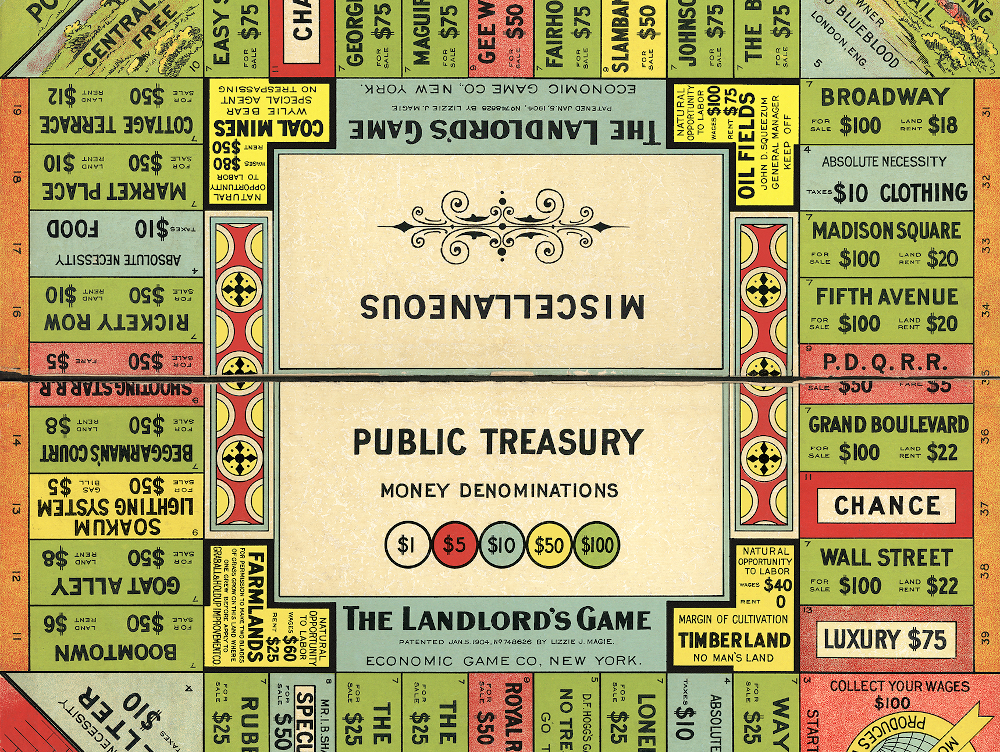

The story of how a homemade, anti-capitalist game created by a woman becomes a mass-produced uber-capitalist game that profited a man.

The story of how a homemade, anti-capitalist game created by a woman becomes a mass-produced uber-capitalist game that profited a man.

I once restored a 1950s timepiece for a customer who waxed lyrical about the intricacies of my work – all the while refusing to pay. They baulked when I presented them with the bill we’d previously agreed. Then they garbled on about the philosophical nature of time, still resisting payment.

It was during that wistful, skyward narrative that I saw the timepiece slip from their hand and hit the marble floor. The mineral glass shattered, sending the hands spiralling. Sunlight streamed in from the winter setting Sun – its sharp, angular rays reminding me of how our ancient ancestors marked the passing of time.

Time was important enough to our ancestors that they went to the effort of building an extraordinary prehistoric monument, Stonehenge. The first part of this enormous solar calendar was built around 2200-2400BC.

But it is far from unique – primeval solar observatories are dotted around the world, including the Chankillo mounds in Peru (built in 200-250BC) and the Australian Aboriginal Wurdi Youang stone arrangement (age unknown). Societies around the world, thousands of miles apart, independently created sites to help mark the passing of time.

As communities developed into cities, empires and states, and societies became more segregated, time became more important and was divided into hours.

The Sumerians (4100-1750BC) based around Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) calculated that the day was approximately 24 hours and that each hour was 60 minutes long. They used the Sun, stars and water clocks to keep track of time. Water clocks used the gradual flow of water from one container to another to measure time.

The ancient Egyptians also introduced a 24-hour time system around 1550-1069BC. But the length of these “hours” varied depending on the time of year – longer in summertime than winter. These measures of time were based on the Sun, with 12 parts during daylight, and another 12 parts through the night. The Egyptians started using a sundial to represent this time system around 1000-800BC. Since sundials cannot tell the time at night, they used water clocks after dark.

In Europe, the development of time measurement gets a bit foggy over the centuries around AD700-1300AD, as all time-telling devices are bundled into the same Latin word, Horologium, in written European records.

The economist and historian David S. Landes claims in his book, Revolution in Time, that monastic Christian prayers were more rigid compared with Judaism and Islam, using the heavens to dictate what time to pray across the Catholic church’s seven set canonical hours. For example, sext was supposed to be recited at midday. The time period between these canonical prayers became equal in length because of the rigidity of prayer times.

Timepieces may also have been more important in central Europe, because the cloudier weather would have made it harder to track the Sun and stars.

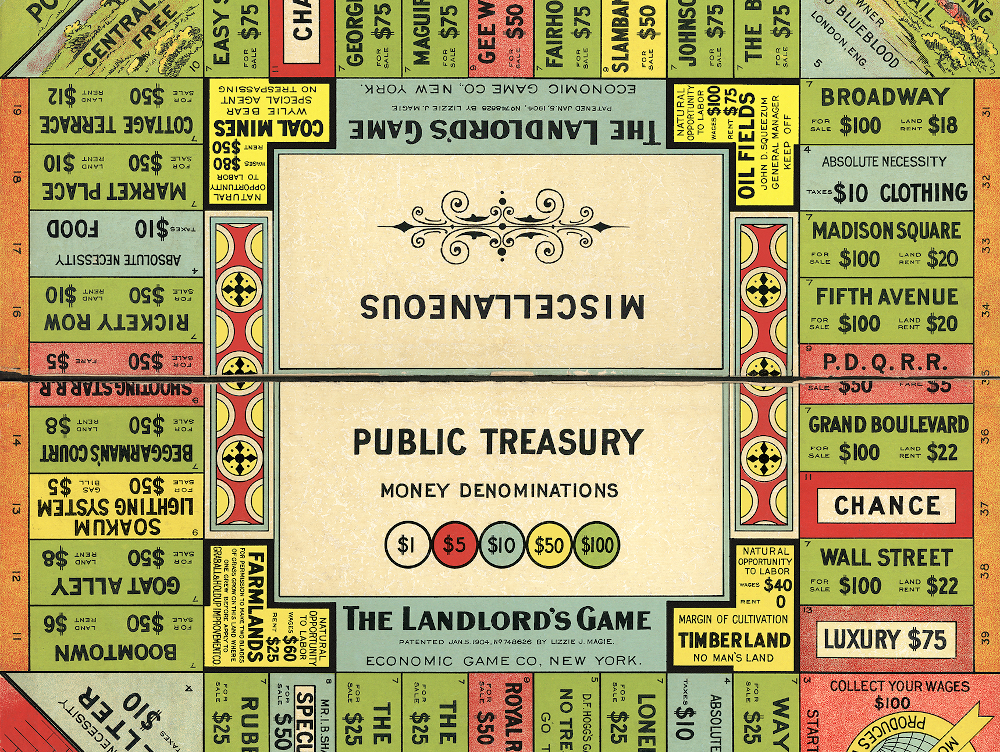

While we can’t be certain from historical records if it was monks who made the first mechanical clocks, we do know that they first appeared in the 14th century.

Their first mention is in the Italian physician, astronomer and mechanical engineer Giovanni de Dondi’s treatise Tractatus Astrarii, or Planetarium. De Dondi states that early clocks used gravity as their power source and were driven by weights.

These weren’t the accurate clocks we see today – they probably kept time to within 15-30 minutes a day. These early clocks started popping up in city centres but, since they did not have a face, they used bells to signal the hours. These signals began to organise the market times and administrative needs of each city.

Coiled springs as a method of releasing energy for clocks began to appear in Europe in the 15th century. This didn’t do anything to improve accuracy, but it could reduce the size of the clock. So, time became more of a personal as well as status object – you only have to look at oil paintings where subject’s watches are proudly displayed.

The Dutch scientist Christian Huygens first applied the pendulum to a clock in about 1656. This bolstered their accuracy to within 15 seconds a day, because each swing now took almost exactly the same time to complete.

As a result, time could be used more accurately in scientific observations, including of the stars. It also meant that clocks could now show an accurate minute hand.

Elsewhere in the world, some time-tracking devices date back many centuries earlier. In the 13th century, there is evidence of the use of gears to control the movement of components in Arabic astrolabes – devices that could calculate time and help navigators determine their position. And long before that, the Ancient Greek Antikythera mechanism, regarded as the world’s first computer, is dated at around 100BC (having been discovered in AD1901). These are both devices that predicted the motions of the planets.

Meanwhile in China, there was Su Song’s astronomical clock – dated to AD1088 – which was powered by water. So, while the clock was invented in Europe in the 14th century, Arabic and Chinese societies were far more technologically advanced at this time than their western Christian counterparts.

Today, wherever we are in the world, time is a unified construct – and the search for ever-more precise measurements continues. In 2021, scientists identified a new shortest timespan, the zeptosecond, which is how long it takes for a particle of light to pass through a molecule of hydrogen.

In modern society, time is usually organised to the minute or even second (think of train timetables, how we document transactions, or record setting in sports). This internalises within ourselves an obsession with being on time. People arrange to meet a friend, and hurry to the destination when they’re a minute or too late. But really, what’s a few minutes between friends?

Jaq Prendergast does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

My annual reminder that January 1st is Public Domain Day, and this year copyright has ended for books, movies, and music first published in the U.S. in 1928, so you are free to use, reprint, quote, remix, and adapt them without permission or payment.

Notable 1928 literary works now in the public domain include Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, A.A. Milne’s The House at Pooh Corner, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, William Butler Yeats’ The Tower, and Robert Frost’s West-Running Brook, to name just a few. The full texts of the 1928 books that have been scanned by the Internet Archive, Hathi Trust, Google Books, and other digital archives should now be publicly available on their websites.

These 1928 works should have gone into the public domain in 1984, after 56 years, but retroactive copyright extensions changed that date first to 2004 and then to 2024, thanks to the 1998 Sony Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, which extended copyright terms of works published before 1978 from 75 to 95 years and works created on or after that date to the life of the author plus 70 years. For many years the public domain in the U.S. was frozen, including only works published through 1922, but since 2019, thousands of works have been released into the public domain each New Year’s Day.

Visit the Public Domain Day 2024 website created by Jennifer Jenkins from Duke Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain to read important news and information about copyright and the public domain and to explore some of the 1928 works that you can now use as you like.

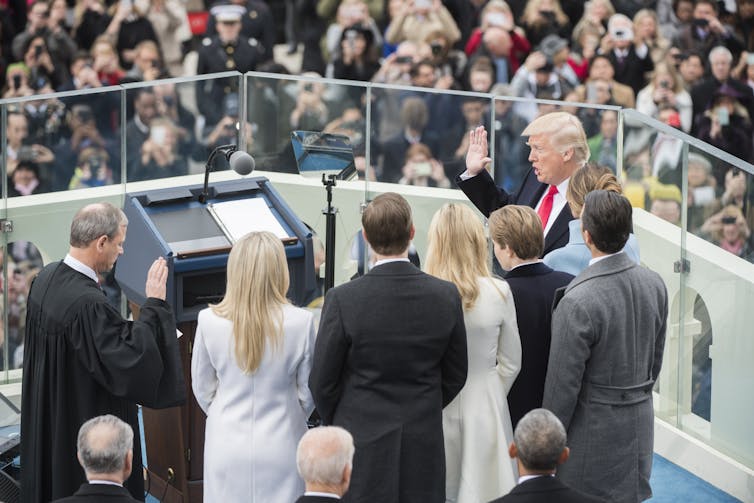

In 2024, former President Donald Trump will face some of his greatest challenges: criminal court cases, primary opponents and constitutional challenges to his eligibility to hold the office of president again. The Colorado Supreme Court has pushed that latter piece to the forefront, ruling on Dec. 19, 2023, that Trump cannot appear on Colorado’s 2024 presidential ballot because of his involvement in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.

The reason is the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868, three years after the Civil War ended. Section 3 of that amendment wrote into the Constitution the principle President Abraham Lincoln set out just three months after the first shots were fired in the Civil War. On July 4, 1861, he spoke to Congress, declaring that “when ballots have fairly, and constitutionally, decided, there can be no successful appeal back to bullets.”

The text of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment states, in full:

“No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.”

To me as a scholar of constitutional law, each sentence and sentence fragment captures the commitment made by the nation in the wake of the Civil War to govern by constitutional politics. People seeking political and constitutional changes must play by the rules set out in the Constitution. In a democracy, people cannot substitute force, violence or intimidation for persuasion, coalition building and voting.

The first words of Section 3 describe various offices that people can only hold if they satisfy the constitutional rules for election or appointment. The Republicans who wrote the amendment repeatedly declared that Section 3 covered all offices established by the Constitution. That included the presidency, a point many participants in framing, ratifying and implementation debates over constitutional disqualification made explicitly, as documented in the records of debate in the 39th Congress, which wrote and passed the amendment.

Senators, representatives and presidential electors are spelled out because some doubt existed when the amendment was debated in 1866 as to whether they were officers of the United States, although they were frequently referred to as such in the course of congressional debates.

No one can hold any of the offices enumerated in Section 3 without the power of the ballot. They can only hold office if they are voted into it – or nominated and confirmed by people who have been voted into office. No office mentioned in the first clause of Section 3 may be achieved by force, violence or intimidation.

The next words in Section 3 describe the oath “to support [the] Constitution” that Article 6 of the Constitution requires all office holders in the United States to take.

The people who wrote Section 3 insisted during congressional debates that anyone who took an oath of office, including the president, were subject to Section 3’s rules. The presidential oath’s wording is slightly different from that of other federal officers, but everyone in the federal government swears to uphold the Constitution before being allowed to take office.

These oaths bind officeholders to follow all the rules in the Constitution. The only legitimate government officers are those who hold their offices under the constitutional rules. Lawmakers must follow the Constitution’s rules for making laws. Officeholders can only recognize laws that were made by following the rules – and they must recognize all such laws as legitimate.

This provision of the amendment ensures that their oaths of office obligate officials to govern by voting rather than violence.

Section 3 then says people can be disqualified from holding office if they “engaged in insurrection or rebellion.” Legal authorities from the American Revolution to the post-Civil War Reconstruction understood an insurrection to have occurred when two or more people resisted a federal law by force or violence for a public, or civic, purpose.

Shay’s Rebellion, the Whiskey Insurrection, Burr’s Rebellion, John Brown’s Raid and other events were insurrections, even when the goal was not overturning the government.

What these events had in common was that people were trying to prevent the enforcement of laws that were consequences of persuasion, coalition building and voting. Or they were trying to create new laws by force, violence and intimidation.

These words in the amendment declare that those who turn to bullets when ballots fail to provide their desired result cannot be trusted as democratic officials. When applied specifically to the events on Jan. 6, 2021, the amendment declares that those who turn to violence when voting goes against them cannot hold office in a democratic nation.

The last sentence of Section 3 announces that forgiveness is possible. It says “Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability” – the ineligibility of individuals or categories of people to hold office because of having participated in an insurrection or rebellion.

For instance, Congress might remove the restriction on office-holding based on evidence that the insurrectionist was genuinely contrite. It did so for repentant former Confederate General James Longstreet .

Or Congress might conclude in retrospect that violence was appropriate, such as against particularly unjust laws. Given their powerful anti-slavery commitments and abolitionist roots, I believe that Republicans in the House and Senate in the late 1850s would almost certainly have allowed people who violently resisted the fugitive slave laws to hold office again. This provision of the amendment says that bullets may substitute for ballots and violence for voting only in very unusual circumstances.

Taken as a whole, the structure of Section 3 leads to the conclusion that Donald Trump is one of those past or present government officials who by violating his oath of allegiance to the constitutional rules has forfeited his right to present and future office.

Trump’s supporters say the president is neither an “officer under the United States” nor an “officer of the United States” as specified in Section 3. Therefore, they say, he is exempt from its provisions.

But in fact, both common sense and history demonstrate that Trump was an officer, an officer of the United States and an officer under the United States for constitutional purposes. Most people, even lawyers and constitutional scholars like me, do not distinguish between those specific phrases in ordinary discourse. The people who framed and ratified Section 3 saw no distinction. Exhaustive research by Trump supporters has yet to produce a single assertion to the contrary that was made in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. Yet scholars John Vlahoplus and Gerard Magliocca are daily producing newspaper and other reports asserting that presidents are covered by Section 3.

Significant numbers of Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate agreed that Donald Trump violated his oath of office immediately before, during and immediately after the events of Jan. 6, 2021. Most Republican senators who voted against his conviction did so on the grounds that they did not have the power to convict a president who was no longer in office. Most of them did not dispute that Trump participated in an insurrection. A judge in Colorado also found that Trump “engaged in insurrection,” which was the basis for the state’s Supreme Court ruling barring him from the ballot.

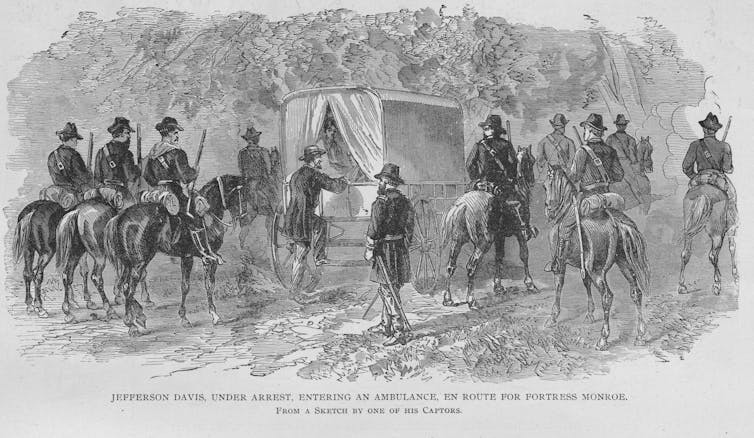

Constitutional democracy is rule by law. Those who have demonstrated their rejection of rule by law may not apply, no matter their popularity. Jefferson Davis participated in an insurrection against the United States in 1861. He was not eligible to become president of the U.S. four years later, or to hold any other state or federal office ever again. If Davis was barred from office, then the conclusion must be that Trump is too – as a man who participated in an insurrection against the United States in 2021.

Mark A. Graber does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Christmas and copyright go together as often gingerbread cookies and milk. Here's just five ways that copyright has changed Christmas.

The post 5 Ways Copyright Has Changed Christmas appeared first on Plagiarism Today.

As the 1906 UK general election results rolled in, it became clear that the Conservative party, after 11 years in power, had suffered one of the most disastrous defeats in its history. Of 402 Conservative MPs, 251 lost their seats, including their candidate for prime minister, defeated on a 22.5% swing against him in the constituency he had held for two decades.

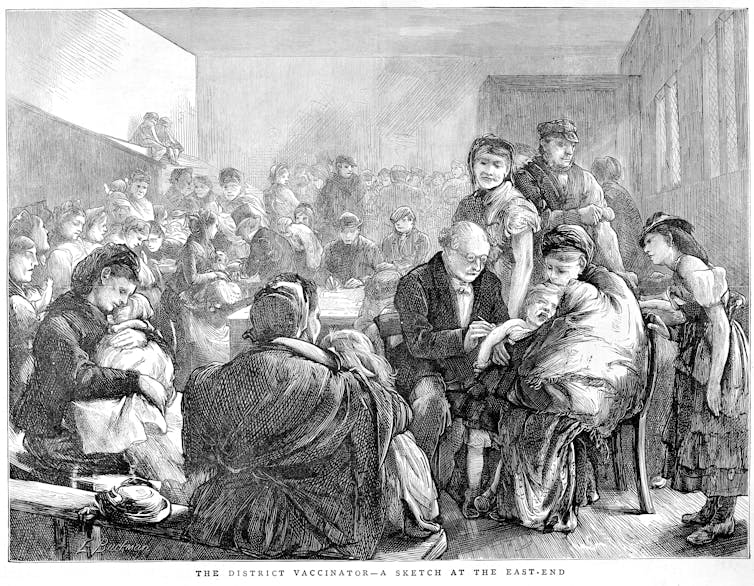

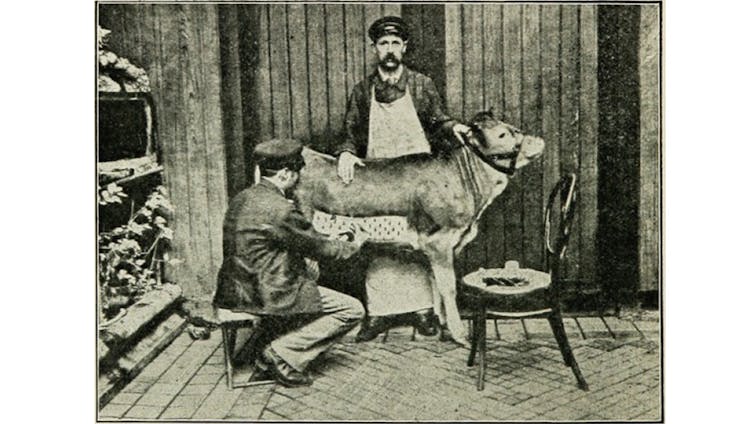

Rising food prices, unpopular taxes and an opposition that promised to spend heavily on an expanded welfare state all contributed to the Tory downfall that year. But something else had tipped the opposition Liberal landslide over the edge – compulsory vaccination.

Anti-vaccination campaigner Arnold Lupton had taken Sleaford in Lincolnshire for the Liberals on a 12% swing and immediately started his parliamentary campaign to abolish compulsory vaccination against smallpox, a public health policy that had been in place in England and Wales since 1853 (with Scottish and Irish legislation following suit in later years).

Hardly a single Conservative MP was an anti-vaccinator, but 174 of the 397 Liberal MPs in the new parliament signed Lupton’s petition.

Their attempt at changing the law was unsuccessful, but this flexing of parliamentary muscle by the anti-vaccinators persuaded the new Liberal government that the most expedient option was to reach a compromise with its backbench rebels.

In 1907, the law was changed to permit quick and easy opt-out by parents. Vaccination of all babies against smallpox remained theoretically compulsory until 1946, but in practice, it was now optional. A five-decade-long campaign, in the streets, the courts and finally parliament, had resulted in victory for the opponents of vaccination.

This is a sobering story for those of us who are researchers, medical professionals or public health activists campaigning against the spread of vaccine hesitancy in the modern world.

The success of vaccination in saving millions of lives, not just from smallpox but a host of other diseases, seems so obvious that the case scarcely needs to be made. And yet it does, as just a cursory glance at social, even at times mainstream, media will reveal.

In response to this tide of dangerous disinformation, vaccine advocacy work often focuses on issues such as the lack of public comprehension of scientific concepts of “relative risk” and “efficacy”, and the connections of the anti-vaccine activists to more general conspiracy theories and extreme religious or political movements.

The conclusion of many vaccine advocacy pieces is often that we must simply educate the public better while simultaneously cutting the flow of disinformation, yet this has often proved to be an uphill struggle. Why? Can vaccine advocates learn anything from the historic defeat of 1906?

A recently published resource of Victorian anti-vaccination “street literature” seeks to contribute to this effort by providing free access to 3.5 million words from 133 documents, ranging from short pamphlets to longer publications over the period 1854-1906.

What the 133 sources have in common is that they were all produced for public consumption, designed to strengthen or maintain the beliefs of the converted while reaching out for new converts. Existing outside the conventional publishing industry, this street literature was the social media of the Victorian era.

Computational analysis of these texts reveals anti-vaccination themes that are very similar to those of today. For instance, doubts about the effectiveness of vaccines, what they’re made of and their safety, feature prominently.

Other common themes include complaints that civil liberties are infringed by compulsory vaccination, alongside conspiracy theories of government cover-ups, general distrust of the medical profession, and an orientation towards alternative medicine.

What changes is the detail. For instance, fear of the inadvertent introduction of syphilis, tuberculosis and skin diseases, as very occasionally happened in Victorian times, may be compared to the blood clots issue with the COVID vaccine.

Other more spurious scare stories, such as an association between vaccination and tooth decay or mental illness have their parallels in the discredited autism claims of the present day. Likewise, modern conspiracy theories about big pharma have their Victorian parallel in allegations of medical profiteering from vaccination fees.

This study of the Victorian anti-vaxxers shows us that there are indeed recurrent fears more than two centuries old. But it also teaches us that some of the motivations of vaccine hesitancy stem from social, political and religious beliefs that are equally deep in time and often deeply held.

For example, William Tebb, one of the most prominent anti-vaxxers of Victorian times campaigned with equal energy on a whole raft of causes, from women’s suffrage to the abolition of slavery via vegetarianism, animal rights and mystical religion.

For Tebb and many of his followers, these were intimately connected causes. To reach the root of the problem, we need to untangle these connections in sensitive ways that go beyond conventional public engagement.

The project described in this article is funded by the UK Economic & Social Research Council.

Chris Sanderson received funding from the UK Economic & Social Research Council for this project.

Alice Deignan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

A recent investigation from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) has revealed an extensive network of YouTube channels promoting pro-Chinese and anti-US public opinion in the English-speaking world.

The operation is well-coordinated, using generative AI to rapidly produce and publish content, while deftly exploiting YouTube’s algorithmic recommendation system.

Operation “Shadow Play” involves a network of at least 30 YouTube channels with about 730,000 subscribers. At the time of writing this article the channels had some 4,500 videos between them, with about 120 million views.

According to ASPI, the channels gained audiences by using AI algorithms to cross-promote each other’s content, thereby boosting visibility. This is concerning as it allows state messaging to cross borders with plausible deniability.

The network of videos also featured an AI avatar created by British artificial intelligence company Synthesia, according to the report, as well as other AI-generated entities and voiceovers.

While it’s not clear who is behind the operation, investigators say the controller is likely Mandarin-speaking. After profiling the behaviour, they concluded it doesn’t match that of any known state actor in the business of online influence operations. Instead, they suggest it might be a commercial entity operating under some degree of state direction.

These findings double as the latest evidence that advanced influence operations are evolving faster than defensive measures.

One clear parallel between the Shadow Play operation and other influence campaigns is the use of coordinated networks of inauthentic social media accounts, and pages amplifying the messaging.

For example, in 2020 Facebook took down a network of more than 300 Facebook accounts, pages and Instagram accounts that were being run from China and posting content about the US election and COVID pandemic. As was the case with Shadow Play, these assets worked together to spread content and make it appear more popular than it was.

The current disclosure requirements around sponsored content have some glaring gaps when it comes to addressing cross-border influence campaigns. Most Australian consumer protection and advertising regulation focuses on commercial sponsorships rather than geopolitical conflicts of interest.

Platforms such as YouTube prohibit deceptive practices in their stated rules. However, identifying and enforcing violations is difficult with foreign state-affiliated accounts that conceal who is pulling their strings.

Determining what is propaganda, as opposed to free speech, raises difficult ethical questions around censorship and political opinions. Ideally, transparency measures shouldn’t unduly restrict protected speech. But viewers still deserve to understand an influencer’s incentives and potential biases.

Possible measures could include clear disclosures when content is affiliated directly or indirectly with a foreign government, as well as making affiliation and location data more visible on channels.

As technologies become more sophisticated, it’s becoming harder to discern what agenda or conflict of interest may be shaping the content of a video.

Discerning viewers can gain some insight by looking into the creator(s) behind the content. Do they provide information on who they are, where they’re based and their background? A lack of clarity may signal an attempt to obscure their identity.

You can also assess the tone and goal of the content. Does it seem to be driven by a specific ideological argument? What is the poster’s ultimate aim: are they just trying to get clicks, or are they persuading you into believing their viewpoint?

Check for credibility signals, such as what other established sources say about this creator or their claims. When something seems dubious, rely on authoritative journalists and fact-checkers.

And make sure not to consume too much content from any single creator. Get your information from reliable sources across the political spectrum so you can take an informed stance.

The advancement of AI could exponentially amplify the reach and precision of coordinated influence operations if ethical safeguards aren’t implemented. At its most extreme, the unrestricted spread of AI propaganda could undermine truth and manipulate real-world events.

Propaganda campaigns may not stop at trying to shape narratives and opinions. They could also be used to generate hyper-realistic text, audio and image content aimed at radicalising individuals. This could greatly destabilise our societies.

We’re already seeing the precursors of what could become AI psy-ops with the ability to spoof identities, surveil citizens en masse, and automate disinformation production.

Without applying an ethics or oversight framework to content moderation and recommendation algorithms, social platforms could effectively act as misinformation mega-amplifiers optimised for watch-time, regardless of the consequences.

Over time, this may erode social cohesion, upend elections, incite violence and even undermine our democratic institutions. And unless we move quickly, the pace of malicious innovation may outstrip any regulatory measures.

It’s more important than ever to establish external oversight to make sure social media platforms work for the greater good, and not just short-term profit.

David Tuffley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Despite the holiday season’s calls for joy and peace, religious strife continues in many places. While the United States has a great deal of litigation and controversy over religion’s place in public life, it has largely avoided violence. Yet our society often seems unprepared to talk constructively about this contentious topic, especially in schools.

According to the IDEALS survey of college students on 122 U.S. campuses, conducted by researchers at North Carolina State University, Ohio State University and the nonprofit Interfaith America, just 32% of students said they had developed the skills “to interact with people of diverse beliefs.” Although almost three-quarters of students spent time learning about people of different races, ethnicities or countries, less than half of them reported learning about various religions. Most students received “C” grades or below on the survey’s religious literacy quiz.

Objective education about the world’s religions has the potential to foster tolerance and understanding, and various research groups provide guidelines for religious literacy education. Yet the study of religion may be hindered by hesitation about what is and isn’t legal in public classrooms – a topic I write about often as a professor of law and education, with a particular interest in these fields’ relationships to religion.

Other countries also face challenges in deciding what kind of religion-related instruction can or can’t be legally taught in public schools, and each deals with the question in different ways.

Though there have been many Supreme Court cases over issues of church and state in public schools, most deal with the First Amendment freedoms of students, staff and parents rather than what’s officially taught in class.

There has been relatively little litigation about what teachers can and can’t instruct students in matters that touch on religion. Two of the exceptions involved lessons about evolution: one decided in 1968, the other in 1987. In both cases, the Supreme Court upheld educators’ right to teach evolution, rather than the biblical accounts of creation, to explain human origins.

Federal trial courts in Mississippi and Florida banned courses in the 1990s that included instruction about the New Testament, ruling that the way they were taught crossed a line and violated the establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution. However, this was because the courts determined instruction was being given from a Christian perspective. The court in Florida did allow teaching about the Hebrew scriptures, because the focus was on the texts’ cultural and literary significance.

In the Supreme Court’s closest response to the question of teaching about religion in public schools, 1963’s School District of Abington Township v. Schempp, eight of the nine justices agreed that state-sponsored prayer and Bible reading in public schools violates the establishment clause. Yet the court recognized that “the Bible is worthy of study for its literary and historic qualities. Nothing we have said here indicates that such study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education, may not be effected consistently with the First Amendment.”

The court’s decision “plainly does not foreclose teaching about the Holy Scriptures or about the differences between religious sects in classes in literature or history,” Justice William Brennan added in a concurrence. Thus, consistent with religious literacy programs’ approach, public schools can teach about religion, but not in ways that seek to instill systems of belief.

To place the issue in perspective, it is worth highlighting other countries’ approaches to teaching about religion in the classroom – the focus of a book I recently edited.

At one end of the 18 countries examined in the book, educators in Mexico impose significant restrictions on what can be taught about faith-based beliefs. According to the Mexican Constitution, “State education shall be maintained entirely apart from any religious doctrine.” However, it does allow religious institutions to provide faith-based education through the private schools they sponsor.

Most nations the book analyzes are more open to teaching about religion in public schools as long as instruction remains objective and does not indoctrinate students. Australia, Brazil, Canada, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, South Africa and Sweden all adopt this approach in varying degrees.

For example, according to the Brazilian Constitution, optional religious education should be offered during the day for elementary students. The country’s National Education Act describes this as a way of “ensuring respect for Brazil’s religious cultural diversity, and any form of proselytism is prohibited.”

Australia allows nondenominational classes about religion to help students understand the “influence of religion in life and society and the variety of beliefs by which people live.” In addition, it permits faith-based student clubs, as well as religious seminars that amount to no more than one half day per term. Parents can ask that their children be excused, or students may participate in ethics courses instead.

At the other end, England, Malaysia and Turkey mandate teaching about religion in public schools, though British parents may exempt their children. England’s Department for Children, Schools and Families strongly encourages that instruction include multiple religious perspectives, while classes in the other two countries are allowed to be more from faith-based perspectives.

Malaysia, which declares Islam the official religion, mandates faith-based instruction on Islam for Muslim students. Non-Muslims must attend moral studies classes. Turkey, meanwhile, requires religious culture and moral knowledge courses for grades 4-12 that focus on Islam. Parents who belong to other religions have the right to exempt their children from these classes.

What happens in public schools in the U.S. today will significantly shape tomorrow’s society. I believe encouraging teaching about religion can help America’s rapidly diversifying population to understand and respect others’ beliefs or lack thereof. Discussing religions in an inclusive, objective and academic way can certainly be challenging in a classroom, as there is a fine line between teaching about it and proselytizing – but not doing so has risks as well.

Charles J. Russo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The global anti-vaccine movement and vaccine hesitancy that accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic show no signs of abating.

According to a survey of U.S. adults, Americans in October 2023 were less likely to view approved vaccines as safe than they were in April 2021. As vaccine confidence falls, health misinformation continues to spread like wildfire on social media and in real life.

I am a public health expert in health misinformation, science communication and health behavior change.

In my view, we cannot underestimate the dangers of health misinformation and the need to understand why it spreads and what we can do about it. Health misinformation is defined as any health-related claim that is false based on current scientific consensus.

Vaccines are the No. 1 topic of misleading health claims. Some common myths about vaccines include:

Their supposed link with human diagnoses of autism. Multiple studies have discredited this claim, and it has been firmly refuted by the World Health Organization, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Concerns with the COVID-19 vaccine leading to infertility. This connection has been debunked through a systematic review and meta-analysis, one of the most robust forms of synthesizing scientific evidence.

Safety concerns about vaccine ingredients, such as thimerosal, aluminum and formaldehyde. Extensive studies have shown these ingredients are safe when used in the minimal amounts contained in vaccines.

Vaccines as medically unnecessary to protect from disease. The development and dissemination of vaccines for life-threatening diseases such as smallpox, polio, measles, mumps, rubella and the flu has saved millions of lives. It also played a critical role in historic increases in average life expectancy – from 47 years in 1900 in the U.S. to 76 years in 2023.

Beliefs in such myths have come at the highest cost.

An estimated 319,000 COVID-19 deaths that occurred between January 2021 and April 2022 in the U.S. could have been prevented if those individuals had been vaccinated, according to a data dashboard from the Brown University School of Public Health. Misinformation and disinformation about COVID-19 vaccines alone have cost the U.S. economy an estimated US$50 million to $300 million per day in direct costs from hospitalizations, long-term illness, lives lost and economic losses from missed work.

Though vaccine myths and misunderstandings tend to dominate conversations about health, there is an abundance of misinformation on social media surrounding diets and eating disorders, smoking or substance use, chronic diseases and medical treatments.

My team’s research and that of others show that social media platforms have become go-to sources for health information, especially among adolescents and young adults. However, many people are not equipped to maneuver the maze of health misinformation.

For example, an analysis of Instagram and TikTok posts from 2022 to 2023 by The Washington Post and the nonprofit news site The Examination found that the food, beverage and dietary supplement industries paid dozens of registered dietitian influencers to post content promoting diet soda, sugar and supplements, reaching millions of viewers. The dietitians’ relationships with the food industry were not always made clear to viewers.

Studies show that health misinformation spread on social media results in fewer people getting vaccinated and can also increase the risk of other health dangers such as disordered eating and unsafe sex practices and sexually transmitted infections. Health misinformation has even bled over into animal health, with a 2023 study finding that 53% of dog owners surveyed in a nationally representative sample report being skeptical of pet vaccines.

One major reason behind the spread of health misinformation is declining trust in science and government. Rising political polarization, coupled with historical medical mistrust among communities that have experienced and continue to experience unequal health care treatment, exacerbates preexisting divides.

The lack of trust is both fueled and reinforced by the way misinformation can spread today. Social media platforms allow people to form information silos with ease; you can curate your networks and your feed by unfollowing or muting contradictory views from your own and liking and sharing content that aligns with your existing beliefs and value systems.

By tailoring content based on past interactions, social media algorithms can unintentionally limit your exposure to diverse perspectives and generate a fragmented and incomplete understanding of information. Even more concerning, a study of misinformation spread on Twitter analyzing data from 2006 to 2017 found that falsehoods were 70% more likely to be shared than the truth and spread “further, faster, deeper and more broadly than the truth” across all categories of information.

The lack of robust and standardized regulation of misinformation content on social media places the difficult task of discerning what is true or false information on individual users. We scientists and research entities can also do better in communicating our science and rebuilding trust, as my colleague and I have previously written. I also provide peer-reviewed recommendations for the important roles that parents/caregivers, policymakers and social media companies can play.

Below are some steps that consumers can take to identify and prevent health misinformation spread:

Check the source. Determine the credibility of the health information by checking if the source is a reputable organization or agency such as the World Health Organization, the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other credible sources include an established medical or scientific institution or a peer-reviewed study in an academic journal. Be cautious of information that comes from unknown or biased sources.

Examine author credentials. Look for qualifications, expertise and relevant professional affiliations for the author or authors presenting the information. Be wary if author information is missing or difficult to verify.

Pay attention to the date. Scientific knowledge by design is meant to evolve as new evidence emerges. Outdated information may not be the most accurate. Look for recent data and updates that contextualize findings within the broader field.

Cross-reference to determine scientific consensus. Cross-reference information across multiple reliable sources. Strong consensus across experts and multiple scientific studies supports the validity of health information. If a health claim on social media contradicts widely accepted scientific consensus and stems from unknown or unreputable sources, it is likely unreliable.

Question sensational claims. Misleading health information often uses sensational language designed to provoke strong emotions to grab attention. Phrases like “miracle cure,” “secret remedy” or “guaranteed results” may signal exaggeration. Be alert for potential conflicts of interest and sponsored content.

Weigh scientific evidence over individual anecdotes. Prioritize information grounded in scientific studies that have undergone rigorous research methods, such as randomized controlled trials, peer review and validation. When done well with representative samples, the scientific process provides a reliable foundation for health recommendations compared to individual anecdotes. Though personal stories can be compelling, they should not be the sole basis for health decisions.

Talk with a health care professional. If health information is confusing or contradictory, seek guidance from trusted health care providers who can offer personalized advice based on their expertise and individual health needs.

When in doubt, don’t share. Sharing health claims without validity or verification contributes to misinformation spread and preventable harm.

All of us can play a part in responsibly consuming and sharing information so that the spread of the truth outpaces the false.

Monica Wang receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Tensions have been running high at many universities around the world since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 and the subsequent Israeli assault on Gaza. In the US, protests and solidarity events have been met with varied responses from university administrations. Some institutions are now facing federal investigation over incidents of alleged antisemitism and Islamophobia.

There’s been political fallout too: in early December, the president of the University of Pennsylvania stood down after coming under pressure following her answers to a hearing in Congress about antisemitism on campus.

In the first of two episodes exploring how the war is affecting life at universities, The Conversation Weekly podcast hears about what’s been happening at one American public college campus.

David Mednicoff says his department at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, tends to have the students who are “the most directly involved in issues around the Middle East, from different perspectives.” Mednicoff is chair of the university’s Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies and an associate professor of Middle Eastern studies and public policy.

Speaking to The Conversation Weekly podcast about the reaction on campus to the Israel-Gaza war, he said he’s been working to find ways of bridging divides, including putting on events designed to provide background to the conflict. Mednicoff believes that students should be able to listen to perspectives that can challenge them, “sometimes even to the core of their identity”.

It is reasonable for a Palestinian Arab to hear an Israeli-Jewish student share their sadness and fear in light of the October 7 massacres. It is reasonable for a pro-Israeli activist to appreciate that there’s a long history and even more important recent history of demeaning of Palestinian rights, particularly in the occupied territories.

Mednicoff says the campus branch of Students for Justice for Palestine has been “louder than pro-Israel folks in terms of campus political discourse”. Pro-Palestinian protests, including a sit-in at a university administrative building where 57 people were arrested, have called for a ceasefire in Gaza. In a separate incident, a student was arrested and charged after allegedly attacking a Jewish student on campus.

Universities have come under fire from those – both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian – who think their leadership should take a stronger stance during the Israel-Gaza conflict. But Mednicoff thinks it isn’t the role of a university to do that. “In general, I think that it is ill advised for universities to take political positions on global issues,” he said. And because of the current climate for higher education, particularly in the US, he thinks it’s also a political choice for universities to try and foster well-informed, open debate.

Universities, I think all over the world, but certainly in the United States are themselves under a good bit of attack, by outside groups who think that universities either should push a particular perspective or they shouldn’t be places where broad free speech is allowed if it goes against what they would conceive as particular guardrails.

You can listen to the full interview with David Mednicoff on The Conversation Weekly, plus an interview with Naomi Schalit, senior editor for politics and democracy at The Conversation in the US.

This episode of The Conversation Weekly was written and produced by Gemma Ware, and Mend Mariwany, with assistance from Katie Flood. Sound design was by Eloise Stevens, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

Newsclips in this episode from NBC News and CBS News.

You can find us on X, formerly known as Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

David Mednicoff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

A recent report noting that funding for Ontario’s universities is “low when compared with support in other provinces” points to underfunding as a serious problem in the province’s post-secondary sector.

Funding quickly raises the question of value: what is it that universities offer that warrants public investment?

Much of my own research has posited that universities have a responsibility to contribute to the public good and to equity.

Academic research and reports authored by educational, not-for-profit and governmental organizations confirm that universities are integral to democratic societies.

The question of the purposes of universities is both long-standing and one that has elicited many perspectives. Recent global attention to both systemic forms of injustice and increasingly urgent climate crises underscore the complexity of considering universities’ obligations to public life.

I contend that the central contribution of post-secondary institutions, related to graduate and undergraduate education, is to prepare students to attend to the practices of living together well — with the capacities to recognize inequity and advance equity, in field-specific settings and a range of communities.

While many faculty members might agree with the idea that a university education will ideally respond to professional, intellectual and public and equity-related priorities, the conversation can quickly become contested.

Indeed, implementation of this idea does present challenges. And yet — graduates will enter a world in which systemic forms of inequity are present in a variety of settings and sectors. The likelihood of a university graduate encountering inequity in their chosen profession or field is less a question of if than when and how.

Likewise, the view that universities can educate students who can contribute to a more equitable future offers a constructive and bold response to the question of what a university education is for.

Universities can and do prepare graduates to contribute to their professions, to economic interests, and to the public good. The economic, civic and intellectual ends of a university education do not need to be placed in opposition to one another, or set up as binary or discreet.

Increasingly, universities and accreditation bodies alike are affirming the multiple and overlapping interests a university degree supports, including the importance of curricular attention to diversity and equity.

One obvious concrete end of a university education is the intellectual endeavour, which typically includes the acquisition of knowledge and the life of the mind.

Civic ends constitute a second purpose of a university education: ideally, students will be able to consider how a degree prepares them to think and act as citizens and participate in key public decisions.

Read more: Canadian engineers call for change to their private 'iron ring' ceremony steeped in colonialism

Those in industry, provincial and federal governments, and the post-secondary sector stress the importance of preparing students for the labour market and for employment.

Studies have demonstrated that students, whether in professional disciplines (such as nursing or engineering) or those not governed by accreditation bodies (like philosophy or film) will make significant economic and civic contributions, whether in the public sector or other industries.

Directly asserting that universities have an obligation to contribute to the practices of living together well with an eye toward equity can quickly raise objections from within and outside of higher education.

There are many who are most comfortable with the belief that universities are neutral institutions and that academic programs ought to maintain this neutrality via a clear and often specific reliance on rational, discipline-specific thought or methods. In fact, in providing content in academic programs and specific courses, faculty members endorse a way of seeing the world.

Faculty members teach in ways that, implicitly or explicitly and intentionally or not, variously endorse the status quo and existing forms of injustice, or call attention to the need for equity and provide an education that speaks to this need.

Read more: In times of racial injustice, university education should not be 'neutral'

Time in the classroom and in conversation with faculty members and other students will shape habits, inform priorities and orient students toward what is possible and desirable.

Graduates’ choices and actions will nearly always have a bearing on how people live. Whether in sociology or biology or mathematics, courses will orient students in how to understand the world in which they live, and also in regard to what their responsibilities are to that world in the context of their chosen fields.

We can do so in ways that underscore the hallmarks of intellectual engagement: curiosity, openness to various perspectives, attention to context, and listening to those with whom we disagree.

Universities are places for deliberation, inquiry, curiosity and investigation. In teaching students, university faculty have the privilege of asking why, how and what for in regard to numerous settings and situations, and the pleasure of bringing knowledge and different perspectives to bear on how classroom learning affects our society.

We live in a world in which systemic forms of inequity persist. In designing courses and academic programs, faculty have an opportunity to engage students with field-specific knowledge and to attend to the practical and ethical uses of that knowledge once students graduate.

For all these reasons, a university education at its best will be attentive to the public good and to equity, and to civic, intellectual and employment ends.

Jennifer S Simpson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

As the war between Israel and Hamas drags on, many on both sides have taken to social media to gather information and air their outrage. The impulse to do so is understandable: Political activism on social media provides people with an emotional outlet and gives them a sense that they can do something. The war is awful, and following it generates a sharp psychological need to get involved and do something.

In the past few years, my colleagues and I at UMass Boston’s Applied Ethics Center have been studying the ethics of emerging technologies. I believe that political activism on social media is a counterproductive and sometimes even dangerous form of engagement. Here’s why.

Social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, YouTube and TikTok are designed to maximize engagement. Their algorithms are tweaked to make sure that users spend a lot of time on them. The best ways to drive engagement are to either show people what they will likely agree with or to show them content that will outrage and shock them.

As a result, the content you will most frequently encounter on social media will either mirror your own views or upset you, or both. In other words, political engagement on social media most often generates no new knowledge while it inflames already raw emotions. When it comes to a conflict as historically convoluted and as emotionally charged as the Israel-Hamas war, those are terrible outcomes.

Then there is the well-known problem of disinformation.

Individuals as well as government agents have been posting false and misleading material to social media at a breathtaking rate since the beginning of the war. Russia, Iran and China have been running disinformation efforts meant to undercut Israel and bolster the image of Hamas. Russia and Iran have, for instance, circulated false information alleging that Israel bombed the Al Ahli hospital in Gaza and that the U.S. supplied the bomb used to destroy it, though most credible news sources agree that it was a misfired rocket from Gaza that hit the site.

Russia, Iran and China are using the war in Gaza to fight their proxy war with the U.S. As a result, the average social media user will be exposed to a great deal of content meant to promote the interests of those countries. Stated differently, you might go to social media for information about the conflict, but what you often end up with is propaganda.

Social media is also notoriously bad at mediating complexity. The realities surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are profoundly intricate – politically, historically and morally.

And yet, the very nature of social media platforms, with their space limitations and their calibration toward likes, shares and virality, is antithetical to conveying such complexity. For example, many social media posts describe Israel as a “settler colonial” entity. The state is characterized as a colonial enterprise that imposed itself forcefully on an indigenous Palestinian population. But the reality is more nuanced.

Israel was founded as a result of a United Nations partition decision, not as a colonial settlement, and Jews are as indigenous to the region as Palestinians. Yet, Israel does have colonies, considered illegal by many experts on international law, which were created after the 1967 Middle East war. The Israelis are not settlers or colonialists, but they do have colonies and settlers live in those colonies in the West Bank.

How can that complexity be conveyed on social media?

Take another example: Israel’s current government is the most far right it has ever had, and some members of that government have openly espoused Jewish supremacist views. And yet, Hamas’ attack on Oct. 7, 2023, had nothing to do with the identity of Israel’s government or with the fact that Israel occupies the West Bank. The organization rejects Israel’s right to exist under any government.

How can that duality be conveyed on TikTok? And who would have the patience to take it in?

It is the capacity to hold such complicated, uncomfortable realities together, in one thought, that can promote understanding about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But social media is designed to convey short, snappy, stark messages that are easy to grasp and repeat. Rather than helping people think about historical and moral ambiguity, social media usually promotes a cartoonish version of reality.

Rather than depth, so crucial for any insight about this terrible war, one gets the rule of anecdotes: A video clip of a Palestinian woman telling an Al Jazeera reporter that Hamas confiscates humanitarian aid is often shared as purported evidence that popular resentment against the group is growing. Maybe such sentiments are mounting, maybe not.

Obviously, there’s no reliable polling going on in Gaza now. And yet, social media users have presented the clip as an important piece of evidence.

Perhaps most strikingly, the very existence of social media serves as an impetus to create and share inflammatory content. This is one of the lessons that the Islamic State group taught the world with its made-for-YouTube brand of terrorism. That lesson was not lost on Hamas: On Oct. 7, some members of its Nukhba force – the commandos who led the assault – livestreamed their barbaric, murderous rampage in southern Israel with GoPro cameras.

The acts themselves were designed for social media consumption. The point was to shock and scare viewers. In the case of social media, the medium really is the message, to use Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase. That means that the prospects of posting to Telegram or X influence the kind of content that will be created in the first place.

All of this suggests two straightforward recommendations for anyone who wants to stay informed and politically engaged about this war: Don’t get your news from social media, and don’t focus your activism on social media.

These platforms are designed to make money for the companies that developed them and not to inform you or promote meaningful activism. Knowledge comes from consuming a variety of credible, vetted news sources. Meaningful political engagement happens between real people in the real world and is based on real information.

Social media can be used to point people to credible news sources and to organize real political activities. But most of the time it is not. Junk food harms your body; junk information and junk engagement harm the body politic. The most momentous political events of our lifetime deserve a greater degree of intellectual and political commitment than that.

The Applied Ethics Center at UMass Boston receives funding from the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies. Nir Eisikovits serves as the data ethics advisor to Hour25AI, a startup dedicated to reducing digital distractions.

The U.S. is in the midst of a racial reckoning. The COVID-19 pandemic, which took a particularly heavy toll on Black communities, turned a harsh spotlight on long-standing health disparities that the public could no longer overlook.

Although the health disparities for Black communities have been well known to researchers for decades, the pandemic put real names and faces to these numbers. Compared with white people, Black people are at much greater risk for developing a range of health problems, including heart disease, diabetes and dementia. For example, Black people are twice as likely as white people to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

A vast and growing body of research shows that racism contributes to systems that promote health inequities. Most recently, our team has also learned that racism directly contributes to these inequities on a neurobiological level.

We are clinical neuroscientists who study the multifaceted ways in which racism affects how our brains develop and function. We use brain imaging to study how trauma such as sexual assault or racial discrimination can cause stress that leads to mental health disorders like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

We have studied trauma in the context of a study known as the Grady Trauma Project, which has been running for nearly 20 years. This study is largely focused on the trauma and stress of Black people in the metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, community.

Racial discrimination is commonly experienced through subtle indignities: a woman clutching her purse as a Black man walks by on the sidewalk, a shopkeeper keeping close watch on a Black woman shopping in a clothing store, a comment about a Black employee being a “diversity hire.” These slights are often referred to as microaggressions.

Decades of research has shown that the everyday burden of these race-related threats, slights and exclusions in day-to-day life translates into a real increase in disease risk. But researchers are only beginning to understand how these forms of discrimination affect a person’s biology and overall health.

Our team’s research shows that the everyday burden of racism affects the function and structure of the brain. In turn, these changes play a major role in risk for health problems.

For instance, our studies show that racial discrimination increases the activity of brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex, that are involved in regulating emotions.

This increased activity in prefrontal brain regions occurs because responding to these types of affronts requires high-effort coping strategies, such as suppressing emotions. People who have experienced more racial discrimination also show more activation in brain regions that enable them to inhibit and suppress anger, shock or sadness so that they can curate a socially acceptable response.

Despite the fact that high-energy coping allows people to manage a constant barrage of threats, this comes at a cost.

The more brain energy you use to suppress, control or manage your feelings, the more energy you take away from the rest of the body. Over time, and without prolonged periods of rest, relief and restoration, this can contribute to other problems, a process that public health researcher Arline Geronimus termed “weathering.” Having these brain regions in continual overdrive is linked with accelerated biological aging, which can create vulnerability for health problems and early death.

In our research, we have found that this weathering process is evident in the gradual degradation of brain structure, particularly in the heavily myelinated axons of the brain, known as “white matter,” which serve as the brain’s information highways.

Myelin is a protective sheath around nerve fibers that allows for improved communication between brain cells. Similar to highways for vehicles, without sufficient maintenance of the myelin, degradation will occur.

Erosion in these brain pathways can affect self-regulation, making a person more vulnerable to developing unhealthy coping strategies for stress, such as emotional eating or substance use. These behaviors, in turn, can increase one’s risk for a wide variety of health problems.

These racism-related changes in the brain, and their direct effects on coping, may help to explain why Black people are twice as likely to develop brain health problems such as Alzheimer’s disease compared with white people.

In our view, what makes racism particularly insidious and pernicious to the health of Black people is the societal invalidation that accompanies it. This makes racial trauma effectively invisible. Racism, whether it originates from people or from institutional systems, is often rationalized, excused or dismissed.

Such invalidation leads those who experience racism to second-guess themselves: “Am I just being too sensitive?” People who have the temerity to report racist events are often ridiculed or met with skepticism. This extends to academic spheres as well.

This continual questioning and doubting of the circumstances around racist experiences, or racial gaslighting, may be part of what depletes the brain of its resources, causing the weathering that ultimately increases vulnerability to brain health problems.

Interrupting this cycle requires that people learn to identify their biases toward people of color and people in marginalized groups more generally, and to understand how those biases may lead to discriminatory words and behavior. We believe that by finding their blind spots, people can see ways in which their actions and behaviors could be viewed as hurtful, exclusionary or offensive. Through recognition of these experiences as racist, people can become allies rather than skeptics.

Institutions can help to create a culture of healing, validation and support for people of color. A validating, supportive institutional culture may help people of color normalize their reactions to these stressors, in addition to the connection – and restoration – they may find within their communities.

Negar Fani receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and Emory University School of Medicine.

Nathaniel Harnett receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College.

WASHINGTON D.C.—The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and five organizations defending free speech today urged the Supreme Court to strike down laws in Florida and Texas that let the states dictate certain speech social media sites must carry, violating the sites’ First Amendment rights to curate content they publish—a protection that benefits users by creating speech forums accommodating their diverse interests, viewpoints, and beliefs.

The court’s decisions about the constitutionality of the Florida and Texas laws—the first laws to inject government mandates into social media content moderation—will have a profound impact on the future of free speech. At stake is whether Americans’ speech on social media must adhere to government rules or be free of government interference.

Social media content moderation is highly problematic, and users are rightly often frustrated by the process and concerned about private censorship. But retaliatory laws allowing the government to interject itself into the process, in any form, raises serious First Amendment, and broader human rights, concerns, said EFF in a brief filed with the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Woodhull Freedom Foundation, Authors Alliance, Fight for The Future, and First Amendment Coalition.

“Users are far better off when publishers make editorial decisions free from government mandates,” said EFF Civil Liberties Director David Greene. “These laws would force social media sites to publish user posts that are at best, irrelevant, and, at worst, false, abusive, or harassing.

“The Supreme Court needs to send a strong message that the government can’t force online publishers to give their favored speech special treatment,” said Greene.

Social media sites should do a better job at being transparent about content moderation and self-regulate by adhering to the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation. But the Principles are not a template for government mandates.

The Texas law broadly mandates that online publishers can’t decline to publish others’ speech based on anyone’s viewpoint expressed on or off the platform, even when that speech violates the sites' rules. Content moderation practices that can be construed as viewpoint-based, which is virtually all of them, are barred by the law. Under it, sites that bar racist material, knowing their users object to it, would be forced to carry it. Sites catering to conservatives couldn’t block posts pushing liberal agendas.

The Florida law requires that social media sites grant special treatment to electoral candidates and “journalistic enterprises” and not apply their regular editorial practices to them, even if they violate the platforms' rules. The law gives preferential treatment to political candidates, preventing publishers at any point before an election from canceling their accounts or downgrading their posts or posts about them, giving them free rein to spread misinformation or post about content outside the site’s subject matter focus. Users not running for office, meanwhile, enjoy no similar privilege.

What’s more, the Florida law requires sites to disable algorithms with respect to political candidates, so their posts appear chronologically in users’ feeds, even if a user prefers a curated feed. And, in addition to dictating what speech social media sites must publish, the laws also place limits on sites' ability to amplify content, use algorithmic ranking, and add commentary to posts.

“The First Amendment generally prohibits government restrictions on speech based on content and viewpoint and protects private publisher ability to select what they want to say,” said Greene. “The Supreme Court should not grant states the power to force their preferred speech on users who would choose not to see it.”

“As a coalition that represents creators, readers, and audiences who rely on a diverse, vibrant, and free social media ecosystem for art, expression, and knowledge, the National Coalition Against Censorship hopes the Court will reaffirm that government control of media platforms is inherently at odds with an open internet, free expression, and the First Amendment,” said Lee Rowland, Executive Director of National Coalition Against Censorship.

“Woodhull is proud to lend its voice in support of online freedom and against government censorship of social media platforms,” said Ricci Joy Levy, President and CEO at Woodhull Freedom Foundation. “We understand the important freedoms that are at stake in this case and implore the Court to make the correct ruling, consistent with First Amendment jurisprudence.”

"Just as the press has the First Amendment right to exercise editorial discretion, social media platforms have the right to curate or moderate content as they choose. The government has no business telling private entities what speech they may or may not host or on what terms," said David Loy, Legal Director of the First Amendment Coalition.

For the brief:

https://www.eff.org/document/eff-brief-moodyvnetchoice

As the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) prepares to release its drinking water regulations on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “Forever Chemicals,” the Tampa Water Department is exploring a pioneering approach that will put it well ahead of the curve.

Suspended Ion Exchange, or “SIX,” will help address Tampa’s water quality needs. This sill also position the Water Department to meet the EPA’s future drinking water regulations. The Tampa Water Department is working to adopt this state-of-the-art technology at the David L. Tippin Water Treatment Facility. Once complete, this will become the first SIX facility in America and the largest in the world.

PFAS are man-made chemicals that are widely used and break down slowly over time. Researchers are trying to determine the impact of long-term PFAS exposure. However, scientific studies show that PFAS may be linked to negative health effects in humans. The EPA is expected to release its finalized regulations on six PFAS chemicals by the start of 2024. The proposed limits, which have yet to become official, are 4 parts per trillion. To put that into perspective, one part per trillion is equivalent to a drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Related: Tampa Bay Business Accelerator Focuses on Climate Technology

The David L. Tippin Water Treatment Facility monitors PFAS levels in its finished water as part of the EPA’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule requirements. Testing completed over the last year showed some PFAS variants were detected in the samples, with the levels of two PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, detected slightly above the proposed limits in some samples.

Currently more than 33% of Florida’s water treatment facilities exceed the proposed limits.

There are a limited number of technologies capable of minimizing PFAS levels in drinking water. While many utilities are still trying to determine how they might address the upcoming regulations, the Tampa Water Department already has a framework in development, and SIX is an essential piece of that solution.

“The City of Tampa and the Tampa Water Department are committed to providing our residents with clean, safe drinking water,” said Mayor Jane Castor. “There are a limited number of technologies capable of minimizing PFAS levels in drinking water, making this technology a critical investment to improve the quality of our water for generations to come.”

The Tampa Water Department initially piloted this technology in 2020. The pilot program showed that SIX will provide additional benefits, including:

The results of the pilot were so promising that the SIX pilot is now being tested at the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The post New Technology Will Help Clean Tampa Water appeared first on ModernGlobe.

Many observers have referred to the massacre of Israelis by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023, as the deadliest attack against the Jewish people in a single day “since the Holocaust.”

As scholars who have spent decades studying the history of Israel’s relationship with the Holocaust, we have argued that the Holocaust should remain unique and not be compared with other atrocities. We have written against simplistic Holocaust analogies, like comparing mask and vaccine mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic to the Nazi persecution of the Jews, or the practice of labeling political opponents “Nazis.” Both seem to trivialize the memory of what is known as the Shoah, the Hebrew word for “catastrophe.”

But the Oct. 7 massacres perpetrated by Hamas changed our thinking.

Over the past 75 years, the collective memory of the Shoah has assumed a central place in Israeli national identity. The memory of the Holocaust has increasingly become the prism through which Israelis understand both their past and their present relationships with the Arab and Muslim world.

Israelis saw the Holocaust’s threat of annihilation echoed in many situations. In 1967, there was the waiting period before the Six-Day War, when the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser threatened to “wipe Israel off the map.” It was there in the trauma of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the unexpected, simultaneous attacks by Egypt and Syria. When Israel destroyed the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981, Prime Minister Menachem Begin justified it with the explanation that “there won’t be another Holocaust in history.”

This association has only strengthened in the past 40 years with the 1982 Lebanon war, two Palestinian uprisings, known as intifadas, and with the present threat posed by a nuclear Iran.

All these events evoke the memory of the Holocaust and are understood within the collective memory of threats of annihilation. This phenomenon represents, for many Israelis, an inability to separate their current situation from the vulnerability of the diaspora Jewish past. And this conflation of past and present continues to play a central role in Israeli politics, foreign policy and public discourse.

The frequent comparisons between the Oct. 7 massacres and the Shoah are more, we believe, than just the default associations of a people submerged in Holocaust postmemory, which refers to inherited and imagined memories of subsequent generations who did not personally experience the trauma. In seeking to describe the depths of evil they witnessed on Oct. 7, Israelis were making more than just an emotional connection between the Holocaust and the Oct. 7 massacres.

To help explain the logic of that connection, specific and reasonable comparisons can be made to better understand Hamas’ traumatic and devastating massacre of Israelis. Below are a few of the many parallels:

Just as the Nazis aimed to annihilate the Jews, Hamas and affiliated terrorist organizations share the same objective: the destruction of Jews. The 1988 Hamas charter refers to “Jews” and not “Israelis” when calling for the destruction of these people.

While the 2017 Hamas covenant states that Hamas does not seek war with the Jews, but instead “wages a struggle against the Zionists who occupy Palestine,” the slaughter of Jews – many of whom were peace activists – in October has proven otherwise.

The national struggle of Hamas is predicated upon the conquest of land and elimination of the Jews. Hamas officials have subsequently promised to repeat Oct. 7 again and again until Israel is annihilated.

While the racial antisemitism of the Nazi regime differs from the antisemitism employed in the fundamentalist Islamic version of Hamas, antisemitism is a key part of the struggle for both ideologies. Indoctrination from an early age aimed at the dehumanization of the Jews is a key part of both how Nazis taught young German students during the Third Reich and in how Hamas educates children in Gaza.