Some argue that the increasing wealth-to-income ratios observed in many advanced economies are determined by housing and capital gains. This column considers the growing wealth-to-income ratio in an economy where capital and labour are used in two sectors: construction and manufacturing. If productivity in manufacturing grows faster than in construction – a ‘housing cost disease’ – it has adverse effects on social welfare. Concretely, the higher the appreciation of the value of housing, the lower the welfare benefit of a rising labour efficiency in manufacturing.

allendd

Shared posts

Phone and laptop encryption guide: Protect your stuff and yourself

The worst thing about having a phone or laptop stolen isn’t necessarily the loss of the physical object itself, though there’s no question that that part sucks. It’s the amount of damage control you have to do afterward. Calling your phone company to get SIMs deactivated, changing all of your account passwords, and maybe even canceling credit cards are all good ideas, and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

Using strong PINs or passwords and various Find My Phone features is a good place to start if you’d like to limit the amount of cleanup you need to do, but in this day and age it’s a good idea to encrypt your device’s local storage if at all possible. Full-disk or full-device encryption (that is, encrypting everything on your drive, rather than a specific folder or user profile) isn’t yet a default feature across the board, but most of the major desktop and mobile OSes support it in some fashion. In case you’ve never considered it before, here’s what you need to know.

Why encrypt?

Even if you normally protect your user account with a decent password, that doesn’t truly protect your data if someone decides to swipe your device. For many computers, the drive can simply be removed and plugged into another system, or the computer can be booted from an external drive and the data can be copied to that drive. Android phones and tablets can be booted into recovery mode and many of the files on the user partition can be accessed with freely available debug tools. And even if you totally wipe your drive, disk recovery software may still be able to read old files.

Read 29 remaining paragraphs | Comments

How weak regulation is helping to build corporate kingdoms in America

"IF WE will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessaries of life." So said Senator John Sherman, who proposed the first American law against monopolies in 1890. Merging firms, however, argue that they will rule benevolently and lower prices. They claim that savings made from combining their efforts will be passed on to customers. The problem for regulators is that it is difficult to tell how much firms are fibbing. Prices can change for many reasons—higher costs, tariff changes, consumers’ tastes—and a price rise after a merger might not directly be the result of price fixing by a newly crowned monopoly.

A new paper published earlier this summer in the RAND Journal of Economics tests whether regulators made the right call in the American beer industry. The paper looks at the 2008 merger of Miller and Coors, the second and third largest brewers at the time in the United States. Miller and Coors argued that a merger would combine their distribution networks, thus reducing transportation costs. Regulators worried that the merger would...Continue reading

Innovation, income inequality, and social mobility

In recent decades, there has been an accelerated increase in top income inequality, particularly in developed countries. This column argues that innovation partly accounts for the surge in top income inequality and fosters social mobility. In particular, the positive effect of innovation on social mobility is due to new innovators.

The half-life of happiness

Does material wealth make you happier? Recent literature and public discussion suggests that we believe widely that, in the long term, it doesn’t; especially if you are fairly wealthy and live in the West. But what if you’re poor and live in a developing country? This column presents new evidence that taking material improvements for granted is a common human behaviour that is present even among the extremely poor.

Red Star Linux Adds Secret Watermarks To Files

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

US intergenerational mobility since WWII

Intergenerational mobility – the ability of less-advantaged children to achieve economic success – is held in high regard across the political spectrum in the US and other industrialised countries. But not much is known about its history. This column presents a new method that allows intergenerational measurement further back in time, as well as across more places and demographic groups. One firm result shows a large increase in intergenerational mobility after 1940 in the US South and among African Americans.

Why growth in finance is a drag on the real economy

A booming financial sector means economic growth. Or does it? This column presents new evidence showing that when the financial sector grows more quickly, productivity tends to grow disproportionately slower in industries with either lower asset tangibility or in industries with higher research and development intensity. It turns out that financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing.

The corporate debt bias and the cost of banking crises

Strengthening the banking sector through higher equity capital is one of the key elements of policies aiming to reduce the probability of crises. However, the ‘corporate debt bias’ – the tendency of corporate tax systems to favour debt over equity – is at odds with this objective. This column estimates the benefits for financial stability of eliminating the corporate debt bias. Fully removing the debt bias is estimated to reduce potential public finance losses by between 25 and 55% for the six large EU countries sampled.

The meaning of a referendum: Austerity and sovereignty

Two financial crises at the ‘sub federal’ are currently taking place – one in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the second one in Greece. This column highlights some surprising similarities between them, as well as the main differences. The Eurozone is a voluntary union of states which remain sovereign. But if Greece were part of the US, it could not hold a referendum, and its budget would be drawn up by a federal bankruptcy court. The key political difference is not austerity, but the fact that Greece’s debt is mainly to official creditors, who are ideal targets for political pressure.

Stock prices and high-frequency news analytics

High-frequency news analytics can increase market efficiency by allowing traders to react faster to new information. One concern about such services is that they might provide a competitive advantage to their users with potential distortionary price effects. This column looks at how high frequency news analytics affect the stock market, net of the informational content that they provide. News analytics improve price efficiency, but at the cost of reducing liquidity and with potentially distortionary price effects.

Cross-border acquisitions and labour regulations

Labour market regulations have important implications for both the incidence of cross-border acquisitions, and the outcomes for acquiring firms. This column explores how variations in labour regulations between countries affect cross-border acquisitions and subsequent firm performance. For a sample of 50 countries, firms are found to enjoy larger returns when they acquire a target in a country with weaker labour regulations than the acquirer’s home country.

“Bonus Culture: Competitive Pay, Screening and Multitasking,” R. Benabou & J. Tirole (2014)

Empirically, bonus pay as a component of overall renumeration has become more common over time, especially in highly competitive industries which involve high levels of human capital; think of something like management of Fortune 500 firms, where the managers now have their salary determined globally rather than locally. This doesn’t strike most economists as a bad thing at first glance: as long as we are measuring productivity correctly, workers who are compensated based on their actual output will both exert the right amount of effort and have the incentive to improve their human capital.

In an intriguing new theoretical paper, however, Benabou and Tirole point out that many jobs involve multitasking, where workers can take hard-to-measure actions for intrinsic reasons (e.g., I put effort into teaching because I intrinsically care, not because academic promotion really hinges on being a good teacher) or take easy-to-measure actions for which there might be some kind of bonus pay. Many jobs also involve screening: I don’t know who is high quality and who is low quality, and although I would optimally pay people a bonus exactly equal to their cost of effort, I am unable to do so since I don’t know what that cost is. Multitasking and worker screening interact among competitive firms in a really interesting way, since how other firms incentivize their workers affects how workers will respond to my contract offers. Benabou and Tirole show that this interaction means that more competition in a sector, especially when there is a big gap between the quality of different workers, can actually harm social welfare even in the absence of any other sort of externality.

Here is the intuition. For multitasking reasons, when different things workers can do are substitutes, I don’t want to give big bonus payments for the observable output, since if I do the worker will put in too little effort on the intrinsically valuable task: if you pay a trader big bonuses for financial returns, she will not put as much effort into ensuring all the laws and regulations are followed. If there are other finance firms, though, they will make it known that, hey, we pay huge bonuses for high returns. As a result, workers will sort, with all of the high quality traders will move to the high bonus firm, leaving only the low quality traders at the firm with low bonuses. Bonuses are used not only to motivate workers, but also to differentially attract high quality workers when quality is otherwise tough to observe. There is a tradeoff, then: you can either have only low productivity workers but get the balance between hard-to-measure tasks and easy-to-measure tasks right, or you can retain some high quality workers with large bonuses that make those workers exert too little effort on hard-to-measure tasks. When the latter is more profitable, all firms inefficiently begin offering large, effort-distorting bonuses, something they wouldn’t do if they didn’t have to compete for workers.

How can we fix things? One easy method is with a bonus cap: if the bonus is capped at the monopsony optimal bonus, then no one can try to screen high quality workers away from other firms with a higher bonus. This isn’t as good as it sounds, however, because there are other ways to screen high quality workers (such as offering lower clawbacks if things go wrong) which introduce even worse distortions, hence bonus caps may simply cause less efficient methods to perform the same screening and same overincentivization of the easy-to-measure output.

When the individual rationality or incentive compatibility constraints in a mechanism design problem are determined in equilibrium, based on the mechanisms chosen by other firms, we sometimes called this a “competing mechanism”. It seems to me that there are quite a number of open questions concerning how to make these sorts of problems tractable; a talented young theorist looking for a fun summer project might find it profitable to investigate this as-yet small literature.

Beyond the theoretical result on screening plus multitasking, Tirole and Benabou also show that their results hold for market competition more general than just perfect competition versus monopsony. They do this through a generalized version of the Hotelling line which appears to have some nice analytic properties, at least compared to the usual search-theoretic models which you might want to use when discussing imperfect labor market competition.

Final copy (RePEc IDEAS version), forthcoming in the JPE.

'Prisonized' Neighborhoods Make Recidivism More Likely

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Forbidden Fruits: The Political Economy of Science, Religion, and Growth

History offers many examples of the recurring tensions between science and organized religion, but as part of the paper’s motivating evidence we also uncover a new fact: in both international and cross-state U.S. data, there is a significant and robust negative relationship between religiosity and patents per capita. Three long-term outcomes emerge. First, a "Secularization" or "Western-European" regime with declining religiosity, unimpeded science, a passive Church and high levels of taxes and transfers. Second, a "Theocratic" regime with knowledge stagnation, extreme religiosity with no modernization effort, and high public spending on religious public goods. In-between is a third, "American" regime that generally (not always) combines scientific progress and stable religiosity within a range where religious institutions engage in doctrinal adaptation.

Can High Intelligence Be a Burden Rather Than a Boon?

allenddThought of from an evolutionary perspective, this also helps explain why we're not all always getting smarter as a species.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Economic consequences of gender identity

The reduction in the gender gap in labour market outcomes has stalled. Recent research suggests that gender identity might be one of the culprits. This column provides new evidence on the issue using US census data. The results indicate that the prescription that women should earn less than men plays a role in marriage rates, the labour market supply of women, and marital satisfaction. The interaction of economic progress and changing gender norms could therefore explain the lower marriage and fertility rates among educated women.

A historical look at deflation

Concerns about deflation – falling prices of goods and services – are rooted in the view that it is very costly. This column tests the historical link between output growth and deflation in a sample covering 140 years for up to 38 economies. The evidence suggests that this link is weak and derives largely from the Great Depression. The authors find a stronger link between output growth and asset price deflations, particularly during postwar property price deflations. There is no evidence that high debt has so far raised the cost of goods and services price deflations, in so-called debt deflations. The most damaging interaction appears to be between property price deflations and private debt.

A little model of the labour market.

JW Mason has an interesting discovery among the data. Specifically, it looks like the US data series for wages, normalised for shifts in the composition of jobs, is much less cyclical than the raw data. In other words, the business cycle seems to affect wages through composition shifts. In recessions, people lose jobs and eventually get hired back into ones with lower productivity and pay than they had before. People who manage to stick to their jobs through the crisis don’t see much difference. In booms, people who lose their jobs (or quit) tend to get hired into ones with higher productivity, and pay, than they had before.

This makes sense. Imagine that people try to pick a job that suits them – or in economicspeak, that maximises their labour productivity. Imagine also that firms try to hire people who suit their requirements. I doubt this will be very difficult. This is a pretty basic market setup, matching workers and vacancies. Now, consider that people tend to acquire skills and knowledge as they work. This might be something exciting, or it might be as dull as someone in sales building up a contacts book. As a result, people will tend to get onto some sort of career path, picking a speciality and getting better at it.

This might be horizontal – people with a highly transferable skill who move across industries – but I think it’s more likely to be vertical. As they gain in skill, knowledge, or just insidership, they are likely to get paid more. We should at least consider that this matches higher productivity. But then, there’s an explosion – suddenly a lot of firms fail, and their employees are on the dole. They now need to search their way back into work. It is likely, at least, that if they have to find it in another sector or even another firm they will lose some of the human capital they acquired in the past. The unemployed are suddenly driven off their optimal productivity path, and are usually under pressure to take any job that comes along, no matter how suboptimal. Until they get back to where they were before the crisis, on their new paths or on their old ones, the economy will forego the difference between their potential and actual production. You could call it an output gap, but that’s taken, so let’s call it the snakes-and-ladders model.

This, in itself, is enough to explain why unemployment is a thing – you can’t price yourself back into a job with a firm that has gone bust – and why productivity might be depressed for some time post-crisis. In the long term people will climb the ladder again, but this is deceptive. Society, and even firms, can think of a long term. Individuals cannot, as life is short. As the man said – in the long run, we are all dead. Hanging around at reduced productivity is a waste of your time. The recovery phase represents a substantial deadweight loss of production to everyone, concentrated on the unemployed. And there are dynamic effects. Contact books get stale, and technology changes, so the longer people stay either unemployed or underemployed, the bigger the gap. This little model also gives us hysteresis.

But we can go further with the snakes-and-ladders model. Markets, we are often told, are information-processing mechanisms. Let’s look at this from a Diego Gambetta-inspired signalling perspective. The only genuinely reliable way to know if someone is any good at a job is to let them try. I have, after all, every reason to pad my CV, overstate my achievements, and conceal my failures. The only genuinely reliable way to know if someone is an acceptable boss is to work for them. They have every reason to talk in circles about pay and repress their authoritarian streak.

In a tight labour market, people move along close-to-optimal career paths. In doing so, they gain both experience, and also reputation, its outward sign. Importantly, they also gain information about themselves – you don’t know, after all, if you can do the job until you try. The same process is happening with firms and with individual entrepreneurs or managers. Because the information is the product of actual experience, it is costly and therefore trustworthy.

Now let’s blow the system up. We introduce a shock that causes a large number of basically random firms to fail and sack everyone. Because the failure of these firms is not informative about the individuals in them, the effect is to destroy the accumulated information in the labour market. Whatever the workers knew about Bust plc is now irrelevant. In so far as they’re now looking for jobs outside the industry, what Bust plc knew about them is also irrelevant. In the absence of information, the market for labour is now in an inefficient out-of-equilibrium state, where it will stay until the information is re-created. Walrasian tatonnement, right?

This explains an important point in Mason’s data that we’ve not got to yet. Why should people thrown off their career paths take much lower productivity jobs? You don’t need much information to know if someone can mow the lawn. In the post-crisis, disequilibrium state, low productivity jobs are privileged over high productivity jobs.

It strikes me that this little model explains a number of major economic problems. The UK’s productivity paradox, for example, is nicely explained by a huge compositional shift, in part driven by labour market reforms designed to make the unemployed take the first job-ish that comes along. Students who graduate into a recession lose out by about $100,000 over their lives. Verdoorn’s law, the strong empirical correlation between productivity and employment, also seems pretty obvious. Axel Leijonhufvud’s idea of the corridor of stability also fits. In the corridor, the market is self-adjusting, but once it gets outside its control limits, anything can happen.

And, you know, despite all the heterodoxy, it’s microfounded. Workers and employers are entirely rational. Money is just money. It’s not quite simple enough to have a single representative agent, because it needs at least two employers and two workers with dissimilar endowments, but it doesn’t need any actors who aren’t empirically observable.

It also has clear policy implications. If the unemployed sit it out and look for something better, you would expect a jobless recovery and then a productivity boom – like the US in the 1990s. If the unemployed take the first job-like position that comes along, you would expect a jobs miracle with terrible productivity growth, flat to falling wages, and a long period of foregone GDP growth. Like the UK in the 2010s. And if your labour market institutions are designed to prevent the information destruction in the first place, with a fallback to Keynesian reflation if that doesn’t cut it? Well, that sounds like Germany in the 2010s.

Call it Hayekian Keynesianism. Macroeconomic stabilisation is vital to keep the information-processing function of the labour market from breaking down.

That said, I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t point out that there are a whole lot of structural forces here that discriminate against specific groups. The post-crisis skew to low productivity jobs wouldn’t work, after all, if workers weren’t forced sellers of labour to capitalists. And there is one very large group of people who tend to get kicked off their optimal career path with lasting consequences. They’re about 50% of the population.

“Editor’s Introduction to The New Economic History and the Industrial Revolution,” J. Mokyr (1998)

I taught a fun three hours on the Industrial Revolution in my innovation PhD course this week. The absolutely incredible change in the condition of mankind that began in a tiny corner of Europe in an otherwise unremarkable 70-or-so years is totally fascinating. Indeed, the Industrial Revolution and its aftermath are so important to human history that I find it strange that we give people PhDs in social science without requiring at least some study of what happened.

My post today draws heavily on Joel Mokyr’s lovely, if lengthy, summary of what we know about the period. You really should read the whole thing, but if you know nothing about the IR, there are really five facts of great importance which you should be aware of.

1) The world was absurdly poor from the dawn of mankind until the late 1800s, everywhere.

Somewhere like Chad or Nepal today fares better on essentially any indicator of development than England, the wealthiest place in the world, in the early 1800s. This is hard to believe, I know. Life expectancy was in the 30s in England, infant mortality was about 150 per 1000 live births, literacy was minimal, and median wages were perhaps 3 to 4 times subsistence. Chad today has a life expectancy of 50, infant mortality of 90 per 1000, a literacy of 35%, and urban median wages of roughly 3 to 4 times subsistence. Nepal fares even better on all counts. The air from the “dark, Satanic mills” of William Blake would have made Beijing blush, “night soil” was generally just thrown on to the street, children as young as six regularly worked in mines, and 60 to 80 hours a week was a standard industrial schedule.

The richest places in the world were never more than 5x subsistence before the mid 1800s

Despite all of this, there was incredible voluntary urbanization: those dark, Satanic mills were preferable to the countryside. My own ancestors were among the Irish that fled the Potato famine. Mokyr’s earlier work on the famine, which happened in the British Isles after the Industrial Revolution, suggest 1.1 to 1.5 million people died from a population of about 7 million. This is similar to the lower end of the range for percentage killed during the Cambodian genocide, and similar to the median estimates of the death percentage during the Rwandan genocide. That is, even in the British Isles, famines that would shock the world today were not unheard of. And even if you wanted to leave the countryside, it may have been difficult to do so. After Napoleon, serfdom remained widespread east of the Elbe river in Europe, passes like the “Wanderbucher” were required if one wanted to travel, and coercive labor institutions that tied workers to specific employers were common. This is all to say that the material state of mankind before and during the Industrial Revolution, essentially anywhere in the world, would be seen as outrageous deprivation to us today; palaces like Versailles are not representative, as should be obvious, of how most people lived. Remember also that we are talking about Europe in the early 1800s; estimates of wages in other “rich” societies of the past are even closer to subsistence.

2) The average person did not become richer, nor was overall economic growth particularly spectacular, during the Industrial Revolution; indeed, wages may have fallen between 1760 and 1830.

The standard dating of the Industrial Revolution is 1760 to 1830. You might think: factories! The railroad! The steam engine! High Britannia! How on Earth could people have become poorer? And yet it is true. Brad DeLong has an old post showing Bob Allen’s wage reconstructions: Allen found British wages lower than their 1720 level in 1860! John Stuart Mill, in his 1870 textbook, still is unsure whether all of the great technological achievements of the Industrial Revolution would ever meaningfully improve the state of the mass of mankind. And Mill wasn’t the only one who noticed, there were a couple of German friends, who you may know, writing about the wretched state of the Working Class in Britain in the 1840s as well.

3) Major macro inventions, and growth, of the type seen in England in the late 1700s and early 1800s happened many times in human history.

The Iron Bridge in Shropshire, 1781, proving strength of British iron

The Industrial Revolution must surely be “industrial”, right? The dating of the IR’s beginning to 1760 is at least partially due to the three great inventions of that decade: the Watt engine, Arkwright’s water frame, and the spinning jenny. Two decades later came Cort’s famous puddling process for making strong iron. The industries affected by those inventions, cotton and iron, are the prototypical industries of England’s industrial height.

But if big macro-inventions, and a period of urbanization, are “all” that defines the Industrial Revolution, then there is nothing unique about the British experience. The Song Dynasty in China saw the gun, movable type, a primitive Bessemer process, a modern canal lock system, the steel curved moldboard plow, and a huge increase in arable land following public works projects. Netherlands in the late 16th and early 17th century grew faster, and eventually became richer, than Britain ever did during the Industrial Revolution. We have many other examples of short-lived periods of growth and urbanization: ancient Rome, Muslim Spain, the peak of the Caliphate following Harun ar-Rashid, etc.

We care about England’s growth and invention because of what followed 1830, not what happened between 1760 and 1830. England was able to take their inventions and set on a path to break the Malthusian bounds – I find Galor and Weil’s model the best for understanding what is necessary to move from a Malthusian world of limited long-run growth to a modern world of ever-increasing human capital and economic bounty. Mokyr puts it this way: “Examining British economic history in the period 1760-1830 is a bit like studying the history of Jewish dissenters between 50 B.C. and 50 A.D. At first provincial, localized, even bizarre, it was destined to change the life of every man and women…beyond recognition.”

4) It is hard for us today to understand how revolutionary ideas like “experimentation” or “probability” were.

In his two most famous books, The Gifts of Athena and The Lever of Riches, Mokyr has provided exhausting evidence about the importance of “tinkerers” in Britain. That is, there were probably something on the order of tens of thousands of folks in industry, many not terribly well educated, who avidly followed new scientific breakthroughs, who were aware of the scientific method, who believed in the existence of regularities which could be taken advantage of by man, and who used systematic processes of experimentation to learn what works and what doesn’t (the development of English porter is a great case study). It is impossible to overstate how unusual this was. In Germany and France, science was devoted mainly to the state, or to thought for thought’s sake, rather than to industry. The idea of everyday, uneducated people using scientific methods somewhere like ar-Rashid’s Baghdad is inconceivable. Indeed, as Ian Hacking has shown, it wasn’t just that fundamental concepts like “probabilistic regularities” were difficult to understand: the whole concept of discovering something based on probabilistic output would not have made sense to all but the very most clever person before the Enlightenment.

The existence of tinkerers with access to a scientific mentality was critical because it allowed big inventions or ideas to be refined until they proved useful. England did not just invent the Newcomen engine, put it to work in mines, and then give up. Rather, England developed that Newcomen engine, a boisterous monstrosity, until it could profitably be used to drive trains and ships. In Gifts of Athena, Mokyr writes that fortune may sometimes favor the unprepared mind with a great idea; however, it is the development of that idea which really matters, and to develop macroinventions you need a small but not tiny cohort of clever, mechanically gifted, curious citizens. Some have given credit to a political system, or to the patent system, for the widespread tinkering, but the qualitative historical evidence I am aware of appears to lean toward cultural explanations most strongly. One great piece of evidence is that contemporaries wrote often about the pattern where Frenchmen invented something of scientific importance, yet the idea diffused and was refined in Britain. Any explanation of British uniqueness must depend on Britain’s ability to refine inventions.

5) The best explanations for “why England? why in the late 1700s? why did growth continue?” do not involve colonialism, slavery, or famous inventions.

First, we should dispose of colonialism and slavery. Exports to India were not particularly important compared to exports to non-colonial regions, slavery was a tiny portion of British GDP and savings, and many other countries were equally well-disposed to profit from slavery and colonialism as of the mid-1700s, yet the IR was limited to England. Expanding beyond Europe, Dierdre McCloskey notes that “thrifty self-discipline and violent expropriation have been too common in human history to explain a revolution utterly unprecedented in scale and unique to Europe around 1800.” As for famous inventions, we have already noted how common bursts of cleverness were in the historic record, and there is nothing to suggest that England was particularly unique in its macroinventions.

To my mind, this leaves two big, competing explanations: Mokyr’s argument that tinkerers and a scientific mentality allowed Britain to adapt and diffuse its big inventions rapidly enough to push the country over the Malthusian hump and into a period of declining population growth after 1870, and Bob Allen’s argument that British wages were historically unique. Essentially, Allen argues that British wages were high compared to its capital costs from the Black Death forward. This means that labor-saving inventions were worthwhile to adopt in Britain even when they weren’t worthwhile in other countries (e.g., his computations on the spinning jenny). If it worthwhile to adopt certain inventions, then inventors will be able to sell something, hence it is worthwhile to invent certain inventions. Once adopted, Britain refined these inventions as they crawled down the learning curve, and eventually it became worthwhile for other countries to adopt the tools of the Industrial Revolution. There is a great deal of debate about who has the upper hand, or indeed whether the two views are even in conflict. I do, however, buy the argument, made by Mokyr and others, that it is not at all obvious that inventors in the 1700s were targeting their inventions toward labor saving tasks (although at the margin we know there was some directed technical change in the 1860s), nor it is even clear that invention overall during the IR was labor saving (total working hours increased, for instance).

Mokyr’s Editor’s Introduction to “The New Economic History and the Industrial Revolution” (no RePEc IDEAS page). He has a followup in the Journal of Economic History, 2005, examining further the role of an Enlightenment mentality in allowing for the rapid refinement and adoption of inventions in 18th century Britain, and hence the eventual exit from the Malthusian trap.

It depends what you study, not where

A new report from PayScale, a research firm, calculates the returns to a college degree. Its authors compare the career earnings of graduates with the present-day cost of a degree at their alma maters, net of financial aid. College is usually worth it, but not always, it transpires. And what you study matters far more than where you study it.

Engineers and computer scientists do best, earning an impressive 20-year annualised return of 12% on their college fees (the S&P 500 yielded just 7.8%). Engineering graduates from run-of-the-mill colleges do only slightly worse than those from highly selective ones. Business and economics degrees also pay well, delivering a solid 8.7...

Urban[ism] Legend: The Free Market Can’t Provide Affordable Housing

Over at Greater Greater Washington, Ms. Cheryl Cort attempts to temper expectations of what she calls the “libertarian view (a more right-leaning view in our region)” on affordable housing. It is certainly reassuring to see the cosmopolitan left and the pro-market right begin to warm to the benefits of liberalization of land-use. Land-use is one area the “right,” in it’s fear of change, has failed to embrace a widespread pro-market stance. Meanwhile, many urban-dwellers who consider themselves on the “left” unknowingly display an anti-outsider mentality typically attributed to the right’s stance on immigration. Unfortunately, in failing to grasp the enormity of the bipartisan-caused distortion of the housing market, Ms. Cort resigns to advocate solutions that fail to deliver widespread housing affordability.

Yes, adding more housing must absolutely be a part of the strategy to make housing more affordable. And zoning changes to allow people to build taller and more usable space near transit, rent out carriage houses, and avoid expensive and often-unnecessary parking are all steps in the right direction. But some proponents go on to say relaxing zoning will solve the problem all on its own. It won’t.

Well, if “relaxing” zoning is the solution at hand, she may be right – relaxing will only help a tad… While keenly aware of the high prices many are willing to pay, Cort does not seem to grasp the incredible degree to which development is inhibited by zoning. “Relaxing” won’t do the trick in a city where prices are high enough to justify skyscrapers with four to ten times the density currently allowed. When considering a supply cap that only allows a fraction of what the market demands, one can not reasonably conclude “Unlimited FAR” (building density) would merely result in a bit more development here and there. A radically liberalized land-use regime would deliver numbers of units several times what is permitted under current regulation.

Ms. Cort correctly concludes that because of today’s construction costs, new construction would not provide housing at prices affordable to low income people. This will certainly be the case in the most expensive areas where developers would be allowed to meet market demands by building 60 story skyscrapers. Advocates of land-use liberalization who understand the costs of construction would not claim that dense new construction will house the poor. But if enough supply is allowed to come to market today, today’s new construction will become tomorrow’s affordable housing. And this brings us to the more meaningful discussion: filtering. Here’s where Ms. Cort’s analysis completely falls apart.

It is true that increasing supply eases upward pressure on all prices. But the reservoir of naturally cheaper, older buildings runs out after a while.

Tragically, Ms. Cort is using the current radically supply-constrained paradigm to analyze a free-market counter-factual. If development at levels several times the current rate were allowed over the past few cycles, the reservoir of cheaper, older buildings would have remained plentiful and affordable. If the market were allowed to meet demand for high-end units in the form of dense new construction, there would be little or no market pressure for unsubsidized market-rate units to be converted into luxury units. The 1400 Block of W Street NW example she gives would almost certainly still be affordable.

On a larger scale, the increased supply of housing in the area helps absorb demand for more housing, but it’s not enough to stem the demand for such a sought-after location. Between 2005 and 2011, the rental housing market’s growth added more than 12,500 units. But at the same time, $800/month apartments fell by half, while $1000/month rentals nearly doubled. Strong market demand will shrink the availability of low-priced units. That’s what has happened over the last decade as DC transformed from a declining city into a rapidly growing one.

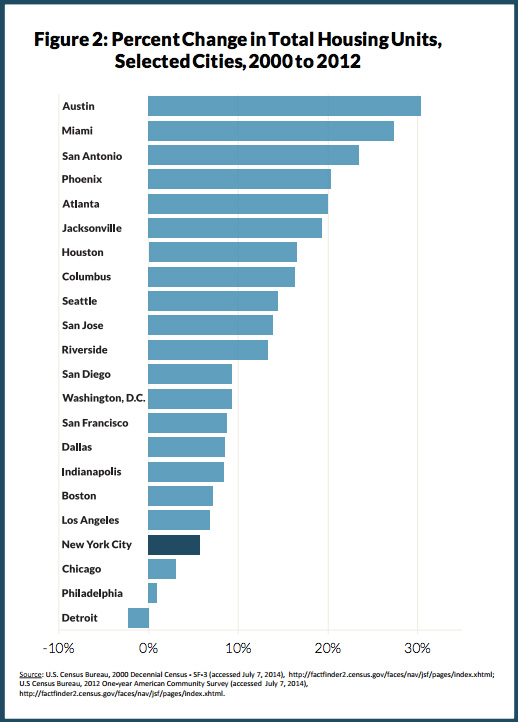

But, 12,500 units is the amount of supply added under the current over-regulated regime. This amount of development is minuscule in a large city. (see diagram below) What if DC allowed as much supply growth as Austin or Miami? The 12,500 figure would triple. Further, since Austin and Miami are far from free-market, the development rate in a truly free-market DC would certainly exceed a tripling. If you consider the amount of supply that would have been added over the last several decades in an unlimited FAR DC, Ms. Cort’s position starts to sound quaint. Conservatively assuming 50-100,000 units of rental housing would have been developed over the last few decades of DC’s growth, rents certainly would not have doubled. I’ll go out on a limb and estimate that average rent growth would be close to inflation.

Ms. Cort wants housing to be less than 30% of gross income for nearly all residents. Will the market provide new housing affordable to minimum wage earners at the most expensive intersection in Georgetown? Probably not, and I hope she isn’t setting the bar that high. While nobody is wise enough to know whether a free-market in land use would accomplish this, a free-market DC could be affordable to 50-100,000 more people than the zoned-to-death DC of today. Will stock of units deemed affordable to low wage earners be of the quality, location, and size acceptable to Cort? The necessity for further intervention is a subjective preference.

While acknowledging the validity of liberalization in her critique of supply-and-demand denialism, Cort’s conclusion fails to look at supply and demand wholistically:

Supply matters, but it’s not the whole story

Wrong. Supply really must be part of the whole story. A city is only affordable to the number of residents it houses affordably. Failure to recognize this only shifts the burden from one demographic to another. (and it won’t be the rich who pays the price) If a zoning-plagued city fails to provide 1,000 units demanded, 1,000 people can no longer afford to live there. Even if that city chose to subsidize housing for 2,000 people at 50-80% of AMI, that doesn’t change the fact that 1,000 people who wanted to live in that city must leave. Any viable solution (free-market or otherwise) must involve increasing supply significantly, either through creating supply directly or subsidizing demand through vouchers, which induces new development. But, this simply can’t happen if overall supply is capped through zoning.

Panda Antivirus Flags Itself As Malware

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

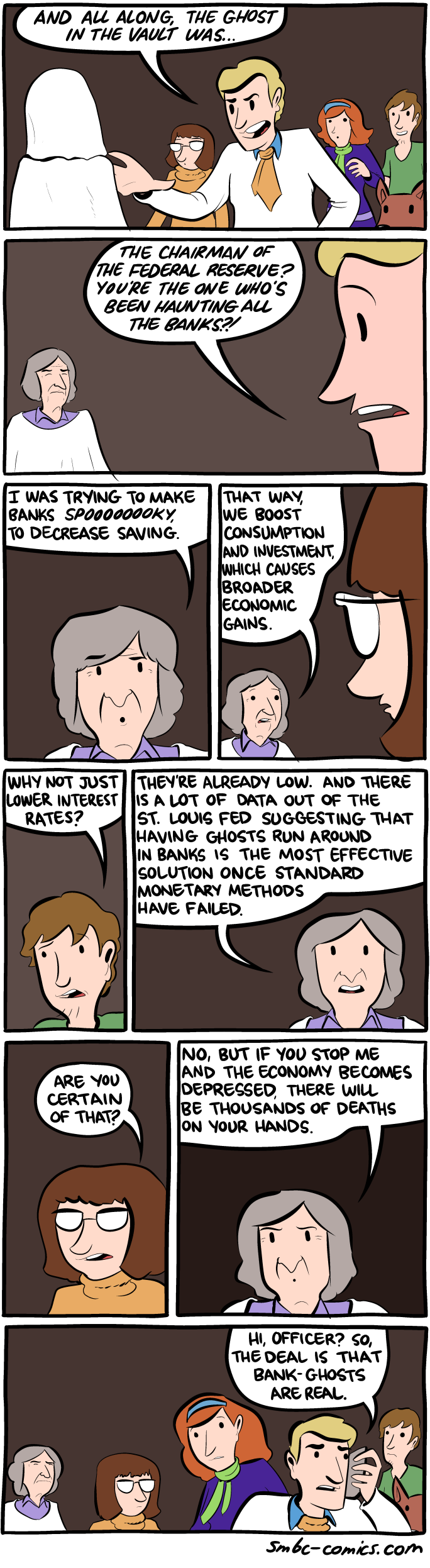

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - The Bank Ghost

New comic!

Today's News:

NEW BAHFEST DAY!

<iframe width="400" height="225" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/8b32c7uan5U" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The rise of residential segregation

Racial disparities in socioeconomic conditions remain a major policy issue throughout the world. This column applies a new neighbour-based measure of residential segregation to US census data from 1880 and 1940. The authors find that existing measures understate the extent of segregation, and that segregation increased in rural as well as urban areas. The dramatic decline in opposite-race neighbours during the 20th century may help to explain the persistence of racial inequality in the US.

Indian Gov't Wants Worldwide Ban On Rape Documentary, Including Online

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Recessions and the making of career criminals

Recessions can lead to an increase in youth unemployment, which could later negatively affect labour market outcomes. This column explores the effect of recessions on criminal activity. The findings indicate a substantial effect on initiating and forming youth careers. There is initially strong and eventually long-lasting detrimental effect of entering the labour market during a recession for individuals at the threshold of criminal activity. These effects are economically substantial and potentially more disturbing than short-run effects.

As Big As Net Neutrality? FCC Kills State-Imposed Internet Monopolies

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Europe’s proposed capital markets union

The proposed EU capital markets union aims to revitalise Europe’s economy by creating efficient funding channels between providers of loanable funds and firms best placed to use them. This column argues that a successful union would deliver investment, innovation, and growth, but it depends on overcoming difficult regulatory challenges. A successful union would also change the nature of systemic risk in Europe.

Passing dishonesty on to children

Dishonesty is a pervasive and costly phenomenon. This column reports the results of a lab experiment in which parents had an opportunity to behave dishonestly. Parents cheated the most when the prize was for their child and their child was not present. Parents cheated little when their child was present, but were more likely to cheat in front of sons than in front of daughters. The latter finding may help to explain why women attach greater importance to moral norms and are more honest.

Explore our interactive guide to US degree returns across more subjects

Explore our interactive guide to US degree returns across more subjects