The Awful Records founder gives a Breaking Bad-meets-Young Frankenstein treatment to the EP’s lead single.

One of the most significant, but least covered, parts of the war on terror has been the Treasury Department's effort to shut down al-Qaeda and other jihadist groups' access to financial institutions. It's an attractive way of tackling the problem: Freezing accounts here isn't as expensive as sending in troops or airstrikes, and no civilians get hurt.

Except the second part might not be true. A report released last week by the Center for Global Development, authored by a working group chaired by visiting fellow Clay Lowery and senior fellow Vijaya Ramachandran, argues that laws meant to counteract money laundering and terrorism financing are encouraging broader "derisking," in which Western banks cut off ties with financial institutions in the developing world so as to reduce the odds that they'll run afoul of regulations. The result is that developing-world banks, money transfer organizations (which handle remittances), and nonprofit organizations are losing access to the financial system as a whole.

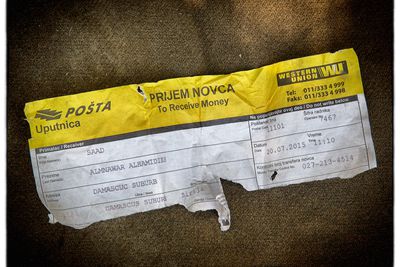

That can have real human consequences. People in countries like Somalia or Nigeria who rely on remittances from relatives in rich countries like the US could see fewer transfers or higher fees. NGOs doing health programs or cash transfers could see programs scaled back due to lack of banking. Foreign investment in developing countries could decrease due to fewer big international banks dealing in those countries.

These concerns aren't just hypothetical. A 2013 survey by CGAP (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor) found that 70 percent of remittance-handling companies in Australia either had accounts closed or had been threatened with closure. Barclay's is estimated to have closed accounts for more than 140 British remittance companies. Remittances alone totaled nearly $600 billion last year, more than double all official foreign aid, and bank moves like these seriously jeopardize those flows. And that's not even considering the effects on developing country banks and NGOs. "Even the large NGOs trying to do cash programs are having trouble getting a bank account," Ramachandran told me.

The US federal government has been fighting money laundering for decades, dating back at least to the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970. And since 1990, rich nations have coordinated their policy response to the problem through a group called the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). FATF has generally advocated a "risk-based approach" to money laundering enforcement. With customers and activities unlikely to be engaged in laundering, authorities can use less invasive, simpler enforcement methods. But for customers and activities judged at high risk, enforcement gets more resource-intensive and intricate.

This works pretty well for ordinary money laundering, since you can identify low-risk customers just by seeing who doesn't have very much money in the bank. A checking account with $17 in it doesn't really need to be closely analyzed for laundering behavior. But it's much trickier when you're trying to combat terrorism financing. Even though some suspected terrorism financiers will be on sanctions lists, there's doubtless some financing happening through individuals and organizations that aren't on law enforcement or intelligence agencies' radars. That means financial regulators have to look at the whole pool. And they can't necessarily rule out accounts or transactions involving small amounts: As the CGD report quotes FATF advising, "Transactions associated with the financing of terrorists may be conducted in very small amounts, which in applying a risk-based approach could be the very transactions that are frequently considered to be of minimal risk with regard to money laundering."

What's more, after 9/11, enforcement by US authorities ramped up, with the total number of fines issued spiking:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4274867/enforcement_rampup_chart.jpg) CGD

CGD

And the total value of fines has grown in recent years from trivial levels into the billions:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4274881/valuefines.jpg) CGD

CGD

The financial sector responded to this uptick in enforcement by "withdrawing wholesale from types of activities or business sectors that are seen to be riskier," Lowery and Ramachandran write.

This process is known as "derisking," and it's had a serious impact on the developing world, especially in countries judged to be high risk for terrorism financing. Numerous companies are pulling out of the remittance business, which puts people receiving remittances in poor countries at risk of serious financial hardship. International banks are showing wariness of dealing with banks in "high-risk countries," which could hurt investment and endanger the livelihoods of people there. And, perhaps predictably, nonprofits judged to be overly "Islamic" are getting targeted, regardless of the humanitarian work they do.

Here are just a few of the indicators Lowery and Ramachandran compiled showing developed country banks curbing their relationships with remittance companies, developing country banks, and NGOs working in the developing world:

And following the CGD report, the undersecretary of the treasury for international affairs, Nathan Sheets, reported results from a World Bank survey of financial institutions suggesting that this derisking process was making it meaningfully more expensive to do business in the developing world. "Three-quarters of the large banks indicated that they had reduced the number of their correspondent accounts in recent years," Sheets said in a speech at CGD. "On the respondent side, a majority of local and regional banks reported a decline in the number of their correspondent accounts, with [remittance businesses] and small clients particularly affected. The vast majority of affected banks reported that they were able to find replacements, though often at a higher cost."

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4278619/460205920.jpg) Win McNamee/Getty Images

Win McNamee/Getty Images

The solution here, Ramachandran told me, will likely take the form of better, subtler enforcement rather than huge changes in the legal framework. "The big picture is that these rules have to be implemented better, in a smarter way than what's happening now," she says. "What we're arguing is that we need better implementation of the risk-based approach. They should be able to address risk on a case-by-case basis rather labeling entire entities as high risk."

Case-by-case enforcement means that innocent people in "high-risk" countries like Somalia will take less of a hit, but it could also mean that the counterterrorism goals of the enforcement regime are easier to meet. The fewer transparent mechanisms for transferring money to poor countries, like remittance services, there are, the more people start to turn to less traceable methods, like just transferring cash in suitcases (as reportedly has been happening in Somalia). "What we're seeing is that money is beginning to flow through less transparent mechanisms," Ramachandran says. "This is not what we want, from either a development perspective or a security perspective."

Luckily, key stakeholders are recognizing that this is a concern. The fact that a senior Treasury official like Sheets appeared at the CGD event unveiling the new report, and provided data confirming the scale of the problem, was itself a significant good omen. FATF, the international anti–money laundering coordinating body, has warned financial institutions against wholesale derisking. "The FATF Recommendations only require financial institutions to terminate customer relationships, on a case-by-case basis, where the money laundering and terrorist financing risks cannot be mitigated," the group said in a statement. "What is not in line with the FATF standards is the wholesale cutting loose of entire classes of customer."

A significant faction in Congress has also begun to champion the issue and pressure US authorities for better enforcement. In February, three senators and nine members of the House wrote to Secretary of State John Kerry, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, Fed Chair Janet Yellen, and other major executive branch policymakers warning of decreasing remittance options for Somali Americans, saying a solution is required to "protect our national security and avoid exacerbating a humanitarian crisis." Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN) — whose state has a significant Somali refugee population — brought up the issue during Yellen's February testimony before the House Financial Services Committee, and Yellen conceded derisking was "causing a great deal of hardship."

The problem is hardly solved — but unlike plenty of other policy areas, there at least seems to be some interest in Washington in addressing it.