Shared posts

Take *that*, assholes

She seems really free of hives and overall like a nice girl—nay, woman.

Let's just be honest with ourselves: of course people gossip about us [...] This month's One Big Question is what do you want people to say about you after you've left the room, because it's a way for our deepest insecurities to mingle with our private aspirations and come up with something honest and hopeful, and quite possibly, true.

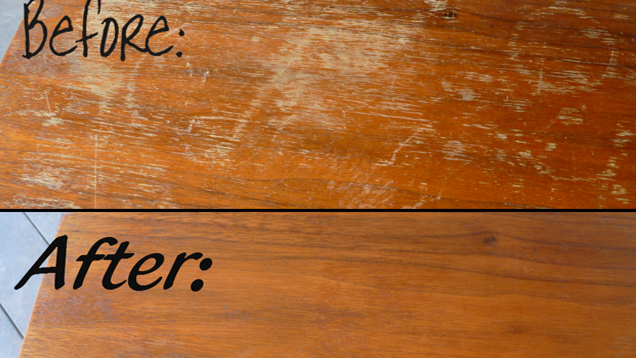

Fix Scratches in Wood Furniture with Olive Oil and Vinegar

Someone used an old email to register a web site account. Next steps?

The emails appear to come from a legitimate multinational company with a hefty Wikipedia page and concerns some kind of application submitted using an old email address that was forwarded to my main account. The email also states that it may take a few days to verify the application and seems to be of a wholesaler/retailer nature.

Is this just an routine phishing thing? A scam? Should I go and change the password/cancel application since I have the password? Ignore it? Report it using the Gmail report tools?

If it matters, the email address could possibly be someone's name, so it might be that old google mix-up that pops up here occasionally. Also, I have not been compromised by any known hack, either online or like the Target hack.

(I'm not sure if it's a good idea to name the company, but it sells a legal product that you inhale that is not pot.)

Rachel Dolezal’s support in Spokane slipping

More bad news for Rachel Dolezal: While the national NAACP expressed support for her last week, she's losing backers in Spokane, Washington, where she leads the civil rights' organization's local chapter.

In interviews with the Spokane newspaper, The Spokesman-Review, or in emails obtained by the paper, several Spokane civil rights leaders and NAACP members expressed their concerns.

Freda Gandy, executive director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Family Outreach Center in Spokane, said Sunday she is angry the NAACP is backing Dolezal, whose actions she said are inexcusable.

“Ethically, I don’t really know how they can say she can be an effective leader when she has lied to an entire community,” Gandy said in an interview with The Spokesman-Review.

Is being Hispanic a matter of race, ethnicity or both?

What to Write About When You Journal

The Right Dose of Exercise for a Longer Life

Will my kids stop getting sick all the time if I move south?

My location is listed in my profile. It does indeed have overall high rates of asthma, though I don't think we fall into any of the specific risk factors, and we don't live in a city neighborhood (we're in a suburb) so I haven't been able to identify prevalence rates for our zip code. The baby is seeing an allergist soon and we may have to get a pulmonologist too depending on how things go.

So... would the kids be healthier if we moved to warmer climes? (Let's ignore for the moment the job concerns, our good access to transit, our location near a high quality children's hospital, good schools, and a host of other considerations.) If not (or even if so) what are some things we should be doing at home to try and keep their lungs under control?

The financial consequences of saying ‘Black,’ vs. ‘African American’

Joe Pinsker in The Atlantic:

One hundred years ago, “Colored” was the typical way of referring to Americans of African descent. Twenty years later, in the time of W.E.B. Du Bois, it was purposefully dropped to make way for “Negro.” By the late 1960s, that term was overtaken by “Black.” And then, at a press conference in a Hyatt hotel in Chicago in 1988, Jesse Jackson declared that “African American” was the term to embrace; that one was chosen because it echoed the labels of groups, such as “Italian Americans” and “Irish Americans,” that had already been freed of widespread discrimination.

A century’s worth of calculated name changes are a testament to the fact that naming any group is a politically freighted exercise. A 2001 study catalogued all the ways in which the term “Black” carried connotations that were more negative than those of “African American.” This is troubling on the level of an individual’s decision making, and these labels are also institutionalized: Only last month, the US Army finally stopped permitting use of the term “Negro” in its official documents, and the American Psychological Association currently says “African American” and “Black” can be used interchangeably in academic writing.

Obedience, Authority, and Domination

“Because I said so!”

I’m sure that many of us have either uttered these words or have heard them spoken to us. We hear this phrase expressed in a host of relationships: parent-child, teacher-student, supervisor-employee, and police officer-citizen. Saying this to someone is generally used to get them to obey your authority and do what you are telling them to do with as little resistance as possible.

When we think about obedience to authority, we often think of the famous study by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. Most students have probably learned about the Milgram Experiment where participants were told to administer shocks to people on the other side of a partition. Despite hearing the pleas and cries of anguish from the person on the other side (who, of course, was an actor), the subjects still administered what they thought were electric shocks. In fact, 65% of the participants administered the maximum voltage regardless of the torment they assumed they were inflicting.

Milgram devised this experiment to try to understand how millions of Germans during World War II could support the Nazis and contribute to the Holocaust. Were these people “just following orders” because “someone said so” or was there something deeper at work? In analyzing the results of his work, Milgram made the following observations:

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

Milgram’s work on obedience and authority was groundbreaking, and his research left a lasting legacy in the field of psychology regarding why people follow orders. However, about fifty years before the Milgram Experiment, sociologist Max Weber offered a similar observation in his attempt to understand why people obey authority. In one of the most important texts of sociological theory, Economy and Society, Weber made the following point:

Every genuine form of domination implies a minimum of voluntary compliance, that is, an interest (based on ulterior motives or genuine acceptance) in obedience.

Much like Milgram, Weber focused on the agency of individuals (their capability to act) and the resources (or lack thereof) at their disposal that contributed to them following orders. For Weber, some people might comply because they are just habitually following orders; for others, they may be more calculating and elect to follow orders in order to achieve some gain. In either case, according to Weber, some degree of human decision making is involved.

Weber elaborated on these ideas of authority, legitimacy, and obedience in a lecture he delivered at Munich University which was published as the essay, “Politics as a Vocation.” Here, Weber outlines three types of authority or domination that may contribute to why people follow orders:

1. Traditional. Weber refers to this as the authority of the “eternal yesterday” which basically means we follow orders and conform to the norms because of the established beliefs of our culture and social group. Accepting an arranged marriage, restricting your diet during a religious holiday, or believing that the male should be the breadwinner and the female the homemaker are examples of traditional authority.

2. Rational-legal. Based on the law and legal precedents, this form of authority emphasizes our “statutory obligations”; in other words, we follow the law of the land—be it the Constitution or other forms of local, state, or federal legislation. Stopping at red lights, paying taxes, and not stealing are examples of rational-legal authority.

3. Charismatic. In this case, authority is obeyed due to the “gift of grace” of the person giving orders. Some people have the type of personality or presence that makes others flock to and follow them. Emulating the actions of the cool kid in your peer group, following the words and advice of a religious leader, or believing the theories and ideologies of a political zealot are examples of charismatic authority.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

We all follow orders in our everyday lives and it’s an interesting sociological exercise to consider why we do so. What are our motivations for doing something that others tell us to do? Why might we follow directions even if we are not comfortable with what’s being asked of us? Why would we obey these dictates even if we know that the directions are morally wrong, ethically suspect, or even outright illegal?

Can you think of an example where you followed the directions of someone but you were not 100% comfortable doing so? Why did you do this? Can you identify the thought process you went through in coming to this decision? Where you influenced by traditional, rational-legal, or charismatic authority? Was it a combination of these? Do you think there were other factors besides these three dimensions that contributed to your decision? What about when you give directions to someone. Why do you expect them to follow you? Why, in the words of Weber, should they “voluntarily comply” with your dictates?

These are great questions to think about not only because they help us understand the subtle, yet complex, processes of social life. In addition, these questions illustrate how seemingly ancient and abstract sociological theories are relevant and even readily apparent in our everyday lives.

Dick and Liz Cheney Are Trying to Be Nice Now

Former Vice President and all-the-time warmonger Dick Cheney has been busy lately, writing insane Wall Street Journal op-eds and appearing on Fox News with his (failed senate candidate) daughter, Liz. According to Politico, this new spree of activity is just Dick and Liz being friendly.

How Traditional Parenting Is Harming Children ... And Benefiting Conservative Ideology

From The Myth of the Spoiled Child: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom About Children and Parenting by Alfie Kohn. Reprinted courtesy of Da Capo Lifelong Books.

When you hear someone insist, “Children need more than intelligence to succeed,” the traits they’re encouraged to acquire, as I’ve mentioned, are more likely to include self-discipline than empathy. But let’s pause to consider the significance of thinking about any list of individual qualities—the attributes a particular child possesses (or lacks). When we encounter a behavior we don’t like, we assume the child needs to develop certain characteristics like grit or self-control. The implication is that it’s the kid who needs to be fixed.

But what if it turned out that persistence or an inclination to delay gratification was mostly predicted by the situations in which people find themselves and the nature of the tasks they’re asked to perform? That possibility is consistent with Walter Mischel’s theory of personality. Indeed, it matches what he discovered about waiting for an extra marshmallow: Whether children did so was largely determined by the way the experiment was conducted. What we should be talking about, he and his colleagues emphasized, is not

the ability to defer immediate gratification. This ability has been viewed as an enduring trait of “ego strength” on which individuals differed stably and consistently in many situations. In fact, as the present data indicate, under appropriate . . . conditions, virtually all subjects, even young children, could manage to delay for lengthy time periods.

Similarly, other experts have argued that it may make more sense to think of self-control in general as “a situational concept, not an individual trait” in light of the fact that any individual “will display different degrees of self-control in different situations.”

This critical shift in thinking fits perfectly with a large body of evidence from the field of social psychology that shows how we act and who we are reflect the circumstances in which we find ourselves. The most famous social psych studies are variations on this theme: Set up ordinary children in an extended team competition at summer camp, and you’ll elicit unprecedented levels of hostility, even if the kids had never seemed particularly aggressive. Randomly assign adults—chosen for their psychological normality—to the role of inmate or guard in a mock prison, and they will start to become their roles, to frightening effect. Make slight changes to an academic environment and a significant number of students will cheat—or, under other conditions, will refrain from doing so. (Cheating “is as much a function of the particular situation in which [the student] is placed as it is of his . . . general ideas and ideals.”)

The notion that each of us isn’t entirely the master of his own fate can be awfully hard to accept. It’s quite common to attribute to an individual’s personality or character what is actually a function of the social environment—so common, in fact, that psychologists have dubbed this the Fundamental Attribution Error. It’s a bias that may be particularly prevalent in our society, where individualism is both a descriptive reality and a cherished ideal. We Americans stubbornly resist the possibility that what we do is profoundly shaped by policies, norms, systems, and other structural realities. We prefer to believe that people who commit crimes are morally deficient, that the have-nots in our midst are lazy (or at least insufficiently resourceful), that overweight people simply lack the willpower to stop eating, and so on. If only all those folks would just exercise a little personal responsibility, a bit more self-control!

The Fundamental Attribution Error is painfully pervasive when the conversation turns to academic failure. Driving Duckworth and Seligman’s study of student performance was their belief that underachievement isn’t explained by structural factors—social, economic, or even educational. Rather, they insisted, it should be attributed to the students themselves, and specifically to their “failure to exercise self-discipline.” The entire conceptual edifice of grit is constructed on that individualistic premise, one that remains popular for ideological reasons even though it’s been repeatedly debunked by research.

When students are tripped up by challenges, they may respond by tuning out, acting out, or dropping out. Often, however, they do so not because of a defect in their makeup (lack of stick-to-itiveness) but because of structural factors. For one, those challenges—what they were asked to do—may not have been particularly engaging or relevant. Finger-wagging adults who exhort children to “do their best” sometimes don’t offer a persuasive reason for why a given task should be done at all, let alone done well. And when students throw up their hands after failing at something they were asked to do, it may be less because they lack grit than because they weren’t really “asked” to do it—they were told to do it. They had nothing to say about the content or context of the curriculum. People of all ages are more likely to persevere when they have a chance to make decisions about the things that affect them. Thus, if students don’t persist, it may be because they were excluded from any decision-making role rather than because their attitude, motivation, or character needs to be corrected.

There are, of course, many other systemic factors that can make learning go awry, but within the field of education, says researcher Val Gillies, “policy-makers’ attentions have shifted away from structures and processes [and] towards a focus on personal skills and self-efficacy.” Even relatively benign strategies designed to enhance social and emotional learning are sometimes motivated less by a desire to foster kids’ well-being than by a hope that teaching them to regulate (rather than express) their feelings will make it easier for adults to manage them and keep them “on task.” After all, Gillies points out, “Emotions are subversive in school.” And so is attention to structures and processes.

Who Benefits?

Nothing I’ve said here should be taken to mean that personal responsibility doesn’t matter, or that differences in people’s attitudes and temperaments don’t play a role in determining their actions. But if we minimize the importance of the environments in which those individuals function, we’re less able to understand what’s going on. Not only that, but the more we fault people for lacking self-discipline or the ability to control their impulses, the less likely we’ll be to question the structures that shape what they do. There’s no reason to challenge, let alone change, the way things have been set up if we assume people just need to buckle down and try harder.

To put it differently, the attention paid to self-discipline is not only philosophically conservative in its premises (as I’ve been arguing) but also politically conservative in its consequences:

- If consumers are drowning in debt, the effect of framing the problem as a lack of self-control is to deflect attention from the concerted efforts of the credit industry to get people hooked on borrowing money as early in life as possible.

- The “Keep America Beautiful” campaign launched in the 1950s that urged us to stop being litterbugs was financed by the American Can Company and other corporations. The effect was to blame individuals and discourage questions about who profits from the production of disposable merchandise and its packaging.

- Conservative criminologists have claimed that crime is due to a lack of self-control on the part of criminals, which, in turn, can be blamed on bad parenting. If that’s true, then there’s no need to address systemic factors such as poverty and unemployment. Indeed, the most prominent proponents of this theory have explicitly called for an approach to crime control “that would reduce the role of the state.”

- Mischel’s marshmallow experiments have been used—for example, by David Brooks—to justify focusing less on “structural reforms” to improve education or reduce poverty. Instead, we’re advised to look at traits possessed by individuals—specifically, the ability to exercise good old-fashioned self-control. Similarly, Paul Tough has declared, “There is no antipoverty tool we can provide for disadvantaged young people that will be more valuable than the character strengths . . . [such as] conscientiousness, grit, resilience, perseverance, and optimism.”

All of this brings to mind the Latin question “Cui bono?” which means “Who benefits?” Whose interests are served by the astonishing proposition that no antipoverty tool (presumably including food stamps, Medicaid, and public housing) is more valuable than an effort to train poor kids to persist at whatever they’re told to do? The implication is that if people find themselves struggling to earn a living or pay off their debts, the fault doesn’t lie with the structure of our economic system (in which the net wealth of the richest 1 percent of the population is triple that of the bottom 80percent). Rather, those people have only their own lack of “character strengths” to blame.

Consider the locker room bromides (about how a quitter never wins and a winner never quits) that are barked at athletes before they attempt to defeat another group of athletes whose coach has told them the same thing. Or the speeches at expensive business luncheons that remind us there’s no such thing as a free lunch—and sermonize about the virtue of initiative and self-sufficiency. Or the posters in which inspirational slogans, superimposed on photos of sunsets and mountains, exhort workers or students to “Reach for the stars” and assure them “You can if you think you can!”

Some of us regard all of this with a mixture of queasiness, dismay, and amusement. (This reaction is sometimes expressed satirically, with examples ranging from Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt a century ago to a recent series of parody posters called Demotivators.) We read yet another paean to grit, or hear children being pushed to work hard no matter how dull or difficult the task, and our first reaction is to wonder who the hell benefits from this. We may notice that inspirational posters and training in the deferral of gratification seem to be employed with particular intensity in inner-city schools. Jonathan Kozol pointed out the political implications of making poor African American students chant, “Yes, I can! I know I can!” or “If it is to be, it’s up to me.” Such slogans are very popular with affluent white people, he noticed, maybe because “if it’s up to ‘them’ . . . it isn’t up to ‘us,’ which appears to sweep the deck of many pressing and potentially disruptive and expensive obligations we may otherwise believe our nation needs to contemplate.”

Matthew Lieberman, a neuroscientist at UCLA, speculates that “self-control may support society’s interests more than our own.” That divergence is worth taking a moment to consider. If “society” meant “other people,” then we might infer a moral obligation to regulate our impulses in the hope that everyone else would benefit. But what if the advantages flow not so much out as up, less to others in general than to those in positions of power? Overcontrolled individuals may lead lives of quiet desperation, but they probably won’t make trouble. That’s why the social scientists who came up with the creepy phrase that opened this chapter—“equipping the child with a built-in supervisor”—went on to point out that this arrangement is useful for creating “a self-controlled—not just controlled—citizenry and work force.”

That doesn’t help your neighbor or your colleague any more than it helps you, but it’s extremely convenient for whoever owns your company.

The priority given to conformity is easy to observe when the morning bell rings for school. To an empathic educator like the late Ted Sizer, the routine to which kids are subjected is damn near intolerable. Try following a high school student around for a full day, he urged, in case you’ve forgotten what it’s like

to change subjects abruptly every hour, to be talked at incessantly, to be asked to sit still for long periods, to be endlessly tested and measured against others, to be moved around in cohorts by people who really do not know who you are, to be denied any civility like a coffee break and asked to eat lunch in twenty-three minutes, to be rarely trusted, and to repeat the same regimen with virtually no variation for week after week, year after year.

His understanding of how things look from the students’ point of view informed Sizer’s lifelong efforts to change the structure of American education. Now compare that perspective to those of experts whose first, and often only, question about the status quo is: How do we get kids to put up with it? For Duckworth, the challenge is how to make students pay “attention to a teacher rather than daydreaming,” persist “on long-term assignments despite boredom and frustration,” choose “homework over TV,” and “behav[e] properly in class”?

In her more recent research, she created a task that is deliberately boring, the point being to come up with strategies that will lead students to resist the temptation to do something more interesting instead. Again, cui bono?

Given these priorities, it makes perfect sense that Duckworth would turn to grades as evidence that grit is beneficial—not only because she assumes grades offer an accurate summary of learning but because “grades can motivate students to comply with teacher directives.” They are, in other words, useful as rewards or threats. Are the teacher’s directives reasonable or constructive? Same answer as to the question of whether the homework assignments are worth doing: It doesn’t matter. The point is to produce obedience—ideally, habitualobedience. This is the mindset that underlies all the enthusiasm about grit and self-discipline, even if it’s rarely spelled out.

Along the same lines, in an article called “Can Teachers Increase Students’ Self-Control?” (as usual, the question is “can” not “should”), a cognitive psychologist named Daniel Willingham offers as a role model a hypothetical child who looks through his classroom window and sees “construction workers pour[ing] cement for a sidewalk” but “manages to ignore this interesting scene and focus on his work.” Again, the question of whether his “work” has any value is never raised. It may be a fill-in-the-blank waste of the time, but the teacher has assigned it, and that means an exemplary student is one who ignores a fascinating real-life lesson in how a sidewalk is created, who refrains from asking the teacher why that lesson can’t be incorporated into the curriculum. He stifles his curiosity, exercises his self-control, and does what he’s told.

To identify a lack of self-discipline as the central problem with children is to make them conform to a status quo that is left unexamined and therefore probably won’t change. This is conservatism in the word’s purest sense. But it doesn’t describe only those who are trying to sell us grit. It also applies to those who worry about the possibility that children will be spoiled or feel too pleased with themselves. In fact, every chapter of this book could have been subtitled “Cui Bono?” What’s the effect, and who’s the beneficiary, of framing the problem with parenting in terms of lax discipline and insufficient conditionality? BGUTI, meanwhile, is by definition a way of teaching children that the status quo cannot be questioned, only prepared for. Obviously it’s important to ask whether our assumptions about children—what they’re like and how they’re raised—are true, and whether the underlying values are defensible. But it’s also worth asking whose interests they serve. Too often, it’s not those of the kids themselves.

If we accept the timeworn complaints that parents are too permissive, we’ll be inclined to crack down on kids by imposing tougher punishments, tighter regulations, stricter limits, less trust. If we’re persuaded by accusations of overparenting, we may be tempted to provide less support than children need (in the name of promoting self-sufficiency). If we accept the claim that kids need to experience more failure, more competition, more frustration, more conditions attached to a sense of self-worth—well, none of what follows from this advice is likely to do kids much good. Neither will a regimen of making them discipline themselves to do whatever they’re told and then keep at it.

What’s more likely to benefit our children—and to improve the society in which they (and we) live—is to turn the traditionalists’ approach on its head. How to do so is the subject of our final chapter.

Related Stories

"WHAT DO YOU CALL THAT MACHINE?"

The world is headed for a post-antibiotic era

The report, Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014, can be found and downloaded for free here.

Key findings from the report include:

- Resistance to the treatment of last resort for life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacteria, Klebsiella pneumoniae–carbapenem antibiotics–has spread to all regions of the world. K. pneumoniae is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, infections in newborns and intensive-care unit patients. In some countries, because of resistance, carbapenem antibiotics would not work in more than half of people treated for K. pneumoniae infections.

- Resistance to one of the most widely used antibacterial medicines for the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by E. coli–fluoroquinolones–is very widespread. In the 1980s, when these drugs were first introduced, resistance was virtually zero. Today, there are countries in many parts of the world where this treatment is now ineffective in more than half of patients.

- Treatment failure to the last resort of treatment for gonorrhoea–third generation cephalosporins–has been confirmed in Austria, Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Norway, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden and the United Kingdom. More than 1 million people are infected with gonorrhoea around the world every day.

- Antibiotic resistance causes people to be sick for longer and increases the risk of death. For example, people with MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) are estimated to be 64% more likely to die than people with a non-resistant form of the infection. Resistance also increases the cost of health care with lengthier stays in hospital and more intensive care required.

The Rich to the Poor: Do What I Say, Not What I Do

Economic policies often rest on assumptions about human motivation. Here’s Rep. Ryan (Republican of Wisconsin):

The left is making a big mistake here. What they’re offering people is a full stomach and an empty soul. People don’t just want a life of comfort. They want a life of dignity — of self-determination.

Fox News has been hitting the theme of “Entitlement Nation” lately. This Conservative case against things like Food Stamps, Medicare, welfare, unemployment benefits, etc rests on some easily understood principles of motivation and economics.

1. Giving money or things to a person creates dependency and saps the desire to work. That’s bad for the person and bad for the country.

2. A person working for money is good for the person and the country.

3. We want to encourage work.

4. We do not want to encourage dependency.

5. Taxing something discourages it.

Now that you’ve mastered these, here’s the test question:

1. According to Conservatives, which should be taxed more heavily:

a. money a person earns by working.

b. money a person receives without working, for example because someone else died and left it in their will.

If you said “b,” you’d better go back to Conservative class. A good Conservative believes that the money a person gets without working for it should not be taxed at all.

Not all such money, of course. Lottery tickets are bought disproportionately by lower-income people. If a person gets income by winning the PowerBall or some other lottery, the Federal government taxes the money as income. Conservatives do not object. But if a person gets income by winning the rich-parent lottery, Conservatives think he or she should not pay any taxes.

What Conservatives are saying to you is this: working for your money is not as good as instead of inheriting it. This message seems to contradict the principles listed above. But, as Jon Stewart recently pointed out, Conservatives apply those principles of economics and motivational psychology only to the poor, not to wealthy individuals or corporations.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog and the Huffington Post.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.(View original at http://thesocietypages.org/socimages)

Raising my gender creative son

While we tried to set boundaries, C.J.’s love of all things pink, purple, sparkly, glittery, and frilly knew no bounds. I realized the gravity of our plight when not only could C.J. name each Disney Princess and her movie of origin, but when his third birthday finally rolled around, he wanted a Disney Princess– themed party.

Where we live, in conservative and competitive Orange County, California, third birthdays are when things start to get out of control. It happens right around the time there are preschool classmates and parents to impress. In Orange County— especially the southernmost portion, where we live, where you can run into a Real Housewife in the grocery store or at the gym— people are constantly trying to one-up and outdo one another. Kids’ birthday parties are a big deal here. There are mobile salons that cater to tweens and mobile video- game trucks that bring every gaming system and every video game to your driveway so that the pint- sized party peeps can get their game on in an air- conditioned fifth wheel. We’ve been to kids’ parties that were fully catered and have left with goody bags that cost more than the gift we brought.

Sofia Vergara Has a Hard Time Wearing Clothes

Sofia Vergara sometimes struggles to clothe her beautiful, beautiful body. "I can barely wear an outfit or a dress that I don’t have to alter," the actress said at a red-carpet event. Sometimes, alterations are simple: taking in at a seam here, letting out at a seam there. "But other designers, I have to really, like, reconstruct them inside. At the beginning, I was getting sample sizes, which of course didn’t fit and I would have to transform them. Those were works of art that I had to do with my seamstress. Because to make all this fit in a sample size is insane!" [The Cut]