| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | May 1st, 2015 | next | |

|

May 1st, 2015: Hey guess what! A bunch of my discontinued shirt designs are now RE-CONTINUED, thanks to a new site called T Shirt Diplomacy, which also has... aliens designing shirts too? And friends! Anyway, c-c-check it out :0 – Ryan | |||

Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

i am ready for "ryanorthy" to mean whatever you want it to mean

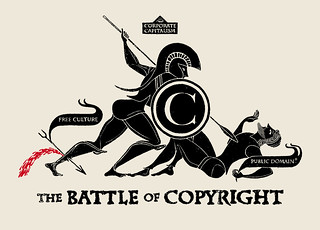

Check Out: A New Index of Copyright Fair Use Cases

Source: Christopher Dombres via Flickr

The U.S. Copyright Office has launched a new Fair Use Index:

Fair use is a longstanding and vital aspect of American copyright law. The goal of the Index is to make the principles and application of fair use more accessible and understandable to the public by presenting a searchable database of court opinions, including by category and type of use (e.g., music, internet/digitization, parody).

The Fair Use Index is designed to be user-friendly. For each decision, we have provided a brief summary of the facts, the relevant question(s) presented, and the court’s determination as to whether the contested use was fair.

The Index itself is a series of summaries of key legal decisions regarding copyright and fair use, largely from the last sixty years.

It’s super interesting to me! Wondermark is, of course, created using images from the public domain. Which is not the same as fair use; public domain works have no copyright, whereas fair use is made of works that are copyrighted.

But copyright in all its gleaming facets is still a topic near and dear to my heart as an artist, author, and attentive internet citizen: I’ve written a fair amount about copyright and intellectual property.

The Fair Use Index includes some watershed copyright cases, such as 1978′s Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, the precedent that defines the infringement threshold for copying copyrighted characters for “parody” purposes.

It might be said that under the Air Pirates test, the entire product line of the t-shirt website TeeFury is illegal, and I notice that very conveniently, most of their designs are only available in strictly limited, before-they-can-send-us-a-cease-and-desist editions.

Also included is the “Betamax” case, 1984′s Sony Corporation v. Universal City Studios, which ruled that recording a free broadcast of live television onto videotape for later home viewing — referred to as “time-shifting” — was, indeed, legal. “Home taping” (of both television and radio) was the big I.P. boogieman threat before “piracy”, and this court decision was what enabled the VCR, as a consumer device, to exist at all.

In browsing, I also came across some interesting cases I hadn’t heard about before, such as:

• 1985′s MGM v. Honda Motor Corp., in which MGM sued — and won — claiming that a spy-themed Honda commercial was too reminiscent of their copyrighted character, James Bond (and that it damaged the James Bond brand to show him in a Honda);

• 2004′s MasterCard v. Nader 2000, in which MasterCard sued — and lost — a copyright infringement suit against Ralph Nader’s presidential campaign commercials which copied/parodied its “priceless” slogan;

• 2006′s CleanFlicks v. Soderbergh, in which the company CleanFlicks, which edited objectionable content out of Hollywood movies and re-sold them to customers who preferred them that way, sought a declaratory judgment that doing so was legal — and lost. They thought they’d be OK because they’d buy a copy of the actual DVD, add in the edited version, and re-sell that precise physical DVD — not unlike buying a book, blacking out various passages, and then re-selling that physical book. Anyway, they lost;

• And of course, 2011′s CCA and B v. F+W Media, which ruled that the parody book Elf Off the Shelf (featuring a drunken, naughty elf), was, indeed, legal. Thank God for that.

The Fair Use Index: really great browsing, if you’re interested in copyright!

Does Spacetime Emerge From Quantum Information?

Quantizing gravity is an important goal of contemporary physics, but after decades of effort it’s proven to be an extremely tough nut to crack. So it’s worth considering a very slight shift of emphasis. What if the right strategy is not “finding the right theory of gravity and quantizing it,” but “finding a quantum theory out of which gravity emerges”?

That’s one way of thinking about a new and exciting approach to the problem known as “tensor networks” or the “AdS/MERA correspondence.” If you want to have the background and basic ideas presented in a digestible way, the talented Jennifer Ouellette has just published an article at Quanta that lays it all out. If you want to dive right into some of the nitty-gritty, my young and energetic collaborators and I have a new paper out:

Consistency Conditions for an AdS/MERA Correspondence

Ning Bao, ChunJun Cao, Sean M. Carroll, Aidan Chatwin-Davies, Nicholas Hunter-Jones, Jason Pollack, Grant N. RemmenThe Multi-scale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (MERA) is a tensor network that provides an efficient way of variationally estimating the ground state of a critical quantum system. The network geometry resembles a discretization of spatial slices of an AdS spacetime and “geodesics” in the MERA reproduce the Ryu-Takayanagi formula for the entanglement entropy of a boundary region in terms of bulk properties. It has therefore been suggested that there could be an AdS/MERA correspondence, relating states in the Hilbert space of the boundary quantum system to ones defined on the bulk lattice. Here we investigate this proposal and derive necessary conditions for it to apply, using geometric features and entropy inequalities that we expect to hold in the bulk. We show that, perhaps unsurprisingly, the MERA lattice can only describe physics on length scales larger than the AdS radius. Further, using the covariant entropy bound in the bulk, we show that there are no conventional MERA parameters that completely reproduce bulk physics even on super-AdS scales. We suggest modifications or generalizations of this kind of tensor network that may be able to provide a more robust correspondence.

(And we’re not the only Caltech-flavored group to be thinking about this stuff.)

Between the Quanta article and our paper you should basically be covered, but let me give the basic idea. It started when quantum-information theorists interested in condensed-matter physics, in particular Giufre Vidal and Glen Evenbly, were looking for ways to find the quantum ground state (the wave function with lowest possible energy) of toy-model systems of spins (qubits) arranged on a line. A simple problem, but one that is very hard to solve, even on a computer — Hilbert space is just too big to efficiently search through it. So they turned to the idea of a “tensor network.”

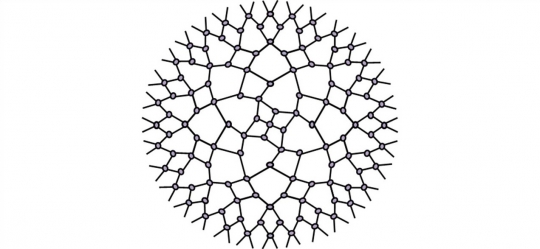

A tensor network is a way of building up a complicated, highly-entangled state of many particles, by starting with a simple initial state. The particular kind of network that Vidal and Evenbly became interested in is called the MERA, for Multiscale Entanglement Renormalization Ansatz (see for example). Details can be found in the links above; what matters here is that the MERA takes the form of a lattice that looks a bit like this.

Our initial simple starting point is actually at the center of this diagram. The various links represent tensors acting on that initial state to make something increasingly more complicated, culminating in the many-body state at the circular boundary of the picture.

Here’s the thing: none of this had anything to do with gravity. It was a just a cute calculational trick to find quantum states of interacting electron spins. But this kind of picture can’t help but remind certain theoretical physicists of a very famous kind of spacetime: Anti-de Sitter space (AdS), the maximally symmetric solution to Einstein’s equation in the presence of a negative cosmological constant. (Or at least the “spatial” part thereof, which is simply a hyperbolic plane.)

Of course, someone has to be the first to actually do the noticing, and in this case it was a young physicist named Brian Swingle. Brian is a condensed-matter physicist himself, but he was intellectually curious enough to take courses on string theory as a grad student. There he learned that string theorists love AdS — it’s the natural home of Maldacena’s celebrated gauge/gravity duality, with a gauge theory living on the flat-space “boundary” and gravity lurking in the AdS “bulk.” Swingle wondered whether the superficial similarity between the MERA tensor network and AdS geometry wasn’t actually a sign of something deeper — an AdS/MERA correspondence?

And the answer is — maybe! Some of the features of AdS gravity are certainly captured by the MERA, so the whole thing kind of smells right. But, as we say in the paper above with the expansive list of authors, it doesn’t all just fall together right away. Some things you would like to be true in AdS don’t happen automatically in the MERA interpretation. Which isn’t a deal-killer — it’s just a sign that we have to, at the very least, work a bit harder. Perhaps there’s a generalization of the simple MERA that must be considered, or a slightly more subtle version of the purported correspondence.

The possibility is well worth pursuing. As amazing (and thoroughly checked) as the traditional AdS/CFT correspondence is, there are still questions about it that we haven’t satisfactorily answered. The tensor networks, on the other hand, are extremely concrete, well-defined objects, for which you should in principle be able to answer any question you might have. Perhaps more intriguingly, the idea of “string theory” never really enters the game. The “bulk” where gravity lives emerges directly from a set of interacting spins, in a context where the original investigators weren’t thinking about gravity at all. The starting point doesn’t even necessarily have anything to do with “spacetime,” and certainly not with the dynamics of spacetime geometry. So I certainly hope that people remain excited and keep thinking in this direction — it would be revolutionary if you could build a complete theory of quantum gravity directly from some interacting qubits.

Weed People Problems

As I write this, I am sitting in an apartment in the Logan Square neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois. Six months ago, I was writing from an apartment in the University District of Seattle, Washington. There are many things that make the two places distinct, but today I am thinking about how, in my previous home, I could buy and consume marijuana whenever I liked, and in my new home, I cannot buy it, use it, or even possess it under any circumstance whatsoever.

Seattle did not, to put it mildly, cover itself in glory when it came time to legalize recreational marijuana. Of the three states that have done so, its laws were the most incompetently, incompletely, and haphazardly enacted. The entire process was, and continues to be, fraught with bad faith, bad planning, and a poorly thought out implementation scheme. However, at the bottom line, there was the fact that, even if it was far more difficult to do so, anyone of legal age could purchase this harmless euphoric plant, consume it, and face no possibility of punishment from the law for doing so.

It’s hard to express how different this was from my prior experience of buying weed. For decades, it was a process infused with fear and peril; since I’m not black or Latino, the consequences for handling weed were never going to be fatal for me, but I certainly stood a good chance of going to jail, possibly for a long time. I could lose my job, I could find myself with a criminal record that made me unemployable, or I could serve serious time if I was arrested for marijuana crimes more than once; all of these things happened to people of my personal acquaintance. Beyond the legal issues, there were questions of quality (one could never be sure if the product one was buying was of good quality, or pencil-shavings skunkweed that would barely get you off), of availability (a big police bust could lead to a weed drought that would last for months), and of personal safety (whether you bought or dealt, there was an irreducible chance at every deal that you could wind up with a gun in your face, wielded by someone who’d figured out a way to make easy money). If you bought bad product, whether it was merely poor quality or actually tainted with vile chemicals, you had no recourse; you could tell no one in authority what you had done, let alone seek recompense for being ripped off.

In Seattle, of course, things were different. Even with the incompetent administration of recreational laws, good-quality product could be found everywhere, at reasonable prices. You could be assured you were getting what you paid for; regulations assured that your purchase be labeled, sourced, traceable, and subject to the same quality controls as foodstuffs. You could walk around with marijuana on your person without fear of being thrown in jail or destroying your life; you could sell it without fear of being the victim of a stick-up and having no legal recourse. You could be high in public and worry about nothing more consequential than being laughed at for your goofy behavior. You could even call a number and have a wide range of cannabis products delivered to your home quicker than you could order a pizza. Of course, common sense was included in the mess of a regulatory package; there were limits on how much you could transport, and you could not drive under the influence. But the difference in the way one felt about engaging in this simple, victim-free habit was striking.

Of course, there were issues. All of them arose from the half-assed way the recreational laws were written and enforced in Seattle; there are still restrictions on where weed can be smoked, grown, sold, and distributed, and these laws, as laws do, tend to marginalize minorities. Kinks must be worked out, and it’s pretty likely that, like most capitalist enterprises, it will end up favoring the already-wealthy. There is still a clash with the White House over the issue of whether states’ rights trump federal law in this case, or if it only applies to matters of subjugating blacks and women. But, critically, all of the issues now — as they did before — have to do only with the issues of illegality and enforcement. The legalization of marijuana for recreational use in Washington, as in other states, has in every other way not changed the daily lives of its citizens at all, unless it is for the better.

Colorado and Washington have both seen massive influxes of revenue: taxation, new employment, consumption, and tourism have all received a boost. There has been no notable spike in crime; indeed, most precincts report that, freed from the burden of busting people for petty weed offenses, officers are free to concentrate on more serious crimes. The majority of marijuana-related legal problems in these states stem from keeping the product out of neighboring states that still cling to their prohibition. All the predicted menaces — an influx of dangerous criminals, massive truancy, traffic accidents, little kids overdosing, high dropout rates, and the usual laundry list of horror ported in from alarmist tracts written in the 1930s and 1960s — have failed to significantly manifest; some are nonexistent, some are minimal, some have had the opposite effect (Colorado has actually seen a decline in traffic accidents, likely due to a decrease in drunk driving). Every prediction of the prohibition lobby has largely been a dud, while every prediction of the legalization lobby has more or less come to pass.

Meanwhile, in Illinois, we await the results of newly-approved medical marijuana laws. People still sell weed as they have always done, fearful of arrest or violence. People still buy weed as they have always done, fearful of ruin or disgrace. The product remains a risk for the seller and a crapshoot for the buyer; droughts still occur; and even if medical marijuana is phased in without a hitch, it will still leave millions of recreation users scrabbling in the shadows as before. No one will be harmed by consuming marijuana except in the framework of its prohibition. I will still be afraid of writing stories like this, throwing up a smoke screen of theoreticals and rhetoricals lest I run afoul of the law or risk offending an employer. Patients will keep having to use unreliable and possibly hazardous channels to treat conditions alleviated by cannabis, or rely on taking prescription drugs that are far more expensive, far more addictive, and far more likely to cloud their thinking and negatively alter their lives. Alcohol — now as ever more easily acquired than marijuana has ever been or will ever be — will continue to kill tens of thousands of people a year in America, while the world rolls on waiting for its first ever cannabis fatality. In one state, there is misery, and in the other there is liberty; and the only difference is the law.

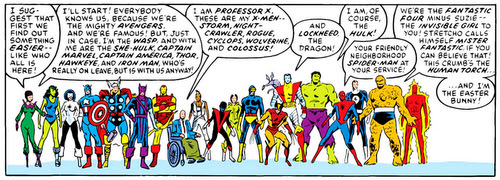

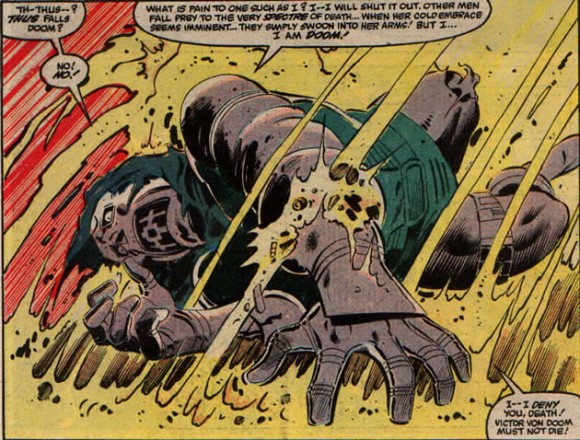

Excelsior

It's a familiar story. I'll bet you've heard it before.

It was the late fifties. The comic industry was still in a state of suspended animation following the dramatic events of the anti-comics backlash of the Wertham era. Atlas was a small outfit whose greatest asset in a rapidly shrinking marketplace was the business acumen of its publisher, Martin Goodman. Atlas' in-house distribution company had been shuttered due to lack of volume. Their second distributor, American News, collapsed in short order. Goodman made a deal with National's distributor, Independent News, to piggyback on the company's newsstand access.

But Atlas was still dying. Almost the entire staff had been laid off following the discovery that the company had enough unpublished inventory to run for the better part of the year. Even that wasn't enough to keep the doors open. And so, the story goes, a man named Jack Kirby walked through the doors. He had just split with his longtime partner Joe Simon, after their publishing company had collapsed. (1954 was not the most auspicious year to start a comic book company.) He couldn't find work at National (later DC) on account of a failed lawsuit. Kirby and Atlas were both grasping at straws in an industry that, aside from major publishers such as National, Dell, and Archie who emerged from the Wertham era relatively unscathed, was circling the drain.

I came in [to the Marvel offices] and they were moving out the furniture, they were taking desks out — and I needed the work! ... Stan Lee is sitting on a chair crying. He didn't know what to do, he's sitting on a chair crying — he was still just out of his adolescence. I told him to stop crying. I says, "Go in to Martin and tell him to stop moving the furniture out, and I'll see that the books make money".(*)Or so the story goes. Kirby later on had reason to emphasize his significance alongside Lee's impotence, just as Lee had his motivations for denying Kirby's dramatized version of events. Lee was also 35 when Kirby returned.

The important facts are this: Atlas had been a company named Timely. The company had been founded by Goodman, primarily a publisher's of men's magazines and pulp adventure books. Stan Lee was Goodman's cousin by marriage. He joined the company at its start, working as an assistant at age 16, and editor by 19. Aside from a stretch in the army during the war, Stan Lee never worked for another company besides Marvel. It was the family business. Imagine his chagrin when, years later, in the flush of over a decade's worth of sustained success, people began asserting that his company's success was due to Kirby, alongside Steve Ditko and others. How galling. Lee had been there from the beginning.

Marvel Comics is the offspring of Stan Lee's perpetual frustration. For all the dispute over credit that has dogged Lee and his company for over fifty years (even further if you consider Simon & Kirby's unhappiness regarding Captain America), the character of Marvel Comics was all Stan. This was the myth you bought into when you became immersed in the books. They were hip, they were happening, they were cooler than Brand X. Marvel was what cool college kids read - literally, your older brothers' comic books, not like those staid Superman magazines you read as a child. Marvel Comics was on the verge of world domination, and Stan was the man with the plan.

It was an attractive myth because everyone but young children knew it was just that - a myth. Marvel was cool and the books were better than National - and all their later imitators - and all that was true, at least for a while. But they remained stuck playing the role of perpetual underdogs even after the reality had shifted. Even into the 1970s, long after Marvel had escaped their distribution deal with National and become the dominant force in the marketplace, they still nourished the illusion of outsider status. It was a great thing to become a Marvel fan: it was like becoming a member of a secret club, and long after you should have known better, the identification somehow stuck. DC, for their part, (somewhat unwittingly) embraced their status as the Evil Empire: DC was a place where men wore suits and ties to work, with offices staffed by old pros who consistently dismissed their upstart competitor until it was too late to reverse the damage. Marvel was the place where a few crazy middle-aged men had accidentally created a counter-culture incubator, as the company became increasingly dominated by younger men (and even a few women) who had grown up reading the books and very much wanted to be a part of the clubhouse Stan had built. The company depended on the perpetuation of these myths to maintain forward momentum.

As successful as Marvel became, the company never outgrew Lee's frustration. There was a ceiling to the company's relevance. DC was bought by Warner Brothers, and Warner Brothers in turn produced a few successful (and not so successful) movies based on DC's IP. Lee spent many years after leaving day-to-day operations of the company trying and failing to sell Marvel's IP to Hollywood, with very little success. A handful of cartoons. A few live-action TV shows, only one of which ever amounted to anything. One big-budget debacle that ruined the company's name in Hollywood for years after. But above all else, the main product of these years of mostly wasted effort was dozens and dozens of hints and half-promises made in the pages of Stan's Soapbox over the course of decades. James Cameron was going to direct a Spider-Man film for something like a decade. Lee first announced the development of an Ant-Man film in 1990. That never happened, obviously.

The history of Marvel in Hollywood is a history of near-misses and missed opportunities. Lee never gave up hope. Even after he ceded control of his own company, even after the company changed hands, even after a lifetime of creative controversies began to take a serious toll on his public image, he persisted as "Mr. Marvel." And to a degree, at least, he personally remained something of an underdog: the man who had co-created the Marvel Universe, the guy whose uncle had founded the company, adrift in a larger, indifferent world. He never got around to writing the Great American Novel, and he never made a movie with Alan Resnais, and he never got out of Marvel's shadow. Why would you want to? He was The Man.

At their creative pinnacle in the mid 1960s, Marvel succeeded creatively by being both more primitive and more sophisticated than their rivals. But in terms of their business, Marvel succeeded the same way they always succeeded: they flooded the market and undercut the competition. As soon as Marvel regained distribution capabilities in 1968, they expanded precipitously. In 1971 they tricked DC into shooting itself in the foot by faking out the competition with a (seeming) line-wide price hike from 15 to 25 cents. DC responded by doing the same. Marvel's price hike lasted one month, after which they reduced prices to 20 cents, but DC was stuck with the 25 cent experiment for months afterwards. In the time it took DC to course-correct, they permanently lost market share. Marvel began to franchise their most popular characters into multiple books. By the late 80s, soon after Jim Shooter left the company, Marvel set out to flood the market in earnest. This was the beginning of another disastrous boom/bust cycle - a boom made even worse by subsequent mistreatment of prominent talent, who left the company to form a third major publisher, Image. (The books continued to sell after the talent left, once again reinforcing the idea that the Marvel brand would always be bigger than any individual creator.) There were a number of factors involved in the mid-90s industry breakdown, but Marvel made the worst mistakes, and the mistakes were big enough that they barely survived.

Marvel 2015 is still fundamentally the same company it was back in the mid-50s, when Martin Goodman found a cabinet full of inventory and used it as a pretense to fire everybody for six months. For all the criticism aimed at Isaac Perlmutter, he's still playing from the Goodman / Lee handbook: flood the market, undercut creators, and pray you survive the next bust. With Disney at their back they no longer need to fear the bust, and have proceeded accordingly.

Left unchecked, the company has recreated the entertainment industry in its own image. The occasion of Avengers 2 has provided movie critics and industry observers another opportunity to bemoan Marvel's success, and its not hard to see why they'd be so resentful. As bad an industry as Hollywood has always been, Marvel is worse in almost every way. Instead of franchises taking two-or-three years between installments, Marvel has figured out a way to keep successful franchises in theaters twice a year. They've proven so successful that every other entertainment conglomerate is changing their business model to compete - even Disney itself is looking to Marvel as a model for its resuscitation of the Star Wars franchise. Right now Marvel Entertainment has a hold on the popular imagination, and the imagination of the industry, that simply defies comparison: there's never been anything like it before. Even if the superhero bubble burst tomorrow, the structure of the entertainment industry will already have been permanently altered.

And it's no accident. They got to where they are today by importing Lee's playbook intact from the company's heyday. Marvel isn't a company, it's an experience. If you buy a ticket for a Marvel movie, you're buying into the experience of being part of something larger than a single movie. Everyone loves Marvel, and if you love Marvel too, you're part of a special club. People cheer when the red Marvel logo comes onscreen, and they get excited about recognizing obscure plot points from comic books they've never read, but have read about.

People have been predicting the end of the superhero movie boom for almost fifteen years - as long as there have been superhero movies, basically. The gloomiest predictions always seem to come from comics fans themselves, who recognize in themselves an incipient exhaustion with the genre that simply has not yet manifested in the general public. There are decades worth of stories left to strip-mine for basic parts. If Marvel keeps a tight ship they'll be in a good position to ride the bubble in perpetuity. If they (and Disney) are smart they'll be able to pivot when the market goes south, leaving their competitors holding the bag, selling the equivalent of 25 cent comics in a 20 cent market.

But what about Stan?

Stan lived to see his company take over the world. After decades of trying and failing to expert Marvel, it finally happened after he was no longer directly involved. He's still the figurehead, naturally, and for so long as he lives he will continue to receive his rote cameo in every Marvel movie and TV show. The problem is that the ideology Lee cultivated in the 1960s, when Marvel was a legitimate underdog in an industry that had spent the past decade trying to run his family company out of business, doesn't carry the same meaning. Marvel isn't the dark horse anymore, they're the heavy favorite. They are owned by the largest entertainment company on the planet, and they are possibly the most valuable arm of that conglomerate. The grasping ambition that Lee once cultivated was charming, in its day, part and parcel of a fantasy where Marvel was in a state of constant siege. They were self-effacing and ironic, and it was them (and you, True Believer!) against the world. The problems began when Lee started to believe his own press, and were compounded when his personal insecurities were inflated into a corporate ethos. This is the world he and his uncle made, whether or not they foresaw the consequences.

Marvel Entertainment are not nice people. They like having an avuncular mascot to trot out and reassure people that these entertainment products are made by the same kind of people who hand-crafted the original comics, but that's a lie. It's not about people at all. It's about a company with a seventy-five year track record of scorched-earth business tactics doing everything they can to maximize their leverage on largest scale possible, the kind of scale not even Lee himself could ever have imagined.

You can't root for Marvel anymore. It's like rooting for McDonalds. Once upon a time Stan Lee believed himself to be Ray Kroc, but for a while now he's been Ronald McDonald.

http://www.andrewrilstone.com/2015/05/i-had-intended-you-to-be-next-prime.html

Anon

I had intended you to be

The next Prime Minister but three

The stocks were sold, the press was squared

The middle-class was quite prepared

But as it is, my language fails.

Go out and govern New South Wales!

Belloc

"On its world", said Ford "The people are people. The leaders are lizards. The people hate the lizards and the lizards rule the people."

"Odd," said Arthur, "I thought you said it was a democracy."

"I did," said Ford. "It is."

"So," said Arthur, hoping he wasn't sounding ridiculously obtuse, "why don't people get rid of the lizards?"

"It honestly doesn't occur to them," said Ford. "They've all got the vote, so they all pretty much assume that the government they've voted in more or less approximates to the government they want."

"You mean they actually vote for the lizards?"

"Oh yes," said Ford with a shrug, "of course."

"But," said Arthur, going for the big one again, "why?"

"Because if they didn't vote for a lizard," said Ford, "the wrong lizard might get in. Got any gin?"

"What?"

"I said," said Ford, with an increasing air of urgency creeping into his voice, "have you got any gin?

Douglas Adams

I guess the first time I ever heard about a union, I wasn't more than eight years old. What I heard was the story of the two rabbits.

It was a he-rabbit and a she-rabbit that a pack of hounds was chasing all over the countryside, and finally these rabbits they holed up inside a hollow log.

Outside the dogs was a-howling.

The he-rabbit turned to the she-rabbit and he said, "What do we do now?"

And the she-rabbit, she just give him a wink and said "We stay here til we outnumber them."

Woody Guthrie

Alan Moore

The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult, and left untried.

Chesterton

The Hugos Not Actually Being Destroyed, Part the Many

(Warning: Hugo neepery follows. Avoid if you’re bored of it.)

It’s been a week or so since I’ve posted about the Hugos here, so that’s good. But there’s a persistent shibboleth I see bruited about, which is that the events of this year have in some way destroyed the Hugos (most recently here, in an otherwise cogent set of observations). I’ve addressed this before, but it’s worth addressing again. Here it is:

1. No, the Puppies running their silly slates have not destroyed the Hugo Awards. What they have done is draw attention to the fact that the nomination system of the Hugos has a flaw.

2. The flaw: That an organized group pushing a slate of nominees can, if the group is sufficiently large, dominate the final ballot with their choices.

3. The flaw was not addressed before because, protestations to the contrary, no one had run a comprehensive slate before. No one had run a comprehensive slate before because, bluntly, before this year, no one wanted to be that asshole. This year three people stepped up to be that asshole and got some party pals to go along.

4. The flaw is fixable by addressing the nomination process so that a) slating is made more difficult, while b) the fundamental popular character of the Hugos (i.e., anyone can vote and nominate) is retained. There are a number of ways to do this (the simplest would be to allow folks to nominate three works/people in each category and have six finalist slots on the ballot; there are more complicated ways as well), but the point is that there are options.

5. The nature of the Worldcon beast is that these changes will take a couple years; in the meantime, everyone who nominates (and votes on the final ballot) deals with the fact there are a few people out there who want to crap on the process because they’re whiny stompy children and/or complete assholes. It’s annoying but it’s dealable, so we deal with it until fixes can be made. We’re grownups; grownups sometimes have to deal with whiny stompy children being assholes.

Mind you, the Puppies would be pleased for you to think of them as deep thinking masterminds who are always one step ahead. But, you know, it doesn’t take a mastermind to exploit an aspect of a nomination system that everyone knows is there but no one else exploited because they are grown adults with enough social skills to know better. It just takes someone willing to be an asshole. Masterminds may be assholes (I’ve not met enough masterminds to say), but being an asshole is not sufficient to be a mastermind — and I have met enough assholes to feel confident about that. No one among the Puppies is a mastermind. They are merely assholes.

(This is why the people who have decided to vote “No Award” ahead of anything or anyone on a slate should not feel in the least bit bad about doing it: It’s perfectly fine and well within the rules to vote against people who wish to confirm to the public that they are assholes, and are using the Hugos as the instrument of that confirmation. You don’t give a toddler a candy bar for throwing a tantrum. There are also reasons not to do a blanket “No Award” vote, but let’s not pretend that the “No Award” option isn’t valid. It is. It’s a way of saying “nice try, but no, and also, you’re an asshole.”)

And yes, it’s a shame that now we have to factor rank assholery into the Hugo nomination process, but there it is, and the sooner it’s dealt with the better. Then the Hugos can get back to what they’ve been good at: A popularly-voted genre award that, for all its flaws, does a relatively decent job (particularly in conjunction with the other genre awards) of taking the temperature of the field in each particular year.

So, in sum: Hugos not destroyed; flaws in process revealed; flaws are fixable; some people are just assholes.

And that’s it.

This Irregularity Has Been Recorded

It begins, arguably, with 'The Macra Terror'... though so much of what that story does 'first' is actually just being done openly and consciously for the first time. Other examples include (most graphically) 'The Sun Makers', 'Vengeance on Varos', and 'The Happiness Patrol'. I'd argue for a few others to go on the list, but these are the most obvious examples. 'The Beast Below' carried on the tradition, as did 'Gridlock' before it (albeit mutedly). Yet many of these stories have been subject to readings which interpret them as right-wing and/or libertarian attacks on aspects of socialism and/or statism (often assumed to be synonymous). I might even (overall) support such a reading in some cases. 'The Beast Below', for example, is a story which critiques aspects of the capitalist world, but which (to my mind) ends up supplying more alibis than indictments - partially through its use of totalitarian/statist tropes. I think the thing that leaves them open to such readings is their 'totalitarian' aesthetic. The (myopic, ideologically-distorted) view of socialism which sees it as inherently coercive and statist can grab hold of the aesthetically magnified symbols of statism which litter these stories.

I think this tendency to wrap critiques of capitalism in totalitarian aesthetics comes from the influence of the Nigel Kneale / Rudolph Cartier TV version of Nineteen Eighty-Four, which starred Peter Cushing.

Stylistically, this production appears to have been deeply influential to the rising generation of programme-makers who would write and design Doctor Who in the 60s. The totalitarian affect pioneered visually in that production gets embedded in Doctor Who's internal semiotic repertoire as a stock way of expressing worries about social freedom.

This isn't surprising at all, since the aesthetics of totalitarianism have proven a popular and enduring way of expressing such worries in the wider culture, as the proliferation of SF dystopias has shown. They're now almost a basic, fallback position for YA books and films.

But we need to do more than just gesture to a particularly influential production. That's not enough. It's not an explanation. You can't just say 'this production here was influential'. That's just begging the question. The real question is: why was it influential? What was it about it that made its aesthetics stick so hard?

I think the answer actually lies back in the book. Much of the horror of the book is the everyday horror of squalor - whether it be the squalor of coldness and dirt and forced 'healthiness', or the moral squalor of everyday ideological management. Orwell gets the former from his experiences of public school (which he wrote about elsewhere with loathing) and the latter from his experiences of working within the BBC. Even Newspeak is derived from work he did for the BBC World Service in India. The book is also obsessed with the horror of poverty, whether it be the relative poverty of the lower middle classes scraping by in an austere world of rations and shortages, or the more absolute poverty of the proletariat.

Oceania is a howl of disgust at the world Orwell came from as much as it's a parodic howl of fear at the rise of totalitarianism. In his gorge, he felt the nauseating similarity of the collectivist oligarchies of public school, British imperial police, BBC, and Stalinist Party. Indeed, part of how he was able to speculate so accurately about what it was like to live in Stalinist societies is owing to his experiences of living within hierarchical structures of coercion within his own society. He sees the sanctimonious regulation of life within totalitarian structures like the Stalinist Party clearly because they chime with his experiences of public school and bourgeois middle-class life. Exactly the resonance which attracted so many British middle-class intellectuals to Stalinist organisation repelled Orwell. He runs like fuck while they happily reintegrate... and yet he is irresistibly drawn to write about it. (A powerful psychological substrata in Orwell's work is a feeling of irrisistible attraction to things that horrify.)

It's not hard to see how the kinds of neurotic feelings of attraction/repulsion which animated Orwell might also animate a later generation of educated, British BBC men, usually from some level of the middle class, and often themselves public school educated.

Robert Holmes in particular (writer of, most pertinently for this essay, 'The Krotons', 'The Sun Makers','The Deadly Assassin' and 'The Caves of Androzani') has peculiar echoes of Orwell. He was in Burma during the war and was then a policeman before he worked for the BBC. Orwell was a colonial policeman in Burma before he worked for the BBC. I don't know if Holmes went to public school (nobody - not even his biographer - seems to know where he went to school), but he certainly endured army life and Hendon Police College.

Ian Stuart Black, author of 'The Macra Terror', attended Daniel Stewart's College in Edinburgh.

He then joined the RAF at the outbreak of World War II and worked in intelligence in the Middle East.

I'm not saying Black loathed public school and the RAF. I don't know how he felt about them. What I'm saying is that he's an example of a BBC man of that generation, and he lived in hierarchical structures similar to the ones Orwell lived in, owing to their similar class positions and careers.

But we need to go a little deeper still.

Why does Nineteen Eighty-Four, when rendered as a TV show by the BBC, come to wield such influence? It must be more than the fact that the book's depiction of cold showers, hectoring compulsary P.E., pious sanctimony, and ideologically-drenched clerical work, resonated with a bunch of the corporation's talented hacks.

On a superficial level, it's because the Kneale script subtly tweaks the story to make it more like SF than Orwell's more Swiftian approach. On a less superficial level - and this is what I really wanted to get to - it's because totalitarian societies are also capitalist.

It could hardly be otherwise. Totalitarianism (not a word I'm fond of, but it'll do for now as a placeholder to denote something we all recognise) depends upon the industrial, economic and political developments of capitalism to exist. It depends upon modern industry, classes divided by their relation to production, the bourgeois family, the standing army, imperialism, a standing police force, bureaucracy, a strong state, central government, etc.

The workers' state would also depend upon such things, but as a springboard rather than a prop. The workers' state would pull itself up on top of such things the better to bury them. The Stalinist state was a failed workers' state. It was unable to transcend the bourgeois mode owing to the undeveloped nature of the Russian forces of production, relative scarcity, outside attack, a devastating civil war (started as a war of aggression by the Western powers), and isolation after the failure of the German Revolution. By contrast, the fascist states in both Germany and Italy (and in a more mediated way in Spain) arose as direct reactions against more-or-less revolutionary threats to unstable national capitalisms. (This is why I don't really like the term 'totalitarian' as it pays too much attention to superficial aesthetic similarities at the expense of embracing an ahistorical narrative. The 'fascists' in Russia were the West-sponsored White counter-revolutionaries.) The Nazis arose in Germany as a form of class collaboration between those bourgeois forces which felt threatened by Communism and the insurgent German working class. The failure of German workers and socialists to pre-empt or defeat this reaction is a huge part of what led to the isolation of the workers' state in Russia and its subsequent degeneration into Stalinism. The people who made the Russian Revolution knew full well they would be doomed to fail if world revolution didn't spread to more-developed allies.

Stalinist Russia was state capitalist. It never became socialist or communist in the Marxist sense. It was a workers' state which degenerated into an extreme form of state capitalism through historical contingency - isolation, attack, civil war, the rise of a bureaucratic layer following the near-elimination of the working class, etc. (I was never a member of the now deservedly self-ruined SWP, but I broadly accept their theoretical standpoint on state capitalism.)

Thing is... all capitalist states are state capitalist to some degree. This sounds like an obvious tautology, but you'd be amazed how many people buy the idea that capitalism is something fundamentally seperate from the state, capable (at least theoretically) of subsisting without it. Much as the ideologues of capitalism like to pretend that individual freedom is the essence of capitalism, the truth is that capitalism is actually impossible without massive state intervention and support.

This has never been more true than now, in the age of neoliberalism when the state has supposedly been rolled back. The state works tirelessly to keep the peace and order of capitalist social systems, to manufacture ideological and material complicity, and to redistribute wealth upwards from the working class and into the hands of private capital. That's what Austerity is, for instance: another form of neoliberal praxis for creating the trickle-up-effect.

The state and society are not seperate things, the latter superimposed upon the former, or squatting on top of it like some kind of malevolent succubus - a mistake made commonly by libertarians, liberals and some varieties of anarchist. The state is part of society. It is a superstructural emanation. It is that part of class society which coercively regulates the order, reproduction and stability of the system. It positions itself and discourses about itself as something above and seperate from society, yet morally responsive and responsible to it. The truth is the exact opposite.

You can see the crucial role of the state very clearly by looking at the state now, but you can perhaps get even more clarity via historical distance, which thins out at least some of the ideolgical fug. When you look at the capitalist states in and around the era of the Great Depression, you see an intense process of increasingly conscious and sophisticated state fusion with capital (this, of course, is the essence of capitalist imperialism... and so is hardly unrelated to the outbreak of World War).

The Nazi state utilised heavy state control and investment, even as it allied with and supported national bourgeois class allies, in order to stimulate the economy and build up imperial capability. The Stalinist state was a state involved in breakneck industrialisation. That's why its horrors are so intense and drastic - they concertina the horrors of primitive accumulation, industrial revolution and early imperialist acquisition (all of which happened in Europe during the rise of capitalism) down into a compressed few decades of frenzied misery. You see it in America, perhaps most clearly when the US state stepped in to keep the tottering economic and financial sytem going, and to divert popular anger and resistance into state-funded stimulus packages (ie the 'New Deal'... which, incidentally, did much less to solve the Depression than arms spending and monopolisation).

Orwell was not a theoretically sophisticated thinker, and he certainly wasn't a neo-Trot avant la lettre. But he did understand (as Homage to Catalonia makes clear) that Stalinism and fascism were actually both forms of state capitalism... or, at least, of exploitative hierarchy with oppressed working classes. Nineteen Eighty-Four makes it clear that the working classes still exist and their labour is still exploited, very much as it always was. Part of the point of the book is that nowhere near as much has changed as the Party says has changed. One of the neglected subplots involves Winston trying to question 'Proles' about whether life is really different now. The indications are that they don't think so.

I think this is why the SF-inflected version of Nineteen Eighty-Four turned out to be so useful to Doctor Who. It's SF, so the show can co-opt it. And it's based on a fundamental recognition of the similarity of oppression in capitalist and 'totalitarian' systems, the difference being one of degree.

This is the deep cultural reason why the aesthetics of Nineteen Eighty-Four (via Kneale and Cartier when it comes to Doctor Who) get utilised in so many subsequent texts which employ the dystopian mode to express anxieties about social freedom. The story provides a logic that can express the essential syngergy of two supposedly inimical systems. This surfaces in 60s Doctor Who - perhaps most explicitly in 'The Macra Terror' - because of the cultural context of the times. Because of protestors beaten and tear-gassed by Western police forces who look worryingly like the Thought Police. Because of the seeping in of ideas originated by people like Eric Fromm and Herbert Marcuse... and yes, even by Trotsky and the New Left. It's important to remember that Fromm - a Marxist (on the whole) and a critic of both Western capitalism and Soviet Communism - was a bestselling writer a decade before 'Macra' was written. Fromm stresses alienation whereas Marcuse - also a trendy big-selling theorist - stresses control, but the cornerstone of Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man is his articulation of paralells between Western capitalist culture and the culture of the Soviet Union, and his critique of bureaucratic management in both systems. It was published in 1964.

There is much to be said about both these thinkers, and I would not endorse either of them without heavy caveats (to say the least), but the point here is that from a position of popular as well as academic fame, thinkers and ideas such as these were seeping into the wider mainstream culture of an increasingly uneasy post-war capitalism. This capitalism dwelt under the shadow of malaise, Vietnam, nuclear bombs, the revolt of colonised peoples against Western oppression, civil rights protests against institutionalised racism, popular rebellion amongst the young against war, and authoritarian police repression.

As 'The Macra Terror' understands, cognitive dissonance is a powerful thing. People in 'free' societies increasingly saw, at least on some level, the tesselation between what happened under so-called Communism and what happened at home.

People always talk about The Prisoner in relation to 'The Macra Terror', and that's probably because both feature systems of repression cloaked in... or rather structurally identical with... some kind of holiday resort aesthetic. The Village is a more middle class resort whereas the Colony is - as is well understood - a sort of working class holiday camp. But the deep connection between the two - beyond the material connection of Ian Stuart Black and Patrick McGoohan - is that the kitsch quasi-authoritarianism of structured leisure chimes with the kitsch actual-authoritarianism of repressive regimes, which include state-designed and state-monitored forms of entertainment. This happens because private capitalist forms of leisure which cater to the working classes in 'democratic' societies are as integrated into hierarchy as entertainment in 'totalitarian' societies, if less officially. Both feature forms of regimentation and containment appropriate to the organisation of the social lives of workers, with the appropriateness determined in an essentially inhuman method derived from the need to keep psychological discipline. At the risk of sounding paranoid and conspiratorial (because I think this happens largely as a self-organising, emergent property of hegemony), holiday camps were the way they were because they catered for people who needed to be happy to go back to work and follow orders again once the holiday was over.

As with Marcuse and Fromm, I wouldn't want to endorse Patrick McGoohan as a thinker without heavy caveats (one of the pleasures of writing this particular blog is that I can write sentences like that) but I will mention one scene from The Prisoner. It's the scene where Leo McKern's Number 2 tells Number 6 that he sees the whole world becoming (in the phrase 6 supplies for him) "as the Village". 2 says it will happen when the "two sides" (of the Cold War) "look across at each other and realise they are both looking into a mirror".

Be seeing you.

I Know How To Curse

1978: The Shooting Star

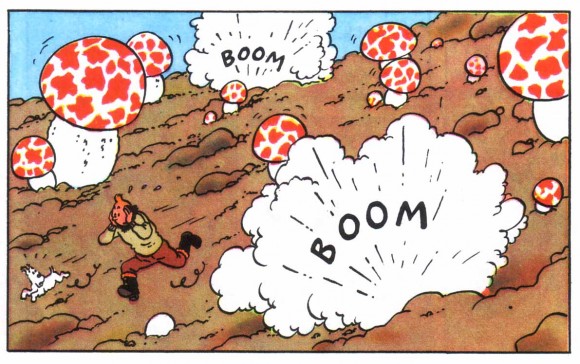

It’s the spider I remember. In The Shooting Star, boy reporter Tintin is investigating an apocalyptic threat, a star on a collision course with our world. He visits an observatory, hoping they can tell him what’s going on. They can: the world is doomed. He is led to the telescope and through it he sees a colossal spider, clinging to the star.

The beast is only on the telescope lens. And the world is not doomed. But I was entranced. By that, by the panic in the streets, by the race to reach a new island formed in the wake of the star’s passing, and by the grotesque exploding mushrooms our hero finds there. Tintin is the first comic I can remember reading, and The Shooting Star is my first memory of Tintin. In many ways, I wish it was almost any of his other adventures.

Tintin had a special status in our family. My Dad and his brothers and sisters grew up in the 50s and early 60s in Switzerland as well as Britain, as their father worked for the UN. Tintin was part of their childhood, followed in his own magazine, and with each new volume a bestseller. Those albums, in their original French, followed my Gran to England when she and Grandad divorced. I learned to read French by following my Dad’s translation of L’Ile Noire and Tintin En Amerique, at his knee. He bought me Tintin in English, the Methuen paperback editions. Some of those sit on our shelves now, creased, faded, and over-loved, supplemented with newer copies.

I am not the only person who holds Tintin in special affection. There are creators who establish the visual grammar and expectations of a whole style – a whole marketplace, in some cases. Kirby, Tezuka, Herge, and so on. To encounter them young is to be taught a language. Comics writer Kieron Gillen described Watchmen (which we’ll be meeting in 1986) as a comic that teaches you how to read it. Tintin, in its discreet, precise way, is a comic that teaches you how to read comics.

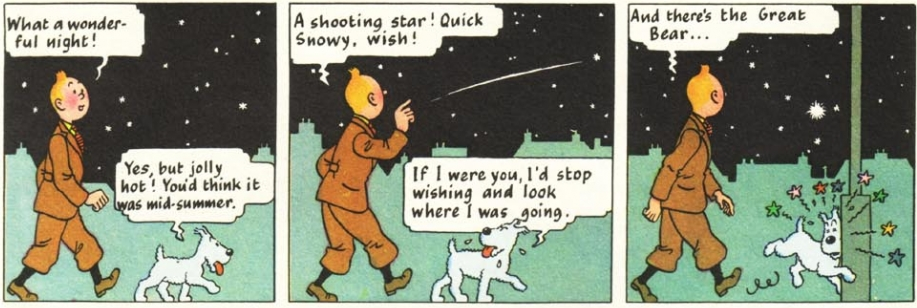

It does so almost invisibly. Herge never draws attention to his storytelling decisions: like his famously economical line, they are artefacts of impeccable design. A Tintin book is never flashy, never ambiguous or confusing – it is a gorgeously smooth reading experience, a user interface Apple would envy. It is not, however, cinematic – The Shooting Star is full of two-panel sight gags and payoffs that are utterly comic-y, relying on the sharp division of frames, not the fluidity of film or animation.

Take the first three panels of the book, a slapstick gag about Snowy walking into a lamp-post. In a cartoon, it would be very hard not to introduce the lamp-post before the collision, making the joke one of anticipation. On the page, lamp-post and collision can appear simultaneously, with Snowy’s forward motion suggested by the force of impact. Our eye has been tricked upward by Tintin pointing out the star, so it feels like Snowy paying the price for our misdirection.

(Meanwhile, for new readers, the panels introduce a lot of information: Snowy can talk, he is the comic foil for the observant Tintin, it is unnaturally hot, and – for the sharp-eyed – there is a huge new star in the middle of the Great Bear. That last is the one thing you might miss, so Herge includes it as exposition next panel while leavening any dryness with another joke – verbal, this time. This guy is tight, basically.)

Two other things stand out about Herge. First, he plays very fair. The vocabulary of adventure comics is one of tight squeezes and narrow escapes. There are lots of ways to convey peril like this – having the characters talk about it, most crudely, but also using foreshortening or dramatic cutting to heighten the imminence and narrowness of the danger while also drawing out its resolution. Herge’s approach is a more honest one: he establishes the physicality of a location precisely and doesn’t amplify it to make peril seem greater, relying on that clarity to make the danger more vivid. For instance, there’s a great scene in The Shooting Star where Snowy is on the deck of a pitching and tilting ship, in danger of being swept away. In quick cuts across half a dozen panels, Herge establishes Snowy’s presence on the deck, then a hole in the deck wall through which water is hurtling, then a surge of water which moves Snowy nearer the wall, then – oh no! – he’s half out of the hole before being grabbed by Tintin. It’s so basic that pointing it out seems insulting. But I will remember reading it for the rest of my life – the solidity of the wall and hole, the force of the spray exploding through it.

Herge is a creator you trust, then. And the second reason you trust is his attention to detail. A famously scrupulous researcher, his settings and vehicles are created with the precision of an Airfix modeller and then rendered with the satisfying plastic simplicity of a Lego builder. So, reading The Shooting Star, I knew that were I to ever see a seaplane, it would look like a Herge seaplane. (Tintin is full of seaplanes.) I knew that if I ever saw a Norwegian dock in the 1940s, it would look like the dock Captain Haddock stops in to refuel. If I ever clung to a lamp-post to watch rats surge through the streets… well, the lamp-post would be Hergeian too. He was scrupulous about this: apparently he fretted for years afterwards that Tintin’s ship would not in fact be seaworthy. But if I was ever on a ship looking for a crashed meteorite, I would expect it to look like Tintin’s ship, the Aurora.

And if I summon to mind a corrupt financier, surely he would look like the corrupt financier, Bohlwinkel.

Which is something of a problem. Because Bohlwinkel looks like – well, he is well-fed, balding, dark haired, with a long curved nose, fleshy, smirking lips, and beady, leering eyes. He looks like a caricature Jew, in a comic written and published in Nazi-occupied Belgium, in 1941. The very economy and exactitude, the trustworthiness, of Herge’s cartooning is suborned by a racist stereotype.

Which is something of a problem. Because Bohlwinkel looks like – well, he is well-fed, balding, dark haired, with a long curved nose, fleshy, smirking lips, and beady, leering eyes. He looks like a caricature Jew, in a comic written and published in Nazi-occupied Belgium, in 1941. The very economy and exactitude, the trustworthiness, of Herge’s cartooning is suborned by a racist stereotype.

It gets worse. Herge uses his command of the techniques of comics to continually remind us that Bohlwinkel is an alien presence, a foreign body within his story of scientific adventure. The rest of The Shooting Star is – as ever with Tintin – a world of detail: streets, docks, and crashed meteorites rendered with beautiful parsimony, always just enough to be real, never a line more. But Bohlwinkel’s panels are empty of background: he sits, leaning eagerly in to hear the radio, in a yellow space whose sharp, sickly vibrancy contrasts with the less jarring palette Herge uses for his outdoor action. He is an interruption in the story, never physically active, listening and manipulating. The heroic characters never meet him. His plots wither on contact with the real world, foiled by the camaraderie of sailors, the derring-do of Tintin, and the decency of the unnamed man on the rival ship who prevents Tintin being shot.

Bohlwinkel is the symbolic spider at the story’s centre, mirroring the physically monstrous spiders on the telescope and later on the meteorite-island. Of course the association, then and now, of Jews with spiders is an anti-Semitic commonplace. But you needn’t buy that parallel to grasp the role Bohlwinkel is playing. He incarnates the ancient prejudice of the Jew as schemer, string-puller, the secret conspiracy behind misfortune. He is considerably more than just a caricature, let alone an accidental one as Herge later hinted – everything about his role in the story and the symbolism it’s associated with is nakedly and purposefully anti-Semitic.

Herge pointed out that there are plenty of comic stereotypes all through Tintin – spoiled Arab brats, drunken Englishmen, nutty professors, and so on. He was, you might say, an “equal opportunities” satirist. He had even spoofed the Nazis themselves, in an earlier book, and deserves credit for that. But only one of his satirical targets was the simultaneous victim of organised state oppression, then genocide. Did the good, worried folk of Charleroi and Liege, presenting their papers and going about their daily lives under the Nazis, understand what was happening to the Jewish-owned businesses in their towns? What speculation reached them? They could, at least, open up Le Soir and escape with Tintin into a world that reassured them that whatever prejudices Europe’s Jewry faced, they had to a degree brought it on themselves. The Mysterious Star ended its run in May 1942, with an expression of comic horror on Bohlwinkel’s flabby face as his schemes are found out and he learns the authorities are on his trail. That same month, the Jews of Belgium were given a star of their own to wear.

Why has the anti-Semitism in The Shooting Star not destroyed its reputation? Tintin In The Congo, the boy reporter’s notoriously racist first adventure, now comes in shrinkwrap, with a stern warning to librarians. The Shooting Star is simply part of the canon. Part of it, I think, is that Herge shields Tintin himself from Herge’s own casual anti-Semitism. Congo is repulsive not just because of Herge’s gross caricatures of black people, but because Tintin is so explicitly the voice and hand of colonial power. Without racism, and the racial horror of Belgium’s Empire, there is no story in Tintin In The Congo. (There’s not much of one in any case.) In The Shooting Star, though, the main plot is of a race between international science and private enterprise for control of knowledge – with Tintin, sympathetically, on the side of science. The story requires a cheating capitalist. It does not require that capitalist to be a Jew.

Bohlwinkel is, of course, never named as such: when Herge put together the colour volume of The Shooting Star – the one we have now – he cut another anti-Semitic scene and changed his financiers name to Bohlwinkel from the more telling Blumenstein. He felt this defused the issue. But he did not redraw the man – and Bohlwinkel’s Jewishness exists as code, instantly obvious to most readers in Occupied Europe in 1941, blessedly oblivious but potentially insidious to a 5-year old boy in 1978.

Within Tintin fandom you can find all the strands of opinion you might expect – the loyalists who take Herge’s line that the book’s anti-Semitism is accidental; the majority who consider it a regrettable lapse in an otherwise fine book, or simply feel it doesn’t matter and wasn’t it all a long time ago. And a few who think the book is a blot on Herge’s career. (Those who feel it damns the entire Tintin enterprise are presumably not in the fandom in the first place.) How do I feel?

I read the book when I was five. Re-reading it now, its setpieces are as striking and resonant as ever. The comic is an outlier in the Tintin canon, one of the few books where the uncanny – always lurking in Herge’s work at the edges of adventure, in dreams or as implications or as a mystery to be solved – bursts through the skin of the story. The book starts and ends with wonder – a world burning, then flooded; and an island of transformed science which exists only for a few hours. Herge, for all the buttoned-down repression his cool lines suggest, could be the most psychological of cartoonists. His affinity for the quiet comforts of the bourgeois world, struggling with his storyteller’s instinct to breach them, made him unusually good at capturing disquiet and upset. No wonder his wartime books are so strange and strong.

Perhaps my lifelong attraction to the mood of a comic begins here, in the panels set in the glow of the meteor’s approach, where the solidity of Herge’s universe begins to literally melt: faithful Snowy becomes stuck on a road of liquefying tarmac; the light and line becomes starker and sharper, and the characters’ shadows themselves become sticky and treacherous. Comics have so many ways of capturing feeling like this, of conveying interiority through how they show the world’s exterior. The crisis passes, of course: Tintin learns the world is safe in the most comically bourgeois way possible, via the Belgian speaking clock. In the midst of upheaval, order prevails.

But that’s the danger of it. A common twentieth-century British fantasy – perhaps it still is one – was to imagine what we might have done ourselves under Nazi occupation. Nobody chose collaborator. Mostly we imagined ourselves in a heroic role, more or less – if not as an actual resistance fighter, then at least hiding Jews, sneaking messages to the Free British, weighing out butter and boiled sweets to the occupying troops with a very English frost. This last agrees with the grim statistical likelihood of occupation: resenters would have been far more common than dissenters. But what good do resenters do, really?

Herge was not a collaborator. But The Shooting Star is a collaboration: an acceptance – inevitable, its defenders would say – of the realities of occupation, a newly disturbed world. Certain prejudices become more acceptable. Certain ones become less so. Certain dreams endure – both sides loved their scientists, after all. The Shooting Star takes all of this on board – how pragmatic it is – makes a quiet bet on the status quo, and reflects it in its choice of villain.

That is its lesson. It’s a beautiful, exciting, seductive comic, which is also a reminder – because, thank goodness, it lost that bet – of how casual and thoughtless acquiescence is. Because it’s so beautiful and exciting, it isn’t an easy reminder. It’s not a Tintin In The Congo, an evil comic which is also a bad one, hence simple to deplore. The Shooting Star is a splendid comic, its evil a subtle ripple, an answer to a single question, who is my villain, that’s as much lazy as bad. The Nazis are gone. The question – who is my villain? – has not. I gave The Shooting Star to my five year old son to read – he adored it. Why wouldn’t you? Because he adored it, I write this, for him to read later.

NEXT: May 1979. Greed is good, Fleetway hits the Jackpot.

Yes, You Do Mean Me

People I know will talk at length about how ridiculous and over-sensitive and overly angry they think feminists are, or social justice activists more generally, and often expressly refer to specific views I share or groups I’m a part of, but, “well, obviously we don’t mean you.” They don’t mean me because I’m not confrontational, I’m not argumentative, I stay quiet and let everything slide because direct confrontation is something I really struggle with. They don’t mean me, even though if I spoke my mind more often, they’d know they do mean me.

They don’t mean you, yet, they just want to check you’ll laugh along and keep the part of you they clearly do mean out of their sight.

They don’t mean you as a disabled person either. Certainly, when misogynist and/or ableist trolls came after the NUS Women’s Conference for using BSL applause to accommodate various disabilities, “well, obviously none of them meant you” although, being autistic and hypersensitive to sound, I’m amongst the people who would benefit, and my friends often end up making very similar accommodations for me, albeit on a smaller scale. People, even those who campaign for social justice and claim to strive for intersectionality, make sweeping catch-all criticisms of people who don’t follow a healthy enough or ethical enough diet, who spend a lot of time online, who didn’t vote* or go to a protest or something else which involves being able to leave home and get to another place that may be inaccessible in any number of ways, and when someone points out the inherent ableism in that and how it affects them personally… “Well, obviously we don’t mean you.” Sometimes that’s also accompanied by a thorough assessment of whether the individual in question tried this, tried that, tried hard enough, or whether they actually really genuinely have a good enough excuse.

They don’t mean you, so long as your disability and your experience has their approval. They don’t mean you, but all these other disabled people need to just try harder, or also come forward as individuals and hope they’ll be believed. They don’t mean you, as long as you’re in a position to willingly disclose your disability in demand. They don’t mean you, unless your invisible disability hasn’t been spotted or diagnosed yet, because everyone’s abled by default, right? They don’t mean you, they approve of your excuse so they don’t have a choice about it, it’s not your fault you’ll never be as good as your abled peers in their view.

Believe me, “well, obviously we don’t mean you“ doesn’t make a jot of difference to those of us who have to put up with this stuff from all angles, day in day out, always the afterthought they didn’t really mean. Unintentional harm does happen, and in a society where oppression and exclusion is so widespread it goes unnoticed, I’d go so far as to say it’s inevitable that we all cause unintentional harm at some point, but that doesn’t make it any less harmful. We need to learn from our mistakes, take care not to repeat them in future, and apologise where necessary; getting defensive and claiming we never meant you doesn’t solve anything.

Because when faced with the reality that their ideologies are hurting actual real people, they never mean you. They just mean everyone else like you, and they expect you to be okay with that.

*Just so we’re clear, I managed to arrange a postal vote on time, used it, and felt it was important for me to do so, but that doesn’t mean I’m a fan of blaming non-voters, even where it was by choice – it’s not something I want to get into here though, so I’d recommend reading Stavvers on the subject instead.

Guest post: How To Win The Fightback

However, the first step must surely be to admit where we went wrong. Going into a coalition in itself was not a mistake as it showed we were prepared to put our money where our mouths were. But we voted through so many awful policies, such as tuition fees and secret courts that we should have blocked, while allowing the Tories to veto all the key reforms we proposed - electoral reform, Lords reform and minor changes to the treatment of drug users.

Giving up our historic position as a party on the centre left who back well-funded public services along with a strong commitment to individual freedom, and swapping it for a vague, mealy-mouthed, neither one thing nor the other approach was also intellectually weak and tactically inept. When I spoke to voters on the doorstep over the election period, many naturally Tory and Labour voters who had previously lent us their vote said they would be unable to this time for fear that we put the other ‘lot’ in. To regain the trust of voters we must be prepared to stand up for what we think and what we would achieve in Government, not just what we would try to block.

Our current obsession with cutting taxes must also surely now come to an end. Not only does it go against the fundamental principles of progressive liberalism to continually want shrink the state, it is economically illiterate. By continually ‘taking people out of tax altogether’, not only do we take away people’s stake in the public services they use, but we have also punched a huge hole in the UK’s income tax take, thus worsening the structural deficit that those supporting tax cuts claim to want to cure. The misguided Tory pledge to enshrine 'no tax rises' in law naturally creates the space for this debate.

We must also reverse the process of watering down our policy commitments; if the swing to UKIP tells us anything, other than a huge dissatisfaction with modern politics, it is that voters like politicians who say what they think, rather than say what is acceptable to focus groups. The Liberal Democrats used to back the legalisation of prostitution and of soft drugs, for the obvious reasons that it is not the role of Government to ban personal activities, but merely to regulate them properly to reduce harm. But the former is now never mentioned at all and the latter has been replaced by a commitment to stop treating drug users as criminals and start treating them as patients.

The road back to relevance and power will clearly be a long one, but rediscovering our soul and purpose must be the first step. I dearly hope that under Tim's leadership, the points I make above can be addressed. If they are not, I fear for the future of our party.

Nic Bourgueil is a Lib Dem member and former member of staff in London, writing under a pseudonym for work reasons and expressing a personal view.

Thoughts on the Lib Dems: Past, present and (hopefully) future

This is a long post – the version in my head is even longer – but it’s been gestating in various forms for a while and I wanted to get it out there while we’re thinking about the future of the party. To make it slightly easier, I’ve divided it into three parts – the first about the decisions the party made about its political positioning before 2010, the second about the decisions made with coalition and the effects they had, and the third about where we go from here.

This is a long post – the version in my head is even longer – but it’s been gestating in various forms for a while and I wanted to get it out there while we’re thinking about the future of the party. To make it slightly easier, I’ve divided it into three parts – the first about the decisions the party made about its political positioning before 2010, the second about the decisions made with coalition and the effects they had, and the third about where we go from here.

Part 1: How did we get here?

‘Those who do not understand history are condemned to repeat it.’ If we’re going to look at where the party should go from here, we need to look at the process that brought us here, and for me that starts in the mid-90s as the party abandoned equidistance in favour of working more closely with Labour. Up until that point, our positioning had been best known by Spitting Image‘s Ashdown catchphrase: ‘neither one thing nor the other, but somewhere in between.’

However, after the shock of the 1992 election and the travails of the Tory Government that followed it, Paddy Ashdown began the process of shifting the party into being part of the anti-Tory bloc. This was rewarded with lots of tactical voting that led to the big by-election gains from the Tories, and also the party’s gains at the 1997 and 2001 general elections, only one of which (Chesterfield in 2001) came from Labour.

Things shifted after 2003 and the Iraq War. The party had already begun picking up council seats and councils from Labour, while losing ones gained before 1997 back to the Tories, but this accelerated, particularly in the North, culminating in a number of gains from Labour (and losses to the Tories) at the 2005 general election, coupled with a failure of the ‘decapitation strategy’ against senior Tories whose seats were perceived as vulnerable. After this, and particularly once Clegg became leader, the party began to move back towards ‘equidistance’.

That’s a simplified version of the strategy – there were lots of other currents going on at the same time – but I want to talk about it in general terms instead of getting bogged down in the details.

There’s a concept in the academic study of party systems, introduced by the late Peter Mair, called the structure of competition for government, which underlies other issues of the party system within a country. Part of it covers the way parties work together even while competing with each other in the electoral system. For example, in Sweden there are clearly separate left and right blocs of parties who tend to alternate with each other in government but a party from one bloc will not go into government with the other, while in the Netherlands, there are no clearly defined blocs so shifting between parties in government after elections is more fluid.

Britain’s post-war structure of competition was seen as being a very closed one, with just two parties competing for Government, and power alternating between the two. It had wobbled in 1974 and through the Labour government that followed, but reasserted itself in 1979. However, it broke down again after the 2010 election result, and we took the opportunity of that change to enter Government and formed the coalition with the Conservatives.

In the minds of many in the party, this was entirely natural decision. After all, we’d gone back to being equidistant between the parties, so we were free to choose whichever way we wanted to go, and there was no real way of forming a stable coalition with Labour. However, what I’d argue is that we catastrophically misjudged the mood of the public and their understanding of how the party system and structure worked. In their minds, we were still part of the anti-Tory bloc and so to line ourselves up with them was breaking our role in the system.

We’d convinced ourselves that returning to equidistance was right, but we’d failed to get that message over to the electorate – and indeed, our message to the electorate completely ignore that. In so many of our constituencies, we were fighting the Tories and putting out the message ‘vote for us to keep the Tories out’. Because the bulk of our seats were Tory-facing that’s the message the bulk of our voters got.

We also failed to notice that equidistant parties are incredibly rare in all political systems. People like to point at Germany’s FDP, but neglect to notice that they’ve only ever been in coalition with the SDP once, and that was over thirty years ago. The rise of the Greens as the SDP’s natural partner on the left since then made them a natural part of the CDU’s right bloc, not an equidistant party that can shift between the two of them.

There was a mismatch between the way we (especially the leadership) saw ourselves and the way our voters saw it. Joining coalition with the Tories exposed that rift.

Part 2: What the hell just happened?

It’s very easy to look back on May 2010 with 20/20 hindsight and imagine that everything that’s happened since then was entirely predictable. What we forget is that at the time nothing seemed predictable as the voters had delivered us into an entirely new political situation. Everyone was wandering in the dark and trying to guess the rules of this new political landscape, while the media – denied of the clear election result they expected – were howling at everyone to get on with it and give them something to report so they could move on to the next thing.