Are you going to spend $10,000 on the new Apple Watch Edition?

No, right? Me either. Maybe you can’t afford it. Maybe you could drop $10k on a device but it seems repugnant or simply ridiculous. Maybe you don’t wear a watch at all; I sure don’t, and at this stage I don’t intend to start.

Maybe everyone you know agrees:

Overpriced. Who the hell would buy that? Nobody. Apple jumped the shark. You can’t upgrade the innards and jesus h, it’s gold, what a frigging waste, it’ll be obsolete in a year. Who the hell would buy a $10k watch with planned obsolence? Nobody. What the hell were they thinking?

Right?

Wrong. None of that makes a lick of difference.

The Apple Watch is going to be huge.

It’s gonna sell like hotcakes. Yes, even the $10k ones.

Maybe especially the $10k ones.

I can tell from here you don’t believe me. That’s fine. You probably didn’t believe anyone would pay $399 for an MP3 player that couldn’t even hold half as much as the Creative Jukebox. You probably knew the iPhone would flop because it didn’t have 3rd party apps, 3G, GPS, multi-tasking or even friggin’ copy & paste.

You probably thought the iPad was ugh, just a big iPhone, who cares.

Sarcasm: Great track record you’ve got there.

Reality: You’ve got a problem.

It looks like…

- you don’t understand yourself

- you don’t understand buyers

I can’t help you with column A right now, but I can tell you that if you think the Apple Watch will fail it’s because you don’t understand buyers.

The obvious question is also the wrong question:

“Who buys a $10,000 watch?”

Lots of people. Luxury watches have been a status symbol for a loooong time.

“But those are real watches. They don’t become unusable in 2-3 years.”

Not true, not always, but anyway, the Apple Watch is as much a watch as the iPhone is a phone.

The Apple Watch is merely watch-adjacent.

It will not seduce buyers who pop a tent for a fine complication. It simply can’t deliver, and it doesn’t have to.

Repeat: the Apple Watch is not actually a watch.

The watch fanatics who complain about the Apple Watch are the same as the tech fanatics who complained when Apple killed SCSI, serial, the floppy, the optical drive. Those things were all necessary and mandatory right up to the point that they weren’t.

But obsolescence. And engraving!? RESALE VALUE!?!

No, no, no. People who buy things like this don’t behave the way you think they do.

No, the Apple Watch Edition’s internals are not swappable. Yes, it will go obsolete, like any piece of tech hardware, only it’ll be wrapped in gold with a sapphire screen. And doubly so if you engrave it to that special someone.

That’ll stop anyone from buying it. Right? Wrong.

Here’s a better question:

How many people drop $10,000 on things that don’t last?

Now we’re talking. Say you’ve got money burning a hole in your pocket.

What does $10k get you that won’t last very long?

Here was my first thought: Two round trip, first class airplane tickets to Europe. How long does that last? 32 man-hours. That’s about $315 per hour.

Do people buy first class tickets to Europe? Yes, yes they do.

What else?

Pour it down the tubes…

From what I’ve read, $10k would cover 1.5 to 2.5 regularly scheduled maintenance visits for a Ferrari or Lamborghini. Hello oil and spark plugs, bye bye money.

Guess poor ol’ Ferrari and Lambo are in dire straits because nobody buys them cuz they cost so much to maintain. What? They’ve been doing business this way for decades? Ferrari appears to have had its best year ever in 2014?

You don’t say.

How about something that literally disappears into thin air?

I have a 1,700 square foot home and our gas/electric costs on average $400-600 a month. That’s $5k to $7k a year. Yes, it hurts, but it hurts less than fucking up the Historically Significant interior for more R-value, and I knew that going in.

Now, I have a poorly insulated but smallish house, by American standards. Especially by the standards of people in my income bracket.

Just imagine what it costs to keep a 5 bed / 4 bath / heated pool / hot tub / 4 car garage lit, warm and cool over a year. Does that swell into Apple Watch Edition territory? Yessirreebob.

And don’t forget just how many people have second homes. It’s more than you think.

What about a durable good that becomes un-en-durable in 18-24 mos?

I know jack about fashion but, obviously, handbags. I read enough to know that many women lust after a Birkin bag. Birkins start at $10,000. Hey, what a coincidence!

Now the $10k Birkin is apparently an entry-level model. I saw it described as “the basic bitch Birkin.” Alliteration aside, imagine spending $10k on a luxury item and knowing that everyone who gets it will know you got the cheapest possible one. Ouch.

And while Birkins, allegedly, are immune to the rapid fashion cycle, other luxury handbags aren’t. Those don’t hold their value and they go out of style — blip! — in a matter of a year or two.

And yet they sell, sell, sell at $2,000 to $5,000 a pop.

We're so US focused we're missing the entire narrative of Apple as a status symbol & luxury brand in emerging markets, especially China.

— Crystal Beasley (@skinny) March 9, 2015

Yes, people blow $10k in a thousand curious ways

People blow lots of money on things you consider ludicrous. Things that fly, burn, convect, wear, or fade away as quickly (if not more so) than a $10k gold digital watch.

Things that, objectively, offer far less utility.

I hope it’s obvious by now that the hyper-concern of “resale value” simply doesn’t apply to this category of buyers.

Conclusion: You are not the Apple Watch Edition customer.

And that’s fine. Unless you’re an investor or a pundit, it doesn’t matter that you got it dead wrong.

But it matters a lot in your business.

Here’s the real reason I’m writing a think piece on a $10,000 gold accessory that I would never buy:

I specialize in helping my students learn to create things that other people will actually buy. And this is the most critical lesson they struggle with.

You are not your customer.

Oh, you get told:

- “Scratch an itch!”

- “Dogfood!”

- “Build something you’d buy!”

- “Find your niche!”

Maybe you walk around thinking things like:

- “Developers don’t buy things.”

- “Email newsletters? People still write those?”

- “Nobody would pay for this.”

Bullshit.

Unless you’ve done research, every opinion you have about what people will or won’t buy comes straight from your butt.

You say you won’t buy an Apple Watch. Fine, I believe you. (Although… perhaps you said the same thing about iPods, iPhones and iPads.)

It doesn’t matter, though, whether you buy or not. Lots and lots of other people will.

Let me repeat: You are not your customer. There’s only one of you. You won’t be paying yourself.

Your buy-in doesn’t determine success.

You are not a litmus test for the universe. You are not an archetype. Most people aren’t like you at all, and you don’t seem to understand that they exist.

You can only know your customers by their actions.

And I can guarantee you that my prediction of their actions is better than yours because:

- I have been following Apple pundit predictions vs actual sales outcomes for 15 years now

- I have known many different types of wealthy people over the years, and I’ve watched how they behave

- I took a few minutes to understand how luxury markets work and, by extension, how luxury audiences behave

- I even googled “Birkin bag” and read what Birkin buyers have to say, and investigated how much they pay new and even used

That’s how I know about the fanaticism for luxury watches (which I don’t wear), the price of first class tickets (which I don’t buy), and the high-fashion handbag cycle (which I have zero interest in).

That’s how I know that extra complicated complications have their own cachet in the watch world. That Ferrari is doing gangbusters (despite their maintenance cost). And how I know that Christie’s has a history of auctioning off second-hand Birkins (unlike other brands), and that the $10k Birkin is for “basic bitches.”

And, because I know what I’m doing, this took me all of 30 minutes to find this out.

That’s the power of research.

It informs your opinions so you can say things that are true and do things that will work. And quit wasting time.

Anything else is just farting from the mouth.

Want to learn how to do what I do?

This research, real-world, what do people really do and buy shit? It’s all I do all day. I do it for myself, and I teach it to others. Here on my blog, and in our Stacking the Bricks podcast.

If you liked this no-BS essay, you will love my 7-part guide. You’ll see why and how you should eviscerate 99% of business “common sense.”

Drop your name in the box, and get it for free:

Get our 7-day no-BS guide to avoiding common startup mistakes

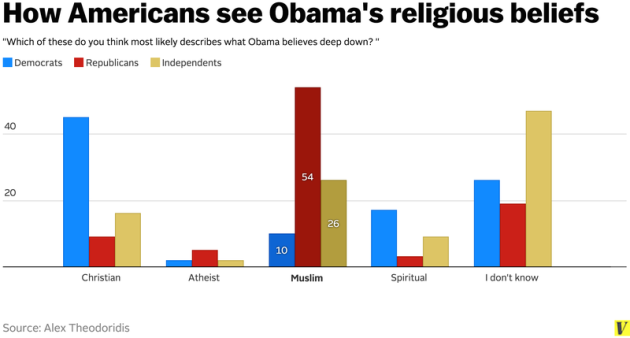

Alex Theodoridis of the University of California at Merced asked Republicans, Democrats, and Independents

Alex Theodoridis of the University of California at Merced asked Republicans, Democrats, and Independents