|

http://proguitarshop.com/free-pedal-friday The Rolling Stones "Satisfaction" guitar lesson. For the next Riff of the Day, we're checking out the Satisfaction...

|

From:

ProGuitarShopDemos

Views:

19606

218

ratings

|

|

| Time: 05:48 | More in Music |

Shared posts

The Rolling Stones - Satisfaction Guitar Lesson

Killer Dana - Surf Guitar Lesson

|

Guitar tutorial on the surf guitar instrumental "Killer Dana" by The Chantays. This lesson covers the intro, riff, verse, break, and chorus.

|

From:

Bruce Lindquist

Views:

2363

49

ratings

|

|

| Time: 09:03 | More in Howto & Style |

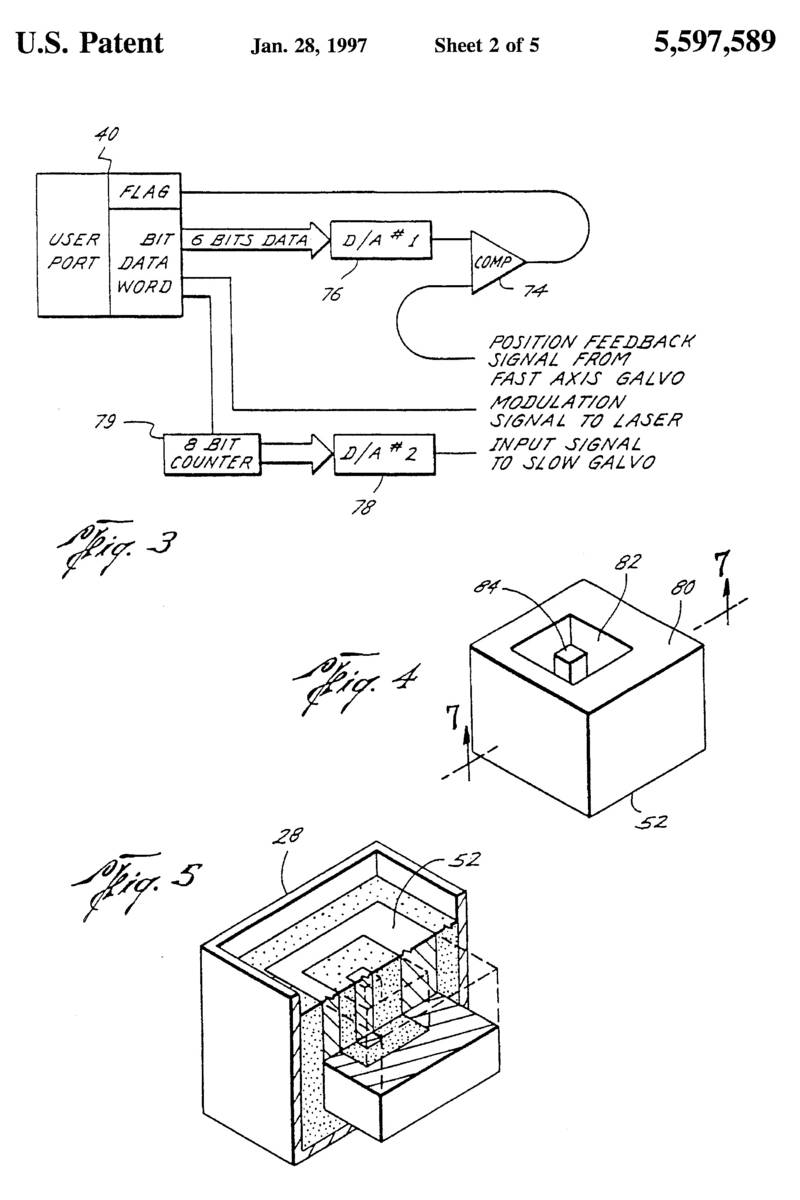

Key 3D printing patent expired yesterday

Yesterday marked the expiry of US Patent 5597589, "Apparatus for producing parts by selective sintering." This is one of the core patents in the 3D printing world -- the patent that allows 3D printer companies to charge more for fine nylon powder than Michelin-starred restaurants charge for filet mignon. The high cost of consumables in 3D printing has been a major barrier to innovation in the field -- selective laser sintering produces a fine finish that the patent-free fused deposition modeling technique used in Reprap-style printers can't match -- and now the brakes are coming off.

However, there are still lots of patents (including some genuinely terrible ones) in the 3D printing world, so the expiry of 5597589 doesn't necessarily mean that we'll see a flood of cheap printers and cheaper feedstock -- given the murkiness of the overlapping patent claims and the expense of litigating each one of them, radical new entrants into the field are still facing a lot of risk that has nothing to do with making great products at a fair price.

In a good piece on 3D Print, Eddie Krassenstein speculates about the scary supplementary laser-sintering patents lurking in the wings, pointing out that Stratasys (the major competitor of 3D Systems, who owned 5597589) didn't design their entry-lever printers to use SLS, even though they knew that the patent would be expiring in early 2014. Krassenstein suggests that this means that Stratasys knows about some other gnarly and deadly patent that would torpedo them if they went SLS.

But I'm a lot less convinced than Krassenstein is about the potential of a competitor taking the risky step of making a SLS printer that sticks to the claims in 5597589. Virtually every technical idea is covered by a stupid, overbroad patent, and yet people start businesses every day that open them to legal liability from a troll or an entrenched incumbent. If the potential for a patent suit was, in itself, a sufficient deterrent to raising capital and starting a business, we wouldn't see any startups. And a company that sticks to the claims in 5597589 has a powerful weapon in any patent suit: the USPTO granted 5597589 20 years ago, and so if they granted overlapping patents since, they were manifestly in error, a matter that is relatively (in patent terms, anyway) easy to prove.

The main thing people expect to happen, with the expiration of this patent, including many experts in the field, is a significant increase in the production of SLS 3D printers, follow by a large decrease in the price. Some are led to believe that Chinese manufacturing firms will quickly be spitting out cheaply made SLS printers at a small fraction of the cost of current printers. However, others argue that there are still too many barriers for entry. The expiring patent is an old one, and while it is probably the most important in selective laser sintering printing, it isn’t the only one. There are literally dozen of other patents that are still valid that center around SLS. This means that any company that wishes to enter into the selective laser sintering market, must make sure that they are not breaking any of the more modern patents. This can be shaky ground, that many entrepreneurs and corporation wish to avoid.

With the possibility of a lawsuit, if a firm believes that their patents have been infringed upon, will certainly scare off a lot of possible competitors. At the same time though, most of the large 3D printing companies have known for years now, that this patent would be coming to an end today. Certainly they have already taken liberty to investigate all of the other laser sintering patents out there, to prepare themselves for the moment this occurred. It is unlikely that many Chinese companies that are used to making cheap merchandise will venture into possible patent wars. However companies like Stratasys, and their subsidiary Makerbot will surely try and find a way around the newer, still active patents.

Laser Sintering 3D Printing May Now Take Off with a Very Important Patent Expiring Today [Eddie Krassenstein/3D Print]

(via O'Reilly Radar) ![]()

The Federal Reserve was created 100 years ago. This is how it happened.

The men who led the newly created Federal Reserve banks. The law that created them passed Congress a century ago, on Dec. 23, 1913. (Photo by Harris & Ewing)

A century ago this week, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, creating a central bank for a nation that was only beginning its economic ascendance. This is the story of how it came to be, from a nearly catastrophic financial panic to secret meetings of plutocrats on the Georgia coast to the pitched battle in the halls of Congress, excerpted from The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire.

The mustachioed man in the silk top hat strode to his private railcar parked at a New Jersey train station, a mahogany-paneled affair with velvet drapes and well-polished brass accents. Five more men — and a legion of porters and servants — soon joined him. They referred to one another by their first names only, an uncommon informality in 1910, intended to give the staff no hints as to who the men actually were, lest rumors make their way to the newspapers and then to the trading floors of New York and London. One of the men, a German immigrant named Paul Warburg, carried a borrowed shotgun in order to look like a duck hunter, despite having never drawn a bead on a waterfowl in his life.

Adapted from “The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire,” by Neil Irwin. Irwin, a Washington Post columnist and economics editor of Wonkblog, was the Post’s beat reporter covering the Federal Reserve and other central banks from 2007 to 2012. The book tells of how the central bankers came to exert vast power over the global economy, from their 17th century beginnings to the present, and tells the inside story of how they wielded that power from 2007 on as they fought a global financial crisis. Excerpted by permission of The Penguin Press, a member of the Penguin Group (USA), © Neil Irwin. Buy it from Amazon here.

Two days later, the car deposited the men at the small Georgia port town of Brunswick, where they boarded a boat for the final leg of their journey. Jekyll Island, their destination, was a private resort owned by the powerful banker J.P. Morgan and some friends, a refuge on the Atlantic where they could get away from the cold New York winter. Their host — the man in the silk top hat — was Nelson Aldrich, one of the most powerful senators of the day, a lawmaker who lorded over the nation’s financial matters.

For nine days, working all day and into the night, the six men debated how to reform the U.S. banking and monetary systems, trying to find a way to make this nation just finding its footing on the global stage less subject to the kinds of financial collapses that had seemingly been conquered in Western Europe. Secrecy was paramount. “Discovery,” wrote one attendee later, “simply must not happen, or else all our time and effort would have been wasted. If it were to be exposed publicly that our particular group had got together and written a banking bill, that bill would have no chance whatever of passage by Congress.”

For decades afterward, the most powerful men in American finance referred to one another as part of the “First Name Club.” Paul, Harry, Frank and the others were part of a small group that, in those nine days, invented the Federal Reserve System. Their task was more than administrative. Because the men at Jekyll Island weren’t just trying to solve an economic problem — they were trying to solve a political problem as old as their republic.

Banking's rough beginning

The U.S. financial system needed remaking. The United States had a long but less than illustrious history with central banking. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary, believed a national bank would stabilize the new government’s shaky credit and support a stronger economy — and was an absolute necessity to exercise the new republic’s constitutional powers.

But Hamilton’s proposal faced opposition, particularly in the agricultural South, where lawmakers believed a central bank would primarily benefit the mercantile North, with its large commercial centers of Boston, New York and Philadelphia. “What was it drove our forefathers to this country?” said James “Left Eye” Jackson, a fiery little congressman from Georgia. “Was it not the ecclesiastical corporations and perpetual monopolies of England and Scotland? Shall we suffer the same evils to exist in this country?” Some founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, believed that the bank was unconstitutional.

By 1811, Madison was in the White House. The Bank of the United States closed down. Until, at least, Madison realized how hard it was to fight the War of 1812 without a national bank to fund the government. The Second Bank of the United States was founded in 1816. It lasted a little longer — until it crashed against the same distrust of centralized financial authority that undermined the first. The populist Andrew Jackson managed its demise in 1836.

Running an economy without a central bank empowered to issue paper money caused more than a few problems in late 19th-century America. For example, the supply of dollars was tied to private banks’ holdings of government bonds. That would have been fine if the need for dollars was fixed over time. But one overarching lesson of financial history is that that’s not the case. In times of financial panic, for example, everybody wants cash at the same time (that’s what happened in fall 2008).

Without a central, government-backed bank able to create money on demand, the American banking system wasn’t able to provide it. The system wasn’t elastic, meaning there was no way for its supply of money to adjust with demand. People would try to withdraw more money from one bank than it had available, the bank would fail, and then people from other banks would withdraw their funds, creating a vicious cycle that would lead to widespread bank failures and the contraction of lending across the economy. The result was economic depression. It happened every few years. One particularly severe panic in 1873 was so bad that until the 1930s, the 1870s were the decade known as the “Great Depression.” There were lesser panics in 1884, 1890 and 1893

Then came the Panic of 1907, the one that finally persuaded American lawmakers to deal with their country’s backward financial system. What made the Panic of 1907 so severe? A bunch of things that happened to converge at once.

It started with a devastating earthquake in San Francisco in 1906. Suddenly, insurers the world over needed access to dollars at the same time. In what was then still an agricultural economy, it was also a bumper year for crops, and an economic boom was under way — so companies nationwide wanted more cash than usual to invest in new ventures. In San Francisco, deposits were unavailable for weeks after the quake: Cash was locked in vaults so hot from fires caused by broken gas lines that it would have burst into flames had they been opened.

All of that meant the demand for dollars was uncommonly high — at a time when the supply of dollars couldn’t increase much. This manifested itself in the form of rising interest rates and withdrawals. Withdrawals begat more withdrawals, and before long, banks around the country were on the brink of failure.

Then in October 1907, the copper miner turned banker F. Augustus Heinze and his stockbroker brother Otto tried to take over the market of his own United Copper company by buying up its shares. When he failed, the price of United Copper stock tumbled. Investors rushed to pull their deposits out of any bank even remotely related to the disgraced F. Augustus Heinze.

First, a Heinze-owned bank in Butte, Mont., failed. Next came the huge Knickerbocker Trust Co. in New York, whose president was a Heinze business associate. Depositors lined up by the hundreds in its ornate Fifth Avenue headquarters, holding satchels in which to stuff their cash. Bank officials standing in the middle of the room and yelling about the bank’s alleged solvency did nothing to dissuade them. The failure of the trust led every bank in the country to hoard its cash, unwilling to lend it even to other banks for fear that the borrower could be the next Knickerbocker.

The power of J.P. Morgan

It is true that the United States, in that fearful fall of 1907, didn’t have a central bank. That doesn’t mean it didn’t have a central banker. John Pierpont Morgan was, at the time, the unquestioned king of Wall Street, the man the other bankers turned to to decide what ought to be done when trouble arose. He was not the wealthiest of the turn-of-the-century business titans, but the bank that bore his name was among the nation’s largest and most important, and his power extended farther than the (vast) number of dollars under his command. His imprint on the financial system has long survived him. Two of the most important financial firms in America today, JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley, trace their lineage to John Pierpont Morgan.

When the 1907 crisis rolled around, Morgan held court at his bank’s offices at 23 Wall St. while a series of bankers came to make their requests for help.

Morgan asked the Treasury secretary to come to New York — note who summoned whom — and ordered a capable young banker named Benjamin Strong to analyze the books of the next big financial institution under attack, the Trust Company of America, to determine whether it was truly broke or merely had a short-term problem of cash flow — the old question of insolvent versus illiquid. Merely illiquid was Morgan’s conclusion. The bankers bailed it out.

It wouldn’t last — with depositors unsure which banks, trusts and brokerages were truly solvent, withdrawals continued apace all over New York and around the country. At 9 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 2, 1907, Morgan gathered 40 or 50 bankers in his library.

The bankers awaited, as Thomas W. Lamont, a Morgan associate, put it, “the momentous decisions of the modern Medici.” In the end, Morgan engineered an arrangement in which the trusts would guarantee the deposits of their weaker members — something they finally agreed to at 4:45 a.m. Medici comparisons aside, it is remarkable how similar Morgan’s role was to that of Timothy Geithner, the New York Fed president, a century later during the 2008 crisis. Both knocked heads to encourage the stronger banks and brokerages to buy up the weaker ones, bailing out some and allowing others to fail, working through the night so action could be taken before financial markets opened.

With a big difference, of course: Geithner was working for an institution that was created by Congress and acted on the authority of the government. His major decisions were approved by the Fed’s board of governors, its members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. His capacity to address the 2007–08 crisis was backed by an ability to create dollars from thin air.

Morgan, by contrast, was simply a powerful man with a reasonably public-spirited approach and an impressive ability to persuade other bankers to do as he wished. The economic future of one of the world’s emerging powers was determined simply by his wealth and temperament.

Time for a change

Enough was enough. The Panic of 1907 sparked one of the worst recessions in U.S. history, as well as similar crises across much of the world. Members of Congress finally saw that having a central bank wasn’t such a bad idea after all. “It is evident,” said Sen. Aldrich, he of the silk top hat and the trip to Jekyll Island, “that while our country has natural advantages greater than those of any other, its normal growth and development have been greatly retarded by this periodical destruction of credit and confidence.”

Legislation Congress enacted immediately after the panic, the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, dealt with some of the financial system’s most pressing needs, but it put off the day of reckoning with the bigger question of what sort of central bank might make sense in a country with a long history of rejecting central banks. It instead created the National Monetary Commission, a group of members of Congress who traveled to the great capitals of Europe to see how their banking systems worked. But the commission was tied in knots.

Agricultural interests were fearful that any new central bank would simply be a tool of Wall Street. They insisted that something be done to make agricultural credit available more consistently, without seasonal swings. The big banks, meanwhile, wanted a lender of last resort to stop crises — but they wanted to be in charge of it themselves, rather than allow politicians to be in charge.

The task for the First Name Club gathered in Jekyll Island in that fall of 1910 was to come up with some sort of approach to balance these concerns while still importing the best features of the European central banks.

Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich, one of the most important shapers of economic policy in early 20th century America. Image by © CORBIS

The solution they dreamed up was to create, instead of a single central bank, a network of them around the country. Those multiple central banks would accept any “real bills” — essentially promises businesses had received from their customers for payment — as collateral in exchange for cash. A bank facing a shortage of dollars during harvest season could go to its regional central bank and offer a loan to a farmer as collateral in exchange for cash. A national board of directors would set the interest rate on those loans, thus exercising some control over how loose or tight credit would be in the nation as a whole.

The men at Jekyll drafted legislation to create this National Reserve Association, which Aldrich, the most influential senator of his day on financial matters, introduced in Congress three months later.

A rocky reception

It landed with a thud. Even though the First Name Club managed to keep its involvement secret for years to come, the idea of a set of powerful new institutions controlled by the banks was a non-starter in this nation with a long distrust of centralized financial authority.

Aldrich’s initial proposal failed, but he had set the terms of the debate. There would be some form of centralized power, but also branches around the country. And what soon became clear was that the basic plan he’d laid out — power simultaneously centralized and distributed across the land and shared among bankers, elected officials, and business and agricultural interests — was the only viable political solution.

Carter Glass, a Virginia newspaper publisher and future Treasury secretary, took the lead on crafting a bill in the House, one that emphasized the power and primacy of the branches away from Washington and New York. He wanted up to 20 reserve banks around the country, each making decisions autonomously, with no centralized board. The country was just too big, with too many diverse economic conditions, to warrant putting a group of appointees in Washington in charge of the whole thing, Glass argued.

President Woodrow Wilson, by contrast, wanted clearer political control and more centralization — he figured the institution would have democratic legitimacy only if political appointees in Washington were put in charge. The Senate, meanwhile, dabbled with approaches that would put the Federal Reserve even more directly under the thumb of political authorities, with the regional banks run by political appointees as well.

But for all the apparent disagreement in 1913, there were some basic things that most lawmakers seemed to agree on: There needed to be a central bank to backstop the banking system. It would consist of decentralized regional banks. And its governance would be shared — among politicians, bankers, and agricultural and commercial interests. The task was to hammer out the details.

Who would govern the reserve banks? A board of directors comprising local bankers, businesspeople chosen by those bankers, and a third group chosen to represent the public. The Board of Governors in Washington would include both the Treasury secretary and Federal Reserve governors appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

How many reserve banks would there be, and where? Eight to 12, the compromise legislation said, not the 20 that Glass had envisioned. An elaborate committee process was designed to determine where those should be located. Some sites were obvious — New York, Chicago. But in the end, many of the decisions came down to politics. Glass was from Virginia, and not so mysteriously, its capital of Richmond — neither one of the country’s largest cities nor one of its biggest banking centers — was chosen.

The vote over the Federal Reserve Act in a Senate committee came down to a single tie-breaking vote, that of James A. Reed, a senator from Missouri. Also not so mysteriously, Missouri became the only state with two Federal Reserve banks, in St. Louis and Kansas City. The locations of Federal Reserve districts have been frozen in place ever since, rather than evolving with the U.S. population — by 2000, the San Francisco district contained 20 percent of the U.S. population, compared with 3 percent for the Minneapolis district.

And in a concession to those leery of creating a central bank, the Federal Reserve System, like the First and Second Banks of the United States, was set to dissolve at a fixed date in the future: 1928. One can easily imagine what might have happened had its charter come up for renewal just a couple of years later, after the Depression had set in.

Creation of a central bank

The debate over the Federal Reserve Act was ugly. In September 1913, Rep. George Ross Smith of Minnesota carried onto the floor of the House a 7-by-4-foot wooden tombstone — a prop meant to “mourn” the deaths of industry, labor, agriculture and commerce that would result from having political appointees in charge of the new national bank.

“The great political power which President Jackson saw in the First and Second National banks of his day was the power of mere pygmies when compared to the gigantic power imposed upon [this] Federal Reserve board and which by the proposed bill is made the prize of each national election,” he argued.

It wasn’t just the fiery populists who opposed the bank. Aldrich, the favored senator of the Wall Street elite, complained that the Wilson administration’s insistence on political control of the institution made the bill “radical and revolutionary and at variance with all the accepted canons of economic law.” He wanted the banks to have more control, not a bunch of politicians.

For all the noise, the juggling of interests was effective enough — and the memory of 1907 powerful enough — for Congress to pass the bill in December 1913. Wilson signed it two days before Christmas, giving the United States, at long last, its central bank. “If, as most experts agree, the new measure will prevent future ‘money panics’ in this country, the new law will prove to be the best Christmas gift in a century,” wrote the Baltimore Sun.

The government, of course, hadn’t solved the problem of panics. It had just gained a better tool with which to deal with them.

And opposition to a central bank, rooted as deeply as it was in the American psyche, didn’t go away. Instead, it evolved. Whenever the economic tide turned — during the Great Depression, during the deep recession of the early 1980s, during the downturn that followed the Panic of 2008 — the frustration of the people was channeled toward the institution they’d granted an uncomfortable degree of power to try to prevent such things.

But after more than a century of trying, the United States had its central bank. Before long, New York would supplant London as the center of the global financial system, and the dollar would replace the pound as the leading currency in the world. And as the years passed, the series of compromises that the First Name Club dreamed up a century earlier, and the unwieldy and complex organization it created, would turn out to have some surprising advantages — even in a country that had previously been better at creating central banks than keeping them.

Adapted from "The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire," published in 2013 by The Penguin Press.

3D Printed Parts That Were “Just What I Needed”

Lachflash

Lachen ist gesund, sagt man. Lachen steckt an, sagt man auch. Lachen kann eine Fernsehshow sprengen, wissen wir hier nach. Ich lache mit.

(Direktlink, via Joanne Casey)

3D Scanning Meets the Museum at the Smithsonian

This week at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. there was a happy merging of hundreds of people in the 3D scanning world and museum world. We gathered to see presentations from so many experts in these fields, including folks from Autodesk, 3D Systems, the Smithsonian and many other museums. We learned about the Wright Flyer, ancient weapons, whale and dolphin fossils, a CT scan of an Embreea orchid and Eulaema bee, and a killer whale hat.

This week at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. there was a happy merging of hundreds of people in the 3D scanning world and museum world. We gathered to see presentations from so many experts in these fields, including folks from Autodesk, 3D Systems, the Smithsonian and many other museums. We learned about the Wright Flyer, ancient weapons, whale and dolphin fossils, a CT scan of an Embreea orchid and Eulaema bee, and a killer whale hat.

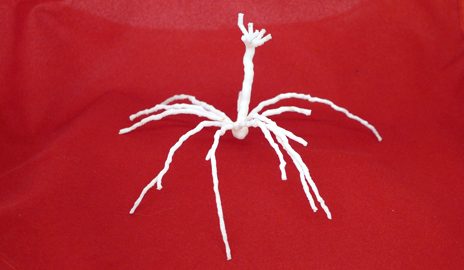

First 3D-printed model of a neuron

Yale neuroscientist Gordon Shepherd has created the first 3D-printed neuron with help from the Yale Center for Engineering Innovation and Design (CEID).

“Brain microcircuits have a very complicated 3D architecture,” said Shepherd, a professor of neurobiology at the Yale School of Medicine and author of The Synaptic Organization of the Brain, a classic in the literature of neurobiology.

“The model will give us unprecedented appreciation of this architecture. It’s like being with someone versus having just a picture.”

“The wild, seemingly haphazard geometry of a neuron, with its cell body, delicate branches of dendrites, and long fibers make it nearly impossible to fabricate by conventional means,” said Joseph Zinter, the CEID’s assistant director. “But 3D printers can easily handle these types of complex geometries. They’re the ideal technology for this kind of project.”

Shepherd’s lab team prepared 3D digital images of a specific mouse neuron. Zinter and designer Yusuf Chauhan then converted the data into a language readable by the CEID’s printers and set them to work.

Within a day Shepherd beheld a hugely magnified but otherwise precise replica of a murine mitral cell, or mouse olfactory neuron. Made of plastic, it measures 4.25 inches high by five inches wide, thousands of times larger than the real thing.

“We’ve been inspecting it from every angle and comparing it with experimental data, ” said Shepherd, who has already presented it to groups of other scientists. “There was a bit of a stunned silence when I pulled the model from its box and held it up for all to see,” Shepherd said of a presentation at Yale. “There definitely seems to be something unexpected about seeing a nerve cell in this new guise for the first time.”

“In addition to being used for the fabrication of models, prototypes, and usable parts, 3D printing allows for the visualization of information in new and exciting ways,” said Zinter. “The ability to interact with information in an additional dimension, whether it’s a microscopic neuron or a patient’s CT scan, will lead to new insights and discoveries. Researchers are still on the cusp of how to best use 3D printing technology.”

Shepherd already has plans for 3D prints of more intricate neural networks. “We see a future in which 3D models of nerve cells will be an integral part of doing research and of teaching neurobiology,” he said.

Saturday Morning Tetratome: New Paintings by Dimitri Drjuchin

“As Getout”

If you are lucky enough to live in Los Angeles—I love saying that—get on down to the Paul Loya Gallery in Culver City tonight for the first Los Angeles solo show of Dimitri Drjuchin’s paintings.

Drjuchin’s career has really taken off in the past few years. He’s the creator of the already iconic cover art for Father John Misty’s Fear Fun album and his “Fuck You, I’m Batman” stickers have the same sort of presence around New York City as Keith Haring’s radioactive baby once had. This will only be the artist’s fourth solo showing.

Here’s a sample of the new show.

“We The Food Chain”

“Be Cool and Everything Will Be Cool”

“No One Noticed the Birth of the Multiverse”

Paul Loya Gallery, 2677 S. La Cienega Blvd. Los Angeles, CA, 90034

Saturday Morning Tetratome runs from November 2 to December 7.

Below, the time-lapse view of “Honeymoon” being painted in 2011:

Reposts - Sept 26, 2013

From top left to bottom right:

Antonio Adolfo e Brazuca (1970)

João Nogueira (1972)

Paulo Moura - Fibra (1971)

Ray Barretto - Indestructable (1973)

Bobby Hutcherson - Now! (1969)

Alaíde Costa - Canta Suavamente (1960)

Some reups for all of you while I am busy with other things. Please report any erroneous links you come across, cheers.

John Kerry Set To Talk With Iran, As Hopes Rise For Obama-Rouhani Handshake

In the highest-level face-to-face between U.S. and Iranian officials since 1979, Kerry and Zarif will meet in New York to talk about Iran's nuclear program, along with representatives from five other countries. For the last several years, under a framework known as P5 Plus One -- for the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany -- the U.S., the U.K., China, Russia, France and Germany have exchanged proposals on this topic with Iran.

Shortly after the White House confirmed the Kerry-Zarif meeting, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki issued a statement reaffirming the United States' readiness "to work with Iran," provided the administration of newly sworn-in Iranian President Hassan Rouhani will "choose to engage seriously."

Rouhani and President Barack Obama are also in New York City this week for the annual high-level meetings of the U.N. General Assembly. But there are currently no plans for the two leaders to meet face to face, said Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes, speaking to reporters Monday aboard Air Force One.

Nonetheless, speculation abounds that Rouhani and Obama might cross paths in the hallways of the U.N. between meetings and speeches, and might even share what would be a historic handshake. On Tuesday, both leaders are expected to attend a luncheon hosted by U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon -- an event that has become a focal point for the diplomatic rumor mill.

Rouhani on Monday tweeted a photo of himself boarding the plane bound for New York. He was ready, he wrote, for "constructive engagement" with the world.

Pres Rouhani leaving for #NYC."Ready for constructive engagement w/ world to show real image of great Iranian nation" pic.twitter.com/7XS91fXHTl

— Hassan Rouhani (@HassanRouhani) September 23, 2013

Trita Parsi, president of the National Iranian American Council, suggested that the breathless anticipation around a possible Obama-Rouhani encounter may have encouraged the State Department to draw attention Monday to Kerry and Zarif's meeting, in order to tamp down expectations over the two presidents.

"It makes sense for the State Department to play up Kerry's role in this week's meetings," Parsi told The Huffington Post on Monday. "If things go wrong tomorrow at the luncheon and there is no handshake, it will still be very important that Kerry and Zarif are having this meeting, at this high level, and people need to be reminded of that," he added. "Still, right now everyone's looking for the Obama-Rouhani moment, and that's understandable."

Since taking office in August, Rouhani has embarked on a charm offensive in the West. In recent interviews with both American and international media, Rouhani, who speaks fluent English, has stressed that Iran is prepared to accept international oversight of its controversial nuclear program.

A former nuclear negotiator himself, viewed by many as a relative moderate, Rouhani told NBC's Ann Curry recently that Iran wants only one thing from P5 Plus One. "That is political resolve. If there is political resolve, the issue can be settled very easily,” he said. “We only want our activities, our nuclear activities, to be peaceful, and we have accepted international supervision over our activities."

Some U.S. officials are skeptical that Iran will come to the table with proposals that would be acceptable to the United States, even as a starting point for further talks.

"Here's the hitch: Iranians are going to want lifting of sanctions right away, which America won't do," said a senior Obama administration official, who requested anonymity to discuss ongoing negotiations. "And the sanction lift isn't going to happen unless Iran agrees to terms that they never would, binding resolutions and so forth."

Part of the risk here for Iran, the official said, is that any legitimate shift in its relationship with the United States would deprive some elements of the Iranian regime of their raison d'etre for the past three decades. "The regime's entire ethos is anti-West. So if they give that up, then what do they stand for?" the official said.

The Rise of Immortal Artists

People ask, what will we do once all the “jobs” are all shipped overseas or made redundant by technology. We. Will. Create.

– Rick Knight

Photo credit: Aurora by Charles Gadeken http://charlesgadeken.com/

We only know of Bach because low bandwidth paper substrates have immortalized him. Below is a digital resurrection and rendition of J.S. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in 1080p. ThePianoguys art experienced here exists in a new substrate of high bandwidth. It is amazing to think that prior to 1860 every musical note played by artists has been lost forever.

“One reason we are richer, healthier, taller, cleverer, longer-lived, and freer than ever before is that the four most basic human needs-food, clothing, fuel, and shelter-have grown markedly cheaper. Take one example: In 1800, a candle providing one hour’s light cost six hours’ work. In the 1880′s, the same light from a kerosene lamp took 15 minutes work to pay for. In 1950, it was eight seconds. Today, it’s half a second. In these terms, we are 43,200 times better off than in 1800.” – Matt Ridley (Rational Optimist)

Think about that – 43,200 times better off than we were in 1800′s. Yet, artists of that age still found the time to create works of art that we can still find wonder and awe in today. We have been afforded the opportunity to all become artists with the abundance of time we have at our disposal. So what’s stopping us?

We have been formed by the “bureaucratic administrative machine”. Public schooling has made us cogs in the British Empire’s military-industrial machine. The Victorians, 300 years ago, constructed an education system to mass-produce identical cogs and gears to keep the machine running. Schools, manufacture generations of workers for the industrial age, not artists. Schools are obsolete, and what they produce for today’s world is obsolete.

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” -Pablo Picasso

The question is often asked to me; “Without jobs, what would people do!? There would be a whole generation of lazy good for nothings”. A life, lived free of obligation leads to creation. Stagnation is a perspective that blinds the imagination. Value, should not be measured from the sweat off of our backs or calluses on our keyed fingers. We are no longer the gears of the system. If there were an accurate measurement for the value of a human life, I would weigh the ‘Condensation of Imagination’. Awareness is the ability to have a mental model of the external world. Imagination is the ability to mold that mental model and render it into reality. Technology has paved a way for us to all become artists. What we chose to create will be the new benchmark of value and worth in the digital age.

“Unbounded by space-time, the new immortal artist will reach out across the ages and beyond the bounds of our known galaxy. This new trans-immortal artist will gaze into the mind of the universal experience and create from a place far beyond the death drive. The canvas will be consciousness and they will paint with stardust.” – Gray Scott

###

Kevin, who also goes by the moniker ‘Techno-Optimist’, is a philosopher, futurist, researcher, lecturer, and the Executive Director of SeriousWonder.com. He enjoys educating and speaking optimistically about the future and technology. Follow him on Twitter @TechnoOptimist