As far back as I can remember, I've loved watching scary movies. I was the kid at the video store who wandered into the horror section and obsessed over the covers of the VHS tapes, while his parents sat patiently waiting in the Disney section, hoping for a more appropriate selection. You might say that, in addition to the consumption of wine and spirits, the ingestion of cinematic terror and gore makes up what's left of my free time. That's why, when our New Zealand wine buyer Ryan Woodhouse told me that we might getting a tiny allocation of Sam Neill's pinot noir, I did a double-take. "You mean the actor Sam Neill?" I asked, my eyes ablaze in response. This was a dream come true. While most people know Sam from his world-famous appearances in Jurassic Park and The Piano, horror-fanatics like myself relish his roles in genre classics like The Omen: Final Conflict, In the Mouth of Madness, and Event Horizon. I must have watched In the Mouth of Madness, an eerie John Carpenter classic from the mid-90s that ran completely under the radar, at least fifty times during high school. "You're telling me Sam Neill makes pinot noir?" I asked Ryan in shock.

"Not just pinot noir; really good pinot noir," he answered.

Ryan reached under his desk and grabbed me a sample of the Two Paddocks pinot noir and poured me a glass. Apparently Sam and his local importer had just dropped by the store to taste the staff on the wines while I was away, and Ryan had saved a bit of the bottle for future tasting. It turns out that when Sam returned home to New Zealand to live in Central Otago, he had brought the Burgundy bug back with him. Living in London for many years, drinking the fine wines of the Cote d'Or had taken its toll on the actor, and he wound up moving right smack in the middle of the most distinctive pinot noir soil in the Southern Hemisphere. In 1993, he planted a few acres of vines nearby and founded Two Paddocks Winery, hoping to create a few hundred cases of delicious red wine for his own consumption. Over twenty years later, he's parcelling out small allocations of his coveted cuvee to fine wine retailers like K&L all over the world.

"So you're telling me that I could talk to Sam Neill about Burgundy and horror movies?" I asked Ryan with a huge smile.

"I think he'd be game," he replied with a grin.

In this edition of Drinking to Drink, we talk about the powerful effects of great Burgundy on the human psyche, being recognized as the antichrist by horror buffs, and how John Carpenter never eats anything but breakfast food from the diner. Previous editions of the D2D series can be found by clicking here, or by visiting the archive in the right hand margin of this page.

David: Have you always been into wine, or was this an interest that took hold later in life?

Sam: My family actually had a wine and spirits business for 150 years, so my roots are in alcohol. When I grew up there was always wine on the table at dinner. As far as my interest in good wine, that probably didn’t start until I was around thirty. Before that it was just plain alcohol, I think (laughs). Pretty much any alcohol would do. I think it coincided with me becoming more successful in my career as an actor, which meant I had a little more money in my pocket and I could afford to drink things that were less damaging, and more rewarding.

David: I didn’t realize you came from a family booze business. What did your parents do exactly?

Sam: Neill and Company imported wines and spirits from overseas to New Zealand; primarily from France and from Scotland. It was primarily whisky, brandy, and table wine. They were also general merchants, but their principle business was wine and spirits. They had very good connections in Bordeaux, and they had very a good-selling whisky. But people in those days weren’t particularly interested in wine in New Zealand, so it was pretty unusual to see a bottle of wine on the table.

David: But that was normal for you.

Sam: It was normal in our house, yes.

David: Did you reject that growing up, or did you embrace it? Did you see enjoying alcohol as something your parents did that you wanted to get away from possibly, or were you learning about it from a young age?

Sam: By the time I left home—which was as soon as I possibly could because I wanted to be independent—I was impoverished. At that point, I drank whatever I could afford mostly.

David: How old were you when you left?

Sam: I was about nine or ten. I went to boarding school, and then the university. The last time I really lived at home I was quite young, so when I started drinking I was at school, I’m ashamed to say (laughs). But I’ve never been a heavy drinker. I’ve never been in danger of being an alcoholic, I don’t think.

David: Where were you in your acting career when you started taking more of an appreciation in wine?

Sam: It was probably about the time I got to London. I did the third of The Omen films and I was beginning to earn some decent money. James Mason, who was a great friend and a mentor to me and who loved good food and wine, took me to some excellent restaurants where I ate like I had never eaten before; and drank wines that I had never ever imagined. One of those dinners was extremely memorable because we had Burgundy, and I had never heard of it. I didn’t know what it was, but it was one of those light bulb moments, you know? I was on the road to Damascus.

David: I’ve been there. What was the wine, do you remember? Do you remember what stood out for you?

Sam: I wouldn’t have been able to articulate it at the time, but I had never drank anything like it. I wanted to understand it and to know more about it. I’d like to think it was a Gevrey-Chambertin, but I couldn’t swear to it. It had all these things that I had never tasted in life before. It had integration, depth, complexity, and a long finish—all things that I take as required these days! But I had never experienced them before that.

David: And what happened from there? You started looking for more wines like that?

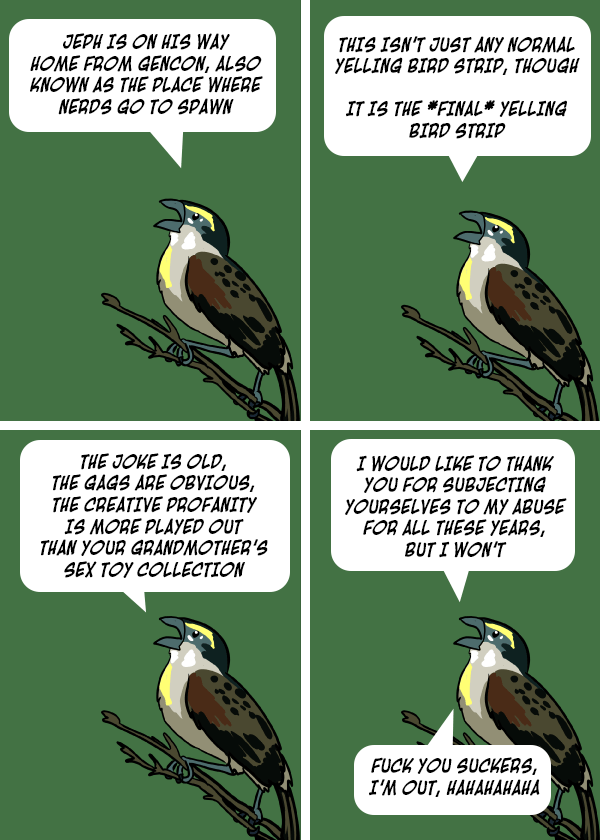

Sam aboard the spaceship Event Horizon

Sam aboard the spaceship Event Horizon

Sam: Then I found myself living in London and there was a great wine shop down the road where they knew I was interested in Burgundy, so they would recommend things each time I came in. I started to learn my way around the region. I wasn’t on to it right away, however, I was sort of confused by the Côte d’Or. I thought it might be a place where you’d put your Bordeaux on a beach. It sounded like somewhere a lot sunnier than Burgundy. So it took me a while, and I still have quite a lot to learn about Burgundy, to be honest.

David: I think we all do. How did it work out for you, living in London, while working in the American film industry? Did that make it more difficult?

Sam: My career became more Euro-centric rather than American-centric, I guess. I think looking back the majority of my career has been either in Europe or Australia. I might have done more work in the states if I had been based out of Los Angeles, but I ended up in London and enjoyed myself; met a girl, all that usual stuff (laughs).

David: That’s great you were able to do it that way. I often wish I could live in London and still keep my job at K&L. That would be my dream! Maybe that’s why as an actor you have one of the most interesting and eclectic careers. You’ve been in huge blockbusters like Jurassic Park—which is now big again—and you’ve also made quite a career in horror. You’re in two of my all-time favorite horror movies: In the Mouth of Madness and Event Horizon. At the time, for me, those were movies I watched on repeat, over and over. In fact, the original name of my band in high school was “Sutter Cane” after Jürgen Prochnow’s character in that film. I was obsessed with John Carpenter back then. What was it like working with him, by the way?

Sam: I like John a lot. I actually did another film with him as well: Memoirs of an Invisible Man. We got on very well. There’s something about people who make horror films and films that are rather violent: they’re always the mildest, kindest, quietest people you could meet. John’s a bit like that. He’s the last person you would expect to be the horror master.

David: Did you ever get to have a drink with him?

Sam: I honestly can’t remember John drinking at all. He only eats breakfast; that’s all he eats. He will not go to fancy restaurants; he hates them. He just likes diner food, basically. He likes bacon, eggs, and muffins—that kind of stuff. That’s all he eats. He doesn’t have any interest in good food (laughs).

David: Would you say that most actors like to drink though?

Sam: Pretty much most people I’ve worked with are interested in both food and wine. One thing we can say fairly about actors is that—as a generalization—they’re really good company, they’re usually very funny people, and they like to go out and have a good time. In both things that I do—acting and making wine—the most important thing is the people you’re with. The people who are involved with you in the same crazy project. Wine has certainly been like that for me. All these things like terroir, root stock, climate, and viticulture—all these things are important—but the most important component to the making of wine is the people. The most important component of a film or television project is the people. In both, I think I’m very lucky to have found myself with some of the best people you can imagine.

David: You’ve been involved with Two Paddocks—your wine project—since 1993. This is around Jurassic Park time. How did you get involved with growing pinot noir in Central Otago? What was the motivation?

Sam: As I was saying earlier, I had become more interested in pinot noir, and then I found that it could be grown successfully in Central Otago, which is where I live. It seemed too crazy of a coincidence that not only was it possible to live in the best place in the world, but also to produce the best wine in the world there. It seemed like a no-brainer. I had a little spare cash in my back pocket and I started with only a few humble acres in a very unlikely spot. Four years later we had our first vintage—in 1997—and we realized that this unlikely spot was the sweet spot. I thought this is probably enough, I’ll just leave it at that. I think we were producing in those days something like 600 cases a year, and that seemed to be plenty; more than I could drink.

David: Were you selling it outside of New Zealand, or was this a local thing with friends and family?

Sam: We got up to about 800 cases before we started going strong. After that it was like I had been bitten by a big bug. In 1998, having seen those results, I found another sweet spot at the other end of the region, and I thought, “I want to double production,” so I planted another five acres. Now it’s four vineyards, so what started as a very tiny project has become a little less tiny. We’re always going to be very limited in our production, and we allocate our wine very sparingly. I think we’re probably up to about 8,000 cases a year, and—of that—there’s probably only 1500 that are from our premium wines. Those are the ones we direct towards you guys—towards K&L.

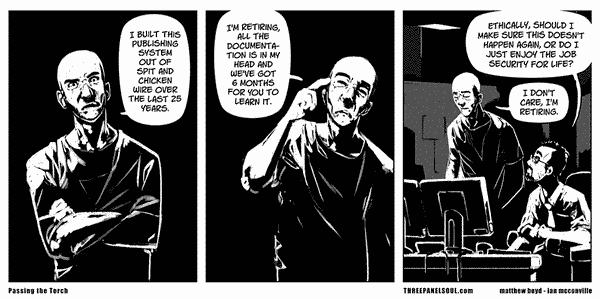

Sam being restrained from the mouth of madness.

Sam being restrained from the mouth of madness.

David: Other than the fact that it’s your project, what’s your favorite part about your wine? What’s most enthralling?

Sam: I don’t pretend to be in any way some kind of an expert. I know a lot more than I used to—when we started I knew nothing at all about winemaking. But my principle directive to the people who work with me is: I’m interested in restraint. I’m not at all interested in big, loud-mouthed, new world styles. While we don’t suppress that exuberance in the fruit, we do use restraint in the vineyard, as well as in the winery. What’s been very pleasing to me is that we produce what I think is subtle, profound, and beautiful wine, and it’s nice when other people agree with me on that (laughs). That gives me great pleasure.

David: It’s clear from talking to you, and having tasted the wines, that you have a real passion for wine and for wines of real delicacy and nuance—like Burgundian wines, for example. Do you find that being a celebrity ever hinders that message? Like wine retailers don’t take the project as seriously because you’re a famous actor?

Sam: I think that’s always going to happen, so that’s the first elephant I shoot when I walk into the room. It’s also easily done because—first of all—I’ve never really been a celebrity. You don’t see me in magazines, my life is private, my family lives an obscure and private life, and I think it’s evident to people in the wine world that I’m not just putting my name on a label. This is something that I’ve been committed to for twenty-three years; that I started from scratch. I’m still the lieutenant at the head of my own little army.

David: Right, you were involved with Two Paddocks before people even knew wine was being made in New Zealand, let alone world-class wine. I think with the work that Ryan (Woodhouse) is doing, and the work that growers like yourself are doing, to bring these wines to a new audience, for the first time ever you’re seeing Burgundy drinkers crossover and accept what’s going on down there. I know that’s been the case for me—personally speaking. And it’s a clear answer: it’s because it tastes better. As a wine geek you know these heralded vineyard names—Richebourg, Echezeaux, Chassagne-Montrachet—that have so much romanticism to them. But when I do side-by-side tastings these days and I evaluate purely on flavor, I’m finding that some of the best pinot noirs in our store are coming from New Zealand. Not just good wines, but some of the best wines in the world.

Sam: And put the price-points up against each other. It’s interesting how that works out (laughs).

David: Right! The prices are almost too good to be believed sometimes. It’s almost difficult to explain to customers because they think you’re under-selling them; like the wines can’t be world-class if they only cost $20 or $30. But we convert them eventually. All they need to do is try a bottle.

Sam: Well, we appreciate the missionary work.

David: It’s hard fought! (laughs)

Sam: You’re bringing light to somewhere where there was only darkness before.

David: Speaking of darkness, does everyone who meets you have to make an Omen reference, or a joke about you being the antichrist?

Sam: No, this is probably the first one I’ve had in about three months.

David: (laughs) That’s still pretty recent! It’s funny because you’re in all kinds of other great movies that are not scary and that are serious and well-acted films—like The Piano or The Hunt for Red October—all these critically-acclaimed movies where your acting is on full display.

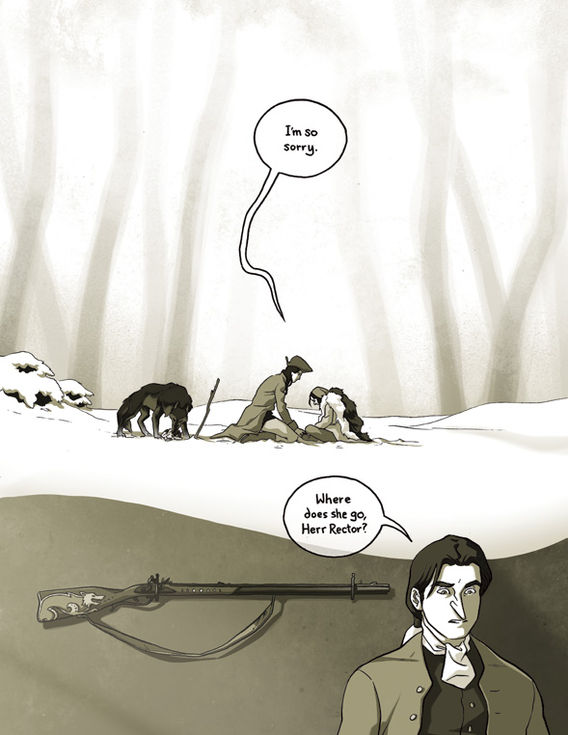

The Two Paddocks estate in Central Otago

The Two Paddocks estate in Central Otago

Sam: I’m in a show on Netflix right now called Peaky Blinders, have you seen that?

David: I just started yesterday! With Cillian Murphy. Although I only got about fifteen minutes in before I had to turn it off and run a quick errand.

Sam: I’m pretty scary in that.

David: I haven’t made it to you yet. I just saw him trot into town on the horse, and then my phone rang.

Sam: Persist for another couple of minutes and then I turn up. I think you’ll be very afraid.

David: I’m still afraid of Event Horizon! My wife can’t even look at that film anymore because it had such an impact on us. I was high school when that came out and I’ll always remember the scene when they get the black hole footage to work and you see what happened on board this ship as they went through the porthole. We all screamed and closed our eyes. Your horror roles were so impressionable for me in my youth. It’s been really cool to be able to talk with you about two of my biggest interests.

Sam: It’s been a long time since I’ve seen those movies, but I think you’ll definitely enjoy Peaky Blinders. It’s a very cool show.

David: Who’s someone you would want to have a drink with if you could choose anyone—living or deceased?

Sam: I think Robert Mitchum was the coolest man who was ever in the movies. I’d like to have met him.

David: How appropriate as he was also in two very scary films: Cape Fear and Night of the Hunter. Which one do you think he was scarier in?

Sam: I liked him in everything that he did. There was something about him that was just beyond cool. I would have liked to have looked at that cool up close and seen what it was.

------------------------

If you are indeed interested in obtaining some of Sam's incredible Two Paddocks wines, we have a very limited supply available on special order below. Less than 50 cases of each wine came into the United States this year, so we're talking extremely limited:

2013 Two Paddocks "The First Paddock" Pinot Noir Central Otago $74.99 - Winemaker's Notes: Sourced from the first twenty-five rows of Clone 5, which was planted in Gibbston at The First Paddock vineyard in 1993. Hand harvested and sorted then a 50% whole bunch indigenous ferment in a dedicated First Paddock French oak cuve. Matured in 30% new French oak with the balance in older wood for an extended 14 months of barrel maturation. Bramble, underbrush, black fruit and spicy aromatics, followed by a mineral infused palate. Ethereal in nature with great mid palate density and drive.

2012 Two Paddocks Estate Pinot Noir Central Otago $49.99 - Two Paddocks flagship Pinot Noir - an estate grown, barrel selection from the three small Neill family vineyards in Central Otago. These vineyards are high-density planted in a range of clonal material and intensively "man-handled" with most vineyard practices carried out by hand. In 2012, this wine was 100% Alexandra fruit from the Redbank and Alex Paddocks sites. Again, each block and clone was picked and fermented separately, with the final blending taking place prior to bottling. Redcurrant, spice and wild black exotic fruit aromatics followed by a strongly driven wine showing great texture and elegance."

2014 Two Paddocks Estate Riesling Central Otago $34.99 - Winemaker's Notes: Two Paddocks Riesling is an estate grown single block selection made from fruit grown at Two Paddocks’ Redbank Vineyard situated in Earnscleugh, Central Otago. As in the vineyard, this wine was handcrafted using traditional methods and bottled early to ensure all the integrity and vitality of the wine was preserved. The soils in this block are well draining schist loam and the vines tend to thrive. Additionally the typically extreme diurnal temperatures experienced in Alexandra (Earnscleugh) between day and night are responsible for both metabolising acidity and retaining an intense flavour profile - all this really means is that we feel a drier wine style is both possible and appropriate. This wine displays pink grapefruit, freshly squeezed limes and spicy loquat aromatics. There is a taut mineral tension feel on the palate, elegant textural weight and very long persistence.

To learn more about Two Paddocks Winery click here.

-David Driscoll

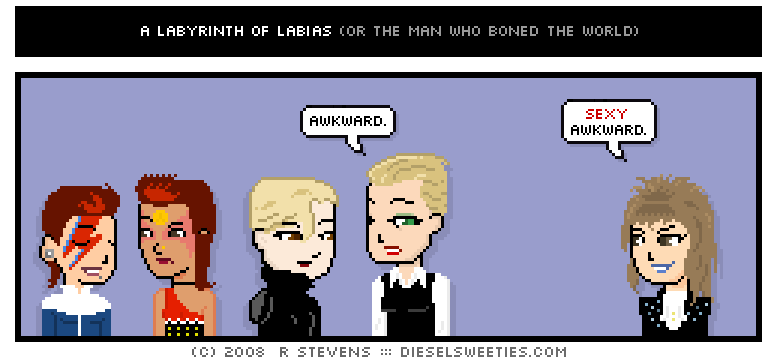

Sam aboard the spaceship Event Horizon

Sam aboard the spaceship Event Horizon Sam being restrained from the mouth of madness.

Sam being restrained from the mouth of madness. The Two Paddocks estate in Central Otago

The Two Paddocks estate in Central Otago

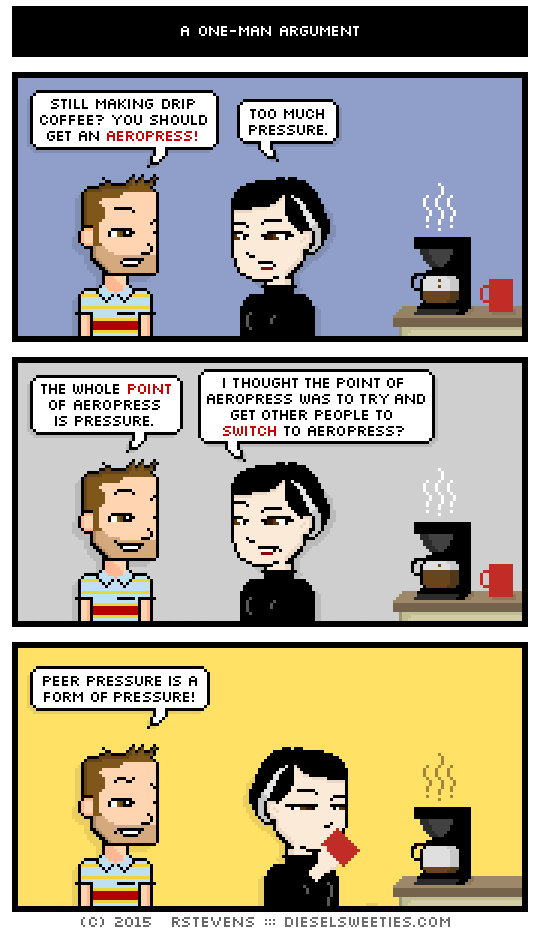

The Windex bill would be astronomical

The Windex bill would be astronomical