Enlarge / The Enterprise, caught in the wake of a temporal vortex, witnesses the Earth, assimilated long ago, in the altered timeline.

Paramount Pictures

We're at the start of what should be a big year for Star Trek. The franchise will celebrate its 50

th anniversary this fall, but 2016 also brings a new movie (

Star Trek Beyond), the

recovery of long-lost documents belonging to Gene Roddenberry, and the development of (finally!)

a new series set to launch in January 2017.

It’s no secret that we here at Ars love (and sometimes hate) our Star Trek. With so much time having elapsed since the original series first aired—and with so much time spent watching/reading/thinking through it all—we felt it was about, well, time to thoroughly explore one of our favorite Trek staples: time travel.

Time travel, while perhaps one of the most interesting devices in the series, is also confusing, befuddling, and inconsistent. In the words of Captain Janeway, “the future is the past, the past is the future; it all gives me a headache.”

While we can’t get too deep into the purported mechanisms behind Trek time travel—they rely on things like “chronotons” whose nature real-world science has sadly yet to discover—it's still interesting to ponder time travel's effects. How does it affect the present? Is interference with the past a predestined part of history? Do alterations in the past get mixed into the current timeline?

Before examining the source material, it's important to acknowledge others have taken on these questions, notably Trek novelist Christopher L. Bennett. His detailed work ties together wide swaths of the Trek canon with real-world physics (and some extrapolations from real physics), all with the goal of developing an overarching theory of Trek time travel. The story of time travel in Trek wouldn’t be complete without discussion of his conclusions, but don't fret if you haven't finished all that pre-reading. We’ll take you through some of his conclusions as well.

As Janeway once put it, “Let's get started before my headache gets any worse.”

Consistent universe

Enlarge / Data, with the severed, long-buried head of his "future" self.

Paramount Pictures

The “consistent universe” is a time travel idea present in plenty of science fiction—and occasionally in Trek—in which going back to the past doesn’t change the future. Instead, your attempts to change history were always part of the timeline. If you go back and try to kill Hitler, for example, your attempt might fail and you might realize that you had read about your own attempt in school as a child.

Perhaps the best example of this in Trek is The Next Generation (TNG) episode “Time’s Arrow,” in which the Enterprise is recalled to Earth upon a new archaeological discovery: Data’s head, buried for centuries in San Francisco. Immediately, Picard hopes to alter Data’s fate, but Data believes the outcome is inevitable.

"At some future date, I will be transported back to 19th century Earth, where I will die," is how Data puts it. "It has occurred. It will occur."

Over the course of a fascinating episode involving time-traveling, neural energy-sucking aliens, and Samuel Clemens, we find that Data’s right. Luckily, it’s not the end for Data, as the future version of his head—the one that’s been buried for centuries—is reattached to his body and repaired.

This is a time loop; the decisions made by the Enterprise crew are caused by the discovery of Data’s head, and they in turn cause his head to be lost in the first place. Time loops, and thus inevitable fates like this one, are possible in a consistent universe because nothing can change what’s happened. If Picard and crew had succeeded in saving Data from his fate, his head never would have been found in the first place.

The Deep Space Nine (DS9) episode “Past Tense” also has elements of this approach. Captain Sisko and Dr. Bashir go back in time to the 21st century and get stuck in a sealed-off district for homeless people. By the end of the episode, Sisko meets Gabriel Bell—the man who famously led riots that ended this kind of injustice—and sees him killed before Bell can lead those riots. As such, Sisko takes his place.

Witnessing the timeline shifting around their starship, the Defiant, the crew send rescue missions until they find Sisko and the timeline is restored.

Once Sisko and crew get back to the Defiant, Bashir goes into the ship’s historical database and finds a picture of Gabriel Bell... which turns out to be a picture of Sisko. The ship was shielded from changes to the timeline, which means that the picture of Sisko as Bell was in their database before the changes took place. Sisko had always been Bell.

Admittedly, the concepts of “changing the past” and witnessing an altered timeline conflict with the idea of the consistent universe. But the episode nonetheless has a consistent time loop that just happens to include the timeline changing back and forth.

Similarly, the TNG episode “Tapestry” has both a consistent effect and a changing timeline. Q gives Picard the chance to go back to his youth and make better choices. Once Picard realizes his error (getting into the fight with the Nausicaan and getting stabbed in the heart was somehow the best outcome for him), he’s given the opportunity to restore his original choices. This time, as he’s stabbed through the heart, he laughs. Interestingly, it had been mentioned in a previous episode, “Samaritan Snare,” that he had laughed when stabbed—indicating that his experience in the past had always been a part of Picard’s history.

The consistent universe is seen even more clearly in the original series (TOS). The episode “Assignment: Earth” has the Enterprise interfering in an alien secret agent’s mission to 20th century Earth, with Kirk unsure whether the agent’s actions will destroy his timeline or secure it as the agent (Gary Seven) claims. In the pivotal moment, Kirk decides to trust Seven, allowing him to detonate a nuclear warhead before it impacts.

Seven, making his report to his alien superiors, concludes that the mission was completed despite the Enterprise’s interference in history. Spock, however, corrects him, saying that the Enterprise’s historical records show these events occurring exactly as they did, with a nuclear warhead exploding 104 miles above the surface. Thus, Spock explains, the “interference” is actually a part of the way things were supposed to happen.

There are a few other examples of consistent universe time travel in Trek, such as the Voyager (VOY) episode “Parallax,” in which the ship is lured into a singularity by a distress call which turns out to be Voyager’s own time-reflected distress call. Or DS9’s “Little Green Men,” which features Quark, Nog, and Rom crash-landing in 1947 to become the famous Roswell, New Mexico aliens. Their actions don’t seem to change the timeline as far as we can tell, and it’s probable that the Roswell incident had always taken place in the Trek universe (though, to be fair, we can’t be sure).

The consistent universe is an interesting device because we feel deep discomfort at not being able to change the course of events through our choices. If my attempt to kill Hitler is already part of history, there’s no way it can be undone.

In a physics sense, this is also the simplest time travel device. Time loops with simple particles are, in principle, totally consistent. In fact, there isn’t actually any difference between a time loop with these particles (a particle, moving in a loop, goes back in time to arrive at its starting point in time, becoming its past self) and a situation where a pair of particles, a particle and its antiparticle, are spontaneously created and annihilate soon after. Those are two equally valid ways of describing the same situation. In the second version, the antiparticle moving forwards in time is equivalent to the particle moving backwards in time.

But this situation no longer makes sense when you consider complex systems like human beings rather than individual particles. Imagine there’s a guy who comes out of a time portal, walks around in a circle, kicks a ball, and then enters the same portal from the other side. He travels back in time to when he emerged and does the same thing again.

The only trouble is even though he returns to the same time, he has changed from his experience. He remembers kicking the ball and might not feel like doing it the second time around. Additionally, the more times he does this, the more tired he’ll get. He’ll age. This situation worked fine with a particle, but it's not quite the same with a human.

After all, if I were to go back and try to kill Hitler, having read up on my attempt in the history books, what’s to stop me from trying something different the second time?

Luckily, the "consistent universe" isn't the only approach to time travel. In fact, it's not even Star Trek most common device. That honor is held by...

The ever-changing timeline

Enlarge / ]The Enterprise crew encounter the Guardian of Forever.

CBS

This is the stark opposite of the consistent universe. Interactions with the past are not “part of the way things were supposed to happen,” so they can undermine the way things have happened. With an ever-changing timeline, a time traveler might return from the past to find that his present is no longer the one he remembers.

The classic example of this comes in the TOS episode “The City on the Edge of Forever,” often hailed as the best episode in all Trek. Dr. McCoy uses a sentient time portal known as the Guardian of Forever, which can lead to any period in history, and he travels back to 1930. His actions change the timeline such that the Enterprise never existed.

Oddly, though, Kirk and the rest of the landing party still exist on the planet’s surface. (This might be explained because the temporal distortions surrounding the planet shielded them from being erased with the rest of their timeline.)

The crux of the episode is that Edith Keeler, a social worker with grand ideas of a peaceful future—the very type future that Star Trek embodies—must die, ironically, for that future to come about. McCoy’s interference saved her, but that's the change that erased the original timeline. Once Kirk and Spock restored her death to history, the Enterprise, along with the rest of the Federation, reappears.

This form of time travel was exemplified in the movie Star Trek: First Contact. Like “City on the Edge,” First Contact has the Enterprise crew shielded from the erasure of the timeline around them, allowing them to witness an Earth long since assimilated by the Borg. They then to go back in time to stop the assimilation.

A truly fascinating look into time travel in the Trek universe comes in Voyager’s “Year of Hell, ” which showcases a different version of the changing timeline. In this episode, a Krenim man named Annorax has created a weapon ship that can erase whatever it fires at from history. The ship itself is shielded from the changes it causes to the timeline, but the rest of the universe is vulnerable.

But Annorax finds that changing history is a lot dicier than expected. Erase an asteroid and you've undone every interaction that asteroid has ever had; in the new timeline, this will have unintended consequences. Annorax suffered for this, as his meddling with history inadvertently erased his wife from existence. But like Captain Ahab, he can't stop his quest for the perfect timeline.

The threat only ends when Voyager manages to erase the weapon ship from history, and in the resulting timeline none of its temporal attacks occurred. As a result, everything erased from the timeline is restored, including Annorax's wife.

The episode showcases how tightly woven history is and how even timelines can depend on each other. Apparently, altering the timeline which altered the timeline also affects the timelines it affected.

Another example of this is Star Trek: Enterprise's "

The idea of a changing timeline is in some ways more counterintuitive than the consistent universe. It's exactly the kind of time travel that can lead to paradoxes. After all, if changing the past can really change everything after it, then someone could kill his grandfather and erase himself from existence. Which, of course, would prevent himself from killing his grandfather.

For some reason, this is never a problem in Trek. In episodes where the timeline changes, there always seems to be a definite outcome. But maybe there's more to this idea than is immediately apparent. After all, just because the timeline's changing doesn't mean there can't be a consistent universe... after a fashion.

It says, ButtFeed...

It says, ButtFeed... Apparently, Mad Max and Mario Kart make a

Apparently, Mad Max and Mario Kart make a

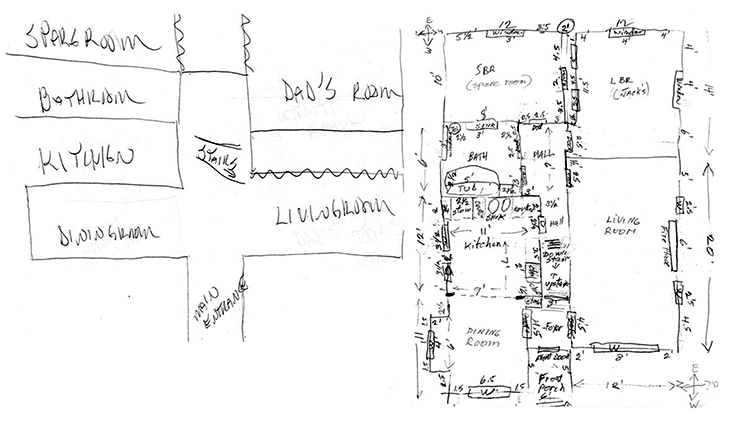

Homing in: A distorted home map drawn by a subject with DTD is shown on the left. The actual map is on the right. Neuropsychologia

Homing in: A distorted home map drawn by a subject with DTD is shown on the left. The actual map is on the right. Neuropsychologia