strangeattractor

Shared posts

this day in Beatlemania

http://blog.oup.com/2013/08/beatles-she-loves-you-23-august-1963/

The choice of the words “yeah, yeah, yeah” also carried an obvious coded ideological meaning for younger fans. When the songwriters returned to McCartney’s Liverpool home the day after Newcastle and played their new creation for his father, he complained about the distinctly American flavor of the language, instead preferring “yes, yes, yes.” In a context where the Beatles’ primary audience (teens) sought to distinguish themselves from their parents and their parents’ generation, the simple use of language could prove a subtle and effective marker. “Yeah, yeah, yeah” evoked both rebellion and an innocence of teen infatuation that parents might protest, but could not ban, especially coming as it did in the context of a song. They might correct their children’s speech, but the words to a song were a kind of excusable poetic extravagance. --Gordon R. Thompson

...huh. who knew?

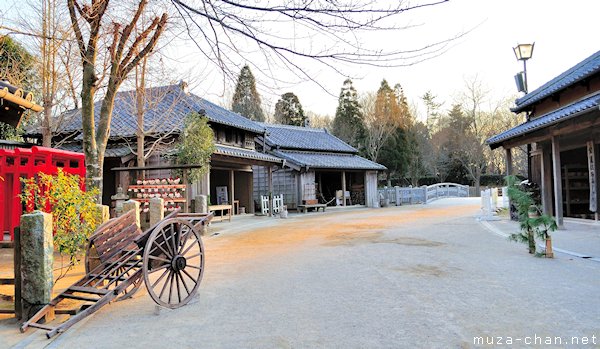

Japanese Edo village

The first open-air museum in Japan was opened in 1956 in Toyonaka city, Osaka: the Open-Air Museum of Old Japanese Farm Houses. Since then, several other museums appeared, showcasing region specific buildings.

So far, my favorite traditional Japanese buildings are those from the Edo Period and one of the most important museums presenting them is Boso-no-Mura, located in the Sakae town, Chiba: it presents about 30 buildings, including samurai residences, merchant houses, farmhouses, even a kabuki stage and a water mill.

Here’s the main street, photographed in the light of the evening, with a couple of workshops and the red gates of the Inari shrine.

Click on photo for higher resolution:

Boso no Mura Open Air Museum, Chiba

EXIF Info:

|

Yesterday’s Japan Photo: Meiji Jingu Shinto wedding procession

Japanese garden aesthetic principles, Asymmetry

The third part of the “Japanese garden aesthetic principles” series of articles

There is one principle common to all Japanese gardens: the asymmetry. And the best example is the Zen type garden, because it is meant to be admired as a whole. More than this, the imperfection is very important to the Zen philosophy and like with the broken symmetry of the Ensō Zen circle, the Japanese garden beauty is created through asymmetry…

Click on photo for higher resolution:

Moss covered Japanese Zen Garden, Ryogin-tei, Ryogen-in Temple, Kyoto

EXIF Info:

|

Yesterday’s Japan Photo: Japanese traditional architecture, Irimoya-zukuri

How to unfuck performance reviews

In most companies, performance reviews are a ridiculous process that does orders of magnitude more harm than it does good. If they’re an inconsequential formality, they waste everyone’s time. If they actually matter, they become touch-points for horse-trading and political activity that has nothing to do with work, instead creating enmities that divide the organization– managers vs. reports, managers vs. other managers, et cetera– and demolish efficiency. Good managers often ignore this “responsibility” by providing honest feedback verbally while putting nothing negative on paper (since doing so can cause a bilateral breakdown in loyalty) unless required to impose a forced distribution (i.e. some percentage must fail) on their employees, in which case the company just goes up in flames. Worst of all, performance reviews hinder internal mobility, because only people with extremely high scores are able to transfer, creating “warring departments” mentalities as team assignments become effectively permanent. (Those with good reviews want to keep getting promoted where they are; the rest are unwanted and can’t transfer.) Finally, review don’t work at their stated purpose, which is to punish the bad and reward the good. For the worst people– those who actively harm a team or company– one cannot afford to wait for an annual review to take action. The best people aren’t really motivated by reviews either– they want promotions, pay raises, and more autonomy, not mere confirmation that they “exceed expectations”. Give a top performer a rating of “exceeds expectations” with no improvement in pay, autonomy, or working conditions, and you’ll just piss her off.

If performance reviews are so terrible, then why do companies use them at all? My belief is that the architects of most of HR systems know that the best and worst performers can’t really be addressed through such bureaucratic systems. Reviews exist for the people in the middle, who are not in the running for promotion, but are basically competent and never going to do anything so wrong as to get themselves fired for cause. They still need, according to conventional HR theory, to be scared a little bit. The middling 90 percent are basically the forgotten children of an organization, and performance reviews are there to make them feel watched. Firing the “bottom” (often, the unluckiest) 5 percent is supposed to scare people into doing whatever they can to land above the blade, but what it actually does is make the environment needlessly more political. I’m not going to argue that this “scare the middle” approach works, but only that it is an existing motivation. It goes back to Jack Welch’s statement that “A players hire A players, B players hire C players”. B players are the competent but unexceptional people in the above-mentioned middle 90%; C players are the truly toxic ones who don’t get any work done, ruin morale, and can kill an organization. Yet another Welchian anxiety is around the idea that B players will become C players over time. The purpose (whether it succeeds would require another discussion) of the annual review is to prevent that.

This, all in all, is pretty fucked. Employees don’t like the intimidation angle; and good managers don’t like being on the other side of it, either. A manager who is honest and gives negative marks for poor performance will never garner real respect or loyalty from his reports, because he’s selling them out to HR. On the other hand, if a manager inflates grades on paper (which is the right thing to do, because it is unreasonable to demand loyalty without returning it; negative feedback should be private, verbal, and constructive) then he is rendering the whole process a waste of time. One might argue that positive reviews can help a good manager in supporting the people below him; the truth, however, is that good managers don’t need HR paper to support the people below them. Good managers in good companies can get resources, autonomy, and promotions for their people without having to write annual reviews.

One might think, then, that I’m suggesting that companies should do away with performance reviews entirely. To be honest, that would improve on what 90% (if not 99%) of companies already have. However, I think there is a way to preserve what little good there is in the process of performance reviews, which is to document a trajectory and present a case for promotion. The process needs to be revamped in a major way, however. Here’s how to do it: each person is reviewed at the next level. Instead of subjecting people to this humiliating reminder that they’re being watched for decline (from B into C-player status) there is a better goal to be sought, which is to try to convert some of those B-players into A-players. A fundamental problem with the HR way of thinking is that it assumes the worst of people, making progress (from a B- or even C-player status to A-player contribution) so far outside of its context that the only thing left is to watch for decline. But good organizations should be focused on making people better.

Here, I’m assuming (to start) a formal hierarchy or “ladder”. I’m not necessarily in support of that, but I’m assuming here that one exists. If someone is a Level 5 engineer, then he should only be reviewed for Level 6. It’s not part of his transfer packet, it doesn’t go on his record unless he wants it there. (I’m in favor of making work less like a prison, so putting things “on [someone's] HR file” doesn’t do it for me.) In other words, the purpose of the performance review is to answer the question: how far is she along to the next level?

See, this is a non-insulting way of handling performance assessment. People are assumed to be competent and “performing” at their jobs. (If they’re not, an annual review is far too late to work on that.) That’s not even to be on the table. Rather, the discussion centers on progress and the future, and whether a person is on track to get where he wants to be.

What if not everyone wants to be promoted in the same way? Or how would this work in a non-hierarchical corporation? Then it gets more interesting, and better. Each review cycle (which should be more often than annually, because if you’re going to do something like this, it should be done right) the person decides what he or she wants to be able to do, in the company, in the future; in the next cycle, the manager can assess whether that person’s efforts succeeded in taking him or her in the right direction. Reviews are in this context: whether the person is taking the right steps to get where he or she genuinely wants to go. If so, then things are running well. Good! If not, then it’s useful to discuss which efforts are leading the person in the desired direction, and which are less productive. This has managers acting more like talent agents than parole officers and, on the whole, I think that’s a major improvement.

National Trust Images

What I only recently realized is that they also have a whole site for images:

http://www.nationaltrustimages.org.uk/

And they're organized by keyword, so you can look up a specific property - but you could also search, say, "16th," and get back pages upon pages of details of 16th-c architecture: paneling, plasterwork, ceiling decorations, all sorts of things. It's actually a bit overwhelming, but I've been having fun with it, and think it could be a good resource - especially if you, like me, have difficulty with imagining what things looked like.

wow, that's terrifying

http://austenblog.com/2013/07/08/in-which-giant-colin-in-the-pond-moves-the-editrix-to-song/

Why would you. Just. Why.

*It's apparently some weird composite Darcy, so it doesn't really look like Colin Firth. (If you scroll down to the end of the post, you can read the press release for this nightmare. Which I use literally, as in, "if I saw this thing in real life, I'm pretty sure it would haunt my dreams.")

Stairway to Heaven

4 July 2013 – Cleveland, Ohio

by Eliza

During a trivia game a few years ago, I was asked what waterway bypasses Niagara Falls. The answer is the Welland Canal, a twenty six mile channel that winds from Lake Ontario up to Lake Erie. I knew the answer right away, for an atypical reason – I’ve gone through it. And a few days ago, I went through it again.

If you’ve been around the maritime industry for a year or two, you’ve probably heard of the Welland Canal. A series of eight locks operate as a floating stairway to lift and lower vessels over three hundred feet. Cargo vessels built halfway around the world are constructed to the dimensions of the Welland Canal locks. It takes seven to seventeen hours to get through the locks, primarily based on traffic, and often requires all hands on deck to manipulate docklines and fenders.

On Monday morning, the crews of Unicorn and Pride of Baltimore II woke shortly after five and got underway for Port Welland. The other boats would follow later that day. We collected every fender on board and lashed them over the sides. They would absorb the shock and protect the boat if we made contact with the lock walls. We then lashed newly created “Welly-boards” outboard of the fenders. These sacrificial chunks of lumber slide up the lock walls as the boat rises. Some tall ships even add a second layer of sacrificial wood, nicknamed “spuds”. If there is still a great deal of friction as the vessel grinds up the lock wall, a crew member may be sent to take the cook’s container of Crisco and be told to slather grease all over the fenders. Having accomplished this duty for Lynx, a Crisco-covered crewmember earned the nickname Crisco Man!

We reached the first lock around 0800 and were lucky to find a green light, signaling us to enter. The Captains took the helms and skillfully steered into a towering, cement box. One of the most remarkable features of the locks is their immense size. Only more remarkable is the size of the cargo vessels that traverse them. Lines were tossed down from the top of the lock wall, nearly forty feet above our heads. We hitched these lines to our sturdy docklines so that workers on the dock could haul our docklines up and loop them around bollards. Once we were secure, enormous wood and metal gates slammed shut behind us and water started pouring into the lock.

We had requested a slow fill but the turbulence in and beneath the water rocked the boat. At the Captain’s orders, deckhands aboard eased and took up slack in the docklines, enabling us to maintain our position as we quickly rose to dock level and cheering bystanders appeared through the chain link fences at the edge of the cement dock. Finally, the water settled. Ahead, the thick gates rumbled open and we glimpsed flashes of green grass and trees and murky, blue, canal water. Slipping off the dock and out of the lock, the crew breathed a sigh of relief and collapsed on the deckboxes, exhausted. One down, seven to go.

Author Interview: Sherwood Smith

INTERVIEWED by KATHARINE ELISKA KIMBRIEL

Q.)What drew you to Book View Cafe?

A.)I first became aware of BVC when the announcement went out that it was forming. A group for getting backlist into ebook? Oh, yeah, it was like it was made for me.

Except I wasn’t in it. Argh!

But within a year or so, in talking with members Judith Tarr and Deborah Ross, I found out how it worked. In those early days, you not only were expected to pitch in in some way to help the labor flow (and there is enormous labor flow) but to broadcast the “dowry”, which was a blurb written up for each new release.

The intent behind this “dowry” was good, because as everyone knows, a book no one knows about goes unread and unbought. And in those days (this makes it sound like decades ago, but it was just what, four years? Five?) anyway, Twitter was new, Facebook was exciting and fast paced and many swore by it as a PR tool.

Within a year or so after my joining, BVC was busy seriously reassessing. The “dowry” was jettisoned, as there was negative feedback about spamming the same PR message all over the social media, where PR blurbs were mushrooming faster than shoe fungus in an army on the march, and were thus about as welcome.

At the same time, BVC began bringing out original works. These were by members, as it was assumed that members were already professional level writers. But it soon became apparent that few of us are able to do our own editing, and especially copyediting and proofing. How to deal? We wanted books of quality for the readership who liked the target subgenre, and yet no one wanted an editorial board.

I was so glad to see that, because in my experience, fun groups that got together to critique or discuss writing would inevitably say, “Hey, why don’t we publish a magazine?” And that would be the beginning of the end, as political infighting determined who was going to be Queen Bee. BVC was successful because decisions were batted around until consensus was reached.

The decision was made to form a pool of members who had edited, to serve as beta readers. The author was still in the driver’s seat. But getting feedback, and then re-submitting the book to another pool for copyediting and proofing, meant that the books would get as much professional attention as most books published by the big six. Sometimes more.

At the same time, some very savvy members started looking hard at what kinds of cover art worked, and how to make it when you have a budget of $0.00 Some of the early covers (like mine, which I made myself) are stinkers, but they have since come to look professional and evocative.

Meanwhile, members were also busy with outreach, resulting in Book View Cafe’s catalog going out to libraries all over the world, and other exciting developments in the back room.

And yet members were still going to cons here in North America, gatherings, and contacting reviewers or whatever, and on mentioning Book View Cafe, got the blank look and the WHO?

There are two challenges for any publishing venture. One, production, which (let’s face it) is a protracted, painstaking job of work. Then there is getting the word out. If you do not have a PR budget, and you don’t want to be annoying people with tweets and twitters and Facebook blurb-bombs, how do you connect potential readers with the sorts of books they are looking for?

BVC is trying a lot of different things, seeing what works, what doesn’t. My own cherished theory is that content is king, but there is also the matter of style. I think to catch the attention of the constantly clicking reader one has to be interesting. Yeah, but how? We all want to be interesting to others, or we wouldn’t be in the field we’re in. So this is an ongoing process.

Q.) What titles can BVC readers expect to see from you?

A.) Two of my titles have become popular in a modest way, and they were fun to write. So first off I have coming up this summer, a fluffy and fun YA fantasy adventure with a romantic tinge, called Lhind the Thief. It should appeal to the readers who liked A Posse of Princesses.

Then I am writing a Napoleonic era romance for those who liked Danse de la Folie, which is an old-fashioned silver fork novel. Rondo Allegro begins on the continent, stops by Revolutionary France, and then goes north to England after Trafalgar.

Q.) With urban fantasy taking over more and more of the genre these days, how do you think epic fantasy will do in the long run?

A.) That is so hard to say! Judging by the vigorous sales as well as debate all over the internet, epic fantasy is back in fashion, perhaps stronger than ever. Readers are passionate about epic fantasy, from the postmodern “grimdark” to the old-fashioned quest tale built around a hero who becomes king, which I think hearkens back to the centuries-old seduction of competence and dash. (Look up the history of words like panache and sprezzatura.)

Book View Cafe offers those, too.

Identifying Pain is the First Step in a Sales Process – Here’s How

This article initially appeared on Inc. If you haven’t already followed me on Twitter, that’s the fastest way to get blog updates. Click here.

In my first enterprise software company we developed a methodology for sales that we called PUCCKA.

This post is about the “P” or pain.

This post is about the “P” or pain.

The point of PUCCKA was to develop a common methodology to make sure our whole team approaches sales with the same mindset and to give us a language to talk with each other about our prospects, as in, “have you identified your customers pain point yet?”

Having a methodology instead of just going on random sales visits helped force a bit of rigor and honesty amongst team members about how well or not we thought we were doing.

Pain.

It’s a reminder that unless your prospect has a need to solve a problem they are not going to buy a product. Customers sometimes buy things spontaneously without thinking through what their actual need is. But often there is an underlying reason for a purchase even if the buyer doesn’t bring it to the surface.

Take for example the years 2010-2012 where every brand out there seemed to be buying Facebook “Likes.” In truth many companies had no idea why they actually needed Facebook Likes but there was still a pain point. The pain was that somebody senior in the organization had read about the importance of Facebook for business and had begun asking loud questions about why the organization didn’t have a strong Facebook presence.

That is still “pain.” It’s a reason a company would buy. That a boss is a dolt with no economic rationale for what he is asking to be achieved does not disqualify pain. Just watch Mad Men and you’ll know that.

Pain.

Too many sales reps walk into customer meetings with their pre-canned sales decks and proudly squawk through 30 of their favorite slides without engaging the customer in a discussion.

The reason they do this is that it’s far easier to go through talking points you’ve said 100 times than to engage the customer in a dialog about their business challenges.

I call these people crocodile sales people – small ears and a big mouth.

It is not effective because while you leave the meeting feeling great about yourself you really don’t have any further knowledge of the customers “pain.”

I call this sales approach “tell & sell” and I don’t recommend it.

The best sales meetings are discussions. The goal is to get the customer speaking about their organization. And the best kind of questions to ask are open-ended questions.

I’ve also seen the converse too many times – sales reps who walk into a meeting and spout out, “so, tell us what’s not working in your manufacturing process!”

I hate when people do this to me. My first thought is, “You asked for the meeting – why am I going to give you a bunch of ammunition to sell to me?”

There is an art to teasing out pain points.

I recommend starting with a brief overview of you, your company and your solution. And by brief I mean BRIEF! You’d be amazed at how long some people rattle off their life stories in an introduction. Nobody wants to hear your life story other than your mom.

After a brief overview of you, your company and your solution I recommend putting up some example clients you’ve worked with, although you obviously need their approval first.

These references make for great discussions with customers. If you have enough references in your arsenal you obviously want to pick out ones that you believe will resonate with your prospect due to job function or industry.

And then there’s the key transition slide, which I call “What We Find” (WWF) or some variation of this.

WWF gives you the ability to tease out the problem having just shown similar cases where customers have this problem.

“What we find is that many of our customers have been accumulating Facebook Likes because they thought they were supposed to. Now they have a few thousand Likes but haven’t been able to figure out whether this is improving their bottom line. They don’t have a way to measure the effectiveness of a Like.”

“Do you see that at all inside your department? Have you found a way to best link your potential marketing leads in social media into activity that leads to more business?”

Often if a customer has heard similar problems described in other customers (not hearing your solution pitched at them but a real business discussion about the pain point) then they will start to open up and have a discussion.

Even if they start to debate with you whether this is a real problem or not, you’re having a much better meeting then just flipping through slides. If they’re going to take the time, energy and logic to try and debate with you then they’re at least engaged.

People prefer to hear themselves speak rather than to listen to you. It’s just human nature.

So throughout the meeting your job is to tease out as many discrete pain points that are near enough to your solution set to begin talking about what it is that you do.

Write down the customer pains so you’ll have them for later. Ask questions the whole time. The best form of sales is “active listening” where you’re engaged in what the customer is telling you.

And please resist the temptation to cut off the customer with a story of your own.

You know, the blah, blah, blah I heard you but now let ME tell you this great story I have. Most people naturally do this at cocktail parties (everybody does) but not in sales meetings. Never. When you cut off customers with your stories you lose valuable insights that might be exposing more pain points.

Open questions equals a treasure trove of information to mine for pain points.

Show your knowledge and charm through great questions not great anecdotes.

In many ways it’s more enjoyable to learn about other people than it is to spout BS about your company or products.

In the words of Dale Carnegie,

“You can make more friends in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you.”

Or in words that I first heard from one of the greatest sales gurus of all time, Zig Ziglar

“People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care”

Apparently Zig got that from Theodore Roosevelt if the Internet is to be trusted.

But it is so true. I think every big sale I have had in life came because I genuinely cared about the person buying from me. In many ways, the “sale” made me feel more committed in my role at the company because I felt a huge sense of obligation to live up to the expectations the buyer had entrusted in me.

Ask more. Listen more. Care more. Problem solve. Good things will come.

Thank you to Jeff Hughes for reminding me of the Ziglar quote.

Summary

If you get your prospects talking about problems you’ve solved the first step of sales, “Why Buy Anything?”

Frankly if you can’t sit with prospects and tease out pain points then you ought to be working in a different department than sales or executive leadership.

Everybody has pain points – believe me.

And once you manage to tease out some problems you can then begin to pivot the meeting importantly to your solution and how it may solve their problem.

But that’s the next post, “Unique Selling Proposition” or USPs.

Dead Star Barn

“Why are barns red?” is, apparently, the all-time most popular FAQ at The Barn Journal (sadly, no word on what the second most popular might be).

A few years ago, design writer Steven Heller dedicated his column in Print magazine to this question. It has also been bothering the Chief Architect of Google+, Yonatan Zunger, who published his investigation of the phenomenon yesterday, in a post poetically titled, “How the price of paint is set in the hearts of dying stars.”

Their answers are interesting, and different.

Heller draws on Eric Sloane’s American Barns and Covered Bridges, which explains that until the late eighteenth-century, builders carefully considered a site’s wind, sun, and water exposure in order to position bridges and barns in such a way that the weather would treat the wood:

The right wood in the right place, it was discovered, needed no paint.

By the end of the 1700s, however, farmers began to paint their barns, as “the art of wood seasoning gave way to the art of artificial preservation.” Virginia farmers were, apparently, “the first to become paint-conscious,” although no explanation is given for this shift. Heller does, however, attribute the rise of red, specifically, to both function and fashion.

The red colour came from the addition of iron oxide, which is abundant in the soils of the eastern United States, and is equipped with anti-fungal properties (dissolved rust is still used as a DIY anti-moss treatment today). This new-and-improved red barn gradually superseded its unpainted wooden predecessor, becoming the norm.

Heller concludes, somewhat unconvincingly, that having a nice red barn was also an aesthetic choice, as it “became a fashionable thing that contrasted well with traditional white farmhouses.”

Zunger, on the other hand, starts from the premise that barns are red because red paint is the cheapest. This is certainly not the case anymore — a gallon of barn or fence paint from FarmPaint.com costs $8.95, whether it is grey, green, white, brown, or “traditional barn red.”

IMAGE: Barn paint colours available from AgSpecialty.com

However, red was the cheapest paint, once. According to an article by preservationist Robert Foley (PDF), red was the ubiquitous colour of eighteenth century England and colonial America, produced by mixing iron-oxide rich milled earth with linseed oil and turpentine. The result was called “Spanish Brown,” and, because the precise mineral content of the soil determined the final colour, it could range “from burnt orange through reds and into browns” — “the exact shade didn’t seem to matter, cost did.” Other pigments, such as white lead or verdigris green, required an extensive manufacturing process before they could be mixed with linseed oil and used; dirt could just be dug up and ground.

Zunger is not content to leave matters there, however. Instead, he dives deep into the physics of exploding stars to explain precisely why iron is so abundant in the Earth’s crust, and why ferrous oxide reflects a wavelength of light that is visible to human eyes.

Things get pretty technical, but, in short, “it’s because of the details of nuclear fusion — the particular size at which nuclei stop producing energy — that iron is the most common element heavier than neon.” If you also factor in the temperature of our Sun (and any star stable and long-lasting enough to sustain planets with life on them) as well as the speed at which the outermost electrons in the iron atom spin, Zunger concludes, “iron is going to be, by far, the most plentiful pigment for any species which lives on [sic] a star that isn’t about to blow up.”

Furthermore, in a detail that Zunger actually doesn’t mention, about 2.45 billion years years ago, for reasons scientists don’t fully understand but that seem to be tied to the evolution of photosynthetic cyanobacteria, the Earth experienced something called the “Great Oxidation Event.” Prior to that, oxygen was nearly absent in the atmosphere of early Earth; after that, the iron in ancient soils turned into rust.

So, to sum up: many barns are painted red because paint protects the wood against weathering; because the pigment that went into red (or, more accurately, “Spanish Brown”) paint was the cheapest available two centuries ago, due to the abundance of iron oxide in the soil (due to nuclear physics and blue-green algae) and its ease of preparation for use; and because, despite the fact that green is as cheap as red today, humans tend to display a preference for the familiar.

IMAGE: A white barn photographed by Nyttend, via Wikipedia.

Of course, some barns are white. Whitewash, a mixture of chalk, lime, and water, was also cheap — even cheaper than Spanish Brown in areas with iron-poor soils but readily available limestone deposits left by ancient marine life — and possessed of both antimicrobial properties and sanitary connotations.

IMAGE: The green Sears barn in Newark Valley, NY, via The Barn Journal. It was originally painted yellow.

And some barns are green, but there is no accounting for taste.

The field guide to my annotations in a draft

I tend not to stop when I’m writing a draft, unless it’s for something really vital (for instance, the precise headdress that someone is wearing is something I can always work out later; the layout of the rooms where the nobleman was murdered and that my characters are searching is rather more vital to the way the scene plays out, and requires me to have actually done the research/invention/work). Accordingly, my first (and subsequent) drafts are peppered with little notes to myself, that I generally smooth out in the next revision.

I stole a leaf from a friend’s book, who marks such places in his manuscripts with @; except I upgraded to square brackets because 1. there’s less risk of me accidentally using them in anything, and 2. Square brackets enable me to see the beginning and the end of my own annotations.

(cut for length)

Here’s a an example from my latest WIP:

The view zoomed out; a thin line of green threaded its way through the debris–a zigzag course through some of the less cluttered areas [MB]. “My best guess,” The Dragons in the Peach Gardens said.

“That’s assuming they’ll take the obvious path,” Sixth Aunt said, her eyes still on the map.

“Security reasons?” Thuy asked. “They’ll assume there isn’t a ship that can touch them; and ordinarily they’d be right.” She stared at the map again, willing the truth to emerge from the jumble of debris–but the only truth that would come was the same Chi already knew; that nothing was fair or [?] in life.

“What would you do if you were Chi?” Sixth Aunt asked.

Thuy shook her head. “I can’t tell what she would do. Not anymore.”

Sixth Aunt said nothing. Chi had stayed a while, after the accident; and she’d tried, for a while, to act normal; to pay her respects every morning to her elders; to [special attention to Sixth Aunt]; to pretend that everything was fine. But the change that had come over her–the magnitude of what had happened to her while she’d hung alone in the carcass of the ship with her spacesuit’s thrusters disabled–was like a wound in the family’s everyday life; like a swarm-mine sending shards and shrapnel [R?] long after it had detonated–like smart bullets still worming their way through a body, years and years after the impact.

[MB]

[WW]: wrong word, pick another one

[?]: missing word

[MB]: missing bit (generally a large bit: portions of a sentence or entire paragraphs).

[R]: repetition, find another word

[retcon]: self-explanatory

[blech]: also self-explanatory ![]()

And any longer chunks of text, of course, if I need to put in more details between the square brackets.

You’ll notice that there are large chunks of things that I’m missing (for instance, a sentence where I’m a bit unsure what peculiar attention Chi would have had for Sixth Aunt, or entire paragraphs near the end); but I also put in the square brackets when it’s just a question of flow (the lone [?] in the third paragraph): I’d rather save the space for one or two missing words while I’m still in said flow, than have to reread the entire text and work out where my rhythm slipped.

And here’s the cleaned-up version:

The view zoomed out; a thin line of green threaded its way through the debris–a zigzag course through some of the less cluttered areas. “My best guess,” The Dragons in the Peach Garden said.

“That’s assuming they’ll take the obvious path,” Sixth Aunt said, her eyes still on the map.

“Security reasons?” Thuy asked. “They’ll assume there isn’t a ship that can touch them; and ordinarily they’d be right.” She stared at the map again, willing the truth to emerge from the jumble of debris–but the only truth that would come was the same Chi already knew; that nothing was fair or equitable in life.

“What would you do if you were Chi?” Sixth Aunt asked.

Thuy shook her head. “I can’t tell what she would do. Not anymore.”

Sixth Aunt said nothing. Chi had stayed a while, after the accident; and she’d tried, for a while, to act normal; to pay her respects every morning to her other elders; to bring fruit fresh from the orchard to Sixth Aunt; to pretend that everything was fine. But the change that had come over her–the magnitude of what had happened to her while she’d hung alone in the carcass of the ship with her spacesuit’s thrusters disabled–was like a wound in the family’s everyday life; like a swarm-mine ejecting shards long after it had detonated–like smart bullets still worming their way through a body, years and years after the impact.

The parts. Thuy blinked, and said aloud, “Can you tell me what the parts would be used for?”

Notice that there’s stuff I did indeed fix and bits I added, but there’s also places where I decided it wasn’t worth it to add to the existing sentences (also, I write relatively clean drafts; I tend to have a really messy brainstorming process and to only commit words after I’m reasonably sure ).

What about you? Do you note where you need to add bits in a draft? Do you use Word comments or some other process?