anna anthropy

Shared posts

an in-depth look at Doom Episode 1

in the past week i did a few videos looking back at the design of "Knee Deep in the Dead", the original shareware episode of Doom for the game's 20th anniversary (coming up this December). part of my goal was to show why the game, and this episode in particular, has held a strong hold over so many people even 20 years later. i'm not sure whether i really succeeded or not since these videos are fairly off-the-cuff, but hopefully people will get something useful out of them. another part of my goal to show what makes Doom fundamentally different from the current FPS games it's supposed to have spawned. indeed - those games don't really seem have much of anything that comes close to resembling Doom as far as the design of the spaces or the direction of the experience goes. Doom still seems as completely foreign and of another world as it ever has, maybe even moreso.

one thing about the first episode that's clear from both playing back through it and from reading John Romero's design rules (mentioned in the video) beforehand: there's an insistence on a very abstract, but very specific set of rules tailored for the engine the game is made in. the spaces may feel "real" insofaras they are detailed, or their shapes or textures might resemble existing structures in our world - but there's nothing particularly functional about them as architecture outside of the context of the game. and yet you don't feel that at all, as the player. the world makes complete sense once you become acquainted to its language.

and that's what the first episode, in particular, does very well - bringing the player into the language of this very strange, very new kind of experience (when it came out in December 1993) while also providing a surprisingly coherent arc. yet it also subverts the rules it sets out to establish in many subtle but noticeable ways. no design idea is ever exactly repeated in the same way - there's always a new or different twist put on it to stay surprising. if the player starts out in an enclosed, safe area in one map, they'll start out in an open area with enemies in the next. ideas that might seem monotonous on paper come to life in the game because of all the little details and juxtapositions placed in front of you. no part of this episode ever feels like a tutorial or a trudge, because there's no need to tutorialize to get you up to the pace of the story or whatever in the first place. Doom is not trying to be anything other than it is, or tell you it's anything else than what it is. the story is the experience.

that's not to say this is the only valid way to approach to design. it's standard practice in the Doom community to talk shit about Tom Hall or Sandy Petersen's levels for not being as open or elegant or taking advantage of the engine's architecture so self-consciously. a lot of that is they just had less time to work on things, or were part of a compromised, half-realized vision. but that ignores the very strange and interesting ideas that lie in the other two main episodes, even if they don't have the benefit of coming together like in the first. not to mention that sometimes John Romero's maps feel almost silly for their level of interconnected-ness, like he was just trying to make singleplayer levels that doubled as multiplayer levels. but the continual return back to these specific pre-defined design rules create spaces that feel consistent to each other when they might not be otherwise, and i think is a big part of explaining why this first episode still contains the kind of allure it does.

all three videos are here for you to enjoy. look for more videos from me about Doom in the coming month or two, as well as an article about one of my favorite (if not my favorite) Doom mod that's coming soon. enjoy!

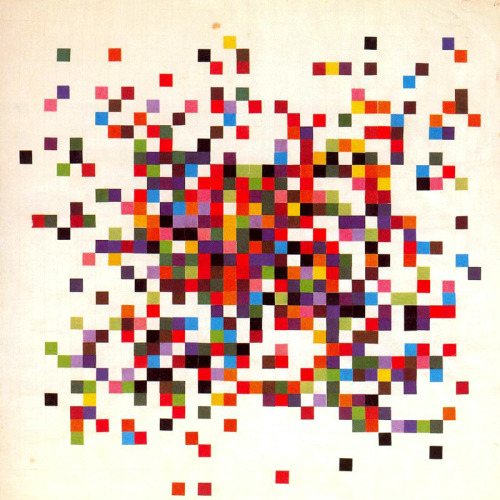

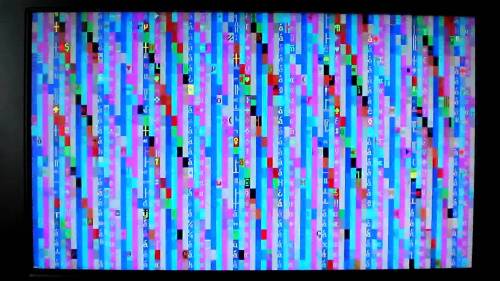

Ellsworth Kelly, Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance, 1951-1953

Ellsworth Kelly, Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance, 1951-1953

The Walker virus (1998) causes an old man, which happens to be a...

The Walker virus (1998) causes an old man, which happens to be a sprite ripped out of the game Bad Street Brawler, to walk across the screen at regular intervals, interrupting any work being done on the PC.

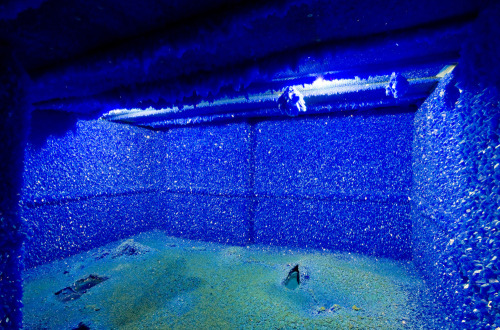

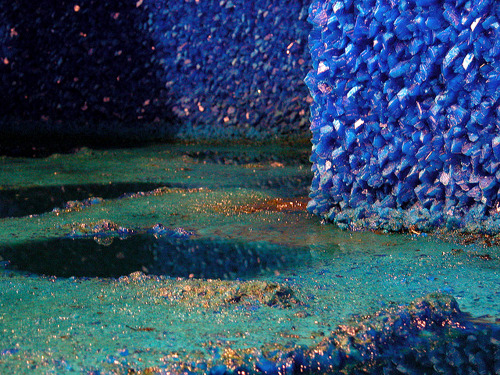

likeafieldmouse: Roger Hiorns - Seizure (2008) A condemned...

Roger Hiorns - Seizure (2008)

A condemned London apartment transformed into a copper sulphate chamber.

"After reinforcing the walls and ceiling and covering them in plastic sheeting, 80,000 litres of a copper sulphate solution were poured in from a hole in the ceiling. After a few weeks the temperature of the solution fell and the crystals began to grow. The remaining liquid was pumped back out and sent for special chemical recycling."

Bones (1997) is a DOS trojan which shows a skull.It goes away...

Bones (1997) is a DOS trojan which shows a skull.It goes away when the computer is restarted.

uvic talk: what are games good for?

I gave this talk at the University of Victoria on September 18, 2013. I’ve also included a further reading list below the talk itself.

Lately I find myself in something of a strange position.

My background isn’t in games or software, it’s in the social sciences. But a little over a year ago I made a game called LIM – it’s about violence and liminality. People seemed to like it, and I liked making it, so I started making more – since then I’ve made and released around a dozen small pieces, and my work has been featured on sites like Polygon and exhibited at Games for Change, the Allied Media Conference, and in a couple of weeks, a show about parody and games in Paris.

Since then I’ve frequently asked myself: why games?

I’m an artist who is primarily interested in producing work that is useful to other marginalized people. And making games for me is often experienced as grappling with a set of tools and systems that I only partially understand. So what do games have to offer me, or anyone else interested in this kind of work?

One obvious answer is that digital games are kind of a big deal at the moment. Darius Kazemi, in a talk titled “Fuck Videogames”, pointed out that many designers see games as exceptional compared to other mediums; that they believe that games have more potential than forms like static visual art, poetry, or film; and as a result, default to game production as their primary form. Further, he argues that this isn’t usually for sound reasons: it often has to do with the perceived relevance or cache of the medium and a corresponding desire to “innovate” within it or to reap the perceived extrinsic rewards that accrue from the culture and communities that have developed around digital games.

As he puts it, “if you write a blog post about your cat, probably nobody will care. But if you make a GAME about your cat, it’ll get covered on a blog or something!” This is a real dynamic, and while I would argue that it does not necessarily preclude the creation of interesting or useful work, it’s made me reflect on the reasons why I or anyone else should be interested in making games.

Games For Change website, frontpage

That brings us to the question: what are games good for? Increasingly the answer provided by people working in digital games is “everything.” If you believe gamification proponents, “gameful design” can be used to improve institutionalized education, personal fitness, and environmental awareness. And even if you’re critical of the behavioralist assumptions that often accompany these kinds of arguments, there are plenty of cases being made for games as tools for self-expression and for understanding complex psychological and social systems.

As someone who produces games but also works in other forms, I find myself skeptical of many of the claims made about the unique value of the medium. And as a social scientist I find it difficult to resist exploring patterns in the communities that have developed around digital game production. So I want to talk about three overlapping threads that I’ve thought about in my own work and that I’ve seen in others as well – games as social, artistic, and investigative practice. My comments may seem overly critical, and so I want to be clear in stating that my intent is not to discredit the use of digital games for purposes other than entertainment or “fun”, far from it. Rather, I want to examine some of the most common rhetoric around games and offer some observations on their deployment from my position as a relative outsider to digital game production.

Before we get going, I just want to note that my thinking on these topics owes a number of debts to other writers and artists working in and around games, including anna anthropy, Ian Bogost, Matthew Burns, Kat Chastain, Naomi Clark, Paolo Pedercini, Amanda Phillips & Liz Ryerson, and I want to thank them for their support and assistance in developing my work.

Games as Social Practice

Game-o-matic, screenshot

An increasingly common argument about games is that they’re useful in describing complex social phenomena. For instance, this image is from the Game-o-Matic tool, designed to enable the creation of simple newsgames that explore procedural rhetoric and relationships between things. By placing the player within the logic of a system, games are supposed to provide greater insight into the ways in which systems structure decision-making. This is an argument I’ve made myself – I’ve thought that using games about gender and sexuality – like anna anthropy’s dys4ia – in classes on those topics might serve to demonstrate to students the structuring of society along those lines in a way that traditional textual or film narratives might not.

The systems we represent can range from the intrapsychic level to the transnational – the point is to show the ways in which dynamics interact to produce particular outcomes. Highly-visible examples include games like Depression Quest, a game about living with the experience of depression, and Oiligarchy, about making a profit in the oil industry. And I think games often are well-suited to this practice – by engaging players in a system, especially a system in which some of the rules are kept hidden, we can convey the complexity of operating in a structured setting.

A common response to games about social issues is that they “trivialize” the subject matter. This isn’t necessarily the case, though there is perhaps an argument to be made for the ways in which many game systems place the player at a distance from the dynamics.

Depression Quest, screenshot

However, for me the use of digital games as social practice does highlight two aspects of the medium that can be worrisome.

First, games often end up systematizing phenomena – indeed it might be argued that programming itself necessities this systematization to some degree. Of course, this is often our goal. But it can be argued that games oversimplify phenomena like depression by rendering them into a simple system that can be understood and ultimately solved. For instance, Depression Quest is a game which heavily systematizes the experience of depression, turning it into a system with clear inputs and results. The critic Maddox Pratt took a phenomenological approach to the game, arguing,

“By claiming depression has a clear system, and designing a system around it in which players are encouraged to make the “correct” choices — ones which lower depression levels in the status bar Depression Quest treats the experience of depression as “something to be moved through as quickly as possible” and successfully defines the experience as something without value to the person experiencing it.”

And later adding:

“While one of the goals of Depression Quest is to“fight against the social stigma and misunderstandings that depression sufferers face,” it is possible that the framework utilized may inadvertently contribute to these very problems. By taking the biomedical stance and creating a system in which “correct” choices are implied, Depression Quest may have the effect of teaching its reader-players to take an oversimplified view of depression and other forms of mental dis-ease.”

So we need to be careful and conscious of the possible effects of systematization – in many cases promoting systems literacy is a useful and important task, but there is always the risk of oversimplification or systematizing in a way that erases elements of experience that diverge from this systematized portrayal.

Clockwise from top-left: Darfur is Dying, Half the Sky, Spent, Third-World Farmer

Second, producing digital games remains a technically difficult process – game development requires a number of specialist skills, and for this reason, games about social issues risk slipping into colonialist stances in that they are often produced by non-profit organizations or well-intentioned developers about particular experiences and situations rather than by the people actually experiencing them. As Paolo Pedercini points out, games have been produced about homelessness, civil wars, and gender violence without the involvement of those directly affected. This is especially troubling insofar as it reflects the integration of the logic of gamification and the white savior industrial complex, as represented in games like Half the Sky and Third World Farmer.

This isn’t a new issue – it’s one that activists, especially women of color and sex worker collectives, have been articulating for some time, in the face of dominant narratives that position them as docile populations that need to be rescued by white Western saviors. And researchers, activists, and artists outside of games have been grappling with issues around representation, power and voice for a long time. Alternative models have been put forth which decentralize the role of the authoritative outsider producing accounts on behalf of marginalized people: these include participatory action research and the promotion of in-community leadership within activist organizations.

The question for me then is: can we imagine community-lead games projects? I agree with Pedercini in that I think there is room for strategic alliances here, but we need to ask the question of whether games are useful for the communities in question or are being produced because of an interest on the part of external designers.

And more broadly, we need to ask whether or not games truly empower players to understand the systems they purport to describe.

(if games are so great at teaching systems thinking, why are gamers often unable to understand or acknowledge systemic social issues)

— Matthew Scary Burns (@MrWasteland) September 11, 2013

Games as Artistic Practice

Games entering traditional spaces of artistic legitimacy, various headlines

Games can be used to convey powerful intellectual and emotional messages. And they can be an attractive medium for the cultural value that play and interactivity currently enjoy in many circles. However, and this is important: the decision to produce a game immediately reduces the potential audience for your work.

And worse than that, this reduction is not uniform – insofar as digital games are a primarily straight white male coded space, creating a game likely cuts out people of color, women, queer people, many people with disabilities, and lower-income people. There are a variety of dynamics at work here – including the framing of games as a medium, the violently exclusionary community surrounding digital games, and the economic costs associated with participating in much digital play. We absolutely need to consider this when making the decision to produce a digital game rather than utilize another medium.

However, there are ways to ameliorate these problems. For instance, one of the reasons that the hypertext software Twine has been the site of such a flourishing of artistic production is that Twine games are generally free to play, have minimal technical and experiential requirements, and are simple to distribute I’ve tried to take these considerations into account in my own work – it’s why most of my games are brief and require minimal prior experience with games.

forest ambassador banner image

I’ve also recently begun curating these kinds of games on my website forest ambassador, in the interest of bringing them to wider publics. However, I want to speak to some of the issues with this push, of which I’ve been and continue to be a proponent. The drive to promote games-making as individual artistic practice is immensely valuable, but there is the risk that it promotes game-making as a site of singular focus and attention. Going back to Darius Kazemi’s comments, there’s the risk that we come to see games not as a single methodology but as the field within which we work. This leads to the state of trying to express ourselves within a medium, even when our ideas might be better served by other forms – simply because we see ourselves as “games people” or because we are enamored of the attention that we receive through the journalistic apparatus that has been built up around digital games.

Similarly, with forest ambassador I try to consciously select games that I expect will be of interest to nontraditional audiences, rather than attempting to represent or rehabilitate the medium for its own sake. Avoiding the “novelty trap” is a major concern for me – if I choose the medium of games to express an idea, ideally I want that to be because I feel that the medium is a good fit. I see other designers and developers sometimes lament that they aren’t having any good ideas, and I always want to ask them: have you tried writing a poem? Drawing something? Cooking a meal?

Games writers and developers sometimes like to talk about how the possibility space for games is endless, but there’s no reason to believe that’s any more true than it is for any medium. And it’s possible that in our excitement over exploring games, that we forget the very real limitations of the medium as a socially embedded form, rather than as the ideal space we sometimes seem to discuss it as.

Games as Investigative Practice

Paolo Pedercini

Paolo Pedercini of Molleindustria has argued that we can design games to understand complex systems. By this he is primarily referring to designing games that encourage players to build deeper understandings of systems through play – and I talked about this earlier. However, in designing such a game, we are forced to develop our own understanding of the system in question, too.

Image from Kessler & McKenna’s Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach

For instance, when I made LIM, I was trying to describe a system – a spatially bounded, interactional system, but a system nonetheless. In developing the game I drew on my own experience but also on research on gender attribution – the social-psychological process by which people mentally attribute gender to other persons, based on a range of criteria. I went back to a classic work on the subject, Kessler and McKenna’s Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach.

Kessler and McKenna argue that gender attribution is a nearly-instantaneous process, and one that is almost impervious to revision after the fact – once an assessment is made, it adapts to potentially “conflicting” information. I reflected on this as I worked on the game and realized that the model I was building didn’t fit my experience or that of others I knew – in fact, these attributions felt extraordinarily tenuous and always subject to revision. I built this tenuousness into the game, so that the player is never really guaranteed and was also pushed to think further about the ways that Kessler and McKenna’s model might need to be modified to account for the cultural changes in the years since they’d written the text, primarily around the increased visibility and awareness of transgender people.

So making a game to model a system can be one way of learning something about that system – and the things we learn from doing so may be different from the things we’d learn in more traditional investigative modes. I’m currently on hiatus from institutional scholarly work, but I certainly consider LIM a companion piece to my master’s thesis at the University of Washington, which investigated the spaces of gender-neutral public bathrooms.

Clockwise from top-left: Consequences, Infinite Loop, Bad Apple, Equality Street

I’m especially excited about games as investigative practice when thinking about communal and collective work, rather than focusing on individual production. Recently my friend Amanda Phillips ran a class called “Gaming the System” at UCSB where she had students design games with particular social justice issues in mind. This was an English class full of English majors – not CS, art, or design students. Fewer than half of the students in the class were self-described “gamers”, but by the end of the quarter, they produced eight prototypes about topics like domestic abuse, colorblindness ideology, and dating as a queer man of color. Phillips says that the class “was both a leap of faith and a radical stretching of comfort zones for most of the students who walked in on the first day expecting, as they inevitably do, another round of articles to read and papers to write.”

Thinking outside of the institutional space of the university, there are writing workshops – there’s one in Seattle called BENT that focuses on gender and sexuality – that are designed to help participants develop their ability to tell important personal stories, which necessitates reflecting on one’s experience and coming to new insights about it. It would be interesting, if challenging, to try and do the same with games, which gets back to the idea that games are – or at least have the potential to be – good at characterizing violent and oppressive systems. One of my long-term goals is to establish a workshop space to work with youth in which we’d read written work on social systems and try to make games with the goal of telling stories about living with structural violences. I especially like the idea of working with youth for this, and trying to show that games can be used for a wide variety of purposes beyond “fun”, and that the tools do exist to make them.

*

After all of this, I hope it’s clear that I’m still excited about the range of possibilities to which digital games are increasingly being put. But it’s important to me to use my liminal positioning with regards to games in order to point some of the issues I see with these uses. It’s far too easy to be swept up in exaltations of play and games, to see in them untold possibilities for expression, problem-solving, and learning. But we need to attend to games as they are and not just as we imagine or desire them to be – to their material reality and to the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they exist.

Further Reading

anthropy, anna. 2013. “How To Make Games About Being a Dominatrix”

anthropy, anna. 2012. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters

Bogost, Ian. 2013. “Doing Things Is Okay: On Darius Kazemi’s ‘Fuck Videogames’”

Bogost, Ian. 2011. How to Do Things With Videogames

Burns, Matthew. 2012. “The Illuminated World of Dylan Cassard.”

“Escape from the White-Savior Industrial Complex”

Gunraj, Andrea, Susana Ruiz, and Ashley York. 2011. “Power to the People: Anti-Oppressive Game Design.” Pp. 253-274 in Designing Games for Ethics: Models, Techniques, and Frameworks.

Kazemi, Darius. 2013. “Fuck Videogames”

Ryerson, Liz. 2013. “An In-Depth Response to Darius Kazemi’s ‘Fuck Videogames’”

Pedercini, Paolo. 2013. “Designing Games to Understand Complexity.”

Phillips, Amanda. 2013. “Gaming the System: Things I Learned by Asking Lit Majors to Design Their Own Digital Games.”

Pratt, Maddox. 2013. “The Game of Depression: Depression Quest and Writing Without Power”

Priestman, Chris. 2013. “Molleindustria: 10 Years of Radical Socio-Political Video Games.”

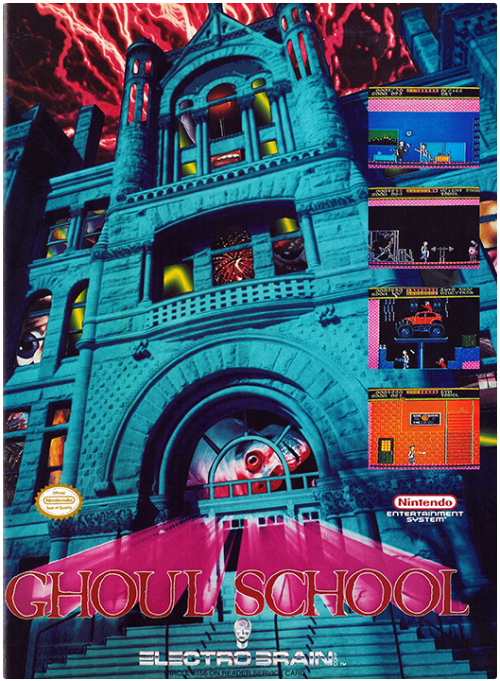

obscurevideogames: Ghoul School (Imagineering - NES -...

Ghoul School (Imagineering - NES - 1992)

I wish I had went to Ghoul School

Leningrad / Crash virus (1998).This is a not memory resident...

Leningrad / Crash virus (1998).

This is a not memory resident benign virus which searches for COM files and infects them by a standard manner. On Friday, 13th it types:

That could be a crash, crash, crash !

Squishy Witch Tummy - by VA Abraxa And here’s another one...

Squishy Witch Tummy - by VA Abraxa

And here’s another one I had time to finish inking. I guess you could say it’s Halloween themed n’ all… that and just another expression of my love for delightful smooshy chubby human fleshiness.

Extra fancy crystal girl portrait commission!

Extra fancy crystal girl portrait commission!

rusalka-mask: Finally figured out how Patreon works, and...

anna anthropylilith is amazing give her money to make games

Finally figured out how Patreon works, and figured I’d try it out now! I really hope this works, because I’d like to make stuff FOR ALL ETERNITY, be able to live a bit better, and worry about money a bit less!

http://www.patreon.com/rusalka

From the page:

I make video games primarily- I live alone in government housing on disability checks, and it’s one of the few things I can do to keep myself active and from sinking into total depression. To that end, I’d like to some day be able to live on my own resources, and as a trans person, it’d make transitioning a lot more feasible. I really don’t want to ever have to charge for my games- it makes me happy to see so many people who enjoy them, and I like to share these ideas for everyone- so I figure this is a good alternative for now.

REWARDS:

Fuck Festivals

fuck festivals.

i say this after having a wonderful time at IndieCade last week, and having just submitted my game Problem Attic to the IGF a few days ago.

the expectation placed on any so-called "indie game" to distinguish itself from the pack is much, much higher now. this might seem like a good thing, right? there are a lot more games now, so the stakes should be higher - and the games should be better, right? it, of course, depends on how you define "better". but this expectation has little to do with artistic or creative ambition and a lot to do with how professional-looking the game is. the end goal the forwarding of these games serves is to make "smaller games" become a new, viable, sustainable part of the games industry. everyone knows that Minecraft/Humble Bundle make tons of money, so a lot of people are pouring a lot of resources into getting in on that money.

this is a pretty violent shift from even five or six years ago, when a game like Passage was praised for being a unique achievement in game storytelling - where it was seen as a wildly left-field part of a new artistic vanguard. now it's becoming more apparent that a game like Passage was extremely lucky to benefit from there not being much else around to diminish it. now we can also see more clearly how conservative of the narrative of that game is in many ways - about a man and a woman and compromises they make, and how cliched the ideas behind it have become. now we can see how many games tried to be as artistically ambitious and less essentialist (i'm thinking of something like increpare's "Home") but never got nearly as much attention. now it would just look like a little experiment, one of many out there. it might get some coverage on a few indie gaming sites or get posted on freeindiegam.es and then that would be it. the conversation wouldn't sustain itself because there'd be something new to replace it in a week or less.

yes, it's easier to make a game than ever. the tools are much more accessible than they ever were before. and no, i'm not a person who believes that everyone making games (or art in general) is in any way bad at all. it's a wonderful thing, especially for the legions of the population who would otherwise be intimidated away from even attempting to try to make a game.

yet it's also hard to know in what spaces those games will be appropriately recognized and respected. things like the IGF and IndieCade might seem to be those spaces, but actually serve well those who have the ability to engage in a sustained PR to promote their games. this obviously benefits people with more resources and connections, who are almost universally not the type of people who would normally be scared away from making games. this is no secret. these festivals exist as a way to inject lifeblood into the games industry, or to legitimize games in the eyes of other industries like the film industry, not to subvert them.

festivals are supposed to be a bastion for new, ambitious developers to bring their game to a wider audience. but are festivals really developer friendly at all? for most developers, it's 95 dollars for the small hope that your game will reach a larger audience. except that it's more or less impossible for your game to be nominated unless you've waged an extended PR campaign for your game or are already a well-known developer. even for those who get in, they're expected to fly out to a conference and stay there (a flight which may or may not be paid for, other accommodations and food/drinks which almost certainly won't) and stand in front of a screen in a crowded expo floor for hours on end as people while people stumble their way through their game. this might be an acceptable sacrifice if there was just one festival - but there are many (the IGF being still the biggest) and there are a great number of games being exhibited at each of these festivals. each game is like a little tidbit, a little unit of ideas or concepts to be gorged on and eventually become absorbed into the industry. and so festival settings are fundamentally not served at all for slower or longer games - and particularly for text-based games. we don't value what these games may or may not have to offer. the nuances get glossed over because of the setting. we gorge on each one rapidly and leave. this is how we've been taught to treat videogames.

and personally, as someone who's designed a couple deliberately abstract games, there's nothing that sounds more like agony to me than being expected to explain and justify my game to any random person who walks by and plays it for five minutes. the Steam deal promised to developers nominated for last year's IGF was certainly a good thing, but that's only one festival of many - and a lot of the developers lucky enough to have the kind of PR clout to get in with the judges are also probably lucky enough to get on Steam without needing a nomination.

i admit it. some of these are my own realizations after designing a game (the aforementioned Problem Attic) that was in many ways unique and artistically ambitious, but i also recognized would not in any way be "festival-friendly". in itself, it might seem like a ridiculous idea that an artistically ambitious game wouldn't be "festival-friendly" - but in fact it makes perfect sense. festival jurors tend to self-consciously cherry-pick and reward the things with the most buzz. why? in order to make games more of a cultural event, for one - and to reward games which have managed to achieve some level of cultural penetration. there's also the practical matter of judges are going to naturally gravitate towards games or developers that they've already heard of, especially among the waves of games they haven't. and also to be what a good friend of mine calls a "photogenic indie" - something that's unique in maybe one or two ways but manages to overall have highly agreeable, unambiguous presentation. that's what people want to play, after all, right? they want the gloss, not the ugly, gross shit that shows its videogamey seams. that's what prominent members of the indie community or events like the IGF or IndieCade want to forward as examples of videogame expression.

i will say that IndieCade was in several ways a lovely, forward-thinking event. it made an effort to have events like Night Games that the public could attend (though the lines were way too long for them), and also stayed lax about checking badges, allowing people to go to talks they might not be able to get into if they really wanted to. but as far as the festival goes, i've also received some of the most condescending feedback i've ever had. here are the two worst offenders (click to make it larger):

one judge says i'm "asking too much of my audience", the other seems to interpret my very intentional aesthetic choices as the fact that i must be clearly an inept and/or confused beginner (that i'm female likely plays into this), or else i clearly wouldn't have made a game like this.

i want to be clear that i don't want to make it out like i'm an exception, or that this is just about me. in many ways i'm maybe pretty lucky. i have enough friends to where if i kept waging a public PR campaign i might actually be able to get recognized in spite of how strange the things i make are, or how unpopular some of the sentiments i express in writing are. but that's not the point. the point is to aspire to have some kind of fair chance for people who can't, or won't engage in this. the point is to emphasize the people who are really, truly doing the most ambitious and crazy and unique things with videogames, and not the ones who are friends with the most judges, or who are making the most "photogenic" games. and i don't think it's possible for this to happen in any real way in the climate of these festivals.

CloudPaint

CloudPaint is a fully operational online version of the original MacPaint released with the Macintosh in 1984. The source code for version 1.3 of MacPaint is available from the Computer History Museum.

Tags: Apple design MacintoshThe Mutant Virus

anna anthropythe mutant virus is a nintendo game where you try to kill conway's game of life.

The Mutant Virus

(from Grail Quest #8: Legion of the Dead, 1987)

(from Grail Quest #8: Legion of the Dead, 1987)