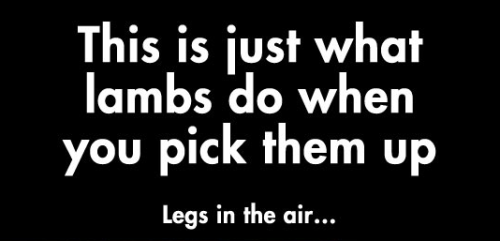

According to one of my more observant friends, I am not a human but a robot with a pretty solid sense of how humans behave. She’s gathered some compelling evidence: I almost never experience thirst or seek out water, and when I do, I’ll make a grand show of it to keep up the act. I side with Tracy Jordan here: water is nothing more than “clear bathtub juice.”

There’s also the laughter issue: I don’t really laugh. I find things funny, but I’m rarely moved to spontaneous vocalizations of glee. Instead, I smile and offer a nasally “HEH,” a guttural “heh heh,” or emphatic nose exhale when I want to show someone I recognize what they said was a joke, and that it was nice. This can be off-putting. Even when something strikes me as truly hilarious—that dog that looks more like John Travolta than John Travolta, for example—I don’t laugh, or even smile.

Something happens when you grow up, as the tragedy of existence sets in. Human babies laugh about 300 times a day, while human adults only laugh 20 times. Maria, of neither demographic, laughs two times daily, three times max, but only if she watches that scene in It’s Always Sunny when Danny DeVito’s character, naked and sweaty, breaks out of a couch he was sewn into.

“People learn to put roadblocks in the way of their laughter,” offered Enda Junkins, a national laughter therapist/mogul, when I called her after Googling “laugh feel better therapy i'm depressed science?” I was interested in learning to laugh like my human friends, yes—but my desire to experience the transformative power of routine laughter was far more powerful.“The more you practice laughing, the fewer controls you have on it,” she told me.

On her website, Laughter Therapy Enterprises, Junkins provides several tips for laughing more and breaking down some of the roadblocks. Suggestions include: “Wear hats that make you laugh,” “Buy and listen daily to a tape of laughter, a laugh box, or a laughing toy,” “Laugh with your co-workers for a few minutes for no real reason at all,” and the best one, “Wear light-hearted, temporary tattoos that help you cope.”

She advises laughing for five uninterrupted minutes every day. I vowed to do ten minutes a day for two weeks because I wanted double the benefits.

My first morning on a strict laughter regimen, I began with exercises I found on the Internet. I held an imaginary cellphone to my ear and laughed into it for two minutes, and then transitioned to a move where I spread my arms, looked up at the ceiling, twirled, and laughed heartily for three. My fake laugh was unconvincing—the sounds were labored and maniacal, like a mall Santa who has had a long day—but I didn’t need to convince anyone. After the exercises, I felt a lightness in the top of my head that resembled joy.

![]()

There are two types of laughter: fake and genuine. But in the laughter therapy universe, a laugh is a laugh. Endorphins don’t care whether you’re laughing because a joke was funny or if you’re just imitating the sounds; if you go through a specific set of physical processes—open mouth, smile formation, “ha” noises—you feel better. According to several studies, laughter minimizes chronic pain, lowers blood pressure, improves alertness, helps with insomnia, and combats depression. In a 2010 Times article, psychoanalyst Rob Marchesani referred to laughter as “natural Xanax.”

I wanted some of that natural-Xanax-goodness, and not just because I yearned to laugh with the ease and whimsy of a likeable person. I craved more joy. I wanted to feel the way women are meant to feel when they eat 100-calorie yogurts: bubbly, free, sensual, ecstatic. Yet when I eat yogurt that pleases me, whether it's low-cal or even full-fat, I’m still a chronically depressed woman who relies on medication to live, a woman never too far from gloom. If I believed in the power of chemicals to do good things in messed-up brains, I figured, I should believe in the power of laughter, which, it turns out, is chemical.

Each day on my laughter diet began the same as a regular day: Wake up. Eat whatever half of sandwich is left on my pillow from the night before. Gear up emotionally to start working in bed, as a freelancer does. Grow saddened by the long stretch of day ahead, so full of nowhere-to-be and children’s gummy vitamins and reloading Twitter.

But on these mornings, when the prospect of existence antagonized and nagged at me, I fought back. I put on my novelty sailor cap (an impulse purchase from Croatia that is now the only thing I love), played a 12-hour laugh track reel, and strolled around my room, laughing, listening to laughing, and tipping my sailor cap at imaginary friends on the streets of Bushwick. Five minutes were enough to neutralize my mood. At nights, I’d repeat the routine, swapping a striped onesie for the sailor cap and subbing Broad City for the laugh track.

A fun feature of my apartment is that the M train goes through it. One night, the sound and rumbling woke me, even though I was three Advil PMs and two long-expired beers deep. I almost committed to fury, my go-to state, but then decided to try something different. “HA HA HA, HO HO HO, HEE HEE HEE,” I howled, making sure to engage my stomach, chest, and head with the techniques I’d learned on YouTube, the people’s university.

I finished laughing and the rumbling was gone. As the M is a sporadically-running trash train, I savored a luxurious 30-minute window to drift back asleep.

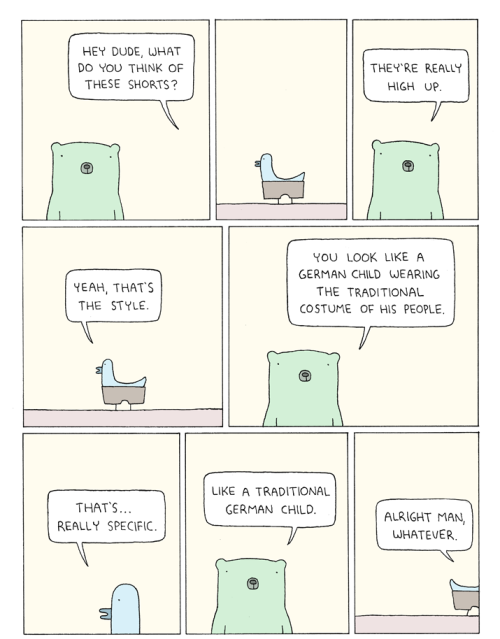

![]()

‘Laughter yoga’ is the combination of words that gives me the most dread. “Yoga” because I’ve never been able to touch my toes, privately or in front a group of skinny people, and “laughter” because being asked to laugh with strangers for a whole hour evokes the trauma of attending college improv shows. As I made my way to a free midtown laugh clinic, I worried that the group would find me out as a joyless loser who couldn’t even fake laugh like a real human.

There were five of us; everyone but me was a laughter yoga veteran. Two of them—short, jovial women in their late sixties—took off their shoes, so I did too. I smiled at everyone like smiling was a thing I always did.

Vishwa Prakash, our jovial instructor, began the class with “laughing introductions”: weaving in and out of each other, laughing hysterically and hugging each person we “met.” We then breezed through a series of exercises where we acted out goofy scenarios, again, laughing nonstop. We sprayed unwieldy hoses. We rode unwieldy motorcycles. We flossed our teeth. We flossed our brains. We were babies. We were monkeys. Between each laugh-experiment, we chanted the refrain— “HO, HO, HA, HA, HA” set to the motions of clap, clap, chicken flap, chicken flap, chicken flap —as we assembled back into a circle. Then, we’d cheer: “Very good, very good, YAYYY!!” before Vishwa explained the next move—whether singing “Deck the Halls” using only “Ha!” sounds, or convincing a police officer, in our most impassioned gibberish, that we had been wrongfully pulled over.

“Grabdly greeky ta ta baja hahahahaha,” I explained to a young Albanian woman as she belly-laughed. I waved my arms frantically, pointing to an imaginary traffic sign and making begging gestures with hands. “Hahahaha fla bee fla fla trun tak!”

It’s incredible how quickly you can adjust to your nightmare and even start to enjoy it. I guess this is my life now became my mentality after only five minutes. Laughter yoga was like improv comedy, but better, because it was improv’s total inverse: an abundance of laughter, yet zero pressure to be funny.

By the end of the hour my throat was dry and my cheeks ached. I don’t think I real-laughed once, as the others seemed to, but no one cared, especially not me. I was buzzing.

![]()

In 1900, French philosopher Henri Bergson published Le Rire, a book that explores the sociological significance of laughter. Bergson posits that for a person to laugh at a joke or a man who just slipped on a banana peel, that person must maintain a certain level of detachment from the seriousness of the subject’s situation. As in, the laugher doesn’t know the man who slipped, or that his girlfriend just broke up with him via Snapchat, compounding an all-around awful start to 2015.

Let’s forget about the man and look inward. Could the reverse work? To laugh at oneself or by oneself, then could that detach oneself from the seriousness of one’s own situation?

Yes. 100%. And that is an incredible tool to have in your Depression Toolbox.

“Laughter doesn’t change the facts; it changes how you relate to those facts,” Junkins told me. “It moves the challenges out of your face.”

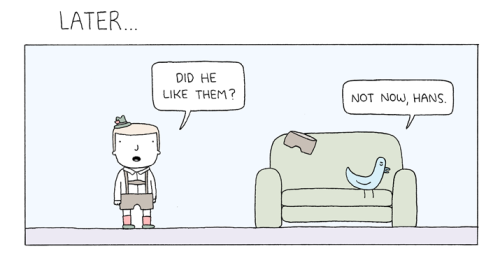

One morning towards the end of the second week, I woke feeling especially sullen. After peeling my iPhone off of my sweaty thigh, an email told me I didn’t get the job I’d applied for, a blow made worse by having just spent $100 on several business blouses (my name for shirts that don’t have text on them).

My roommate was in a slump, too. New York is awful, we agreed, talking on the couch, egging each other on, yearning for Vitamixes we’d never afford, cursing the M train. But soon I had to excuse myself to laugh. My morning laughter exercises had become so routine, like coffee or self-loathing, that I couldn’t wait too long to do it. I chuckled off into my bedroom, closed the door, and spread my arms wide to open up my chest. The laughter still wasn’t organic—I hadn’t gotten better at human laughing, like I’d hoped—but the lightness crept into my chest and the buzz crept into my head. The high came quicker and easier.

The rest of my day felt relatively sunny. Junkins speaks on laughter around the country, and her favorite subject is ‘Hattitude:’ how goofy hats and clothes can transform your mood. Embracing this ethos, I slipped on my ankle-length, Philadelphia Phillies maxi dress over leggings and a turtleneck and laughed to myself on the subway, as I headed towards the café I reappropriate as my office. The magic of laughing alone for no reason, or prompted by a group of ladies spraying imaginary hoses at you, is that it weirds you out so quickly—being such an abrupt departure from the normal—that you forget to worry about anything real.

“Nothing changes a mood faster than laughter,” a woman in my class had said when we sat in our closing circle, each of us hoping no one traced the foot smells back to us personally.

I play a laugh track when I work now, pretending I’m on The Suite Life of Zach and Cody, a world of fun hijinks and miscommunications. Realized I forgot to take my birth control last night? Laugh track surrounds me. Picked my lip until it bled? Laugh track plays right through that. LOLz all around.

There are several activities I know feel good but don’t always find the time or chutzpah to do. Run. Exfoliate. Change my sheets. Change my pants. With laughter and ‘hattitude’ and exercised silliness, I vow to take the time, every day, to separate myself from the severity of aliveness. All it takes is a robot laugh, a real laugh, or even a sailor cap to experience that quick hit of release.

Maria Yagoda is a writer living in New York who aspires to own several dogs with underbites.

1 Comments

In the fall of 1997 I arrived to New York University as a college freshman with two priorities. The first: to waste my parents’ money on a theater education. The second: to get drunk.

In the fall of 1997 I arrived to New York University as a college freshman with two priorities. The first: to waste my parents’ money on a theater education. The second: to get drunk. From last week, but maybe you missed it, Hairpin pal

From last week, but maybe you missed it, Hairpin pal  Australia's Philip Island Penguin Foundation has put up a call for

Australia's Philip Island Penguin Foundation has put up a call for

At the Smithsonian Magazine, Jessica Gross

At the Smithsonian Magazine, Jessica Gross