Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

1901: 'The First Men in the Moon' by HG Wells

"The Global Race": Bad politics, bad economics

I am pleased to see a prominent Lib Dem producing a book - there should be more of them - and the party's ideology is so nebulous that it is hard to accuse any of us of heresy.

But there are two things that make we worry.

The first is the publisher. I did subscribe to Reform's e-bulletin for a while, but did not get on with it. Its answer to every question was the same: cut taxes, cut spending, privatise.

It was not so much that the bulletin was wrong: it was that it was not interesting.

Still, Jeremy's book may be an exception to Reform's usual output.

But I am not hopeful. "The Global Race"?

I wrote a post back in September of last year quoting a couple of commentators who thought the concept was pretty worthless.

In particular, I quoted Philip Booth from the equally free-market Institute of Economic Affairs and the more left-leaning American economist Robert Reich, via a Guardian article by Andy Beckett:

"Economists don't think of trade as a race in any way," says Booth. "The world economy is not a zero-sum game. Countries get richer together. If China carries on reforming and growing, there will be more opportunities there for Britain." Reich agrees: "The race needn't [mean that] every country's citizens lose ground, but some lose more than others … or [that] some can gain only at the expense of others … We can all grow, and at the same time spread prosperity to more people."Nor is "The Global Race" a novel concept. Back in February 2013 Isabel Hardman told us:

The Cabinet met this morning to discuss the content of the next Queen’s Speech. The ministers present were told that legislation for the next session would focus on supporting the government’s priorities of ‘economic competitiveness’ and Britain’s position in the ‘global race’ (there we go), and ‘aspirations and fairness’.

CCHQ staffers have already told me they’re sick of the phrase, which probably means it’s only just percolated as far as Portcullis House, so expect to hear it coming out too far and too fast from ministers’ mouths over the next few months.The problem is not even that "The Global Race" is a Conservative concept. It is redolent of the sort of reborn public-school values that have dominated British public life since Tony Blair became leader of the Labour Party 20 years ago.

I shall buy Race Plan - I may even read it - but I do not expect to be inspired by it. Still, I may have a pleasant surprise.

Heartbleed

Heartbleed is a catastrophic bug in OpenSSL:

"The Heartbleed bug allows anyone on the Internet to read the memory of the systems protected by the vulnerable versions of the OpenSSL software. This compromises the secret keys used to identify the service providers and to encrypt the traffic, the names and passwords of the users and the actual content. This allows attackers to eavesdrop communications, steal data directly from the services and users and to impersonate services and users.

Basically, an attacker can grab 64K of memory from a server. The attack leaves no trace, and can be done multiple times to grab a different random 64K of memory. This means that anything in memory -- SSL private keys, user keys, anything -- is vulnerable. And you have to assume that it is all compromised. All of it.

"Catastrophic" is the right word. On the scale of 1 to 10, this is an 11.

Half a million sites are vulnerable, including my own. Test your vulnerability here.

The bug has been patched. After you patch your systems, you have to get a new public/private key pair, update your SSL certificate, and then change every password that could potentially be affected.

At this point, the probability is close to one that every target has had its private keys extracted by multiple intelligence agencies. The real question is whether or not someone deliberately inserted this bug into OpenSSL, and has had two years of unfettered access to everything. My guess is accident, but I have no proof.

This article is worth reading. Hacker News thread is filled with commentary. XKCD cartoon.

EDITED TO ADD (4/9): Has anyone looked at all the low-margin non-upgradable embedded systems that use OpenSSL? An upgrade path that involves the trash, a visit to Best Buy, and a credit card isn't going to be fun for anyone.

EDITED TO ADD (4/10): I'm hearing that the CAs are completely clogged, trying to reissue so many new certificates. And I'm not sure we have anything close to the infrastructure necessary to revoke half a million certificates.

Possible evidence that Heartbleed was exploited last year.

EDITED TO ADD (4/10): I wonder if there is going to be some backlash from the mainstream press and the public. If nothing really bad happens -- if this turns out to be something like the Y2K bug -- then we are going to face criticisms of crying wolf.

EDITED TO ADD (4/11): Brian Krebs and Ed Felten on how to protect yourself from Heartbleed.

That Face!

Most folks who care about typefaces hate the font known as Comic Sans. Back in the early days of computers, that was someone's idea of what lettering in comic books looks like…but no professional comic book company would hire a letterer who lettered like that. Some of us cringe when we see it, especially in a context that's supposed to represent comics. Recently, a gent named Craig Rozynski designed a variant which he calls Comic Neue and which he has released into the public domain. You can download it here and install it on your computer. I wish I could say I like it more than I do.

It's especially lacking to me when it's used for ALL CAPS, which is how almost all comic book and strip lettering is done and it's the way Comic Sans has usually been used. The "C" and the "O" look rather anemic to me and, as with Comic Sans, we still have those ugly serifs on a capital "I." Professional comic book fonts always give you the option of a serifed "I" when you type the letter as a standalone and a non-serifed "I" when you're in the middle of a word. I also think the slanted crossbar on the "A" and "H" don't go with the non-slanted look of other letters.

I like it better for upper-and-lower case lettering because that eliminates much of the serif problem with the "I" but the interline spacing gets a bit dicey. I tried leaving more space between the lines but it seemed erratic. I appreciate Mr. Rozynski's generous efforts and he did improve on Comic Sans. But I think it still looks like lettering done by someone who isn't a professional cartoonist.

Could Clegg really be this Machiavellian?

The Lib Dems are in trouble. Real trouble.

If the proportion of people who vote for the party in next year's general election is in the low teens as is looking likely they could lose dozens of seats. They could even be back to the days of the parliamentary party "fitting in the back of a taxi".

But one thing that could ameliorate this is if in many of the seats that the yellows are defending where their challengers are the Tories, the blues do not do as well as the polls are predicting. And one way that this could happen is if there is a big UKIP surge around the time of the 2015 general election thus splitting the vote on the right and saving many Lib Dem seats in the process.

Of course most commentators think that the current UKIP polling numbers will fall back to more "normal" levels, say 5% or so and the dent to the Tories will be minimal.

But what if someone helped the UKIP leader Nigel Farage to raise his profile around a year before that general election? What if the profile raising was done in the forum of two debates between him and another politician, a member of the government which effectively elevated him to the status of a senior cabinet minister? What if Mr Farage was then widely seen to have won these debates, thus demonstrating that his views are very popular, far more so than the 10% - 15% that the polls would have us usually think?

In fact what if the fallout from such debates made it pretty much impossible for the UKIP leader to be excluded from the pre-election debates in 2015?

This could then of course lead to a big bounce for UKIP just around the time they need it to do maximum damage to the Tories and inadvertently help the Lib Dems.

Clegg couldn't possibly be so scheming. Could he?

I blame the voters

I suppose there are many policies that would fall into this category in some way or another. Examples would be the "bedroom tax" which although in principle in a perfect world might work, in a country where it has only been possible for 6% of those affected to actually move to a smaller house (due to lack of housing stock) it instead causes hardship and suffering for the remaining 94% for no good reason.

Another example from the other side would be the policy currently being floated by Labour of planning to reduce tuition fees from £9,000 per year to £6,000 per year. All this is going to do is reduce the amount of money that the wealthiest ultimately have to pay back as those who earn moderate or average salaries after graduation would never end up paying the full amount back before the 30 year limit anyway. So a party that professes to want to help the poorest in society are proposing a flagship policy that will actually help the richest.

And in fact calling this the politics of "not thinking things through" is probably too generous. I suspect in most cases these policies have indeed been thought through. It's just that the temptations to garner the headlines for "cracking down on benefits" or "reducing tuition fees for hardworking families" are too good to resist.

The politicians advocating and implementing these policies are really engaging in a form of willful blindness.

But there is an aspect of this that we should not ignore. Those politicians would not be able to get away with doing this if they were properly held to account. Yes, the media should do it but the responsibility equally falls on the shoulders of all of us.

So no longer being a member of a party I now have the freedom to do something that politicians never do.

I'm blaming the voters.

If we had an electorate that fully engaged with the issues then policies like the "bedroom tax" would never have been risked. Those planning to implement it would have realised there would have been a huge backlash from a well informed electorate that would have quickly worked out there is no way for it to work without punishing some of the poorest amongst us.

If we had a franchise that was fully numerate and understood how tuition fees currently work (and who ends up paying them back in full) then Labour would not chance their arm in pushing a policy that rewards future bankers and lawyers at the expense of everyone else.

If we all read up on the history of prohibition in the US in the 1920s and drew the parallels with the current "war on drugs" it is likely that our current damaging, ridiculous, incoherent and inconsistent drugs policies would have been reformed years ago.

But that does not happen. People are too busy and/or uninterested in matters of public policy to give the scrutiny it would require for them to take a collective and fully informed decision.

I get it. I get that for the vast majority politics is a vague background irritant that only impinges on their consciences very occasionally, e.g. at general election time.

What I am saying is that it is all very well to blame politicians for bad decisions (and I often do - they definitely should do better) but their primary goal is to get and retain power. If they think they can only do that by appealing to the lowest common denominator as they know it will be filtered through the tabloid press and by polemicists who often get the most media coverage then that is what they will do.

I'm not sure there is really an answer to this problem. If anything, political engagement has been on the slide in recent decades. I suppose it is possible that as the internet and social media become ever more pervasive the chance for people to fully engage with political issues and evidence increases. But the amount of times I have seen things that are blatantly false go viral online suggests that this is unlikely to be a good solution either.

One thing is for sure. If the electorate continues to be largely disengaged then we will continue to get these sort of policies.

And whilst I'm happy to apportion the fair share of blame to those vying for or in power I also think a substantial share should go where it is equally deserved.

You.

The Monster, Mashed

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not bitter.

A lot of people, they think I’m bitter, because of what happened. But I’m not. I’m not the kind of guy to be bitter. I had a good run. It’s not like I ain’t thankful for what I got. Believe me, I am. You know what life is like for most people like me? No matter what, at least I didn’t end up like my old man, face down in a swamp with a silver-tipped cane through his chest, and then thrown into Potters’ Field because he died without any clothes on. No wallet, no identification, so they chuck him into some hole in the ground on top of a hobo. It happens a lot more than you might think. At least that didn’t happen to me.

Some of the guys, they give me a hard time. It’s mostly young guys. They’re all about representing, having pride in your people, whatever that means. They say we shouldn’t ought to be second-class citizens. I say I agree with them: that’s how come I did it. I wanted a better life for my wife and my kids. But then they turn around and say I brought shame the race, or something like that. They call me an Uncle Tom, or there’s this one kid my son goes to college with calls me Howlin Fetchit. They say that I brought disgrace to our people, appearing on the front of them damn boxes with that goofy-ass grin on my face, slobberin’ all over a kiddie cereal like a clown. I try to tell them, look, my face on them damn boxes is what’s putting your best friend through college. He’s the first werewolf in the United States to do pre-med, and what do you think got him there? It was doing them damn cereal boxes what paid his tuition. But they don’t want to listen.

Well, the hell with them. They guys I’m really mad at…look, I don’t begrudge anyone their success. I wouldn’t want someone saying I didn’t deserve what I got, because I worked hard for that money. And it’s not like all the guys didn’t pull their own weight. Count Chocula? Christ, that guy was born to be a star. The way he filled out those brown tights — I mean, I’m no queer or nothin’, but you can see why the ladies were all over him. There weren’t no special effects with that guy. It was all real. He put it all out there when he did a commercial, never needed a second take. I always had to work real hard just to learn my lines, you know? I’m not one of them East Coast werewolves who went to prep school. I was born and raised right here in Youngstown, Ohio. It was all I could do to read the friggin’ cue cards when the whole while I wanted to tear the throat out of the guy holdin’ the boom mike. But Count Chocula, it all came natural to him. We’d be out at a bar after a long day doing promos, and some honey would walk in. She’d be all aloof, and he’d strut right up to her, in full cornball mode — holding his cape over his face, arching those pointy eyebrows, a bat flitting around his head. Super-cheesy, you know? We’d always think, no way is any girl gonna fall for his jive. But as soon as he’d open his mouth and say “Bleah!” she’d be handing him her hotel key. That guy, he was just…smooth, you know? A natural. I can’t say he didn’t deserve his success. Yummy Mummy — well, I’ll be honest with you: it was, like, nine different guys. They just wrapped up whatever stage hand wasn’t doin’ anything in the bandages and shoved him in front of the camera.

And Frank…well, I won’t lie to you. Me and Frank had our differences. I’m no Rhodes scholar, but honestly, that guy was dumb as a post. It might have taken me ten or twelve takes to learn my lines, but it took Frank six weeks just to learn his name. And, well, I don’t want to get into the personal stuff too much, but I’ll just say this: the pink outfit, that was Frank’s idea. But even with all that, I always liked the guy. I don’t judge nobody just because they’re different. What an undead monstrosity does in the privacy of his own bedroom, that’s his own business. Frank was a good guy, for the strawberry-flavored creation of an insane necromancer, and he always was friendly and did his job the best he could.

But Booberry. Jesus, that guy. It makes me mad just thinking about him. Always wising off to the director, thinking he was so smart because he went to friggin’ Julliard. Bragging about his acting lessons, even though he was down in the trenches doing commercials just like the rest of us. You couldn’t even take a picture of the guy that came out halfway decent because his eyes were all bloodshot and he had that stupid expression on his face — and why? Because he was fun-loving and easy-going? No, sir, buster. It was because he was high as a kite, all the time. That kid smoked more weed than all the damn Beatles put together. Even that stupid little hipster hat he wore drove me crazy.

So, naturally, when the company announced they couldn’t afford to keep all four of us on staff, I wasn’t too worried. Layoffs were a fact of life back in the ’70s. And I figured, hell, my job’s secure. Who are they gonna lay off — some snooty drugged-up ghost in a porkpie hat, or me, an honest-to-goodness werewolf? A werewolf is one of the Famous Monsters of Filmland; a ghost ain’t even really a proper monster! Besides, they already had one berry-flavored product; what did they need with two? I represented the entire spectrum of fruits; I wasn’t some one-trick specter.

I guess you can figure out what happened. Old General Mills came down to the set to tell me himself. Of course, he had his reasons. The fruit flavor wasn’t selling as well, he said. The whole “Brute” thing made moms nervous, like that was my fault instead of the marketing department’s. There was some kind of problem with the pink chemicals they used to die the pink marshmallow bits. What am I, a chemist now? I have to take the fall? It’s just business, says the General. It’s nothing personal. That’s what they said in The Godfather when they were about to whack a guy, that’s all I know.

Bitter? Hell, no. I ain’t bitter. I’m sweet.

Reply to all emails that somehow DO arrive with "haha what" regardless of sender or message content. I told you to do this already. So you should already be doing this.

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - cute - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | April 7th, 2014 | next | |

|

April 7th, 2014: So the last comic about how to tune TCP parameters gave what I thought was good advice, but another Ryan disagrees! And since I feel bad for people who are actually looking to tune their TCP parameters, and also since I respect all Ryans, here is what Ryan wrote. If you come to Dinosaur Comics for the comics but stay for the network infrastructure discussion, I have some good news: I'm going to have to disagree with T-Rex's advice about TCP buffers. Increasing the buffer sizes contributes to the problem of "Bufferbloat". Increasing the buffer size is generally only going to increase the latency. When you're sending traffic to a remote router, you want to match the rate you're sending the packets with the rate that they can be received. Going too fast will only clog things up. TCP has this algorithm to determine the right rate to send out packets: Increase the rate at which you send packets until some of the packets are dropped. Dropping packets is okay, because TCP has methods for retransmitting. This should let you find the optimum rate. However, what happens is that people put these huge buffers on their receiving routers. So even if you're sending out packets too quickly, you won't find out until that buffer is full, because only when the buffer is full will you start to get notifications that your packets are being dropped. So what'll end up happening is that you'll send packets more and more quickly, and then hit the limit, then all the sudden receive a crap-ton of drop notices, and then think that they can only receive packets very slowly, so you start sending at super-slow speed. You don't see any drops, so you start to dial the speed back up, and the cycle starts all over again. So you want the receiving router to send drops notices, to give the sender a good idea of how quickly to send. So, why even have a buffer at all? Well, you want it there so as to be able to absorb bursty traffic. But if the buffer is consistently full, all you're doing is adding latency. What should happen is that the receiving router actively manages its queue, and sometimes drops packets before it even has to, so as to give the people sending stuff to them a better idea of how quickly it is capable of receiving. The new CoDel ("controlled delay") module is the bufferbloat community's answer to this problem. It watches the queue and makes sure that stuff isn't staying in there for too long, and if it is, it starts dropping it. You can add it to an interface using the tc (traffic control) program. The qdisc is called "fq_codel", because it also performs "fair queueing" similar to what the "sfq (stochastic fair queueing)" qdisc does. So, if your goal was to troll buffer nerds into sending long-winded techno-ideological rants about active queue management, well played, sir. One year ago today: this summer... take it to the edge... ONE more time – Ryan

| |||

TELETUBBIES – “Teletubbies Say Eh-Oh!”

#778, 13th December 1997

My main point last entry was that “Perfect Day” saw the BBC applying its gift for pop spectacle to the demands of a more curatorial time. This would become – on broadcast TV particularly – an era of tighter demographics and multiplying niches, and the BBC would respond. BBC3, BBC4, 1Xtra, 6Music, CBBC, and in 2002 CBeebies, its channel for the under-6s, anchored for years by Teletubbies reruns.

My main point last entry was that “Perfect Day” saw the BBC applying its gift for pop spectacle to the demands of a more curatorial time. This would become – on broadcast TV particularly – an era of tighter demographics and multiplying niches, and the BBC would respond. BBC3, BBC4, 1Xtra, 6Music, CBBC, and in 2002 CBeebies, its channel for the under-6s, anchored for years by Teletubbies reruns.

In the old TV model, Top Of The Pops and the charts had enjoyed a happy symbiosis. With that show well along its slow decline, the charts were left without a centre. Instead they had new outlets – the supermarkets, and Woolworths, increasingly determined what reached No.1. As James Masterton pointed out in the comments for “Perfect Day”, this meant a dramatic broadening of the singles audience – the number of people visiting Tescos or Asda dwarfed the HMV or Our Price customer base, and included millions of musical impulse buyers. Put a tempting single in front of them and your sales could be colossal.

“Teletubbies Say Eh-Oh” is where these trends meet. It’s plainly a niche record with barely an eye or a furry antenna on wider accessibility. But there are enough people in that niche (parents of pre-school kids, basically) to give it seven figure sales. An awful lot of Number Ones are loved by children – the playground reception of a song has always been crucial – but this is the first number one designed for infants.

Which is entirely in keeping with its show’s aggressively radical spirit. Teletubbies was hugely successful and immediately controversial – a clean break from how pre-school TV had been done. It ditched the reassuring adult presenter in favour of a toddler’s perspective on pacing and action. In practise this meant very little explicit education or storytelling: replacing it was scripted babble-talk from the four tubbies, long sequences of dancing and messing about, cutaways to pieces of real-world play, and stories based on endless repetition of simple actions. The formula of younger kids’ TV, with its avuncular bumblers and well-scrubbed ladies telling stories and stacking up bricks, had been torn up. In its place was a show parents might find agonisingly boring but that one- and two-year olds quickly found magical.

The Teletubbies were at once the Beatles and the Pistols of pre-school TV – dramatic commercial success, remarkable innovation and a scorched earth attitude. It’s notable that none of their successors has been as extreme as they did – to take the inheritor shows on when I was the Dad of very young kids, In The Night Garden reintroduces the gentle adult narrator, and Baby Jake keeps the baby-first action but within a stronger story structure. The Teletubbies went further than anyone, first.

Squeezing that radicalism into a pop single was tricky. The writers’ solution is to structure “Teletubbies Say Eh-Oh” around a sped-up take on the theme tune, and break it up with incident – the gurgling and squelching of tubby custard, or a drop-in of “Baa Baa Black Sheep” with a baaing, mooing barnyard orchestra. The vibe is benign chaos.

But even within this single, their abandon is bounded. Teletubbyland is a carnival space, a world to play with but one policed by the movement of the sun (voiced by Toyah Wilcox!) and by abstract, unseen authorities. “Teletubbies Say Eh-Oh” ends as it begins, with peace, quiet and gentle chuckles. As a parent, I wouldn’t have it any other way, but as a piece of children’s culture muscling into the semi-adult world – the charts – it becomes vulnerable to other interpretations. Not just the “is Tinky Winky gay?” faux-controversy, or the show’s being dragged into the recurring debates around ‘dumbing down’, but more playful parallels. The screen-bellied tubbies drew comparisons to Cronenberg, and their life in a kind of kindergarten holiday camp (and their habit of playing with a giant beach ball) recalled The Prisoner. My own contribution to this disreputable canon is that the male voice (“Time for Teletubbies!”) massively reminds me of Tony Blair.

But you don’t need these extra readings to find subtext in this record. Towards the end, where a middle eight might go, some flowers give a very pert take on “Mary, Mary Quite Contrary”. This is where the song tips its hand, giving two pudgy plush fingers to the kids’ TV Teletubbies usurped. The flowers, in their Received Pronunciation mimsiness, very obviously represent that didactic tradition of rhymes and stories, and after singing they tut at the Tubbies and their “racket”.

Which – of course – starts right up again with the series’ catchprase (and parents’ bane) “Again, again!”. If “Teletubbies Say Eh-Oh” is annoying (and it is, a bit) it’s the deliberate, confrontational annoyance of “Mr Blobby” turned to a more specific end: to tell adults that this isn’t for you. And in doing that it drives home Ragdoll’s point in making the show in the first place: Teletubbies isn’t for you because toddlers aren’t like you. They are not best served by culture that treats them as latent schoolchildren or adults but by culture that takes their play and their desires seriously as they are. If this song’s presence at #1 is a sign of nicheification, its content and success is a good advert for it.

Sandy Denny and the Strawbs: Who Knows Where the Time Goes?

Yesterday morning I gently admonished Paul Walter for calling The Strawbs "one hit wonders".

It wasn't so much because they had a couple of other hits besides Part of the Union: it was because the band has a long and interesting history. At various times both Sandy Denny and Rick Wakeman have been members.

So here is an early Sandy Denny recording of her great song Who Knows Where the Time Goes? made in 1967 when she was briefly a member of The Strawbs. It was intended for an LP by the band, but this did not emerge until 1973, when it was titled All Our Own Work.

In 1969 Denny recorded the best known version of her song as part of Fairport Convention.

Anyway, thanks to Paul for helping me choose this week's music video.

The Heinlein Hormone

You all remember Starship Troopers, right?

That slim little YA contained a number of beer-worthy ideas, but the one that really stuck with me was the idea of earned citizenship— that the only people allowed to vote, or hold public office, were those who’d proven they could put society’s interests ahead of their own. Heinlein’s implementation was pretty contrived— while the requisite vote-worthy altruism was given the generic label of “Federal Service”, the only such service on display in the novel was the military sort. I’ll admit that thrusting yourself to the front lines of a war with genocidal alien bugs does show a certain willingness to back-burner your own interests— but what about firefighting, or disaster relief, or working to clean up nuclear accidents at the cost of your genetic integrity? Do these other risky, society-serving professions qualify? Or are they entirely automated now (and if that tech exists, why isn’t the Mobile Infantry automated as well)?

But I digress. While Heinlein’s implementation may have been simplistic and his interrogation wanting, the basic idea— that the only way to get a voice in the group is if you’re willing to sacrifice yourself for the group— is a fascinating and provocative idea. If every member of your group is a relative, you’d be talking inclusive fitness. Otherwise, you’re talking about institutionalized group selection.

Way back when I was in grad school, “group selection” wasn’t even real, not in the biological sense. It was worse than a dirty phrase; it was a naïve one. “The good of the species” was a fairy tale, we were told. Selection worked on individuals, not groups; if a duck could grab resources for herself at the expense of two or three conspecifics, she’d damn well do that even if fellow ducks paid the price. Human societies could certainly learn to honour the needs of the many over the needs of the few, but that was a learned response, not an evolved one. (And even when learned, it wasn’t internalized very well— just ask any die-hard capitalist why communism failed.)

I’ve lost count of the papers I read (and later, taught) which turned a skeptical eye to cases of so-called altruism in the wild— only to find that every time, those behaviors turned out to be selfish when you ran the numbers. They either benefited the “altruist”, or someone who shared enough of the “altruist’s” genes to fit under the rubric of inclusive fitness. Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene— which pushed the model incrementally further by pointing out that it was actually the genes running the show, even though they pulled phenotypic strings one-step-removed— got an especially warm reception in that environment.

But the field moved on after I left it; as it subsequently turned out, the models discrediting group selection hinged on some pretty iffy parameter values. I’m not familiar with the details— I haven’t kept up— but as I understand it the pendulum has swung a bit closer to the midpoint. Genes are still selfish, individuals still subject to selection— but so too are groups. (Not especially radical, in hindsight. It stands to reason that if something benefits the group, it benefits many of that group’s members as well. Even Darwin suggested as much way back in Origin. Call it trickle-down selection.)

So. If group selection is a thing in the biological sense, then we need not look to the Enlightened Society to explain the existence of the martyrs, the altruists, and the Johnny Ricos of the world. Maybe there’s a biological mechanism to explain them.

Enter oxytocin, back for a repeat performance.

You’re all familiar with oxytocin. The Cuddle Hormone, Fidelity in an Aerosol, the neuropeptide that keeps meadow voles monogamous in a sea of mammalian promiscuity. You may even know about its lesser-known dark side— the kill-the-outsider imperative that complements love the tribe.

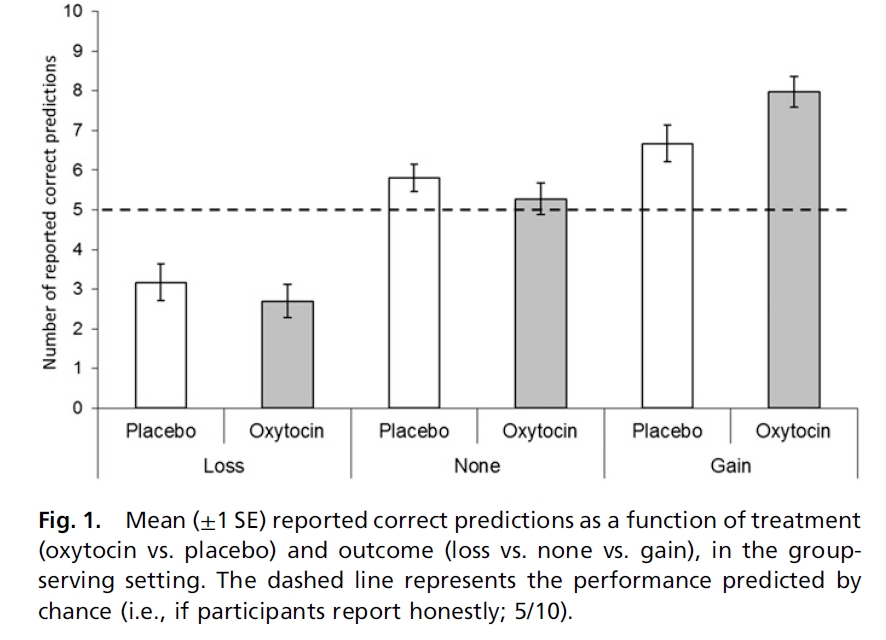

Now, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Shalvi and Dreu pry open another function of this biochemical Swiss Army Knife. Turns out oxytocin makes you lie— but only if the lie benefits others. Not if it only benefits you yourself.

The experiment was almost childishly simple: your treatment groups snort oxytocin, your controls snort a placebo. You tell each participant that they’ve been assigned to a group, that the money they get at the end of the day will be an even third of what the whole group makes. Their job is to predict whether the toss of a virtual coin (on a computer screen) will be heads or tails; they make their guess, but keep it to themselves; they press the button that flips the coin; then they report whether their guess was right or wrong. Of course, since they never recorded that guess prior to the toss, they’re free to lie if they want to.

Call those guys the groupers.

Now repeat the whole thing with a different group of participants— but this time, although their own personal payoffs are the same as before, they’re working solely for themselves. No groups are involved. Let’s call these guys soloists.

I’m leaving out some of the methodological details because they’re not all that interesting: read the paper if you don’t believe me (warning; it is not especially well-written). The baseline results are pretty much what you’d expect: people lie to boost their own interests. If high predictive accuracy gets you money, bingo: you’ll report a hit rate well above the 50:50 ratio that random chance would lead one to expect. If a high prediction rate costs you money, lo and behold: self-reported accuracy drops well below 50%. If there’s no incentive to lie, you’ll pretty much tell the truth. This happens right across the board, groupers and soloists, controls and treatments. Yawn.

But here’s an interesting finding: although both controls and groupers high-ball their hit rates when they stand to gain by doing that, the groupers lie significantly more than their controls. Their overestimates are more extreme, and their response times are lower. If you’re a grouper, oxytocin makes you lie more, and lie faster.

If you’re a soloist, though, oxytocin has no effect. You lie in the name of self-interest, but no more than the controls do. The only difference is, this time you’re working for yourself; the groupers were working on behalf of themselves and other people.

So under the influence of oxytocin, you’ll only lie a little to benefit yourself. You’ll lie a lot to benefit a member of “your group”— even if you’ve never met any of “your group”, even if you have to take on faith that “your group” even exists. You’ll commit a greater sin for the benefit of a social abstraction.

I find that interesting.

There are caveats, of course. The study only looked at whether we’d lie to help others at no benefit to ourselves; I’d like to see them take the next step, test whether the same effect manifests when helping the other guy actually costs you. And of course, when I say “You” I mean “adult Dutch males”. This study draws its sample, even more than most, from the WEIRD demographic— not just Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, but exclusively male to boot. I don’t have a problem with this in a pilot study; you take what you can get, and when you’re looking for subtle effects it only makes sense to minimize extraneous variability. But it’s not implausible that cultural factors might leave an imprint even on these ancient pathways. The effect is statistically real, but the results will have to replicate across a far more diverse sample of humanity before scientists can make any claims about its universality.

Fortunately, I’m not a scientist any more. I can take this speculative ball and run with it, anywhere I want.

As a general rule, lying is frowned upon across pretty much any range of societies you’d care to name. Most people who lie do so in violation of their own moral codes— and those codes cover a whole range of behaviors. Most would agree that theft is wrong, for example. Most of us get squicky at the thought of assault, or murder. So assuming that Shalvi and Drue’s findings generalize to anything that might induce feelings of guilt— which, I’d argue, is more parsimonious than a trigger so specific that it trips only in the presence of language-based deceit— what we have here is a biochemical means of convincing people to sacrifice their own morals for the good of the group.

Why, a conscientious objector might even sign up to fight the Bugs.

Once again, the sheer abstractness of this study is what makes it fascinating; the fact that the effect manifests in a little white room facing a computer screen, on behalf of a hypothetical tribe never even encountered in real life. When you get down to the molecules, who needs social bonding? Who needs familiarity, and friendship, and shared experience? When you get right down to it, all that stuff just sets up the conditions necessary to produce the chemical; what need of it, when you can just shoot the pure neuropeptide up your nose?

It’s only the first step, of course. I’m sure we can improve it if we set our minds to the task. An extra amine group here, an excised hydroxyl there, and we could engineer a group-selection molecule that makes plain old oxytocin look like distilled water.

A snort of that stuff and everyone in the Terran Federation gets to vote.

Geekological Determinism

Wil Wheaton’s career has described a curious arc around the atmosphere of pop culture. He came to fame starring as Wesley Crusher in Star Trek: The Next Generation, a teenage prodigy and transparent Mary Sue figure; though nerd culture was still a fringe activity and not the dominant force that it is today, Trek fans, then as now, were an unforgiving lot, and Wesley became one of the most despised fictional characters since Scrappy Doo. What this must have done to the psyche of young Mr. Wheaton, who was then only 15 years old, is hard to imagine, but to his credit, he seemed to emerge from the hailstorm of hatred relatively unscathed. Even more to his credit, he did not let the experience sour him on his passions; indeed, he grew into what he is today: one of the most outspoken and enthusiastic advocates of nerd culture. He is a ceaseless defender of the once-obscure habits and hobbies of his youth, and it is his curious good fortune that he has become widely beloved by the same sort of people who once so reviled the character that made him famous.

Recently, a video has achieved virality that features Mr. Wheaton answering a question from a young girl about whether he was called a nerd as a young boy. His response has become widely circulated because Wheaton turned it into a commentary about something called ‘anti-nerd bullying’; that alone is a subject worth exploring, but it is not what I want to explore now. Before I begin, because I am going to settle into what is clearly a comfortable seat for me, attacking the highly praised but slackly investigated utterances of the well-meaning, I should make the following qualifications: I have no problem with Wil Wheaton. I find his public persona as an advocate of the joys of nerdery inoffensive and charming, if not particularly to my taste. It certainly does hurt to be called names when you are a child, and there is nothing wrong with seeking to put an end to bullying and cruelty of any sort. When Mr. Wheaton says that you should never let someone “make you feel bad because you love something”, he is not only right, but he is right in a very straightforward and admirable way. He is generally correct in identifying self-loathing as the proximate cause of much bad behavior, and even if the whole encounter was contrived — and I have no reason to believe that it was — if all he did was encourage a little girl to not let the careless words of a bully destroy her self-esteem, then he has unquestionably done a fine thing.

What troubles me is this curious statement, which appeared in the middle of Wheaton’s speech, and which cast a cloud over it to my hearing: “It’s never okay when a person makes fun of you for something you didn’t choose,” he said, apparently referring not to blindness or cerebral palsy but to enjoying science fiction. “We don’t choose to be nerds. We can’t help it that we like these things.”

Surely not.

Nature and nurture once had a “vs.” between them, I know, and if we have wisely decided to place them on a continuum rather than as binaries in opposition, it is still true that many things about that most vital of issues, human behavior, are difficult to definitively attribute to either genetics or environment. I will not argue that it is still little-understood why we turn out one way and not another. But surely we are not arguing that, like albinism or the length of one’s fingers, an affinity for comic books is bred in the bone. Are we really to believe that we are born with an inherent proclivity to dress up in a Darth Vader costume? What possible use is it to teach a child that she “can’t help it” if she spends all her money on Magic cards?

The language is easy enough to recognize. Its familiarity comes from the fact that it is the exact same language of those who use the ‘biological determinism’ argument to defend the rights of homosexuals. Gay people “didn’t choose” to be gay, this argument goes; given the torment attached to such behavior, who would? Instead, they are “born that way”, as if made so by a capricious god, and it would be wrong to punish someone for something that they “can’t help”, just as it would be wrong to push a cripple down the stairs. It’s a compelling argument, and one can certainly see the rationale behind it, especially as its formal qualities appeal to those who think of human behavior exclusively in moral and spiritual terms — the very people most likely to condemn homosexuality and other perceived forms of social deviance. There’s just one problem with it: it’s wrong, it’s false, and it’s harmful on almost every conceivable level.

For one thing, science — you know, that thing so beloved of self-identified nerds — is hardly conclusive on the question of whether or not homosexuality is an inborn quality. The study of genetics, as deep as it has become, is still in its infancy, and the question of what “causes” homosexualty is fraught with difficulty — not least because the most informed consensus is that “homosexuality” is not a trait, but a behavior. This is a subtle but crucial difference. Certainly there is some evidence that genetics play some part in homosexual behavior, but what that part is has not been answered in anything like a definitive way. And it is also true that one does not “choose” homosexuality, as such; but the very formation of the concept of sexuality as a “choice” is deeply flawed, as is the notion that it is absolute and diametric. It seems much more likely, the more one studies not only genetics but history, sociology, psychology, zoology, and anthropology, is that sexual behavior is not always located at an absolute of same-sex or opposite-sex affinity; rather, it is located on a spectrum, and can move towards one end of that spectrum or away from it over time and in different situations and environments. It is certainly indisputable that in the animal kingdom, homosexual behavior is found all over the place, and becomes more common the more the object of study resembles humans; it is also true that human beings are perfectly capable of evincing straight, gay, or bisexual behavior at different times in their lives. What this means is still very much in dispute, but what is clear is that the idea of homosexuality as a strictly deterministic dichotomy is rather unlikely.

It is in this way — by using an argument that plays into a moralistic model constructed by its enemies — that the gay community does itself a disservice. For the very arguments they use to defend themselves against oppression are the most likely to be turned against them. If homosexuals are born that way, after all, might not homosexuality itself be viewed as a flaw, a genetic mistake, a birth defect to be isolated and eliminated like harelips or spina bifida? If homosexuality is a condition and not a behavior, then it is subject to a cure. Claiming that same-sex relationships are something its participants cannot help and did not choose frames them as a moral failing, a biological horror, something shameful that its participants would just as soon be rid of if they had any say in the matter. It is not just a failed defense, it is a dangerous one; for not only does it play into the moralistic worldview of its opponents, but the more sophisticated among them will seize on its error, leading to an intolerable situation where we’re hearing the truth about something from the last people you want in possession of that truth.

All these things apply just as much, if not more so, to Mr. Wheaton’s strange claim that nerd-culture affinity is unchosen, inherent, unbidden. While it is not a scientific impossibility, the idea that one’s personal tastes in art is simply the manifestation of a genetic code is even less supportable than the idea the vast spectrum of human sexual behavior is attributable to fate in the form of a stray gene. Even if it were true, which it isn’t, it would paint a pretty dismal picture, even from — perhaps especially from — the viewpoint of people like Wheaton. If one does not choose one’s tastes in art, what does one choose? If aesthetic tendencies are genetic, they are also, therefore, objective, and it’s just a short step to Zhdanovite thinking or Ayn Rand’s preaching that some composers are just definitively superior to others. Believing that you can’t help your preferences for art, music, film, and other manifestations of culture robs you of your specialness; who wants to be a nerd if being a nerd is just some biological manifestation you had no more say in than you did your height or your hair color? Why be enthusiastic about the books you love if your love of them is just a genetic proclivity? Why be proud of the hard work you did learning science and math while the other kids were playing softball, if your aptitude in science and math was going to express itself anyway with the relentless inevitability of a receding hairline? Better, surely, whether the subject is same-sex marriage or a love of Star Wars, not to say “I cannot help this; I was born this way”, but rather “Whether I chose this or not, this is who I am and what I want to do, and you have no right to judge me, because what I am doing is not wrong.”

Worse still, the idea that our cultural beliefs are nothing more than the emergence of a pattern laced into our brains at birth enforces one of the most noxious aspects of nerd culture: it destroys the possibility of the fan as creator, the reader as writer, the audience as actor, and relegates the entire relationship between artist and art to that of consumer and consumed. What hope have we to take an owner’s view of culture when we are merely eating things that we were born to have a taste for? If you didn’t choose to participate in the culture you are drawn to, how could you possibly choose to take it any further, to turn it into something more than what it already is? When you cannot help the culture you belong to, you cannot change it, and you certainly cannot turn it into something different. You are not a participant in your art (or your sexuality, or your society, or your gender, or your race, or any of the other arbitrary constructs so eagerly forced on you by people who want to stop you from questioning them; you are merely a part of it, and bound to conform to the contours of what other people say it is.

I honestly believe Mr. Wheaton is sincere in what he says, and that he was doing his genuine best to help that girl, and to help other people who were like the child he once was. But he can help even more by shedding this notion of culture as a deterministic straitjacket, and by telling the next girl he talks to that she is not a born expression of factors she cannot change, but a free mind who can make of her culture and anyone else’s whatever she likes, and that she need not apologize for the choices she makes.

Jesus On The Main Line

“Well, how’d you know it was Him, Jimmy, is my question.”

“I just knowed it.”

“Now, how’d you ‘just knowed’ somethin’ like that? You don’t ‘just know’ that somebody’s the Lord Jesus Christ returned to Earth.”

“Some things you just know, Clint. Like, instinctually.”

“What’d He look like?”

“About what you’d expect, really. Beard, white robe. Belt made out of a piece of rope. Sandals. Kind of a short fella. He didn’t look too good, to tell you the truth.”

“So where’d you run into Him again?”

“Out on the side of the road, by US 385.”

“Over acrost from the Peach Tree?”

“That’s the one.”

“What was He doin’, headin’ over there for a cup of coffee or somethin’?”

“Now, see, that’s what I figured. I reckoned He was a hitchhiker or similar, and I was God’s honest truth gonna tell Him to move right along because we didn’t want nobody in the Peach Tree puttin’ the touch on us. But as soon as He opened his mouth, I knowed he was the Savior.”

“And how’d you know that? On account of He told you so?”

“Well, on account of He spoke Aramaic, for one thing.”

“Arawhovic? You mean like an A-Rab? I thought you said it was Jesus, not Moo-hammed.”

“No, that’s Arabic, you numbnuts. This was Aramaic He was speakin’.”

“And how in the hell do you come to speak Aramaic, Jimmy? You don’t even talk English good.”

“You know how I got that little teevee out in the barn, and I watch it when I’m milkin’?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, all that’s on in the early morning save for them damn woman shows is Home Extension University on the public television channel. So I just picked it up.”

“All right, all right. What’d He say?”

“As you might ‘spect, it was His second coming. Only He was havin’ all kinds of problems.”

“Problems? What you mean, problems? He’s the son of God, for corn sake, Jimmy.”

“Now as it happens, Clint, that’s one of the problems. The way He tells it, the Old Man don’t keep too much up on current affairs. He’s too busy watchin’ every sparrow fall and what have you. Don’t even own a dish or nothin’. So has far as the Old Man’s concerned, ain’t nothin’ changed for two thousand years.”

“You’re shittin’ me.”

“Don’t kid a kidder, Clint, is what I always say. So God sends Jesus down here, don’t give Him no cell phone, don’t give Him no blue jeans or walkin’ shoes, don’t give Him no car, don’t even teach Him to speak English. Kid looks like a rat’s nest and don’t smell so good neither. And he’s out here, in Dalhart. God just plunks Him down any ol’ where, figures He’ll get to where He needs to be. Poor kid ain’t got no road atlas or GPS or nothin’. Hell, if I hadn’t come along, He mighta run into Bert Klum down at the Lions Hall, and then He’d be in a right mess. Bert probably shove a pool cue up His ass thinkin’ he’s a crankhead.”

“So…so what happened?”

“Well, it turns out He gots all these speeches He needs to deliver, right? Sermons and whatnot. So as to save the world, I guess. And He tells me He needs to get to where all the action is, so He can get peoples’ ears. So He asks me if I know how to get to Jerusalem.”

“Oh, Lord.”

“You said it. I told him I don’t think that’s really the right place for Him right now. I didn’t go into much detail, understand me. I just suggested He oughtta think about maybe Hollywood, or at least Nashville.”

“Good thinkin’.”

“Well, He wasn’t havin’ none of it. He said it had to be the Holy Land or at least the greatest city in all the world, which He didn’t know what was what. He kept talkin’ about places like Antioch and Thessalonika.”

“So what’d you do?”

“Well, what could I do, Clint? He’s Jesus. I can’t just disobey Him, now, can I?”

“Oh, Jimmy, you didn’t.“

“I drove Him down to Dallas and took Him to Love Field, and got Him a ticket for…”

“No.”

“…New York City.”

“Jimmy…”

“What other choice was there, Clint?”

“Jimmy, do you know what deicide is?”

“A little bit.”

“Do you know what punishment that feller Danty prescribes for deicide?”

“I can’t rightly remember, Clint, now you come to mention it.”

“You better hope Satan brushes his teeth regularly, Jimmy, is all I can say.”

“Yep.”

“Yep.”

“I reckon.”

How to Understand Things for What They Really Are

I don’t know if there is a “Which Character from House of Cards Are You?” quiz, and I don’t know what character from that show you’d actually want to be. I do know that there is a “Which Character from Basic Instructions Are You?” Quiz. I also don’t know which character from my comic you’d actually want to be.

And now it’s time for your third chance to win a signed copy of the new edition of Off to Be the Wizard (Magic 2.0). In addition to that book, the prize package will also include the Basic Instructions 2014 Box Calendar

, and a signed copy of a book by a different author. This week, the bonus book is You, by Charles Benoit.

You can enter below by friending Off to Be the Wizard on Facebook, following me on Twitter, or by leaving a comment on this post answering a simple question. (FYI, last week there was some confusion because only those who entered could see the question. For the record, the question is "Do you prefer paper or e-books, and if if it e-books, what format?")

Sadly, the offer is only open to people in the United States. Shipping costs, what can I say? The contest closes on, April 13th at 12am, then a new give away with a different bonus book will begin. Thanks, and good luck!

As always, thanks for using my Amazon Affiliate links (US, UK, Canada).

Mea Culpa: I Was Wrong On #EqualMarriage

Andrew HickeyShared because it's something we must keep in mind -- even though same-sex marriage has been won, the fight goes on.

I didn't choose to make marriage equality "my thing". I didn't go looking for an issue to get a bee in my bonnet over. Marriage equality sort of just fell into my lap. Unwanted but insistent. There I was, a happy 21 year old working weekdays and trolling down Old Compton Street on the weekends, and suddenly people started getting all excited about civil partnerships. I couldn't understand it. That's not equality you dimwits, my less than tactful inner monologue said, that's just crumbs to keep you quiet. I couldn't comprehend the fact no one else, other than folks like Peter Tatchell, could see what was happening. All my gay mates were beside themselves with glee and the media was lapping it all up, and I was sitting grumpily in a corner wondering if everyone had lost their mind. I was naive.

I was naive to one think that LGBT politicians would stand up for what was right rather than do deals behind the scenes. I was also naive to believe that most LGBT people had the ability to see things more clearly than most other people. I stupidly had this odd notion LGBT had more common sense than Joe Public. Which probably in itself proves we don't.

At the same time I fell deeply in love. My connections with the gay scene dwindled as my other half and I disappeared into our own little romance. Safely out of touch with the general lack of excitement of LGBT people for it, I started to argue for marriage equality.

There was a genuine injustice to be corrected. Civil partnerships were not equality, though they served a purpose, and I was not going to just allow that to be forgotten. I came up against a brick wall when it came to LGBT politicians and organisations who seemed to think I was completely mad. Marriage? Why ever would we need that? Labour, in particular, seemed unable to grasp the concept that their beloved civil partnerships may not have been perfect. And that just spurred me on. I'd always, in my younger days, been open to radical queer theory, but when I encountered arguments from that perspective against marriage equality (that it would serve to neuter our sexual expression, for conformity on to us etc.) I dismissed them as just more lefty incomprehension of the injustice I saw.

I admit I never really wanted marriage equality. I had bigger dreams. But the rejection I got from all I brought up the subject with (a lot of people!) turned my belief in equal marriage from a principle into an obsession. And soon I found others who actually did share my views and eventually they reached the right people and here we are 9 years later with same-sex marriage.

And now the chance to rest and see if what we have created is good. And I do not think it is. Partly that is because it isn't equal marriage. Same-sex marriage is yet another messy compromise and, in the same way as happened with civil partnerships, most people refuse to acknowledge that fact. We failed here in England and Wales to get marriage equality.

Mostly though, now I feel the fight has reached a stalemate (I doubt the changes we need to fix same-sex marriage will come about any time soon), I look upon what has been created and shake my head with shame.

This was meant to be a liberation. Same-sex couples could marry and enjoy the same benefits as opposite-sex ones. We could choose our futures and live our lives as we wished, whether that was through a marriage or by fucking our brains out with a different guy every night. Suddenly we'd have the right not to have to conform to any one culture. Conservative gays and radical gays and all those in between finally had the right to be themselves. How stupid was I hey?

Instead a new conformity seems to be forming around a conservative homosexuality (trans folks need not apply), I realise this was happening before 2014 but I was too single-mindedly obsessing over equal marriage to notice. Through chats with others about my opposition to many of Stonewall's latest prudish initiatives and my issues with how gay couples have gone from pariahs to Disney-fied paragons of virtue on TV I realise same-sex marriage has helped shore up the more conservative outlook of some LGBT people. It plays into the hands of those who wish to demean sexually active teenagers, who wish to prudishly oppose even partial nudity and who wish to close bathhouses and "clean up" the gay scene. Now I know those people weren't in this fight from the beginning. I know many of these folks didn't even think about marriage equality until the bandwagon was practically over the finish line. They were the very people, in some cases literally, who dismissed my questions and arguments about marriage equality pre-2010. But... now I've supported giving them a weapon with which to craft a new narrative of clean-cut, prudish homosexuality. I've supported giving them a new rod with which they can beat those who don't conform. I should have seen what they'd do with even this slight amount of freedom. And I didn't.

And I was wrong not to see this. Foolish. Naive. I'm angry now to know that, in years to come, pain will be caused to those who don't conform because of something I supported. Angry that now emboldened elements will up their fight to desexualise, normalise and "sanitise" others.

This isn't what I hoped for. This isn't the freedom I signed up to. And I just don't know how it can be made right.

I still think fighting for equal marriage was right in principle. But the consequences... I should've seen them coming.

The Other Spousal Veto

The other Sarah has dug out some revealing statistics from the Ministry of Justice.

The first statistic is interesting, but probably not that surprising for anyone involved in trans activism. There is a clause in the Gender Recognition Act 2004 that allows the Secretary of State to refer to the courts any case where they believe gender recognition might have been obtained fraudulently. Despite the fact that the Gender Recognition Panel (GRP) insist on documentary evidence that someone transitioned at least two years ago, that they provide letters from two doctors on the GRP’s list of approved doctors and up until now, that they divorce, there was still a fraud clause included in the act just in case.

No case has even made it as far as a referral to the courts due to fraud, which rather takes the wind out of the sails of anyone suggesting gender recognition is too easy to obtain, or that people do it because they want to commit fraud. (You can change your name without also changing your gender, anyway)

The second statistic is rather more worrying, however. Many people will know about the spousal veto included in the Same-Sex Marriage Act that allows spouses to de facto veto gender recognition of even an estranged partner. But there is an older spousal veto: Section 12(h) of the Matrimonial Causes Act, which was inserted by the Gender Recognition Act way back in 2004.

It was always thought that this clause, which allows someone to void their marriage if they find out their partner had obtained legal gender recognition prior to the marriage, was largely theoretical. There are some safeguards – there’s a time limit of three years after marriage to annul unless you get special permission from a judge, and it only applies if you didn’t know your spouse had a Gender Recognition Certificate. (This last point is a little tricky, because it’s hard for someone who is not out to prove they told their spouse something so it’s likely to descend into a case of he-said-she-said in court)

As with the spousal veto, this is just another case of the law feeling it needs to create special cases surrounding trans folk. But this is unnecessary – if trust in the marriage has broken down to that extent, why not resort to the usual divorce process – just as you would have to if your new husband or wife turned out to be a convicted criminal.

Unfortunately, it turns out not to be so theoretical after all. As a result of the Freedom of Information request, we now know that at least 13 marriages have been annulled because the spouse claimed not to have known their partner had a GRC. The reason is only recorded in 60% of cases, so the actual figure is higher – 21 or 22 cases in total, which is two or three cases a year.

So that’s yet another way in which trans folk have less rights in marriage than everyone else.

Equal marriage? I wish.

A nation of slaves

Firstly, this is impossible. Secondly, explaining why is ... well, George Orwell coined a word to describe this sort of thing, in 1984: Crimestop—

The faculty of stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought. It includes the power of not grasping analogies, of failing to perceive logical errors, of misunderstanding the simplest arguments if they are inimical to Ingsoc, and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction.Today, in the political discourse of the west, it is almost unthinkably hard to ask a very simple question: why should we work?

There are two tests I'd apply to any job when deciding whether it's what anthropologist David Graeber terms a Bullshit Job.

Test (a): Is it good for you (the worker)?

Test (b): Is it good for other people?

A job can pass (a) but not (b) — for example a con man may enjoy milking the wallets of his victims, but their opinion of his work is going to be much less charitable. And a job can pass (b) but not (a) if it's extremely stressful to the worker, but helps others—a medic in a busy emergency room, for example.

The best jobs pass both (a) and (b). I'm privileged. I have a "job" that used to be my hobby, many years ago, and if Scrooge McDuck left me £100M in his legacy (thereby taking care of my physical needs for the foreseeable future) I would simply re-arrange my life to allow me to carry on writing fiction. (I might change the rate of my output, or the content, due to no longer being under pressure to be commercially popular in order to earn a living—I could afford to take greater risks—but the core activity would continue.)

On the other hand, many of us are trapped in jobs that pass neither test (a) nor test (b). If Scrooge McDuck left you £100M, would you stay in your job? If the answer is "yes", you're one of the few, the privileged: most people would run a mile. I've had jobs like that in the past. We let ourselves get trapped in these jobs because our society is organized around the principle that we are required to work in order to receive the money we require in order to eat. On a higher level (among the monied classes) the principle is different: work is performed for social status, financial income may be a side-effect of receiving rent. But people are still supposed to do something. People are, in fact, defined by what they do, not by who they are.

Now for a diversion.

As John Maynard Keynes observed in the 1930s, we produce material goods more efficiently today than during previous eras of history: our economic growth is predicated on this. Why should we not divert some of our growth into growing our leisure time, rather than growing our physical wealth? We ought to be able to make ends meet perfectly well with an average 15 hour working week—or, alternatively, a 40 hour week for 20 weeks a year, or a 40 hour week for 48 weeks a year for a ten year working lifetime.

And indeed in some cultures and countries this happens, to some extent. Here are some handy graphs of European working hours and productivity per week. Workers in Germany average a little over 35 hours a week, compared to the 42 hours worked in the UK. Want vacation days? German law guarantees 30 working days of vacation per year (and I am told medical leave for attending a spa resort on top of that). But it's all pretty paltry compared to the 15 hour target.

It's also quite scary when you consider that we're entering an era of technological unemployment. More and more jobs are being automated: they aren't going to provide money, social validation, or occupation for anyone any longer. We saw this first with agriculture and the internal combustion engine and artificial fertilizers, which reduced the rural workforce from around 90% of the population in the 17th-18th century to around 1% today in the developed world. We've seen it in steel, coal, and the other 19th century smokestack industries, which at their peak employed 30-50% of the population in factories—an inconceivable statistic today, even though our net output in these areas has increased. We're now seeing it in mind-worker fields from law (less bodies needed to search law libraries) through architecture (3D printers and CAD software mean less time spent fiddling with cardboard models or poring over drafting tables). Service jobs are also being automated: from lights-out warehousing to self-service checkouts, the number of bodies needed is diminishing.

We can still produce enough food and stuff to feed and house and clothe everybody. We can still run a growth economy. But we don't seem to know how to allocate resources to people for whom there are no jobs. There's a pervasive cultural assumption that people who don't work are shirkers or failures, rather than victims of technological change, and this is an enabler for populist politicians who campaign for support from the frightened (because embattled) working majority by punishing the unlucky, rather than admitting that the core assumption—that we must starve if we can't find work—is simply invalid.

I tend to evaluate the things around me using a number of rules of thumb, one of which is that the success of a social system can be measured by how well it supports those at the bottom of the pile—the poor, the unlucky, the non-neurotypical—rather than by how it pampers its billionaires and aristocrats. By that rule of thumb, western capitalism did really well throughout the middle of the 20th century, especially in the hybrid social democratic form: but it's now failing, increasingly clearly, as the focus of the large capital aggregates at the top (mostly corporate hive entities rather than individuals) becomes wealth concentration rather than wealth production. And a huge part of the reason it's failing is because our social system is set up to provide validation and rewards on the basis of an extrinsic attribute (what people do) which is subject to external pressures and manipulation: and for the winners it creates incentives to perpetuate and extend this system rather than to dismantle it and replace it with something more humane.

Meanwhile, jobs: the likes of George Osborne (mentioned above), the UK's Chancellor of the Exchequer, don't have "jobs". Osborne is a multi-millionaire trust-fund kid, a graduate of Eton College and Oxford, heir to a Baronetcy, and in his entire career spent a few working weeks in McJobs between university and full-time employment in politics. I'm fairly sure that George Osborne has no fucking idea what "work" means to most people, because it's glaringly obvious that he's got exactly where he wanted to be: right to the top of his nation's political culture, at an early enough age to make the most of it. Like me, he has the privilege of a job that passes test (a): it's good for him. Unlike me ... well, when SF writers get it wrong, they don't cause human misery and suffering on an epic scale; people don't starve to death or kill themselves if I emit a novel that isn't very good.

When he prescribes full employment for the population, what he's actually asking for is that the proles get out of his hair; that one of his peers' corporations finds a use for idle hands that would otherwise be subsisting on Jobseekers Allowance but which can now be coopted, via the miracle of workfare, into producing something for very little at all. And by using the threat of workfare, real world wages can be negotiated down and down and down, until labour is cheap enough that any taskmaster who cares to crack the whip can afford as much as they need. These aren't jobs that past test (a); for the most part they don't pass test (b) either. But until we come up with a better way of allocating resources so that all may eat, or until we throw off the shackles of Orwellian Crimestop and teach ourselves to think directly about the implications of wasting a third of our waking lives on occupations that harm ourselves and others, this is what we're stuck with ...

Counting to Nothing

The exact definition of atheism is one that’s hotly-debated in philosophical circles. The everyday meaning, roughly: ‘an atheist is someone who doesn’t believe in God’ is simple enough, as is the slight clarification ‘or any of the gods’, and its corollary, ‘y’know or all of that stuff, like devils, angels, prayers, the afterlife, miracles and so on’.

But traditionally there’s been a problem which boils down to whether atheism is holding the belief ‘there is no God’ or not holding the belief ‘there is a God’. I think it’s easy to see there’s (a) little practical difference, and (b) quite an important one philosophically. It essentially comes down to who has the onus to justify their position, and the upshot is an endless cycle of ‘you need to prove God exists / no you need to prove God doesn’t exist’.

Part of the point of being an atheist is that you really don’t think this sort of thing is worth bothering with. But, if pressed, most atheists would say they hold the belief ‘there is no God’, rather than not holding the position there is one. Atheists who do talk about their atheism are fond of saying things like ‘Off is not a TV channel’ or ‘abstinence is not a sex position’, ‘people who don’t live in Manchester aren’t Amancunian’. It seems faintly ridiculous to suggest that someone who is not interested in Cricket ‘has not-interest’ in things like spin bowling, the West Indies, Wisden or the state of the pitch at Lords.

If atheism is framed as ‘not holding the belief “there is a God”’, that assumes the default state of the human race to be ‘religious’. It’s no coincidence that theists often accuse atheism of being a ‘religious belief’, or that ‘it takes more faith to be an atheist’, or say things like ‘the vast majority of the human race is religious’. If someone told a vegetarian that they were carnivorous, because No Meat is a type of animal, you would probably think that someone should be sectioned, but ‘atheism is a religious belief’ is a respectable argument in theistic circles.

It would be handy strategically for theist philosophers if atheism was ‘holding the position there is no God’, as it essentially makes the argument a Home game for them, not an Away one. Atheists, by that definition, have opted out of theism and they’re the ones who have to justify their position, and they’d have to do it starting out by explaining their notions of God and why they’re rejecting them.

The dark secret of theology is that it can’t do the job most people think it’s there for.

I’d always assumed a lot of theology was about looking for signs of God, like God was a Higgs-Boson or something like that. Modern theology actually has very little new to say or do concerning ‘proof God exists’ (or disproving it). And the reason is simple: within moments of starting a study of theology, it’s made clear it’s impossible to use logic to prove God exists.

We can demonstrate this in one sentence. Ahem. ‘There is, by definition, no way for us to distinguish God from a being capable of deceiving all other beings into believing it is God’. Whatever the miracle, demonstration of power, revelation, artefact or argument presented, however kind or wise ‘He’ was, we could never be sure that ‘God’ was the real deal. He wouldn’t need to be God, he would just need to be able to make us think he’s God. Even if ‘real God’ showed up with a host of angels, bellowed ‘IMPOSTER!’ and sent Jesus in to kick the false God in His nuts, then … well, what’s to say this new arrival isn’t just another imposter?

‘Fooling every human being’, presumably, would require a lot less power than ‘being God’. We’re easily fooled, after all. The overwhelming probability is that any given ‘God’ is not God. And, happily, that’s exactly what religions teach – the central proposition of most religions is that while every other one is the work of smooth conmen in it for the bling and pussy, this religion is the one, real deal. Not every human being holds the idea ‘gods exist’, but every single person holds the position ‘not all claims made about gods are true’. Indeed, if you’re looking for a ‘universal human religious belief’, then the only ones we know for certain have existed in every society are ‘sorry, not buying it’ and ‘I’m being dragged along under protest’. As the motto goes, every Christian’s an atheist when it comes to all the other gods. The early Christians in Rome were prosecuted for atheism, as they did not honour the city gods.

There have been lots of attempts at proofs, some better than others, but even the scholar responsible for the most extensive and influential attempts to come up with something compelling, Thomas Aquinas, concedes ‘to one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible’. It’s not that we haven’t found compelling logical proof God exists, Aquinas says, there simply can’t be a compelling logical proof independent of faith. And, of course, if you have faith, you’ve already answered the question you’re meant to be exploring. It explains why Aquinas’ proofs are seen as eloquent and persuasive to existing believers, but weirdly lacking to everyone else.

Theology hasn’t been able to budge from this position. Alvin Plantinga, one of the most renowned living theologians, concedes this when he says,

So, with no evidence even possible for gods, atheism’s right?

Theist philosophers have this one covered. Plantinga adds:

“But lack of evidence, if indeed evidence is lacking, is no grounds for atheism. No one thinks there is good evidence for the proposition that there are an even number of stars; but also, no one thinks the right conclusion to draw is that there are an uneven number of stars … Atheism, like even-star-ism, would presumably be the sort of belief you can hold rationally only if you have strong arguments or evidence.”

Plantinga’s a renowned Christian theologian, he’s dedicated his life to this, he’s emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, not some internet commentator schmuck, so I’ll take him at face value, and assume that it’s a good analogy for atheism.

One problem for Plantinga is that we can answer his question about stars.

At one level, he’s right. We encounter practical problems, to put it mildly, if we try to work out if there are an odd or even number of stars. The concept of ‘the number of stars’ is problematic. It assumes that it’s clear what a star is (that there are no judgement calls to be made about whether, say, a neutron star is a star, or whether a star that’s forming counts). Critically, the speed of light limits the available information. Even if we had some pressing need to count all the stars to work out if there were an odd or even number of them, we simply can’t acquire the evidence. This limit to our information also throws up the familiar problem that what we look at in the night’s sky is not the state of the universe ‘now’. It’s scientifically illiterate to imagine we could just take a snapshot of the universe and count the dots.

However … we can agree that however we’re defining terms, there are a finite number of stars, and the number of stars is a whole number. We can agree that any whole number is either odd or even. We can agree that the number of stars is, therefore, either an odd or even number. There’s a ‘right answer’ to the question.

We have, as far as I’m aware, no particular reason to think that there’s some law of physics governing whether there was an odd or even number of stars. There might be. Imagine the universe was and remained perfectly symmetrical. There would be, basically, two identical sets of stars. If one popped into existence on one side, another would on the opposite side. There would, by definition, be an even number of stars. As things stand, though, to the best of my knowledge, nothing like that is at work.