Map-Reduce is a universal incremental evaluation strategy, which can schedule and execute any pure function of the individual inputs, provided you reduce the result in an algebraically closed fashion. So that exists. Any others?

Well, many sequential/batch processes are universally incrementalizable too. Take for example a lexer, which processes a stream of text and produces tokens. In this case, the input cannot be chunked, it must be traversed start-to-end.

The lexer tracks its syntax in an internal state machine, while consuming one or more characters to produce zero or more tokens.

Conveniently, the lexer tells you everything you need to know through its behavior in consuming and producing. Roughly speaking, as long as you remember the tuple (lexer state, input position, output position) at every step, you can resume lexing at any point, reusing partial output for partially unchanged input. You can also know when to stop re-lexing, namely when the inputs match again and the internal state does too, because the lexer has no other dependencies.

Lining up the two is left as an exercise for the reader, but there's a whole thesis if you like. With some minor separation of concerns, the same lexer can be used in batch or incremental mode. They also talk about Self-Versioned Documents and manage to apply the same trick to incremental parse trees, where the dependency inference is a bit trickier, but fundamentally still the same principle.

What's cool here is that while a lexer is still a pure function in terms of its state and its input, there crucially is inversion of control: it decides to call getNextCharacter() and emitToken(...) itself, whenever it wants, and the incremental mechanism is subservient to it on the small scale. Which is another clue, imo. It seems that pure functional programming is in fact neither necessary nor sufficient for successful incrementalism. That's just a very convenient straightjacket in which it's hard to hurt yourself. Rather you need the application of consistent evaluation strategies. Blind incrementalization is exceedingly difficult, because you don't know anything actionable about what a piece of code does with its data a priori, especially when you're trying to remain ignorant of its specific ruleset and state.

As an aside, the resumable-sequential approach also works for map-reduce, where instead of chunking your inputs, you reduce them in-order, but keep track of reduction state at every index. It only makes sense if your reducer is likely to reconverge on the same result despite changes though. It also works for resumable flatmapping of a list (that is, .map(...).flatten()), where you write out a new contiguous array on every change, but copy over any unchanged sections from the last one.

Each is a good example of how you can separate logistics from policy, by reducing the scope and/or providing inversion of control. The effect is not unlike building a personal assistant for your code, who can take notes and fix stuff while you go about your business.

Don't Blink

This has all been about caching, and yet we haven't actually seen a true cache invalidation problem. You see, a cache invalidation problem is when you have a problem knowing when to invalidate a cache. In all the above, this is not a problem. With a pure function, you simply compare the inputs, which are literal values or immutable pointers. The program running the lexer also knows exactly which part of the output is in question, it's everything after the edit, same for the flatmap. There was never a time when a cache became invalid without us having everything right there to trivially verify and refresh it with.

No, these are cache conservation problems. We were actually trying to reduce unnecessary misses in an environment where the baseline default is an easily achievable zero false hits. We tinkered with that at our own expense, hoping to squeeze out some performance.

There is one bit of major handwavium in there: a != b in the real world. When a and b are composite and enormous, i.e. mutable like your mom, or for extra points, async, making that determination gets somewhat trickier. Async means a gap of a client/server nature and you know what that means.

Implied in the statement (a, b) => 🦆 is the fact that you have an a and a b in your hands and we're having duck tonight. If instead you have the name of a store where you can buy some a, or the promise of b to come, then now your computation is bringing a busload of extra deltas to dinner, and btw they'll be late. If a and b have large dependent computations hanging off them, it's your job to take this additional cloud of uncertainty and somehow divine it into a precise, granular determination of what to keep and what to toss out, now, not later.

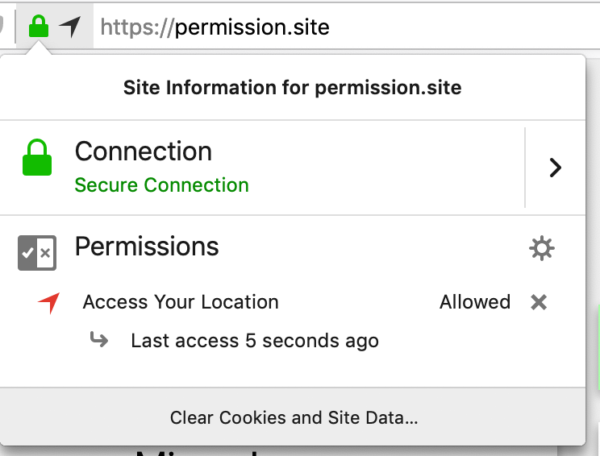

1) You don't have an image, you have the URL of an image, and now you need to decide whether the URL will resolve to the same binary blob that's in your local cache. Do they still represent the same piece of data? The cache invalidation problem is that you weren't notified when the source of truth changed. Instead you have to make the call based on the metadata you originally got with the data and hope for the best.

Obviously it's not possible for every browser to maintain long-lived subscriptions to every meme and tiddy it downloaded. But we can brainstorm. The problem is that you took a question that has a mutable answer but you asked it to be immutable. The right answer is "here's the local cache and some refreshments while you wait, ... ah, there's a newer version, here". Protocol. Maybe a short-lived subscription inside the program itself, from the part that wants to show things, subscribing to the part that knows what's in them, until the latter is 100% sure. You just have to make sure the part that wants to show things is re-entrant.

2) You want to turn your scene graph into a flattened list of drawing commands, but the scene graph is fighting back. The matrices are cursed, they change when you blink, like the statues from Doctor Who. Because you don't want to remove the curse, you ask everyone to write IS DIRTY in chalk on the side of any box they touch, and you clean the marks back off 60 times per second when you iterate over the entire tree and put everything in order.

I joke, but what's actually going on here is subtle enough to be worth teasing apart. The reason you use dirty flags on mutable scene graphs has nothing to do with not knowing when the data changes. You know exactly when the data changes, it's when you set the dirty flag to true. So what gives?

The reason is that when children depend on their parents, changes cascade down. If you react to a change on a node by immediately updating all its children, this means that further updates of those children will trigger redundant refreshes. It's better to wait and gather all the changes, and then apply and refresh from the top down. Mutable or immutable matrix actually has nothing to do with it, it's just that in the latter case, the dirty flag is implicit on the matrix itself, and likely on each scene node too.

Push vs pull is also not really a useful distinction, because in order to cleanly pull from the outputs of a partially dirty graph, you have to cascade towards the inputs, and then return (i.e. push) the results back towards the end. The main question is whether you have the necessary information to avoid redundant recomputation in either direction and can manage to hold onto it for the duration.

The dirty flag is really a deferred and debounced line of code. It is read and cleared at the same time in the same way every frame, within the parent/child context of the node that it is set on. It's not data, it's a covert pre-agreed channel for a static continuation. That is to say, you are signaling the janitor who comes by 60 times a second to please clean up after you.

What's interesting about this is that there is nothing particularly unique about scene graphs here. Trees are ubiquitous, as are parent/child dependencies in both directions (inheritance and aggregation). If we reimagine this into its most generic form, then it might be a tree on which dependent changes can be applied in deferred/transactional form, whose derived triggers are re-ordered by dependency, and which are deduplicated or merged to eliminate any redundant refreshes before calling them.

In Case It Wasn't Obvious

So yes, exactly like the way the React runtime can gather multiple setState() calls and re-render affected subtrees. And exactly like how you can pass a reducer function instead of a new state value to it, i.e. a deferred update to be executed at a more opportune and coordinated time.

In fact, remember how in order to properly cache things you have to keep a copy of the old input around, so you can compare it to the new? That's what props and state are, they are the a and the b of a React component.

Δcomponent = Δ(props * state)

= Δprops * state + Δstate * props + Δprops * Δstate

= Props changed, state the same (parent changed)

+ State changed, props the same (self/child changed)

+ Props and state both changed (parent's props/state change

triggered a child's props/state change)

The third term is rare though, and the React team has been trying to deprecate it for years now.

I prefer to call Components a re-entrant function call in an incremental deferred data flow. I'm going to recap React 101 quickly, because there is a thing that hooks do that needs to be pointed out.

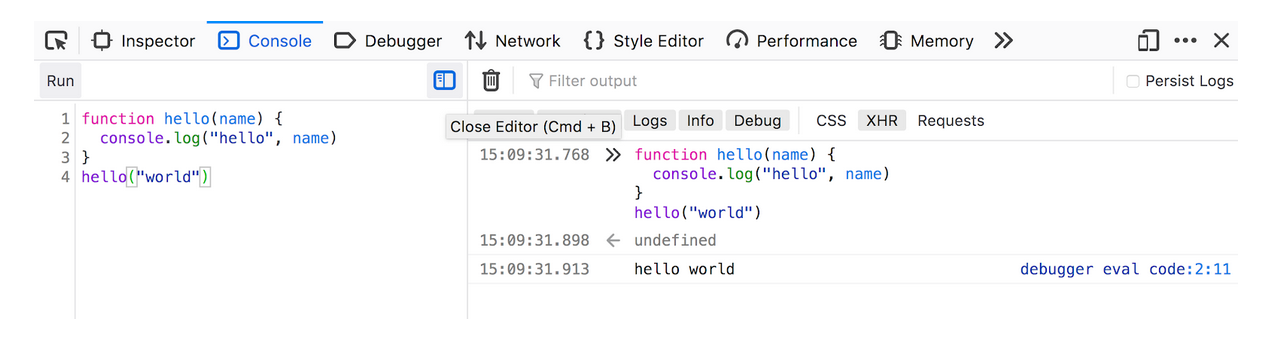

The way you use React nowadays is, you render some component to some native context like an HTML document:

ReactDOM.render(<Component />, context);

The <Component /> in question is just syntactic sugar for a regular function:

let Component = (props) => {

// Allocate some state and a setter for it

let [state, setState] = useState(initialValue);

// Render a child component

return <OtherComponent foo={props.bar} onChange={e => setState(...)}/>;

// aka

return React.createElement(OtherComponent, {foo: props.bar, onChange: e => setState(...)}, null);

};

This function gets called because we passed a <Component /> to React.render(). That's the inversion of control again. In good components, props and state will both be some immutable data. props is feedforward from parents, state is feedback from ourselves and our children, i.e. respectively the exterior input and the interior state.

If we call setState(...), we cause the Component() function to be run again with the same exterior input as before, but with the new interior state available.

The effect of returning <OtherComponent .. /> is to schedule a deferred call to OtherComponent(...). It will get called shortly after. It too can have the same pattern of allocating state and triggering self-refreshes. It can also trigger a refresh of its parent, through the onChange handler we gave it. As the HTML-like syntax suggests, you can also nest these <Elements>, passing a tree of deferred children to a child. Eventually this process stops when components have all been called and expanded into native elements like <div /> instead of React elements.

Either way, we know that OtherComponent(...) will not get called unless we have had a chance to respond to changes first. However if the changes don't concern us, we don't need to be rerun, because the exact same rendered output would be generated, as none of our props or state changed.

This incidentally also provides the answer to the question you may not have realized you had: if everything is eventually a function of some Ur-input at the very start, why would anything ever need to be resumed from the middle? Answer: because some of your components want to semi-declaratively self-modify. The outside world shouldn't care. If we do look inside, you are sometimes treated to topping-from-the-bottom, as a render function is passed down to other components, subverting the inversion of control ad-hoc by extending it inward.

So what is it, exactly, that useState() does then that makes these side-effectful functions work? Well it's a just-in-time allocation of persistent storage for a temporary stack frame. That's a mouthful. What I mean is, forget React.

Think of Component as just a function in an execution flow, whose arguments are placed on the stack when called. This stack frame is temporary, created on a call and destroyed as soon as you return. However, this particular invocation of Component is not equally ephemeral, because it represents a specific component that was mounted by React in a particular place in the tree. It has a persistent lifetime for as long as its parent decides to render/call it.

So useState lets it anonymously allocate some permanent memory, keyed off its completely ephemeral, unnamed, unreified execution context. This only works because React is always the one who calls these magic reentrant functions. As long as this is true, multiple re-runs of the same code will retain the same local state in each stack frame, provided the code paths did not diverge. If they did, it's just as if you ran those parts from scratch.

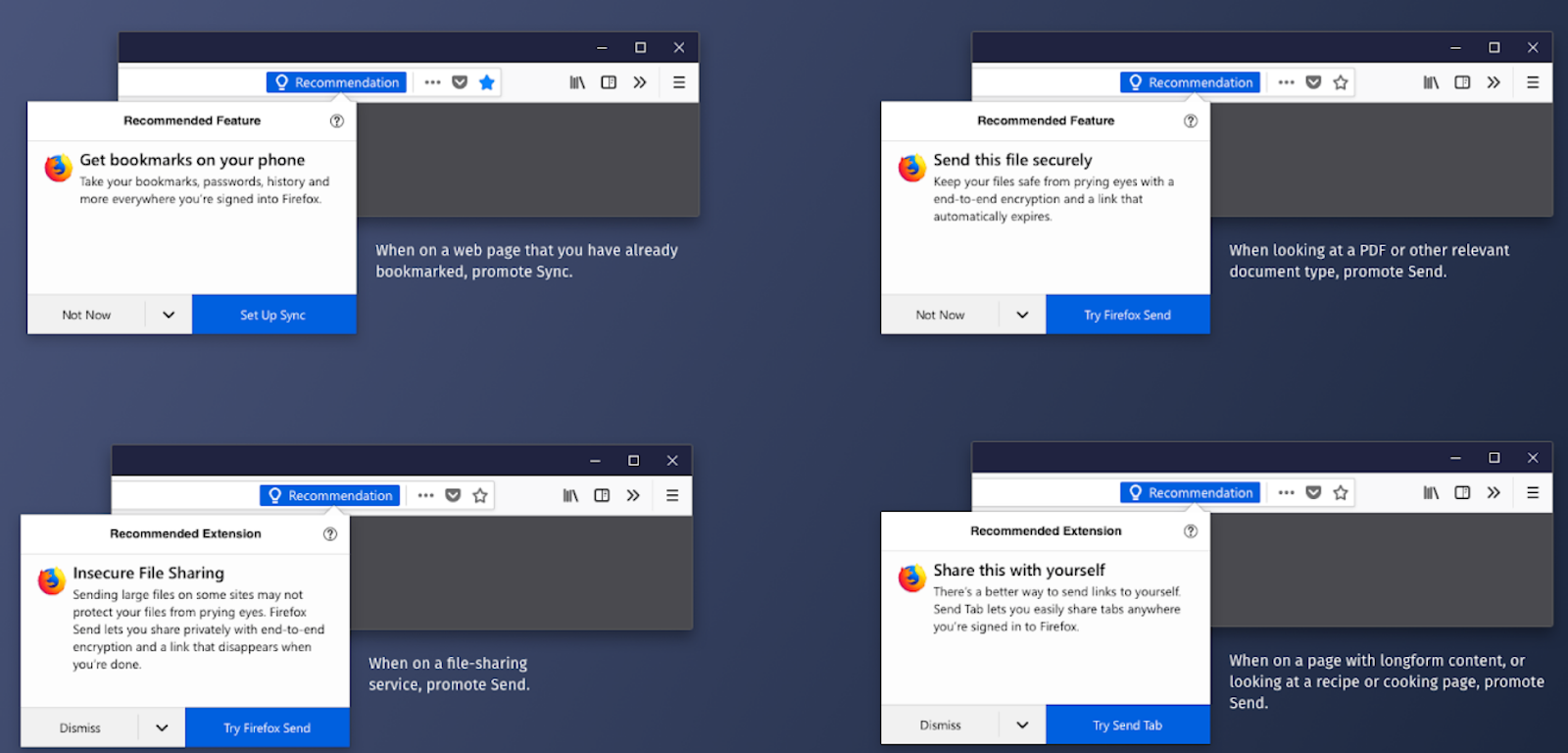

What's also interesting is that hooks were first created to reduce the overuse of <Component /> nesting as a universal hammer for the nail of code composition, because much of the components had nothing to do with UI directly. In fact, it may be that UI just provided us with convenient boundaries around things in the form of widgets, which suggestively taught us how to incrementalize them.

This to me signals that React.render() is somewhat misnamed, but its only mistake is a lack of ambition. It should perhaps be React.apply() or React.incremental(). It's a way of calling a deferred piece of code so that it can be re-applied later with different inputs, including from the inside. It computes minimum updates down a dependency tree of other deferred pieces of code with the same power.

Right now it's still kind of optimized for handling UI trees, but the general strategy is so successful that variants incorporating other reconciliation topologies will probably work too. Sure, code doesn't look like React UI components, it's a DAG, but we all write code in a sequential form, explicitly ordering statements even when there is no explicit dependency between them, using variable names as the glue.

The incremental strategy that React uses includes something like the resumable-sequential flatmap algorithm, that's what the key attribute for array elements is for, but instead of .map(...).flatten() it's more like an incremental version of let render = (el, props) => recurse(el.render(props)) where recurse is actually a job scheduler.

The tech under the hood that makes this work is the React reconciler. It provides you with the illusion of a persistent, nicely nested stack of props and state, even though it never runs more than small parts of it at a time after the initial render. It even provides a solution for that old bugbear: resource allocation, in the form of the useEffect() hook. It acts like a constructor/destructor pair for one of these persistent stack frames. You initialize any way you like, and you return to React the matching destructor as a closure on the spot, which will be called when you're unmounted. You can also pass along dependencies so it'll be un/remounted when certain props like, I dunno, a texture size and every associated resource descriptor binding need to change.

There's even a neat trick you can do where you use one reconciler as a useEffect() inside another, bridging from one target context (e.g. HTML) into a different one that lives inside (e.g. WebGL). The transition from one to the other is then little more than a footnote in the resulting component tree, despite the fact that execution- and implementation-wise, there is a complete disconnect as only fragments of code are being re-executed sparsely left and right.

You can make it sing with judicious use of the useMemo and useCallback hooks, two necessary evils whose main purpose is to let you manually pass in a list of dependencies and save yourself the trouble of doing an equality check. When you want to go mutable, it's also easy to box in a changing value in an unchanging useRef once it's cascaded as much as it's going to. What do you eventually <expand> to? Forget DOMs, why not emit a view tree of render props, i.e. deferred function calls, interfacing natively with whatever you wanted to talk to in the first place, providing the benefits of incremental evaluation while retaining full control.

It's not a huge leap from here to being able to tag any closure as re-entrant and incremental, letting a compiler or runtime handle the busywork, and forget this was ever meant to beat an aging DOM into submission. Maybe that was just the montage where the protagonist trains martial arts in the mountain-top retreat. Know just how cheap O(1) equality checks can be, and how affordable incremental convenience for all but the hottest paths. However, no tool is going to reorganize your data and your code for you, so putting the boundaries in the right place is still up to you.

I have a hunch we could fix a good chunk of GPU programming on the ground with this stuff. Open up composability without manual bureaucracy. You know, like React VR, except with LISP instead of tears when you look inside. Unless you prefer being a sub to Vulkan's dom forever?

Previous: APIs are about Policy

Next: Model-View-Catharsis

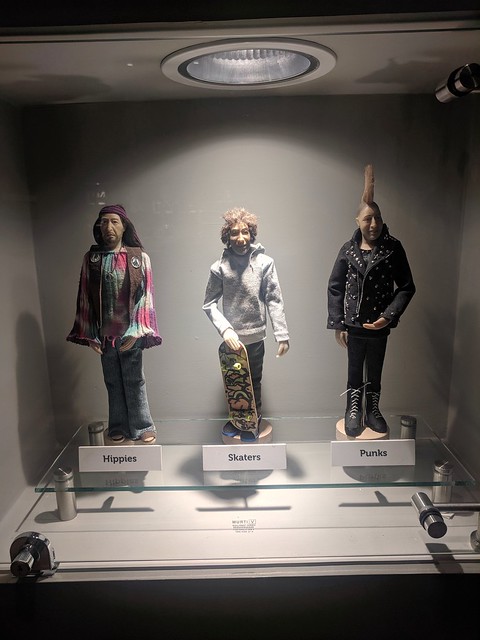

Its simplicity, those particular colours, its inclusive meaning – no wonder the Pride Flag is so immediately recognizable and embraced by so many peoples for what has become a global summer festival. Variations will evolve to distinguish the nuances of its subcultures, to be raised more as political statements – but the rainbow Pride Flag is a keeper that keeps on spreading.

Its simplicity, those particular colours, its inclusive meaning – no wonder the Pride Flag is so immediately recognizable and embraced by so many peoples for what has become a global summer festival. Variations will evolve to distinguish the nuances of its subcultures, to be raised more as political statements – but the rainbow Pride Flag is a keeper that keeps on spreading.

A very common complaint from cyclists is cycling hip pain. This post has a video showing three simple hip stretches that almost miraculously cured my own debilitating and very painful cycling hip pain.

A very common complaint from cyclists is cycling hip pain. This post has a video showing three simple hip stretches that almost miraculously cured my own debilitating and very painful cycling hip pain.