Rolandt

Shared posts

Twitter Favorites: [karj] I didn’t vote for Justin Trudeau. That said, I’m glad he’s our PM.

Get well soon, NYC. Keep transit safe, walk if the need arises.

Get well soon, NYC. Keep transit safe, walk if the need arises.

Plague 10: Picadillo

Plague dinner 10. Homemade baba ganoush, picadillo de Oaxaca, Bordeaux blanc. Salad, brownies.

In five weeks, every school kid will know the quiz question: What was the greatest catastrophe in the history of Malden? Answer: The plague of 2020. Yet, it appears we are doing little or nothing to prepare.

I cannot understand this.

We should be building ventilators. We should be building hospitals. We should be training medics.

We have perhaps 15 days.

The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning

This is a good article and I appreciate the intent but it still feels to me like a desperate argument that online learning can only be done properly by learning design specialists working with large budgets and a lot of lead time. "The need to 'just get it online' is in direct contradiction to the time and effort normally dedicated to developing a quality course," the authors write. Well yes, compared to current practice, sure. But here's the question: just how bad are the 'just get it online' courses? How much extra value does all that expertise, time and money buy you? If we could spend less money and expand our access proportionately, would it still be worthwhile? I know that the professionals won't applaud the idea of a whole bunch of amateurs doing the job. But my take is, wouldn't it be great if they could? And where is the evidence that they can't?

Web: [Direct Link] [This Post]No refunds for virtual classes

Short post from the always-negative Joann Jacobs on an issue that has been at the back of my mind since the disruption to in-person classes started: will there be tuition refunds or rebates. The concern is that students are "“being charged the same amount for what is admittedly by the university a lower quality education.” The answer from one school is "no". But instead of focusing on the messenger, as Jacobs does, we can ask the more serious question: how much more value is added by the in-person option, how much of a rebate should be offered, and (after all this is done) is the value for money sufficient to warrant going back to those $50K tuition fees? Also attached to this post is a top-notch diagram by Phil Hill describing the complete conversion to online learning by U.S. colleges, raising again the question, why would we go back?

Web: [Direct Link] [This Post]Exploring New Opportunities

The flip side of Friday’s post is the change of environment might open up opportunities to explore new ideas and means for members to engage with one another.

I love Seth’s post as a starting point:

“A standard zoom room permits you to have 250 people in it. You, the organizer, can speak for two minutes or ten minutes to establish the agenda and the mutual understanding, and then press a button. That button in Zoom will automatically send people to up to 50 different breakout rooms.

If there are 120 people in the room and you set the breakout number to be 40, the group will instantly be distributed into 40 groups of 3.

They can have a conversation with one another about the topic at hand. Not wasted small talk, but detailed, guided, focused interaction based on the prompt you just gave them.

8 minutes later, the organizer can press a button and summon everyone back together.

Get feedback via chat (again, something that’s impossible in a real-life meeting). Talk for six more minutes. Press another button and send them out for another conversation.

This is thrilling. It puts people on the spot, but in a way that they’re comfortable with.”

Be sure to read the entire post.

Easy Stakeholder Mapping Tool With Limesurvey

When I visited TechFestival in Copenhagen last September I had a conversation with a Swedish NGO representative. She at the end of our conversation quickly pulled out her phone and by answering a handful questions captured she had met me as open data relevant stakeholder, how and why she thought it was of interest. This caught my eye as something useful for my company as well, especially now that we have more people out there bumping into different actors in our field.

I installed a LimeSurvey instance on one of my company’s domain names and created a very simple survey that asks for who did you meet, where/how that happened, the type of stakeholder it is, and why you think it is of interest, plus who is filling the questions out.

The survey, collecting 5 pieces of information.

At the back-end we will look at whether this captures useful info, and how to pipe it into activities. For instance who to follow on social media, or to add to a rss reader. Or who to connect to whom, or whom to approach.

I asked all colleagues to add the little survey as a button on their phone’s home screen, so that capturing is as easy as possible. Like in the white circle on the image below.

Not that we are out and about these days, as we’re as locked down at home as everyone in the Netherlands. However we’ll bump into stakeholders online too, and we’ll start there. In a few weeks we’ll evaluate how things worked or not, what to tweak and what to do as follow up (the mapping part of stakeholder mapping).

The bookmark as button on my phone’s home screen, in the white circle.

Twitter Favorites: [brooke] Do I know anyone who HASN’T made a sourdough loaf this weekend and put it on Instagram? Please, for the love of god, announce yourself.

Do I know anyone who HASN’T made a sourdough loaf this weekend and put it on Instagram? Please, for the love of god, announce yourself.

Want to read this in more detail. (found via Ne...

Want to read this in more detail. (found via Neil Mather)

The generalist/specialist distinction is an extrinsic coordinate system for mapping human potential. This system itself is breaking down, so we have to reconstruct whatever meaning the distinction had in intrinsic terms. When I chart my life course using such intrinsic notions, I end up clearly a (reconstructed) specialist…..I call the result “the calculus of grit.” It is my idea of an inertial navigation system for an age of anomie, where the external world has too little usable structure to navigate by.

Bookmarked The Calculus of Grit (ribbonfarm)I find myself feeling strangely uncomfortable when people call me a generalist and imagine that to be a compliment. My standard response is that I am actually an extremely narrow, hidebound specialist…

On both Brexit and Coronavirus the hangover from what was done in 2020 will last until 2030s And it still only March

|

mkalus

shared this story

from |

On both Brexit and Coronavirus the hangover from what was done in 2020 will last until 2030s

And it still only March

730 likes, 115 retweets

Moulton Stowaway Bicycle: Object in Focus | V&A

|

mkalus

shared this story

from |

How has the design of the bicycle evolved over the years? Senior design curator Brendan Cormier shows us the ingenious ways in which Alex Moulton made the bicycle more portable, illustrating how firmly established objects designed for everyday use can be iterated upon and improved in order to maintain relevance in modern society.

Find out more about the contemporary objects in our collections that showcase design evolution and societal change: vam.ac.uk/collections/rapid-response-collecting

Why “Follow For A Follow” On YouTube Isn’t Helping

A few thoughts on this YouTube subscriber swap thing that’s going around… (in case you’ve missed it a LOT of musicians have been promoting the idea that we should reciprocally follow one another to help reach the 1000 subscriber limit so we can start monetising YouTube channels, and then play each other’s videos on mute to gain revenue)Â

A few thoughts on this YouTube subscriber swap thing that’s going around… (in case you’ve missed it a LOT of musicians have been promoting the idea that we should reciprocally follow one another to help reach the 1000 subscriber limit so we can start monetising YouTube channels, and then play each other’s videos on mute to gain revenue)Â

FWIW, I’ve been on YouTube for 14 years, have just shy of 2K subscribers, have other videos on there posted by bass accounts that have generated hundreds of thousands of views, but IF I’d been monetising my account from the start (that wasn’t even possible back then – at least a third of my views on there were from before there was ANY money in YouTube), my total number of views would’ve made me significantly less than $500. In 14 years. Maybe a few bucks more if I could’ve persuaded people to watch ads on them.

See, you get paid almost nothing on YT for your music. Like, effectively nothing. You get paid for people watching ads. So you’re asking the people who are watching your videos to spend hours and hours collectively watching bullshit so you can make pennies. If that’s a byproduct of you doing what you do anyway, knock yourselves out. Go for it.

But making ‘content‘ so that you can somehow start from scratch while quarantined to make any money at all through YouTube views, AND trying to get that happening through a network of other people who are also trying to make content and aren’t even following anyone based on whether they actually like what they do??? Are you high? If your understanding of who you are is that you are an artist trying to sell your work, this is not your business.

I get that you’re trying to come up with strategies to make this work at a time when we’re REALLY struggling to stay afloat, but getting people to spend hours watching stuff they aren’t invested in so you can make pennies is not a good use of our time in quarantine. It’s not good economically and it’s not good spiritually, and it’s not even remotely likely to make any sensible money for anyone but Google.

If you already have stuff on YouTube and want to earn some scraps for it, sure get registered for ad revenue. But honestly, it’s not worth anything unless THAT’S YOUR BUSINESS. Like, a full time job. A quick google search suggests that 7 MILLION views a year (it’d be a hell of a production/marketing task to get 1% of that on content you own the copyright on – remember, you won’t get paid for videos of cover versions unless you license/register them, the writer will) will pay you LESS than I make a year from 260 Bandcamp subscribers.

I’ve said it god-knows how many times, the streaming economy has no response to this. The major labels and streaming companies COMBINED initially donated less to help musicians through this than Bandcamp earned for them in one day of waiving their fees and promoting it as a day to help. One day. Rihanna has donated more than her entire industry combined, just because she gives a shit. (Spotify have since announced $10M of matched funding donations to three music-focused charities )

An economic model designed to massively prioritise paying people for already-famous music that doesn’t require a marketing or production budget is never going to be a sustainable ecosystem for a mass of creatives to earn a living. Stop trying to make fetch happen. If you’ve had a viral hit on a playlist or two on Spotify and have made some money, that’s brilliant. I want my friends and colleagues to make money, but it’s not sustainable across the system, and trying to game YouTube with some ‘follow for a follow’ nonsense is not going to suddenly get you all the kind of resilient audience who are willing to watch ads to see your stuff that is needed to make money off this.

Last thing – every person I know who is making SERIOUS money off YouTube (or is using YouTube as a significant part of their marketing funnel to a business that makes money – not the same thing) has studied this stuff to a significant level. They aren’t just great musicians or teachers or gamers or whatever. They are deep into marketing techniques, into the kind of video they need to make to get views, they study click through rates and patterns, interpret YouTube stats about viewer retention, they are constantly tweaking that shit to make it work.

My advice? Make the best art you can. Focus on the art right now. YouTube aren’t throwing anyone a lifeline. Everyone’s at home watching video, and you’re competing with people who’ve been in this game for a decade, have teams and a strategy. Just make great art, and make a case for the people in your audience who REALLY CARE ABOUT WHAT YOU DO and have the means to pay for it to help support it.

Reciprocal follow-me-back strategies have been around since MySpace, and they always suck. They are never pro-art, and result in a bunch of pushy, aggressive people seeming way more popular than their art deserves because they chase the follow-backs, not because they have anything worthwhile to share.

In short, the massive problem with this is that it assumes the the number of followers that it says you have on your YouTube page is more significant than the community of interest that the number is supposed to represent. Follow for a follow is a low-grade simulacrum of an actual community that are invested in what you do and care about it. It represents how many people were needy enough for their own follower count to go up that they would also click yours. You and your art deserve much, much better.

Do your art

Shout about the stuff you love

Invite the people who can afford to to support art – not just your art.

Stay safe.

Wash your hands.

So much to learn about emergency remote teaching, but so little to claim about online learning

The Chronicle of Higher Education published an article by Jonathan Zimmerman on March 10 arguing that we should use the dramatic shift to online classes due to Covid-19 pandemic as an opportunity to research online learning (see article here).

For the first time, entire student bodies have been compelled to take all of their classes online. So we can examine how they perform in these courses compared to the face-to-face kind, without worrying about the bias of self-selection.

It might be hard to get good data if the online instruction only lasts a few weeks. But at institutions that have moved to online-only for the rest of the semester, we should be able to measure how much students learn in that medium compared to the face-to-face instruction they received earlier.

To be sure, the abrupt and rushed shift to a new format might not make these courses representative of online instruction as a whole. And we also have to remember that many faculty members will be teaching online for the first time, so they’ll probably be less skilled than professors who have more experience with the medium. But these are the kinds of problems that a good social scientist can solve.

I strongly disagree with Zimmerman’s argument. There is a lot to study here. There is little to claim about online learning.

What we are doing right now is not even close to best practice for online learning. I recommend John Daniels’ book Mega-Universities (Amazon link). One of his analyses is a contrast with online learning structured as “correspondence school” (e.g., send out high-quality materials, require student work, provide structured feedback) or as a “remote classroom” (e.g., video record lectures, replicate in-classroom structures). Remote classrooms tend to have lower-retention and increase costs as the number of students scale. Correspondence school models are expensive (in money and time) to produce, but scales well and has low cost for large numbers. What we’re doing is much closer to remote classrooms than correspondence school. Experience with MOOCs supports this analysis. Doing it well takes time and is expensive, and is carefully-structured. It’s not thrown together with less than a week’s notice.

My first thought when I read Zimmerman’s essay was for the ethics of any experiment comparing to the enforced move to online classes versus face-to-face classe. Students and faculty did not choose to be part of this study. They are being forced into online classes. How can we possibly compare face-to-face classes that have been carefully designed, with hastily-assembled online versions that nobody wants at a time when the world is suffering a crisis. This isn’t a fair nor ethical comparison.

Ian Milligan recommends that we change our language to avoid these kinds of comparisons, and I agree. He writes (see link here) that we should stop calling this “online learning” and instead call it “emergency remote teaching.” Nobody would compare “business as usual” to an “emergency response” in terms of learning outcomes, efficiency, student satisfaction, and development of confidence and self-efficacy.

On the other hand, I do hope that education researchers, e.g., ethnographers, are tracking what happens. This is first-ever event, to move classes online with little notice. We should watch what happens. We should track, reflect, and learn about the experience.

But we shouldn’t make claims about online learning. There is no experiment here. There is a crisis, and we are all trying to do our best under the circumstances.

Katzenmaske zum Selbermachen

|

mkalus

shared this story

from |

Ich gehe davon aus, dass wir früher oder später alle mit Atemschutzmasken durch die Gegend laufen werden. Zumindest beim Einkaufen sollten wir sie jetzt schon tragen, um andere nicht nicht zu gefähren. Und wenn wir schon Maske tragen, warum dann nicht so eine außergewöhnliche, die der Wirkung einer N95 Maske nahekommt und somit besser ist als gar keine. Anleitung und Beschreibung hat Danger Ranger hier ins Netz gestellt. Mit Schnurrhaaren!

(via BoingBoing)

The Best Gas Grills

After five days of cooking burgers, barbecue, and chicken on seven top-rated grills—and weeks of researching the dozens available—we’ve decided that the Weber Spirit II E-310 is our pick as the best gas grill for most people. No grill matches its combination of exceptional performance, usability, durability, and value.

Cherry Blossom Time in Vancouver

Photographer Ken Ohrn captures Sylvia Ohrn walking in local blossom splendour.

I have previously written about Cherry Blossom Madness and the one street on the east side of Vancouver that explodes with a canopy of cherry blossoms, and tourists who are themselves the main event. Residents of the street have even had to enlist the City of Vancouver to keep the calm while car drivers jockey to visit the blooms.

There are over 43,000 cherry trees in Vancouver with fifty different varieties. You can take a look at this interactive map by the Vancouver Sun that shows the location of 16,000 cherry trees.

Normally there is a cherry blossom festival in Vancouver and you can take a look at the history of cherry trees here on their website. While many of the events for the Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival are cancelled, there are still some online events which you can look at here.

You can also view this YouTube video of images taken from previous Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival events.

Pixelmator Pro 1.6 Magenta now available

Fresh from the Pixelmator oven, we’ve just released Pixelmator Pro 1.6 Magenta, a major update you’re sure to love. ![]()

The all-new color picker

Pixelmator Pro now has a brand new color picker, designed to be incredibly powerful and full-featured, yet amazingly easy to use.

We love the Colors window, so why did we decide to make our own color picker? Well, for an app like Pixelmator Pro, it falls a little short in a few small ways. And those small things often make a big difference.

We wanted to give you an easy way to pick colors using the classic hue, saturation, and brightness control, hex and and RGB color codes, and good old color swatches. And we wanted everything to be in one place so it’s all super easy to find. We also wanted to have a beautiful and informative eyedropper for when you’re picking colors from your image. And this is the result:

![]()

We’ve also added a dedicated Color Picker tool, where the eyedropper is always active so you can quickly pick a series of colors from an image. You can also customize how the eyedropper works everywhere else in Pixelmator Pro. For example, you can change its sample size (so it picks an average color, rather than an exact sample), change which color code is displayed, or turn off displaying color names. We hope you’re as excited about this new picker as we are!

An easier way to select multiple objects

This is another great improvement to make Pixelmator Pro even easier to use — you can now drag over multiple objects to select them. Hint: to make this easier to use with illustrations and other images, lock the background layer.

Identify and replace missing fonts

Whenever you open an image with fonts that you don’t have installed on your Mac, you’ll see a handy notification letting you know. And, using the Replace Fonts feature, you’ll be able to replace those missing fonts in a snap!

Performance improvements and other goodies

Along with all this, we’ve also included some performance improvements. The image overlay — which includes things like guides, selection outlines, layer handles, and others — has been rewritten to use Metal, bringing obvious speed improvements. What’s more, you can now press the Shift – Command – h keyboard shortcut to hide or show it!

We’ve also improved the speed of layer strokes, added the ability to apply inside and outside strokes to text layers, and made a range of improvements the the shape tools, making it easier to create illustrations and drawings. All in all, it’s a pretty awesome update, even if we do say so ourselves.

If you want to know every detail about the update, head down to our What’s New page, where you’ll find the release notes and more. Otherwise, visit the Mac App Store to make sure you’re all up to date. And don’t hesitate to let us know what you think!

Zoom’s new privacy policy

Yesterday (March 29), Zoom updated its privacy policy with a major rewrite. The new language is far more clear than what it replaced, and which had caused the concerns I detailed in my previous three posts:

Those concerns were shared by Consumer Reports, Forbes and others as well. (Here’s Consumer Reports‘ latest on the topic.)

Mainly the changes clarify the difference between Zoom’s services (what you use to conference with other people) and its websites, zoom.us and zoom.com (which are just one site: the latter redirects to the former). As I read the policy, nothing in the services is used for marketing. Put another way, your Zoom sessions are firewalled from adtech, and you shouldn’t worry about personal information leaking to adtech (tracking based advertising) systems.

The websites are another matter. Zoom calls those websites—its home pages—”marketing websites.” This, I suppose, is so they can isolate their involvement with adtech to their marketing work.

The problem with this is an optical one: encountering a typically creepy cookie notice and opting gauntlet (which still defaults hurried users to “consenting” to being tracked through “functional” and “advertising” cookies) on Zoom’s home page still conveys the impression that these consents, and these third parties, work across everything Zoom does, and not just its home pages.

And why call one’s home on the Web a “marketing website”—even if that’s mostly what it is? Zoom is classier than that.

My advice to Zoom is to just drop the jive. There will be no need for Zoom to disambiguate services and websites if neither is involved with adtech at all. And Zoom will be in a much better position to trumpet its commitment to privacy.

That said, this privacy policy rewrite is a big help. So thank you, Zoom, for listening.

The iPad at 10: Emerging from the Shadow of the iPhone

The trouble with looking back over a long period is that time has a way of compressing history. The clarity of hindsight makes it easy to look back at almost anything and be disappointed in some way with how it turned out years later.

We certainly saw that with the anniversary of the introduction of the iPad. Considered in isolation a decade later, it’s easy to find shortcomings with the iPad. However, the endpoints of the iPad’s timeline don’t tell the full story.

It’s not that the device is short on ways it could be improved; of course, it isn’t. However, the path of the iPad over the past decade isn’t a straight line from point A to point B. The iPad’s course has been influenced by countless decisions along the way bearing consequences that were good, bad, and sometimes unintended.

Supported By

Concepts

Concepts: Where ideas take shape

The 10th anniversary of the iPad isn’t a destination, it’s just an arbitrary point from which to take stock of where things have been and consider where they are going. To do that, it’s instructive to look at more than the endpoints of the iPad’s history and consider what has happened in between. Viewed from that perspective, the state of the iPad ten years later, while at times frustrating, also holds reason for optimism. No single product in Apple’s lineup has more room to grow or potential to change the computing landscape than the iPad does today.

Just a Big iPhone

The original iPad.

No product is launched into a vacuum, and the origin of the iPad is no different. It’s influenced by what came before it. In the ten years since April 3, 2010, that context has profoundly affected the iPad’s adoption and trajectory.

In hindsight, it seems obvious that the iPad would follow in the footsteps of the iPhone’s design, but that was far from clear in 2010. Take a look at the gallery of mockups leading up to the iPad’s introduction that I collected for a story in January. The designs were all over the place. More than two years after the iPhone’s launch, some people still expected the iPad to be a Mac tablet based on OS X.

An early Apple tablet mockup (Source: digitaltrends.com).

However, after spending over two years acclimating consumers to a touch-based UI and app-centric approach to computing, building on the iPhone’s success was only natural. Of course, that led to criticisms that the iPad was ‘just a big iPhone/iPod touch’ from some commentators, but that missed one of the most interesting and overlooked part of the iPad’s introduction. Sure, Apple leaned into the similarities between the iPhone and the iPad, but even that initial introduction hinted at uses for the iPad that went far beyond what the iPhone could do.

Apple walked a careful line during that introductory keynote in January 2010. Steve Jobs’ presentation and most of the demos were a careful mix of showing off familiar interactions while simultaneously explaining how the iPad was better for certain activities than the iPhone or the Mac. That went hand-in-hand with UI changes on the iPad that let apps spread out, flattening view hierarchies. The company didn’t stop there, though.

Apple also provided a glimpse of the future. Toward the end of the iPad’s debut keynote, Phil Schiller came out for a demo of iWork. It was a final unexpected twist. Up to this point, the demos had focused primarily on consumption use cases, including web and photo browsing, reading in iBooks, and watching videos.

The iWork demo was a stark departure from the rest of the presentation. Schiller took the audience on a tour of Pages, Numbers, and Keynote. They weren’t feature-for-feature copies of their Mac counterparts. Instead, each app included novel, touch-first adaptations that included innovative design elements like a custom software keyboard for entering formulas in Numbers. Apple also introduced a somewhat odd combination keyboard and docking station accessory for typing on the iPad in portrait mode.

What stands out most about this last segment of the iPad keynote isn’t that the iPad could be used as a productivity tool, but the contrast between how little time was spent on it compared to how advanced the iWork suite was from day one. As I explained in January, I suspect that to a degree, Apple was hedging its bets. Perhaps, like the original Apple Watch, the company knew it had built something special, but it wasn’t sure which of the device’s uses would stick with consumers.

The iPhone was still a young product in 2010. It was a hit, but consumers were still new to its interaction model. The App Store was relatively new, too, and filled with apps, many of which would be considered simple by today’s standards.

By tying the iPad closely to the iPhone, Apple provided users with a clear path to learning how to use its new tablet. Spotlighting familiar uses from the iPhone and demonstrating how they were better on the iPad tapped into a built-in market for the company’s new device. But the more I look at that first iPad keynote in the context of the past decade, the more I’m convinced that there was something else happening during that last segment.

Apple knew it was on to something special that went beyond finding better ways to do the same things you could already do on an iPhone. If that was the extent of the iPad’s potential, the company wouldn’t have invested the considerable time it must have taken to adapt the iWork suite to the iPad, and later update the Mac versions to align better with their iOS counterparts. iWork was a harbinger of the more complex, fully-featured pro apps on the iPad that have only recently begun to find a foothold on the platform.

However, there’s no doubt that it was the emphasis on consumption apps that set the stage for the iPad’s early years.

The First Five Years

Initial sales of the iPad were strong. The first day it was available, Apple sold 300,000 iPads. After four weeks, that number climbed to one million. Adoption was faster than the iPhone. In fact, it was faster than any non-phone consumer electronic product in history, surpassing the DVD player.

The sales results were a vindication of the iPad’s launch formula. So when it was time to roll out the iPad 2, Apple sought to capture lightning in a bottle again by using the same playbook, right down to the black leather chair used for onstage demos in the first keynote.

A GarageBand for iPad billboard.

The structure of the iPad 2 presentation was the same too, closing with a demo of new, sophisticated apps from Apple that was reminiscent of Schiller’s iWork demo. This time, the company showed off iMovie and GarageBand. iWork had been impressive the year before, but something about the creative possibilities of making movies and music on a device you held in your hands recaptured the excitement and promise the iLife suite had ignited on the Mac years before. In 2010, Apple showed that you could get work done on an iPad, but in 2011, the company showed customers they could make art.

In the wake of the iPad 2 keynote, the iPad seemed poised to jump-start a computing revolution, but instead, Apple’s iPad efforts appeared to stall. Steve Jobs’ passing in late 2011 may have been a contributing factor, but paradoxically, it was Apple’s successful strategy of tying the iPad so closely to the iPhone that also held it back.

iPad sales continued to climb in 2011 and 2012. Apple responded by rapidly iterating on the device and expanding the lineup. In 2012 alone, Apple released the third and fourth generation iPads, plus the iPad mini. By the time the ultra-thin iPad Air debuted in late 2013, though, things had begun to take a turn for the worse.

The original iPad Air.

After those first two keynotes, Apple’s push into productivity and creativity apps on the iPad slowed. At the same time, iPads were built to last. Users didn’t feel the same sense of urgency to replace them every couple years as they did with iPhones. Coupled with the fact that few apps were pushing the hardware, sales began to decline.

The picture wasn’t completely bleak, though. Third parties took up the cause and pushed the capabilities of the platform with apps like Procreate, Affinity Photo, Editorial, and MindNode, and for some uses, the iPad was a worthy substitute for a Mac. However, with the iPad still moving in lockstep with the iPhone, developers and users began to run up against limitations that made advancing the iPad as a productivity and creativity platform difficult.

Chief among the stumbling blocks were the lack of file system access and multitasking. The app-centric nature of iOS worked well for the iPhone, but as apps and user workflows became more sophisticated, the inflexibility of tying files to particular apps held the iPad back. The apps-first model was simple, but processing a file in multiple apps meant leaving a trail of partially completed copies in the wake of a project, wasting space, and risking confusion about which file was the latest version.

The lack of multitasking became a speed bump in the iPad’s path too. The larger screen of the device made multitasking a natural fit. However, even though the hardware practically begged to run multiple apps onscreen, the OS wasn’t built for it, and when it finally was, the first iterations were limited in functionality.

We don’t know what the internal dynamic was at Apple during this time, but the result was that, despite early optimism fueled by the iWork apps, GarageBand, and iMovie, the iPad failed to evolve into a widely-used device for more sophisticated productivity and creative work. It was still a capable device, and increasing numbers of users were turning to it as their primary computer. However, that only added to the building frustration of users who sensed the platform’s progress leveling off just as they were pushing it harder.

Pro Hardware

As the first five years of the iPad concluded, sales continued to decline. However, 2015 marked the first signs of a new direction for the iPad with the introduction of the first-generation iPad Pro, a product that began to push the iPad into new territory.

The original iPad Pro.

The original iPad Pro was a significant departure from prior iPads. Not only was it Apple’s most powerful iPad, but it introduced the Apple Pencil and Smart Keyboard cover.

The Pencil added a level of precision and control that wasn’t possible using your finger or a third-party stylus to draw or take notes. With tilt and pressure sensitivity and low latency, the Pencil opened up significantly more sophisticated productivity and creative uses. The Smart Keyboard did the same for productivity apps, turning the iPad into a typing-focused workstation.

The Apple Pencil.

The hardware capabilities of the iPad Pro have continued to advance steadily, outpacing desktop PCs in many cases. However, sophisticated hardware alone wasn’t enough to propel the iPad forward. It was certainly a necessary first stop, but Apple still had to convince developers to build more complex pro apps that made use of the iPad’s capabilities.

Pro Apps and Business Models

As the first decade of the iPad comes to a close, Apple continues to grapple with fostering a healthy ecosystem of pro-level apps. For most of the past decade, the iPad app ecosystem has been treated the same as the iPhone’s. The company, however, seems to have recognized the differences and has made adjustments that have substantially improved the situation.

As of the last time Apple reported unit sales, iPad sales were roughly double those of the Mac, but far smaller than the iPhone.

The challenge of the iPad market is that it’s much smaller than the iPhone market. At the same time, pro-level apps are inherently more complex, requiring a substantially greater investment than many iPhone apps. That makes embarking on these kinds of iPad-focused pro app projects far riskier for developers.

However, Apple’s recent moves have significantly improved the situation. The first step was to implement subscriptions. Although they aren’t limited to the iPad, subscription business models have provided developers with the recurring revenue necessary to maintain sophisticated apps long term. Subscriptions haven’t been popular with some consumers, especially when a traditionally paid up front app transitions to a subscription. Still, the developers I’ve spoken with who have made it through the transition are doing better than before.

Mac Catalyst’s introduction.

The second and less obvious move Apple made was the introduction of Mac Catalyst apps, which allow iPad developers to bring their apps to macOS. To be sure, Mac Catalyst is designed to breathe new life into the stagnant Mac App Store, but it also benefits the iPad. As I wrote last summer, Mac Catalyst aligns the iPad more closely with the Mac than ever before. By facilitating simultaneous development for both platforms, Mac Catalyst significantly increases the potential market of users for those apps and encourages the use of the latest iPadOS technologies, both of which promise to advance the platform.

The keyboard shortcuts in Twitter’s Mac Catalyst app migrated back to its iPad app.

A good example of this in action is Twitter’s Mac and iPad apps. Twitter’s iPad app languished for years; however, last fall Twitter launched a Mac Catalyst version of its app. Although the app had some rough edges, it included features you’d expect on the Mac like extensive keyboard shortcuts. Less than three weeks later, the iPad app was updated with extensive keyboard support too.

The third software piece of the puzzle Apple has addressed is iPadOS. Going into WWDC 2019, significant iPad-specific updates to iOS were anticipated, but no one saw a separate OS coming. Currently, the overlap between iPadOS and iOS is extensive, but the introduction of iPadOS sent a message to developers that Apple was ready to start differentiating the feature sets of its mobile OSes to suit the unique characteristics of each platform. Over time, I expect we’ll see even more differences between the platforms emerge, such as the cursor support added to iPadOS with iPadOS 13.4.

It’s still too early to judge whether the software-side changes to the iPad will succeed in encouraging widespread adoption of the latest hardware capabilities. However, early signs are encouraging, such as Adobe’s commitment to the platform with Photoshop and the announced addition of Illustrator. My hope is that with time, Apple’s substantial investment in both hardware and software will create a healthy cycle of hardware enabling more sophisticated apps and apps pushing hardware advancements.

The trajectory of the iPad is one of the most interesting stories of modern Apple. Taking off as strongly as the device did in the aftermath of the iPhone made it look, for a time, like Apple had repeated the unbounded success of the iPhone.

Although the company managed to jump-start sales of the iPad by tying it to the iPhone, it became clear after a couple of years that the iPad wasn’t another iPhone. That doesn’t make the iPad a failure. It’s still the dominant tablet on the market, but it hasn’t transformed society and culture to the same degree as the iPhone.

With the introduction of advanced hardware, new accessories, iPadOS, Mac Catalyst, and new business models, the iPad has begun striking out on its own, emerging from the shadow of the iPhone. That’s been a long time coming. Hitching the iPad to the iPhone’s star was an undeniably successful strategy, but Apple played out that thread too long.

Fortunately, the company has begun to correct the iPad’s course, and I couldn’t be more excited. The hardware is fast and reliable, and soon, we’ll have an all-new, more robust keyboard that can double as a way to charge the device. Perhaps most intriguing, though, is the introduction of trackpad and mouse support in iPadOS 13.4. Although it was rumored, most people didn’t expect to see trackpad support until iPadOS 14. I’m hoping that means there is lots more to show off in the next major release of iPadOS.

Ten years in, the iPad is still a relatively young device with plenty of room to improve. Especially when you consider that the iPad Pro with its Apple Pencil and Smart Keyboard is only five years old, there is lots of room for optimism for the future. The iPad may have been pitched as a big iPhone at first, but its future as a modular computing platform that is neither a mobile phone nor traditional computer is bright.

You can also follow all of our iPad at 10 coverage through our iPad at 10 hub, or subscribe to the dedicated iPad at 10 RSS feed.

Support MacStories Directly

Club MacStories offers exclusive access to extra MacStories content, delivered every week; it’s also a way to support us directly.

Club MacStories will help you discover the best apps for your devices and get the most out of your iPhone, iPad, and Mac. Plus, it’s made in Italy.

Join NowShould You Sanitize Your Groceries?

With the global spread of the coronavirus pandemic, many people are cooking from home more than ever before. Though you’re probably doing your best to practice social distancing and stay inside, you may be wondering if the food, packaging, and grocery bags you bring into your home need to be sanitized. It’s a valid concern, considering all of the hands that have touched the apples in your fridge or the cans of tuna in your pantry.

HQ Trivia is officially back, less than two months after shutting down

Once-popular mobile trivia game HQ Trivia has been resurrected after shutting down in mid-February.

On March 29th, the app sent out a push notification to players stating that a new game would be going live that night. HQ co-founder Rus Yusupov also confirmed on Twitter that HQ was indeed making a return.

Bringing @hqtrivia back tonight with @mattwasfunny!! 9p ET on the HQ app

— Rus (@rus) March 29, 2020

According to a subsequent report from The Wall Street Journal, HQ is back thanks to an acquisition by an anonymous investor. As a result, HQ is reportedly planning to air consistent games, although a specific schedule has yet to be confirmed.

On February 14th, HQ announced that it would be ceasing operations effective immediately, citing a lack of investors. The app has also faced a number of hurdles over time, including a steady decline in downloads and reported company turmoil following the death of co-founder Colin Kroll.

At the time of shutdown, fans who had any outstanding cash prizes to redeem were seemingly out of luck. However, HQ host Matt Richards confirmed on Twitter that the show’s revival means players will be able to claim their earnings starting this week. Specific details as to how this will work haven’t yet been mentioned.

Yo. You heard??!? @hqtrivia is back tonight at 9pm eastern! Download the app now! Also if you been waiting to cash out, you’ll be able to this week!

— Matt Richards (@mattwasfunny) March 30, 2020

As part of its return, HQ also confirmed that it is donating $100,000 USD (about $141,000 CAD) to non-profit World Central Kitchen, which is providing food to people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, HQ says it will match players’ cash prizes with donations to other organizations with philanthropic efforts related to COVID-19.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

The post HQ Trivia is officially back, less than two months after shutting down appeared first on MobileSyrup.

Branding And Grandstanding

I sometimes listen to branding "experts" talk and wonder if they live on the same planet I do. I hear them say...

- Consumers want to “join the conversation” about brands.

- Consumers want to co-create with brands.

- Brands need to create communities of engaged consumers to be successful.

- Consumers want a relationship with brands.

- Consumers want brands that align with their values.

First of all, I don't like the word branding. It's like so many words in the dreadful lexicon of marketing -- far too open to interpretation to mean anything specific. There is nothing stupid you can do with a logo that can't be excused as "branding."

Yet, despite my misgivings about branding "experts," I believe that creating a well-known, desirable brand is the highest achievement of advertising. So what the hell are we talking about here? Let's do a little thinking.

As stated above, creating a well-known, desirable brand is the highest attainment of advertising. There are people who would disagree and say that creating a best-selling product is advertising's highest attainment. They are wrong. Advertising alone cannot create a best-selling brand or product. There are far too many elements in marketing, and business in general, that influence product sales. Advertising cannot affect product quality, distribution, pricing, product design, etc. As Mark Ritson often points out, marketing is a lot more than communication.

In the long run, no amount of brilliant advertising and its concomitant brand value can overcome a shitty, ugly product that tastes bad, is hard to find and is unaffordable or unprofitable.

And yet brand babblers seem to think that every business problem is a branding problem. They rattle on and on about the power of "the brand" until you want to shoot yourself. Or them. They inflate the importance of what they do and disguise their ignorance of the complex nature of business success, behind a vague, non-specific curtain - the magical mystery module of "branding."

Many well-known and respected brands have died ignominious deaths (e.g., Polaroid, Oldsmobile, Kodak) -- not necessarily because their "branding" sucked, but because either their products couldn't cut it anymore, or they fell behind the competition, or their financials were cockeyed, or some non-communication aspects of their marketing strategy were inadequate.

To wit, I suspect that one of the economic consequences of the current CV tragedy will be the demise of several "major brands" who have been living on investor money instead of operational income.

Successful "branding" can help make a product more desirable and it can raise the perceived value of a product. In general it can raise the likelihood that a business or product will be successful.

Yes, creating a desirable brand is the highest achievement of advertising, but...

No, creating a desirable brand is not nearly a guarantee of business success.

There are a lot of contingencies in creating a successful business. There are nuts and bolts, and wind, rain, and snow, and salt and pepper, and a little of this and a lot of that.

Despite the implications and assertions of brand babblers, in no way does successful "branding" lead inexorably to a successful business. Getting "the brand" right is a significant component of marketing success, but you gotta get a whole lot of other things right first.

Simulating an epidemic

3Blue1Brown goes into more of the math of SIR models — which drive many of the simulations you’ve seen so far — that assume people are susceptible, infectious, or recovered.

Tags: 3Blue1Brown, coronavirus, epidemic, simulation

Why Providing Free Parking For Health Care Workers is The Right Thing To Do

Photo by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels.com

Photo by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels.comPrice Tags really is about active transportation advocacy but I have had a reminder from a few health care providers that during the COVID-19 pandemic things are a bit different.

People working in the Emergency and Critical Care sections of hospitals that are potentially exposed to COVID-19 should NOT be taking transit, and physical distancing by walking/cycling at night is often not an option. Couple that with a reduced transit schedule and longer hours, and the question becomes~should we be charging these health care workers for parking during the crisis?

Joe Pinkstone of the Daily Mail reports on the JustPark app in Great Britain that allows hospital staff to park close to hospitals for free during the Covid-19 crisis. That company has 2,000 spaces listed for health care workers at 150 different hospitals in the country. In 48 hours 250 health care workers took advantage of the free parking.

Just Park is the most used parking app in Britain and allows drivers to reserve a space in advance. The company is waiving all fees in connection to creating more parking space for health care workers. JustPark went one step further asking people and businesses with available parking spaces near hospitals to also donate their space to these healthcare workers during the pandemic.

Of course it is British National Health Service policy to charge for parking at hospitals, and there already is some free car parking for staff “through a pre-approved list”. But in Britain there has been increasing usage of all available hospital parking by staff and by patient families.

In Sydney Australia Mayor Clover Moore is asking her Council to provide free 24 hour access to parking for all essential workers including those in health care.

As Mayor Moore wrote on twitter, “This an unprecedented health emergency. We stand ready to support our residents, businesses, cultural and vulnerable communities through this challenging time.”

UPDATE March 31~B.C. Hospitals are now providing free parking at hospitals. The City of Vancouver is no longer charging for using meter space during pandemic.

What Streets Should Vancouver Close for Walking, Rolling & Physical Distancing?

The province of Nova Scotia has come up with the slogan “Exercise, don’t socialize” to describe the new behaviour required of people in public. During the Covid-19 crisis everyone is being asked to practice physical distancing, staying two meters or six feet away from people when outside your home.

But as anyone that has tried to walk or roll with the required physical distancing of two meters will know, the sidewalks in Vancouver are just not wide enough. The standard for new sidewalks varies from 1.2 meters wide to 1.8 meters wide and does not offer enough space for two people to pass each other safely with the Covid-19 required distance.

Walking is good for you to maintain physical and mental health, and is encouraged by Dr. Bonnie Henry, the Province’s Medical Health Officer in this video clip by Emad Agahi with CTV News.

The Globe and Mail’s Oliver Moore has written that both Toronto and Vancouver are examining ways to make some parts of the street network closed to vehicular movement to allow pedestrians to spill out into some streets for recreation and to maintain the required physical distancing.

The thinking behind walking on connected streets has already been done in Vancouver where 25 years ago the Urban Landscape Taskforce composed of interested citizens, several who were landscape architects, came up with the ambitious Greenways Plan.

I have previously written about this extraordinary plan that came from the work of these citizens. What they termed “greenways” are actually a network of “green streets” that link traffic calmed ability accessible streets with good amenities to schools, parks, shops and services. There are 140 kilometers of greenways, with a network of fourteen city greenways that go boundary to boundary in Vancouver. The pattern language was derived from the Seawall and the Seaside Greenway route which provides Vancouverites with routes near water and forms one quarter of the whole network.

The original intent was to have a city greenway go through each neighbourhood and be a 25 minute walk or a ten minute bike ride from every residence.

The Greenway network plan was quietly backburnered during Vision’s political reign at city hall in favour of bike routes. But these traffic calmed routes that have sidewalks, connections to parks with restrooms, curb drops on corners to facilitate accessibility , wayfinding and public art still exist. You may have walked or biked down Ontario Street or 37th Avenue (the Ridgeway Greenway from Pacific Spirit Park to Central Park in Burnaby) which form two of the routes. Downtown, Carrall Street is also a greenway.

These streets lend themselves well to closure for all but local traffic and emergency vehicles. That was the intent when they were first conceived, that they could be closed for pedestrian and biking use. And as the city develops, these streets may be permanently closed in the future, forming new linear parks in a densifying city fifty years in the future.

New York City’s Mayor de Blasio has announced a plan to close two streets to traffic in each of the city’s neighbourhoods which Streetsblog calls “completely underwhelming”. There’s no indication if the City is thinking of a short street or a grand gesture like closing Broadway.

The lack of information suggests that there’s not been much thought put into the creation of a connected street network for sidewalk users that now need more space, not only to exercise, but be able to get somewhere while maintaining the ever crucial physical distancing.

Images: radiocms, businessday.ng, sightlines

What’s Next For CoVid-19: Some Wild Guesses

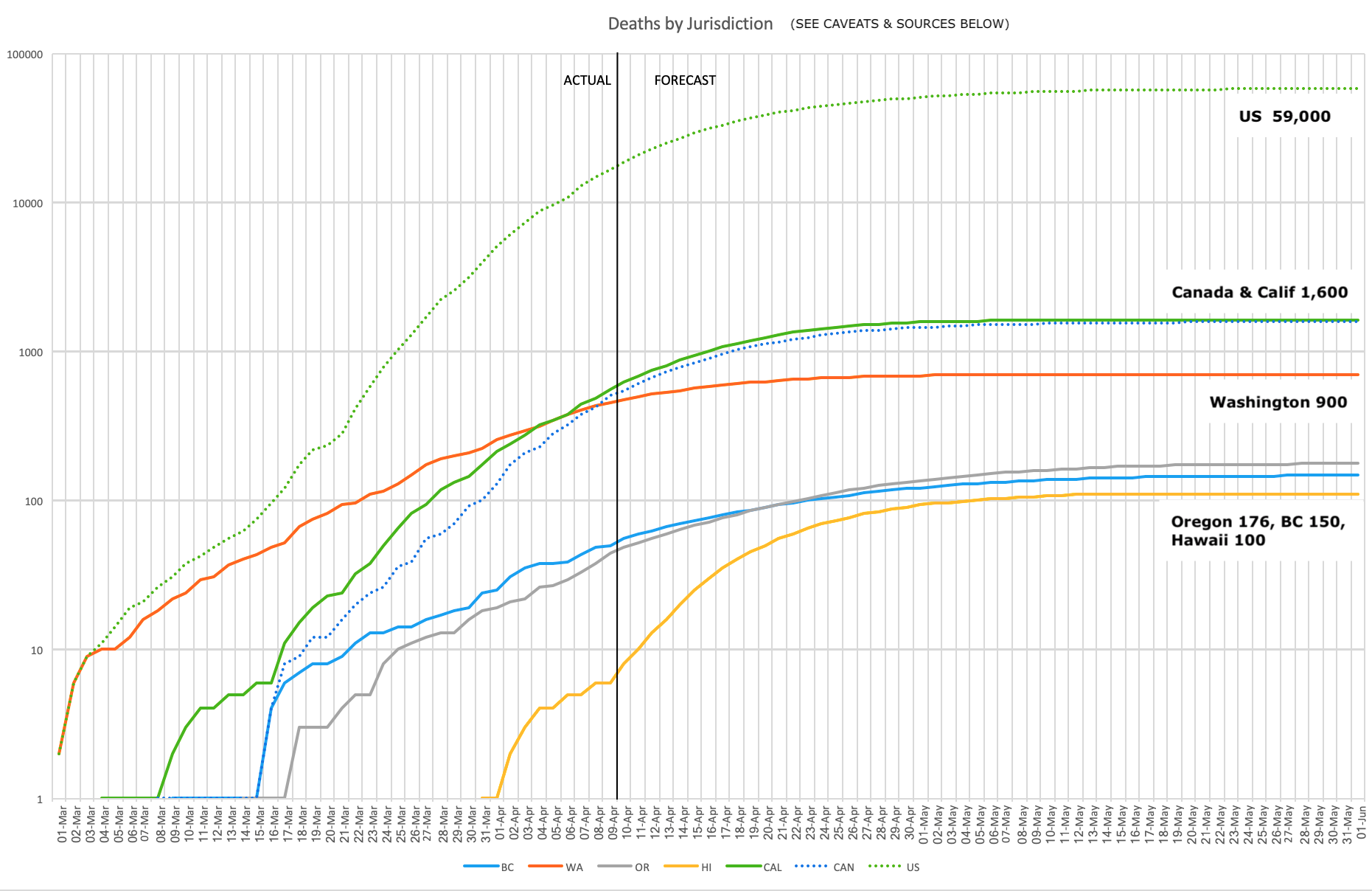

Current CoVid-19 deaths for North America West Coast jurisdictions to [EDIT] April 9th per the nCoVid2019 Dashboard, and projected most likely (95% confidence intervals: +/- 50%) total deaths to the end of this wave of the pandemic for each jurisdiction per U of Washington IHME projections as at [EDIT] April 7th. Interpolations of this data for Canadian jurisdictions are mine. Click on image for larger version. Download the latest version of this Excel chart and data. (I plan to keep it current until at least June 1.)

Caveat 1: I am not an expert in this subject, and these are only my wild informed guesses, subject to drastic future change and possibly great retroactive embarrassment. But I thought I’d try to summarize how it looks to me at this pivotal point, based on my experience and research.

Caveat 2: The above IHME projections are much more optimistic than just a week ago (1/3 fewer projected total deaths). But this assumes no further waves and no slackening of social distancing until either (1) resources exist to do exhaustive ongoing testing, or (2) an effective vaccine is fully implemented. In my opinion (and that of other models) this is an extremely optimistic assumption, and death rates 3-10x this level over the next two years are more likely. It is also likely that actual deaths have been and will be much higher than official reports due to inadequate testing and inconsistent certifications and data collection processes.

The most important things to keep in mind right now IMO:

|

LEARNING FROM PAST PANDEMICS

When I worked 12 years ago with the Ministry of Health with a special group hired to learn the lessons of SARS so there would be no repetition of the mistakes made then, we studied the epidemiology not only of SARS (CoV-1) but of various bird flus (H5N1, H7N9), swine flus (H1N1), and the 1918 pandemic (“Spanish flu”, also an H1N1).

What was so remarkable about this work is that most of what we would ideally like to know/learn about these diseases we could not learn, for a number of reasons — mostly about how incredibly little we really understand viruses and how they proliferate, but also because the history is still unclear. You would think, for example, that by now we would know where the 1918 pandemic arose, but we remain utterly clueless, with at least 3 major theories, all of them somewhat suspect.

We also can’t yet agree on how many died from the 1918 virus, with estimates varying by more than an order of magnitude.

Nevertheless, there is much to learn from that pandemic, and I’d commend this New Yorker video to you — an interview with John Barry, a writer who’s spent much of his life studying it.

Some things that we did learn, that now seem to have become lost in the shuffle:

- Flu pandemics come in waves. The severest wave in 1918 was the second, not the first. And it wasn’t (so much) because people got complacent and eased restrictions when the first wave abated; it was because viruses can mutate incredibly quickly, and the second wave arose from a much, much more virulent strain.

- Unlike most flu viruses, including the first 1918 wave virus, the second wave 1918 mutation struck almost entirely young people. It did this by inciting what is called a cytokine storm in the bodies of its victims. It wasn’t the virus or any side effects of the virus (like pneumonia) that killed the second wave victims, it was the victims’ own immune systems. So those with autoimmune disorders (hyperactive immune systems) were devastated, while those with suppressed immune systems were almost entirely spared (fewer than 1% of second wave victims were over 65).

- There were several waves of the 1918 virus after the second one, but a peculiar paradox made them much milder: The second mutation essentially ran short of available hosts, and had to mutate to survive. The second mutation was simply too potent for its own good, and essentially eradicated itself by mutating into a much milder form.

MODELS OF WHAT TO DO NEXT TIME

The economic impact of this virus, due to our unpreparedness for it, will be staggering. There is a significant risk of a long and deep economic depression (more on that in a future article). But this didn’t have to be.

Some jurisdictions have been largely spared both the health and economic costs of this virus, notably Taiwan. Lessons from their experience and preparedness:

- A process must be in place to enable rapid and repeat testing of every citizen, to quickly isolate the disease. The cost of being ready with swabs, masks, sanitizers, protective shields and test equipment pales in comparison with nationwide economic shutdowns, and such shutdowns are needed only because we have no idea who has the virus now. It is very likely that actual positive cases (if we had the tools to test for them) would be about an order of magnitude (10x) the current “official” figures, which have resulted from testing only those who already exhibit strong symptoms.

- In Taiwan, spreading fake news, hoarding, price-gouging and other actions that exploit and inflame the situation are indictable offences and considered shameful, not shrewd, behaviours. There, businesses and schools and restaurants are re-opened and life is nearly normal, and there’s been very little effect on the national economy.

- The town of Vo, in Italy, had the luxury of having the equipment and political will to test and retest every one of its 3,300 residents and isolate those who tested positive, even if asymptomatic. Their experience is a model for every community in the world to follow, if we’re willing to learn from it.

PREVENTING PANDEMICS IN THE FIRST PLACE

While the above models can dramatically mitigate the impact of pandemics when they first occur, it would be even better if we were to prevent them happening in the first place. When Dr Michael Gregor was working in epidemiology a decade ago, he published his findings on the history of human pandemics and their causes. He revealed that virus transmission to humans only became possible with the domestication of animals 10,000 years ago, and all known human viral infections (poxes etc) have their origin in domesticated animals or the consumption of bushmeat — without it there is no way for viruses to move from their endemic animal hosts to humans who have no immunity to them (hence leading to pandemics).

Two centuries ago pandemics became more prevalent again, commensurate with the intensification of “industrial” agriculture. Then with the development of vaccines, infectious diseases were almost eradicated from the planet by the 1970s, causing some health leaders to predict that such diseases would never again cause pandemics.

But then suddenly there was a third huge upswing in novel infectious diseases, starting just 30 years ago. This corresponded with the order-of-magnitude increase in CAFEs (factory farming) of both domesticated and “exotic” birds and mammals for human food. Pangolins may the source of SARS CoV-2 (the current coronavirus that is expressed as CoVid-19).

There is nervous laughter around the room when Michael says, at the end of the 2009 presentation linked above, that “we could well face a situation in the near future where every American might have to shelter in place for as much as three months to prevent spread of a global lethal pandemic”.

It is to be hoped that, along with all the other learnings from this current horrible outbreak, we take to heart that only by completely ending the three sources of the recent upsurge in pandemic risks — (1) disturbance of the last wild places on the planet that harbour viruses for which there is no natural human immunity, (2) the bushmeat trade including domestication of “exotic” species for food, and (3) factory farming — will there be any chance that situations like that we are currently facing will not become increasingly frequent and dangerous.

But I would be surprised if there’s even an acknowledgement of this cause, outside an increasingly censored and silenced scientific and medical community.

MORE INFO

- The charts at the top of this post came from IHME projections, and the underlying data is available here if you want to make your own or track the accuracy of them. They’re especially useful if you’re in a state that will likely face severe hospital bed, ICU or ventilator shortages and hence excess preventable deaths: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Michigan, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, Vermont and Massachusetts.

- The IHME used in its modelling information on other countries’ death rates after the number of deaths and infections reached a certain base level (“trajectories”). Our World in Data is maintaining excellent charts on trajectories. So is John Burn-Murdoch for the UK Financial Times.

- The data suggest that the mortality rate, on average, is converging on a rate of 1% of those infected. But the number of people testing positive (due to drastically limited testing stemming from unavailability of test kits and testing resources) is wildly underestimated (the actual number of those who would be testing positive if everyone had been tested is likely 8-20x the reported numbers). That means, if the projections pan out, that only 1.5-2.5% of North Americans would actually test positive at some point during the current wave, if the test were available. Without social distancing, it was estimated that 25-50% of the population would eventually contract the disease. This is the power of social distancing: It is almost certainly saving tens of millions of lives worldwide. It is these tens of millions of lives saved that we must weigh against the horrific economic cost of this pandemic, which is only beginning to emerge.

WHAT TO DO NOW

- Depends on your situation, of course. If you’re needed in the food, health care and other essential fields, thank you for continuing to do what you do. If you have things you can give away safely to people who would benefit from them, of course please do so. If you’re in financial peril as a result of the economic shutdown, the resources available to help differ in each jurisdiction.

- [Edit: Added Mar 30] If you can, please get involved in the various “mutual aid networks” that have sprung up since the pandemic started. Here’s a summary of how they work. Here’s a US directory. Here’s a global directory. Most communities have something like this going for peer-to-peer support, as governments are often overwhelmed, too distant, underprepared or in some cases in denial. [Thanks to Kevin Jones for reminding me about this.]

- If you’re like most of us, the next few weeks especially will bring a lot of anxiety, and feelings of anger, being trapped, feeling shameful etc. These are all manifestations of grief (thanks to Maureen Nicholson for the link). There are many online resources on coping psychologically with this. Here’s one (thanks to John Graham for the link) that I find useful.

- Keep up the pressure to sustain social distancing on your government, if it’s dragging its heels or proposing to relax the rules. Here are the worst offenders globally. Likewise if your peers are flaunting the rules (the link above also has a tab on citizen behaviours, which largely parallels their governments’). Millions of lives are at stake.

- Limit your time on useless social media and other media that are mostly or entirely unsupported opinion, useless information and misinformation. If it’s not actionable, and doesn’t give you any sense of comfort that you’re doing the right things by being overcautious, and that it’s going to be OK, then there’s really no benefit in reading it.

And for the vast majority of us, it is going to be OK.

Next articles here will be on the economic fallout, which is likely to be longer and deeper than the health impact, but was overdue to happen anyway, and on why this horrible event may be a useful wake-up call that might get us started addressing some of the more profound and permanent challenges ahead.

Stay safe, everyone.

RT @brooke: Do I know anyone who HASN’T made a sourdough loaf this weekend and put it on Instagram? Please, for the love of god, announce y…

|

mkalus

shared this story

from |

Do I know anyone who HASN’T made a sourdough loaf this weekend and put it on Instagram? Please, for the love of god, announce yourself.

internetofshit

on Monday, March 30th, 2020 1:37am

internetofshit

on Monday, March 30th, 2020 1:37am1293 likes, 49 retweets

We’re not going back to normal

| mkalus shared this story . |

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

We all want things to go back to normal quickly. But what most of us have probably not yet realized—yet will soon—is that things won’t go back to normal after a few weeks, or even a few months. Some things never will.

It’s now widely agreed (even by Britain, finally) that every country needs to “flatten the curve”: impose social distancing to slow the spread of the virus so that the number of people sick at once doesn’t cause the health-care system to collapse, as it is threatening to do in Italy right now. That means the pandemic needs to last, at a low level, until either enough people have had Covid-19 to leave most immune (assuming immunity lasts for years, which we don’t know) or there’s a vaccine.

How long would that take, and how draconian do social restrictions need to be? Yesterday President Donald Trump, announcing new guidelines such as a 10-person limit on gatherings, said that “with several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly.” In China, six weeks of lockdown are beginning to ease now that new cases have fallen to a trickle.

But it won’t end there. As long as someone in the world has the virus, breakouts can and will keep recurring without stringent controls to contain them. In a report yesterday (pdf), researchers at Imperial College London proposed a way of doing this: impose more extreme social distancing measures every time admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) start to spike, and relax them each time admissions fall. Here’s how that looks in a graph.

The orange line is ICU admissions. Each time they rise above a threshold—say, 100 per week—the country would close all schools and most universities and adopt social distancing. When they drop below 50, those measures would be lifted, but people with symptoms or whose family members have symptoms would still be confined at home.

What counts as “social distancing”? The researchers define it as “All households reduce contact outside household, school or workplace by 75%.” That doesn’t mean you get to go out with your friends once a week instead of four times. It means everyone does everything they can to minimize social contact, and overall, the number of contacts falls by 75%.

Under this model, the researchers conclude, social distancing and school closures would need to be in force some two-thirds of the time—roughly two months on and one month off—until a vaccine is available, which will take at least 18 months (if it works at all). They note that the results are “qualitatively similar for the US.”

Eighteen months!? Surely there must be other solutions. Why not just build more ICUs and treat more people at once, for example?

Well, in the researchers’ model, that didn’t solve the problem. Without social distancing of the whole population, they found, even the best mitigation strategy—which means isolation or quarantine of the sick, the old, and those who have been exposed, plus school closures—would still lead to a surge of critically ill people eight times bigger than the US or UK system can cope with. (That’s the lowest, blue curve in the graph below; the flat red line is the current number of ICU beds.) Even if you set factories to churn out beds and ventilators and all the other facilities and supplies, you’d still need far more nurses and doctors to take care of everyone.

How about imposing restrictions for just one batch of five months or so? No good—once measures are lifted, the pandemic breaks out all over again, only this time it’s in winter, the worst time for overstretched health-care systems.

And what if we decided to be brutal: set the threshold number of ICU admissions for triggering social distancing much higher, accepting that many more patients would die? Turns out it makes little difference. Even in the least restrictive of the Imperial College scenarios, we’re shut in more than half the time.

This isn’t a temporary disruption. It’s the start of a completely different way of life.

Living in a state of pandemic

In the short term, this will be hugely damaging to businesses that rely on people coming together in large numbers: restaurants, cafes, bars, nightclubs, gyms, hotels, theaters, cinemas, art galleries, shopping malls, craft fairs, museums, musicians and other performers, sporting venues (and sports teams), conference venues (and conference producers), cruise lines, airlines, public transportation, private schools, day-care centers. That’s to say nothing of the stresses on parents thrust into home-schooling their kids, people trying to care for elderly relatives without exposing them to the virus, people trapped in abusive relationships, and anyone without a financial cushion to deal with swings in income.

There’ll be some adaptation, of course: gyms could start selling home equipment and online training sessions, for example. We’ll see an explosion of new services in what’s already been dubbed the “shut-in economy.” One can also wax hopeful about the way some habits might change—less carbon-burning travel, more local supply chains, more walking and biking.

But the disruption to many, many businesses and livelihoods will be impossible to manage. And the shut-in lifestyle just isn’t sustainable for such long periods.

So how can we live in this new world? Part of the answer—hopefully—will be better health-care systems, with pandemic response units that can move quickly to identify and contain outbreaks before they start to spread, and the ability to quickly ramp up production of medical equipment, testing kits, and drugs. Those will be too late to stop Covid-19, but they’ll help with future pandemics.

In the near term, we’ll probably find awkward compromises that allow us to retain some semblance of a social life. Maybe movie theaters will take out half their seats, meetings will be held in larger rooms with spaced-out chairs, and gyms will require you to book workouts ahead of time so they don’t get crowded.

Ultimately, however, I predict that we’ll restore the ability to socialize safely by developing more sophisticated ways to identify who is a disease risk and who isn’t, and discriminating—legally—against those who are.

We can see harbingers of this in the measures some countries are taking today. Israel is going to use the cell-phone location data with which its intelligence services track terrorists to trace people who’ve been in touch with known carriers of the virus. Singapore does exhaustive contact tracing and publishes detailed data on each known case, all but identifying people by name.

We don’t know exactly what this new future looks like, of course. But one can imagine a world in which, to get on a flight, perhaps you’ll have to be signed up to a service that tracks your movements via your phone. The airline wouldn’t be able to see where you’d gone, but it would get an alert if you’d been close to known infected people or disease hot spots. There’d be similar requirements at the entrance to large venues, government buildings, or public transport hubs. There would be temperature scanners everywhere, and your workplace might demand you wear a monitor that tracks your temperature or other vital signs. Where nightclubs ask for proof of age, in future they might ask for proof of immunity—an identity card or some kind of digital verification via your phone, showing you’ve already recovered from or been vaccinated against the latest virus strains.

We’ll adapt to and accept such measures, much as we’ve adapted to increasingly stringent airport security screenings in the wake of terrorist attacks. The intrusive surveillance will be considered a small price to pay for the basic freedom to be with other people.

As usual, however, the true cost will be borne by the poorest and weakest. People with less access to health care, or who live in more disease-prone areas, will now also be more frequently shut out of places and opportunities open to everyone else. Gig workers—from drivers to plumbers to freelance yoga instructors—will see their jobs become even more precarious. Immigrants, refugees, the undocumented, and ex-convicts will face yet another obstacle to gaining a foothold in society.

Moreover, unless there are strict rules on how someone’s risk for disease is assessed, governments or companies could choose any criteria—you’re high-risk if you earn less than $50,000 a year, are in a family of more than six people, and live in certain parts of the country, for example. That creates scope for algorithmic bias and hidden discrimination, as happened last year with an algorithm used by US health insurers that turned out to inadvertently favor white people.

The world has changed many times, and it is changing again. All of us will have to adapt to a new way of living, working, and forging relationships. But as with all change, there will be some who lose more than most, and they will be the ones who have lost far too much already. The best we can hope for is that the depth of this crisis will finally force countries—the US, in particular—to fix the yawning social inequities that make large swaths of their populations so intensely vulnerable.

Helping Zoom

[This is the third of four posts. The last of those, Zoom’s new privacy policy, visits the company’s positive response to input such as mine here. So you might want to start with that post (because it’s the latest) and look at the other three, including this one, after that.]

I really don’t want to bust Zoom. No tech company on Earth is doing more to keep civilization working at a time when it could so easily fall apart. Zoom does that by providing an exceptionally solid, reliable, friendly, flexible, useful (and even fun!) way for people to be present with each other, regardless of distance. No wonder Zoom is now to conferencing what Google is to search. Meaning: it’s a verb. Case in point: between the last sentence and this one, a friend here in town sent me an email that began with this:

That’s a screen shot.

But Zoom also has problems, and I’ve spent two posts, so far, busting them for one of those problems: their apparent lack of commitment to personal privacy:

With this third post, I’d like to turn that around.

I’ll start with the email I got yesterday from a person at a company engaged by Zoom for (seems to me) reputation management, asking me to update my posts based on the “facts” (his word) in this statement:

Zoom takes its users’ privacy extremely seriously, and does not mine user data or sell user data of any kind to anyone. Like most software companies, we use third-party advertising service providers (like Google) for marketing purposes: to deliver tailored ads to our users about Zoom products the users may find interesting. (For example, if you visit our website, later on, depending on your cookie preferences, you may see an ad from Zoom reminding you of all the amazing features that Zoom has to offer). However, this only pertains to your activity on our Zoom.us website. The Zoom services do not contain advertising cookies. No data regarding user activity on the Zoom platform – including video, audio and chat content – is ever used for advertising purposes. If you do not want to receive targeted ads about Zoom, simply click the “Cookie Preferences” link at the bottom of any page on the zoom.us site and adjust the slider to ‘Required Cookies.’

I don’t think this squares with what Zoom says in the “Does Zoom sell Personal Data?” section of its privacy policy (which I unpacked in my first post, and that Forbes, Consumer Reports and others have also flagged as problematic)—or with the choices provided in Zoom’s cookie settings, which list 70 (by my count) third parties whose involvement you can opt into or out of (by a set of options I unpacked in my second post). The logos in the image above are just 16 of those 70 parties, some of which include more than one domain.

Also, if all the ads shown to users are just “about Zoom,” why are those other companies in the picture at all? Specifically, under “About Cookies on This Site,” the slider is defaulted to allow all “functional cookies” and “advertising cookies,” the latter of which are “used by advertising companies to serve ads that are relevant to your interests.” Wouldn’t Zoom be in a better position to know your relevant (to Zoom) interests, than all those other companies?

More questions:

- Are those third parties “processors” under GDPR, or “service providers by the CCPAs definition? (I’m not an authority on either, so I’m asking.)