Shared posts

Model: Universal mask-wearing would do more to reduce infection than indefinite lockdowns would

Alexander Wendt on why we should take UFOs seriously

He has more than just the usual hand-wringing, here is one excerpt:

Sean Illing

…What’s the Occam’s razor explanation for these UFO sightings?

Alexander Wendt

To me, the Occam’s razor explanation is ETs.

Here is another:

Sean Illing

If some of these UFOs are the products of alien life, why haven’t they made their presence more explicit? If they wanted to remain undetected, they could, and yet they continually expose themselves in these semi-clandestine ways. Why?

Alexander Wendt

That’s a very good question. Because you’re right, I think if they wanted to be completely secretive, they could. If they wanted to come out in the open, they could do that, too. My guess is that they have had a lot of experience with this in the past with civilizations at our stage. And they probably know that if they land on the White House lawn, there’ll be chaos and social breakdown. People will start shooting at them.

So I think what they’re doing is trying to get us used to the idea that they’re here with the hopes that we’ll figure it out ourselves, that we’ll go beyond the taboo and do the science. And then maybe we can absorb the knowledge that we’re not alone and our society won’t implode when we finally do have contact. That’s my theory, but who knows, right?

Here is the full piece, interesting and intelligent throughout.

The post Alexander Wendt on why we should take UFOs seriously appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Coronavirus sports markets in everything, multiple simulations edition

For $20, fans of German soccer club Borussia can have a cut-out of themselves placed in the stands at BORUSSIA-PARK. According to the club, over 12,000 cut-outs have been ordered and 4,500 have already been put in place.

Here is the tweet and photo.

And some sports bettors are betting on simulated sporting events. (Again, I’ve never understood gambling — why not save up your risk-taking for positive-sum activities? Is negative-sum gambling a kind of personality management game to remind yourself loss is real and to keep down your risk-taking in other areas?)

Via Samir Varma and Cory Waters.

The post Coronavirus sports markets in everything, multiple simulations edition appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

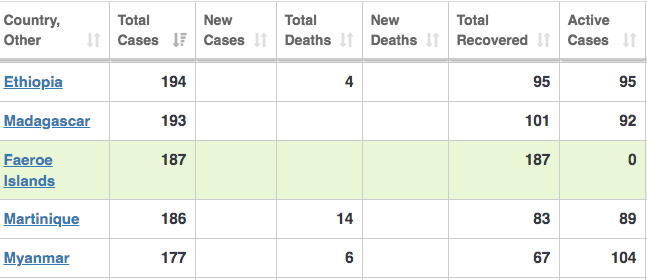

Congratulations to Faeroe Islands

Faeroe Islands is the first place with over 100 cases to completely eradicate Covid-19.

Iceland had over 1800 cases, and is still a few weeks away from being Covid-19 free.

Every Airbus A380 in the world is grounded – except for one airline

There are 237 Airbus A380s in the fleets of the world’s airlines. The biggest passenger jets ever, which can carry more people than any plane, have been a staple of long-haul travel since the late 2000s. But not anymore.

Now they are all grounded, rendered useless by the precipitous drop in travel demand this year due to the coronavirus crisis. The sight of huge double-deckers parked in the desert, dwarfing smaller planes and just as unable to fly profitably, is a perfect visual summation of the airline industry’s current troubles.

An Australian photographer captured poignant sunset images of Singapore Airlines A380s awaiting better days in Alice Springs, and posted them on Facebook.

Some $5billion worth of Aircraft from around the world now being holed up in the desert near Alice Springs due to COVID-19 travel downturn

Posted by Steve Strike on Sunday, May 3, 2020

The world’s A380s are all parked for storage — except five, all belonging to China Southern Airlines, the largest airline in Asia.

Sign up for the free daily TPG newsletter for more airline news

According to flight-tracking sites, China Southern is still sending A380s to Europe, North America and Australia, on regularly scheduled flights. Since China is barring foreigners from entering the country and leisure travel worldwide has essentially stopped, those A380s may be filled with cargo more than passengers. After all, using passenger jets as freighters is one way that airlines try to make money these days, as revenue has dried up.

That’s a somewhat ironic development, since China Southern is not — unlike, say, Emirates — a happy A380 customer, and even before the crisis was finding it hard to turn a profit on its A380 flights. “The A380’s large size makes it challenging to profitably fill,” an aviation analyst told the South China Morning Post in 2015. “At Emirates you have different economics since you have A380s feeding A380s for transfer traffic – that brings scale.”

In fact, when we sent our reviews intern to fly a China Southern A380 from Guangzhou to Los Angeles last year, he had the first-class cabin almost entirely to himself.

That Los Angeles route is one of the few where China Southern is using the double-decker giant. It also appears sporadically on flights from the airline’s Guangzhou home base to Amsterdam, Vancouver, Sydney and London. That’s a bizarre choice of destinations; China Southern has smaller long-haul aircraft that could cover these routes losing less money than a likely empty A380. Even if used as a cargo carrier, the A380 — built to maximize space for passengers, not freight — can haul less stuff in its cargo holds than a smaller Boeing 777.

But it does have a vast passenger cabin — the biggest around. That could come in handy when carrying boxes that do not need to go in the holds and can simply be fastened to seats, which is often the case with boxes containing masks and other protective equipment shipped from China.

A map from flight-tracking site Flightradar24 showed that on Friday morning, two China Southern flights were the only A380s airborne in the entire world. One was over Russia on the way home from Amsterdam; the other over the Philippines, headed to Australia.

The A380, for all its wonders like onboard showers and bars, has not been a commercial success, and Airbus has decided to stop making it this year. There will be no more sold to airlines, and certainly not in China, where the big three carriers — Air China, China Eastern and China Southern itself — all went from making a profit to losing lots of money due to the traffic slump. China was never a big market for the A380, despite Airbus’ efforts to sell there. China Southern was the only customer to bite, and even then it bought just five.

And yet, today a country where the flagship product of Europe’s aircraft industry never made a splash is the only one where it is still flying. It’s another bizarre, unforeseen consequence of the pandemic that has turned so much of the world on its head.

Featured image: A China Southern A380 lands at LAX in April 2016. Photo by Alberto Riva / The Points Guy

Food Banks Can’t Go On Like This

Today many Americans who have never needed help to feed their families are turning to charity as they struggle with the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

To better understand this crisis, I contacted a dozen different hunger-relief organizations that are scrambling to meet the sudden increase in demand. The level of need and vulnerability that their staffers described was alarming. These organizations’ resourcefulness under current circumstances is impressive. If nothing changes, though, they’ll run out of food and money. Government officials could help tremendously by making it easier for people to qualify for food stamps, even beyond recent emergency reforms, but public-assistance programs are often designed to limit enrollment rather than to guarantee nutrition to everyone thrown out of work during a global pandemic.

[Read: Who will run the soup kitchens?]

In San Diego County, the fifth most populous in the country, the nonprofit Feeding San Diego reports that demand at its 300 distribution sites is up at least 40 to 50 percent. “People who four weeks ago were living middle-class lives now find themselves in debt, without cash, unable to pay for their most essential needs,” Vince Hall, the group’s CEO, told me. The organization’s online “food finder” tool experienced such a big surge in traffic that its web-hosting provider levied a bandwidth penalty.

Meeting San Diego’s rise in demand has required adaptability. Normally, “rescued” food—items that would otherwise be thrown out as their sell-by date approaches—accounts for 97 percent of Feeding San Diego’s distributions. Until the pandemic, the group was receiving unpurchased food from 204 Starbucks locations every night of the year. Most of those stores are now closed. The organization normally gets excess food from 260 grocery stores too, but consumers have been stocking up enough lately that many shelves are picked clean.

In the first weeks of this crisis, the lack of food from these sources was offset by restaurants, hotels, and catering firms that donated their inventories as the shutdown began. But that was a onetime windfall—and some of it was food packaged in industrial sizes that work well in large commercial kitchens but poorly for parceling out to families. To compensate for the dearth of rescued food, Feeding San Diego is now purchasing wholesale in the same system where grocery stores themselves are accelerating orders. Food banks are also having to pay premium prices. The day we spoke, Hall authorized a $97,000 purchase of chicken and pork.

Facing Hunger Foodbank in West Virginia used to serve about 129,000 people on a typical day. Its executive director, Cynthia D. Kirkhart, witnessed the same sharp rise in demand after her state issued its stay-at-home order. Then the retail donations that the food bank receives from partners such as Walmart and Kroger shrank by roughly 90 percent, and delivery times for purchased food grew from a week to eight or 10 weeks. “Between March 30 and April 8, I placed orders in excess of $487,000 for food, and some of it won’t be arriving until late June, but at least I’ll have a regular influx coming in,” she told me. “My total budget for this year was about $500,000. My reworked budget is going to look more like $1.2 million to $1.5 million, and that’s with an optimistic outlook for what happens with this pandemic and how long we are in recovery.”

Kirkhart could swing that purchase because of reserves built up through frugality and fundraising. Big Sandy Superstore, a furniture retailer, has urged its customers to donate $50 to Facing Hunger to feed a family for a week. On Easter, the Dutch Miller Auto Group sponsored three church services on a local TV station and ran ads during breaks urging food-bank donations. “In an hour, there were 53 new donors,” she said. When food is donated directly, the logistics of sorting and distributing it are not simple, and Kirkhart’s group encourages people to give money when possible. The food bank can give out 7.5 meals per dollar, she said. “I can make $50 become magical with economies of scale.”

In Ventura County, California, the organization Food Share had been distributing 1 million pounds of food each month before the pandemic. That figure is now doubling. The Air National Guard is helping it to pack up boxes for drive-through pickup events. Its supply took a hit when the availability of food to rescue fell significantly. But California’s unusually large local agriculture industry makes securing fresh produce easier than in most American communities. “The abundance of surplus produce we’re seeing across the country is particularly concentrated in Ventura County, because we produce enough to feed a global market,” Food Share stated in a release. “We are distributing fresh produce with each pop-up distribution but at this time we do not have the resources or facilities to receive and distribute everything that is offered to us.”

[Read: Why the coronavirus is so confusing]

Alaska faces different circumstances. Headquartered in Anchorage, the Food Bank of Alaska is dealing with about 75 percent more demand than usual—in a state whose spread-out geography makes collection and distribution a particular challenge. Most food must be imported from elsewhere. And once that feat is accomplished, getting that food out to far-flung rural communities and into the hands of the needy involves a complex distribution channel. “Recently a prominent air carrier, RavnAir, declared bankruptcy and ceased operations. So there’s concern from smaller communities about how they’re going to get goods,” Cara Durr, the organization’s director of public engagement, told me. “Other airlines have stepped up to fill some gaps, but there’s not a lot of wiggle room in these systems.”

Getting food to needy children is harder than before with public schools shut down. The Food Bank of Alaska typically runs a summer program for kids too, but many of the organizations that help it pass food out haven’t yet signed on this year due to uncertainty about running a distribution site in a pandemic.

What would make feeding needy Alaskans easier?

When the federal government began giving out unemployment benefits of $600 a week beyond what states normally offer, many families got a necessary lifeline, but also found themselves exceeding the income eligibility requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the federal program formerly—and still colloquially—known as food stamps. Those people will need to reapply for SNAP when the unemployment benefits run out, Durr said.

Alaska is one of the states that doesn’t yet allow residents to sign up for SNAP online. Applications require a paper signature, despite the significant difficulties involved in travel to and from most rural communities. A recent waiver will allow the Food Bank of Alaska to use telephonic signatures once a system for them is set up. But administrative burden would be reduced if people kicked off of SNAP because of a brief spike in income didn’t need to reapply just weeks later.

The diverging circumstances in different regions underscore the importance of local knowledge in meeting the challenges ahead. But food-bank staffers in every area agreed that getting nutrition to people who need it is complicated by regulations meant to prevent people from abusing SNAP—some of them added as recently as last year. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act gave states permission to modify some needlessly onerous eligibility restrictions and procedures, but not all states have taken full advantage of that new flexibility, and hunger-relief advocates have called for additional reforms, such as expanding the ability to order food online.

More generous food-stamp benefits would help too. “We must provide more food assistance as more families struggle financially and our food banks strain to help,” the Representative Mike Doyle, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, wrote on Twitter, acknowledging that the strain on food banks will be reduced once families can meet more of their food needs using EBT cards to make purchases online and at supermarkets.

Especially in the months ahead, when social distancing will prevent many from returning to work and even mild unrest could prove hugely damaging to the country, the United States would be better off focusing on getting food to people who need it rather than keeping it from those who don’t.

“This is a moment of incredible anxiety and fear in our communities, and the health crisis is the primary fear everyone has. But the economic crisis is equally terrifying to people, and they are despondent over the lack of a path forward,” Hall, of Feeding San Diego, told me. “They don’t understand how long we are going to be in this environment and what it’s going to look like to get out of it.

“But when you put a box of food in somebody’s hands—let me revise that, because we use drive-through lanes now. When you put a box of food in somebody’s car, and you look through the windshield and give them a wave, sometimes they’re smiling and sometimes they’re crying, but for many, it is the one hopeful, optimistic, compassionate thing that will happen to them that entire day. And food is the most visceral human need. Without adequate nutrition, we can’t expect people to address any other challenge.”

Russia is rapidly becoming one of the world's coronavirus hotspots, and it just reported a record 10,000 new cases in a day

Lev Fedoseyev\TASS via Getty Images

Lev Fedoseyev\TASS via Getty Images

- Russia reported a record number of new coronavirus cases for the fourth consecutive day Sunday, as the virus rapidly spreads in the country, which is fast becoming one of the global epicenters of COVID-19.

- There were 10,633 new cases of COVID-19 confirmed on Sunday, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, some 1,000 more than were reported on Saturday, according to Worldometers data.

- A total of 134,687 people have now contracted the coronavirus in Russia, making it the seventh most-infected country on the planet.

- While in the early stages of the virus Russia was relatively unscathed, the number of cases is now increasing rapidly.

- "The peak is not behind us, we are about to face a new and grueling phase of the pandemic," President Vladimir Putin warned, according to CNN.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories.

Russia reported a record number of new coronavirus cases for the fourth consecutive day Sunday, as the virus rapidly spreads in the country, which is fast becoming one of the global epicenters of COVID-19.

There were 10,633 new cases of COVID-19 confirmed on Sunday, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, some 1,000 more than were reported on Saturday, according to Worldometers data.See the rest of the story at Business Insider

NOW WATCH: Inside London during COVID-19 lockdown

See Also:

- A nursing home in New York was forced to order a refrigerator truck to store corpses after reporting 98 coronavirus deaths in 'horrifying' outbreak

- A West Virginia worker told us what it was like living at his factory for 28 days to help make PPE, and says he would 'absolutely' do another 'lock-in' to help

- Donald Trump has once again changed his coronavirus deaths prediction to 'hopefully' under 100,000

Inside Coober Pedy, the Australian mining town where residents live, shop, and worship underground

Mark Kolbe/Getty Images

Mark Kolbe/Getty Images

- Coober Pedy is a small town in the Outback of Southern Australia.

- Originally an opal mining town, many of Coober Pedy's residents live underground to escape the region's immense heat.

- Homes, dive bars, a church, and more can be found buried underground in what the locals call "dugouts."

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories.

In the middle of the Australian Outback, there's a town where chimneys rise from the sand and big red signs warn people of "unmarked holes."

Welcome to Coober Pedy, the town that lives underground.

What began in 1916 as perhaps the largest opal mining operation in the world has since expanded into a subterranean community that is safely out of reach from the region's 120-degree summers.

Entire bedrooms, bookstores, churches, and bars are installed in the carved underground walls of Coober Pedy — and after 100 years of living in these "dugouts," the folks who call it home have no plans of stopping.

Here's a look inside the underground mining town of Coober Pedy.

Coober Pedy is located in South Australia, over 1,000 miles from Canberra, the country's capital city.

The town is referred to as the "opal capital of the world." Coober Pedy is an Aboriginal word that roughly translates to "white man in a hole."

The town's summer months can reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Even in the shade, it's common to feel temperatures of 100-plus. Much to the dismay of locals and visitors, there's little rainfall to provide relief from the harsh sun.

Due to the dry climate, water can be scarce sometimes.

Mark Kolbe/Getty Images

Mark Kolbe/Getty Images

According to ABC News, Coober Pedy sources its water from the Great Artesian Basin located about 15 miles away from the town.

See the rest of the story at Business Insider

See Also:

- Here's what life looks like right now in Singapore, where an outbreak in migrant worker dormitories has led to new lockdown measures

- The best hotels in Santa Fe

- The best hotels in Boston

The good, the bad, and the ugly

The Good: Do aggressive monetary stimulus to keep 2021 NGDP expectations on track. This involves level targeting combined with a “whatever it takes” approach to asset purchases. Buy only safe assets unless there are not enough safe assets to hit your target.

The Bad: Buy risky assets with newly created money in order to help the credit markets. Do enough to keep the credit markets flowing, but not enough to maintain adequate NGDP in 2021.

The Ugly: Bail out failing firms with fiscal policy. Let NGDP expectations collapse.

It looks like we’ve avoided the ugliest outcome, so give thanks for that:

Less than two months ago Boeing Co. went to Washington, hat in hand, asking for a $60 billion bailout for itself and its suppliers. The company, which had spent heavily on stock buybacks and was still reeling from the 737 Max disaster, was an unlikely candidate for government support.

Yet by urging the Federal Reserve to take unprecedented steps to bolster credit markets, the Trump administration ended up helping the plane maker more than any government handout could.

The Fed’s decision to use its near limitless balance sheet to purchase corporate bonds improved liquidity so much that it was a game changer for the company, according to people with knowledge of the matter who asked not to be identified because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

Notice how you do not need to directly bail out the corporate sector in order to save most big companies. For that same reason, a massive Fed purchase of T-bonds (and Treasury-backed MBSs) would have (indirectly) helped to provide liquidity in the corporate bond market. The key is maintaining expectations of adequate growth in NGDP. As long as NGDP expectations are on track and lenders know that nominal national income in 2021 will be sufficient to repay nominal debts, then the credit will flow.

Conventional monetary stimulus is the best option. Fed purchases of risky assets is second best. Fiscal stimulus is the worst.

Sunday morning quarterbacking

I was shocked to learn that the US had no plan to deal with a pandemic, and had not even done basic things like stockpile enough surgical masks or an adequate supply of testing equipment (or at least the ability to produce the testing equipment rapidly.)

Some people say this is “Monday morning quarterbacking”. It’s easy to throw stones after an event that “no one could have foreseen”.

OK, then today I’d like to do some Sunday morning quarterbacking. I’d like to ask you guys whether we are prepared for other black swans. Let’s start with a collapse of the electrical system due to solar flares or electromagnetic pulse attacks.

This 2019 article caught my eye:

In testimony before a Congressional Committee, it has been asserted that a prolonged collapse of this nation’s electrical grid—through starvation, disease, and societal collapse—could result in the death of up to 90% of the American population.

Well that caught my attention. It sounds worse than being cooped up for a few months watching lots of Netflix films.

HV transformers are the weak link in the system, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has identified 30 of these as being critical. The simultaneous loss of just 9, in various combinations, could cripple the network and lead to a cascading failure, resulting in a “coast-to coast blackout”.

If the HV transformers are irreparably damaged it is problematic whether they can be replaced. The great majority of these units are custom built. The lead time between order and delivery for a domestically manufactured HV transformer is between 12 and 24 months, and this is under benign, low demand conditions.

OK, I think I understand what needs to be done—stockpile some of these transformers that cannot be quickly replaced.

Ordered today, delivery of a unit from overseas (responsible for 85% of current American purchasing) would take nearly 3 years. The factory price for an HV transformer can be in excess of $10 million—too expensive to maintain an inventory solely as spares for emergency replacement.

Yes, $300 million dollars for a stockpile of 30 HV transformers is far too expensive to prevent 90% of the public dying and the rest reduced to cannibalism. Too much for a government that spends trillions of dollars with about as much care as a drunken sailor spending his wages in a red light district. Instead, let’s buy another F-22 jet fighter.

And people wonder why I’m so cynical.

Obviously I’m no expert here, and I expect commenters will tell me why I’m wrong. Perhaps the very same commenters who told me that I was foolish to think that surgical masks would provide any protection.

BTW, this isn’t one of those once in 60 million year events like dinosaur-killing asteroids; a huge solar flare hit Earth in 1859.

Update: I forget to mention that I’m far more worried about accidental nuclear war, bioterrorism and AI run amok than I am about solar flares.

This unlikely US airport just became the world’s busiest

JackNot as unlikely as it may seem considering it has always been a busy cargo airport and passenger traffic has tanked.

There have been many instances during this coronavirus pandemic where I’ve found myself questioning, “Is this real life?”

The whole situation feels so surreal. If you would’ve told me that I’d be stuck at home and not able to travel for the foreseeable future, I would’ve thought you were kidding.

Well folks, here we are — nearly two months into being stuck at home. With the world at a halt, we’ve witnessed a lot of interesting things. Adding to that list is Anchorage Airport (ANC) becoming the “busiest airport in the world” as of Saturday, April 25.

On Saturday, ANC was the world’s busiest airport for aircraft operations. This points to how significantly the global aviation system has changed and highlights the significance of our role in the global economy and fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. pic.twitter.com/z34ZmjoaKL

— Anchorage Airport (@ANCairport) April 28, 2020

On a typical day, busy hubs like Atlanta (ATL), Los Angeles (LAX), Dubai (DXB) and Beijing (PEK) hold some of the top spots, whereas Anchorage (ANC) is usually toward the end of the list. However, coronavirus has changed that completely.

For more TPG news delivered each morning to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter.

To put it into perspective, on Saturday, April 25, Anchorage (ANC) had 948 airport arrivals and departures, whereas London (LHR) had just 682 arrivals and departures, according to FlightRadar data.

So how did Anchorage (ANC) become the world’s busiest airport in the midst of coronavirus? Cargo operations, something the Alaskan airport is no stranger to. In fact, Anchorage usually tops the charts as the fifth busiest cargo airport in the world and second busiest cargo airport in the U.S. thanks to Alaska’s equidistant location between Asia and North America.

Related: What will US airline maps look like after coronavirus?

So while we’ve seen significant decreases in passenger flights overall with airlines being forced to slash routes — and in some cases, reconfigure routes all together — cargo flights haven’t been impacted quite as dramatically. Hence, why we’ve seen many commercial carriers start to carry cargo.

So here’s to the world’s new busiest airport!

Featured photo by chaolik/Getty Images.

Model this, coronavirus stupidity edition

A [NY] state guideline says nursing homes cannot refuse to take patients from hospitals solely because they have the coronavirus.

Here is the NYT article, with much more detail. Here is a previous MR post Claims About Nursing Homes. Via Megan McArdle.

And from a formal study:

Twenty-three days after the first positive test result in a resident at this skilled nursing facility, 57 of 89 residents (64%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The post Model this, coronavirus stupidity edition appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Whether or not we are living in a simulation, *they* are living in a simulation

JackI'm so out of it.

Savers at the Bank of Nook are being driven to speculate on turnips and tarantulas, as the most popular video game of the coronavirus era mimics global central bankers by making steep cuts in interest rates.

The estimated 12m players of Nintendo’s cartoon fantasy Animal Crossing: New Horizons were informed last week about the move, in which the Bank of Nook slashed the interest paid on savings from around 0.5 per cent to just 0.05 per cent.

The total interest available on any amount of savings has now been capped at 9,999 bells — the in-game currency that can be bought online at a rate of about $1 per 1.9m bells.

The abrupt policy shift, imposed by an obligatory software update on April 23, provoked a stream of online fury that a once-solid stream of income had been reduced to a trickle with the stroke of a raccoon banker’s pen.

“I’m never going to financially recover from this,” one player wrote on a Reddit forum. “Island recession incoming,” said another.

Here is more from the FT, via Malinga Fernando.

The post Whether or not we are living in a simulation, *they* are living in a simulation appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Give Yourself Gout For Fame And Profit

I.

Actually, no. You should not do this. Most of you were probably already not doing this, and I support your decision. But if you want a 2000 word essay on some reasons to consider this, and then some other reasons why those reasons are wrong, keep reading.

Gout is a disease caused by high levels of uric acid in the blood. Everyone has some uric acid in their blood, but when you get too much, it can form little crystals that get deposited around your body and cause various problems, most commonly joint pain. Some uric acid comes from chemicals found in certain foods (especially meat), so the first step for a gout patient is to change their diet. If that doesn’t work, they can take various chemicals that affect uric acid metabolism or prevent inflammation.

Gout is traditionally associated with kings, probably because they used to be the only people who ate enough meat to be affected. Veal, venison, duck, and beer are among the highest-risk foods; that list sounds a lot like a medieval king’s dinner menu. But as kings faded from view, gout started affecting a new class of movers and shakers. King George III had gout, but so did many of his American enemies, including Franklin, Jefferson, and Hancock (beginning a long line of gout-stricken US politicians, most recently Bernie Sanders). Lists of other famous historical gout sufferers are contradictory and sometimes based on flimsy evidence, but frequently mentioned names include Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Leonardo da Vinci, Martin Luther, John Milton, Isaac Newton, Ludwig von Beethoven, Karl Marx, Charles Dickens, and Mark Twain.

Question: isn’t this just a list of every famous person ever? It sure seems that way, and even today gout seems to disproportionately strike the rich and powerful. In 1963, Dunn, Brooks, and Mausner published Social Class Gradient Of Serum Uric Acid Levels In Males, showing that in many different domains, the highest-ranking and most successful men had the highest uric acid (and so, presumably, the most gout). Executives have higher uric acid than blue-collar workers. College graduates have higher levels than dropouts. Good students have higher levels than bad students. Top professors have higher levels than mediocre professors. DB&M admitted rich people probably still eat more meat than poor people, but didn’t think this explained the magnitude or universality of the effect. They proposed a different theory: maybe uric acid makes you more successful.

Before we mock them, let’s take more of a look at why they might think that, and at the people who have tried to flesh out their theory over the years.

Most animals don’t have uric acid in their blood. They use an enzyme called uricase to metabolize it into a harmless chemical called allantoin. About ten million years ago, the common ancestor of apes and humans got a mutation that broke uricase, causing uric acid levels to rise. The mutation spread very quickly, suggesting that evolution really wanted primates to have lots of uric acid for some reason. Since discovering this, scientists have been trying to figure out exactly what that reason was, with most people thinking it’s probably an antioxidant or neuroprotectant or something else helpful if you’re trying to evolve giant brains. Other researchers note that in lower animals, uric acid is a “come out of hibernation” sign which seems to induce energetic foraging and goal-directed behavior more generally.

Some of these people note the similarity between uric acid and caffeine:

If uric acid had caffeine-like effects, then high levels of uric acid in the blood would be like being on a constant caffeine drip. The exact numbers don’t really work out, but you can fix this by assuming uric acid is an order of magnitude or so weaker than straight caffeine. Add this fudge factor, and Benjamin Franklin was on exactly one espresso all the time.

But you can’t actually be hyperproductive by being on one espresso all the time, can you? Don’t you eventually gain tolerance to caffeine and lose any benefits?

Although uric acid is structurally similar to caffeine, it’s even more similar to a chemical called theacrine. In fact, theacrine is just 1,3,7,9-tetramethyl-uric acid:

Theacrine (not the same as theanine, be careful with this one!) is a caffeine-like substance found in an unusual Chinese variety of tea plant. It’s recently gained fame in the nootropic community for not producing tolerance the same way regular caffeine does – see eg Theacrine: Caffeine-Like Alkaloid Without Tolerance Build-Up. This makes the theory work even better: Franklin (and other gout sufferers) were constantly on one espresso worth of magic no-tolerance caffeine. Seems plausible!

II.

This theory is hilarious, but is it true?

I was able to find eleven studies comparing achievement and uric acid levels. I’ve put them into a table below.

| Study | sample size | finding | significant at | awfulness |

| Kasi | 155 tenth-graders | r = 0.28 w/ test scores | 0.001 | significant |

| Bloch | 84 med students | r = 0.23 w/ test scores | 0.05 | immense |

| Steaton & Herron | 817 army recruits | r = 0.07 w/ test scores | 0.02 | significant |

| Mueller & French | 114 professors | r = 0.5 with achievement-oriented behavior | 0.01 | astronomical |

| Montoye & Mikkelsen | 467 high-schoolers | negative result | N/A | unclear |

| Cervini & Zampa | 270 children | positive result | unknown | what even is this? |

| Inouye & Park | ??? | r = 0.33 with IQ | 0.025 | what even is this? |

| Anumonye | 100 businessmen, 40 controls | r = 0.21 with drive | 0.05 | immense |

| Ooki | 88 twins | r = 0.17 with 'rhathymia' | 0.05 | how is this even real? |

| Dunn I | 58 executives | positive | ??? | immense |

| Dunn II | 10 medical students | negative | N/A | astronomical |

Nine out of eleven are positive. But I find it hard to be confident in any of them. Modern studies can be pretty bad, but studies from the 1960s ask you to take even more things on trust, while inspiring a lot less of it. Many of these studies were unable to find the outcomes that the others found, but discovered new outcomes of their own. Many failed to report basic pieces of information. The largest experiments usually found the least impressive results. Overall this looks a lot like you would expect from something forty years before anyone realized there was a replication crisis.

I also notice that the most positive studies compare business executives to people in other walks of life, and the least positive studies compare good students with bad students. Business executives get a lot of chances to differ from the general population – maybe they still eat more meat and richer food? Maybe they’re stressed and stress affects uric acid levels?

What about the list of very famous people with gout? I agree it’s a lot of people, but what’s the base rate? Kings were born to their position, so we have no reason to think they were especially high achievers (someone in their family might have been, but that gene could have gotten pretty diluted). Since so many kings got gout, this suggests rich old people in the past had gout pretty often regardless of achievement. Also, this was before people invented good medical diagnosis, so probably arthritis, injuries, and any other form of joint pain got rounded off to gout too. What percent of rich old people in the past had some kind of joint pain? I’m prepared to guess “a lot”.

The biochemists report equally confusing results around the uric acid / caffeine connection. Caffeine mostly works by antagonizing adenosine, a chemical involved in sleepiness. According to Hunter et al, Effects of uric acid and caffeine on A1 adenosine receptor binding in developing rat brain, uric acid does not affect adenosine, and so probably does not have a caffeine-like mechanism of action. On the other hand, caffeine probably has a small additional effect on catecholamine (eg dopamine, norepinephrine) release, and a different paper finds that uric acid does share this mechanism. So it doesn’t have caffeine’s main effect, but it does seem to have some kind of mild stimulant properties.

Given this level of uncertainty around every step in the hypothesis, I would describe any link between uric acid and achievement as kind of a stretch at this point. I feel bad about this, because it’s an elegant theory with mostly positive studies in support, but I’m just not feeling like it’s met its burden of proof.

III.

But some recent research is trying to bring this field back from the dead. At least this is what I get from Ortiz et al, Purinergic System Dysfunction In Mood Disorders, which synthesizes some more modern evidence that “uric acid and purines (such as adenosine) regulate mood, sleep, activity, appetite, cognition, memory, convulsive threshold, social interaction, drive, and impulsivity”. It argues that we know there are neurorecptors for adenosine (another similar-looking molecule) and ATP (adenosine triphosphate, the body’s main form of chemical energy). These seem to be involved in depression and mania, in the predicted direction (manic people have too much ATP, depressed people have too little, and treatments for both conditions seem to normalize ATP levels). These results seem to be daring someone to make up a theory where mania is just too much chemical energy floating around, but if Ortiz et al are doing that, it’s sandwiched in between so many dense paragraphs on receptor binding that I can’t make it out.

More interesting for us, uric acid is related to all these chemicals and also seems to be involved in mania. See eg de Berardis et al, Evaluation of plasma antioxidant levels during different phases of illness in adult patients with bipolar disorder, which finds that uric acid is elevated in manic patients, and the more manic, the higher the uric acid levels. And Machado-Vieria claims to have gotten pretty good results treating bipolar mania with allopurinol, a gout medication that decreases uric acid – and the more the allopurinol decreased uric acid, the better the results. There’s also a little evidence that depressed people have lower uric acid than normal. None of this is a large effect – there are still a lot of depressed people with higher-than-normal uric acid and a lot of manic people with lower – but it’s around the same size as all the other infuriatingly suggestive effects we find in psychiatry that never lead to overarching theories or go anywhere useful.

Future studies should try to replicate the link between uric acid and mania, and come up with a better understanding of why it might be true – maybe since uric acid is a decay product of ATP, the body interprets it as a sign that energy is plentiful? They should try to explain away anomalies – if gout is maniogenic, how come so many people with gout are depressed? Is it just because having a painful illness is inherently depressing? And then it should investigate how mania bleeds into normal personality. Is someone with slightly higher uric acid a tiny bit hypomanic all the time?

If they can fill in all those steps, I’ll be willing to take a fresh look at the old papers linking gout and achievement. Until then, you should probably hold off on eating megadoses of venison to become the next Ben Franklin.

My dad’s covid-19 illness is mild. Many others aren’t so lucky.

Random thoughts on the pandemic

“I don’t think any country has a perfect record,” Bill Gates said in a recent interview. “Taiwan comes close.” . . . Taiwan seems to have followed the model recommended by disaster expert Vaughan: It doesn’t expect infallibility from its leaders. Instead, Taiwan makes sure that its health institutions are hyper-vigilant about epidemic risks. After the SARS epidemic of 2003, Taiwan set up an interlocking set of agencies geared toward the early detection of pandemics and bioterrorism. If a threat is detected, containment plans and supply stockpiles are ready. That process starts at the bottom, not the top.

Vaughan and other researchers note that complacency is usually fed by groupthink. At a time when China and the World Health Organization were downplaying the coronavirus threat, it was easy for world leaders to believe that everything was under control. Meanwhile, China has used its influence to keep Taiwan out of the WHO and other international organizations, and Samson Ellis, the Taipei bureau chief for Bloomberg News, believes that Taiwan’s isolation from WHO paradoxically helped the country by forcing it to rely on its own judgment on health issues.

“Taiwan knows it’s on its own,” he says.

In January, while other countries were trusting the WHO’s bland assurances, Taiwan was already turning away cruise ships and performing health checks at airports. Taking early action against COVID-19 meant defying a consensus shared by much of the world. The country’s public-health institutions were designed to be sensitive to even faint signs of trouble and to guard against optimistic biases.

Read the whole things (by James Meigs.) Taiwan is rapidly becoming one of my very favorite countr . . . er . . . places.

They also make outstanding films.

2. Bill Gates has been great, but here he’s a bit too soft on China:

He is impatient too about attacks on China for its lack of openness about Covid-19 and particularly its reluctance to allow non-Chinese experts to investigate the origins of the coronavirus outbreak in the city of Wuhan. “Sure, they should be open, but what is it that people are saying they’re not being open about? Every country has a lot you can criticise,” he said.

“Most people, whenever something new comes along, they take their classic criticisms of that country and just repeat them. But here we should get concrete. I don’t see any deep insights that are missing in terms of the origin of the disease that somebody is holding something back.”

I have a more centrist position on China—harshly critical of their government’s initial cover-up, which imposed great hardship on the Chinese people, and (like Bill Gates) dismissive of Westerners who want to blame our current policy failures on China.

3. Fortunately, while the US government tries to launch a cold war against China, private sector actors are trying to work with Chinese scientists in a constructive fashion:

US scientists are working with China to investigate the origin of coronavirus, despite criticism from the Trump administration that Beijing is failing to co-operate with outsiders to stem the disease.

Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, said he was working with a team of Chinese researchers to determine whether coronavirus emerged in other parts of China before it was first discovered in Wuhan in December. The effort relies on help from the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. This is great news:

After Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston began requiring that nearly everyone in the hospital wear masks, new coronavirus infections diagnosed in its staffers dropped by half — or more.

Brigham and Women’s epidemiologist Dr. Michael Klompas said the hospital mandated masks for all health care staffers on March 25, and extended the requirement to patients as well on April 6.

But they should have started on March 1st.

5. We have lots of testing capability that is not being used due to regulatory barriers:

As the United States struggles to test people for COVID-19, academic laboratories that are ready and able to run diagnostics are not operating at full capacity.

A Nature investigation of several university labs certified to test for the virus finds that they have been held up by regulatory, logistic and administrative obstacles, and stymied by the fragmented US health-care system. Even as testing backlogs mounted for hospitals in California, for example, clinics were turning away offers of testing from certified academic labs because they didn’t use compatible health-record software, or didn’t have existing contracts with the hospital. Researchers warn that if such hurdles remain, labs trying to join the effort to fight coronavirus might end up spinning their wheels.

This is insane. We need deregulation and we need more price gouging.

6. It’s possible that the virus escaped from a lab, but it’s about a million times more likely that it infected a random person in Southeast Asia:

Next, he says, consider the data he’s collected on people near bat caves getting exposed to viruses: “We went out and surveyed a population in Yunnan, China — we’d been to bat caves and found viruses that we thought could be high risk. So we sample people nearby, and 3 percent had antibodies to those viruses,” he says. “So between the last two and three years, those people were exposed to bat coronaviruses. If you extrapolate that population across the whole of Southeast Asia, it’s 1 million to 7 million people a year getting infected by bat viruses.”

Compare that, he says, to what we know about the labs: “If you look at the labs in Southeast Asia that have any coronaviruses in culture, there are probably two or three and they’re in high security. The Wuhan Institute of Virology does have a small number of bat coronaviruses in culture. But they’re not [the new coronavirus], SARS-CoV-2. There are probably half a dozen people that do work in those labs. So let’s compare 1 million to 7 million people a year to half a dozen people; it’s just not logical.”

In addition, a cover-up is very unlikely:

Carroll, the former director of USAID’s emerging threats division who also spent years working with emerging infectious disease scientists in China, agrees that there’s no evidence the Chinese researchers were working with a novel pathogen. His reasoning? He would have heard about it.

“The reason I’m not putting a lot of weight on [the lab-escape theory] is there was no chatter prior to the emergence of this virus to a discovery that would have ended up bringing the virus into a lab,” he says. “And if nothing else, the scientific community tends to be very gossipy. If there is a novel, potentially dangerous virus which has been identified, circulating in nature, and it’s brought into a laboratory, there is chatter about that. And when you look back retrospectively, there’s no chatter whatsoever about the discovery of a new virus.”

And if these viruses infect millions of people each year, then why is it so important if that person happens to work in a lab?

7. I usually agree with Ramesh Ponnuru, but here I think he’s being a bit too kind to the US:

America Isn’t Actually Doing So Badly Against Coronavirus

I agree with Ponnuru that it’s silly to focus on Trump, as if another president would have made a big difference. And I agree that it was almost inevitable that our response would be messy and full of mistakes (as James Meigs pointed out in the article I linked to on top).

But let’s not mince words; we (including myself) have done very poorly. We have 4% of the world’s population and 27% (and rising) of fatalities. Even accounting for errors in the data, we are doing much worse than average. Yes, some countries have done even worse, but that just means they’ve also done poorly.

Many countries have done far better than the US. If we do far worse than South Korea, Australia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Japan, Germany and Austria, I don’t get much consolation from the fact that we are doing better than Italy, Spain, France and the UK. We are supposed to be a global leader in technology and state capacity.

I also think this is a bit too optimistic:

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates and expanded lending facilities, moving, like Congress, faster than it had during the financial crisis of a dozen years ago.

Yes, they’ve done some very good things, and this crisis is more severe than 2008. But the bottom line is that we are currently making the same mistakes as in 2008, failing to adopt level targeting and allowing price level/NGDP expectations for 2022 to fall sharply. Level targeting isn’t an extreme idea; people both inside and outside the Fed know it’s the right thing to do right now. It’s just institutional inertia holding them back.

(I.e., if we already had level targeting there is zero chance the Fed would switch back to growth rate targeting right now. That’s what I mean by “inertia”.)

8. On the lighter side, I just LOVE Japan:

Hokkaido has now had to re-impose the restrictions, though Japan’s version of a Covid-19 “lockdown” is a rather softer than those imposed elsewhere.

Most people are still going to work. Schools may be closed, but shops and even bars remain open.

Bars open, schools closed. I recall on my 2018 visit to Japan that you could buy booze from a vending machine:

The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City

New York City’s multitentacled subway system was a major disseminator – if not the principal transmission vehicle – of coronavirus infection during the initial takeoff of the massive epidemic that became evident throughout the city during March 2020. The near shutoff of subway ridership in Manhattan – down by over 90 percent at the end of March – correlates strongly with the substantial increase in the doubling time of new cases in this borough. Maps of subway station turnstile entries, superimposed upon zip code-level maps of reported coronavirus incidence, are strongly consistent with subway-facilitated disease propagation. Local train lines appear to have a higher propensity to transmit infection than express lines. Reciprocal seeding of infection appears to be the best explanation for the emergence of a single hotspot in Midtown West in Manhattan. Bus hubs may have served as secondary transmission routes out to the periphery of the city.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Jeffrey E. Harris.

The post The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Spit Works

JackBleh. I got the nasal swab.

A new paper finds that COVID-19 can be detected in saliva more accurately than with nasal swab. As I mentioned earlier a saliva test will lessen the need for personnel with PPE to collect samples.

Rapid and accurate SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic testing is essential for controlling the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The current gold standard for COVID-19 diagnosis is real-time RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal swabs. Low sensitivity, exposure risks to healthcare workers, and global shortages of swabs and personal protective equipment, however, necessitate the validation of new diagnostic approaches. Saliva is a promising candidate for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics because (1) collection is minimally invasive and can reliably be self-administered and (2) saliva has exhibited comparable sensitivity to nasopharyngeal swabs in detection of other respiratory pathogens, including endemic human coronaviruses, in previous studies. To validate the use of saliva for SARS-CoV-2 detection, we tested nasopharyngeal and saliva samples from confirmed COVID-19 patients and self-collected samples from healthcare workers on COVID-19 wards. When we compared SARS-CoV-2 detection from patient-matched nasopharyngeal and saliva samples, we found that saliva yielded greater detection sensitivity and consistency throughout the course of infection. Furthermore, we report less variability in self-sample collection of saliva. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that saliva is a viable and more sensitive alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs and could enable at-home self-administered sample collection for accurate large-scale SARS-CoV-2 testing.

The FDA has also just approved an at-home test collected by nasal swab, a saliva test should not be far behind.

Hat tip: Cat in the Hat.

The post Spit Works appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

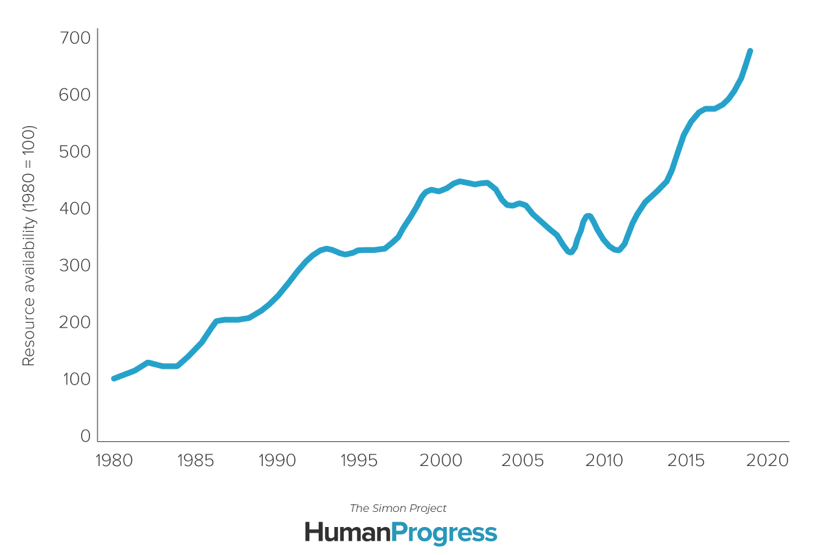

Happy Earth Day! Simon Abundance Index Reports That Earth Is 570.9 Percent More Abundant in 2019 Than It Was in 1980.

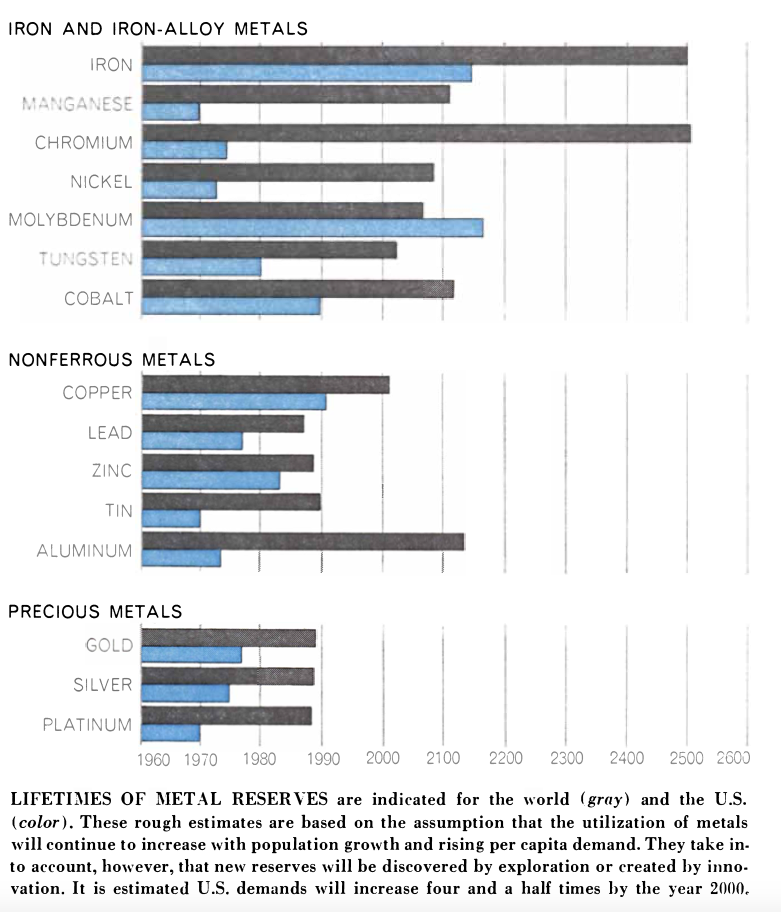

Harrison Brown of the National Academy of Sciences published a chart in the September 1970 issue of Scientific American projecting that humanity would run out of copper shortly after 2000; lead, zinc, tin, gold, and silver would be gone before 1990. Brown claimed that his estimates took into account the possibilities that "new reserves will be discovered by exploration or created by innovation." The February 2, 1970, issue of Time quoted the ecologist Kenneth Watt: "By the year 2000, if present trends continue, we will be using up crude oil at such a rate…that there won't be any more crude oil."

I report these dire prognostications from five decades ago in my column Earth Day Turns 50.

Today economist Gale L. Pooley and Human Progress website proprietor Marian L. Tupy show how badly mistaken these prophecies of imminent resource depletion have turned in their updated Simon Abundance Index calculations. The index is named after University of Maryland economist Julian Simon, who won his famous bet on resource trends in 1990 against perennial doomsayer Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich.

In October 1980, Ehrlich and Simon drew up a futures contract obligating Simon to sell Ehrlich the same quantities that could be purchased for $1,000 of five metals (copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten) 10 years later at 1980 prices. If the combined prices rose above $1,000, Simon would pay the difference. If they fell below $1,000, Ehrlich would pay Simon the difference. In October 1990, Ehrlich mailed Simon a check for $576.07. There was no note in the letter. The price of the basket of metals chosen by Ehrlich and his cohorts had fallen by more than 50 percent.

Tupy and Pooley calculate the index using "time price" as a way to measure resource abundance. "The time price denotes the amount of time that a person has to work in order to earn enough money to buy something. To calculate the time price, the nominal money price is divided by nominal hourly income," they explain.

Using this measure, they report:

The average time price of 50 commodities fell by 74.2 percent. That means that for the same length of time that a person needed to work to earn enough money to buy one unit in our basket of 50 commodities in 1980, he or she could buy 3.87 units in 2019. In other words, the average person saw his or her level of abundance rise by 287.4 percent. That amounts to a compound annual growth rate of 3.63 percent and implies a doubling of abundance every 19.45 year.

The index has a base year of 1980 and a base value of 100. In 2019, the Index reached a level of 670.9. That is to say that the Earth as a whole was 570.9 percent more abundant in 2019 than it was in 1980.

How is this possible? Tupy and Pooley explain:

Simon's revolutionary insights with regard to the mutually beneficial interaction between population growth and availability of natural resources, which our research confirms, may be counterintuitive, but they are real. The world's resources are finite in the same way that the number of piano keys is finite. The instrument has only 88 notes, but those can be played in an infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet. The Earth's atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.

Happy Earth Day, everybody!

The Amish Health Care System

I.

Amish people spend only a fifth as much as you do on health care, and their health is fine. What can we learn from them?

A reminder: the Amish are a German religious sect who immigrated to colonial America. Most of them live apart from ordinary Americans (who they call “the English”) in rural communities in Pennsylvania and Ohio. They’re famous for their low-tech way of life, generally avoiding anything invented after the 1700s. But this isn’t absolute; they are willing to accept technology they see as a net positive. Modern medicine is in this category. When the Amish get seriously ill, they will go to modern doctors and accept modern treatments.

The Muslims claim Mohammed was the last of the prophets, and that after his death God stopped advising earthly religions. But sometimes modern faiths will make a decision so inspired that it could only have come from divine revelation. This is how I feel about the Amish belief that health insurance companies are evil, and that good Christians must have no traffic with them.

And Deists believe that God is like a watchmaker, an artisan who built the world but does not act upon it. But by some miracle, the US government played along and granted the Amish exemptions from all the usual health care laws. They don’t have to pay Medicare taxes or social security. They aren’t included in the Obamacare mandate. They can share health care costs the way they want, ignoring any regulations to the contrary. They are genuinely on their own.

They’ve ended up with a simple system based on church aid. Everyone pays tithes to their congregation (though they don’t call it that). The churches meet in houses and have volunteer leaders, so expenses minimal. Most of the money goes to “alms” which the bishop distributes to members in need. This replaces the social safety net, including health insurance. Most Amish go their entire life without needing anything else.

About a third of Amish are part of a more formal insurance-like institution called Amish Hospital Aid. Individuals and families pay a fixed fee to the organization, which is not-for-profit and run by an unpaid board of all-male elders. If they need hospital care, AHA will pay for it. How does this interact with the church-based system? Rohrer and Dundes, my source for most of this post, say that it’s mostly better-off Amish who use AHA. Their wealth is tied up in their farmland, so it’s not like they can use it to pay hospital bills. But they would feel guilty asking their church to give them alms meant for the poor. AHA helps protect their dignity and keep church funds for those who need them most.

How well does this system work?

The Amish outperform the English on every measured health outcome. 65% of Amish rate their health as excellent or very good, compared to 58% of English. Diabetes rates are 2% vs. 8%, heart attack rates are 1% vs. 6%, high blood pressure is 11% vs. 31%. Amish people go to the hospital about a quarter as often as English people, and this difference is consistent across various categories of illness (the big exception is pregnancy-related issues – most Amish women have five to ten children). This is noticeable enough that lots of health magazines have articles on The Health Secrets of the Amish and Amish Secrets That Will Add Years To Your Life. As far as I can tell, most of the secret is spending your whole life outside doing strenuous agricultural labor, plus being at a tech level two centuries too early for fast food.

But Amish people also die earlier. Lots of old studies say the opposite – for example, this one finds Amish people live longer than matched Framingham Heart Study participants. But things have changed since Framingham. The Amish have had a life expectancy in the low 70s since colonial times, when the rest of us were dying at 40 or 50. Since then, Amish life expectancy has stayed the same, and English life expectancy has improved to the high 70s. The most recent Amish estimates I have still say low seventies, so I think we are beating them now.

If they’re healthier, why is their life expectancy lower? Possibly they are less interested in prolonging life than we are. R&D write:

Amish people are more willing to stop interventions earlier and resist invasive therapies than the general population because, while they long for healing, they also have a profound respect for God’s will. This means taking modest steps toward healing sick bodies, giving preference to natural remedies, setting common-sense limits, and believing that in the end their bodies are in God’s hands.

The Amish health care system has an easier job than ours does. It has to take care of people who are generally healthy and less interested in extreme end-of-life care. It also supports a younger population – because Amish families have five to ten children, the demographics are weighted to younger people. All of these make its job a little bit simpler, and we should keep that in mind for the following sections.

How much do the Amish pay for health care? This is easy to answer for Amish Hospital Aid, much harder for the church system.

Amish Hospital Aid charges $125 monthly per individual or $250 monthly per family (remember, Amish families can easily be ten people). Average US health insurance costs $411 monthly per individual (Obamacare policies) or $558 monthly per individual (employer sponsored plan; employers pay most of this). I’m not going to bother comparing family plans because the definition of “family” matters a lot here. On the surface, it looks like the English spend about 4x as much as the Amish do.

But US plans include many more services than AHA, which covers catastrophic hospital admissions only. The government bans most Americans from buying plans like this; they believe it’s not enough to count as real coverage. The cheapest legal US health plan varies by age and location, but when I take my real age and pretend that I live near Amish country, the government offers me a $219/month policy on Obamacare. This is only a little higher than what the Amish get, and probably includes more services. So here it seems like the Amish don’t have much of an efficiency advantage. They just make a different tradeoff. It’s probably the right tradeoff for them, given their healthier lifestyle.

But remember, only a third of Amish use AHA. The rest use a church-based system? How does that come out?

It’s hard to tell. Nobody agrees on how much Amish tithe their churches, maybe because different Amish churches have different practices. R&D suggest families tithe 10% of income, this article on church-based insurances says a flat $100/month fee, and this “Ask The Amish” column says that churches have twice-yearly occasions where they ask for donations in secret and nobody is obligated to give any particular amount (“often husbands and wives won’t even know how much the other is giving.”) So it’s a mess, and even knowing the exact per-Amish donation wouldn’t help, because church alms cover not just health insurance but the entire social safety net; the amount that goes to health care probably varies by congregation and circumstance.

A few people try to estimate Amish health spending directly. This ABC story says $5 million total for all 30,000 Amish in Lancaster County, but they give no source, and it’s absurdly low. This QZ story quotes Amish health elder Marvin Wengerd as saying $20 – $30 million total for Lancaster County, which would suggest health spending of between $600-$1000 per person. This sounds potentially in keeping with some of the other estimates. A $100 per month tithe would be $1200 per year – if half of that goes to non-health social services, that implies $600 for health. The average Amish family earns about $50K (the same as the average English family, somehow!) so a 10% tithe would be $5000 per year, but since the average Amish family size is seven children, that comes out to about $600 per person again. So several estimates seem to agree on between $600 and $1000 per person.

One possible issue with this number: does Wengerd know how much Amish spend out of pocket? Or does his number just represent the amount that the official communal Amish health system spends? I’m not sure, but taking his words literally it’s total Amish spending, so I am going to assume it’s the intended meaning. And since the Amish rarely see doctors for minor things, probably their communal spending is a big chunk of their total.

[Update: an SSC reader is able to contact his brother, a Mennonite deacon, for better numbers. He says that their church spends an average of $2000 per person (including out of pocket).]

How does this compare to the US as a whole? The National Center For Health Statistics says that the average American spends $11,000 on health care. This suggests that the average American spends between five and ten times more on health care than the average Amish person.

How do the Amish keep costs so low? R&D (plus a few other sources) identify some key strategies.

First, the Amish community bargains collectively with providers to keep prices low. This isn’t unusual – your insurance company does the same – but it nets them better prices than you would get if you tried to pay out of pocket at your local hospital. This article gives some examples of Amish getting sticker prices discounted from between 50% to 66% with this tactic alone; Medicare gets about the same.

Second, the Amish are honorable customers. This separates them from insurance companies, who are constantly trying to scam providers however they can. Much of the increase in health care costs is “administrative expenses”, and much of these administrative expenses is hiring an army of lawyers, clerks, and billing professionals to thwart insurance companies’ attempts to cheat their way out of paying. If you are an honorable Amish person and the hospital knows you will pay your bill on time with zero fuss, they can waive all this.

But can this really be the reason Amish healthcare is cheaper? When insurance companies negotiate with providers, patients are on the side of the insurances; when insurance companies get good deals (eg a deal of zero dollars because the insurance has scammed the hospital), the patient’s care is cheaper, and the insurance company can pass some of those savings down as lower prices. If occasionally scamming providers meant insurance companies had to pay more money total, then they would stop doing it. My impression is that the real losers here are uninsured patients; absent any pressure to do otherwise, hospitals will charge them the sticker price, which includes the dealing-with-insurance-scams fee. The Amish successfully pressure them to waive that fee, which gets them better prices than the average uninsured patient, but still doesn’t land them ahead of insured people.

Third, Amish don’t go to the doctor for little things. They either use folk medicine or chiropractors. Some of the folk medicine probably works. The chiropractors probably don’t, but they play a helpful role reassuring people and giving them the appropriate obvious advice while telling the really serious cases to seek outside care. With this help, Amish people mostly avoid primary care doctors. Holmes County health statistics find that only 16% of Amish have seen a doctor in the past year, compared to 54% of English.

Fourth, the Amish never sue doctors. Doctors around Amish country know this, and give them the medically indicated level of care instead of practicing “defensive medicine”. If Amish people ask their doctors to be financially considerate – for example, let them leave the hospital a little early – their doctors will usually say yes, whereas your doctor would say no because you could sue them if anything went wrong. In some cases, Amish elders formally promise that no member of their congregation will ever launch a malpractice lawsuit.

Fifth, the Amish don’t make a profit. Church aid is dispensed by ministers and bishops. Even Amish Hospital Aid is run by a volunteer board. None of these people draw a salary or take a cut. I don’t want to overemphasize this one – people constantly obsess over insurance company profits and attribute all health care pathologies to them, whereas in fact they’re a low single-digit percent of costs (did you know Kaiser Permanente is a nonprofit? Hard to tell, isn’t it?) But every little bit adds up, and this is one bit.

Sixth, the Amish don’t have administrative expenses. Since the minister knows and trusts everyone in his congregation, the “approval process” is just telling your minister what the problem is, and the minister agreeing that’s a problem and giving you money to solve it. This sidesteps a lot of horrible algorithms and review boards and appeal boards and lawyers. I don’t want to overemphasize this one either – insurance companies are legally required to keep administrative expenses low, and most of them succeed. But again, it all adds up.

Seventh, the Amish feel pressure to avoid taking risks with their health. If you live in a tiny community with the people who are your health insurance support system, you’re going to feel awkward smoking or drinking too much. Realistically this probably blends into a general insistence on godly living, but the health insurance aspect doesn’t hurt. And I’m talking like this is just informal pressure, but occasionally it can get very real. R&D discuss the case of some Amish teens who get injured riding a snowmobile – forbidden technology. Their church decided this was not the sort of problem that godly people would have gotten themselves into, and refused to help – their families were on the hook for the whole bill.

Eighth, for the same reason, Amish try not to overspend on health care. I realize this sounds insulting – other Americans aren’t trying? I think this is harsh but true. Lots of Americans get an insurance plan from their employer, and then consume health services in a price-insensitive way, knowing very well that their insurance will pay for it. Sometimes they will briefly be limited by deductibles or out-of-pocket charges, but after these are used up, they’ll go crazy. You wouldn’t believe how many patients I see who say things like “I’ve covered my deductible for the year, so you might as well give me the most expensive thing you’ve got”, or “I’m actually feeling fine, but let’s have another appointment next week because I like talking to you and my out-of-pocket charges are low.”

But it’s not just avoiding the obvious failure modes. Careful price-shopping can look very different from regular medical consumption. Several of the articles I read talked about Amish families traveling from Pennsylvania to Tijuana for medical treatment. One writer describes Tijuana clinics sending salespeople up to Amish Country to advertise their latest prices and services. For people who rarely leave their hometown and avoid modern technology, a train trip to Mexico must be a scary experience. But prices in Mexico are cheap enough to make it worthwhile.

Meanwhile, back in the modern world, I’ve written before about how a pharma company took clonidine, a workhorse older drug that costs $4.84 a month, transformed it into Lucemyra, a basically identical drug that costs $1,974.78 a month, then created a rebate plan so that patients wouldn’t have to pay any extra out-of-pocket. Then they told patients to ask their doctors for Lucemyra because it was newer and cooler. Patients sometimes went along with this, being indifferent between spending $4 of someone else’s money or $2000 of someone else’s money. Everything in the US health system is like this, and the Amish avoid all of it. They have a normal free market in medical care where people pay for a product with their own money (or their community’s money) and have incentives to check how much it costs before they buy it. I do want to over-emphasize this one, and honestly I am surprised Amish health care costs are only ten times cheaper than ours are.

I don’t know how important each of these factors is, or how they compare to more structural factors like younger populations, healthier lifestyles, and less end-of-life care. But taken together, they make it possible for the Amish to get health care without undue financial burden or government support.

II.

Why look into the Amish health system?

I’m fascinated by how many of today’s biggest economic problems just mysteriously failed to exist in the past. Our grandparents easily paid for college with summer jobs, raised three or four kids on a single income, and bought houses in their 20s or 30s and never worried about rent or eviction again. And yes, they got medical care without health insurance, and avoided the kind of medical bankruptcies we see too frequently today. How did this work so well? Are there ways to make it work today? The Amish are an extreme example of people who try to make traditional systems work in the modern world, which makes them a natural laboratory for this kind of question.

The Amish system seems to work well for the Amish. It’s hard to say this with confidence because of all the uncertainties. The Amish skew much younger than the “English”, and live much healthier lifestyles. Although a few vague estimates suggest health care spending far below the English average, they could be missing lots of under-the-table transactions. And again, I don’t want to ignore the fact that the Amish do live a little bit shorter lives. You could tell a story where all of these add up to explain 100% of the difference, and the Amish aren’t any more efficient in their spending at all. I don’t think this is right. I think the apparent 5x advantage, or something like it, is real. But right now this is just a guess, not a hard number.

What if it is? It’s hard to figure out exactly what it would take to apply the same principles to English society. Only about a quarter of Americans attend church regularly, so church-based aid is out. In theory, health insurance companies ought to fill the same niche, with maybe a 10% cost increase for profits and overhead. Instead we have a 1000% cost increase. Why?

Above, I said that the most important factor is that the Amish comparison shop. Everyone needs to use other people’s money to afford expensive procedures. But for the Amish, those other people are their fellow church members and they feel an obligation to spend it wisely. For the English, the “other people” are faceless insurance companies, and we treat people who don’t extract as much money as possible from them as insufficiently savvy. But there’s no easy way to solve this in an atomized system. If you don’t have a set of thirty close friends you can turn to for financial help, then the only institutions with enough coordination power to make risk pooling work are companies and the government. And they have no way of keeping you honest except the with byzantine rules about “prior authorizations” and “preferred alternatives” we’ve become all too familiar with.

(and as bad as these are, there’s something to be said for a faceless but impartial bureaucracy, compared to having all your neighbors judging your lifestyle all the time.)

This is a neat story, but I have two concerns about it.

First, when I think in terms of individual people I know who have had trouble paying for health care, it’s hard for me to imagine the Amish system working very well for them. Many have chronic diseases. Some have mysterious pain that they couldn’t identify for years before finally getting diagnosed with something obscure. Amish Hospital Aid’s catastrophic policy would be useless for this, and I feel like your fellow church members would get tired of you pretty quickly. I’m not sure how the Amish cope with this kind of thing, and maybe their system relies on a very low rate of mental illness and chronic disease. A lot of the original “hygiene hypothesis” work was done on the Amish, their autoimmune disease rates are amazing, and when you take out the stresses of modern life maybe a lot of the ailments the American system was set up to deal with just stop being problems. I guess my point is that the numbers seem to work out, and the Amish apparently remain alive, but when I imagine trying to apply the Amish system to real people, even assuming those real people have cooperative churches and all the other elements I’ve talked about, I can’t imagine it doing anything other than crashing and burning.

Second, I don’t think this is actually how our grandparents did things. I asked my literal grandmother, a 95 year old former nurse, how health care worked in her day. She said it just wasn’t a problem. Hospitals were supported by wealthy philanthropists and religious organizations. Poor people got treated for free. Middle class people paid as much as they could afford, which was often the whole bill, because bills were cheap. Rich people paid extra for fancy hospital suites and helped subsidize everyone else. Although most people went to church or synagogue, there wasn’t the same kind of Amish-style risk pooling.