Rolandt

Shared posts

Build tools around workflows, not workflows around tools

SELECT * FROM services WHERE name = 'postgres'

I guess we can rearrange the default web site to-do list, to put the branded jackets and the user conference ahead of the job server and full-text search engine. Some good articles on simplifying the back end by making PostgreSQL do it.

-

System design hack: Postgres is a great pub/sub & job server by Colin Chartier

-

What is SKIP LOCKED for in PostgreSQL 9.5? - 2ndQuadrant | PostgreSQL by Craig Ringer

-

Postgres full-text search is Good Enough! by Rachid Belaid

-

Minimal Viable Search using Postgres by Sheshbabu Chinnakonda

Related

- Per-project Postgres by Jamey Sharp

Bonus links

A new default Referrer-Policy for Chrome: strict-origin-when-cross-origin

This AI generates hilariously realistic startup acquisition announcements

Rene Ritchie: Why Apple Silicon is not ARM

Google’s ‘trust tokens’ are here to take cookies down a peg

‘There is no precedent to this’: How Criteo plans to adapt to Apple’s IDFA privacy update

How we bootstrapped our startup from $400 to $2,750 MRR in 135 days without ads

Web analytics, CCPA and is Google Analytics compliant with CCPA?

Update (Six Months of Data): lessons for growing publisher revenue by removing 3rd party tracking

the golden age of piracy

Highly recommended: Steven Johnson’s new book Enemy of All Mankind, not only for the tale of the pirate Henry Every and the late 17th-century global manhunt for him and his crew, but also for Johnson’s historical contextualization. I loved this bit in particular, about how, as Johnson puts it, “the golden age of piracy coincides almost exactly with the emergence of print culture.”

Every and his descendants had a vibrant media apparatus through which they could broadcast their atrocities: the pamphlets, newspapers, magazines, and books that shaped so much of popular opinion in European and Colonial American cities during that period. Many of the conventions we associate with “tabloid” media — hastily written, often fabricated stories of sensational violence — were first developed to profit off the distance actions of men like Henry Every and the pirates who followed him in the early 1700s. If Every was, in his prime, the descendant of mythic seafaring men like Odysseus, he was also an augur of another kind of larger-than-life figure; the killer that captivates a nation with his outlandish crimes, like John Wayne Gacy, Son of Sam, Charles Manson.

the golden age of piracy was originally published in stating the obvious on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Lies and misinformation

[L]et us also notice something: the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Washington Post, the New Republic, New York, Harper’s, the New York Review of Books, the Financial Times, and the London Times all have paywalls. Breitbart, Fox News, the Daily Wire, the Federalist, the Washington Examiner, InfoWars: free!

[…]

Possibly even worse is the fact that so much academic writing is kept behind vastly more costly paywalls. A white supremacist on YouTube will tell you all about race and IQ but if you want to read a careful scholarly refutation, obtaining a legal PDF from the journal publisher would cost you $14.95, a price nobody in their right mind would pay for one article if they can’t get institutional access.

Nathan J. Robinson, The Truth Is Paywalled But The Lies Are Free (Current Affairs)

I pay monthly for access to The Guardian on my smartphone. I could access it for free, but the advertising annoys me, and I want to support their journalism.

Now that I’ve deactivated my Twitter account, it’s the main place I get access to political news. I don’t use Facebook or Instagram, and I’m well aware of the radical left-wing stance of most people I follow on Mastodon.

For me, the problem is not lies per se, but misinformation. There’s certainly a subset of the population either gullible enough or brainwashed enough to believe untruths. What’s more pernicious is the misinformation spread via social networks, often around the intent of various political actors. I can do without this.

For the last decade or so, I’ve taken at least a month off every year from blogging and social media. What I tend to find is that I revert to a more centrist position after this period, and that I replace a lot of the time I usually spend on social media reading history and non-fiction instead.

The answer to our epidemic of misinformation is not 20th century-style ‘information literacy’ resources. Instead, what we need to give people is a real grounding in Humanities, a range of subjects that at their core contain a critical stance to information that circulates in society.

While the technologies we use are new, our desire to manipulate and misinform one another to suit particular agendas is as old as the hills. Let’s remind ourselves that every problem isn’t caused by technology, nor can it be solved by more technology.

This post is Day 22 of my #100DaysToOffload challenge. Want to get involved? Find out more at 100daystooffload.com

Microsoft's announcement changes the future of learning - here's what you need to know

This article describes "the natural progression to provide an LMS structure that will underpin the informal learning already going on in Teams, supported by content from Microsoft Learn and LinkedIn Learning," while cautioning that the overall impact "won’t be enough to enable the aspects of an advanced learning culture that drive real capability change." Both parts of this are probably true, but where the biggest impact will be will be in corporate learning, as the plan is that Teams will replace the browser as the place where 'work gets done' and hence where learning is most effectively embedded. But let's not forget, Teams is built on Electron, which makes it a cross-platform HTML-CSS-Javascript running on Chromium. In the long run (in my view) it will integrate with the LMS the way a browser does, rather than attempt to replace it.

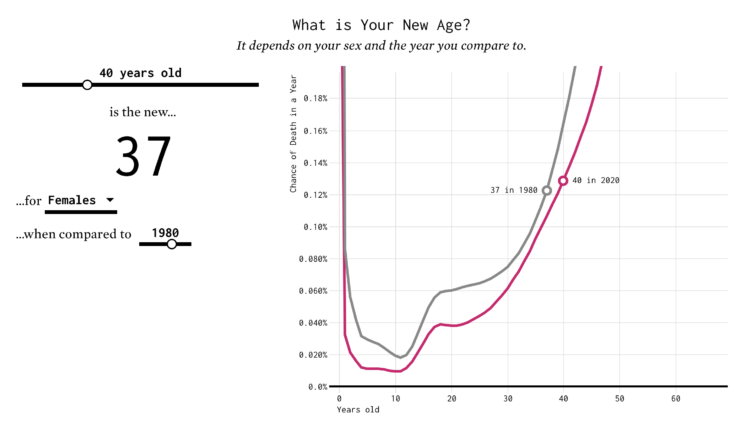

Web: [Direct Link] [This Post]Finding the New Age, for Your Age

You've probably heard the lines about how "40 is the new 30" or "30 is the new 20." What is this based on? I tried to solve the problem using life expectancy data. Your age is the new age. Read More

Twitter Favorites: [minakimes] Every time Zion does a cool thing with JJ I am struck anew by the improbability of living in a moment where two of… https://t.co/82OzN6An1U

Every time Zion does a cool thing with JJ I am struck anew by the improbability of living in a moment where two of… twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Antitrust Politics

The only thing more predictable than members of Congress using hearings to make statements instead of ask questions, and when they do ask questions, usually of the “gotcha” variety, refusing to allow witnesses to answer (even as those witnesses seek to run out the clock), is people watching said hearings and griping about how worthless the whole exercise is.

There was, needless to say, all of the above last Wednesday, when the House Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law held a hearing featuring Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, and Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook. Statements were made, gotcha questions were asked, answers were interrupted, clocks were run out, and there was a whole lot of griping about what a waste of time it all was.

To be sure, it does seem like there must be a better way to hold these hearings, particularly if the goal is to learn something new, but the reality is that genuine inquiry is much more likely to happen without the glare of the media spotlight that inevitably accompanies such a high profile hearing; what that glare will highlight is the politics of the topic in question: what do various politicians and parties actually care about, what do they think that their constituents care about, and how should those affected by said hearings respond.

In that regard last Wednesday’s hearing was a success: partisan priorities were made clear on the politician side, tech’s collective position and impact on society came into view, even as each of the companies at the hearing revealed different strengths and vulnerabilities. This article will examine all of these points, but first a caveat: this post, even more than most on Stratechery, is meant as an analysis of the politics of this hearing in particular, not a statement of values; unless I say so explicitly, I am not necessarily endorsing or condemning any particular line of argument, simply pointing it out.

The Political Effects of Monopoly

Lina Khan, who rose to prominence with her 2017 law review article Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, and who served as counsel for the antitrust subcommittee over the course of the investigation that culminated in Wednesday’s hearings, summarized the New Brandeis Movement of antitrust in 2018:

As the name suggests, this new movement traces its intellectual roots to Justice Louis Brandeis, who served on the Supreme Court between 1916 and 1939. Brandeis was a strong proponent of America’s Madisonian traditions—which aim at a democratic distribution of power and opportunity in the political economy. Early in the twentieth century, Brandeis successfully updated America’s antimonopoly regime, along Madisonian lines, for the industrial era, and his philosophy held sway well into the 1970s. As the ‘New Brandeis School’ gains prominence — even prompting two floor speeches by Senator Orrin Hatch (a Republican from Utah) — it’s worth understanding what this vision of antimonopoly does and does not represent.

While the article is worth reading in full, it is no accident that Khan started with “democracy”:

Brandeis and many of his contemporaries feared that concentration of economic power aids the concentration of political power, and that such private power can itself undermine and overwhelm public government. Dominant corporations wield outsized influence over political processes and outcomes, be it through lobbying, financing elections, staffing government, funding research, or establishing systemic importance that they can leverage. They use these strategies to win favorable policies, further entrenching their dominance.

Brandeis also believed that the structure of our markets and of our economy can determine how much real liberty individuals experiences in their daily lives. Most people’s day-to-day experience of power comes not from interacting with public officials, but through relationships in their economic lives — negotiating pay with an employer, for example, or wrangling the terms of business with a trading partner. Brandeis feared that autocratic structures in the commercial sphere — such as when one or a few private corporations call all the shots — can preclude the experience of liberty, threatening democracy in our civic sphere.

Chairman David Cicilline, in the conclusion to his opening statement, made a clear gesture to the New Brandeis Movement:1

Because concentrated economic power also leads to concentrated political power, this investigation also goes to the heart of whether we as a people govern ourselves, or whether we let ourselves be governed by private monopolies. American democracy has always been at war against monopoly power. Throughout our history, we’ve recognized that concentrated markets and concentrated political control are incompatible with democratic ideals. When the American people confronted monopolies in the past, be it the railroads or the oil tycoons or AT&T and Microsoft, we took action to ensure no private corporation controls our economy or our democracy.

What was notable to me is that in the hearing Cicilline and the other Democrats never really focused on this point; the rest of Cicilline’s opening statement, and much of the Democratic questioning, focused on what they perceived as illegal activities that caused economic harm, without necessarily tying that to political harm. Again, that’s not to say they were ignoring the linkage, but it wasn’t a priority.

What made this stand out was that Republicans were focused almost entirely on the politics of monopoly, specifically their contention that large platforms, particularly Google and Facebook (and Twitter), were censoring conservative viewpoints and working to elect Democratic candidates to office, particularly the presidency, and that this was a problem because of their dominance. Leave aside, if you can, your opinion about the veracity of these complaints (and remember my note at the beginning about focusing on analysis): while the Republicans were certainly not endorsing the “New Brandeis School” — Ranking Member James Sensenbrenner in particular took care to highlight support for the consumer welfare standard, also known as the “Chicago School” — their concern with the size of tech companies had nothing to do with economic effects and everything to do with political effects. It was a striking contrast.

Begging the Question

One of the more humorous lines of questioning, at least for language nerds, came courtesy of Republican Representative Matt Gaetz:

I want to talk about Search because that’s an area where I know Google has real market dominance. On December 11th, you testified to the Judiciary Committee, and in response to a question from my colleague Zoe Lofgren about Search, you said, “We don’t manually intervene on any particular search result.” But leaked memos obtained by The Daily Caller show that that isn’t true. In fact, those memos were altered December 3rd, just a week before your testimony. And they describe a deceptive news blacklist and a process for developing that blacklist approved by Ben Gomes, who leads Search with your company. And also something called a fringe ranking, which seems to beg the question, who gets to decide what’s fringe?

And in your answer, you said to Ms. Lofgren that there is no manual intervention of search. That was your testimony, but … And now I’m going to cite specifically from this memo from The Daily Caller. It says that the … I’m sorry, that The Daily Caller obtained from your company. It says, “The beginning of the workflow starts when a website is placed on a watch list.” It continues, “This watch list is maintained and stored by Ares with access restricted to policy and enforcement specialists.” Sort of does beg the question who these enforcement specialists are?

First off, note that this is an example of Republicans linking dominance to concerns about censorship. The point about language, though, is that Gaetz is using the phrase “begs the question” incorrectly; I know this, because I used to make the same mistake, until a reader graciously corrected me a couple of years ago. What Gaetz meant to say was “raises the question”; “begs the question”, on the other hand, to use Wikipedia’s definition, is:

An informal fallacy that occurs when an argument’s premises assume the truth of the conclusion, instead of supporting it. It is a type of circular reasoning: an argument that requires that the desired conclusion be true. This often occurs in an indirect way such that the fallacy’s presence is hidden, or at least not easily apparent.

For an example of this logical fallacy at work, look no further than this antitrust hearing, and Cicilline’s concluding statement:

Today, we had the opportunity to hear from the decision makers at four of the most powerful companies in the world. This hearing has made one fact clear to me. These companies, as exist today, have monopoly power. Some need to be broken up, all need to be properly regulated and held accountable.

If I may nitpick, this is obviously not true — Cicilline had decided well before this hearing that these companies have monopoly power. The problem is that a huge number of questions in the hearing took it as a given that these companies were monopolies, and proceeded to find rather common business practices as being major crimes. In other words, they begged the question.

One of the most striking examples of this fallacy — where it is assumed that a company is a monopoly, and therefore its actions are illegal, and because its actions are illegal it is a monopoly — was this exchange between Representative Jamie Raskin and Bezos:

Start with the HBO Max-on-Fire TV question. One of the first things you learn about conducting effective negotiations is that you want to negotiate about more things, not fewer. The reasoning is straightforward: if you are only negotiating about a single variable — in this example, Raskin believes that Amazon and HBO should only negotiate on price — the outcome is zero sum: every cent that Amazon wins is a cent that HBO loses. However, if you are able to introduce more variables, then you might find out that one company cares a lot about price, while the other company cares a lot about promotion (just to make up an example); in that case one company can get a better price and give up a lot of promotional opportunities, while the other can get a worse price and gain a lot of promotional opportunities, and thanks to their differing priorities, both feel like winners. That’s good negotiating!

It also appears to be, at least according to Raskin, illegal, because Amazon is “us[ing its] gatekeeper status role in the streaming device market to promote [its] position as a competitor in the video streaming market with respect to content.” That’s the problem though: there was zero evidence provided that Amazon has a monopolistic position in either streaming devices or video streaming; it was simply taken as fact, which made basic negotiating practices suspect, and evidence that Amazon was a monopoly. Begging the question.

Raskin’s question about Amazon’s acquisition of Ring was an even better example of the fallacy at work; while I don’t really understand why multivariate negotiations would be illegal even if you are a monopoly, there are clear antitrust issues raised by a monopolist acquiring a company for market share. Crucially, though, acquiring a company for market share if you are not a monopolist is not a crime.

It follows, then, that if Amazon had a monopoly in the home automation market, and acquired Ring for market share reasons, that could very well be an antitrust violation, but if they weren’t a monopoly, it would not be. What is critical to note is that you have to establish that Amazon has a monopoly first; only then can you decide if the acquisition was anticompetitive. Raskin, though, begs the question: the fact that Amazon acquired Ring for market share reasons is taken as evidence that Amazon has a monopoly, which then makes the acquisition illegal.

The same problem applied to Raskin’s final two complaints: Alexa defaulting to Amazon Prime Music, and recommending Amazon Basics. Those may be a problem if you first establish that Amazon has a monopoly in the relevant product areas, but it is not itself evidence that Amazon is a monopoly.

I’m focusing on this specific exchange, but the truth is that a combination of vilifying common business practices and begging the question was a consistent theme. Things like market research or copying competitor features or improving products were held up as obvious crimes and evidence of monopoly, when they were often not crimes at all, or only crimes if a monopoly in the relevant market had first been established. That is not to say that the committee’s investigation didn’t produce evidence of illegal anticompetitive actions, but rather that said evidence, such that there was, too often begged the question.

The GOP Bargain

The combination of the Republicans’ focus on the political aspects of antitrust and the tendency of the Democrats to see antitrust crimes even in normal business proceedings produced what was, I think, the most obvious political takeaway for tech companies: the Democrats have made up their minds (that tech is guilty), while the Republicans are willing to cut a deal.

The outline of that deal could not have been more obvious: Republicans are fine with the consumer welfare standard (which, as I noted back in 2016, inherently favors Aggregators) and tech’s business practices, as long as tech companies don’t “censor”; the alternating format of Congressional hearings placed these demands in direct contrast to Democratic assumptions of guilt. To put it in explicit terms: “We, Republicans, are your friends in Washington, but if you want us to defend you from the Democrats, you need to stop censoring conservatives.”

Again, it doesn’t matter that conservative websites tend to do particularly well on social media, or that the destruction of the media business model helped lay the groundwork for President Trump’s rise; Republicans expect that tech companies — by which they mostly mean Google and Facebook (and Twitter) — err on the side of not censoring or checking conservative content if they want help in Washington, because that help is not coming from the Democrats.

Tech’s United Front

Something that stood out from the four CEOs’ opening statements, and the general tenor of their defenses, was their insistence that they supported small-and-medium sized businesses.

Bezos:

20 years ago, we made the decision to invite other sellers to sell in our store, to share the same valuable real estate we’ve spent billions to build, market, and maintain. We believe that combining the strengths of Amazon Store with the vast selection of products offered by third parties would be a better experience for customers, and that the growing pie of revenue and profits would be big enough for all. We were betting that it was not a zero sum game. Fortunately, we were right. There are now, 1.7 million small-and-medium-sized businesses selling on Amazon.

Pichai:

One way we contribute is by building helpful products. Research found that free services like search, Gmail, maps, and photos provide thousands of dollars a year in value to the average American. And many are small businesses using our digital tools to grow. Stone Dimensions, a family owned stone company in Pewaukee, Wisconsin uses Google My Business to draw more customers. Gil’s appliances, a family owned appliance store in Bristol, Rhode Island credits Google analytics with helping them reach customers online during the pandemic. Nearly one third of small business owners say that without digital tools, they would have had to close all or part of their business during COVID.

Cook:

What does motivate us is that timeless drive to build new things that we’re proud to show our users. We focus relentlessly on those innovations, on deepening core principles like privacy and security and on creating new features. In 2008, we introduced a new feature of the iPhone called the App Store launched with 500 apps, which seemed like a lot at the time, the App Store provided a safe and trusted way for users to get more out of their phone. We knew the distribution options for software developers at the time didn’t work well, brick-and-mortar stores charged high fees and have limited reach, physical media like CDs had to be shipped and were hard to update. From the beginning, the App Store was a revolutionary alternative. App Store developers set prices for their apps and never pay for shelf space.2

Zuckerberg:

We’ve built services that billions of people find useful. I’m proud that we’ve given people who’ve never had a voice before the opportunity to be heard, and given small businesses access to tools that only the largest players used to have.

This shared focus was notable for two reasons, one specific to these hearings, and one that tells a broader story about how the Internet is changing the world.

First off, probably the most obvious connective thread in the hearing was concern about these companies creating platforms and then favoring themselves unfairly. Amazon, for example, is accused of using data about third party sellers to inform its private-label goods strategy (and data from AWS); Google is accused of using data about search to keep users on its pages; Apple is accused of using its control of the App Store to favor its own apps; and Facebook is accused of using data about app usage to drive its acquisition strategy. What each of these companies is arguing is that focusing on a couple of disgruntled companies is to miss the larger picture, wherein these companies created those opportunities in the first place, and for exponentially more companies than those the Committee may have heard from.

What is particularly interesting, though, is that to the extent these companies are right it foretells both a new kind of economy and a new kind of political alignment. Zuckerberg’s summary was the shortest yet most explicit, perhaps because Facebook is the best example of this phenomenon; I wrote in Apple and Facebook:

This explains why the news about large CPG companies boycotting Facebook is, from a financial perspective, simply not a big deal. Unilever’s $11.8 million in U.S. ad spend, to take one example, is replaced with the same automated efficiency that Facebook’s timeline ensures you never run out of content. Moreover, while Facebook loses some top-line revenue — in an auction-based system, less demand corresponds to lower prices — the companies that are the most likely to take advantage of those lower prices are those that would not exist without Facebook, like the direct-to-consumer companies trying to steal customers from massive conglomerates like Unilever.

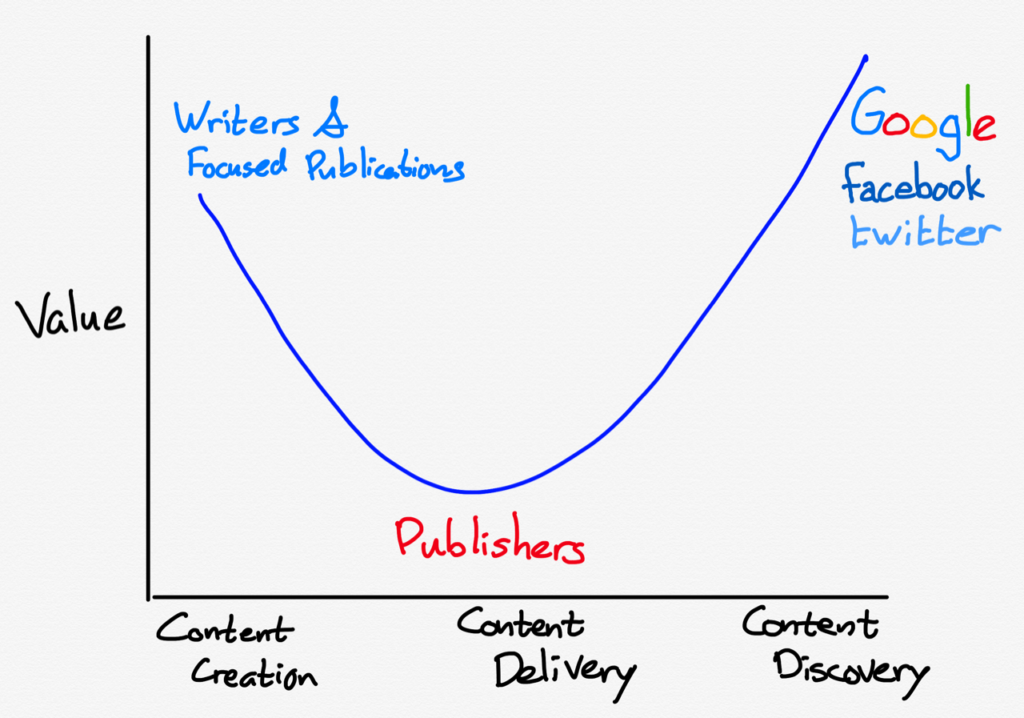

The Internet is best illustrated by the smiling curve, in which value flows to large Aggregators and Platforms on one side, and small businesses built with Internet assumptions about addressable markets (and Internet cost structures) on the other side, while the folks in the middle that built their businesses on owning distribution in a world of scarcity are increasingly obsolete.

That is why you regularly see strange political bedfellows, like Uber and drivers and riders versus taxi companies and politicians, or Airbnb and hosts versus hotels and, well, politicians, or these companies and their small business bases against newspapers, retailers, cross-platform software businesses, vertical aggregators and yes, politicians. Zuckerberg made this point on behalf of the tech industry as a whole:

We’re here to talk about online platforms, but I think the true nature of competition is much broader. When Google bought YouTube, they could compete against the dominant player in video, which was the cable industry. When Amazon bought Whole Foods, they could compete against Kroger’s and Walmart. When Facebook bought WhatsApp, we could compete against telcos who used to charge 10 cents a text message, but not anymore. Now people can watch video, get groceries delivered, and send private messages for free. That’s competition. New companies are created all the time, all over the world. And history shows that if we don’t keep innovating, someone will replace every company here today.

Companies that used to be big, at least before the big tech companies came along, have the most to lose from tech, but just because they are ill-equipped to compete does not mean they are representative of all businesses, particularly companies that only exist because these platforms and Aggregators exist.3

Tech’s Differing Prospects

That noted, just because there were similarities in their messaging does not mean that each tech company has similar prospects as far as potential regulation is concerned. From the companies that should be the least concerned to the most:

Apple: It was obvious that the committee only invited Apple because they wanted to say that they invited all of the large consumer tech CEOs. The questions for Cook were hilariously uninformed about the App Store, making it easy for Apple’s CEO to run out the clock (often without any interruption). This was certainly disappointing given that many of Apple’s policies are clearly anticompetitive (which, as I noted above, is different than being illegal), but for now the takeaway is that Congress doesn’t know and doesn’t care.

Facebook: Facebook was probably the biggest beneficiary of Democrats not focusing on political harm relative to economic harm; as I noted last year in Tech and Antitrust, there really isn’t much about the company’s business practices (post acquisitions) that are anticompetitive. There was an interesting back-and-forth about Facebook’s discriminatory willingness to deal as far as access to their friend graph is concerned, but for that to be illegal you have to first establish that Facebook is a monopoly.

On this point I thought the Committee’s questioning was frequently unfair: the fact that social networks that existed when Facebook was founded no longer do (MySpace, Friendster, etc.) was taken as evidence that Facebook is a monopoly, with zero acknowledgment of the rise of Snapchat, TikTok, iMessage, etc. Similarly, Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram was discussed as if it happened today, when Instagram has over a billion users, as opposed to 2012, when it had 30 million. To be sure, some saw the anticompetitive angle of that purchase at the time, but many more mocked the price; at a minimum we can all agree that judging decisions made in 2012 according to the facts of 2020 isn’t necessarily just.

Amazon: Amazon seemed to attract the most in-depth scrutiny from the committee (perhaps because of Kahn), and while the biggest focus was on the 3rd-party marketplace and Amazon’s private-label strategy, there was a clear attempt across multiple questioners to make the case that Amazon creates “innovation kill zones”, as Representative Joe Neguse put it, across all of its product lines. There was clearly a target on Bezos.

At the same time, as Bezos regularly noted, it is not clear in what markets Amazon has a monopoly, and if it is not a monopoly, a lot of the behavior lawmakers were objecting to is not illegal (and, as I noted above, may not be illegal regardless). Bezos also made the point that only the military has a higher approval rating than Amazon, and when it comes to politics, that still matters.

Google: I think that Google is in trouble. The company received the second greatest amount of specificity in its questions as far as competition topics go — Representative Pramila Jayapal’s questions about ad exchanges was particularly well-done, especially given the constraints of the format — but more importantly, at least far as the politics of this hearing is concerned, was revealed to have no friends.

Specifically, the price of the company pulling out of Project Maven and the Pentagon’s JEDI project because of concerns about collaborating with the U.S. military4 is that the GOP deal I detailed above is not on the table: Republicans pushed Pichai on not just censorship and election interference but also its refusal to support the military repeatedly, and it seems clear than if and when an antitrust case is brought against the company, it will have few defenders. That is a particularly big problem for Google because the antitrust case against the company is by far the most straightforward.

As I wrote last week before the hearing, I am glad that it occurred. Figuring out how to regulate tech companies — particularly Aggregators, that base their power on consumer welfare — will require new approaches, and probably new laws. Moreover, any such regulations will necessitate difficult trade-offs between competition, privacy, national security, etc. (I was grateful that Representative Kelly Armstrong highlighted how GDPR made big tech companies stronger), which again means that Congress is best situated to decide what tradeoffs we should make.

To that end, I think the hearing was more successful than the format made it seem: there is more clarity about both Democratic and Republican priorities, as well as potential new divisions driven by technology generally, and a finer-grained understanding of how individual companies raise different concerns specifically. No, this wasn’t “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”, but then again that movie was made by a studio about to be convicted of acting anti-competitively.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

- That is Khan sitting behind Cicilline

- Yes, Cook is pretending like the Internet never existed as a distribution channel

- Again, this is not to say that regulation isn’t necessary — see A Framework for Regulating Competition on the Internet

- Incidentally, I think the real reason that Google pulled out of the JEDI project is that Google Cloud was not competitive with Azure and AWS; citing ethical concerns was a misguided attempt to claim a strategy credit that is coming back to bite the company in a major way

Research Educators

Good heavens! For more than 40 years I have been speaking prose without knowing it.

— Moliere

I think I finally know what I’ve been trying to do for the last ten (fifteen, twenty-two…) years, but in order for it to make sense, you first need to know what a research software engineer is. An RSE is someone with a research background whose primary job is to write software; they’re like an astronomer who mostly builds telescopes rather than looking at the stars. The term originated in the UK in 1992; I don’t know when I first heard it, but when I did I realized that the best way to describe Software Carpentry’s mission was “teaching the basics of research software engineering”.

Since 2014, though, I have spent most of my time teaching people how to teach rather than how to program. Some of those people have been Python or JavaScript developers working in industry, but most have been researchers who teach in contexts ranging from weekend workshops to full-semester courses. They are end-user teachers, but I now think they’re a distinct enough subset to deserve their own label.

By analogy with research software engineers, I propose calling these people research educators (REs). An RE combines in-depth understanding of research with expertise in education and training. Just as RSEs primarily write software to support research, REs primarily create and deliver lessons for their fellow scholars. They almost certainly have a graduate degree in some research-intensive discipline; they might have a Certificate of Higher Education, but most REs are faculty who have somehow found themselves in teaching-intensive roles without being trained for it.

The Carpentries’ instructor training and offshoots like RStudio’s instructor training program are to research educators what the Carpentries’ workshops are to research software engineering. Call it the first step, or the bare minimum it’s reasonable to expect everyone to know—either way, they’re meant to be starting points rather than goalposts.

Is Charging Your Phone All Day Really That Bad?

If you’re unsure whether there’s a “right” way to charge your phone—or whether charging it too long, too often, or too fast can damage the battery—you’re not alone. I’ve been writing about phones and tech since 2011, and before that I was an iPhone sales specialist at an Apple Store. Even with that experience under my belt, it has never been totally clear to me if being careful about how often I recharge my phone actually extends the life of the battery enough to make a difference, or if it’s just another hassle in a world with far too many of them.

threeway insanity

Matt Levine, in his (excellent) Money Stuff newsletter/column, on the insanity that is the Microsoft / TikTok / Trump threeway.

Historically when the president of the United States says something, that has represented a policy of his administration, but when President Trump says something, that just represents the crankish views of a guy who watches way too much television, and people are continually forced to treat the latter like the former. “It is completely unorthodox for a President to propose that the U.S. take a cut of a business deal, especially a deal that he has orchestrated. The idea also is probably illegal and unethical,” says some poor law professor who was called to comment on this dumb, dumb stuff. Imagine calling a law professor to comment on your uncle’s drunken rants at Thanksgiving. “Uncle Don, I have a law professor on the line and he tells me that your proposal is illegal and unprecedented,” you say, as though Uncle Don might care, as though “illegal” is a relevant category to apply to his unserious mumbling. Though also he is the president so it may happen?

As if we needed another reminder that we are living in the upsidedown.

threeway insanity was originally published in stating the obvious on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Tough Decisions Create Clean Homepages

If you ever see a clean and simple community homepage, you can bet they had to make some difficult decisions to get there.

A cluttered homepage is typically the result of a failure to get people aligned on who the community is for, what its purpose is, and what members are meant to do.

If you can’t prioritise (or agree on) what should be featured on the homepage, the obvious solution is everything, i.e. put everything on the homepage and hope members like some of it.

If you want a homepage like Claris, Atlassian, or Temenos, you’re probably going to have to engage colleagues and make some tricky decisions.

Long Links

Back in early July I posted ten links to long-form pieces that I’d had a chance to enjoy because of not having one of those nasty “full-time-job” things. I see that the browser tabs are bulking up again, so here we go. Just like last time, people with anything resembling a “life” probably don’t have time for all of them, but if a few pick a juicy-looking essay to enjoy, that’ll have made it worthwhile.

The Truth Is Paywalled But The Lies Are Free by Nathan J. Robinson. I think we’ve all sort of realized that the assertion in the title is true. Robinson doesn’t lay out much in the way of solutions but does a great job of highlighting the problem. I dug into this this myself last year in Subscription Friction. It’s a super-important subject and needs more study.

Like many, I’ve picked up a new quarantine-time activity — in my case, Afro-Cuban drumming lessons. I’ve been studying West-African drumming for many years, but this is a different thing. Afro-Cuban is normally done on a pair of conga drums as opposed to djembé and dunum. At the center of the thing is the almighty Clave rhythm. In The Rhythm that Conquered the World: What Makes a “Good” Rhythm Good? Godfried Toussaint of Harvard dives deep on the “clave son” flavor (which is sort of the Bo Diddly beat with the measures flipped, and with variations) and has fun with math and music! I personally find the “rumba clave” variation just absolutely bewitching, when you can get it right. For more on this infinitely-deep rabbit hole, check out Wikipedia on Songo and Tumbao.

There’s a new insult being flung about in the Left’s internecine polemics: “Class Reductionist”. A class reductionist is one who might argue that while oppression by race and gender and so on are real and must be struggled against, the most important thing to work on right now is arranging that everyone has enough money to live in dignity. There is some conflict with “intersectional” thinking, which argues that the the struggles against poverty and sexism and racism and LGBTQ oppression aren’t distinct, they’re just one struggle. In some respects, though, the two are in harmony: A Black trans woman is way more likely on average, to be broke. In How calling someone a "class reductionist" became a lefty insult, Asad Haider takes on the subject in detail and at length and says what seem to me a lot of really smart things. Confession: I’m sort of a class reductionist.

In The New Yorker, Why America Feels Like a Post-Soviet State offers that rare thing, a new perspective on 2020’s troubles. By Masha Gessen, who knows whereof they speak.

As anti-monopoly energy starts to surge politically around the world, it’s important to drill down on specifics. It’s gotten to the point where I hesitate to point fingers at Amazon because I actually think the Google and Facebook monopolies need more urgent attention, but since details matter, here’s Amazon’s Monopoly Tollbooth, which tries to assemble facts and figures on whether and how the Amazon retail operation has a monopoly smell. And also on a related but distinct subject: The Harmful Impact of Audible Exclusive Audiobooks. The latter is open to criticism as being the whining of a losing competitor. But when you start to hear that a lot, you may be hearing evidence of monopoly.

In “Hurting People At Scale”, Ryan Mac and Craig Silverman dig hard into Facebook employee culture and controversy. I think this is important because the arguments Facebookers are having with each other are ones we need to be having at a wider scale in society.

Related: A possibly new idea: “Technology unions” could be unions of conscience for Big Tech, by Martin Skladany. It’s pretty simple: High-tech knowledge workers are well-paid and well-cared-for and hardly need traditional unions for traditional reasons. But they’re progressive, angry, and would like to work together. Maybe a new kind of “union”?

Most people reading this will know that I’m an environmentalist generally, a radical on the Climate Emergency specifically, and particularly irritated about the TransMountain (“TMX”) pipeline they’re trying to run through my hometown to ship some of the world’s dirtiest fossil fuels and facilitate exhausting their (high) carbon load into the atmosphere. Thus I’m cheered to read about any and all obstacles in TransMountain’s way, most recently having trouble finding insurers.

Also on the energy file, many have probably heard something about the arrest of the Ohio House of Representatives Speaker Larry Householder on corruption charges. An FBI investigation shows Ohio’s abysmal energy law was fueled by corruption, by Leah C. Stokes, has the goods, big-time. This is corruption on such a huge blatant scale that it feels cartoonish, with a highly-directed purpose: Directing public money into stinky bailouts of stinky dirty-energy companies. When the time has come that you have to bribe the governments of entire U.S. States to keep the traditional energy ecosystem ticking over, I’d say the take-away is obvious.

Finally, some good ol’ fashioned leftist theory. Recently, a few people out on the right (e.g. Tucker Carlson) have been saying things that, while they retain that Trumpkin stench, flame away at inequality and monopoly in a way that seems sort of, well, left-wing. It sounds implausible that Fox-head thinking could ever wear the “progressive” label, thus Mike Konczal’s The Populist Right Will Fail to Help Workers or Outflank the Left (Tl;dr: “Pfui!”) is useful.

Apple product launches leaked

Take them with a grain of salt:

- August 19: new iMac, AirPods Studio, HomePod 2 and HomePod Mini

- September 8: iPhone 12 line, iPad, Apple Watch Series 6 and AirTags

- October 27: Apple Silicon MacBook and MacBook Pro 13", iPad Pro and Apple TV 4K

New York Is My Kind of Town

Downtown 81 is a rare snapshot of an ultra-hip subculture of post-punk era Manhattan, starring Basquiat.

(via Julie)

Google’s proposed ‘trust tokens’ to replace third-party tracking cookies

Several browsers, including Mozilla Firefox and Apple Safari, have taken aim at third-party tracking cookies on the web. Measures taken by both hope to cut down on tracking by blocking these cookies.

Google has been a little slower on the uptake with its own Chrome browser — widely considered the most popular based on market share. However, part of Google’s ‘phased’ approach to moving away from third-party tracking cookies was introducing new technology to replace them.

Now, one of those alternatives, called ‘trust tokens,’ has arrived for developers to test. Unlike cookies, trust tokens can authenticate a user without needing to know their identity. That should mean these tokens won’t be able to track users across websites since, theoretically, they’re all the same.

However, the trust tokens could still allow websites to show advertisers that actual users — not robots — visit their site or click their ads. Further, an explainer posted to GitHub suggests websites could issue multiple different kinds of trust tokens.

Along with these changes, Google announced it would roll out a tweak to the ‘Why this ad’ button that lets users view why an ad was targeted at them. The new ‘About this ad’ label provides the advertiser’s verified name, so it now lets users see which companies target them. The label will also make it more clear how Google collects personal data for ads.

These new labels will arrive toward the end of the year.

Along with that, Google announced a new extension for Chrome called ‘Ads Transparency Spotlight.’ Currently in alpha, it should offer information about all the ads a user sees online. Users will be able to see details about ads on a webpage, why that page shows ads and a list of companies and services with a presence on the page. That includes website analytics and content delivery networks.

For now, none of this likely means anything for the average users. Hopefully going forward, this leads to more transparency around tracking and ads, more user control over these things, and better ads overall.

The post Google’s proposed ‘trust tokens’ to replace third-party tracking cookies appeared first on MobileSyrup.

“Software as a hostage” is a good way to formul...

“Software as a hostage” is a good way to formulate what is wrong with SaaS as part of the tethered economy.

Our CEO just referred to SaaS as “Software as a hostage” and I think that’s pretty spot on.

https://chaos.social/@xpac/104625096400123456

Downtown from Above (2)

We looked at a similar angle of Downtown in a 2002 image. This is all the way back to 1987, and the ‘after’ shot was taken in 2018 from the Global TV helicopter by Trish Jewison.

Thirty three years ago Downtown South (to the east of Granville Street) was still all low-rise, mostly commercial buildings, that had replaced the residential neighbourhood that developed from the early 1900s. We’ve seen many posts that show how that area has been transformed in recent years. In the 1986 census, just before the photo was taken, there were 37,000 people living in the West End (to the west of Burrard and south of Georgia), and only 5,910 in the whole of the rest of the Downtown peninsula (all the way to Main Street on the right hand edge of the picture). In 2016, in the last census, the West End population had gone up to 47,200, adding 10,000 in 30 years. What was a forest of towers in 1987 had become a slightly thicker forest in 2018. The rest of Downtown had seen over a 1000% increase in 30 years – there were 62,030 people living there. Both areas will have seen more growth since 2016, and the 2021 census should show several thousand more people in both the West End and Downtown.

In 1987 the Expo Lands were pretty much bare, with the exception of the Plaza of Nations pavilions in front of BC Place stadium and what soon became Science World on the eastern end of False Creek. The addition of new residents means there are now more local conveniences. Thirty years ago there were only four supermarkets Downtown, all of them in the West End, and now there are sixteen, with two more being built.

On the south side of False Creek, to the east (right) side of Cambie Bridge, industrial sites and the City’s Works Yard have been transformed into South East False Creek, a new residential neighbourhood, heated from a neighbourhood energy system that extracts the excess heat from the sewer that serves the site. Among the first homes completed here were 1,100 in the Olympic Village for the 2010 Games, but there are now over 5,000 completed homes, with 500 more underway and several sites still to develop. Over 650 of the units are non-market housing; some providing welfare rate homes, and others in housing co-ops.,

0996

Selfportrait (Quarantine)

What a stunning self-portrait by Ingrid Emaga. (You can buy it as a print!)

S13:E1 - How live coding can level up your development (Jesse Weigel)

In this episode, we’re talking about live coding with Jesse Weigel, senior software engineer at Dicks Sporting Goods, and YouTube live streamer for freeCodeCamp. Jesse talks about how he got into live streaming his work, the ways in which live streaming has helped him as a developer, and his advice for folks who want to start their own coding livestream.

Show Links

- AWS Insiders (sponsor)

- DICK'S Sporting Goods

- freeCodeCamp YouTube

- HTML

- Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)

- C++

- JavaScript

- WordPress

- freeCodeCamp

- Codecademy

- Udacity

- Open source

- Git

- GitHub

- Twitch

- Open Broadcaster Software (OBS)

- Gwendolyn Faraday

- Vue.js

- noopkat

- The Matrix

- StarCraft

Jesse Weigel

Jesse Weigel is a senior software engineer at Dick's Sporting Goods who live codes for the freeCodeCamp YouTube channel. He is currently building things with React Native. Jesse loves sharing his coding experiences with other developers, including his struggles and failures, and is happy when he gets a chance to encourage new developers.

The Best Electric Toothbrush

If you find an automated two-minute timer helpful or you need or prefer to brush with a powered assist, upgrading from a manual toothbrush to an electric toothbrush may be worthwhile.

After more than 120 total hours of researching the category, interviewing dental experts, considering nearly every model available, and testing 66 toothbrushes ourselves in hundreds of trials at the bathroom sink, we’ve found that the Oral-B Pro 1000 is the one to get.

Although it has few fancy features compared with the other rechargeable brushes we’ve tested, it offers the most important things that experts recommend—a built-in two-minute timer and access to one of the most extensive lines of replacement brush heads available—at an affordable price.

Urban Growth Downtown: A Thousand Percent in Thirty Years

The guys at Changing Vancouver have one of their ‘big picture’ views of the city this week:

This is all the way back to 1987, and the ‘after’ shot was taken in 2018 from the Global TV helicopter by Trish Jewison.

Thirty three years ago Downtown South (to the east of Granville Street) was still all low-rise, mostly commercial buildings, that had replaced the residential neighbourhood that developed from the early 1900s. We’ve seen many posts that show how that area has been transformed in recent years.

In the 1986 census, just before the photo was taken, there were 37,000 people living in the West End (to the west of Burrard and south of Georgia), and only 5,910 in the whole of the rest of the Downtown peninsula (all the way to Main Street on the right hand edge of the picture).

In 2016, in the last census, the West End population had gone up to 47,200, adding 10,000 in 30 years. What was a forest of towers in 1987 had become a slightly thicker forest in 2018. The rest of Downtown had seen over a 1000% increase in 30 years – there were 62,030 people living there. Both areas will have seen more growth since 2016, and the 2021 census should show several thousand more people in both the West End and Downtown.

Gord Price – The 1987 shot really resonates for me: it was my first year on City Council. In the following 15 years, NPA councils would approve rezonings for seven megaprojects (four on the peninsula) and, notably, Downtown South – the area on the peninsula that has seen the biggest change (and continues to do so).

The ‘Living First’ strategy that came out of the 1980s (generally termed ‘Vancouverism’) was a ‘Grand Bargain’ for its time: we would take pressure off the existing residential areas, primarily the West End, through a 1989 de-facto downzoning (following the one that occurred in the early-1970s that resulted in an end to outright approvals for highrises), and concentrate growth east of Granville and north of Robson. In return for stability in the existing residential area, growth would be accelerated in the rezoned commercial/industrial parts of the map. Highrises would be back, now marketed as condos, in a big way. That’s the ‘bargain’ – illustrated so vividly above.

I suspect everyone on Council and at City Hall would have nonetheless been amazed at the prospect of a thousand percent increase occurring so quickly. And yet, it did the job: the West End remained a lower-middle-income neighbourhood, where rents were above the regional average and incomes of the renters (over 80 percent of the residents) were below. (Most made up the difference by not having cars.)

There was effectively no change in the character of the community. Even today, one can walk most of the streets in the interior of the West End and have difficulty finding any buildings constructed after 2000. It is still the arrival city for immigrants and students (that’s why the Robson/Denman area is a ‘Little Korea’ of restaurants) and lower-middle-income renters. It is still able to accommodate new highrises on West Davie and a few other blocks under the recent West End plan without affecting the stability, physical or economic, of most of the district.

Of course, some people will still be under the impression that growth is ‘out of control’ and rents unaffordable, especially when noting the development proposals for the peripheral blocks between Thurlow and Burrard, and Robson and Georgia. Likewise with the rents in new buildings.

‘New’, by definition, is more expensive than depreciated ‘old.’ However, the argument that new development should be rejected because of gentrification could have been used in the 1960s to prevent the development of the West End as we know it today, arguably now an urban miracle of affordable housing, given its location. That anti-growth argument was in fact used in the 1970s – filtered through Jane Jacobs’s writing – to successfully end the highrise era in Kitsilano. Seven of the last them can be seen on the slopes below 4th. In fact, no residential highrises would be built in anywhere in Vancouver from the early 70s to the late 80s, save for a handful of super-expensive ones along the waterfront.

Today, growth in most of the West End is practically sclerotic, though residents might not agree. Their perception is based more on the rate of change than the actual change. If not much has happened on your block over a decade, then any change in scale is immediately impactful in a way that would not even be noticed a few blocks away in a higher growth area. Lesson: the slower the rate of change, the more perceived it is,

Now that most of the downtown peninsula has been built out (with only a few blocks left in places like the ‘Chandelier District’), the peninsula will now have few internal levers left to pull to take the growth pressure off. (And maybe in a post-pandemic world, it won’t be necessary for awhile.) But that means the pressure will eventually increase on land prices, rents and leases once scarcity is induced, unless there is a drastic change in the zoning to allow for the redevelopment of previous eras of housing stock – notably the low-rise wooden walkups that constitute such a critical mass of affordable housing.

So chances are an aerial shot of the peninsula taken 30 years from now won’t look all that much different in Changing Vancouver than the 2018 one in this week’s issue.

Urban Growth Downtown: A Thousand Percent in Thirty Years

Rolandtk

|

mkalus

shared this story

from |

The guys at Changing Vancouver have one of their ‘big picture’ views of the city this week:

This is all the way back to 1987, and the ‘after’ shot was taken in 2018 from the Global TV helicopter by Trish Jewison.

Thirty three years ago Downtown South (to the east of Granville Street) was still all low-rise, mostly commercial buildings, that had replaced the residential neighbourhood that developed from the early 1900s. We’ve seen many posts that show how that area has been transformed in recent years.

In the 1986 census, just before the photo was taken, there were 37,000 people living in the West End (to the west of Burrard and south of Georgia), and only 5,910 in the whole of the rest of the Downtown peninsula (all the way to Main Street on the right hand edge of the picture).

In 2016, in the last census, the West End population had gone up to 47,200, adding 10,000 in 30 years. What was a forest of towers in 1987 had become a slightly thicker forest in 2018. The rest of Downtown had seen over a 1000% increase in 30 years – there were 62,030 people living there. Both areas will have seen more growth since 2016, and the 2021 census should show several thousand more people in both the West End and Downtown.

Gord Price – The 1987 shot really resonates for me: it was my first year on City Council. In the following 15 years, NPA councils would approve rezonings for seven megaprojects (four on the peninsula) and, notably, Downtown South – the area on the peninsula that has seen the biggest change (and continues to do so).

The ‘Living First’ strategy that came out of the 1980s (generally termed ‘Vancouverism’) was a ‘Grand Bargain’ for its time: we would take pressure off the existing residential areas, primarily the West End, through a 1989 de-facto downzoning (following the one that occurred in the early-1970s that resulted in an end to outright approvals for highrises), and concentrate growth east of Granville and north of Robson. In return for stability in the existing residential area, growth would be accelerated in the rezoned commercial/industrial parts of the map. That’s the ‘bargain’ – illustrated so vividly above.

I suspect everyone on Council and at City Hall would have nonetheless been amazed at the prospect of a thousand percent increase occurring so quickly. And yet, it did the job: the West End remained a lower-middle-income neighbourhood, where rents were above the regional average and incomes of the renters (over 80 percent of the residents) were below. (Most made up the difference by not having cars.)

I suspect everyone on Council and at City Hall would have nonetheless been amazed at the prospect of a thousand percent increase occurring so quickly. And yet, it did the job: the West End remained a lower-middle-income neighbourhood, where rents were above the regional average and incomes of the renters (over 80 percent of the residents) were below. (Most made up the difference by not having cars.)

There was effectively no change in the character of the community. Even today, one can walk most of the streets in the interior of the West End and have difficulty finding any buildings constructed after 2000. It is still the arrival city for immigrants and students (that’s why the Robson/Denman area is a ‘Little Korea’ of restaurants) and lower-middle-income renters. It is still able to accommodate brand new highrises on West Davie and a few other blocks under the recent West End plan without affecting the stability, physical or economic, of most of the district.

Of course, some people will still be under the impression that growth is ‘out of control’ and rents unaffordable, especially when noting the development proposals for the peripheral blocks between Thurlow and Burrard and rents in new buildings. ‘New’, by definition is more expensive than depreciated ‘old’ – but any argument that presumes new development should be rejected because of gentrification effects could have been used to prevent the development of the West End as we know it today, arguably now an urban miracle of affordable housing, given its location.

However, even though growth in most of the West End is practically sclerotic, people’s perception is based more on the rate of change than actual change. If not much has happened on your block over a decade, any change in scale is immediately impactful in a way that would not even be noticed a few blocks away in a high-growth area.

Now that most of the downtown peninsula has been built out (with only a few blocks left in places like the ‘Chandelier District’), the peninsula will now have few internal levers left to pull to take the growth pressure off. (And maybe in a post-pandemic world, it won’t be necessary for awhile.) But that means the pressure will eventually increase on land prices, rents and leases once scarcity is induced, unless there is a drastic change in the zoning to allow for the redevelopment of previous eras of housing stock – notably the low-rise wooden walkups that constitute such a critical mass of affordable housing.

So chances are an aerial shot of the peninsula taken 30 years from now won’t look all that much different in Changing Vancouver than the 2018 one in this week’s issue.

(Music and Love) Will See Us Through

It's been a while since I updated you about the music I've been making.

The basic plan hasn't changed and I'm managing to stick to it. One new piece of music a month, no more than a day to make it, stick it on all the channels, see how it feels and what I can learn.

How it feels and what I've learned:

- I'm a long way from having a 'style'. All the music services ask you to tag your music with a genre when you upload it and I haven't a clue what to say. And whatever it is I might say seems very different for each track. It's interestingly different to writing. I can only write one way - like this. But the music I make is more varied, not especially because of my sensibility but because of the place I start or the tool that I'm using.

- No one is listening. The Spotify listening figures (for instance) could all just be me making sure it's been uploaded right and seeing how it actually sounds a couple of days after I've made it. The random bits of promotion I've done produce no listeners either. I've been advertising in The Wire (more to support a publication I love than as a piece of genius marketing) but that has no effect either.

- I'm no producer. I think I'm alright at a lot of musical stuff but I'm a very poor listener. I don't have the patience or aptitude to pay that much attention to the music I've made. I can't hear the difference that mastering makes, I can't be arsed to make everything 'sit right' in the stereo (and couldn't hear it even if I did). EQ, reverb, compression, all that, is a closed book to me.

- It's still massive fun. Forcing myself to finish things and make them public is really useful. It is very like blogging - it doesn't matter that no one listens, it's enough to know that they could.

Actual music since the last update:

(Music and Love) Will See Us Through. It's pretty easy to come up with titles for tracks that feel cynical and clever but I wanted to do something more sincere. And I (really) enjoy playing with the effects of brackets (in titles) (and what that does to meaning). This is a prime example of not-being-a-producer disease. I just enjoy the groove and don't have the discipline to make it stop. So it goes on forever. Spotify. Bandcamp. Soundcloud.

Landline. This isn't too long! (Your mileage may vary...) It was the product of mucking about with a Keith McMillan BopPad and various Ableton Live configurations that made random hits of the pad seem pleasant. I couldn't work out how / be bothered to make it change key though, so it's a bit of a single mood outing. Still, quite gentle and inoffensive. Music for spreadsheets. Spotify. Bandcamp. Soundcloud.

The Best Android Tablets

If you’re not already invested in Android, an iPad is a better tablet in general than any current Android tablet, even for people who use Google’s apps and services. But Android tablets have improved significantly in recent years, and if you prefer Android to iOS, the best option is the Google Pixel Tablet. For $500, Google’s first tablet in years offers the best all-around Android tablet experience, with excellent hardware and solid performance. Google also includes a charging speaker dock, which turns the Pixel Tablet into a useful smart-home hub. You can buy the Pixel Tablet as a standalone device without the dock for $100 less, but we recommend the pricier bundle—it’s worth it.

What makes some API’s become DSL’s?

What causes an API to cross the line into becoming a DSL? Is it really a 'I'll know it when I see it' situation? I've been searching for an answer for years. And I think I found it in a paper I read recently for this podcast: Lisp: A language for stratified design. In this episode, we go over the main factor that makes an API a DSL: the closure property.

The post What makes some API’s become DSL’s? appeared first on LispCast.

The Best Wi-Fi Hotspot

If you lean on your phone as a Wi-Fi hotspot so often that you suffer from constant data-cap and battery anxiety, it might be time to upgrade to a dedicated hotspot. The Verizon Inseego Jetpack MiFi 8800L is one of the older models available and isn’t as fast as some newer devices, but it remains the most reliable choice when your phone’s mobile-hotspot features aren’t an option. Although it doesn’t support 5G, the MiFi 8800L takes advantage of the largest LTE network in the US, which remains fast in its own right and has data plans that are now a lot more generous.

The Interiority of 2020

Adjusting Zoom Volume Without Affecting Your System Volume, With SoundSource

If you’re looking to lower the volume of your Zoom calls without affecting your system volume, SoundSource has you covered, with this quick tip.

Zoom has a volume control in its Audio settings, but it’s linked directly to your output device. That means changing it will likely adjust the output volume for everything on your computer, often an undesired outcome.

To avoid this, you can instead use SoundSource to set an app-specific volume for Zoom, like so:

Voila!

With this configuration, SoundSource will only lower the volume of Zoom, while keeping your music at a higher level. Use SoundSource’s controls to get the exact audio setup you desire.

Interested in doing even more to make Zoom calls sound better? See our in-depth article on improving audio from Zoom calls.