| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | November 11th, 2014 | next | |

|

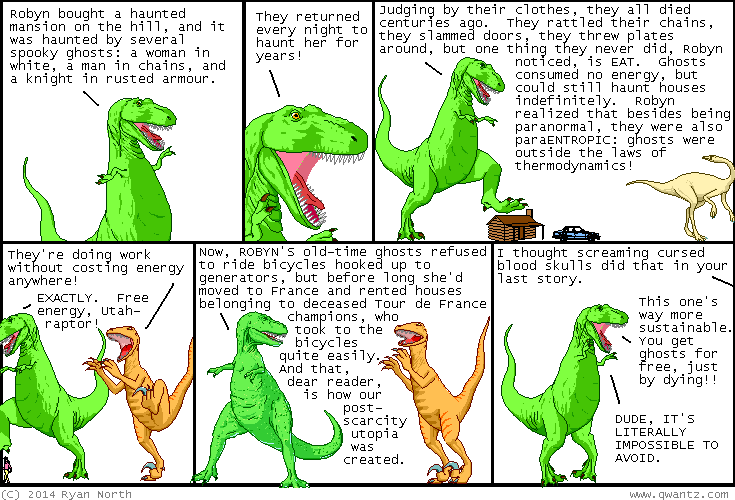

November 11th, 2014: CUT LINES:

Dromiceiomimus! Can I talk to you for a second?

YOU GUYS:

– Ryan | |||

Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

my name is an anagram for "horny rant" and imagine how great it'd be if it was an anagram for "horny ghost"? things would be different, i'll tell you what

Random Thing #4: Woss Going on 'Ere Then?

Think about it. What does every detective story have in common? The hero or heroine who can move as freely as they choose from place to place, doing what they wish according to their own judgements as they make those judgements, managing their own time, roving from person to person conducting interviews, or from scene to scene gathering evidence or perceptions, entirely under their own steam.

Sherlock Holmes hangs around in his rooms until he decides to take a case, whereupon he follows the scent wherever it leads. He makes money from his cases and doesn't do any other kind of work. Poirot similarly - when he isn't on holiday, that is. Like Miss Marple, Poirot is retired and financially self-sufficient. Other classic detectives combine one or more of these traits. Spade and Marlowe run their own detective agencies. Some detectives are aristocratic and wealthy, some live off their earnings, but they are all, essentially, either unemployed or self-employed. Even the police detective characters - Morse, for instance - manages his own time. He leaves his batchelor home and goes to work, but once on the job he and Lewis perambulate around Oxford as they please, stopping off in pub after pub, etc etc etc. Most detectives, like Morse, are single. Some are apparently asexual, some widowed, some divorced, some eternal bachelors, whatever. But they tend to live alone or with a same-sex buddy like Watson. The queer dynamic is often there, but usually non-diegetic. There are detectives with families or busy personal lives - Wexford, Bergerac, etc - but even they leave their domestic or romantic entanglements behind while on a case, and rove around freely instead. Often, in these days when cop shows have to include loads of dour and gritty stuff about how being a police officer harrows your soul and consumes your relationships, the detectives with family lives are resolutely miserable, those family lives being a catastrophic mess of some kind. They then leave the mess behind when they zoom off to investigate. In this case the pleasure of ditching the domestic may be furtive and guilt ridden (the trope of the cop's wife glowering when he gets a phone call that will take him away from her) but it's still there. Called back to work, he doesn't have to go and sit in an office. Whatever the fictional copper's notional complaints about paper work, the body of the story will see him or her cruising from suspect to suspect in a car. The appeal is of not being tied in some way in which most of us are tied.

The original fictional detectives were a focus of anxiety about transgression of privacy boundaries. They tended to be eccentric masters of disguise, or common-as-muck policemen who broke into the middle class home to snoop (like Mr Whicher). The detective story settled into such a popular staple of modern fiction when the detective was transformed from a figure of disconcerting and nosy instinct (i.e. Dickens' Inspector Bucket or Collins' Sergeant Cuff) into the bourgois man of leisure (Holmes). He stops being an uneasy mixture of proletarian and spy, and becomes instead a middle-class investigator-as-hobbyist-or-small-businessman.

Here's the secret fantasy. It works in a way reminiscent of the American fantasy about solving guilt-problems held over from conquest which lies at the heart of the American ghost story. American ghost stories are all, fundamentally, about disputed real estate. British ghost stories are, of course, far more about the haunting of the modern by the feudal. Both are about capitalism vs some flavour of pre-capitalism. The detective story is, transatlantically, about some fantasy of freedom from the capitalist organisation of time or, relatedly, from the schedules imposed by the bourgeois family.

The UPDATED Secret History Of Band Aid

The Secret History Of Band Aid

Everybody remembers Band Aid. And – despite everything – most people remember Band Aid 2. And now we have Band Aid 20 30. Which rather begs the question – why does nobody ever talk about Band Aids 3 to 29? Take a trip down memory lane as we remind you of the charity singles we all forgot.

Band Aid 3: Recorded in a secret corner of the Hacienda, “Baggy Aid” in 1990 melded social conscience with a wah-wah break and found Shaun Ryder offering to feed the starving his melons. That Line was sung by Bobby Gillespie, but nobody heard his reedy mewlings and the single flopped.

Band Aid 4: Top One Nice One! Altern8, Shaft, The Prodigy and many more superstars got together to give the classic tune a new boshing 90s sound – though it was B-Side “E For Ethiopia” that found favour with the DJ community. But a secret orbital party for famine relief was busted and the marketing juggernaut found itself turned back at a police roadblock.

Band Aid 5: Comedy was the new rock and roll, and 1992′s underbought effort saw Rob Newman and Bob Mortimer reading the lyrics to “Do They Know It’s Christmas” in funny voices for three minutes.

Band Aid 6: Rob out of Senser spat fierce rhymes over a vigorous backing from fellow agit-poppers Chumbawamba and Back To The Planet. “99p buys a bar of soap / Give it up and you can give them hope!” – but the public would not listen.

Band Aid 7: Liverpool superclub Cream hosted the recording of the seventh Band Aid, as superstar DJs like ‘Sasha’ and ‘Oakey’ retooled the classic tune for the dancefloor. “One of my appearance fees can feed a continent for a month,” said a house pioneer, “It’s humbling.”

Band Aid 8 and Band Aid 9: The blackest hour in the long history of Band Aid saw a schism as Blur and Oasis insisted on recording separate versions of the legendary song for Christmas 95. Blur’s video featured Keith Allen in a dress riding a desert goat and Oasis’ contribution ran into trouble when Liam punched Michael Buerk in the face. A disgusted public turned instead to Kula Shaker’s Crispian Mills, who promised to feed the world with his cosmic love.

Band Aid 10: “This year we’ve got a sixth member – Hungry Spice”

Band Aid 11: 1997′s Di Aid saw Jennie Bond and Viscount Spencer in a flower laden studio as Elton played a piano made from frozen tears. The public seemed all emoted out, but in retrospect letting Lord St John Of Fawsley do a rap was an error.

Band Aid 12: Who can forget the year Fatboy Slim played the biggest refugee camp party ever (it’s official – just ask Guinness). His version took the line “when you’re having fun” and looped it 500 times for a dancefloor classic – but with a message!

Band Aid 13: There was no Band Aid 13. But you bought it, you say? From where? But… but… there’s been no record shop there for forty years! And the man singing That Line, it sounds like… ELVIS!? NOOOOO!

Band Aid 14: Europe joined the party with Cartoons, Eiffel 65 and Aqua lending their sizeable talents to famine relief. “Come on Barbie, let’s save Mali”.

Band Aid 15: Radiohead’s “Kid A(id)” was more challenging than most interpretations, being a 17-minute video installation showing Thom Yorke being chased by a bear to the sound of a whimpering child. Retail response was sluggish.

Band Aid 16: The honorary BA 16 broke with tradition by being a version of “What’s Going On” recorded after the tragedy of 9/11. A panoply of stars contributed, including Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst, who rapped “we got humans using humans for bombs!”. Perhaps the most unlikely Band Aid yet.

Band Aid 17: “Get Ur Christmas Freak On” by the Freelance Hellraiser was the toast of the London scene for those two heady minutes in 2002. How we laughed.

Band Aid 18: It was becoming clear that the Band Aid brand needed a revamp. The appeal of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” was potent, but limited pretty much to December. There were eleven other months of the year in which famine could strike. And so was born “Tan The World (Let Them Know It’s Summer Time)”. “The people in Antarctica, they’re fuckin’ freezing” said an angry Geldof. “Tonight it’s Factor Ten instead of Two” sang Bono.

Band Aid 19: A fragile acoustic rendition of the song by Gary Jules really revealed the underlying quality of the songwriting craft. A rival waxing by The Darkness, “Christmas Time (Don’t Let The Pies End)”, made less impression.

Band Aid 20: Nothing happened this year. Certainly nothing involving Joss Stone. Or The Thrills.

Band Aid 21: The Crazy Frog’s ringtone version became a mobile smash. “Let them know it’s Crazy time, DING DINGDINGDING” said a Jamster spokesperson, “Though if you want something more tasteful, a Clanging Chimes Of Doom ring is available.”

Band Aid 22: Looking for teen appeal, producers turned to My Chemical Romance and Fall Out Boy. “Feel’s The Word” they crooned. The B-Side, featuring 30 fans reading out different definitions of Emo, found less praise.

Band Aid 23: A landmark year as the cream of British indie music – Scouting For Girls, the Kooks, the Pigeon Detectives, Razorlight – were flown out underneath the burning sun. Then left there. There wasn’t a record or anything.

Band Aid 24: At last, a credible charity single, as TV On The Radio, Vampire Weekend, Bon Iver, Black Kids and more formed BNM Aid. Sales were bafflingly poor. “Like, don’t they have blogs in Africa?” said a hurt Panda Bear.

Band Aid 25: Big Band Aid week on the X-Factor with twelve performances of the same song. Jedward’s enthusiastic routine as buzzing dayglo flies around a giant fibreglass child saw them safe once again. “It’s meant to be FUN, Simon.”

Band Aid 26: EDM stood for “Every Donation Matters” as David Guetta organised the “biggest drop in history”. “It’s not just about food, we’re sending out everything they need over there – medicine, glowsticks, mouse masks.”

Band Aid 27: Spotify’s Daniel Ek announced a new business model for Band Aid. “It’s Christmas time, and there’s no need to be afraid – of digital disruption” quipped the entrepreneurial Swede as he distributed one grain of rice per play of the charity anthem.

Band Aid 28: A beautiful advert about a boy and a baby vulture broke hearts and records for John Lewis, and helped Lily Allen’s emotive ukulele rendition of “Do They Know” soar high in the charts.

Band Aid 29: The year pop got a social conscience, and Macklemore stepped up to do his Band Aid duty. “People often say I look a bit thin, so I can speak for the starving. In a sense, we’re all Africans.”

Band Aid 30: In a last-minute attempt to stop a crisis – the release of a deep house version by Robin Schulz and Mr Probz – the world’s stars come together once again for Band Aid 30. “Buy the thing, don’t download it from iTunes”, said Sir Bob. “Bob, I already put it on their iTunes” said Bono.

(SERIOUS BIT: The need for a new Band Aid record is disputable, the need for medical aid in West Africa and elsewhere isn’t. Medecins Sans Frontieres donation page.)

Cory Doctorow: Information Doesn’t Want To Be Free

From TechCrunch:

The technical implausibility and unintended consequences of digital locks are big problems for digital-lock makers. But we’re more interested in what digital locks do to creators and their investors, and there’s one important harm we need to discuss before we move on. Digital locks turn paying customers into pirates.

One thing we know about audiences is that they aren’t very interested in hearing excuses about why they can’t buy the media they want, when they want it, in the format they want to buy it in. Study after study shows that overseas downloading of U.S. TV shows drops off sharply when those shows are put on the air internationally. That is, people just want to watch the TV their pals are talking about on the Internet—they’ll pay for it if it’s for sale, but if it’s not, they’ll just get it for free. Locking users out doesn’t reduce downloads, it reduces sales.

The first person to publish a program to break the digital locks on old-style DVDs, in 1999, was Jon Lech Johansen, a fifteenyear- old Norwegian teenager. “DVD Jon” took up the project because his computer ran the GNU/Linux operating system, for which the movie studios wouldn’t license a DVD player. In order to watch the DVDs he bought, he had to break their locks.

. . . .

In 2007, NBC and Apple had a contractual dispute over the terms of sale for Apple’s iTunes Store. NBC’s material was withdrawn from iTunes for about nine months. In 2008, researchers from Carnegie Mellon University released a paper investigating the file-sharing impact of this blackout (“Converting Pirates Without Cannibalizing Purchasers: The Impact of Digital Distribution on Physical Sales and Internet Piracy”). What they found was that the contract dispute resulted in a spike of downloads on “pirate” sites, and not just of NBC material—it seemed that once people who had been in the habit of buying their shows on iTunes found their way onto the free-for-all file-sharing sites, they clicked on everything that looked interesting. Downloads of NBC shows went up a lot, and downloads of everything else went up a little.

More interesting is what happened after the NBC-Apple dispute ended, and the shows returned to iTunes. As the CMU paper showed, download rates for those shows stayed higher than they had been before the blackout. That is:

- Refusing to sell their viewers the content they wanted in the format they preferred drove those viewers to piracy.

- Once the audience started pirating the content they wanted, they quickly turned to pirating other content, too.

- Having become aware of and proficient in the ways of downloading, the audience developed a downloading habit that outlasted the end of the blackout.

Digital-lock vendors will tell you that their wares aren’t perfect, but they’re “better than nothing.” But the evidence is that digital locks are much worse than nothing. Industries that make widespread use of digital locks see market power shifting from creators and investors to intermediaries. They don’t reduce piracy. And customers who run into frustrations with digital locks are given an incentive to learn how to rip off the whole supply chain.

. . . .

It’s harder if you’re a creator, because many of the biggest investors have bought into the idea of selling with DRM or not at all. When it comes down to negotiating DRM, you just have to make a decision about whether you’re willing to let your creative work be put in some tech company’s jail in order to make your investors happy, or whether you’ll keep shopping for a saner, better investor.

Link to the rest at TechCrunch

she called the woman in white "mary": a half-pun based on her dress looking like a wedding dress. mary didn't seem to mind, but it wouldn't get her on a bike.

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | November 5th, 2014 | next | |

|

November 5th, 2014: Here is a sequel poem I wrote to thank you for reading down here!

Sometimes it's hot outside

It's not QUITE as good as the other one and the "abcd" rhyming scheme has never been what I'd call super popular. I'll workshop it! – Ryan | |||

‘My bad’: Learning from the wisdom of the playground

There are no referees in a pick-up basketball game. Amazingly, though, pick-up games still work — they’re still fun and fair and enjoyable — because players learn to call their own fouls.

This is a skill, an ethos really, that you’ll see displayed wherever there’s a hoop and a ball and a bunch of people getting together to play. One key to making this work is an almost magical phrase: “My bad.” Admire the efficiency of that. It’s only five letters and two syllables, yet it communicates everything that needs to be said. It acknowledges the infraction and accepts ownership of and responsibility for that infraction. It accounts for the subsidiary matter of intent without allowing that to distract from the more pressing and tangible matter of the foul itself.

That pithy declaration — “my bad” — means that no further negotiation or litigation is required. The matter is settled and the game can proceed from there. I own the foul, you get the ball, we can get back to playing the game without any lingering concerns. Fouls happen in basketball. Admitting to one doesn’t make you a dirty player — a dirty player is one who never says “my bad.”

“My bad” can be just as effective, and just as important, off the court as well. Just as in basketball, it can be an efficient ritual: Accept responsibility, give up the ball, and then play on.

Outside of the context of pick-up basketball, though, we tend to make things more complicated. In the rest of life, we’re more likely to get bogged down in that secondary matter of intent. That’s understandable, because intent matters. But if we’re so intent on defending our purity of intent that we become unable to say “My bad,” then the game screeches to a halt.

Here’s a personal example: A while back I responded to some vile thing Rush Limbaugh had to say by quoting the title of Al Franken’s book. Like Franken, I was trying to punch up — trying to deflate this hurtful, hateful and harmful radio host and to subvert his damaging influence. But others called a foul. They pointed out that in trying to punch up at Limbaugh, my words were also landing punches down at other people who were hurt by those words.

My bad. My intent there mattered, but it was not exculpatory. My intent was precisely the problem — or, rather, the gap between my intent and my actual effect was the problem. There’d be no point in trying to argue about good intentions. If you really have good intentions, then you can only be aghast to realize that your effect contradicted those intentions. My intent may not have mattered much to those who were hurt by my words — they were, rightly, primarily concerned with the effect of those words. But to me, it mattered a great deal that I had failed to achieve my intended effect — that I had, in fact, achieved its opposite by punching down instead of punching up.

Good intent, if it’s actually good intent, compels one to correct the disparity between intent and effect. If you’re shown such a disparity and your only response is to defensively reassert the goodness of your intent, then you’re demonstrating that you don’t care about the effects of your words or actions — which is to say, you’re demonstrating an utter lack of good intent.

I want my intent to align with my effect. That’s what “intent” means. So I took a cue from pick-up basketball and owned the foul. My bad.

Munchausen Weekend

Interstellar

Spoilers, I guess? If you care? I don't think the shelf life for discussing this movie is going to be very long, if that matters.

If you don't like Christopher Nolan, this isn't the film that's going to change your mind. Take me for example: I don't really like Christopher Nolan. He learned all the wrong lessons from Stanley Kubrick and makes films that look great from straight-on but are revealed to be resoundingly hollow the moment you change your perspective. With Interstellar he succeeded in making a film that I really wanted to like despite all my past experiences with the man, but which let me down because it ultimately refused to cohere as anything other than a Christopher Nolan film.

I wish I could remember where I saw this . . . an interview? One of his afterwards? There's a great bit from Stephen King where he talks about themes in stories. He says that you should never put themes in stories, but that the themes should arise naturally from the story you're trying to tell. That is fantastic advice. Obviously not always completely applicable, but, it's a bit of advice that more screenwriters could stand to learn. Because Interstellar? You know this was a story that began theme-first. You know it did. The reason you know it did is that, as with every other movie Nolan has ever made, the theme is the only truly legible thing about it, even if it makes no sense (more on that in a minute). As with Inception, as with all his Batman movies - they're great at establishing and developing themes, completely terrible at every other part of telling a story. He's a great, fantastic, filmmaker but an awful storyteller. And if he hasn't yet figured out the difference yet, having made a number of the most successful movies ever, he may never.

Which may partly explain why, time and again, given the most interesting subject matter with which to play around, he unerringly finds the least interesting part of whatever subject matter he has at his disposable. Given Batman, he gravitates towards a dull brown and steel gray palette, gives us a gritty urban Batman set in freakin' Pittsburgh, and figures out the precise way to make all his villains as surly and mundane as possible. Bane's voice was the best part of The Dark Knight Rises because it was the only part that felt remotely fun and interesting. Inception was awful because, given the opportunity to make a movie about dreams, he made a dream movie about a heist movie with all the visual appeal of a Pierce Brosnan-era Bond flick. Nolan has yet to meet a fantasy genre he cannot somehow drag through the mud of oblivious banality, and you can now say the same for space opera.

Tell me you are making a film about space travel and the first thing I want to know is, how much time are you going to spend hanging out with farmers? Because the amount of time you spend hanging out with farmers is going to be inversely proportionate to the amount of time the movie spends doing interesting things. Someone at some point told Nolan and his screenwriting bros that all movies need to begin by establishing the human stakes of any narrative, and that requires spending a half hour to forty five minutes telling us about dust and famine and dumb ass crackers. The movie is about space ships. I can see the script wheels turning: we need to establish our characters. We need to establish our setting. We need to establish our conflict. We need to do all of these things as methodically as possible. Because, you know, the audience just will not know who to root for if we don't spend all this time telling them about the main guy's family and hardship and all that stuff. We're going to mistakenly start rooting for the robots because we haven't been given enough reason to think that Matthew McConaughey is interesting or important enough. Well, guess what: I rooted for the robots anyway because every motivation in your entire movie was as boring and predictable as the proper indentation on your screenwriting software. The robots, at least, were interesting, something I really hadn't seen before. Give me a whole movie about those awesome robots.

This belief that the human story is the most important element of whatever story you're trying to tell is erroneous and deadly. The audience doesn't need a human stake. The audience can figure out what the stakes are by seeing the characters do thing - not by seeing the movie spend 45 minutes running in place telling the audience what the stakes are. The audience isn't stupid enough that they need to be told that Matthew McConaughey is a human being with real feelings. You could cut out a great deal of the Matthew McConaughey Is Sad and Frustrated preamble and be left with a lot more than you think. Setting up your human characters with such painstaking and tedious emotional exposition is simply condescending to an audience you do not believe to be smart enough to understand the movie. And yet everyone does it.

Also while we're on the subject of what everyone is doing (so why can't we?), everyone is so far comparing this film to 2001. OK. If you want to play that game, it's not a game that works in Nolan's favor. How much time does Kubrick spend establishing Dr. Bowman's motivation? He goes right from a monkey throwing a bone to a spaceship flying through Earth orbit. Any contemporary screenwriter would tell you that you needed to spend twenty minutes establishing David Bowman's family life and relationship with his wife or girlfriend, and a relationship with some kind of father figure who relates some kind of wise koan whose meaning will only be understood in the film's final moments. (2010 does a little bit of this, it should be noted. Another unfair comparison.) Spending so much time giving us so much of Matthew McConaughey's motivations has the perverse effect of making him seem undermotivated: his motivations, such as they are, are actually kind of stupid. Drilling them into our heads again and again doesn't make them any less stupid. Maybe they're "relatable" in Hollywood-speak. But they're stupid.

(This makes for a great point of comparison with Transformers 4. That movie spent a little bit of time on Mark Wahlberg's motivation, but really, just enough to get you going. And the fact that Wahlberg's motivations stayed precisely the same throughout the entire running time of the film despite the fact that the fate of the world was at stake was awesome, and an attention to detail of the kind that Nolan can only hope to conjure. I have to stand by any movie that makes sure to tell us that the main human character is more concerned with his daughter losing her virginity than the fate of the world. It works better than all of everyone's motivation in Interstellar because it at least doesn't ask us to voluntarily lower our IQ in order to believe that real people might ever in a million years have emotions like these.)

What I've seen discussed less than Kubrick is the obvious debt Interstellar owes to Terrance Malick. There are scenes straight out of Days of Heaven - I mean, really, if you're going to burn a field, you better know people are going to pick up on that one. It's hard to imagine what this movie would have been - whether it could have been anything - in a world without Tree of Life. It's not just the presence of Jessica Chastain that drives that one home. Every time Nolan brings the music up, lowers the sound on the dialogue, and slides into a montage - particularly on Earth - you can't help but see, immediately, the seams of Nolan's construction. The themes in Interstellar have been carried over lock, stock, and barrel from Tree of Life.

Part of the problem is that, philosophically speaking, the movie doesn't have a brain cell in its head. Malick is a heady filmmaker in part because he is a philosopher. When he uses Heidegger to structure a film like Tree of Life, it makes sense because it's coming from a place of deep understanding. The problem with Interestellar is that, while Nolan pays a great deal of attention to his themes, he doesn't really understand them. He papers over his lack of understanding with some trite bullshit about the power of love, and that just doesn't cut it.

Early in the film Matthew McConaughey explains to his daughter the meaning of the phrase Murphy's Law:

Murphy's law doesn't mean that something bad will happen. It means that whatever can happen, will happen.This would appear to gesture towards the establishment within the film of a Humean world of absolute contingency. But in practice, the film - supposedly about the limitless possibilities of space travel - devolves into a closed-loop time travel narrative, an intricate structure of precise causality monitored by fifth-dimensional beings unhindered by our concept of time. Nolan as a filmmaker is unable to move past the closed loop: despite every opportunity to the contrary, he is unable to break free from the gravity of necessary causation. He is addicted to symmetry, and his movies suffer. His world remains doggedly, persistently Kantian. The frustration at the heart of the narrative - the inability and unwillingness to break free from necessity - could have been fixed by a copy of After Finitude.

Where is this radical contingency, the sensation that "whatever can happen, will happen"? Nowhere to be found in Nolan's film. The visual effects, while nice and occasionally breathtaking, are still nothing particularly new. Instead of grasping the opportunity to give us something new, Nolan gives us a brief flight through subspace, a handful of monoclimate planets, and finally a trip into the heart of a black hole. Maybe I'm jaded, maybe I should have approached the film from the perspective of someone who had never seen a sci-fi film before. Because that is unfortunately necessary in order to accept that this is at all visually interesting. My immediate takeaway from the film was that Nolan is a filmmaker who loves making sci-fi movies but dislikes sci-fi, and the lack of imagination on display here - a water planet with big waves! an ice planet with glaciers! - speaks to a larger lack of motivation. It all makes sense for the story, yes, that these are useless planets with no appeal, but that brings us back to Nolan's motivation at the heart of the movie - with all the resources of the most technologically advanced movie-making apparatus in history at your disposal, this is what you choose to show us? Ice Planet? Planet Waves?

I understand that some attempt was made to keep much of the film's science close to something we could reasonably call "hard sci-fi." In practice what this often (not always) means is that they take all the fun stuff out of the genre in exchange for people explaining why they can't do things. The film gets some play out of the divide here (in another echo of 2001), establishing that humans are limited more or less by the capabilities of real-world science, while the mysterious beings who give Earth the wormhole are not bound by the same laws. What we get is the hand-wave that the fifth-dimensional beings who set the plot in motion are able to do things - such as play with the laws of space-time as if they were taffy - that otherwise are impossible according to the laws of the universe. But after we establish that, the movie should obviously be heading towards some kind of revelation regarding these mysterious beings. 2001 gets around having to explain what the monoliths are and who built them by giving us instead more deeply intriguing questions, until finally ending the movie on a note of supremely satisfying mystery. There's no mystery in Nolan's universe: the question of who the mysterious beings are is answered by Matthew McConaughey in a toss-off line, with no real explanation as to how he came to that conclusion. Nolan can imagine blasting off to distant galaxies, but he can't imagine finding anything to look at more interesting than a mirror, and no mysteries more bewildering than the human heart.

For point of comparison, look at Contact, a movie that only gets better with every passing year. There was a movie with a startlingly similar premise that stubbornly refused to wrap everything up in a neat package. It also had Matthew McConaughey, which proves again that even though I get older, these actors stay the same age.

Maybe that's what some people want to hear. Maybe the fact that the movie essentially ends by reiterating that "the fifth dimension is love!" is a great way to end a movie in 2014, reassuring the viewing audience that regardless of how scary the universe may be we can stay grounded by sticking close to our good old fashioned down home values. I do like the fact that Anne Hathaway gives a big stupid speech about the power of love right before being shot down by the more pragmatic Matthew McConaughey - even if she is later revealed to be right because love will keep us together. No matter how big space is . . . and while we're on the subject, why did the put the wormhole next to Saturn? If they wanted humanity to use the wormhole to save civilization, why not put it somewhere closer? Like, say, anywhere closer than Saturn?

Also: the twist about halfway through the movie is the exact same twist as was in Saving Private Ryan. It's like all the filmmakers in the world looked into the heart of America and decided that the thing we most wanted out of our movies was surprise cameos by Matt Damon. I did warn you there'd be spoilers.

Reverse Racism ('Into the Dalek' 2)

Ironic, fairly interesting, and doubtless intentional.

But there's another interesting irony here, which probably wasn't intended.

As has been frequently pointed out, SF often falls into the trap of a race essentialism. Alien races in SF all have the same characteristics. The same sort of thing is true in Fantasy, and in other forms of storytelling featuring sapient non-humans. All Vulcans are logical, all Sontarans are militaristic, all House Elves are servile, all Orc are psychopaths, etc. The problems with this are obvious. It rests upon a reductionist view of race, society and sentience... not to mention a set of assumptions directly related to biological racism. But that's all obvious, and well covered elsewhere.

Back to the unintended little irony in 'Into the Dalek'... which, to be fair, is more an irony about the Daleks themselves. No, not the irony of creatures which metaphorically express the evil of racism themselves being based on race essentialism. I'm not really talking about race here. I'm talking about politics.

Because, as is also well understood, the Daleks are metaphors for the Nazis. Actually they hardly even bother being metaphors.

So we wind up in a peculiar situation politcally when we question the idea that there is something wrong with assuming that all Daleks are evil (an assumption that 'Into the Dalek' more or less explicitly questions). We wind up essentialy questioning the idea that all Nazis, all fascists, are bad. But you see... they are. By definition. The DWM review of Timewyrm: Exodus said that Hermann Goering was the closest thing to a nice Nazi (a pretty startling remark if you know anything about the man). But you can't have nice Nazis. You can't even approach that. It's like talking about dry water - if it's dry, it ain't water.

We have bumped up against a standard misunderstanding about discrimination. It isn't something that can happen to anyone or everyone. There's no such thing as 'reverse racism', or 'misandry' (at least as the term is meant by the crybabies who object to feminism on the basis of their bruised manfeels). There certainly isn't any such thing as unfair discrimination against fascists. That's why they shouldn't be allowed on Question Time, no matter how many people vote for them. You can't have democratic fascists. Obviously, therefore, you can't extend them the boons of democracy. I'm not in favour of banning fascist parties or imprisoning fascists - because it would be counter-productive - but it isn't an unreasonable idea in itself.

(Similarly, I don't think its an unreasonable idea in itself for capitalist democracy to lock me away too, since I've repeatedly voiced my desire to see it destroyed... though it makes considerably less sense than locking fascists away, since my dissatisfaction with capitalist democracy is based on a rejection of its own rhetoric about democracy, and a demand for more democracy, whereas the fascist objection to capitalist democracy is based on a desire for less democracy.)

My saying that it is right to discriminate against fascists certainly doesn't make me as bad as a fascist. That's wishy-washy, purblind piffle. That idea rests on a false equivalency, like many liberal cul-de-sacs. The eternal phantasm of the level playing field, the balanced middle-ground; the idea of the centre as the rational point between irrational extremes, and fairness as the equidistant zone between claims. All that childish, politcally-illiterate shit.

You don't become a fascist when you discriminate against fascists; you become an anti-fascist... just as you don't become a sexist when you challenge patriarchy, or a reverse racist when you challenge white privilege.

Of course, it might be objected that you can label everyone who ascribes to a political philosophy 'bad' without accepting that it would be a good thing if they were all killed... and you'd have a point. But it's still interesting that, even today, we are more comfortable playing around (albeit questioningly) with the reading of the Daleks which is based on race essentialism than on the reading which is based on political philosophy... even when they openly represent a political philosophy that 'we' supposedly all despise.

The Fall of the Wall, twenty(-five) years on

nwhyte at The Fall of the Wall, twenty years on

nwhyte at The Fall of the Wall, twenty years onI first went to Berlin in 1986, over the long weekend of German Unity Day which was then on June 17, hitch-hiking there with a friend who I was working with in Heilbronn way off in the southeast. In those days Berlin was a slightly hippyish enclave (the hostel we stayed in was very hippyish and slightly threatening) on the front line of the Cold War. The inner German border remains the most vigorously fortified frontier I have ever seen. We went east as well as west (by tram to Frieedrichstraße), and took pictures of the Brandenburg Gate from both sides which I guess I must still have somewhere; I went to an eastern bookshop and made the mistake of referring to "Ost-Berlin" (rather than "Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR"). At that point the Wall had been up for almost 25 years and looked like it would remain a lot longer.

I went back with Anne in 1992. It was utterly transformed, of course. I cried as we walked through the Brandenburg Gate, which had appeared so utterly blocked by historical circumstance and concrete fortification only a few years before. The west of the city had found a new security and confidence, a strong sense of libeartion; the east was still shell-shocked by defeat. The transport system, now unified, charged considerably less to former easterners buying tickets. The frenzy of new build was just getting going but the momentum wasn't yet there. Since then I've been back perhaps half a dozen times. Earlier this year I took an afternoon to retrace the Wall, helpfully marked out by bricks in the road. It remains a fascinating city for me, and every time I go I find something new.

The BBC has a handy list of walls that remain, including two of which I have direct experience (Belfast and the Green Line in Nicosia) and another which I work on (the Moroccan berm closing off the illegally occupied part of the Western Sahara). Just as the Berlin Wall disturbed me in 1986, any restriction like this disturbs me now. Robert Frost wrote "Something there is that doesn't love a wall"; his New Hampshire boundary markers were threatened by natural forces, perhaps elves, built by old stone savages. The conflict-built walls of the world are also perpetually under threat from the erosive force of history. And a good thing too.

Some thoughts on Ed Miliband and Labour’s prospects

Can you trust any ‘new leader’ polling?

So, we now have polling that shows that having Johnson, Umunna or Burnham would give Labour a bigger lead in the polls right now. Anthony Wells often counsels against putting too much faith in any ‘how would you vote if..’ polls, and I think that is the case here. Voters may well take a ‘grass is always greener’ approach to any suggestion of change, but no one has any idea just how people will react should the Labour leadership change. When people have no idea how someone will actually perform as leader, it’s not a good idea to rely too much on their judgements of how they will vote in a hypothetical scenario.

That said, I do wonder if changing the party leader could have an interesting effect of poll shares by changing the likelihood of party supporters to vote. That’s a question that I’m not sure is ever asked in the hypotheticals, but for me could be a key factor. I’ve said before that I think a lot of UKIP’s success is down to the fact that they can motivate their base to vote better than the other parties, and I wonder if a new leader would motivate Labour voters more – the lesson of Heywood and Middleton is that Labour do seem to have a motivation problem.

Where can Labour get votes from?

Anthony Wells’ excellent diagrams of vote shifts reveal the problems all the main parties are having in holding on to voters in an extremely volatile political environment. The question they pose, though, is where are Labour going to win the voters they need from? They’ve shed votes to Greens, nationalists and UKIP, and it’s hard to see the strategy that can draw voters back from all three of those. Is drawing a small percentage of voters back from the SNP (with the possible benefit of protecting all those Scottish seats) a viable strategy? Or does the party need to be looking at how they draw more voters back from the non-voters, and hope gains from there can dwarf any losses?

Young cardinals, old popes

Alan Johnson is the perfect king over the water because he hasn’t been assembling a faction around him ready to take the leadership, and so all the Shadow Cabinet members who have can step aside in his favour, ready to go for it the next time. (I suspect their scenario imagines Johnson as a one-term PM, with the real leadership contest in 2019/20) However, is it necessarily in the interest of the more established contenders like Yvette Cooper and Andy Burnham to take a pass this time? Putting their ambitions on hold for five years would give the next generation (Umunna, Reeves, Creasy et al) plenty of time to stand out and shine, and give Prime Minister Johnson a real influence through Cabinet appointments and the rest in who gets to follow him.

What if?

We’re in a very strange time for British politics, one that’s certainly unlike anything else I’ve seen in my lifetime, where all of the established parties are under threat. In this position, Labour ditching Miliband would have inevitable knock-on effects in the other parties. If he goes, that’s just the beginning of the story: suppose a new leader does open up a poll lead for Labour, while UKIP win the Rochester by-election. That seems likely to trigger more Tory defections and/or more calls for Cameron to quit. Given the volatility of the polls, and the variability in shares across the pollsters, it’s entirely possible in that scenario for us to see a poll (however rogue) that puts UKIP in second place and the Tories in third. Could Cameron survive then, and what would be the effect of the Tories trying to replace a sitting Prime Minister a few months before an election when one of the leading candidates to replace him doesn’t have a seat in Parliament.

We live in interesting political times. I look forward to when the historians of the 2030s get to tell us just what was going on, because I’m not sure we’ve got much of an idea right now.

Recommended Reading

Bruce Bartlett, who was a policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and also worked for the first President Bush, explains why Barack Obama is actually a Conservative. I don't completely buy this argument but I sure agree that he's accomplished a lot of things that Republicans would have thought made him The Greatest President Ever — greater than Reagan even — had they been done by a Republican. (To get some to that view, he'd also have had to have been a white Republican.)

If all a Republican president had accomplished was the deficit reduction charted in Bartlett's piece, the G.O.P. would have started clearing brush on Mount Rushmore to add another face. If that president had also presided over the killing of Osama bin Laden, they would have dynamited the four likenesses already there so they could make the new one bigger.

Norman Baker "accomplished more in one year ... than most people do in their entire career"

Ian Dunt gets it spectacularly right on politics,co.uk.

First on Norman Baker's achievements in his year at the Home Office:

Baker accomplished more in one year in the Home Office than most people do in their entire career. Baker went into the Home Office as the Liberal Democrat's man. He performed that task with aplomb, forcing through an international study of drug policy - an investigation long-resisted by the department because it suspected it would show its policy caused harm. ...

Baker fought the battle over that report behind the scenes for months. The department refused to publish it. The civil servants involved in writing it were blocked from making any recommendations on the basis of their findings by the prime minister. The establishment is terrified of any accurate assessment of British drug laws.

Baker eventually succeeded in forcing publication. It was arguably the most important government drugs report for a generation. It found that half a century of drugs policy was mistaken. Harsh drug penalties do nothing to reduce drug use, but they do significantly reduce the health of drug users.

Against a hostile media, dogmatic Labour and Tory MPs, and a hugely bureaucratic department, he had scored a significant victory. It will be mentioned as a key moment in the drug debate when, a decade or two from now, Britain finally adopts a more liberal policy.One might add that Norman was highly regarded in his time as a transport minister too. And, as the video above shows, he sings too.

Second, he is right about the silly attacks on Norman today:

The attacks on Norman Baker could almost have been pre-written. As soon as his resignation was announced, his critics reminded everyone of his weakness for conspiracy theories. Videos of his band were circulated, mockingly. Others focused on the fact no-one outside the Westminster bubble knew who he was, which is true for pretty much all ministers. And there was criticism of his admittedly theatrical astonishment at the fact the Home Office does not proceed on the basis of evidence.Among those making the attacks are the Guardian - though note the supportive comments from readers and and even a Lib Dem blogger.

And Dunt is most right of all when he contrasts the reputations of Norman Baker and Jeremy Browne.

I am too much of a party loyalist to quote what he says about Jeremy, but the moral he draws is spot on:

And yet Browne was treated almost like an elder statesman when he left the Home Office. And therein lies the key to media treatment of politicians: Look vaguely presentable and don't rock the boat – they'll treat you like a sage. But fight for radical policy and they consider you an embarrassment.

Baker accomplished more than most ministers one can care to think of. It is entirely unsurprising that he is now a subject for mockery.My suspicion is that the worlds of politics and political journalism are now so dominated by the products of public schools and Oxbridge that they find the idea of someone from outside playing a role ridiculous.

Alan Moore Interview, Part V: Underland, Hancock, Jerusalem, Literary Difficulty

The fifth and final part of my Alan Moore interview.

As I was finishing up the book, I was re-reading an interview with you [in Reflex, December 1991] and there was a one line reference to a project called Underland that I’d never seen mentioned anywhere else.

That may even have been a follow up to A Small Killing for Gollancz. Somewhere around that time. I had a book called London Under London, that Neil Gaiman had sent me when I was researching From Hell. I wanted to do something with Steve Parkhouse, and I came up with the idea of a subterranean world under London that linked up all these interesting underground spaces and had its own inhabitants and its class system. It was going to have a girl whose sister had vanished, been spirited away into this underland, and the girl – I meant it as a grown up children’s story, the adventures of this girl exploring this world and finally rescuing her sister. The same length as A Small Killing, something like that. I mentioned this in that interview and I got a phone call from Neil Gaiman saying he’d signed a deal with Lenny Henry’s production company to do Neverwhere. Given that Neil had sent me the book originally, I felt duty bound to say ‘oh well, you were here first, so I guess I’ll forget Underland’.

You’ve not done many children’s stories, is it a genre that appeals?

I submitted a proposal, I forget who to, to someone who was looking for a children’s book. This was prior to Bojeffries. It was about an unprepossessing, oddly willful child like a younger Ginda Bojeffries who was a belligerent genius who could have adventures on the Moon. It wasn’t what they were looking for, they wanted something for very young children. I got the impression I wouldn’t be that good writing for young children, I’m a tiny bit bitter and ironic. That said, Blanket Shanty with Shawn McManus, that was a Tom Strong story done as a bedtime story.

You’ve got Timothy Tate and Lobelia Loam in 2000AD …

They were still horrific stories. Blanket Shanty was aimed at small children … I probably could do children’s material in the right circumstances. Whether I’ll get round to it now, I don’t know. I avoided it for a while because it was trendy. I like some of the things about children’s stories, but I didn’t want to be jumping on a JK Rowling bandwagon. The whole middle section of Jerusalem is about a gang of children running around time in a four dimensional afterlife. It reads like a children’s book, but it’s not because it’s a much stranger story, it’s adult, it’s not meant for children.

One thing I can’t work out is where your music fits in. Clearly some of the recent work is linked to the magical … project, if that’s the right word. But with things like the Emperors of Ice Cream, is that a hobby, is that you letting off steam, or is that part of your serious artistic endeavours?

I’m basically still at the Arts Lab, it’s just an incredibly enabled Arts Lab with whatever contributors I want. With the Arts Lab all of my needs to express myself, all my urges, had an outlet. I could do comic strips, I could do poetry, I could do music. My emphasis has had to be on writing, but I’ve never abandoned drawing or performance. There’s never been a need to. I don’t define myself purely as a writer. ‘Magician’ is a handy word, as it’s almost the same as saying ‘artist’, but artist sounds so pretentious. Like Tony Hancock in The Rebel. My approach has always been the same, and I’m more mature and capable, but it’s the same impulse.

I don’t feel I’m part of the comics industry, any more than when Jerusalem is done I’ll feel like I’m part of the literature industry. I certainly don’t feel part of the music or film industry. I am probably at an Arts Lab in my head. An enthusiastic amateur. Yes, I get money for it now, but in my heart I’ll always be an amateur – someone who does it for the amour, for the love.

So, do you have hobbies that aren’t artistic?

(Laughs) No. I don’t have time for anything other than reading, and that generally ends up being unexpected research. Just read a book today, by my friend the magician Joel Biroco, A World of Dust. Interesting, really good stuff. I continue to enjoy books and the very occasional film. The last enjoyable film I saw was A Field in England. So, I don’t really have hobbies. I’ve taken to going for walks lately, generally with Alistair Fruish, a very knowledgeable young man, we have walks all around Northamptonshire. I’ve known him since he asked me back to the Grammar School to talk to the kids. He works in the prison system now, he took me over to Wellingborough nick a couple of years ago, the lifers. They don’t get much entertainment, but I’ve apparently got a strong part of my readership inside. And these are ordinary blokes who had a really bad day and did something fucking stupid and after that point they would never be ‘not a murderer’. For the rest of their lives they can’t ever be ‘not a murderer’.

The other day, on a riverside in Northampton, Alistair and me found the source of the industrial revolution and capitalism. Check out the cotton mill founded in 1741, the first powered mill in the world. So there’s the birth of industry. Adam Smith heard about it or visited it, and said ‘all these looms work without anyone to manage them, it’s almost like an invisible hand’. So that’s the central metaphor of capitalism.

[Discussion has turned to Jerusalem, a massive novel Moore has been working on for many years which is set in Northampton.]

You’re nearly finished?

I’m on the last chapter, but then there’s an epilogue. So about one and a half chapters to go.

What are your hopes for it? How do you think it’s going to be received?

With Jerusalem, I embarked upon it purely because it was the book I wanted to write. It’s about the neighbourhood I grew up in and its very fascinating history, also the history of my family in the area which has its unusual side. Lots of lots of fantasy is mixed in there, and theories of the nature of time and life and death. When I was speaking to Melinda [Gebbie – Moore’s wife (and the artist on Cobweb and Lost Girls)] about it, she very perceptively said that it sounded to her like ‘genetic mythology’, and I thought, after all why should it be only aristocrats and pharaohs and monarchs that have genetic mythology? Shouldn’t people in slums be entitled to their own? So that was part of the urge, and in writing it, I realised that this is exactly the novel I wanted to write.

I am really proud of it, I think it’s sensational. That is, of course, just my own opinion. I am aware that conventional criticism will probably say that it’s about ten times too long, that it’s difficult in places, that some of the passages were deliberately alienating.

Actually I’ve just discovered – I’ve been reading lots of books of literary criticism, mostly about HP Lovecraft to do with Providence, which is a really big job that I’m about halfway through. My armchair is walled in with Lovecraft reference books, I’ve got everything. And I’m starting to pick up ideas from literary criticism, which I’d previously dismissed as poncey because I hadn’t seriously looked at it.

The concept of ‘literary difficulty’ – doing something that will put off a percentage of the audience but will force those who remain to engage with the work on a deeper level. It will challenge people. Now, if I’d had that concept before I’d written the first chapter of Voice of the Fire [told as the first person narration of a Neolithic settler, using a limited vocabulary], I’d have done it exactly like I did, except even moreso. That’s exactly what I did it for, even though I couldn’t have explained it like that.

There will be elements of literary difficulty with Jerusalem – actually lifting the book will be among the difficulties. It’s going to be a very forbidding book in terms of its sheer size and because it’s about the underclass. There is no better way of ensuring that you don’t get a readership of your book than making it about underclass people. In the current climate getting any fiction published is difficult.

I can take unfair advantage of my position. Only I could do this, only I could spend eight years of intense work on it, only I could actually recount what happened in that neighbourhood with those people, and only I am in a position where I could do that without worrying about getting it published. I don’t need to go with a big publisher, they don’t really have anything to offer me. It’s not a big, popular book or a beach read, I’d much rather have a small publisher who had some understanding of what I was doing.

The only ambition I have for Jerusalem is for it to exist. I’m under no illusions that anybody is going to say this is the greatest book of the century. No, no, it’s probably far too difficult for that. It’s just an accurate expression of part of my life and part of my being that also includes lots of other subjects that have become part of that: history, economics, poverty, the Gothic revival, the Gothic movement which started in Northampton with James Hervey, Charlie Chaplin, wars and ghosts, psychological and factual. Family and famous people who’ve passed through this neighbourhood.

Beyond that, fate will have to take its course. I don’t have another prose novel in mind after this. Maybe a really big poem at some point in the future, I have an inkling for one. There’s more League stuff, there’s the book of magic, there’s Providence which I want to be – in my terms – the definitive Lovecraft story. Then there are the films, we’ve got the Kickstarter money for that, and then there’s the possibility of a feature film and TV series after that, both called The Show. Pipe dreams at the moment, they may not come in to land. But a lot of things that have been brewing for years are falling into place.

Mashable Facts

The folks at Mashable have put up a video — which I think is new but I'm not sure — called "5 Facts About Batman (with Adam West)." I've embedded it below.

The first one is about how Bill Finger really created Batman and not Bob Kane. I absolutely agree that Finger has been tragically, almost criminally deprived of recognition for his work. (I am, let us remember, the Administrator of the annual award that bears his name because the comic books and movies of his character do not.) However, there are two large problems with the Mashable video…

- They woefully understate Kane's contribution when they say, "All he really did was drawn a blonde guy in a red suit with bat wings." Well, no. First off, the drawing they show of what folks will assume is Kane's contribution is actually a speculation on what Kane's design might have looked like. I believe my pal Arlen Schumer did this drawing a few years ago. Secondly, Kane also sold the strip to DC Comics and worked quite a bit on the early stories. I don't think any of that makes him the sole creator of the character — others did as much or more — but he did a lot more than that one drawing that's actually by Arlen. He did, for example, a lot of drawings that were actually by Jerry Robinson. (No, seriously, Bob did do a lot of drawing and head up the crew that produced the early material.)

- They say "Finger got no recognition" as they show a photo that they think is of Bill Finger. It's actually a photo of DC writer Robert Kanigher…and I think I know how they made this mistake. The Bill Finger Award goes each year to some writers who, like Finger, have not received proper recognition. Last year, one of the ones who received it was Robert Kanigher. I obtained a photo of Kanigher from his family, did a lot of retouching on it to make it look decent and used it on my site and in our press releases. Obviously, someone at Mashable did a search for "Bill Finger photo" or something of the sort, that pic came up and they grabbed and used it.

So once more, Bill Finger is not receiving his proper recognition. And I don't consider it a welcome change that Bob Kane isn't, either. Here's the video. Adam West's participation is, uh, interesting…

UPDATE: A few folks have written to ask me about the claim in this video that Bill Finger created The Joker. Well, Bob Kane claimed that Finger created The Joker and Jerry Robinson said Jerry Robinson created The Joker working with Finger and I believe the weight of evidence is on Robinson's side. So Jerry was a bit wronged here.

Us vs Gallifreybase vs Th3m

So, in the wake of Dark Water, the site usvsth3m ran a piece entitled "16 sexually confusing feelings that Doctor Who fans have had since The Mistress revealed her secret." It's a fun piece that reveals the pathetically blinkered attitudes of a lot of Doctor Who fans for what they are, which is to say the attitudes of sexist, homophobic, and transphobic assholes. It's a sobering reminder of the at times appalling attitudes of orthodox and longstanding fandom, and was absolutely something worth doing. And to their credit, they played nice and clipped usernames, thus avoiding publicly naming and shaming people for their actions, not that publicly naming and shaming the person who said that they felt "as though something sacred has been violated" because the Master was a woman now would have been in the least bit unreasonable.

Which is probably why the forum tried to demand that the site take the article down and banned the writer over it on the supposed grounds that they're a "private" forum and that one needs permission of people to quote their posts off-site. Like the entirely sensible people they are, usvsth3m aren't backing down in the least, and more power to them.

But let's be clear here. GallifreyBase's claim that they're a "private" forum is absolutely ludicrous given that they have open registration and nearly 80,000 members, which is to say, about the entire population of Bath. The forum is private in the same way that the Jumbotron at Yankee Stadium is private, except that Yankee Stadium only has a capacity of about 52,000.

What this amounts to is the largest single community of Doctor Who fans declaring that they have the right to have their views go uncommented on and unreported on. It amounts to a declaration that scholarly research and ethnography on Doctor Who fandom is forbidden. It amounts to a declaration that journalists can't cover Doctor Who fandom. It is a morally indefensible position that actively aims to have a chilling effect on entirely legitimate topics of media research and journalism.

I'm sure that many of you are members of GallifreyBase. If so, please use their Contact Us form to tell them your views on their efforts to stifle freedom of speech.

And seriously, check out usvsth3m. They're a lovely mixture of fun "wants to go viral" content and leftist politics. And really, in a war between a cesspit embodying the worst aspects of Doctor Who fandom and a site with an interactive "Slap Michael Gove" game there's only one side you can possibly be on.

Back tomorrow with the start of our coverage of the fantastic "Swamp Thing attacks Gotham City" arc.

Norman Baker, political journalism and hinterlands

It’s an odd evening to defend the MP for Lewes, given that his constituents are currently behaving like a bunch of spoiled children blacking up and attempting to set fire to “politically incorrect” effigies. Nonetheless, I share a lot of the views expressed elsewhere that he performed an excellent service in his role as Home Office minister and can well understand his reasons for resigning.

This blog post isn’t about the rights and wrongs of his resignation though. Rather, it’s a simple observation. Most of the media coverage was transfixed by the idea that Norman Baker was in a band, that it isn’t a wildly good one, and that these facts alone are wildly hilarious. Every TV and newspaper report I came across seemed to fit in a quip about it somewhere

I suspect that it doesn’t especially matter that his interests are in music. In fact, the Reform Club’s middle of the road style from what I can make out is pretty inoffensive to anyone. What seemed to provoke the lobby was that he was doing something – anything – that was slightly out of the ordinary.

When that slightly out of the ordinary thing is practicing music skills on a regular basis, you’ve got to wonder how they’d treat any MP who has personal interests that are really unusual.

Several years ago, I spent an enjoyable afternoon at a games club playing a game of Puerto Rico with a Labour MP, at the time a Parliamentary Private Secretary. After the game, we looked over our shoulders to see another group having a raucous game of Cash’n’Guns. He observed “I have to be really cautious about what games I can play in public” at which point I pointed out, to his horror, that he’d just spent the last couple of hours playing a game about the slave trade.

I mention this because he’s right: playing a game in which you wave foam guns in each other’s faces would potentially be career suicide for an aspiring politician, no matter how silly a game it is (which is certainly the case of Cash’n’Guns). But the reason isn’t because doing so would be wrong or wicked in any way, but because it would be seen as weird. And being weird, as Ed Miliband has learned to his cost, is an almost unforgivable crime in modern politics.

The result is, paradoxically, that all our politicians are deeply weird. It’s been almost 40 years since Denis Healey scathingly noted that Margaret Thatcher lacked a hinterland. These days almost none of them have one. William Hague is allowed to write books, albeit on political history. Beer and football are permitted interests, as is primetime television (in moderation). But anything else is treated as shameful and hidden from view, a bit like being gay in the 1950s.

But the weirdest thing about all this is that at the same time, being “wacky” is increasingly the norm for how political journalism is conducted. The model established by Andrew Neil on This Week and the Daily Politics, has now become ubiquitous. Politics is now typically presented on television by people who can’t wait to dress up in silly costumes or wear outrageous hats to make some leaden point or other. Newspaper journalists all seem to consider themselves to be side-splittingly hilarious comedians if my twitter feed is anything to go by. Norman Baker’s crime seems to have been to be sincere in his interests. If he’d done an appallingly awful duet with the chief correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, then it would have been considered perfectly acceptable and not even worthy of mention.

We expect politicians to be “real” and then lay into them when they are. That doesn’t seem terribly healthy to me.

Ethnic Tension And Meaningless Arguments

I.

Part of what bothers me – and apparently several others – about yesterday’s motte-and-bailey discussion is that here’s a fallacy – a pretty successful fallacy – that depends entirely on people not being entirely clear on what they’re arguing about. Somebody says God doesn’t exist. Another person objects that God is just a name for the order and beauty in the universe. Then this somehow helps defend the position that God is a supernatural creator being. How does that even happen?

“Sir, you’ve been accused of murdering your wife. We have three witnesses who said you did it. What do you have to say for yourself?”

“Well, your honor, I think it’s quite clear I didn’t murder the President. For one thing, he’s surrounded by Secret Service agents. For another, check the news. The President’s still alive.”

“Huh. For some reason I vaguely remember thinking you didn’t have a case. Yet now that I hear you talk, everything you say is incredibly persuasive. You’re free to go.”

While motte-and-bailey is less subtle, it seems to require a similar sort of misdirection. I’m not saying it’s impossible. I’m just saying it’s a fact that needs to be explained.

When everything works the way it’s supposed to in philosophy textbooks, arguments are supposed to go one of a couple of ways:

1. Questions of empirical fact, like “Is the Earth getting warmer?” or “Did aliens build the pyramids?”. You debate these by presenting factual evidence, like “An average of global weather station measurements show 2014 is the hottest year on record” or “One of the bricks at Giza says ‘Made In Tau Ceti V’ on the bottom.” Then people try to refute these facts or present facts of their own.

2. Questions of morality, like “Is it wrong to abort children?” or “Should you refrain from downloading music you have not paid for?” You can only debate these well if you’ve already agreed upon a moral framework, like a particular version of natural law or consequentialism. But you can sort of debate them by comparing to examples of agreed-upon moral questions and trying to maintain consistency. For exmaple, “You wouldn’t kill a one day old baby, so how is a nine month old fetus different?” or “You wouldn’t download a car.”

If you are very lucky, your philosophy textbook will also admit the existence of:

3. Questions of policy, like “We should raise the minimum wage” or “We should bomb Foreignistan”. These are combinations of competing factual claims and competing values. For example, the minimum wage might hinge on factual claims like “Raising the minimum wage would increase unemployment” or “It is very difficult to live on the minimum wage nowadays, and many poor families cannot afford food.” But it might also hinge on value claims like “Corporations owe it to their workers to pay a living wage,” or “It is more important that the poorest be protected than that the economy be strong.” Bombing Foreignistan might depend on factual claims like “The Foreignistanis are harboring terrorists”, and on value claims like “The safety of our people is worth the risk of collateral damage.” If you can resolve all of these factual and value claims, you should be able to agree on questions of policy.

None of these seem to allow the sort of vagueness of topic mentioned above.

II.

A question: are you pro-Israel or pro-Palestine? Take a second, actually think about it.

Some people probably answered pro-Israel. Other people probably answered pro-Palestine. Other people probably said they were neutral because it’s a complicated issue with good points on both sides.

Probably very few people answered: Huh? What?

This question doesn’t fall into any of the three Philosophy 101 forms of argument. It’s not a question of fact. It’s not a question of particular moral truths. It’s not even a question of policy. There are closely related policies, like whether Palestine should be granted independence. But if I support a very specific two-state solution where the border is drawn upon the somethingth parallel, does that make me pro-Israel or pro-Palestine? At exactly which parallel of border does the solution under consideration switch from pro-Israeli to pro-Palestinian? Do you think the crowd of people shouting and waving signs saying “SOLIDARITY WITH PALESTINE” have an answer to that question?

But it’s even worse, because this question covers much more than just the borders of an independent Palestinian state. Was Israel justified by responding to Hamas’ rocket fire by bombing Gaza, even with the near-certainty of collateral damage? Was Israel justified in building a wall across the Palestinian territories to protect itself from potential terrorists, even though it severely curtails Palestinian freedom of movement? Do Palestinians have a “right of return” to territories taken in the 1948 war? Who should control the Temple Mount?

These are four very different questions which one would think each deserve independent consideration. But in reality, what percent of the variance in people’s responses do you think is explained by a general “pro-Palestine vs. pro-Israel” factor? 50%? 75%? More?

In a way, when we round people off to the Philosophy 101 kind of arguments, we are failing to respect their self-description. People aren’t out on the streets saying “By my cost-benefit analysis, Israel was in the right to invade Gaza, although it may be in the wrong on many of its other actions.” They’re waving little Israeli flags and holding up signs saying “ISRAEL: OUR STAUNCHEST ALLY”. Maybe we should take them at face value.

This is starting to look related to the original question in (I). Why is it okay to suddenly switch points in the middle of an argument? In the case of Israel and Palestine, it might be because people’s support for any particular Israeli policy is better explained by a General Factor Of Pro-Israeliness than by the policy itself. As long as I’m arguing in favor of Israel in some way, it’s still considered by everyone to be on topic.

III.

Some moral philosophers got fed up with nobody being able to explain what the heck a moral truth was and invented emotivism. Emotivism says there are no moral truths, just expressions of little personal bursts of emotion. When you say “Donating to charity is good,” you don’t mean “Donating to charity increases the sum total of utility in the world,” or “Donating to charity is in keeping with the Platonic moral law” or “Donating to charity was commanded by God” or even “I like donating to charity”. You’re just saying “Yay charity!” and waving a little flag.

Seems a lot like how people handle the Israel question. “I’m pro-Israel” doesn’t necessarily imply that you believe any empirical truths about Israel, or believe any moral principles about Israel, or even support any Israeli policies. It means you’re waving a little flag with a Star of David on it and cheering.

So here is Ethnic Tension: A Game For Two Players.

Pick a vague concept. “Israel” will do nicely for now.

Player 1 tries to associate the concept “Israel” with as much good karma as she possibly can. Concepts get good karma by doing good moral things, by being associated with good people, by being linked to the beloved in-group, and by being oppressed underdogs in bravery debates.

“Israel is the freest and most democratic country in the Middle East. It is one of America’s strongest allies and shares our Judeo-Christian values.

Player 2 tries to associate the concept “Israel” with as much bad karma as she possibly can. Concepts get bad karma by committing atrocities, being associated with bad people, being linked to the hated out-group, and by being oppressive big-shots in bravery debates. Also, she obviously needs to neutralize Player 1’s actions by disproving all of her arguments.

“Israel may have some level of freedom for its most privileged citizens, but what about the millions of people in the Occupied Territories that have no say? Israel is involved in various atrocities and has often killed innocent protesters. They are essentially a neocolonialist state and have allied with other neocolonialist states like South Africa.”

The prize for winning this game is the ability to win the other three types of arguments. If Player 1 wins, the audience ends up with a strongly positive General Factor Of Pro-Israeliness, and vice versa.

Remember, people’s capacity for motivated reasoning is pretty much infinite. Remember, a motivated skeptic asks if the evidence compels them to accept the conclusion; a motivated credulist asks if the evidence allows them to accept the conclusion. Remember, Jonathan Haidt and his team hypnotized people to have strong disgust reactions to the word “often”, and then tried to hold in their laughter when people in the lab came up with convoluted yet plausible-sounding arguments against any policy they proposed that included the word “often” in the description.

I’ve never heard of the experiment being done the opposite way, but it sounds like the sort of thing that might work. Hypnotize someone to have a very positive reaction to the word “often” (for most hilarious results, have it give people an orgasm). “Do you think governments should raise taxes more often?” “Yes. Yes yes YES YES OH GOD YES!”

Once you finish the Ethnic Tension Game, you’re replicating Haidt’s experiment with the word “Israel” instead of the word “often”. Win the game, and any pro-Israel policy you propose will get a burst of positive feelings and tempt people to try to find some explanation, any explanation, that will justify it, whether it’s invading Gaza or building a wall or controlling the Temple Mount.

So this is the fourth type of argument, the kind that doesn’t make it into Philosophy 101 books. The trope namer is Ethnic Tension, but it applies to anything that can be identified as a Vague Concept, or paired opposing Vague Concepts, which you can use emotivist thinking to load with good or bad karma.

IV.

Now motte-and-bailey stands revealed:

Somebody says God doesn’t exist. Another person objects that God is just a name for the order and beauty in the universe. Then this somehow helps defend the position that God is a supernatural creator being. How does that even happen?

The two-step works like this. First, load “religion” up with good karma by pitching it as persuasively as possible. “Religion is just the belief that there’s beauty and order in the universe.”

Wait, I think there’s beauty and order in the universe!

“Then you’re religious too. We’re all religious, in the end, because religion is about the common values of humanity and meaning and compassion sacrifice beauty of a sunrise Gandhi Buddha Sufis St. Francis awe complexity humility wonder Tibet the Golden Rule love.”

Then, once somebody has a strongly positive General Factor Of Religion, it doesn’t really matter whether someone believes in a creator God or not. If they have any predisposition whatsoever to do so, they’ll find a reason to let themselves. If they can’t manage it, they’ll say it’s true “metaphorically” and continue to act upon every corollary of it being true.

(“God is just another name for the beauty and order in the universe. But Israel definitely belongs to the Jews, because the beauty and order of the universe promised it to them.”)

If you’re an atheist, you probably have a lot of important issues on which you want people to consider non-religious answers and policies. And if somebody can maintain good karma around the “religion” concept by believing God is the order and beauty in the universe, then that can still be a victory for religion even if it is done by jettisoning many traditionally “religious” beliefs. In this case, it is useful to think of the “order and beauty” formulation as a “motte” for the “supernatural creator” formulation, since it’s allowing the entire concept to be defended.

But even this is giving people too much credit, because the existence of God is a (sort of) factual question. From yesterday’s post:

Suppose we’re debating feminism, and I defend it by saying it really is important that women are people, and you attack it by saying that it’s not true that all men are terrible. What is the real feminism we should be debating? Why would you even ask that question? What is this, some kind of dumb high school debate club? Who the heck thinks it would be a good idea to say ‘Here’s a vague poorly-defined concept that mind-kills everyone who touches it – quick, should you associate it with positive affect or negative affect?!’

Who the heck thinks that? Everybody, all the time.

Once again, if I can load the concept of “feminism” with good karma by making it so obvious nobody can disagree with it, then I have a massive “home field advantage” when I’m trying to convince anyone of any particular policy that can go under the name “feminism”, even if it’s unrelated to the arguments that gave feminism good karma in the first place.