The following is the prepared version of a talk that I gave at SPARC: a high-school summer program about applied rationality held in Berkeley, CA for the past two weeks. I had a wonderful time in Berkeley, meeting new friends and old, but I’m now leaving to visit the CQT in Singapore, and then to attend the AQIS conference in Seoul.

Common Knowledge and Aumann’s Agreement Theorem

August 14, 2015

Thank you so much for inviting me here! I honestly don’t know whether it’s possible to teach applied rationality, the way this camp is trying to do. What I know is that, if it is possible, then the people running SPARC are some of the awesomest people on earth to figure out how. I’m incredibly proud that Chelsea Voss and Paul Christiano are both former students of mine, and I’m amazed by the program they and the others have put together here. I hope you’re all having fun—or maximizing your utility functions, or whatever.

My research is mostly about quantum computing, and more broadly, computation and physics. But I was asked to talk about something you can actually use in your lives, so I want to tell a different story, involving common knowledge.

I’ll start with the “Muddy Children Puzzle,” which is one of the greatest logic puzzles ever invented. How many of you have seen this one?

OK, so the way it goes is, there are a hundred children playing in the mud. Naturally, they all have muddy foreheads. At some point their teacher comes along and says to them, as they all sit around in a circle: “stand up if you know your forehead is muddy.” No one stands up. For how could they know? Each kid can see all the other 99 kids’ foreheads, so knows that they’re muddy, but can’t see his or her own forehead. (We’ll assume that there are no mirrors or camera phones nearby, and also that this is mud that you don’t feel when it’s on your forehead.)

So the teacher tries again. “Knowing that no one stood up the last time, now stand up if you know your forehead is muddy.” Still no one stands up. Why would they? No matter how many times the teacher repeats the request, still no one stands up.

Then the teacher tries something new. “Look, I hereby announce that at least one of you has a muddy forehead.” After that announcement, the teacher again says, “stand up if you know your forehead is muddy”—and again no one stands up. And again and again; it continues 99 times. But then the hundredth time, all the children suddenly stand up.

(There’s a variant of the puzzle involving blue-eyed islanders who all suddenly commit suicide on the hundredth day, when they all learn that their eyes are blue—but as a blue-eyed person myself, that’s always struck me as needlessly macabre.)

What’s going on here? Somehow, the teacher’s announcing to the children that at least one of them had a muddy forehead set something dramatic in motion, which would eventually make them all stand up—but how could that announcement possibly have made any difference? After all, each child already knew that at least 99 children had muddy foreheads!

Like with many puzzles, the way to get intuition is to change the numbers. So suppose there were two children with muddy foreheads, and the teacher announced to them that at least one had a muddy forehead, and then asked both of them whether their own forehead was muddy. Neither would know. But each child could reason as follows: “if my forehead weren’t muddy, then the other child would’ve seen that, and would also have known that at least one of us has a muddy forehead. Therefore she would’ve known, when asked, that her own forehead was muddy. Since she didn’t know, that means my forehead is muddy.” So then both children know their foreheads are muddy, when the teacher asks a second time.

Now, this argument can be generalized to any (finite) number of children. The crucial concept here is common knowledge. We call a fact “common knowledge” if, not only does everyone know it, but everyone knows everyone knows it, and everyone knows everyone knows everyone knows it, and so on. It’s true that in the beginning, each child knew that all the other children had muddy foreheads, but it wasn’t common knowledge that even one of them had a muddy forehead. For example, if your forehead and mine are both muddy, then I know that at least one of us has a muddy forehead, and you know that too, but you don’t know that I know it (for what if your forehead were clean?), and I don’t know that you know it (for what if my forehead were clean?).

What the teacher’s announcement did, was to make it common knowledge that at least one child has a muddy forehead (since not only did everyone hear the announcement, but everyone witnessed everyone else hearing it, etc.). And once you understand that point, it’s easy to argue by induction: after the teacher asks and no child stands up (and everyone sees that no one stood up), it becomes common knowledge that at least two children have muddy foreheads (since if only one child had had a muddy forehead, that child would’ve known it and stood up). Next it becomes common knowledge that at least three children have muddy foreheads, and so on, until after a hundred rounds it’s common knowledge that everyone’s forehead is muddy, so everyone stands up.

The moral is that the mere act of saying something publicly can change the world—even if everything you said was already obvious to every last one of your listeners. For it’s possible that, until your announcement, not everyone knew that everyone knew the thing, or knew everyone knew everyone knew it, etc., and that could have prevented them from acting.

This idea turns out to have huge real-life consequences, to situations way beyond children with muddy foreheads. I mean, it also applies to children with dots on their foreheads, or “kick me” signs on their backs…

But seriously, let me give you an example I stole from Steven Pinker, from his wonderful book The Stuff of Thought. Two people of indeterminate gender—let’s not make any assumptions here—go on a date. Afterward, one of them says to the other: “Would you like to come up to my apartment to see my etchings?” The other says, “Sure, I’d love to see them.”

This is such a cliché that we might not even notice the deep paradox here. It’s like with life itself: people knew for thousands of years that every bird has the right kind of beak for its environment, but not until Darwin and Wallace could anyone articulate why (and only a few people before them even recognized there was a question there that called for a non-circular answer).

In our case, the puzzle is this: both people on the date know perfectly well that the reason they’re going up to the apartment has nothing to do with etchings. They probably even both know the other knows that. But if that’s the case, then why don’t they just blurt it out: “would you like to come up for some intercourse?” (Or “fluid transfer,” as the John Nash character put it in the Beautiful Mind movie?)

So here’s Pinker’s answer. Yes, both people know why they’re going to the apartment, but they also want to avoid their knowledge becoming common knowledge. They want plausible deniability. There are several possible reasons: to preserve the romantic fantasy of being “swept off one’s feet.” To provide a face-saving way to back out later, should one of them change their mind: since nothing was ever openly said, there’s no agreement to abrogate. In fact, even if only one of the people (say A) might care about such things, if the other person (say B) thinks there’s any chance A cares, B will also have an interest in avoiding common knowledge, for A’s sake.

Put differently, the issue is that, as soon as you say X out loud, the other person doesn’t merely learn X: they learn that you know X, that you know that they know that you know X, that you want them to know you know X, and an infinity of other things that might upset the delicate epistemic balance. Contrast that with the situation where X is left unstated: yeah, both people are pretty sure that “etchings” are just a pretext, and can even plausibly guess that the other person knows they’re pretty sure about it. But once you start getting to 3, 4, 5, levels of indirection—who knows? Maybe you do just want to show me some etchings.

Philosophers like to discuss Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty meeting in a train station, and Moriarty declaring, “I knew you’d be here,” and Holmes replying, “well, I knew that you knew I’d be here,” and Moriarty saying, “I knew you knew I knew I’d be here,” etc. But real humans tend to be unable to reason reliably past three or four levels in the knowledge hierarchy. (Related to that, you might have heard of the game where everyone guesses a number between 0 and 100, and the winner is whoever’s number is the closest to 2/3 of the average of all the numbers. If this game is played by perfectly rational people, who know they’re all perfectly rational, and know they know, etc., then they must all guess 0—exercise for you to see why. Yet experiments show that, if you actually want to win this game against average people, you should guess about 20. People seem to start with 50 or so, iterate the operation of multiplying by 2/3 a few times, and then stop.)

Incidentally, do you know what I would’ve given for someone to have explained this stuff to me back in high school? I think that a large fraction of the infamous social difficulties that nerds have, is simply down to nerds spending so much time in domains (like math and science) where the point is to struggle with every last neuron to make everything common knowledge, to make all truths as clear and explicit as possible. Whereas in social contexts, very often you’re managing a delicate epistemic balance where you need certain things to be known, but not known to be known, and so forth—where you need to prevent common knowledge from arising, at least temporarily. “Normal” people have an intuitive feel for this; it doesn’t need to be explained to them. For nerds, by contrast, explaining it—in terms of the muddy children puzzle and so forth—might be exactly what’s needed. Once they’re told the rules of a game, nerds can try playing it too! They might even turn out to be good at it.

OK, now for a darker example of common knowledge in action. If you read accounts of Nazi Germany, or the USSR, or North Korea or other despotic regimes today, you can easily be overwhelmed by this sense of, “so why didn’t all the sane people just rise up and overthrow the totalitarian monsters? Surely there were more sane people than crazy, evil ones. And probably the sane people even knew, from experience, that many of their neighbors were sane—so why this cowardice?” Once again, it could be argued that common knowledge is the key. Even if everyone knows the emperor is naked; indeed, even if everyone knows everyone knows he’s naked, still, if it’s not common knowledge, then anyone who says the emperor’s naked is knowingly assuming a massive personal risk. That’s why, in the story, it took a child to shift the equilibrium. Likewise, even if you know that 90% of the populace will join your democratic revolt provided they themselves know 90% will join it, if you can’t make your revolt’s popularity common knowledge, everyone will be stuck second-guessing each other, worried that if they revolt they’ll be an easily-crushed minority. And because of that very worry, they’ll be correct!

(My favorite Soviet joke involves a man standing in the Moscow train station, handing out leaflets to everyone who passes by. Eventually, of course, the KGB arrests him—but they discover to their surprise that the leaflets are just blank pieces of paper. “What’s the meaning of this?” they demand. “What is there to write?” replies the man. “It’s so obvious!” Note that this is precisely a situation where the man is trying to make common knowledge something he assumes his “readers” already know.)

The kicker is that, to prevent something from becoming common knowledge, all you need to do is censor the common-knowledge-producing mechanisms: the press, the Internet, public meetings. This nicely explains why despots throughout history have been so obsessed with controlling the press, and also explains how it’s possible for 10% of a population to murder and enslave the other 90% (as has happened again and again in our species’ sorry history), even though the 90% could easily overwhelm the 10% by acting in concert. Finally, it explains why believers in the Enlightenment project tend to be such fanatical absolutists about free speech—why they refuse to “balance” it against cultural sensitivity or social harmony or any other value, as so many well-meaning people urge these days.

OK, but let me try to tell you something surprising about common knowledge. Here at SPARC, you’ve learned all about Bayes’ rule—how, if you like, you can treat “probabilities” as just made-up numbers in your head, which are required obey the probability calculus, and then there’s a very definite rule for how to update those numbers when you gain new information. And indeed, how an agent that wanders around constantly updating these numbers in its head, and taking whichever action maximizes its expected utility (as calculated using the numbers), is probably the leading modern conception of what it means to be “rational.”

Now imagine that you’ve got two agents, call them Alice and Bob, with common knowledge of each other’s honesty and rationality, and with the same prior probability distribution over some set of possible states of the world. But now imagine they go out and live their lives, and have totally different experiences that lead to their learning different things, and having different posterior distributions. But then they meet again, and they realize that their opinions about some topic (say, Hillary’s chances of winning the election) are common knowledge: they both know each other’s opinion, and they both know that they both know, and so on. Then a striking 1976 result called Aumann’s Theorem states that their opinions must be equal. Or, as it’s summarized: “rational agents with common priors can never agree to disagree about anything.”

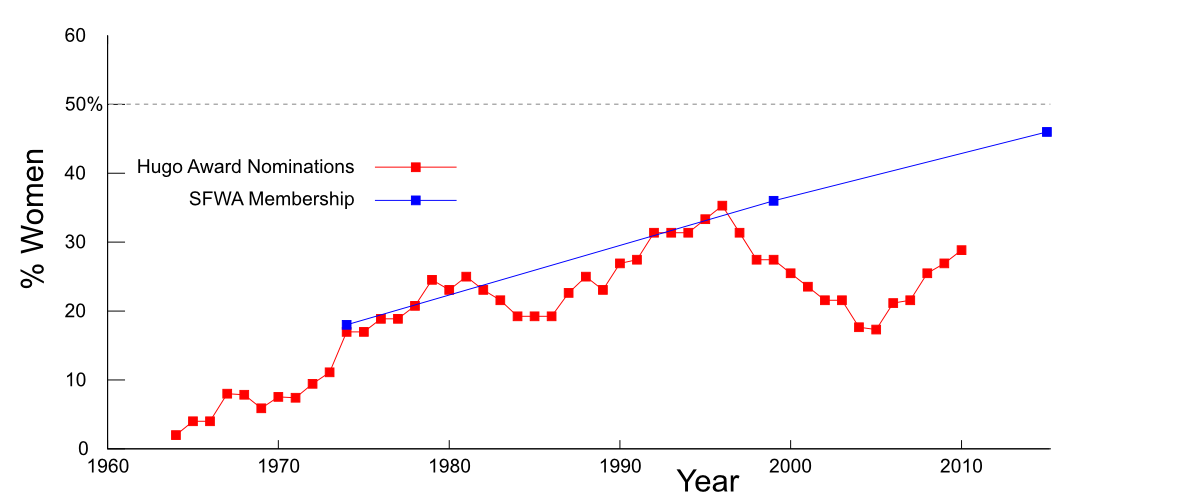

Actually, before going further, let’s prove Aumann’s Theorem—since it’s one of those things that sounds like a mistake when you first hear it, and then becomes a triviality once you see the 3-line proof. (Albeit, a “triviality” that won Aumann a Nobel in economics.) The key idea is that knowledge induces a partition on the set of possible states of the world. Huh? OK, imagine someone is either an old man, an old woman, a young man, or a young woman. You and I agree in giving each of these a 25% prior probability. Now imagine that you find out whether they’re a man or a woman, and I find out whether they’re young or old. This can be illustrated as follows:

The diagram tells us, for example, that if the ground truth is “old woman,” then your knowledge is described by the set {old woman, young woman}, while my knowledge is described by the set {old woman, old man}. And this different information leads us to different beliefs: for example, if someone asks for the probability that the person is a woman, you’ll say 100% but I’ll say 50%. OK, but what does it mean for information to be common knowledge? It means that I know that you know that I know that you know, and so on. Which means that, if you want to find out what’s common knowledge between us, you need to take the least common coarsening of our knowledge partitions. I.e., if the ground truth is some given world w, then what do I consider it possible that you consider it possible that I consider possible that … etc.? Iterate this growth process until it stops, by “zigzagging” between our knowledge partitions, and you get the set S of worlds such that, if we’re in world w, then what’s common knowledge between us is that the world belongs to S. Repeat for all w’s, and you get the least common coarsening of our partitions. In the above example, the least common coarsening is trivial, with all four worlds ending up in the same set S, but there are nontrivial examples as well:

Now, if Alice’s expectation of a random variable X is common knowledge between her and Bob, that means that everywhere in S, her expectation must be constant … and hence must equal whatever the expectation is, over all the worlds in S! Likewise, if Bob’s expectation is common knowledge with Alice, then everywhere in S, it must equal the expectation of X over S. But that means that Alice’s and Bob’s expectations are the same.

There are lots of related results. For example, rational agents with common priors, and common knowledge of each other’s rationality, should never engage in speculative trade (e.g., buying and selling stocks, assuming that they don’t need cash, they’re not earning a commission, etc.). Why? Basically because, if I try to sell you a stock for (say) $50, then you should reason that the very fact that I’m offering it means I must have information you don’t that it’s worth less than $50, so then you update accordingly and you don’t want it either.

Or here’s another one: suppose again that we’re Bayesians with common priors, and we’re having a conversation, where I tell you my opinion (say, of the probability Hillary will win the election). Not any of the reasons or evidence on which the opinion is based—just the opinion itself. Then you, being Bayesian, update your probabilities to account for what my opinion is. Then you tell me your opinion (which might have changed after learning mine), I update on that, I tell you my new opinion, then you tell me your new opinion, and so on. You might think this could go on forever! But, no, Geanakoplos and Polemarchakis observed that, as long as there are only finitely many possible states of the world in our shared prior, this process must converge after finitely many steps with you and me having the same opinion (and moreover, with it being common knowledge that we have that opinion). Why? Because as long as our opinions differ, your telling me your opinion or me telling you mine must induce a nontrivial refinement of one of our knowledge partitions, like so:

I.e., if you learn something new, then at least one of your knowledge sets must get split along the different possible values of the thing you learned. But since there are only finitely many underlying states, there can only be finitely many such splittings (note that, since Bayesians never forget anything, knowledge sets that are split will never again rejoin).

And something else: suppose your friend tells you a liberal opinion, then you take it into account, but reply with a more conservative opinion. The friend takes your opinion into account, and replies with a revised opinion. Question: is your friend’s new opinion likelier to be more liberal than yours, or more conservative?

Obviously, more liberal! Yes, maybe your friend now sees some of your points and vice versa, maybe you’ve now drawn a bit closer (ideally!), but you’re not going to suddenly switch sides because of one conversation.

Yet, if you and your friend are Bayesians with common priors, one can prove that that’s not what should happen at all. Indeed, your expectation of your own future opinion should equal your current opinion, and your expectation of your friend’s next opinion should also equal your current opinion—meaning that you shouldn’t be able to predict in which direction your opinion will change next, nor in which direction your friend will next disagree with you. Why not? Formally, because all these expectations are just different ways of calculating an expectation over the same set, namely your current knowledge set (i.e., the set of states of the world that you currently consider possible)! More intuitively, we could say: if you could predict that, all else equal, the next thing you heard would probably shift your opinion in a liberal direction, then as a Bayesian you should already shift your opinion in a liberal direction right now. (This is related to what’s called the “martingale property”: sure, a random variable X could evolve in many ways in the future, but the average of all those ways must be its current expectation E[X], by the very definition of E[X]…)

So, putting all these results together, we get a clear picture of what rational disagreements should look like: they should follow unbiased random walks, until sooner or later they terminate in common knowledge of complete agreement. We now face a bit of a puzzle, in that hardly any disagreements in the history of the world have ever looked like that. So what gives?

There are a few ways out:

(1) You could say that the “failed prediction” of Aumann’s Theorem is no surprise, since virtually all human beings are irrational cretins, or liars (or at least, it’s not common knowledge that they aren’t). Except for you, of course: you’re perfectly rational and honest. And if you ever met anyone else as rational and honest as you, maybe you and they could have an Aumannian conversation. But since such a person probably doesn’t exist, you’re totally justified to stand your ground, discount all opinions that differ from yours, etc. Notice that, even if you genuinely believed that was all there was to it, Aumann’s Theorem would still have an aspirational significance for you: you would still have to say this is the ideal that all rationalists should strive toward when they disagree. And that would already conflict with a lot of standard rationalist wisdom. For example, we all know that arguments from authority carry little weight: what should sway you is not the mere fact of some other person stating their opinion, but the actual arguments and evidence that they’re able to bring. Except that as we’ve seen, for Bayesians with common priors this isn’t true at all! Instead, merely hearing your friend’s opinion serves as a powerful summary of what your friend knows. And if you learn that your rational friend disagrees with you, then even without knowing why, you should take that as seriously as if you discovered a contradiction in your own thought processes. This is related to an even broader point: there’s a normative rule of rationality that you should judge ideas only on their merits—yet if you’re a Bayesian, of course you’re going to take into account where the ideas come from, and how many other people hold them! Likewise, if you’re a Bayesian police officer or a Bayesian airport screener or a Bayesian job interviewer, of course you’re going to profile people by their superficial characteristics, however unfair that might be to individuals—so all those studies proving that people evaluate the same resume differently if you change the name at the top are no great surprise. It seems to me that the tension between these two different views of rationality, the normative and the Bayesian, generates a lot of the most intractable debates of the modern world.

(2) Or—and this is an obvious one—you could reject the assumption of common priors. After all, isn’t a major selling point of Bayesianism supposed to be its subjective aspect, the fact that you pick “whichever prior feels right for you,” and are constrained only in how to update that prior? If Alice’s and Bob’s priors can be different, then all the reasoning I went through earlier collapses. So rejecting common priors might seem appealing. But there’s a paper by Tyler Cowen and Robin Hanson called “Are Disagreements Honest?”—one of the most worldview-destabilizing papers I’ve ever read—that calls that strategy into question. What it says, basically, is this: if you’re really a thoroughgoing Bayesian rationalist, then your prior ought to allow for the possibility that you are the other person. Or to put it another way: “you being born as you,” rather than as someone else, should be treated as just one more contingent fact that you observe and then conditionalize on! And likewise, the other person should condition on the observation that they’re them and not you. In this way, absolutely everything that makes you different from someone else can be understood as “differing information,” so we’re right back to the situation covered by Aumann’s Theorem. Imagine, if you like, that we all started out behind some Rawlsian veil of ignorance, as pure reasoning minds that had yet to be assigned specific bodies. In that original state, there was nothing to differentiate any of us from any other—anything that did would just be information to condition on—so we all should’ve had the same prior. That might sound fanciful, but in some sense all it’s saying is: what licenses you to privilege an observation just because it’s your eyes that made it, or a thought just because it happened to occur in your head? Like, if you’re objectively smarter or more observant than everyone else around you, fine, but to whatever extent you agree that you aren’t, your opinion gets no special epistemic protection just because it’s yours.

(3) If you’re uncomfortable with this tendency of Bayesian reasoning to refuse to be confined anywhere, to want to expand to cosmic or metaphysical scope (“I need to condition on having been born as me and not someone else”)—well then, you could reject the entire framework of Bayesianism, as your notion of rationality. Lest I be cast out from this camp as a heretic, I hasten to say: I include this option only for the sake of completeness!

(4) When I first learned about this stuff 12 years ago, it seemed obvious to me that a lot of it could be dismissed as irrelevant to the real world for reasons of complexity. I.e., sure, it might apply to ideal reasoners with unlimited time and computational power, but as soon as you impose realistic constraints, this whole Aumannian house of cards should collapse. As an example, if Alice and Bob have common priors, then sure they’ll agree about everything if they effectively share all their information with each other! But in practice, we don’t have time to “mind-meld,” swapping our entire life experiences with anyone we meet. So one could conjecture that agreement, in general, requires a lot of communication. So then I sat down and tried to prove that as a theorem. And you know what I found? That my intuition here wasn’t even close to correct!

In more detail, I proved the following theorem. Suppose Alice and Bob are Bayesians with shared priors, and suppose they’re arguing about (say) the probability of some future event—or more generally, about any random variable X bounded in [0,1]. So, they have a conversation where Alice first announces her expectation of X, then Bob announces his new expectation, and so on. The theorem says that Alice’s and Bob’s estimates of X will necessarily agree to within ±ε, with probability at least 1-δ over their shared prior, after they’ve exchanged only O(1/(δε2)) messages. Note that this bound is completely independent of how much knowledge they have; it depends only on the accuracy with which they want to agree! Furthermore, the same bound holds even if Alice and Bob only send a few discrete bits about their real-valued expectations with each message, rather than the expectations themselves.

The proof involves the idea that Alice and Bob’s estimates of X, call them XA and XB respectively, follow “unbiased random walks” (or more formally, are martingales). Very roughly, if |XA-XB|≥ε with high probability over Alice and Bob’s shared prior, then that fact implies that the next message has a high probability (again, over the shared prior) of causing either XA or XB to jump up or down by about ε. But XA and XB, being estimates of X, are bounded between 0 and 1. So a random walk with a step size of ε can only continue for about 1/ε2 steps before it hits one of the “absorbing barriers.”

The way to formalize this is to look at the variances, Var[XA] and Var[XB], with respect to the shared prior. Because Alice and Bob’s partitions keep getting refined, the variances are monotonically non-decreasing. They start out 0 and can never exceed 1 (in fact they can never exceed 1/4, but let’s not worry about constants). Now, the key lemma is that, if Pr[|XA-XB|≥ε]≥δ, then Var[XB] must increase by at least δε2 if Alice sends XA to Bob, and Var[XA] must increase by at least δε2 if Bob sends XB to Alice. You can see my paper for the proof, or just work it out for yourself. At any rate, the lemma implies that, after O(1/(δε2)) rounds of communication, there must be at least a temporary break in the disagreement; there must be some round where Alice and Bob approximately agree with high probability.

There are lots of other results in my paper, including an upper bound on the number of calls that Alice and Bob need to make to a “sampling oracle” to carry out this sort of protocol approximately, assuming they’re not perfect Bayesians but agents with bounded computational power. But let me step back and address the broader question: what should we make of all this? How should we live with the gargantuan chasm between the prediction of Bayesian rationality for how we should disagree, and the actual facts of how we do disagree?

We could simply declare that human beings are not well-modeled as Bayesians with common priors—that we’ve failed in giving a descriptive account of human behavior—and leave it at that. OK, but that would still leave the question: does this stuff have normative value? Should it affect how we behave, if we want to consider ourselves honest and rational? I would argue, possibly yes.

Yes, you should constantly ask yourself the question: “would I still be defending this opinion, if I had been born as someone else?” (Though you might say this insight predates Aumann by quite a bit, going back at least to Spinoza.)

Yes, if someone you respect as honest and rational disagrees with you, you should take it as seriously as if the disagreement were between two different aspects of yourself.

Finally, yes, we can try to judge epistemic communities by how closely they approach the Aumannian ideal. In math and science, in my experience, it’s common to see two people furiously arguing with each other at a blackboard. Come back five minutes later, and they’re arguing even more furiously, but now their positions have switched. As we’ve seen, that’s precisely what the math says a rational conversation should look like. In social and political discussions, though, usually the very best you’ll see is that two people start out diametrically opposed, but eventually one of them says “fine, I’ll grant you this,” and the other says “fine, I’ll grant you that.” We might say, that’s certainly better than the common alternative, of the two people walking away even more polarized than before! Yet the math tells us that even the first case—even the two people gradually getting closer in their views—is nothing at all like a rational exchange, which would involve the two participants repeatedly leapfrogging each other, completely changing their opinion about the question under discussion (and then changing back, and back again) every time they learned something new. The first case, you might say, is more like haggling—more like “I’ll grant you that X is true if you grant me that Y is true”—than like our ideal friendly mathematicians arguing at the blackboard, whose acceptance of new truths is never slow or grudging, never conditional on the other person first agreeing with them about something else.

Armed with this understanding, we could try to rank fields by how hard it is to have an Aumannian conversation in them. At the bottom—the easiest!—is math (or, let’s say, chess, or debugging a program, or fact-heavy fields like lexicography or geography). Crucially, here I only mean the parts of these subjects with agreed-on rules and definite answers: once the conversation turns to whose theorems are deeper, or whose fault the bug was, things can get arbitrarily non-Aumannian. Then there’s the type of science that involves messy correlational studies (I just mean, talking about what’s a risk factor for what, not the political implications). Then there’s politics and aesthetics, with the most radioactive topics like Israel/Palestine higher up. And then, at the very peak, there’s gender and social justice debates, where everyone brings their formative experiences along, and absolutely no one is a disinterested truth-seeker, and possibly no Aumannian conversation has ever been had in the history of the world.

I would urge that even at the very top, it’s still incumbent on all of us to try to make the Aumannian move, of “what would I think about this issue if I were someone else and not me? If I were a man, a woman, black, white, gay, straight, a nerd, a jock? How much of my thinking about this represents pure Spinozist reason, which could be ported to any rational mind, and how much of it would get lost in translation?”

Anyway, I’m sure some people would argue that, in the end, the whole framework of Bayesian agents, common priors, common knowledge, etc. can be chucked from this discussion like so much scaffolding, and the moral lessons I want to draw boil down to trite advice (“try to see the other person’s point of view”) that you all knew already. Then again, even if you all knew all this, maybe you didn’t know that you all knew it! So I hope you gained some new information from this talk in any case. Thanks.

Update: Coincidentally, there’s a moving NYT piece by Oliver Sacks, which (among other things) recounts his experiences with his cousin, the Aumann of Aumann’s theorem.

Another Update: If I ever did attempt an Aumannian conversation with someone, the other Scott A. would be a candidate! Here he is in 2011 making several of the same points I did above, using the same examples (I thank him for pointing me to his post).