Submitted by:

Shared posts

Pablo the Puppy Tried to Clean up His Own Mess and Honestly We're Impressed

You should see the coffee table...

After seeing their new wallpaper and bookshelf, Gary and Elaine agreed that next time they would hire a less literal designer.

Review: Hope Sandoval & The Warm Inventions, 'Until The Hunter'

Nearly 30 years into her career, Mazzy Star's singer still takes her time in the pursuit of beauty. Here, she works with My Bloody Valentine's Colm O'Ciosoig, as well as guests like Kurt Vile.

This is the Greatest Note of All Time to Leave For Someone Who Sucks at Parking

College Papers are Tough, Writing Them Drunk is Even Tougher

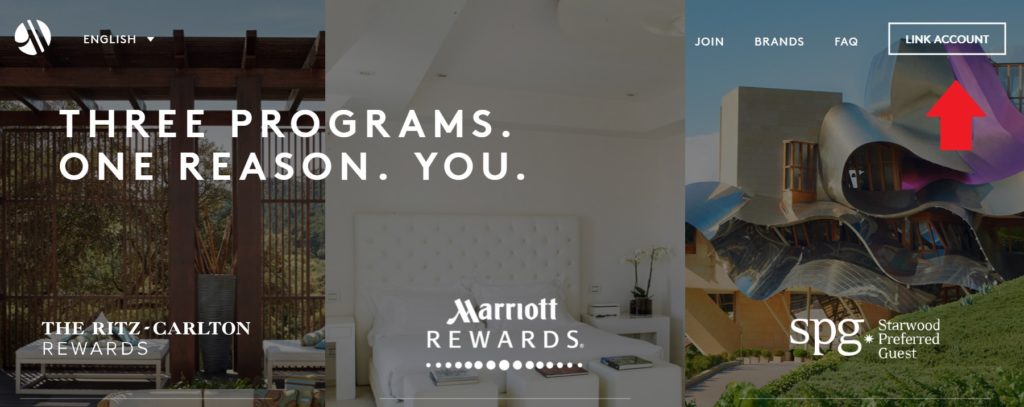

How to Link Your Starwood and Marriott Accounts — and Get Elite Status Instantly

Marriott has acquired Starwood, and on day one they’re already making it possible to link frequent guest accounts, match status, and transfer points between programs.

Marriott and Starwood are still separate, the programs are still independent — you earn and redeem Starwood points at Sheraton, Westin, etc. and you earn and redeem Marriott points at Marriott, Renaissance, etc. — but you can move your points back and forth and elite customers of one can be treated as elites with both.

Continue reading How to Link Your Starwood and Marriott Accounts — and Get Elite Status Instantly...

Comments

- @TC: Sounds like an interim answer. I did the same as a MR ... by Retired Lawyer

- Just linked MR Lifetime Platinum to SPG Platinum and called SPG ... by TC

- I don't know how long the link was working but it is down now. by john

- With •Marriott Rewards Gold = SPG Gold Looks like SPG ... by Randy

- Hmm. Any reason not to link at this point? The status match is ... by Andyandy (The Points Ninja)

- Plus 3 more...

Related Stories

This Fifth-Grader's Rules For Her Crush Might Be the Perfect Thing For Anyone Dealing With an Elementary-Level Crush

That Might Be a Little Too Honest for a Tardy Excuse

I Have a Feeling This 2-year-old Is Going to Grow Up Into Something Evil

AkasicThis is not normally an answer for the trolly problem. Ha.

Bravo to the University of Chicago

From the University of Chicago letter welcoming students:

…Earning a place in our community of scholars is no small achievement and we are delighted that you selected Chicago to continue your intellectual journey.

Once here you will discover that one of the University of Chicago’s defining characteristics is our commitment to freedom of inquiry and expression. … Members of our community are encouraged to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn, without fear of censorship. Civility and mutual respect are vital to all of us, and freedom of expression does not mean the freedom to harass or threaten others. You will find that we expect members of our community to be engaged in rigorous debate, discussion, and even disagreement. At times this may challenge you and even cause discomfort.

Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own….

The post Bravo to the University of Chicago appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Chuck Klosterman on But What If We're Wrong

Chuck Klosterman, author of But What If We're Wrong, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the possibility that things we hold to be undeniably true may turn out to be totally false in the future. This wide-ranging conversation covers music and literary reputations, fundamentals of science, and issues of self-deception and illusion.

Chuck Klosterman, author of But What If We're Wrong, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the possibility that things we hold to be undeniably true may turn out to be totally false in the future. This wide-ranging conversation covers music and literary reputations, fundamentals of science, and issues of self-deception and illusion.

Readings and Links related to this podcast episode

|

Related Readings

HIDE READINGS |

|---|

This week's guest:

|

Highlights

| Time |

Podcast Episode Highlights

HIDE HIGHLIGHTS |

|---|---|

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: July 21, 2016.] Russ: So, I want to start with the general question that runs through the book: Why are we so confident about so many things that are likely to turn out to be incorrect? So, there are really two parts to that question: Why is it that there are a lot of things that are going to be incorrect, in the future, and yet we still think they are obviously true now? Guest: Well, I suppose maybe there is a two-sided answer to this. Part of the reason is that we sort of exist in this world where we live as if we are right about how we view reality, even though maybe in the abstract we'll be like, 'Well, of course in the future we'll think differently; but we are going to live as though we are right, now.' Part of it has to do, out of necessity. I have sort of the luxury of writing a book where I can think about these ideas, and how people who are not yet born will look back on this time. I think for a lot of people it would be sort of an impractical way to live, to sort of constantly be second guessing every belief they have, or everything that they assume to be true. There's a certain utility in just working like, 'Well, the way we view the world is how the world is.' I think maybe the other, more insidious, problematic reason is that as we've kind of democratized communication and we have radically expanded the number of people who can be part of conversations about politics and sports and culture and science and the economy--all these sort of big ideas, we've really increased the number of people who can be actively involved in the public discourse--it has become much more difficult to get attention in that specific kind of attention economy. So, what seems to have emerged is this idea that expressing a high degree of certitude dovetails with some kind of authority. In other words, simply just having the confidence that you're right somehow gives your argument a little more merit, and of course as this has proliferated, it has had, you know, like the opposite effect, in the sense that people act more confident about ideas that they themselves understand to be fragile and probably incorrect. Russ: Yeah. And I may have remarked on this in the past on the program: when somebody says something with total certainty to me, 'There's no doubt that--blah, blah, blah' and I say, 'Are you sure?', they'll immediately back down. I'm thinking--and I'll find myself backing down. If I find myself saying something hyperbolic about who is going to win the World Series or who is going to win the Presidential election or what this policy's effects are going to be. And you find yourself sometimes overconfidently stating something, because, yeah, it gets attention. And it makes you feel good, too, by the way. And yet-- Guest: It's become a way of speaking. It's just like you say how back down when you bring this up: it doesn't surprise me. When the person says, 'There's no doubt that--' whatever the case may be, they're not really saying 'I have zero doubt in this,' or 'The world has zero doubt.' What they're basically saying is 'I believe this, and I want to make the statement stronger.' Russ: Yeah: 'I want to put this out there.' Guest: Yeah. And because those ideas are really question [?], after a while there does seem to be this illusion, this sense, that these things that are expressed to be without doubt, well maybe they are--maybe we just have to accept them. Maybe we just have to sort of unilaterally look at these things as kind of subjective truth--which is kind of a paradox in itself. Russ: Yeah, oxymoron. |

| 4:39 | Russ: There's an irony here, which I thought about a lot while I was reading the book. Which is: We live in a time of unprecedented access to information, unprecedented access to people's opinions about that information. And yet, it seems, perhaps ironically--maybe it's not ironic--but it seems to me that it gets harder and harder to figure out what really is true. And the Internet, which is this glorious information machine is in many ways making navigating those challenges more challenging. Guest: Yeah. There's really two ways to look at this, I suppose. You could say that the Internet is creating more avenues for ideas; and that now instead of having only kind of canonical ideas or sort of one mainstream belief, we now have every possible idea existing in the world and people can access all these ideas with the same degree of fluency. And you could think like this is really going to give us a better sense of what the world is like, because you are hearing more voices. But at the same time, for the most part people are kind of supporting the same general belief system. The same general ideas are just being repeated in lots of different ways. And what that may do is actually make the things we think now harder to contradict later, or harder to disprove later. If you go back to something, a belief from the late 1700s or whatever, you'll find the idea expressed; you might find some critics of the idea; you might find a little more information about the person who presented the idea. But that's pretty much it. For the most part, that idea can be reinterpreted because we have just limited amounts of information about it. Now, every individual, every idea, every sort of concept that exists is remarked upon and analyzed and written about by so many people that it almost calcifies that perception. Like, I don't know if it will be as easy to go back and reinterpret a novel from this period the way we can go back and interpret a novel from the early modernist period or whatever, and say like this means something different now. I don't know if that will be as easy because there's so much information about the present tense. Russ: Yeah. It's really--it's just a fascinating thing about your book, because it really makes you think about how much we know and how much we think we know that's wrong. I'm a big fan of humility, and your book did humble me a little bit--even made me a little more humble than I like to think I am intellectually. |

| 7:23 | Russ: So, there's an incredible range of topics in the book: literature, rock music, physics, football, lots more. I want to start with science: 1600. You contrast Brian Greene with Neil deGrasse Tyson: why is 1600 a possibly important date in thinking about whether science has it right or not? Guest: Well, that's really the perception of Tyson. Of the two guys--it's kind of strange: I interview two scientists and they are very high-profile scientists. So, they are already sort of outside of the norm. They exist in this different world where their job, really, is to explain complicated ideas in a mainstream way. But as it turned out, they kind of worked as like two good--not necessarily adversaries-- Russ: as foils-- Guest: Yeah, yeah. And Tyson's thing is that, around 1600, a lot of important things happened: the invention of the telescope, the invention of the microscope. The main thing was sort of the adoption of the scientific method as sort of the way we understand the world. Prior to this science had probably had more of a relationship with philosophy than it did with math. Russ: Correct. Guest: And from 1600 on it was different. So he believes that, this idea of paradigm shift--sort of the idea that maybe we'll believe something about the scientific world for hundreds of years and then shift our ideas completely--he argues that that is over. That the Copernican revolution, all of that, that was the last time that that was going to happen. And that from this point forward, all we're going to do is sort of hone the ideas we already have. We'll get a better understanding of how old the universe is or how gravity operates or any of these things: that there isn't going to be another big shift. Whereas, Brian Greene was more like, 'Well, it's really hard to argue that because the history of ideas basically is the history people being wrong. And we would certainly not be the first generation of people to assume that this time we got it right. So, the end of sort of being, you know, like the two ideas almost personified: one of which being like, 'Well, we've been wrong in the past; this time we are right and we're slowly getting better'; or, 'We've been wrong in the past; we'll probably be wrong in the future; but there's no way of knowing that while we're still inside the system'. Russ: Yeah. I had two thoughts. I'm more of a Brian Greene kind of guy--who is the skeptic. But I had two thoughts while I was reading that. One is ulcers--you know, we thought we understand that ulcers related to stress and it turns out it's a bug. Right? A lot of things in medicine get reversed. Now, of course, Tyson's really talking about cosmology and physical science more than, say, certain types of applications. Then also I thought about plate tectonics. We really--that was, you know, a shockingly ridiculous theory that 'Oh, because Africa and South America look like they've been together'--well, actually they probably did fit together. Or how the dinosaurs died. Those are things that happened way after 1600, where received wisdom got just sort of totally shocked. Right? Guest: How the dinosaurs lived, as much as how they died. But here's the thing: the question becomes--these things[?] you just mentioned, ulcers, plate tectonics, the age of dinosaurs, all these things--those ideas have clearly changed. The question becomes: Did they change in the way Tyson describes them, or did they change in the way that Greene sort of speculates that they could change? In other words, is the idea that our understanding of ulcers now is that taking a core idea and getting better and better and better and better at understanding it. In other words like, taking the same general idea and just getting it-- Russ: refining it-- Guest: more accurate? Or, are we reversing some thought? Like, we thought that there was a time not that long ago in Scandinavia really not that long ago where there were some people who were like, 'Well, you know, the reason people get sick, we used to think it was gods, but now we know it's gnomes and trolls.' Russ: Yeah, that's one of my favorite [?]-- Guest: So now we [?] better-- Russ: One of my favorite lines in the book, by the way. Guest: Now that to me is closer to the Brian Greene thinking-- Russ: Absolutely-- Guest: the idea that the big picture idea shifted. You know, it's a bizarre thing, though, because it's like--I get asked, you write a book like this, you get interviewed about it. As I am talking about this, I feel myself almost hoping or expressing the idea that, 'I hope we're wrong, because my book says we might be.' And I don't know if I feel that way-- Russ: Look how smart you are going to look in 2000 years. One guy-- Guest: [?] one thing right-- Russ: 'There was this one guy, Chuck Klosterman; he was a genius. He understood that thousands of years later...'. Shame on you. Guest: The only thing is--people want predictions. Russ: Yes, they do. Guest: I'm not a big predictor of things, but when you write about the future, that's what they want. They want you to say something like, 'Well, okay, we think it's going to be the Beatles; we think we are going to remember the Beatles. But nope, it's actually going to be Quiet Riot. And here's why.' And that's what they want. Russ: Yep. Guest: That's not really how this book works. |

| 13:13 | Russ: Well, let's take the literature one, because I was totally fascinated by that, as a lover of fiction. You were speculating in that chapter and sections of the book about in 100 years who will be seen as the great writer of this period. And the easy answer is somebody like Philip Roth or David Foster Wallace--somebody who has a reputation among the elites, the academic world, as sort of being a great writer. It probably won't be Stephen King for that reason. It won't be J. K. Rowling. And you said, 'It almost certainly won't be Philip Roth or David Foster Wallace or anyone like those folks that have a great reputation now.' Explain why. Guest: Well, okay. This is the way I would describe it. If you had to pick someone--if I was a gambling person and I was somehow gambling on the perception of the world in a hundred years, those are the people I would pick, as well. They would be the safest pick. However, nothing about the way, sort of, literary history has unspooled really suggests that this is how this works. The apex people tend to be writers who a future generation reinterprets their work to mean something else. You know, that, the greatness they experienced within their lifetime, or sort of the value of their work, it's not that that is false. It's just that what is viewed as great changes--very often with the changing definition of what is transgressive. Because it seems as though as transgressive are, is what when we look back, seems the most important. People who had ideas that seemed to go against the idea of the culture, um, were maybe unsettling at the time-- Russ: They changed things. Guest: [?] Yes. They didn't necessarily change things. They were ahead of the curve that changed what was coming. That the way people thought about, you know, relationships, or the way people thought about what the value of your life is or whatever how you thought about these things. I use Moby Dick as this example-- Russ: example-- Guest: When--I mean, it's kind of the best example. Where, so, Melville writes Moby Dick; and he thinks it's going to be sort of his defining work and his masterpiece. And it gives him extra views. And it doesn't sell that great. And it kind of ruins his life. And it isn't until long after he is dead, after WWI (World War I), that the book is sort of rediscovered: not just as a good book but as The Book. Like this is the Great American Novel. And it essentially has become the template for the idea of the Great American Novel. So the question became what changed, right? Well, you can give specific examples of things that may have changed--guys coming back from WWI, you know, maybe the idea of fighting a faceless enemy somehow resonated with the idea of, you know, this faceless whale, and camaraderie between sailors and the camaraderie between soldiers and the need to know all this obscure information--Moby Dick has chapters on making rope and stuff like that. You go to a war; you learn how to take your rifle apart. All these things. But this is kind of a sense of reverse engineering. Russ: Yeah. Guest: What has happened is the book was, in many ways arbitrarily selected--and not that it's not great--but it's the book that got picked. And there were other great books that could have but didn't. And then we have to sort of explain why. So, what I think of a hundred years from now, kind of using the same logic, what someone's going to do is they are going to take a book out of this period, and its greatness is going to be found in these future people's ability to basically take their life, whatever their life is like, and see fragments of it in this book. So, the downside is somewhat like Philip Roth or David Foster Wallace or John [?] or DeLillo or Pinchon or any of these people have, is, we spend a lot of time arguing and deducing what these books mean. Like, we've had many, many, many public discussions, and so much writing, and so much analysis of what it's these books mean, that it's going to be hard for someone in the future to say, 'Well, actually it was this other thing, that's happening now.' So, the people who actually have the best chance of seeming very important in a hundred years are kind of blank slates--people who have written books that are either generally unread entirely, or are read but not taken seriously. So that, in the future, when these book are rediscovered, the meaning that they have can be kind of invented by these different people. But we can't re-invent what Philip Roth wrote about. Like, there's an understanding of what these books are now. You see what I mean? Russ: Yeah, absolutely. Guest: So, like-- Russ: No, it's a brilliant insight. Guest: There's a weird advantage to being unheralded in your time. Because if you are that sort of becomes the meaning of your work. But if you are unheralded, kind of unknown, it's kind of all things: people who want to care later. |

| 18:28 | Russ: Let's take another example, which I loved. Which--you imagine that there was a television show in ancient Egypt that we come across. It takes a leap of the imagination. You recognize that it probably wasn't much electricity in ancient Egypt and broadcasting was pretty embryonic. But imagine that we found the tapes of that show: What would we do with them? And then you use that to imagine what people in the future will look back on, the age of television, to understand our cultures. Talk about that. Because that was really rather extraordinary. Guest: So the idea that I work with is that obviously, it's impossible, but let's say we found out the Egyptians had television. It makes no sense how this could have worked. But let's say that they did. And we have all the tapes. So, everything that was on television in ancient Egypt, we suddenly possess. Well, what would be interesting to us? Well, it wouldn't be whatever they classified as their best shows. Whatever they--if there was some ancient-- Russ: Blogger. Blogger-- Guest: Yeah. We would be interested in news and sports. Nonfiction programming. And of the fictional material what we'd be looking for is a way to understand what life in Egypt was like, through that show. In other words, we wouldn't care so much what they thought was the most entertaining. We wouldn't be watching for entertainment value. We'd be looking at it like an anthropologist: What allows us to see what the Egyptian world was like? And I tried to imply that [?] the age of television (TV). I assume, just because of the way technology works, that television will probably be like--it's not going to disappear overnight, but I don't think in a hundred years we'll have the same relationship to TV we have now. I think it will be replaced by something else. And TV will sort of be a dead media. We'll have access to all of those shows, digitally and [?]. So when somebody in this future time wants to go back and examine television, what will be interesting to them? Well, I don't think it will be shows like Madmen, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, and all these shows that we consider to be artistic successes. And they are. But what they'll want to see is a way to understand the world almost accidentally. In other words, TV shows that have what I call ancillary verisimilitude. Shows that end up being real not because that was their intention, but it wasn't like the show owner was saying, 'I want to make the realest show possible.' The show owner just thought they were going to make a television show and accidentally created this kind of transparent sense of reality. And that's sort of how I worked through this problem, and sort of came to the conclusion that it might be a show like Roseanne, where it aired during a time when the perception of TV was pretty low. Nobody thought it was art, the way they do now. It wasn't any--we were not in any golden age of television or anything like that. The motive of the show was just to succeed, be a popular network sitcom (situation comedy); but there were all these little details within the program that I don't even think were intentional but give us an actual sense of what a family living in America in the lower middle class during the late 1980s or early 1990s, what that would be like. Now, what does that tell us? Does it tell us Roseanne is a better show than we think? Does it mean--I don't know what it means, in some sense. I just think it's interesting. Russ: Yeah. It's really interesting. I love your point that reality TV would be the last place you'd look, even though you think, 'What could be more real than that?' But of course it's not very real. Guest: Yeah. The word 'reality TV' is the problem. The people going on reality programming now understand what they are doing. They understand that this is not really an attempt to show a documentary of what life is like, but they are supposed to embrace character types--that there are certain kinds of conversations and conflicts they are supposed to have. So what they are really doing is acting without a script. So, of course it seems extra fake. If you are flipping through programs on your remote control, you know immediately when you've slid across some reality television--like the way it looks, the way the people talk. It looks less real than scripted TV. It's funny--I mention, like, MTV [originally standing for Music Television] is the real world, kind of the counterintuitive success of that show is based around its title and how there was immediate recognition that this is the complete opposite of what you are seeing. [?] not seeing the real world. Russ: It should have been called the surreal world. Guest: Yes, but that wouldn't have worked. If they had called it that, it would never have succeeded. |

| 23:42 | Russ: So, let's talk briefly about music. There's a long discussion of it. It's absolutely fascinating. But the part I found really interesting to start with, was this idea--Turning to my audience, I'll ask the question: How many people can you name who wrote marches, the kind of music you'd hear at a parade, at a football game? And you point out is that the answer is 1, and that's John Philip Sousa. And you suggest--it's a little bit of a stretch--that, say, 300 years from now, we think about, say, rock music, that if someone wanted to evoke the last half of the 20th century musically, there is only going to be maybe 1 representative of that kind of music. Guest: What seems to happen is this: Now, when I forward this idea I'm not saying there are no exceptions. There are, of course. But for the most part, everything, whether it's music, film, books, whatever the subject may be, culture seems to operate like this over time. You start with a huge field of potential candidates. There are many people who could be seen as really central to the existence of that art form. And then time plods along. And as time plods along, certain candidates drop by the wayside. They get lost or they disappear, or their relevance changes. And eventually you get down to only one artist remaining. And then, the significance of that artist is kind of amplified and exaggerated. And that person ends up becoming interchangeable with the art form. John Philip Sousa being this example--there were many people creating marches. And now we have a form of music we all vaguely understand--I think even the average 7-year old kid knows when they hear marching music that they are at a parade or they are at a football game or whatever the case may be. But if we go on the street and we ask people, 'Who made marching music? Name marching composers,' 99% will either name nobody or just Sousa. He has become the idea itself. So, you apply that to rock music--it just seems impossible, right? Rock music is so popular for so long--really along with television, probably the biggest cultural influence of the 20th century. There are so many key artists. But the same thing is going to happen--that we are going to move forward and artists are just going to disappear from people's radar. It's already happening now. So, who will be the one person who will end up becoming the epitome of this? In a rational world that answer would be the Beatles. But we don't live in a rational world. It's going to happen for other, more capricious, more arbitrary motives. And I kind of try to work through this chapter, saying, 'Well, how will this work? Why will people disappear, and who might remain and what will be the reasons that they remain for?' Russ: And of course you make a semi-prediction--we can leave it for the excitement of the readers to find it--but the part that makes this interesting, as you mentioned earlier: even though people want predictions, what I found more interesting was how you thought about making a guess or a gamble or a bet on who it might be. You didn't mention Eric Clapton, by the way. He would be in my group of people that might qualify. You mentioned about 5 or 6 that might make. And your point that the Beatles, even though they are incredibly successful and are not just like successful, they are considered artistically successful as well, not just financially successful--makes them a strong possibility, but it very well might not be them and it could be lots of other people. Guest: Here's another kind of possibility. There's another possibility that the Beatles might become more remembered than rock music itself. That, for whatever reason--the way that the music resonates with kids and sort of the way it's built the culture of the last half of the 20th century, the Beatles as characters might be what exists; and rock music is only remembered as the ancillary thing of what the Beatles did. Russ: Yup. Guest: Like, rock music matters because the Beatles did it, not the other way around. There's also, I think, a possibility that the things that we'll remember about rock music won't be individuals: it will just be tropes. It will just be qualities of what we think rock music is supposed to represent--a sense of lawlessness, or something a kind of simple blues-based music. Russ: Rebellion. Guest: Music that--yeah, rebellion--and music that was invented by black people and co-opted or stolen by white people. So then it's just all these just different kind of qualities, which will then be applied to whatever seems to best fit the puzzle. I think the way that history works is just pretty fascinating. Because it's almost as though we knowingly live in a way that contradicts the way we suspect you'll end up being constructed. I don't know--I'm not a historian, but I love thinking about it. Russ: Well, part of it is we don't want to think about that, like you said earlier. It's just too--there's something dissonant about that--that I'll, say, love the Beatles--I don't--but suppose I love the Beatles: 'Well, of course they are going to be the ones.' Just like I want my friends to like the Beatles, I want my great- great- great- great-grandchildren--they'll think the same as I do. So there's a desire, which Adam Smith mentions--we'll get a little economics in here directly--that we want people to like what we like, and dislike what we dislike. So if I tell you that Abba is an awful music group, it would jar me if you thought they were great. So the same thing, I think, is true down through the generations. |

| 29:34 | Russ: But I have a puzzle for you, which you don't mention in the book, which is the following. And by the way, for listeners who are thinking, 'Oh, come on. You are telling me the Rolling Stones won't be remembered? The Doors? The Who? Van Morrison? Elvis Presley? Come on. They are all going to be remembered,' the answer is, 'Yeah; who is remembered before 1950? Who captures--what artists can you think of who were important between 1900 and 1950?' I happen to like that era a lot. I can name a bunch. But I think most people can name one. And that was-- Guest: You already can--this is already visible when you start talking to any person, really under the age of 50, about jazz. Russ: Yup. I mean, jazz was a real important thing in the history of the United States. You look at Ken Burns' documentary and all these things--it was incredibly central to the black experience; all these things. And the number of famous jazz musicians now, it might be-- Russ: Three? Guest: It might be down to 10. Russ: Yeah, it's a handful. Guest: I mean, yeah, I mean 3 I guess are real famous. But finding someone who can name 10 jazz musicians, that's possible. Finding somebody who can name 25, you are probably talking to somebody who-- Russ: A scholar. Guest: A scholar or a big, like a real invested fan. Like somebody who-- Russ: A jazz fan. But before 1950, in the non-jazz world, it's Frank Sinatra. Then it's nobody else. I happen to love Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan; and I like Tony Bennett, and I like Billy Eckstine, but outside of people who really care, it's 1. So, anyway, here's the puzzle, though. In the literary reputation discussion you say it's going to be somebody we've never heard of. Probably--not necessarily but probably--who can be reinterpreted. Why is it that in the music debate of 300 years from now you think it will be somebody who was extremely famous and successful, just not necessarily the one that we would think of now? Guest: Well, that's a good question. Part of it has to do with the inherent tie that popular music, and particularly rock music, has to youth culture, in that it's--you know, books have sort of existed, or what we sort of use in a loose way in describing a book, you know, really since the dawn of complicating thought--in that books aren't expected sort of to--the success of a book is not dependent on its having an impact on the world at large. And popular music, it's very, very difficult to be an important musician with no audience. You look at something like, okay, a record like, Trout Mask Replica or something, some of these records from the 1970s that critics know about but no one bought, who still have not, you know--like it's, or Frank Zappa, or something like this. Russ: That's a good example. Guest: I suppose it is possible that, you know, over time those things could emerge and become sort of the standard for what rock music was. But also, if that were to happen, it would suggest something about rock music that would be kind of profoundly untrue--which was that it was fundamentally an experimental art form. You know, if Trout Mask Replica is the example, or if Frank Zappa is the example of what rock music supposedly was, it would be beyond rock. I mean, you talk about maybe we're wrong: that would be like maybe the wrongest way to think about what rock was. Literature is not really like that as much. The thing I say about books is, it seems very plausible--there are kind of like three easy kinds of candidates: People who that we expect to be great. There's people we don't know at all. And then there's a third category of people who we know of but don't take that seriously. Actually, the Herman Melvilles of now. Herman Melville was a commercially successful writer. He made a living doing it. He just wasn't seen as being transcendent. That class actually might be best positioned for this. Because their books will have been popular enough and proliferant enough and in libraries enough that people will be able to find them. But, the idea of them having a very clear meaning or what their importance is, that will be kind of still up for debate. Russ: Well, I just want to take the opportunity to say "Peaches en Regalia," which I don't get to say very often on this program, for you Zappa fans out there--I don't think those 3 words have ever been said in a row-- Guest: Have you seen the new Frank Zappa documentary? Russ: No. Guest: Oh, I just saw it a couple of weeks ago. Russ: Is it good? Guest: Just a collection of his interviews, basically, with some of his music. I find his music very difficult to listen to. So that complicates the experience of watching the documentary. Russ: "Peaches en Regalia" is pretty good. If I've got the title right. I hope it's right. But the other point I thought I had, talking about these differences, is that: What is still talked about in literature, it's extremely ephemeral--people whose reputation was, somewhat like Somerset Maugham, who was incredibly well regarded when he was alive, and I think is probably less so now. Or Hemingway, who was a giant in his lifetime and I think now--I'm not sure if people are going to read him in 100 years except in English classes, maybe. A lot of that reputation comes from the academy. I feel like it comes less from the academy in the music world. It comes more from something else--the culture writ large. Is that true? Guest: Well, I mean, yes, there's less of an academy, for one thing. Although, I will also say that is changing. The idea of music criticism has become, particularly in the last 15 years, 10 years, more of an academic pursuit-- Russ: More scholarly. Yeah. It's true. Guest: Yeah. But, certainly from like, you know--it's kind of weird to think about this. So, the first album, that was, rock record, that was really taken seriously by like the mainstream media was Sgt. Pepper. Okay? So it's 1967. And yet what we view now as the most important phase of rock in many ways is basically like 1955-1965, 1966. So this incredibly important period, it's importance comes from what? You're right--it's not like there's some academic source telling us this. It kind of happened naturally. Which is also part of the way, part of the reason why artists from that period will always be seen as sort of the most important-- Russ: foundational-- Guest: creators of this art form. It's like, we talk about Presidents, or whatever, you know. The list of the great Presidents is constantly shuffled. Every year we go through this. When I was in college, Grant was the worst President. Now it's Buchanan. You know, it's like FDR (Franklin Delano Roosevelt) seems to be creeping up the list higher and higher. Lyndon Johnson used to be sort of in the middle of the pack; now he's higher. However, the very top of the Presidential list is always going to be Washington and Lincoln and Jefferson--the people that have been at the top forever--because they sort of create the definition of what a good President is like. Like, a good President now is somebody who seems to embody and represent what Washington and Lincoln did. It's the same way in rock music. There can't really be a rock band greater than the Beatles, because they essentially invented how we believe rock bands-- Russ: the idea of the rock band-- Guest: how they are supposed to interact. Like, everything else--what's good about the Beatles' music is what's good about rock music now, in a lot of ways. So, there are some things that are hard to change simply because they create the definition. |

| 38:15 | Russ: So, I want to shift gears, and I want to move to sports. Which, you have some very provocative things to say. You start off by making, I think, a very deep point: that a lot of people have predicted that national football is going to die. It's too violent. Players are apparently being harmed physically and very possibly deeply disturbing ways through their cognitive abilities being degraded by concussions. And the NFL (National Football League) has responded; they've tried to make the game a little bit safer. It's not clear whether it's going to make it. And the standard view, by many, is that, well, over time, people aren't going to want their kids playing football. You hear former football players, stars, saying, 'My kid's going to be a baseball player. A soccer player. I'm not going to let him play football. I don't want that to happen to them. I want him to be able to walk, and think.' Etc., etc. And so a lot of people think football is going to die off. And you make the great observation that it actually might thrive a lot more by becoming more violent. Explain. Guest: Yeah. Well, right now there seems to be like two baseline perspectives on the future of football. One is, as you said: The game is doomed. The other, that it's too big to fail. It's too central to our culture now; it's too central to American life, so they'll just tweak the game and they'll adjust the game, and [?], the level of violence is brought down to an acceptable level. But I sort of see two other possibilities. Because, you know, we might be wrong about these two things that seem sensible. One is that, I can imagine football becoming significantly less popular but socially more important, because it will come to represent a certain kind of ideology that for the most part has been removed from the way we think about life. I mean, you know, it's--the idea of physicality in life, which was a real central part for most Americans through really the 1950s-- Russ: Most of human history-- Guest: Yes. Exactly. And now that's kind of been taken away. But it still exists in football. So--it also seems like a lot of the ideas that would come to be viewed as unenlightened and troubling--the idea that, oh, the ability to intimidate someone is a value. Or that masculinity is prioritized in any sense. Or that you can yell at someone in order to get results. All of these things-- Russ: I'd add suffering--the idea that you have to be punished physically to be, to go through a crucible that changes you and makes you a better player or better person. Guest: Yes. And also, that the rules governing these games are extremely strict and kind of inflexible, and don't really seem to be impacted by the changes in society. These things--in most of society, we're trying to remove those ideas. So, there's this one place where it still exists and where it still flourishes. And I can imagine people--that it might become a political idea. Like, for example, the Republican National Convention is happening right now. I can easily imagine if a convention like that were happening at a time when people were trying to say, 'Ban high school football in the state of Ohio.' Or, 'Ban high school football in Alabama,' or something. Or, they would be like, 'We are against this: this is part of the problem.' This idea that, you know--and even if football maybe loses 2/3rds of its audience, the third still watching it would care about it in a much deeper way, and then would actually become more popular. The violence of the game is what would save it, because there's no other place for that to exist in society. Russ: Yeah. It's an incredibly deep point. And it reminded me of my childhood. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. My father was raised in the South. I was born in the South. Both my parents grew up there. My dad found himself in Lexington, kind of a fish out of water. And, frisbee became very popular. And my dad didn't like frisbee. And I couldn't understand why he didn't like it. Guest: Like, Ultimate Frisbee? Russ: No. It took a while for Ultimate Frisbee to be invented. This is just tossing a frisbee. Because he viewed it as an anti-sport. He viewed it as anti-competitive. I thought he was crazy. But he wasn't crazy. Like many things, I thought he was wrong. But he wasn't. He had an insight there. He might not have been right about frisbee, but he was right that it was in some sense a statement. Parents wanted their kids in Lexington to play frisbee because it was not competitive. It was not physical. There was not a two-a-day, four-hour intense workouts without water to transform your soul and make you a great frisbee player, as there was with, say, football. And-- Guest: That [?] still exists right now with soccer. Russ: Of course. Guest: There is a meaning to being a soccer proponent. It means that you are more of a global thinker, and that the kind of, the reactionary sense that football represents, like, you are against that. The cities where soccer tends to be embraced tend to have a political ideology that aligns with that-- Russ: A different sensibility. And even Ultimate Frisbee--which is competitive, right?--there is no contact. It's a very different kind of sport. And one way to say it, which you don't say in the book, but you alluded to a minute ago, is it's not as physical; and it's not as masculine in the traditional definition. Because that word is dying. That whole idea that there's anything virtuous about masculinity--whether it's the physicality or other parts of it--our culture is rejecting that relentlessly. Which means, as you point out, I think correctly, that things that still accept it or embrace it--football being the most, one of the most dramatic examples, but football being the most--might become a bastion for contrarians as a way to express themselves. And I just think that's a really interesting idea. Guest: Yeah. I think that's very true, exactly what you said. Yeah. |

| 45:03 |

Russ: Let's go to Koko. Not the drink, but the animal. You were "The Ethicist" at the New York Times Sunday Magazine for 3 years--which is in itself a fascinating thing. Talk about Koko and animals versus people. Guest: Yeah. I get this letter when I was at "The Ethicist." For those who don't know what this is, it was like the column in the New York Times Magazine where I--I always hated when people made this comparison--it was a little bit like "Dear Abby" or Ann Landers, except people were writing in problems that were ethically based. And I was supposed to sort of deduce what's the most ethical conclusion to this problem. And somebody asked a question that, on the surface seemed really kind of preposterous: It was that after Robin Williams committed suicide, they went to this gorilla, Koko the gorilla who I believe is at the Cincinnati Zoo--she speaks in sign language, seemingly intelligent gorilla. Russ: At some level. Yeah. Speaks in sign language at some level. Whatever that means--we don't really know. Guest: Has a relationship with their owners that somehow seems--I guess not owners but keepers--that seems to transcend the normal human/animal relationship. And they tell Koko, who had met Robin Williams many years ago--Robin Williams had come to the zoo and they had interacted and had a great time--they tell this gorilla that, 'Hey, that guy you met 11 years ago or whatever, Robin Williams, has died. He committed suicide.' And Koko cried--he was very depressed. Now, the person who asked him the question to "The Ethicist" was like 'What's the point of telling a gorilla this? You are only going to upset it. Isn't it unethical to tell a gorilla something that you know will make it sad, or whatever?' Now, that question is sort of interesting. But the larger question is this idea, is like: Is this even possible? Is it possible that this gorilla could somehow have an emotional response to the news that a celebrity actor has committed suicide? Because, if it did, it would mean many things. It would mean that gorillas, apes, sort of have a recall for every person or thing they encounter. Would it mean that Koko would have somehow sensed something about Robin Williams, that she knew he was a different kind of individual even though she'd have no sense of celebrity? Do gorillas know they are going to die? Do they know what death is? All of these things. And, while I was answering this question, which I just found kind of fun and just really sort of compelling, I talked to a, kind of a specialist, a veterinary specialist, about this. And his response was, 'An ape has the cognitive ability of, say, a 3-year-old or a 4-year-old. But that's not what you need to think about. What you need to think about is the fact that animals might have a greater emotional intelligence than humans do.' And his argument is that we're constantly learning that animals do seem to have a greater sense of emotional intelligence than people. Now, emotional intelligence, in general-- Russ: It seems like a stretch. But it's possible. Guest: It could be. Here's the deal: In the 1980s--we were having this conversation in the 1980s--the whole idea of emotional intelligence we probably kind of scoff at. That was something you might see in Cosmopolitan Magazine, the idea that somehow there was intelligence to your emotions in the same way that there was an intelligence scholastically. Well, that's not the case any more. Now, everyone kind of agrees that emotional intelligence is the real thing. Russ: Yeah, but they could be wrong, Chuck. Guest: [?] What? Russ: They could be wrong about it, too. But go ahead. Guest: They could be. But I'm saying that we have now come to sort of generally take the idea of emotional intelligence much more seriously than we used to. Well, let's say this keeps going. Let's say that in 50 years, it's not just that we just recognize that emotional intelligence exists, but we actually see it as more important than scholastic intelligence. And that an understanding of empathy and all of these things, they are actually the most meaningful way to understand how smart someone is. And at the same time, this idea that animals have greater emotional intelligence than us becomes more and more verifiable. So, we believe emotional intelligence is important. And we agree that animals have more of it than we do. Well, that would really paint a strange portrait of society. Because obviously humans dominate society. It's not like we're going to turn it over to the animals. We're not going to be like, 'We're going to elect a cat President' or whatever. We'd have this strange situation where we would have to concede that animals are both our slaves and more intelligent than us. Russ: It's really interesting to think about. We'd almost certainly stop eating them. And we may stop eating them anyway. But that part would be just the beginning, as you say. We'd be--kind of up-ended in many ways. And the part that ties into this, that I think is important as well, is that human intelligence may turn out to be seen as less and less relevant as artificial intelligence grows. And so, many people have argued--I'm sympathetic to the idea--that empathy will be a much more valuable skill in 25 years than it is now. That to be human, to be non-intellectual part of our humanity, our heart rather than our mind is going to be valued much more than it is relative to the mind--our heart will be. And that does raise the possibility that animals that are, say, loyal--like, just thinking about a dog--I'm ashamed to say: I kind of look down on, because he's always glad to see me regardless of what else has happened in the day or how I've treated him. I don't actually have a dog. It's hypothetical. But that idea that somehow dogs are--that's a pleasant trait for dog owners, but what if it came to be seen as not just a pleasant trait but so much more important, as you say, than our ability to do calculus--because we're not going to need that? Machines are going to do all the calculating. Or math. It's kind of wild. Guest: [?] I mention this in the book, sort of the idea of rote memorization, because I talk about Bob Dylan and how there's, in Bob Dylan's autobiography at one point he kind of makes a passing reference to the fact that the reason he likes to record songs that have 16 verses or whatever is like, he's like, 'Well, there's just something enriching about memorizing things.' Of course, he was born in like 1946 or whatever, whenever he was born. So he was raised during a time when rote memorization was still a big part of school. Now, I went to school in the 1970s and 1980s. By the time I got there, rote memorization had been profoundly reduced. I had to memorize like the Preamble --for the most part it wasn't a thing any more. Now I think there's almost none of it. Like, the idea of kids memorizing anything is seen as almost superfluous-- Russ: Anti-intellectual, actually. Guest: Yes. You know, so, but that changes sort of what the meaning of what intelligence is. I grew up to believe--and I'm not saying this belief is right, but it was like: Intelligence meant you knew about things that you didn't have necessarily first-hand experience of. Like, anybody can read the paper and know what's going on right now. A smart person knew about what happened before they were born. A smart person knew about films that they hadn't yet seen because they predated them and they went back and saw them. If you really liked sports, it wasn't enough to know who was good now: you had to know about Jim Brown and Wilt Chamberlain and all these people. That seems to--we've moved away from that, it seems like. That there's now almost this belief that all of that kind of information has been kind of curated and is built into our computer. We don't need to know these things any more. It's a waste of time to know things that aren't right in front of you. You can always go back and find them. That changes what it means to be smart, to me, in a way that I don't know how comfortable I'm with. Not because I can really argue that my way was better. I just don't know if I like the different way it is now. Russ: It little profits that an idle king,I think I got that right. [Almost perfect: last line as written by Tennyson was "That hoard, and sleep, and feed..."--Econlib Ed.] That's the opening of the poem "Ulysses," by Alfred Lord Tennyson, that Miss Kineen made me memorize in the 8th grade. And I can go on. I don't remember the whole thing, but I can do the ending, which I get goose bumps every time I say it--and I'm not going to do that. But it's an interesting question as to whether rote memorization of certain things is a bad thing. I love what I have memorized. I love that it's-- Guest: Yeah, but the thing you just did now: Now it's just kind of a bar trick. Russ: Yeah, it is. Guest: Somebody would say, like, okay, what's the utility of that? And it's a hard thing to answer. It's hard to say why memorizing something, what utility that has. But, I don't know--I remember in high school, we learned algebra--of course you would say, like, 'Why do I need to know this?' And the argument was very often, 'Well you don't need to know specifically this. You need to know how to think.' Like, this, like algebra helped you how to think and how to sort of understand ideas that aren't visually clear or visually obvious. It's like: Was that true? I guess I probably argued against it at the time. Now, as I'm older, it seems [?] that's how it always is. |

| 55:22 | Russ: But I think that misses something else. Which is that if I have a desire to know what the opening of the poem "Ulysses" is, I don't need to have memorized it so I can find it right away. The virtue of the memorizing isn't, 'Oh, I helped put some grooves down in my brain. The virtue is, is that the poem, "Ulysses," the idea of heroism, the idea of an old warrior near death--which is what that poem is about, reminiscing about his youth and trying to stave off death, and reviewing his life--that concept is so much more salient to me because I've memorized it. Not just because I've heard of it. And I think to tap into that is that value. And I think one of the reasons that music is so powerful in our lives, pop music, is because rhyme and music help us memorize things. We're much more likely to memorize the lyrics of songs now than a poem--for obvious reasons--and certainly than a passage in a book. And, so it's more relevant to our lives, in a lot of ways--I think just for that reason. Guest: I mean, it could be, at the same time, I mean, you gave, you opened that poem, you described it, you memorize, you told me what you remembered, you know. And it kind of went over [?]. And then you described what it was later. Was the second description more helpful? I don't know. I mean. For you it wasn't. For me it was. But my understanding of this is shallow. Your understanding is deeper. I think that there probably is a depth to memorization that is hard to quantify. But-- Russ: Yeah. It's an interesting question. |

| 57:04 | Russ: Well, we're almost out of time. And there are a lot of other things I wanted to talk about--which is a shame, but such is life at EconTalk. I want to close with a question you raised at the end of the book, which is whether this matters at all. There are a lot of wacky ideas in the book, much even perhaps wackier than that animals are smarter than we are in the emotional sense and that that will turn out to be decisive. You speculate on whether we are in the middle of a simulation and we are not really living reality the way we think we are; that there are multiple universes; that the Constitution could turn out to be a mistake. So, you speculate that many of our deeply held beliefs might turn out to be wrong. And then you raise the question--having talked about all those things, and all the ones we've talked about, with great zest and style, you say: Does this matter? Who cares if we're right about gravity? For example, you speculate about, 'Maybe gravity will be different, the way we think about gravity.' Gravity is not going to be different, but the way we think about gravity in 500 years might be really different than how we think about it now, or maybe we'll--who is considered a great writer is going to change a lot. One response to this entire book--which you confront--is: 'Well, yeah. Who cares?' It's not going to change anything. So what if plate tectonics are real? So what if Philip Roth is going to be forgotten and the Beatles aren't going to make it in 500 years? What difference does it make? Guest: Yeah. You know, I was on this book tour. The last event was in Portland, and after the event one person said exactly that. They came up after the talk, and they were like, 'Yeah, I really enjoyed the talk but I do have one question'-- Russ: An awkward question. Guest: Yeah. Well, it's like who cares if this is true. They basically were asking: Why did you need to write this book? And, you know, my answer to that--probably unsatisfying to them, maybe unsatisfying people listening to this podcast. But like, to me, if something is interesting and entertaining, that's enough. Like, I don't need to feel as though every extension of my creative life has a real, practical purpose. I probably wouldn't have pursued writing if that were the case. I would have done something different. Russ: Hear, hear. Guest: My--the way I view it is this: Like, it's amazing that we're alive. And the experience of life is crazy. It's crazy that it's happened. It's crazy that it's happened, all this--I just think the world is an amazing thing. So, it's like, to me, the most fundamental question that I can ask is: What does it mean to be alive? Is this really happening? All these things I'm having, these thoughts I'm having--why am I having them? So I pursue what's interesting to me. I don't say to myself: I've got to find something that will change the world or that is necessary or that is critical. I'm just not like that. Like, I'm not mad and not criticizing people who view the world to that length [?]? I don't. I just think to myself, it's like, 'Boy--my whole life I've been unconsciously wondering if what we know about the world is right or if it's all an illusion. Maybe I never had the language to describe it or to explain to other people. But now I'm 44; now I do. Now I sort of understand the question I've been unconsciously been asking myself. And I'm going to take this ball of yarn in my mind and straighten out the strands. And that to me is what writing is. So, maybe we are wrong about the world; and maybe it doesn't matter if we're wrong. That's not my concern. I'm just trying to bring up the idea that this is a real possibility, and that we shouldn't live life just saying to ourselves, 'Well, that's how it is.' That doesn't matter, either.' Like, I don't know. I, I don't know if that's a real cogent answer. But that's how I feel. It's like, to me, whether or not this matters is secondary. Russ: Well, as a reader who spent a few hours enjoying every page, which doesn't happen very often, you certainly changed those hours for me and made me think about a lot of things. In the book you mentioned 'wonder,' and I think your book has a lot of wonder and I think appreciating the wondrousness of reality. And the puzzle of it is very much worthwhile. |

Even the Dolphins at Sea World Want You to Stop Taking Pictures With Your iPad

Husky Imitates Baby Trying to Speak in This Precious Video

What a Name For Restaurant

AkasicBlast from the past: this restaurant is on the street I used to live on in London. Delicious stuff.

Son Secretly Replaced Photos in the House With Steve Buscemi and Mom Has Yet to Notice

The Internet is rooting for Twitter user @Claremaura and her brother after Clare revealed her brother's master plan to eventually replace every single photo in the house with Steve Buscemi.

Here's a look at his progress so far:

Submitted by:

Review: Descendents, 'Hypercaffium Spazzinate'

Undimmed by the decades, singer Milo Aukerman and his band thrash, crash and blaze gloriously on the seventh album in their 39-year history together.

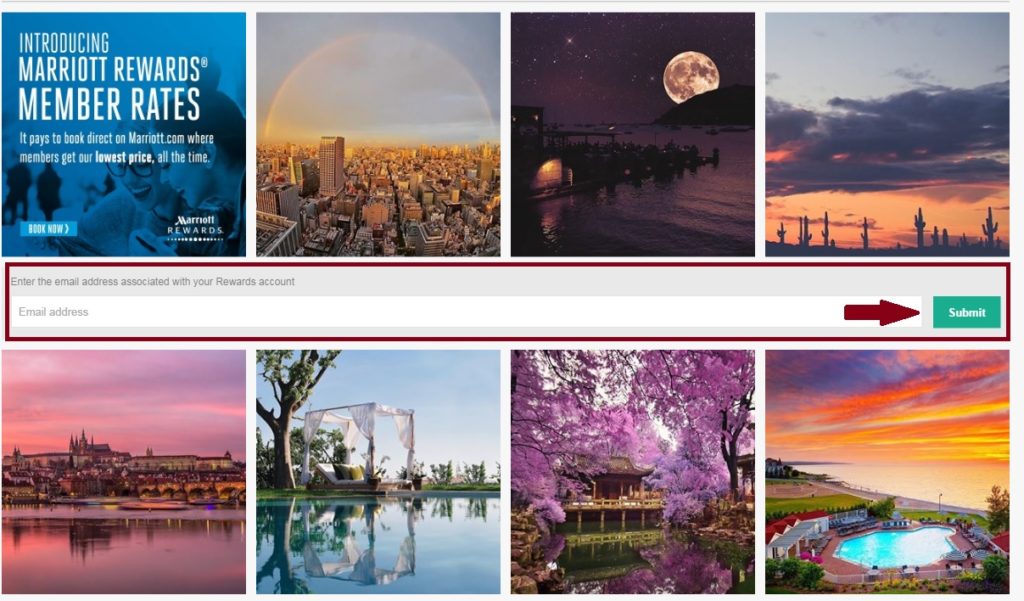

500 Free and Easy Marriott Points

Marriott will give you 500 points for following them on Instagram by June 21.

Once you follow Marriott Rewards on Instagram, go to this link and enter the email address associated with your Marriott Rewards account. It took me a few minutes to realize where on the page you do this:

Continue reading 500 Free and Easy Marriott Points...

Comments

- thank you as always for the tip! by steven k

- […] (Thanks to View from the Wing) […] by 500 free Marriott points in 20 seconds - Points with a Crew

Related Stories

Hayek's "The Use of Knowledge in Society" - A Summary

Steve Horwitz

I have been thinking a lot about the misunderstandings of Hayek's "The Use of Knowledge in Society" essay. Below I offer what I think is a quick summary of his argument that stresses both the importance of private property and the price system as jointly necessary for economic coordiation.

1. Knowledge IS decentralized in that each of us has our own personal knowledge of time and place (and that is often tacit).

2. Therefore, planning and control over resources SHOULD BE decentralized so that people can take advantage of those forms of knowledge.

3. HOWEVER, decentralization of control over resources (what Hayek calls "several property") is necessary BUT NOT SUFFICIENT for social coordination.

4. Effective decentralized planning also requires that people have access, in some form, to the bits of knowledge that other people have so that they can form better plans and have better feedback as to the success and failure of those plans.

5. Providing that knowledge is the primary function of the price system. Prices serve as knowledge surrogates to enable people's individual knowledge and "fields of vision" to sufficiently overlap so that our plans get COORDINATED.

6. In other words: decentralized control over resources is NECESSARY BUT NOT SUFFICIENT for a functioning economy. Such decentralization requires some process that actually ensures that separately made decisions are, to a signifcant degree, based on as much knowledge as possible so that economic coordination can be achieved. That is what the price system enables us to do. [EDIT: and the prices in question are not, and need not be, equilibrium prices.]

Decentralized decision making without a price system will produce very little coordination and prosperity. Centralized decision making will render a price system useless for economic coordination.

The fact of decentralized knowledge requires that an economy capable of producing increased prosperity for all has both decentralized decision-making (private/several property) and a price system to coordinate those decisions.

Construct the Ultimate Dating Profile by Using Google Autocomplete

Brooklyn, thanks to everyone who came out and sang along last...

AkasicSpot the AK:

Brooklyn, thanks to everyone who came out and sang along last night to celebrate our album release at Warsaw! More photos here.

Photos by Brendan Walter