Forests are an essential part of Earth’s operating system. They reduce the buildup of heat-trapping carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from fossil fuel combustion, deforestation and land degradation by 30% each year. This slows global temperature increases and the resulting changes to the climate. In the U.S., forests take up 12% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions annually and store the carbon long term in trees and soils.

Mature and old-growth forests, with larger trees than younger forests, play an outsized role in accumulating carbon and keeping it out of the atmosphere. These forests are especially resistant to wildfires and other natural disturbances as the climate warms.

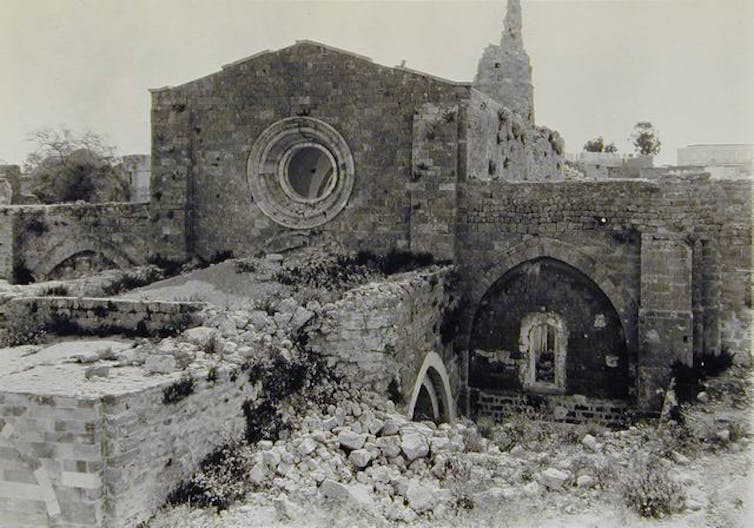

Most forests in the continental U.S. have been harvested multiple times. Today, just 3.9% of timberlands across the U.S., in public and private hands, are over 100 years old, and most of these areas hold relatively little carbon compared with their potential.

The Biden administration is moving to improve protection for old-growth and mature forests on federal land, which we see as a welcome step. But this involves regulatory changes that will likely take several years to complete. Meanwhile, existing forest management plans that allow logging of these important old, large trees remain in place.

As scientists who have spent decades studying forest ecosystems and the effects of climate change, we believe that it is essential to start protecting carbon storage in these forests. In our view, there is ample scientific evidence to justify an immediate moratorium on logging mature and old-growth forests on federal lands.

Federal action to protect mature and old-growth forests

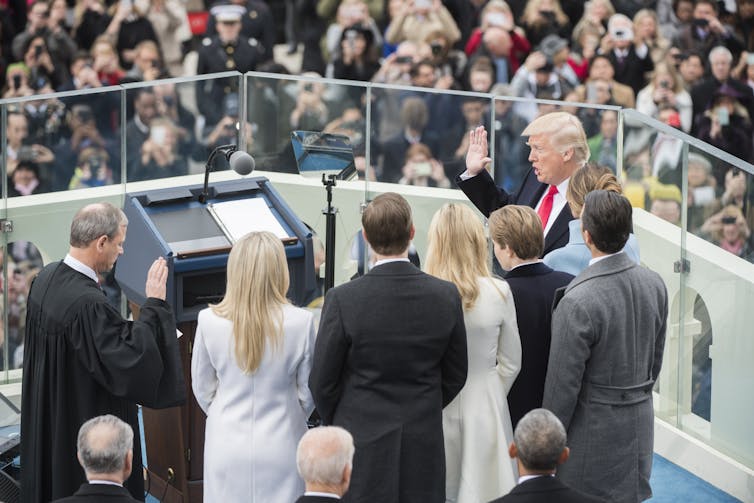

A week after his inauguration in 2021, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that set a goal of conserving at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030 to address what the order called “a profound climate crisis.” In 2022, Biden recognized the climate importance of mature and old-growth forests for a healthy climate and called for conserving them on federal lands.

Most recently, in December 2023, the U.S. Forest Service announced that it was evaluating the effects of amending management plans for 128 U.S. national forests to better protect mature and old-growth stands – the first time any administration has taken this kind of action.

These actions seek to make existing old-growth forests more resilient; preserve ecological benefits that they provide, such as habitat for threatened and endangered species; establish new areas where old-growth conditions can develop; and monitor the forests’ condition over time. The amended national forest management plans also would prohibit logging old-growth trees for mainly economic purposes – that is, producing timber. Harvesting trees would be permitted for other reasons, such as thinning to reduce fire severity in hot, dry regions where fires occur more frequently.

Remarkably, however, logging is hardly considered in the Forest Service’s initial analysis, although studies show that it causes greater carbon losses than wildfires and pest infestations.

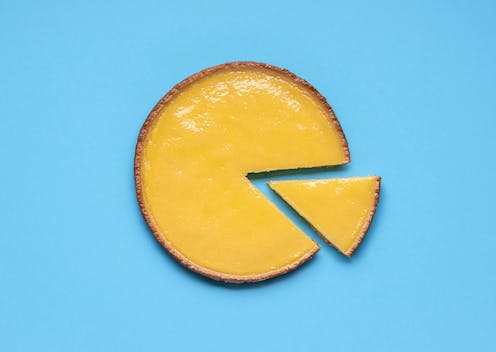

In one analysis across 11 western U.S. states, researchers calculated total aboveground tree carbon loss from logging, beetle infestations and fire between 2003 and 2012 and found that logging accounted for half of it. Across the states of California, Oregon and Washington, harvest-related carbon emissions between 2001 and 2016 averaged five times the emissions from wildfires.

A 2016 study found that nationwide, between 2006 and 2010, total carbon emissions from logging were comparable to emissions from all U.S. coal plants, or to direct emissions from the entire building sector.

Logging pressure

Federal lands are used for multiple purposes, including biodiversity and water quality protection, recreation, mining, grazing and timber production. Sometimes, these uses can conflict with one another – for example, conservation and logging..

Legal mandates to manage land for multiple uses do not explicitly consider climate change, and federal agencies have not consistently factored climate change science into their plans. Early in 2023, however, the White House Council on Environmental Quality directed federal agencies to consider the effects of climate change when they propose major federal actions that significantly affect the environment.

Multiple large logging projects on public land clearly qualify as major federal actions, but many thousands of acres have been legally exempted from such analysis.

Across the western U.S., just 20% of relatively high-carbon forests, mostly on federal lands, are protected from logging and mining. A study in the lower 48 states found that 76% of mature and old-growth forests on federal lands are vulnerable to logging. Harvesting these forests would release about half of their aboveground tree carbon into the atmosphere within one or two decades.

An analysis of 152 national forests across North America found that five forests in the Pacific Northwest had the highest carbon densities, but just 10% to 20% of these lands were protected at the highest levels. The majority of national forest area that is mature and old growth is not protected from logging, and current management plans include logging of some of the largest trees still standing.

Letting old trees grow

Conserving forests is one of the most effective and lowest-cost options for managing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and mature and old-growth forests do this job most effectively. Protecting and expanding them does not require expensive or complex energy-consuming technologies, unlike some other proposed climate solutions.

Allowing mature and old-growth forests to continue growing will remove from the air and store the largest amount of atmospheric carbon in the critical decades ahead. The sooner logging of these forests ceases, the more climate protection they can provide.

Richard Birdsey, a former U.S. Forest Service carbon and climate scientist and current senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, contributed to this article.

This is an update of an article originally published on March 2, 2023.

Beverly Law receives funding from the Conservation Biology Institute.

William Moomaw receives funding from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.