One of the most interesting-to-think-about sub-genres of Adventure is the Robinsonade. That’s the moniker Johann Gottfried Schnabel coined in 1731 to describe the many imitations of Daniel Defoe’s wildly popular 1719 novel The Life and strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, where-in all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver’d by Pyrates.

If you’d like to see obscure but amazing adventure novels rescued from copyright limbo, back Save the Adventure’s kickstarter campaign before November 9. Save the Adventure is brought to you by Singularity & Co., the folks behind the science fiction book club Save the Sci-Fi. HiLobrow’s Joshua Glenn — who edits the HiLoBooks series of reissued Radium Age science fiction classics — is the Save the Adventure Book Club’s founding editor.

MORE LIT LISTS FROM THIS AUTHOR: Index to All Adventure Lists | Best 19th Century Adventure (1805–1903) | Best Nineteen-Oughts Adventure (1904–13) | Best Nineteen-Teens Adventure (1914–23) | Best Twenties Adventure (1924–33) | Best Thirties Adventure (1934–43) | Best Forties Adventure (1944–53) | Best Fifties Adventure (1954–63) | Best Sixties Adventure (1964–73) | Best Seventies Adventure (1974–83). ALSO: Best YA Fiction of 1963 | Best Scottish Fabulists | Radium-Age Telepath Lit | Radium Age Superman Lit | Radium Age Robot Lit | Radium Age Apocalypse Lit | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophe Lit | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Cold War “X” Fic | Best YA Sci-Fi | Hooker Lit | No-Fault Eco-Catastrophe Lit | Scrabble Lit |

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Introduction | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

*

Though most early Robinsonades take place on a desert island, any uncivilized locale (from the Outback to a newly discovered planet) will do — and, in the case of post-apocalyptic Robinsonades, de-civilized locales also work. Setting is not crucial to understanding the Robinsonade; instead, we must consider the sub-genre’s illiberal theme. The invisible prison from which the protagonists of Robinsonades have escaped — usually without intending to do so — is CONVENIENCE. The subtle or un-subtle message of every Robinsonade is that a life characterized by convenience is inauthentic, even damaging.

Thrown into a drastically inconvenient situation, the hero of a Robinsonade behaves rationally and prudently. She is persistent, calculating, careful, shrewd. She develops practical skills, and learns through trial and error how to subsist in a more convenient — but not ultra-convenient — manner. She experiments, prototypes, iterates. In short, she is a DIYer.

The Do It Yourself ethos is attractive to progressives and reactionaries alike. Rousseau romanticized the figure of Crusoe; in his 1762 treatise Emile, or On Education, the liberal philosophe claims that an ideal scheme of education would be “learning by doing.” (The only book the fictional student Emile is allowed to read for a long time is… Robinson Crusoe.) Neoliberal economists also admire Crusoe: he is a diligent and frugal homo economicus, an avatar of Enlightenment ideology and Protestant capitalist enterprise. Today, leftist critics point out that Crusoe’s brand of DIY is predicated on conquest, slavery, robbery, murder, and force; Crusoe is the supreme symbolic expression of British conquest. They’re right! But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Following the lead of anti-anti-utopian theorists like Ernst Bloch and T.W. Adorno, let’s try to enjoy the Robinsonade sub-genre, while seeking within it the “principle of hope.”

The next two installments of this series (after this one) will examine various aspects of the Robinsonade. In this installment, I’ll mention a few of my favorite adventure stories in which the DIY ethos plays a key role. Adventures that make readers feel the excitement and significance of hard work — physical or otherwise — and ingenuity. Adventures which thematize the thrill of building something from scratch, or making something useful that hitherto had no use. Adventures that valorize such moral aspects of work as patience, perseverance, endurance of fatigue and disappointment, technical shrewdness, and learning from mistakes. Adventures in which the protagonist faces practical problems, and solves them — in close, “granular” detail.

The next two Robinsonade installments of this series will look at the themes of un-alienated work and cozy catastrophe.

*

NINETEENTH CENTURY

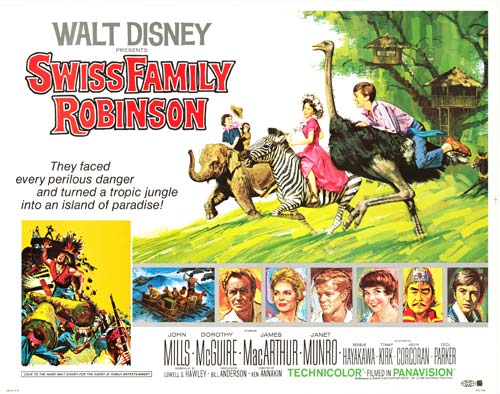

* Johann David Wyss’s 1812 novel The Swiss Family Robinson, which is explicitly inspired by Robinson Crusoe.

* “The Artist of the Beautiful” is an 1846 short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne about what appears to be unfocused work. Owen Warland has a penchant for carving figures of birds, flowers and other small figurines – this talent is of little use in the watchmaker’s shop owned by Peter Hovenden. Peter views his young apprentice as wasting time and is fearful that he’ll ruin the business. As luck would have it, Peter’s eyesight weakens to the point where he gives Owen ownership of the shop, and as Peter suspected, Owen allows the business to suffer. Owen has a secret project.

* Jules Verne’s survivalist adventure The Mysterious Island (1874), whose working title was Shipwrecked Family: Marooned With Uncle Robinson. Verne was enthusiastic about hard work and technical skill, and he firmly believed in capital-P Progress. However, the pleasure we derive from the detailed consideration of a practical problem and its solution (in, e.g., Robinson Crusoe and The Swiss Family Robinson) is difficult to find via Verne’s Robinsonades. Other examples from Verne: Two Years Vacation, The Robinson Crusoe School.

THE OUGHTS (1904-13)

* Dr. Pipt, in The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) by L. Frank Baum, is a brilliant inventor.

THE TEENS (1914-23)

* Locus Solus is a 1914 French novel by Raymond Roussel. John Ashbery summarizes Locus Solus thus in his introduction to Michel Foucault’s Death and the Labyrinth: “A prominent scientist and inventor, Martial Canterel, has invited a group of colleagues to visit the park of his country estate, Locus Solus. As the group tours the estate, Canterel shows them inventions of ever-increasing complexity and strangeness. Again, exposition is invariably followed by explanation, the cold hysteria of the former giving way to the innumerable ramifications of the latter. After an aerial pile driver which is constructing a mosaic of teeth and a huge glass diamond filled with water in which float a dancing girl, a hairless cat named Khóng-dek-lèn, and the preserved head of Danton, we come to the central and longest passage: a description of eight curious tableaux vivants taking place inside an enormous glass cage. We learn that the actors are actually dead people whom Canterel has revived with ‘resurrectine’, a fluid of his invention which if injected into a fresh corpse causes it continually to act out the most important incident of its life.”

THE TWENTIES (1924-33)

* In a 1932 essay (“L’Idée Fixe”), Paul Valéry compares himself to Robinson Crusoe — i.e., someone who has developed a self-taught way of thinking tested constantly from his own experience:

Je fabrique ma petite terminologie, suivant mes besoins… Ces sont mes outils intimes. Je me fais mes ustensiles, et les fais pour moi seul: aussi individuels et adoptés que possible à ma maniere de concevoir, et de combiner.

Vous n’êtes pas denué d’orgueil [says his interlocutor; then Valéry continues:]

En quoi? Est-ce que Robinson vous semble plus orgueilleux que quiconque? Je me considere comme un Robinson intellectuel.

* Professor Branestawm is a 1933–83 series of thirteen books written by Norman Hunter. Professor Theophilus Branestawm is the archetypal absent-minded professor. Sardonic inversion.

THE THIRTIES (1934-43)

* In 1934, while visiting a friend on Cuttyhunk Island, off the coast of Massachusetts, Elizabeth Bishop wrote admiringly in her journal: “You live all the time in this Robinson Crusoe atmosphere. Making this do for that, and contriving, inventing.” In 1971, Bishop would publish a poem titled “Crusoe in England.”

* In an essay (“Robinson Crusoe”) that appears in her Second Common Reader (1935), Virginia Woolf writes of the novel:

It is a masterpiece, and it is a masterpiece largely because Defoe has throughout kept consistently to his own sense of perspective… A man must have an eye to everything; it is no time for raptures about Nature when the lightning may explode one’s gunpowder — it is imperative to seek a safer lodging for it. And so by means of telling the truth undeviatingly as it appears to him — by being a great artist and forgoing this and daring that in order to give effect to his prime quality, a sense of reality — he comes in the end to make common actions dignified and common objects beautiful. To dig, to bake, to plant, to build — how serious these simple occupations are; hatchets, scissors, logs, axes — how beautiful these simple objects become.

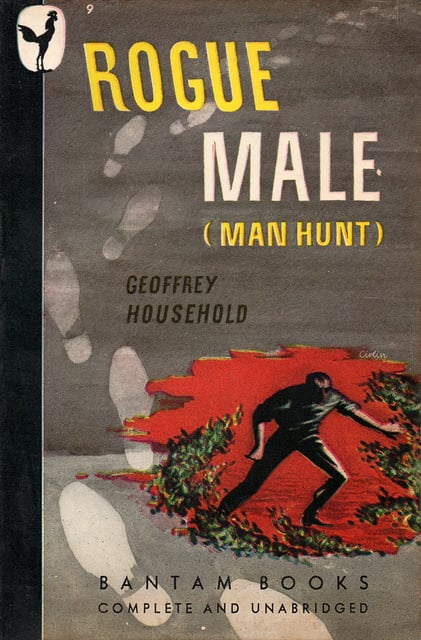

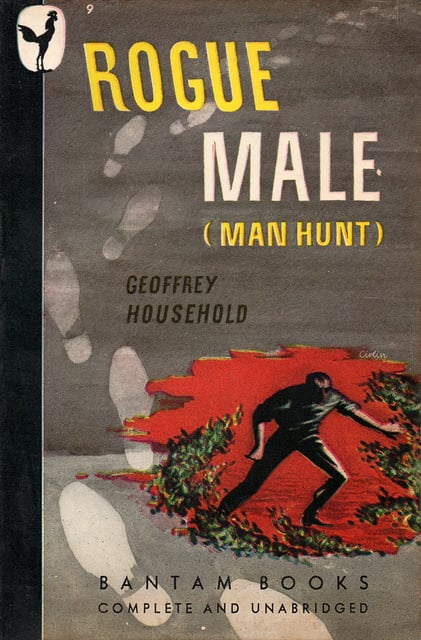

* Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (1939) is not a Robinsonade; in fact, it’s a prototypical Hunted Man adventure yarn. And yet… the protagonist is isolated from civilization, living in the rough, making do with materials he can scavenge in his immediate vicinity. At one point he must skin a beloved animal companion in order to fashion a deadly catapult.

* The character Batman, who first appeared in the May 1939 issue of Detective Comics, is a Crusoe-esque figure in the sense that he is a D.I.Y. superhero with no unique powers; his technical skills are, however, amazing. NB: Batman is an avenger-type adventure, though, not a Robinsonade.

* The first part of Walter Farley’s 1941 YA story The Black Stallion.

THE FORTIES (1944-53)

* The brilliant inventor Professor Calculus first appears in Red Rackham’s Treasure (1944), the twelfth volume of The Adventures of Tintin by Belgian cartoonist Hergé.

* Robert Heinlein’s 1948 YA novel Space Cadet (the part where they rebuild the ancient spacecraft).

* Not an adventure novel, but: The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas (Norwegian: Kon-Tiki ekspedisjonen) is a 1948 book by the Norwegian writer Thor Heyerdahl. It recounts Heyerdahl’s experiences traveling across the Pacific Ocean on a balsa tree raft.

* Rasmus Klump is a comic strip series for children created in 1951 by the Danish wife and husband team Carla and Vilhelm Hansen. The series was translated into a number of foreign languages, in some of which the title character Rasmus was renamed Petzi, Pol, Rasmus Nalle or other variations. My friend Luc Sante recalls: “A DIY monument especially in the first book, where the gang build their boat. Fortunately one of their number is a pelican, who always happens to have the needed tools secreted in his pendulous beak.”

THE FIFTIES (1954-63)

* Robert Heinlein’s 1955 YA novel Tunnel in the Sky.

* Pincher Martin: The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin is a survivalist novel by British writer William Golding, published in 1956. The protagonist is stranded on a god-forsaken, unmapped rock in the middle of the Atlantic after his ship is torpedoed by a German submarine. Much of his DIY survival here is psychological, devising daily routines to keep himself sane on the rock. SPOILER: turns out he’s not really on the island.

* John Galt, from Ayn Rand’s 1957 science fiction novel Atlas Shrugged, is a brilliant inventor.

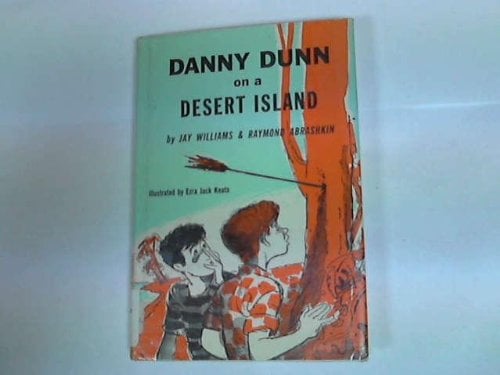

* Raymond Abrashkin and Jay Williams’s 1957 YA novel Danny Dunn on a Desert Island, in which Danny, his friend Joe Pearson, Professor Bulfinch and Doctor Grimes crash land on an uncharted desert island. Armed only with the items in their pockets, the four must create a living environment and come up with a plan to be rescued.

* Robert Heinlein’s 1958 YA novel Have Space Suit — will Travel (rebuilding the spacesuit).

* The supervillain Brainiac, who first appeared in Action Comics #242 in 1958, is a brilliant inventor.

* Jack Kirby’s reboot of Green Arrow in Adventure Comics #256 (1959) is a DIY Robinsonade.

* Alas, Babylon is a 1959 novel by American writer Pat Frank (the pen name of Harry Hart Frank). It was one of the first apocalyptic novels of the nuclear age.

* Jean Craighead George’s 1959 novel My Side of the Mountain. But not the same author’s Julie of the Wolves (1972) — which is instead about learning to trust your animal instincts.

* The Hardy Boys Detective Handbook is a special volume in the original Hardy Boys book series published by Grosset & Dunlap. My friend Rob Tourtelot recalls: “It featured the boys DIYing their way out of various wilderness survival predicaments. The book also had actual instructions on how to build the lean-to, water-catching device, or whatever else they’d used in each chapter. I recall a ‘stinky stove,’ with chunks of car tire burning in an upturned hubcap.”

* Some of Clifford B. Hicks’s YA Alvin Fernald books, including The Marvelous Inventions of Alvin Fernald (1960).

* Bertrand R. Brinley’s YA Mad Scientists’ Club series (1960–74).

* Mister Fantastic, the superhero created by writer Stan Lee and artist/co-plotter Jack Kirby, first appeared in The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961). He is a brilliant inventor.

* James and the Giant Peach is a popular children’s novel written in 1961 by Roald Dahl. There is a castaway/island aspect to it — i.e., the giant peach. The travelers must use ingenuity and tools they happen to have handy in order to survive; one thinks of the spiderwebs and the seagulls.

* The supervillain Victor von Doom of Latveria (also known as Doctor Doom), who first appeared in The Fantastic Four #5 (July 1962), is a brilliant inventor.

* In the 1962 John Wayne movie Hatari!, an invention to catch monkeys by character Pockets, played by Red Buttons, is described as a “Rube Goldberg.”

* The inventor Q, who first appears in the James Bond movie Dr. No, in 1962, is a brilliant inventor. Sardonic inversion.

* Iron Man/Tony Stark, who made his first appearance in Tales of Suspense #39 (March 1963), is a brilliant inventor.

THE SIXTIES (1964-73)

* Willy Wonka, from Roald Dahl’s 1964 children’s novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, is a brilliant inventor of fantastical machines. Ironic homage to this theme?

* The pushcart owners, in Jean Merrill’s 1964 children’s novel The Pushcart War, are DIY in their guerrilla campaign against the truckers. [Suggested by Annie Nocenti]

* “Professor” Roy Hinkley, a high school science teacher, on the 1964–67 TV show Gilligan’s Isle. A sardonic inversion.

* Pugsley Addams, in the 1964–66 TV version of The Addams Family, is a brilliant inventor. Ironic homage?

* Caractacus Pott is a brilliant inventor, in the 1964 YA spy novel Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car, by Ian Fleming. Ironic homage?

* The character Brains, from the 1965–66 British science fiction TV series Thunderbirds (“supermarionation”) is a brilliant inventor.

* Lloyd Alexander’s 1967 YA fantasy novel Taran Wanderer, an installment in the Prydain series, has a charming Robinsonade section.

* Robert C. O’Brien’s 1971 children’s novel Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH is in some places a Robinsonade — there are many practical problems to be solved, ingeniously, by the rats.

THE SEVENTIES (1974-83)

* James Grady’s 1974 thriller Six Days of the Condor — upon which the 1975 Robert Redford movie Three Days of the Condor is based — is a Robinsonade in the sense that the protagonist is cast adrift (he has nowhere to turn); and he must rely on his DIY survival skills — which he’s mostly learned from reading thrillers!

* Piers Paul Read’s 1974 nonfiction book Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors is a grisly example of a Robinsonade.

* William Steig’s 1976 children’s novel Abel’s Island is a survival story of a mouse stranded on an island. [Suggested by Tor Aarestad]

* John Jerome didn’t write adventure novels, but his nonfiction books — Truck: On Rebuilding a Worn-Out Pickup and Other Post-Technological Adventures (1977), Stone Work: Reflections on Serious Play and Other Aspects of Country Life (1989) are in this same vein.

* Lucifer’s Hammer is a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, first published in 1977. Survivalist.

* Jean M. Auel’s 1980 novel The Clan of the Cave Bear has some Robinsonade-esque qualities. The Cro-Magnon girl Ayla — raised by Neanderthals — teaches herself survival skills.

* The superhero Cyborg, created by writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez, who first appears in a special insert in DC Comics Presents #26 (October 1980), is a brilliant inventor.

* Large parts of L. Ron Hubbard’s 1982 novel Battlefield Earth.

* In the 1982 movie First Blood, troubled Vietnam vet John Rambo flees civilization for an isolated patch of wilderness, where he puts his awesome survival skills to use making himself a home… surrounded by traps. (Robinson Crusoe also spends a lot of his time building up his defenses; so does the Swiss Family Robinson.) Vietnam vets in US popular culture were for years frequently portrayed as possessing survival skills and practical ingenuity that non-combatants lack. Think of The A-Team on The A-Team (1983–87) and the weapons they build in each episode; think of MacGyver on MacGyver (1985–92). Marvel Comics’ The Punisher (1974) has some awesome weapon-building skills; so does Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976), and also Jason Bourne/David Webb in Robert Ludlum’s Bourne novels (1980–90). (Note, however, that these characters mostly appear in avenger- and hunted man-type adventures, not Robinsonades.)

THE EIGHTIES (1984-93)

* Donatello, one of the four protagonists of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comics, is a brilliant inventor. The comic first appeared in 1984.

* Some parts of the 1985 movie Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome.

* Richard “Data” Wang in the 1985 adventure–comedy movie The Goonies is a brilliant inventor. His inventions don’t seem to work… but when he needs them to work, they end up working. An ironic homage — not a sardonic inversion.

* In the 1985 Tim Burton movie Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Pee-wee Herman is a brilliant inventor. Also in the 1986–91 TV show Pee-wee’s Playhouse, and in the 1988 movie Big Top Pee-wee.

* The 1985–92 TV show MacGyver.

* The character Nite Owl, from Alan Moore’s The Watchmen, which began its run in 1986.

* Gary Paulsen’s 1987 YA survivalist novel Hatchet and its sequels.

* Harold Allnut, who helps Batman to design, build, and repair his equipment, first appeared in a 1989 issue of The Question.

* Wallace and Gromit, from Nick Park’s stop motion comedy film series, first appeared in A Grand Day Out (1989). Both brilliant inventors.

* Billy Cranston (the Blue Power Ranger), from the 1993–95 TV show Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, is a brilliant inventor.

THE NINETIES (1994-2003)

* Violet Baudelaire, in the series A Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket, is a brilliant inventor. The first book in the series appeared in 1999.

THE OUGHTS (2004-13)

* Dies the Fire is a 2004 alternate history and post-apocalyptic novel by S. M. Stirling. It is the first installment of the Emberverse series; it chronicles the struggle of two groups who try to survive “The Change”, a mysterious worldwide event that suddenly alters physical laws so that electricity, gunpowder, and most other forms of high-energy-density technology no longer work. As a result of this, modern civilization comes crashing down.

* Some aspects of Trenton Lee Stewart’s 2007 YA novel The Mysterious Benedict Society — and its sequels. Kate “The Great Kate Weather Machine” Wetherall is a twelve-year-old girl who is resourceful and athletic, and she carries a bucket containing a Swiss Army knife, a flashlight, a pen light, rope, a bag of marbles, a slingshot, a spool of clear fishing twine, a horseshoe magnet and a spyglass disguised as a kaleidoscope. Ironic homage?

* The inventor character Walter Bishop, in the 2008–13 J.J. Abrams tv series Fringe.

* Finn and Jake in the 2008–present Cartoon Network animated series Adventure Time. The series follows the adventures of Finn, a human boy, and his best friend and adoptive brother Jake, a dog with magical powers to change shape and grow and shrink at will. Finn and Jake live in the post-apocalyptic Land of Ooo.

* The Hunger Games is a 2008 science fiction novel by American writer Suzanne Collins.

* One Second After is a 2009 fiction novel by American writer William R. Forstchen. The novel deals with an unexpected electromagnetic pulse attack on the United States as it affects the people living in and around the small American town of Black Mountain, North Carolina.

***

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Introduction | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

***

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY THIS AUTHOR: We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | Calvin Peeing Meme | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series) | Save the Adventure (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Previously in Taking You Up On That Offer: Tim Curry and Morgan Freeman Finally Read The Phone Book Out Loud Together.

Previously in Taking You Up On That Offer: Tim Curry and Morgan Freeman Finally Read The Phone Book Out Loud Together.