Hima2303

Shared posts

Most Cave Painters May Actually Have Been Women

Naughty meanings and naughty words

Hima2303"Are we a nation permanently locked in preschool? The answer, in the case of language, is yes."

Piraro makes the point that he is allowed to publish a cartoon showing a street prostitute holding up a sign saying "GLUTEN FREE" (see it here), but he was censored when he came out with a cartoon showing a deadbeat vampire loiterer holding up a sign saying "WILL SUCK FOR BLOOD". Both clearly suggest the possibilty that oral sex is being referred to, if you have a dirty mind, but the second explicitly contains a word (suck) commonly recognized by the relevant prudish authorities as colloquial sex talk, wheras the first doesn't. The prostitute cartoon would doubtless also have been banned if it had incorporated the word eat, instead of just implying it through the reference to a potentially allergenic food ingredient. Piraro's comment on the situation is: "Americans (and maybe all humans, I'm not sure) are more obsessed with words than with their meanings."

He goes on:

I will never understand this as long as I live. Under FCC rules, in broadcast TV you can talk about any kind of depraved sex act you wish, as long as you do not use the word "fuck." And the word itself is so mysteriously magical that it cannot be used in any way whether the topic is sex or not. "What the fuck?" is a crime that carries a stiff fine — "I'm going to rape your 8-year-old daughter with a trained monkey," is completely legal. In my opinion, today's "gluten-free" cartoon is far more suggestive in an unsavory way than the vampire cartoon, but it doesn't have a "naughty" word so it’s okay.

Are we a nation permanently locked in preschool? The answer, in the case of language, is yes.

He makes a very good point, IMHO.

5 Americans who used NSA facilities to spy on lovers

Hima2303What love!

(Photo by Marcel Oosterwijk)

Last month, we reported on LOVEINT, the facetious term used to describe NSA analysts who misuse their surveillance powers to spy on romantic interests instead of terrorists. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) asked the NSA to get more specific about the misconduct the NSA had uncovered. So the NSA sent Grassley a letter with details of the 12 LOVEINT incidents it has uncovered since 2003.

The incidents have a number of things in common. Almost all of them involved spying on foreigners outside of the United States (one man targeted his American girlfriend, and a few others spied on communications involving both Americans and foreigners). In seven of the 12 cases, the misbehaving employee resigned while the disciplinary process was ongoing. The rest received letters of reprimand, got demoted, lost pay, were denied security clearances or faced other punishments. None of the individuals were prosecuted for their actions.

Here are five of the most egregious cases of misconduct:

1. Man spies on nine women over a five-year period.

Between 1998 and 2003, a man listened to the phone conversations of nine different women, all of them foreigners. He got caught when a woman he was sleeping with started to suspect he was spying on her and notified U.S. authorities. On two occasions, he "incidentally collected the communications of a U.S. person." The man was suspended without pay, and resigned before further disciplinary action could be brought against him.

2. Woman spies on prospective boyfriends to make sure they're not "shady characters."

In 2011, a woman used NSA surveillance facilities to spy on her "foreign-national boyfriend and other foreign nationals." She admitted that it "was her practice to enter foreign national phone numbers she obtained in social settings" into the NSA's surveillance system to "ensure that she was not talking to 'shady characters.' " She resigned before she could be disciplined.

3. Man checks whether girlfriend is "involved with any government officials."

In 2003, a man spied on his non-American girlfriend for a month to see whether she was "involved with any [local] government officials or other activities that might get [the man] in trouble." It's not clear if the surveillance involved intercepting telephone calls or just accessing calling records. He admitted his actions to investigators in 2005, but he was allowed to retire before disciplinary action was taken against him.

4. Woman spies on husband to see if he's cheating on her.

In 2004, a woman admitted that she had spied on a "foreign telephone number she had discovered in her husband's cellular phone because she suspected that her husband had been unfaithful." The spying included intercepting call audio. The woman resigned before facing disciplinary action.

5. Man spies on his American ex-girlfriend, says he was just practicing.

On his first day of access to the NSA's surveillance system, a man spied on six e-mail addresses belonging to an ex-girlfriend. The NSA caught him four days later. He claimed that he "wanted to practice on the system and had decided to use this former girlfriend's e-mail addresses." He claimed not to have read anyone's e-mail. He was demoted, assigned 45 days of extra work, lost half his pay for two months, and was denied a security clearance.

The global upper class makes 32 times as much as the global lower class

Hima2303Palma

If you've ever seen a chart or map or animated gif map or something about economic inequality, chances are it uses something called the Gini coefficient. It's the standard measurement, but it's also way too complicated to explain, as the Center for Global Development's Alex Cobham illustrates in this video:

Cobham and other development experts have come to prefer something called the Palma ratio. The ratio is named after Gabriel Palma, an economist at the University of Cambridge who noticed that the 40th through 90th percentiles of a country's income distribution tend to always get the same share of income. The amount going to the bottom 40 and top 10 percentiles varies quite a bit, but the middle doesn't change much if you look across different years, countries and levels of economic development. For example, here's the 2010 breakdown. Note that the green columns, showing the middle 40th-90th percentiles, don't change much at all, even when the tails are changing dramatically:

That lead to a great idea: How about, instead of doing the complicated gymnastics needed to calculate the Gini, we just divide the top 10 percent's share of income by the bottom 40 percent's? That's the Palma ratio. And it's much easier to grok than the Gini. A Palma ratio of 5 means the country in question has an top 10 percent that makes 5 times as much as its bottom 40 percent; a Gini ratio of 0.5 means, well, it's hard to explain.

Despite being easier to explain, the Palma aligns nearly perfectly with the Gini. Cobham and Andy Sumner ran a regression and found that the two components of the Palma (the top 10 percent and bottom 40 percent's shares of income) explain 100 percent of variation in countries' Gini ratios. But that's at least partly because the World Bank uses limited data to compute Gini coefficients. In situations where there are better data, the two can diverge, and in a way that makes the Palma look much more attractive as a measure. The Gini overweights changes in inequality that happen in the middle of the income distribution, which is exactly not what we should be looking at, given how stable the middle is.

This is particularly troublesome when you're using the Gini to measure how much a policy increases or decreases inequality. "The difficulty with using Gini for that is that you'll get unclear answers," Cobham says. "If the policy is good for the top 10 percent and bad for the bottom 40 percent but progressive in the middle, then the Gini could show a regressive measure as progressive."

How do various countries stack up on the Palma? The table to the right, from a Danish Institute of International Studies (DIIS) report, provides a good sampling of scores. Developed countries like the United States and United Kingdom tend to have ratios below 2. Especially equal countries, like Denmark or Japan, have ratios below one. But a number of poor countries are in that zone, too. India's ratio is below the United States, for instance, as is Tanzania's. And Burkina Faso and China aren't too far above us.

It's middle-income countries where inequality has really gotten out of hand. Brazil's Palma is above 3, and South Africa's is above 7. They've had plenty of economic growth, but it's been unequally distributed, and their welfare states are not yet at a point where that can be counteracted through things like public education, transfer payments, progressive taxation and so forth.

But the most shocking number from that report is the global Palma: the ratio of the top 10 percent's share of world income to the bottom 40 percent's share, taking every country into account. The ratio, DIIS estimates, is about 32. Those of us in the richest 10 percent globally make 32 times more than the bottom 40 percent.

It's another reminder that, while extreme poverty in the United States is very real, the biggest inequalities, by far, are at the global level. "The political instruments for reducing income inequality between the richest 10 per cent and the poorest 40 per cent of the world’s population do not exist," author Lars Engberg-Pedersen notes. "Progressive taxation, provision of social security, etc. are country-level instruments, and official development assistance comes no way near addressing global inequality."

It's nowhere close to enough, but I'd be remiss without noting that giving money directly to poor people in Kenya is one way individuals can chip away ever-so-slightly at the problem.

Theory of Mind Hacks

Hima2303:)

One of the problems with the principles of cooperative communication is that those who don't adhere to them are generally able to manipulate those who do. I've never seen an account of how such principles endure in the face of rampant (and mostly unpunished) default, though I suppose that you could try to maintain a version in which the principles' effect depends only on a general pretense of trying to communicate cooperatively…

[Tip of the hat to Tim Leonard]

The social cognition of linguists

Hima2303Self-appraisal.

Andrea C. Schalley

Griffith University

It is social cognition which enables us to construct functioning societies sharing knowledge, values and goals, and to undertake collaborative action. It is also crucial to empathising and communicating with others, to enriching imprecise signs in context, to maintaining detailed, differentiated representations of the minds and feelings of those who share our social universe, to coordinating the exchanges of information that allow us to keep updating these representations, and to coopting others into action.

(Evans 2012)

What about the linguistic research community – is this a “functioning society”, to use Evans’ notion? Which knowledge, values, and goals are we (and I consider myself a member of this “society”) aiming to share? What are our goals? In this post, I will try to look at “the linguists” as a “society” and discuss whether it is “functioning” from a “social cognition” point of view. I hope that a meta-discussion on the state of linguistics may result, potentially benefitting the further progress and development of the field.

So – let us draw some parallels:

-

Society:

The society under scrutiny is the linguistic research community. -

Knowledge:

Knowledge important to the society is how language as a phenomenon / specific languages work and how language is used. This has roughly (!) led to three main knowledge domains in linguistics – theoretical linguistics (how language as a phenomenon works), descriptive linguistics (what we know about specific languages), and applied linguistics (how language is put to use). Naturally, these domains intersect and inform each other, and each has been split further into subdomains – fields of research such as phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, first and second language acquisition, multilingualism, sociolinguistics, language change, language contact, language documentation, or linguistic typology, to mention a few. -

Values:

The society values a scientific approach to language; overall, there is an expectation that ‘good science’ is carried out in the discipline. Nonetheless, methodological disagreements do exist and a substantial number of schools of thought can be found in the society. -

Members and groups in the society:

These schools of thought form ‘social groups’ within the society, groups that complement and support but also compete with each other. The groups can be likened to kinship groupings in social terms (‘X is a student of Y’), or, if more broadly based on theoretical or subfield-based notions, on the ingroup/outgroup distinction (‘She is a generative syntactician’). Communication across such groupings is often difficult due to specific ‘ingroup’ terminology, but loyalty considerations also often prevent members of the society from being open-minded towards other social groups within the society. -

Goals:

Dietmar Zaefferer (as cited in Schalley 2012b:20) has summarized the goals of the society very eloquently: the society aims to(a) deepen our understanding of the form, content, and use of linguistic symbols,

(b) gain insights into the architecture of languages and their subsystems,

(c) elucidate the interplay between linguistic and other cognitive feats as well as

(d) between the corresponding individual and trans-individual characteristics of our minds, and therefore

(e) contribute to human self-conception in its specificity.

Yet, what about undertaking collaborative action, the last point listed in the first sentence of Evans’ quote? How are the items listed above impacting on it? In the following, I will concentrate on a discussion of how well the linguistic research community organizes its ‘collaborative action’. Instances of this include, amongst others, the collaboration of individual linguists on a joint project (e.g., as part of a funded research project), or collaboration in the sense that knowledge is shared through a coordinated exchange of information (for instance via peer-reviewed publications).

Interestingly, in these cases there are external gatekeepers involved, whose aims we cannot expect to be well aligned to the linguistic society’s goals. These include (i) funding bodies, who have to take political agendas into account, (ii) publishers, who are market-driven and thus do not necessarily prioritize the society’s goals, and (iii) employers, who want to increase the overall institution’s reputation and performance, resulting in at times detrimental decisions for the linguistic society and some of its members (e.g. by them not being allowed to apply for external funding). So one question the society should be asking itself is how it can best manage these external factors and minimize their impact on the society and its aims as a whole. Contributing to peer reviewing is one possibility, but there are other more ‘radical’ options available to us, such as taking over some of the gatekeepers’ functions. An example of the latter is the recent establishment of Language Science Press, an imprint growing out of the Open Access in Linguistics initiative. Of course, this requires sustained collaborative action within the society – and collaborative action of a different nature than the one mentioned above, as this is not just about furthering linguistic research per se.

The other question is what internal processes and procedures the society has set up to enable collaborative action and knowledge sharing within the field. Building on Evans (2012) quote from the beginning, how good are we in

- “empathising and communicating with others”

(e.g. communicating about each other’s research), - “enriching imprecise signs in context”

(e.g. understanding each other’s way of “doing linguistics”, including the terminology we use), - “maintaining detailed, differentiated representations of the minds and feelings of those who share our social universe”

(e.g. conceptualizing each other’s views and perspectives on linguistics), - “coordinating the exchanges of information that allow us to keep updating these representations”

(e.g. coordinating exchanges of linguistic data and knowledge on language or languages), - “coopting others into action”

(e.g. getting each other to make an effort to share our data and knowledge)?

This appears to be an area where we can surely improve. Linguistic diversity, while highly enlightening, also poses a major challenge here: due to the nature of the field, any linguist will only have access to or study (a) a limited number of languages, (b) a limited number of linguistic phenomena, and (c) a limited amount of literature and/or fieldwork data. It is impossible for any scholar to obtain a comprehensive overview of even one small phenomenon across the languages. With around 5,000–8,000 living languages (according to Ethnologue, there are currently 7,105 known living languages; Lewis et al. 2013), even for a simple feature such as the order of the object and verb, there is ‘merely’1 collated information on currently 1,519 languages available, as provided by The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) (cf. Dryer 2011), and thus for about 20% of the currently known living languages.

But how can we achieve more comprehensiveness? This is only possible by collaborating closely and sharing and integrating the knowledge we have. No single person will ever be able to take in and process all the data that we have about the world’s languages. Any linguist’s knowledge can, due to the nature of the field, be compared to pieces of a puzzle. Cross-linguistic work relies on being able to put these pieces together, and this can only happen through ‘collaborative action’. A sustained collaborative effort of the field is needed to put the puzzle together, with scholars integrating their knowledge into an overall knowledge base that can be flexibly queried, i.e. a storehouse of discipline knowledge that is integrated enough to allow access from different perspectives and with different aims in mind. Given current technological developments (e.g. Semantic Web technologies), I believe we have arrived at a crossroads. It now appears that we have the technical infrastructure to seriously start such an enterprise – and we need to take advantage of this opportunity. True progress of the field, given the constraints just discussed, will rely on linguists substantially contributing to such a collaborative enterprise, and thus allowing themselves as members of the society to be coopted into action. For this to happen, we need to find ways of rewarding contributions to such efforts (and not just of ‘independent’ publications such as papers and books); initial progress towards this is being made right now (cf., for instance, discussions currently held in Australia to establish appropriate recognition for curated corpora). We also need to be accepting of terminological differences and schools of thoughts (and hence to find ways of dealing with, for instance, the tension between in-depth language-specific description and broader cross-linguistic comparison, cf. Haspelmath 2010). There are incipient efforts under way to solve the technical and conceptual challenges and to establish a knowledge base that allows to do this and to carry out such collaborative action (e.g. Borkowski & Schalley 2011; Schalley 2012a, c); thus potentially leading towards the creation of a storehouse of discipline knowledge. Efforts are also increasing to link currently available data for further processing (cf. the Linguistic Linked Open Data Cloud, an initiative of the Working Group on Open Data in Linguistics).

Of course, many challenges still lie ahead. Nonetheless, we are likely to have to change the ways in which we disseminate our research in order for the field to progress substantially. Are you open to it?

Notes

1 I have put ‘merely’ in single quotation marks, as having such information collated for so many languages is indeed a major achievement. Hence – while it is ‘merely’ accessible for 20% of the known living languages – this is nonetheless a most impressive result, and the one with the most languages involved I know of.

References

Borkowski, Alexander & Andrea C. Schalley 2011. Going beyond archiving – a collaborative tool for typological research. In: Nick Thieberger, Linda Barwick, Rosey Billington & Jill Vaughan (eds.), Sustainable Data From Digital Research: Humanities Perspectives On Digital Scholarship. Melbourne: Custom Book Centre, University of Melbourne, 25–48. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7932.

Dryer, Matthew S. 2011. Order of object and verb. In: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online.

Munich: Max Planck Digital Library, chapter 83. http://wals.info/chapter/83,

accessed 17 September 2013.

Evans, Nicholas. 2012. The refraction of other minds: Language, culture and social cognition. Nijmegen Lectures 2011 (January 9-11, 2012), Lecture 2. http://www.mpi.nl/events/nijmegen-lectures-2011/program-abstracts/lecture-2, accessed 16 September 2013.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2010. Comparative concepts and descriptive categories in crosslinguistic studies. Language 86(3): 663-687.

Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Seventeenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.

Schalley, Andrea C. 2012a. Many languages, one knowledge base: Introducing a collaborative ontolinguistic research tool. In: Andrea C. Schalley (ed.), Practical Theories and Empirical Practice. A Linguistic Perspective. (Human Cognitive Processing 40.) Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 129–155.

Schalley, Andrea C. 2012b. Practical theories and empirical practice – Facets of a complex interaction. In: Practical Theories and Empirical Practice. A Linguistic Perspective, ed. Andrea C. Schalley. (Human Cognitive Processing 40.) Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1-31.

Schalley, Andrea C. 2012c. TYTO – a collaborative research tool for linked linguistic data. In Christian Chiarcos, Sebastian Nordhoff & Sebastian Hellmann (eds.), Linked Data in Linguistics. Representing and Connecting Language Data and Language Metadata. Heidelberg: Springer, 139–149.

How to cite this post:

Schalley, Andrea C. ‘The social cognition of linguists.’ History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences. http://hiphilangsci.net/2013/09/25/the-social-cognition-of-linguists

Belle Waring: On the IMPORTANT MALE NOVELISTS of the Late Twentieth Century: Noted

Belle Waring: It May Interest You to Know, But If Not, There Is a Scroll Feature

Is it really the case that pretty much all the Important Male Novelists of the mid to late 20th-century are such sexist dillweeds that it is actually impossible to enjoy the books? That would be a bummer, wouldn’t it? Unfortunately, the answer is yes…. The past is a region ruled by the soft bigotry of low expectations. We all allow it to run up against the asymptote of any moral value we hold dear now. We are moved by the ideals of Thomas Jefferson even though we know he took his wife’s little sister, the sister she brought with her as a six-month old baby, the very youngest part of her dowerage when she married him--he took that grown girl as a slave concubine, and raped that woman until he died. We would all think it a very idiotic objection to The Good Soldier Švejk that women weren’t allowed to serve in the military at that time and so it didn’t bear reading.

My favorite part of the Odyssey is book XXII, when Odysseus, having strung his bow, turns its arrows on the suitors and, eventually, kills them all. This is despite the fact that he and Telemachus go on to hang the 12 faithless maids with a ship’s cable strung between the courtyard and another interior building, so that none of them will die cleanly, and they struggle like birds with their feet fluttering above the ground for a little while, until they are still. There is no point in traveling into the land of “how many children had Lady MacBeth,” but, at the same time--the suitors raped those women, at least some of them, and likely all, if we use our imagination even in the most limited and machine-like fashion on the situation. Still it is my favorite, because I am vengeful….

Often the protagonist of an Important Novel of the Latter Half of The 20th Century is male, and is a thinly veiled version of the author. So thin of a veil. A veil so thin is it possible to discern whether the author was circumcised…. He regards women as, one the one hand a mere necessary evil, not things one would be inclined to befriend or discuss life with, and on the other hand, beings of terrible power that make one very angry indeed. This terrible power is that you can be betrayed by your own desires and want some woman so badly, and it doesn’t matter how stupid you think she is, if you really want to have sex with her that badly, all bets are off and you, in some sense, have no say in the matter…. The Important Novelist tends to do two things. Firstly, he projects his anger at his inability to control his own sexual desires into the female characters, by having them be plotting to ensnare the male ones, variously. Secondly, he constructs his female characters like a socially immature game developer, from the outside in, and boy howdy does it show. “I’m going to pick blonde. Ooh, ooh, and make her tits bigger!”

As a male reader, I imagine you are probably inclined to feel that in every novel some characters are more fully developed than others, and further, that the degree to which anyone really has a plausible interior life at all varies quite a lot between authors, so the fact that none of the female characters are well-developed and none of them have a plausible interior life might not immediately register. If you are a woman reading these novels it registers painfully and clunkily and woodenly, every page, all the time. It’s as if someone has stuck 8-bit Mario into Grand Theft Auto V but hasn’t noticed any difference and doesn’t expect that anyone else will either. He’s made of giant squares! What the--….

I am not an aesthetic Stalinist. (One hopes these things go without saying, but it has become very clear they do not.) The point here is not evaluating how many grams of feminist OKness each book achieves so that I may weigh it against the feather of Ma’at and either send it on its way or let it be devoured by the terrifying crocodile-headed goddess Ammit.

The point is rather, I judge novels that were written during a time when men perfectly well could have known that the women they spoke to were intelligent human beings, in which the authors nonetheless fail in varied awful incredible ways to represent the 51% of humanity involved, to have failed qua novels. It is a necessary result of the Updike-version sexist writing that your novel fails to be even a passable novel. It is actually somewhat embarrassing for everyone. DFW was inclined to be more charitable.

Addendum: sometimes I think, ‘I write so many words every day getting into arguments with stupid people online, surely I should post on CT instead and talk to intelligent people?’ At other times I remember exactly why I am often disinclined to do the latter. Please be civil.

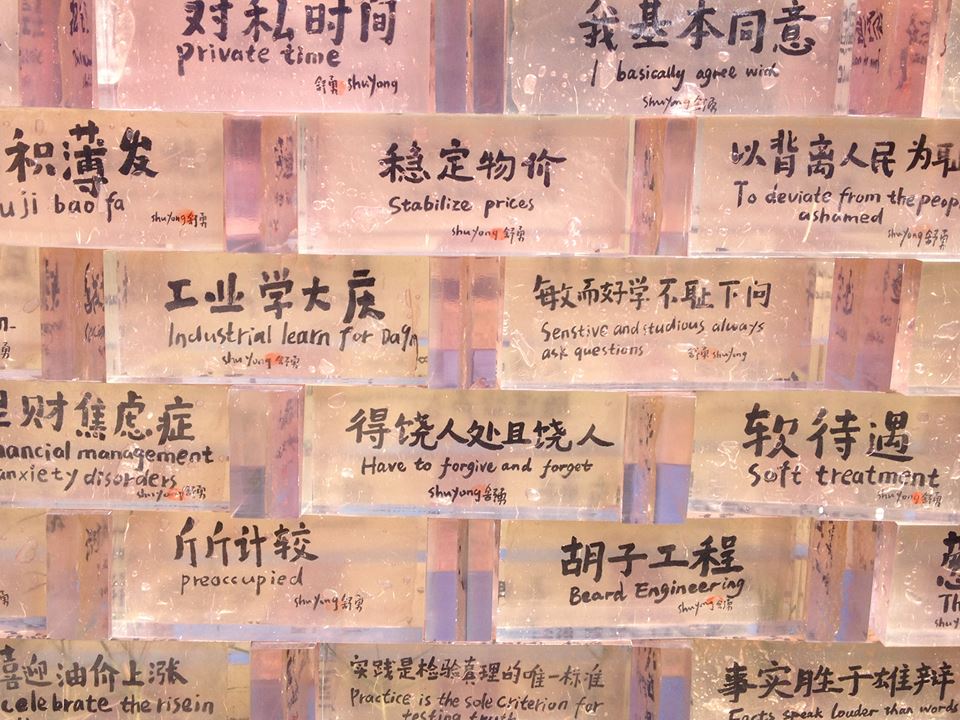

Bilingual bricks: Google as "Valley Song"

Hima2303guge

Here is a closeup of a remarkable work of installation art that is being shown at this year's Venice Biennale:

There is a short article on this thought-provoking work in Art & Science Journal. Written by Lea Hamilton and entitled "Lost in Translation: Shu Yong’s Guge Bricks", it includes five exceptionally clear photographs.

Anita Hackethal has written a brief essay about the artist and his work: "shu yong: great wall of guge bricks at the china pavilion". Since Hackethal's essay is both informative and illuminating, plus being well illustrated, I quote here the opening two paragraphs:

in his installation for the venice art biennale 2013, chinese artist shu yong constructs a sculptural reflection on the divide between eastern and western values and the 'googlization' of culture in contemporary society. yong solicited 1500 different maxims, quotations, mottos, and popular phrases from fellow chinese citizens and translated them word by word into english using google. he then wrote both the chinese and corresponding english literal translation for each selection in calligraphy onto a piece of xuan rice paper, which was embedded into an individual transparent brick of cast resin, shaped to the proportions of those in the great wall of china.

the resulting mass of 1500 'guge' bricks forms a solid wall in the exhibition courtyard, before crumbling into disorder at one side. they are an artifact to a particular moment in time and culture, where newly popular circulated words join traditional quotations before all are subjected to machine translation that jumbles and displaces their significance: 'into a new era' and 'marching towards science' join 'garlic you cheap' and 'boy crisis' in the translated english. shu yong finds these bricks a fitting metaphor for the ways that eastern and western cultures remain divided: even in the age of globalization and realtime communications, the transparent wall will remind us to confront the hidden 'walls' between different countries, nations, and individuals. at the same time, the chinese public's inclusion of words like 'photobomb' among the bricks is a reminder of cross-cultural influences.

In case you were wondering, "guge" is the Chinese transcription of "Google": Gǔgē 谷歌 (lit., "Valley Song"). However, since we're dealing with simplified characters in the PRC, Gǔgē 谷歌 conceivably could also mean "Grain Song", but I don't think that's what Google intended. The simplified character gǔ 谷 ("valley; grain") collapses two traditional characters, gǔ 谷 ("valley") and gǔ 穀 ("grain") into one. This is the same type of problem that led to the monumental confusion between "dry" and "f*ck", which we have covered in this and other posts on Language Log.

[h.t. Petya Andreeva]

Cli-Fi: Birth of a Genre

Hima2303cli-fi

Perhaps climate change had once seemed too large-scale, or too abstract, for the minutely human landscape of fiction. But the threat seems to have become too pressing to ignore, and less abstract, thanks to a nonstop succession of mega-storms and record-shattering temperatures. Several new novels make climate change central to their plot and setting, appropriating time-honored narratives to accord with our new knowledge and fears. {…}

It's baack…

"Cows Have Accents … And 1,226 Other 'Quite Interesting Facts'", NPR Weekend Edition 9/14/2013:

Did you know that cows moo in regional accents? Or that 1 in 10 European babies was conceived in an IKEA bed? Or that two-thirds of the people on Earth have never seen snow?

The BBC quiz show QI celebrates these "quite interesting" tidbits of information with obscure questions that reward the players for both correct answers and interesting ones. John Lloyd, one of the creators of the show, teamed up with QI researchers John Mitchinson and James Harkin to compile a treasure trove of factoids in 1,227 Quite Interesting Facts to Blow Your Socks Off.

I'm not sure about the Ikea-bed and snow-virgin factoids — they seem plausible, but the mere fact that the source is the BBC makes me suspicious. For some background on the cow-accent thing, with links to some other sagas of epic BBC-mediated misinformation, see "It's always silly season in the BBC Science Section", 8/26/2006.

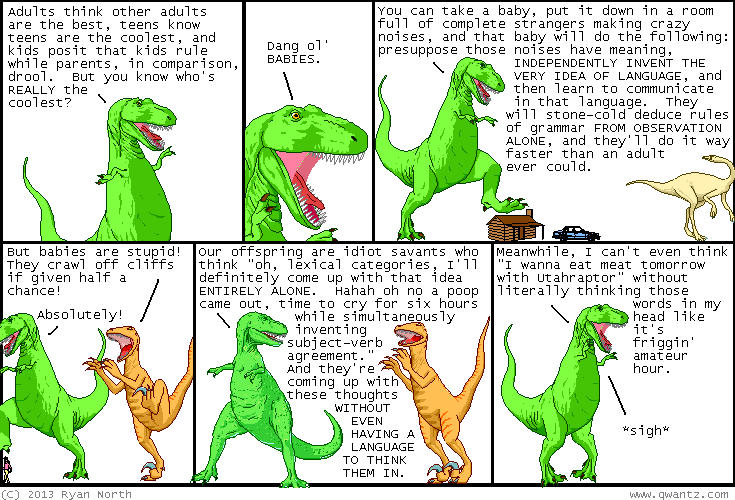

Who's REALLY the coolest?

Hima2303:D

Dinosaur Comics for 8/26/2013:

Click on the image for a larger version that lacks some mouseover text helpfully glossing what is expressed by “*sigh*”.

Hat tip: Bonnie Krejci

A miscellany of mondegreens

Hima2303benny lava :P

Click here for a stellar collection of mondegreens from comedian Peter Kay. And prepare to have half a dozen songs ruined for you forever. A mondegreen is a speech perception error that causes you to hear the words of a song incorrectly. Peter Kay tells you what you're going to hear, and then plays passages from well-known pop songs of the last decade or two, often miming the crucial part; and thereafter you will never be able to hear those lines any other way. In fact you will forget what the real words were in the first place. Be afraid; be very afraid.

849-2: Poltroon

Poltroon was one of the nineteenth century’s favourite insults, meaning an utter coward, often preceded by adjectives such as base or wretched. Stories of the more sensational kind preferred stronger words:

“If you are not, after all,” resumed the duke, “the veriest coward and most lily-livered poltroon in all his majesty’s dominions, follow me into that carriage, Prince.”

[Sylvester’s Eve, By William Henry Farn, published in Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine in 1843. Lily-livered poltroon became a cliché, later to be mocked by P G Wodehouse.]

In the eighteenth century its origin was widely believed to be that suggested by an eminent French classical scholar of the previous century, Claudius Salmasius. He theorised that the word derived from medieval longbowmen. One who wished not to risk his skin in combat had only to make himself incapable of drawing a longbow by cutting off his right thumb. In Latin, pollice truncus meant maimed in the thumb; Salmasius asserted that this had become corrupted into the French poltron.

In the nineteenth century this wildly inventive view was no longer believed. Scholars noted instead that in French — and also in the obviously related Italian poltrone — the word didn’t just mean a coward but also someone who wallowed in sloth and idleness. This led them to believe that it originated in Italian poltro, a couch, an etymology respectable enough to be cited in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Today’s Oxford etymologists are sure both stories are wrong. They point instead to the classical Latin pullus for the young of any animal, particularly a young domestic fowl or chicken. It’s the source also of pullet and is related to poultry and — more distantly — to foal. The link is an ancient reference to the notoriously timorous and craven behaviour of farmyard fowl.

So a poltroon is chicken. How appropriate.

Language barriers? The impact of non-native English speakers in the classroom

Hima2303barriers. of a different kind, though.

Are children who are non-native speakers making education worse for native speakers? Presenting new research on England, this column uses two different research strategies showing that there are, in fact, no spillover effects. These results support other recent studies on the subject. The growing proportion of non-native English speakers in primary schools should not be a cause for concern.

Full Article: Language barriers? The impact of non-native English speakers in the classroom

To Satiate The World’s Demand For Cell Phones, We’re Turning New Zealand’s Pristine Coast Into A Strip Mine

AUCKLAND, New Zealand — Underneath the ocean floor there are vast, hard-to-reach quantities of oil and gas deposits, but what about the ocean floor itself? Turns out oceans are likely to be Earth’s richest repository of minerals, ranging from precious metals to uranium to large deposits of copper, zinc, iron, sulfur and more. And where there’s immense mineral deposits, there’s also immense potential for mineral wealth.

AUCKLAND, New Zealand — Underneath the ocean floor there are vast, hard-to-reach quantities of oil and gas deposits, but what about the ocean floor itself? Turns out oceans are likely to be Earth’s richest repository of minerals, ranging from precious metals to uranium to large deposits of copper, zinc, iron, sulfur and more. And where there’s immense mineral deposits, there’s also immense potential for mineral wealth.

Many of these minerals are used to make the components of modern life — cell phones, computers, solar panels, even steel. So as long as consumption and economic growth remain key pillars of globalization, seabed mining stands to increase in prominence. The potential of mining the ocean floor has been known for several decades, but the technology to make this a feasible economic reality is just now coming online.

A relatively new industry, the first commercial seabed mining operation was granted to Canadian firm Nautilus by the Papua New Guinea government in 2012 to extract copper, gold and silver from the floor of the Bismarck Sea. The United Kingdom is also at the forefront of this underwater frontier, with PM David Cameron choosing American defense company Lockheed Martin Lockheed Martin earlier this year to spearhead the country’s drive to collect rare earth minerals.

According to a recent Greenpeace report:

A growing number of companies and governments — including Canada, Japan, South Korea, China and the UK — are currently rushing to claim rights to explore and exploit minerals found in and on the seabed. There are currently 17 exploration contracts for the seabed that lies beyond national jurisdiction in the deep seas of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans, compared with only eight contracts in 2010.

The Greenpeace report states that only three percent of the oceans are protected and less than one percent of the high seas, making them some of the least protected places on Earth. And the protection is also one of the most legally vague, which explains why companies are sticking to exclusive economic zones surrounding land and within the legal ambit of a national authority. Seabed mining beyond a country’s territorial waters is regulated by the International Seabed Authority, set up under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

CREDIT: KASM

Much like the case with hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking,’ the science and research necessary to establish the safety and overall impacts of seabed mining is lagging behind the rush to profit from it. There are a number of methods of extraction, ranging from large robotic machines excavating deep-sea hydrothermal chimneys to seabed vacuums. These technologies are untried on a commercial scale up to this point, and public opposition to the first commercial scale project off Papua New Guinea remains strong, largely based on the environmental uncertainties.

As the industry marches forward into uncharted territory, the Southwest Pacific is one of the focal points. Recently Mark Brown, Cook Islands’ finance minister, said seabed mining has the potential to increase the 15-island archipelago’s gross domestic product by a hundredfold.

Brown also said the potential income for the Cook Islands could be so vast that a sovereign wealth fund would be set up to manage the cash for future generations and provide a safety net if the islands are swamped by rising sea levels as a result of climate change.

In Australia, the Northern Territory government faces a looming court battle with BHP Billiton and two other companies over its surprise June decision to impose a ban on seabed mining following years of pressure from the local Indigenous community.

New Zealand’s government has also been enticed by the possibility of financial gain from seabed mining, with nearby undersea volcanoes providing the necessary mineral riches. One such area is the North Island’s west coast, where the iconic beaches are made up of purple and black sand, part of which is iron. This same iron is found in an even greater amount in the nearby seabed.

According to Kiwis Against Seabed Mining, or KASM, these iron sands could be New Zealand’s biggest resource, covering nearly 480 kilometers of coastline and 20,000 square kilometers of seabed in layers up to 30 meters deep.

Trans Tasman Resources has applied for a mining permit with New Zealand Petroleum & Minerals and hopes to have a 65-square-kilometer mining permit in the area by the end of 2014. Trans Tasman Resources is about 97 percent foreign-owned, although the company has registered itself in New Zealand, and placed one New Zealander on its board of directors, former Prime Minister Jenny Shipley.

The company is aiming to apply for marine permits to the Environmental Protection Authority in October.

The iron sands of Piha Beach, 40 kilometers from Auckland, New Zealand. Seadbed mining could potentially disrupt the renowned surf at this coveted surfing spot.

Cindy Baxter, an environmental activist and consultant, lives in the small coastal town of Piha, about a 45-minute drive from Auckland. “The government set up the Environmental Protection Authority to fast track applications like this because essentially they were getting bogged down in regional councils where they could be taken to court and get appealed and it could take years,” she explained. “So the EPA was created so they can call it a special project, and it gets one hearing for public input and can only be appealed on points of law.”

According to Baxter, this also means small activist groups, like KASM, can have their applications court challenged by the opposition on the basis that they won’t be able to pay the legal costs if they lose. So the big companies gain significant legal advantage over the public and small communities up and down the coast based on their financial status.

Baxter has been involved in a number of campaigns against environmental degradation and natural resource exploitation over the years, but this is the first time she’s been personally caught in the cross-hairs.

“If you take hundreds of millions of tons, literally, of sand, off the sea floor and dump a lot of it back again it’s a big question mark really,” Baxter remarked during an interview in her bungalow house nestled in the lush forest above the beach. “The modeling just hasn’t been done. And there’s so many different things that could be affected by this. Fishing. The iconic beaches. And the Maui’s dolphin.”

The Maui’s dolphin is one of the world’s rarest and smallest dolphins, with only around 50 of them remaining in the wild off the west coast of New Zealand. The New Zealand government recently proposed widening a ban on the use of large fishing nets in the region to help protect this critically endangered species while at the same time supporting seabed mining.

Baxter said that as soon as coastal residents hear about the proposed mining they are appalled. Earlier this year local children gathered and created their own protest video with the support of KASM.

Nathan Argent is the Policy Advisor for Greenpeace New Zealand based in Wellington, the capital. In an interview at a local cafe he said, “Let’s just pause for thought. We can take assurance from industry that everything is going to be alright. If you think about the industrialization of our seabed and the potentially negative impact it could have on those marine ecosystems, before we race headlong into this, we need to think about generating a body of evidence that says this is going to be alright. And we don’t have that at the moment.”

Argent thinks we need a moratorium on seabed mining until better baseline studies can be established, and even then, it should be approached with caution. “In the same way we wouldn’t allow loggers or oil companies to go into our national parks,” Argent said. “There’s some really pristine environments in the seabed around New Zealand, we shouldn’t give them up too quickly.”

The post To Satiate The World’s Demand For Cell Phones, We’re Turning New Zealand’s Pristine Coast Into A Strip Mine appeared first on ThinkProgress.

Trees Are Speeding Up Their Life Cycles To Try To Keep Up With Climate Change

CREDIT: Shutterstock

A new study has shed light on climate change’s effect on trees.

The study, led by Duke biologists and published Wednesday in Global Change Biology, found that many trees aren’t shifting their ranges northward in response to warmer temperatures as quickly as was previously expected. The study looked at 65 different species in 31 eastern states, and found that 80 percent of the species weren’t yet shifting their ranges to higher latitudes. Instead, the trees were speeding up their life cycles, with younger trees replacing older trees at a higher rate.

The study’s findings suggest that most young trees have higher optimal temperature and precipitation levels than older trees, which means they thrive more in warmer, wetter climates than older trees do. That, coupled with longer, wetter growing seasons which encourage growth and competition among older trees are likely reasons why trees are staying put and speeding up their life cycles rather than spreading farther north.

The findings back up results from a 2011 study done by the same team of Duke researchers that found about 58 percent of tree species studied showed a pattern of range contraction rather than expansion in response to climate change, and only about 20 percent of trees are showing a consistent northward shift in range. But at first glance, the study’s findings seem to contradict recent studies done in the western U.S. that have found evidence that desert plants are expanding their ranges upslope as climate warms.

James Clark, a co-author of the Duke study, said the two studies are more compatible than they seem. Temperature gradients are steep in mountains — a region a few miles upslope could be a markedly cooler environment environment than than one at a base of a mountain. So plant migration up mountains can occur quickly, because even if seeds are dispersed a short distance upslope, they could grow up in a much cooler environment. Clark said many regions — specifically in the eastern states, where his study focused — are mostly flat, without much area at high elevation. For that reason, it isn’t surprising that plants in mountainous regions are able to move upslope in response to higher temperatures, while many eastern trees haven’t adapted in that way.

“Small changes in temperature translate to large distances in latitude,” he told ThinkProgress in an email. “For this reason, evidence of migration up mountains does not mean that species can necessarily keep up with climate in flat areas.”

Overall, the Duke study and other research suggests the future looks uncertain for trees. Some, like the giant sequoia and coast redwood, seem to be adapting fairly well so far, but others face major climate-fueled challenges, including expanding regions for pine beetles, wildfires and drought.

The post Trees Are Speeding Up Their Life Cycles To Try To Keep Up With Climate Change appeared first on ThinkProgress.

What if a typical family spent like the federal government? It’d be a very weird family.

Hima2303analogy

The Heritage Foundation wants us to consider an analogy:

The idea here seems to be that the U.S. government is taking on a lot of debt. True, the typical American family also takes on a lot of debt through mortgages and the like, but U.S. government borrowing is even more massive than that.

Fair enough. This analogy seems incomplete, though. We should take it further. If the typical family — let’s call them the Smiths — really did spend like the federal government, a few other things would also be true:

– The Smiths would spend 20 percent of their income, or $10,440 each year, on an arsenal of guns, tanks and drones to defend their house against threats or invade the occasional neighbor over lawn-pesticide disputes and access to the gas station.

– The Smiths would spend another third of their income financing retirement and health care for Grandma and Grandpa. Part of that would have been prepaid by money that Grandma and Grandpa socked away while they were working, but some of it would be paid for by the parents and kids who are chipping in.

– Actually, come to think of it, the Smiths spend nearly half their money — 43 percent — operating a massive insurance conglomerate whose main beneficiaries are family members.

– Over the past few years, the Smiths have been able to borrow a vast amount of cash at negative interest rates. That is, banks have essentially been paying the family to hold their money. That’s partly because everyone assumes the Smiths are more or less immortal and will always be good for it. Plus they have all those tanks.

– The Smiths, by the way, own their own printing press. For whatever reason, it’s totally legal for them to print more money, although they have to be selective about this.

– Of the $312,000 that the Smith parents have borrowed so far, about 47 percent of that is owed to outsiders, including the Chens down the street. But much of the rest they borrow from their kids with a promise to repay.

– The parents could also tap into the kids’ extra income from their lucrative million-dollar lemonade stand business if they wanted to whittle down the debt, although this would come up for a family vote and the kids aren’t keen on this.

Anyway, it’s a good analogy. The U.S. federal government really does resemble your typical money-printing family that owns lots of tanks, operates a giant insurance conglomerate, can borrow money at extremely low rates, and is assumed to be immortal.

An Inside Look At Living In One Of The World’s Most Sustainable Cities

Hima2303sustainable

The future site of the 5×4 House.

CREDIT: Ralph Alphonso

MELBOURNE, Australia — Melbourne is a sprawling network of neighborhoods, trams, trains, bikes, laneways and, around almost every corner, coffee shops — a bit like Portland, Oregon but bigger, more European feeling and with giant bats. There are tall skyscrapers, Robert Moses-era public housing blocks, dense row houses, overgrown bungalows and suburban complexes.

Over 15 years ago, Melbourne mounted a long-term campaign to change the way it uses energy and has attracted international acclaim for its commitment to sustainability. This has included encouraging bike riding and public transport and improving building efficiency. One notable example of this is the Council House 2 building, Australia’s first six-star green star new office design building. Completed in 2006, some of the building’s features include recycled water use, automatic windows, sun-tracking facades for shade and roof-mounted wind turbines to draw out hot air.

While good public transport and efficient office buildings are a big part of being a sustainable city, residences — and the way people live in those residences — are likely just as important. Melbourne is only as sustainable as its Melbournians.

A person’s carbon footprint, or energy economy, is some combination where they live and how they live. Two forward-thinking approaches to this idea in Melbourne are the 5×4 House, a soon-to-be-built super energy efficient, zero carbon dwelling on a 5×4-meter plot of land, and the Murundaka Co-housing Community, a new eco-housing complex of 20 residences based on the principles of sustainable and community living.

Different Approaches To Sustainability

Heidi Lee and her partner sit at table in the Murundaka community room area.

Design and Technology

Ralph Alphonso, a Melbourne-based photographer, is building the 5×4 House on the space occupied by his garage. His current residence is a large, modern condo is located down a small laneway, or alley, in East Melbourne. He decided to go all out and try to build Australia’s most sustainable dwelling after being somewhat disappointed in the construction practices used in building his current house.

Rendering of what the structure of the house will look like.

CREDIT: Ralph Alphonso

“In Australia you find houses with one or two elements of sustainable design,” Alphonso said. “We’re using the principles of full life cycle assessment and embodied energy to reduce the total carbon emissions of the house.”

Alphonso is not an environmentalist — his emissions from flying must be in the top one percentile as he seems to be on a plane every other day (he does buy offsets) — but through this process he’s become much more aware of what it means to live sustainably. For him, this includes everything from eating less meat to sourcing local materials.

“I think the house will start changing my behavioral patterns,” Alphonso said. “A big part of sustainable living is actually living the lifestyle.”

For Alphonso, the project is also about education. He thinks there are three main reasons why people choose to live more sustainably: it doesn’t take a large economic toll, it doesn’t alter their lifestyle too much and they are educated and can make informed decisions.

Cost is a major issue with employing sustainable design, and Alphonso has gotten creative about this by establishing project partners who offer services or products at a reduced cost in or in-kind in exchange for exposure (such as this article). He sees the true value-added being in the comprehensive nature of the project.

“Manufacturers are only going to change their production patterns if there’s a demand for it,” Alphonso said. “We want to showcase sustainable products and create that demand so manufacturers will automatically include sustainability, recycled content, efficiency — all those sort of things — in their production decisions. Then, in the longer term, these products will be more available and more affordable.”

As for lifestyle, Alphonso won’t be sacrificing much. He’ll even have a hot tub on the roof, which will be geothermally heated through partner agreements with Bosch Geothermal and Direct Energy Geothermal Heating and Cooling. While the footprint of the house is small, the square footage is around 650 feet (three floors, not including the roof), not too shabby for one person. He explains that part of the reason he’s doing this is to show that it’s possible to maintain a high quality of life while significantly reducing your energy economy.

Another reason is to illustrate how dense, urban living doesn’t have to feel cramped. Alphonso used his frequent travels abroad to visit some of the densest cities in the world, including New York and Tokyo, to gather ideas for his house. Both the City of Melbourne and the Australian Conservation Foundation are supporters of the project.

Alphonso is using the One Planet Living principles as a guide to building a more sustainable life along with the house. He likes the One Planet Living concept because it’s holistic and it’s quantifiable by showing how many planets of resources we consume to sustain our lifestyle.

August 20 was Earth Overshoot Day 2013: the day humanity uses up all the natural resources the planet can sustainably provide for a given year. From that date on, we’re in ecological deficit for the rest of the year, inflicting more damage on global ecology than it can naturally repair. Every year this date moves forward at least a few days.

“Ecological footprint analysis shows that, if everyone in the world lived like the average Australian, we would need five planets to sustain us,” Alphonso said.

Community

“I like a lot of what the 5×4 House is doing, especially with the embodied energy analysis and One Planet Living guidelines,” Heidi Lee, Future Projects Manager for the architecture firm DesignInc and Murundaka Co-housing Community resident, said.

CREDIT: www.footprintnetwork.org

“But I think it kind of misses the point,” Lee continued. “I feel like we’re not really making much ground if we’re going to keep on knocking things down and building something new and keeping the same area and everyone having a hot tub.”

Lee said there’s a lot of talk about hot tubs where she lives as well, but it’s about sharing one hot tub between twenty households.

The Murundaka Co-housing Community consists of 18 self-contained apartments centered around a common house. As a rule of thumb, the apartments are ten percent smaller than what’s on the market — ten percent that gets put into the common house and other shared spaces, such as an office, guest room and expansive garden.

The building is only about two years old and has large, open corridors and panel windows that give it a very welcoming and homey feel for being so large. It is a mix of families, single moms, young couples and individuals, with all different apartment sizes. It is affordable housing so it is rent controlled. They have voluntary group activities, occasional meals, and as of recently, a weekly moderation session to improve communication.

“As a microcosm of how we could live in suburbia this has been built intentionally for people to actively live and work together,” Lee said. “To share time with neighbors, although you could live totally independently and never talk to any of the community members if you didn’t want to.”

But that would also miss the point, according to Lee, which is to rediscover the kinds of things humans lost when they stopped living in the size of settlements where people could know each other and have a certain level of trust and reciprocity even with the people they might not know that well. Lee and her partner recently had a child and she said that the community support surprised even her, with members helping with everything from preparing meals to running errands.

While Alphonso sees his main contribution being to change the way new buildings are manufactured, Lee is more concerned with what’s already standing. According to her, about 80 percent of the structures that will be around in ten years are already built.

“We need to put effort into looking after and improving what’s already built,” Lee said. “Otherwise it’s only going to get worse. Old buildings often have high air infiltration, leaking around windows and doors and other energy-wasting problems.”

The Larger Landscape

View of the Murundaka Cohousing Community from the backyard.

In June, Melbourne and Sydney launched a new program called Smart Blocks, designed to help apartment owners and their managers save money by improving energy efficiency. Energy audits show that on average up to 30 percent can be saved on just power bills alone.

In an interview, City of Melbourne Environment Portfolio Chair Councilor Arron Wood said population growth needs to be supported by innovative and practical initiatives like Smart Blocks.

“Our population is growing quickly. By 2031, we expect an additional 42,000 homes will be built in the City of Melbourne, accommodating 80,000 people. We need to be smart about the way we develop in the future but we also need to make our existing buildings more efficient. This is a critical step to reaching our ultimate goal of becoming a carbon neutral city.”

To Lee, however, just maintaining the existing suburban home infrastructure totally misses the point as well. She shudders at the thought of the nearly 70 percent of Australian dwellings with a spare bedroom, or large, underutilized yard space.

“Overall a key part of the message is missing: that we have to be living better together,” Lee said.

In Melbourne, and even across Australia, some of these ideals may be within reach. Approximately 40 percent of all new housing in Australia is in medium to high density developments. Over 70 percent of residents in both Melbourne and Sydney live in apartments, and these figures are only set to grow.

The transition from dense living to community living is not to be taken for granted though. While living in smaller spaces may cause people to spend more time outside at cafes or in public parks, which Alphonso plans to do, the idea of cooperative living is still in its infancy in Australia.

Lee recently toured cooperative housing communities in the States, and she was surprised that most of the communities she saw were doing it for social reasons. “In Australia the idea of a co-housing community is still pretty left-wing, and gets lumped in with other lefty ideals: less environmental impact, shared resources, growing your own food,” Lee said. “What I saw in the U.S. influenced how I think of it more as a social experience now.”

Lee would also like to see more collaboration — or more sharing — within the industry, and for the manufacturing and construction bar to be raised to higher energy economy standards. Amongst other things, this involves prefabrication or modular techniques that cut down on energy and transportation demands.

“What I worry about is we’re all going to sit back and go on with a business-as-usual approach,” Lee said. “Many firms just do whatever the client says, no matter what the carbon impact of the decision. We could be doing so much more and providing leadership.”

Lee has only been Future Projects Manager for a few weeks, but this is the type of impact she hopes to have going forward. And with clients like Alphonso, it seems likely that Melbourne will build on its reputation as one of the world’s most livable and sustainable cities.

The post An Inside Look At Living In One Of The World’s Most Sustainable Cities appeared first on ThinkProgress.

Proportion of adjectives and adverbs: Some facts

Hima2303;)

Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn, "Cluttered writing: adjectives and adverbs in academia", Scientometrics 2013:

[H]ow do we produce readable and clean scientific writing? One of the good elements of style is to avoid adverbs and adjectives (Zinsser 2006). Adjectives and adverbs sprinkle paper with unnecessary clutter. This clutter does not convey information but distracts and has no point especially in academic writing, say, as opposed to literary prose or poetry.

If you've seen my earlier discussion of this paper ("'Clutter' in (writing about) science writing", 8/30/2013), you'll recall that Dr. O-K goes on to count adjectives and adverbs in some word lists from samples of scientific writing. He asserts that "social science" writing uses about 15% more adjectives and adverbs than "natural science" writing — although he doesn't tell us enough about his methods to dispel concerns about several likely sources of artifact — and he concludes by asking "Is there a reason that a social scientist cannot write as clearly as a natural scientist?"

In the interests of science of all kinds, I decided to devote this morning's Breakfast Experiment™ to the relations between text quality and the proportion of adjectives and adverbs. I wrote a python script using NLTK to calculate the proportions of various parts of speech in a document; and then I tried this script out on samples of various sorts of writing. Here's some of what I found.

To start with, I decided to try some really cluttered prose, prose that is not at all "readable and clean": Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Paul Clifford. Wikipedia tells us that this novel is considered to represent 'the archetypal example of a florid, melodramatic style of fiction writing'". Its first sentence:

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents, except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the house-tops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

I put essentially all of the first chapter of this work into a file (minus the paragraphs that are mostly dialogue, much of which is in dialect). According to NLTK's pos_tag() function, which should be about 95% correct, the score was:

1775 words, 184 punctuation tokens = 1591 real words

108 adjectives = 6.8 percent

78 adverbs = 4.9 percent

186 adjectives+adverbs = 11.7 percent

So Bulwer-Lytton's chapter is about 12% adjectives and adverbs. What should we compare this to? Well, Dr. O-K cites William Zinsser's On Writing Well as his authority for the cluttering nature of adjectives and adverbs, so let's try the first three sections of that work (minus quotations from others, of course):

3939 words, 439 punctuation tokens = 3500 real words

241 adjectives = 6.9 percent

208 adverbs = 5.9 percent

449 adjectives+adverbs = 12.8 percent

Hmm. Well, maybe this is experimental error. And Bulwer-Lytton's writing is clear enough, it's just kind of overwrought. So let's take a look a something by Jacques Derrida, whose prose is about as unreadable as anything I've ever encountered. Here's the score for chapter 2 of "Of Grammatology" (in English translation, of course):

19239 words, 2105 punctuation tokens = 17134 real words

1434 adjectives = 8.4 percent

946 adverbs = 5.5 percent

2380 adjectives+adverbs = 13.9 percent

OK, that's better — Derrida has 19% more adjectives and adverbs than Bulwer-Lytton. But he's only got 8% more than Zinsser, and Zinsser has more than Bulwer-Lytton, so this still doesn't all seem to be working out the way we were told it would.

Let's go for another paragon. Dr. O-K opens his paper with a quote from Mark Twain: "When you catch an adjective, kill it." So let's try the whole letter that the quote came from:

1474 words, 170 punctuation tokens = 1304 real words

89 adjectives = 6.8 percent

95 adverbs = 7.3 percent

184 adjectives+adverbs = 14.1 percent

Oops. We're really going in the wrong direction here — Saint Mark uses the highest proportion of adjectives and adverbs that we've seen so far.

And what about Dr. O-K's own writing? Here's the score for the text of "Cluttered writing: adjectives and adverbs in academia" itself (of course minus the quotations from others):

883 words, 80 punctuation tokens = 803 real words

85 adjectives = 10.6 percent

42 adverbs = 5.2 percent

127 adjectives+adverbs = 15.8 percent

We have a winner! Dr. Okulicz-Kozaryn's text, about the importance of eliminating adjectives and adverbs from prose, has fully 35% more adjectives and adverbs than the infamous "It was a dark and stormy night" passage, which has given its author's name to an annual bad writing contest!

(127/803)/(186/1591) = 1.3528

And the first two pages of another of his papers ("Man and God and Circle of Trust", 2012) score even a bit higher:

1121 words, 104 punctuation tokens = 1017 real words

113 adjectives = 11.1 percent

60 adverbs = 5.9 percent

173 adjectives+adverbs = 17 percent

Seriously, the problem is not in Dr. O-K's writing (despite the sprinkling of slavicisms), but in his ideas. Calculating the relative percentages of adjectives and adverbs in texts tells us nothing useful about their readability, clarity, or efficiency.

I'll spare you the reports for the other 45 texts that's I've tested. But just to let Dr. O-K off the hook for the "most modifiers" prize, let me note that the text of Ben Yagoda's piece from the Chronicle of Higher Education on adjectival anxiety ("The Adjective — So Ludic, So Minatory, So Twee", 2/20/2004), beats him out:

1908 words, 301 punctuation tokens = 1607 real words

208 adjectives = 12.9 percent

86 adverbs = 5.4 percent

294 adjectives+adverbs = 18.3 percent

Finally, I need to point out that there's a technical flaw in the whole "avoid adjectives and adverbs" idea — nouns are often modified by other nouns, or by prepositional phrases, or in other ways that don't involve adjectives; and verbs are often modified by prepositional phrases, subordinate clauses used as verbal adjuncts, and so on.

If it were true, counterfactually, that modification in general was a Bad Thing, then we'd need to count these other sorts of modifiers as well, not just adjectives and adverbs.

Some of the previous LL posts on modificational anxiety:

"Those who take the adjectives from the table", 2/18/2004

"Avoiding rape and adverbs", 2/25/2004

"Modification as social anxiety", 5/16/2004

"The evolution of disornamentation", 2/21/2005

"Adjectives banned in Baltimore", 3/5/2007

"Automated adverb hunting and why you don't need it", 3/5/2007

"Worthless grammar edicts from Harvard", 4/29/2010

"Getting rid of adverbs and other adjuncts", 2/21/2013

"'Clutter' in (writing about) science writing", 8/30/2013

N.B. Someone who took this whole business seriously enough to want to look at differences in part-of-speech distributions among scientific disciplines should know that Okulicz-Kozaryn is wrong when he writes that

as of 2012 I cannot bulk download enough full texts to have a representative sample of a discipline.

Between arXiv, the PLoS collections, SSOAR, the resources available from the ACL, and so on, it would not be hard to create large enough samples in enough different disciplines and subdisciplines to engage the question more seriously than Okulicz-Kozaryn did. But you ought to have another hypothesis to test as well, in my opinion, because the modifier-percentage idea looks like a loser.

Update — I realize that it's only fair for me to report the score for this blog post. Leaving out the quotations and so on, and without this update, I get:

1143 words, 146 punctuation tokens = 997 real words

82 adjectives = 8.2 percent

59 adverbs = 5.9 percent

141 adjectives+adverbs = 14.1 percent

The same overall percentage as Mark Twain…

Update #2 — William Zinsser complains that

Clutter is the disease of American writing. We are a society strangling in unnecessary words, circular constructions, pompous frills and meaningless jargon. Who can understand the clotted language of everyday American commerce: the memo, the corporation report, the business letter, the notice from the bank explaining its latest “simplified” statement?

So I decided to score Microsoft's 2012 Annual Report:

1499 words, 92 punctuation tokens = 1407 real words

117 adjectives = 8.3 percent

38 adverbs = 2.7 percent

155 adjectives+adverbs = 11 percent

There are certainly some unnecessary words and pompous frills in that report ("we delivered strong results, launched fantastic new products and services, and positioned Microsoft for an incredible future"), but the percentage of adjectives and adverbs is not a good measure of those characteristics.

Update #3 — I should also tell you that I did check the adjective and adverb proportions in various natural-science articles. For example, the first page of the first article in the current issue of Physical Review A (A. Rançon et al., "Quench dynamics in Bose-Einstein condensates in the presence of a bath: Theory and experiment") weighs in at

908 words, 62 punctuation tokens = 846 real words

103 adjectives = 12.2 percent

35 adverbs = 4.1 percent

138 adjectives+adverbs = 16.3 percent

And a combination of the first seven abstracts from the current issue of Science scores

1041 words, 81 punctuation tokens = 960 real words

106 adjectives = 11 percent

36 adverbs = 3.8 percent

142 adjectives+adverbs = 14.8 percent

This tends to confirm my suspicion that Okulicz-Kozaryn's result (15% lower proportion of adjectives and adverbs in natural science compared to social science text) probably results from one of the obvious sources of artifact, for example an inappropriate attempt to calculate part-of-speech percentages in text derived from passages like this one (from the second page of the Rançon et al. paper):

Since Okulicz-Kozaryn's counts came from word lists supplied by JSTOR, and he doesn't tell us which lists he used or how he processed them, and JSTOR doesn't tell us how they created the lists, we'll probably never know.

The ultimate earworms

Hima2303after earworms (and of course babel fish), now this

From Lev Michael at Greater Blogazonia:

I was briefly excited by the title of a recent Language Log post, Earworms and White Bears, thinking it might have something to say about, well, worms that people put in their ears. However, we immediately learn that the earworms in question are simply catchy tunes that get caught in people’s minds.

My excitement, though, stems from the fact that the Nantis of southeastern Peruvian Amazonia, with whom I have worked a bit (see here and here), actually do sometimes put worms — or more precisely, larvae — in their ears. I’ve never heard or read about any other group that makes use of larvae in this way, though, so I was momentarily hoping that Language Log would change that

The Nantis call the larvae in question magempiri, and they are one of a number of larvae that Nantis help flourish by means of a form of low-intensity animal husbandry where they puncture the trunks of the palm species in which the relevant species of beetle must lay their eggs. When the magempiri are the right size, a portion of the trunk is split open and some larvae removed, together with some of the pulp on which the larvae are feeding. The pulp and larvae are then wrapped up in Heliconia leaves, in which the larvae can live for several days.

The magempiri are used to clean one’s ears: tilting one’s head, one drops a larva into the ear canal and the magempiri then starts munching away on what it finds there, creating an incredible racket (for the temporary host), and producing a funny if somewhat gratifying ticklish feeling. When the magempiri gets full, it becomes inactive, and simply falls out of the ear canal when the user tilts his or her head the opposite way. Repeat until satisfied.

Read the whole thing, for the bonus discussion of the morphology of magempiri.

Magempiri are one of the few things that you can't yet buy from amazon.com, at least not under that name.

SpecGram—The SpecGram Linguistic Advice Collective

Hima2303:D

Where Was China?: Why the Twentieth-Century Was Not a Chinese Century: A Deleted Scene from My "Slouching Towards Utopia?: The Economic History of the Twentieth Century" Ms.

Hima2303Hmm.

Kong Shangren, as quoted by Jonathan Spence:

White glass from across the Western Seas

Is imported through Macao:

Fashioned into lenses big as coins,

They encompass the eyes in a double frame.

I put them on—-it suddenly becomes clear;

I can see the very tips of things!

And read fine print by the dim-lit window

Just like in my youth!

In 1870 a part of the world was starting to become not-poor, yet not the obvious part. The technological and organizational edge of human civilization in 1870 was the North Atlantic. That was, in historical perspective, distinctly odd.

6.1: The Britons: Too Stupid to Make Good Slaves

Two thousand years before, people would have laughed at the idea. Gaius Julius Caesar classified the Britons as among the most backward people he had ever conquered. Ex-Consul and Senior Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero snarked to his BFF Titus Pomponius Atticus about how Caesar’s invasion of Britain was completely pointless:

not an ounce of silver to be stolen, only slaves and not very good quality slaves--certainly not a single slave with a useful skill like literacy or musicianship!

A thousand years before—-in 800, say—-the technological and civilizational cutting edges of humanity were to be found in the Caliph Haroun al-Rashid’s capital of Baghdad and the Tang Dynasty Emperor Dezong’s Chang’an, rather than London or Bristol of Manchester or New York or Washington or Cleveland. Even three-hundred years earlier--back in 1570—-it would have taken a very sharp-eyed observer indeed to believe that northwest Europe was about to get its act together in a way that the Turko-Islamic Osmanli Dynasty civilization around Constantinople, the Moghul-Islamic Gurkani Dynasty Indian civilization around Delhi, and the Ming Dynasty Chinese civilization around Beijing could not.

By 1870, however, the power and technology gradients across world civilizations were very clear. Travelers from western Europe to Asia in the 1600s and before had been impressed back then not just by the scale of the empires and the luxurious wealth of their rulers but by the rest of the economy as well. The scale of operations, the prosperity and industry of the merchant classes, the good order of the people, and the absence of extraordinary poverty among the masses frequently struck European observers as worthy of comment as striking contrasts with back home. But by the 1800s this was no longer true. Travelers’ reports then focused as much on mass poverty and near-starvation as on high-craft and high-culture luxury. Assessments of the wealth of the court took on a sinister “orientalist” cast—-a cruel corrupt ruling elite that simply did not care about the welfare of the people—-when viewed against the background of the poverty of the masses.

6.2: What Had Happened to China?

The coming of the technology gradient favoring western Europe was indeed remarkably late. Before 1800 or so there was very little that European traders could offer to sell that Chinese consumers would wish to buy. For more than two thousand years China had been one of the leading, if not the leading civilization on the planet. It was not that the average standard of living was higher in China: Malthusian population pressures roughly equalized standards of living around the world. But China had a higher population density because more efficient technologies allowed a given plot of arable land to generate more food, better craftwork in most industries, a larger class of literati interested in high culture, and—-quite probably—-a significantly higher standard of living for the landed and ruling elite.

Before 1800 European trade for Chinese goods was by and large trade of silver for China-made luxuries. And the transfer of technology flowed from east to west: it is still unclear to what degree the European development of items like gunpowder, printing, the compass, and noodles owed to the Chinese example. It is clear that all of these were known in China before they were known in Europe.

6.3: China’s Relative Apogee