This is meant to be a quick overview and primer of the flippy disk and disk hardware situation with regards to 5.25″ floppy drives. It is for reference and referral by others for an easy understanding of the issues.

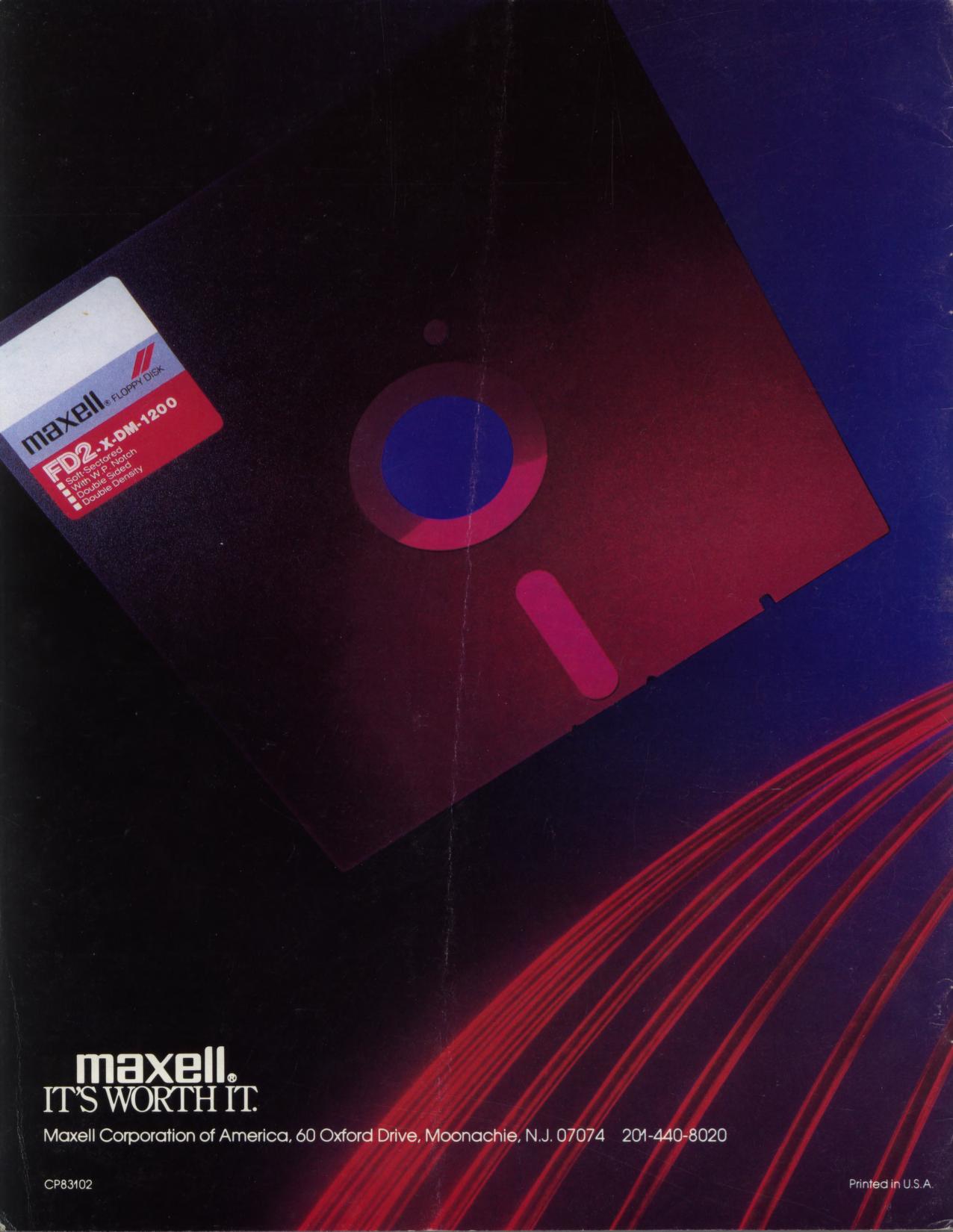

Right now, there are tens of thousands of floppy disks out there that were used extensively in the 1980s and 1990s to store data, much of it one of a kind, on home computers. They looked like this:

Yes, even with the lighting and glowy strings. This is what the 1980s looked like, deal with it.

The capacity of these floppies ranged, but were generally very small by today’s standards – between 88k and 3 megabytes, with a lot of them being 140k. To give perspective, that image of the floppy disk is 144k.

Myself and many others have said that with the floppy disks now going into decades of existence, the ability for them to read any data that was put on them so long ago is a bit of a crapshoot. Either it works great to the present day, or it is gone, gone, gone.

It is incumbent on the present-day world to rescue and preserve the data off these floppies, as the choice won’t be left to the next generations to do so. Debates about the worthiness of the data are fine enough, but in another few years the debate will not be about whether items can be saved, but how best to work with, present, and study all that was saved. It is a dying medium and resource.

Currently, there are three methods to transfer the data off these floppy disks, one of which doesn’t exist yet.

- Original Floppy Drive from Original System

- Repurposed General-Purpose Floppy Drive

- The Flop-o-suckerator 3000

The Flop-o-Suckerator 3000, while not currently extant, is likely to be a customized piece of hardware that takes in a floppy disk and “does stuff” to it 100% geared towards pulling all the data off it, and having no other real function. There are examples of this approach for audio cassettes, books, and even business cards. Chris Fenton famously made such a device for Cray Disk Packs, so this isn’t entirely theory – there just will be one made for floppies. Anyway, back to contemporary reality.

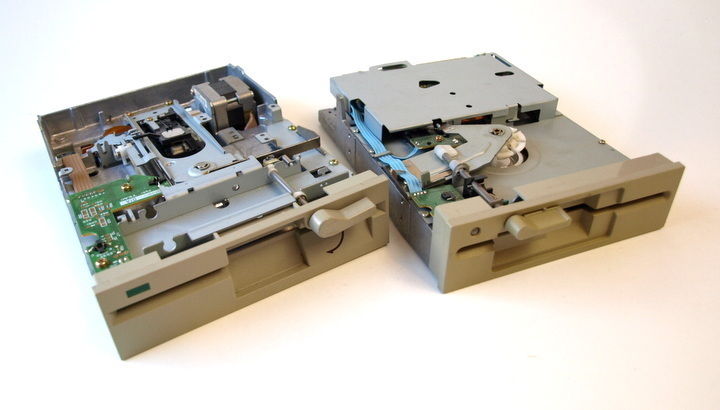

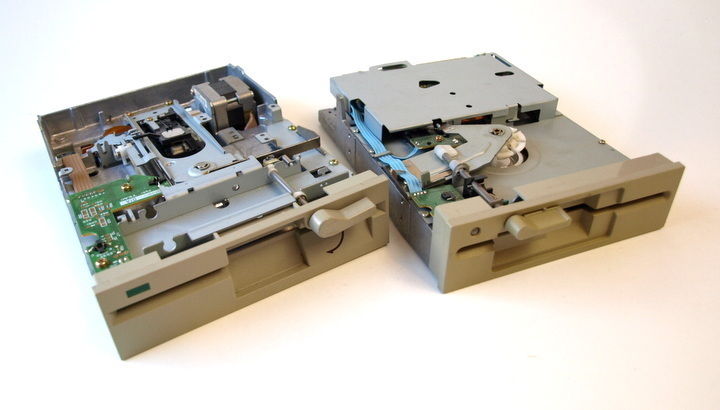

It is still possible to acquire, use, or otherwise work with the original floppy drives from the original hardware. Here’s a few for you to see how they look:

There are two sub-options with these original hardware drives – connect them to the original hardware and run programs to pull the data off (an example of this method is Apple Disk Transfer) or connect the drive to an intermediate piece of hardware designed for that kind of drive, to let it be hooked up to a modern system. (For example, the ZoomFloppy for Commodore 1541 floppies).

Let’s set that aside for the purposes of clarity. This option exists, but sourcing original drives is vaguely harder than sourcing general-purpose floppies made in the 1990s.

So let’s go to the third option: Repurposed General-Purpose Floppy Drive.

There are a lot of these out there – at least, a lot more of them were made than the other vintage hardware. They were commodity, getting shoved into a lot of generic boxes and low-cost servers and bargain-basement discount computers and electronics stores. Sometimes they were built well and sometimes they were not built well.

They pretty much all share one fatal flaw, hence this entry.

To make them run with modern systems, there’s a number of pieces of hardware out there that basically connect them via USB and let you run software to pull data off floppies.As a bonus, using these commodity drives and the right software/hardware will allow you to use them for a full range of floppy disk formats, such as Apple II, TRS-80, Commodore 64, Atari 400/800, IBM DOS, and so on. In some cases, you can just pull in a raw “disk image” (which will be very large) if the format is proprietary or there’s aspects we want to save for later study. It’s a generally good situation.

Among the floppy drive-to-USB hardware out there, there is the FC5025, Kryoflux, and DiscFerret.

So, this sounds almost perfect, really – just get stacks of floppy disks, put them into these different solutions, pull out the disk images, and we’re golden. And for many, many thousands of disks out there, this has been done for nearly 20 years. It’s great.

But.

It used to be, in ye olde days, that it was possible to use floppy disks a different way. Quick explanation.

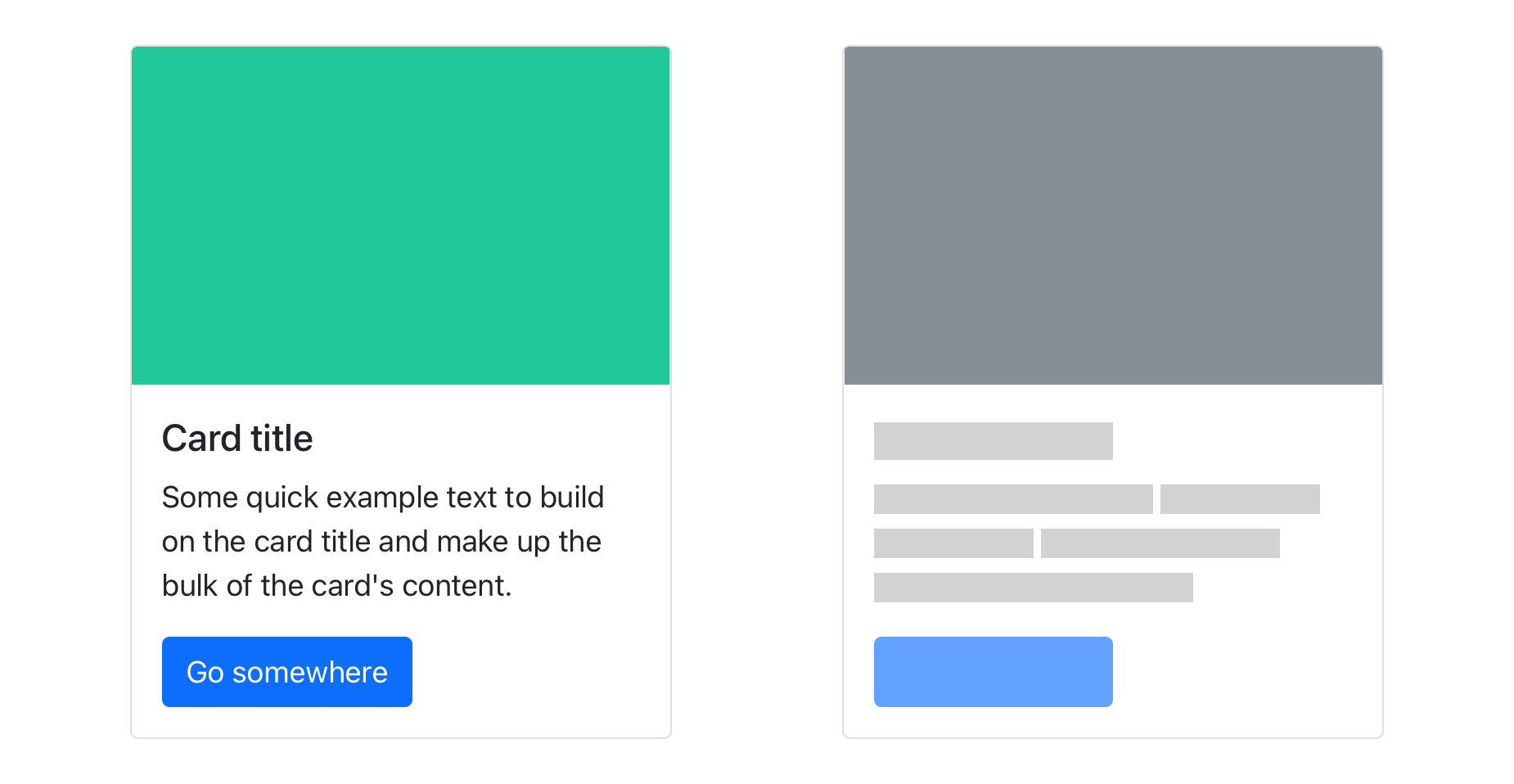

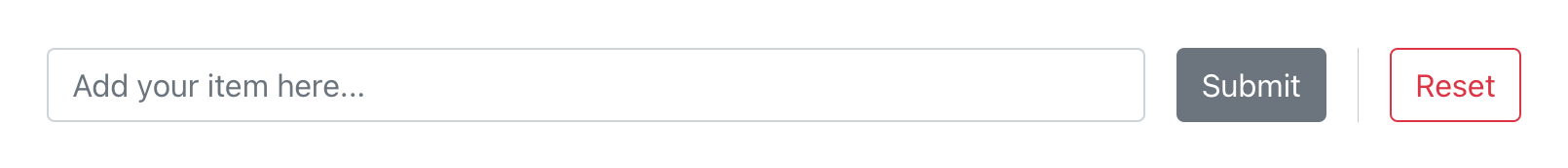

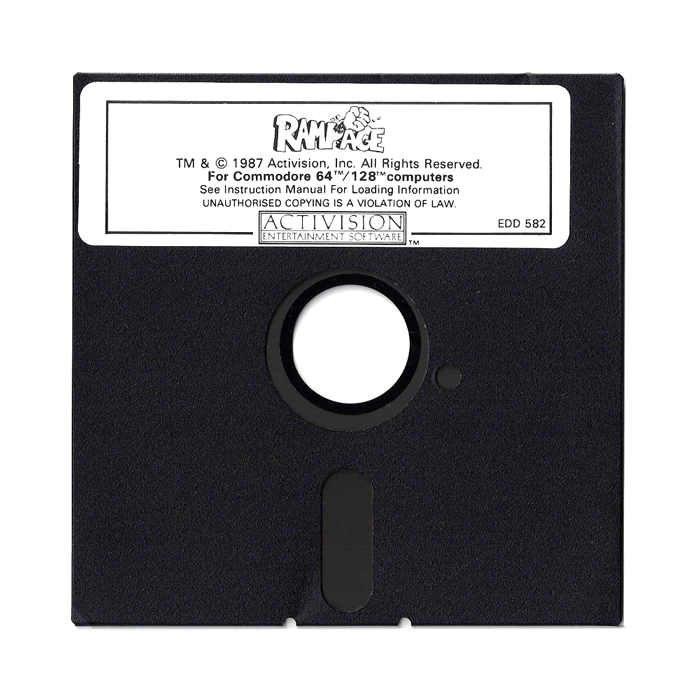

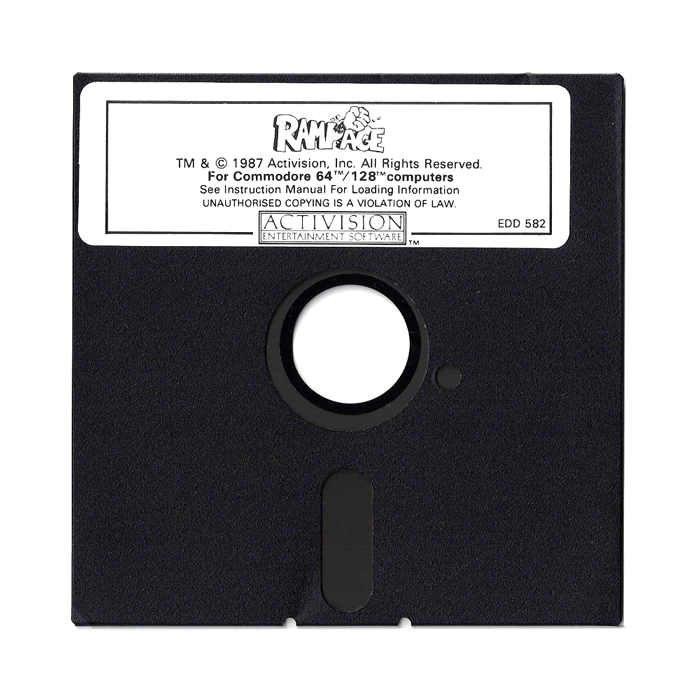

Floppy disks look like this:

The disk goes into the floppy drive with the little oval “window” on the bottom going in first. You then clamp down on the floppy by closing the drive door.

The disk goes into the floppy drive with the little oval “window” on the bottom going in first. You then clamp down on the floppy by closing the drive door.

Inside, the floppy drive has a number of indications about the disk coming from the disk shape itself. Specifically, there’s that notch in the upper right of the image, and there’s that tiny, tiny circle to the left of the big white circle in the center.

The notch on the upper right means “can the disk drive write to this floppy”. If there’s a notch, the answer was/is “yes”. If there’s no notch, the answer was “no”. It was possible to buy little stickers (yes, little stickers) that you would put over the notch to say “don’t write on this anymore”, and those stickers could be removed to say “go ahead, write over this”.

When commercial copies were made, they used drives modified to ignore the notch. So you could have a floppy with NO notch on it, meaning “never write on this disk”, with data on it put there by a modified drive. This is why if you see a commercial floppy disk from the time, like this one:

…there’s no notch, protecting the data inside from you accidentally writing over the poor thing during some late night of floppy switching.

Without going too much into variations, floppy disks were either single-sided, or double-sided. In some cases, there were floppy drives you could put the floppy disk into and it would read both sides. In most cases for early 1980s stuff, that’s not the case.

So if a disk was double-sided, it had notches on both sides of the disk. Here’s what that looks like:

So, if you look at this floppy closer, you’ll also notice it has not one, but two holes to either side of the big white circle in the center. That’s the issue, that’s the rub.

While these commodity new floppy drives do a lot of things, they don’t handle a disk that can be turned upside down and inserted very well. These two-sided floppies are known colloquially as “flippy disks”.

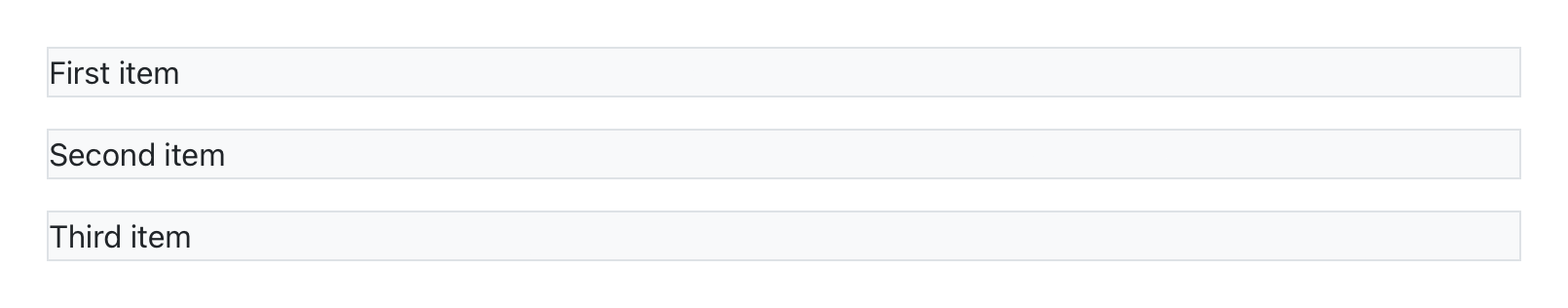

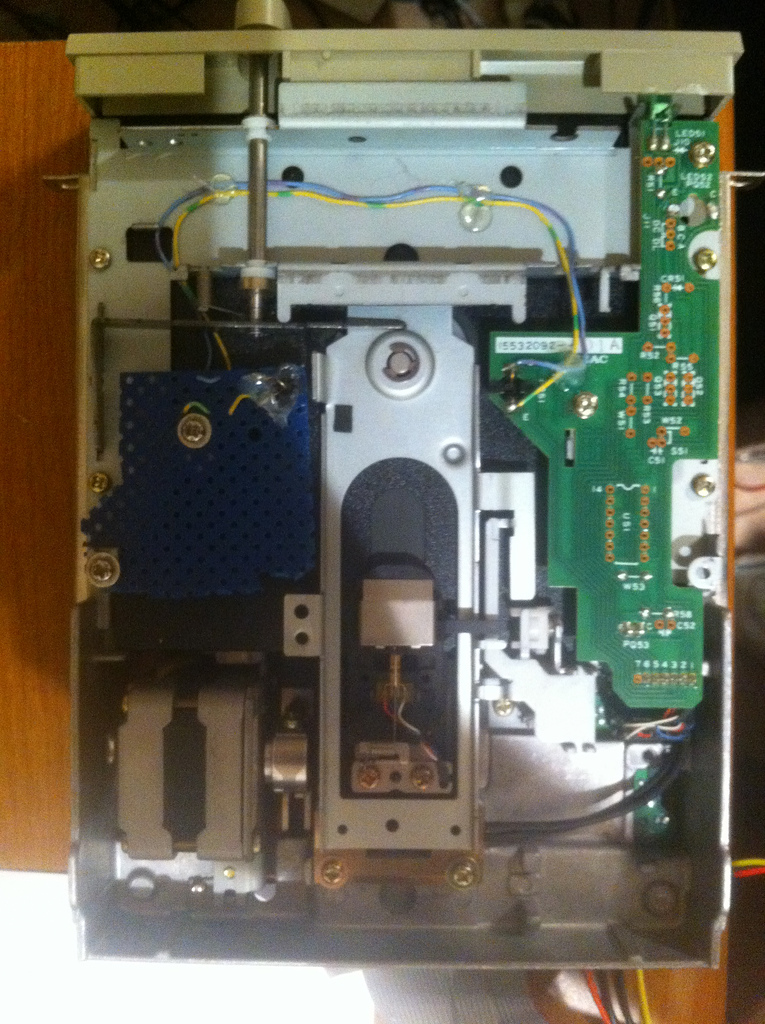

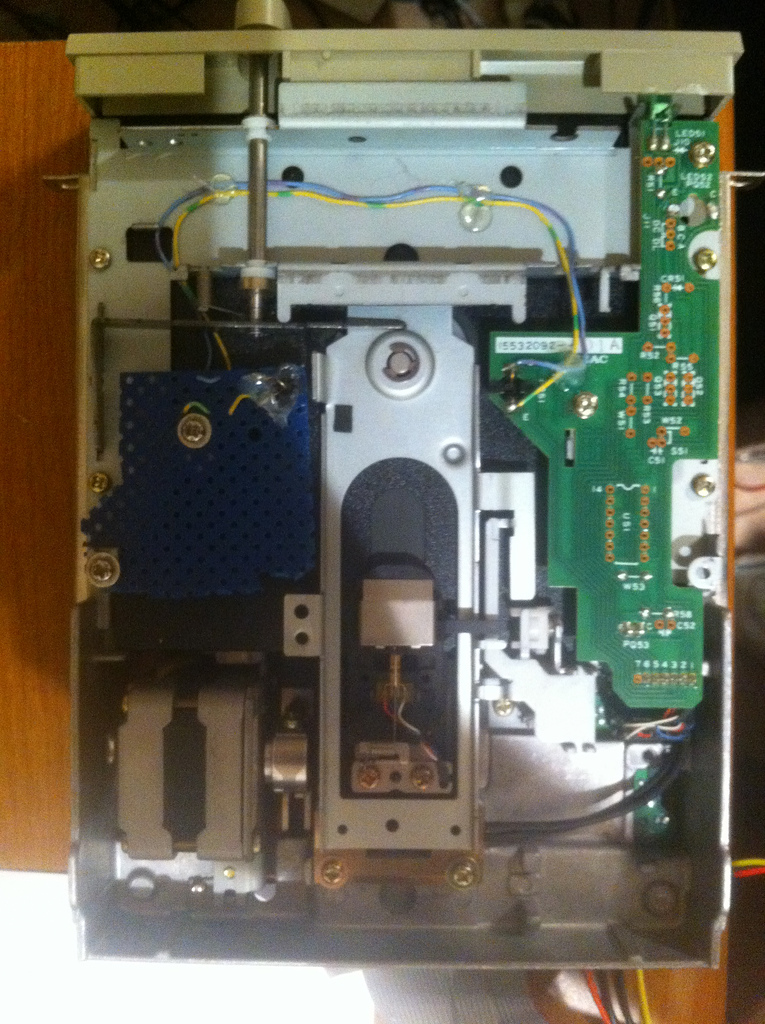

Therefore, these newer commodity floppy drives need to be modified.

Modification is a pain in the ass, summarized by this image:

Therefore, for most people, buying a flippy disk or using original hardware will be a good choice. Otherwise, you will only be able to save the images of floppies that use a single side.

If you know the entire collection is one-sided, then that’s fine. But many aren’t. Luckily, many collections tend to be of a type, so if you find a stack of old DOS floppies in need of transfer, and one works, many might work. It’s not a perfect situation, but you’re now armed with a little more insight as to what’s going on.

I realize this entry is a mash-up of really basic knowledge and really obscure, specific knowledge, but I wanted it all in one place for people to understand what’s going on. One of the biggest tropes in the vintage community is mentioning, sneeringly, this specific flippy disk problem as why we can’t have Regular People doing disk imaging, and we are well past the point that it can be assumed Regular People will want to venture and root around for the right people to talk to and the right hardware to buy without being given some idea of what they’re getting into.

You’re getting into buying a drive and a USB adapter. If your disks have two sides as described above, you are buying a flippy drive or having a drive converted to flippy. That’s it.

Your disk images have a welcome home at the Internet Archive. I will help you put them there. Your questions have a welcome home with me as well.

Enjoy.