite certain that one of the causes of the explosive response to the Hamilton musical right now is its firm, optimistic message that, yes, individuals can, and in fact did, reshape this world — and so can we.

History departments also have biographers, and intellectual historians, and micro-historians, who churn out brilliant histories of how one town, one woman, one invention, one idea reshaped our world. Readers have seen me do this here on Ex Urbe, describing how Beccaria persuaded Europe to discontinue torture, how Petrarch sparked the Renaissance, how Machiavelli gave us so much. Histories of agents, of people who changed the world. Such histories are absolutely true — just as the Great Forces histories are — but if Great Forces histories tell us we are helpless droplets in a great wave, these histories give us hope that human agency, our power to act meaningfully upon our world, is real. I am quite certain that one of the causes of the explosive response to the Hamilton musical right now is its firm, optimistic message that, yes, individuals can, and in fact did, reshape this world — and so can we.

This kind of history, inspiring as it is, is also dangerous. The antiquated/old-fashioned/bad version of this kind of history is Great Man history, the model epitomized by Thomas Carlyle’s Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (a gorgeous read) which presents humanity as a kind of inert but rich medium, like agar ready for a bacterial culture. Onto this great and ready stage, Nature (or God or Providence) periodically sends a Great Man, a leader, inventor, revolutionary, firebrand, who makes empires rise, or fall, or leads us out of the black of ignorance. Great Man history is very prone to erasing everyone outside a narrow elite, erasing women, erasing the negative consequences of the actions of Great Men, justifying atrocities as the collateral damage of greatness, and other problems which I hope are familiar to my readers.

But when done well, histories of human agency are valuable. Are true. Are hope.

So if Great Forces history is correct, and useful, and Human Agency history is also correct, and useful… how do we balance that? They are, after all, contradictory.

Part 5: The Papal Election of 2016

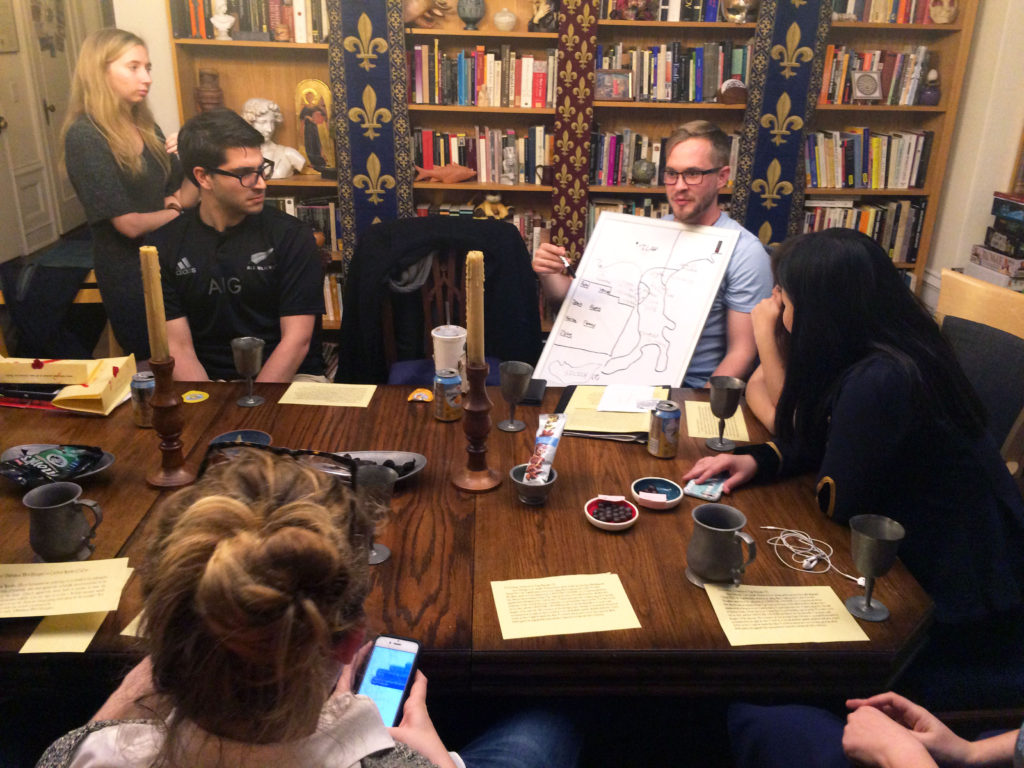

Every year in my Italian Renaissance class, here at the University of Chicago, I run a simulation of a Renaissance papal election, circa 1490-1500. Each student is a different participant in the process, and they negotiate, form coalitions, and, eventually, elect a pope. And then they have a war, and destroy some chunk of Europe. Each student receives a packet describing that students’ character’s goals, background, personality, allies and enemies, and a packet of resources, cards representing money, titles, treasures, armies, nieces and nephews one can marry off, contracts one can sign, artists or scholars one can use to boost one’s influence, or trade to others as commodities: “I’ll give you Leonardo if you send three armies to guard my city from the French.”

Our newly-elected pope crowns the Holy Roman Emperor

Some students in the simulation play powerful Cardinals wielding vast economic resources and power networks, with clients and subordinates, complicated political agendas, and a strong shot at the papacy. Others are minor Cardinals, with debts, vulnerabilities, short-term needs to some personal crisis in their home cities, or long-term hopes of rising on the coattails of others and perhaps being elected three or four popes from now. Others, locked in a secret chamber in the basement, are the Crowned Heads of Europe — the King of France, the Queen of Castile, the Holy Roman Emperor — who smuggle secret orders (text messages) to their agents in the conclave, attempting to forge alliances with Italian powers, and gain influence over the papacy so they can use Church power to strengthen their plans to launch invasions or lay claim to distant thrones. And others are not Cardinals at all but functionaries who count the votes, distribute the food, the guard who keeps watch, the choir director who entertains the churchmen locked in the Sistine, who have no votes but can hear, and watch, and whisper.

There are many aspects to this simulation, which I may someday to discuss here at greater length (for now you can read a bit about it on our History Department blog), but for the moment I just want to talk about the outcomes, and what structures the outcomes. I designed this simulation not to have any pre-set outcome. I looked into the period as best I could, and gave each historical figure the resources and goals that I felt accurately reflected that person’s real historical resources and actions. I also intentionally moved some characters in time, including some Cardinals and political issues which do not quite overlap with each other, in order to make this an alternate history, not a mechanical reconstruction, so that students who already knew what happened to Italy in this period would know they couldn’t have the “correct” outcome even if they tried, which frees everyone to pursue goals, not “correct” choices, and to genuinely explore the range of what could happen without being too locked in to what did. I set up the tensions and the actors to simulate what I felt the situation was when the election begin, then left it free to flow.

I have now run the simulation four times. Each time some outcomes are similar, similar enough that they are clearly locked in by the greater political webs and economic forces. The same few powerful Cardinals are always leading candidates for the throne. There is usually also a wildcard candidate, someone who has never before been one of the top contenders, but circumstances bring a coalition together. And, usually, perhaps inevitably, a juggernaut wins, one of the Cardinals who began with a strong power-base, but it’s usually very, very close. And the efforts of the wildcard candidate, and the coalition that formed around that wildcard, always have a powerful effect on the new pope’s policies and first actions, who’s in the inner circle and who’s out, what opposition parties form, and that determines which city-states rise and which city-states burn as Italy erupts in war.

And the war is Always. Totally. Different.

The new pope meets in secret with his inner circle to plan the conquest of Italy

Because as the monarchies race to make alliances and team up against their enemies, they get pulled back-and-forth by the ricocheting consequences of small actions: a marriage, an insult, a bribe traded for a whisper, someone paying off someone else’s debts, someone taking a shine to a bright young thing. Sometimes France invades Spain. Sometimes France and Spain unite to invade the Holy Roman Empire. Sometimes England and Spain unite to keep the French out of Italy. Sometimes France and the Empire unite to keep Spain out of Italy. Once they made a giant pan-European peace treaty, with a set of marriage alliances which looked likely to permanently unify all four great Crowns, but it was shattered by the sudden assassination of a crown prince.

So when I tell people about this election, and they ask me “Does it always have the same outcome?” the answer is yes and no. Because the Great Forces always push the same way. The strong factions are strong. Money is power. Blood is thicker than promises. Virtue is manipulable. In the end, a bad man will be pope. And he will do bad things. The war is coming, and the land — some land somewhere — will burn. But the details are always different. A Cardinal needs to gather fourteen votes to get the throne, but it’s never the same fourteen votes, so it’s never the same fourteen people who get papal favor, whose agendas are strengthened, whose homelands prosper while their enemies fall. And I have never once seen a pope elected in this simulation who did not owe his victory, not only to those who voted, but to one or more of the humble functionaries, who repeated just the right whisper at just the right moment, and genuinely handed the throne to Monster A instead of Monster B. And from that functionary flow the consequences. There are always several kingmakers in the election, who often do more than the candidate himself to get him on the throne, but what they do, who they help, and which kingmaker ends up most favored, most influential, can change a small war in Genoa into a huge war in Burgundy, a union of thrones between France and England into another century of guns and steel, or determine which decrees the new pope signs. That sometimes matters more than whether war is in Burgundy or Genoa, since papal signatures resolve questions such as: Who gets the New World? Will there be another crusade? Will the Inquisition grow more tolerant or less toward new philosophies? Who gets to be King of Naples? These things are different every time, though shaped by the same forces.

As war wracks Italy and Spain, Cardinals petition the pope to forgive their offenses and condemn their enemies.

Frequently the most explosive action is right after the pope is elected, after the Great Forces have thrust a bad man onto Saint Peter’s throne, and set the great and somber stage for war, often that’s the moment that I see human action do most. That’s when I get the after-midnight message on the day before the war begins: “Secret meeting. 9AM. Economics cafe. Make sure no one sees you. Sforza, Medici, D’Este, Dominicans. Borgia has the throne but he will not be master of Italy.” And together, these brave and haste-born allies, they… faicceed? Fail and succeed? They give it all they have: diplomacy, force, wealth, guile, all woven together. They strike. The bad pope rages, sends forces out to smite these enemies. The kings and great thrones take advantage, launch invasions. The armies clash. One of the rebel cities burns, but the other five survive, and Borgia (that year at least) is not Master of Italy.

We feel it, the students as myself, coming out of the simulation. The Great Forces were real, and were unstoppable. The dam was about to break. No one could stop it. But the human agents — even the tiniest junior clerk who does the paperwork — the human agents shaped what happened, and every action had its consequences, imperfect, entwined, but real. The dam was about to break, but every person there got to dig a channel to try to direct the waters once they flowed, and that is what determined the real shape of the flood, its path, its damage. No one controlled what happened, and no one could predict what happened, but those who worked hard and dug their channels, most of them succeeded in diverting most of the damage, achieving many of their goals, preventing the worst. Not all, but most.

And what I see in the simulation I also see over and over in real historical sources.

This is how both kinds of history are true. There are Great Forces. Economics, class, wealth gaps, prosperity, stagnation, these Great Forces make particular historical moments ripe for change, ripe for war, ripe for wealth, ripe for crisis, ripe for healing, ripe for peace. But individuals also have real agency, and our actions determine the actual consequences of these Great Forces as they reshape our world. We have to understand both, and study both, and act on the world now remembering that both are real.

So, can human beings control progress? Yes and no.

Part 6: Ways to Talk About Progress in the 21st Century

My favorite fish, Orochimaru, a beautiful black veil tail angel. He has long since, as we say in my household “gone the way of all fish.”

Few things have taught me more about the world than keeping a fish tank.

You get some new fish, put them in your fish tank, everything’s fine. You get some more new fish, the next morning one of them has killed almost all the others. Another time you get a new fish and it’s all gaspy and pumping its gills desperately, because it’s from alkeline waters and your tank is too acidic for it. So you put in a little pH adjusting powder and… all the other fish get sick from the Ammonia that releases and die. Another time you get a new fish and it’s sick! So you put fish antibiotics in the water, aaaand… they kill all the symbiotic bacteria in your filter system and the water gets filled with rotting bacteria, and the fish die. Another time you do absolutely nothing, and the fish die.

What’s happening? The same thing that happened in the first two centuries after Francis Bacon, when the science was learning tons, but achieving little that actually improved daily life. The system is more complex than it seems. A change which achieves its intended purpose also throws out-of-whack vital forces you did not realize were connected to it. The acidity buffer in the fish tank increases the nutrients in the water, which causes an algae bloom, which uses up the oxygen and suffocates the catfish. The marriage alliance between Milan and Ferrara makes Venice friends with Milan, which makes Venice’s rival Genoa side with Spain, which makes Spain reluctant to anger Portugal, which makes them agree to a marriage alliance, and then Spain is out of princesses and can’t marry the Prince of Wales, and the next thing you know there are soldiers from Scotland attacking Bologna. A seventeenth-century surgeon realizes that cataracts are caused by something white and opaque appearing at the front of the eye so removes it, not yet understanding that it’s the lens and you really need it.

The One Laptop Per Child program may be the single initiative in Earth’s history-so-far which will trigger the most cultural change. We have no idea what the real effects will be, only that they will be massive. Will they be good? Yes. Bad? Realistically also yes — a mixture, as with all great changes.

So when I hear people ask “Has social progress has failed?” or “Has liberalism failed?” or “Has the Civil Rights Movement failed?” my zoomed-in self, my scared self, the self living in this crisis feels afraid and uncertain, but my zoomed-out self, my historian self answers very easily. No. These movements have done wonders, achieved tons! But they have also done what all movements do in a dynamic historical system: they have had large, complicated consequences. They have added something to the fish tank. Because the same Enlightenment impulse to make a better, more rational world, where everyone would have education and equal political empowerment BOTH caused the brutalities of the Belgian Congo AND gave me the vote. And that’s the sort of thing historians look at, all day.

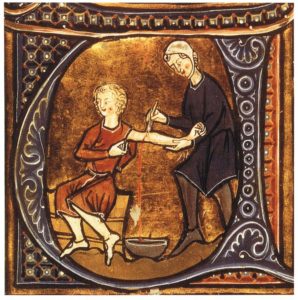

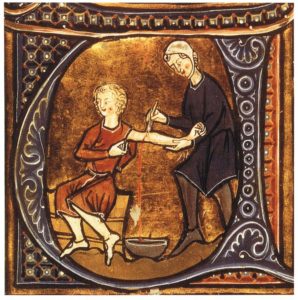

Medieval bloodletting. Something we have genuinely, usefully improved on!

But if the consequences of our actions are completely unpredictable, would it be better to say that change is real but progress controlled by humans is just an idea which turned out to be wrong? No. I say no. Because I gradually got better at understanding the fish tank. Because the doctors gradually figured out how the eye really does function. Because some of our civil rights have come by blood and war, and others have come through negotiation and agreement. Because we as humans are gradually learning more about how our world is interconnected, and how we can take action within that interconnected system. And by doing so we really have achieve some of what Francis Bacon and his followers waited for through those long centuries: we have made the next generation’s experience on this Earth a little better than our own. Not smoothly, and not quickly, but actually. Because, in my mock papal election, the dam did break, but those students who worked hard to dig their channels did direct the flood, and most of them managed to achieve some of what they aimed at, though they always caused some other effects too.

Is it still blowing up in our faces?

Yes.

Is it going to keep blowing up in our faces, over and over?

Yes.

Is it going to blow up so much, sometimes, that it doesn’t seem like it’s actually any better?

Yes.

Is that still progress?

Yes.

Why?

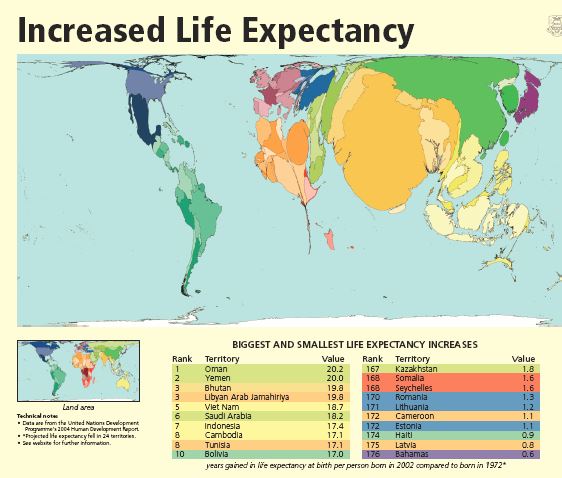

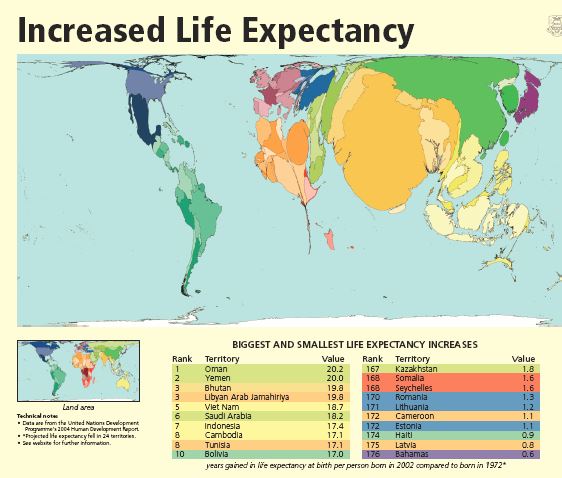

Map of the world by increases in life expectancy since 1972. One of many attempts to create new, better metrics for discussing progress.

Because there was a baby in the bathwater of Whig history. If we work hard at it, we can find metrics for comparing times and places which don’t privilege particular ideologies. Metrics like infant mortality. Metrics like malnutrition. Metrics like the frequency of massacres. We can even find metrics for social progress which don’t irrevocably privilege a particular Western value system. One of my favorite social progress metrics is: “What portion of the population of this society can be murdered by a different portion of the population and have the murderer suffer no meaningful consequences?” The answer, for America in 2017, is not 0%. But it’s also not 90%. That number has gone down, and is now far below the geohistorical norm. That is progress. That, and infant mortality, and the conquest of smallpox. These are genuine improvements to the human condition, of the sort that Bacon and his followers believed would come if they kept working to learn the causes and secret motions of things. And they were right. While Whig history privileges a very narrow set of values, metrics which track things like infant mortality, or murder with impunity, still privilege particular values — life, justice, equality — but aim to be compatible with as many different cultures, and even time periods, as possible. They are metrics which stranded time travelers would find it fairly easy to explain, no matter where they were dumped in Earth’s broad timeline. At least that’s our aim. And such metrics are the best tool we have at present to make the comparisons, and have the discussions about progress, that we need to have to grapple with our changing world.

Because progress is both a concept and a phenomenon.

The concept is the hope that collective human effort can make every generation’s experience on this Earth a little better than the previous generation’s. That concept has itself become a mighty force shaping the human experience, like communism, iron, or the wheel. It is valuable thing to look at the effects that concept has had, to talk about how some have been destructive and others constructive, and to study, from a zoomed-out perspective, the consequences, successes, and failures of different movements or individuals who have acted in the name of progress.

The phenomenon is also real. My own personal assessment of it is just that, a personal assessment, with no authority beyond some years spent studying history. I hope to keep reexamining and improving this assessment all the days of my life. But here at the beginning of 2017 I would say this:

The phenomenon is also real. My own personal assessment of it is just that, a personal assessment, with no authority beyond some years spent studying history. I hope to keep reexamining and improving this assessment all the days of my life. But here at the beginning of 2017 I would say this:

Progress is not inevitable, but it is happening.

It is not transparent, but it is visible.

It is not safe, but it is beneficial.

It is not linear, but it is directional.

It is not controllable, but it is us. In fact, it is nothing but us.

Progress is also natural, in my view, not in the sense that it will inevitably triumph over its doomed opposition, but in the sense that the human animal is part of nature, so the Declaration of the Rights of Man is as natural as a bird’s nest or a beaver dam. There is no teleology, no inevitable correct ending locked in from time immemorial. But I personally think there is a certain outcome to progress, gradual but certain: the decrease of pain in the human condition over time. Because there is so much desire in this world to make a better one. Bacon was right that we ache for it. And the real measurable changes we have made show that he was also right that we can use Reason and collective effort to meet our desires, even if the process is agonizingly slow, imperfect, and dangerous. But we know now how to go about learning the causes and secret motions of things. And how to use that knowledge.

We are also learning to understand the accidental negative consequences of progress, looking out for them, mitigating them, preventing them, creating safety nets. We’re getting better at it. Slowly, but we are.

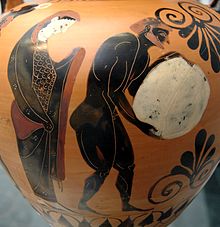

Sisyphus, depicted on a classical urn. Still a very useful way of describing how progress often feels.

Zooming back in hurts. It’s easy to say “the French Wars of Religion” and erase the little blips of peace, but it’s hard to feel fear and pain, or watch a friend feel fear and pain. Sometimes I hear people say they think that things today are worse than they’ve ever been, especially the hate, or the race relations in the USA, that they’re worse now than ever. That we’ve made no progress, quite the opposite. Similarly, I think a person who grew up during one of the peaceful pauses in the French Wars of Religion might say, when the violence restarted, that the wars were worse now than they had ever been, and farther than ever from real peace. They aren’t actually worse now. They genuinely were worse before. But they are really, really bad right now, and it does really, really hurt.

The slowness of social progress is painful, I think especially because it’s the aspect of progress that seemed it would come fastest. During that first century, when Bacon’s followers were waiting in maddening impatience for their better medical knowledge to result in any actual increase in their ability to save lives, social progress was already working wonders. The Enlightenment did extend franchise, end torture on an entire continent, achieved much, and had this great, heady, explosive feeling of victory and momentum. It seemed like social progress was already half-way-done before tech even got started. But Charles Babbage kicked off programmable computing in 1833 and now my pocket contains 100x the computing power needed to get Apollo XI to the Moon, so why, if Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Citizen in 1791, do we still not have equal pay?

Because society is a very complicated fish tank. Because we still have a lot to learn about the causes and secret motions of society.

But if there is a dam right now, ready to break and usher in a change, Great Forces are still shaped by human action. Our action.

Studying history has proved to me, over and over, that things used to be worse. That they are better now. Progress is real. That’s a consolation, but a hollow one while we’re still here facing the pain. What fills its hollowness, for me at least, is remembering that secret meeting in the Economics cafe, that hasty plan, diplomacy, quick action — not a second chance after the disaster, but a next chance. And a next. And a next, to take actions that really did achieve things, even if not everything. Human action combining with the flood is not powerlessness. And that’s how I think progress really works.

Map of the Earth showing online social interaction between cities, 2016.

And as promised, more citations on the demographics of religious violence in France, with thanks to Brian Sandberg:

- Brian Sandberg, Warrior Pursuits: Noble Culture and Civil Conflict in Early Modern France (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

- Philip Benedict, “The Huguenot Population of France, 1600-85,” in The Faith and Fortunes of France’s Huguenots, 1600-85 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), 39-42, 92-95.

- Arlette Jouanna, La France du XVIe siècle, 1483-1598 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996), 325-340.

- Jacques Dupâquier, ed., De la Renaissance à 1789, vol. 2 of Histoire de la population française (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1988), 81-94.

- Historical Perspectives – Brian Sandberg’s blog

- Center for the Study of Religious Violence blog

Is progress inevitable? Is it natural? Is it fragile? Is it possible? Is it a problematic concept in the first place? Many people are reexamining these kinds of questions as 2016 draws to a close, so I thought this would be a good moment to share the sort-of “zoomed out” discussions the subject that historians like myself are always having.

Is progress inevitable? Is it natural? Is it fragile? Is it possible? Is it a problematic concept in the first place? Many people are reexamining these kinds of questions as 2016 draws to a close, so I thought this would be a good moment to share the sort-of “zoomed out” discussions the subject that historians like myself are always having. Whig history… presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasize the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. The term is often applied generally (and pejoratively) to histories that present the past as the inexorable march of progress towards enlightenment… Whig history has many similarities with the Marxist-Leninist theory of history, which presupposes that humanity is moving through historical stages to the classless, egalitarian society to which communism aspires… Whig history is a form of liberalism, putting its faith in the power of human reason to reshape society for the better, regardless of past history and tradition. It proposes the inevitable progress of mankind.

Whig history… presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasize the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. The term is often applied generally (and pejoratively) to histories that present the past as the inexorable march of progress towards enlightenment… Whig history has many similarities with the Marxist-Leninist theory of history, which presupposes that humanity is moving through historical stages to the classless, egalitarian society to which communism aspires… Whig history is a form of liberalism, putting its faith in the power of human reason to reshape society for the better, regardless of past history and tradition. It proposes the inevitable progress of mankind. To give an example within the realm of intellectual history, teleological intellectual histories very often create the false impression that the only figures involved in a period’s intellectual world were heroes and villains, i.e. thinkers we venerate today, or their nasty bad backwards-looking enemies. This makes it seem as if the time period in question was already just previewing the big debates we have today. Such histories don’t know what to do with thinkers whose ideas were orthogonal to such debates, and if one characterizes the Renaissance as “Faith!” vs. “Reason!” and Marsilio Ficino comes along and says “Let’s use Platonic Reason to heal the soul!” a Whig history doesn’t know what to do with that, and reads it as a “dead end” or “detour.” Only heroes or villains fit the narrative, so Ficino must either become one or the other, or be left out. Teleological intellectual histories also tend to give the false impression that the figures we think are important now were always considered important, and if you bring up the fact that Aristotle was hardly read at all in antiquity and only revived in the Middle Ages, or that the most widely owned author in the Enlightenment was the now-obscure fideist encyclopedist

To give an example within the realm of intellectual history, teleological intellectual histories very often create the false impression that the only figures involved in a period’s intellectual world were heroes and villains, i.e. thinkers we venerate today, or their nasty bad backwards-looking enemies. This makes it seem as if the time period in question was already just previewing the big debates we have today. Such histories don’t know what to do with thinkers whose ideas were orthogonal to such debates, and if one characterizes the Renaissance as “Faith!” vs. “Reason!” and Marsilio Ficino comes along and says “Let’s use Platonic Reason to heal the soul!” a Whig history doesn’t know what to do with that, and reads it as a “dead end” or “detour.” Only heroes or villains fit the narrative, so Ficino must either become one or the other, or be left out. Teleological intellectual histories also tend to give the false impression that the figures we think are important now were always considered important, and if you bring up the fact that Aristotle was hardly read at all in antiquity and only revived in the Middle Ages, or that the most widely owned author in the Enlightenment was the now-obscure fideist encyclopedist

We now use the word “progress” in many senses, many more than Bacon and his peers did. There is “technological progress.” There is “social progress.” There is “economic progress.” We sometimes lump these together, and sometimes separate them.

We now use the word “progress” in many senses, many more than Bacon and his peers did. There is “technological progress.” There is “social progress.” There is “economic progress.” We sometimes lump these together, and sometimes separate them. We have also broadened progress. For Bacon, progress was the honey and the honeybees, hard, systematic, intentional human action creating something sweet and useful for mankind. It was good. It was new. And it was intentional. In its nascent form, Bacon’s progress did not differentiate between progress the phenomenon and progress the concept. If you asked Bacon “Was there progress in the Middle Ages?” he would have answered, “No. We’re starting to have progress right now.” And he’s correct about the concept being new, about intentional or self-aware progress, progress as a conscious effort, being new. But if we turn to

We have also broadened progress. For Bacon, progress was the honey and the honeybees, hard, systematic, intentional human action creating something sweet and useful for mankind. It was good. It was new. And it was intentional. In its nascent form, Bacon’s progress did not differentiate between progress the phenomenon and progress the concept. If you asked Bacon “Was there progress in the Middle Ages?” he would have answered, “No. We’re starting to have progress right now.” And he’s correct about the concept being new, about intentional or self-aware progress, progress as a conscious effort, being new. But if we turn to

History departments also have biographers, and intellectual historians, and micro-historians, who churn out brilliant histories of how one town, one woman, one invention, one idea reshaped our world. Readers have seen me do this here on Ex Urbe, describing how

History departments also have biographers, and intellectual historians, and micro-historians, who churn out brilliant histories of how one town, one woman, one invention, one idea reshaped our world. Readers have seen me do this here on Ex Urbe, describing how

The phenomenon is also real. My own personal assessment of it is just that, a personal assessment, with no authority beyond some years spent studying history. I hope to keep reexamining and improving this assessment all the days of my life. But here at the beginning of 2017 I would say this:

The phenomenon is also real. My own personal assessment of it is just that, a personal assessment, with no authority beyond some years spent studying history. I hope to keep reexamining and improving this assessment all the days of my life. But here at the beginning of 2017 I would say this: