...Read the rest here

How The “Sin City Shuffle” Works There are two main routes to get from the Vegas airport to the Strip. One of them is illegal. To figure out which one you’re on, apply this test: Look outside. If you can’t find outside, you’re in a tunnel—which means you’re being ripped off.

The I-215 tunnel adds about $10 to your fare, but one in three cabbies “longhauled” undercover cops through it anyway. The country hasn’t seen this kind of brazenness since Bankerty Robberson opened a Skimask Hut outside Wells Fargo in 1979.

What can possibly be done about such a confounding crime? I had plenty of time to research this on a recent trip to Vegas, while my own cabbie, Mickey, drove me to the Bellagio by way of Montpelier, Vermont.

Uber’s absurd answer to longhauling is straight from your childhood: When a driver behaves badly, he only gets one star. Within hours, Uber adjusts your fare. Their systems can do this automatically because they have everything they need to calculate an “ideal” fare—start point, end point, traffic conditions, and past fares. If the driver keeps scamming others, he automatically gets fired.

But Nevada officials found fault in Uber’s stars. In fact, they kicked the company out of town for not protecting tourists.

Shared posts

Uber stars vs. taxi regulators

How a Colombian internet address became the online home for startups

In less than four years, more than 1.6 million individuals and businesses, mostly start-ups, have created a website with an address ending with .co. That is a staggering number for a new top-level domain (the last bit of a web address). Contrast that with .biz, which was introduced in 2000 and by April last year had chalked up just 2.4 million registrations.

People went to .co because, on .com, with over 111 million registrations, the short, simple names are mostly taken. They went also because .co is one letter shorter than .com, which matters in the age of Twitter. But most of all, they went because some very canny marketing convinced them that it’s where sexy, innovative start-ups go.

Of course, .co is not a new top-level domain like the 1,000 or more being introduced this year; it’s the one that was assigned in 1991 to Colombia. Juan Diego Calle, a Colombian-American entrepreneur, won the contract to run it in 2009, after years of effort and a 1,165-page bid. In exchange for exclusive rights to market .co, Calle pays a fee to the Colombian government that goes towards improving the country’s internet infrastructure.

How to market a two-letter product

But Calle then had to convince the world that .co was worth buying. A .com address is recognizable; it has some degree of legitimacy. Newer entrants such as .name, .jobs, and .travel have steadfastly refused to take off. To gain traction, Calle decided to target the ample supply of tech start-ups.

Two factors made .co successful. One was what Calle calls “brand protection.” When new domains launch, professional domain-buyers pick up hundreds of common nouns. Less scrupulous ones also buy trademarked names to try to sell to the trademarks’ owners. Calle wanted big companies to be sure that .co was professionally managed, so he reserved and gave away for free domain names to tech companies and to businesses like American Express. “That generated a lot of goodwill,” says Calle. Big brands have since adopted .co with gusto: Walmart used it for the yet-to-launch goodies.co; Twitter’s makers chose the extension for Vine, the short-video-sharing app.

The second factor was getting the tech industry on board. Calle gave away domains to big firms such as Twitter and Google; they now use t.co and g.co respectively as URL shorteners. AngelList, a website where start-ups meet investors, also picked up a .co domain, giving it legitimacy in the eyes of the start-ups that frequent it. Calle says the fact that .co was a start-up itself lent credence to the notion that it understood other startups. To add to that credence, he started the “.co membership program,” which gives its customers free passes to conferences and connections to other start-ups and investors.

Calle’s success with .co holds a lesson for other companies entering the domain-name business this year. Web addresses ending in everything from .ninja and .guru to .web and .xyz will soon be available. If Calle’s experience is anything to go by, extra services and fancy packaging will be just as important to customers as a snazzy name. These services could include web hosting, email, and help with building webpages, as well as building and nurturing a community of like-minded companies. On its own, a domain name is just an empty piece of land. But build an office block with an efficient mailroom, support staff, and a program of business services, and the value shoots up.

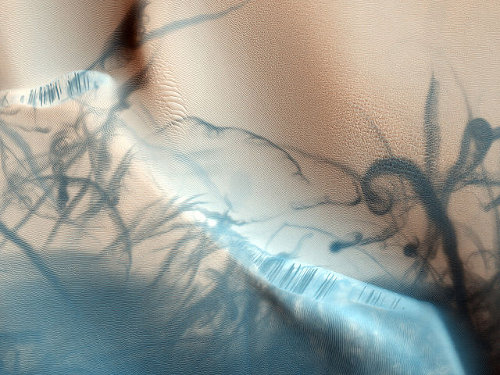

Ghosts of Mars

Dust devils can grow huge on Mars — judging by its shadow, this one was 800 meters tall, about half a mile, and some have reached 10 times that height.

They’re constantly scrawling striking artwork on the Martian surface (below), picking up red dust to reveal the darker sand beneath.

These creatures may be lonely (spooky animation here), but apparently they’re friendly — both the Spirit and Opportunity rovers have had their solar panels cleaned by encounters with wandering devils.

The Speed of Sound

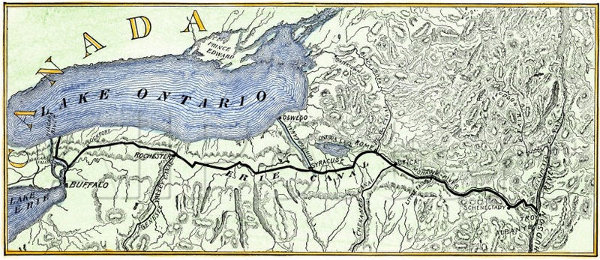

When the Erie Canal was opened on Oct. 26, 1825, the fact was known in New York City, 425 miles away, within 81 minutes. This was before the advent of radio or telegraph. How was it done?

Cannons were placed along the length of the canal and the Hudson River, each within earshot of the last. When the crew of each cannon heard the boom of its upstream neighbor, it fired its own gun.

As a result, New Yorkers knew within an hour and half that they had a navigable route to the Great Lakes — the fastest news dispatch, to that date, in world history.

10/07/2013 Wait, that last bit ain’t right — Claude Chappe’s semaphore telegraph covered 120 miles in 9 minutes in 1792. (Thanks, Michael and Lorcan.)