| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | September 24th, 2014 | next | |

|

September 24th, 2014: YOU GUYS, Todd emailed me to let me know we all forgot to change the footer here to the summer version, and now it's fall! And yes I absolutely said "we all" there as a way of diffusing blame across every single person who reads this comic. Anyway, it's too late for summer, but just in time for fall, so that's what we've got now. It's a really pretty fall scene that you can see if you scroll down to the very bottom of this page on a non-mobile device, THE END. – Ryan | |||

Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

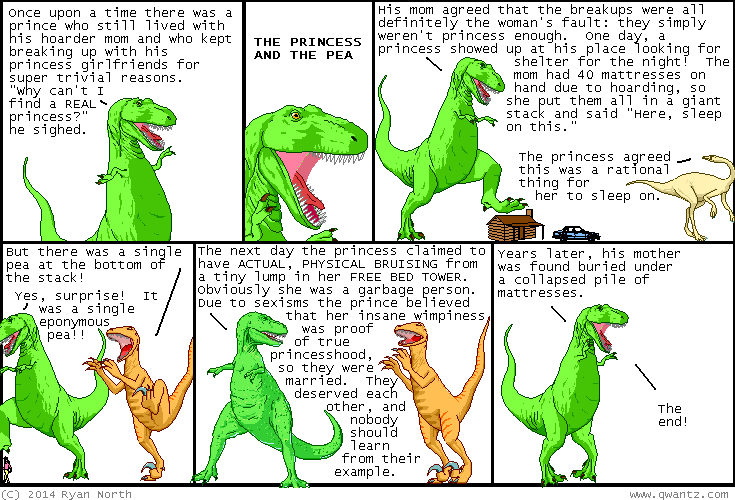

my choose-your-own-adventure version of this story is called "the princess and/or the pea"

Are party members more radical than their leaders?

It’s party conference season, and one of the common stories of that period always used to be of the party leadership (and it didn’t matter which party) facing down the activists in their party. The ‘activists’, we would be informed, would want a policy way out of the mainstream while the leadership was being sensible and moderate. The reason I don’t specify a party there is because it’s a common story based on a common assumption: that the activists within a party are much more radical than the party leadership, and if the party wants to be successful (and appeal to the electorate, which is assumed to be moderate) the activists have to be faced down and/or defeated.

Now, there are two parts to that assumption. First, the difference between party leaderships and activists/members and second, the idea that a party being more moderate will get it more votes. This post is going to look at the just the first one and assume the second as given, but we’ll look at in more depth in a post another time (look out for me talking about spatial models and Downsian theories).

The issue we are talking about is known as curvilinear disparity, or to give it its full name, May’s Special Law Of Curvilinear Disparity. The diagram to the left gives a pictorial representation of it – leaderships and supporters are more moderate, and activists more radical, thus further from the centre. Why is this thought to be the case?

The issue we are talking about is known as curvilinear disparity, or to give it its full name, May’s Special Law Of Curvilinear Disparity. The diagram to the left gives a pictorial representation of it – leaderships and supporters are more moderate, and activists more radical, thus further from the centre. Why is this thought to be the case?

The main explanation is that party leaderships and activists are thought to have different goals and reasons for being involved in politics. The primary goal of leaderships is thought to be office-seeking while activists are said to be policy-seeking. That is, leaderships are more concerned with getting into power (and thus moving towards the centre to get them the votes to do that) while activists are concerned with issues of policy, and more concerned with ideological purity than moving to the centre. Meanwhile, ‘below’ this fight, the less active members and supporters are held to be in roughly the same position as the leadership. So, you can draw a curve from the leaders down to the members that swings out from the centre to represent the position – hence, curvilinear disparity.

So, political science, political journalism and party leaderships all agree on something, which means you won’t be surprised to find out that when researchers have actually looked in detail at party members and leaders and whether their attitudes differ they’ve found little or no evidence to support curvilinear disparity. Indeed in some cases, they’ve found that party leaderships and elites have had more radical ideas than members, who’ve tended to be more centrist.

So why does the idea persist? I’d give two reasons: first, it’s useful for party leadership to be able to send out signals that they’re standing up to the activists to be sensible and moderate. Whether they are or not, they want to send that signal out to the electorate as a whole to show that they’re positioned near the centre, and picking on the activists is a good way to do that.

Second, my personal theory is that there’s a perceptual bias at work. All political parties contain a range of opinions and it’s a rare party that can find a leadership that reflects all strands of opinion within a party. However, I would hold that a party leadership would be more likely to reflect the ‘moderate’ strand of opinion within the party because the ‘moderates’ are more likely to include a majority of the party membership. The ‘radicals’ are thus the members of the party least likely to be represented by the leadership and so are the most likely to complain and be visibly in opposition. However, they are not a majority of the membership, and neither is their position the average of the entire membership, rather it is the average of the non-represented membership – which almost by definition is unlikely to be a majority, as if it were, it could replace the leadership – but it is more visible, and this gives the impression of a ‘leadership vs activists’ battle.

I still need to work out that explanation a bit more, but it feels like a workable explanation for me, but the main point to take is that while many do believe that curvilinear disparity is real, the evidence collected thus far doesn’t support the case for it (for instance, see Pippa Norris in the first issue of Party Politics, if you have access to academic journals – sadly, most of the arguments and evidence about this is in journals). The battle of leaderships and activists is not a fundamentally existing part of party politics, no matter how much people tell you it is.

National Railway Museum stages controversial exhibition... on trainspotting

From York Mix:

“We’ve not tackled anything quite like this before,” is the first thing Amy Banks says when asked about the National Railway Museum’s brand new project.

“It was quite a controversial subject that we realised we needed to talk about. We wanted to get across a sense of travel and adventure. That desire to record and document what’s happened”.And what is the controversial subject the NRM is tackling? Trainspotting.

Time I think to reprint a column I once published in Clinical Psychology Forum as Professor Strange...

******

Trainspotting, autism and what it means to be normal

Saturday afternoon on Platform 1. Freight trains and passenger trains coming and going. My notebook filling with engine numbers. The packet of sandwiches that Mother made me. The summer sunshine burning my bare knees. An excited shout goes up. I rush to join the throng and taste again the oily tang of steam.

Yes, I enjoyed my visit to York last Saturday and may well go again this weekend. Yet when I look around me, I see that trainspotting is thoroughly out of fashion.

I do not refer to the adventures of Begbie, Spud and Sickboy: they are very much in fashion. Though, as I said in my review in Steam Railway Quarterly, anyone who watches the film of Mr Welsh’s book in the hope of gaining an insight into the operation of Gresley’s A4 Pacifics on the LNER is likely to be sadly disappointed.

Rather, I refer to the hobby which enthralled generations of schoolboys. It flourished in the decades after the Second World War as families became affluent enough to spare the cash for their children to explore the railway system.

That sort of trainspotting is more than out of fashion: it is rapidly being turned into a mental illness. The other day I was looking at a piece on the narrow gauge railways of North Wales written by Bill Bryson. He said: ‘I had recently read a newspaper article in which it was reported that a speaker at the British Psychological Society had described trainspotting as a form of autism called Asperger’s syndrome.’

It is just as well that he or she did not describe it in those terms in my hearing, but we have come far from the days when boys were expected to be interested in trains. I can recall, as a young practitioner, having families referred to me because the son did not want to be a train driver when he grew up. ‘We’re at our wits’ end, Doctor Strange,’ the tearful parents would say. ‘We have tried everything, but he’s just not interested in railways.’

I was able to reassure them, puffing on my pipe, that it was just a phase the lad was going through and that they should not worry too much – though some parents had found Strange’s Herbal Supplements™ wonderfully efficacious in similar cases.

Not that trainspotting was without controversy. Popular stations could be overrun with children in the holidays. Questions were asked in the House about problems at Tamworth, and when overzealous spotters were picked up wandering around locomotive depots, magistrates would call for the hobby to be banned.

Yet it is not the criminogenic properties of trainspotting that have led to its decline, nor has it been the result of advances in the understanding of autistic spectrum disorders. In part it is because we are all – children included – far too cool to be interested enough in anything to call it a hobby. And in part it is because there has been a change in our idea of what it means to be normal.

When I was young, to be normal was to be male, white and upper middle class and to wear a tweed jacket and smoke a pipe. I must say that always seemed perfectly reasonable to me, but as I was male, white and upper middle class, wore a tweed jacket and smoked a pipe, I suppose it would.

Today to be normal is to be female and quite often it is to be a mental health professional too. Just think of the articles which treat a willingness to take part in workshops as a sign of normality in psychiatric inpatients when this activity plays no part in the lives of 99 per cent of the population.

So ‘normality’ is a slippery concept, and what it means has changed markedly over the years. That is why I have never made any great efforts to appear normal myself.

******

That's quite enough from Professor Strange, but for more on trainspotting I recommend the book Platform Souls by Nicholas Whitaker. In a just world it would have done for the hobby what Fever Pitch did for football.

Fruit for Crows

If it has an Ur-Image, if it has a Defining Moment the way that the national memory switches to color after the Kennedy assassination, it is the savage beating of Rodney King by L.A. police officers in 1991. The footage seems crude, noisy, and primitive by the standards of today’s video technology, so tiny, so compact and portable, so capable of showing us extravagant cruelty in high resolution, and yet it offers us moments of shocking clarity: King, caught like a freshly caught fish flopping on the dock by filaments of electric shock weapons; Officer Stacey Koon, directing traffic, maintaining order so that everyone gets a chance to flail away at King’s flattened, bloody form; the savage kicks to the back of the neck, delivered by people who set out to harm; the way the beating goes on for three agonizing minutes, even as cars crawl past to watch the show, until King is finally deposited off by the side of the road like a piece of trash and trussed up like a Christmas goose. Of course, it was nothing new; it was not the beginning of anything, or the end of anything. What made it different was that everyone saw it, but even so, it turned out not to be a Moment, but merely a moment.

It should have meant something, coming as it did at a unique historical moment, a concatenation of American issues that included war and imperialism and drug interdiction and unemployment, political indifference and police brutality and militarism and violence and crime and the inner city, and how all those things became so much worse when they were applied to the black community. But it didn’t. All it meant was the bringing to bear of a new technology in the service of recording an injustice no one seemed to care much about; all it taught us was to what lengths people will go to doubt what’s right in front of their eyes if it allows them a moral excuse for destroying black lives; all it left behind was a riot that, somehow, became a justification for what led to it, an injustice so great that it blotted out its proximate cause. It would happen again in front of newer and better cameras, just as it had happened before in front of older film cameras showing us a black man being blown across a street by a water cannon for asking after his right to vote, in front of a still photographer as the bloated and mangled body of a young black man was fished from a river for reckless eyeballing, in front of sketch artists drawing gathered mobs of laughing, hooting white men staring gleefully up at a lynch victim who had not crossed to the correct side of the road. And before that, it would happen in memories. I got to hear a few of the memories.

The story is told pretty much the same by everyone in my family; the only difference is the tone of approval, betraying the sympathies of the storyteller. In these details it never wavers: one evening in a small mining town in Alabama, sometime in the 1930s, my maternal grandfather is sitting on his front porch, alone and angry over some perceived slight. A black man strolls past the house. My grandfather picks up the hunting rifle that is propped up next to him, aims recklessly, and fires, putting a bullet in the side of an innocent passerby who has said nor done not a thing to him. Wounded and terrified, the black man runs off, leaving a trail of blood streaming behind him; whether he lives or dies is irrelevant, as he is no longer a part of this story. He never even has a name. Who he was and what happened to him is unimportant to anyone but his own family, and who cares about them? They’re just another bunch of niggers dumb enough to be kin to a man without the good sense to avoid walking through a white neighborhood after dark. My grandfather grabs a lamp from a small table on the porch, saunters over to the largest pool of blood, and throws it to to the ground with force; it shatters and provides him with an alibi that the coon was thieving, in case it ever comes back at him. He needn’t have bothered; the black man is never seen again, and my grandfather is a railroad dick (practically a cop), and, of course, a respectable white man. When this story is told, it is about even odds whether the family will sadly disapprove of what the old man did or laugh as they tell it, placing him in the role of a roguish scamp, I never met the old man, and I’m glad.

***

Here are some things you must do or not do if you want to stay alive, we tell our black citizens: do not ever commit a crime, no matter how petty, any time in your life. In any encounter with the police, do your best to behave as a soulless automaton, stripped of any volition or dignity, of the very suggestion that you are a human being cognizant of your rights under the law. Do not speak, move, dress, or behave unusually or unexpectedly. Do not buy anything that might alarm a white person, no matter how legal or harmless. Do not respond to any provocation of any kind, ever. Do not ask to be treated fairly; certainly do not demand it. Do not wear a Halloween costume; do not get in a car accident; do not walk around at night. Recognize in all white people moral authority, and in yourself moral culpability, at all times. Do not go to a place where you might not expected to be, even if you are invited. Make sure you have a biological mother and father that you live with, who are married to one another, and who share the same surname. Do not look like another person of your race who might have done something wrong. Do not, ever, become upset about anything. Do not live near white people, but do not gather in groups with your own. Try to arrange it so that your actual physical body is not taller, younger, heavier, more fit, or more adorned than any white person with whom you might come into contact. Do not carry a gun, legally or not. Avoid any expression of your own culture as if it were a particularly virulent plague. Do not ever drink. Do not ever take drugs. Do not ever be loud. If you do all these things, always, as long as you live, you may feel yourself so reduced in the basic qualities of humankind that you think yourself still a slave, or worse, a herd animal, but at least there is a chance you will not be killed. If you are, though, rest assured that whites in their thousands will make a moral example of you to your people, reminding them of other things that they must not do. Then they will start a charitable drive to lessen the burdens of the man who killed you.

If you are a white person, try to imagine your life if it were demanded that you behave in such a way every day for the rest of your life, under the very real threat of death. It’s harder than you think; millions of people literally cannot conceive of it.

***

Since the Rodney King moment, we have seen a man beaten to death by deputies in Allegheny County, PA; a 10-year-old boy shot by police for playing with a toy in Brooklyn, NY; a man shot to death by transit police for no good reason in New York, NY; a man shot dead by police while reaching for his wallet in the Bronx, NY; a man shot dead by police for opening a door in New York, NY; a man shot dead by police for driving a car that looked like one that had been stolen in Queens, NY; a man shot dead by police while driving past a stakeout in New York, NY; a man shot dead by an undercover policeman attempting to entrap him in New York, NY; a man shot dead by police returning home from his bachelor party in Queens, NY; two men shot dead by police while fleeing a hurricane in New Orleans, LA and another murdered by the police and his body burned; a man shot dead by police for sticking his hands in his pockets in Champaign, IL; a man Tased and run over by a police car for having no safety light on his bicycle in Pensacola, FL; a man shot dead by transit police while lying face down at a train station in Oakland, CA; a little girl shot dead by police trying to arrest someone else who lived in her building in Detroit, MI; a man shot dead for wielding a cell phone in Chicago, IL; a man beaten into a coma by police in Philadelphia, PA; a man shot dead by police for being the victim of a home invasion in Brooklyn, NY; a woman suffocated by police for being mentally ill in Queens, NY; a man shot dead by police after having been falsely accused of a crime in Pasadena, CA; a man beaten to death by police nightsticks for being drunk in Lake County, IL; an autistic man shot dead by police for no reason at all in Los Angeles, CA; a woman shot dead by police while gathered in the park for a party in Chicago, IL; a man shot dead by police hunkered in a tiny bathroom in New York, NY; a man shot dead by a security guard who was harassing his sister in Atlanta, GA; a man shot dead by a ‘neighborhood watch officer’ who was stalking him home from a convenience store in Sanford, FL; a man shot dead by a homeowner after being caught underage-drinking in Slinger, WI; a man shot dead by a software designer for playing his music too loud in Jacksonville, FL; a man shot dead by police after being in a car accident in Charlotte, NC; a woman shotgunned to death after being in a car accident in Detroit, MI; a man asphyxiated by police while being arrested for selling untaxed cigarettes in Staten Island, NY; a man shot dead by police for no discernible reason in Ferguson, MO; a woman shot by police for being in the proximity of two men fighting in Bastrop, TX; a man shot dead by police after buying a toy in Beavercreek, OH; a man shot to death by police while lying face down in the street in Los Angeles, CA; and a man shot by police while delivering pizzas in Philadelphia, PA. This morning I am greeted with the news of a man repeatedly shot by a state trooper, with whom he was visibly cooperating, after being suspected of driving without a seatbelt; the only thing that sets his story apart is that he lived.

There are many differences; the victims range in age, they are men and women, they are geographically spread out. Sometimes their killers were police, other times they were ordinary citizens; some of their killers paid for their crimes in time or money, while many were not punished or even charged. The only commonalities are these: all the victims were black. All the killers were white. And none of the victims were armed. There are more than just the ones I listed, of course; so many more, I could not possibly find them all. So many more, and more every day; more than there were lynchings. And these are just the ones where the vast majority of the facts are not in dispute; it does not count any where the victim was shot during the commission of a serious crime, or where the victim was armed or fought back, or even where the police claim the victim was armed or fought back. And, of course, it only covers the stories deemed important enough to make the national news. It’s all I could list before growing tired of it all, soul-sick and frustrated. I try to imagine how it’d feel if I were black.

***

Always when I write entries like this, I say there is hope. I say that it is better to know than to not know, to talk than to not talk, to speak out than to say silent. But I’m getting tired. I reckon that 40 million of my countrymen, with every right under American law but born black, have been good and fucking sick of it since the day they were born. I’m tired of making excuses, and I’m tired of patches instead of fixes, and I’m tired of a new name being added to the rolls day after day and having to track the course of a justice I know will never come, and I’m tired of apologizing for nouveau-rights libertarians who blame the symptoms (bad training, militarization, police overreach) while ignoring the real cause. And what’s the real cause? The same one as it ever was, the one they precede with “lost” down South, or spell with a capital C. It’s that ugly alliance made at the founding, between the two things America has embraced like no others: racism and capitalism. I’m sorry, black Americans: we only ever wanted you for one thing, and when it happened that we couldn’t have that thing anymore, we started treating you like we never wanted you at all. Ever since then — ever since Lincoln made the understandable but perhaps questionable decision not to pursue a de-Confederatization program in the South, ever since John Wilkes Booth spoiled forever any chance at real reconciliation, and ever since the moneymen of the North decided that reparations would be far too costly to their bottom lines — it’s been a race to either recreate the conditions under which we brought you here, or just get rid of you altogether. The former tactic has seem a lot of success in recent years; the decay of the inner cities, the de-industrialization of the American economy, the death of labor unions, and the vast overreach of the Drug War and the security state have done a lot to return blacks to the state of a permanent source of nearly free labor, as have the institution of everything from payday loans to bail bonds to the disappearance of social welfare to the growth of a for-profit prison system to wage stagnation. But in a pinch, you can never forget the latter, and we seem to have learned the lesson well that you can get rid of lynching in name only by just outsourcing the job to law enforcement. The decision was made a long time ago, at a level neither I nor anyone reading this has access to, that we needed the South on our side to be a real country again, and that the feelings of all the white bigots in America were worth more (financially, of course) than the feelings of all our black people. And that settled that.

So what can be done? What hope is there? Dash cams and demilitarization? Civil suits and sensitivity training? More and more I think that those are just sops for people like me, people who don’t have a pre-made list of excuses every time a cop puts a bullet in some unarmed kid’s brain and are looking for reasons to be hopeful. For anything to really change, we’ll have to stand up to the unholy alliance of bigotry and capital, to break the cycle where we tolerate racism as long as it throws money in the right direction. And how are we gonna do that? We haven’t even gotten the minimum wage to budge in five goddamn years. All I can suggest at this point is that you hit the Lotto and move to Europe; anything else seems to be an increasingly grim and hollow joke. So good luck on them numbers; otherwise, you’re on your own.

Once More With Feeling?

There's an extent to which the 'it won't work' critique is entirely valid as an objection to waging yet more war upon the Middle East. Because the surface aim of the politicians is almost certainly to impose 'stability' on 'the region'. They like stability. No threats to embarass them, no revolts to topple their friendly dictators, no threat to Israel, no danger to neoliberal exploitation of local resources and markets, etc. And, as has been shown, it doesn't work. They try and try to bomb the Middle East into passive compliance, and all they succeed in doing is generating more troubles for their empire.

This is, of course, what empires have always done. Create the problems of tomorrow by viciously conquering the problems of today.

But there's another sense in which the 'it won't work' argument is fatally flawed, because there's a sense in which it does work. It may never achieve 'stability' but it does keep the machinery of empire chugging, and the fuel of empire flowing. Because the fuel of empire is as much war itself as the resources extracted via war. The neverending war keeps the military-industrial complex in work, the contracts coming, the factories producing, etc. It keeps the corporate media busy and happy, reporting yet more incomprehensible strife from 'over there' and 'our' attempts to make things better. It keeps the endless circular debate about intervention circling (the system can tolerate a tortuous and muddled debate, what it doesn't want is clarity). It keeps the public money flowing into the vast state run apparatus of military spending, and into all the R&D that is done under the aegis of this and then handed over (free) to private enterprise. It keeps the empire's power and prestige in the ascendant, with the machinery of death inspiring the fear - and projecting the apparent invincibility - that every empire needs.

No, the war never 'works' in the sense of achieving a stable imperium, but it does 'work' - at least in the short term - in achieving a powerful empire. One of the paradoxes of empire is that its power relies upon it never being stable. So even when the bombing doesn't work, it actually does.

Meanwhile, of course, people die. And die and die and die.

Nick Clegg's case for military action in Iraq

In his email to Liberal Democrat members - kindly reproduced by Lib Dem Voice - Nick Clegg gave three reasons why we should support renewed military action in Iraq:

- the threat from ISIL to Britain has already been made clear by the sickening sight of British hostages being executed on television;

- unlike the 2003 war in Iraq this intervention is legal – we are responding to a direct request for help from the legitimate Government of Iraq and Parliament will vote before any action is taken;

- we’re acting as part of a broad coalition of countries, including many Arab countries, to deal with a real and immediate threat.

And point 1 does not convince me. ISIL is an appalling movement, but it surely poses more of a threat to the Kurds and the Yazidis than it does to Britain. And as far it does pose a threat to Britain - seizing hostages, fomenting terrorism here - it is not clear that bombing will reduce that threat.

I am not a pacifist and will support humanitarian military action if it is clear what the goal is. But is it clear in Iraq today? Are we looking to contain ISIL or destroy it? And is that latter idea any better than a fantasy?

More than that, I think that Western leaders have lacked a strategy in the Middle East. We are afraid of the rise of Islamism, yet we have swept away the dictators who acted as a bulwark against it - Saddam Hussein, Gaddafi and there were plenty who wanted to bomb Bashar Assad only last year.

At one time we were seeking a rapprochement with Gaddafi - one of the very first posts on this blog made fun of Tony Blair's meeting with him. But we seem to have concluded that both sides are pretty appalling and fought both in a piecemeal fashion.

And our leaders seem to lack historical perspective. Compare that with Paddy Ashdown, who recently wrote:

What is happening in the Middle East, like it or not, is the wholesale rewriting of the Sykes-Picot borders of 1916, in favour of an Arab world whose shapes will be arbitrated more by religious dividing lines than the old imperial conveniences of 100 years ago.That is surely right. Have we really gone to war to defend those borders?

Still, have a look at the video of Nick Clegg and decide for yourself. His arguments there are more developed and more convincing than those in his email.

When did 'offence' become a trump card?

Lord Bell was Hilary Mantel investigated by the police because she has published a short story about Margaret Thatcher.

It has not been a good week for supporters of free expression in the arts.

A protestor against Exhibit B is quoted by the BBC as saying:

"It's not educational, it actually causes huge offence."Meanwhile, says the Guardian:

Tory MP Conor Burns told the Sunday Times that the story represented a grave offence to the victims of the IRA.It seems the merest Tory backbencher has learnt what left-wing activists have long known: if you can claim 'offence' in modern Britain, that is a trump card.

How and when did that come about?

An Anti-Feminist Walks Into a Bar: A Play in Five Acts

PROLOGUE

And thus did the number of women calling themselves "feminist" rocket. RT @DawnHFoster: LADIES. MAKE YOUR CHOICES. pic.twitter.com/512S3JAYeE

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

ACT I

GUY: I WILL NOT DATE YOU IF YOU ARE A FEMINIST Woman: Great! Thank you. GUY: YOU ARE NOT SUPPOSED TO REACT THAT WAY Woman: Oh, but I AM.

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

ACT II

GUY: OH HEY THERE BABY YOU LOOK LIKE YOU COULD USE COMPA- Woman: I'm a feminist. GUY: NOOOO THE BURNING MAKE IT STOP (flees) (Woman smiles)

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

ACT III

GUY: HEY THERE BAB- Woman: Feminist. GUY: LIKE A REAL FEMINIST OR ARE YOU JUST TRYING TO GET RID OF ME Women: Why not both?

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

ACT IV

GUY: HI THER- Women: Feminist. GUY: THIS WHOLE BAR CAN'T BE FULL OF FEMINISTS (Every women in bar nods) GUY: HAS THE WORLD GONE MAD

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

ACT V

GUY: I STRUCK OUT AT THE BAR BUT I HAVE THIS LOTION AND MY HAND Guy's Hand: Feminist. GUY: OH COME ON Lotion: Me too. GUY: NOOOOOOOO

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) September 25, 2014

fin

Prologue

The following documents are transcripts of Time Girls DVD commentaries and cast interviews. They tell, in impeccable Received Pronunciation, the silly story of a rubbish 70s/80s science fiction series, and the serious stories of the actresses whose lives it blighted.

The story comes with a CONTENT WARNING because it deals with sexual violence and mental illness. These issues will be skirted around until the denouement, when the tone will change significantly. There won’t be any jokes directly about these things.

You should also be warned that this is an experiment in breaking some of the “rules” of writing. If you want a gripping page-turner where lots of plot happens and every detail is relevant, don’t bother reading any further.

Transcription Conventions

- italics = stressed word

- CAPITALS = loud

- (CAPITALS IN BRACKETS) = stage direction

- word- = speech cut off by next speaker

- … = pause longer than a full stop

The story begins in the next post.

Neil Gaiman explains, Terry Pratchett isn't jolly. He's angry.

DALEKS 1997!

Starting in Doctor Who Magazine No.249 (12th March 1997), The Daleks ran on the inside front cover for six issues. It was written by John Lawrence and illustrated by veteran artist Ron Turner, who had been one of the original artists on the TV21 strip. Some of the Dalek figures were a bit 'off model' but it didn't matter, - Ron Turner was still producing stunning artwork even at 74 years of age!

Here are the first two episodes of the revived Daleks strip. It's a shame it didn't run for more than six issues, but the fact that a new series of strips happened at all is something to be thankful for. The comic series concluded in a similar way to how the original TV21 run had, with The Daleks intent on reaching Earth, presumably acting as a prequel to the 1964 Doctor Who TV adventure The Dalek Invasion of Earth.

Sadly, Ron Turner passed away in 1998, just 18 months after this run of strips, but his work lives on for fans old and new.

Microsoft SVC

By now, the news that Microsoft abruptly closed its Silicon Valley research lab—leaving dozens of stellar computer scientists jobless—has already been all over the theoretical computer science blogosphere: see, e.g., Lance, Luca, Omer Reingold, Michael Mitzenmacher. I never made a real visit to Microsoft SVC (only went there once IIRC, for a workshop, while a grad student at Berkeley); now of course I won’t have the chance.

The theoretical computer science community, in the Bay Area and elsewhere, is now mobilizing to offer visiting positions to the “refugees” from Microsoft SVC, until they’re able to find more permanent employment. I was happy to learn, this week, that MIT’s theory group will likely play a small part in that effort.

Like many others, I confess to bafflement about Microsoft’s reasons for doing this. Won’t the severe damage to MSR’s painstakingly-built reputation, to its hiring and retention of the best people, outweigh the comparatively small amount of money Microsoft will save? Did they at least ask Mr. Gates, to see whether he’d chip in the proverbial change under his couch cushions to keep the lab open? Most of all, why the suddenness? Why not wind the lab down over a year, giving the scientists time to apply for new jobs in the academic hiring cycle? It’s not like Microsoft is in a financial crisis, lacking the cash to keep the lights on.

Yet one could also view this announcement as a lesson in why academia exists and is necessary. Yes, one should applaud those companies that choose to invest a portion of their revenue in basic research—like IBM, the old AT&T, or Microsoft itself (which continues to operate great research outfits in Redmond, Santa Barbara, both Cambridges, Beijing, Bangalore, Munich, Cairo, and Herzliya). And yes, one should acknowledge the countless times when academia falls short of its ideals, when it too places the short term above the long. All the same, it seems essential that our civilization maintain institutions for which the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge are not just accoutrements for when financial times are good and the Board of Directors is sympathetic, but are the institution’s entire reasons for being: those activities that the institution has explicitly committed to support for as long as it exists.

Batman Minus Batman

As has been discussed here and elsewhere ad nauseam, when you are dealing with certain pop-cultural icons, they belong to everyone, regardless of the opinions of their corporate attorneys. Like any other mythological figure, from Odin to Jesus to Sherlock Holmes, there is no really ‘right’ or ‘correct’ interpretation of the character of Batman; there is only the one that every individual holds to be real and true in their own personal cosmology. If the company that owns him reserves the right to change his history, his continuity, even his essential character and identity to serve their commercial needs of the moment, then it’s hard to see how they can argue that the millions of people who make up his audience don’t have the right to do the same to serve their own needs, whether they’re narrative or psychological or sociopolitical. Of course, money talks and bullshit walks in the copyright courts, but this is my space, and while I’m willing to go along with the competing visions of the Dark Knight Detective that DC presents in various media on their own merits, I’m certainly not going to resist the urge to editorialize about how those visions reinforce, or stray from, my own conception of the character that’s stuck to my psyche for over 40 rewarding and frustrating years.

The latest reframing of the Batman mythology comes to us courtesy of the FOX network and showrunner Bruno Heller, who did some solid work on HBO’s Rome and some rather more tedious work on CBS’ The Mentalist. Last night’s premiere was a decidedly mixed bag, one that I’d count overall as a substantial failure, but one with enough moments of redemption and possibility that I’ll keep tuning in for a while to see if there’s any improvement. The central conceit of Gotham is that, while taking place in a contemporary setting, it focuses not on Batman, but on the young Bruce Wayne, freshly shattered by the murder of his parents, and particularly on the young police detective Jim Gordon, who will learn about the city’s unique brand of corruption and evil as a number of future Bat-foes — including the Penguin, the Riddler, Poison Ivy, and Catwoman — develop around him. It’s an interesting idea, though my main concern is with the consistency of the execution.

First of all, though, the critique of the show-qua-show: it’s got a lot of uphill work to do. Aside from the actual killing of Thomas and Martha Wayne, a scene that likely only worked for me because it’s so reflexively iconic, the first half to three-quarters of the pilot was kind of a mess. The production design is excellent, and Gotham has an interesting, if still rather inconsistent, look to it; and British TV vet Danny Cannon does a solid job with the direction, at least from a technical standpoint. But the whole thing had a rushed, inchoate feel to it, and level of audible and visual noise left little to distinguish the episode from the truck commercials that interrupted it. Only the use of some highly distracting special effects kept a big flashy chase scene midway through from resembling similar fare from any generic police procedural, and much of the characterization felt incomplete (Oswald Cobblepot was pretty poorly drawn, a melange of conflicting motivations) or just strikingly off (Erin Richards playing Jim Gordon’s fiancee as a party girl made little sense, and the lesbian tease with Renee Montoya was the worst kind of pandering fan service). The edgy feel seemed forced, as if an attempt to conjure a mood of action when no action was taking place, and the few moments of genuine menace took place late in the pilot when they finally slowed things down and allowed the mood to build naturally after the capture of Gordon and Harvey Bullock by Fish Mooney’s gang. Perhaps most uncomfortably, the acting was generally bad at worst and forgettable at best; Ben McKenzie’s Jim Gordon lacks not just warmth but any affect whatsoever, Jada Pinkett Smith’s Fish Mooney was overdrawn and overblown, the usually excellent Donal Logue had to choke on some particularly fruity dialogue as Harv Bullock, and Erin Richards was just a write-off. Only Robin Lord Taylor as Cobblepot and the always-excellent John Doman, exuding quiet danger as gang boss Carmine Falcone, showed any real spark.

That’s not to say that the show didn’t show flashes of potential, and the pilot is rarely good in any show of quality. As noted, it’s got some great design, and if the title implies that the city itself is a character, it’s one that’s been interestingly exposed so far. Mooney’s gimp-suited butcher henchman showed real visual flare in the five seconds he was on screen before getting murdered, and Doman’s speech near the end did a lot to both show the value of slowing things down and clarify the otherwise cloudy motivations of several of the plot’s principal actors. (It’s still not clear why Renee Montoya’s outfit is called the Major Crimes unit but seems to perform the duties of an Internal Affairs section, but that may come in time.) There’s hints that Gordon’s past may make him something more than a blank-faced cypher, and you can never count out Donal Logue, no matter how much loopy dialogue you make him chew up. There were a few dramatic choices I really liked, particularly the way young Bruce Wayne snapped at Alfred and immediately seized control of the direction of a conversation; clearly, he’s already becoming Batman. (A few writers have touched on this idea, that Alfred is truly subservient, and more than a little afraid, of Batman, but it’s largely been lost in the recent tendency to butch him up and make him a substitute father figure to Bruce.) And there are a few characters yet to appear who have promise; using Carol Kane as the Penguin’s mother might turn out to be madness or genius.

Now for the big picture. The show’s central premise is an interesting one, and might just pay off while remaining true to the overall direction of the Batman mythos: what effect would it have if it were Jim Gordon, and not Batman, who was around at all these formative moments in Batman’s development? It worked well in at least one critical scene: seeking justice at the expense of sensitivity, making exactly the wrong decision for all the right reasons, a well-meaning Gordon approaches young Bruce, not yet transformed from a wounded boy to an abstracted spirit of vengeance. Instead of telling him that it’s all right to cry and feel the loss of the beloved parents who were just slaughtered in front of his eyes, Gordon cements the future implacably by urging Bruce to “be strong”. Thanks a lot, Jim! This looks like, from the previews, that it’s a thread that will continue playing out, but there are aspects of it that I like and aspects that I don’t. By having all the primary Bat-foes already in one formative stage of existence or another, it removes the onus for their existence from Batman himself and places it on Gordon — and that robs the mythology of a critically important psychological pillar, the idea that Batman, even if he doesn’t flat-out create his enemies, at least sustains them by providing endless shadowy projections of his own mentality. There’s a reason why Falcone is recently used as Batman’s earliest and easiest villain; we desperately need for it to be Batman who is responsible for the proliferation of Batman villains. He must always play an active part in their worldviews, not a passive one. Making James Gordon the catalyst for Gotham’s darkness may be an interesting approach, but where does it leave Bruce Wayne?

That leads me to my next speculation: is it possible to have Batman without Batman? I’ve thought about this a lot, and I think it’s not an impossible request and might even be a rewarding one. I certainly think it’s possible, for example, to have a Superman mythos where you almost never see Superman; he’s so powerful, so omnipresent and omnipotent, that his mere existence hangs over the world every minute of every day and inspires how people behave — or don’t behave. The mere idea of Superman can be enough. With Batman, though, this trick — while still potentially interesting — is a lot harder to pull off. Superman, to put it another way, is like the polio vaccine, protecting you even when you’re barely aware it’s there. Batman, on the other hand, is like a rogue blood cell: he sets out to aggressively combat any invasion of his territory, but he’s so dedicated and single-purposed that he can seem like a virus, or even a cancer, himself. Batman’s world without Batman is still a pretty interesting idea, but I’m not completely convinced that this is what Heller and his writers are going for; I think they’re going to just develop Batman along parallel lines as they tell the story of Gordon and the rest of the Bat-family and foes, which is going to reduce the overall impact of the villains — if all this was inevitable, what do we need Batman for? (It also creates the usual logistical problems: some future villains, like Catwoman and Poison Ivy, are young Bruce Wayne’s age or just a little older, but others — the Penguin, the Riddler, and a guy who’s presumably the Joker — have a few decades on them, meaning that it may be hard to one day develop sympathy for a Batman who’s punching the face off of an Edward Nygma or an Oswald Cobblepot who are in their fifties.)

It may very well be that I’m giving Gotham both more and less credit than it deserves; again, it’s almost impossible to get a sense of any series’ real direction or intentions from the pilot. However, while I’m not nearly the mark for comic book nonsense that I used to be — I gave Arrow half a season, and, seeing absolutely no sign of the quality some critics had promised me was just over the horizon, I dumped it without a second thought; and my interest in Flash is essentially nonexistent — I’ll give this one plenty of rope to hang itself. Batman got his hooks into me as a young boy, and I’ll never break free from my fascination with the character (or at least my conception of him), no matter how silly the results usually are. All I can do is hope against hope that the version of Gotham that plays out on screen is half as interesting as the one that’s already unspooling in my head.

Book Review: Red Plenty

I.

I decided to read Red Plenty because my biggest gripe after reading Singer’s book on Marx was that Marx refused to plan how communism would actually work, instead preferring to leave the entire matter for the World-Spirit to sort out. But almost everything that interests me about Communism falls under the category of “how communism would actually work”. Red Plenty, a semi-fictionalized account of the history of socialist economic planning, seemed like a natural follow-up.

But I’d had it on my List Of Things To Read for even longer than that, ever after stumbling across a quote from it on some blog or other:

Marx had drawn a nightmare picture of what happened to human life under capitalism, when everything was produced only in order to be exchanged; when true qualities and uses dropped away, and the human power of making and doing itself became only an object to be traded.Then the makers and the things made turned alike into commodities, and the motion of society turned into a kind of zombie dance, a grim cavorting whirl in which objects and people blurred together till the objects were half alive and the people were half dead. Stock-market prices acted back upon the world as if they were independent powers, requiring factories to be opened or closed, real human beings to work or rest, hurry or dawdle; and they, having given the transfusion that made the stock prices come alive, felt their flesh go cold and impersonal on them, mere mechanisms for chunking out the man-hours. Living money and dying humans, metal as tender as skin and skin as hard as metal, taking hands, and dancing round, and round, and round, with no way ever of stopping; the quickened and the deadened, whirling on.

And what would be the alternative? The consciously arranged alternative? A dance of another nature. A dance to the music of use, where every step fulfilled some real need, did some tangible good, and no matter how fast the dancers spun, they moved easily, because they moved to a human measure, intelligible to all, chosen by all.

Needless to say, this is Relevant To My Interests, which include among them poetic allegories for coordination problems. And I was not disappointed.

II.

The book begins:

Strange as it may seem, the gray, oppressive USSR was founded on a fairy tale. It was built on the twentieth-century magic called “the planned economy,” which was going to gush forth an abundance of good things that the lands of capitalism could never match. And just for a little while, in the heady years of the late 1950s, the magic seemed to be working. Red Plenty is about that moment in history, and how it came, and how it went away; about the brief era when, under the rash leadership of Khrushchev, the Soviet Union looked forward to a future of rich communists and envious capitalists, when Moscow would out-glitter Manhattan and every Lada would be better engineered than a Porsche. It’s about the scientists who did their genuinely brilliant best to make the dream come true, to give the tyranny its happy ending.

And this was the first interesting thing I learned.

There’s a very settled modern explanation of the conflict between capitalism and communism. Capitalism is good at growing the economy and making countries rich. Communism is good at caring for the poor and promoting equality. So your choice between capitalism and communism is a trade-off between those two things.

But for at least the first fifty years of the Cold War, the Soviets would not have come close to granting you that these are the premises on which the battle must be fought. They were officially quite certain that any day now Communism was going to prove itself better at economic growth, better at making people rich quickly, than capitalism. Even unofficially, most of their leaders and economists were pretty certain of it. And for a little while, even their capitalist enemies secretly worried they were right.

The arguments are easy to understand. Under capitalism, plutocrats use the profits of industry to buy giant yachts for themselves. Under communism, the profits can be reinvested back into the industry to build more factories or to make production more efficient, increasing growth rate.

Under capitalism, everyone is competing with each other, and much of your budget is spent on zero-sum games like advertising and marketing and sales to give you a leg up over your competition. Under communism, there is no need to play these zero-sum games and that part of the budget can be reinvested to grow the industry more quickly.

Under capitalism, everyone is working against everyone else. If Ford discovers a clever new car-manufacturing technique, their first impulse is to patent it so GM can’t use it, and GM’s first impulse is to hire thousands of lawyers to try to thwart that attempt. Under communism, everyone is working together, so if one car-manufacturing collective discovers a new technique they send their blueprints to all the other car-manufacturing collectives in order to help them out. So in capitalism, each companies will possess a few individual advances, but under communism every collective will have every advance, and so be more productive.

These arguments make a lot of sense to me, and they definitely made sense to the Communists of the first half of the 20th century. As a result, they were confident of overtaking capitalism. They realized that they’d started with a handicap – czarist Russia had been dirt poor and almost without an industrial base – and that they’d faced a further handicap in having the Nazis burn half their country during World War II – but they figured as soon as they overcame these handicaps their natural advantages would let them leap ahead of the West in only a couple of decades. The great Russian advances of the 50s – Sputnik, Gagarin, etc – were seen as evidence that this was already starting to come true in certain fields.

And then it all went wrong.

III.

Grant that communism really does have the above advantages over capitalism. What advantage does capitalism have?

The classic answer is that during communism no one wants to work hard. They do as little as they can get away with, then slack off because they don’t reap the rewards of their own labor.

Red Plenty doesn’t really have theses. In fact, it’s not really a non-fiction work at all. It’s a dramatized series of episodes in the lives of Russian workers, politicians, and academics, intended to come together to paint a picture of how the Soviet economy worked.

But if I can impose a thesis upon the text, I don’t think it agreed with this. In certain cases, Russians were very well-incentivized by things like “We will kill you unless you meet the production target”. Later, when the state became less murder-happy, the threat of death faded to threats of demotions, ruined careers, and transfer to backwater provinces. And there were equal incentives, in the form of promotion or transfer to a desirable location such as Moscow, for overperformance. There were even monetary bonuses, although money bought a lot less than it did in capitalist countries and was universally considered inferior to status in terms of purchasing power. Yes, there were Goodhart’s Law type issues going on – if you’re being judged per product, better produce ten million defective products than 9,999,999 excellent products – but that wasn’t the crux of the problem.

Red Plenty presented the problem with the Soviet economy primarily as one of allocation. You could have a perfectly good factory that could be producing lots of useful things if only you had one extra eensy-weensy part, but unless the higher-ups had allocated you that part, you were out of luck. If that part happened to break, getting a new one would depend on how much clout you (and your superiors) pulled versus how much clout other people who wanted parts (and their superiors) held.

The book illustrated this reality with a series of stories (I’m not sure how many of these were true, versus useful dramatizations). In one, a pig farmer in Siberia needed wood in order to build sties for his pigs so they wouldn’t freeze – if they froze, he would fail to meet his production target and his career would be ruined. The government, which mostly dealt with pig farming in more temperate areas, hadn’t accounted for this and so hadn’t allocated him any wood, and he didn’t have enough clout with officials to request some. A factory nearby had extra wood they weren’t using and were going to burn because it was too much trouble to figure out how to get it back to the government for re-allocation. The farmer bought the wood from the factory in an under-the-table deal. He was caught, which usually wouldn’t have been a problem because everybody did this sort of thing and it was kind of the “smoking marijuana while white” of Soviet offenses. But at that particular moment the Party higher-ups in the area wanted to make an example of someone in order to look like they were on top of their game to their higher-ups. The pig farmer was sentenced to years of hard labor.

A tire factory had been assigned a tire-making machine that could make 100,000 tires a year, but the government had gotten confused and assigned them a production quota of 150,000 tires a year. The factory leaders were stuck, because if they tried to correct the government they would look like they were challenging their superiors and get in trouble, but if they failed to meet the impossible quota, they would all get demoted and their careers would come to an end. They learned that the tire-making-machine-making company had recently invented a new model that really could make 150,000 tires a year. In the spirit of Chen Sheng, they decided that since the penalty for missing their quota was something terrible and the penalty for sabotage was also something terrible, they might as well take their chances and destroy their own machinery in the hopes the government sent them the new improved machine as a replacement. To their delight, the government believed their story about an “accident” and allotted them a new tire-making machine. However, the tire-making-machine-making company had decided to cancel production of their new model. You see, the new model, although more powerful, weighed less than the old machine, and the government was measuring their production by kilogram of machine. So it was easier for them to just continue making the old less powerful machine. The tire factory was allocated another machine that could only make 100,000 tires a year and was back in the same quandary they’d started with.

It’s easy to see how all of these problems could have been solved (or would never have come up) in a capitalist economy, with its use of prices set by supply and demand as an allocation mechanism. And it’s easy to see how thoroughly the Soviet economy was sabotaging itself by avoiding such prices.

IV.

The “hero” of Red Plenty – although most of the vignettes didn’t involve him directly – was Leonid Kantorovich, a Soviet mathematician who thought he could solve the problem. He invented the technique of linear programming, a method of solving optimization problems perfectly suited to allocating resources throughout an economy. He immediately realized its potential and wrote a nice letter to Stalin politely suggesting his current method of doing economics was wrong and he could do better – this during a time when everyone else in Russia was desperately trying to avoid having Stalin notice them because he tended to kill anyone he noticed. Luckily the letter was intercepted by a kindly mid-level official, who kept it away from Stalin and warehoused Kantorovich in a university somewhere.

During the “Khruschev thaw”, Kantorovich started getting some more politically adept followers, the higher-ups started taking note, and there was a real movement to get his ideas implemented. A few industries were run on Kantorovichian principles as a test case and seemed to do pretty well. There was an inevitable backlash. Opponents accused the linear programmers of being capitalists-in-disguise, which wasn’t helped by their use of something called “shadow prices”. But the combination of their own political adeptness and some high-level support from Khruschev – who alone of all the Soviet leaders seemed to really believe in his own cause and be a pretty okay guy – put them within arm’s reach of getting their plans implemented.

But when elements of linear programming were adopted, they were adopted piecemeal and toothless. The book places the blame on Alexei Kosygen, who implemented a bunch of economic reforms that failed, in a chapter that makes it clear exactly how constrained the Soviet leadership really was. You hear about Stalin, you imagine these guys having total power, but in reality they walked a narrow line, and all these “shadow prices” required more political capital than they were willing to mobilize, even when they thought Kantorovich might have a point.

V.

In the end, I was left with two contradictory impressions from the book.

First, amazement that the Soviet economy got as far as it did, given how incredibly screwed up it was. You hear about how many stupid things were going on at every level, and you think: This was the country that built Sputnik and Mir? This was the country that almost buried us beneath the tide of history? It is a credit to the Russian people that they were able to build so much as a screwdriver in such conditions, let alone a space station.

But second, a sense of what could have been. What if Stalin hadn’t murdered most of the competent people? What if entire fields of science hadn’t been banned for silly reasons? What if Kantorovich had been able to make the Soviet leadership base its economic planning around linear programming? How might history have turned out differently?

One of the book’s most frequently-hammered-in points was that there was was a brief moment, back during the 1950s, when everything seemed to be going right for Russia. Its year-on-year GDP growth (as estimated by impartial outside observers) was somewhere between 7 to 10%. Starvation was going down. Luxuries were going up. Kantorovich was fixing entire industries with his linear programming methods. Then Khruschev made a serious of crazy loose cannon decisions, he was ousted by Brezhnev, Kantorovich was pushed aside and ignored, the “Khruschev thaw” was reversed and tightened up again, and everything stagnated for the next twenty years.

If Khruschev had stuck around, if Kantorovich had succeeded, might the common knowledge that Communism is terrible at producing material prosperity look a little different?

The book very briefly mentioned a competing theory of resource allocation promoted by Victor Glushkov, a cyberneticist in Ukraine. He thought he could use computers – then a very new technology – to calculate optimal allocation for everyone. He failed to navigate the political seas as adroitly as Kantorovich’s faction, and the killing blow was a paper that pointed out that for him to do everything really correctly would take a hundred million years of computing time.

That was in 1960. If computing power doubles every two years, we’ve undergone about 25 doubling times since then, suggesting that we ought to be able to perform Glushkov’s calculations in three years – or three days, if we give him a lab of three hundred sixty five computers to work with. There could have been this entire field of centralized economic planning. Maybe it would have continued to underperform prices. Or maybe after decades of trial and error across the entire Soviet Union, it could have caught up. We’ll never know. Glushkov and Kantorovich were marginalized and left to play around with toy problems until their deaths in the 80s, and as far as I know their ideas were never developed further in the context of a national planned economy.

VI.

One of the ways people like insulting smart people, or rational people, or scientists, is by telling them they’re the type of people who are attracted to Communism. “Oh, you think you can control and understand everything, just like the Communists did.”

And I had always thought this was a pretty awful insult. The people I know who most identify as rationalists, or scientifically/technically minded, are also most likely to be libertarian. So there, case dismissed, everybody go home.

This book was the first time that I, as a person who considers himself rationally/technically minded, realized that I was super attracted to Communism.

Here were people who had a clear view of the problems of human civilization – all the greed, all the waste, all the zero-sum games. Who had the entire population united around a vision of a better future, whose backers could direct the entire state to better serve the goal. All they needed was to solve the engineering challenges, to solve the equations, and there they were, at the golden future. And they were smart enough to be worthy of the problem – Glushkov invented cybernetics, Kantorovich won a Nobel Prize in Economics.

And in the end, they never got the chance. There’s an interpretation of Communism as a refutation of social science, here were these people who probably knew some social science, but did it help them run a state, no it didn’t. But from the little I learned about Soviet history from this book, this seems diametrically wrong. The Soviets had practically no social science. They hated social science. You would think they would at least have some good Marxists, but apparently Stalin killed all of them just in case they might come up with versions of Marxism he didn’t like, and in terms of a vibrant scholarly field it never recovered. Economics was tainted with its association with capitalism from the very beginning, and when it happened at all it was done by non-professionals. Kantorovich was a mathematician by training; Glushkov a computer scientist.

Soviet Communism isn’t what happens when you let nerds run a country, it’s what happens when you kill all the nerds who are experts in country-running, bring in nerds from unrelated fields to replace them, then make nice noises at those nerds in principle while completely ignoring them in practice. Also, you ban all Jews from positions of importance, because fuck you.

Baggy two-piece suits are not the obvious costume for philosopher kings: but that, in theory, was what the apparatchiks who rule the Soviet Union in the 1960s were supposed to be. Lenin’s state made the same bet that Plato had twenty-five centuries earlier, when he proposed that enlightened intelligence gives absolute powers would serve the public good better than the grubby politicking of republics.On paper, the USSR was a republic, a grand multi-ethnic federation of republics indeed and its constitutions (there were several) guaranteed its citizens all manner of civil rights. But in truth the Soviet system was utterly unsympathetic to the idea of rights, if you meant by them any suggestion that the two hundred million men, women and children who inhabited the Soviet Union should be autonomously fixing on two hundred million separate directions in which to pursue happiness. This was a society with just one programme for happiness, which had been declared to be scientific and therefore was as factual as gravity.

But the Soviet experiment had run into exactly the difficulty that Plato’s admirers encountered, back in the fifth century BC, when they attempted to mould philosophical monarchies for Syracuse and Macedonia. The recipe called for rule by heavily-armed virtue—or in the Leninist case, not exactly virtue, but a sort of intentionally post-ethical counterpart to it, self-righteously brutal. Wisdom was to be set where it could be ruthless. Once such a system existed, though, the qualities required to rise in it had much more to do with ruthlessness than wisdom. Lenin’s core of Bolsheviks, and the socialists like Trotsky who joined them, were many of them highly educated people, literate in multiple European languages, learned in the scholastic traditions of Marxism; and they preserved these attributes even as they murdered and lied and tortured and terrorized. They were social scientists who thought principle required them to behave like gangsters. But their successors – the vydvizhentsy who refilled the CEntral Committee in the thirties – were not the most selfless people in Soviet society, or the most principled, or the most scrupulous. They were the most ambitious, the most domineering, the most manipulative, the most greedy, the most sycophantic: people whose adherence to Bolshevik ideas was inseparable from the power that came with them. Gradually their loyalty to the ideas became more and more instrumental, more and more a matter of what the ideas would let them grip in their two hands…

Stalin had been a gangster who really believed he was a social scientist. Khruschev was a gangster who hoped he was a social scientist. But the moment was drawing irresistibly closer when the idealism would rot away by one more degree, and the Soviet Union would be governed by gangsters who were only pretending to be social scientists.

And in the end it all failed miserably:

The Soviet economy did not move on from coal and steel and cement to plastics and microelectronics and software design, except in a very few military applications. It continued to compete with what capitalism had been doing in the 1930s, not with what it was doing now. It continued to suck resources and human labour in vast quantities into a heavy-industrial sector which had once been intended to exist as a springboard for something else, but which by now had become its own justification. Soviet industry in its last decades existed because it existed, an empire of inertia expanding ever more slowly, yet attaining the wretched distinction of absorbing more of the total effort of the economy that hosted it than heavy industry has ever done anywhere else in human history, before or since. Every year it produced goods that less and less corresponded to human needs, and whatever it once started producing, it tended to go on producing ad infinitum, since it possessed no effective stop signals except ruthless commands from above, and the people at the top no longer did ruthless, in the economic sphere. The control system for industry grew more and more erratic, the information flowing back to the planners grew more and more corrupt. And the activity of industry , all that human time and machine time it used up, added less and less value to the raw materials it sucked in. Maybe no value. Maybe less than none. One economist has argued that, by the end, it was actively destroying value; it had become a system for spoiling perfectly good materials by turning them into objects no one wanted.

I don’t know if this paragraph was intentionally written to contrast with the paragraph at the top, the one about the zombie dance of capitalism. But it is certainly instructive to make such a contrast. The Soviets had originally been inspired by this fear of economics going out of control, abandoning the human beings whose lives it was supposed to improve. In capitalist countries, people existed for the sake of the economy, but under Soviet communism, the economy was going to exist only for the sake of the people.

(accidental Russian reversal: the best kind of Russian reversal!)

And instead, they ended up taking “people existing for the sake of the economy” to entirely new and tragic extremes, people being sent to the gulags or killed because they didn’t meet the targets for some product nobody wanted that was listed on a Five-Year Plan. Spoiling good raw materials for the sake of being able to tell Party bosses and the world “Look at us! We are doing Industry!” Moloch had done some weird judo move on the Soviets’ attempt to destroy him, and he had ended up stronger than ever.

The book’s greatest flaw is that it never did get into the details of the math – or even more than a few-sentence summary of the math – and so I was left confused as to whether anything else had been possible, whether Kantorovich and Glushkov really could have saved the vision of prosperity if they’d been allowed to do so. Nevertheless, the Soviets earned my sympathy and respect in a way Marx so far has not, merely by acknowledging that the problem existed and through the existence of a few good people who tried their best to solve it.

Miliband’s speech: does he want real change, or just change that works for Labour?

During his speech yesterday, Ed Miliband made lots of references to problems with our political system.

During his speech yesterday, Ed Miliband made lots of references to problems with our political system.

she thinks politics is rubbish. And let’s not pretend we don’t hear that a lot on the doorstep…

Our politics doesn’t listen…

And to cap it all, in our politics, it’s a few who have the access while everyone else is locked out…

People think politics is more and more a game and that all we’re in it for is ourselves…

You know people think Westminster politics is out of touch, irrelevant and often disconnected from their lives…

We don’t just need to restore people’s faith in the future with this economic and social plan we need to change the way politics works in this country.

In this day and age, when people are so cynical about politics.

So, Ed thinks there are problems with our politics, that people are cynical about it and it’s all a game. So how did he choose to start his speech?

Friends, it is great to be with you in Manchester. A fantastic city. A city with a great Labour council leading the way. And a city that after this year’s local elections, is not just a Tory-free zone but a Liberal Democrat free zone as well.

He could have used that to praise some of the achievements of Manchester council, to tell us what its done for its residents. In a speech that was going to talk about reform, he could have used it as an example of what councils could achieve now, even when they’re hamstrung by the current system, and imagine what they might do if they were set free. It could have been a great way to illustrate the potential power of devolution and regionalism.

Instead, he chose to appeal to Labour tribalism and make a virtue out of the fact that Manchester is now effectively a one-party state. There are 96 members of Manchester City Council, of which 95 are Labour councillors and the other one is an ex-Labour councillor who now sits as an independent. This is all, of course, thanks to the wonders of our electoral system which means Manchester isn’t a fluke, but a regular occurence. There are councils all over England and Wales where one party has an absurd level of dominance and huge swathes of voters aren’t represented.

Is he against politics as a game, or is he fine with that game as long as Labour are winning? Is he happy for whole swathes of people to be locked out of power and not listened to? Are the Labour Party in this for proper change, or just in it for themselves? In short, does Ed Miliband really want a different kind of politics, or just a slightly tweaked version of our current kind?

Unreflective pastoralism will kill us all

The by-election in the House of Lords

Why you should vote for Merlin Charles Sainthill Hanbury-Tracy, 7th Baron Sudeley, in his own words:

Why you should vote for Hugh Francis Savile Crossley, 4th Baron Somerleyton, in his own words:

Why you should vote for John David Clotworthy Whyte-Melville Foster Skeffington, 14th Viscount Massereene and 7th Viscount Ferrard (who if elected will sit by virtue of his junior title, Baron Oriel), in his own words:

Why you should vote for Francis David Ormsby-Gore, 6th Baron Harlech, in (some of) his own words:

Why you should vote for Charles Rodney Muff, 3rd Baron Calverley, in his own words:

Why you should vote for Anthony Nicholas Colin Maitland Biddulph, 5th Baron Biddulph, in his own words:

Why you should vote for John Anthony Cadman, 3rd Baron Cadman, in his own words:

[Edited] The winner of this election, which will be decided by the votes of an unelected legislature, will join the ranks of about 90 men and two women who, by virtue of the fact that their ancestors were politicians, will sit in the parliament of an EU member state and a nuclear power for life.

Day 5004: DOCTOR WHO: Nothing at the End of the Plot

"Listen" certainly seems to have pushed the right buttons for most fans of the show, garnering near universal praise from the online communities: an acting tour de force, an intricate character study, and the rest. So I know I'm in a minority on this one.

And there must be some irony there, because "Listen" is a shaggy dog story to which the punchline is "the Emperor has no clothes".

"Why has evolution not come up with perfect hiding?" asks the man who lives in a machine that does – or at least is supposed to do – exactly that.

"Why do we talk to ourselves when we know no one is listening?" he asks when he knows his machine listens to every work he says… and broadcasts them in episodic chunks on the BBC(!)

The story opens with this typical piece of Moffat sleight-of-hand, and he proceeds to run through his usual playbook of directing you to think one thing and then pulling the rug from under you. He does it twice with the identity of the person in the spacesuit, for example.

This is the episode's biggest cheat: the "monster" on the bed. No, the cheat isn't the "did we just save him from a kid in a blanket" line, it's that Clara – who just climbed under the bed to show there was nothing there – does not just whip the sheet off whatever it is. Or at least call out the Doctor for stopping her.

And again we have non-linear intervention in childhood creating someone's future. Clara here is appalled to think that she is now responsible for Danny's past as a soldier which she clearly has trouble relating to as all the misfiring jokes attest.

It ought to be clever, this lifting the veil on how we all change each other by our interactions but rarely see the consequences separated from them as we are by time.

But this is all so familiar now, after Reinette, Amelia, Kasran Sardick, Melody/River Song, and Clara herself. So when Clara ends up doing it again to the Doctor himself, forgive me I stifled a groan.

(With all the repeats of Moffat tropes in this I was tempted to call this "Listen Again"!)

And it very much raises again the issue of consent: how can it be okay for Clara to change people's past this way, which we can explicitly link to her continuing to hug the Doctor even though he has said he doesn't like it. The message here seems to be it's okay for a girl to do that to a man because he has to change, or more bluntly grow up and stop being afraid of that thing that happens in the dark and in beds.

More interesting, potentially, is when we see it flipped when Orson hints to Clara that she is the one caught in a destiny trap now, as it's pretty obvious that if she is Orson's great-grandmother, then she and Danny have to... Does that mean Clara has no free will? Or is that her choices – getting Danny to ask her out for this drink – have set a train of events in motion. After all, if you exercise free will to jump out the window, you can't blame gravity for your lack of further choices in what inevitably follows.

In Marvel's "Days of Future Past" – comic not movie version – or rather the much longer follow up strip "Days of Future Present", knowing that their child from the future means that they have to be together actually drives a couple further part. Is Orson Pink, by telling her and potentially putting her off Danny, creating a Grandfather Paradox? Not every Grandfather Paradox has to involve killing your (great) grand-parent.

But anyway, and speaking of paradox, the answer to the mystery is that the Doctor, by investigating his childhood dream, sort of caused it himself.

All of the rational explanations could just be true. (As long as you ignore the big cheat of the possibly-child on the bed.) The Doctor wrote "listen" on his blackboard himself and forgot, as he later accuses Clara of forgetting her own childhood. When your coffee goes missing, it might just be the Doctor. The knocking sounds on the door of Orson's time capsule might just be the metal cooling and shrinking.