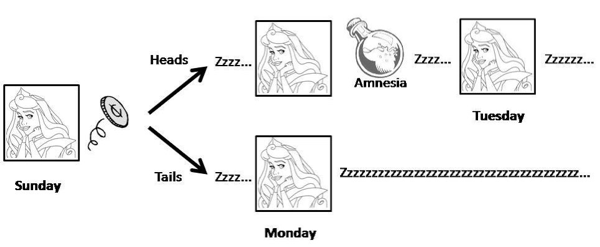

Post-Spoilerocalyptic.I went to see

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. Banalities first: A well-crafted film. Cogent and coherent in terms of aesthetics and plot (though there is a pleasingly bathetic moment when, following lots of atmospheric shots of apes engaged in social interaction, one ape suddenly addresses another in sign language as "Maurice"). Nicely acted by the principles.

Now.

In

The Dark Ape Rises, the 'good' ape leader is Caesar and the 'bad' ape leader is Koba.

Caesar is the reasonable one, the compromiser, who wants peace with the humans. Koba is the nasty one who can't let go of his resentment of humans, who doesn't trust them, who betrays Caesar and launches an all-out war against the humans.

Thing is, Koba is fucking awesome. Because, unlike Caesar, he understands that when you have the oppressor on the floor, you don't help him up and dust him down. No. You stand on his neck.

|

| Here's Koba, riding straight at the enemy (who are armed with rocket launchers by this point) while simultaneously holding (and firing) two machine guns instead of the reins of his horse. Caesar never does anything this fucking spectacularly brave and principled in the entire course of the movie. |

It reminds me of what Philomena Cunk once said in reference to the revolution advocated by Russell Brand. She worried about it until she realised that it was a revolution in the mind... which is safer than a real revolution because nothing actually changes.

Revolutionaries are all very well, you see, until they actually start doing anything, or - horror of horrors - winning. You're allowed to be a radical or a rebel or a firebrand, as long as you are a noble failure. That's why Rosa Luxemburg - through no fault of her own, may I stress - is sentimentalised, whereas Lenin is the epitome of evil.

There's been much comment from the critiots that this film is good because there are no fully good or bad characters, and everyone means well. Bollocks. Koba might be portrayed as doing what he thinks best, at least part of the time, but he clearly becomes the bad guy. He even dies the traditionally spectacular/poetically-just villain death.

Koba is certainly a bastard. You see, he immediately turns into a psycho when he becomes a political rebel from Caesar's benevolent dictatorship. As usual, inhabiting a zone outside moderate compromise with the status quo and the oppressors is an instant ticket into psychological instability and evil. The radical is, by definition, an 'extremist', and the extremist is, by definition, both a fanatic and a nihilist, a dangerous utopian and a cynic, a zealot and a self-interested machiavel, a demogogue and an autocrat.

Caesar isn't the only ape in the film with a name that recalls a famous political figure from human history. 'Koba', you'll no doubt remember, was a nickname once used by Stalin. Hence the title of Martin Amis' truculently inconsequential book

Koba the Dread.It will be noticed that, after his insurrection succeeds, Koba immediately sets about herding humans into a gulag, killing any apes who defy his authority, and locking up any potential dissidents who may be too loyal to Caesar's old regime - presumably to await show trials. His revolt takes on the inevitable contours of any radical change - as told by the drearily predictable liberal view of politics.

Koba is, once again, the revolutionary as maniacal murderer, as traitor and tyrant, as cheerleader for slaughter, as the foaming radical who really just wants power. This characterisation sits perfectly happily alongside the efforts made in every other bit of the script to indicate nuance and complexity - precisely because, in the mainstream liberal view of politics, the depiction of the firebrand as instant tyrant

is considered a nuanced and complex view (instead of, say, a childish, smug, ahistorical oversimplification).

There is simply no need for the text to explain how and why Koba goes from his entirely reasonable mistrust and hatred of humans (see below) to his conspiracy, his bid for power, his betrayal of his old comrade Caesar. It is so self-evident to this way of thinking that it requires no explanation. The opponent of 'peace' and 'stability' (i.e. Things As They Are) is, by definition, also the tyrant-in-waiting. The radical is, by definition, a psychopath.

But, until he fails to die the hero and thus lives long enough to see himself become the villain, Koba is objectively a better judge of what's going on that Caesar... or, apparently, the writers.

We're supposed to be watching a story about 'two tribes' who mistrust and fear each other, with 'extremists' on both sides who hate the other side unreasoningly. The idea is the standard liberal accounting for inter-group rivalry and violence. Ethnic differences + fear + extremism x misunderstanding = war. But in this movie, the equivalence between the two groups and their responses - which we are clearly meant to take for granted - is

always false.

On the human side, the warmonger characters hate the apes because they started the Simian Flu which wiped out most of the human race (a view explicitly shown to be wrong and unfair by another human character), or because "they're animals" (thus bigotedly rejecting the apes' claim to fair treatment by disputing their sentience). That's it. On the ape side, by marked contrast, the warmonger characters - chiefly Koba - hate the humans because they kept apes in cages (true) and tortured them (true) and mutilated them (true) and experimented upon them (true), and because they're dangerous owing to their enormous stockpile of deadly weapons (true). The initial contact between Caesar's groups of apes and the human survivors in San Francisco comes when humans trespass upon ape terrirory (albeit unwittingly) and immediately shoot an ape without provocation, nearly killing him.

In measured response to this, Caesar decides upon a show of strength and a warning. The apes turn up on the humans' doorstep and say "don't come back". Whereupon the 'goodie' human character - Malcolm (played by some guy who isn't Mark Ruffalo) - goes back into the apes' forest, this time fully aware that he is trespassing and unwelcome. Okay, he's trying to prevent an attack upon the apes by Dreyfuss (the boss of the survivors, played by Gary Oldman)... but his aim is to get permission for his team to work on the dam situated in the apes' forest, and get power flowing back to San Francisco. Malcom tacitly accepts the premise that the apes must agree to human terms or be annihilated. He doesn't like it (you can tell because he frowns a lot) but he accepts it. He never gives any apparent thought to challenging Dreyfuss' authority. There doesn't appear to be any semblance of democracy in the human camp. Malcolm certainly never raises the possibilty of asking the people what they think. The film seems to work on the assumption that the ordinary people are a fearful mass who alternate between mindless panic and obedience to the guy with a megaphone... at least until they get too hungry, whereupon they will tear him to pieces. (An essential corollary of the 'two tribes' paradigm is that people are 'tribal' in the worst and most racist sense of that term, i.e. a cowering mass of ignorant savages waiting on the word of the Chief.) So Malcolm undertakes to explain to the apes that they must let humans fix their dam.

Gee, giving humans power. What could

possibly go wrong?

Let me ask you something. If you were living in the ruins of a planet destroyed by the technology of a specific group of people, and that same group of people had kept you in cages, tortured you, experimented upon you, maimed you, dissected your kids and hunted you almost to extinction (or wrecked the ecosystem to the point where your people found it increasingly hard to survive), and that group of people was powerless... wouldn't you feel safer? And would you think it a tremendously attractive and sensible idea to let said group of people add a constant source of electrical power to their already existing stockpile of high-tech weaponry?

Okay, so I get that the human survivors in San Francisco are not specifically the same humans who are personally responsible for all that stuff... but the logic of the film depends upon that 'two tribes' thing I was just talking about, and thus depends upon the idea that we're seeing two groups with essentialised and generalised features who face each other across a chasm. By that logic, Koba's mistrust of humans as a group, or a race, is entirely reasonable. It's not how I look at humans (balls to collective responsibility - most of what's wrong with this planet is the work of a minority and their system), but it seems to be how the filmmakers do - and Koba has, quite reasonably, picked up on this facet of how his world works.

At the point where Koba tries to kill Caesar, Caesar is handing the humans access to electricity. Caesar is himself a despot, albeit a benevolent one from 'our' point of view (i.e. he is sympathetic to humans and wants peace... or, to put it another way, he's a reasonable negotiating partner 'we' can get round the table with... because that's all 'we' ever want, right?). When Koba shoots Caesar, it isn't like he's stepping that far out of the established ape custom of settling disagreements over status through fights. Yes, he's violating the commandment 'APE NOT KILL APE', but then Caesar is endangering the lives of the apes by helping the humans.

Let's be honest here. The humans, at this point, have a huge stockpile of deadly weapons, no semblance of a liberal democratic political structure, urgent needs for land and food, a miserable track record when it comes to apes, newly restored electricity and - as is soon shown - contact with other groups of armed humans!

They are, by any sane definition, a deadly threat to the apes. It's ludicrous to pretend otherwise, even within the schema of the text. (Outside the schema of the text, such pretence depends upon complete ignorance of how armed modern Westerners behave towards small groups whom they consider 'primitive' and who happen to live on land they want.) Koba is, sadly, absolutely right in his judgement. It's all very well to shake one's head and say, echoing the movie's familiar tagline, "it was our last hope for peace"... but that view depends upon the idea that a few compromisers on either side can efface that fact that one group is the long-established historical oppressor and now, once again, has access to overwhelming strength.

In the end,

Apefall is just another new reiteration of a very old American story: the struggle over land, with the role of Americans taken by humans ("there's humans and then there's Commanches") and the role of 'Indians' taken by apes. In the old days, the narrative was fairly simple and crude. Manifest Destiny meets scalping parties. These days we're more nuanced. Now it's Guilt-Ridden Manifest Destiny meets scalping parties, some of whom are almost as reasonable as 'us'.

(BTW - if you think I'm being racist when I compare the apes to, say, Native Americans... well, it was the film that started it. I'm just running with

their logic. And you should note that it is a racial logic deeply embedded in the franchise. The original Charlton Heston movie is a 'satire' of the civil rights movement - via an employment of the 'world turned upside down' trope - in which black people are implicitly represented as apes.)

In yet another way, the idea that the two sides are balanced is untrue. The film tries to put roughly equivalent characters on either side of the human/ape divide. But Caesar's counterpart is Malcolm and Koba's is Dreyfuss. So on the ape side we have a well-meaning

leader, and on the human side we have a well-meaning

subordinate (thus effacing the important reality of power in favour of the value of intentions - a classic liberal mistake). On the ape side we have a psychopathic killer driven by personal ambition versus a human warmonger who is actually shown to be a well-intentioned leader. Dreyfuss wants to save the human race and is humanised via a scene where he cries over photos of lost sons. Thus an evil revolutionary is pitted against a misguided patriot - we even see Dreyfuss' old photos from his army days in the desert.

Even as the film strives to create a morality play about the road to hell being paved with good intentions, and there being faults on both sides, etc, it falls back into ideology. It falls back into the classic ideological demonology of fearful liberalism: those who strive stumblingly for compromise versus the vicious zealot.

Koba is outnumbered. He has to shoulder all the burden of radicalism, and thus become a monster, while the rest of the protagonists - even the most bastardly of the humans - get at least partially absolved.

In

Ape Trek into Darkness, as always, the oppressed are held to a higher standard of morality, forgiveness and forbearance than the oppressors (or, in this case, the erstwhile oppressors).

Koba's great crime is that he refuses the onus of greater moral responsibility foisted upon him by his former oppressors (and the filmmakers). He quite rightly tells them to go fuck themselves, and the pleas for peace they bring too late to the table, alongside their quest for back-up and juice. And then he starts fighting against what is, as I say, by any sane definition, a proven and deadly threat (I'm sure someone, if the roles were reversed, would call it a 'clear and present danger' and authorise drone strikes against it).

I bow to no-one in my loathing of Stalin. He was arguably the most despicable human being who ever lived. He is a smear of blood and shit on the good name of socialism. But he was the embodiment of class forces, and rose to power on his opportunistic co-optation of those class forces, not on a wave of charisma and evil stemming directly from his ideology or fanaticism. He was the most ruthless and well-placed representative of the bureaucratic layer in the Soviet government which filled a gaping hole in the power structure after the Russian Civil War (which was forced on the Bolsheviks by Western capitalist aggression) decimated the Russian working class, thus gutting the soviet system. He wasn't the bogey man. He wasn't Bolshevism in its true and terrible form, or any such ahistorical nonsense. He was the head of a bureaucratic state capitalist government (in which capital still existed, but as an exploitative relation between the worker and the state) which put Russia through a speeded-up and concentrated form of capitalist development and industrialisation. Russia did in the space of a couple of decades what the European capitalist powers had taken a couple of centuries to do. Stalin matched them point for point. All the horrors of primitive accumulation (the early stage of capitalist development) are represented in the Stalin years. In the West they were called the enclosures, in Stalin's Russian it was called 'collectivisation'. It was essentially the same thing: the state-enforced destruction of feudal property and the peasantry - and its transformation into capital of one kind or another - leading to dispossession, famine, the theft of common lands, the severing of people from direct access to agricultural production, and the forcing of people into wage labour. Stalin engineered terrible famines. The British Empire did exactly the same thing in Ireland and India. In Stalin's Russian you had the horrors of the Gulag; in Europe and America you had the horrors of plantation slavery, child labour and the industrial revolution. The state owned and controlled all capital in Russia, and it was administered by a class of bureaucrats. In rising European capitalist formations, the state played a less direct but no less crucial role in enforcing the 'rights' of private capital, and financially supporting the new system. Both Russia and the West engaged in ruthless imperialism to acquire territory, manpower and resources to feed into the system. If Russia was 'totalitarian', the Britain of Pitt was no democracy. Stalin was a monster because he was the dictator of a state engaged in industrialisation at breakneck speed. All the horrors of emergent capitalism were squeezed into the tight space of the rule of one man. Stalin is horrific because he is Russia's version of all the capitalists and prime ministers of Europe, fused into one bloated personage. That isn't to excuse him, any more than to point out that capitalism is a systemic evil is to excuse Rupert Murdoch, but it does put him in context. He may have been a psychopath, but millions didn't die solely because he was, and it wasn't Bolshevism that made him one. It was the logic of capital, albeit state capital. Industrialisation, squidged into a sliver of historical time, because - as Stalin himself pointed out - of the need for the Soviet Union to compete militarily and economically with the Western capitalist powers. (This, by the way, is why I find it beyond comprehension how anyone can fail to see the state capitalist nature of Stalin's Russia - if it competed economically with capitalist powers in a capitalist world system, how can it possibly have been anything other than some form of capitalism?)

(Quite apart from anything else, if we allow Koba the Ape to stand for Koba the Dread, this does the Dread a massive favour. Stalin was a nonentity and a workhorse in the early Bolshevik party, who played little significant role in the Russian Revolution, contrary to his own subsequent mythmaking. He certainly never charged at rocket launchers.)

It is, by the way, explicitly capitalism that the humans want to bring back. The dam is a symbol for holding back the tide of untamed and destructive nature (and/or time), and a vast engineering project of modernity that reshapes the natural world to human needs, and a way of providing water and power to settlements and thus making 'civilisation' possible. By 'civilisation', in

Planet of the Apes 2.2: Age of Extrinction, we are to understand capitalism. The humans explicitly talk about wanting to bring back the life they once had. In other words, they want

ourworld back - the very world that caused its own downfall in the first place. The film makes it aesthetically explicit that the return of capitalism is aimed at. When the humans manage to get their dam working again, and thus get power to flow back to San Francisco, they celebrate in the reactivated shell of a petrol station, and people dance through a relit shopping mall. Dreyfuss celebrates by turning on his expensive Apple rectangle for the first time in years and looking through his My Pictures folder.

It's only to be expected. Popular movies are currently absolutely stuffed with the motif of the hero and/or the world

fallen and trying to arise. You don't need to be a particularly subtle critic to work out what that's all about (though, needless to say, it escapes most of the professionals). It stretches from Bond and Batman recovering their mojos, to the

de rigeur device of the fallen paradise that must be reclaimed

(Oblivion, Elysium, The Hobbit, etc). It is a current inflection of the perennially-popular apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic movie.

The Apeit: The Desolation of Koba is no exception. It fits into the currently popular trope in a way similar to

Game of Thrones, with its mantra "Winter is coming". A great crisis has come or is approaching (

Game of Apes manages to at least make the crisis something of our doing... though there is something to be said for GRRM's great inevitable cycles of boom and slump that helpless people get caught in). In both, the legions of the disavowed will swamp us along with the glaciers or germs of doom. We squabble about the political organisation of structures that will soon be rendered obsolete by waves of inexplicable and uncanny and unappeasable apocalypses that steadily approach. The White Walkers are the unknowable shock troops of the big freeze that will paralyse the clockwork and the engines that we currently rely on. The apes, similarly, are the post-apocalyptic hordes, resentful and out for revenge. Again, in the midst of the biggest recession since the 30s, none of this is especially hard to parse.

Of course, by enjoying Koba's brave rebellion, I am only really doing something the text wants me to. The moral rhetoric of the narrative may not support him (even though the facts of the plot do), but the whole aesthetic logic of the film is predicated upon him and his war. We go to see films like this for the same reason that we recessionitizens go to see so many zombie films. We

want to see the world smashed up by the monsters in a state of riotous assembly and insurrectionary carnival. It connects with a deep-seated desire to see the world turned upside down. Of course, the dominant ideology demands that the carnival of the oppressed be curtailed in salutary fashion. But even so...

I wrote

here about how attractive villains are, about how they often appear to have an objectively better moral and political position than the goodies (who are often only good by default because they represent established power structures and their violence is institutionalised), about how seeing the monsters rip the world to bits can be very thrilling if you're not keen on the world as it stands, about how the villains shoulder the burden of perpetual defeat so that we can learn our lesson of obedience... but also so that we can get a charge from their rebellion against the status quo, and about how the evil objections of the villain often represent a garbled form of protest against the established order.

For instance, Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter franchise represents - like so many villains - the distant and distorted echo of the snarl of radical anger. He is himself thoroughly unsympathetic, as Koba comes to be when he starts murdering other apes. However, even thoroughly unsympathetic villains like Voldemort (who, as the snobbish fuhrer of the magic-Nazis, is not someone I’d vote for) tend to represent the - to use a hackneyed phrase - ‘return of the repressed’. And repression is political. That which is oppressed is also repressed in mainstream discourse. Voldemort can ascend because he takes advantage of faultlines in Wizarding society that reveal deep, structural injustice and hypocrisy, ie the ethnic cleansing of the giants, the economic ghettoisation of the Goblins, the resolutely undemocratic and unaccountable nature of Wizarding government, the enslavement of the Elves, etc. Now, J.K. Rowling never really addresses these problems. She occasionally has goodie characters display a bad conscience about them (ie Hermione’s patronising SPEW campaign and Dumbledore’s occasional remarks to Harry about how badly Wizards have treated other races) but the addressing or remedying of these injustices is NEVER made crucial as a precondition of saving the Wizarding World. The Wizards never really have to face the consequences of these injustices, or change them.

Harry & Co fight to reinstate the status quo that includes all these structural injustices. The happy ending involves no emancipation of the Elves, no change in Wizarding attitudes to giants (indeed, Rowling makes it clear that the Wizards are essentially right about the respectively servile and primitive nature of these races!) The happy ending involves no real tackling of the deep strain of racial prejudice about bloodlines. The happy ending involves one of the goodies being ‘appointed’ the new (unelected) Minister of Magic. Etc. It’s clear what this means. The only person fighting to

change the Wizarding World was Voldemort. The baddie. The goodies were all fighting to, a few tweaks aside, keep it

exactly the same. This is why I have a sneaking sympathy even with Voldemort. He was, at least, trying to change things. Like Koba, he represents the deep-seated assumption in capitalist media culture that any attempt at radical social change must be, by definition, evil: fanatical, twisted, dangerous, pathological, selfish, etc. Voldemort doesn’t espouse values I’d embrace… but I do feel a certain kinship even for him, as a figure within the text. Because he’s the guy who says ‘this society is broken and we need to radically change it’. His ideas about how it’s broken are noxious, but that’s because he’s a bourgeois echo - distorted and distant - of anyone who wants radical change. It’s like with Shinzon: he’s personally vile, but - being the leader of a slave rebellion which confronts the oppressing empire - he’s also a reflection (in a shattered mirror) of Spartacus.

Similarly, in

Koba and the Deathly Humans, Koba is the only one fighting to radically change the status quo, the only one with a practical grasp of what needs to be done to keep the apes safe from the danger they clearly face, and the first one with the guts to pick up weapons and fight. If he has to trick the rest of the apes into following him, that just shows that the filmmakers are working on the same assumption about the 'ordinary' apes as they made about the 'ordinary' humans: they're sheep.

The passivity of the masses is a theme right the way through the film. There are a quartet of Alpha Males (of different styles) making all the running. The climax of the film depends upon two seperate sets of Alpha Males duking it out between them. (Incidentally, the only women in this film are... well... incidental. Malcolm has a girlfriend who is there to give people antibiotics and look sad and be supportive; Caesar has a mate who is there to have babies, be ill and then get better - much to his relief.)

It's possible that the Alpha Males, the submissive Beta Males and the Obedient Females are there on both sides as part of the declared strategy of showing the humans and apes mirroring each other, of showing how much they have in common. If so, its not really exceptional in terms of being reactionary and reductionist and biological determinist - these sorts of assumptions are widespread, especially in narrative culture - but it

is noticeable how they do it without so much as whispering about evolution or common descent. Presumably this is from fear of incurring the wrath of America's Christian Creationist hordes (just goes to show how seriously they take ideological sensitivities when they sense box office impacts).

On a related issue, I personally found it irritating how undecided the filmmakers were about how to present ape culture. On the one hand they want the apes to be 'advanced' and human-like in their social organisation, yet they also want them to act like stereotypical apes. So you end up with a mish-mash. The apes are shown to have a literate culture, with written words and sign language alongside the few who can speak, and with a school for the little 'uns - complete with anachronistic lessons in chalk on an improvised blackboard (insert blackboard jungle joke here). They have midwives, buildings in their settlement, etc. Yet they have none of the broadly egalitarian social structure that you

tend to see in real hunter-gatherer groups untouched or unmenaced by exterior threats. Of course, they're apes rather than human hunter gatherers... but then, with such intrusions of human social structure into the apes' society (including such wholly anachronistic ones as school and the nuclear family), why not also bring in egalitarianism? The answer lies in the overarching view of people as 'tribal' in the negative sense.

It's this view that ultimately underwrites all the stuff about Koba the demagogue, swaying the apes to become his whooping pawns in a race war. If people - hairy or smooth - are hierarchical, sheeplike, aggressive, fearful, passive, prone to obedience, naturally separated into Alpha Males and their subjects... and if they're prone to this because of their essentially apelike nature... then no wonder attempts to rebel against the status quo always end up with someone like Koba taking charge and becoming the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss.

This is the logic of the work, and it has never been more necessary for the capitalist culture industries to peddle this message than at times of crisis. If you think I'm being paranoid, then you're missing neoliberalism's skill at regulating opinion using marketised ideology.

I hear that Andy Serkis (who plays Caesar in this film via motion capture) is going to be doing a CGI/mo-cap version of

Animal Farm. Another retelling of that simplistic fable that puts an allegorical revolution into the world of the beasts, showing the inevitable course of that revolution from liberation to tyranny, from the charisma of the leader to the totalitarian rule of the dictator. In the film I just saw, the animal/tyrant is indirectly named after Stalin. In

Animal Farm, the animal/tyrant who represents Stalin is called Napoleon.

Caesar, Napoleon, Stalin. The inevitable gravediggers of revolution* - as long as you ignore all context and look upon them as ahistorical bogeymen.

You see, you animals, where trying to change the world gets you every time?

*It's actually a bit more complicated than that in

the case of the real Julius Caesar.