Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus and Phoebe Bridgers are all Tiny Desk alumae, but here they play together at NPR for the first time as boygenius, one of this year's best surprises.

(Image credit: Cameron Pollack/NPR)

Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus and Phoebe Bridgers are all Tiny Desk alumae, but here they play together at NPR for the first time as boygenius, one of this year's best surprises.

(Image credit: Cameron Pollack/NPR)

Peter Gorman is creating dozens of minimalist maps that he’s rolling up into a book that will be ready late next year (hopefully).

One of my favorites is this map that shows the 5 largest cities in each US state as constellations.

I also like how this map of Manhattan mostly keeps its shape only using subway stations.

You can follow Gorman’s progress on Instagram.

Tags: maps Peter GormanBen WolfI'm liking this a lot.

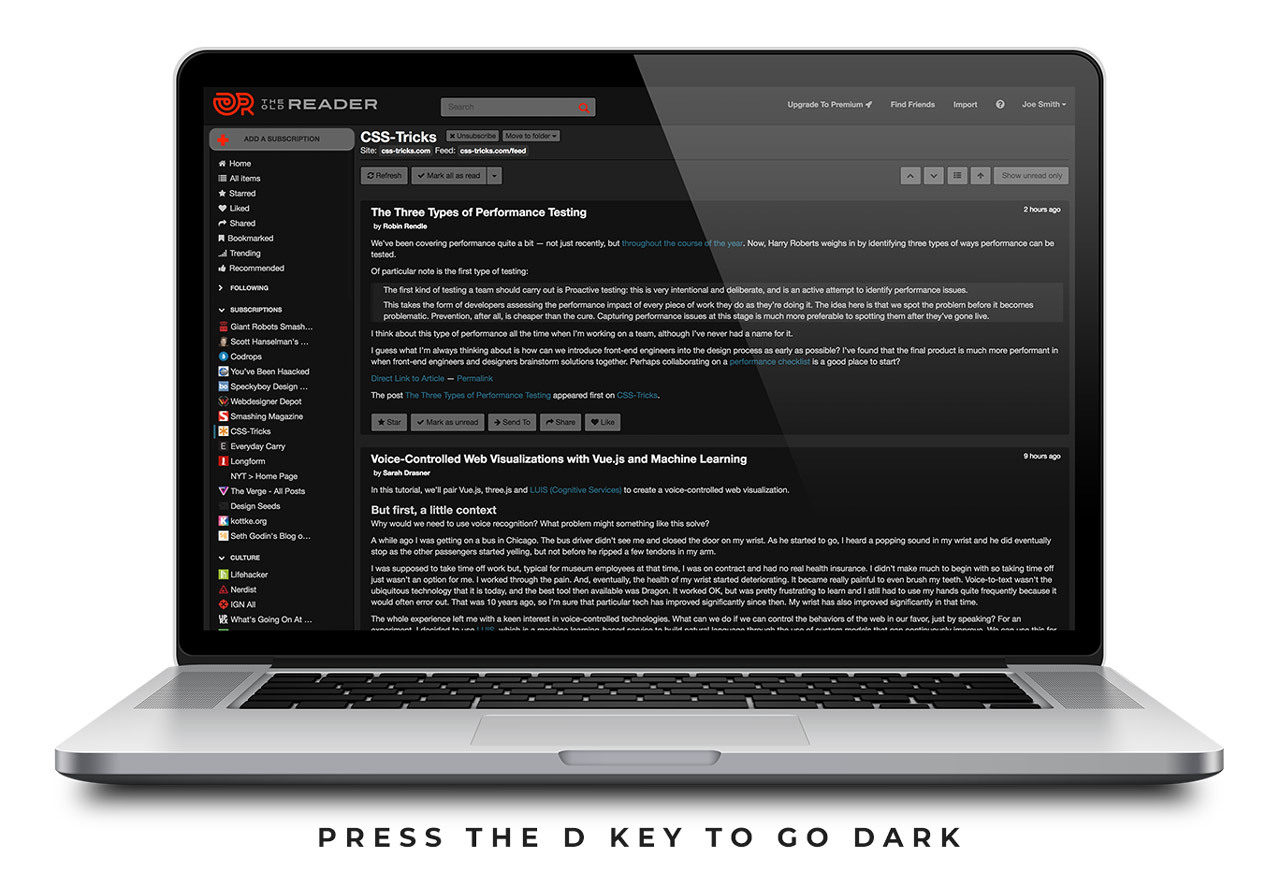

Halloween is the one holiday that’s best celebrated in the dark. Which is why The Old Reader is excited to be able to introduce the all-new Dark Mode. It’s time to embrace the dark side of reading on the web.

Okay, Dark Mode really has nothing to do with Halloween, but this seems like the perfect time to introduce it to everyone. It is all about readability, reducing eye strain, and making your experience using The Old Reader better.

Dark Mode was one of the most commonly requested features we’ve had from our users and there is even a user-created plugin that does a similar thing. With this new, built-in feature, all you have to do to use it is hit the “d” key while using The Old Reader, and voilà, you’re in Dark Mode.

Dark Mode is just one small way we want to keep The Old Reader moving forward. Give it a try, we think you’ll really like it. Thanks again for all the great feedback and happy darkmoding!

There are only two days until Halloween!!! The most high-stakes part of the evening is, of course, the trading of candy. After interviewing 10 kids between the ages of 5 and 14, we put together THE official guide…

Snickers and Reese’s are at the top of the heap.… Read more

The post A Big Guide to Halloween Candy Trading appeared first on A Cup of Jo.

Some researchers think putting lithium in our water could save lives.

Lithium is a potent psychiatric drug, one of the primary prescribed medications for bipolar disorder. But it’s also an element that occurs naturally all over the Earth’s crust — including in bodies of water. That means that small quantities of lithium wind up in the tap water you consume every day. Just how much is in the water varies quite a bit from place to place.

Naturally, that made researchers curious: Are places with more lithium in the water healthier, mentally? Do places with more lithium have less depression or bipolar or — most importantly of all — fewer suicides?

A 2014 review of studies concluded that the answer was yes: Four of five studies reviewed found that places with higher levels of trace lithium had lower suicide rates. And Nassir Ghaemi, the Tufts psychiatry professor who co-authored that review, argues that the effects are large. High-lithium areas, he says, have suicide rates 50 to 60 percent lower than those of low-lithium areas.

“In general, in the United States, lithium levels are much higher in the Northeast and East Coast and very low in the Mountain West,” he told me on a new episode of the Vox podcast Future Perfect. “And suicide rates track that exactly — much lower suicide rates in the Northeast, and the highest rates of suicide are in the Mountain West.”

If you apply that 50 to 60 percent reduction to the US, where about 45,000 people total died by suicide in 2016, you get a total number of lives saved at around 22,500 to 27,000 a year. That’s likely too high, since you can’t reduce suicide rates in places that are already high-lithium. Ghaemi’s own back-of-the-envelope calculation is that we’d save 15,000 to 25,000.

Ghaemi and a number of other eminent psychiatrists are making a pretty remarkable claim. They think we could save tens of thousands of lives a year with a very simple, low-cost intervention: putting small amounts of lithium, amounts likely too small to have significant side effects, into our drinking water, the way we put fluoride in to protect our teeth.

The size of the numbers Ghaemi is claiming should make you skeptical: Those are huge, arguably implausibly huge, effects. In 2015, the Open Philanthropy Project, a large-scale grantmaking group in San Francisco, shared an analysis with me implying that if two specific studies were right, a “small increase in the amount of trace lithium in drinking water in the U.S. could prevent > 4,000 suicides per year.” That’s significant, but far short of 15,000 to 25,000.

And while Ghaemi is very enthusiastic about the potential of groundwater lithium, other researchers are more wary. A comprehensive list of lithium studies, updated just last month, shows that while many studies find positive effects, plenty more found no impact on suicide or other important outcomes. In particular, a large-scale Danish study released in 2017 found “no significant indication of an association between increasing … lithium exposure level and decreasing suicide rate.”

The Open Philanthropy Project, which had previously been quite interested in new research on lithium, states on its website that the study “makes us substantially less optimistic” that trace lithium really helps guard against suicides.

Just this year, a study using health care claims data in the US found that greater amounts of trace lithium in the water didn’t predict lower diagnoses of bipolar disorder or dementia. That’s a different outcome than suicides, but also suggests that low doses of lithium might not have a profound effect.

These recent studies have made me less confident in the link between lithium and lower suicide rates than I was when I first encountered Ghaemi’s research. But it’s such a cheap intervention, and the odds of serious side effects sound low enough, that it seems worth a try.

At the very least, I’d love for some governments to conduct real, bona fide experiments on lithium. Maybe a state could randomly add lithium to some of its reservoirs but not others, or, conversely, a high-lithium state could try removing it from the water. There are serious ethical questions about doing experiments like this that affect whole populations, but if lithium’s effect is real and we don’t pursue it because we lack compelling enough evidence, thereby endangering thousands of people — that’s an ethical problem too.

But no study like that has been conducted. And if you want to know why, you should consider the case of fluoride.

As you probably know, putting fluoride in our drinking water dramatically reduced tooth decay, by around 25 percent per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But as you likely also know, the initial rollout of fluoride in the 1940s and 1950s was intensely controversial.

Jesse Hicks, a science journalist who wrote a great history of the fluoride wars, told me on this week’s Future Perfect podcast that the backlash started in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, with a local gadfly named Alexander Y. Wallace who was convinced the substance was poison, and who wrote a parody song called “Goodnight, Flourine” to the tune of the folk song “Goodnight, Irene.”

From there, the conspiratorial, far-right John Birch Society became convinced that fluoride was a Communist plot; the Ku Klux Klan came out against fluoride too. “I think part of the longevity of this controversy has to do with the way it can activate so many different biases and prejudices,” Hicks told me. “As soon as you start talking about putting something in the water supply you have small or anti-government people responding very vigorously against that.”

The absurd controversy continues to this day. Dr. Mehmet Oz, the wildly popular, wildly irresponsible TV doctor, has brought on a fluoride conspiracist — Erin Brockovich of Julia Roberts movie fame — to sow fear and disinformation.

If that’s the reaction to an effort to improve dental health, just imagine the public outcry against a major push for adding lithium to the water. The rap against fluoride, mocked in movies like Dr. Strangelove, is that it’s a mind-control plot. But putting lithium in the water would actually be a mind-control plot: It would be a concerted effort by the government to put mind-altering chemicals in the water supply to change the behavior of the citizenry. And I say that as someone who thinks that, if it works, that it would be a great idea! Preventing suicide is really important, but it does require changing how people think, a tiny bit.

So figuring out if, and how well, trace lithium in the water works is only half the battle. Advocates would then have to win over a very, very skeptical public.

Hicks thinks we need a rock-solid, impenetrable scientific case if we’re going to do it. The science so far is promising, but not firm enough. “When you start making it a public health policy, you activate all of these other considerations that make it that much harder to make it happen,” he says.

For more, listen to the full episode above, and be sure to tune in again next Wednesday for more Future Perfect!

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

On Start to Sale Ari Weinzweig discusses the real meaning of synergy and non-hierarchical thought

Zingerman’s, a group of 20 loosely associated businesses mostly focused on hospitality and food in the Ann Arbor area, encompasses a deli, bakehouse, restaurant, creamery, training organization, candy business, tour company and more. Behind it all sits co-founder Ari Weinzweig, an inspirational figure who spurns the idea of growth for growth sake, refuses to duplicate any business, and detests hierarchical thinking.

This week on Eater’s business podcast Start to Sale, hosts Erin Patinkin (CEO, Ovenly) and Natasha Case (CEO, Coolhaus) talk to Weinzweig about his groundbreaking Community of Businesses and theories on business-ownership.

Some highlights:

On uniqueness: “From the get go, for me, for Paul, it was very important to only have one. I really like unique things. The folks at the Positive Organizational Scholarship section of the business school here I have a little saying, which I love, which is, ‘Excellence is a function of uniqueness.’ It’s true. It’s true in the food business, it’s true in art, it’s true in music. And I’ve never been into the sixth unit of the same place and thought like, ‘Wow, that’s incredible’... Pick any great restaurant that you’ve been to, and then show me the one that opened seven years later, and it’s fine but it never has that spirit and energy that you get in the original.”

On the synergy of his businesses: “The idea of synergy comes not from some seventies buzzword but actually from Ruth Benedict, the anthropologist in the thirties who studied Native American tribes and found... that the most successful tribes were not the most competitive, but rather than most collaborative. And so synergy literally means if I help you, I’m inadvertently helping myself, and if I help myself, whether I intended to or not, I’m helping you.

So the idea was each part of the organization would be contributing back to the others just by what it did. So like when we opened the creamery and we started making handmade cream cheese, then the bagels and cream cheese at the deli were elevated to new heights. When the roadhouse opened, the bakehouse got this great new wholesale customer, et cetera, et cetera, so that each piece was contributing positively to the other.”

On growing for growth’s sake: “Going along with growth just because everybody else is growing or just because you could grow is not a great answer, in the same way that living your life the way your mother wanted you to may overlap with what you wanted, but if you’re just doing it because your mother wanted to, you’re going to end up with a hollow life and a lot of internal angst and frustration.

... Murray Bookchin, a very interesting anarchist said, “It’s sad that people don’t realize that the model of, grow as fast as you can as big as you can, is the same growth model as the cancer cell.”

On the importance of visioning: “All successful organizations, whether it be a podcast or a food business or a basketball team, have a vision of where they’re going. Businesses are not mushrooms and they don’t just pop up spontaneously after rainstorms. Somebody had to have the idea, the dream, the image in their mind of what they were going to create...

This visioning process... basically, you plant yourself in the future. If it’s for your business, it might be five years, eight years, 20 years down the road, and you describe that success and you describe that success with a whole lot of detail so that when you get there, you will actually know you’ve arrived.”

On non-hierarchical thought: “And I think a lot of what I learned from the anarchist work is to try to stop thinking hierarchically because almost all of us in the U.S. have been raised to think hierarchically. Like what’s the most important thing, what’s the top three things, et cetera, et cetera. I think that thinking is actually antithetical to what’s happening in nature, and it creates a lot of people chasing the gold ring, chasing the magic answer instead of understanding that it’s all nuanced, it’s all interacting, everything’s influencing everything else, right?”

Listen to the show in full in the audio player or read the full transcript of the interview below. And please subscribe to hear entrepreneurs from various sectors tell Case and Patinkin about their struggles and victories of business-building in the weeks to come.

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | ART19 | Read show notes

Ari Weinzweig: Thanks. It’s great to be on. I came to Ann Arbor from Chicago to go to U of M, which for those who don’t know, is University of Michigan. I studied Russian history, a particular focus on the anarchists, which we could talk about later if you want.

Erin Patinkin: I’d love to.

AW: After graduating, I had no vision of what I wanted to do. I had only what David White caused the via negativa. That’s where you’re super clueless about where you want to go, but you’re really clear on where you don’t want to go. So I just knew I didn’t want to move home. In order to not move home, I needed a job, and so I ended up getting a job as a dishwasher at a restaurant here in town. That’s how I got into food. So there was no lifelong entrepreneurial dream of opening a business or opening a food business or cooking or anything like that. I just needed somewhere to work.

And so that’s how I started. So Paul was the general manager at that restaurant when I started to wash dishes. That’s how we connected. Frank Corolla, who’s one of the partners in our bake house was a line cook, and Maggie Bayliss, who’s one of the partners at ZingTrain, our training business, was a cocktail waitress. So I don’t know why, but here we all are, the four of us plus a lot of other good people 40 years later and we’re still working together.

So anyways, I started prepping and line cooking and managing kitchens. I worked for that restaurant group for about four years. Paul left about halfway through that and opened a little world class seafood market called Monahan’s with Mike Monahan. And he and I stayed friends. Fall of ‘81, I reached a point that is not uncommon in the world, which is that I didn’t hate going to work, but I was sort of less and less inspired by what that organization was doing and where they were headed. So I gave two months notice, unsure of what would be next.

Not knowing I had given notice, Paul called me like two days later and said there was this little building coming open near the fish market that he had opened, and that we should go check it out because in Detroit where he grew up, you could get good deli food, and in Chicago you could get it where I grew up, but you couldn’t get it here. And somehow, within like a week we decided we would open and four and a half months later we opened March 15th, ‘82.

And we started in a little 1,300 square foot space selling all the old Jewish stuff that we had grown up with, corn beef, and chopped liver, and chicken soup, and all that. But also at the time, a radical if small in context, selection of what’s now called specialty foods. So a little bit of olive oil, a little bit of jam, honey, salami, smoked fish, all that sort of stuff, squeezed into 1,300 square feet.

So that’s how we started. And then fast forwarding, we operate as one organization with these semi-autonomous pieces within it. So we have a bakery, a creamery where we make fresh cream cheese and other fresh cheeses and gelato. We have a coffee roasting and candy business where we make handmade candy bars. ZingTrain is our training business. We have a mail order business and we ship food all over the country. The deli, of course, is still the main focus of the organization originally, but is one piece.

Zingerman’s Roadhouse is a sit down restaurant. It’s all regional American food. Zingerman’s Corn Man Farms is a 1830s barn and farmhouse that we totally renovated to do events like weddings and corporate events. And then Miss Kim is our second newest business, which is a really nice little Korean restaurant. And then our very newest business, as of two weeks ago, is we spun our food tours out to become its own business. And Kristie Brablec, who’s been with us a long time, but she’s now the managing partner there. So we have, I don’t know, what 20 something partners altogether and about 700 employees.

Natasha Case: Wow, is that it?

AW: That’s it.

NC: Only 20 businesses.

AW: It’s all relative.

NC: Amazing.

AW: Gigantic by our standards, tiny by Whole Foods standards.

NC: It’s an incredible feat by any standards. Can you quickly describe your role in the ecosystem? Like just give us, pick any day in the life. Give us a day in the life for you.

AW: Well, although I’m not a morning person, I get up early every day and then I journal every day, which is exactly what I did this morning, and I did it at the Roadhouse. Drink coffee, wake up, and then get going. So that could be, it could be meetings, which we certainly have plenty of, and in between, I guess I tested out a potential new brunch special item that was in my mind.

EP: So on any given day, you could be managing people, writing, or telling someone to make a different type of pancake? Is that what I’m getting?

AW: Yeah. I don’t know that it would be telling them to a different type of pancake.

NC: Very dogmatic.

AW: Might be discussing pancakes with them.

EP: Collaborative pancake effort.

AW: Yeah. So I don’t eat breakfast and I don’t eat lunch. I just taste, I’m not fasting so I’m quality checking food all day. But at some point in the later part of the afternoon, usually, depending on the day and the weather, I go run every day and then I do whatever else. And then I ended up at the Roadhouse, usually on the floor, working the floor, pouring water and bussing tables or whatever. And then I get home late, and then we cooked dinner. And then I go to bed later than I should, and then I get up earlier than I should, and start over. Yeah.

EP: Rinse and repeat.

AW: Yeah.

EP: So explain the Zingerman community model, how you came up with the business idea.

AW: Okay. So in part one of Zingerman’s Guide to Good Leading, there’s an essay called ‘12 Natural Laws of Business,’ and it is my ever stronger belief that all healthy organizations are living in harmony with those natural laws, i.e. living in harmony with nature. The first one on the list is that all successful organizations, whether it be a podcast or a food business or a basketball team, have a vision of where they’re going. Businesses are not mushrooms and they don’t just pop up spontaneously after rainstorms. Somebody had to have the idea, the dream, the image in their mind of what they were going to create.

And so Paul and I, when we opened in ‘82, we wouldn’t have been able to explain vision remotely like we do now. I wouldn’t have even probably understood it, but in hindsight, we had one, and our original vision with the benefit of history, and I’m a history major and we know this is how history is created is later, we figure out what we think happened, is that we would create something really unique and special. We didn’t want a copy of something from LA or New York or Detroit or Chicago. We wanted something unique to Ann Arbor.

We knew we wanted great food, great service, great place for people to work, but do it in a very down to earth setting. And from the get go, for me, for Paul, it was very important to only have one. I really like unique things. The folks at the Positive Organizational Scholarship section of the business school here I have a little saying, which I love, which is, “Excellence is a function of uniqueness.” It’s true. It’s true in the food business, it’s true in art, it’s true in music. And I’ve never been into the sixth unit of the same place and thought like, “Wow, that’s incredible.”

When you go to the first one, there’s something really special about it, and that’s really what we wanted to create, was this destination spot that would be known all over for doing what it did. The general wisdom when we opened was we were doomed to fail. Ann Arbor had 10 or 12 delis go out of business in the previous decade. Everybody said it was a bad neighborhood to go into. There’s no parking to this day, et cetera, et cetera. Five years later, we were geniuses. Turned out Ann Arbor always needed a deli, and everybody was behind us from the beginning.

NC: Yeah.

AW: Anyways, so fast forwarding to 1993. So about 11 years after we had opened, Paul sat me down on a little bench out front of the deli at about 10 in the morning, which is of course the worst possible time in a busy lunch restaurant to be sitting down, but anyway, sits me down and sort of with no warning asked me like, “Okay, in 10 years, what are we doing?” And I’m like, what? He’s like, “In 10 years, what are we doing?” I’m like, “Paul, I got work to do.” He’s like, “This is our work.”

In hindsight, I realize he probably was angsting and couldn’t sleep for six or eight weeks worrying about the issue. And what he, in essence, was asking me is, what’s your vision? He had an instinctive sense that we had fulfilled our original vision. I think he was right. I certainly wouldn’t have known it. It’s not like we were satisfied. It’s not like we were rich and it’s not like we didn’t have a lot of long lists of things to improve, but there’s a difference between improving what you have and going after some great long-term inspirational vision.

EP: Can I interrupt to ask a super quick question?

AW: Yeah, sure.

EP: It took 11 years to get to that point.

AW: Yeah.

EP: In that first 11 years, were there sit down discussions between you and Paul wherein you questioned what you were doing, wondered if you were doing the right thing, if you were happy, if the deli was fulfilling you?

AW: We have four. No, I don’t know. I’m sure we had a lot of them. I don’t know. I worry about everything at some level. I’ve just trained myself not to follow the worry. I think that’s a normal part of human existence, is embracing that anxiety, and I can do it a lot more healthfully now than I would have been able to do it then.

NC: It’s sort of a working on the business, not just in it kind of mentality that starts to evolve.

AW: Yeah, absolutely. I think that in the beginning when you only have two employees like we did, it’s appropriately a lot working in the business. It’s not that what we were doing was wrong in the beginning, it’s just as we grew, it became apparent to us both instinctively and through reading other people’s stuff that we needed to work more and more on the business. And you know, that’s part of the work.

EP: Absolutely. So you created this vision 11 years in.

AW: Yeah. So we spent about a year of our ... He didn’t have the answer. It’s not like he had a vision that he was advocating for. It just, he had the sense that we had fulfilled it. And so I didn’t know what I wanted to be doing in 10 years. I had no clue. So we ended up spending like a year of arguing about it, and talking about it, and conversing, and coming back to the table over and over and over again. And that was the first time we actually wrote out a vision in the way that we do it now.

And that vision, we actually went 15 years into the future, not 10, and that’s where we outlined the idea of the Community of Businesses and that vision is the first time we really learned this process, and we learned it from a guy named who very sadly passed away about 15 months ago, but he learned it from a guy named Ron Lippitt who was at University of Michigan in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. And so that’s what we set out to do.

NC: So you mentioned the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses. So how are all of those linked?

AW: So we could have clearly created a vision or a future where we were going to, whatever, invest in other businesses and then the businesses themselves might have had nothing to do with each other, but for whatever reason, and I think it worked out well and I’m happy we did it, but what we determined in the vision is that it would be this singular organization, but with these pieces within it that were operating with a great deal of independence, and that we would create a synergistic setting.

And the idea of synergy comes not from some seventies buzzword but actually from Ruth Benedict, the anthropologist in the thirties who studied Native American tribes and found what Peter Kropotkin, the anarchist, had found earlier, which came out in his book in 1902, Mutual Aid, but that was that the most successful tribes were not the most competitive, but rather than most collaborative. And so synergy literally means if I help you, I’m inadvertently helping myself, and if I help myself, whether I intended to or not, I’m helping you.

So the idea was each part of the organization would be contributing back to the others just by dent of what it did. So like when we opened the creamery and we started making handmade cream cheese, then the bagels and cream cheese at the deli were elevated to new heights. When the roadhouse opened, the bakehouse got this great new wholesale customer, et cetera, et cetera, so that each piece was contributing positively to the other. So we do have a central services organization that’s funded by a percentage of sales from each of the businesses, so like HR and marketing and that kind of thing. But there’s a lot of freedom and autonomy within each business too.

EP: I think that’s important for the audience because I think not being in Ann Arbor, never seeing the whole thing, and what you’ve done is so different than what other people have done. And I can’t think of another place in the United States that is doing something that you guys are doing.

NC: Yeah, you really thought outside the box with the structure, sort of like what you said about, I think a lot of people apply the uniqueness is that excellence to product or to team, but they don’t necessarily rethink the whole model of how they’re going to literally be in business. So that’s pretty amazing that you not only did that, but that it’s thriving.

AW: Yeah. Well I think that’s ... So there’s one of the key actually beliefs of anarchist thinking is that the means that you use must be congruent with the ends that you want to achieve. So agreeing with what you just said, in hindsight, it makes a lot more sense that we would have been able to create uniqueness in the business by using a unique model.

EP: So how specifically are you, are all of the companies working together? What is the structure by which the Zingerman’s Community operates?

AW: Well, interestingly, there’s really never been a legal entity, Zingerman’s Community of Businesses. It just exists in our minds.

NC: Oh my gosh, that’s amazing.

EP: Stop, stop.

AW: No, it’s true. So Paul and I own shares in all the businesses, but the key is that we operate as one organization, so it’s sort of like Tinkerbell rules. As long as you believe, it works. But more formally, we actually have a lot of governance stuff that’s super clear that we’ve worked on, imperfect though it is, that we’ve worked on for decades. So we run the whole organization at the partner’s group level. Every month, there’s a Zingerman’s Community of Businesses huddle, which is the open book work so that those meetings are open to anybody in the organization that wants to come.

We even get outside people sometimes, not through intent, but they’re there, whatever. And we use a consensus model for decision making amongst the partners, and that consensus three years ago or four years ago, we added three staff partners. So these are people who are not managing partners. They’re hourly staff managers, whatever, and they’re chosen through a whole process that I’m not going to get into now. But so they’re part of the consensus.

So in essence, from a formal standpoint, they have the same say that Paul or I have in the decision making. So that’s for organization wide decisions. Then within each business, there’s managing partners and they’re running their business too, right? And then we also, I mentioned the central services and then we do a lot of what we call one plus one work. So again, there’s an essay on this in the most recent book, but these are like work groups. So we have a benefits work group, a training engineers group, et cetera.

And those are generally coming, people coming from different parts of the organization and the main one and the one plus one is the person’s core work. They’re a baker or they’re an accountant or whatever. But the plus one is an optional piece where they’re getting involved in a different part of the organization in a different role. So you might be a baker full time but you’re on the benefit committee, and it’s connecting people in different ways than they normally would connect, and so instead of everything being hierarchically arranged where it all has to flow up, up, up to the top and then back down the other side, you’re getting a much healthier array of relationships, which I think is far more resilient and effective.

EP: So do each of the managing partners own shares in all of the company?

NC: And are the companies their own incorporated entities?

AW: They are, except now some are LLCs but for all practical purposes it’s the same thing. So up until three years ago no one owned anything other than their own business, but they were charged with running the whole organization. At the partner’s group level one of the things we did early on, which now we can say was an inflection point, was that we asked, when people are in the partner’s group making decisions, all of our charge is to make the decision that we believe is best for the organization, not the decision that’s best for our individual business. Right? So there’s a lot of things that I’m talking about that are the total opposite of the American political system.

So no voting, because voting leads to disconnect and anger and resentment because immediately somebody lost and they’re mad and set about trying to destroy the one who won, and vice versa. And then people aren’t representing their business, they’re charged with making the decision that’s best for the organization.

Now, we might not all agree on what that is, but like Maggie from ZingTrain, we’ll frequently say there are times where she’s made the decision at the partner group level that’s actually not good for ZingTrain, but it’s a small part of the whole Zingerman’s Community of Businesses and it’s clear that this decision is better for the group, even though for her little business it’s not super optimal.

That’s totally the opposite of I represent, pick your state, and yeah, this is bad for the country but I’m looking out for the voters in my state. That’s not ill-intended, but it just creates this constant disconnect and conflict.

EP: Okay. Great.

AW: I guess I should finish with saying so three years ago, after six years of trying to figure out how to do it, we created an employee ownership piece which we call community shares. It took a very long time because there’s no model like ours, as you said, and so we basically, Paul and I own shares in the businesses, but we also own intellectual property and so we took a piece of the intellectual property ... I’m going to go fast and people have a million questions, but they can email me and it’s AW@zingermans.com ... and that became the community shares, right? It’s a co-op model, so everybody who is eligible can buy only one share, including me and Paul, and that now makes it so people own a small piece of the brand.

EP: Was this something that you had come up with individually? You came together to decide this?

AW: I woke up one day. No.

NC: The Russian anarchist gave you the idea.

AW: ... No, because it is, it’s a lot about autonomy, and federalism is actually a big piece of anarchist stuff. But that’s not what was, consciously it wasn’t. But no, a lot of the visioning work as we do it is all about collaboration, and collaboration frequently means creatively dealing with conflict and coming up with win-win solutions, and so I was super adamant about only having the one business because I just, everywhere I’d been in the food world and really, I think in any industry, when you go to the sixth unit it’s just never as interesting as the first one.

It’s not bad and people like the convenience of having it closer in the suburbs or whatever, but it’s just never the same. Pick any great restaurant that you’ve been to, and then show me the one that opened seven years later, and it’s fine but it never has that spirit and energy that you get in the original.

So I was really driven to keep that and make it even better, and Paul really wanted to grow, which I wasn’t opposed to, I just didn’t know how to grow while keeping the one business unique and special. So anyway, out of that creative tension, this is what we ended up with. We could grow but we would grow by opening other Zingerman’s businesses, where each would have its own unique specialty.

And then also, I really wanted owner’s on site. My experience of the work world, not always but in general, is that when the owner is present you just get a different buzz and energy than when there’s absentee ownership. I understand clearly, there’s some great managers in the world and there’s some lousy owners, so it’s a generalization.

Anyway, we wanted managing partners that would own part of the business and really be part of running it and so that’s what we created. But I mean this isn’t like we just sat down and wrote this. I mean this was a year of frustration and conversation and trying to figure it out.

NC: Something I want to get into is, you talk a lot about great business versus big business, and I’m wondering first if we can just hear directly from your mind how you really define those two things and how they’re separate to you.

AW: Well, I’m not sure they’re separate. I think the key is that greatness is an internally determined future, right? So there’s no right answer as to what’s great. The key is that you decide what’s great for you. If going public and being global is somebody’s definition of greatness, I think they should go for it.

But I think going along with growth just because everybody else is growing or just because you could grow is not a great answer, in the same way that living your life the way your mother wanted you to may overlap with what you wanted, but if you’re just doing it because your mother wanted to, you’re going to end up with a hollow life and a lot of internal angst and frustration.

I think with business, the key is that people hopefully can realize that they get to decide. In the food business you could have, I don’t know, you could have a little diner with 12 seats at the counter, and you’re the chef and owner, and you cook almost every meal, and I think if that’s what makes you happy that’s totally great. There’s no right or wrong.

NC: It’s sort of the harmony point, you’re saying. That there should be a harmonious element with what you might not.

AW: Yeah, with what you want. It’s what you want. I mean it’s how you want to work, and it’s how much you want to work, and it’s where you want to work, and so I’m not ethically opposed to bigger businesses. People have grown because they think they’re supposed to grow, or they grow because they could grow, or they grow because they’re chasing money because their cousins all make more money than they do, and they feel like they should make money.

EP: Someone told them to, or that-

AW: Yeah, yeah.

EP: ... or that, I think one of the dangers is a lot of business owners think growth means success, and then there’s a lot of unhappiness that can come in with that. I think it’s a really important moment to say how big do you want to be?

NC: Yeah, and also AW, what you’re saying, even to just take the time to really meditate on that, to think about and visualize what that’s going to feel like for you, versus personal goals.

AW: Yeah, and that’s the visioning process that we use and teach. I mean it’s designed to do that, and it’s a specific process. It’s not just sitting around thinking about it, because you could think yourself, or at least I could think myself, to death. It’s a process of doing it, but the point of it in this context is it’s a very inside out exercise. I’m trying to work more, not less, or I’m going to run out of years. So people want to work less, I don’t really care. What I care is just that people are doing something that’s aligned with the kind of life that they want to live.

NC: Right. There’s no one way.

AW: No, there’s no perfect way. Rollo May, the mid-twentieth century psychologist, who I never met but seems super interesting and insightful, said that the opposite of courage is not cowardice, it’s conformity. And there’s enormous pressure to conform. That’s difficult. Murray Bookchin, a very interesting anarchist said, “It’s sad that people don’t realize that the model of, grow as fast as you can as big as you can, is the same growth model as the cancer cell.”

NC: That’s interesting. Speaking of no one way, workplace culture. This is a big one for you and it’s certainly becomes a bigger and bigger theme, I know for us at Coolhaus it’s huge. But can you speak to the specific things that really create that buy in? What do you think are the ones that move the dial, that you guys do and practice, that are game changers for your team?

AW: Well, I think there’s a million things. In the most recent book, which is Part Four of the Leadership Series, I started to work more actively with the metaphor for organization of ecosystem, because almost all the models of business, and saying this respectfully, but even the idea of moving the needle all comes from machines. So high performance organizations, and keep the gears greased, and all of that stuff is based on the industrial model, and it’s all based on machines, which is very dehumanizing and not aligned with nature.

I just started to imagine, I’m sure others have done it too, but more and more the idea of organization as ecosystem. In a healthy ecosystem in nature, one of the key parts is that everything’s contributing and everything matters, even the things that seem really statistically insignificant, like bees, turn out to have enormous implications.

And I think a lot of what I learned from the anarchist work is to try to stop thinking hierarchically because almost all of us in the U.S. have been raised to think hierarchically. Like what’s the most important thing, what’s the top three things, et cetera, et cetera. I think that thinking is actually antithetical to what’s happening in nature, and it creates a lot of people chasing the gold ring, chasing the magic answer instead of understanding that it’s all nuanced, it’s all interacting, everything’s influencing everything else, right?

So the culture, I mean all the things that are in the books, are things that influence the culture. Vision, leadership, customer service, et cetera. I mean there’s dozens and dozens of things, and just everything down to did the leader greet the newest employee with a smile, is a big part of the culture, right? So understanding that it’s all of this nuanced stuff and that there’s no perfect model, and even in a healthy ecosystem there’s still problems and things that are failing. It’s just that the overarching health of the ecosystem will help repair those problems relatively quickly, whereas in-

NC: And is it, sorry to jump in, but you have a lot of people in the organization now. How does everyone touch this philosophy? I mean there’s a certain amount maybe they can garner from the interaction, but is it like there are words and passages that must be read, and then are trained and practiced? Or how do you get this philosophy into their heads and into their actions?

EP: Especially with such a diverse staff, because that must mean you’re dealing with everyone from porters to CFOs.

AW: Yeah, yeah. But because, again my anarchist thing, the CFO doesn’t really know any more than the dishwasher knows, they just know different things, and they’re not necessarily more intelligent or more capable. So part of my, our, strong belief is like everybody’s, I’m just going to believe everybody’s a creative, intelligent human being that can do great things. Then I’m going to treat them accordingly, right?

EP: Sure, but I think the reality is also just people respond differently to different ways that they’re taught.

AW: Yeah, absolutely. That’s for sure, but that’s true of CFOs.

EP: Yeah, totally.

AW: So the answer to your question is they’re learning it in a multiplicity of ways. We have, I don’t know what, 75 different internal training classes that we do, but those are spread out and not everybody goes to all of them. They’re going to learn stuff on shift, right? They’re going to learn stuff culturally, so just through conversation with their trainer who might say oh, that’s not how we do it here, or yeah, yeah, that’s what happened at my old job, but when I came here I realized x.

So they’re getting it formally through our “educational work,” but they’re also getting it culturally, I think when those two things are not aligned, then you get a lot of problems. There’s a lot of unhealthy organizations where they might have a fabulous handbook but nothing remotely close to that happens in real life, and that creates a lack of integrity and a disconnect that’s really problematic.

NC: Yeah. I was going ask, if someone were more starting out and may not have the wherewith all on lets say, the classes and those, like you said, those more formal training sessions versus getting it from the culture, what do you think is the number one thing that they could do to help instill that from the get-go?

AW: See, there’s that hierarchical thinking.

NC: Like a specific thing.

AW: You’re asking about what the organization could do to instill it in a new staff member?

NC: Yeah, let’s say.

AW: Well, again I don’t think there’s any one thing. I think it’s just being super mindful of every tiny interaction. So literally, how they’re greeted. Literally, did the owner go, the leader, the manager, whatever, go seek them out and welcome them? But more formally, one of the things that we still do that I think is really impactful, and I wrote and essay on it in the newest book, is that Paul or I still teach the new staff orientation class ourselves. I think that’s huge, because it’s the time that the leader is really-

NC: It’s a personal connection.

AW: ... sharing the history, sharing the philosophy, getting to know just a little bit about who the new employee is. Your point about diversity, I mean, it’s mixed from the organization, so literally when I teach it, it could be a new dishwasher, it could be a new head of HR, it could be a 16 year old and a 60 year old, and they’re all sitting at the same table together and there’s no correlation between their ability to have insights and the formal title or age or seniority.

Actually, I taught a class on servant leadership about six weeks ago, and one of the people who came worked part-time for our catering. I can’t remember if he asked me, but I think he asked if he could bring somebody with him, and I just said, “Sure, why not?” Who he brought was a sixth grader from a non-profit program that he works with, that he’s mentoring this kid, and his name’s Christian, the kid, and so we do intros in the class, and we do intros, at any meeting or class we start with ice breaker introductions. Sometimes when somebody brings a kid, because it’s not the first kid who’s come to a class, they just sit there and color, they do their thing on the computer, whatever, but he actually introduced himself the way everybody else did, and talked about who he was. Then through the class he starts raising his hand and making comments and asking questions, and they’re as good as everybody else in the class. It’s great, because-

EP: Maybe more honest, and that’s something kids bring.

AW: Well, it’s engaging. Well, he wants to be president but he might be in the NBA first.

EP: Humble goals.

AW: Why not? It’s okay. He was super nice and grounded, and his insights and comments on the class material were really good.

EP: I have a question for you. All right, so you mentioned you have over 700 staff. Have you found that there have been inflection points where the culture almost crumbled? Where you’ve had to regroup and rethink about your culture?

AW: Every day.

EP: Is that before or after your jog?

AW: Either.

NC: During.

AW: I mean I don’t know, but I think inflection points are overrated and they’re only created by history. So I think the reality is, it’s all failing and succeeding simultaneously every day, right? And I think none of us do it well enough. I don’t. I think we’re all making mistakes and that we’re all at risk, but I think that’s our work, right? So coming back to the idea of ecosystem, I mean even in the most beautiful forest, there’s still some trees that are dying, there’s still some problem patches, whatever.

Again, the idea is to create organizational health that overrides the disease. And then to keep working on improving things, so it’s never perfect. It’s always falling short. I mean, I don’t know, pick your metaphor. In a big basketball game, whatever, you’re in L.A., Kobe Bryant. If they won the championship, they still missed a lot of shots and they made a lot of bad decisions during the game. But they won the game, and nobody really worries about it.

EP: Is there a way that you internally measure culture? Do you have any ways that you can quantify intimation to see if you’re ... I know everything is failing and succeeding every day, I totally agree with that, but ultimately you still have to move more towards success than you do failure.

AW: No, without question. I think the key is multiple metrics, so again, if you have only a singular metric in anything in your life, it’s not going to work. If you’re metric of personal health is your body weight, that’s great, but you still need to know your blood pressure and your cholesterol level, and your whatever. And I think in organizations when people pick only one metric, that’s not healthy either. So we do a staff survey.

I think the financial metrics are certainly one metric, one way to measure, and we have multiple of those. We have service metrics, food quality metrics, and they all impact each other, right? So if people aren’t engaged in their work and they don’t really care, the quality of the product is going to suffer.

Even though that’s not a direct metric of workplace satisfaction, which is a bad word anyway, happiness or well being is probably better, it’s telling you that there’s something wrong. Right? Because when people really care and they’re living the systems that they helped to design, the product is going to come out good.

NC: Do you find that you’re able to get, if people are unhappy, are you able to get that kind of openness for them to share that with you, because it’s historically so difficult? You don’t necessarily want to tell your boss, even if it’s feedback that could be very constructive, there’s a fear with, okay, then I’m rocking the boat too much, or I just want them to think I’m happy, so they think I’m doing a good job. How do you create that back and forth dialogue? And what tricks are there to be found that work, if so?

AW: It’s hard. I mean it’s hard for me, and I’m the whatever, co-CEO of a sixty-something million dollar company, and it’s awkward for me to bring stuff up. I don’t want to do it. I guess part of it is honoring, not that everybody believes me, but I’m afraid of all of it. I just learn to try to do it anyway. I think there’s a common misconception and a commonly used statement that we have to make it so people feel comfortable bringing up the difficult thing. But I’m like, “I’m not comfortable. I’m never gonna be comfortable, I just need to do it anyway”, and then it’s, again, it’s systemic, it’s cultural.

So, we have process we teach in the class on it that’s about four steps to going direct, so that helps. We’re open book management so people are in huddles. We have staff survey, we have managers, staff chat sessions. We ... and then if you’re present and you’re engaged, people are gonna tell you things that they’re not gonna call headquarters and Antwerp, and report, necessarily. So its all of the above, I mean ... and it’s still imperfect and it’s just trying, it’s like any relationship. Anybody who has been in a long term relationship, it’s not like you bring up every issue the day that it happens, I don’t think. I mean, usually I think about it. Is it me, is it her, is it ... have I brought it up, should I bring it up, am I really being empathic enough?

It’s a complex, emotional intellectual construct, and if you have seven people, they’re all somewhere in that construct, generally moving from place to place within minutes sometimes, depending on other things. So, again, it’s just trying to create a healthier eco system. Maybe one person is too anxious to bring it up but they’re gonna complain to their coworker, who’s gonna go, “Come on man, I’ll go with you. Let’s go to the huddle, we need to bring this up.”

EP: Culture, obviously extremely important. Effects staff well-being, affects how customers perceive their experience, et cetera.

AW: Right.

EP: You also have a unique model, from what I understand, of how the new businesses begin within the community. So, if I had a business idea and I wanted to join the Community of Businesses, what would I have to do to start my concept within Zingerman’s, and then, how do the current managing directors vet the people coming in? Do you have a way of figuring out if someone is vision and value aligned with you, if it’s gonna be the right partner. Tell us a little bit about that?

AW: Well, I was just thinking about when you brought up culture again, metaphorically I started to look at culture as the soil in the ecosystem because when you study organic, sustainable, whatever agriculture, it’s always about feeding the soil and creating more health. I think the partners emerge hopefully from a healthy soil in the first place, but we have a whole path to partnership, which is a documented process which started out completely undocumented and much looser. Every time we screw up something, we add another piece to the process to try to avoid the pain point.

The point of the process is just what you described. I mean, as best we can to see if the person’s values aligned and vision aligned, et cetera. When Paul and I do the new staff orientation class that I mentioned earlier, one of the things that we both bring up, each in our way, is that literally everybody at the table, or anybody at the table could become a partner in the organization, and we hope that they will be. If they have an idea about a Zingerman’s business that would fit with what we do, and it would be geographically here in town, we would love to talk to them. So, that’s really how it starts, I mean, as a conversation.

A next step would be for them to draft division of what that business would look like, and then of course, there’s a lot of back and forth and iterations of drafts, and then the formal process moves forward. We asked the people working the organization for at least a year, that they do a leadership change project, that they go through our leadership development program. Stuff like that, where we’re ... it’s not perfect but its just trying to get people more and more engaged with the work that we do, and the way that we do it. I think, really, honestly we learn a lot just from, or I learn a lot and I think they learn a lot from going through the process, because like all long term projects, there’s moments that you feel like, that you describe before. You feel like you’re failing, there’s moments where its like, I’m gonna kill these guys, it’s never gonna work, and there’s moments where its like, this is gonna be fabulous, we can do this.

I think that we learn a lot about the quality of the partnership, or potential partnership from those frustration points, and from those success points. Then it sort of gets near the end. They’ve had conversations with the other partners, et cetera. I should mention we make organizational decisions at the partner group level, which means a consent, and we use a consensus model at that level so, they will have talked to all those people. There’s the formal application they fill out if everything’s gone well to that point, and then from there we go into town hall meetings with frontline staff.

There’s a final approval, which by that point, it’s sort of a done ... pretty much a done deal because it’s gone on so long, and everybody’s been a part of it. That’s actually just what happened last Thursday with Kristie Brablec, with this food tour business.

NC: Wow. Is there a cash buy in as well, right?

AW: There is. We don’t look at the partner as the major funding source, per se, because I mean, we’re not looking for people with necessarily with. We’re not opposed to it, but generally if somebody is coming from within, they’re not sitting on zillions of dollars so, it’s more-

NC: Gives them skin in the game.

AW: Exactly.

EP: Have any of the companies in the community failed, or have you ... is there any moment where you had a Brexit, where you were like, “You gotta, we gotta break up. You gotta get out of here.”

AW: Well, Brexit’s fairly extreme. But, yeah we have ... I mean I think this is, Paul taught me this early on, is if we’re gonna do this there’s gonna be failures. Again, in the ecosystem model, it’s less cataclysmic and sort of in the sports model, its like this horrible thing we lost. In the ecosystem, I mean ... my girlfriend’s a farmer. I don’t remember how many pepper seeds she put down, but a lot of them didn’t grow. There’s stuff that she didn’t think was gonna be as successful as it is, that’s growing really great.

Right, so, I think again, it’s the overall success is what we’re trying to look at, and to honor the reality that there’s gonna be failures and frustrations. That’s hard for me, coming from a perfectionist upbringing, but then to realizing over the years that actually nature is imperfect, and so perfectionism is actually the pursuit of the unnatural.

NC: Can you tell a story of a specific, I’m trying to go with my nature metaphors so I don’t scare you off with more machine, parallels, but when the tree was chopped, or ...

AW: Yeah. Well, yeah. I mean I’ll go back ...

NC: There was a weed you had to pull.

AW: Yeah. I mean, I’ll go back a long ways so, it doesn’t impact anybody in the moment directly, but

NC: This is top secret, don’t worry. No ones gonna hear.

AW: I thought there’s like, you told me there were 40 million listeners to this podcast.

NC: Oh, yeah there are. It’s four billion actually.

AW: Billion, that’s so cool. I heard this is listened to regularly on Mars, yeah. We had a low produce market, this is in the mid 90’s, and it didn’t work. It’s not through malice and it’s not through anything. The partnership didn’t work out and it’s painful, I mean, it’s like getting divorced. It’s not fun, you can go through that process with grace and respect, and dignity is difficult and stressful, and challenging as it is and still come out the other side. I’m sure we didn’t do it as well as we could’ve, but that’s what we try to do.

NC: Sometimes you have to reboot. Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

AW: There you go, another machine metaphor. People leave the organization, and super important we would say, and I believe it strongly. We need to treat them with dignity when they leave because they’re free human beings and they have the right and freedom to choose to not be there. The reality is a lot of them, that just actually happened this morning, one of them is coming back because, well, other ecosystems are not always so healthy.

EP: Yeah. We were just talking before this, that second marriages often are more successful than the first, so.

AW: Well, you learn a lot by failure, too. I mean, it’s seriousness ...

NC: Just opening a flood gate with that one.

AW: Yeah. That’s a different podcast.

EP: That’s a different podcast. We’ll stay away from that for now.

AW: Well, I think we learn ...

NC: These parallels are useful, yeah. I think, obviously what you created is so big and so great that it can withstand, like you said ... there’s gonna be failures, there’s gonna, but there’s the greater good is a broader operating ecosystem. So, it allows for imperfections and flaws to kind of organically work their way out, or sometimes, like you said, back in.

AW: Yeah. It’s not a totally wild ecosystem so, there’s a farmer, right. But the point is to work in harmoni- ... in ways that are harmonious with nature, and that, in nature the healthiest ecosystems are the most diverse, and so in the same way within organizations. So, because we’re in so many different businesses, or industries within organization, we really never get the boom years that a lot of ... like if you’re in a really great spot in a particular industry and everything booms, then you rock it to the, whatever. For us, it’s more likely that three or four business are doing well, two or three are struggling. And that sort of shifts over time, but it also provides more stability.

EP: We have, like you said, I think there’s so much more that we would love to ask.

AW: We could do a whole podcast.

NC: I know, yeah.

EP: I’m like, “oh my gosh, I don’t know more.”

NC: I mean, even what we have learned is so valuable and cool, and it’s incredible what you built, truly, from the inside out. So, thank you for what you’ve brought to the planet.

EP: From my perspective, my company reads your books, we bring it Zingerman’s for training, and it’s just really amazing to have you here with us today.

NC: Yes.

EP: We have one last thing.

NC: The skill?

EP: The skill.

NC: You have eluded to, you’ve described, actually, tons of school and the ways in which you do what you do, but what we’re wondering, ‘cause we really wanna create for our audience, some takeaways that they can really apply to what they’re doing. So, is it possible, of all these great, to choose one and really break it down for us, how you do it, so that a listener can go and apply that skill themselves potentially?

EP: In their business.

NC: In their business, or life.

EP: Or life.

NC: Or nature. All of it.

EP: To that point, I would say, part of what makes our approaches work, is that they actually are identical to what you do in your personal life. So that instead of what most businesses are doing, which is teaching stuff that’s almost antithetical to what you’re trying to do at home, this is teaching techniques and processes, and mindsets that are the same, whether it’s with your kid, or whether its at work. But anyway.

I don’t know. Visioning, does that sound good?

NC: Sure. Let’s break it down.

EP: Lets break it down.

AW: Okay. So, and I’ll just say, because I don’t wanna space it out, but so with the business books, we actually are sort of off the grid, so we print them here in town. We do all the design and everything, and so it’s sort of the farm to table version of books. So, we’re kind of not on Amazon, so they’re at Zingtrain.com, along with the training seminars and there’s a whole two day seminar on visioning. I’ve written a bunch of essays about it that are gonna give you way more detail than I’m gonna fit in to the next three minutes.

So, the visioning process I will say, changed my life. It’s completely not how I grew up, it’s almost the opposite of how I was raised. It’s basically a process of getting clear on what we talked about earlier, which is, what does success look like for you. So, not what is the business school tell you you should do, not what’s your competitor doing, not what’s possible theoretically, but what does success look like for you, so.

NC: Do you draw this, or think this, or write this, or any of the above?

AW: We write it. I know a lot of people work with vision boards, which I think is a good way to, if you’re a visual thinker, to trigger ideas, but my belief is that although the vision board will be super clear to the leader who created it, the odds of someone else interpreting it, seven layers through the organization, remotely close to the original, is not that high and that we live in a culture that’s written, and that the writing is clearer to people what you mean.

This visioning process, like I said, was developed in it’s core work by Ron Lippitt, and he called it preferred futuring. We’ve adapted it and adjusted it somewhat, but it’s still basically that process, which is basically, you plant yourself in the future. If it’s for your business, it might be five years, eight years, 20 years down the road, and you describe that success and you describe that success with a whole lot of detail so that when you get there, you will actually know you’ve arrived.

Our current vision for 2020, which was written in ‘07 over about an eighteen month period, is nine pages long. So, it talks about how people will feel that work there, it talks about how the community will feel about us, it talks about having fun, it talks about learning and people coming from around the world to learn. It doesn’t reference podcasts because we didn’t know they existed in 2007, but anyway.

The point is that you’re describing success, so it’s basically writing a story but it’s your story, and it’s written in the present tense, as if its already happened. It’s an affirmation, it’s not a statement of what’s gonna happen. It’s as if it already happened.

NC: I like that.

AW: It’s not a list. I like lists, but bullet points are not the same as a vision because there’s no emotion in the bullet points, and the vision is all about emotion, right. It’s about yes, roughly what are your sales gonna be, so you have some idea of scope and scale, but also how do you feel when you go to work. Not every detail of what you do, but if you’re passionate about woodworking, then put it in there.

We use vision for everything, so it’s not just for the organization. People write personal visions, we write visions for projects, we write visions for changes we’re about to implement. It becomes really a way of thinking and through neuroplasticity, which people now know the brain changes shape, and you change the way you think overtime. If you do use the visioning process regularly, for a period of years, it really shifts your mindset from what most of the world is doing, which is fixating on what’s wrong and who’s screwing it up, and who’s keeping them from where they want to go, into a much more positive affirmative mindset of what do I want to create and what will this look like, feel like, in our case, taste like when it’s working really well.

NC: So awesome. I have to share really quickly, that our first angel investors/mentor coach, who got involved with Coolhaus, this is one of the first activities he had us do, is he called it Vision book, and it was a complete game changer for us. And I think just the accountability of putting it on their page, it does kinda push you to strive for it for yourself, for your team, for those outside your organization, you may be looking to attract. It’s such an amazing feeling to look back at something you put on a page, theoretically, and say, “Wow, I did that.”

EP: Also, I think that there’s so many of us, we did this vision, your specific exercise, my business partner and I. We’ve done it twice. I think one of the things that was really amazing about doing this, and why anyone listening to this podcast should try it, is because I think a lot of us just doubt ourselves so much everyday because we’re afraid to admit that we have talents, or we feel insecure about our ability to accomplish or whatever those things are. And what I loved about writing this and writing it in the present, as though it’s 15 years or 10 years in the future, or however many years you want to take it, forces you to think about what you can do to get there.

I think that one of the things my business partner realizes, as women, we can be humble to the point of self deprecation and it really took us out of that, really was fundamentally essential to our partnership, and to the company when we first did it. So, I love that exercise and I’m glad that’s the skill that you chose to break down.

NC: Yes, thank you. For sure, that’s a huge one.

AW: Changed my life.

NC: I wish we could talk to you so much longer.

EP: Me too.

NC: But, I wanna thank you for joining us today and for all you’ve shared, and just so excited to see where ... what’s next for you and where this all continues to go.

AW: We’re working on the next vision, so we’ll see where that goes, and people can email me directly if they want. It’s just Ari@zingermans.com.

NC: Awesome, thank you AW.

AW: Thank you. Have a wonderful day.

EP: Thanks for listening to start to sale. We really want to hear what you’re getting out of the conversations we’re having with these wonderful entrepreneurs, and we wanna know what you want more of. Are there entrepreneurs that you love, that you want us to talk to, is there a resource you need? Feel free to send us an email at hi@starttosale.co or direct message us on Instagram. I’m and Natasha is @natashajcase. We’d love to hear from you if you’ve been able to apply anything from start to sale to your business.

The Economist, famed enemy of billionaire worship, says the media (and its consumers) have an unhealthy obsession with the work habits of successful businesspeople, especially their long hours and early mornings. By acting like getting up at 5:30 is what made these people rich and powerful, we ignore the obvious, says the socialist outlet:

If long hours were the key to success, after all, people who hold down two jobs, or nurses on the night shift in emergency rooms, would be rolling in wealth.

Other clichés of executive profiles—meditation, enforced “off hours,” limited screen time—might seem to contradict each other, but they all fit the same narrative: that these execs are “earning” their status, that the reason they’re so much richer than the rest of us is that they’re more virtuous than the rest of us. The Economist again:

No boss is going to admit that on Friday nights they consume pizza and watch box sets of “Game of Thrones”. Instead they claim to meditate or read improving books. Many business profiles resemble medieval “lives of the saints”, with the subjects of the hagiographies receiving share options instead of canonisation.

These details also reveal a lot of privilege—you really don’t have as many hours in your day as Beyoncé—sometimes earned privilege, sometimes the very privilege that enabled these executives’ rise in the first place. Getting up early isn’t what made Tim Cook successful, and getting up late is not necessarily what’s holding you back.

Advertisement

Neither is any one part of the work habits of successful people. In fact, some of our best How I Work profiles are with successful people who get honest about their failures and flaws—and not just in that “aw shucks here’s what I learned” way. For example, we asked bestselling author Roxane Gay, “What everyday thing are you better at than everyone else? What’s your secret?” Her answer: “I am really good at missing deadlines. My secret to this is overcommitting to projects because of a profound inability to say no.” There, sincerely, is a real role model for you.

So listen to leading Marxist mouthpiece The Economist, and don’t let the titans of business convince you that if you just wake up two hours earlier, some day you’ll be rich like them. Everyone has to find their own path. Life is not a meritocracy. And the greatest successful people are the ones who don’t pose as demigods.

The annoying habits of highly effective people | The Economist

Ben WolfReally interesting read. Dude is on his high horse but still really solid analysis.

If I were a senator, I would not vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh.

These are words I write with no pleasure, but with deep sadness. Unlike many people who will read them with glee—as validating preexisting political, philosophical, or jurisprudential opposition to Kavanaugh’s nomination—I have no hostility to or particular fear of conservative jurisprudence. I have a long relationship with Kavanaugh, and I have always liked him. I have admired his career on the D.C. Circuit. I have spoken warmly of him. I have published him. I have vouched publicly for his character—more than once—and taken a fair bit of heat for doing so. I have also spent a substantial portion of my adult life defending the proposition that judicial nominees are entitled to a measure of decency from the Senate and that there should be norms of civility within a process that showed Kavanaugh none even before the current allegations arose.

[Read Caitlin Flanagan on why she believes Christine Blasey Ford]

This is an article I never imagined myself writing, that I never wanted to write, that I wish I could not write.

I am also keenly aware that rejecting Kavanaugh on the record currently before the Senate will set a dangerous precedent. The allegations against him remain unproven. They arose publicly late in the process and, by their nature, are not amenable to decisive factual rebuttal. It is a real possibility that Kavanaugh is telling the truth and that he has had his life turned upside down over a falsehood. Even assuming that Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations are entirely accurate, rejecting him on the current record could incentivize not merely other sexual-assault victims to come forward—which would be a salutary thing—but also other late-stage allegations of a non-falsifiable nature by people who are not acting in good faith. We are on a dangerous road, and the judicial confirmation wars are going to get a lot worse for our traveling down it.

Despite all of that, if I were a senator, I would vote against Kavanaugh’s confirmation. I would do it both because of Ford’s testimony and because of Kavanaugh’s. For reasons I will describe, I find her account more believable than his. I would also do it because whatever the truth of what happened in the summer of 1982, Thursday’s hearing left Kavanaugh nonviable as a justice.

[Read Deborah Copaken on facing her rapist ]

A few days before the hearing, I detailed on this site the advice I would give to Kavanaugh if he asked me. He should, I argued, withdraw from consideration for elevation unless able to defend himself to a high degree of factual certainty without attacking Ford. He should remain a nominee, I argued, only if his defense would be sufficiently convincing that it would meet what we might term the “no asterisks” standard—that is, that it would plausibly convince even people who vociferously disagree with his jurisprudential views that he could serve credibly as a justice. His defense needed to make it possible for a reasonable pro-choice woman to find it a legitimate and acceptable prospect, if not an attractive or appealing one, that he might sit on a case reconsidering Roe v. Wade.

Kavanaugh, needless to say, did not take my advice. He stayed in, and he delivered on Thursday, by way of defense, a howl of rage. He went on the attack not against Ford—for that we can be grateful—but against Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee and beyond. His opening statement was an unprecedentedly partisan outburst of emotion from a would-be justice. I do not begrudge him the emotion, even the anger. He has been through a kind of hell that would leave any person gasping for air. But I cannot condone the partisanship—which was raw, undisguised, naked, and conspiratorial—from someone who asks for public faith as a dispassionate and impartial judicial actor. His performance was wholly inconsistent with the conduct we should expect from a member of the judiciary.

Consider the judicial function as described by Kavanaugh himself at his first hearing. That Brett Kavanaugh described a “good judge [as] an umpire—a neutral and impartial arbiter who favors no litigant or policy.” That Brett Kavanaugh reminded us that “the Supreme Court must never be viewed as a partisan institution. The justices on the Supreme Court do not sit on opposite sides of an aisle. They do not caucus in separate rooms.”

[Read Judith Donath on the secret to Brett Kavanaugh’s specific appeal]

A very different Brett Kavanaugh showed up to Thursday’s hearing. This one accused the Democratic members of the committee of a “grotesque and coordinated character assassination,” saying that they had “replaced advice and consent with search and destroy.” After rightly criticizing “the behavior of several of the Democratic members of this committee at [his] hearing a few weeks ago [as] an embarrassment,” this Brett Kavanaugh veered off into full-throated conspiracy in a fashion that made entirely clear that he knew which room he caucused in:

When I did at least okay enough at the hearings that it looked like I might actually get confirmed, a new tactic was needed.

Some of you were lying in wait and had it ready. This first allegation was held in secret for weeks by a Democratic member of this committee, and by staff. It would be needed only if you couldn’t take me out on the merits.

When it was needed, this allegation was unleashed and publicly deployed over Dr. Ford’s wishes. And then—and then as no doubt was expected, if not planned—came a long series of false last-minute smears designed to scare me and drive me out of the process before any hearing occurred.

He went on: “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit, fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record, revenge on behalf of the Clintons, and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups.”

[Read Caitlin Flanagan on what’s changed since 1982]

As Charlie Sykes, a thoughtful conservative commentator sympathetic to Kavanaugh, put it on The Weekly Standard’s podcast Friday, “Even if you support Brett Kavanaugh … that was breathtaking as an abandonment of any pretense of having a judicial temperament.” Sykes went on: “It’s possible, I think, to have been angry, emotional, and passionate without crossing the lines that he crossed—assuming that there are any lines anymore.”

Kavanaugh blew across lines that I believe a justice still needs to hold.

The Brett Kavanaugh who showed up to Thursday’s hearing is a man I have never met, whom I have never even caught a glimpse of in 20 years of knowing the person who showed up to the first hearing. I dealt with Kavanaugh during the Starr investigation, which I covered for the Washington Post editorial page and about which I wrote a book. I dealt with him when he was in the White House counsel’s office and working on judicial nominations and post–September 11 legal matters. Since his confirmation to the D.C. Circuit, he has been a significant voice on a raft of issues I work on. In all of our interactions, he has been a consummate professional. The allegations against him shocked me very deeply, but not quite so deeply as did his presentation. It was not just an angry and aggressive version of the person I have known. It seemed like a different person altogether.

My cognitive dissonance at Kavanaugh’s performance Thursday is not important. What is important is the dissonance between the Kavanaugh of Thursday’s hearing and the judicial function. Can anyone seriously entertain the notion that a reasonable pro-choice woman would feel like her position could get a fair shake before a Justice Kavanaugh? Can anyone seriously entertain the notion that a reasonable Democrat, or a reasonable liberal of any kind, would after that performance consider him a fair arbiter in, say, a case about partisan gerrymandering, voter identification, or anything else with a strong partisan valence? Quite apart from the merits of Ford’s allegations against him, Kavanaugh’s display on Thursday—if I were a senator voting on confirmation—would preclude my support.

[Read Adam Serwer on what Mark Judge’s absence reveals ]