"Gradually, America's management of its wild animals has evolved, or maybe devolved, into a surreal kind of performance art," reflects Jon Mooallem, author of Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America.

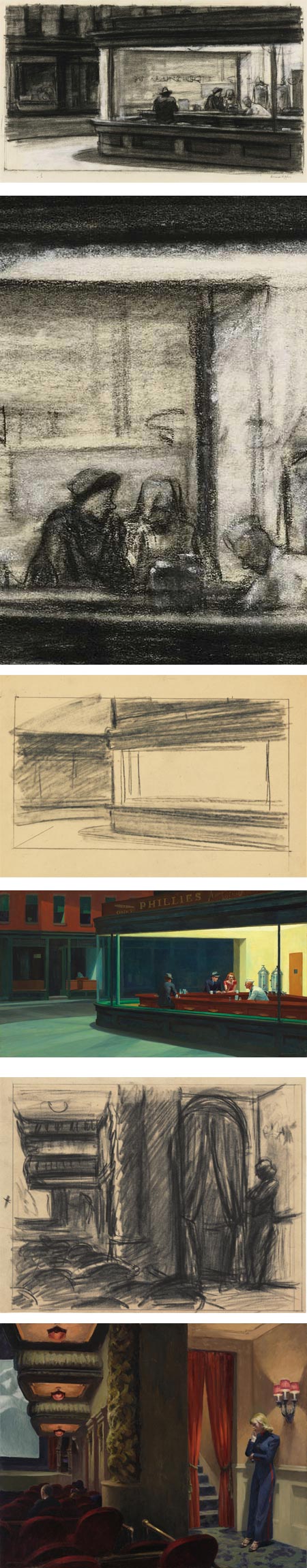

Detail from the cover of Jon Mooallem's Wild Ones.

This is a surprisingly generous statement, considering that Mooallem has spent the last few years researching a harrowing litany of accidental extinctions and unintended consequences—including a surreal day spent chasing ex-convict Martha Stewart as she and her film crew pursued polar bears across the Arctic tundra—in order to untangle the complicated legal and emotional forces that shape America's relationship with wildlife.

Despite the humor, the stakes are high: half the world's nine million species are expected to be extinct by the end of this century, and, as Mooallem explains, many of those that do survive will only hang on as a result of humans' own increasingly bizarre interventions, blurring the line between conservation and domestication to the point of meaninglessness.

On a foggy morning in San Francisco, Venue met Mooallem for coffee and a conversation that ranged from tortoise kidnappings to polar bear politics. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

• • •

The polar bear tourism industry in Churchill, Manitoba, relies on a dozen specially built vehicles called Tundra Buggies that take tourists and their cameras out to see the world's southernmost bear population. Photo: Polar Bears International.

Geoff Manaugh: In the book, you’ve chosen to focus on two very charismatic, photogenic, and popular animals: the whooping crane and the polar bear.

Jon Mooallem: They’re the celebrities of the wildlife world.

Manaugh: Exactly. But there’s a third example, in the middle section of the book, which is a butterfly. It’s not only a very obscure species in its own right, but it’s also found only in a very obscure Bay Area preserve that most people, even in Northern California, have never heard of. What was it about the story of that butterfly, in particular, that made you want to tell it?

Mooallem: I thought it would be really interesting to go from the polar bear, which is the mega-celebrity of the animal kingdom, to its complete opposite—to something no one really cared about—and to see what was at stake in a story where the general public doesn’t really care about the animal in question at all. It turned out that there was a hell of a lot at stake for the people working on that butterfly.

Lange's Metalmark butterfly (Apodemia mormo langei). Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It’s called the Lange’s Metalmark butterfly, and it’s about the size of a quarter. As you said, it only lives in this one place called Antioch Dunes, which is about sixty-seven acres in total. It is surrounded by a waste-transfer station, a sewage treatment plant, and a biker bar, and there’s a gypsum factory right in the middle that makes wallboard. You can’t even walk across the preserve, actually, because of this giant industrial facility in the middle of it.

In fact, the outbuilding where Jaycee Dugard, the kidnapping victim, was held is just round the corner.

Counting butterflies at Antioch Dunes. Photo: Jon Mooallem

It’s a forgotten place. It’s not the sort of place you’d expect to spend a lot of time in if you’re writing a book about wildlife in America.

On top of all that, not only is the butterfly the animal in the book that people won’t have heard of, or that they won’t know much about, but it’s also the one that I didn’t know very much about, going in. Looking back on it, it was somewhat audacious to say in my book proposal that a third of the book was going to be the story of this butterfly, because I really knew almost nothing about it! But it ended up being by far the most fascinating story, for me. That’s at least partly because I had the sense that I was looking at things that no one had ever looked at and talking to people who no one had ever talked to before.

Jana Johnson leads a captive breeding project for the Lange's Metalmark from inside America's Teaching Zoo, where students in Moorpark College's Exotic Animal Training and Management degree program learn their trade. Photos: (top) Jason Redmond, Ventura County Star; (bottom) Louis Terrazzas, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It also seemed as though, when you’re working in an environment like that on a species that doesn’t get a lot of support or interest, you’re confronting a lot of the fundamental questions of environmentalism in a much more dramatic way. You have to work harder to sort through them, because it’s difficult to make simple assumptions about what you’re doing—that what you’re doing is worthwhile and good—when you don’t have anyone telling you that, and when it looks as hopeless as it looks with the Lange’s Metalmark.

Maybe hopeless is too strong a word—but you can’t transpose romantic ideas about wilderness and animals onto the situation, because it’s just so glaringly unromantic. You can’t stand in Antioch Dunes and take a deep breath of fresh air and feel like you’re in some primordial wilderness. You don’t have that luxury.

The other thing that was interesting about the butterfly story was the fact that it was happening on such a small scale. The butterfly’s always just lived in this one spot—it’s the only place it lives on earth—so you could look at what happened to this small patch of land over a hundred years and meet all the people who came in & out of the butterfly’s story. It was quite self-contained. It was almost like a stage for a play to happen on.

Butterflies on display in cases at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Photo: Venue.

Manaugh: Harry Lange, for whom the butterfly is named, has a great line that seems to sum up so much of the sadness and stupidity in the human relationship with wild animals. He said, after exterminating the very last of the Xerces Blue butterfly: “I always thought there would be more…”

Mooallem: Right—and that was the other extraordinary thing about the butterfly story.

When I started working on the book, I had no idea about the history of butterfly collectors in the Bay Area. Apparently, the Bay Area was a big hotspot for butterflies, because of the microclimates here. It can be ten or fifteen degrees hotter in the Mission District than it is at the beach; there can be fog in some places and not others; and all of this creates a sort of Galapagos Island effect. The whole peninsula is peppered with these different micro-populations of butterflies because of the different microclimates.

Meanwhile, in the early twentieth century, at a time when the Audubon Society and other groups were being founded and there was a turn against the overhunting of species, it still seemed OK and sort of benign to collect butterflies. It wasn’t considered “hunting.” You could transfer all of that ambition to conquer nature and discover new things to collecting butterflies. You’re here at the very end of North America, where the country finally runs out of room, and now you’re starting to run out of animals too, but there were still enough butterflies to collect and name after yourself.

The Xerces Blue is the first butterfly in America known to have gone extinct due to human disturbance. Photo: Andrew Warren/butterfliesofamerica.com

The story of Xerces Blue, which is the butterfly that Lange thought there would always be more of, is just incredible. Back then, past 19th Avenue, it was all sand dunes. I actually met a friend of Lange’s, named Ed Ross, who was a curator at the California Academy of Sciences; he had to be in his late eighties or early nineties.

He told me about growing up as a kid here and taking the streetcar out to 19th Avenue and just getting out with his butterfly net and walking to Ocean Beach over the dunes. Occasionally you’d see a hermit, he said.

Richmond Sand Dunes (1890s). Photo: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco, CA, via FoundSF.

Dunes along Sunset Boulevard, San Francisco (1938). Photo: Harrison Ryker, via David Rumsey Map Collection.

That generation of butterfly nuts who were living in San Francisco in the early twentieth century saw that habitat being erased in front of their eyes.

That backstory really helped to shape my perception of a lot of things in the book by elongating the timescale. It brought up the whole idea of shifting baselines—this gradual, generational change in our accepted norm for the environment—and all these other, deeper questions that wouldn’t have come up if I’d just followed Martha Stewart around filming polar bears, as I do in the first section of the book. It’s a very different experience to zoom out and take in the entirety of a story as I did with the Lange’s Metalmark, which is why I think I enjoyed it so much.

Nicola Twilley: It’s interesting to note that Ed Ross doesn’t actually figure in the book, and that, elsewhere, you allude to several intriguing stories in just a sentence or two—to things like the volunteers who count fish at the Bonneville Dam. Instead, you deliberately keep the focus on the bear, the butterfly, and the bird. But what about all the animals or all the stories that didn’t make it into the book? Were there any particular gems that you had to leave out or that you wish you had kept?

Mooallem: There were tons! The fish counting thing is a perfect example.

Janet the fish counter, hard at work. Photo: Jon Mooallem.

I spent a day at the Bonneville Dam, and it was completely surreal. I barely touch on it in the book, but the question of how to get fish around the dam is a really interesting design problem. There have been different structures that were built and then shown not to work, and so they’ve had to adapt them or retrofit them, and that’s ended up creating all new problems that need to have something built to solve them, and so on.

The government has actually moved an entire colony of seabirds that were eating the fish at the mouth of the river. The fish that got through the dam would get to the mouth of the Columbia River, but then the double-crested cormorants would eat them all. So the government picked up the birds and moved them to another island in the river.

I felt as though, normally, when you hear about these kinds of stories, you just scratch the surface. We’re so used to hearing endangered species stories in very two-dimensional, heroic ways, where so-and-so is saving the frog or whatever, and I just knew that it couldn’t be that easy. If it was that straightforward—if you could just go out and pull up some weeds and the butterfly would survive—it wouldn’t be very meaningful work. That was the space I really wanted to get into—the muddiness where things don’t work out the way we draw them on paper.

At the same time, I was able to mention a lot of these bizarre stories—but, as you say, almost as an aside. Each one of those things could have been a much longer, deeper story. Take, for example, the “otter-free zone,” which was this incredible saga: the government was reintroducing otters in Southern California and, because of complaints from fishermen and the oil industry, they needed to control where the otters would swim. A biologist would have to go out in a boat with binoculars to look for otters that were inside the otter-free zone and, if he saw them, he’d have to try to capture them when they were sleeping and move them. It was just a hilarious, miserable failure. I spent a lot of time reporting on that—talking to the biologist and hearing what that work was actually like to have to do—yet, in the end, I only mention it. But I know there’s a deeper story there.

Sea-otter in Morro Bay, California, just north of the former otter-free zone. Photo: Mike Baird.

In fact, there’s a section of the book where I rattle off a bunch of these examples—there’s the project to keep right whales from swimming into the path of natural gas tankers, and there’s the North Carolina wolves and their kill-switch collars, and so on. Each one of those is its own Bonneville Dam story—its own complicated saga of solutions and newer solutions to problems that the original solutions caused. You could really get lost in that stuff. I did get lost in all that stuff for a long time.

This is my first book, of course, and I feel as though that’s the joy and the luxury of a book—that you do have the time and space to get lost in those things for a little while.

Manaugh: It’s funny how many of those kinds of stories there are. I remember an example that Liam Young, an architect based in London, told me. He spent some time studying the Galapagos Islands, and he told me this incredible anecdote about hunters shooting wild goats, Sarah Palin-style, from helicopters, because the goats had been eating the same plants that the tortoises depended on.

BBC Four footage of the Galapagos Island goat killers.

But, at one point, some local fishermen were protesting that the islands’ incredibly strict eco-regulations were destroying their livelihood, so they took a bunch of tortoises hostage. What was funny, though, is that all the headlines about this mention the tortoises—but, when you read down to paragraph five or six, it also mentions that something like nineteen scientists were also being held hostage. [laughter] It was as if the human hostages weren’t even worth mentioning.

Mooallem: [laughs] Wow. That reminds me of one story I saw but never followed up on, about some fishermen in the Solomon Islands who had slaughtered several hundred dolphins because some environmental group had promised them money not to fish, but then didn’t deliver the money.

Twilley: When you invest an animal with that much symbolic power, the stakes get absurdly high.

Mooallem: Exactly—look at the polar bear. Of course, the polar bear has lost a lot of its cachet. I don’t know whether you saw the YouTube video that Obama put out to accompany his big climate speech in June, but I was surprised: there wasn’t a single polar bear image in it. It was all floods and storms and dried-up corn. Four years ago, there would have definitely been polar bears in that video.

Today, though, the polar bear is just not as potent a symbol. It’s become too political. It doesn’t really resonate with environmentalists anymore and it ticks off everyone else. What’s amazing is that it’s just a freaking bear, yet it’s become as divisive a figure as Rush Limbaugh.

From "Addressing the threat of Climate Change," a video posted on the White House YouTube channel, June 22, 2013.

Manaugh: Speaking of politics, it feels at times as if the Endangered Species Act—that specific piece of legislation—serves as the plot generator for much of your book. Its effects, both intended and surreally unanticipated, make it a central part of Wild Ones.

Mooallem: It really does generate all the action, because it institutionalizes these well-meaning sentiments, and it makes money and federal employees available to act on them. It amps up the scale of everything.

The first thing that I found really interesting is the way in which the law was passed. It was pretty poorly understood by everyone who voted on it. The Nixon administration saw it as a feel-good thing. It was signed in the doldrums between Christmas and New Year’s, almost as a gift to the nation and a kind of national New Year’s resolution rolled into one. And it was passed in 1973, as well, during both Vietnam and Watergate, so the timing was perfect for something warm and fuzzy as a distraction.

But most people never read the law and they didn’t realize that some of the more hardcore environmentalist staff-members of certain congressmen had put in provisions that were a lot more far-reaching than any of the lawmakers imagined. Nixon didn’t understand that it would protect insects, for example. It was really just seen as protecting charismatic national symbols, in completely unspecified, abstract ways.

Nixon signing the Endangered Species Act. AP photo via Politico.

In the preamble to the law itself—I don’t remember the exact quote—it says something like: “We’re going to protect species and their ecosystems from extinction as a consequence of the economic development of the nation.” Passing a law that is supposed to put a check on the development and growth of the nation—all the things government is supposed to promote—is pretty astounding.

Obviously, the law’s done a tremendous amount of good, but I also think that, because of its almost back-room origins, there is a kind of sheepishness and reluctance among a lot of conservationists to draw on it to its full extent. I don’t spend a lot of time in the book on government policy, but, to get a little wonky for a second, I do find it interesting that there’s this hesitancy to really use the Endangered Species Act as a cudgel.

Groups like Center for Biological Diversity that basically spend their time suing the government to hold it to the letter of the Endangered Species Act, are quite controversial among other environmentalists for that very reason. There’s a feeling that it is too dangerous to really unleash the full power of the law. In some ways, I completely understand that, because there is no way to work these questions out. It’s not a zero sum game.

But the Endangered Species Act is always under attack. It’s always a political talking point to be able to say: we’re spending hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars to study slugs or whatever.

Twilley: Then there’s the fact that it’s written so as to protect entire ecosystems, rather than just the animals themselves.

Mooallem: Exactly. To me, that’s actually the even more interesting part of this. Rudi Mattoni, the lepidopterist, pointed this out to me, and it’s why he became so disillusioned with the butterfly preservation work he was doing. The law says that it is supposed to protect endangered species and the ecosystems that they depend on. He and a lot of other people feel that the approach has been completely centered on species themselves at the expense of the larger ecosystem.

Even before the Lange’s Metalmark was listed as endangered, the Antioch Dunes ecosystem had been unraveling for decades. It was already pretty much destroyed. But, using the power of the Endangered Species Act, using the power of the federal government, and using a Fish & Wildlife Service employee whose job is just pulling weeds and keeping the plants that the butterfly needs in place, we’ve been able to maintain the butterfly there, in a place where it doesn’t really belong anymore because the landscape has changed so much.

I guess you could say that one of the weaknesses of the law—or you could say that’s actually the strength of the law, because it has protected a species from extinction even long after it should have been extinct, at least in an ecological sense. But it does bring up questions about what we are actually trying to accomplish.

Churchill's "polar bear jail," where bears that come into town are kept in one of twenty-eight cells, and held without food for up to a month so that they don't associate human settlements with a food reward. Photo: Bob and Carol Pinjarra.

At the end of its "sentence," if the Hudson Bay still hasn't frozen over, the bear is drugged and airlifted by helicopter to be released north of town, closer to where the ice first forms. Photo: Nick Miroff, via Jon Mooallem.

Manaugh: Preservation of an entire ecosystem, if you were to follow the letter of the law, would require an absolutely astonishing level of commitment. Saving the polar bear, in that sense, means that we’d have to restore the atmosphere to a certain level of carbon dioxide, and reverse Arctic melting, which might mean reforesting the Amazon or cutting our greenhouse gas emissions to virtually nothing, overnight. It’s inspiringly ambitious.

Mooallem: As I try to explain in the book, that’s basically why the polar bear became so famous, for lack of a better word. It became an icon of climate change, because in a shrewd, “gotcha” kind of way, the Center for Biological Diversity and other environmentalists chose the polar bear as their tool to try to use the Endangered Species Act to put pressure on the Bush administration to deal with climate change as a much larger problem.

Even though the environmental groups themselves admitted it was very unlikely that this would work, they were trying to make the case that the polar bear is endangered, that the thing that is endangering it is climate change, and that the government is legally compelled by the Endangered Species Act to deal with this threat to an Endangered Species. So, if you accept that the polar bear is endangered, then you have to accept the larger responsibility of dealing with climate change.

It’s a completely back-door way to try to force the government to act on climate change, but the result was that the polar bear ended up with this superstar status and popular recognition among the general public, which I found amazing.

The not-sufficiently-charismatic Kittlitz's Murrelet. Photo: Glen Tepke, National Audubon Society.

What’s also interesting is that the Center for Biological Diversity had actually tried this tactic once before, using a bird called the Kittlitz’s Murrelet, and it completely failed. There’s this thing called the “warranted but precluded” category of the Endangered Species Act, which is basically a loophole.

If a species is endangered but the Fish & Wildlife Service or another agency feels that they can’t deal with it right now, they can just say, “Yes, we agree that this species is endangered, so we’re going to put it in a waiting room called ‘warranted but precluded,’ and we’ll get to it as soon as we’re done cleaning up this other mess.” Because there are so many species that are endangered and the threats keep escalating, the government has been able to shunt species after species onto that “warranted but precluded” list.

When the Center for Biological Diversity and a few other groups tried to pressure the administration to do something about climate change by getting the Kittlitz’s Murrelet listed as an Endangered Species, the government just used the “warranted but precluded” loophole, which also meant they didn’t have to rule on climate science or make any really difficult decisions.

But the Kittlitz’s Murrelet failed to inspire any kind of public support, so there was no pressure on the administration to do anything. The environmentalists who were petitioning to get the polar bear listed as part of their strategy to deal with climate change knew that the government could very easily apply the same loophole to the bear and duck the whole issue of climate science, again.

During the public comment period preceding the polar bear's accession to Endangered Species status, Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne received half a million letters and postcards, many of which were from children. Via Jon Mooallem.

The Center for Biological Diversity realized that they needed a public relations strategy as well as a legal strategy, and, by picking the polar bear, they knew that they could put the Bush administration on the spot. The Bush administration couldn’t just put the polar bear in this infinite waiting room, because people would be upset.

Kids started writing letters to the Secretary of the Interior begging him to save the polar bear. They were sending in their own hand-drawn pictures of bears, drowning.

A 2007 letter from a child to Dirk Kempthorne included this drawing of a drowning polar bear being eaten simultaneously by a shark and a lobster. Via Jon Mooallem.

In some ways, the premise of the book is that our emotions and imaginations about these animals dictates their ability to survive in the real world, and this story was a particularly fascinating—not to mention peculiar—example in which all this sentimental gushing over polar bears, which, on the face of it, seems mawkish and kind of silly, was the lynchpin in a legal proceeding. In that case, our emotions about this animal really did matter.

Of course, there’s a whole other part of the story where the administration got around it anyway. But, for a while, it mattered.

Twilley: In the book, you encounter a whole range of attitudes that people hold toward wild animals and conservation, and the journeys that they take from idealism to pragmatism to cynicism and despair. There’s William Temple Hornaday, for example, who gets ever more ambitious and optimistic, and who goes from being a taxidermist who hunted buffalo to founding the National Zoo, and then on to a project to restock the Great Plains.

Manikin for Male American Bison, Hornaday (1891), via Hanna Rose Schell; Hornaday's innovative taxidermy "Buffalo Group," originally displayed at the U.S. National Museum (now the Smithsonian), and since relocated to Fort Benton, Montana (photo: Pete and the Wonder Egg).

Then there’s Rudi Mattoni, the lepidopterist you were talking about, who starts out as a pioneer of captive breeding and reintroduction, and then gives up and moves to Buenos Aires to catalog plants and animals so that at least we will have a record of what we’ve destroyed. Through the process of visiting all these places and spending time talking with all these people, did your own attitude toward wild animals and conservation evolve or shift at all?

Mooallem: What was great about writing the book was being able to absorb all these different perspectives. I met all these different people, some of whom are incredibly jaded and some of whom are incredibly idealistic, but, when you step back, you see that, as a species, we’re all in this struggle together, and this incredibly diverse group of people are all doing their best to grab hold of some piece of it and try to solve it.

That was where the “weirdly reassuring” part of my book title came from—from looking at conservationists as a breed, rather than just an individual person. If I had just written a book about the many, many old, battle-scarred conservationists who are extremely bitter and who claim to have given up, I think I would have ended up being really depressed. I think that it’s important to remember that there are people at all different points on that spectrum of idealism and disillusionment and they all serve a purpose. I identified with all of them, and that kept me from identifying too strongly with any one of them.

William Temple Hornaday's table of wild animal intelligence. Via Jon Mooallem.

I wasn’t trying to advocate any particular position or solve any problems with this book. I actually didn’t realize this till the end, but what I was really doing was just trying to figure out how you’re supposed to feel about all this. How should you feel and respond when you look at everything that’s going on with the environment? What I tried to do is collect the attitudes and emotions of the people that I met and than to take what was useful.

I would get off the phone, for instance, with someone like Mattoni and he would be so horribly pessimistic about everything, yet somehow I would feel slightly exhilarated by it. Here’s someone who is so close to these questions—really big questions about what the place of humans on earth should be—and he’s just totally beaten down by them. But he’s in contact with them. He’s living in engagement with those kinds of questions, and there was something beautiful about that. It doesn’t necessarily make me hopeful, but it does make me feel reassured in some way.

People who haven’t read the book keep asking me, “What’s so weirdly reassuring about it?” And I don’t really know how to explain it. In the book, I just try to recreate the experience that I went through, so that, hopefully, when people get to the end of the book they can have gone through the same range of emotions, so that they also feel weirdly reassured.

Manaugh: As far as the human attitude to wildness goes, I think the role of the child is a fascinating subplot. The idea of the wild, feral child is both fascinating and terrifying in popular culture—I’m thinking of Werner Herzog’s newly restored movie about Kasper Hauser, for example, or about recent newspaper articles in the UK expressing fear about "feral children” starting riots in the streets. It seems like humans want to make children as domesticated as possible, as fast as possible, and that, in a sense, the role of education and acculturation is exactly the task of de-wilding human animals.

Mooallem: I don’t know: among certain people in America right now, it seems as though it’s almost going the other way, that there’s a kind of romanticization of kids as a noble, unspoiled embodiment of nature. We haven’t ruined them yet. That sentiment seems to be actually in opposition to this idea that anything that’s animal-like about a kid is not human.

What was interesting to me is that we surround our kids with all these animal images and stuffed lions and bears and so on, yet no one’s ever really looked at how children conceive of wild animals. We have a lot of research about how a kid might think about their family’s pet dog, for instance, but how does that kid think about a panda bear that they’ll never see?

Rufus, the polar bear rocking horse, by Maclaren Nursery.

There was one set of studies done in the 1970s that interviewed a lot of grade school kids about how they thought about wildlife, and the answers were pretty much exactly the opposite of what we like to imagine. The older kids get, the more compassionate they feel toward the wild animals. The younger kids were just horrified and scared and felt very threatened by the animals—which makes perfect sense, of course, because they’re helpless little kids.

In many ways, that’s actually the more “wild” response: the kids are behaving like animals, in the sense that they’re only looking out for their own interests.

I thought that was really funny, in fact, because the whole book came out of a very genuine feeling that it’s really sad that my daughter is going to grow up in a world without polar bears, and, at the same time, a complete inability to understand why that should be so or to rationalize that feeling. After all, she doesn’t interact with polar bears now. Why should she care about polar bears? I think part of that originally inexplicable sense of sadness comes from a romantic place where we want to see children and wild animals as part of the same culture—a culture that’s not us.

Manaugh: What’s interesting, I suppose, with the children, is that we want a kind of animal-like, wild innocence, but only until they reach a certain age.

Mooallem: That actually mirrors this cycle that I write about with a lot of wildlife where we love wild animals when they are helpless and they don’t threaten us, but then we vilify them when they inconvenience us or aren’t under our control.

My daughter is about to turn five, and I’m really glad she doesn’t bite me any more when she gets angry! At the same time, it fills me with a very profound joy when I see her stalking a butterfly on Bernal Hill, because somehow I want her to be connected to that more pure idea of nature. I think that we love wildness and we love that kind of animal nature when it doesn’t inconvenience us—when it’s not biting us in the leg.

California Department of Fish and Wildlife shot three tranquilizer darts into this celebrity mountain lion, found in a Glendale-area backyard, before removing it to Angeles National Forest. Photo: NBC4.

There’s this study in Los Angeles that showed that when there were almost no mountain lions left, people would celebrate them as a part of their natural heritage—the good wild—but then, when mountain lion populations made a bit of a comeback and the lions started intruding into the city and eating pet dogs, people’s attitudes changed and mountain lions were seen as vicious murderers—the bad wild. There is a kind of fickleness: we want it both ways.

In the book, I quote Holly Doremus, who is a brilliant legal scholar based here in Berkeley, who says that we’ve never really decided—or maybe even asked—how much wild nature we need and how much we can accept.

Twilley: What that question brings up to me, too, is the idea of an appropriate context for wildness. One of Rudi Mattoni’s first projects was breeding the Palos Verdes blue butterfly, which was thought to be extinct after its last habitat was covered by a baseball diamond, but was then rediscovered in a field of underground fuel tanks owned by the Department of Defense. I was curious about both the idea of control and the idea of pristine nature, and how both concepts are embedded in our assumptions about wildness.

Mooallem: Right. Pigeons are wild—but they annoy us. Cockroaches are wild. We don’t romanticize or preserve the wild animals that live alongside us and invade spaces that we think of as ours—we exterminate them.

As far as control goes, we want to have our cake and eat it, too. We want something that has nothing to do with us—something that has free rein and that can surprise us and thrill us—but we only want the positive side of that equation. We don’t want the wolves eating our cattle or the sea otters getting in the way of the fishermen. That’s certainly behind some of the extreme lengths we go to in order to create the right context for the animals and to keep them within a certain area that we’ve decided is appropriate for them.

The point of the book is that we’re only going to see more and more examples like the Palos Verde blue and the Lange’s Metalmark, where the last hope for a species is in a seemingly hopeless place. There are only going to be more industrial landscapes—it’s unavoidable. Travis Longcore, who is an urban conservation scientist that I spoke with for the book, makes a really good point, which is that we have to get away from what he calls Biblical thinking—that you’re either in the Garden of Eden or the entire world is fallen. He heads the organization that’s behind a lot of the Antioch Dunes butterfly recovery, and he makes a point of trying to celebrate the wildness of places that make most of us feel queasy.

I think that’s important—I’m not suggesting that we give up on the romantic idea of the places that do seem “pristine,” but I think that we need to be a little more flexible and we need to find the joy and the beauty in those other sorts of places, too.

Twilley: You chose to start the epilogue with a story that seems emblematic: the “species in a bucket” story. What about that story summed up these complex themes you were tackling in the book?

Mooallem: The “species in a bucket” story is about a fish biologist named Phil Pister and a little species of fish called the Owens pupfish. Back in the 1960s, in the Owens Valley, Phil Pister was part of the group who had rediscovered the Owens pupfish—it had been presumed extinct, but he found it living in a desert spring.

Owens Valley pupfish. Photo: UC Davis; Phil Pister in front of the BLM Springs where the fish still flourishes today. Photo: Chris Norment.

One summer—I think it was 1964—there was a drought, and this one desert spring where the fish lived was drying up. Pister ran out there with some of his California Department of Fish & Wildlife buddies, and they moved the fish to a different part of the spring where the water was flowing a little bit better and the fish would have more oxygen.

He sent everyone home thinking it was a job well done, but then, after nightfall, he realized that it wasn’t working. Scores of fish were floating belly up. So he made a snap decision. He got some buckets from his truck, he put all the fish he could into the buckets, he carried them back to his truck, and he drove them across the desert to this other spring where he knew the water was deeper and that they’d survive.

I was drawn to that story because I heard it a few different times and, originally, to be honest, I just didn’t think it was true. It sounded like this almost Biblical, heroic story of a man alone in the desert—and it was always told to me in that way, too. People stressed how miraculous it was and how noble he was, carrying these two buckets full of fish across the desert to save the species. It was almost too perfect of a metaphor—here we are with the fate of all these species in our hands—but it also turned out to be true. I actually went down to Bishop to meet Phil, and he’s a phenomenal guy.

I thought that story should start the epilogue for two reasons. In part, I liked the story for all the same reasons that I thought it wasn’t true—there’s this timelessness to it. A lot of the book is about adding layer after layer of complexity, so the reader feels less and less certainty. It’s not a book that moves toward an answer—it’s more of a book that unravels all the answers that we thought we already knew. So there was something really refreshing and absolving to just take it back to this one man with a bucket, saving a species.

The other reason is that I thought it was a good illustration of this human compulsion to help, which is the underlying driver of so many of the stories in the book. There was something really nice about Phil’s story, in that it didn’t even strike him as that remarkable at the time. Later it did, of course, and he’s written about it, pretty eloquently. But I thought his story got at the fact that we just can’t not do this sort of thing. We can’t not try to solve a problem when it’s in front of us. I found that there’s a real dignity in that.

Even the people I met who were the harshest critics of Endangered Species preservation wanted to help—they just thought the way it was being done was ridiculous or that the politics are ridiculous.

Brooke Pennypacker in costume, with the juvenile whooping cranes. Photo: Operation Migration.

Chairs set up for "craniacs" hoping to witness an Operation Migration flyover, Gilchrist County, Florida. Photo: Jon Mooallem.

Take, for example, all these people up and down Operation Migration’s route who donate their property to let the pilots stay on their land with the whooping cranes. They’re not people that you would think of as environmentalists, but they’re really grateful for this opportunity to help—there’s no red tape, there’s no government surveyor coming in to check their land for endangered species, just a simple way to make a difference for this one species.

I also liked the idea of pairing Phil Pister’s story with Brooke Pennypacker, one of the Operation Migration pilots. For Brooke, this is not a one-night-with-a-bucket deal: he flies a little plane in a bird costume in front of whooping cranes for five months of the year, and then he migrates back with them on land. His whole life is given up to this effort, for the foreseeable future. It’s not a simple problem he’s trying to solve. I found him on a pig farm, where he’d been exiled due to bureaucratic squabbling, and he had FAA inspectors coming to check out his plane. He was just beset by complexity and he was so in touch with the potential futility of it all. He was willing to accept that maybe everything he’s doing isn’t going to make a difference.

Juvenile whooping cranes getting acquainted with the microlight, pre-migration. Photo: Doug Pellerin, via Operation Migration.

That’s the complete opposite of Phil Pister walking across the desert just thinking that all he has to do is move these fish over here and they’ll be fine. In the span of 50 years, we’ve gone from one scenario to the other. But Brooke is doing it because he feels the exact same way Phil did. Brooke told me that he got involved with Operation Migration because it was as if someone had a flat tire on the side of the road and he had a jack in his car. He saw a problem and he knew that he could pull over and help. That’s where it all starts from.

Manaugh: This is a hypothesis in the guise of a question. Most people’s experience of wildlife nowadays is in the form of roadkill or perhaps squirrels nibbling through the phone cable or raccoons in their backyard. It’s very unromantic—whereas pets seem to be getting more and more exotic and strange. There’s a boom in people owning lions or boa constrictors or incredibly rare tropical birds as pets. I’m curious what you think about the role of the pet in terms of our relationship with wild animals, and whether we are turning to increasingly exotic pets in order to replace the wildness we find missing in nature itself.

Mooallem: That’s never occurred to me, but it’s a brilliant point. I’m ashamed to say that I don’t really have a lot to say about pets. I’ve never really had a pet.

My sense is that when you have a dog, the dog is your buddy. Even though it’s a dog, you more or less relate to it as a person. I think that, in that sense, pets are sort of boring to me. But this idea that we’re trying to get our exotic thrills from a pet monkey is interesting. I’ll have to give that some thought.

The stories that interest me as a writer are ones in which people are trying to respond appropriately to something where it’s not clear what the appropriate response is. For a while, I was writing a lot about the dilemma of recycling—you’re holding this can, and you don’t know whether putting it in the recycling bin is smart or whether it just gets shipped off to China. There’s that drive to do the moral thing, but most of us are completely clueless as to what the right thing might be, because of the complexity of the issues.

Wild animals are the perfect example of that kind of situation, because they can’t really tell us what they need—they’re just this black box that our actions get fed into. For some reason, probably some deep Freudian problem, that challenge of trying to do the right thing but ultimately just banging your head against the wall to figure it out is really appealing to me. I really relate to it.

I guess that’s why I’m not really that interested in pets, either. You come to feel that you understand your pet, even if you don’t. There’s not that tension or urge to solve the problem that you get with otters or wolves or buffalo. You house-break your pet and then it’s over.

Manaugh: I wonder, though, if that’s not part of the appeal of getting an exotic animal species as a pet—the promise and the thrill of not understanding it.

Mooallem: At the same time, that’s a feeling that you’ll eventually get bored or annoyed with, and you’ll end up abandoning the pet. I just read that the government is setting up unwanted tortoise drop-offs for owners who want to abandon their pets, just like babies at fire stations. Apparently in some states—Nevada and a few others—there are dozens of desert tortoises being left by their owners by the side of the road.

Desert tortoises at a sanctuary for abandoned pet tortoises in southwest Las Vegas. Photo: Jessica Ebelhar, Las Vegas Review-Journal.

When a pet monkey goes nuts and the owner gives it up, we tend to look at it as a failure of pet ownership, but maybe they actually wanted that feeling of not understanding the animal, at least at first. It’s an interesting theory.

Twilley: Another group of people who would seem to have a very different but equally complex relationship to wild animals is hunters. That’s a whole segment of Americans who seem to be less troubled about what their relationship should be with wild animals, yet who often end up being at the forefront of conservation movements, in order to save the landscapes in which they hunt. The division is interesting—it seems philosophical, but it’s also maybe class-based?

Mooallem: It’s geographic, definitely. But you’re right: a lot of the stereotypes around hunters break down when you see all the really creative conservation projects that are supported, or even spearheaded, by people who we might normally think of as redneck hunters. The lines are just not clearly defined. You also choose your species—some people are more sympathetic to one species than they are to others.

The other point I was trying to make with the book is that conserving a species or celebrating a species is just another way to use the species. Conservationists always talk about utilitarian values and aesthetic values, but, to me, it’s all the same thing. Some of us want salmon in the Columbia River because we want to fish them, and some of us want salmon there because it’s part of America’s natural glory, or because we’ll feel guilty if they go away. But, in all of those reasons, the salmon are serving human needs.

Those different reasons really come to the surface when a species rebounds. Right now, there’s a huge fight up and down the sandhill crane flyway. They were all but extinct, yet they’ve come back to the point where they’re annoying farmers, and hunters are saying: “Fantastic! They’re back—now I can hunt them with my son again. Success!” And, of course, then there’s an outcry from the birdwatchers and the conservationists who are saying that that’s not why we brought them back. We brought them back so they could be beautiful, not so they could be shot. But these are still just two groups of people who want something out of the bird.

Manaugh: There’s another book that came out recently called Nature Wars—

Mooallem: Yes, I read that.

Manaugh: The author, Jim Sterba, argues that all of our well-intentioned efforts to protect animals have actually allowed deer and beaver and Canada goose populations to explode, and now they’re bringing down our planes and causing car crashes and tearing up our golf courses and so on. He ends up, to my mind, at least, over-emphasizing the point that we need to become hunters again—that the ecosystem is out of balance precisely because it no longer features human predators.

Roadkilled deer, South Carolina. Photo: John O'Neill.

Mooallem: Preserving these species—whether it’s intentional or whether it’s an unintended consequence of habitat changes, as in the case of deer—is an ecological act, and it’s going to have repercussions that we should take responsibility for dealing with. We forget we’re ecological participants. In fact, if Sterba’s book hadn’t been written, I might be thinking about exactly the same issue now. There are so many cases where it’s the rebound or the resurgence that causes the problem, rather than the decline.

The real fallacy is the “leave no trace” attitude. There is no way you’re not leaving a trace, so it’s better simply to be conscious and thoughtful and to take responsibility for what you’re doing.

Somebody asked me the other day about the de-extinction movement, and I had the same response. I don’t know what I think about actually bringing back passenger pigeons, but I think it’s good that people are talking about being proactive and being creative rather than just trying to pretend we don’t have any power.

Of course, it also makes me nervous—as it should, given our environmental history of unintended consequences, having to find solutions for problems that were caused by our own solutions for other problems that we ourselves most likely caused in the first place.

Detail from the cover of Jon Mooallem's Wild Ones.

This is a surprisingly generous statement, considering that Mooallem has spent the last few years researching a harrowing litany of accidental extinctions and unintended consequences—including a surreal day spent chasing ex-convict Martha Stewart as she and her film crew pursued polar bears across the Arctic tundra—in order to untangle the complicated legal and emotional forces that shape America's relationship with wildlife.

Despite the humor, the stakes are high: half the world's nine million species are expected to be extinct by the end of this century, and, as Mooallem explains, many of those that do survive will only hang on as a result of humans' own increasingly bizarre interventions, blurring the line between conservation and domestication to the point of meaninglessness.

On a foggy morning in San Francisco, Venue met Mooallem for coffee and a conversation that ranged from tortoise kidnappings to polar bear politics. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

• • •

Detail from the cover of Jon Mooallem's Wild Ones.

This is a surprisingly generous statement, considering that Mooallem has spent the last few years researching a harrowing litany of accidental extinctions and unintended consequences—including a surreal day spent chasing ex-convict Martha Stewart as she and her film crew pursued polar bears across the Arctic tundra—in order to untangle the complicated legal and emotional forces that shape America's relationship with wildlife.

Despite the humor, the stakes are high: half the world's nine million species are expected to be extinct by the end of this century, and, as Mooallem explains, many of those that do survive will only hang on as a result of humans' own increasingly bizarre interventions, blurring the line between conservation and domestication to the point of meaninglessness.

On a foggy morning in San Francisco, Venue met Mooallem for coffee and a conversation that ranged from tortoise kidnappings to polar bear politics. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

• • •

The polar bear tourism industry in Churchill, Manitoba, relies on a dozen specially built vehicles called Tundra Buggies that take tourists and their cameras out to see the world's southernmost bear population. Photo: Polar Bears International.

Geoff Manaugh: In the book, you’ve chosen to focus on two very charismatic, photogenic, and popular animals: the whooping crane and the polar bear.

Jon Mooallem: They’re the celebrities of the wildlife world.

Manaugh: Exactly. But there’s a third example, in the middle section of the book, which is a butterfly. It’s not only a very obscure species in its own right, but it’s also found only in a very obscure Bay Area preserve that most people, even in Northern California, have never heard of. What was it about the story of that butterfly, in particular, that made you want to tell it?

Mooallem: I thought it would be really interesting to go from the polar bear, which is the mega-celebrity of the animal kingdom, to its complete opposite—to something no one really cared about—and to see what was at stake in a story where the general public doesn’t really care about the animal in question at all. It turned out that there was a hell of a lot at stake for the people working on that butterfly.

The polar bear tourism industry in Churchill, Manitoba, relies on a dozen specially built vehicles called Tundra Buggies that take tourists and their cameras out to see the world's southernmost bear population. Photo: Polar Bears International.

Geoff Manaugh: In the book, you’ve chosen to focus on two very charismatic, photogenic, and popular animals: the whooping crane and the polar bear.

Jon Mooallem: They’re the celebrities of the wildlife world.

Manaugh: Exactly. But there’s a third example, in the middle section of the book, which is a butterfly. It’s not only a very obscure species in its own right, but it’s also found only in a very obscure Bay Area preserve that most people, even in Northern California, have never heard of. What was it about the story of that butterfly, in particular, that made you want to tell it?

Mooallem: I thought it would be really interesting to go from the polar bear, which is the mega-celebrity of the animal kingdom, to its complete opposite—to something no one really cared about—and to see what was at stake in a story where the general public doesn’t really care about the animal in question at all. It turned out that there was a hell of a lot at stake for the people working on that butterfly.

Lange's Metalmark butterfly (Apodemia mormo langei). Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It’s called the Lange’s Metalmark butterfly, and it’s about the size of a quarter. As you said, it only lives in this one place called Antioch Dunes, which is about sixty-seven acres in total. It is surrounded by a waste-transfer station, a sewage treatment plant, and a biker bar, and there’s a gypsum factory right in the middle that makes wallboard. You can’t even walk across the preserve, actually, because of this giant industrial facility in the middle of it.

In fact, the outbuilding where Jaycee Dugard, the kidnapping victim, was held is just round the corner.

Lange's Metalmark butterfly (Apodemia mormo langei). Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It’s called the Lange’s Metalmark butterfly, and it’s about the size of a quarter. As you said, it only lives in this one place called Antioch Dunes, which is about sixty-seven acres in total. It is surrounded by a waste-transfer station, a sewage treatment plant, and a biker bar, and there’s a gypsum factory right in the middle that makes wallboard. You can’t even walk across the preserve, actually, because of this giant industrial facility in the middle of it.

In fact, the outbuilding where Jaycee Dugard, the kidnapping victim, was held is just round the corner.

Counting butterflies at Antioch Dunes. Photo: Jon Mooallem

It’s a forgotten place. It’s not the sort of place you’d expect to spend a lot of time in if you’re writing a book about wildlife in America.

On top of all that, not only is the butterfly the animal in the book that people won’t have heard of, or that they won’t know much about, but it’s also the one that I didn’t know very much about, going in. Looking back on it, it was somewhat audacious to say in my book proposal that a third of the book was going to be the story of this butterfly, because I really knew almost nothing about it! But it ended up being by far the most fascinating story, for me. That’s at least partly because I had the sense that I was looking at things that no one had ever looked at and talking to people who no one had ever talked to before.

Counting butterflies at Antioch Dunes. Photo: Jon Mooallem

It’s a forgotten place. It’s not the sort of place you’d expect to spend a lot of time in if you’re writing a book about wildlife in America.

On top of all that, not only is the butterfly the animal in the book that people won’t have heard of, or that they won’t know much about, but it’s also the one that I didn’t know very much about, going in. Looking back on it, it was somewhat audacious to say in my book proposal that a third of the book was going to be the story of this butterfly, because I really knew almost nothing about it! But it ended up being by far the most fascinating story, for me. That’s at least partly because I had the sense that I was looking at things that no one had ever looked at and talking to people who no one had ever talked to before.

Jana Johnson leads a captive breeding project for the Lange's Metalmark from inside America's Teaching Zoo, where students in Moorpark College's Exotic Animal Training and Management degree program learn their trade. Photos: (top) Jason Redmond, Ventura County Star; (bottom) Louis Terrazzas, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It also seemed as though, when you’re working in an environment like that on a species that doesn’t get a lot of support or interest, you’re confronting a lot of the fundamental questions of environmentalism in a much more dramatic way. You have to work harder to sort through them, because it’s difficult to make simple assumptions about what you’re doing—that what you’re doing is worthwhile and good—when you don’t have anyone telling you that, and when it looks as hopeless as it looks with the Lange’s Metalmark.

Maybe hopeless is too strong a word—but you can’t transpose romantic ideas about wilderness and animals onto the situation, because it’s just so glaringly unromantic. You can’t stand in Antioch Dunes and take a deep breath of fresh air and feel like you’re in some primordial wilderness. You don’t have that luxury.

The other thing that was interesting about the butterfly story was the fact that it was happening on such a small scale. The butterfly’s always just lived in this one spot—it’s the only place it lives on earth—so you could look at what happened to this small patch of land over a hundred years and meet all the people who came in & out of the butterfly’s story. It was quite self-contained. It was almost like a stage for a play to happen on.

Jana Johnson leads a captive breeding project for the Lange's Metalmark from inside America's Teaching Zoo, where students in Moorpark College's Exotic Animal Training and Management degree program learn their trade. Photos: (top) Jason Redmond, Ventura County Star; (bottom) Louis Terrazzas, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

It also seemed as though, when you’re working in an environment like that on a species that doesn’t get a lot of support or interest, you’re confronting a lot of the fundamental questions of environmentalism in a much more dramatic way. You have to work harder to sort through them, because it’s difficult to make simple assumptions about what you’re doing—that what you’re doing is worthwhile and good—when you don’t have anyone telling you that, and when it looks as hopeless as it looks with the Lange’s Metalmark.

Maybe hopeless is too strong a word—but you can’t transpose romantic ideas about wilderness and animals onto the situation, because it’s just so glaringly unromantic. You can’t stand in Antioch Dunes and take a deep breath of fresh air and feel like you’re in some primordial wilderness. You don’t have that luxury.

The other thing that was interesting about the butterfly story was the fact that it was happening on such a small scale. The butterfly’s always just lived in this one spot—it’s the only place it lives on earth—so you could look at what happened to this small patch of land over a hundred years and meet all the people who came in & out of the butterfly’s story. It was quite self-contained. It was almost like a stage for a play to happen on.

Butterflies on display in cases at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Photo: Venue.

Manaugh: Harry Lange, for whom the butterfly is named, has a great line that seems to sum up so much of the sadness and stupidity in the human relationship with wild animals. He said, after exterminating the very last of the Xerces Blue butterfly: “I always thought there would be more…”

Mooallem: Right—and that was the other extraordinary thing about the butterfly story.

When I started working on the book, I had no idea about the history of butterfly collectors in the Bay Area. Apparently, the Bay Area was a big hotspot for butterflies, because of the microclimates here. It can be ten or fifteen degrees hotter in the Mission District than it is at the beach; there can be fog in some places and not others; and all of this creates a sort of Galapagos Island effect. The whole peninsula is peppered with these different micro-populations of butterflies because of the different microclimates.

Meanwhile, in the early twentieth century, at a time when the Audubon Society and other groups were being founded and there was a turn against the overhunting of species, it still seemed OK and sort of benign to collect butterflies. It wasn’t considered “hunting.” You could transfer all of that ambition to conquer nature and discover new things to collecting butterflies. You’re here at the very end of North America, where the country finally runs out of room, and now you’re starting to run out of animals too, but there were still enough butterflies to collect and name after yourself.

Butterflies on display in cases at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Photo: Venue.

Manaugh: Harry Lange, for whom the butterfly is named, has a great line that seems to sum up so much of the sadness and stupidity in the human relationship with wild animals. He said, after exterminating the very last of the Xerces Blue butterfly: “I always thought there would be more…”

Mooallem: Right—and that was the other extraordinary thing about the butterfly story.

When I started working on the book, I had no idea about the history of butterfly collectors in the Bay Area. Apparently, the Bay Area was a big hotspot for butterflies, because of the microclimates here. It can be ten or fifteen degrees hotter in the Mission District than it is at the beach; there can be fog in some places and not others; and all of this creates a sort of Galapagos Island effect. The whole peninsula is peppered with these different micro-populations of butterflies because of the different microclimates.

Meanwhile, in the early twentieth century, at a time when the Audubon Society and other groups were being founded and there was a turn against the overhunting of species, it still seemed OK and sort of benign to collect butterflies. It wasn’t considered “hunting.” You could transfer all of that ambition to conquer nature and discover new things to collecting butterflies. You’re here at the very end of North America, where the country finally runs out of room, and now you’re starting to run out of animals too, but there were still enough butterflies to collect and name after yourself.

The Xerces Blue is the first butterfly in America known to have gone extinct due to human disturbance. Photo: Andrew Warren/butterfliesofamerica.com

The story of Xerces Blue, which is the butterfly that Lange thought there would always be more of, is just incredible. Back then, past 19th Avenue, it was all sand dunes. I actually met a friend of Lange’s, named Ed Ross, who was a curator at the California Academy of Sciences; he had to be in his late eighties or early nineties.

He told me about growing up as a kid here and taking the streetcar out to 19th Avenue and just getting out with his butterfly net and walking to Ocean Beach over the dunes. Occasionally you’d see a hermit, he said.

The Xerces Blue is the first butterfly in America known to have gone extinct due to human disturbance. Photo: Andrew Warren/butterfliesofamerica.com

The story of Xerces Blue, which is the butterfly that Lange thought there would always be more of, is just incredible. Back then, past 19th Avenue, it was all sand dunes. I actually met a friend of Lange’s, named Ed Ross, who was a curator at the California Academy of Sciences; he had to be in his late eighties or early nineties.

He told me about growing up as a kid here and taking the streetcar out to 19th Avenue and just getting out with his butterfly net and walking to Ocean Beach over the dunes. Occasionally you’d see a hermit, he said.

Richmond Sand Dunes (1890s). Photo: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco, CA, via FoundSF.

Richmond Sand Dunes (1890s). Photo: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco, CA, via FoundSF.

Dunes along Sunset Boulevard, San Francisco (1938). Photo: Harrison Ryker, via David Rumsey Map Collection.

That generation of butterfly nuts who were living in San Francisco in the early twentieth century saw that habitat being erased in front of their eyes.

That backstory really helped to shape my perception of a lot of things in the book by elongating the timescale. It brought up the whole idea of shifting baselines—this gradual, generational change in our accepted norm for the environment—and all these other, deeper questions that wouldn’t have come up if I’d just followed Martha Stewart around filming polar bears, as I do in the first section of the book. It’s a very different experience to zoom out and take in the entirety of a story as I did with the Lange’s Metalmark, which is why I think I enjoyed it so much.

Nicola Twilley: It’s interesting to note that Ed Ross doesn’t actually figure in the book, and that, elsewhere, you allude to several intriguing stories in just a sentence or two—to things like the volunteers who count fish at the Bonneville Dam. Instead, you deliberately keep the focus on the bear, the butterfly, and the bird. But what about all the animals or all the stories that didn’t make it into the book? Were there any particular gems that you had to leave out or that you wish you had kept?

Mooallem: There were tons! The fish counting thing is a perfect example.

Dunes along Sunset Boulevard, San Francisco (1938). Photo: Harrison Ryker, via David Rumsey Map Collection.

That generation of butterfly nuts who were living in San Francisco in the early twentieth century saw that habitat being erased in front of their eyes.

That backstory really helped to shape my perception of a lot of things in the book by elongating the timescale. It brought up the whole idea of shifting baselines—this gradual, generational change in our accepted norm for the environment—and all these other, deeper questions that wouldn’t have come up if I’d just followed Martha Stewart around filming polar bears, as I do in the first section of the book. It’s a very different experience to zoom out and take in the entirety of a story as I did with the Lange’s Metalmark, which is why I think I enjoyed it so much.

Nicola Twilley: It’s interesting to note that Ed Ross doesn’t actually figure in the book, and that, elsewhere, you allude to several intriguing stories in just a sentence or two—to things like the volunteers who count fish at the Bonneville Dam. Instead, you deliberately keep the focus on the bear, the butterfly, and the bird. But what about all the animals or all the stories that didn’t make it into the book? Were there any particular gems that you had to leave out or that you wish you had kept?

Mooallem: There were tons! The fish counting thing is a perfect example.

Janet the fish counter, hard at work. Photo: Jon Mooallem.

I spent a day at the Bonneville Dam, and it was completely surreal. I barely touch on it in the book, but the question of how to get fish around the dam is a really interesting design problem. There have been different structures that were built and then shown not to work, and so they’ve had to adapt them or retrofit them, and that’s ended up creating all new problems that need to have something built to solve them, and so on.

The government has actually moved an entire colony of seabirds that were eating the fish at the mouth of the river. The fish that got through the dam would get to the mouth of the Columbia River, but then the double-crested cormorants would eat them all. So the government picked up the birds and moved them to another island in the river.

I felt as though, normally, when you hear about these kinds of stories, you just scratch the surface. We’re so used to hearing endangered species stories in very two-dimensional, heroic ways, where so-and-so is saving the frog or whatever, and I just knew that it couldn’t be that easy. If it was that straightforward—if you could just go out and pull up some weeds and the butterfly would survive—it wouldn’t be very meaningful work. That was the space I really wanted to get into—the muddiness where things don’t work out the way we draw them on paper.

At the same time, I was able to mention a lot of these bizarre stories—but, as you say, almost as an aside. Each one of those things could have been a much longer, deeper story. Take, for example, the “otter-free zone,” which was this incredible saga: the government was reintroducing otters in Southern California and, because of complaints from fishermen and the oil industry, they needed to control where the otters would swim. A biologist would have to go out in a boat with binoculars to look for otters that were inside the otter-free zone and, if he saw them, he’d have to try to capture them when they were sleeping and move them. It was just a hilarious, miserable failure. I spent a lot of time reporting on that—talking to the biologist and hearing what that work was actually like to have to do—yet, in the end, I only mention it. But I know there’s a deeper story there.

Janet the fish counter, hard at work. Photo: Jon Mooallem.

I spent a day at the Bonneville Dam, and it was completely surreal. I barely touch on it in the book, but the question of how to get fish around the dam is a really interesting design problem. There have been different structures that were built and then shown not to work, and so they’ve had to adapt them or retrofit them, and that’s ended up creating all new problems that need to have something built to solve them, and so on.

The government has actually moved an entire colony of seabirds that were eating the fish at the mouth of the river. The fish that got through the dam would get to the mouth of the Columbia River, but then the double-crested cormorants would eat them all. So the government picked up the birds and moved them to another island in the river.

I felt as though, normally, when you hear about these kinds of stories, you just scratch the surface. We’re so used to hearing endangered species stories in very two-dimensional, heroic ways, where so-and-so is saving the frog or whatever, and I just knew that it couldn’t be that easy. If it was that straightforward—if you could just go out and pull up some weeds and the butterfly would survive—it wouldn’t be very meaningful work. That was the space I really wanted to get into—the muddiness where things don’t work out the way we draw them on paper.

At the same time, I was able to mention a lot of these bizarre stories—but, as you say, almost as an aside. Each one of those things could have been a much longer, deeper story. Take, for example, the “otter-free zone,” which was this incredible saga: the government was reintroducing otters in Southern California and, because of complaints from fishermen and the oil industry, they needed to control where the otters would swim. A biologist would have to go out in a boat with binoculars to look for otters that were inside the otter-free zone and, if he saw them, he’d have to try to capture them when they were sleeping and move them. It was just a hilarious, miserable failure. I spent a lot of time reporting on that—talking to the biologist and hearing what that work was actually like to have to do—yet, in the end, I only mention it. But I know there’s a deeper story there.

Sea-otter in Morro Bay, California, just north of the former otter-free zone. Photo: Mike Baird.

In fact, there’s a section of the book where I rattle off a bunch of these examples—there’s the project to keep right whales from swimming into the path of natural gas tankers, and there’s the North Carolina wolves and their kill-switch collars, and so on. Each one of those is its own Bonneville Dam story—its own complicated saga of solutions and newer solutions to problems that the original solutions caused. You could really get lost in that stuff. I did get lost in all that stuff for a long time.

This is my first book, of course, and I feel as though that’s the joy and the luxury of a book—that you do have the time and space to get lost in those things for a little while.

Manaugh: It’s funny how many of those kinds of stories there are. I remember an example that Liam Young, an architect based in London, told me. He spent some time studying the Galapagos Islands, and he told me this incredible anecdote about hunters shooting wild goats, Sarah Palin-style, from helicopters, because the goats had been eating the same plants that the tortoises depended on.

BBC Four footage of the Galapagos Island goat killers.

But, at one point, some local fishermen were protesting that the islands’ incredibly strict eco-regulations were destroying their livelihood, so they took a bunch of tortoises hostage. What was funny, though, is that all the headlines about this mention the tortoises—but, when you read down to paragraph five or six, it also mentions that something like nineteen scientists were also being held hostage. [laughter] It was as if the human hostages weren’t even worth mentioning.

Mooallem: [laughs] Wow. That reminds me of one story I saw but never followed up on, about some fishermen in the Solomon Islands who had slaughtered several hundred dolphins because some environmental group had promised them money not to fish, but then didn’t deliver the money.

Twilley: When you invest an animal with that much symbolic power, the stakes get absurdly high.

Mooallem: Exactly—look at the polar bear. Of course, the polar bear has lost a lot of its cachet. I don’t know whether you saw the YouTube video that Obama put out to accompany his big climate speech in June, but I was surprised: there wasn’t a single polar bear image in it. It was all floods and storms and dried-up corn. Four years ago, there would have definitely been polar bears in that video.

Today, though, the polar bear is just not as potent a symbol. It’s become too political. It doesn’t really resonate with environmentalists anymore and it ticks off everyone else. What’s amazing is that it’s just a freaking bear, yet it’s become as divisive a figure as Rush Limbaugh.

Sea-otter in Morro Bay, California, just north of the former otter-free zone. Photo: Mike Baird.

In fact, there’s a section of the book where I rattle off a bunch of these examples—there’s the project to keep right whales from swimming into the path of natural gas tankers, and there’s the North Carolina wolves and their kill-switch collars, and so on. Each one of those is its own Bonneville Dam story—its own complicated saga of solutions and newer solutions to problems that the original solutions caused. You could really get lost in that stuff. I did get lost in all that stuff for a long time.

This is my first book, of course, and I feel as though that’s the joy and the luxury of a book—that you do have the time and space to get lost in those things for a little while.

Manaugh: It’s funny how many of those kinds of stories there are. I remember an example that Liam Young, an architect based in London, told me. He spent some time studying the Galapagos Islands, and he told me this incredible anecdote about hunters shooting wild goats, Sarah Palin-style, from helicopters, because the goats had been eating the same plants that the tortoises depended on.

BBC Four footage of the Galapagos Island goat killers.

But, at one point, some local fishermen were protesting that the islands’ incredibly strict eco-regulations were destroying their livelihood, so they took a bunch of tortoises hostage. What was funny, though, is that all the headlines about this mention the tortoises—but, when you read down to paragraph five or six, it also mentions that something like nineteen scientists were also being held hostage. [laughter] It was as if the human hostages weren’t even worth mentioning.

Mooallem: [laughs] Wow. That reminds me of one story I saw but never followed up on, about some fishermen in the Solomon Islands who had slaughtered several hundred dolphins because some environmental group had promised them money not to fish, but then didn’t deliver the money.

Twilley: When you invest an animal with that much symbolic power, the stakes get absurdly high.

Mooallem: Exactly—look at the polar bear. Of course, the polar bear has lost a lot of its cachet. I don’t know whether you saw the YouTube video that Obama put out to accompany his big climate speech in June, but I was surprised: there wasn’t a single polar bear image in it. It was all floods and storms and dried-up corn. Four years ago, there would have definitely been polar bears in that video.

Today, though, the polar bear is just not as potent a symbol. It’s become too political. It doesn’t really resonate with environmentalists anymore and it ticks off everyone else. What’s amazing is that it’s just a freaking bear, yet it’s become as divisive a figure as Rush Limbaugh.

From "Addressing the threat of Climate Change," a video posted on the White House YouTube channel, June 22, 2013.

Manaugh: Speaking of politics, it feels at times as if the Endangered Species Act—that specific piece of legislation—serves as the plot generator for much of your book. Its effects, both intended and surreally unanticipated, make it a central part of Wild Ones.

Mooallem: It really does generate all the action, because it institutionalizes these well-meaning sentiments, and it makes money and federal employees available to act on them. It amps up the scale of everything.

The first thing that I found really interesting is the way in which the law was passed. It was pretty poorly understood by everyone who voted on it. The Nixon administration saw it as a feel-good thing. It was signed in the doldrums between Christmas and New Year’s, almost as a gift to the nation and a kind of national New Year’s resolution rolled into one. And it was passed in 1973, as well, during both Vietnam and Watergate, so the timing was perfect for something warm and fuzzy as a distraction.

But most people never read the law and they didn’t realize that some of the more hardcore environmentalist staff-members of certain congressmen had put in provisions that were a lot more far-reaching than any of the lawmakers imagined. Nixon didn’t understand that it would protect insects, for example. It was really just seen as protecting charismatic national symbols, in completely unspecified, abstract ways.

From "Addressing the threat of Climate Change," a video posted on the White House YouTube channel, June 22, 2013.

Manaugh: Speaking of politics, it feels at times as if the Endangered Species Act—that specific piece of legislation—serves as the plot generator for much of your book. Its effects, both intended and surreally unanticipated, make it a central part of Wild Ones.

Mooallem: It really does generate all the action, because it institutionalizes these well-meaning sentiments, and it makes money and federal employees available to act on them. It amps up the scale of everything.

The first thing that I found really interesting is the way in which the law was passed. It was pretty poorly understood by everyone who voted on it. The Nixon administration saw it as a feel-good thing. It was signed in the doldrums between Christmas and New Year’s, almost as a gift to the nation and a kind of national New Year’s resolution rolled into one. And it was passed in 1973, as well, during both Vietnam and Watergate, so the timing was perfect for something warm and fuzzy as a distraction.

But most people never read the law and they didn’t realize that some of the more hardcore environmentalist staff-members of certain congressmen had put in provisions that were a lot more far-reaching than any of the lawmakers imagined. Nixon didn’t understand that it would protect insects, for example. It was really just seen as protecting charismatic national symbols, in completely unspecified, abstract ways.

Nixon signing the Endangered Species Act. AP photo via Politico.