[Conflict of interest notice: I’ve volunteered for both private and public charities, but more often private. I received a small amount of money for work done for a private charity ten years ago. Some of the private charities have been partially funded by billionaires.]

From Vox: The Case Against Billionaire Philanthropy. It joins The Guardian, Truthout, Dissent Magazine, CityLab, and a host of other people and organizations arguing that rich people giving to charity is now a big problem.

I’m against this. I understand concern about the growing power of the very rich. But I worry the movement against billionaire charity is on track to damage charity a whole lot more than it damages billionaires. Eleven points:

1. Is criticizing billionaire philanthropy a good way to protest billionaires having too much power in society?

Which got more criticism? Mark Zuckerberg giving $100 million to help low-income students? Or Mark Zuckerberg buying a $59 million dollar mansion in Lake Tahoe? Obviously it’s the low-income students. I’ve heard people criticizing Zuckerberg’s donation constantly for years, and I didn’t even know he had a $59 million Lake Tahoe mansion until I googled “things mark zuckerberg has spent ridiculous amounts of money on” in the process of writing this paragraph.

Which got more negative press? Jeff Bezos donating $2 billion for preschools for underprivileged children? Or Jeff Bezos spending $2 billion on whatever is going to come up when I Google “things jeff bezos has spent ridiculous amounts of money on?”.

Billionaires respond to incentives like everyone else. If donating to charity earns them negative publicity, and buying a private yacht earns them glowing articles about how cool their yacht is, they’re more likely to buy the yacht.

Journalists and intellectuals who criticize billionaires’ philanthropy but not their yachts, or who spend much more energy criticizing philanthropy than yachts, probably aren’t doing much to promote a world without billionaires. But they’re doing a lot to promote a world where billionaires just buy yachts instead of giving to charity.

2. If attacks on billionaire philanthropy decrease billionaires’ donations, is that acceptable collateral damage in the fight against inequality?

That depends on your values. But for most people’s values, the answer is no.

Nobody knows exactly how many lives the Gates Foundation has saved. The Guardian says it’s some appreciable fraction of the 122 million lives saved in general from progress fighting infectious diseases over the last few decade. This article says Gates has saved seven million people through his vaccination campaign alone, provided another seven million with antiretroviral treatment (usually life-saving), “tested and treated” twelve million people for tuberculosis (often fatal, but there’s a big difference between testing and treatment), and been responsible for a big part of the seven million lives saved from malaria. I expect these numbers are inflated, but even by conservative estimates the Gates Foundation may have saved ten million people.

Suppose Jeff Bezos is watching how people treat Bill Gates, and changes his own behavior accordingly. Maybe in the best possible world, when people attack Gates’ donations, Bezos learns that people don’t like ruthless billionaires, decides not to be ruthless like Gates was, and agrees to Bernie Sanders’ demand that he increase his employees’ pay by $4/hour. But Bezos also learns people criticize billionaires’ philanthropy especially intensely, decides not to be charitable like Gates was, and so ten million people die. You’ve just bought an extra $4/hour for warehouse workers, at the cost of ten million lives.

In my moral system, this means billionaire philanthropy is not acceptable collateral damage in the war against inequality. Even if for some reason you believe that criticizing billionaire philanthropy is a higher-impact way to fight inequality than criticizing billionaires’ yachts, you should stick to criticizing the yachts.

3. Do billionaires really get negative reactions from donating? Didn’t I hear that they get fawning praise and total absence of skepticism?

Vox quotes Rob Reich (not the same person as the former Labor Secretary), a prominent critic of bilionaire philanthropy. Reich writes that billionaires “ask everyone involved to bend over in gratitude for her benevolence and genius in sprinkling around some social benefits” and so we need to “stop being merely grateful to donors and instead direct our skepticism and scrutiny at their activities”.

How much gratitude vs. scrutiny do billionaire donors get?

The three most publicized recent billionaire donations were Zuckerberg to Newark schools, Bezos to preschools, and Gates to malaria. I looked at Twitter to examine how much fawning vs. scrutiny people were giving each. Specifically, I searched “Zuckerberg Newark”, “Bezos preschool” and “Gates malaria”. I then coded the first twenty-five tweets on the Top Tweets page for each as positive, negative, or neutral. I ignored mismatches that weren’t about the donations, and also ignored the genre of people using Zuckerberg’s donation as a way of criticizing Cory Booker (which was more than half of the Zuckerberg tweets).

Searching “Zuckerberg Newark”, I counted 2 positive tweets, 4 neutral tweets, and 19 negative tweets:

Searching “Bezos preschool”, I counted 5 positive, 7 neutral, and 14 negative tweets:

Searching “Gates malaria”, I counted 15 positive, 4 neutral, and 6 negative.

The same is true of Google search. I examined the top ten search results for each donation, with broadly similar results: mostly negative for Zuckerberg and Bezos, mostly positive for Gates.

But when people talk about “billionaire philanthropy” in general, they tend to elide this distinction and focus on the bad. A twitter search for “billionaire philanthropy” produced 2 positive, 3 neutral, and 20 negative tweets, more negative than for any individual donation. A Google search for “billionaire philanthropy”, and the top ten results contained 1 positive article, 5 neutral articles, and 4 negative articles.

Although some donors like Bill Gates are generally liked, others, like Zuckerberg and Bezos, are met with widespread distrust. This might be because Gates has worked harder to target his donations well, or because he made his money a long time ago and nobody is too angry about his business practices anymore. But on a broader scale, the media and social media consensus is already parroting anti-billionaire-philanthropy talking points.

If everyone were unreflectively praising philanthropic billionaires, there would be a strong case for encouraging skepticism. But if most responses to billionaire philanthropy are negative, we should worry more about the consequences of the backlash.

4. Is it a problem that billionaire philanthropy is unaccountable to public democratic institutions? Should we make billionaires pay that money as taxes instead, so the public can decide how it gets spent?

From Dissent:

Big philanthropy is overdue for reform. The goal should be to reduce its leverage in civil society and public policymaking while increasing government revenue. Some possible changes seem obvious: don’t allow administrative expenses to count toward the 5 percent minimum payout, increase the excise tax on net investment income, eliminate the tax exemption for foundations with assets over a certain size, and replace the charity tax deduction with a tax credit available to everyone (for example, all donors could subtract 15 percent of the total value of their charitable contributions from their tax bills). In addition, strict IRS oversight of big philanthropy—especially all the “educating” that looks so much like lobbying and campaigning — is crucial […]

Private foundations fall into the IRS’s wide-open category of tax-exempt organizations, which includes charitable, educational, religious, scientific, literary, and other groups. When the creator of a mega-foundation says, ‘I can do what I want because it’s my money,’ he or she is wrong. A substantial portion of the wealth — 35 percent or more, depending on tax rates — has been diverted from the public treasury, where voters would have determined its use.

This makes the same argument as some of the other articles linked above. Since billionaires have complete control over their own money, they are helping society the way they want, not the way the voters and democratically-elected-officials want. This threatens democracy. We can solve this by increasing taxes on philanthropy, so that the money billionaires might have spent on charity flows back to the public purse instead.

Two of the billionaires whose philanthropy I most respect, Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna, have done a lot of work on the criminal justice reform. The organizations they fund determined that many innocent people are languishing in jail for months because they don’t have enough money to pay bail; others are pleading guilty to crimes they didn’t commit because they have to get out of jail in time to get to work or care for their children, even if it gives them a criminal record. They funded a short-term effort to help these people afford bail, and a long-term effort to reform the bail system. One of the charities they donate to, The Bronx Freedom Fund, found that 92% of suspects without bail assistance will plead guilty and get a criminal record. But if given enough bail assistance to make it to trial, over half would have all charges dropped. This is exactly the kind of fighting-mass-incarceration and stopping-the-cycle-of-poverty work everyone says we need, and it works really well. I have donated to this charity myself, but obviously I can only give a tiny fraction of what Moskovitz and Tuna manage.

If Moskovitz and Tuna’s money instead flowed to the government, would it accomplish the same goal in some kind of more democratic, more publically-guided way? No. It would go to locking these people up, paying for more prosecutors to trick them into pleading guilty, more prison guards to abuse and harass them. The government already spends $100 billion – seven times Tuna and Moskovitz’s combined fortunes – on maintaining the carceral state each year. This utterly dwarfs any trickle of money it spends on undoing the harms of the carceral state, even supposing such a trickle exists. Kicking Tuna and Moskovitz out of the picture isn’t going to cause bail reform to happen in some civically-responsible manner. It’s just going to ensure that all the money goes to making the problem worse, instead of the overwhelming majority going to making the problem worse but a tiny amount also going to making it better.

Or take one of M&T’s other major causes, animal welfare. Until last year, California factory farms kept animals in cages so small that they could not lie down or stretch their limbs, for their entire lives. Moskovitz and Tuna funded a ballot measure which successfully banned this kind of confinement. It reduced the suffering of hundreds of millions of farm animals and is one of the biggest victories against animal cruelty in history.

If their money had gone to the government instead, would it have led to some even better democratic stakeholder-involving animal welfare victory? No. It would have joined the $20 billion – again, more than T&M’s combined fortunes – that the government spends to subsidize factory farming each year. Or it might have gone to the enforcement of ag-gag laws – laws that jail anyone who publicly reports on the conditions in factory farms (in flagrant violation of the First Amendment) because factory farms don’t want people to realize how they treat their animals, and have good enough lobbyists that they can just make the government imprison anyone who talks about it.

George Soros donated/invested $500 million to help migrants and refugees. If he had given it to the government instead, would it have gone to some more grassroots migrant-helping effort?

No. It would have gone to building a border wall, building more camps to lock up migrants, more cages to separate refugee children from their families. Maybe some tiny trickle, a fraction of a percent, would have gone to a publicly-funded pro-refugee effort, but not nearly as much as would have gone to hurting refugees.

The idea that we should divert money from freeing the incarcerated, saving animals, and reuniting families – to instead expanding incarceration, torturing animals, and separating families – seems monstrous to me, even (especially?) when cloaked in communitarian language.

5. Those are some emotionally salient examples, but doesn’t the government also do a lot of good things?

Yes, but the US government is not a charity. Even when it’s doing good things, it’s not efficiently allocating its money according to some concept of what does the most good.

Bill Gates saved ten million lives by asking a lot of smart people what causes were most important. They said it was global health and development causes like treating malaria and tuberculosis. So Gates allocated most of his fortune to those causes. Gates and people like him are such a large fraction of philanthropic billionaires that by my calculations these causes get about 25% of billionaire philanthropic spending.

The US government also does some great work in those areas. But it spends about 0.9% of its budget on them. As a result, one dollar given to a billionaire foundation is more likely to go to a very poor person than the same dollar given to the US government, and much more likely to help that person in some transformative way like saving their life or lifting them out of poverty.

But this is still too kind to the US government. It’s understandable that they may want to focus on highways in Iowa instead of epidemics in Sudan. Yet even on issues vital for the safety of the American people, the government tends to fail in surprising ways.

How much money does the US government spend fighting climate change? This 538 article explains why this is a hard question, but it tries to give the best answer it can:

The 2018 GAO report found that, while the Office of Management and Budget has reported that the federal government spent more than $154 billion on climate-change-related activities since 1993, much of that number is likely not being used to directly address climate change or its risks. Many of the projects reported as “climate-change-related activities” are only secondarily about climate change.

For instance, the U.S. nuclear energy program predates serious concerns about climate change and would likely exist in its current form even if it did not produce fewer greenhouse-gases than some other forms of energy production, like burning coal. But the nuclear program’s budget is counted as climate spending. All told, when the GAO evaluated six agencies that report their climate spending to the OMB, it found that 94 percent of the money was going to programs that weren’t primarily focused on climate change — things like nuclear energy. The money marked as climate spending wasn’t going to new initiatives. Instead, “it’s a bunch of related things we were already doing,” Gomez told me. Numbers like that $154 billion total can be used as political props, but that kind of accounting isn’t much good for understanding what the government is actually doing about climate change.

$154 billion * 6% primarily focused on climate change / 25 years = $369 million per year. It might be higher than the 25-year average now, because of increasing awareness of climate change, but it might also be lower, because Trump. I have low confidence in the exact estimate but I think this is the right order of magnitude.

In 2017, the foundation of billionaire William Hewlett (think Hewlett-Packard) pledged $600 million to fight climate change. One gift by one guy was almost twice the entire US federal government’s yearly spending on climate issues.

This isn’t some parable on how mighty billionaires have become or how much power they have accrued. Mr. Hewlett’s budget is still only one ten-thousandth the size of the government’s. It’s not that he’s anywhere near government-sized, it’s just that the government doesn’t care at all, so a billionaire can outspend them if he cares a little.

Thanks to Hewlett and a few other people like him, I calculate that about 3% of billionaire philanthropy goes to climate change, compared to 0.01% of the federal budget.

Not every billionaire spends their money on global health or fighting climate change. There’s a lot of criticism of billionaires who “waste” their donations on already-well-endowed colleges and performing arts centers, and I agree we should push them to think harder about their choices. But charity, like investing, is in what Nassim Taleb calls Extremistan – almost all the value lies in getting it very right once or twice. An investment fund that picks a hundred duds plus 2004 Facebook is still an amazing investment fund. A form of philanthropy that produces a hundred duds plus Bill Gates (and Dustin Moskovitz, and Cari Tuna, and Warren Buffett, and Ben Delo, and…) is still an amazing benefit to the world.

I wish I could give a more detailed breakdown of how philanthropists vs. the government spend their money, but I can’t find the data. Considerations like the above make me think that philanthropists in general are better at focusing on the most important causes.

I think this also makes intuitive sense. Charities are capable of laserlike focus on the most important and desperate causes. Give their money to the government instead, and it will get spent on fighter jets, bombing brown kids in Afghanistan, shooting brown kids in Chicago, subsidizing coal companies, jailing anyone who tries to dress hair withoug a hairdresser license, and paying farmers not to grow crops – and then, at the end of all that, maybe have a tiny bit left over to spend on the desperately important problems that affect the most vulnerable people.

Governments are a useful type of organization that should exist. I don’t want to get rid of them. But right now we’re thinking on the margin, and on the margin an extra dollar given to a charity will do more good than that same dollar given to the government.

6. The point of democracy isn’t that it’s always right, the point is that it respects the popular will. Regardless of whether the popular will is good or bad, don’t powerful private foundations violate it?

Reich again:

The modern foundation is an institutional oddity in a democracy.

In a democracy, officials responsible for public policy must stand for election. Don’t like your representatives’ policy views? Vote against them in the next election. This is the accountability logic internal to democracy — responsiveness to citizens. It does not always work this way, but the logic has some real force.

But foundations have no electoral accountability. Don’t like what the Gates Foundation did with its $3.4 billion in 2011 grants ($9.3 million each day of the year), or what it has done with $25 billion in grants since its inception in 1994? Tough, there’s no way to vote out the Gateses.

I realize there’s some very weak sense in which the US government represents me. But it’s really weak. Really, really weak. When I turn on the news and see the latest from the US government, I rarely find myself thinking “Ah, yes, I see they’re representing me very well today.”

Paradoxically, most people feel the same way. Congress has an approval rating of 19% right now. According to PolitiFact, most voters have more positive feelings towards hemorrhoids, herpes, and traffic jams than towards Congress. How does a body made entirely of people chosen by the public end up loathed by the public? I agree this is puzzling, but for now let’s just admit it’s happening.

Bill Gates has an approval rating of 76%, literally higher than God. Even Mark Zuckerberg has an approval rating of 24%, below God but still well above Congress. In a Georgetown university survey, the US public stated they had more confidence in philanthropy than in Congress, the court system, state governments, or local governments; Democrats (though not Republicans) also preferred philanthropy to the executive branch.

When I see philanthropists try to save lives and cure diseases, I feel like there’s someone powerful out there who shares my values and represents me. Even when Elon Musk spends his money on awesome rockets, I feel that way, because there’s a part of me that would totally fritter away any fortune I got on awesome rockets. I’ve never gotten that feeling when I watch Congress. When I watch Congress, I feel a scary unbridgeable gulf between me and anybody who matters. And the polls suggest a lot of people agree with me.

In what sense does it reflect the will of the people to transfer power and money from people and causes the public like and trust, to people and causes who the public hate and distrust? Why is it democratic to take money from someone more popular than God, and give it to a group of people more hated than hemorrhoids?

If the people want more money to be spent by private philanthropists instead of Congress, and they use the democratic process to produce a legal regime and tax system that favors private philanthropy, their will is being represented.

7. Shouldn’t people who disagree with the government’s priorities fight to change the government, not go off and do their own thing?

Suppose I was donating money to feed starving children, and it was going well, and lots of starving children were getting fed. Then you come along and say “No, you should give that money to the Church of Scientology instead”.

I say “No, I hate Scientology.”

You: “Ah, but you can always try to reform Scientology. And maybe in a hundred years, it won’t be racist anymore, and instead it will try to help starving children.”

Me: “So you’re saying that I should work tirelessly to reform Scientology, and then in a hundred years when they’re good, I should give them my money?”

You: “Oh no, you have to give them all your money now. But while you’re giving them all your money, you can also work toward reforming them.”

Why would I do this? Why would it even cross anybody’s mind that they should do this? I am not saying that the government is evil in the same way as Scientology. But I think the fundamental dynamic – should you give your money to a cause you think is good, or to an organization you think is bad while trying to reform it? – is the same in both cases.

Also, do you realize how monumental a task “reform the government” is? There are thousands of well-funded organizations full of highly-talented people trying to reform the government at any given moment, and they’re all locked in a tug-of-war death match reminiscent of that one church in Jerusalem where nobody has been able to remove a ladder for three hundred years. This isn’t to say no reform will ever happen – it’s happened before, it will surely happen again, and it’s a valuable thing to work towards. Just don’t hold up any attempts to ease the suffering of the less fortunate by demanding they wait until every necessary reform is accomplished.

Also, a lot of billionaires are trying to reform the government (eg George Soros, Charles Koch) and that makes the anti-billionaire-philanthropy crowd even angrier than when they just help poor people.

8. Is billionaire philanthropy getting too powerful? Should we be terrified by the share of resources now controlled by unaccountable charitable foundations?

From Dissent:

Right now, big philanthropy in the United States is booming. Major sources of growth have been the wealth generated by high-tech industries and the expanding global market. In September 2013 there were sixty-seven private grant-making foundations with assets over $1 billion. The Rockefeller Foundation, once the wealthiest, now ranks fifteenth; the Carnegie Corporation ranks twentieth (Foundation Center). Mega-foundations are more powerful now than in the twentieth century—not only because of their greater number, but also because of the context in which they operate: dwindling government resources for public goods and services, the drive to privatize what remains of the public sector, an increased concentration of wealth in the top 1 percent, celebration of the rich for nothing more than their accumulation of money, virtually unlimited private financing of political campaigns, and the unenforced (perhaps unenforceable) separation of legal educational activities from illegal lobbying and political campaigning. In this context, big philanthropy has too much clout.

The yearly federal budget is $4 trillion. The yearly billionaire philanthropy budget is about $10 billion, 400 times smaller.

For context, the California government recently admitted that its high-speed rail project was going to be $40 billion over budget (it may also never get built). The cost overruns alone on a single state government project equal four years of all the charity spending by all the billionaires in the country.

Compared to government spending, Big Philanthropy is a rounding error. If the whole field were taxed completely out of existence, all its money wouldn’t serve to cover the cost overruns on a single train line.

If this seems surprising, I think that in itself is evidence that the money is being well-spent. Billionaire philanthropy isn’t powerful, at least not compared to anything else. It just has enough accomplishments to attract attention. Destroying it wouldn’t enrich anyone else to any useful degree, or neutralize some threatening power base. It would just destroy something really good.

9. Does billionaire philanthropy threaten pluralism?

From Reich’s Vox interview again:

I am, by contrast, a pluralist; I want to champion the decentralization of what would otherwise be a majoritarian decision-making structure for the spending of tax dollars to produce various forms of social benefits. And I think part of what makes ordinary charitable giving a good thing is the conversion of every individual’s idiosyncratic, eccentric preferences into some civil society-facing project that by extension produces a diverse, pluralistic civil society, which is good for democracy.

I am having trouble following the argument. We need pluralism and decentralization. Therefore, we should ban anyone from doing their own thing, and instead force them to go through a single giant organization?

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) sponsors research into mental health uses of psychedelic drugs. You might have heard of them in the context of their study of MDMA (Ecstasy) for PTSD being “astoundingly” successful. They’re on track to get MDMA FDA-approved and potentially inaugurate a new era in psychiatry. This is one of those 1000x opportunities that effective altruists dream of.

The government hasn’t given this a drop of funding, because its official position is that Drugs Are Bad. MAPS writes:

Every dollar has come from private donors committed to our mission. The pharmaceutical industry and federal government have not yet supported our work, so the continued expansion of psychedelic research still relies on the generosity of individual donors and foundations.

Most of the funding for their MDMA trial came from the foundation of billionaire Robert Mercer. Because there were actors other than the government with enough money to fund things they believed in, we were able to get some great work done even though it wasn’t the sort of thing the government would support.

Or: in 2001, under pressure from Christian conservatives, President Bush banned federal funding for stem cell research. Stem cell scientists began leaving the US or going into other area of work. The field survived thanks to billionaires stepping up to provide the support the government wouldn’t – especially insurance billionaire Eli Broad, who gave $25 million to the cause, and eBay billionaire Pierre Omidyar, who sponsored a California ballot initiative to redirect state funding to cover the gap. Time after time, the government has stopped supporting things for bad reasons, and we’ve been lucky that we didn’t bulldoze over the rest of civil society and prevent anyone else from having enough power to help.

Or: despite controversy over “government funding of Planned Parenthood”, political considerations have seriously limited the amount of funding the US government can give contraceptive research. It was multimillionaire heiress Katharine McCormick who funded the research into what would become the first combined oral contraceptive pill. More recently, it was Warren Buffett who funded RU-486 and the IUD. Together with similar work by the Rockefeller and Ford foundations, these have prevented millions of unwanted pregnancies.

When there are hundreds of different actors who can pursue their own projects, we get hundreds of genuinely different projects, some of which go great. If we restrict individuals from pursuing their own projects, and everything has to be funded by a single organization with a single agenda, we reduce the possibilities for progress to a monoculture, vulnerable to any minor flaw in the hegemon’s priorities.

In other cases, billionaires and government agencies are performing the same tasks in parallel. For example, both Bill Gates and the CDC are fighting infectious diseases in the developing world; both Elon Musk and NASA are working on space exploration.

Both groups bring different institutional cultures and priorities to the fight. The Gates Foundation is not run along exactly the same lines as the CDC; SpaceX has a different institutional culture from NASA. When one organization gets stuck in a dead-end, or isn’t up to a certain task, there’s a chance that the other will have the right structure to succeed. Some of this is random variation, some of it is structural differences between the public and private sector. I think it’s really healthy to have multiple diverse institutions trying to pursue the same goal. Robustness against obvious failures like “the government just banned all stem cell research” is just a special case of this principle.

I am using Reich as a foil, but in other places he seems to agree with this. At the end of this article he writes about “the case for foundations”, and says:

I believe there is a case for foundations that renders them not merely consistent with democracy but supportive of it.

First, foundations can help to diminish government orthodoxy by decentralizing the definition and distribution of public goods. Call this the pluralism argument. Second, foundations can operate on a longer time horizon than can businesses in the marketplace and elected officials in public institutions, taking risks in social policy experimentation and innovation that we should not routinely expect to see in the commercial or state sector. Call this the discovery argument.

I agree with all of this (and am now confused about to what degree Reich and I disagree at all), but I take this as meaning that private philanthropy, far from threatening pluralism, exemplifies it.

10. Aren’t the failures of government just due to Donald Trump or people like him? Won’t they hopefully get better soon?

Billionaires sometimes do a better job than the government at funding things like stem cells and the fight against climate change. But this is because of bad decisions by bad government officials. Obama overturned the stem cell ban; hopefully the next Democratic president will fix the climate funding situation. Does this make it unfair of me to compare the government vs. billionaires on this axis when there’s a hopefully-temporary reason the government is as bad as it is?

No. My whole point is that if you force everyone to centralize all money and power into one giant organization with a single point of failure, then when that single point of failure fails, you’re really screwed.

Remember that when people say decisions should be made through democratic institutions, in practice that often means the decisions get made by Donald Trump, who was democratically elected. At the risk of going Civics 101, we’re not supposed to be a pure democracy. We’re a complicated system of checks and balances that uses democracy in some of its components. But we deliberately have other, less democratic components to deal with the situations when the demos f@#ks up. The demos seems to be f@#king up pretty regularly these days and I’m glad we still have those other institutions.

11. So you’re saying these considerations about pluralism and representation and so on justify billionaire philanthropy?

I’m bringing up these considerations as counterarguments to some of the things opponents say. But I think they’re the wrong thing to focus on.

The Gates Foundation plausibly saved ten million lives. Moskovitz and Tuna saved a hundred million animals from excruciatingly painful conditions. Norman Borlaug’s agricultural research (supported by the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation) plausibly saved one billion people.

These accomplishments – and other similar victories over famine, disease, and misery – are plausibly the best things that have happened in the past century. All the hot-button issues we usually care about pale before them. Think of how valuable one person’s life is – a friend, a family member, yourself – then try multiplying that by ten million or a billion or whatever, it doesn’t matter, our minds can’t represent those kinds of quantities anyway. Anything that makes these kinds of victories even a little less likely would be a disaster for human welfare.

The main argument against against billionaire philanthropy is that the lives and welfare of millions of the neediest people matter more than whatever point you can make by risking them. Criticize the existence of billionaires in general, criticize billionaires’ spending on yachts or mansions. But if you only criticize billionaires when they’re trying to save lives, you risk collateral damage to everything we care about.

Reuters/Mike Segar

Reuters/Mike Segar

Marvel Studios

Marvel Studios

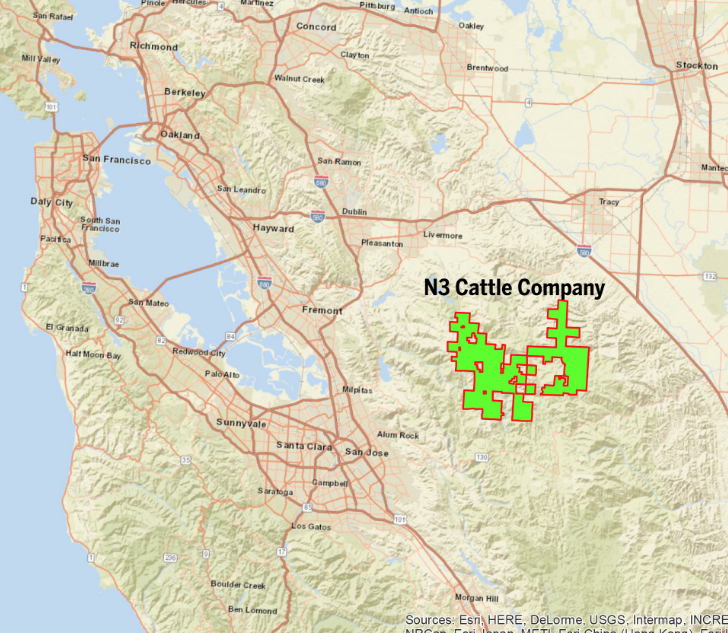

You might say that it would be impossible to put together a piece of land near San Jose that is large enough to house more people than San Francisco, and at a much lower density. Where would one find the land?

You might say that it would be impossible to put together a piece of land near San Jose that is large enough to house more people than San Francisco, and at a much lower density. Where would one find the land? That’s right, the N3 Cattle Company is currently for sale, and it is much larger than San Francisco.

That’s right, the N3 Cattle Company is currently for sale, and it is much larger than San Francisco.