Shared posts

Neurotypical Psychotherapists & Autistic Clients

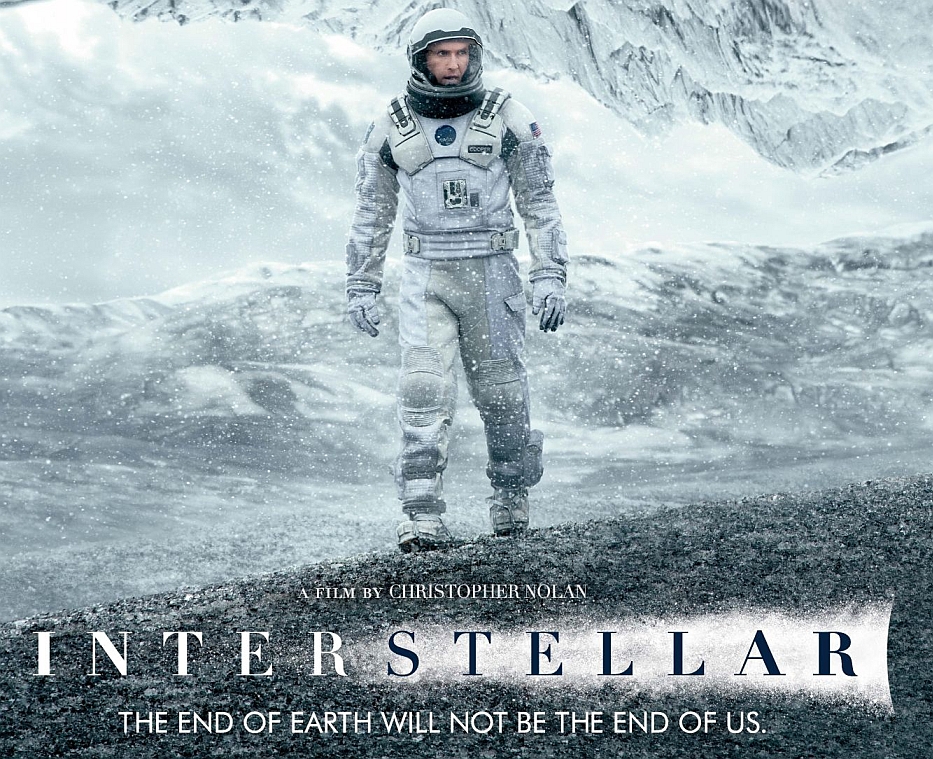

Interstellar as Self-Defeating Allegory

Contains spoilers for both Sunshine and Interstellar.

Recent decades have seen a rise in popularity for non-religious allegory films. But the latest, the Nolan brothers’ Interstellar, provides its own strong reasons for rejecting its message.

The religious allegory has long depended upon travelling as its strongest metaphor for life, as evidenced in both John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and Wu Cheng’en’s Journey into the West (also known as Monkey) – the classic Christian and Buddhist travelogue allegories respectively. Two of the recent spate of non-religious allegories also build their plots upon an epic journey, namely Danny Boyle’s Sunshine and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. Here, the mythic themes of traditional religion are replaced with contemporary non-religion, specifically positivism (which collects various mythos that have in common a strong trust in the sciences as our most reliable truth-givers). Other positivistic allegories in cinemas recently include Greg Motolla’s Paul (penned by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost) and Ricky Gervais and Matthew Robinson’s The Invention of Lying, both of which descend into bigotry, the latter to a jaw-dropping extent. Of course, religious allegory is hardly immune to this: Journey to the West is about as racist towards Taoists as Paul is towards rural Christianity, for instance.

Interstellar and Sunshine are two peas in a pod: movies about scientists embarking upon an epic space journey to save the Earth from a poorly explained global catastrophe that – quite implausibly, in the case of Interstellar - can only be solved by physicists. Both movies have similar influences; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey has been mentioned by both directors, and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris also deserves a nod in this regard. And both movies hired astrophysicists as full-time consultants – Einstein Medal winner Kip Thorne for Interstellar, and perpetual rictus-grinned Brian Cox for Sunshine. On the surface, this seems like a sensible consultation gig, although in the case of Interstellar the scientific themes go beyond mere physics and a broader consultation might have been sensible. The role of these physicist-advisors is as much spiritual as it is practical, though, as can be seen in Brian Cox’s conversion of Sunshine-star Cillian Murphy to atheism (i.e. a specifically atheological form of positivism) during filming. I suspect in this case that Murphy’s prior agnosticism was already positivistic in inclination, so the ‘change’ was more of denomination than of inclination.

Whereas Sunshine feels very much like Pilgrim’s Progress for those who put their faith in Science, at least before devolving into serial-killer-in-space, Interstellar seems a little more internally conflicted, but only just. Matt Damon’s hilarious cameo as evolutionary dogmatist Dr. Mann provides (sometimes unintentionally) some much needed humour in the frankly overlong movie. Mann has swallowed all of the Dawkins-esque dodgy metaphors about evolution without, it seems, accepting Dawkins’ own exultation to rise above this fallen state (a mythos Dawkins himself exports from Christianity, as others have noted). Similarly, John Lithgow has a few injections of grandfatherly wisdom that help leaven the oh-so-slowly rising bread: I giggled at his remark about Matthew McConaughey’s character ‘praying’ to his gravitational anomaly – far more apposite than perhaps even the Nolan brothers intended!

As spectacle cinema, Interstellar is a strangely effective mix of awe and boredom. But as didactic cinema, the Nolans shoot themselves through their collective feet. Christopher Nolan has stated that with this movie he wanted to rekindle interest in space travel after the disappointing termination of the space shuttle programme. But by its own internal logic, Interstellar is a massive argument against its own rhetoric. The problem springs from its energising mythos being that of the early twentieth century Russian school teacher Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who responded to early rocketry by stating: “The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but mankind cannot live in a cradle forever.” In the film, this is delivered as “Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here”, and Dylan Thomas’ striking poetry is repeatedly deployed to underscore this theme. This is a mythos I have dubbed “Flee the Planet” – and it is one of the most dangerous (in the Enlightenment sense) non-religious ideologies in circulation. As ground-breaking evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis remarked, it is a fantasy to think that space exploration is something possible solely through shiny metal technologies and not through messy biological partnerships. As a result, if we are to explore the stars, it is first necessary to fix our problems here on Earth.

This is the first way Interstellar’s message stumbles: it spends the entirety of the first hour painting its picture of a doomed Earth but never really manages to explain why that catastrophe is inescapable, or (equivalently) why super-physicists can save us by evicting us into space but super-biologists are powerless to save us on Earth. If it is possible, as the film’s ending posits, to create majestically perfect space colonies through the wonder of physics, why is it impossible to build (sealed) terrestrial colonies upon the Earth? Because frankly, being in space changes nothing here: if you can’t build sustainable self-contained colonies on the Earth, you’re not going to be able to build them in space either. The film may have got its physics ducks in a row, but its biology ducks are all higgledy-piggledy. We can still buy into conceit this because apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic scenarios are so familiar to us now, but in this case we ought to be more sceptical about its premise, given the director’s intention to motivate viewers towards a specific way of thinking.

More egregiously on this front, Interstellar veers into very strange metaphysical nonsense in its attempts to neatly tie everything up too neatly. Behind its immediate mythos of “Flee the Planet” lies a more general mythos that philosopher Mary Midgley has dubbed “Science as Salvation”. But the sciences are utterly powerless to provide salvation in Interstellar, because its entire premise is based upon aid from unknown beings that McConaughey’s character insists (with a total absence of evidence – bad positivist, no cookie for you!) are five-dimensional future descendants of humanity. These beings open the wormhole and construct the tesseract that are the necessary plot devices for saving all of humankind in the story. This actually doesn’t make a lick of sense if you examine it too closely, but setting this aside the whole “Science as salvation” mythos fails if what actually saves you is a deus ex machina, or rather homo ex machina since we are supposed to believe that future descendants of humanity are the godlike aliens in this story. Thus if the film attempts to rekindle interest in space travel by suggesting that we’ll need to escape the planet to live after we kill the Earth, it contradicts its own didactic intentions by making such an outcome impossible to conceive without a thoroughly un-positivistic faith in superpowered future post-humans manipulating events like the Greek Gods lowered by a crane into the theatre that gave us the god-in-the-machine metaphor in the first place. As allegory, Interstellar is shockingly self-defeating.

When religious and non-religious allegories posture against rival mythologies, it is almost always ‘the best of us’ versus ‘the worst of you’ – which is (not coincidentally) also how the “Science versus Religion” mythos operates ideologically. In Journey to the West, the silly Taoists are never allowed to present their perspective, and problems within Buddhism never come to the fore. Of course, this doesn’t hurt the story at all! In Interstellar, however, there is a surplus of what I’ve called cyberfetish (blindness when judging our technology) that, unlike the magical battles in Wu’s narrative, undermines what the Nolans want us to make-believe. McConaughey expresses cyberfetish succinctly when he is enraged by his kids’ school adopting textbooks that say the moon landings were faked for political purposes (nice touch, that). He objects that there used to be a machine called an MRI and if they still had it, his wife wouldn’t have died. Maybe so. But isn’t grand scale monocultural farming facilitated by mechanized agriculture the root of the blight that threatens humanity with extinction in the film? Cyberfetish encourages us to see technology solely as friend and saviour – magical medical interventions, test-tube repopulation miracles, sassy robot friends, and galaxy-spanning spaceships. It blinds us to the ways that unfettered technological development has hastened the threat of our own extinction, and already brought about the permanent eradication of many of the species we shared the planet with until very recently indeed.

Interstellar is an epic thought experiment that seeks to persuade us into taking a rash course of action by eliding almost all the relevant information and making it seem that its way is the one true path. There is a nasty history of this in twentieth century moral philosophy, not to mention Medieval religious doctrine: we should not find it more palatable just because it indulges our valiant yearning to touch the stars. If humanity is to explore space, it will not be through the “Flee the Planet” mythos: as Interstellar inadvertently makes clear, this is a dangerous fantasy. Rather, our relationship must first and foremost be with our living planet in all its necessary diversity. “The Earth and then space” is the only mythology that might give us even a fleeting chance of one day travelling beyond our world, and even then we may have to accept (as Interstellar publically denies) that it is our robots that will have to be our proxies amongst the stars. Science fiction inspires us all – both religious and non-religious people alike. Let us ensure it inspires us to do our duty to our fellow Earthly beings rather than encouraging us to hasten our self-inflicted apocalypse by trying to sacrifice the planet in order to ineffectually flee into the heavens.

Interstellar is in cinemas now. For more on science fiction as positivistic mythos, see The Mythology of Evolution, and for more on cyberfetish and the moral dangers of thought experiments see Chaos Ethics.

Please note that this is not a review, but rather a philosophical critique. If you want my review of Interstellar it would be "see this movie if you enjoy attempts at serious science fiction with striking cinematography."

Interstellar and my Inner Anti-Abortionist.

Let’s start this review by warning you all that major spoilers follow. Then let’s talk about abortion.

If I squint really hard, I can sort of see how someone possessed of a belief in an immortal soul— and further, that it slides down the chute the moment some lucky sperm achieves penetration— might hold an antiabortion stance on the grounds that they’re protecting Sacred Human Life. What I can’t see is how that stance would be in any way compatible with actively denying the means to prevent such life from being jeopardized in the first place. And yet— assuming the stats haven’t changed since I last looked in on them— the majority of those who unironically refer to themselves as “pro-Life” not only oppose abortion, but birth control and sex education as well.

You can’t reasonably describe such a suite of beliefs as “pro Life”. You can’t even reasonably describe them as “anti-abortion”. What they are is anti-sex. These people just don’t want us fucking except under their rules, and if we insist on making our own we should damn well pay the price. We deserve that STD. We should be forced to carry that pregnancy to term, to give up the following two decades of our lives— not because new life is a sacred and joyous thing, but because it is onerous and painful, a penalty for breaking the rules. We should suffer. We should live to regret our wanton animalistic shortsightedness. It is galling to think that we might just skip gaily off into the sunset, postcoitally content, unburdened by the merest shred of guilt. There should be consequences.

Movies like Interstellar serve as an uncomfortable reminder that maybe I have more in common with those assholes than I’d like to admit.

*

In a market owned by genre, where every second movie is crammed to the gills with spaceships and aliens (or, at the very least, plucky young protagonists dishing out Truth to Power), Interstellar aspires to inspire. It explicitly sets out to follow in the footsteps of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It wants to make you think, and wonder.

It succeeds, too. It makes me wonder how it could fall so far short of a movie made half a century ago.

This is not to say that Interstellar is a bad movie. It actually has significantly more on the ball than your average 21rst-century genre flick (although granted, that’s a much lower bar to clear than the one Kubrick presented). The dust-bowl vistas of a dying Earth evoke the sort of grim desolation we used to get from John Brunner’s environmental dytopias, and— most of the time, anyway— Interstellar shows a respect for science comparable to that evident in Gravity and 2001.

Admittedly, my delight at seeing space presented as silent has more to do with the way decades of Hollywood crap have hammered down my own expectations than it does with any groundbreaking peaks of verisimilitude; it’s not as though every school kid doesn’t know there’s no sound in a vacuum. On the other hand, the equations Interstellar‘s FX team used to render the lensing effects around Gargantua, the movie’s black hole— equations derived by theoretical physicist-and-science-consultant Kip Thorne— have provided the basis for at least one astrophysics paper here in the real world, an accomplishment that would make Arthur C. Clarke jealous. The hole was carefully parameterized to let our protags do what the plot required without being spaghettified or cooked by radiation. The physics of space travel and Gargantua’s relativistic extremes are, I’m willing to believe, plausibly worked out. So much of the science seems so much better than we have any right to expect from a big-budget blockbuster aimed at the popcorn set.

Why, then, does the same movie that gets the physics of event horizons right also ask us to believe that icebergs float unsupported in the clouds of alien worlds? How can the same movie that shows such a nuanced grasp of the gravity around black holes serve up such a face-palming portrayal of gravity around planets? And even if we accept the premise of ocean swells the size of the Himalayas (Thorne himself serves up some numbers that I’m sure as shit not going to dispute), wouldn’t such colossal formations be blindingly obvious from orbit? Wouldn’t our heroes have seen them by just looking out the window on the way down? How dumb do you have to be to let yourself get snuck up on by a mountain range?

Almost as dumb, perhaps, as you’d be to believe that “love” is some kind of mysterious cosmic force transcending time and space, even though you hold a doctorate in biology.

You’re probably already aware of the wails and sighs that arose from that particular gaffe. Personally, I didn’t find it as egregious as I expected—at least Amelia Brand’s inane proclamation was immediately rebutted by Cooper’s itemization of the mundane social-bonding functions for which “love” is a convenient shorthand. It was far from a perfect exchange, but at least the woo did not go unchallenged. What most bothered me about that line— beyond the fact that anyone with any scientific background could deliver it with a straight face— was the fact that it had to be delivered by Anne Hathaway. If we’re going to get all mystic about the Transcendent Power of Lurve, could we a least invert the cliché a bit by using a male as the delivery platform?

The world that contains Interstellar is far more competent than the story it holds. It was built by astrophysicists and engineers, and it is a thing of wonder. The good ship Endurance, for example, oozes verisimilitude right down to the spin rate. Oddly, though, the same movie also shows us a civilization over a century into the future— a whole species luxuriating in the spacious comfort of a myriad O’Neil cylinders orbiting Saturn— in which the medical technology stuck up Murphy Cooper’s nose hasn’t changed its appearance since 2012. (Compare that to 2001, which anticipated flatscreen tech so effectively that it got cited in Apple’s lawsuit against Samsung half a century later.) (Compare it also to Peter Hyam’s inferior sequel 2010, in which Discovery‘s flatscreens somehow devolved back into cathode-ray-tubes during its decade parked over Io.)

Why such simultaneous success and failure of technical extrapolation in the same movie? I can only assume that the Nolans sought out expert help to design their spaceships, but figured their own vision would suffice for the medtech. Unfortunately, their vision isn’t all it could be.

This is the heart of the problem. Interstellar soars when outsourced; only when the Nolans do something on their own does it suck. The result is a movie in which the natural science of the cosmos is rendered with glorious mind-boggling precision, while the people blundering about within it are morons. NASA happens to be set up just down the road from the only qualified test pilot on the continent— a guy who’s friends with the Mission Director, for Chrissakes— yet nobody thinks to just knock on his door and ask for a hand. No, they just sit there through years of R&D until cryptic Talfamadorians herd Cooper into their clutches by scribbling messages in the dirt. Once the mission finally achieves liftoff, Endurance‘s crew can’t seem to take a dump without explaining to each other what they’re doing and why. (Seriously, dude? You’re a bleeding-edge astronaut on a last-ditch Humanity-saving mission through a wormhole, and you didn’t even know what a wormhole looked like until someone explained it to you while you were both staring at the damn thing through your windshield?)

You could argue that the Nolans don’t regard their characters as morons so much as they regard us that way; some of this might be no more than clunky infodumping delivered for our benefit. If so, they apparently think we’re just as dumb about emotional resonance and literary allusion as we are about the technical specs on black holes. Michael Caine has to hammer home the same damn rage against the dying of the light stanza on three separate occasions, just in case it might slip under our radar.

And yet, Interstellar came so close in some ways. The sheer milk-out-the-nose absurdity of a project to lift billions of people off-planet turns out to be, after all, just a grand lie to motivate short-sighted human brain stems— until Murphy Cooper figures out how to do it for real after all. Amelia Brand’s heartbroken, irrational description of love as some kind of transcendent Cosmic Force, invoked in a desperate bid to reunite with her lost lover and instantly shot down by Cooper’s cooler intellect— until Cooper encounters the truth of those idiot beliefs in the heart of a black hole. Time and again, Interstellar edges toward the Cold Equations, only to chicken out when the chips are down.

*

But the thing that most bugs me about this movie— the thing that comes closest to offending me, although I can’t summon anywhere near that much intensity— was something I knew going in, because it’s right there in the tag line on every advance promo, every Coming-Soon poster:

The end of the Earth will not be the end of us.

Or

Mankind was born on earth. It was never meant to die here.

Or

We were not meant to save the Earth. We were meant to leave it.

Which all comes down to

Let’s trash the place, then skip out and stick everyone else with the bill.

This is where I finally connect with my inner antiabortionist. Because I, too, think you should pay for your sins. I think that if you break it, you damn well own it; and if your own short-sighted stupidity has killed off your life-support system, it’s only right and proper that that you suffer, that you sink into the quagmire along with the other nine million species your appetites have condemned to extinction. There should be consequences.

And yet, even in the face of Interstellar‘s objectionable political stance— baldly stated, unquestioned, and unapologetic— I can only bristle, not find fault. Because this is perhaps the one time the Nolan sibs got their characters right. Shitting all over the living room rug and leaving our roommates to deal with the mess? That’s exactly what we’d do, if we could get away with it.

Besides. When all is said and done, this was still a hell of a lot better than Prometheus.

Why are ghosts scary? Shouldn’t seeing a ghost be literally the best news you can ever...

Why are ghosts scary? Shouldn’t seeing a ghost be literally the best news you can ever receive?

"Oh my god, proof that the soul does survive death and that my consciousness will not be totally extinguished when I die! Aaaah, run!”

Left Behind Classic Fridays, No. 10: ‘The Hypothetical Bus’

Don’t put off re-reading this 2003 post on how Left Behind substitutes old-fashioned hellfire & brimstone evangelism for a tribal triumphalism that’s even worse.

Sure, you could set it aside to read later … but then you might just walk out that door and get hit by a bus. And then what good would your plans to read it later do you?

That bus is always there, just outside that door — just outside every door. And today just might be the day.

I don’t remember much of Donald W. Thompson’s series of Rapture movies from when I saw them back in middle school at Hydewood Park Baptist Church.

I do remember that they were pretty scary. Thompson was a low-budget hack, but he had an eye for haunting detail — the drone of an unattended lawn mower in a suburban yard (Thompson raptured people fully clothed) was far creepier and more affecting than anything in Left Behind.

Thompson’s films – A Thief in the Night and A Distant Thunder are the two I remember — were explicitly evangelistic. He was trying to scare people into conversion with a hypertrophied version of the famous Hypothetical Bus.

Even people who didn’t grow up in evangelical youth groups are acquainted with the Hypothetical Bus — the great memento mori of our time. “You could walk out that door and get hit by a bus.”

The H.B. is regularly (if a bit oddly) invoked to comfort those facing a potentially terminal illness. It also remains a standard metaphor for evangelists, urging their listeners to “get right with God.”

As an enthusiastic supporter of public transportation, I often wish for a different symbol of our mortality. I haven’t checked with my brother the actuary, but I’m pretty sure buses themselves are not particularly menacing.

As an enthusiastic supporter of public transportation, I often wish for a different symbol of our mortality. I haven’t checked with my brother the actuary, but I’m pretty sure buses themselves are not particularly menacing.

Yet while the H.B. is often misused for callow comfort or exploitative fear-mongering, it’s not bad theology. Death can come for any of us in “the twinkling of an eye,” and no one knows the day or the hour in which the end may come.

Thompson’s films used the threat of the Rapture as a surrogate for the threat of death. Like the evangelist warning of imminent, diesel-powered doom, he was trying to scare his audience into heaven. In its own way, A Thief in the Night is an old-fashioned fire-and-brimstone sermon — Thompson’s version of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

I expected Left Behind to take a similar course, to invoke the apocalypse as a cosmic version of the Hypothetical Bus, urging sinners to repent because the end is near.

But that’s not LaHaye and Jenkins’ agenda. Jonathan Edwards famously wrote of the fires of Hell as a warning. L&J write of the Tribulation as a vindication, a confirmation of their own rightness and righteousness.

Their intended audience is people who, like them, already believe in premillennial dispensationalism. Their tone is the juvenile triumphalism of an adolescent semi-threatening suicide or running away: Just wait until I’m gone. Then you’ll see. Then you’ll be sorry.

There’s a message here for “the unsaved,” but it’s not the message of salvation that Edwards and Thompson extended, however clumsily. It is not “get right with God, because time is short,” but rather this: “Ha-ha! We were right and you were wrong! Have fun in Hell!”

I would suggest that this is not a very winsome or effective strategy for evangelism.

Chris Rock Talks White People, Racism, What "Racial Progress" Really Means, and Isolation

Frank Rich: What would you do in Ferguson that a standard reporter wouldn’t?

Chris Rock: I’d do a special on race, but I’d have no black people.

Frank Rich: Well, that would be much more revealing.

Chris Rock: Yes, that would be an event. Here’s the thing. When we talk about race relations in America or racial progress, it’s all nonsense. There are no race relations. White people were crazy. Now they’re not as crazy. To say that black people have made progress would be to say they deserve what happened to them before.

Frank Rich: Right. It’s ridiculous.

Chris Rock: So, to say Obama is progress is saying that he’s the first black person that is qualified to be president. That’s not black progress. That’s white progress. There’s been black people qualified to be president for hundreds of years. If you saw Tina Turner and Ike having a lovely breakfast over there, would you say their relationship’s improved? Some people would. But a smart person would go, “Oh, he stopped punching her in the face.” It’s not up to her. Ike and Tina Turner’s relationship has nothing to do with Tina Turner. Nothing. It just doesn’t. The question is, you know, my kids are smart, educated, beautiful, polite children. There have been smart, educated, beautiful, polite black children for hundreds of years. The advantage that my children have is that my children are encountering the nicest white people that America has ever produced. Let’s hope America keeps producing nicer white people.

Frank Rich: It’s about white people adjusting to a new reality?

Chris Rock:Owning their actions. Not even their actions. The actions of your dad. Yeah, it’s unfair that you can get judged by something you didn’t do, but it’s also unfair that you can inherit money that you didn’t work for.

Frank Rich: Would you seek out someone to interview who might not normally be sought out?

Chris Rock: I would get you to interview somebody, and I would put something in your ear, and I’d ask the questions through you.

Frank Rich: You’d have a white guy.

Chris Rock: And I would ask them questions that you would never come up with, and we’d have the most amazing interviews ever.

Frank Rich: And we’d be asking white people and black people?

Chris Rock: Just white people. We know how black people feel about Ferguson — outraged, upset, cheated by the system, all these things.

Frank Rich: So you think people can be lulled into saying the outrageous shit they really feel?

Chris Rock: Michael Moore has no problem getting it. Because he looks like them. But the problem is the press accepts racism. It has never dug into it.

Frank Rich: When Obama was running for president, a certain kind of white person would routinely tell reporters, “He’s just not one of us.” Few reporters want to push that person to the wall and say, “What do you mean he’s not like you, unless you’re talking about the fact that he’s African-American?” Where else besides Ferguson would you hypothetically want to interview white people?

Chris Rock: I’d love to do some liberal places, because you can be in the most liberal places and there’s no black people.

Frank Rich: I assume one such place is Hollywood.

Chris Rock: I don’t think I’ve had any meetings with black film execs. Maybe one. It is what it is. As I told Bill Murray, Lost in Translation is a black movie: That’s what it feels like to be black and rich. Not in the sense that people are being mean to you. Bill Murray’s in Tokyo, and it’s just weird. He seems kind of isolated. He’s always around Japanese people. Look at me right now.

Frank Rich: We’re sitting on the 35th floor of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel overlooking Central Park.

Chris Rock: And there’s only really one black person here who’s not working. Bill Murray in Lost in Translation is what Bryant Gumbel experiences every day. Or Al Roker. Rich black guys. It’s a little off.

But the thing is, we treat racism in this country like it’s a style that America went through. Like flared legs and lava lamps. Oh, that crazy thing we did. We were hanging black people. We treat it like a fad instead of a disease that eradicates millions of people. You’ve got to get it at a lab, and study it, and see its origins, and see what it’s immune to and what breaks it down.

Politics that feel good.

Sometimes I miss being a conservative. (The libertarian kind, not the Republican “we are very concerned about people having the wrong kind of sex” kind. But I’m not talking about some palatably reconstructed anarcho-techno-eco-libertarianism, I’m talking about the kind with guns.)

Not that I think it was more right or ethical or useful or really anything. It just felt better.

There’s great comfort and even pride in holding a political philosophy that says you earned what you have by being individually strong and smart, and that you should keep what you earned because no one is better qualified than you to decide how to use it. Believing that you are the master of your own fate and that the greatest good is for you to do whatever you want—that’s a nice feeling.

Maybe more than anything, conservatism puts the feeling of being Good Enough in reach. You don’t have to be constantly trying to save the world. You just have to carve out and clean up your little patch of the world (ideally some sort of cabin or ranch) and provide for yourself and your family without bothering the neighbors, and you’re Good Enough.

Again, I’m not saying any of this is right or politically defensible. I’m just saying that when you’ve grown up with messages that you’re incompetent to make your own decisions, that you don’t deserve any of the things you have, and that you’ll never be good enough, the fantasy of rugged individualism starts looking pretty damn good.

—

Intellectually, I think my current political milieu of feminism/progressivism/social justice is more correct, far better for the world in general, and more helpful to me since I don’t actually live in a perfectly isolated cabin.

But god, it’s uncomfortable. It’s intentionally uncomfortable—it’s all about getting angry at injustice and questioning the rightness of your own actions and being sad so many people still live such painful lives. Instead of looking at your cabin and declaring “I shall name it… CLIFFORDSON MANOR,” you need to look at your cabin and recognize that a long series of brutal injustices are responsible for the fact that you have a white-collar job that lets you buy a big useless house in the woods while the original owners of the land have been murdered or forced off it.

And you’re never good enough. You can be good—certainly you get major points for charity and activism and fighting the good fight—but not good enough. No matter what you do, you’re still participating in plenty of corrupt systems that enforce oppression. Short of bringing about a total revolution of everything, your work will never be done, you’ll never be good enough.

Once again, to be clear, I don’t think this is wrong. I just think it’s a bummer.

—

I don’t know of a solution to this. (Bummer again.) I don’t think progressivism can ever compete with the cozy self-satisfaction of the cabin fantasy. I don’t think it should. Change is necessary in the world, people don’t change if they’re totally happy and comfortable, therefore discomfort is necessary.

But I think this is all just… something to be aware of. When you wonder why someone would ascribe to political beliefs that seem evil or uncaring, it’s frequently because those beliefs make them feel good. And not in some lazy greedy “muahahaha” sense. In the very human “I want to like myself and feel like I’m doing okay” sense.

The Cold War Never Ended, II

OK, so what I was saying last time was that

THE COLD WAR NEVER ENDED

Actually, from one point of view, saying that the Cold War never ended is not so far from common sense. Putin’s Russia has been pursuing the same kind of authoritarian and bellicose policies as his Soviet predessesors, and op-ed columnists are saying it’s the Cold War all over again. And maybe there’s something to that. But I’m not saying that the Cold War has returned, I’m saying it never ended.

We ordinarily understand the Cold War as a geopolitical conflict between adversaries motivated by that characteristically modern thing, ideology. Or perhaps it was not so modern at all; the conflict of social philosophies might find its echo in the religious wars of the Middle Ages. But no matter; we understand that this was a conflict over ideology between adversaries equipped with weapons that, if used, would destroy all human life forever. This, too, was a modern situation, and unarguably so: many times before had the religious imagination conceived the end of the world through the intervention of some god, but at no other point in human history had the end of the world been grasped in a scientific way.

Science is (among other things) a way to understand reality as reality. Perhaps its greatest single contribution has been the idea that there is an “objective truth” that brackets and transcends individual human experiences (which are “subjective”) and in which things exist and events happen whether or not people are there to experience them or believe in them or otherwise participate in their reality.*

And what was different about the end of the world that nuclear weapons promised was that it would take place in that realm, in objective reality. This meant mass death for real, the final death, no kali yuga and the turning of the great wheel back to the beginning, no Last Judgment and afterlife, but a kind of Satanic inversion of the Last Judgement, with the arrow of time going thunk into the end of human history but without the long sought-for goal of theophany, without any goal at all, in fact, without meaning and without redemption. The scientific worldview had given the individual this idea of death (which was hard enough), but now death-as-the-end, the true terrifying nothing of death, was encountered on the species level.

originally posted at http://gifovea.tumblr.com/post/62876532315

What nuclear mass death promised was very modern indeed: human death without human meaning. Death would come at random: someone somewhere in the vast military-industral apparatus would screw up, push the wrong button or something, and the missiles would fly. You would never find out what it was, of course, because you would be dead. So all you knew was that you could die at any time, with no warning, for no cause that you would ever discover, and that your death likewise would cause nothing to happen, because all causality, all the affairs of human beings, would have come to a complete and eternal stop.

And above all there was nothing you could do to stop this from happening. The Cold War created vast superstates, but it also created the possibility for its citizens to glimpse (however fleetingly and partially) their true vastness. The Cold War state was its own aesthetic, a Cold War sublime. The state had its own ends, and if they were not yours it didn’t matter, nothing you could do would budge the state one iota from its blind and irresistible movements. And if you tried to deflect the state from its course, to try your strength against this Leviathan and fight its purposes, nothing would happen except that, for a terrible moment, the state might return your gaze, and you would then see (just for an instant) the true size and strength of the animal you had just provoked.

The state, then, was the god of the new age, or rather the demiurge: a blind, cruel, destroying god that (through some meta-historical reversal or enantiodromia) had reincarnated the God of the Old Testament, “the great fuming dyspeptic God who raged round his punishment laboratory.”** But the Biblical God is bigger than any destruction He can propose; He will always outlast us. When the bombs drop, though, the state will die like everything else. The state is godlike in its power and reach but in the end is merely what Freud called the prosthetic god, the human being extended and amplified by his technologies, like Ripley in her mech suit.

Being destroyed by God is comforting, in a way: at least He noticed. At least He cared enough to kill me. But the terror of the Cold War was the possibility of death at the hands of the prosthetic god we had made of ourselves, the state, which had taken the place of God. Maybe we killed God, or sent Him packing, His services no longer required. Most likely, He never existed in the first place. But (and this is the worst thought of all) maybe He did exist, and maybe He once cared for us, but that’s over now, he’s given up on us, he’s walked out and has left us alone to kill ourselves. Deus absconditus.

*Then again, maybe you don’t think that anyone had to invent that way of thinking—it just seems unproblematically there, like clouds and feeling hungry at lunchtime. “But isn’t reality, uh, reality?” I hear you asking. Well, no, for most human beings throughout most of history this is a very strange way to view the world—actually, an unthinkable one.

**Anthony Burgess, Little Wilson and Big God, 59.

It’s a Marvel comic book, Saturday matinee fairy tale, boy

Zephyr DearThey brought it down to 670 in three years...

• The Maseno School in Kenya had problems finding energy and getting rid of waste. A group of students there realized that this was actually, to use a phrase from Wendell Berry, a solution neatly divided into two problems. And so now the Masero School turns its waste into energy. The kids are all right.

• Thanks to Peter for linking to this Russian Orthodox “Statement on Brother Nathanael,” the anti-Semitic and homophobic YouTube street preacher mentioned here recently. Short version: The guy is unwell and doesn’t represent any monastery or other Orthodox organization, and the church he claims to represent is appalled, saddened and frustrated by his manic “ministry” of hate.

• Flood geology and fossils (via James McGrath and Michael Roberts — anybody know the original artist and their site?):

• Think of this as a kind of point/counterpoint debate: Paul Bibeau proposes that we defund the Pentagon and pour all that money instead into Canadian indie rock. But Chris the Cynic offers a compelling case for, instead, building giant robots.

• The Flood Christian Church isn’t near where any of the rioting in Ferguson, Missouri, took place last week — but it was deliberately torched last Monday night and burned to the ground, “the glass storefronts on each side remain unscathed.” That’s the African American church Michael Brown’s family attends. Burning down black churches is an old and ongoing part of American society. Perhaps you remember President Clinton’s National Church Arson Task Force, an effort that was credited with reducing the number of such black-church burnings down to 670 over a three-year period in the late 1990s.

Ponder that for a moment: 670 in three years — a dozen incidents a week. Now imagine a single story of a single white church burned down because its congregation was white. We’d all know the name of that one church, and we’d never stop hearing about this momentous, monstrous tragedy.

Todd Starnes makes a living fabricating indignities suffered by white Christians and promoting a narrative of “persecution,” but when a black Christian pastor receives 71 death threats and sees his church burned to the ground, Starnes’ et. al. don’t seem to care. Interesting.

• As Erik Loomis notes, Wikipedia’s list of “White American riots in the United States” is far from comprehensive, but it does provide a decent starting point for exposing the lie that “rioting is only something that black people do.” I’d also note that “riot” is an inadequate word for things like the mob terror that killed as many as 300 people in Tulsa in 1921.

See also Katie Halper on “11 stupid reasons white people have rioted.”

OK, then, this seems appropriate here:

Celebrating the feast day of Mark Twain

Today is the birthday of Mark Twain, a day to be celebrated with jokes, stories and hallowed irreverence. Around here we like to mark the occasion by revisiting the greatest religious conversion narrative in American literature, a scene from Huckleberry Finn:

I about made up my mind to pray; and see if I couldn’t try to quit being the kind of a boy I was, and be better. So I kneeled down. But the words wouldn’t come. Why wouldn’t they? It warn’t no use to try and hide it from Him. Nor from me, neither. I knowed very well why they wouldn’t come. It was because my heart warn’t right; it was because I warn’t square; it was because I was playing double. I was letting on to give up sin, but away inside of me I was holding on to the biggest one of all. I was trying to make my mouth say I would do the right thing and the clean thing, and go and write to that nigger’s owner and tell where he was; but deep down in me I knowed it was a lie — and He knowed it. You can’t pray a lie — I found that out.

So I was full of trouble, full as I could be; and didn’t know what to do. At last I had an idea; and I says, I’ll go and write the letter — and then see if I can pray. Why, it was astonishing, the way I felt as light as a feather, right straight off, and my troubles all gone. So I got a piece of paper and a pencil, all glad and excited, and set down and wrote:

Miss Watson your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send. HUCK FINN

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now. But I didn’t do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking — thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me, all the time; in the day, and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a floating along, talking, and singing, and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I’d see him standing my watch on top of his’n, stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him agin in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and such-like times; and would always call me honey, and pet me, and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had smallpox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he’s got now; and then I happened to look around, and see that paper.

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“All right, then, I’ll go to hell” — and tore it up.

It was awful thoughts, and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming. I shoved the whole thing out of my head; and said I would take up wickedness again, which was in my line, being brung up to it, and the other warn’t. And for a starter, I would go to work and steal Jim out of slavery again; and if I could think up anything worse, I would do that, too; because as long as I was in, and in for good, I might as well go the whole hog.

Do you think Jurassic World looks dumb?

You’ve unleashed the kraken, my friend.

I am excited for JP4, as I am excited for any movie that has dinosaurs in it, and that theme music gets me every time because I remember how beautiful it was to see that first film. The first film showed us dinosaurs as they’d never been seen, dinosaurs based on thorough research (though not without their faults— those raptors and dilophosaurus for instance) and it changed the way dinos were portrayed in media forever.

And this is why I am so, so upset with JP4. It’s showing us the same old green-skinned scaly monsters and totally ignoring DECADES of new developments. It’s ignoring the reason why the first film worked so well— it was something new, based on actual scientific research. People love innovation, and many love learning really neat science facts, and JP4 is in no way going to do either of those.

Now I have heard the arguments FOR the scaly green-skinned boring designs:

1. "But Abby, there’s an in-universe explanation, they have frog DNA! They’re just trying to stay consistent." Never, never never say “but there’s a canonical reason” for something that’s problematic, whether it’s naked, boring dinosaurs or offensive stereotypes or racism/sexism. Someone at some point made a conscious decision to make it so, it’s not some unchangeable law that must be adhered to. It’s been at least 20 years in-universe since the first movie, are we really supposed to believe they didn’t keep making developments in their cloning process? Remember how frog DNA fricked everything up by making the dinos able to reproduce? What if they changed it to bird DNA once it became apparent that birds and dinos were so closely related, and to stop them from changing sex? And beyond all that the important thing to remember here is that it doesn’t MATTER if they aren’t exactly supposed to be dinosaurs in-universe, people who watch this movie are going to see them as dinosaurs. They are going to come away from this film thinking the “feathers theory” is still some weird fringe science and REAL dinosaurs are still green and scaly and naked. Also calling “consistency” when the dinosaurs’ appearances were changed between films is hardly a steady argument.

2. "There’s no way we could know what they look like so why even bother, we can make them look however we want!!1!" This is you choosing to ignore the vast wealth of knowledge we DO have. Paleontologists aren’t just making wild guesses, sitting around thinking “whooa duuude what if they had feathers, wouldn’t that just be wild” we KNOW. We have FOSSIL EVIDENCE. Technology has progressed to a point that we can look at the same fossil we had 30 years ago and find countless more details we didn’t know were there, didn’t think to look for. We even know what COLOR some feathers were, we know there were feather mites that preyed on those feathers. Trackways tell us how they walked, how many walked, where they walked. Fossilized nesting sites give us clues on how they cared for their young. We know so much, there is no reason to ignore the incredible amount of research people have done just because we haven’t seen living, breathing non-avian dinosaurs with our own eyes, especially considering the fact that so many people don’t know about all the stuff we know, because public outreach movies like JP4 keep blatantly ignoring it.

3. "But feathered dinosaurs look stupid, like big chickens. They could never sell that to an audience!" Okay look. People are going to see JP4. If you make it look good, and you have Chris Pratt, and you have Chris Pratt on a motorcycle riding with some velociraptors, people will see this movie. And is a chicken the only bird anyone knows? Have you never heard of the bearded vulture? Or eagles, and the fact that they attack BEARS? Even small birds are a formidable opponent to a person. And their feathers make them look magnificent, not stupid. In order to design crowd-pleasing dinosaurs, we don’t need to strip them of their feathers, we need designers who know what they’re doing. The blog paleoillustration reblogs excellent paleo art from capable artists, a game called Saurian is being developed that is using incredible artists such as grimchild to create the most accurate and beautiful dinosaurs possible, Emily Willoughby is excellent at using bird influences to make realistic feathered dinosaurs (including one of my favorite depictions of Microraptor!)— feathered dinosaurs do not look stupid. Even if they look stupid to you, that doesn’t stop them from existing, and perhaps you should immerse yourself in the world of feathered dinosaurs some more and get used to it, because they are here to stay. You aren’t getting Pluto back, and you aren’t getting your naked monsters back, either. When good scientists are presented with theories that disprove old theories, they don’t wallow in nostalgia, they accept it and move forward.

4. "Why do you even care so much, geez, it’s just a movie" Nothing is ever “just a movie”. Even if you think you aren’t, you are affected by what you see in movies. We tend to believe what we see in movies, even some of the ridiculous stuff. Movies can be an excellent way to present science to people in an easy to digest format, as we saw with JP1. Sure, the science was ridiculous, but it got people interested in actual dinosaurs. JP4 will be the only exposure most people have to dinosaurs— and it is decades behind. People will keep chuckling to themselves when I draw them a dinosaur with feathers, asking “haha so you buy into the feather theory?” as if it’s something a scientist posited in a fit of insanity, totally unsupported by evidence. When people keep seeing naked dinosaurs in pop culture, they assume that must be the accepted idea of what they looked like, or else it would be changed. So I have to make a stink, so I can get the word out that Paleontologists and even Junior Paleontologists absolutely do not support the current portrayal of dinosaurs in the media. This way, we can get more movies such as Dinosaur Island which I very much look forward to seeing, and Saurian which I very much look forward to playing.

And why does learning about accurate dinosaurs matter? Why should we want to learn about these weird bird/reptiles that died millions of years ago? Because learning about the world we live in is important. Just as we want to figure out how we fit into the universe, we want to figure out how we fit on our own planet, where we came from, our life history. This isn’t just a bunch of sheltered nerds sitting around saying “Well actually…” in a nasally voice, it’s an entire branch of science whose accomplishments are being ignored because a bunch of nostalgic 20-somethings are afraid of change and think “feathers look stupid, like a chicken”

All this being said, I am still going to see it the day it comes out, in the best seats in the house.

daughterofzami: "The Black Panthers have never viewed such...

"The Black Panthers have never viewed such paramilitary groups as the Ku Klux Klan or the Minutemen as particularly dangerous. The real danger comes from highly organized Establishment forces -the local police, the National Guard, and the United States military. They were the ones who devastated Watts and killed innocent people. In comparison to them the paramilitary groups are insignificant. In fact, these groups are hardly organized at all. It is the uniformed men who are dangerous and who come into our communities every day to commit violence against us, knowing that the laws will protect them.”

- Huey P. Newton, Sacramento and the “Panther Bill”

Ferguson

Conservatives are wringing their hands. “There is no indication that the [grand jury] system worked otherwise than as it should. Nonetheless, almost immediately protesters — soon become looters — were throwing rocks at the police and then setting ablaze police cars and local businesses.”

This ‘nonetheless’ seems to indicate confusion. To review.

1) The law heavily tilts in favor of cop defendants in a case like this (by design). The law sides with cops. The law trusts cops.

2) In Ferguson, the police are (by design) an outside force imposed on the community, not really a community force. Citizens don’t trust the cops, and rightly not.

What follows is that, in a case like the Brown/Wilson tragedy, if the justice system works ‘as it should’, citizens’ already weak faith in the system will tend to be shattered.

Yet conservatives are very concerned that Darren Wilson not be indicted just to preserve or restore order.

Jonah Goldberg: “We don’t have trials of innocent men simply for appearances’ sake. Having a trial just for show is too close to a show trial as far as I’m concerned.”

Who will think of the sanctity of every individual citizen’s life and rights?

But, by the time you’ve got 1 & 2, that ship has sailed. Conservatives who want 1) and are passively ok with 2) – at least in places like Ferguson – but who want order, need a mechanism for restoring and maintaining trust. If you were planning for something like this (if it hadn’t been this young black man, it would have been the next one) it’s hard to see how you don’t get to this fork in the decision tree: EITHER go all-in with the warrior-cops-as-occupiers model OR be prepared to indict some cop, guilty or not, if only as a semi-ritual show of respect across tribal lines. It is barbaric to build a system in which the citizens are one ‘tribe’, the ‘justice system’ of cops-and-courts another, semi-antagonistic ‘tribe’. But if that’s how you play it, don’t be surprised when a certain amount of tribal, eye-for-an-eye thinking results. If it seems like protestors are out for payback … well, what were you expecting?

Maybe we could institute some sort of strict liability weregild system, in communities like Ferguson. The police chief would just give a big bag of gold coins to the victim’s family, in the wake of any awful killing, no questions asked, and speak ritual words of atonement, to keep the tribes from having to go to war. In especially horrific cases, the cop responsible would have to have his hand cut off, ritualistically. (And then the cop would get a fat pension from his own tribe, to compensate him for having made this sacrifice for the sake of peace between the tribes.) In the absence of a modern justice system, to mediate between the ‘modern justice system’ tribe and the tribe of citizens, such a proto-justice system is probably second-best, after all.

UPDATE: In comments, everyone seems eager to inform me that this was kind of a weird Grand Jury case. I’m not sure why people assume I don’t read the news before posting. Maybe because of this: “The law heavily tilts in favor of cop defendants in a case like this (by design).” I take this case to be the semi-exception that proves this rule. Normally, we wouldn’t get a Grand Jury at all for a cop shooting in the line of duty. We would get: nothing. In this case, we got a Grand Jury but, in deference to the norm that you don’t indict cops, the prosecutor did his best to damp down his own ham-sandwich-indicting-reality-distortion-field.

HEY OBAMA, I KNOW IT’S A TRADITION AND EVERYTHING, BUT THIS TURKEY PARDONING CEREMONY KIND OF...

HEY OBAMA, I KNOW IT’S A TRADITION AND EVERYTHING, BUT THIS TURKEY PARDONING CEREMONY KIND OF MAKES IT A LITTLE TOO CLEAR THAT THE AMERICAN JUSTICE SYSTEM VALUES A TURKEY MORE THAN BLACK KIDS???

Radio Raheem is still dead: A Ferguson reader

Syreeta McFadden, “Ferguson, goddamn: No indictment for Darren Wilson is no surprise. This is why we protest”

Today, Mike Brown is still dead, and Darren Wilson has not been indicted for his murder. And who among us can say anything but: “I am not surprised”?

… The African American body is still the bellwether of the health, the promise and the problems of the American democratic experiment. The message that the Missouri grand jury has now sent to young African Americans – from Ferguson to my classroom and the rest of the world – is that black lives do not matter, that your rights and your personhood are secondary to an uneasy and negative peace, that the police have more power over your body than you do yourself.

Leonard Pitts, “Video provides evidence of our racial divide”

The shooter’s friends always feel obliged to defend him with the same tired words: “He is not a racist.”

He probably isn’t, at least not in the way they understand the term.

But what he is, is a citizen of a country where the fear of black men is downright viral. That doesn’t mean he burns crosses on the weekend. It means he’s watched television, seen a movie, used a computer, read a newspaper or magazine. It means he is alive and aware in a nation where one is taught from birth that thug equals black, suspect equals black, danger equals black.

Thus has it been since the days of chains, since the days of lynch law, since the days newspapers routinely ran headlines like “Helpless Co-Ed Ravished by Black Brute.” It is the water we drink and the air we breathe, a perception out of all proportion to any objective reality, yet it infiltrates the collective subconscious to such an unholy degree that even black men fear black men.

The Groubert video offers an unusually stark image of that fear in action. Viewing it, it seems clear the trooper is not reacting to anything Jones does. In a very real sense, he doesn’t even see him. No, he is reacting to a primal fear of what Jones is, to outsized expectations of what Jones might do, to terrors buried so deep in his breast, he probably doesn’t even know they’re there.

Ezra Klein, “Officer Darren Wilson’s story is unbelievable. Literally.”

Every bullshit detector in me went off when I read that passage. Which doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen exactly the way Wilson describes. But it is, again, hard to imagine. Brown, an 18-year-old kid holding stolen goods, decides to attack a cop and, while attacking him, stops, hands his stolen goods to his friend, and then returns to the beatdown. It reads less like something a human would do and more like a moment meant to connect Brown to the robbery.

Chauncey DeVega, “White Supremacy in Action”

In all, Darren Wilson did his job when he killed Michael Brown. The historic and contemporary role of police in America is to manage, control, kill, and intimidate black folks, brown folks, and the poor.

The grand jury’s decision that there is no “probable cause” to indict Darren Wilson is an apt summation of how black life is cheap in America, and a white cop who kills a black person is acting in the grand and long tradition of white supremacy and white on black and brown police violence in the United States.

Zandar, “Worth More Than 1,000 Words, Worth Less Than Zero”

This is the system that this morning I am being told I have to “trust” and “put my faith in.” The one that was never meant to protect anyone who looks like me. The system that allowed Darren Wilson to walk, and arranged a public shaming of the victim and his family in a strange tirade where the county prosecutor defended the officer accused of killing an unarmed black man and ripped into the eyewitnesses as being anything but credible. The system that decided that 8 PM local time was the best time to announce the decision after supposedly sitting on that decision for a weekend. The system that took over 100 days to determine that there was no evidence worthy of even sending this case to trial. The system in that photo above, I am being told, I have to “believe in”.

You will excuse me if I withhold that benefit of the doubt. In his testimony, Wilson, a 6’4″ man, referred to Mike Brown as “it”, and “a demon.” He wasn’t human. He was a thing, and there’s no penalty for shooting a thing and so this thing was shot time and time again because it had to be put down, a monster, a beast, a nightmare made flesh.

Jamelle Bouie, “Justifying Homicide”

Which is to say this: It would have been powerful to see charges filed against Darren Wilson. At the same time, actual justice for Michael Brown — a world in which young men like Michael Brown can’t be gunned down without consequences — won’t come from the criminal justice system. Our courts and juries aren’t impartial arbiters — they exist inside society, not outside of it — and they can only provide as much justice as society is willing to give.

Unfortunately, we don’t live in a society that gives dignity and respect to people like Michael Brown and John Crawford and Rekia Boyd. Instead, we’ve organized our country to deny it wherever possible, through negative stereotypes of criminality, through segregation and neglect, and through the spectacle we see in Ferguson and the greater St. Louis area, where police are empowered to terrorize without consequence, and residents are condemned and attacked when they try to resist.

Martin Luther King Jr., in The Other America, 1968

It is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the negro poor has worsened over the last twelve or fifteen years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity.

See also:

• St. Louis Public Radio: “Evidence released by McCulloch”

• Ryan Devereaux, “‘Downright Outright Murder’: A Complete Guide to the Shooting of Michael Brown by Darren Wilson”

• Jelani Cobb, “Chronicle of a Riot Foretold”

• Ramelia Williams, “Until Lynching Becomes Personal”

• Bill Lindsey, “After Ferguson Verdict, I Remember My City’s Last Lynching”

• David Feige, “The Independent Grand Jury That Wasn’t”

• Doktor Zoom, “Darren Wilson Pretty Sure Mike Brown Had Mutant Supervillain Powers”

• Max Fisher, “How we’d cover Ferguson if it happened in another country”

tally-art: New Home Is Where The Internet Is: "What would I...

Zephyr Dearportlaaaand

New Home Is Where The Internet Is: "What would I even do in Portland?"

Follow the link for lots of suggestions! Have you visited or lived in Portland? Leave a comment with your suggestions for first-time visitors! :D

A great guide for the many things you can do in my fair city of Portland!

"this is kind of a general rule. abusers will co-opt extant systems as much as they can. abusers..."

this is kind of a general rule. abusers will co-opt extant systems as much as they can.

abusers will use the framework of poly to abuse. abusers will use the framework of BDSM to abuse. abusers will use the framework of feminism to abuse. abusers will use the framework of PTSD recovery to abuser.

abusers will use WHATEVER FRAMEWORK GETS THEM SEX/ATTENTION/A VICTIM to abuse, because abusers are assholes.

So whenever I hear things like “he’s a great feminist but–” or “we have a poly relationship but–” my radar goes up, because if what comes after the “but” is some kind of magically-justified terrible behavior that no one would flinch from calling abusive on, like, Unreconstructed Non-Feminist Monogamy Caveperson…listen to the behavior, not the framework.

”- J. Preposterice on Captain Awkward

The amazing/awful thing is that I actually used to know a guy who used feminism, poly, BDSM, and...

The amazing/awful thing is that I actually used to know a guy who used feminism, poly, BDSM, and PTSD recovery as tools of abuse. ALL AT ONCE.

"It’s okay if I date anyone I please, but as your Dom I order you to not date [literally every man she knew] because they are misogynist abuse apologists, and you arguing with me on this point is very triggering to me."

…I’m not making this dude up.

im tearing up and crying a bit tbh, as i cant help but think to myself of my own brother, who is the...

im tearing up and crying a bit tbh, as i cant help but think to myself of my own brother, who is the same age

— and a total dope, of course, just a stinky annoying lug who is not a fully formed person yet just this weirdly tall dough blob allowed to make decisions, like a toy boat on the ocean —

and he is safe from this sort of fate. there’s no way around it, around the awful unfairness of it, the injustice of it. that one is allowed to be fallible, awkward, sapling, and the other is dead…

when i was a child, i thought adults were rather foolishly sentimental about children. now that i am even a little older it makes some sense. there is so much difficult about being an adult and we need everyone to make it and help. to see a child murdered at that age, when they were so close to waking up and participating…

we needed them, and they’re gone.

Why Being Trans Could Cost You The House

Christin Scarlett Milloy couldn’t get a mortgage approval, because she couldn’t get a photo ID, because she’s transgender:

I sat on the phone and patiently explained why I can’t provide photo ID. Because I don’t have any. Because the government has destroyed all my previous ID documents and refused to replace them on several occasions. Because I am transgender. Yes, really. No, I don’t think it’s fair, either. Yes, a lot of people are surprised it’s so hard for us, but there it is. No, I really don’t have anything at all. Mmm, OK. Call me back. Goodbye.

We looked into other ways I could prove my identity. It turns out, there aren’t any. What if I show the dozens of letters back and forth between me and the government, where officials explain that my identity is not in question, but they still won’t send me new ID, because I refuse to check “male” on the application form? Apparently that doesn’t count.

How about expired government-issued ID? Back from a simpler time, when the government and I agreed on what my gender should be. I have that; it even has my photo and my old name on it. (Old-name ID presented alongside a legal ”change of name” certificate is considered valid to identify a person by their new name.) But alas, it’s against the rules to accept expired ID, even under exceptional circumstances.

Update from a reader:

Thank you for continuing your coverage of trans related issues. However, don’t you think that the headline that you wrote is over the top? Would you lend money to someone that did not have a proper ID? Seriously. Trans or not, that is nuts. It sounds like real estate lending pre-2008.

Why Uber Fights

In his, to my mind, fair defense of Uber, Mark Suster made a very important observation about the reality of business:

Let’s put this into perspective. As somebody who has to rub shoulders with big tech companies often I can tell you that there is much blood spilled in the competitive trenches of Apple, Twitter, Facebook, Google and so on. Changes to algorithms. Clamping down on app ecosystems. Changing how third-parties monetize. Kicking ecosystem partners in the nuts.

Be real.

It’s a brutally competitive world out there because there are extreme amounts of money at stake. I’ve been on the sharp end of it and it doesn’t feel nice. And I pick myself back up, dust off and think to myself that I need to think through the realpolitik of power and money and competition and no matter how unpleasant it is – it’s a Hobbesian world out there. It ain’t pretty – but it’s all around us.

This is particularly relevant to Uber: the company is looking to raise another $1 billion at a valuation of over $30 billion, and, as I wrote when the company raised its last billion, they are likely worth far more than that. Still, though, skeptics about both the size of the potential market and the prospects of Uber in particular are widespread, so consider this post my stake in the ground1 for why Uber – and their market – is worthy of so many sharp elbows. I expect to link to it often!

There are three perspectives with which to examine the competitive dynamics of ride-sharing:

- Ride-sharing in a single city

- Ride-sharing in multiple cities

- Tipping points

I will build up the model that I believe governs this market in this order; ultimately, though, they all interact extensively. In addition, for these models I am going to act as if there are only two players: Uber and Lyft. However, the same principles apply no matter how many competitors are in a given market.

Ride Sharing in a Single City

Consider a single market: Riderville. Uber and Lyft are competing for two markets: drivers and riders.

There are a few immediate takeaways here:

- The number of riders is far greater than the number of drivers (far greater, in fact, than the percentage difference depicted by this not-to-scale sketch)

- On the flip side, drivers engage with Uber and Lyft far more frequently than do riders

- Ride-sharing is a two-sided market, which means there are two places for Uber and Lyft to compete – and two potential opportunities for winner-take-all dynamics to emerge

It’s important to note that drivers in-and-of-themselves do not have network dynamics, nor do riders: Metcalfe’s Law, which states that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users, does not apply. In other words, Uber having more drivers does not increase the value of Uber to other drivers, nor does Lyft having more riders increase the value of Lyft to other riders, at least not directly.

However, the driver and rider markets do interact, and it’s that interaction that creates a winner-take-all dynamic. Consider the case in which one of the two services – let’s say Uber – gains a majority share of riders (we’ll talk about how that might occur in the next section):

- Uber has a majority of riders (i.e. more demand)

- Drivers will increasingly serve Uber customers (i.e. more supply)

- More drivers means that Uber’s service level (i.e. car liquidity) will improve

- Higher liquidity means that Uber has a better service, which will gain them more riders

In this scenario Lyft by necessity moves in the opposite direction:

- Lyft has fewer riders (i.e. less demand)

- Drivers will face increasing costs to serve Lyft riders:

- If there are fewer Lyft riders, than the average distance to pick up a Lyft rider will be greater than the average distance to pick up an Uber driver; drivers may be better off ignoring Lyft pickups and waiting for closer Uber pickups

- Every time a driver picks up a rider on one service, they need to sign out on the other; if the vast majority of rides are with one service, this, combined with the previous point, may make the costs associated with working for multiple services too high2

- Drivers will increasingly be occupied serving Uber customers and be unavailable to serve Lyft customers (i.e. less supply)

- Fewer drivers means that Lyft’s service level (i.e. car liquidity) will decrease

- Lower liquidity means that Lyft has an inferior service, which will cause them to lose more riders

The end result of this cycle, repeated over months, looks something like this:

There are three additional points to make:

It doesn’t matter that drivers may work for both Uber and Lyft. If the majority of the ride requests are coming from Uber, they are going to be taking a significantly greater percentage of driver time, and every minute a driver spends on a rider job is a minute that driver is unavailable to the other service. Moreover, this monopolization of driver time accelerates as one platform becomes ever more popular with riders. Unless there is a massive supply of drivers, it is very difficult for the 2nd-place car service to ever get its liquidity to the same level as the market leader (much less the 3rd or 4th entrants in a market)

-

The unshaded portion of the “Riders” pool are people who regularly use both Uber and Lyft. The key takeaway is that that number is small: most people will only use one or the other, because ride-sharing services are relatively undifferentiated. This may seem counterintuitive, but in fact in markets where:

- Purchases are habitual

- Prices are similar

- Products are not highly differentiated

…Customers tend to build allegiance to a brand and persist with that brand unless they are given a good reason to change; it’s simply not worth the time and effort to constantly compare services at the moment of purchase3 (in fact, the entire consumer packaged goods industry is based on this principle).

In the case of Uber and Lyft, ride-sharing is (theoretically) habitual, both companies will ensure the prices are similar, and the primary means of differentiation is car liquidity, which works in the favor of the larger service. Over time it is reasonable to assume that the majority player will become dominant

I briefly mentioned price: clearly this is the easiest way to differentiate a service, particularly for a new entrant with relatively low liquidity (or the 2nd place player, for that matter). However, the larger service is heavily incentivized to at least price match. Moreover, given that the larger service is operating at greater scale, it almost certainly has more latitude to lower prices and keep them low for a longer period of time than the new entrant. Or, as is the case with ride-sharing, a company like Uber has as much investor cash as they need to compete at unsustainably low prices

In summary, these are the key takeaways when it comes to competition for a single-city:

There is a strong “rich get richer” dynamic as drivers follow riders which increases liquidity which attracts riders. This is the network effect that matters, and is in many ways similar to app ecosystem dynamics (developers follow users which which increases the number and quality of apps which attracts users)

It doesn’t matter if drivers work for both services, because what matters is availability, and availability will be increasingly monopolized by the dominant service

Riders do not have the time and patience to regularly compare services; most will choose one and stick with it unless the alternative is clearly superior. And, because of the prior two points, it is almost certainly the larger player that will offer superior service

Ride Sharing in a Multiple Cities

It is absolutely true that all of the market dynamics I described in the previous section don’t have a direct impact on geographically disperse cities, which is another common objection to Uber’s potential. What good is a network effect between drivers and riders if it doesn’t travel?

There is, however, a relationship between geographically disperse cities, and it occurs in the rider market, which, as I noted in the previous section, is the market where the divergence between the dominant and secondary services takes root. Specifically:

Pre-existing services launch with an already established brand and significant mindshare among potential riders. Uber is an excellent example here: the company is constantly in the news, and their launch in a new city makes news, creating a pool of riders whose preference from the get-go is for Uber

Travelers, particularly frequent business travelers, are very high volume users of ride-sharing services. These travelers don’t leave their preferences at home – when they arrive at an airport they will almost always first try their preferred service, just as if they were at home, increasing demand for that service, which will increase supply, etc. In this way preference acts as a type of contagion that travels between cities with travelers as the host organism

Most important of all, though, is the first-mover effect. In any commodity-type market where it is difficult to change consumer preference there is a big advantage to being first. This means that when your competitor arrives, they are already in a minority position and working against all of the “rich get richer” effects I detailed above.

This explains Uber and Lyft’s crazy amounts of fundraising and aggressive roll-out schedules, even though such a strategy is incredibly expensive and results in a huge number of markets that are years away from profitability (Uber, for example, is in well over 100 cities but makes almost all its money from its top five). Starting out second is the surest route to finishing second, and, given the dynamics I’ve described above, that’s as good as finishing last.

Tipping Points

What I’ve described up to this point explain what has happened between Uber and Lyft to-date. Still, while I’ve addressed many common objections to Uber’s valuation in particular, there remains the question of just how much this market is worth in aggregate. After all, as Aswath Damodaran, the NYU Stern professor of finance and valuations expert detailed, the taxi market is worth at most $100 billion which calls into question Uber’s rumored $30 billion valuation.

However, as Uber investor Bill Gurley and others have noted, Damodaran’s fundamental mistake in determining Uber’s valuation is to look at the world as it is, not as it might be.4 Moreover, this world that could be is intimately tied to the dynamics described above. I like to think of what might happen next as a series of potential tipping points (for this part of the discussion I am going to talk about Uber exclusively, as I believe they are – by far – the most likely company to reach these tipping points):

-