Tryan02

Shared posts

Class Warfare, An American Tradition

The Adoption of Proportional Representation

Lucas Leemann, Isabela Mares,

The Journal of Politics,FirstView Article(s),

Abstract

*The Sabermetric Revolution*

That is the new book by Benjamin Baumer and Andrew Zimbalist and the subtitle is Assessing the Growth of Analytics in Baseball. It is an excellent and well-written look at where sabermetric knowledge stands today, here is one excerpt:

…once the ball has been put into play, it doesn’t seem to matter all that much whether it was put into play against Roger Clemens or Roger Craig.

And:

…an extra win will bring more revenue to a team in New York City than in Kansas City.

This is a very useful book on its chosen topic.

Markets in everything

For only 23,500 euros (who says you can’t take it with you?):

Sweden’s Catacombo Sound System is a funeral casket that eternally plays the deceased’s choice of tracks while they’re six feet under.

Created by Pause Ljud & Bild, the system consists of three different parts. Firstly, users create an account through the online CataPlay platform, which connects to Spotify and enables customers to curate a playlist for their own coffin or get friends and family to choose the tracks when they’re gone. The CataTomb is a 4G-enabled gravestone that receives the music from CataPlay and display the current track — along with details and tributes to the deceased — through a 7-inch LCD Display. Finally, the CataCoffin is where the parted will themselves enjoy two-way front speakers, 4-inch midbass drivers and an 8-inch sub-bass element that deliver dimensional high-fidelity audio tailored to the acoustics of the casket. The video below explains more about the concept…

Of course I want Brahms’s German Requiem, the Rudolf Kempe recording. I am afraid, however, that I (in some form) will last longer than Spotify does.

For the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.

Editor's Comment

Four decades of classic essays . . . with gratitude.

How much is a Lars Hansen autographed reprint worth?

I'm a 1st year MBA student at Chicago Booth -- where even the Marketing Professors have a PhD in Economics.

I'm taking a class this quarter called Entrepreneurial Selling (more info here). One of the coolest assignments is a bartering challenge: Prof. Wortmann gives everybody a simple Chicago Booth pen and we need to barter it for something with larger monetary value, and then keep bartering once a week until the end of the quarter.

I did my first trade with Prof. Lars Peter Hansen (Economics Nobel Prize 2013). In exchange for my pen, he gave me an autographed copy (he wrote a cool anecdote as well) of his most famous article. I'm now running an auction at eBay (it's OK to trade things for cash): see here.

Anne Enright on plot and writing

AE: Plot is a kind of paranoia, actually. It implies that events are connected, that characters are connected, just because they are in the same book. I like the way Pynchon exposed the essential paranoia of plot in The Crying of Lot 49. When I read that book as a student, I realized that if you bring coincidence or the mechanics of plotting into a book, it begs all the questions about who is writing this book and why, or why you’re making this mechanical toy do these things. That, to me as a reader, is slightly alienating. But, you know, things do happen in real life. People die in car accidents. There are connections and coincidences.

She is an Irish writer, there is more here, interesting throughout. I also liked this sentence:

The unknowability of one human being to another is an endless subject for novelists.

And this bit about writing:

It’s like getting a herd of sheep across a field. If you try to control them too much, they resist. It’s the same with a book. If you try to control it too much, the book is dead. You have to let it fall apart quite early on and let it start doing its own thing. And that takes nerve, not to panic that the book you were going to write is not the book you will have at the end of the day.

Hat tip goes to The Browser.

From the comments, on being a government economist

DC Economist writes:

I am in this cohort of economists (although ashamedly a non-responder to the NSF SED survey – I filled it out but neglected to mail it). And I did chose a government job over an academic offer and I’ve never been sorry that I did.

All my academic offers (2002) were from public institutions, mostly on the west coast and mid-west. For the next five years of my career, almost all of those departments had pay freezes. Meanwhile, I was quickly promoted in my government job. While the cost of living in DC eats a comfortable share of that salary differential, it was decidedly better financial move in retrospect to take the federal job. (I did not know that ex ante; my federal starting salary was actually lower than the starting pay for my best academic offer, and I assumed I was making a financial sacrifice to take a job I genuinely preferred.)

You can make even more money in consulting, but it’s a different world, and I’ve known a fair number of economists who move back and forth between consulting and government, depending on their relative preference for money vs. interesting work. Colleagues that have moved back and forth between academia and government have often voiced to me their extreme surprise how interesting and rewarding the work can be.

I just got back from recruiting at the AEAs and as always, I remain truly surprised how strongly candidates prefer academic jobs to government work. Academic jobs often have serious drawbacks — geography, teaching, collegiality (the incentives are stronger for us to all get along on this side of the market), the gut-wrenching uncertainty of the tenure track. Government jobs often offer better opportunities to do research (especially empirical work) and find similar co-authors. DC is also a great place to be an economist – lots of jobs, lots of interesting work – and the policy work is often more rewarding than teaching can often be. The one serious drawback is a lack of sabbaticals and summer research time. I often groan at the inevitable co-author email flood in May – let’s get back to our paper! – while I’m still working as hard in June as I was in March. But that’s not enough to tempt me back to academia – I’m much, much happier here.

But every year I offer a job to a junior candidate who turns me down for a really marginal academic job. I understand being turned down for a good-to-great academic offer, but turning this job down for a really marginal academic department makes no sense at all to me. And yet so many junior candidates can’t seem to imagine themselves in another line of work that they torpedo their own research opportunities to take a lower-paying, high-teaching load, academic job. Maybe they are just not that into research, and would rather have their summers off than be placed somewhere where they will work harder but have better opportunities for research. Or maybe they worry that all government jobs are being some boring government bureaucrat and they can’t see past that initial bias (those jobs do exist, but those agencies aren’t often looking for Ph.D. economists at AEAs to fill them).

Graduate students really should be more strongly considering some of the great government jobs in the DC area. You really can have a great, rewarding career here.

Interview with John Cochrane

There are many interesting bits from the interview, sometimes polemic bits too, here is one excerpt:

EF: What do you think are the biggest barriers to our own economic recovery?

Cochrane: I think we’ve left the point that we can blame generic “demand” deficiencies, after all these years of stagnation. The idea that everything is fundamentally fine with the U.S. economy, except that negative 2 percent real interest rates on short-term Treasuries are choking the supply of credit, seems pretty farfetched to me. This is starting to look like “supply”: a permanent reduction in output and, more troubling, in our long-run growth rate.

This part reminds me of some ideas in my own Risk and Business Cycles:

There is a good macroeconomic story. In a business cycle peak, when your job and business are doing well, you’re willing to take on more risk. You know the returns aren’t going to be great, but where else are you going to invest? And in the bottom of a recession, people recognize that it’s a great buying opportunity, but they can’t afford to take risk.

Another view is that time-varying risk premiums come instead from frictions in the financial system. Many assets are held indirectly. You might like your pension fund to buy more stocks, but they’re worried about their own internal things, or leverage, so they don’t invest more.

A third story is the behavioral idea that people misperceive risk and become over- and under-optimistic. So those are the broad range of stories used to explain the huge time-varying risk premium, but they’re not worked out as solid and well-tested theories yet.

The implications are big. For macroeconomics, the fact of time-varying risk premiums has to change how we think about the fundamental nature of recessions. Time-varying risk premiums say business cycles are about changes in people’s ability and willingness to bear risk. Yet all of macroeconomics still talks about the level of interest rates, not credit spreads, and about the willingness to substitute consumption over time as opposed to the willingness to bear risk. I don’t mean to criticize macro models. Time-varying risk premiums are just technically hard to model. People didn’t really see the need until the financial crisis slapped them in the face.

I’ve long believed the risk premium is the underexplored variable in macroeconomics and finally this is being rectified.

Assorted links

1. How are some select people younger than thirty changing the world? A photo gallery, with explanations.

2. German storage markets in everything: “Rather than taking up the limited space available for hand luggage with bulky winter coats, Frankfurt Airport is allowing customers to check in their jackets for a small fee.”

3. The importance of being first in your class (pdf).

4. “The referendum in Catalonia will be held less than a month after a similar vote in Scotland…”

5. Cliff paths. And The Thin Airport (Marshall Islands).

6. New Republic best books list.

South Africa and Ending Apartheid: W. H. Hutt and the Free Market Road Not Taken

by Richard M. Ebeling*

The public eulogies marking the passing of Nelson Mandela at the age of 95 on December 5, 2013 have refocused attention on the long struggle in South Africa to bring about an end to racial discrimination and the Apartheid system.

Forgotten or at least certainly downplayed in the international remembrance of Mandela’s nearly three decades of imprisonment and his historical role in becoming the first black president of post-Apartheid South Africa is the fact that through most of the years of his active resistance leading up to his arrest and incarceration he accepted the Marxist interpretation that racism and racial discrimination were part and parcel of the capitalist system.

Mandela was a member of a revolutionary communist cohort who were insistent and convinced that only a socialist reorganization of society could successfully do away with the cruel, humiliating, and exploitive system of racial separateness.

With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the communist model of socialist transformation was too tarnished and delegitimized to serve a as a guidebook for post-Apartheid South Africa by the time that Mandela assumed office as the first black president in that country in May 1994.

Instead, Mandela’s government followed the alternative collectivist path of a highly “activist” and aggressive interventionist-welfare state, with its usual special interest politicking, group-favoritism, and its inescapable corruption and abuse of power. Its legacy is the sorry and poverty-stricken state of many of those in the black South African community in whose name the anti-Apartheid revolution was fought.

But this did not have to be the road taken by South Africa. There were other voices that also opposed the racial and Apartheid policies of the white South African government, especially in the decades after the Second World War.

These voices argued that racial policies in that country were not the result of “capitalism,” but instead were precisely the product of anti-capitalist government interventionism to benefit and protect certain whites from the potential competition of black Africans.

One of the most prominent of these voices was economist, William H. Hutt. Hutt had come to South Africa from Great Britain in 1928 and taught at the University of Cape Town until the 1970s, when he moved to the United States where he died in 1988. Born in 1899, he had attended the London School of Economics and studied under Edwin Cannan, the noted historian of economic thought and liberal free trade economist.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Hutt became most widely known in free market and classical liberal circles as an outspoken and tireless critic of Keynesian economics and an advocate of a liberal free market order.

But his notoriety in South Africa was due to his well-reasoned and biting criticisms of government economic policies to “keep blacks in their place.” Indeed, in the mid-1950s, Hutt was threatened with expulsion from the country as a result of his criticisms until the matter was brought up in the South African parliament, and his right of residence and freedom of speech were defended.

His criticisms culminated in a 1964 book, The Economics of the Color Bar. The thesis of the book was that South Africa’s “race problem” was due to the rejection of a liberal, open and competitive market economy. Black poverty and the income inequality between South African whites and blacks was caused by government regulation and prohibitions that bestowed privileges on segments of the white, and especially Afrikaner, population at the expense of unprivileged blacks who were prevented from competing for employment and opening businesses in restricted “white-only” parts of the economy.

These discriminatory laws began to be implemented in the early decades of the 20th century. Under “workplace fairness,” for example, white trade unions had pushed for legislation requiring for “equal pay for equal work.” But, in fact, such laws made it difficult for blacks to offer themselves at more attractive wages than their white competitors. This worked like a minimum wage law that prices lower skilled and less valuable workers out of the market. In the South African case, the burden of exclusion from employment fell almost completely on blacks.

In his book Hutt traced out the history of how the Afrikaners, who had originally come from Holland and had first settled in South Africa early in the 1600s, were mostly farmers who shunned manufacturing and commercial enterprise. These latter occupations and businesses were mostly formed and developed by later settlers from Great Britain.

But as circumstances changed over time in the 19th and early 20th centuries, with industrial development and the growth in mining, Afrikaners reluctantly found themselves moving into these lines of employment. However, they resented and feared the potential competition from black Africans also looking for employment, and who might be more industrious than themselves or willing to work for lower wages.

The labor market restrictions were exacerbated in the post-World War II period when the Afrikaner-led Nationalist Party came to power in 1948 and instituted the Apartheid policy of keeping the races separate by restricting entire professions and occupations or forms of employment for white workers only.

In addition to occupational segregation, Apartheid attempted to limit black residence and settlement to certain parts of South Africa, which included restrictions on the everyday movement of blacks within white areas.

Hutt called this a form of “totalitarian” control so the government could “centrally plan” the interactions, associations and movements of whites and blacks throughout the country. Contrary to the leftist propaganda of the time, many private businesses in South Africa were interested and willing to employ black workers and invest in their training and acquisition of more highly valued marketable skills.

However, the Afrikaner government used its regulatory and fiscal tools of control and intimidation to “keep in line” white employers who saw economic gain by “crossing the color line” in their businesses and enterprises.

Thus, it was political goals of the South African government and not the market motive of profit that prevented black South Africans from having the opportunities to rise more out of poverty through peaceful competition and cooperative commercial association.

Hutt forcefully insisted that capitalism was the potential and real force for freedom and prosperity of the blacks in South Africa, if only the government would get out of the way. As Hutt expressed, it in the free market the only “color” that really matters is the color of your money:

“The liberating force is released by what is variously called ‘the free market system,’ ‘the competitive system,’ ‘the capitalist system’ or ‘the profit system.’ When we buy a product in the free market, we do not ask: What was the color of the person who made it? Nor do we ask about the sex, race, nationality, religion or political opinions of the producer.”

“All we are interested in,” Hutt continued, “is whether it is good value for money. Hence it is in the interest of businessmen (who must try to produce at least cost in anticipation of demand) not only to seek out and employ the least privileged classes (excluded by custom and legislation from more remunerative employments) but actually to educate them for these opportunities by investing in them.

“I have tried to show [in his book], Hutt said, “that in South Africa it has been to the advantage of investors as a whole that all color bars should be broken down; and that the managements of commercial and industrial firms (when they have not been intimidated by politicians wielding the planning powers of the state) have striven to find methods of providing more productive and better remunerative opportunities for the non-Whites.”

What, then, was holding back opportunities for black South Africans? Hutt explained it was the political and restrictive power of government:

“The subjugating force is universally through what we usually call, when writing dispassionately, the interventionist, collectivist, authoritarian or ‘dirisgiste’ system . . . Unchecked state power (or the private use of coercive power tolerated by the state) tends, deliberately or unintendedly, patently or deviously, to repress minorities or politically weak groups. Thus, the effective color bars which have denied economic opportunities and condemned non-Whites to be ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ have all been created in response to demand for state intervention by most [of South Africa’s] political parties.”

Why would businessmen, enterprisers, capitalists have any incentive or motive to overcome what might even be their own racial or ethnic prejudices and hire and train those in the discriminated group?

Hutt said that it was due to what he once called “consumers’ sovereignty.” That is, in a competitive, open and free market, there is only one way that a businessman may earn profits and gain market share: Making the better and less expensive product than his rivals who are also attempting to capture some of the consumers’ business. In the free market place, the consumer is the “master” and the producers are the “servants” who must satisfy the consumers’ desires, or end up as failed entrepreneurs.

“The virtues of the free market do not depend upon the virtues of the men at the political top but on the dispersed powers of substitution exercised by men in their role as consumers,” Hutt stated. “In that role, a truly competitive market enables them to exert the energy [through their decisions to buy or not to buy] which enforces the neutrality of business decision-making in respect of race, color, creed, sex, class, accent, school, or income group.”

“In a multi-racial society,” Hutt continued, “it tends, because of the consumers’ color-blindness, to dissolve customs and prejudices which have been restricting the ability of the under-privileged to contribute to, and hence to share in, the common pool of output and income. This is because business decision-makers – ‘entrepreneurs’ – have an immensely powerful incentive to economize for the benefit of their customers, who collectively make up the public. Their success depends upon their acumen and skills in acquiring the resources needed for production at the least cost, especially in discovering under-utilized resources.”

Here was the free market capitalist road not taken by South Africa, both in bringing an end to the racist and Apartheid policies of the past, and in terms of the policies that could have brought about a far more color-blind, free, and prosperous South African society in the nearly twenty years since 1994.

In following the anti-capitalist ideas of Nelson Mandela instead of the classical liberal free market ideas of someone like William H. Hutt, South Africa’s post-Apartheid history has been in many ways as troubled and discriminatory as the corrupt racist regime it replaced.

*Professor of Economics, Northwood University.

Filed under: Classical Liberalism, Democracy, Development, economic history, History of Economic Thought

Assorted links

1. Eurozone industrial production: the recovery?

2. Are Chinese provinces picking up the stimulus slack?

3. Yuval Levin has a good analysis of the sequester redo.

4. Fama and Shiller, on each other.

5. Average is Over in farming. And the FDA restricts antibiotic use in livestock.

6. Timothy Taylor on Alvin Hansen.

7. Adam Ozimek at Forbes reviews Average is Over.

Sentences to ponder…

Notably, easy-to-reach women are happier than easy-to-reach men, but hard-to-reach men are happier than hard-to-reach women, and conclusions of a survey could reverse with more attempted calls.

That is Ori Heffetz and Matthew Rabin, in the new AER. An ungated version is here. Understandably, the authors are worried about potential subject selection biases in studies of self-reported happiness.

Thinking for the Future

That is the new and very good David Brooks column about Average is Over. Here is one excerpt:

So our challenge for the day is to think of exactly which mental abilities complement mechanized intelligence. Off the top of my head, I can think of a few mental types that will probably thrive in the years ahead.

…Synthesizers. The computerized world presents us with a surplus of information. The synthesizer has the capacity to surf through vast amounts of online data and crystallize a generalized pattern or story.

Humanizers. People evolved to relate to people. Humanizers take the interplay between man and machine and make it feel more natural. Steve Jobs did this by making each Apple product feel like nontechnological artifact. Someday a genius is going to take customer service phone trees and make them more human. Someday a retail genius is going to figure out where customers probably want automated checkout (the drugstore) and where they want the longer human interaction (the grocery store).

…Motivators. Millions of people begin online courses, but very few actually finish them. I suspect that’s because most students are not motivated to impress a computer the way they may be motivated to impress a human professor. Managers who can motivate supreme effort in a machine-dominated environment are going to be valuable.

Do read the whole thing.

The happiness of economists

There is a new paper by Lars P. Feld, Sarah Necker, and Bruno S. Frey, and here is the abstract:

This study investigates the determinants of economists’ life satisfaction. The analysis is based on a survey of professional, mostly academic economists from European countries and beyond. We find that certain features of economists’ professional situation influence their well-being. Happiness is increased by having more research time while the lack of a tenured position decreases satisfaction in particular if the contract expires in the near future or cannot be extended. Surprisingly, publication success has no effect on satisfaction. While the perceived level of external pressure also has no impact, the perceived change of pressure in recent years has. Economists may have accepted a high level of pressure when entering academia but do not seem to be willing to cope with the increase observed in recent years.

You will note that “Economists tend to report a high level of life satisfaction.” Furthermore this does not vary by gender. Here are the nationality effects:

Compared to German economists, Italian, French and researchers from Eastern European countries have a statistically significantly lower probability to report being “highly satisfied” (significant at least at the 5%-level). A similar effect is observed for economists from Spain, Portugal, and Austria; the effects are, however, at most significant at the 10%-level. Researchers from Switzerland, North America and Scandinavian countries tend to be more happy.

For the pointer I thank Viktor Brech.

Best fiction books of 2013

Every year I offer my picks for best books of that year, today we are doing fiction. I nominate:

1. Karl Knausgaard, My Struggle: Book Two: Man in Love.

2. Claire Messud, The Woman Upstairs. Great fun.

3. Amy Sackville, Orkney. Not every honeymoon works out the way you planned.

4. Mohsin Hamid, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.

5. Kathryn Davis, Duplex: A Novel. Non-linear, not for all.

Since I think the Knausgaard is one of the greatest novels ever written, I suppose it also has to be my fiction book of the year. (Except, um…it’s not fiction.) But otherwise I found many books disappointing, perhaps because my own expectations were out of synch with contemporary writing.

Elizabeth Gilbert and Donna Tartt produced decent plane reads, but I wouldn’t call them favorites. The new Thomas Pynchon I could not stand more than a short sample of. I sampled many other novels but didn’t like or finish them. I read or reread a lot of Somerset Maugham, which was uniformly rewarding. The Painted Veil may not be the best one, but it is a good place to get hooked. I reread quite a bit of Edith Wharton and it rose further in my eyes. Ethan Frome and The Age of Innocence are my favorites, more intensely focused than the longer fiction. I loved discovering the Philip Pullman trilogy and vowed to give George Martin another try this coming year.

Assorted links

1. Dept. of Uh-Oh, ultimately.

2. New study on ocean acidification.

3. James Scott reviews Jared Diamond on traditional societies. And man outruns cheetah.

4. The negative income tax experiments of New Jersey and Seattle. And related attempts from Canada.

5. Criticisms of Silicon Valley venture capital funding.

A life well-lived

This is from the obituary of economist Alexander L. Morton:

At 42, Mr. Morton was well on pace in the ascension of his chosen career ladder. He had a doctorate in economics from Harvard, had taught at the Harvard Business School and was finishing a four-year assignment as director the office of policy and analysis at the Interstate Commerce Commission.

He then quit.

He had made enough money in real estate deals and investments to guarantee an independent income for himself. For his remaining 28 years, he was almost constantly on the move, visiting dozens of countries and often going off the expected paths from Western travelers.

And this:

He rarely spoke about himself and never discussed in detail his reasons for retiring in mid-career as an economist to pursue a life of travel. But his sister said he was ready for a change, had the savings to and had done as much as he wished to in the field of transportation deregulation.

To continue along the same path, would have been a case of “been there, done that,” she said.

Here is Alex’s earlier post on traveling more. Maybe Alexander L. Morton had some really good lunch partners.

Borges on English literature

The pleasures of Professor Borges. His message to students: The study of literature is about appreciation, not context or theory. “Reading should be a form of happiness”… more»

The Fanfare classical music meta-list for best recordings of the year

Fanfare is the leading periodical for classical music reviews, and every year it asks numerous critics — this time 45 of them — for their top five classical music picks of the year. In turn, each year I present a meta-list, which simply is a list of all the works selected by more than one critic. This year we have:

1. Meanwhile, by Eighth Blackbird., assorted contemporary pieces.

2. Haydn, The Creation, conducted by Martin Pearlman.

3. Arvo Pärt, Adam’s Lament.

4. Bellini’s Norma, with Cecilia Bartoli.

I just ordered 1-3 of those, for the Bellini I am still stuck on Maria Callas. My personal picks of the year, in classical music, would be:

1. Shostakovich string quartets, Pacifica Quartet, several volumes, including some other Soviet compositions as well. I find these more powerful than Emerson, Manhattan, Brodsky, or the other classic sets of Shostakovich.

2. Arvo Pärt, Creator Spiritus.

3. Klára Würtz and Kristóf Baráti, Beethoven sonatas for violin and piano.

4. The Art of David Tudor, seven disc box set, caveat emptor on this one.

Japan markets in everything

While you’re probably aware of Tokyo’s cat cafes that let visitors cuddle up with a kitty while sipping some coffee, you’re unlikely to have heard of owl cafes, the latest craze to take hold in the Japanese capitol. Known locally as a “fukurou cafe,” some of the establishments offer owl-themed food and drink, and some even let you pet the owls in residence.

Some of the stores that garnered online attention late last year include Fukurou no Mise (“Owl Shop”) and Tori no Iru Cafe (“The Cafe with Birds”). Since then, more of the owl cafes have opened around Tokyo and Osaka including Fukurou Sabou (“Owl Teahouse”), Owl Family, and Crew.

There are photos at the link, hat tip goes to Ian Leslie.

The declining return to education spending in South Korea

This spending, however, no longer yields rich returns. Going to university racks up tuition fees and keeps young people out of the job market for four years. After graduation it takes an average of 11 months to find a first job. Once found, the jobs remain better paid and more secure than the positions available to high-school graduates, but the gap is narrowing. The McKinsey Global Institute reckons that the lifetime value of a college graduate’s improved earnings no longer justifies the expense required to obtain the degree. The typical Korean would be better off attending a public secondary school and diving straight into work.

If the private costs are no longer worthwhile, the social costs are even greater. Much of South Korea’s discretionary spending on private tuition is socially wasteful. The better marks it buys do not make the student more useful to the economy. If one student spends more to improve his ranking, he may land a better job, but only at the expense of someone else.

Even in terms of a signaling model, it seems this spending has gone too far. And indeed this is showing up in the numbers:

The proportion of high-school graduates going on to higher education rose from 40% in the early 1990s to almost 84% in 2008. But since then, remarkably, the rate has declined (see chart 2). South Korea’s national obsession with ever higher levels of education appears to have reached a ceiling.

The article, from The Economist, is interesting throughout.

*The Goldfinch*, by Donna Tartt

Many people are calling this book the novel of the year (reviews here). It’s pretty good and it held my attention — I read 780 pp. and was never tempted to quit. It is an ideal plane read, but I don’t expect it will stick with me. I put it in the “worth reading if you’ve read most of the other books you want to read” category, but that is not a space you should wish to inhabit.

Contemporary Christian Philosophy: A Primer

My two posts arguing that Christian belief is reasonable brought out precisely the sorts of incredulity I expected. In return, I thought I’d introduce you to some of the work in contemporary Christian philosophy that I have found convincing. I’m inviting you to reconsider the rational status of Christian belief. So let this post be a primer in contemporary Christian philosophy: an open door to start conversations about the possibility of rational Christian belief and religious belief generally. I worked hard compiling and linking to resources because I’m trying to honor your requests for more information and to respect your intelligence as rational individuals.

Over the last forty years, the field of Christian philosophy has exploded in richness and depth. Much of the work began following the founding of The Society of Christian Philosophers, in 1978. Today the SCP is the largest subgroup in the American Philosophical Association, with over 1100 members of Christians from a vast range of denominations and degrees of theological conservatism and liberalism. (I’m a member!)

These philosophers have produced hundreds of books working out answers to various questions raised by the Christian religion.

As I could tell from my last post, many of you feel that thoughtful arguments for Christian claims do not exist. I once felt similarly, and in this post I thought I’d explain why I changed my mind.

I divide my categorization of books into a wide range of categories on questions that directly or indirectly bear on the truths of the Christian religion.

I. Indirect Arguments for Core Christian Beliefs

I will begin with questions that bear indirectly, specifically books that convinced me to abandon the Christian worldview’s main intellectual competitor: naturalism. For me, these came in three categories, regarding the fail of naturalistic accounts of (i) mind (especially consciousness and intentionality), (ii) choice and free will and (iii) the nature of morality. Naturalism, which I understand as the view that all that exists is describable by science (empirical facts) or that are required to form scientific models (mathematics).

Ia. Mind

I don’t think that naturalism can account for or explain the nature of consciousness, specifically the phenomenon of qualia, or the unique features of conscious experience. I was most convinced by David Chalmers’ famous book, The Conscious Mind. John Searle’s works, especially The Rediscovery of the Mind, convinced me that we cannot give a naturalistic account of intentionality, the fact that mental states have propositional content (they’re about things). He also convinced me that the mind is not a computer, even if it has computational mechanisms.

But Chalmers convinced me Searle’s attempt to avoid dualism is a failure and Searle convinced me that Chalmers’ (then) epiphenomenalism was implausible. This led me to property dualism about mental properties, but I agreed with Searle that property dualism is unstable and collapses into substance dualism. And Richard Swinburne’s book, The Evolution of the Soul, and John Foster’s book, The Immaterial Self, convinced me that substance dualism was a perfectly respectable philosophical position. So I think there are souls, and I think I have darn good philosophical reason to think so.

Ib. Free Will

For years, I didn’t take issues of free will seriously, but Peter Van Inwagen’s famous book, An Essay on Free Will, convinced me that free will and moral responsibility were inextricably tied, and since I was unable to give up moral responsibility, I became a libertarian about free will. Namely, I occasionally have the power to do otherwise than I did. The initial conditions of the universe and the laws of nature do not preclude me from doing otherwise. I did other reading in the literature, but it was Van Inwagen that anchored me. I now take compatibilist challenges pretty seriously, especially those advanced by Michael McKenna, but I still think libertarians have the upper hand.

Ic. Morality

Many naturalists reject moral claims altogether. I always found that position not merely wrong but repulsive. There are things that are wrong to do and any worldview that cannot explain that some things are genuinely wrong is a bad worldview. Any conscientious person is sufficiently committed to condemning things like the Holocaust to abandon naturalism if she became convinced that naturalism could not explain the fact that the Holocaust was a terrible moral crime. And I came to believe that facts about goodness could not be grounded in desire or preference. Mark Murphy’s book, Natural Law and Practical Rationality, played a role here, but so did Nozick’s experience machine case in Anarchy, State and Utopia. There is an objective account of human interests and the human good that cannot be reduced to any natural facts. That is, there are normative facts, facts about what is good for us and what we should seek, that cannot be explained by scientific inquiry and that do not supervene on natural facts. Aristotle and Aquinas’s accounts of human nature and substantial forms helped me to explain why some things are good and bad for humans, and Aristotelian-Thomism is a serious, rich competitor to contemporary naturalisms. I also think Divine Command Theory has been rehabilitated as a serious moral theory by Robert Adams in Finite and Infinite Goods.

I became similarly convinced about the idea of right because, while I am a deontologist, I think that rightness is understood partly as a set of moral requirements to advance the good, and if the good cannot be naturalized, then I think it follows the right cannot be either. However, I am considerably more sympathetic to naturalistic accounts of rightness than goodness.

Id. What of Christianity?

Now, if you become a libertarian about free will, a substance dualist about mind and an objectivist about the human good, you most certainly do not have to be a Christian. But Christianity is committed to these views (in my opinion). And by showing that those commitments are correct, some of the biggest objections have been cleared away.

II. Direct Arguments for Core Christian Beliefs

Now I shall review works on the core Christian claims, specifically (a) arguments for God’s existence, (b) further arguments for the divine attributes, (c) arguments for rational belief in miracles, (d) arguments for rational belief in religious experience, (e) arguments for the reliability of religious texts like the Bible (not their infallibility), (f) arguments making sense of the doctrine of the atonement, (g) arguments that revealed doctrines like the Trinity, while sometimes mysterious, remain undefeated and (h) arguments that if theism is true, Jesus probably rose from the dead. There’s a lot more to say, but this, if I do say so myself, is a great start.

Note that there are Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries with bibliographies on most of these topics. You can also review another list of arguments here.

IIa. Arguments for God’s Existence

A great introduction is Richard Swinburne’s The Existence of God.

(i) Cosmological Arguments

Cosmological arguments attempt to demonstrate that God is the creator of the contingently existing cosmos. “Prime Mover” arguments are versions of cosmological arguments, but they’re not the best. The best cosmological arguments, in my mind, are arguments from the mere fact of contingent facts. If you adopt even a modest version of the principle of sufficient reason, the existence of a necessary being, or at least onenecessary concreta, basically follows as a matter of modal logic. Just check out the simple version in the SEP entry to evaluate this claim for yourself. The cosmological argument is plainly logically valid, and its core substantive premises are plausible and attractive in many ways. That’s as much from a philosophical argument as you might ask. I have a couple of favorite discussions of cosmological arguments. I think Ed Feser’s discussion of Aquinas’s five ways in his Aquinas is especially accessible, though I quite like the considerably harder analysis of Aquinas’s arguments in Norman Kretzman’s commentary on Aquinas’s Summa Contra Gentiles in The Metaphysics of Theism: Aquinas’s Natural Theology in Summa Contra Gentiles I. I think Leibniz’s argument is still pretty damn good, but I like the two recent, anthologized versions advanced by Richard Taylor here. I quite like (though haven’t finished) Alex Pruss’s book on the principle of sufficient reason, The Principle of Sufficient Reason: A Reassessment and my friend Josh Rasmussen’s cutting edge work in the area. Here’s his piece, “From States of Affairs to a Necessary Being” in Phil Studies and his piece, “A New Argument for a Necessary Being” in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy.

Cosmological arguments attempt to demonstrate that God is the creator of the contingently existing cosmos. “Prime Mover” arguments are versions of cosmological arguments, but they’re not the best. The best cosmological arguments, in my mind, are arguments from the mere fact of contingent facts. If you adopt even a modest version of the principle of sufficient reason, the existence of a necessary being, or at least onenecessary concreta, basically follows as a matter of modal logic. Just check out the simple version in the SEP entry to evaluate this claim for yourself. The cosmological argument is plainly logically valid, and its core substantive premises are plausible and attractive in many ways. That’s as much from a philosophical argument as you might ask. I have a couple of favorite discussions of cosmological arguments. I think Ed Feser’s discussion of Aquinas’s five ways in his Aquinas is especially accessible, though I quite like the considerably harder analysis of Aquinas’s arguments in Norman Kretzman’s commentary on Aquinas’s Summa Contra Gentiles in The Metaphysics of Theism: Aquinas’s Natural Theology in Summa Contra Gentiles I. I think Leibniz’s argument is still pretty damn good, but I like the two recent, anthologized versions advanced by Richard Taylor here. I quite like (though haven’t finished) Alex Pruss’s book on the principle of sufficient reason, The Principle of Sufficient Reason: A Reassessment and my friend Josh Rasmussen’s cutting edge work in the area. Here’s his piece, “From States of Affairs to a Necessary Being” in Phil Studies and his piece, “A New Argument for a Necessary Being” in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy.

You can check out Alex Pruss’s page on cosmological and ontological arguments here.

Here’s a short paper of Pruss’s defending his very restricted version of the PSR.

Oh, and if you’re interested, Josh has set up a neat page trying to test intuitions to see if they entail the existence of a necessary being here: www.necessarybeing.net

Here’s the SEP entry on cosmological arguments.

Also see Doherty’s awesome bibliography here.

(ii) Ontological Arguments

Cosmological arguments, at least in their first stage, only get you at least one necessary being. I think it will follow on analysis of the very idea of a necessary being that certain divine attributes follow. However, that takes more work. The promise of ontological arguments is to get you to something very much like God pretty darn quickly. The problem with ontological arguments is that they initially seem to reek of bullshit. The awesome thing about ontological arguments is that it’s actually really hard to explain what is wrong with them. You might consider reviewing David Lewis’s amazing attempt to identify the real problem here in Chapter 2, “Anselm and Actuality” in the first volume of his Philosophical Papers. I think Anselm’s argument works iff you accept his neo-Platonic metaphysics, which I think is weird but not insane. There’s a much more worked out version in his Monologion, which predates the much more famous Proslogion. I think the SEP entry shows why Kant didn’t definitively refute ontological arguments, as I think most philosophers personally believe. The fact is plenty of ontological arguments just don’t depend on treating existence as a predicate. I think Plantinga develops a pretty novel modal version of the argument in Chapter 10 his wonderful book, The Nature of Necessity. The problem with the modal ontological argument is that while it follows as a matter of (somewhat contentious) modal logic that if God is metaphysically possible, then He necessarily exists, it also follows that if God is metaphysically possibly-not, then He is impossible. But if you can be rationally justified in believing that there exists at least one possible world in which a Maximally Great being exists, then simple modal axioms entail that God exists in this possible world, the actual world. And Plantinga says in his famous article that he’s merely trying to show that there is an ontological argument that can justify theistic belief.

Pruss, I’m told, is all really good on ontological arguments. Go here and here for his defense of Gödel’s version.

(For libertarians: Pruss is awesome. He’s like a Catholic Robin Hanson: inventive mind, ridiculous math and formal chops, willing to consider completely bizarre and fun scenarios as a guide to truth. And he blogs.)

Here’s the SEP entry on ontological arguments.

Also see Doherty’s awesome bibliography here.

(iii) Teleological Arguments

Teleological arguments generally try to establish that God exists based on the presence of intelligently designed features of the universe. You are probably most familiar with the biological versions of the argument most famously advanced by William Paley. Paley was actually really freaking smart and I encourage you to read his famous book, Natural Theology. He anticipates a Darwin-like challenge that design could arise as a series of very minor alterations, but argues that the design inference is nonetheless valid. I think design inferences are licensed so long as the presence of order in the world is more probable on the conjunction of theism and evolution than on the conjunction of atheism and evolution. And I think it’s perfectly plausible to think as much.

But the better teleological arguments in my mind are the cosmological fine-tuning arguments, especially the cool one advanced by Rob Collins, which you can find here. Here also has a great website on the fine-tuning argument here. Collins has advanced the view that on the assumption that the cosmological constants of physics could have had different values, a quite strong case for the existence of a powerful, good, intelligent being can be made. I agree with him.

Here’s the SEP on teleological arguments.

Also see Doherty’s awesome bibliography here.

(iv) Properly Basic Belief

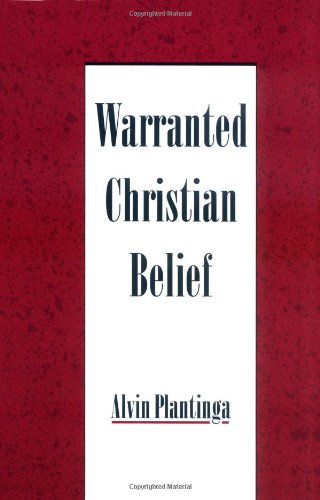

Now, I don’t think you actually need any of the classical theistic arguments to demonstrate that theism can be epistemically justified. Reformed epistemologists have been arguing as much for decades. The idea, roughly, is that belief in God can be properly basic, or held without any justifying reasons at all. Now, Reformed epistemologists take on a kind of theistic reliabilism about whether one is entitled to or warranted in believing a great many things. This means that so long as one’s cognitive faculties reliably track the truth, rational belief does not require any internal psychological access to one’s justifiers for one’s beliefs. I don’t find reliabilism all that plausible outside of perceptual beliefs, but I think it’s a perfectly respectable way to go. I think what Plantinga showed in his wonderful God and Other Minds is something simpler, namely that belief in God has the same epistemic status as belief in other minds. There’s no way to prove to all rational persons that God exists, nor is it possible to prove that other minds exist. For all I know, you’re a bunch of zombie meat husks with no consciousness. But my belief is nonetheless justified. Of course, Plantinga has the great, magesterial work on the matter, Warranted Christian Belief, where he works out his most detailed statement of Reformed epistemic approaches to Christian belief, but there are perfectly respectable internalist ways to go as well.

Now, I don’t think you actually need any of the classical theistic arguments to demonstrate that theism can be epistemically justified. Reformed epistemologists have been arguing as much for decades. The idea, roughly, is that belief in God can be properly basic, or held without any justifying reasons at all. Now, Reformed epistemologists take on a kind of theistic reliabilism about whether one is entitled to or warranted in believing a great many things. This means that so long as one’s cognitive faculties reliably track the truth, rational belief does not require any internal psychological access to one’s justifiers for one’s beliefs. I don’t find reliabilism all that plausible outside of perceptual beliefs, but I think it’s a perfectly respectable way to go. I think what Plantinga showed in his wonderful God and Other Minds is something simpler, namely that belief in God has the same epistemic status as belief in other minds. There’s no way to prove to all rational persons that God exists, nor is it possible to prove that other minds exist. For all I know, you’re a bunch of zombie meat husks with no consciousness. But my belief is nonetheless justified. Of course, Plantinga has the great, magesterial work on the matter, Warranted Christian Belief, where he works out his most detailed statement of Reformed epistemic approaches to Christian belief, but there are perfectly respectable internalist ways to go as well.

The general point here is that I think atheists implicitly hold the rationality of theistic belief to absurdly high standards, far beyond the rationality of belief in all sorts of weird views. I don’t think that asymmetric treatment can be justified, not even a bit.

You’ll want to see Platinga and Wolterstorff’s book on Faith and Rationality.

Here’s a brief SEP entry on Reformed Epistemology.

IIb. Arguments for the Divine Attributes

Now many of you are no doubt thinking that even if the theistic arguments are sufficient to justify belief, they don’t prove that the God of Christianity exists. This is true, though the ontological argument comes rather close, though admittedly it is the most dicey. However, combinations of these arguments can get us quite a bit. For instance, a cosmological argument can give us omnipotence (since God ultimately explains all contingent facts) and that God is personal (since a necessary being cannot be material, since matter can cease to exist). Further, since God knows how to create the universe, he must know quite a bit. The teleological argument can strengthen our convictions in God’s power and intelligence. We can also see God’s benevolence in creation in various ways, though obviously the problem of evil is a very powerful challenge here. However, there are lots of arguments that follow the establishment of the more modest premises in the traditional theistic arguments, what we often call “stage 2” of theistic arguments. There are so many divine attributes, so I can’t say too much here that’s at all definitive. But I will point you to the discussion in Kretzmann (here and here) and Stump (here, especially Part I), which are the ones I’ve paid most attention to besides reading Aquinas himself.

If you’re interested, here are some other recommendations. Check out my friend Josh Rasmussen’s piece, “From a Necessary Being to God,” here (ungated).

Also see Doherty’s awesome bibliography on the divine attributes here.

(i) Divine Eternality, Simplicity

But let me sketch some of the arguments in their generic form. If there exists a necessary being, it obviously exists at all points in time, so the being is eternal. And arguably a necessary being cannot have parts, since if it had parts, those parts could conceivably come apart. If so, then God must be perfectly simple.

(ii) Divine Omnipotence and Intelligence

If God is the source of all contingency, then it seems He can do a great many metaphysically possible things, which doesn’t show perfect omnipotence, but is pretty damn close. And of course omnipotence does not involve doing the logically impossible, since there’s nothing that there is to be logically impossible.

What’s more, God is an intelligence because he is a causally endowed immaterial being. A necessary being cannot be a material being because matter can cease to exist. And if he isn’t matter, he must be either mental or abstracta. And since abstracta lack efficient causal power, he must be mental. So God is an intelligence, a pure spirit.

And since God is a causally endowed intelligence, then all his causal power is based on his reasoning and will. If so, it’s hard to see how God couldn’t be spectacularly intelligent. If that doesn’t do it for you, then source the cosmological fine-tuning argument, which shows that God’s handiwork is pretty darn spectacular. He must be pretty smart.

(iii) Divine Goodness

A necessary being must be a good being, on Aquinas’s view, because a being that is the source of all contingency must possess all the “perfections,” which is a kind of Platonic argument I don’t entirely understand. My reason for thinking that God is all good is that a simple being cannot possibly be evil because evil requires a rational misapprehension of the good and at least some degree of self-deception. A simple mind has no parts to it, and so cannot hide anything form itself. It is incapable of the cognitively necessary conditions for doing evil. So that’s why God is good. He’s good for other reasons, but there’s one I find interesting.

The divine attributes are relatively unexplored territory in contemporary Christian philosophy. People work on it, but I think there are a lot of cool questions that haven’t been given as adequate a treatment. But in all likelihood, my turn to moral and political philosophy, along with political economy, has led me to overlook a lot of good literature. So here are some recommendations:

(a) Omnipotence: Flint, T., and A. Freddoso. “Maximal Power.” In The Existence and Nature of God.

(b) Omniscience: Kvanvig, Jonathan. The Possibility of an All-Knowing God.

(c) Eternity: Helm, Paul. Eternal God.

(d) Simplicity: Brower, Jeffrey. “Making Sense of Divine Simplicity.”

IIc. On Miracles

A lot of people think that Hume’s criticism of belief in miracles is decisive. I don’t. There is a lot of writing on this, but I like C.S. Lewis’s brief discussion in his book Miracles and Swinburne’s discussions in various books, all the way from his short work, The Concept of a Miracle in 1970 to his discussion in The Resurrection of God Incarnate. The basic idea of Lewis’s critique and a number of others is that the probability of miracles is heavily dependent on the probability of theism, so the probability of miracles is relative (surprise) to your background beliefs. It’s rather hard, accordingly, to show that belief in miracles (like the resurrection of Jesus Christ) is irrational in general.

See this piece: McGrew, Timothy & Lydia, 2009, “The Argument from Miracles,” in William Lane Craig and J. P. Moreland, eds., The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology.

Also see this recent (ungated) piece on the argument from miracles by Daniel Bonevac and this by John Depoe attempts to give a Bayesian approach to confirming miracles.

Here’s the SEP on miracles. It’s written by Tim McGrew, who I’m told is excellent on the topic, but I haven’t read him.

IId. On Religious Experience

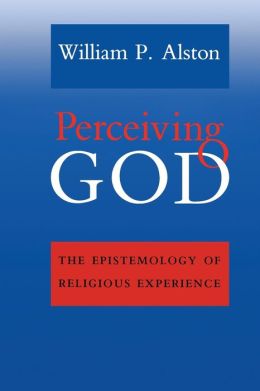

The classic work on the veracity of religious experience is William Alston’s Perceiving God, which had a major impact on me. Alston thinks that if God exists, we can be warranted in believing we have experienced Him when He contacts us. The work is based on a form of Reformed epistemology, but I think its arguments can be broadened beyond that perhaps more controversial basis. Alston has an interesting argument that we aren’t capable of validating experiential practices outside of the practice itself for just about any sensory practice, so the same might be true for our faculty for perceiving God.

The classic work on the veracity of religious experience is William Alston’s Perceiving God, which had a major impact on me. Alston thinks that if God exists, we can be warranted in believing we have experienced Him when He contacts us. The work is based on a form of Reformed epistemology, but I think its arguments can be broadened beyond that perhaps more controversial basis. Alston has an interesting argument that we aren’t capable of validating experiential practices outside of the practice itself for just about any sensory practice, so the same might be true for our faculty for perceiving God.

See the SEP on religious experience.

IIe. On Religious Texts

Two great books arguing in favor of the rationality of belief in divine revelation, say through religious texts are Swinburne’s classic Revelation: From Metaphor to Analogy and Sam Fleischacker’s recent book, Divine Teaching and the Way of the World: A Defense of Revealed Religion, which I just reviewed for Mind.

IIf. On the Atonement

Again I love Swinburne here. I like his Responsibility and Atonement, but I also like Eleanore Stump’s discussion of atonement in her book, Aquinas in Chapter 15. And, well, I like Anselm! See Cur Deus Homo, which outlines the substituionary view. It includes some wild assumptions that aren’t necessary to the defense, however, as Swinburne and Stump show, I think.

IIg. On the Trinity

The Trinity is the doctrine I’ve read about least. I think the idea is mysterious, but I know enough people who read and write about it that I think I have good reason to think I can avoid proposed defeaters for my views. A lot of you think, “Well, it’s dumb because three can’t be one. QED.” But obviously the doctrine is the God is three in one sense and one in another. So unless you know those distinct senses, I’m not sure you have a defeater in hand. You can find recent literature below (like Swinburne’s non-orthodox view), but I still think Augustine’s On the Trinity is pretty good, as it Aquinas’s discussion in the Summa (discussed here). The real question here is (a) whether the doctrine is coherent and (b) whether it is Scripturally grounded. I have only read about (a). My ground for (b) is my belief that God established a Church to think through these issues, so I rely on the ecumenical councils for my information. I consider them experts and can defend that view if you like.

SEP entry here. (Yes, they even have an entry on The Trinity; the SEP is awesome).

IIh. On the Resurrection

This one is pretty critical because it’s one of the core claims that many contemporary Christian philosophers used to draw people into the faith. I still love Swinburne’s The Resurrection of God Incarnate and find Lewis’s discussion in Mere Christianity a good introduction, though not a good place to end one’s inquiry. But there are so many books on the matter, ranging from The Case for Christ all the way up the ladder of philosophical sophistication to Swinburne, with everything in between. And of course you cannot discuss this topic without referring to all of William Lane Craig’s books on the subject. There are several debate books, but one stand alone is The Son Rises: The Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus. Please note that these aren’t proofs that atheists should believe that Jesus rose. Instead, I think they’re sufficient to justify theists in believing that Jesus rose from the dead.

This one is pretty critical because it’s one of the core claims that many contemporary Christian philosophers used to draw people into the faith. I still love Swinburne’s The Resurrection of God Incarnate and find Lewis’s discussion in Mere Christianity a good introduction, though not a good place to end one’s inquiry. But there are so many books on the matter, ranging from The Case for Christ all the way up the ladder of philosophical sophistication to Swinburne, with everything in between. And of course you cannot discuss this topic without referring to all of William Lane Craig’s books on the subject. There are several debate books, but one stand alone is The Son Rises: The Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus. Please note that these aren’t proofs that atheists should believe that Jesus rose. Instead, I think they’re sufficient to justify theists in believing that Jesus rose from the dead.

III. Replies to Core Objections to Christian Beliefs

The books cited have already answered many objections to Christianity, such as that God does not exist, that the Gospels are unreliable, that the atonement and the Trinity make no sense. But three big problems remain (in increasing order of importance: (a) the problem of hell, (b) the conflict between science and religion, (c) the problem of divine wickedness and (d) the problem of evil. I won’t cover the problems of divine hiddenness and petitionary prayer.

IIIa. The Problem of Hell

Lots of Christian philosophers are universalists these days. Maybe most are, so there’s no problem of hell because everyone gets out eventually. For a core Christian challenge to the doctrine of hell, see Marilyn McCord Adams’s article, “The problem of hell: a problem of evil for Christians” in Reasoned Faith: Essays in Philosophical Theology in Honor of Norman Kretzmann (. Follow the citation path from there. I think the doctrine makes sense so long as everyone there prefers God’s absence to God’s presence, such that Lewis was right in saying the gates of hell are locked from the inside. I quite like his discussion in The Great Divorce.

Also see Jon Kvanvig’s book (which I’m told is great): The Problem of Hell.

There’s even an SEP entry on heaven and hell!

IIIb. Science and Religion

There is so much on the science-religion conflict I can’t begin to review it adequately. You can read Alvin Plantinga’s SEP entry on the matter. I love, love, love his new book on the matter, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion and Naturalism, which just came out. I think Plantinga decisively shows that there is no conflict between physics and evolutionary biology on the one hand and the core Christian creeds on the other. Basically, on theism, science describes the regularities that obtain when God does not engage in special action, but God can engage in special action from time to time, rarely, so as not to render scientific claims anything but extremely probable. But God doesn’t need to upset the order of nature very much for core Christian claims to be true. What’s more, naturalism and evolution are in tension with one another.

There is so much on the science-religion conflict I can’t begin to review it adequately. You can read Alvin Plantinga’s SEP entry on the matter. I love, love, love his new book on the matter, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion and Naturalism, which just came out. I think Plantinga decisively shows that there is no conflict between physics and evolutionary biology on the one hand and the core Christian creeds on the other. Basically, on theism, science describes the regularities that obtain when God does not engage in special action, but God can engage in special action from time to time, rarely, so as not to render scientific claims anything but extremely probable. But God doesn’t need to upset the order of nature very much for core Christian claims to be true. What’s more, naturalism and evolution are in tension with one another.

Again, here’s the SEP entry.

IIIc. Divine Wickedness

Again, there’s a lot here, but for a series of struggles to make sense of divine action in the Old Testament see this reader: Divine Evil: The Moral Character of the God of Abraham for some defenses and attacks drawn from a recent conference on the matter. I’m a Stump guy myself, but Wolterstorff and Swinburne’s contributions are interesting, alone with Mark Murphy’s. You can check out an NDPR review here.

IIId. The Problem of Evil

Finallywe reach the granddaddy of all problems for Christianity and theistic belief general, the problem of evil. Importantly, the problem of evil literature has exploded since Mackie’s challenge in The Miracle of Theism. Plantinga is widely believed to have refuted Mackie’s version of the problem, which purports to show that there is no possible world in which God and evil coexist. Plantinga shows that there is at least one possible world in which humans have libertarian freedom and God cannot actualize the world without permitting them to commit evil due to the fact that some of these people possess transworld depravity. He argues as much in The Nature of Necessity, but the solution is famous enough in the field to have a Wikipedia entry. Since then people have focused on analyzing the evidential problem of evil, which holds that evil is counterevidence to God’s existence. For anthologies of problems and solutions for both the logical and evidential problems see The Problem of Evil (Oxford Readings in Philosophy), edited by Marilyn McCord Adams and Robert Merrihew Adams. Also see Daniel Howard-Snyder’s reader, The Evidential Argument from Evil, which has Stephen Wykstra’s famous skeptical reply. These days skeptical theism is a big philosophical project, with Michael Rea having over a million dollars to study the view. I buy into a strong form of skeptical theism where I believe I am justified in (a) affirming theism, (b) affirming that God has morally sufficient reason to permit evil and (c) affirming that neither I nor any other human is in an epistemic position to know what those particular reasons are.

I like Van Inwagen’s discussion in his recent book, The Problem of Evil.

I’m told (but haven’t confirmed) that William Hasker’s book on evil is excellent. See his book, The Triumph of God over Evil: Theodicy for a World of Suffering.

But let me say this:

Few books in philosophy have changed my life. But reading early versions of Eleanore Stump’s book Wandering in Darkness made the philosophical and personal questions I had about evil concrete in a powerful way that continues to move me. The book is nothing short of extraordinary, a true tour-de-force. It is beautiful.

Few books in philosophy have changed my life. But reading early versions of Eleanore Stump’s book Wandering in Darkness made the philosophical and personal questions I had about evil concrete in a powerful way that continues to move me. The book is nothing short of extraordinary, a true tour-de-force. It is beautiful.

For a brief overview of recent work in the area, see Trent Dougherty’s piece in Analysis.

Here’s the SEP on the problem of evil.

Also see Doherty’s awesome bibliography on the problem of evil here.

IV. Conclusion

So I’ve given you a brief overview of recent philosophical work I have found extremely useful in (a) rebutting Christianity’s main philosophical competitor, naturalism, (b) establishing epistemic justification for core Christian claims and (c) successfully rebutting powerful objections.

Now, suppose someone like me reads many of these books and decides that Christianity is true. Is she stupid or ill-informed? Did she fail to discharge her epistemic duties? Is she simply guilty of motivated cognition and wish fulfillment? Or has she acquitted herself with a highly respectable degree of reasoning?

I understand that many of you want to resist what I’m saying. But given this background, are you still as sure as you were that a rational person under modern conditions can’t be a Christian? All I’m asking is for you to entertain the idea that rational Christian belief is possible.

Assorted links

1. A polemic in favor of Texas and against the stability of tech jobs.

2. James Bessen at The Washington Post reviews *Average is Over*. I agree with him that numerous decades later, things will be fine. Kevin Drum responds along different lines.

3. Reihan on ACA and Medicaid reform.

4. A good criticism of Chetty on economics as a science.

5. One overview of the new jobs report. And how much has sequestration hurt the DC-area job market?

6. David Romer on why do firms prefer more able workers?