John.boddie

Shared posts

Creativity Training For Creative Creators

John.boddieThe creativity industry is appealing because it offers a royal road to innovation that is divorced from mastery. To the extent that one can "think different" about popular consumer products and design aesthetics, innovation seems friendly and approachable. Much of the common mindset that has emerged in innovation seminars has focused on these sorts of products. My sense is that this is different from the tougher, quieter forms of innovation that require subject mastery. Whether it is controlling lithium hydroxide formation in batteries or writing music in completely new time signatures, this sort of creativity requires time and sacrifice difficult to describe in the context of a TED talk. Both the popularized Ted Talk creativity and the deeper, more fundamental innovation work are useful and the world is a better place with improved design but it would be nice to see more time given to the creativity and innovation that drive fundamental research.

Here's a bilous broadside against the whole "creativity" business - the books, courses, and workshops that will tell you how to unleash the creative powers within your innards and those of your company:

And yet the troubled writer also knew that there had been, over these same years, fantastic growth in our creativity promoting sector. There were TED talks on how to be a creative person. There were “Innovation Jams” at which IBM employees brainstormed collectively over a global hookup, and “Thinking Out of the Box” desktop sculptures for sale at Sam’s Club. There were creativity consultants you could hire, and cities that had spent billions reworking neighborhoods into arts-friendly districts where rule-bending whimsicality was a thing to be celebrated. If you listened to certain people, creativity was the story of our time, from the halls of MIT to the incubators of Silicon Valley.

The literature on the subject was vast. Its authors included management gurus, forever exhorting us to slay the conventional; urban theorists, with their celebrations of zesty togetherness; pop psychologists, giving the world step-by-step instructions on how to unleash the inner Miles Davis. Most prominent, perhaps, were the science writers, with their endless tales of creative success and their dissection of the brains that made it all possible.

I share his skepticism, although the author (Thomas Frank) comes at the whole question from a left-wing political perspective, which is rather far from my own. I think he's correct that many of the books, etc., on this topic have the aim of flattering their readers and reinforcing their own self-images. And I also have grave doubts about the extent to which creativity can be taught or enhanced. There are plenty of things that will squash it, and so avoiding those is a good thing if creativity is actually what you're looking for in the first place. But gain-of-function in this area is hard to achieve: taking a more-or-less normal individual, group, or company and somehow ramping up their creative forces is something that I don't think anyone really knows how to do.

That point I made in passing there is worth coming back to. Not everyone who says that they value rule-breaking disruptive creative types really means it, you know. "Creative" is often used as a feel-good buzzword; the sort of thing that companies know that they're supposed to say that they are and want to be.

"Innovative" works the same way, and there are plenty of others, which can be extracted from any mission statement that you might happen to have lying around. I think those belong in the same category as the prayers of Abner Scofield. He's the coal dealer in Mark Twain's "Letter to the Earth", and is advised by a recording angel that: "Your remaining 401 details count for wind only. We bunch them and use them for head winds in retarding the ships of improper people, but it takes so many of them to make an impression that we cannot allow anything for their use". Just so.

I Like Big Brass and I Cannot Lie: Confessions from the Tuba World: The Life of a Tuba Sister by Elizabeth Eshelman

March 10, 2011—the first day of the regional tuba conference my brother Kent is hosting at Baylor University, where he is the tuba and euphonium professor. When he asked if I’d come from my home in Virginia to help out with the conference, I figured it would be a great opportunity to see Texas for the first time, visit with my parents (incoming from Ohio), and spend hours pondering the gorgeous stained glass panels in Baylor’s Browning Library.

Think again. I spent the first part of the week completing such tasks as comparison shopping for nametags, and then manually retyping the name and university of each of the nearly 300 participants because it turns out that neither a doctor of musical arts (Kent) nor a master of fine arts (me) has the skill-set necessary to get a Microsoft Word list into Avery’s supposedly simple template. Then there was the time I spent a year in Staples choosing the best labeling method for the conference case check service (like coat check at a museum, only for instrument cases). And the raffle for a grand prize of 30 tuba CDs? Well, I was charged with obtaining the roll of tickets, though I wouldn’t be allowed to enter—if I won, it could seem like quite a conflict of interest. I am Kent’s sister, after all.

So now, here I am, ready to start the conference, and even though I had to get up at the butt crack of dawn, I’m excited to work the registration table. Kent is in his office; my dad is copying programs in the department office; and I’m taking one more satisfied look around my set-up in the foyer of the music building when a shadow passes by.

I look up. Above me a bat is turning mad circles, dipping lower than I would like, then flapping up again into the foyer’s heights. I draw my phone from my pocket faster than Walker Texas Ranger could draw a holstered gun. “Dad!” I say when he answers. “Get over here! There’s a bat!”

I expect him to be as shocked and adrenaline-ridden as I am, but I get only his lazy reply that he’s almost done making copies. I demand to know what I should do, but just then, the first three conference attendees arrive.

“There’s a bat,” I tell them helplessly. They all look up, laugh, and immediately begin propping doors with chairs and chatting with me about the likelihood of the bat finding its way out. I am newly grateful that the majority of tuba players, like these three, are male, large-framed, and friendly. By the time my dad saunters in, the bat has indeed found its way out.

It might seem glamorous to be the younger sister of a tuba artist with an international reputation. Kent’s done some pretty impressive stuff, not only winning multiple international competitions (one on jazz tuba!) but so impressing composer Anthony Plog that Plog dedicated his “Nocturne” to Kent, which Kent subsequently premiered in Budapest, Hungary. These days, I can even download Kent’s latest album from Amazon and iTunes.

But as the younger sister, I’ve been behind the scenes enough that I’m more acquainted with the unglamorous underbelly than with tasting the fruits of fame. It’s a little like the time Kent debuted as a tuba soloist in church. He was twelve at the time, and he’d worked up a piece called “Egotistical Elephant.” Since the title wasn’t going to inspire worshipful attitudes, the music director printed it in the bulletin as “Largo.” So while the rest of the congregation reveled in the lovely legato strains of a largo piece, I sat there hearing the swagger of that saucy egotistical elephant.

The bat incident begins to fade as more registrants appear. Most of the attendees are tuba professors and their tuba/euph students from schools like University of Texas, Louisiana State, and many others. There are also guest soloists and the low brass section of the San Antonio Symphony. The college students are the most fun to watch. It’s easy to tell who’s the flirt, who’s the director’s number two, who’s a marching band worshipper, but they all seem to share an ability to move as a group with unwieldy instrument cases, neat as ants transporting giant crumbs. They’re here to play as ensembles and to listen to other college ensembles play, to hear recitals by distinguished tuba and euphonium professors, and to attend master classes and panel discussions on technicalities of playing and career advice.

My attention is drawn back to the registration table by a woman about my age, late 20s with long dark hair and an air of confidence that shows she’s not one of the students. “Lauren Veronie,” she says, and I dutifully produce her nametag. It’s not until later that I discover she’s a professional euphonium player with the United States Army Field Band. I can hardly believe it. I’ve been working on writing my second novel for several months, and my protagonist is a dark-haired, female euphoniumist in her 20s who wins a spot in the U.S. Army Band. Sometimes life imitates art.

The next fire I have to put out comes at the main stage concert that evening, the kickoff event. Kent is slated to play solo tuba for the first half and Lauren Veronie will play solo euphonium in the second half. Kent will be accompanied on the piano by the “other” Dr. Eshelman: In-Ja Song Eshelman, his wife, my sister-in-law. From a certain remove, it’s very sweet and romantic that Kent married his accompanist. But now that they have a two-year-old, it’s more than slightly inconvenient that In-Ja is an incomparably fine pianist. Here’s why:

My parents and I are on our way to take our seats in the auditorium with little Glenn when we accidentally run into Kent and In-Ja. Glenn does not see a professional tubist and pianist about to go on stage; he sees his mother and father who have been so busy preparing for this conference they’ve hardly had time for him. Of course, he’s had 100% of Grandma’s doting attention, but it doesn’t matter. He bursts into a wail the minute they try to separate from us to go backstage.

This is no single wail. This is an all-out meltdown that keeps going even after my dad and I take him first outdoors, then up to Kent’s office, thinking familiar territory might help. I’m still trying to console Glenn when my dad finally tells me he thinks it’s useless; we just have to let him cry until In-Ja can take over again, which means we’ll miss Kent’s big performance of the weekend.

The irony is, there was once a time where I would have leapt at any excuse to get out of a long boring concert. With two older brothers, both of whom are musicians—Jon, the eldest of us three, is an accomplished jazz pianist—I got dragged to so many concerts I could fill a public library with all the novels I read during their performances. I was well versed in the art of seeking out light sources from aisle runners or doors that didn’t quite latch, allowing a tiny sliver of hallway light into the dusky auditorium. But even with my chapter books in hand, I endured interminable waits while judges tallied scores at solo and ensemble contests my brothers had played in. It might sound glamorous to say that I got to hear Kent compete in and win his first international tuba competition, the Leonard Falcone. But the reality was a stuffy room at a summer camp where I listened to each of the tuba finalists play “Sketches.” I don’t mean to dis a perfectly reputable tuba solo, but the truth is, many tuba solos—just like any instrumental recital pieces—aren’t exactly easy listening. The piano accompaniments are complicated, and the solo line moves through swaths of music that lack a readily singable melody. “Sketches” is one of these. Three renditions. Nine movements. Not exactly a thirteen-year-old’s idea of a fun summer afternoon. It was more exciting to see Kent play in the winner’s concert that evening—but what was he asked to play? “Sketches.” At least Kent came away with a first-place medal; all I took home was a bad case of swimmer’s ear from the hotel pool.

But the worst, the absolute worst, thing about getting dragged along to performances as a younger sibling—especially if you’re a younger sibling who can read music—is that when an accompanist needs a page turner, you will be pressed into service faster than a nineteenth-century American sailor at the hands of the British navy.

In many ways, my heart goes out to accompanists. I’ve witnessed In-Ja prepare as much as Kent for certain performances, but he still gets to be the soloist, she the accompanist. But, at least accompanists get some measure of due. Soloists always acknowledge the accompanist during applause, and accompanists’ names are always given in the program.

Page turners, on the other hand, never get recognition. It’s a horribly nerve-wracking job, from the fear of accidentally turning two pages at once to the pressures of waiting for that all-important head nod from the accompanist that means you should turn the page RIGHT THEN. And that’s another thing: accompanists prefer page turners who read music because they assume you can follow along and foresee the page turn. But I’ve had accompanists give that nod a good five measures in advance, and I hesitate thinking, “Really? Are you sure?” and then I second-guess whether it was indeed a cue or just a twitch. Even if you manage to turn one page properly and at the right time, that damn page sometimes starts falling back again because the book is tightly bound. Then you have to decide how best to correct it, and should you really stand through the whole piece hovering clumsily over the music? I’ve also seen accompanists take a good swat at those errant pages. Pity the page-turner whose hand is on its way to fix the page when the accompanist’s swat lands.

In short, when you’re a page turner, the whole performance rests on you, and what do you get in return? The privilege of lingering awkwardly while both the soloist and the accompanist take their bows.

The next day, after watching over the lifeless gig bags and coffin-like hard cases in the case-check room, I see Kent coming down the hall. Now, if I, as a slim young female, am not the stereotypical image of a tuba player, neither is Kent, a beanpole who quite possibly holds the record for the least pounds per inch of professional American tubists.

“Hey,” Kent says. I can tell he’s in a hurry, shuttling between the panels going on here and the solo contests taking place across campus. “You want to introduce Brian Bowman? I need someone to do it for the master class he’s about to teach.”

“Brian Bowman? Me?” And suddenly, being Kent’s sister is all glamour. How else would I ever get to meet and introduce Brian Bowman, a true legend of a euphonium player?! He was the first euphoniumist to play a recital in Carnegie Hall, but that’s not what has my heart a-flutter; to me, he’s the sound on The Sacred Euphonium, a CD of Bowman on solo euphonium accompanied by organ, playing religious pieces of the kind they just don’t make anymore—"I Walked Today Where Jesus Walked," “The Holy City,” classics that have just the right touch of sentimentality to imbue faith with an appealing warmth.

I want to tell Brian Bowman how much that CD means to me, how I was in a Sacred Euphonium phase during my first semester of teaching English composition at a community college, a semester in which, even though I liked the teaching, I struggled with balancing time between teaching obligations and my own writing. Which is to say that when the drudgery of daily-ness seemed more present than any bigger picture dream, I would listen to his music and marvel at its transcendent beauty.

Transcendent beauty—that’s all I want to tell him, but when Kent introduces me, I find that Dr. Bowman is a cordial, mild-mannered man in his sixties to whom I would feel awkward blathering my star-struck praises. I settle for telling him I’m a big fan. “Especially of Sacred Euphonium,” I add, and he replies with modesty typical of many of the low brass world’s fathers, “Oh, yes, the pieces on that one are very nice, aren’t they?”

The next time I see Brian Bowman, he—along with Lauren Veronie and three others—is a panelist on a discussion about careers in military bands. It’s such fortuitous research for my novel, I can’t believe my good luck to be here. They talk about how the military requires a disciplined personality, but that for people who can play by the rules, the military bands offer some of the best music positions possible. The employment is steady, the benefits are great, and performance opportunities are many. Since the bands are filled with top-notch musicians, these panelists report a unique experience of “locking in” musically with their colleagues. And while it’s true that band members, with the exception of those in the premier Coast Guard and Marine bands, are required to go through basic training, the panel makes it sound as if boot camp is just another bonding point and not a deal-breaker.

Then the anecdotes start, stories of playing in the presidential inaugural parades and of how cold it can be when the band does its dry run of the parade route in the wee hours of the morning a week before the actual inauguration. On inauguration day itself, the band’s call time is 5:00 a.m., but often they don’t play their first note until noon after standing in the cold all that time. Brian Bowman talks of playing for ceremonies surrounding the Challenger explosion and for a visit from the queen of England. When Eisenhower died, Bowman received a call at 10:00 p.m., telling him to report at 5:00 a.m.

Lauren Veronie’s stories are different. She’s in the Army Field Band, which is on the road more than 100 days out of the years, and she talks about how she loves the varied places in which they perform. Sometimes small towns in the middle of nowhere are the most rewarding performances because the audience is so appreciative.

Finally, the group talks about what auditions are like, pushing this discussion to the end as if it is a point of unpleasant obligation. I’m sitting at the back of the auditorium, and suddenly I detect the audience’s own “locking in” to what is being said. Where I’ve been gleefully noting down anecdotes, everyone else now becomes diligent note-takers. So here’s the sore point, the stumbling block—and why shouldn’t it be? Auditions come in many forms, according to our panelists, these days most frequently by individual invitation based on a pre-submitted recording, but sometimes by “cattle-call” where anyone can show up on the specified day and play. And though the atmosphere here at the conference is supportive and mutually admiring, here is another repetition of the truth: there are too many players for too few spots.

You can tell this takes a toll even on someone as accomplished as Veronie. “You get to play your instrument for a living,” she says with relief in her voice and a smile on her face.

I think about this when I watch the Baylor Tuba-Euphonium Ensemble perform—five euphoniums, four tubas, all Kent’s students. Very few of the college musicians here today will end up in performance careers. Some will go into music education and become so wrapped up in busy lives, they’ll no longer perform much; others will face heart-rending decisions, like Kent’s student Zach. He will win the student competition at this conference and later a full ride to study tuba at the graduate level, but he’ll pass it up to go to med school. For today, though, these students are on stage playing a wonderful medley entitled “Tuba Sunday,” which starts with “Amazing Grace” and ends with a canonic rendition of “How Firm a Foundation,” the euphoniums echoing the tubas.

Kent is conducting his students. By now I could point out a few by name: Sarah, the unofficial social chair of the studio as evidenced by how the boys gather around this sole woman among them; Angel, the kind euphoniumist who always has a smile and a word of appreciation that my dad and I are helping out so much. Watching them, I realize this is one of the reasons I came to the conference—to see my brother’s students, the people who get to see Kent on a weekly or daily basis, who watch his quirks and habits and have inside jokes with him. It’s a strange kind of jealousy, if jealousy is even the word. It’s more fascination: Who are they? Do they feel the kind of insider ownership of him that I felt towards some of my mentors in college? Do they appreciate him sufficiently?

March 12, 2011. The conference is almost over; the only thing left is the main stage concert that everyone has been looking forward to, the first half to be played by Benjamin Pierce, the second half by none other than Brian Bowman. I’ve heard Ben Pierce’s name many times over the years; I know he’s one of Kent’s favorite low brass buddies from their days as students in the University of Michigan studio.

Before I take my place in the audience, Kent has one more job for me. For a brief shining moment, I get to be the Vanna White of the tuba world and come out on stage bearing the raffle ticket box. Kent says a few words into the microphone, holds the box high, and I draw out the ticket of the lucky winner.

When the excitement dies down again, Kent takes a minute to publicly thank my parents and me for helping with the conference. As I receive my round of applause under the stage lights, I have the distinct sense that people know who I am. Anonymous page-turner no more, I think.

The concert turns out to be well worth the wait. Ben Pierce plays “Wondrous Starry Night,” which he dedicates to his young daughter in the audience. Brian Bowman talks about his personal history with a piece called “Fantasia Originale,” the piece he won his first military band audition with years ago. As he talks and again as he plays, you can hear that this particular music means a great deal to him, that he loves it and owns it and has spent his life as a steward of it. I didn’t have to say anything to him about transcendent beauty, after all. It’s clear he knows.

Since it’s the last night of the conference, Kent is finally free to hang out with his tuba/euph buddies after the concert. He asks if I want to come too, but first we stop to settle a few details in his office. I poke around the CDs that are left from the sale table and exclaim over two Bowman CDs that are new to me.

“Take them,” he says. “I’ll cover it.”

“Are you sure?” I’ve also picked up a Christmas brass CD.

“Yeah. You’ve more than earned them,” he says.

I thank him and remember out loud Christmas of 1994. We laugh. It was back when Kent was a freshman in the high school marching band, whose show that year was music from Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. I never minded being dragged along to marching band shows, entertaining and flashy as they were, and usually my parents would buy me a hot chocolate as I watched from the bleachers on those cool fall evenings, my “I’m a Band Sister” button pinned proudly to my coat. I remember being extra excited that particular Christmas when I had the idea to give Kent the Joseph soundtrack on CD, and I watched eagerly as Kent unwrapped it. I didn’t quite get the reaction I expected; he simply handed me...

Open Letters: An Open Letter to Truckers from Your Adopt-a-Highway Volunteer by Michelle Webster-Hein

Dear truckers,

I found your piss. Twenty-three bottles, to be exact, in the grass along an I-94 entrance ramp. I assume you intended to leave them there. Why else would there be so many? The golden-amber hue of my first find—a gallon jug of Arizona Iced Tea—implied, well, tea, so I picked it up with less care than I otherwise would have shown. The lid, which you failed to secure, fell off, and your stench splashed out onto the grass and splattered across my tennis shoes.

In the heat of the late summer morning, the odor overwhelmed me, and I heaved into the grass. What sort of monster, I thought, would do such a thing? That was before I found the other twenty two bottles. Mountain Dew, Sobe Peach, Propel Berry. Some of you, in a surge of irony, had chosen Aquafina or Ice Mountain with its terrifying, eco-friendly half-cap.

I am not unacquainted with your plight. The peeing into a bottle I understand. My own father drove truck for nearly thirty years, and, informed me, he never pitched his piss tanks out the window but instead threw them into the garbage when he stopped for gas.

Which brings me to the first, most salient question: Why not throw them away? Are you ashamed, in that short walk from cab to can, of how dehydrated you are, your urine’s orange pekoe not remotely identifiable with the Country Time yellow its container suggests? Do you fear that marching your own lonely pee pots to the barrel while your peers are eagerly tossing theirs into ditches will strike them as pretentious? Or do you simply remember only as you wind your wheel onto the ramp that your piss missile is rolling pell-mell over the passenger-side floor, threatening to detonate and sour your air for the next three hundred miles?

And when you finally do crank down the window and make the pitch, do you consider who will find it? There are, as I can figure, only two possibilities: One (less probable), a down-on-his-lucker desperate for refunds; or two, your Adopt-a-Highway volunteer. Because I am the most likely candidate, each find was a slight, a little “screw you, churchie.” But who am I to say? Maybe you chuckled at the thought of my foiled Pollyanna routine, maybe you winced with guilt as you sent your sediment sailing, or maybe you didn’t think of anyone at all.

I try to give you the benefit of the doubt. You may be tired, or you may have felt compelled, by your bottom-line boss or your four hungry children, to start snorting speed. Or you might have developed a meticulously timed dependence on those ubiquitous vials of 5-Hour Energy. Or you might, according to some informal research I’ve recently conducted, simply rely on a combination of sugar and good, old-fashioned caffeine.

The truth is that I have no idea what you’re going through. I’ve never made a cramped bed in the back of a truck cab. I’ve never subsisted on pre-packaged Danishes or hot dogs blistered on a gas station grill. Though my dad drove a truck for a living, I never followed suit, not even for a summer. Nor have I personally ever had to feed a family of five—or even two—with my work alone, and when the wolf did come to the door, it was a cat, who informed me in a bored voice to stop spending so much money on sushi.

People don’t make my profession the butt of jokes. At the somewhat-elite private college I attended, I told my German class what my father did for a living, and they thought I was joking. I burned through ten shades of red as all eyes turned toward me and the laughter skittered to a stop.

I don’t think that’s your fault. It’s certainly not the fault of my father—a smart, talented and poetic man who holds no college degree but who encounters the world with a unique and perceptive eye unrivaled, to my mind, by most of my alma mater’s academicians.

The truth is that, though I am a social climber, I have not exactly pulled myself up by my own bootstraps. Directly after high school, I fell into a significant sum of money as the result of a car accident. One morning, before another long shift at my summer job in a nursing home kitchen, my mother sat me down and informed me that the insurance company was awarding me fifty thousand dollars. I dropped it all on school.

The truth is, had money not fallen from the heavens, I’m not sure I would have had the gall to jump state and strike out on my own. Also true: This serendipity terrifies me. It disrupts the whole narrative. It means that right now I could just as easily be squeaking by on diner tips or a factory salary. Your whizz grenades whisper that fate has hauled me up onto the bank of a swiftly moving river, that those less lucky are driven along by an undercurrent of such desperation that many cannot even take the time to locate a suitable place for their bodily fluids.

So perhaps I have no right to complain. Perhaps collecting portable toilets is my just desserts for veering off our shared path through little verve of my own. Penance for my degrees, my work, my marriage to a white-collar man who has never once felt compelled to relieve himself into a pop bottle in order to better provide for his family. Perhaps your highway ditches are your graveyards, each battered plastic urn a marker of the countless hours you spend alone. Each golden bullet a reminder, as I bend again and again in my awkward dance, that you and I are the same.

Hold up. Yes, we are the same, and correct me if I’m wrong, but I think that means you should be collecting your own sewer ewers and splashing your own pee onto your own tennis shoes and sending your own vomit to comingle with the other liquids your own body has abandoned there.

You’re the volunteer! you might counter, and technically you’re right, I am. But only because some crazy person from our church thought adopting a piece of highway was a great idea, and then fewer people started showing up (surprise, surprise), so I felt obligated to throw my younger spine into the mix. To you, the term volunteer may connote a happy frivolity reminiscent of high school cheerleaders hosing each other at car washes. So stay with that image and then take one cheerleader away from her friends and drop her alone on the side of a highway and toss on sixteen years and a sore back and replace the spray of water with a splash of urine and the laughing with retching, and you’ve pretty much got it. It would be more accurate to consider me not so much a volunteer as a pawn spawned from the soil of your heedless ribaldry.

In short, I’m appealing to your decency.

In short, I encourage you to imagine your own daughter, all grown up, stumbling one day, in a reluctant act of goodwill, across your own bottled remains.

In short, please throw your waste into the garbage, where it belongs.

Respectfully,

Michelle Webster-Hein,

Your Adopt-A-Highway volunteer

18 October (1916): Franz Kafka to Felice Bauer

Franz Kafka originally proposed to Felice Bauer in a letter in 1913—however, they broke it off just weeks afterwards. A few years later, they would become engaged again. This letter is from their second engagement. In the letter below, Kafka sees a mail van set ablaze, and worries that one of Felice’s love letters has perished in the flames. Months later, Kafka would again end their engagement.

Franz Kafka originally proposed to Felice Bauer in a letter in 1913—however, they broke it off just weeks afterwards. A few years later, they would become engaged again. This letter is from their second engagement. In the letter below, Kafka sees a mail van set ablaze, and worries that one of Felice’s love letters has perished in the flames. Months later, Kafka would again end their engagement.

To Felice Bauer:

Prague

October 18th, 1916

Dearest, my poor excess-postage payer, forgive me, but I am almost entirely innocent, of which I could easily convince you with a very detailed description, but from this you will surely excuse me; even Max, the post office official, has so far sent nothing but these postcards. Your Saturday letter arrived today, later in the day Monday’s. The letter was very comforting. Yesterday the mail van carrying the afternoon’s Berlin mail blazed out, and today I went around all morning very pensive and in a haze, continually worrying about the burned-out van in which it is highly probably that your Monday letter with your description of the outing perished in the flames. Only later did your letter arrive; so it wasn’t burned after all.—Max cannot get a permit to go to Munich. During the first part of the evening, which may take place after all, I may be reading some of his poetry. Am not very good, in fact a very bad reader of poetry, but if no one better can be found, I shall be glad to do it. But I must say at once: If you cannot come, I would prefer not to go either. By now I have got used to the idea of seeing you there. No doubt after October 22nd, by which date you chief will have returned from his vacation, you will know for certain whether or not the trip is likely to be possible.

Franz

From Letters to Felice. Edited by Erich Heller and Jürgen Born. Translated by James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth. New York: Schocken Books, 1973. 592 pp.

Shades of Green | Columbia Magazine | Oct. 19, 2013 | 13 Minutes (3,453 words)

"The most dangerous times of any deployment are the first and last thirty days. In the first thirty days, you don’t have the experience to keep you from making stupid mistakes. Add to that the swagger that any young person might have when heading off to war for the first time, and you’ve got a potentially dangerous combination. In short, you’re too stupid to realize that your aggressiveness and confidence is what is most likely to get you killed.

"During the last thirty days, you have the benefit of five to six months of combat experience, but you are tired and have convinced yourself that you have everything under control. You’ve patrolled the same roads and talked to the same people for half a year, and all you can think or talk about is going home. In short, you’ve become too cocky to realize that letting your guard down is what will get you killed. In both cases, it is our hubris that is our most dangerous enemy."

Bear Facts

The Veterinary Record of April 1, 1972, contained a curious article: “Some Observations on the Diseases of Brunus edwardii.” Veterinarian D.K. Blackmore and his colleagues examined 1,598 specimens of this species, which they said is “commonly kept in homes in the United Kingdom and other countries in Europe and North America.”

“Commonly-found syndromes included coagulation and clumping of stuffing, resulting in conditions similar to those described as bumble foot and ventral (rupture in the pig and cow respectively) alopecia, and ocular conditions which varied from mild squint to intermittent nystagmus and luxation of the eyeball. Micropthalmus and macropthalmus were frequently recorded in animals which had received unsuitable ocular prostheses.”

They found that diseases could be either traumatic or emotional. Acute traumatic conditions were characterized by loss of appendages, often the result of disputed ownership, and emotional disturbances seemed to be related to neglect. “Few adults (except perhaps the present authors) have any real affection for the species,” and as children mature, they tend to relegate these animals to an attic or cupboard, “where severe emotional disturbances develop.”

The authors urged their colleagues to take a greater interest in the clinical problems of the species. “It is hoped that this contribution will make the profession aware of its responsibilities, and it is suggested that veterinary students be given appropriate instruction and that postgraduate courses be established without delay.”

Insight

In 1945, Oxford University’s Museum of the History of Science realized that 14 astrolabes were missing from its collection. Curator Robert T. Gunther had arranged for storage of the museum’s objects during the war, but both he and the janitor who had helped him had died in 1940. The missing instruments, the finest of the museum’s ancient and medieval astrolabes, were irreplaceable, the only examples of their kind. Where had Gunther hidden them?

The museum consulted the Oxford city police and Scotland Yard, who searched basements and storerooms throughout the city. The Times, the Daily Mail, and the Thames Gazette publicized the story. Inquiries were extended to local taxi drivers and 108 country houses. At Folly Bridge, Gunther’s house, walls were inspected, flagstones lifted, and wainscoting prised away. A medium and a sensitive were even consulted, to no avail. Finally the detective inspector in charge of the case reviewed the evidence and composed a psychological profile of Gunther, a man he had never met:

Clever professor type, a bit irascible, who didn’t get on too well with his colleagues. Single minded. Lived for the Museum. Hobby in Who’s Who ‘… founding a Museum’. Used to gloat over the exhibits and looked upon them as his own creation. Never allowed anyone else to handle them. Reticent, even secretive. Never told anyone what he what he was going to do. Didn’t trust them, perhaps. Not even his friends the Rumens, who would have offered their car to move the things. Had original ideas though. Safe from blast below street level. Germans would never bomb Oxford. Why, its total war damage was £100 and that from one of our own shells. How right he was. He never expected to die then. Believed he’d live to 90. Hadn’t made any plans; like most of us he thought he might get bumped off when the war started. That’s what he was telling his son in those letters. There was only one conclusion with a man like that anyhow: he’d never let the things out of his reach if he could have helped it. Didn’t even take the trouble to pack his own treasures away in Folly Bridge.

In 1948 the new curator found the missing instruments — they were right “within reach” in the museum’s basement. Gunther had disguised their crate with a label reading “Eighteenth-Century Sundials,” and it had evaded detection throughout the searches.

From A.E. Gunther, Early Science in Oxford, vol. XV, 1967, 303-309.

(Thanks, Diane.)

Roots

In the old times these isles lay there as they do now, with the wild sea round them. The men who had their homes there knew naught of the rest of the world and none knew of them. The storms of years beat on the high white cliffs, and the wild beasts had their lairs in the woods, and the birds built in trees or reeds with no one to fright them. A large part of the land was in woods and swamps. There were no roads, no streets, not a bridge or a house to be seen. The homes of these wild tribes were mere huts with roofs of straw. They hid them in thick woods, and made a ditch round them and a low wall of mud or the trunks of trees. They ate the flesh of their flocks for food, for they did not know how to raise corn or wheat. They knew how to weave the reeds that grew in their swamps, and they could make a coarse kind of cloth, and a rude sort of ware out of the clay of the earth. From their rush work they made boats, and put the skins of beasts on them to make them tight and strong. They had swords made from tin and a red ore. But these swords were of a queer shape and so soft that they could be bent with a hard blow.

– Helen W. Pierson, History of England in Words of One Syllable, 1884

An Alzheimer's Cure? Not So Fast.

The British press (and to a lesser extent, the US one) was full of reports the other day about some startling breakthrough in Alzheimer's research. We could certainly use one, but is this it? What would an Alzheimer's breakthrough look like, anyway?

Given the complexity of the disease, and the difficulty of extrapolating from its putative animal models, I think that the only way you can be sure that there's been a breakthrough in Alzheimer's is when you see things happening in human clinical trials. Until then, things are interesting, or suggestive, or opening up new possibilities, what have you. But in this disease, breakthroughs happen in humans.

This latest news is nowhere close. That's not to say it's not very interesting - it certainly is, and it doesn't deserve the backlash it'll get from the eye-rolling headlines the press wrote for it. The paper that started all this hype looked at mice infected with a prion disease, which led inexorably to neurodegeneration and death. They seem to have significantly slowed that degenerative cascade (details below), and that really is a significant result. The mechanism behind this, the "unfolded protein response" (UPR) could well be general enough to benefit a number of misfolded-protein diseases, which include Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's, among others. (If you don't have access to the paper, this is a good summary).

The UPR, which is a highly conserved pathway, senses an accumulation of misfolded proteins inside the endoplasmic reticulum. If you want to set it off, just expose the cells you're studying to Brefeldin A; that's its mechanism. The UPR has two main components: a shutdown of translation (and thus further protein synthesis), and an increase in chaperones to try to get the folding pathways back on track. (If neither of these do the trick, things will eventually shunt over to apoptosis, so the UPR can be seen as an attempt to avoid having the apoptotic detonator switch set off too often.

Shutting down translation causes cell cycle arrest, as well it might, and there's a lot of evidence that it's mediated by PERK, the Protein kinase RNA-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase. The team that reported this latest result had previously shown that two different genetic manipulations of this pathway could mediate prion disease in what I think is the exact same animal model. If you missed the wild excited headlines when that one came out, well, you're not alone - I don't remember there being any. Is it that when something comes along that involves treatment with a small molecule, it looks more real? We medicinal chemists should take our compliments where we can get them.

That is the difference between that earlier paper and this new one. It uses a small-molecule PERK inhibitor (GSK2606414), whose discovery and SAR is detailed here. And this pharmacological PERK inhibition recapitulated the siRNA and gain-of-function experiments very well. Treated mice did show some behavioralthis really does look quite solid, and establishes the whole PERK end of the UPR as a very interesting field to work in.

The problem is, getting a PERK inhibitor to perform in humans will not be easy. That GSK inhibitor, unfortunately, has side effects that killed it as a development compound. PERK also seems to be a key component of insulin secretion, and in this latest study, the team did indeed see elevated blood glucose and pronounced weight loss, to the point that that treated mice eventually had to be sacrificed. Frustratingly, PERK inhibition might actually be a target to treat insulin resistance in peripheral tissue, so if you could just keep an inhibitor out of the pancreas, you might be in business. Good luck with that. I can't imagine how you'd do it.

But there may well be other targets in the PERK-driven pathways that are better arranged for us, and that, I'd think, is where the research is going to swing next. This is a very interesting field, with a lot of promise. But those headlines! First of all, prion disease is not exactly a solid model for Alzheimer's or Parkinson's. Since this pathway works all the way back at the stage of protein misfolding, it might be just the thing to uncover the similarities in the clinic, but that remains to be proven in human trials. There are a lot of things that could go wrong, many of which we probably don't even realize yet. And as just detailed above, the specific inhibitor being used here is strictly a tool compound all the way - there's no way it can go into humans, as some of the news stories got around to mentioning in later paragraphs. Figuring out something that can is going to take significant amount of effort, and many years of work. Headlines may be in short supply along the way.

Frozen Chicken Train Wreck

Rachael Allen, Laurence Hamburger

Frozen Chicken Train Wreck is a book of reproduced tabloid posters from daily newspapers – The Star, Daily Sun, The Times and others – that have been displayed on roadsides in South Africa since the First Anglo-Boer War. Laurence Hamburger has been collecting them since 2008, and a selection of these make up the book recently published by Chopped Liver Press and Ditto Press. Here, he answers questions for Rachael Allen about the concept of the book, why he started collecting the posters and offending everyone.

RA: Could you tell me a little about why you decided to start collecting the posters?

LH: I think it’s very important from the outset to state that I’m not the first person to collect posters of this kind in Johannesburg. There are a couple of famous bars, like The Radium, who have some on their walls, some from as far back as the emergency years, and many others – journalists, artists and students – that I know have a few choice ones hanging in their homes. They have become kitsch, part of a certain South African pop culture. All I’ve done is collate a series of them and show something of the experience of reading them in sequence. I began to see that there was a kind of pattern that could at some stage be curated in an interesting way. I first used the collection when I filmed a series of them in an animation in six locations around Johannesburg. I was, at this point, creating live visual backdrops for a band, the BLK JKS, and I suggested using the posters as a piece for a part of the performance. That was with Mpumi Mcata from the band, and Liam Lynch, a photographer. Initially Chopped Liver Press and I discussed the book as a series of these stills, but Liam wasn’t interested in that as a project and so through discussions with Chopped Liver the book, as it exists now, evolved. I’m very happy with this choice to ‘recreate’ the posters. I think it was the best decision in terms of reflecting their design qualities, and letting the reader experience them in a fairly pure way. They feel the most archival, but ironically the most alive.

But to be less obscure, my reasoning for collecting was that I felt they made an appropriate narrative of a kind of South African vox populi.

Vince Pienaar, Copy Editor at the Daily Sun said that the posters were ‘the perfect marriage of a corrupt society and a progressive constitution’. What were you hoping to show in gathering them all together – and at what point did you realize their relevance as a marker for a historical context?

I’d returned to South Africa during the FIFA World Cup in 2010 to research another book on township pop records and had collected the odd poster over the years, and it was during that period that I began to think of putting them together. It wasn’t just the individual posters but the sequencing that became the trigger. Read in groups, they really seemed a different way to reflect the ‘temperature’ of the place, which I was maybe noticing more acutely then, having been away for the best of part of a decade. I think it was a simple revelation, a result of feeling a little like a tourist in my home town for a while. It was only when I finally came to look through them, and there were about fifty, that I saw how much had actually ‘happened’ in South Africa. There was such a vast variety of political drama and social transformation that it was like a film script in the making. I’m a filmmaker and I suppose I just saw stories, and the new stories created from throwing groups of stories together. Also, as a student in the early nineties I had a conversation with my late friend Paul Botha (now the subject of the novel False River), about one poster hanging in a friend’s kitchen. He was a very sharp guy – a poet – and I clearly remember him explaining the word-craft required to do this kind of thing and how at its best, it reflected the unique quality of South African speech that was often absent in South African English literature. I suppose they were part of a broader process of turning me on to what was uniquely South African. We are still a very young culture and we have suffered from great insecurities as to what we are and how we have been formed. These posters are a kind of reassurance that we are no longer a mere colonial afterthought or, worse, a form of the USA with the sound turned down.

There is so much that happens in a week in South African society. It is a pretty rich source of ‘content’ journalistically speaking, more so than, let’s say, Sweden, where the society has been stabilized over the centuries and is now capably managed. This place is still in upheaval and has experienced such radical social trauma – one example being the number of rape crimes committed daily – and that the news in many ways is almost unbelievable and unbearable. Increasing amounts of this daily trauma was reflected in the posters.

I could see a change from the content a decade ago – they had become more relevant to the ordinary person and their experiences here.

Also, most people I know collected the posters that had their names on them – Clinton, George, Jacob – so were personally relevant, or because of a great political pun (‘the NP [National Party] loses its Virginia’), but I began to collect posters with the larger picture in mind. So posters like ‘Missing Baby: Woman Held’, which might not be so amazing in the hipster bedroom, were very good for my purposes, because it could function as part of a grander narrative.

Which poster is your favourite?

It’s always changing. We’ve been thinking of what to do with them now, and so the topic always comes up. This week I like ‘Tree Kills Tree Expert’ for its sheer surreal, droll humour. I just love the whole idea of a tree having a personality. ‘World Loses Hop[e]’, only because you know someone had that one banked waiting for Bob Hope to die. Many of these would hang in my film offices for weeks until we replaced them, some of the more popular ones were: ‘No More Mrs Nice Guy’, and ‘Karate Goat Hates Me’, which is as surreal as a newspaper headline could get, I reckon. I do love ‘All Blacks Are Brilliant’, which was the working title of the book. It has the potential to offend everyone.

Is there a poster that you drove past and never stopped to pick up but wish you did?

When I initially started I thought I would complete this project in a week or a month at best. I expected to find all of the posters in the newspaper archives and the printers. Both sources had nothing. I was quite shocked and that’s when the project became a matter of action, and a matter of having to stop and collect. So often I have missed ‘classics’ because we had to go to a meeting, or were chasing light on a shoot. Sometimes I would try to remember where they were and attempt to go back and collect. Often it was too late and they had been changed or someone else had taken it. Maybe I’m so crushed by missing some that I cauterize myself and forget what they’ve said, because right now I can’t think of a single one. There was one recently, about a dancing gay pastor that I can never remember the exact phrasing for, but I remember being disappointed I didn’t get it.

‘The ones that never got published’ is the real list I’d love to make. One of the copy editors told of how they were stopped from using ‘Oscar Will Walk’ after it looked like the detective had blown the Pistorious case in the first few days of the trial.

All images courtesy of of Laurence Hamburger

For exclusive content from Granta 125: After the War, read Paul Auster’s ‘You Remember the Planes’, Lindsey Hilsum on her return to Rwanda, Michael W. Clune on playing Beyond Castle Wolfenstein, and a Q&A with Romesh Gunesekera.

Voices from the Government Shutdown: April Tabor and Yaa Apori by Sean Carman

April Tabor and Yaa Apori are attorneys with the Federal Trade Commission. They spoke on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol on October 4, 2013.

APRIL TABOR: I work in the Office of the Secretary for the Federal Trade Commission, so I actually work directly for the Secretary of the FTC. I essentially advise on policy. I also help to make sure the decisions of the Commission are actually implemented. But I’m here today as a private citizen. Anything I say is in my personal opinion, and not necessarily representative of FTC’s views.

YAA APORI: My name is Yaa Apori. I’m an attorney in the Division of Financial Practices of the FTC. I work on mortgage relief, debt relief, credit card scams—basically putting a stop to fraudulent business practices related to financial services. Like April, I can’t speak on behalf of the FTC. I can only speak in my capacity as a citizen.

TABOR: The FTC’s mission is to protect America’s consumers. We have over 900 employees working all over the country. We’re a small agency but we’re a very mighty one. Just in this year alone we’ve given back hundreds of millions of dollars to consumers as a result of our prosecution actions. So we deliver a lot of bang for our buck.

During times of economic uncertainty, the typical scams that we normally prosecute and stop—those fraudulent scams and operations skyrocket. Right now the entire FTC is furloughed, except for the commissioners and a select group of people. So we know that what’s happening now, during the shutdown, is that consumers are being harmed on a daily basis and there’s really nothing that can be done about it. We’re not able to help the public by receiving their complaints, registering their complaints, or prosecuting their complaints.

TABOR: We came down to Capitol Hill today to visit our congressmen. We visited fifteen different congressmen to let them know the impact the shutdown is having on federal government employees and the corresponding impact it is having on consumers. We know that it’s easy to ignore phone and email. But it’s not easy to ignore someone who is right in front of you, looking at you and expressing their concerns.

We visited the offices of the Speaker of the House, the Majority Whip, and the leaders of the Budget, Appropriations, and Ways and Means committees. We spoke to their different chiefs of staff to let them know our concerns, and that we want the government to be re-opened. We also told them that discussions to re-open the government and raise the debt ceiling should not be tied to political gamesmanship at the expense of the American people. We told them we expect them, as leaders, to rise above the political blaming, to be the bigger people, to come forward, and focus on the people who are being affected by the shutdown on a daily basis.

But it’s not just about our agency. It’s about the entire federal government. I think people don’t understand the overall impact that a federal government shutdown has on their day-to-day lives. Although, now I think people are starting to get an understanding of it.

The other concern we expressed to the representatives, is that the piecemeal bills to fund the re-opening of the national parks, the National Institutes of Health, the Veterans Administration—that passing those piecemeal bills is not a solution. It would be a band-aid that would make the American people feel the problem had been resolved without really resolving anything. We said, “We understand the House passed many of those measures, but we are opposed to that. We want a solution. We don’t want to revisit this again and again and again. It’s not fair to the American people.”

I think our visits expanded their perspective, and that we made the problem harder to ignore. I think it’s harder to politicize the shutdown when you have a person telling you, “I have this many days until my mortgage payment or I risk a default.”

And I have to say, we were very well received. They listened, they were respectful. They spoke to us and addressed our concerns.

So I would suggest that every federal employee in DC do this. For most of us, the congressional offices are just a couple extra Metro stops. I mean, you were going to commute to your job today. Go the couple extra stops. Visit a member of Congress. Visit as many of them as you can. Let your voice be heard.

APORI: And it’s not just something we think; it’s something they said. They said they were happy to see people who came in. They encouraged us.

In terms of who we’re seeing next, I grew up in Texas . . .

TABOR: So, Senator Cruz, baby! That’s after lunch. (laughter).

APORI: Yeah. We’re going back. Just engaging with someone. We’re staff, so we can understand how relaying a comment, an opinion, a concern, will get back to the people who matter most. We’re here, we might as well do it.

15 October (1958): Ernest Hemingway to Archibald MacLeish

In the spring of 1958, The Paris Review ran an interview with Hemingway in which he discussed writing and regaled George Plimpton with stories of the Paris expat scene of the 1920’s. Hemingway’s longtime friend and poet, Archibald Macleish was upset by the interview; not only was Macleish apparently misquoted in the piece, but he was conspicuously absent from Hemingway’s reminiscences (they had traveled all over Europe together in the 1920’s). Here, Hemingway writes to account for the omissions.

In the spring of 1958, The Paris Review ran an interview with Hemingway in which he discussed writing and regaled George Plimpton with stories of the Paris expat scene of the 1920’s. Hemingway’s longtime friend and poet, Archibald Macleish was upset by the interview; not only was Macleish apparently misquoted in the piece, but he was conspicuously absent from Hemingway’s reminiscences (they had traveled all over Europe together in the 1920’s). Here, Hemingway writes to account for the omissions.

Note: Hemingway had a reputation as a wretched stenographer—it is something he almost prided himself on. His errors have been preserved in the text below.

[Ketchum, Idaho October 15 1958]

Dear Archie:

I was awfully glad to get your letter out here but sorry there was something loused up in the [Paris Review] interview. All I could do was try to answer the questions as they were put. Am sure you told it straight and that they got it wrong. Everybody gets everything wrong.

About knowing writers it was older writers they meant and I never thought of you as an older writer. Also think they were asking about when we first hit Paris in the old Rue de Cardinal Lemoine-Place Contrescarpe days. Maybe I knew you then but I dont think it was until we had gone back to Canada and then come back to live at 113 rue Notre Dame des Champs. I remember very clearly comeing to the Rue du Bac the first time and stealing a cork screw which I remember returning. Anyway George [Plimpton] was asking about the first days in Paris and that was what I was talking about and writing about at the time. When we used to go around together was afterwards when I not see very much of G. Stein any more and Ezra went to Rapallo and Joyce had finished Ulysses and the fun time between that and going to work on the blind stuff. You correct me if I am wrong because I can remember most things word for word that were important but other times I would forget automatically.

You dope. Did you think I had forgotten Rue de Bac, juan les Pins, Zaragoza, Chartres, that place of Peter Hamiltons you lived, our bicycles, Ada and the Six Jours [bike races], rue Froidevaux, and a million things Gstaad,—don’t ask me to name them all, Bassano and A Pursuit Race. How many better stories has she published than that turn down—they all write about those people and about the junk show.

But Archie I am a slow writer about the past and I cant put you in before I knew you but I was very fond of you and am and I loved Ada and I do.

Poor Sara and Gerald—let’s not write about it. I loved Sara and I never could stand Gerald but I did…

Best love always,

Pappy.

From Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters, 1917-1961. Edited by Carlos Baker. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981. 948 pp.

FURTHER READING

Read the full interview here in the Paris Review.

For a condensed biography of Archibald MacLeish (and a few neat excerpts from his canon), see his page on Poetry Foundation.

Hans Riegel, Marketer of Gummi Bears, Dies at 90

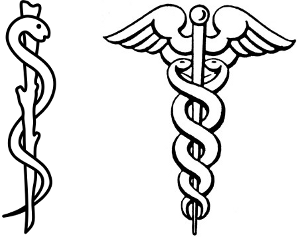

Stick Fight

The Rod of Asclepius, left, with a single snake, is the symbol of medicine. Unfortunately, a large number of commercial American medical organizations instead use the caduceus, right, which has two snakes. Asclepius was the Greek god of healing, but the caduceus was wielded by Hermes and connotes commerce, negotiation, and trickery.

The confusion began when the American military began using the caduceus in the late 19th century, and it persists today. In a survey of 242 healthcare logos (reported in his 1992 book The Golden Wand of Medicine), Walter Friedlander found that 62 percent of professional associations used the rod of Asclepius, while 76 percent of commercial organizations used the caduceus.

“If it’s got wings on it, it’s not really the symbol of medicine,” the communications director of the Minnesota Medical Association told author Robert Taylor. “Some may find it hard to believe, but it’s true. It’s something like using the logo for the National Rifle Association when referring to the Audubon Society.”

An Interview Between the Authors of the Toro Bravo Cookbook by McSweeney's Books

There’s an episode of Portlandia in which Carrie’s on the phone, trying frantically to square away a babysitter for Fred. It’s important: she has a business dinner at Toro Bravo, which—if you’re a Portland denizen—you know is no joke. Any meal at Toro Bravo, the Spanish-inspired, family-style restaurant in the city’s northeast, is a singular, special thing. It’s food that’s generous and from scratch—cooked with a lot of attention and even more heart.

Which is why we’re so very excited to be publishing the Toro Bravo cookbook, co-written by chef John Gorham (who helms not just Toro, but two other popular Portland joints, Tasty n Alder and Tasty n Sons, too) and local food writer Liz Crain. (It’s available now.)

This book IS Toro Bravo: beloved recipes, behind-the-scenes stories, step-by-step guides on how to butcher chickens and MacGyver fridges. I feel extremely lucky to have been the book’s editor—to have gotten to know John and Liz, and eaten unladylike amounts of chorizo in the process. These two were endlessly fun to work with, and unequivocally game whenever I made any of my many, many demands. Book printed, job finished, I made them do this one last thing: pick each other’s brains about their favorite books and what it was like to write this thing. Here’s what happened.

—Rachel Khong

LIZ: What do you think makes a good cookbook?

JOHN: It’s pretty basic—a book that inspires me to cook. Generally, I don’t cook exact recipes that much. When you came today, I was making those elBulli olives from a recipe, but I think food has a soul of its own. You have to put your own soul into it. If there’s science involved in a recipe, I’ll definitely follow the science, but I’ll play around with techniques and ingredients to make it my own. I’m looking more for inspiration than exact measurements. Any cookbook that makes me think, I want to go cook that right away—those are the best cookbooks. How about yourself?

LIZ: I really like narrative cookbooks—good stories. I love Sandor Katz’s books for that reason. He digs really deeply into his life and how he came into fermentation. Joe Beef, Mission Street Food, Au Pied de Cochon, which you introduced me to. I like all of those cookbooks for the stories. They’re just as useful to me as the recipes— lot of times more useful.

JOHN: I’ve never been inspired to make anything from Au Pied de Cochon—it makes my gallbladder hurt just looking at it—but it’s fun to read, and I can see the love that they have, and how much they’re into it. I feel the same way about Mission Street Food. Man, no way am I going to ever grind burgers the way they do. I actually believe fully in emulsifying the meat a bit, anyway. But again, you see their excitement and it gives you that urge to go out and cook something of your own. Both of those books really do that.

LIZ: What are some of your favorite cookbooks?

JOHN: One of my all-time favorites is Fernand Point’s Ma Gastronomie. There aren’t any recipes—just some ingredients and a little talk of technique, and that’s it. You have to figure it out yourself. It’s a really inspiring and uplifting book, written by a guy who loved food. I love Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen. I read the introduction to that book probably once a year. The recipes in that book are phenomenal. Everything comes out amazing, even though it’ll kill you. I love the River Café books from London. And of course the first Chez Panisse book. Paul Bertolli wrote that one, and it’s always been an inspiration. I’ve always looked up to him. When he wrote a blurb for our book, that was so exciting for me. What are some of your favorites?

LIZ: The Vij’s cookbook—not the cooking at home one, the elegant and inspired one—is my favorite Indian cookbook. Everything that I’ve ever cooked out of that has been perfect. All of Sandor Ellix Katz’s. I use Wild Fermentation all of the time. It’s really inspiring to me for fruit wines, cider, and miso. I love Nigel Slater’s writing. Tender goes through all of the seasons of he and his partner breaking ground in their London plot. I love all of the Alice Waters’s books as well. James Beard’s books. I love his seafood one.

LIZ: What is your favorite part of our book?

JOHN: Honestly, it’s the Acknowledgments, when we get to thank everyone. It was really fun to get to thank everyone who’s been a big part of this. How about yourself, what’s yours?

LIZ: Probably the timeline: that behind-the-scenes look at what made you a chef and what fueled Toro and continues to fuel Toro. It’s crazy to see all of your different travels and read about the twenty-one different schools that you went to before you graduated from high school. Talking through all of that during those long lunches for the book was really special for me.

JOHN: What did you find to be the most challenging thing about writing the cookbook?

LIZ: The recipes. All the narrative parts were really fun to write; I loved going to all of those long lunches with you and listening to you talk about your past and about Toro. Once we got to the recipes, though, everything was much more technical. Coming up with the right language and making the recipes accessible to the home cook took a lot of time and patience. They were tricky. What about you, what did you find the most difficult part to be putting the book together?

JOHN: Time management. Testing those recipes took so much time. When we first decided to do the cookbook I was really cocky and thought, Oh man, recipes? No problem. We are so locked and loaded with recipes. We have recipe books for everything that we do. Consistency is one of the pinnacles of what I believe in. But when we pulled those recipes out, I quickly realized that there was so little technique and so few steps written out in them. I just expect my cooks to know both. I give them the recipes with seven items and the amounts and they already know what to do. So our recipes weren’t nearly as locked and loaded as I thought.

LIZ: And there are so many things that are specific to Toro that we had to figure out how to get across to the home cook. Your curing room is perfect for your pickling and fermenting so we had to figure out what would work for the home cook.

JOHN: Exactly—it’s all so particular. When I open a new restaurant I know the food doesn’t yet have what it’s going to have in six months. It’s going to taste different. The temperature and how you use your room all contribute to the flavors of your food. For a while, we served the Toro burger at Tasty n Sons. People would come to me and say, It’s just not the same. And I would say, Man, we are making the bacon, making the romesco, same buns, same equipment… But I would go over there and would have it and totally get what they were saying. It’s what’s in the air, too. Seventy-five percent of your taste is through your nose, so if the room doesn’t smell the same, the food is going to taste a little different.

LIZ: If your Granddad Gordon was alive and he could come to the book launch party what do you think that he would do at it?

JOHN: He would be at the front door with a martini or a glass of champagne in his hand greeting everyone and pointing me out: Here’s my grandson. He would definitely be there front and center, making sure that he said hello to every person.

LIZ: What would he be wearing?

JOHN: Oh, a tux. Without a doubt. For something like that, he’d pull a tux out. I wish I could dress the way he dressed. I wish I had the finesse and time to pull that off. I always said that when I turned forty I’d wear a suit every day and I didn’t. But I don’t. I’m too much of a comfort fiend. That was his thing. He always dressed to the nines.

LIZ: Do you think he’d like the music?

JOHN: No.

(Laughter)

JOHN: He also lost his hearing in one ear in World War II and probably wouldn’t even notice.

Sitting Protest

German shipyard worker August Landmesser openly loved a Jewish woman under the gathering cloud of Nazism in the 1930s. He had joined the party hoping it would help him to find a job, but was expelled when he became engaged to Irma Eckler in 1935. Unwilling to renounce their love, the two were forbidden to marry, prevented from fleeing to Denmark in 1937, and eventually sent to concentration camps.

The photograph above was taken at the launch of the naval training vessel Horst Wessel on June 13, 1936, a year after their engagement. The man in the center, the only one not giving the Nazi salute, is believed to be Landmesser.

Self-Destroying Art

Jean Tinguely presented Homage to New York in the sculpture garden at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960. New York governor Nelson Rockefeller and three television crews watched as the machine played a piano, produced an abstract painting, and inflated a weather balloon, then set itself afire. Tinguely summoned a firefighter to extinguish the blaze and then finished the destruction with an ax.

He followed this up with Study for the End of the World No. 2, a sculpture assembled from odds and ends collected from Las Vegas scrapyards and blown up in the Nevada desert to invoke the testing of atomic bombs:

As a comment on the ephemeral nature of text, in 1992 William Gibson wrote a 300-line poem titled Agrippa (a book of the dead) and published it on a 3.5″ floppy disk in a book of art by abstract painter Dennis Ashbaugh. The disk was programmed to encrypt itself after a single use, and the book’s pages were chemically treated to fade on exposure to light. Ironically, the text was pirated at its first performance and is now extensively archived at the UCSB English department.

Art Appreciation

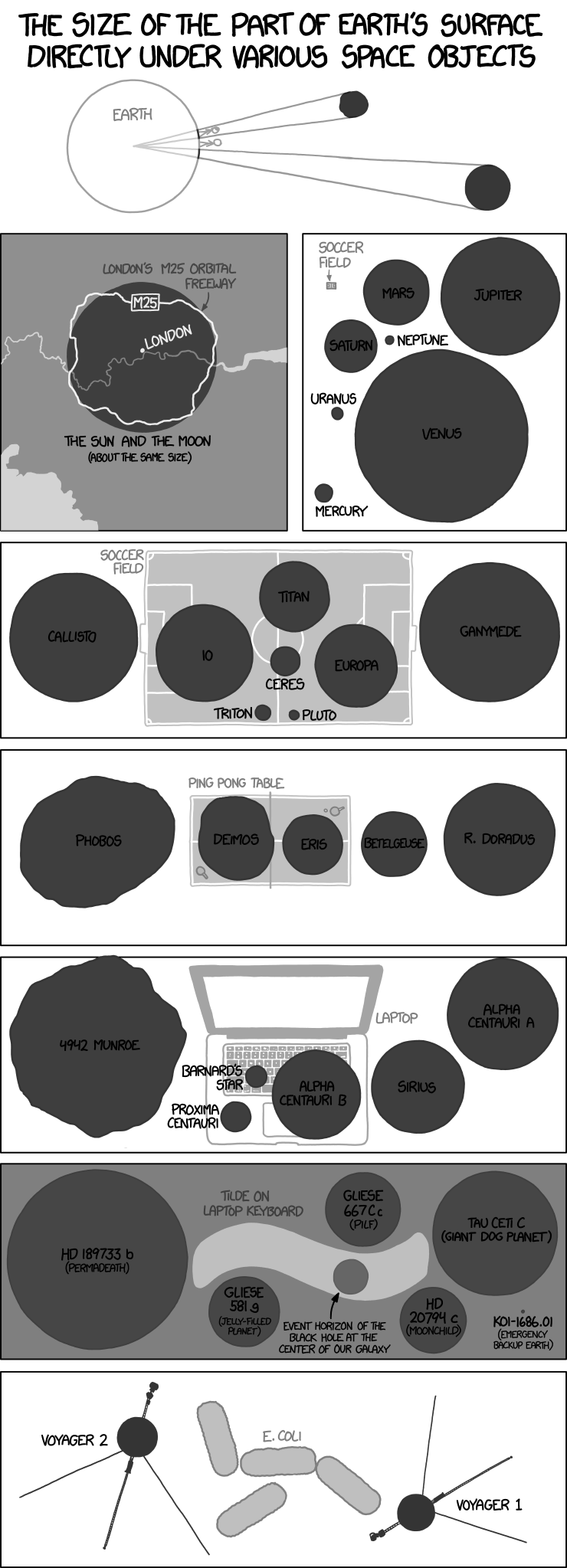

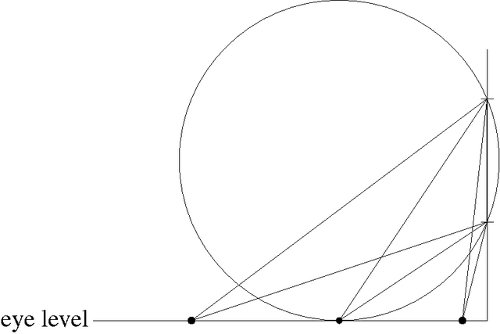

If we stand immediately below a painting in a gallery, it appears foreshortened. But if we stand on the other side of the room, it appears small. Somewhere between these two points must be the optimum viewing position, where the painting fills the widest possible angle in our vision. How can we find it?

The German mathematician Regiomontanus posed this question in 1471. We can solve it using calculus, but it also yields to simple geometry: Draw a circle defined by the top and bottom of the painting and our eye level. Because inscribed angles on the same arc of a chord are equal, the angle subtended by the painting will be constant when viewed from any point on this circle; since the only available such point is the one at eye level, that’s the one we want.

The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has gone to Martin Karplus of Harvard, Michael Levitt of Stanford, and Arieh Warshel of USC. This year's prize is one of those that covers a field by recognizing some of its most prominent developers, and this one (for computational methods) has been anticipated for some time. It's good to see it come along, though, since Karplus is now 83, and his name has been on the "Could easily win a Nobel" lists for some years now. (Anyone who's interpreted an NMR spectrum of an organic molecule will know him for a contribution that he's not even cited for by the Nobel committee, the relationship between coupling constants and dihedral angles).

Here's the Nobel Foundation's information on this year's subject matter, and it's a good overview, as usual. This one has to cover a lot of ground, though, because the topic is a large one. The writeup emphasizes (properly) the split between classical and quantum-mechanical approaches to chemical modeling. The former is easier to accomplish (relatively!), but the latter is much more relevant (crucial, in fact) as you get down towards the scale of individual atoms and bonds. Computationally, though, it's a beast. This year's laureates pioneered some very useful techniques to try to have it both ways.

This started to come together in the 1970s, and the methods used were products of necessity. The computing power available wouldn't let you just brute-force your way past many problems, so a lot of work had to go into figuring out where best to deploy the resources you had. What approximations could you get away with? How did you use your quantum-mechanical calculations to give you classical potentials to work with? Where should be boundaries between the two be drawn? Even with today's greater computational power these are still key questions, because molecular dynamics calculations can still eat up all the processor time you can throw at them.

That's especially true when you apply these methods to biomolecules like proteins and DNA, and one thing you'll notice about all three of the prize winners is that they went after these problems very early. That took a lot of nerve, given the resources available, but that's what distinguishes really first-rate scientists: they go after hard, important problems, and if the tools to tackle such things don't exist, they invent them. How hard these problems are can be seen by what we can (and still can't) do by computational simulations here in 2013. How does a protein fold, and how does it end up in the shape it has? What parts of it move around, and by how much? What forces drive the countless interactions between proteins and ligands, other proteins, DNA and RNA molecules, and all the rest? What can we simulate, and what can we predict?

I've said some critical things about molecular modeling over the years, but those have mostly been directed at people who oversell it or don't understand its limitations. People like Karplus, Levitt, and Warshel, though, know those limitations in great detail, and they've devoted their careers to pushing them back, year after year. Congratulations to them all!

More coverage: Curious Wavefunction and C&E News. The popular press coverage of this award will surely be even worse than usual, because not many people charged with writing the headlines are going to understand what it's about.

Addendum: for almost every Nobel awarded in the sciences, there are people that miss out due to the "three laureate" rule. This year, I'd say that it was Norman Allinger, whose work bears very much on the subject of this year's prize. Another prominent computational chemist whose name comes up in Nobel discussions is Ken Houk, whose work is directed more towards mechanisms of organic reactions, and who might well be recognized the next time computational chemistry comes around in Sweden.

Second addendum: for a very dissenting view of my "Kumbaya" take on today's news, see this comment, and scroll down for reactions to it. I think its take is worth splitting out into a post of its own shortly!

The Nyctograph

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Lewis Carroll was a poor sleeper and did a lot of thinking in bed. The notes he made in the dark often turned out to be illegible the next day, but he didn’t want to go to the trouble of lighting a lamp in order to scribble a few lines.

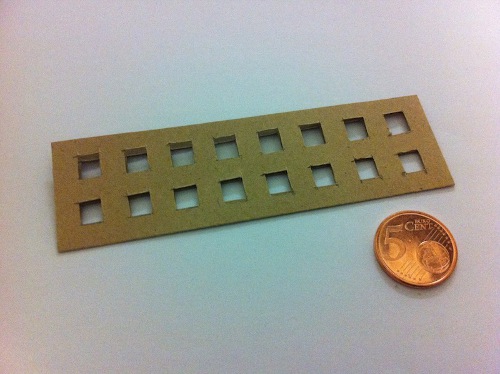

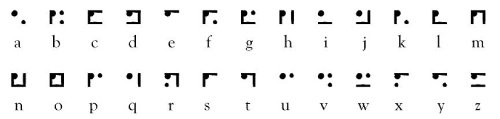

So in 1891 he invented the nyctograph, a card containing a grid of cells that could guide his writing in the dark, using a peculiar alphabet he invented for the purpose:

“I tried rows of square holes,” he wrote, “each to hold one letter (quarter of an inch square I found a very convenient size), but the letters were still apt to be illegible. Then I said to myself, ‘Why not invent a square alphabet, using only dots at the corners, and lines along the sides?’ I soon found that, to make the writing easy to read, it was necessary to know where each square began. This I secured by the rule that every square-letter should contain a large black dot in the N.W. corner. … [I] succeeded in getting 23 of [the square letters] to have a distinct resemblance to the letters they were to represent.”

“All I have now to do, if I wake and think of something I wish to record, is to draw from under the pillow a small memorandum book containing my Nyctograph, write a few lines, or even a few pages, without even putting the hands outside the bed-clothes, replace the book, and go to sleep again. Think of the number of lonely hours a blind man often spends doing nothing, when he would gladly record his thoughts, and you will realise what a blessing you can confer on him by giving him a small ‘indelible’ memorandum-book, with a piece of paste-board containing rows of square holes, and teaching him the square-alphabet.”

Quick Thinking

During one of the many nineteenth-century riots in Paris the commander of an army detachment received orders to clear a city square by firing at the canaille (rabble). He commanded his soldiers to take up firing positions, their rifles leveled at the crowd, and as a ghastly silence descended he drew his sword and shouted at the top of his lungs: ‘Mesdames, m’sieurs, I have orders to fire at the canaille. But as I see a great number of honest, respectable citizens before me, I request that they leave so that I can safely shoot the canaille.’ The square was empty in a few minutes.

– American psychiatrist Paul Watzlawick, Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution, 1974

Brecht Dossier:

On Painting and the Painter

from The Book of Twists and Turns